User login

Tender Papules on the Bilateral Dorsal Hands

The Diagnosis: Interstitial Granulomatous Dermatitis

Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis (IGD) is rare, and the exact incidence is unknown, with only a few cases reported in the literature annually.1 Although IGD may arise in both children and adults, it occurs more commonly in adults, with an age of onset of 52 to 58.5 years. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis also shows a female predominance.1

Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis may present as annular flesh-colored or erythematous to violaceous papules and plaques, or less commonly erythematous linear cordlike subcutaneous nodules (called the rope sign).1 Lesions often are asymptomatic but may be pruritic or tender. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis has been associated with autoimmune conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and primary biliary cholangitis, and rarely malignancy.2 Interstitial granulomatous drug reactions can occur months to years after initiation of therapy with offending agents, and common causes include calcium channel blockers, statins, and tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors.3

Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis and palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis (PNGD) demonstrate overlapping clinical features and are thought to be part of the same spectrum of granulomatous dermatitis.4 Both IGD and PNGD may present with symmetric flesh-colored to erythematous papules or erythematous annular or linear plaques.5 Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis and PNGD may be differentiated through histopathologic examination.

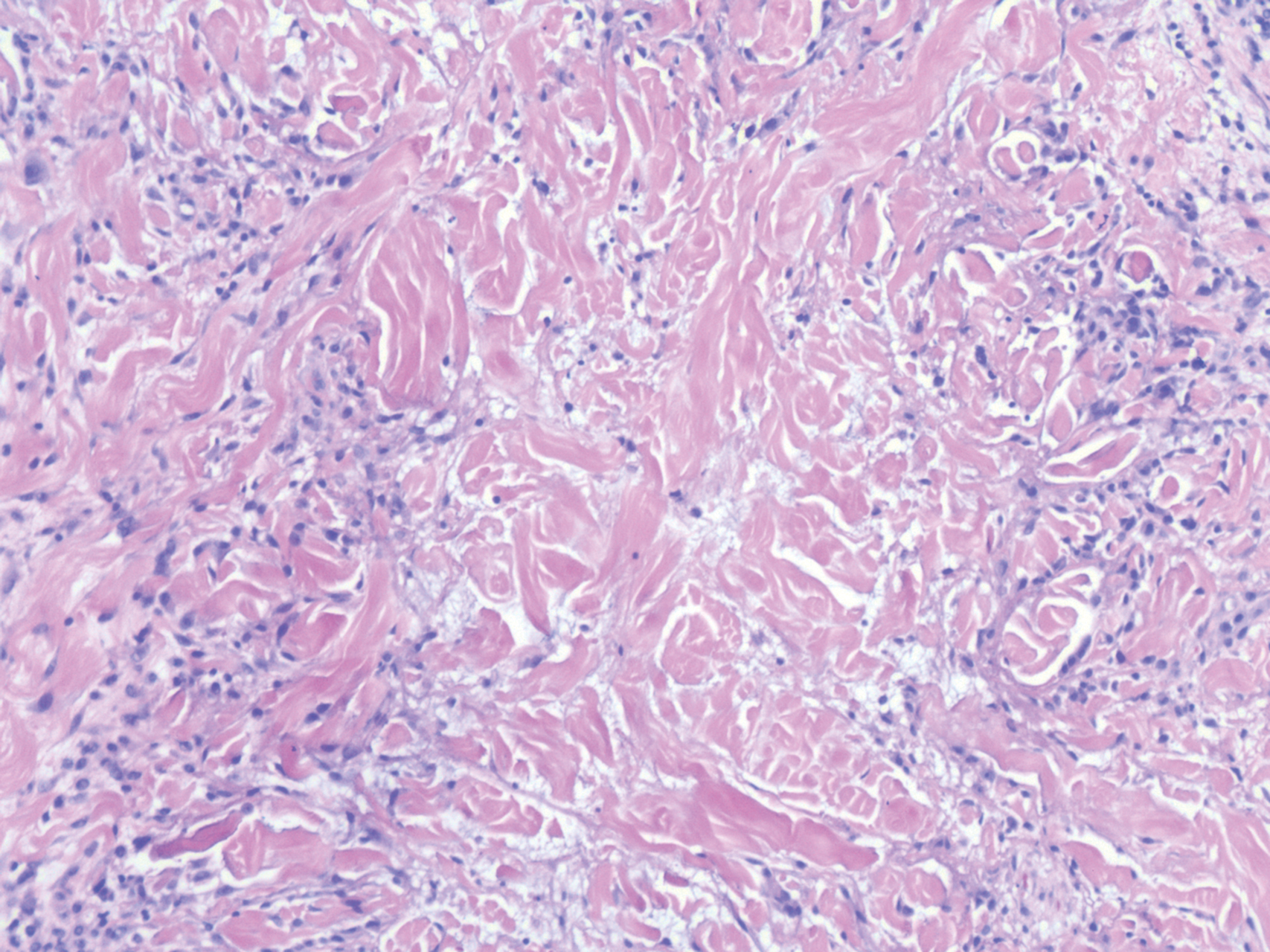

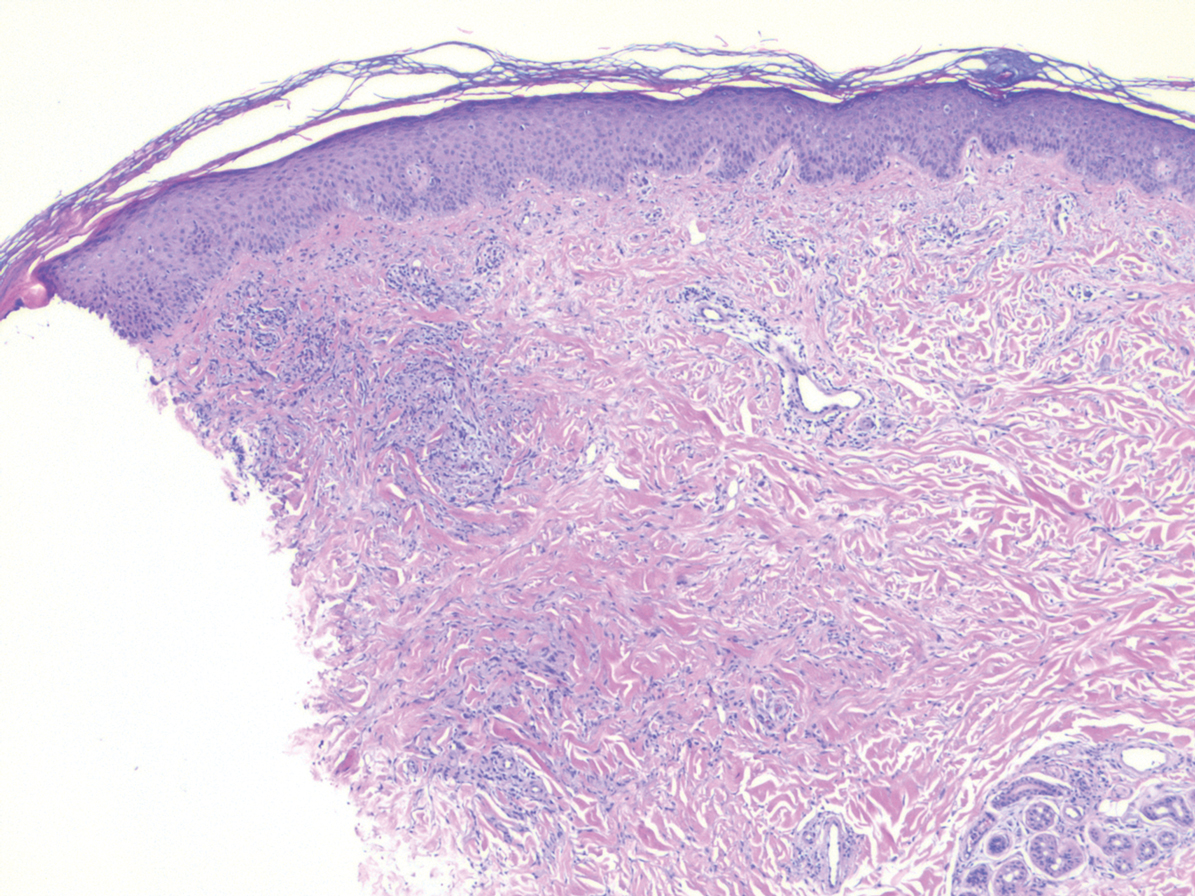

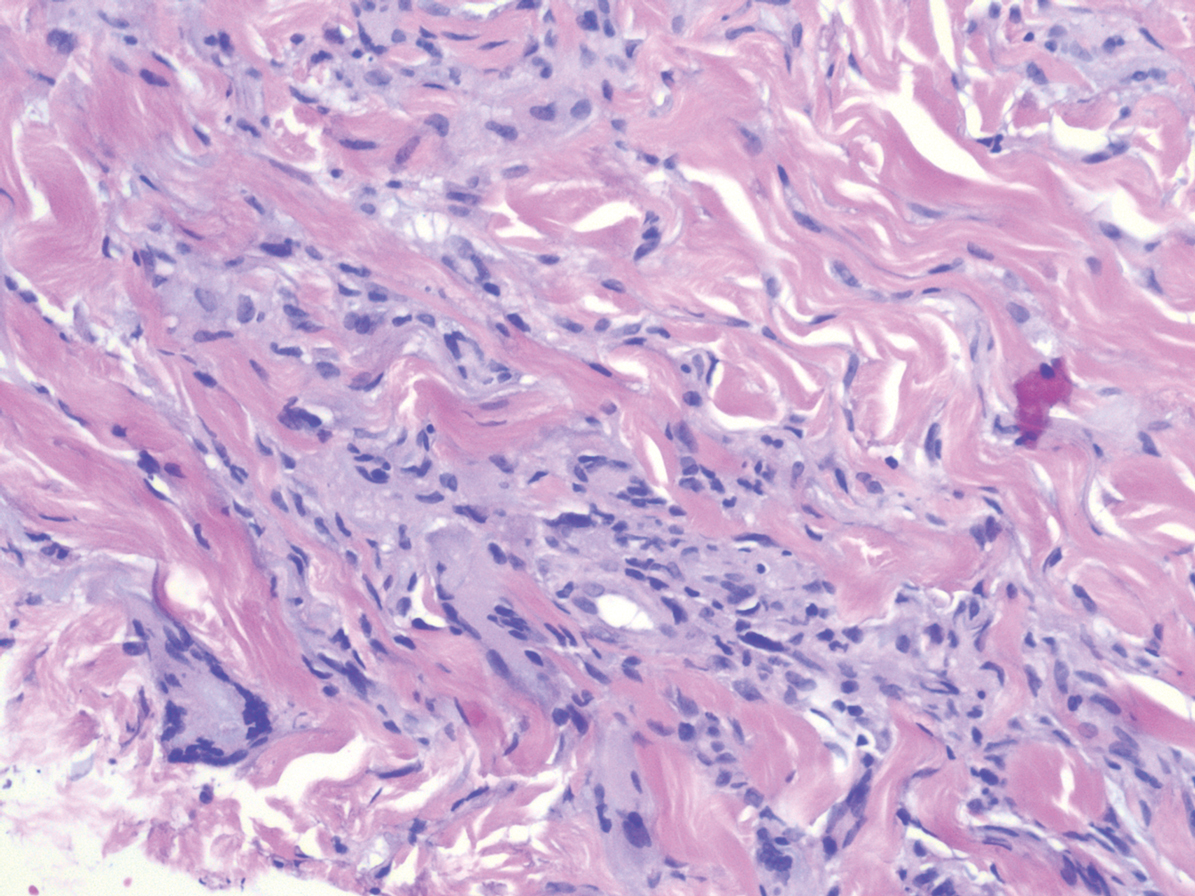

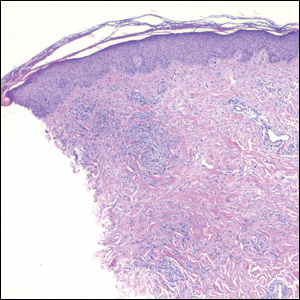

Histopathology of IGD shows an interstitial infiltrate of epithelioid histiocytes in the dermis, often surrounding foci of degenerated collagen resembling palisading granulomas (quiz images).1 Perivascular and interstitial lymphocytic infiltrates also are present in most cases. Epidermal changes are minimal in IGD but can be associated with interstitial granulomatous drug reactions.1 There usually is no vasculitis, and mucin typically is absent, unlike granuloma annulare (GA).3,6 In comparison, histopathologic examination of PNGD shows basophilic degenerated collagen surrounded by palisades of histiocytes, neutrophils, and nuclear debris with focal areas of leukocytoclastic vasculitis and rare mucin.5

No specific treatment is recommended, and lesions may resolve without any therapy. Reported treatments include topical, intralesional, or systemic steroids; nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; methotrexate; hydroxychloroquine; and cyclosporine.6 Due to the strong association with systemic diseases, it is important to evaluate patients with IGD for autoimmune diseases and conduct age-appropriate cancer screening. Furthermore, a review of medications is warranted to assess the possibility of interstitial granulomatous drug reactions.6 In our patient, rheumatologic workup and age-appropriate cancer screenings were negative, and the rash spontaneously resolved without treatment.

