User login

Pink Papules on the Cheek

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman Disease

Rosai-Dorfman disease is a rare benign non- Langerhans cell histiocytopathy that can manifest initially with lymph node involvement—classically, massive painless cervical lymphadenopathy.1 Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease (CRDD) is a variant that can be associated with lymph node and internal involvement, but more than 80% of cases lack extracutaneous involvement.2,3 In cases with extracutaneous involvement, lymph node disease is most frequent.3 Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease unassociated with extracutaneous disease is a benign self-limiting histiocytopathy that manifests as painless red-brown, yellow, or fleshcolored nodules, plaques, or papules that may become tender or ulcerated.4

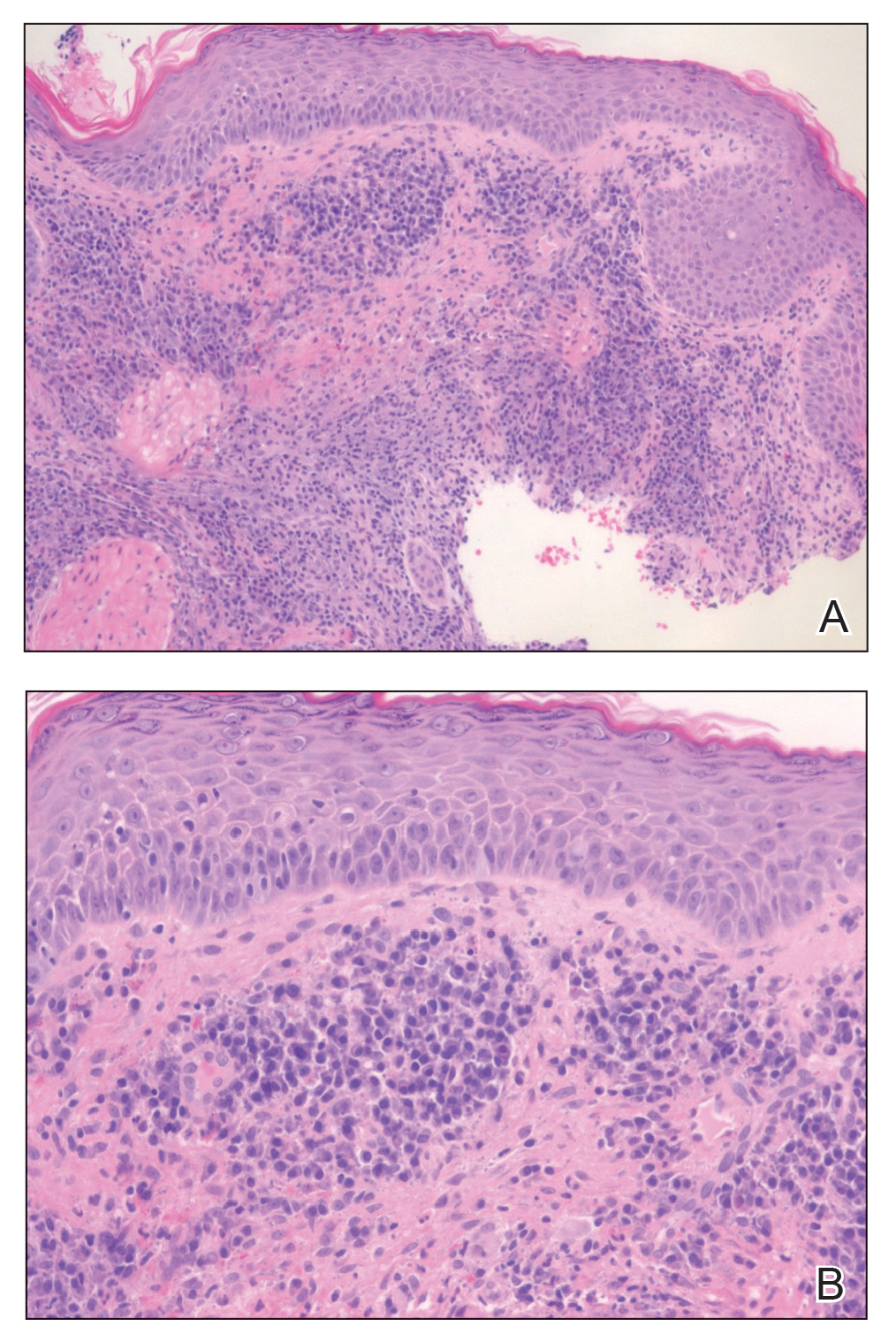

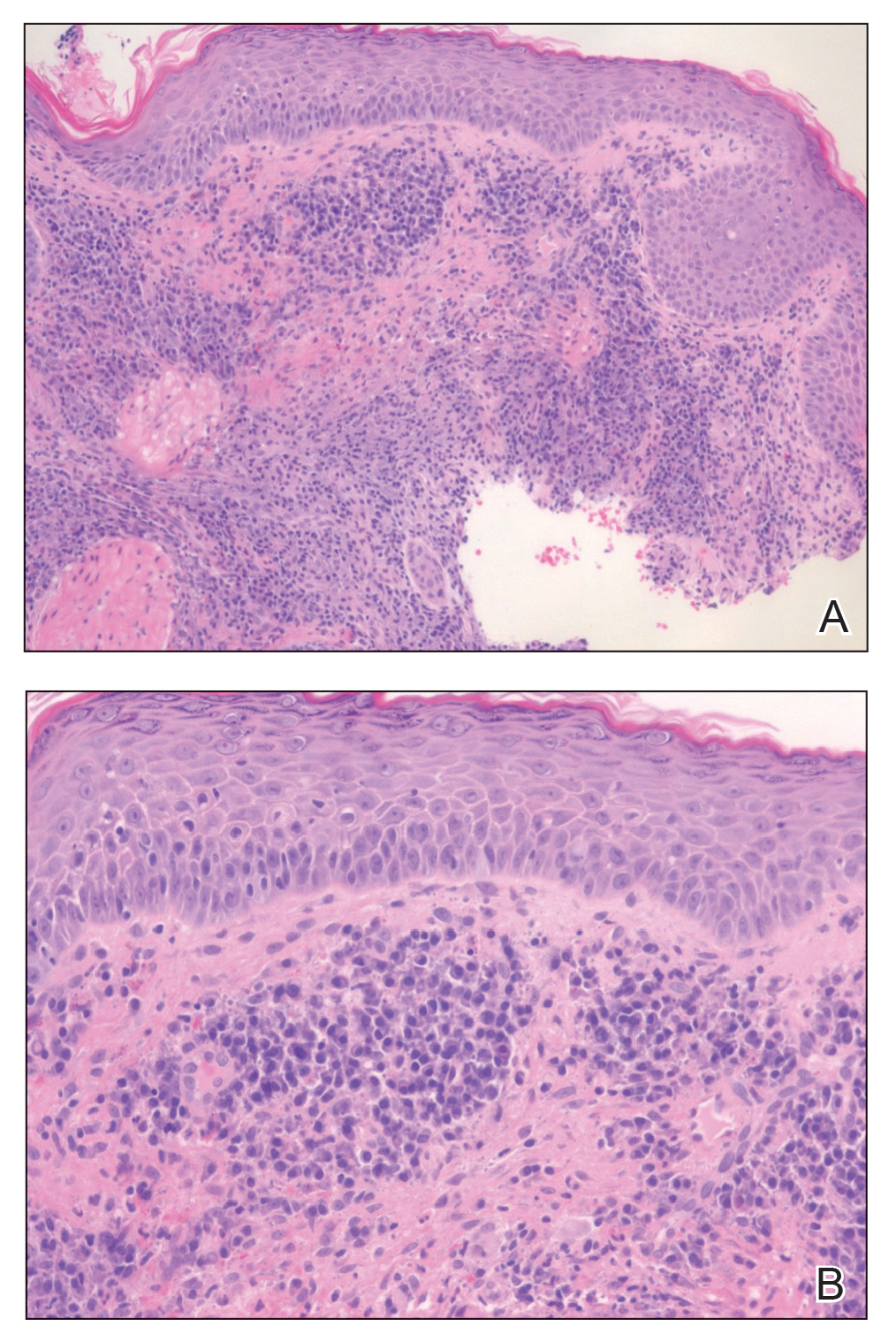

Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease represents a benign histiocytopathy of resident dendritic cell derivation.3 A characteristic immunohistochemical finding is S-100 positivity, which might suggest a Langerhans cell transdifferentiation phenotype, but other markers corroborative of a Langerhans cell phenotype—namely CD1a and langerin—will be negative. Biopsies typically show a mid to deep dermal histiocytic infiltration in a variably dense polymorphous inflammatory cell background comprised of a mixture of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and neutrophils.3 At times the extent of lymphocytic infiltration can be to a magnitude that resembles a lymphoma on histopathology. In our patient, lymphoma was excluded based on clinical presentation, as this patient lacked the typical symptoms of lymphadenopathy or B symptoms that come with B-cell lymphoma.5

The histiocytes in CRDD are characteristically large mononuclear cells exhibiting a low nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio reflective of the voluminous, nonvacuolated, watery cytoplasm. They have ill-defined cytoplasmic membranes resulting in a seemingly syncytial growth pattern. A hallmark of the histiocytes is emperipolesis characterized by intracytoplasmic localization of intact inflammatory cells including neutrophils, lymphocytes, and plasma cells.3

The differential diagnosis of CRDD includes Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH), indeterminate cell histiocytosis, xanthogranuloma, and reticulohistiocytoma. All of these conditions can be differentiated by their unique histopathologic and phenotypic characteristics.