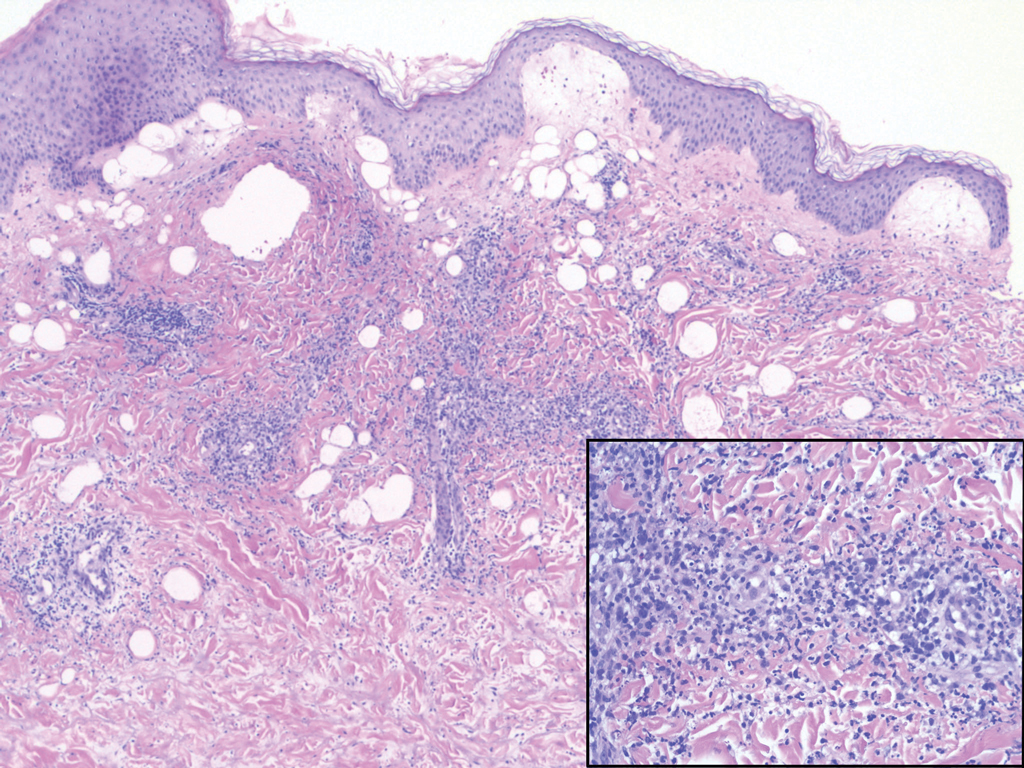

Granuloma annulare presents with asymptomatic flesh-colored to erythematous papules and plaques in an annular configuration. In the localized variant of GA, plaques frequently localize to the distal extremities, especially the dorsal hands, as in our patient. Other variants include generalized GA, subcutaneous GA, and perforating GA. Mucin and a palisading or interstitial pattern of granulomatous inflammation are key features on histopathology in all subtypes of GA (Figure 1).7 Patch GA is a rare variant that presents with asymptomatic erythematous to brown patches, is associated with interstitial-type inflammation on histopathology, and can be difficult to distinguish from IGD.8 Granuloma annulare with interstitial inflammation on histology can be differentiated from IGD by the comparative lack of mucin in IGD.7

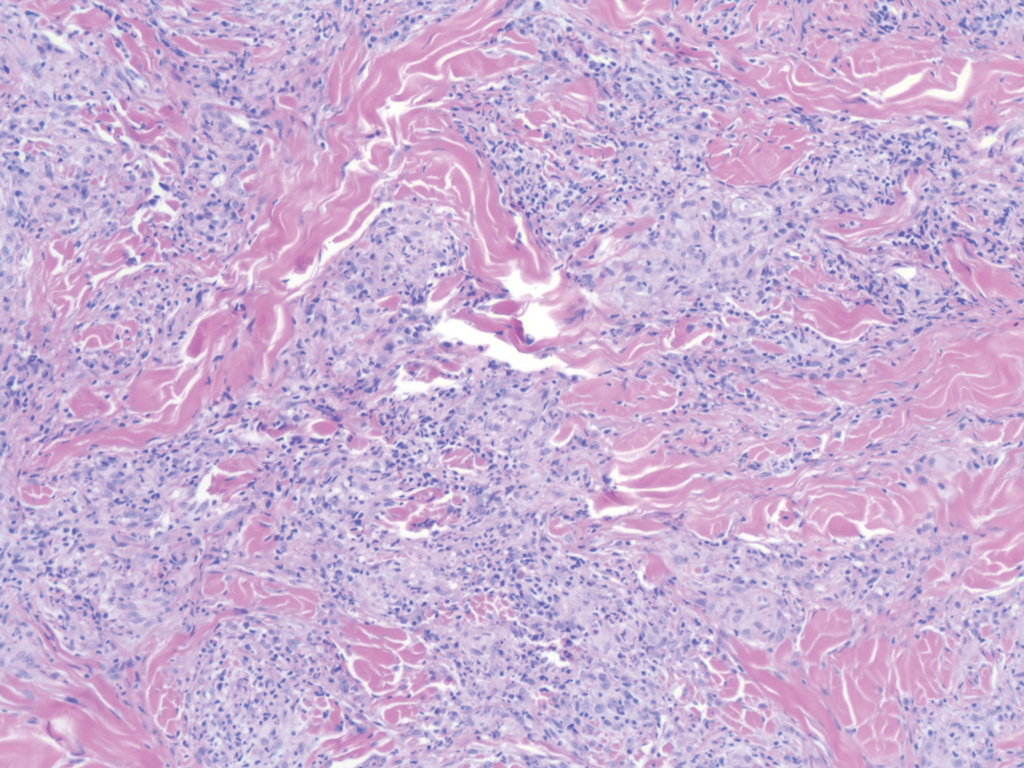

Sweet syndrome (SS) is characterized by sudden-onset, painful, erythematous plaques and/or nodules, commonly associated with fever and leukocytosis. Clinical variants of SS include pustular and bullous SS; giant cellulitis-like SS; necrotizing SS; and neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands presenting with hemorrhagic bullae, plaques, and pustules.7-9 Histopathologic examination shows dense nodular or perivascular neutrophilic infiltrate in the dermis without evidence of vasculitis (Figure 2).10 Histopathologic variants include histiocytoid, lymphocytic, subcutaneous, and cryptococcoid.9 The classic variant of SS has a bandlike, predominantly neutrophilic infiltrate with marked leukocytoclasia, which can be differentiated from the histiocytoid infiltrate of IGD.11 It has been shown that the infiltrate of the histiocytoid variant of SS is composed of myeloperoxidase-positive, immature myeloid cells rather than true histiocytes, and therefore can be differentiated from IGD.12 Lastly, all variants of SS have dermal edema, which typically is absent in IGD, and SS has no evidence of necrobiosis.

Erythema elevatum diutinum (EED) is a rare disease that presents with bilateral violaceous or erythematous to brown papules, plaques, or nodules. Lesions frequently localize to extensor surfaces, including the hands and fingers, and may be asymptomatic or associated with pruritus, burning, or tingling.13 Early EED lesions are characterized by leukocytoclastic vasculitis of the papillary and mid-dermal vessels with a perivascular neutrophilic infiltrate and perivascular fibrinoid necrosis. With older EED lesions, dermal and perivascular onion skin-like fibrosis become more prominent (Figure 3).14 The neutrophilic infiltrate, dermal fibrosis, and chronic vasculitic changes distinguish EED from IGD.

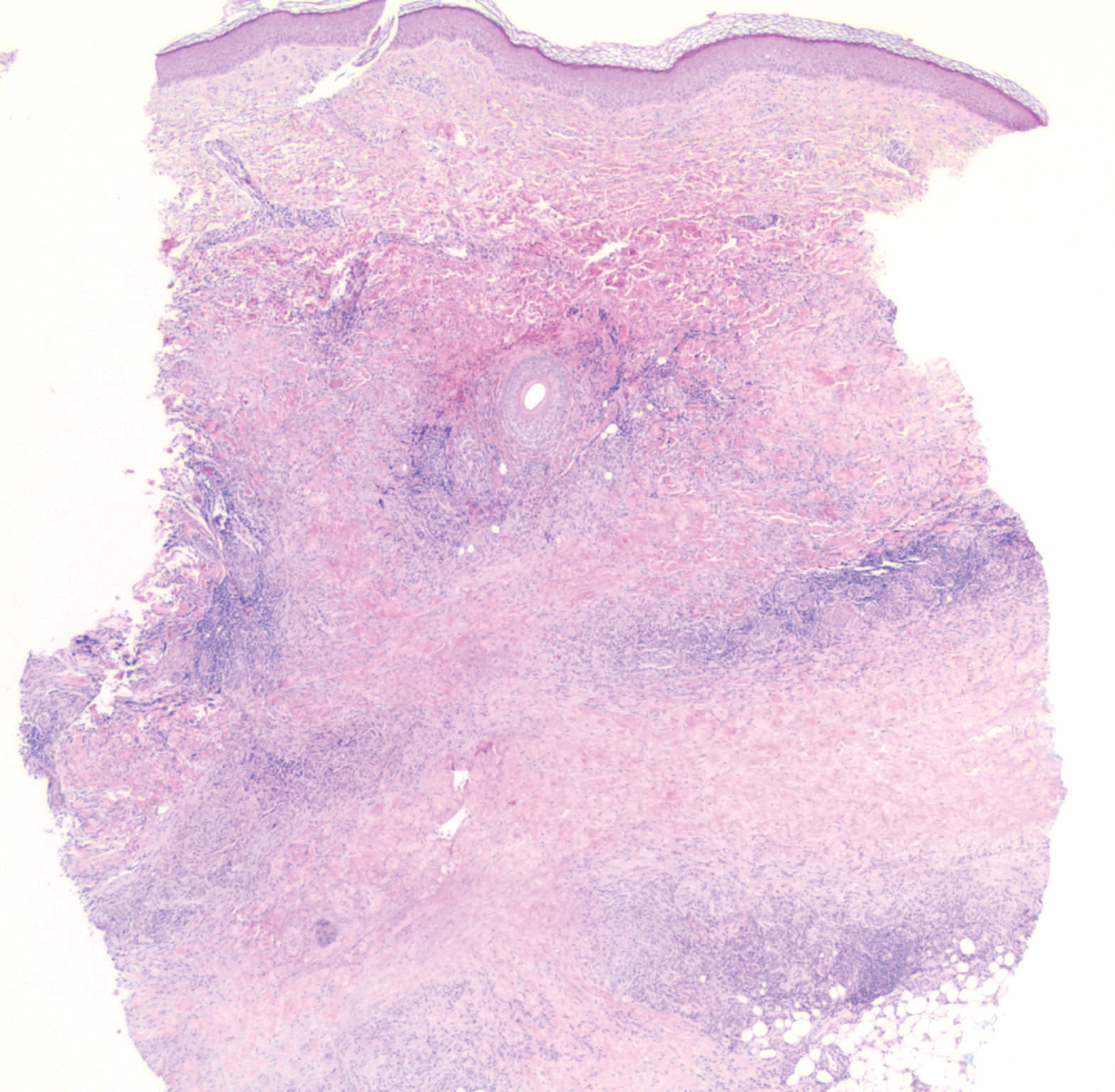

Necrobiosis lipoidica (NL) is a rare disease that presents with well-demarcated, yellow to red-brown papules and nodules most commonly localized to the bilateral lower extremities on the pretibial area. Papules and nodules evolve into plaques over time, and ulceration is common.15 On histopathology, NL primarily exhibits granulomatous inflammation with parallel palisading (Figure 4). The hallmark feature is necrobiosis--or degeneration--of collagen; the alternation of necrobiotic collagen and inflammatory infiltrate creates a layered cake-like appearance on low power.16 The clinical presentation as well as the dermal necrobiotic granuloma consisting of a large confluent area of necrobiosis centered in the superficial dermis and subcutaneous tissue of NL distinguishes it from the histiocytic infiltrate of IGD.

- Peroni A, Colato C, Schena D, et al. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis: a distinct entity with characteristic histological and clinical pattern. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166:775-783.

- Terziroli Beretta-Piccoli B, Mainetti C, Peeters MA, et al. Cutaneous granulomatosis: a comprehensive review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2018;54:131-146.

- Rosenbach MA, Wanat KA, Reisenauer A, et al. Non-infectious granulomas. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2018:1644-1663.

- Chu P, Connolly MK, LeBoit PE. The histopathologic spectrum of palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis in patients with collagen vascular disease. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:1278-1283.

- Huizenga T, Kado JA, Pellicane B, et al. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis and palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis. Cutis. 2018;101:E19-E21.

- Rosenbach M, English JC 3rd. Reactive granulomatous dermatitis: a review of palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis, interstitial granulomatous dermatitis, interstitial granulomatous drug reaction, and a proposed reclassification. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:373-387.

- Piette EW, Rosenbach M. Granuloma annulare: clinical and histologic variants, epidemiology, and genetics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:457-465.

- Mutasim DF, Bridges AG. Patch granuloma annulare: clinicopathologic study of 6 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:417-421.

- Nelson CA, Stephen S, Ashchyan HJ, et al. Neutrophilic dermatoses: pathogenesis, Sweet syndrome, neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis, and Behçet disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:987-1006.

- Dabade TS, Davis MD. Diagnosis and treatment of the neutrophilic dermatoses (pyoderma gangrenosum, Sweet's syndrome). Dermatol Ther. 2011;24:273-284.

- Davis M, Moschella L. Neutrophilic dermatoses. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2018:2102-2112.

- Requena L, Kutzner H, Palmedo G, et al. Histiocytoid Sweet syndrome: a dermal infiltration of immature neutrophilic granulocytes. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:834-842.

- Gibson LE, el-Azhary RA. Erythema elevatum diutinum. Clin Dermatol. 2000;18:295-299.

- Sardiña LA, Jour G, Piliang MP, et al. Erythema elevatum diutinum a rare and poorly understood cutaneous vasculitis: a single institution experience. J Cutan Pathol. 2019;46:97-101.

- Reid SD, Ladizinski B, Lee K, et al. Update on necrobiosis lipoidica: a review of etiology, diagnosis, and treatment options. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:783-791.

- Sibbald C, Reid S, Alavi A. Necrobiosis lipoidica. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:343-360.

The Diagnosis: Interstitial Granulomatous Dermatitis

Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis (IGD) is rare, and the exact incidence is unknown, with only a few cases reported in the literature annually.1 Although IGD may arise in both children and adults, it occurs more commonly in adults, with an age of onset of 52 to 58.5 years. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis also shows a female predominance.1

Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis may present as annular flesh-colored or erythematous to violaceous papules and plaques, or less commonly erythematous linear cordlike subcutaneous nodules (called the rope sign).1 Lesions often are asymptomatic but may be pruritic or tender. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis has been associated with autoimmune conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and primary biliary cholangitis, and rarely malignancy.2 Interstitial granulomatous drug reactions can occur months to years after initiation of therapy with offending agents, and common causes include calcium channel blockers, statins, and tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors.3

Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis and palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis (PNGD) demonstrate overlapping clinical features and are thought to be part of the same spectrum of granulomatous dermatitis.4 Both IGD and PNGD may present with symmetric flesh-colored to erythematous papules or erythematous annular or linear plaques.5 Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis and PNGD may be differentiated through histopathologic examination.

Histopathology of IGD shows an interstitial infiltrate of epithelioid histiocytes in the dermis, often surrounding foci of degenerated collagen resembling palisading granulomas (quiz images).1 Perivascular and interstitial lymphocytic infiltrates also are present in most cases. Epidermal changes are minimal in IGD but can be associated with interstitial granulomatous drug reactions.1 There usually is no vasculitis, and mucin typically is absent, unlike granuloma annulare (GA).3,6 In comparison, histopathologic examination of PNGD shows basophilic degenerated collagen surrounded by palisades of histiocytes, neutrophils, and nuclear debris with focal areas of leukocytoclastic vasculitis and rare mucin.5

No specific treatment is recommended, and lesions may resolve without any therapy. Reported treatments include topical, intralesional, or systemic steroids; nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; methotrexate; hydroxychloroquine; and cyclosporine.6 Due to the strong association with systemic diseases, it is important to evaluate patients with IGD for autoimmune diseases and conduct age-appropriate cancer screening. Furthermore, a review of medications is warranted to assess the possibility of interstitial granulomatous drug reactions.6 In our patient, rheumatologic workup and age-appropriate cancer screenings were negative, and the rash spontaneously resolved without treatment.

Granuloma annulare presents with asymptomatic flesh-colored to erythematous papules and plaques in an annular configuration. In the localized variant of GA, plaques frequently localize to the distal extremities, especially the dorsal hands, as in our patient. Other variants include generalized GA, subcutaneous GA, and perforating GA. Mucin and a palisading or interstitial pattern of granulomatous inflammation are key features on histopathology in all subtypes of GA (Figure 1).7 Patch GA is a rare variant that presents with asymptomatic erythematous to brown patches, is associated with interstitial-type inflammation on histopathology, and can be difficult to distinguish from IGD.8 Granuloma annulare with interstitial inflammation on histology can be differentiated from IGD by the comparative lack of mucin in IGD.7

Sweet syndrome (SS) is characterized by sudden-onset, painful, erythematous plaques and/or nodules, commonly associated with fever and leukocytosis. Clinical variants of SS include pustular and bullous SS; giant cellulitis-like SS; necrotizing SS; and neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands presenting with hemorrhagic bullae, plaques, and pustules.7-9 Histopathologic examination shows dense nodular or perivascular neutrophilic infiltrate in the dermis without evidence of vasculitis (Figure 2).10 Histopathologic variants include histiocytoid, lymphocytic, subcutaneous, and cryptococcoid.9 The classic variant of SS has a bandlike, predominantly neutrophilic infiltrate with marked leukocytoclasia, which can be differentiated from the histiocytoid infiltrate of IGD.11 It has been shown that the infiltrate of the histiocytoid variant of SS is composed of myeloperoxidase-positive, immature myeloid cells rather than true histiocytes, and therefore can be differentiated from IGD.12 Lastly, all variants of SS have dermal edema, which typically is absent in IGD, and SS has no evidence of necrobiosis.

Erythema elevatum diutinum (EED) is a rare disease that presents with bilateral violaceous or erythematous to brown papules, plaques, or nodules. Lesions frequently localize to extensor surfaces, including the hands and fingers, and may be asymptomatic or associated with pruritus, burning, or tingling.13 Early EED lesions are characterized by leukocytoclastic vasculitis of the papillary and mid-dermal vessels with a perivascular neutrophilic infiltrate and perivascular fibrinoid necrosis. With older EED lesions, dermal and perivascular onion skin-like fibrosis become more prominent (Figure 3).14 The neutrophilic infiltrate, dermal fibrosis, and chronic vasculitic changes distinguish EED from IGD.

Necrobiosis lipoidica (NL) is a rare disease that presents with well-demarcated, yellow to red-brown papules and nodules most commonly localized to the bilateral lower extremities on the pretibial area. Papules and nodules evolve into plaques over time, and ulceration is common.15 On histopathology, NL primarily exhibits granulomatous inflammation with parallel palisading (Figure 4). The hallmark feature is necrobiosis--or degeneration--of collagen; the alternation of necrobiotic collagen and inflammatory infiltrate creates a layered cake-like appearance on low power.16 The clinical presentation as well as the dermal necrobiotic granuloma consisting of a large confluent area of necrobiosis centered in the superficial dermis and subcutaneous tissue of NL distinguishes it from the histiocytic infiltrate of IGD.

The Diagnosis: Interstitial Granulomatous Dermatitis

Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis (IGD) is rare, and the exact incidence is unknown, with only a few cases reported in the literature annually.1 Although IGD may arise in both children and adults, it occurs more commonly in adults, with an age of onset of 52 to 58.5 years. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis also shows a female predominance.1

Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis may present as annular flesh-colored or erythematous to violaceous papules and plaques, or less commonly erythematous linear cordlike subcutaneous nodules (called the rope sign).1 Lesions often are asymptomatic but may be pruritic or tender. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis has been associated with autoimmune conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and primary biliary cholangitis, and rarely malignancy.2 Interstitial granulomatous drug reactions can occur months to years after initiation of therapy with offending agents, and common causes include calcium channel blockers, statins, and tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors.3

Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis and palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis (PNGD) demonstrate overlapping clinical features and are thought to be part of the same spectrum of granulomatous dermatitis.4 Both IGD and PNGD may present with symmetric flesh-colored to erythematous papules or erythematous annular or linear plaques.5 Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis and PNGD may be differentiated through histopathologic examination.

Histopathology of IGD shows an interstitial infiltrate of epithelioid histiocytes in the dermis, often surrounding foci of degenerated collagen resembling palisading granulomas (quiz images).1 Perivascular and interstitial lymphocytic infiltrates also are present in most cases. Epidermal changes are minimal in IGD but can be associated with interstitial granulomatous drug reactions.1 There usually is no vasculitis, and mucin typically is absent, unlike granuloma annulare (GA).3,6 In comparison, histopathologic examination of PNGD shows basophilic degenerated collagen surrounded by palisades of histiocytes, neutrophils, and nuclear debris with focal areas of leukocytoclastic vasculitis and rare mucin.5

No specific treatment is recommended, and lesions may resolve without any therapy. Reported treatments include topical, intralesional, or systemic steroids; nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; methotrexate; hydroxychloroquine; and cyclosporine.6 Due to the strong association with systemic diseases, it is important to evaluate patients with IGD for autoimmune diseases and conduct age-appropriate cancer screening. Furthermore, a review of medications is warranted to assess the possibility of interstitial granulomatous drug reactions.6 In our patient, rheumatologic workup and age-appropriate cancer screenings were negative, and the rash spontaneously resolved without treatment.

Granuloma annulare presents with asymptomatic flesh-colored to erythematous papules and plaques in an annular configuration. In the localized variant of GA, plaques frequently localize to the distal extremities, especially the dorsal hands, as in our patient. Other variants include generalized GA, subcutaneous GA, and perforating GA. Mucin and a palisading or interstitial pattern of granulomatous inflammation are key features on histopathology in all subtypes of GA (Figure 1).7 Patch GA is a rare variant that presents with asymptomatic erythematous to brown patches, is associated with interstitial-type inflammation on histopathology, and can be difficult to distinguish from IGD.8 Granuloma annulare with interstitial inflammation on histology can be differentiated from IGD by the comparative lack of mucin in IGD.7

Sweet syndrome (SS) is characterized by sudden-onset, painful, erythematous plaques and/or nodules, commonly associated with fever and leukocytosis. Clinical variants of SS include pustular and bullous SS; giant cellulitis-like SS; necrotizing SS; and neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands presenting with hemorrhagic bullae, plaques, and pustules.7-9 Histopathologic examination shows dense nodular or perivascular neutrophilic infiltrate in the dermis without evidence of vasculitis (Figure 2).10 Histopathologic variants include histiocytoid, lymphocytic, subcutaneous, and cryptococcoid.9 The classic variant of SS has a bandlike, predominantly neutrophilic infiltrate with marked leukocytoclasia, which can be differentiated from the histiocytoid infiltrate of IGD.11 It has been shown that the infiltrate of the histiocytoid variant of SS is composed of myeloperoxidase-positive, immature myeloid cells rather than true histiocytes, and therefore can be differentiated from IGD.12 Lastly, all variants of SS have dermal edema, which typically is absent in IGD, and SS has no evidence of necrobiosis.

Erythema elevatum diutinum (EED) is a rare disease that presents with bilateral violaceous or erythematous to brown papules, plaques, or nodules. Lesions frequently localize to extensor surfaces, including the hands and fingers, and may be asymptomatic or associated with pruritus, burning, or tingling.13 Early EED lesions are characterized by leukocytoclastic vasculitis of the papillary and mid-dermal vessels with a perivascular neutrophilic infiltrate and perivascular fibrinoid necrosis. With older EED lesions, dermal and perivascular onion skin-like fibrosis become more prominent (Figure 3).14 The neutrophilic infiltrate, dermal fibrosis, and chronic vasculitic changes distinguish EED from IGD.

Necrobiosis lipoidica (NL) is a rare disease that presents with well-demarcated, yellow to red-brown papules and nodules most commonly localized to the bilateral lower extremities on the pretibial area. Papules and nodules evolve into plaques over time, and ulceration is common.15 On histopathology, NL primarily exhibits granulomatous inflammation with parallel palisading (Figure 4). The hallmark feature is necrobiosis--or degeneration--of collagen; the alternation of necrobiotic collagen and inflammatory infiltrate creates a layered cake-like appearance on low power.16 The clinical presentation as well as the dermal necrobiotic granuloma consisting of a large confluent area of necrobiosis centered in the superficial dermis and subcutaneous tissue of NL distinguishes it from the histiocytic infiltrate of IGD.

- Peroni A, Colato C, Schena D, et al. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis: a distinct entity with characteristic histological and clinical pattern. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166:775-783.

- Terziroli Beretta-Piccoli B, Mainetti C, Peeters MA, et al. Cutaneous granulomatosis: a comprehensive review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2018;54:131-146.

- Rosenbach MA, Wanat KA, Reisenauer A, et al. Non-infectious granulomas. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2018:1644-1663.

- Chu P, Connolly MK, LeBoit PE. The histopathologic spectrum of palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis in patients with collagen vascular disease. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:1278-1283.

- Huizenga T, Kado JA, Pellicane B, et al. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis and palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis. Cutis. 2018;101:E19-E21.

- Rosenbach M, English JC 3rd. Reactive granulomatous dermatitis: a review of palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis, interstitial granulomatous dermatitis, interstitial granulomatous drug reaction, and a proposed reclassification. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:373-387.

- Piette EW, Rosenbach M. Granuloma annulare: clinical and histologic variants, epidemiology, and genetics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:457-465.

- Mutasim DF, Bridges AG. Patch granuloma annulare: clinicopathologic study of 6 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:417-421.

- Nelson CA, Stephen S, Ashchyan HJ, et al. Neutrophilic dermatoses: pathogenesis, Sweet syndrome, neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis, and Behçet disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:987-1006.

- Dabade TS, Davis MD. Diagnosis and treatment of the neutrophilic dermatoses (pyoderma gangrenosum, Sweet's syndrome). Dermatol Ther. 2011;24:273-284.

- Davis M, Moschella L. Neutrophilic dermatoses. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2018:2102-2112.

- Requena L, Kutzner H, Palmedo G, et al. Histiocytoid Sweet syndrome: a dermal infiltration of immature neutrophilic granulocytes. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:834-842.

- Gibson LE, el-Azhary RA. Erythema elevatum diutinum. Clin Dermatol. 2000;18:295-299.

- Sardiña LA, Jour G, Piliang MP, et al. Erythema elevatum diutinum a rare and poorly understood cutaneous vasculitis: a single institution experience. J Cutan Pathol. 2019;46:97-101.

- Reid SD, Ladizinski B, Lee K, et al. Update on necrobiosis lipoidica: a review of etiology, diagnosis, and treatment options. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:783-791.

- Sibbald C, Reid S, Alavi A. Necrobiosis lipoidica. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:343-360.

- Peroni A, Colato C, Schena D, et al. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis: a distinct entity with characteristic histological and clinical pattern. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166:775-783.

- Terziroli Beretta-Piccoli B, Mainetti C, Peeters MA, et al. Cutaneous granulomatosis: a comprehensive review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2018;54:131-146.

- Rosenbach MA, Wanat KA, Reisenauer A, et al. Non-infectious granulomas. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2018:1644-1663.

- Chu P, Connolly MK, LeBoit PE. The histopathologic spectrum of palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis in patients with collagen vascular disease. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:1278-1283.

- Huizenga T, Kado JA, Pellicane B, et al. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis and palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis. Cutis. 2018;101:E19-E21.