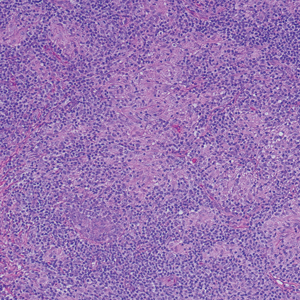

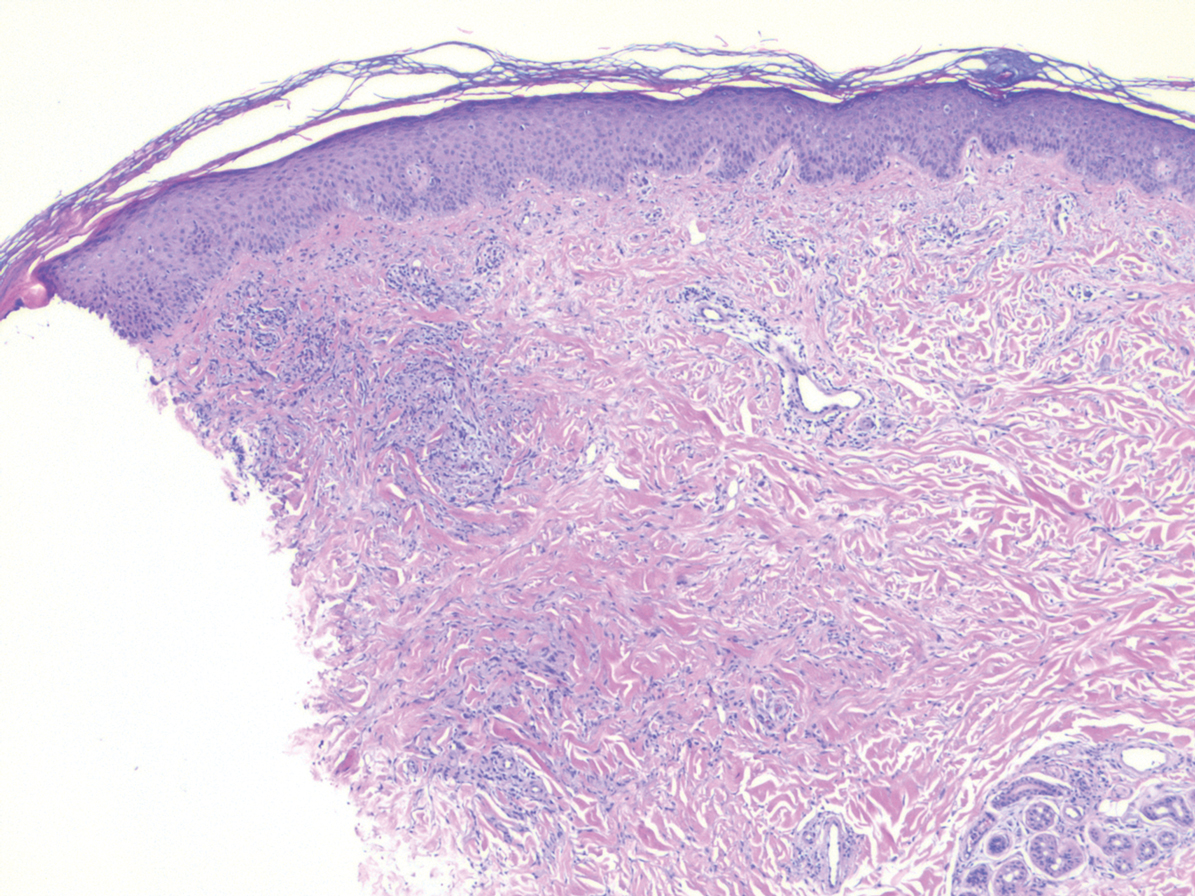

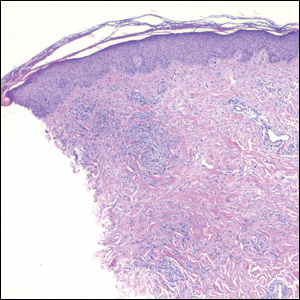

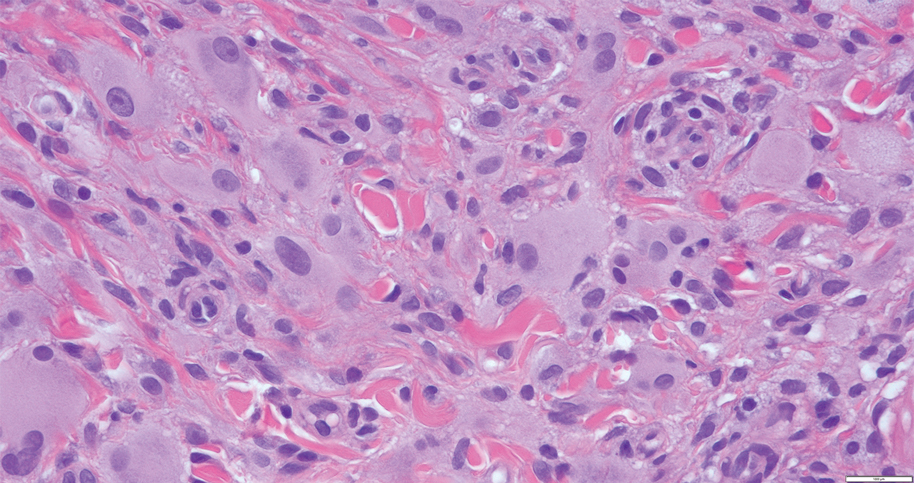

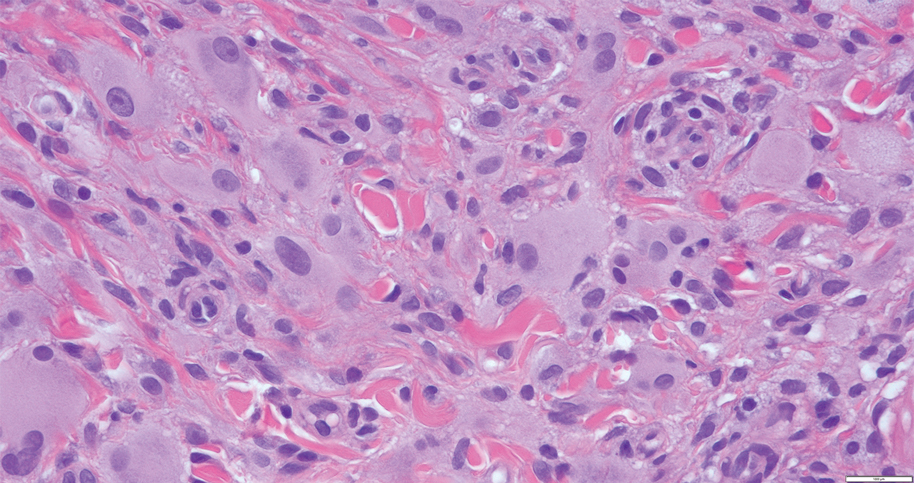

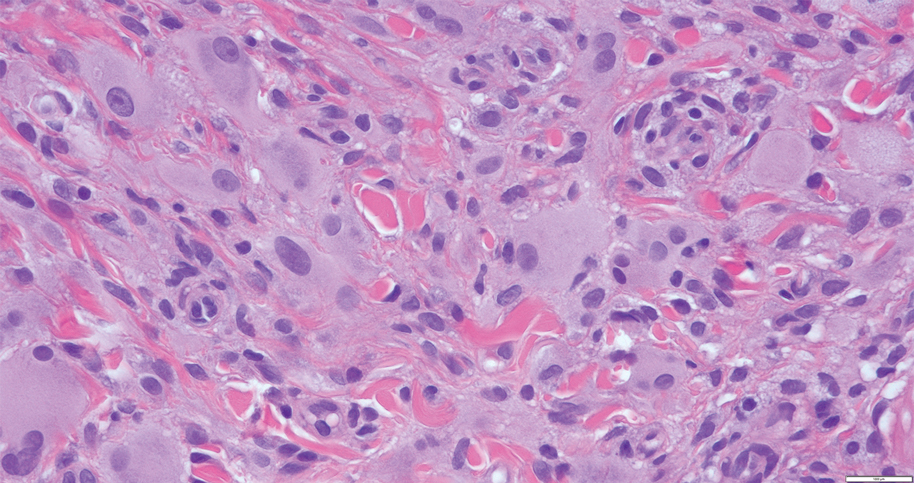

Langerhans cell histiocytosis is a distinct clonal histiocytopathy that has a varied presentation ranging from cutaneous confined cases manifesting as a solitary lesion to one of disseminated cutaneous disease with the potential for multiorgan involvement. Regardless of the variant of LCH, the hallmark cell is one showing an eccentrically disposed, reniform nucleus with an open chromatin and abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm (Figure 1).6 Both LCH and CRDD stain positive for S-100. However, unlike the histiocytes in CRDD, those seen in LCH stain positive for CD1a and langerin and would not express factor XIIIA. Additionally, the neoplastic cells would not exhibit the same extent of CD68 positivity seen in CRDD.6 Treatment of LCH depends on the extent of disease, especially for the presence or absence of extracutaneous disease.7

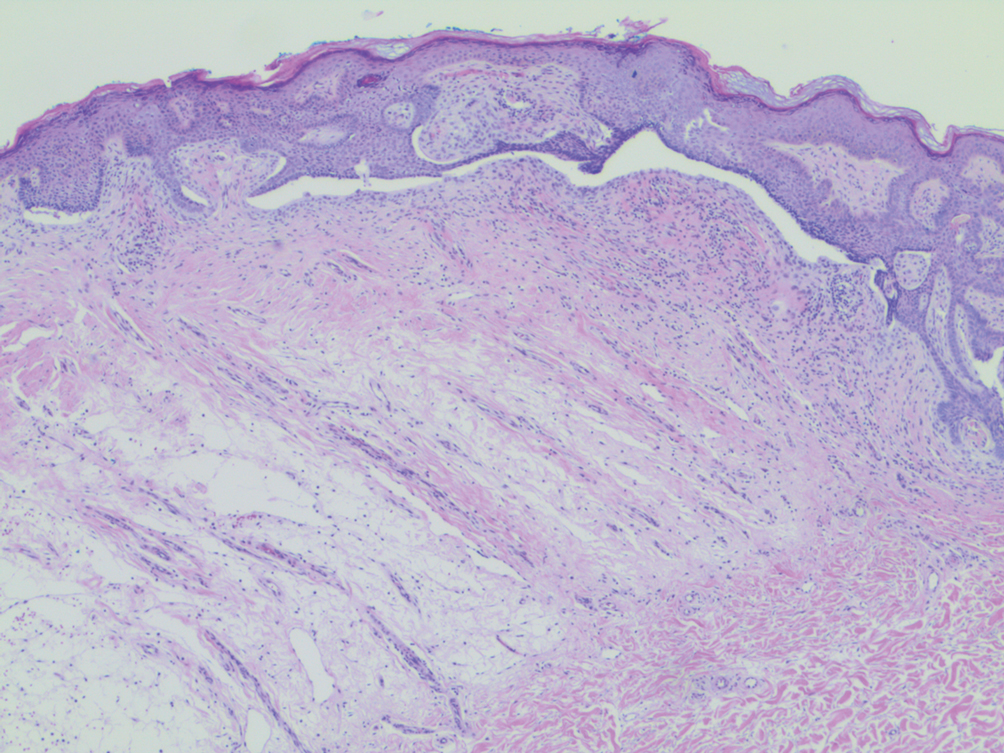

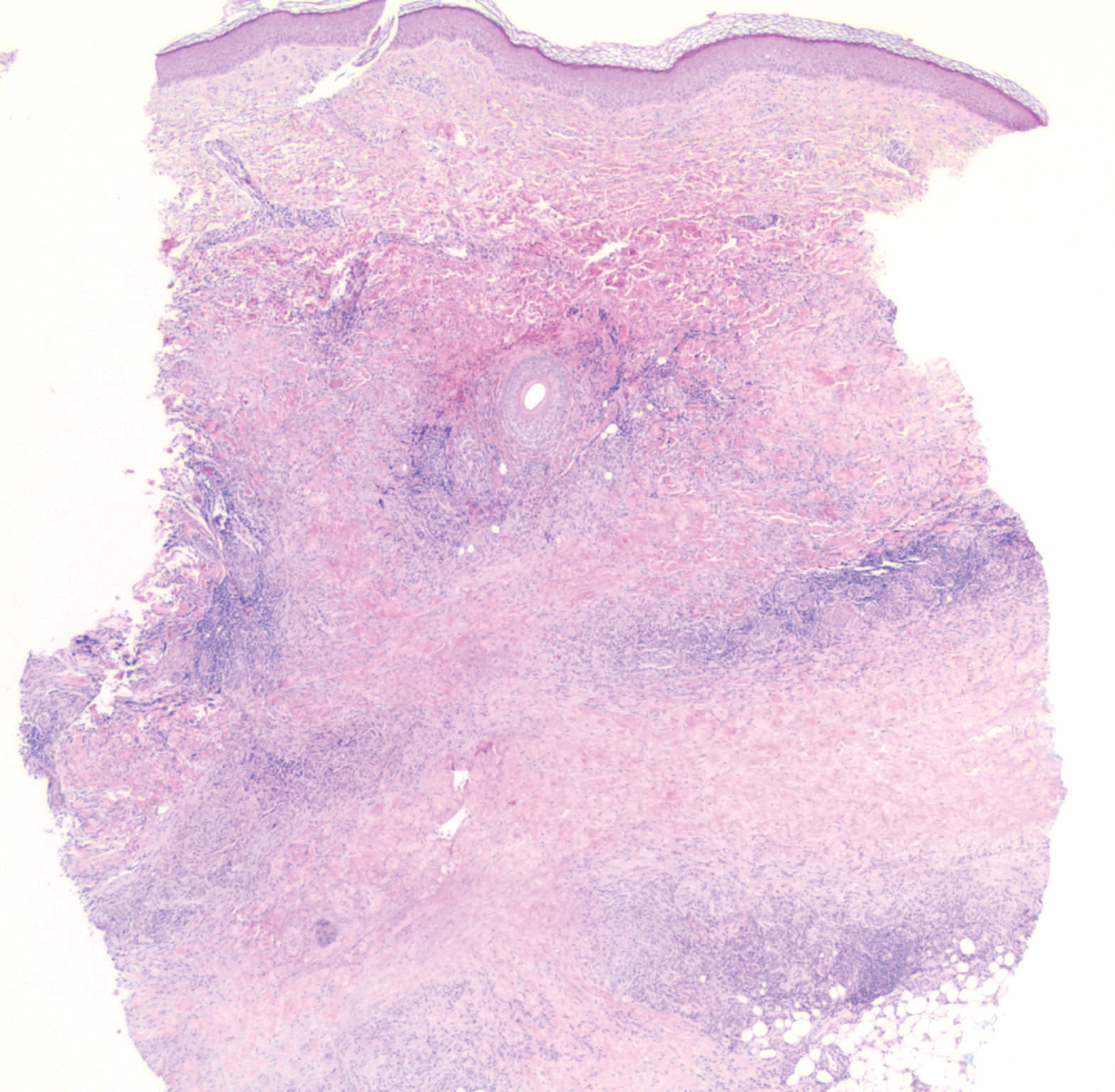

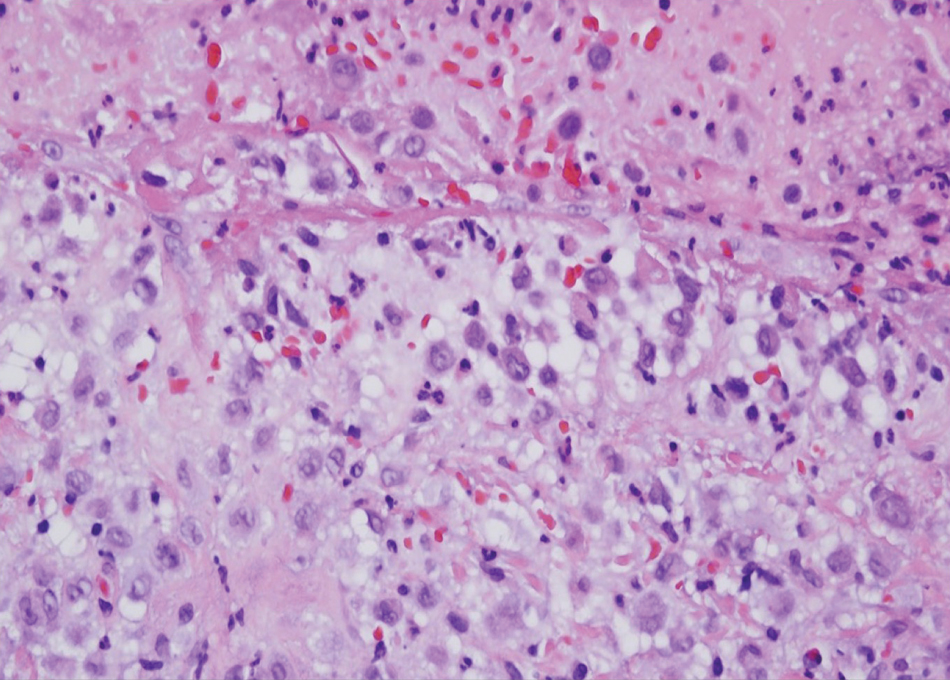

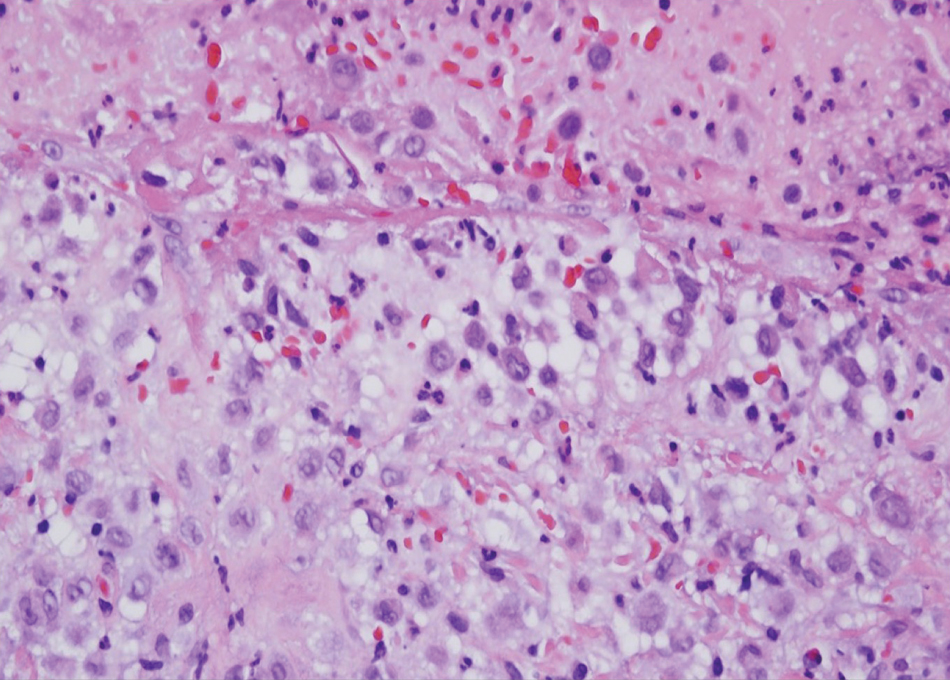

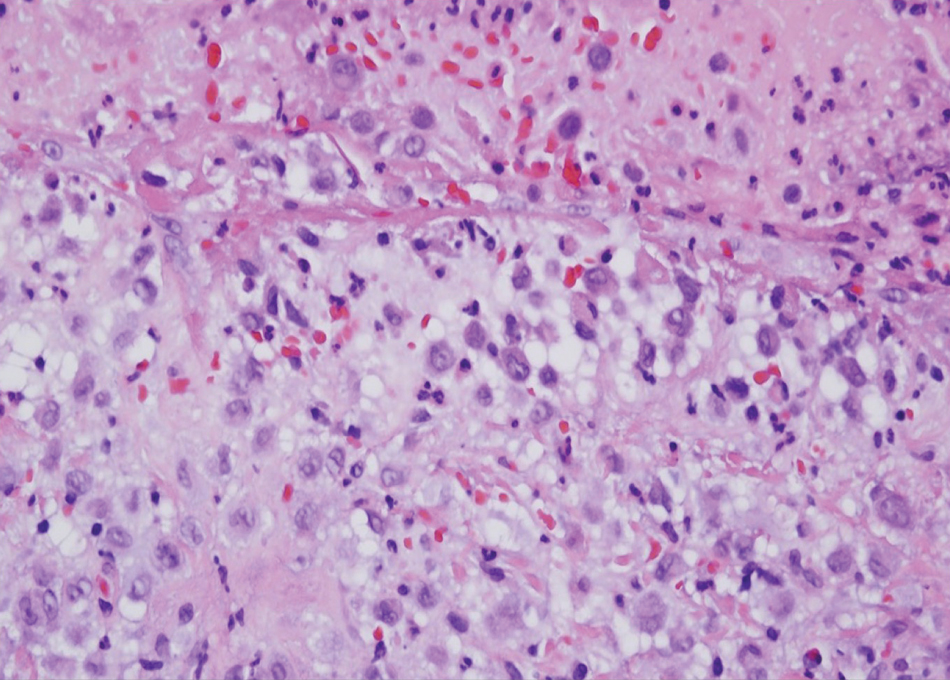

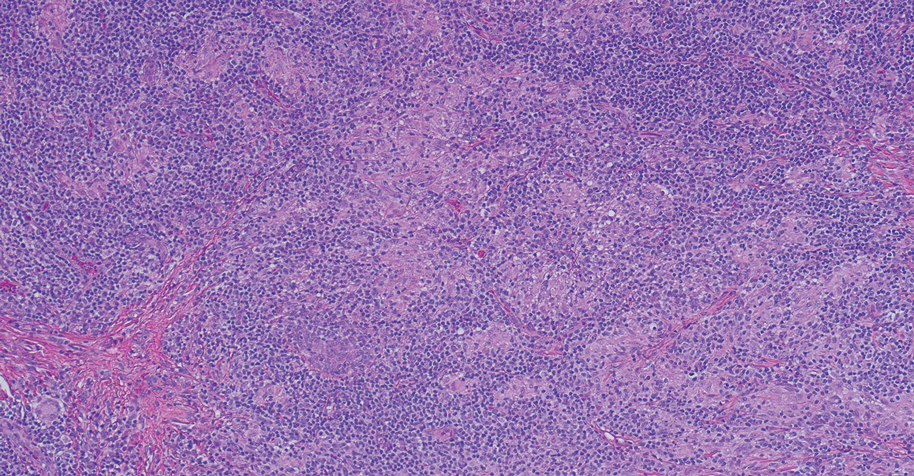

A variant of LCH is indeterminate cell histiocytosis, which can be seen in neonates or adults. It represents a neoplastic proliferation of Langerhans cells that are devoid of Birbeck granules, reflective of an immature early phase of differentiation in the skin prior to the cells acquiring the Birbeck granule (as would be seen in neonates) or a later phase of differentiation after the mature Langerhans cell has encountered antigen and is en route to the lymph node (typically seen in adults).8 The phenotypic profile is identical to conventional LCH except the cells do not express langerin. Microscopically, the infiltrates are composed of Langerhans cells that are morphologically indistinguishable from classic LCH but without epidermotropism and exhibit a dominant localization in the dermis typically unassociated with other inflammatory cell elements (Figure 2).9