- Rosenbach M, English JC 3rd. Reactive granulomatous dermatitis: a review of palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis, interstitial granulomatous dermatitis, interstitial granulomatous drug reaction, and a proposed reclassification. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:373-387.

- Piette EW, Rosenbach M. Granuloma annulare: clinical and histologic variants, epidemiology, and genetics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:457-465.

- Mutasim DF, Bridges AG. Patch granuloma annulare: clinicopathologic study of 6 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:417-421.

- Nelson CA, Stephen S, Ashchyan HJ, et al. Neutrophilic dermatoses: pathogenesis, Sweet syndrome, neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis, and Behçet disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:987-1006.

- Dabade TS, Davis MD. Diagnosis and treatment of the neutrophilic dermatoses (pyoderma gangrenosum, Sweet's syndrome). Dermatol Ther. 2011;24:273-284.

- Davis M, Moschella L. Neutrophilic dermatoses. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2018:2102-2112.

- Requena L, Kutzner H, Palmedo G, et al. Histiocytoid Sweet syndrome: a dermal infiltration of immature neutrophilic granulocytes. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:834-842.

- Gibson LE, el-Azhary RA. Erythema elevatum diutinum. Clin Dermatol. 2000;18:295-299.

- Sardiña LA, Jour G, Piliang MP, et al. Erythema elevatum diutinum a rare and poorly understood cutaneous vasculitis: a single institution experience. J Cutan Pathol. 2019;46:97-101.

- Reid SD, Ladizinski B, Lee K, et al. Update on necrobiosis lipoidica: a review of etiology, diagnosis, and treatment options. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:783-791.

- Sibbald C, Reid S, Alavi A. Necrobiosis lipoidica. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:343-360.

A 58-year-old woman with a medical history of asthma, hypertension, hypothyroidism, and hyperlipidemia presented with a painful rash of 10 days' duration. The rash was associated with fever at home (temperature, 38.5.2 °C), and a review of systems was positive for joint pain. Physical examination revealed numerous 8- to 10-mm, erythematous, discus-shaped papules on the bilateral dorsal hands, bilateral palms, right knee, and right dorsal foot with slight tenderness to palpation. A papule on the right dorsal hand was biopsied.

Sniffing Out Malignant Melanoma: A Case of Canine Olfactory Detection

To the Editor:

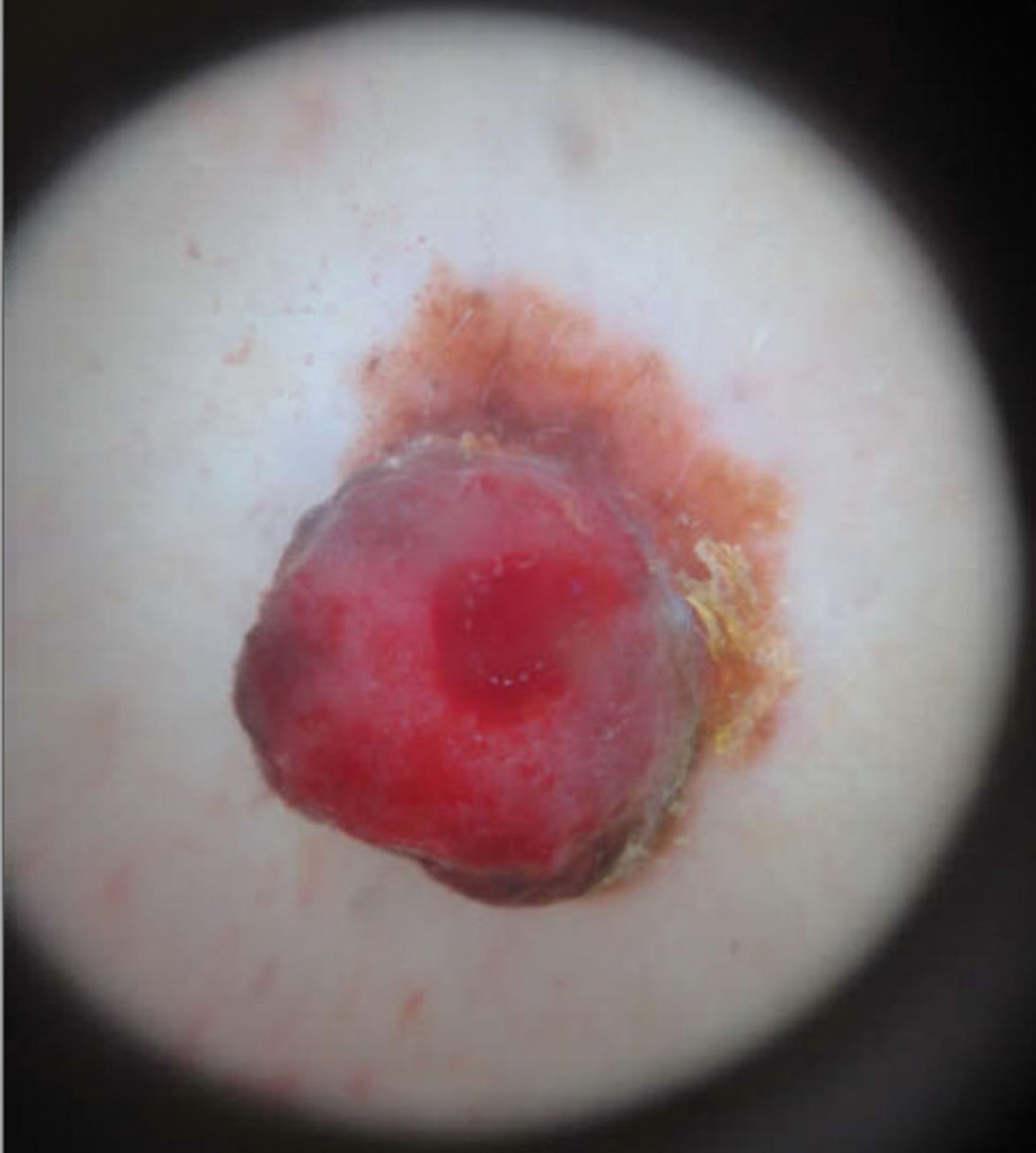

A 43-year-old woman presented with a mole on the central back that had been present since childhood and had changed and grown over the last few years. The patient reported that her 2-year-old rescue dog frequently sniffed the mole and would subsequently get agitated and try to scratch and bite the lesion. This behavior prompted the patient to visit a dermatologist.

She reported no personal history of melanoma or nonmelanoma skin cancer, tanning booth exposure, blistering sunburns, or use of immunosuppressant medications. Her family history was remarkable for basal cell carcinoma in her father but no family history of melanoma. Physical examination revealed a 1.2×1.5-cm brown patch along with a 1×1-cm ulcerated nodule on the lower aspect of the lesion (Figure 1). Dermoscopy showed a blue-white veil and an irregular vascular pattern (Figure 2). No cervical, axillary, or inguinal lymphadenopathy was appreciated on physical examination. Reflectance confocal microscopy showed pagetoid spread of atypical round melanocytes as well as melanocytes in the stratum corneum (Figure 3).

The patient was referred to a surgical oncologist for wide local excision and sentinel lymph node biopsy. Pathology showed a 4-mm-thick melanoma with numerous positive lymph nodes (Figure 4). The patient subsequently underwent a right axillary lymphadenectomy and was diagnosed with stage IIIB malignant melanoma. After surgery, the patient reported that her dog would now sniff her back and calmly rest his head in her lap.

She was treated with ipilimumab but subsequently developed panhypopituitarism, so she was taken off the ipilimumab. Currently, the patient is doing well. She follows up annually for full-body skin examinations and has not had any recurrence in the last 7 years. The patient credits her dog for prompting her to see a dermatologist and saving her life.

Both anecdotal and systematic evidence have emerged on the role of canine olfaction in the detection of lung, breast, colorectal, ovarian, prostate, and skin cancers, including malignant melanoma.1-6 A 1989 case report described a woman who was prompted to seek dermatologic evaluation of a pigmented lesion because her dog consistently targeted the lesion. Excision and subsequent histopathologic examination of the lesion revealed that it was malignant melanoma.5 Another case report described a patient whose dog, which was not trained to detect cancers in humans, persistently licked a lesion behind the patient’s ear that eventually was found to be malignant melanoma.6 These reports have inspired considerable research interest regarding canine olfaction as a potential method to noninvasively screen for and even diagnose malignant melanomas in humans.

Both physiologic and pathologic metabolic processes result in the production of volatile organic compounds (VOCs), or small odorant molecules that evaporate at normal temperatures and pressures.1 Individual cells release VOCs in extremely low concentrations into the blood, urine, feces, and breath, as well as onto the skin’s surface, but there are methods for detecting these VOCs, including gas chromatography–mass spectrometry and canine olfaction.7,8 Pathologic processes, such as infection and malignancy, result in irregular protein synthesis and metabolism, producing new VOCs or differing concentrations of VOCs as compared to normal processes.1

Dimethyl disulfide and dimethyl trisulfide compounds have been identified in malignant melanoma, and these compounds are not produced by normal melanocytes.7 Furthermore, malignant melanoma produces differing quantities of these compounds as compared to normal melanocytes, including isovaleric acid, 2-methylbutyric acid, isoamyl alcohol (3-methyl-1-butanol), and 2-methyl-1-butanol, resulting in a distinct odorant profile that previously has been detected via canine olfaction.7 Canine olfaction can identify odorant molecules at up to 1 part per trillion (a magnitude more sensitive than the currently available gas chromatography–mass spectrometry technologies) and can detect the production of new VOCs or altered VOC ratios due to pathologic processes.1 Systematic studies with dogs that are trained to detect cancers in humans have shown that canine olfaction correctly identified malignant melanomas against healthy skin, benign nevi, and even basal cell carcinomas at higher rates than what would have been expected by chance alone.2,3

Canine olfaction can identify new or altered ratios of odorant VOCs associated with pathologic metabolic processes, and canines can be trained to target odor profiles associated with specific diseases.1 Canine olfaction for melanoma screening and diagnosis may seem appealing, as it provides an easily transportable, real-time, low-cost method compared to other techniques such as gas chromatography–mass spectrometry.1 Although preliminary results have shown that canine olfaction detects melanoma at higher rates than would be expected by chance alone, these findings have not approached clinical utility for the widespread use of canine olfaction as a screening method for melanoma.2,3,9 Further studies are needed to understand the role of canine olfaction in melanoma screening and diagnosis as well as to explore methods to optimize sensitivity and specificity. Until then, patients and dermatologists should not ignore the behavior of dogs toward skin lesions. Dogs may be beneficial in the detection of melanoma and help save lives, as was seen in our case.

- Angle C, Waggoner LP, Ferrando A, et al. Canine detection of the volatilome: a review of implications for pathogen and disease detection. Front Vet Sci. 2016;3:47.

- Pickel D, Mauncy GP, Walker DB, et al. Evidence for canine olfactory detection of melanoma. Applied Animal Behaviour Science. 2004;89:107-116.

- Willis CM, Britton LE, Swindells MA, et al. Invasive melanoma in vivo can be distinguished from basal cell carcinoma, benign naevi and healthy skin by canine olfaction: a proof‐of‐principle study of differential volatile organic compound emission. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175:1020-1029.

- Jezierski T, Walczak M, Ligor T, et al. Study of the art: canine olfaction used for cancer detection on the basis of breath odour. perspectives and limitations. J Breath Res. 2015;9:027001.

- Williams H, Pembroke A. Sniffer dogs in the melanoma clinic? Lancet. 1989;1:734.

- Campbell LF, Farmery L, George SM, et al. Canine olfactory detection of malignant melanoma. BMJ Case Rep. 2013. doi:10.1136/bcr-2013-008566.

- Kwak J, Gallagher M, Ozdener MH, et al. Volatile biomarkers from human melanoma cells. J Chromotogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2013;931:90-96.

- D’Amico A, Bono R, Pennazza G, et al. Identification of melanoma with a gas sensor array. Skin Res Technol. 2008;14:226-236.

- Elliker KR, Williams HC. Detection of skin cancer odours using dogs: a step forward in melanoma detection training and research methodologies. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175:851-852.

To the Editor:

A 43-year-old woman presented with a mole on the central back that had been present since childhood and had changed and grown over the last few years. The patient reported that her 2-year-old rescue dog frequently sniffed the mole and would subsequently get agitated and try to scratch and bite the lesion. This behavior prompted the patient to visit a dermatologist.