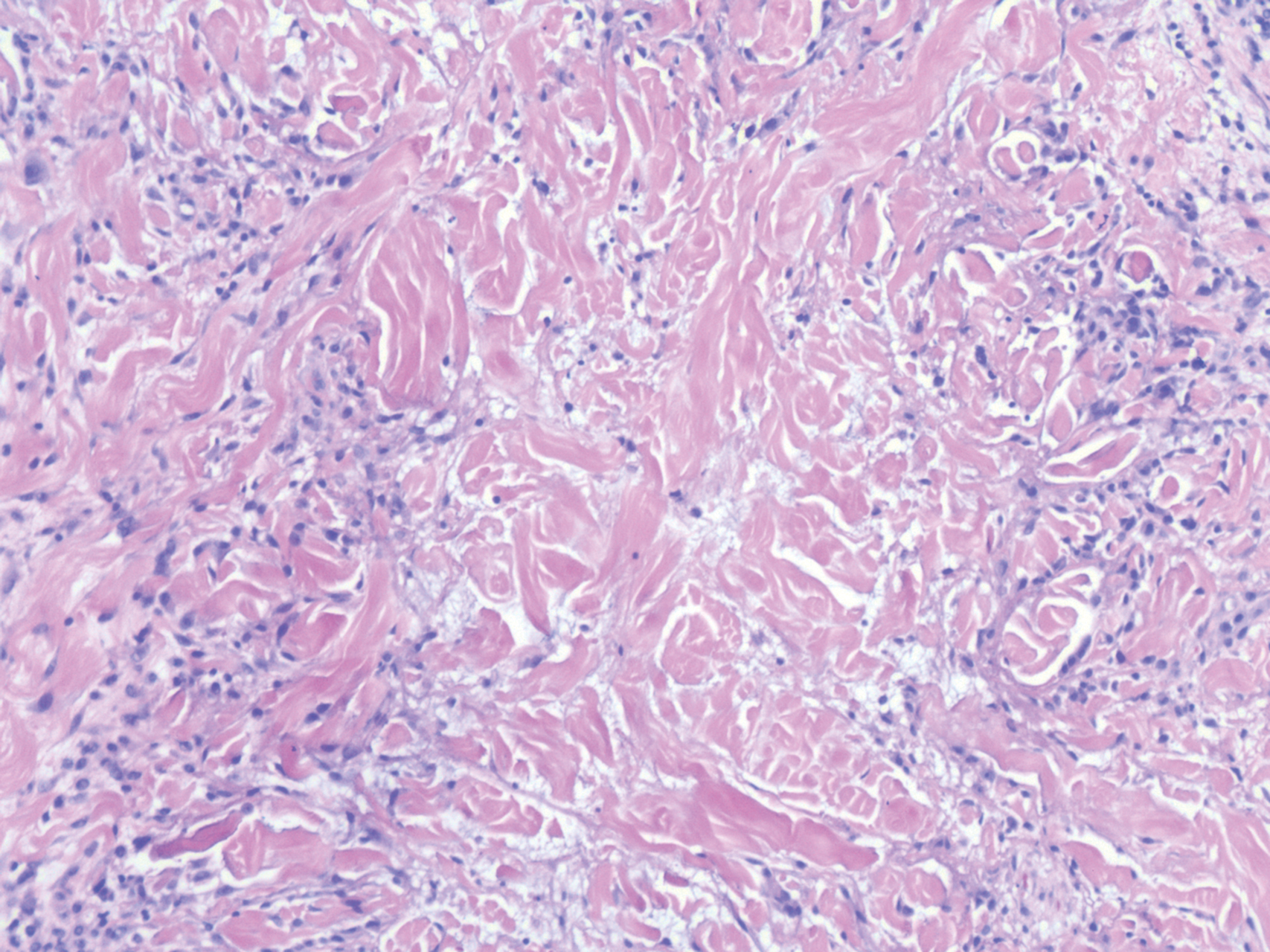

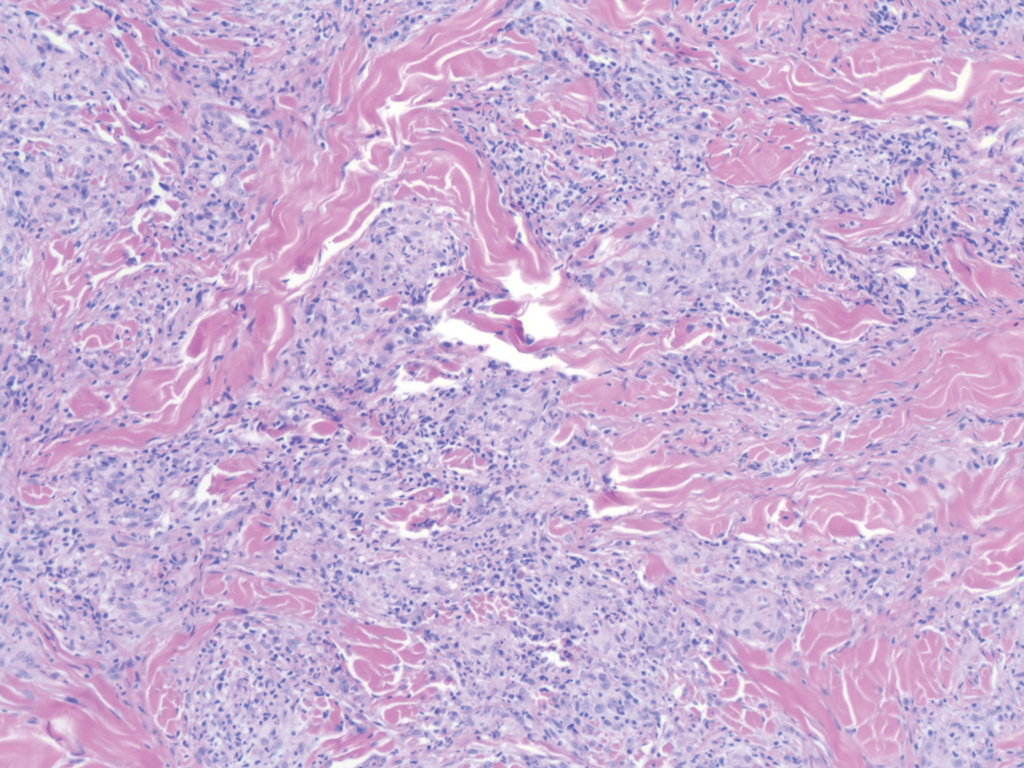

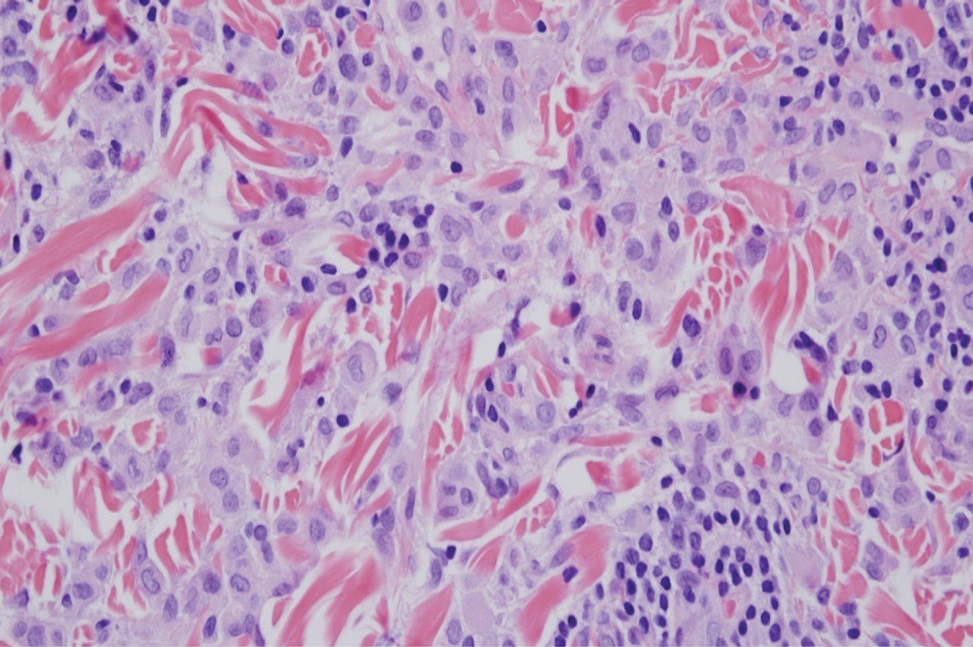

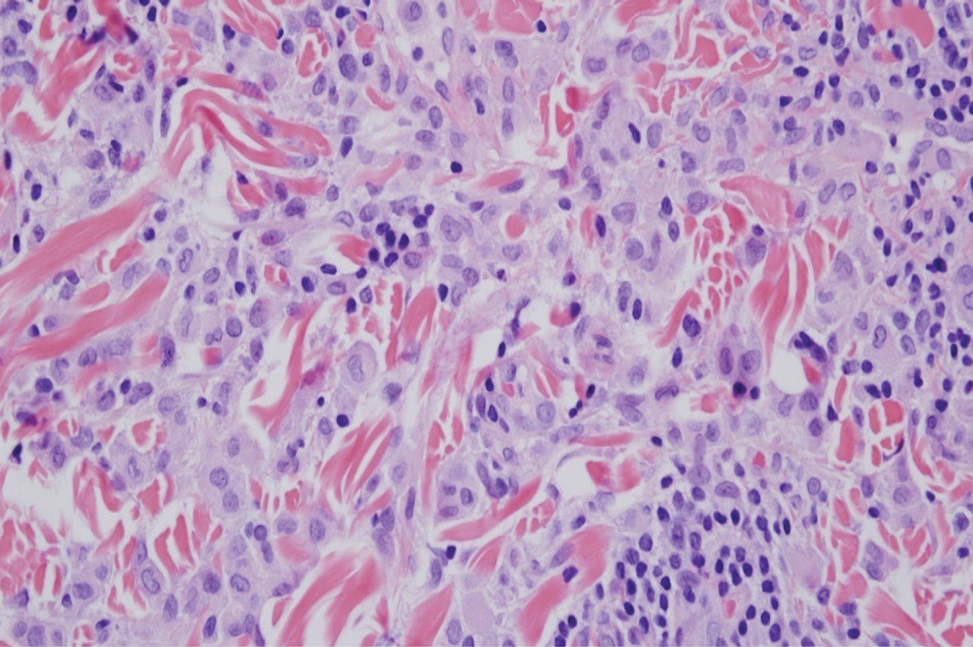

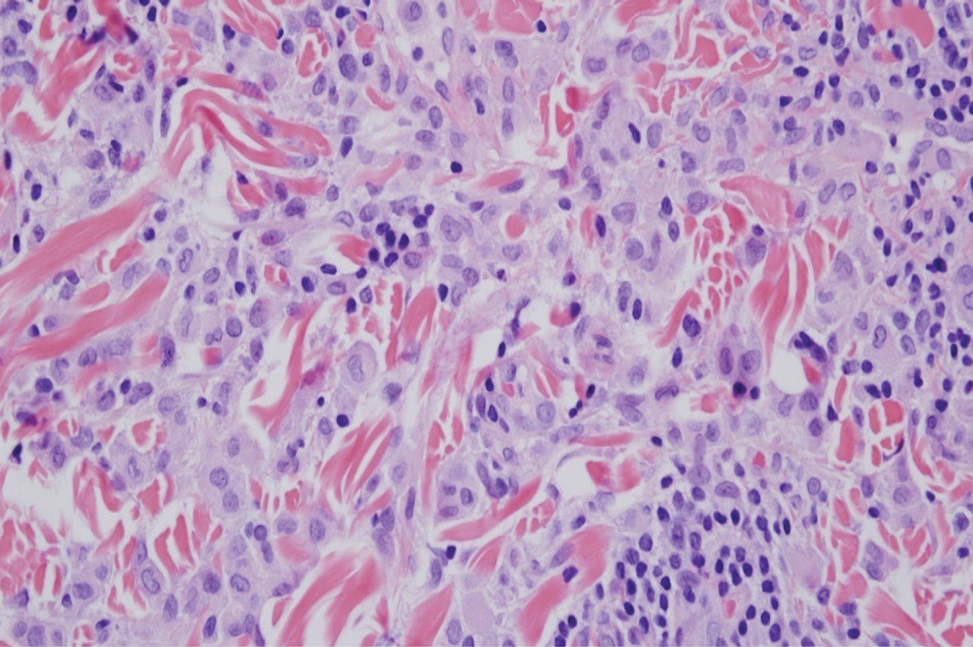

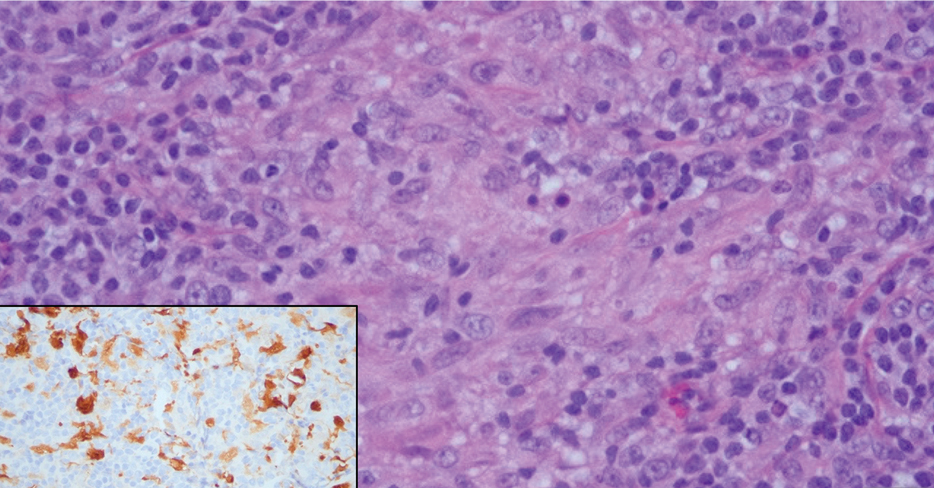

Xanthogranuloma is seen in young children (juvenile xanthogranuloma) as a solitary lesion, though a multifocal cutaneous variant and extracutaneous presentations have been described. Similar lesions can be seen in adults.10 These lesions are evolutionary in their morphology. In the inception of a juvenile xanthogranuloma, the lesions are highly cellular, and the histiocytes typically are poorly lipidized; there may be a dearth of other inflammatory cell elements. As the lesions mature, the histiocytes become lipidized, and characteristic Touton giant cells that exhibit a wreath of nuclei with peripheral lipidization may develop (Figure 3). In the later stages, there is considerable hyalinizing fibrosis, and the cells can acquire a spindled appearance. The absence of emperipolesis and the presence of notable lipidization are useful light microscopy features differentiating xanthogranuloma from CRDD.11 Treatment of xanthogranuloma can range from a conservative monitoring approach to an aggressive approach combining various antineoplastic therapies with immunosuppressive agents.12

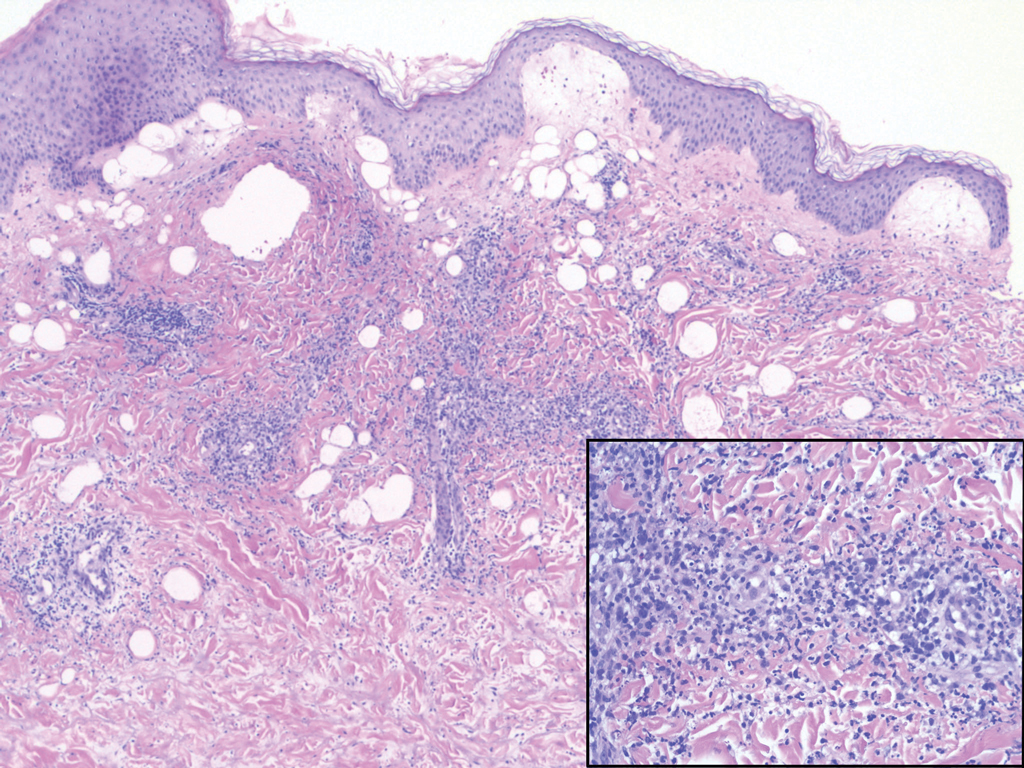

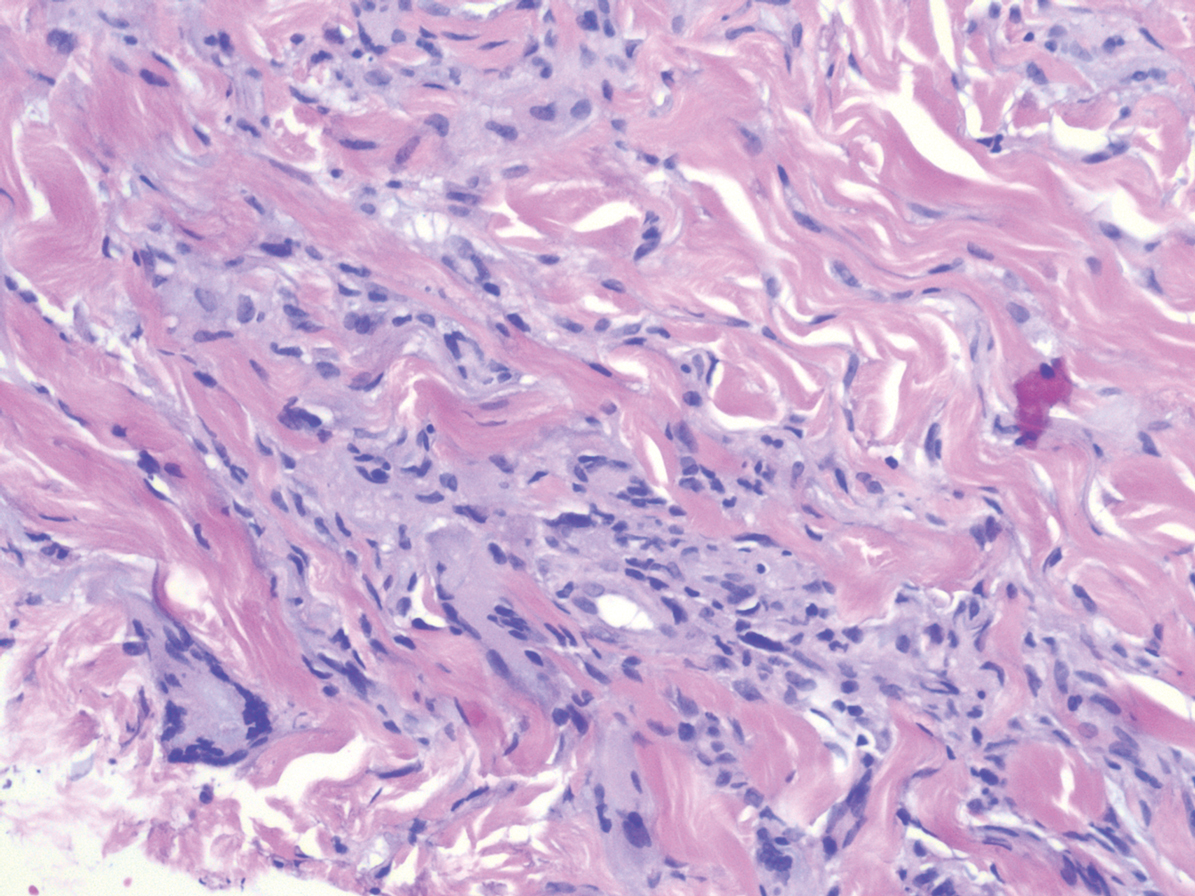

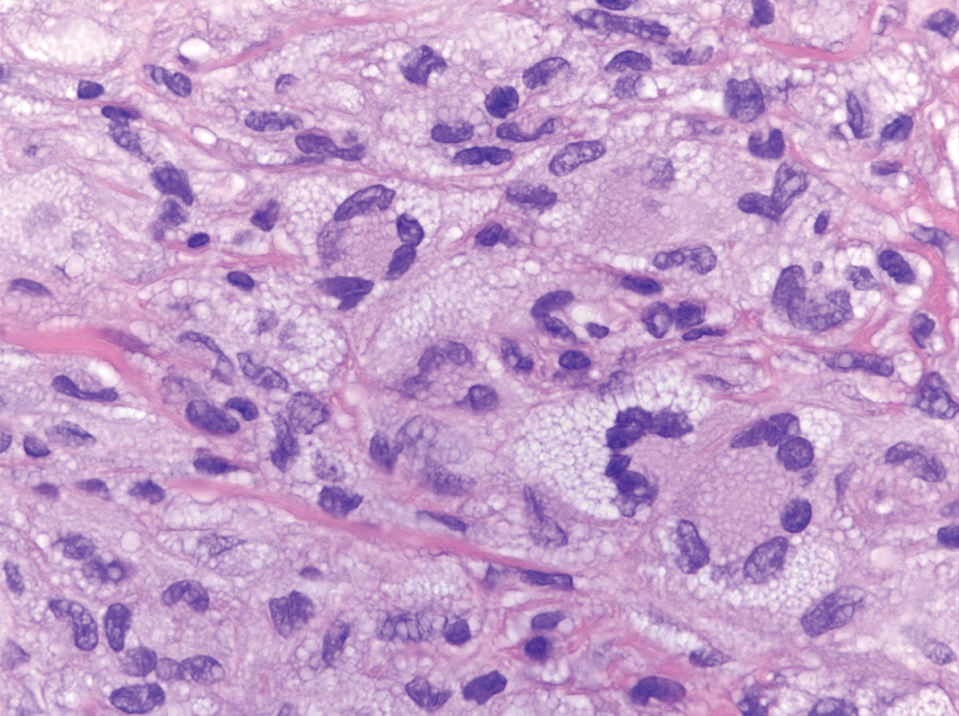

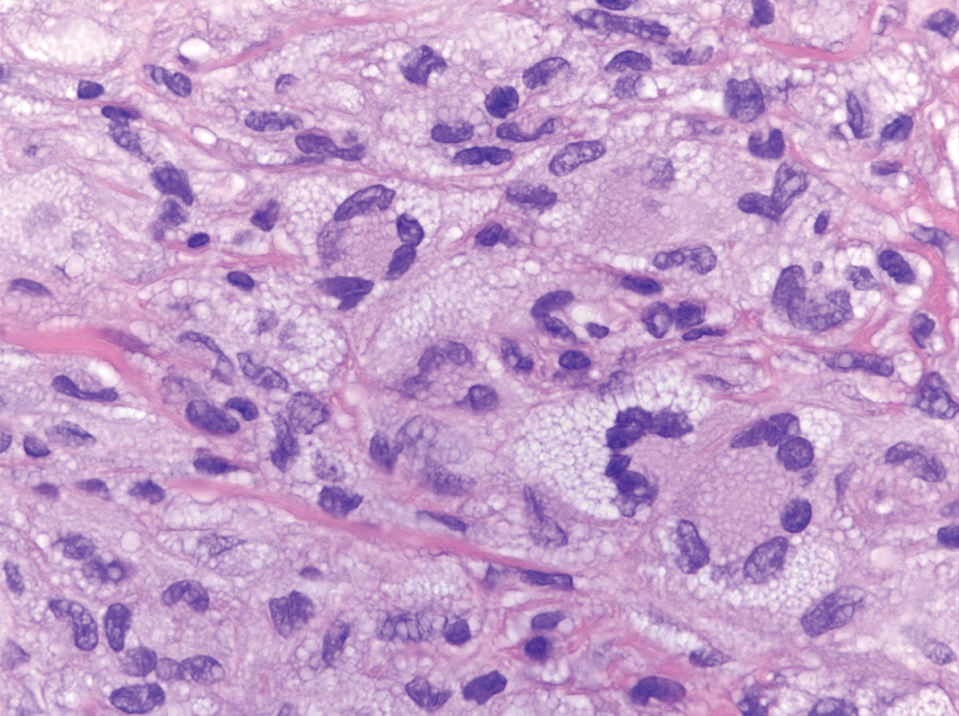

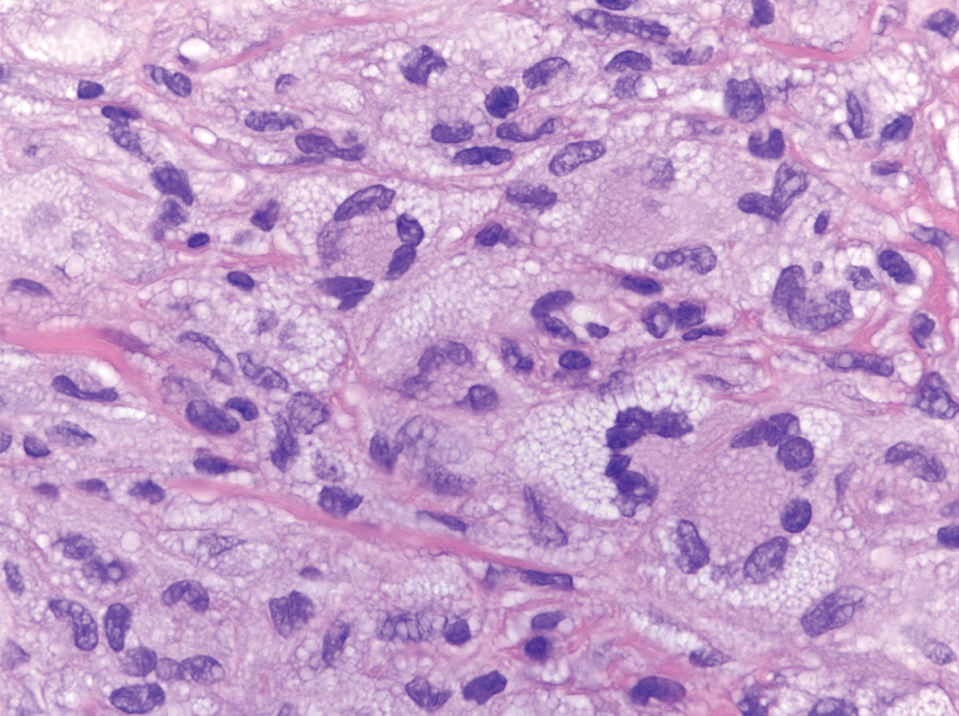

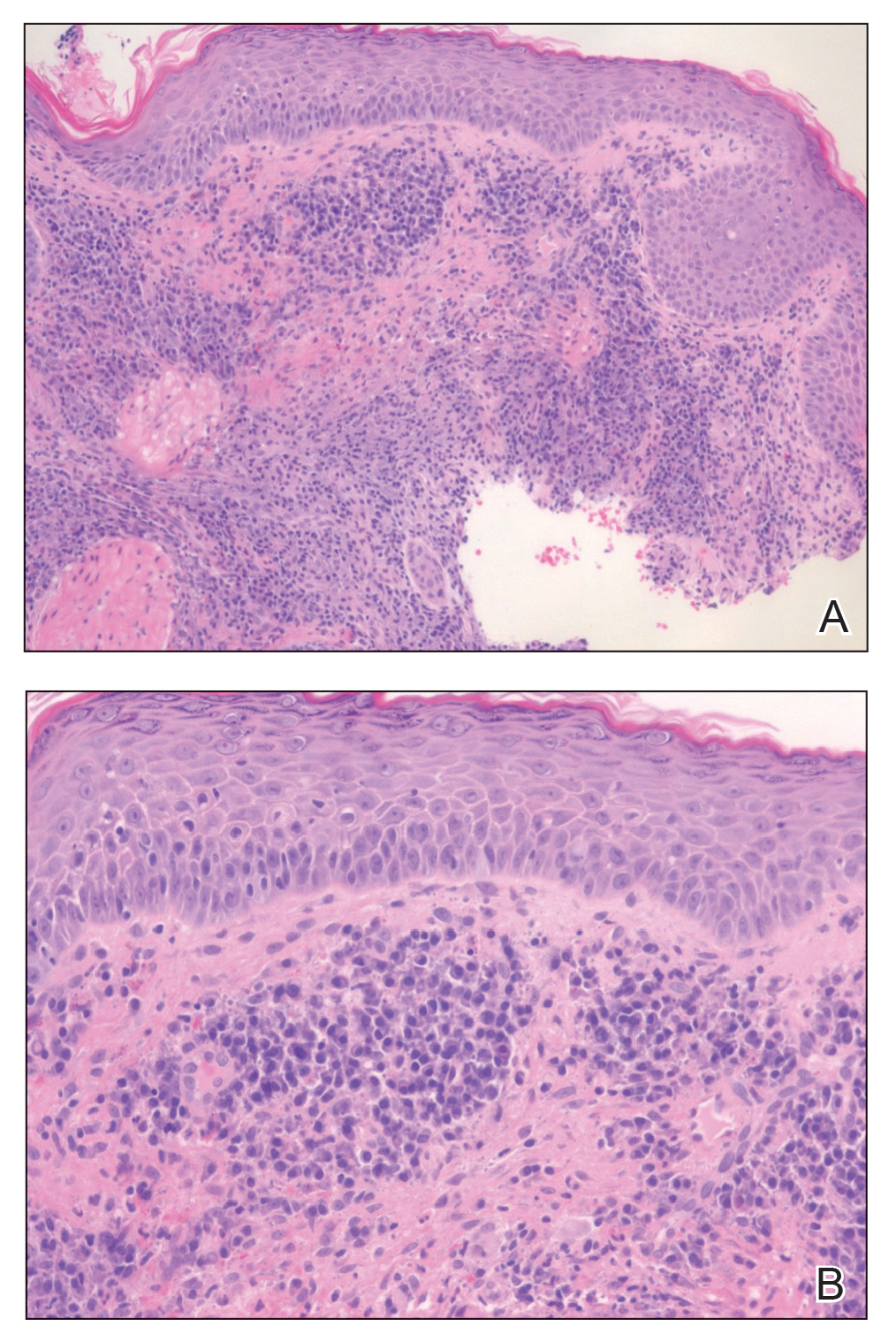

Solitary and multicentric reticulohistiocytoma is another form of resident dendritic cell histiocytopathy that can resemble Rosai-Dorfman disease. It is a dermal histiocytic infiltrate accompanied by a polymorphous inflammatory cell infiltrate (Figure 4) and can show variable fibrosis.13 One of the hallmarks is the distinct amphophilic cytoplasms, possibly attributable to nuclear DNA released into the cytoplasm from effete nuclei.13 The solitary form is unassociated with systemic disease, whereas the multicentric variant can be a paraneoplastic syndrome in the setting of solid and hematologic malignancies.14 In addition, in the multicentric variant, similar lesions can affect any organ but there can be a proclivity to involve the hand and knee joints, leading to a crippling arthritis.15 We presented a case of CRDD, a benign resident dendritic cell histiocytopathy that can manifest as a cutaneous confined process in the skin where the clinical course is characteristically benign. It potentially can be confused with LCH, indeterminate cell histiocytosis, xanthogranuloma, and reticulohistiocytoma. For a solitary lesion, intralesional triamcinolone injection and excision are options. Multifocal cutaneous disease or CRDD with notable extracutaneous disease may require systemic treatment.16 In our patient, one intralesional triamcinolone injection was performed with notable resolution.

- Rosai J, Dorfman RF. Sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy: a newly recognized benign clinicopathological entity. Arch Pathol. 1969;87:63-70.

- Brenn T, Calonje E, Granter SR, et al. Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease is a distinct clinical entity. Am J Dermatopathol. 2002;24:385.

- Ahmed A, Crowson N, Magro CM. A comprehensive assessment of cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2019;40:166-173.

- Frater JL, Maddox JS, Obadiah JM, et al. Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease: comprehensive review of cases reported in the medical literature since 1990 and presentation of an illustrative case. J Cutan Med Surg. 2006;10:281-290.

- Friedberg JW, Fisher RI. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2008;22:941-952. Doi:10.1016/j.hoc.2008.07.002

- Allen CE, Merad M, McClain KL. Langerhans-cell histiocytosis. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:856-868.