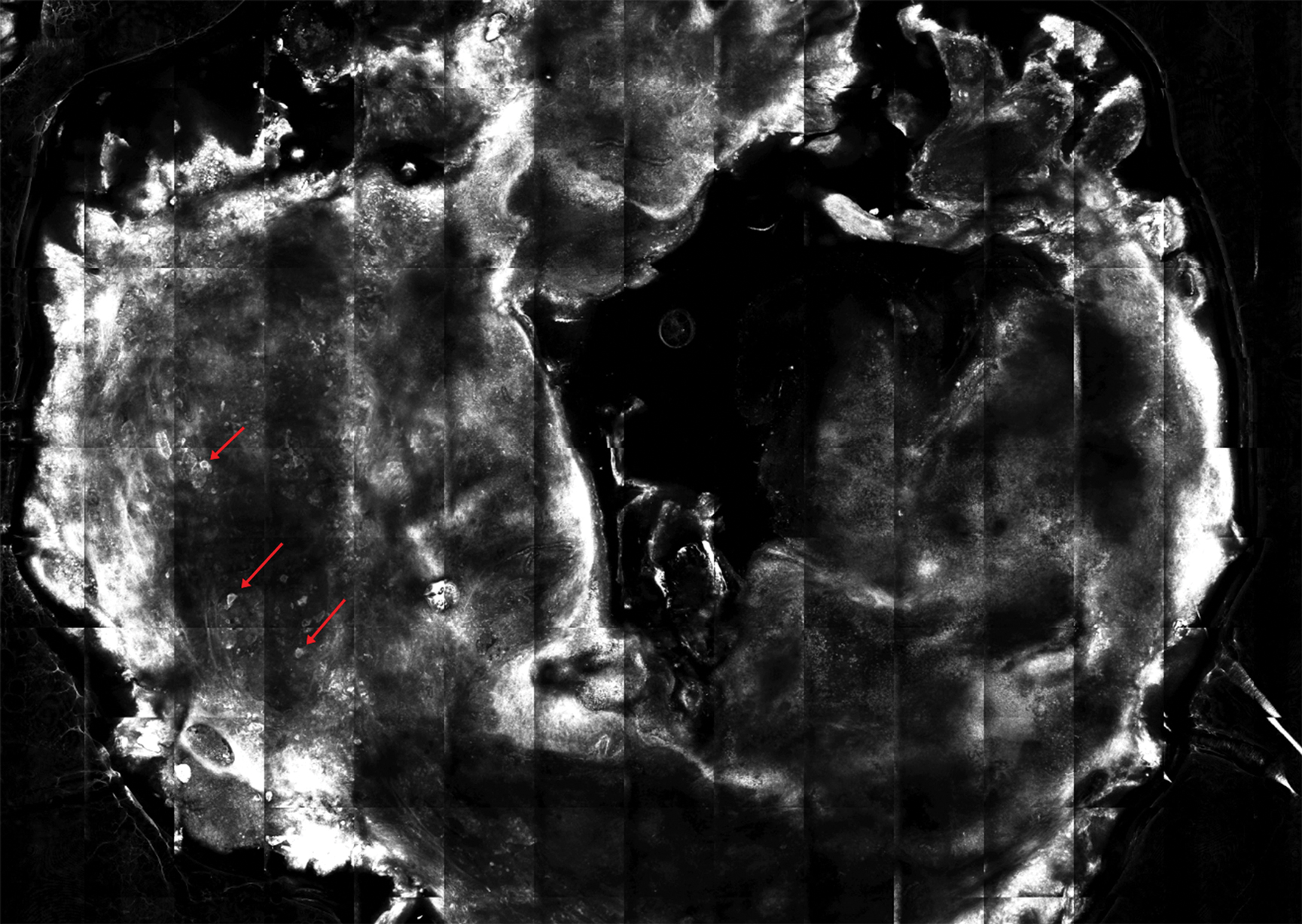

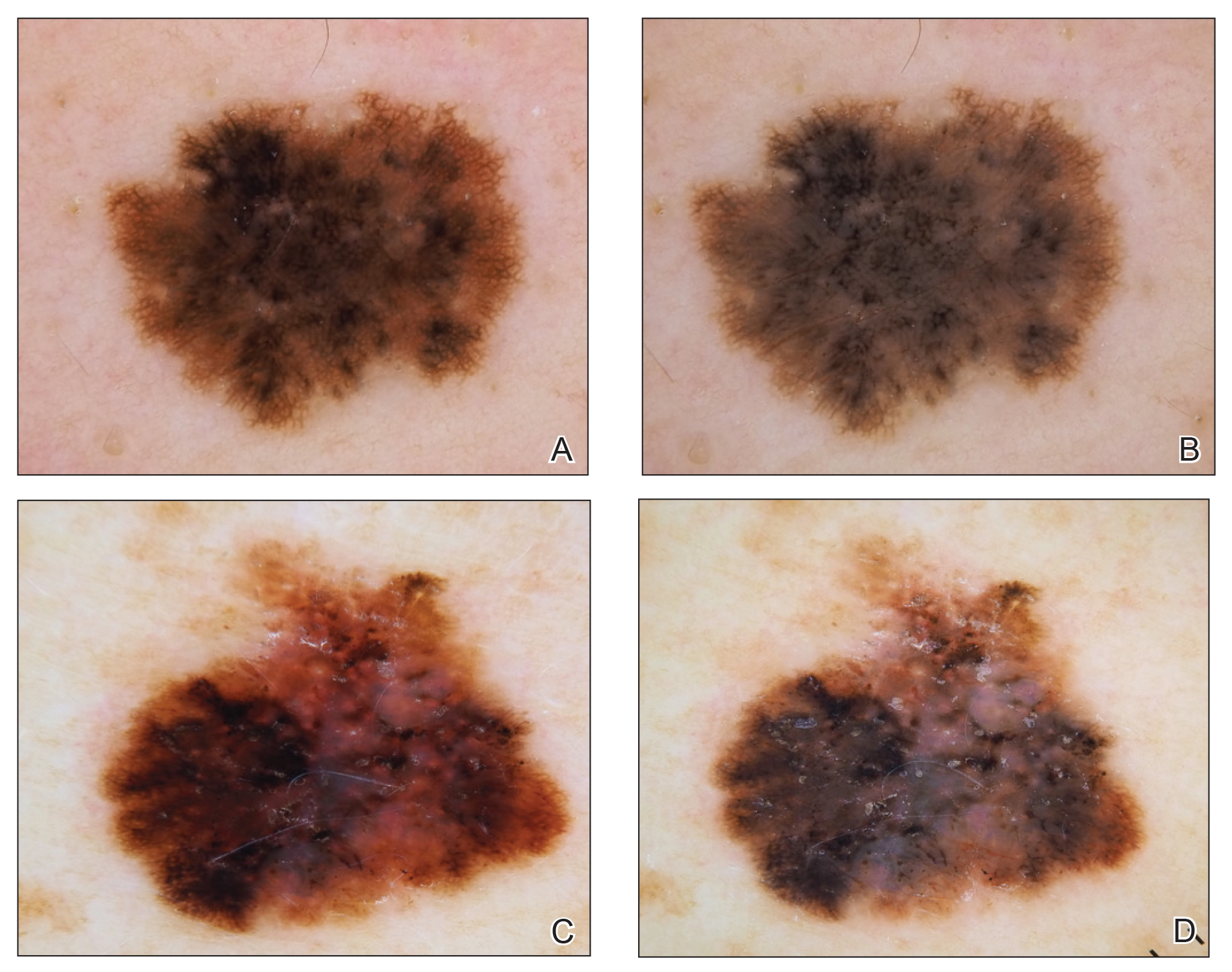

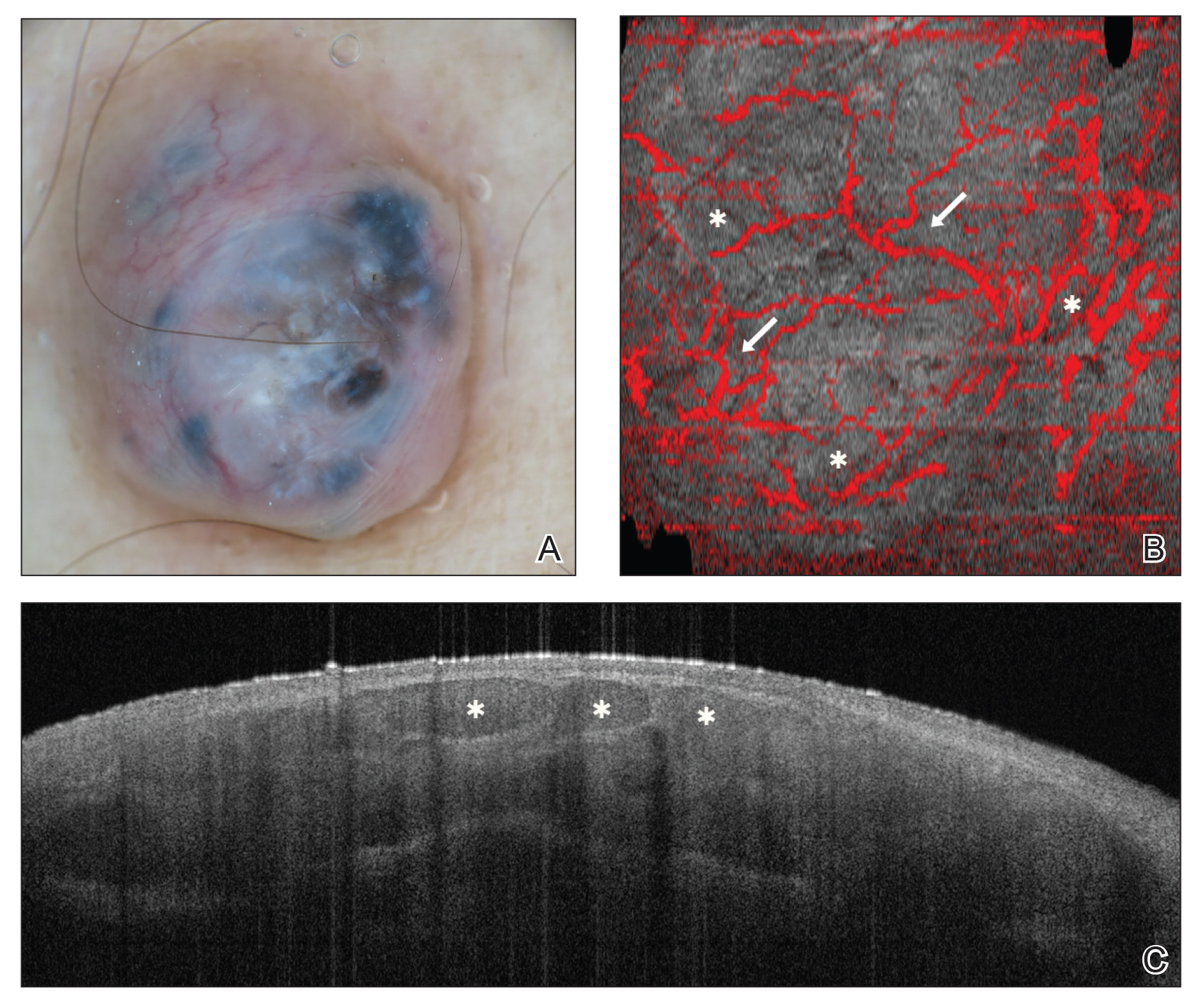

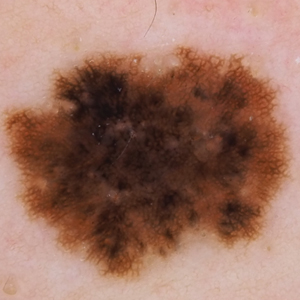

She reported no personal history of melanoma or nonmelanoma skin cancer, tanning booth exposure, blistering sunburns, or use of immunosuppressant medications. Her family history was remarkable for basal cell carcinoma in her father but no family history of melanoma. Physical examination revealed a 1.2×1.5-cm brown patch along with a 1×1-cm ulcerated nodule on the lower aspect of the lesion (Figure 1). Dermoscopy showed a blue-white veil and an irregular vascular pattern (Figure 2). No cervical, axillary, or inguinal lymphadenopathy was appreciated on physical examination. Reflectance confocal microscopy showed pagetoid spread of atypical round melanocytes as well as melanocytes in the stratum corneum (Figure 3).

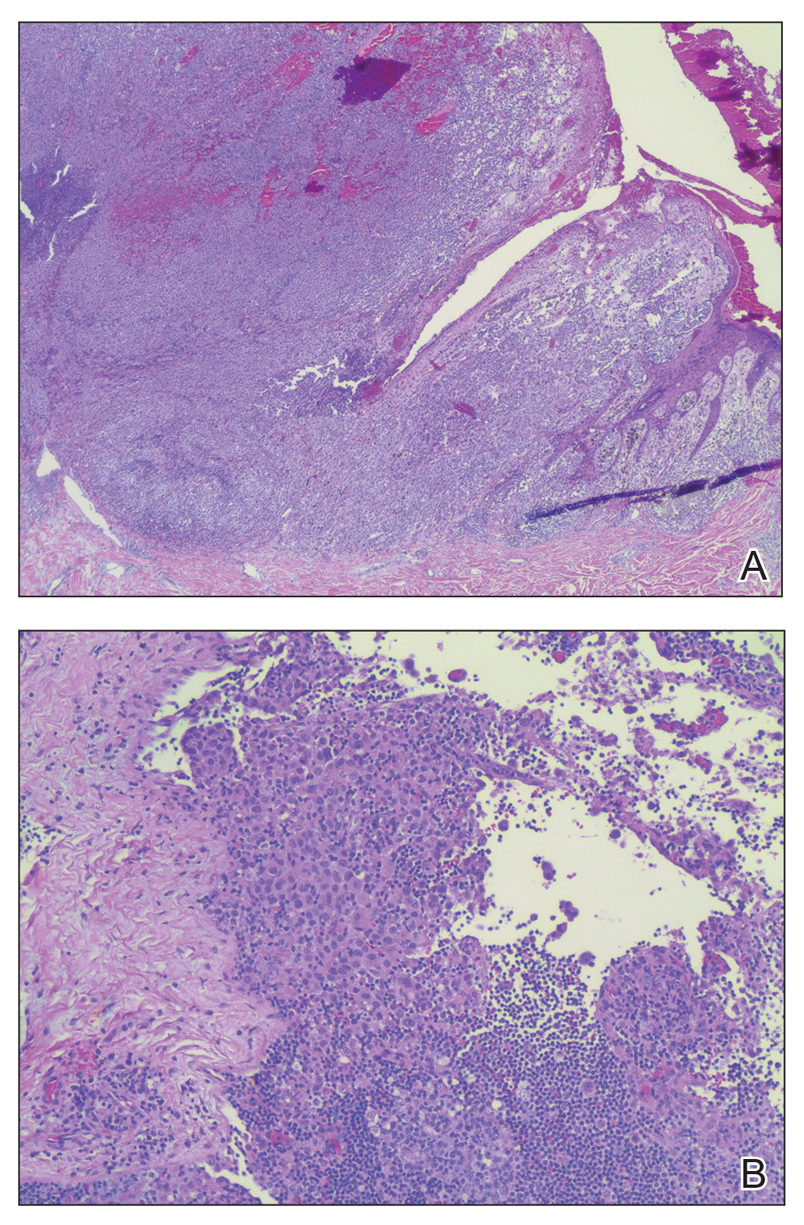

The patient was referred to a surgical oncologist for wide local excision and sentinel lymph node biopsy. Pathology showed a 4-mm-thick melanoma with numerous positive lymph nodes (Figure 4). The patient subsequently underwent a right axillary lymphadenectomy and was diagnosed with stage IIIB malignant melanoma. After surgery, the patient reported that her dog would now sniff her back and calmly rest his head in her lap.