- Board PPTE. Langerhans cell histiocytosis treatment (PDQ®). In: PDQ Cancer Information Summaries [Internet]. National Cancer Institute (US); 2009.

- Chu A, Eisinger M, Lee JS, et al. Immunoelectron microscopic identification of Langerhans cells using a new antigenic marker. J Invest Dermatol. 1982;78:177-180. doi:10.1111/1523-1747.ep12506352

- Berti E, Gianotti R, Alessi E. Unusual cutaneous histiocytosis expressing an intermediate immunophenotype between Langerhans’ cells and dermal macrophages. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:1250-1253. doi:10.1001/archderm.1988.01670080062020

- Cypel TKS, Zuker RM. Juvenile xanthogranuloma: case report and review of the literature. Can J Plast Surg. 2008;16:175-177.

- Rodriguez J, Ackerman AB. Xanthogranuloma in adults. Arch Dermatol. 1976;112:43-44.

- Collie JS, Harper CD, Fillman EP. Juvenile xanthogranuloma. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Tajirian AL, Malik MK, Robinson-Bostom L, et al. Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis. Clin Dermatol. 2006;24:486-492. doi:10.1016/j. clindermatol.2006.07.010

- Miettinen M, Fetsch JF. Reticulohistiocytoma (solitary epithelioid histiocytoma): a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 44 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:521.

- Gold RH, Metzger AL, Mirra JM, et al. Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis (lipoid dermato-arthritis). An erosive polyarthritis with distinctive clinical, roentgenographic and pathologic features. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1975;124:610-624. doi:10.2214/ajr.124.4.610

- Dalia S, Sagatys E, Sokol L, et al. Rosai-Dorfman disease: tumor biology, clinical features, pathology, and treatment. Cancer Control. 2014;21:322-327. doi:10.1177/107327481402100408

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman Disease

Rosai-Dorfman disease is a rare benign non- Langerhans cell histiocytopathy that can manifest initially with lymph node involvement—classically, massive painless cervical lymphadenopathy.1 Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease (CRDD) is a variant that can be associated with lymph node and internal involvement, but more than 80% of cases lack extracutaneous involvement.2,3 In cases with extracutaneous involvement, lymph node disease is most frequent.3 Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease unassociated with extracutaneous disease is a benign self-limiting histiocytopathy that manifests as painless red-brown, yellow, or fleshcolored nodules, plaques, or papules that may become tender or ulcerated.4