She was treated with ipilimumab but subsequently developed panhypopituitarism, so she was taken off the ipilimumab. Currently, the patient is doing well. She follows up annually for full-body skin examinations and has not had any recurrence in the last 7 years. The patient credits her dog for prompting her to see a dermatologist and saving her life.

Both anecdotal and systematic evidence have emerged on the role of canine olfaction in the detection of lung, breast, colorectal, ovarian, prostate, and skin cancers, including malignant melanoma.1-6 A 1989 case report described a woman who was prompted to seek dermatologic evaluation of a pigmented lesion because her dog consistently targeted the lesion. Excision and subsequent histopathologic examination of the lesion revealed that it was malignant melanoma.5 Another case report described a patient whose dog, which was not trained to detect cancers in humans, persistently licked a lesion behind the patient’s ear that eventually was found to be malignant melanoma.6 These reports have inspired considerable research interest regarding canine olfaction as a potential method to noninvasively screen for and even diagnose malignant melanomas in humans.

Both physiologic and pathologic metabolic processes result in the production of volatile organic compounds (VOCs), or small odorant molecules that evaporate at normal temperatures and pressures.1 Individual cells release VOCs in extremely low concentrations into the blood, urine, feces, and breath, as well as onto the skin’s surface, but there are methods for detecting these VOCs, including gas chromatography–mass spectrometry and canine olfaction.7,8 Pathologic processes, such as infection and malignancy, result in irregular protein synthesis and metabolism, producing new VOCs or differing concentrations of VOCs as compared to normal processes.1

Dimethyl disulfide and dimethyl trisulfide compounds have been identified in malignant melanoma, and these compounds are not produced by normal melanocytes.7 Furthermore, malignant melanoma produces differing quantities of these compounds as compared to normal melanocytes, including isovaleric acid, 2-methylbutyric acid, isoamyl alcohol (3-methyl-1-butanol), and 2-methyl-1-butanol, resulting in a distinct odorant profile that previously has been detected via canine olfaction.7 Canine olfaction can identify odorant molecules at up to 1 part per trillion (a magnitude more sensitive than the currently available gas chromatography–mass spectrometry technologies) and can detect the production of new VOCs or altered VOC ratios due to pathologic processes.1 Systematic studies with dogs that are trained to detect cancers in humans have shown that canine olfaction correctly identified malignant melanomas against healthy skin, benign nevi, and even basal cell carcinomas at higher rates than what would have been expected by chance alone.2,3

Canine olfaction can identify new or altered ratios of odorant VOCs associated with pathologic metabolic processes, and canines can be trained to target odor profiles associated with specific diseases.1 Canine olfaction for melanoma screening and diagnosis may seem appealing, as it provides an easily transportable, real-time, low-cost method compared to other techniques such as gas chromatography–mass spectrometry.1 Although preliminary results have shown that canine olfaction detects melanoma at higher rates than would be expected by chance alone, these findings have not approached clinical utility for the widespread use of canine olfaction as a screening method for melanoma.2,3,9 Further studies are needed to understand the role of canine olfaction in melanoma screening and diagnosis as well as to explore methods to optimize sensitivity and specificity. Until then, patients and dermatologists should not ignore the behavior of dogs toward skin lesions. Dogs may be beneficial in the detection of melanoma and help save lives, as was seen in our case.

To the Editor:

A 43-year-old woman presented with a mole on the central back that had been present since childhood and had changed and grown over the last few years. The patient reported that her 2-year-old rescue dog frequently sniffed the mole and would subsequently get agitated and try to scratch and bite the lesion. This behavior prompted the patient to visit a dermatologist.

She reported no personal history of melanoma or nonmelanoma skin cancer, tanning booth exposure, blistering sunburns, or use of immunosuppressant medications. Her family history was remarkable for basal cell carcinoma in her father but no family history of melanoma. Physical examination revealed a 1.2×1.5-cm brown patch along with a 1×1-cm ulcerated nodule on the lower aspect of the lesion (Figure 1). Dermoscopy showed a blue-white veil and an irregular vascular pattern (Figure 2). No cervical, axillary, or inguinal lymphadenopathy was appreciated on physical examination. Reflectance confocal microscopy showed pagetoid spread of atypical round melanocytes as well as melanocytes in the stratum corneum (Figure 3).

The patient was referred to a surgical oncologist for wide local excision and sentinel lymph node biopsy. Pathology showed a 4-mm-thick melanoma with numerous positive lymph nodes (Figure 4). The patient subsequently underwent a right axillary lymphadenectomy and was diagnosed with stage IIIB malignant melanoma. After surgery, the patient reported that her dog would now sniff her back and calmly rest his head in her lap.

She was treated with ipilimumab but subsequently developed panhypopituitarism, so she was taken off the ipilimumab. Currently, the patient is doing well. She follows up annually for full-body skin examinations and has not had any recurrence in the last 7 years. The patient credits her dog for prompting her to see a dermatologist and saving her life.

Both anecdotal and systematic evidence have emerged on the role of canine olfaction in the detection of lung, breast, colorectal, ovarian, prostate, and skin cancers, including malignant melanoma.1-6 A 1989 case report described a woman who was prompted to seek dermatologic evaluation of a pigmented lesion because her dog consistently targeted the lesion. Excision and subsequent histopathologic examination of the lesion revealed that it was malignant melanoma.5 Another case report described a patient whose dog, which was not trained to detect cancers in humans, persistently licked a lesion behind the patient’s ear that eventually was found to be malignant melanoma.6 These reports have inspired considerable research interest regarding canine olfaction as a potential method to noninvasively screen for and even diagnose malignant melanomas in humans.

Both physiologic and pathologic metabolic processes result in the production of volatile organic compounds (VOCs), or small odorant molecules that evaporate at normal temperatures and pressures.1 Individual cells release VOCs in extremely low concentrations into the blood, urine, feces, and breath, as well as onto the skin’s surface, but there are methods for detecting these VOCs, including gas chromatography–mass spectrometry and canine olfaction.7,8 Pathologic processes, such as infection and malignancy, result in irregular protein synthesis and metabolism, producing new VOCs or differing concentrations of VOCs as compared to normal processes.1

Dimethyl disulfide and dimethyl trisulfide compounds have been identified in malignant melanoma, and these compounds are not produced by normal melanocytes.7 Furthermore, malignant melanoma produces differing quantities of these compounds as compared to normal melanocytes, including isovaleric acid, 2-methylbutyric acid, isoamyl alcohol (3-methyl-1-butanol), and 2-methyl-1-butanol, resulting in a distinct odorant profile that previously has been detected via canine olfaction.7 Canine olfaction can identify odorant molecules at up to 1 part per trillion (a magnitude more sensitive than the currently available gas chromatography–mass spectrometry technologies) and can detect the production of new VOCs or altered VOC ratios due to pathologic processes.1 Systematic studies with dogs that are trained to detect cancers in humans have shown that canine olfaction correctly identified malignant melanomas against healthy skin, benign nevi, and even basal cell carcinomas at higher rates than what would have been expected by chance alone.2,3

Canine olfaction can identify new or altered ratios of odorant VOCs associated with pathologic metabolic processes, and canines can be trained to target odor profiles associated with specific diseases.1 Canine olfaction for melanoma screening and diagnosis may seem appealing, as it provides an easily transportable, real-time, low-cost method compared to other techniques such as gas chromatography–mass spectrometry.1 Although preliminary results have shown that canine olfaction detects melanoma at higher rates than would be expected by chance alone, these findings have not approached clinical utility for the widespread use of canine olfaction as a screening method for melanoma.2,3,9 Further studies are needed to understand the role of canine olfaction in melanoma screening and diagnosis as well as to explore methods to optimize sensitivity and specificity. Until then, patients and dermatologists should not ignore the behavior of dogs toward skin lesions. Dogs may be beneficial in the detection of melanoma and help save lives, as was seen in our case.

- Angle C, Waggoner LP, Ferrando A, et al. Canine detection of the volatilome: a review of implications for pathogen and disease detection. Front Vet Sci. 2016;3:47.

- Pickel D, Mauncy GP, Walker DB, et al. Evidence for canine olfactory detection of melanoma. Applied Animal Behaviour Science. 2004;89:107-116.

- Willis CM, Britton LE, Swindells MA, et al. Invasive melanoma in vivo can be distinguished from basal cell carcinoma, benign naevi and healthy skin by canine olfaction: a proof‐of‐principle study of differential volatile organic compound emission. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175:1020-1029.

- Jezierski T, Walczak M, Ligor T, et al. Study of the art: canine olfaction used for cancer detection on the basis of breath odour. perspectives and limitations. J Breath Res. 2015;9:027001.

- Williams H, Pembroke A. Sniffer dogs in the melanoma clinic? Lancet. 1989;1:734.

- Campbell LF, Farmery L, George SM, et al. Canine olfactory detection of malignant melanoma. BMJ Case Rep. 2013. doi:10.1136/bcr-2013-008566.

- Kwak J, Gallagher M, Ozdener MH, et al. Volatile biomarkers from human melanoma cells. J Chromotogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2013;931:90-96.

- D’Amico A, Bono R, Pennazza G, et al. Identification of melanoma with a gas sensor array. Skin Res Technol. 2008;14:226-236.

- Elliker KR, Williams HC. Detection of skin cancer odours using dogs: a step forward in melanoma detection training and research methodologies. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175:851-852.

- Angle C, Waggoner LP, Ferrando A, et al. Canine detection of the volatilome: a review of implications for pathogen and disease detection. Front Vet Sci. 2016;3:47.

- Pickel D, Mauncy GP, Walker DB, et al. Evidence for canine olfactory detection of melanoma. Applied Animal Behaviour Science. 2004;89:107-116.

- Willis CM, Britton LE, Swindells MA, et al. Invasive melanoma in vivo can be distinguished from basal cell carcinoma, benign naevi and healthy skin by canine olfaction: a proof‐of‐principle study of differential volatile organic compound emission. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175:1020-1029.

- Jezierski T, Walczak M, Ligor T, et al. Study of the art: canine olfaction used for cancer detection on the basis of breath odour. perspectives and limitations. J Breath Res. 2015;9:027001.

- Williams H, Pembroke A. Sniffer dogs in the melanoma clinic? Lancet. 1989;1:734.

- Campbell LF, Farmery L, George SM, et al. Canine olfactory detection of malignant melanoma. BMJ Case Rep. 2013. doi:10.1136/bcr-2013-008566.

- Kwak J, Gallagher M, Ozdener MH, et al. Volatile biomarkers from human melanoma cells. J Chromotogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2013;931:90-96.

- D’Amico A, Bono R, Pennazza G, et al. Identification of melanoma with a gas sensor array. Skin Res Technol. 2008;14:226-236.

- Elliker KR, Williams HC. Detection of skin cancer odours using dogs: a step forward in melanoma detection training and research methodologies. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175:851-852.

Practice Points

- Physiologic and pathologic processes produce volatile organic compounds in the skin and other tissues.

- Malignant melanocytes release unique volatile organic compounds (VOCs) as well as differing combinations and quantities of VOCs as compared to normal melanocytes.

- Volatile organic compounds released at the skin’s surface can be detected by various methods, including canine olfaction; therefore, unusual canine behavior toward skin lesions should not be ignored.

Noninvasive Imaging Tools in Dermatology

Traditionally, diagnosis of skin disease relies on clinical inspection, often followed by biopsy and histopathologic examination. In recent years, new noninvasive tools have emerged that can aid in clinical diagnosis and reduce the number of unnecessary benign biopsies. Although there has been a surge in noninvasive diagnostic technologies, many tools are still in research and development phases, with few tools widely adopted and used in regular clinical practice. In this article, we discuss the use of dermoscopy, reflectance confocal microscopy (RCM), and optical coherence tomography (OCT) in the diagnosis and management of skin disease.

Dermoscopy

Dermoscopy, also known as epiluminescence light microscopy and previously known as dermatoscopy, utilizes a ×10 to ×100 microscope objective with a light source to magnify and visualize structures present below the skin’s surface, such as melanin and blood vessels. There are 3 types of dermoscopy: conventional nonpolarized dermoscopy, polarized contact dermoscopy, and nonpolarized contact dermoscopy (Figure 1). Traditional nonpolarized dermoscopy requires a liquid medium and direct contact with the skin, and it relies on light reflection and refraction properties.1 Cross-polarized light sources allow visualization of deeper structures, either with or without a liquid medium and contact with the skin surface. Although there is overall concurrence among the different types of dermoscopy, subtle differences in the appearance of color, features, and structure are present.1

Dermoscopy offers many benefits for dermatologists and other providers. It can be used to aid in the diagnosis of cutaneous neoplasms and other skin diseases. Numerous low-cost dermatoscopes currently are commercially available. The handheld, easily transportable nature of dermatoscopes have resulted in widespread practice integration. Approximately 84% of attending dermatologists in US academic settings reported using dermoscopy, and many refer to the dermatoscope as “the dermatologist’s stethoscope.”2 In addition, 6% to 15% of other US providers, including family physicians, internal medicine physicians, and plastic surgeons, have reported using dermoscopy in their clinical practices. Limitations of dermoscopy include visualization of the skin surface only and not deeper structures within the tissue, the need for training for adequate interpretation of dermoscopic images, and lack of reimbursement for dermoscopic examination.3

Many dermoscopic structures that correspond well with histopathology have been described. Dermoscopy has a sensitivity of 79% to 96% and specificity of 69% to 99% in the diagnosis of melanoma.4 There is variable data on the specificity of dermoscopy in the diagnosis of melanoma, with one meta-analysis finding no statistically significant difference in specificity compared to naked eye examination,5 while other studies report increased specificity and subsequent reduction in biopsy of benign lesions.6,7 Dermoscopy also can aid in the diagnosis of keratinocytic neoplasms, and dermoscopy also results in a sensitivity of 78.6% to 100% and a specificity of 53.8% to 100% in the diagnosis of basal cell carcinoma (BCC).8 Limitations of dermoscopy include false-positive diagnoses, commonly seborrheic keratoses and nevi, resulting in unnecessary biopsies, as well as false-negative diagnoses, commonly amelanotic and nevoid melanoma, resulting in delays in skin cancer diagnosis and resultant poor outcomes.9 Dermoscopy also is used to aid in the diagnosis of inflammatory and infectious skin diseases, as well as scalp, hair, and nail disorders.10

Reflectance Confocal Microscopy

Reflectance confocal microscopy utilizes an 830-nm laser to capture horizontal en face images of the skin with high resolution. Different structures of the skin have varying indices of refraction: keratin, melanin, and collagen appear bright white, while other components appear dark, generating black-and-white RCM images.11 Currently, there are 2 reflectance confocal microscopes that are commercially available in the United States. The Vivascope 1500 (Caliber ID) is the traditional model that captures 8×8-mm images, and the Vivascope 3000 (Caliber ID) is a smaller handheld model that captures 0.5×0.5-mm images. The traditional model provides the advantages of higher-resolution images and the ability to capture larger surface areas but is best suited to image flat areas of skin to which a square window can be adhered. The handheld model allows improved contact with the varying topography of skin; does not require an adhesive window; and can be used to image cartilaginous, mucosal, and sensitive surfaces. However, it can be difficult to correlate individual images captured by the handheld RCM with the location relative to the lesion, as it is exquisitely sensitive to motion and also is operator dependent. Although complex algorithms are under development to stitch individual images to provide better correlation with the geography of the lesion, such programs are not yet widely available.12

Reflectance confocal microscopy affords many benefits for patients and providers. It is noninvasive and painless and is capable of imaging in vivo live skin as compared to clinical examination and dermoscopy, which only allow for visualization of the skin’s surface. Reflectance confocal microscopy also is time efficient, as imaging of a single lesion can be completed in 10 to 15 minutes. This technology generates high-resolution images, and RCM diagnosis has consistently demonstrated high sensitivity and specificity when compared to histopathology.13 Additionally, RCM imaging can spare biopsy and resultant scarring on cosmetically sensitive areas. Recently, RCM imaging of the skin has been granted Category I Current Procedural Terminology reimbursement codes that allow provider reimbursement and integration of RCM into daily practice14; however, private insurance coverage in the United States is variable. Limitations of RCM include a maximum depth of 200 to 300 µm, high cost to procure a reflectance confocal microscope, and the need for considerable training and practice to accurately interpret grayscale en face images.15

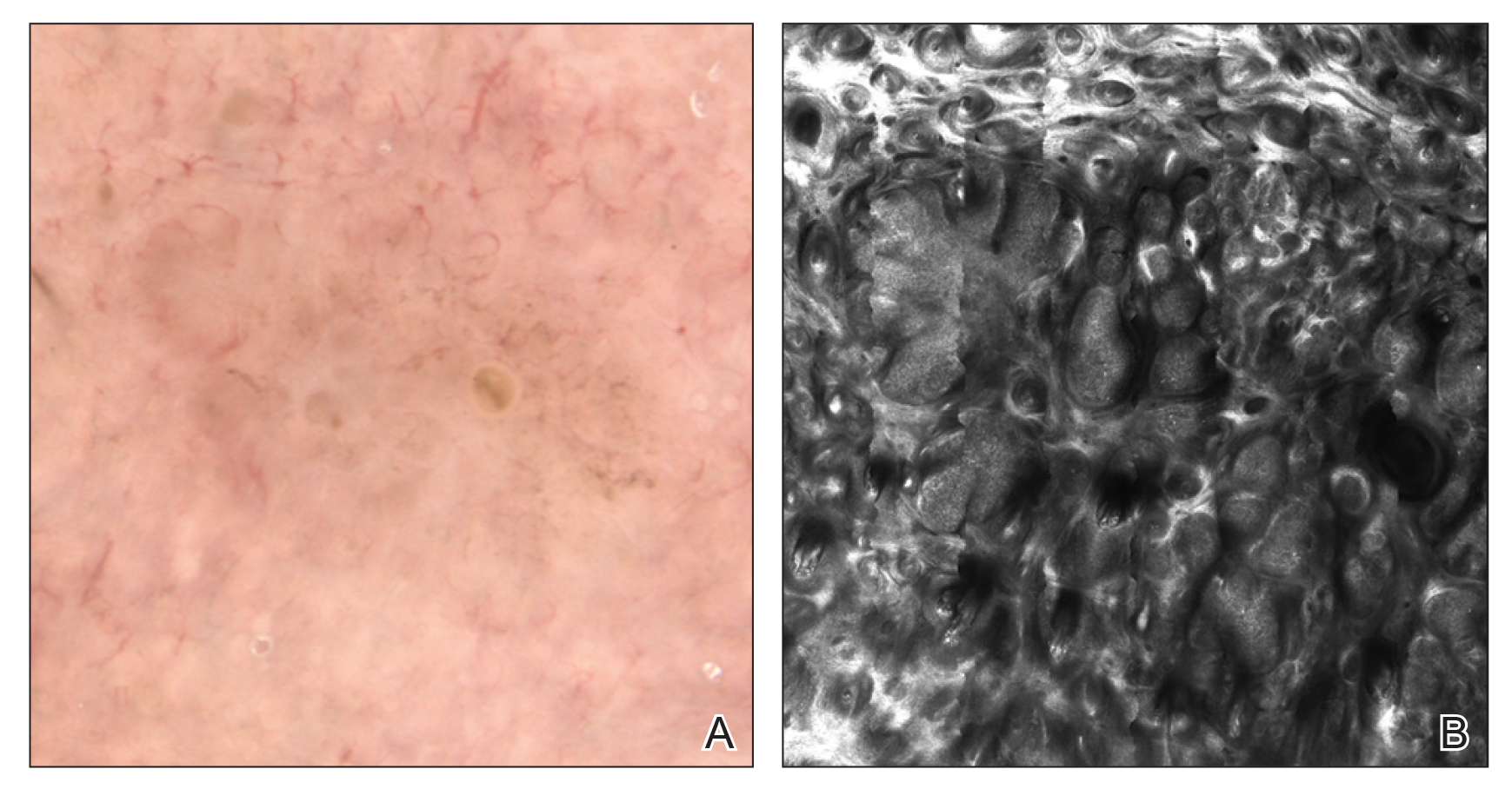

There has been extensive research regarding the use of RCM in the evaluation of cutaneous neoplasms and other skin diseases. Numerous features and patterns have been identified and described that correspond with different skin diseases and correspond well with histopathology (Figure 2).13,16,17 Reflectance confocal microscopy has demonstrated consistently high accuracy in the diagnosis of melanocytic lesions, with a sensitivity of 93% to 100% and a specificity of 75% to 99%.18-21 Reflectance confocal microscopy is especially useful in the evaluation of clinically or dermoscopically equivocal pigmented lesions due to greater specificity, resulting in a reduction of unnecessary biopsies.22,23 It also has high accuracy in the diagnosis of keratinocytic neoplasms, with a sensitivity of 82% to 100% and a specificity of 78% to 97% in the diagnosis of BCC,24 and a sensitivity of 74% to 100% and specificity of 78% to 100% in the diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC).25,26 Evaluation of SCC and actinic keratosis (AK) using RCM may be limited by considerable hyperkeratosis and ulceration. In addition, it can be challenging to differentiate AK and SCC on RCM, and considerable expertise is required to accurately grade cytologic and architectural atypia.27 However, RCM has been used to discriminate between in situ and invasive proliferations.28 Reflectance confocal microscopy has wide applications in the diagnosis and management of cutaneous infections29,30 and inflammatory skin diseases.29,31-33 Recent RCM research explored the use of RCM to identify biopsy sites,34 delineate presurgical tumor margins,35,36 and monitor response to noninvasive treatments.37,38

Optical Coherence Tomography

Optical coherence tomography is an imaging modality that utilizes light backscatter from infrared light to produce grayscale cross-sectional or vertical images and horizontal en face images.39 Optical coherence tomography can visualize structures in the epidermis, dermoepidermal junction, and upper dermis.40 It can image boundaries of structures but cannot visualize individual cells.

There are different types of OCT devices available, including frequency-domain OCT (FD-OCT), or conventional OCT, and high-definition OCT (HD-OCT). With FD-OCT, images are captured at a maximum depth of 1 to 2 mm but with limited resolution. High-definition OCT has superior resolution compared to FD-OCT but is restricted to a shallower depth of 750 μm.39 The main advantage of OCT is the ability to noninvasively image live tissue and visualize 2- to 5-times greater depth as compared to RCM. Several OCT devices have obtained US Food and Drug Administration approval; however, OCT has not been widely adopted into clinical practice and is available only in tertiary academic centers. Additionally, OCT imaging in dermatology is rarely reimbursed. Other limitations of OCT include poor resolution of images, high cost to procure an OCT device, and the need for advanced training and experience to accurately interpret images.40,41

Optical coherence tomography primarily is used to diagnose cutaneous neoplasms. The best evidence of the diagnostic accuracy of OCT is in the setting of BCC, with a recent systematic review reporting a sensitivity of 66% to 96% and a specificity of 75% to 86% for conventional FD-OCT.42 The use of FD-OCT results in an increase in specificity without a significant change in sensitivity when compared to dermoscopy in the diagnosis of BCC.43 Melanoma is difficult to diagnose via FD-OCT, as the visualization of architectural features often is limited by poor resolution.44 A study of HD-OCT in the diagnosis of melanoma with a limited sample size reported a sensitivity of 74% to 80% and a specificity of 92% to 93%.45 Similarly, a study of HD-OCT used in the diagnosis of AK and SCC revealed a sensitivity and specificity of 81.6% and 92.6%, respectively, for AK and 93.8% and 98.9%, respectively, for SCC.46

Numerous algorithms and scoring systems have been developed to further explore the utility of OCT in the diagnosis of cutaneous neoplasms.47,48 Recent research investigated the utility of dynamic OCT, which can evaluate microvasculature in the diagnosis of cutaneous neoplasms (Figure 3)49; the combination of OCT with other imaging modalities50,51; the use of OCT to delineate presurgical margins52,53; and the role of OCT in the diagnosis and monitoring of inflammatory and infectious skin diseases.54,55

Final Thoughts

In recent years, there has been a surge of interest in noninvasive techniques for diagnosis and management of skin diseases; however, noninvasive tools exist on a spectrum in dermatology. Dermoscopy provides low-cost imaging of the skin’s surface and has been widely adopted by dermatologists and other providers to aid in clinical diagnosis. Reflectance confocal microscopy provides reimbursable in vivo imaging of live tissue with cellular-level resolution but is limited by depth, cost, and need for advanced training; thus, RCM has only been adopted in some clinical practices. Optical coherence tomography offers in vivo imaging of live tissue with substantial depth but poor resolution, high cost, need for advanced training, and rare reimbursement for providers. Future directions include combination of complementary imaging modalities, increased clinical practice integration, and education and reimbursement for providers.

- Benvenuto-Andrade C, Dusza SW, Agero AL, et al. Differences between polarized light dermoscopy and immersion contact dermoscopy for the evaluation of skin lesions. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:329-338.

- Terushkin V, Oliveria SA, Marghoob AA, et al. Use of and beliefs about total body photography and dermatoscopy among US dermatology training programs: an update. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:794-803.

- Morris JB, Alfonso SV, Hernandez N, et al. Use of and intentions to use dermoscopy among physicians in the United States. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2017;7:7-16.

- Yélamos O, Braun RP, Liopyris K, et al. Dermoscopy and dermatopathology correlates of cutaneous neoplasms. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:341-363.

- Vestergaard ME, Macaskill P, Holt PE, et al. Dermoscopy compared with naked eye examination for the diagnosis of primary melanoma: a meta-analysis of studies performed in a clinical setting. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:669-676.

- Carli P, de Giorgi V, Chiarugi A, et al. Addition of dermoscopy to conventional naked-eye examination in melanoma screening: a randomized study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:683-668.

- Lallas A, Zalaudek I, Argenziano G, et al. Dermoscopy in general dermatology. Dermatol Clin. 2013;31:679-694.

- Reiter O, Mimouni I, Gdalvevich M, et al. The diagnostic accuracy of dermoscopy for basal cell carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1380-1388.

- Papageorgiou V, Apalla Z, Sotiriou E, et al. The limitations of dermoscopy: false-positive and false-negative tumours. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:879-888.

- Micali G, Verzì AE, Lacarrubba F. Alternative uses of dermoscopy in daily clinical practice: an update. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:1117-1132.e1.

- Rajadhyaksha M, Grossman M, Esterowitz D, et al. In vivo confocal scanning laser microscopy of human skin: melanin provides strong contrast. J Invest Dermatol. 1995;104:946-952.

- Kose K, Gou M, Yélamos O, et al. Automated video-mosaicking approach for confocal microscopic imaging in vivo: an approach to address challenges in imaging living tissue and extend field of view. Sci Rep. 2017;7:10759.