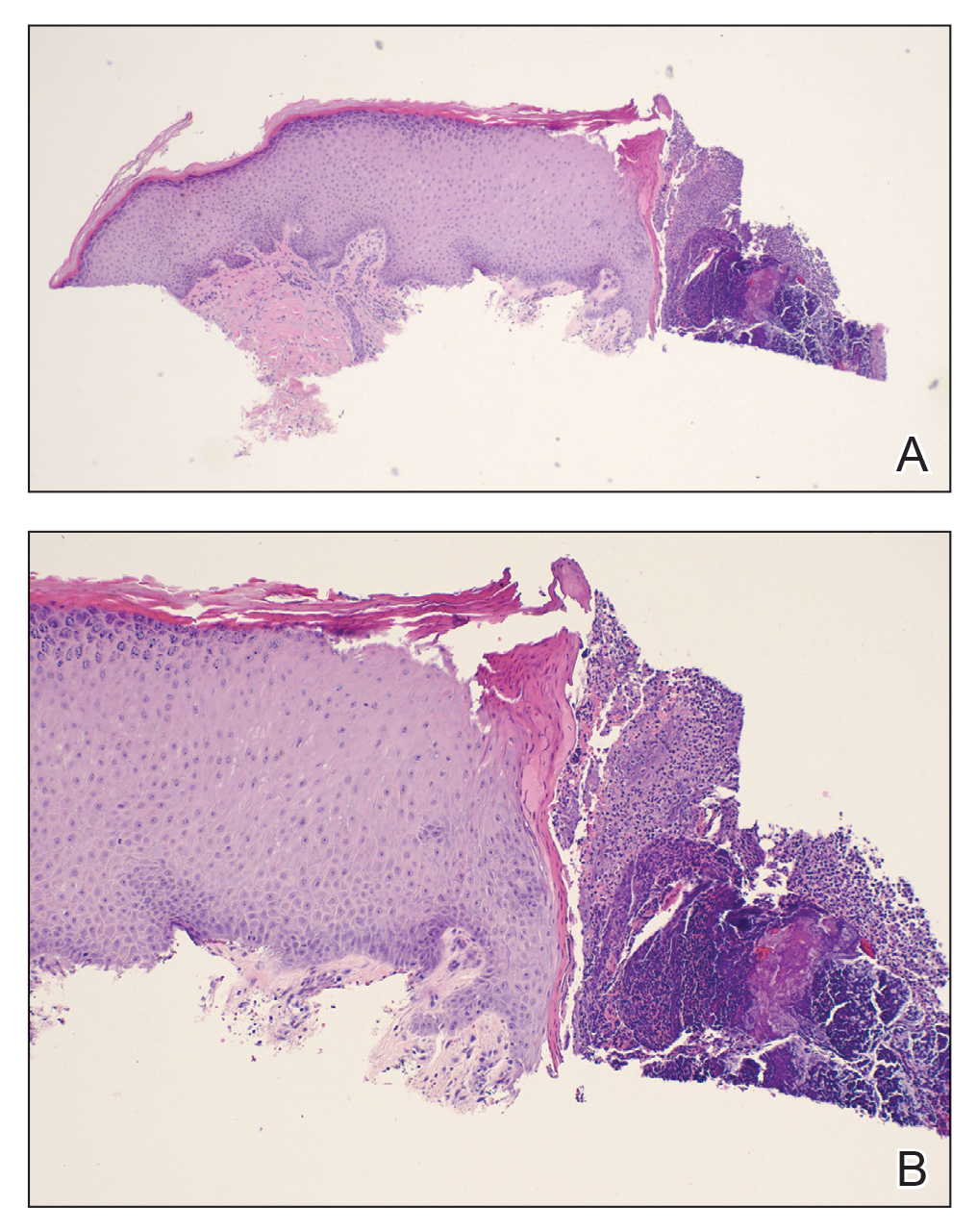

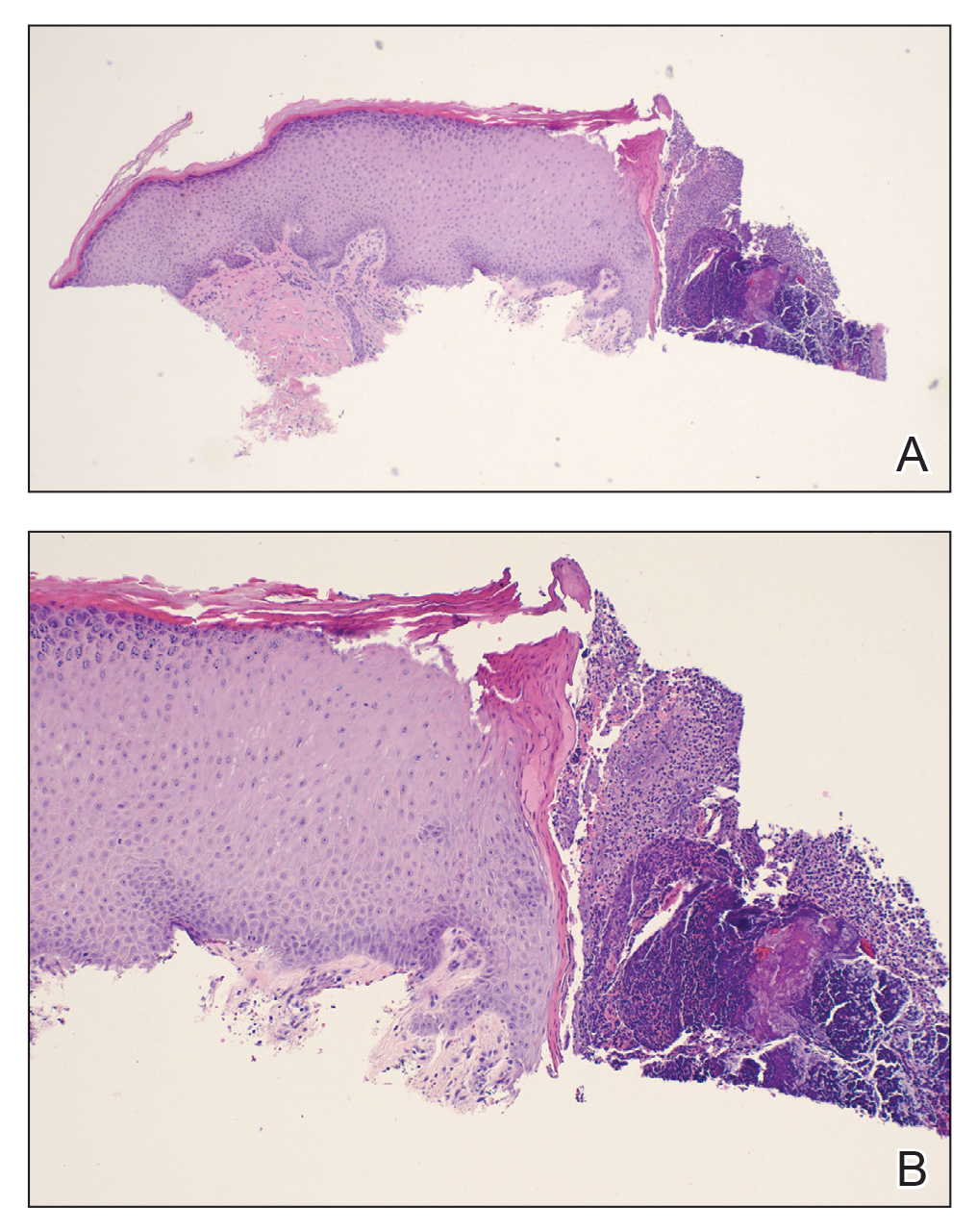

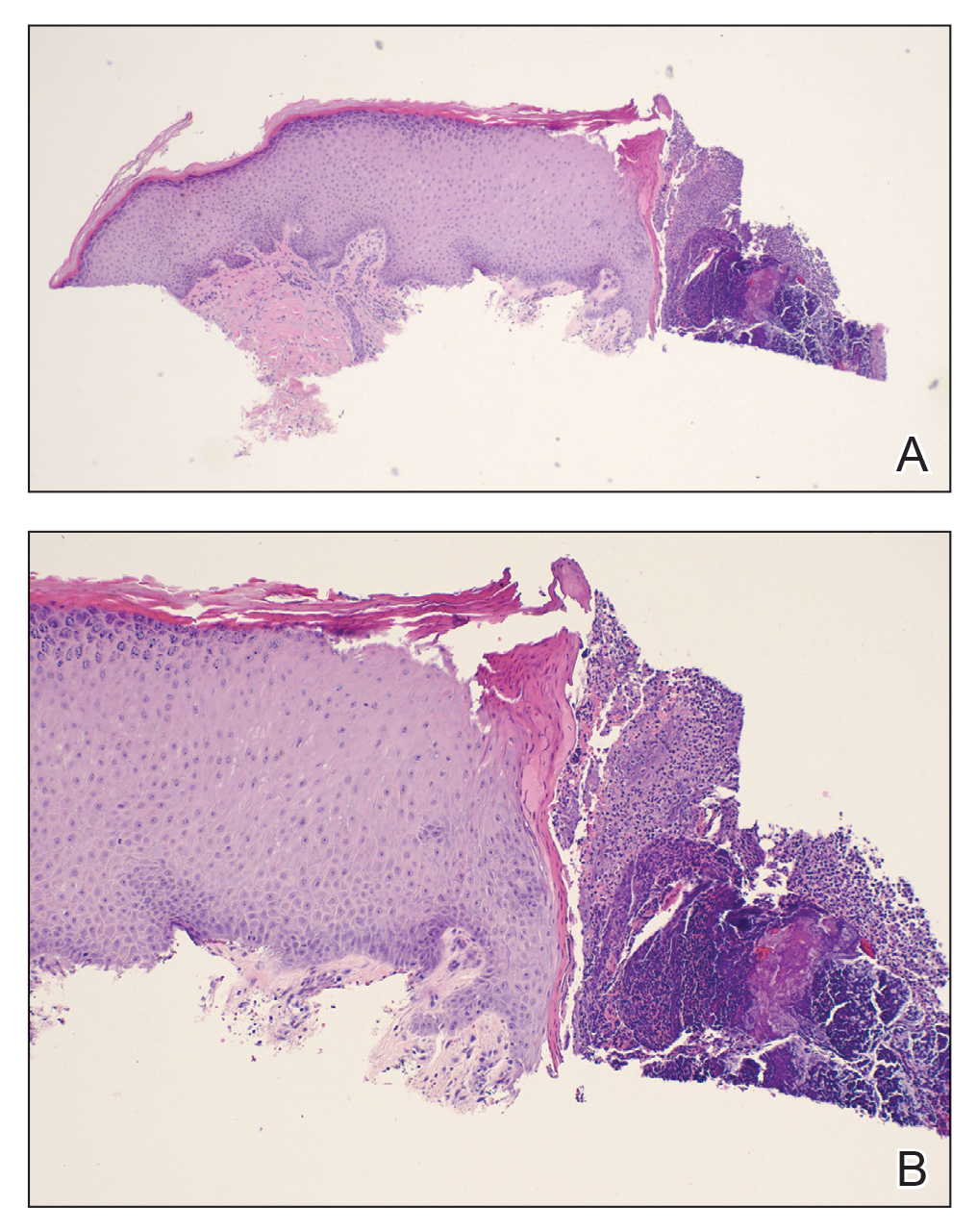

Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease represents a benign histiocytopathy of resident dendritic cell derivation.3 A characteristic immunohistochemical finding is S-100 positivity, which might suggest a Langerhans cell transdifferentiation phenotype, but other markers corroborative of a Langerhans cell phenotype—namely CD1a and langerin—will be negative. Biopsies typically show a mid to deep dermal histiocytic infiltration in a variably dense polymorphous inflammatory cell background comprised of a mixture of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and neutrophils.3 At times the extent of lymphocytic infiltration can be to a magnitude that resembles a lymphoma on histopathology. In our patient, lymphoma was excluded based on clinical presentation, as this patient lacked the typical symptoms of lymphadenopathy or B symptoms that come with B-cell lymphoma.5

The histiocytes in CRDD are characteristically large mononuclear cells exhibiting a low nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio reflective of the voluminous, nonvacuolated, watery cytoplasm. They have ill-defined cytoplasmic membranes resulting in a seemingly syncytial growth pattern. A hallmark of the histiocytes is emperipolesis characterized by intracytoplasmic localization of intact inflammatory cells including neutrophils, lymphocytes, and plasma cells.3

The differential diagnosis of CRDD includes Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH), indeterminate cell histiocytosis, xanthogranuloma, and reticulohistiocytoma. All of these conditions can be differentiated by their unique histopathologic and phenotypic characteristics.

Langerhans cell histiocytosis is a distinct clonal histiocytopathy that has a varied presentation ranging from cutaneous confined cases manifesting as a solitary lesion to one of disseminated cutaneous disease with the potential for multiorgan involvement. Regardless of the variant of LCH, the hallmark cell is one showing an eccentrically disposed, reniform nucleus with an open chromatin and abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm (Figure 1).6 Both LCH and CRDD stain positive for S-100. However, unlike the histiocytes in CRDD, those seen in LCH stain positive for CD1a and langerin and would not express factor XIIIA. Additionally, the neoplastic cells would not exhibit the same extent of CD68 positivity seen in CRDD.6 Treatment of LCH depends on the extent of disease, especially for the presence or absence of extracutaneous disease.7

A variant of LCH is indeterminate cell histiocytosis, which can be seen in neonates or adults. It represents a neoplastic proliferation of Langerhans cells that are devoid of Birbeck granules, reflective of an immature early phase of differentiation in the skin prior to the cells acquiring the Birbeck granule (as would be seen in neonates) or a later phase of differentiation after the mature Langerhans cell has encountered antigen and is en route to the lymph node (typically seen in adults).8 The phenotypic profile is identical to conventional LCH except the cells do not express langerin. Microscopically, the infiltrates are composed of Langerhans cells that are morphologically indistinguishable from classic LCH but without epidermotropism and exhibit a dominant localization in the dermis typically unassociated with other inflammatory cell elements (Figure 2).9

Xanthogranuloma is seen in young children (juvenile xanthogranuloma) as a solitary lesion, though a multifocal cutaneous variant and extracutaneous presentations have been described. Similar lesions can be seen in adults.10 These lesions are evolutionary in their morphology. In the inception of a juvenile xanthogranuloma, the lesions are highly cellular, and the histiocytes typically are poorly lipidized; there may be a dearth of other inflammatory cell elements. As the lesions mature, the histiocytes become lipidized, and characteristic Touton giant cells that exhibit a wreath of nuclei with peripheral lipidization may develop (Figure 3). In the later stages, there is considerable hyalinizing fibrosis, and the cells can acquire a spindled appearance. The absence of emperipolesis and the presence of notable lipidization are useful light microscopy features differentiating xanthogranuloma from CRDD.11 Treatment of xanthogranuloma can range from a conservative monitoring approach to an aggressive approach combining various antineoplastic therapies with immunosuppressive agents.12