- Rao BK, John AM, Francisco G, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of reflectance confocal microscopy for diagnosis of skin lesions [published online October 8, 2018]. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2019;143:326-329.

- Current Procedural Terminology, Professional Edition. Chicago IL: American Medical Association; 2016. The preliminary physician fee schedule for 2017 is available at https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/PhysicianFeeSched/PFS-Federal-Regulation-Notices-Items/CMS-1654-P.html.

- Jain M, Pulijal SV, Rajadhyaksha M, et al. Evaluation of bedside diagnostic accuracy, learning curve, and challenges for a novice reflectance confocal microscopy reader for skin cancer detection in vivo. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:962-965.

- Rao BK, Pellacani G. Atlas of Confocal Microscopy in Dermatology: Clinical, Confocal, and Histological Images. New York, NY: NIDIskin LLC; 2013.

- Scope A, Benvenuto-Andrande C, Agero AL, et al. In vivo reflectance confocal microscopy imaging of melanocytic skin lesions: consensus terminology glossary and illustrative images. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:644-658.

- Gerger A, Hofmann-Wellenhof R, Langsenlehner U, et al. In vivo confocal laser scanning microscopy of melanocytic skin tumours: diagnostic applicability using unselected tumour images. Br J Dermatol. 2008;158:329-333.

- Stevenson AD, Mickan S, Mallett S, et al. Systematic review of diagnostic accuracy of reflectance confocal microscopy for melanoma diagnosis in patients with clinically equivocal skin lesions. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2013;3:19-27.

- Alarcon I, Carrera C, Palou J, et al. Impact of in vivo reflectance confocal microscopy on the number needed to treat melanoma in doubtful lesions. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:802-808.

- Lovatto L, Carrera C, Salerni G, et al. In vivo reflectance confocal microscopy of equivocal melanocytic lesions detected by digital dermoscopy follow-up. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1918-1925.

- Guitera P, Pellacani G, Longo C, et al. In vivo reflectance confocal microscopy enhances secondary evaluation of melanocytic lesions. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:131-138.

- Xiong YQ, Ma SJ, Mo Y, et al. Comparison of dermoscopy and reflectance confocal microscopy for the diagnosis of malignant skin tumours: a meta-analysis. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2017;143:1627-1635.

- Kadouch DJ, Schram ME, Leeflang MM, et al. In vivo confocal microscopy of basal cell carcinoma: a systematic review of diagnostic accuracy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1890-1897.

- Dinnes J, Deeks JJ, Chuchu N, et al; Cochrane Skin Cancer Diagnostic Test Accuracy Group. Reflectance confocal microscopy for diagnosing keratinocyte skin cancers in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;12:CD013191.

- Nguyen KP, Peppelman M, Hoogedoorn L, et al. The current role of in vivo reflectance confocal microscopy within the continuum of actinic keratosis and squamous cell carcinoma: a systematic review. Eur J Dermatol. 2016;26:549-565.

- Pellacani G, Ulrich M, Casari A, et al. Grading keratinocyte atypia in actinic keratosis: a correlation of reflectance confocal microscopy and histopathology. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:2216-2221.

- Manfredini M, Longo C, Ferrari B, et al. Dermoscopic and reflectance confocal microscopy features of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:1828-1833.

- Hoogedoorn L, Peppelman M, van de Kerkhof PC, et al. The value of in vivo reflectance confocal microscopy in the diagnosis and monitoring of inflammatory and infectious skin diseases: a systematic review. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172:1222-1248.

- Cinotti E, Perrot JL, Labeille B, et al. Reflectance confocal microscopy for cutaneous infections and infestations. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:754-763.

- Ardigo M, Longo C, Gonzalez S; International Confocal Working Group Inflammatory Skin Diseases Project. Multicentre study on inflammatory skin diseases from The International Confocal Working Group: specific confocal microscopy features and an algorithmic method of diagnosis. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175:364-374.

- Ardigo M, Agozzino M, Franceschini C, et al. Reflectance confocal microscopy algorithms for inflammatory and hair diseases. Dermatol Clin. 2016;34:487-496.

- Manfredini M, Bettoli V, Sacripanti G, et al. The evolution of healthy skin to acne lesions: a longitudinal, in vivo evaluation with reflectance confocal microscopy and optical coherence tomography [published online April 26, 2019]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. doi:10.1111/jdv.15641.

- Navarrete-Dechent C, Mori S, Cordova M, et al. Reflectance confocal microscopy as a novel tool for presurgical identification of basal cell carcinoma biopsy site. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:e7-e8.

- Pan ZY, Lin JR, Cheng TT, et al. In vivo reflectance confocal microscopy of basal cell carcinoma: feasibility of preoperative mapping of cancer margins. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38:1945-1950.

- Venturini M, Gualdi G, Zanca A, et al. A new approach for presurgical margin assessment by reflectance confocal microscopy of basal cell carcinoma. Br J Dermatol. 2016;174:380-385.

- Sierra H, Yélamos O, Cordova M, et al. Reflectance confocal microscopy‐guided laser ablation of basal cell carcinomas: initial clinical experience. J Biomed Opt. 2017;22:1-13.

- Maier T, Kulichova D, Ruzicka T, et al. Noninvasive monitoring of basal cell carcinomas treated with systemic hedgehog inhibitors: pseudocysts as a sign of tumor regression. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:725-730.

- Levine A, Wang K, Markowitz O. Optical coherence tomography in the diagnosis of skin cancer. Dermatol Clin. 2017;35:465-488.

- Schneider SL, Kohli I, Hamzavi IH, et al. Emerging imaging technologies in dermatology: part I: basic principles. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1114-1120.

- Mogensen M, Joergensen TM, Nümberg BM, et al. Assessment of optical coherence tomography imaging in the diagnosis of non‐melanoma skin cancer and benign lesions versus normal skin: observer‐blinded evaluation by dermatologists and pathologists. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:965-972.

- Ferrante di Ruffano L, Dinnes J, Deeks JJ, et al. Optical coherence tomography for diagnosing skin cancer in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;12:CD013189.

- Ulrich M, von Braunmuehl T, Kurzen H, et al. The sensitivity and specificity of optical coherence tomography for the assisted diagnosis of nonpigmented basal cell carcinoma: an observational study. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173:428-435.

- Wessels R, de Bruin DM, Relyveld GM, et al. Functional optical coherence tomography of pigmented lesions. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:738‐744.

- Gambichler T, Schmid-Wendtner MH, Plura I, et al. A multicentre pilot study investigating high‐definition optical coherence tomography in the differentiation of cutaneous melanoma and melanocytic naevi. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:537‐541.

- Marneffe A, Suppa M, Miyamoto M, et al. Validation of a diagnostic algorithm for the discrimination of actinic keratosis from normal skin and squamous cell carcinoma by means of high-definition optical coherence tomography. Exp Dermatol. 2016;25:684-687.

- Boone MA, Suppa M, Dhaenens F, et al. In vivo assessment of optical properties of melanocytic skin lesions and differentiation of melanoma from non-malignant lesions by high-definition optical coherence tomography. Arch Dermatol Res. 2016;308:7-20.

- Boone MA, Suppa M, Marneffe A, et al. A new algorithm for the discrimination of actinic keratosis from normal skin and squamous cell carcinoma based on in vivo analysis of optical properties by high-definition optical coherence tomography. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:1714-1725.

- Themstrup L, Pellacani G, Welzel J, et al. In vivo microvascular imaging of cutaneous actinic keratosis, Bowen’s disease and squamous cell carcinoma using dynamic optical coherence tomography. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:1655-1662.

- Alex A, Weingast J, Weinigel M, et al. Three-dimensional multiphoton/optical coherence tomography for diagnostic applications in dermatology. J Biophotonics. 2013;6:352-362.

- Iftimia N, Yélamos O, Chen CJ, et al. Handheld optical coherence tomography-reflectance confocal microscopy probe for detection of basal cell carcinoma and delineation of margins. J Biomed Opt. 2017;22:76006.

- Wang KX, Meekings A, Fluhr JW, et al. Optical coherence tomography-based optimization of Mohs micrographic surgery of basal cell carcinoma: a pilot study. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:627-633.

- Chan CS, Rohrer TE. Optical coherence tomography and its role in Mohs micrographic surgery: a case report. Case Rep Dermatol. 2012;4:269-274.

- Gambichler T, Jaedicke V, Terras S. Optical coherence tomography in dermatology: technical and clinical aspects. Arch Dermatol Res. 2011;303:457-473.

- Manfredini M, Greco M, Farnetani F, et al. Acne: morphologic and vascular study of lesions and surrounding skin by means of optical coherence tomography. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:1541-1546.

Traditionally, diagnosis of skin disease relies on clinical inspection, often followed by biopsy and histopathologic examination. In recent years, new noninvasive tools have emerged that can aid in clinical diagnosis and reduce the number of unnecessary benign biopsies. Although there has been a surge in noninvasive diagnostic technologies, many tools are still in research and development phases, with few tools widely adopted and used in regular clinical practice. In this article, we discuss the use of dermoscopy, reflectance confocal microscopy (RCM), and optical coherence tomography (OCT) in the diagnosis and management of skin disease.

Dermoscopy

Dermoscopy, also known as epiluminescence light microscopy and previously known as dermatoscopy, utilizes a ×10 to ×100 microscope objective with a light source to magnify and visualize structures present below the skin’s surface, such as melanin and blood vessels. There are 3 types of dermoscopy: conventional nonpolarized dermoscopy, polarized contact dermoscopy, and nonpolarized contact dermoscopy (Figure 1). Traditional nonpolarized dermoscopy requires a liquid medium and direct contact with the skin, and it relies on light reflection and refraction properties.1 Cross-polarized light sources allow visualization of deeper structures, either with or without a liquid medium and contact with the skin surface. Although there is overall concurrence among the different types of dermoscopy, subtle differences in the appearance of color, features, and structure are present.1

Dermoscopy offers many benefits for dermatologists and other providers. It can be used to aid in the diagnosis of cutaneous neoplasms and other skin diseases. Numerous low-cost dermatoscopes currently are commercially available. The handheld, easily transportable nature of dermatoscopes have resulted in widespread practice integration. Approximately 84% of attending dermatologists in US academic settings reported using dermoscopy, and many refer to the dermatoscope as “the dermatologist’s stethoscope.”2 In addition, 6% to 15% of other US providers, including family physicians, internal medicine physicians, and plastic surgeons, have reported using dermoscopy in their clinical practices. Limitations of dermoscopy include visualization of the skin surface only and not deeper structures within the tissue, the need for training for adequate interpretation of dermoscopic images, and lack of reimbursement for dermoscopic examination.3

Many dermoscopic structures that correspond well with histopathology have been described. Dermoscopy has a sensitivity of 79% to 96% and specificity of 69% to 99% in the diagnosis of melanoma.4 There is variable data on the specificity of dermoscopy in the diagnosis of melanoma, with one meta-analysis finding no statistically significant difference in specificity compared to naked eye examination,5 while other studies report increased specificity and subsequent reduction in biopsy of benign lesions.6,7 Dermoscopy also can aid in the diagnosis of keratinocytic neoplasms, and dermoscopy also results in a sensitivity of 78.6% to 100% and a specificity of 53.8% to 100% in the diagnosis of basal cell carcinoma (BCC).8 Limitations of dermoscopy include false-positive diagnoses, commonly seborrheic keratoses and nevi, resulting in unnecessary biopsies, as well as false-negative diagnoses, commonly amelanotic and nevoid melanoma, resulting in delays in skin cancer diagnosis and resultant poor outcomes.9 Dermoscopy also is used to aid in the diagnosis of inflammatory and infectious skin diseases, as well as scalp, hair, and nail disorders.10

Reflectance Confocal Microscopy

Reflectance confocal microscopy utilizes an 830-nm laser to capture horizontal en face images of the skin with high resolution. Different structures of the skin have varying indices of refraction: keratin, melanin, and collagen appear bright white, while other components appear dark, generating black-and-white RCM images.11 Currently, there are 2 reflectance confocal microscopes that are commercially available in the United States. The Vivascope 1500 (Caliber ID) is the traditional model that captures 8×8-mm images, and the Vivascope 3000 (Caliber ID) is a smaller handheld model that captures 0.5×0.5-mm images. The traditional model provides the advantages of higher-resolution images and the ability to capture larger surface areas but is best suited to image flat areas of skin to which a square window can be adhered. The handheld model allows improved contact with the varying topography of skin; does not require an adhesive window; and can be used to image cartilaginous, mucosal, and sensitive surfaces. However, it can be difficult to correlate individual images captured by the handheld RCM with the location relative to the lesion, as it is exquisitely sensitive to motion and also is operator dependent. Although complex algorithms are under development to stitch individual images to provide better correlation with the geography of the lesion, such programs are not yet widely available.12

Reflectance confocal microscopy affords many benefits for patients and providers. It is noninvasive and painless and is capable of imaging in vivo live skin as compared to clinical examination and dermoscopy, which only allow for visualization of the skin’s surface. Reflectance confocal microscopy also is time efficient, as imaging of a single lesion can be completed in 10 to 15 minutes. This technology generates high-resolution images, and RCM diagnosis has consistently demonstrated high sensitivity and specificity when compared to histopathology.13 Additionally, RCM imaging can spare biopsy and resultant scarring on cosmetically sensitive areas. Recently, RCM imaging of the skin has been granted Category I Current Procedural Terminology reimbursement codes that allow provider reimbursement and integration of RCM into daily practice14; however, private insurance coverage in the United States is variable. Limitations of RCM include a maximum depth of 200 to 300 µm, high cost to procure a reflectance confocal microscope, and the need for considerable training and practice to accurately interpret grayscale en face images.15