Solitary and multicentric reticulohistiocytoma is another form of resident dendritic cell histiocytopathy that can resemble Rosai-Dorfman disease. It is a dermal histiocytic infiltrate accompanied by a polymorphous inflammatory cell infiltrate (Figure 4) and can show variable fibrosis.13 One of the hallmarks is the distinct amphophilic cytoplasms, possibly attributable to nuclear DNA released into the cytoplasm from effete nuclei.13 The solitary form is unassociated with systemic disease, whereas the multicentric variant can be a paraneoplastic syndrome in the setting of solid and hematologic malignancies.14 In addition, in the multicentric variant, similar lesions can affect any organ but there can be a proclivity to involve the hand and knee joints, leading to a crippling arthritis.15 We presented a case of CRDD, a benign resident dendritic cell histiocytopathy that can manifest as a cutaneous confined process in the skin where the clinical course is characteristically benign. It potentially can be confused with LCH, indeterminate cell histiocytosis, xanthogranuloma, and reticulohistiocytoma. For a solitary lesion, intralesional triamcinolone injection and excision are options. Multifocal cutaneous disease or CRDD with notable extracutaneous disease may require systemic treatment.16 In our patient, one intralesional triamcinolone injection was performed with notable resolution.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman Disease

Rosai-Dorfman disease is a rare benign non- Langerhans cell histiocytopathy that can manifest initially with lymph node involvement—classically, massive painless cervical lymphadenopathy.1 Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease (CRDD) is a variant that can be associated with lymph node and internal involvement, but more than 80% of cases lack extracutaneous involvement.2,3 In cases with extracutaneous involvement, lymph node disease is most frequent.3 Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease unassociated with extracutaneous disease is a benign self-limiting histiocytopathy that manifests as painless red-brown, yellow, or fleshcolored nodules, plaques, or papules that may become tender or ulcerated.4

Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease represents a benign histiocytopathy of resident dendritic cell derivation.3 A characteristic immunohistochemical finding is S-100 positivity, which might suggest a Langerhans cell transdifferentiation phenotype, but other markers corroborative of a Langerhans cell phenotype—namely CD1a and langerin—will be negative. Biopsies typically show a mid to deep dermal histiocytic infiltration in a variably dense polymorphous inflammatory cell background comprised of a mixture of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and neutrophils.3 At times the extent of lymphocytic infiltration can be to a magnitude that resembles a lymphoma on histopathology. In our patient, lymphoma was excluded based on clinical presentation, as this patient lacked the typical symptoms of lymphadenopathy or B symptoms that come with B-cell lymphoma.5

The histiocytes in CRDD are characteristically large mononuclear cells exhibiting a low nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio reflective of the voluminous, nonvacuolated, watery cytoplasm. They have ill-defined cytoplasmic membranes resulting in a seemingly syncytial growth pattern. A hallmark of the histiocytes is emperipolesis characterized by intracytoplasmic localization of intact inflammatory cells including neutrophils, lymphocytes, and plasma cells.3

The differential diagnosis of CRDD includes Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH), indeterminate cell histiocytosis, xanthogranuloma, and reticulohistiocytoma. All of these conditions can be differentiated by their unique histopathologic and phenotypic characteristics.

Langerhans cell histiocytosis is a distinct clonal histiocytopathy that has a varied presentation ranging from cutaneous confined cases manifesting as a solitary lesion to one of disseminated cutaneous disease with the potential for multiorgan involvement. Regardless of the variant of LCH, the hallmark cell is one showing an eccentrically disposed, reniform nucleus with an open chromatin and abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm (Figure 1).6 Both LCH and CRDD stain positive for S-100. However, unlike the histiocytes in CRDD, those seen in LCH stain positive for CD1a and langerin and would not express factor XIIIA. Additionally, the neoplastic cells would not exhibit the same extent of CD68 positivity seen in CRDD.6 Treatment of LCH depends on the extent of disease, especially for the presence or absence of extracutaneous disease.7

A variant of LCH is indeterminate cell histiocytosis, which can be seen in neonates or adults. It represents a neoplastic proliferation of Langerhans cells that are devoid of Birbeck granules, reflective of an immature early phase of differentiation in the skin prior to the cells acquiring the Birbeck granule (as would be seen in neonates) or a later phase of differentiation after the mature Langerhans cell has encountered antigen and is en route to the lymph node (typically seen in adults).8 The phenotypic profile is identical to conventional LCH except the cells do not express langerin. Microscopically, the infiltrates are composed of Langerhans cells that are morphologically indistinguishable from classic LCH but without epidermotropism and exhibit a dominant localization in the dermis typically unassociated with other inflammatory cell elements (Figure 2).9

Xanthogranuloma is seen in young children (juvenile xanthogranuloma) as a solitary lesion, though a multifocal cutaneous variant and extracutaneous presentations have been described. Similar lesions can be seen in adults.10 These lesions are evolutionary in their morphology. In the inception of a juvenile xanthogranuloma, the lesions are highly cellular, and the histiocytes typically are poorly lipidized; there may be a dearth of other inflammatory cell elements. As the lesions mature, the histiocytes become lipidized, and characteristic Touton giant cells that exhibit a wreath of nuclei with peripheral lipidization may develop (Figure 3). In the later stages, there is considerable hyalinizing fibrosis, and the cells can acquire a spindled appearance. The absence of emperipolesis and the presence of notable lipidization are useful light microscopy features differentiating xanthogranuloma from CRDD.11 Treatment of xanthogranuloma can range from a conservative monitoring approach to an aggressive approach combining various antineoplastic therapies with immunosuppressive agents.12

Solitary and multicentric reticulohistiocytoma is another form of resident dendritic cell histiocytopathy that can resemble Rosai-Dorfman disease. It is a dermal histiocytic infiltrate accompanied by a polymorphous inflammatory cell infiltrate (Figure 4) and can show variable fibrosis.13 One of the hallmarks is the distinct amphophilic cytoplasms, possibly attributable to nuclear DNA released into the cytoplasm from effete nuclei.13 The solitary form is unassociated with systemic disease, whereas the multicentric variant can be a paraneoplastic syndrome in the setting of solid and hematologic malignancies.14 In addition, in the multicentric variant, similar lesions can affect any organ but there can be a proclivity to involve the hand and knee joints, leading to a crippling arthritis.15 We presented a case of CRDD, a benign resident dendritic cell histiocytopathy that can manifest as a cutaneous confined process in the skin where the clinical course is characteristically benign. It potentially can be confused with LCH, indeterminate cell histiocytosis, xanthogranuloma, and reticulohistiocytoma. For a solitary lesion, intralesional triamcinolone injection and excision are options. Multifocal cutaneous disease or CRDD with notable extracutaneous disease may require systemic treatment.16 In our patient, one intralesional triamcinolone injection was performed with notable resolution.

- Rosai J, Dorfman RF. Sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy: a newly recognized benign clinicopathological entity. Arch Pathol. 1969;87:63-70.

- Brenn T, Calonje E, Granter SR, et al. Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease is a distinct clinical entity. Am J Dermatopathol. 2002;24:385.

- Ahmed A, Crowson N, Magro CM. A comprehensive assessment of cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2019;40:166-173.

- Frater JL, Maddox JS, Obadiah JM, et al. Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease: comprehensive review of cases reported in the medical literature since 1990 and presentation of an illustrative case. J Cutan Med Surg. 2006;10:281-290.

- Friedberg JW, Fisher RI. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2008;22:941-952. Doi:10.1016/j.hoc.2008.07.002

- Allen CE, Merad M, McClain KL. Langerhans-cell histiocytosis. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:856-868.

- Board PPTE. Langerhans cell histiocytosis treatment (PDQ®). In: PDQ Cancer Information Summaries [Internet]. National Cancer Institute (US); 2009.

- Chu A, Eisinger M, Lee JS, et al. Immunoelectron microscopic identification of Langerhans cells using a new antigenic marker. J Invest Dermatol. 1982;78:177-180. doi:10.1111/1523-1747.ep12506352

- Berti E, Gianotti R, Alessi E. Unusual cutaneous histiocytosis expressing an intermediate immunophenotype between Langerhans’ cells and dermal macrophages. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:1250-1253. doi:10.1001/archderm.1988.01670080062020

- Cypel TKS, Zuker RM. Juvenile xanthogranuloma: case report and review of the literature. Can J Plast Surg. 2008;16:175-177.

- Rodriguez J, Ackerman AB. Xanthogranuloma in adults. Arch Dermatol. 1976;112:43-44.

- Collie JS, Harper CD, Fillman EP. Juvenile xanthogranuloma. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Tajirian AL, Malik MK, Robinson-Bostom L, et al. Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis. Clin Dermatol. 2006;24:486-492. doi:10.1016/j. clindermatol.2006.07.010

- Miettinen M, Fetsch JF. Reticulohistiocytoma (solitary epithelioid histiocytoma): a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 44 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:521.

- Gold RH, Metzger AL, Mirra JM, et al. Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis (lipoid dermato-arthritis). An erosive polyarthritis with distinctive clinical, roentgenographic and pathologic features. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1975;124:610-624. doi:10.2214/ajr.124.4.610

- Dalia S, Sagatys E, Sokol L, et al. Rosai-Dorfman disease: tumor biology, clinical features, pathology, and treatment. Cancer Control. 2014;21:322-327. doi:10.1177/107327481402100408

- Rosai J, Dorfman RF. Sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy: a newly recognized benign clinicopathological entity. Arch Pathol. 1969;87:63-70.

- Brenn T, Calonje E, Granter SR, et al. Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease is a distinct clinical entity. Am J Dermatopathol. 2002;24:385.

- Ahmed A, Crowson N, Magro CM. A comprehensive assessment of cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2019;40:166-173.

- Frater JL, Maddox JS, Obadiah JM, et al. Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease: comprehensive review of cases reported in the medical literature since 1990 and presentation of an illustrative case. J Cutan Med Surg. 2006;10:281-290.

- Friedberg JW, Fisher RI. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2008;22:941-952. Doi:10.1016/j.hoc.2008.07.002

- Allen CE, Merad M, McClain KL. Langerhans-cell histiocytosis. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:856-868.

- Board PPTE. Langerhans cell histiocytosis treatment (PDQ®). In: PDQ Cancer Information Summaries [Internet]. National Cancer Institute (US); 2009.

- Chu A, Eisinger M, Lee JS, et al. Immunoelectron microscopic identification of Langerhans cells using a new antigenic marker. J Invest Dermatol. 1982;78:177-180. doi:10.1111/1523-1747.ep12506352

- Berti E, Gianotti R, Alessi E. Unusual cutaneous histiocytosis expressing an intermediate immunophenotype between Langerhans’ cells and dermal macrophages. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:1250-1253. doi:10.1001/archderm.1988.01670080062020

- Cypel TKS, Zuker RM. Juvenile xanthogranuloma: case report and review of the literature. Can J Plast Surg. 2008;16:175-177.

- Rodriguez J, Ackerman AB. Xanthogranuloma in adults. Arch Dermatol. 1976;112:43-44.

- Collie JS, Harper CD, Fillman EP. Juvenile xanthogranuloma. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Tajirian AL, Malik MK, Robinson-Bostom L, et al. Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis. Clin Dermatol. 2006;24:486-492. doi:10.1016/j. clindermatol.2006.07.010

- Miettinen M, Fetsch JF. Reticulohistiocytoma (solitary epithelioid histiocytoma): a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 44 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:521.

- Gold RH, Metzger AL, Mirra JM, et al. Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis (lipoid dermato-arthritis). An erosive polyarthritis with distinctive clinical, roentgenographic and pathologic features. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1975;124:610-624. doi:10.2214/ajr.124.4.610

- Dalia S, Sagatys E, Sokol L, et al. Rosai-Dorfman disease: tumor biology, clinical features, pathology, and treatment. Cancer Control. 2014;21:322-327. doi:10.1177/107327481402100408

A 31-year-old woman presented with a slow-growing, tender, pruritic lesion on the right cheek of 4 to 5 months’ duration. She had been applying petroleum jelly and hydrocortisone cream 2.5% without any improvement. Physical examination revealed a 1×5-mm, pearly pink, erythematous, crusted papule with arborizing vessels surrounded by scattered pink papules with white dots within. No cervical lymphadenopathy was appreciated on physical examination, and the patient denied any other systemic symptoms. Shave and punch biopsies of the lesion were performed; stains for microorganisms were negative. The biopsy showed a dense reticular mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate comprised of a mixture of histiocytes (top), lymphocytes, neutrophils, and plasma cells that assumed a diffuse growth pattern within the dermis. The histiocytes exhibited abundant watery cytoplasms with ill-defined cytoplasmic membranes; intact leukocytes were found within the cytoplasms. The histiocytes demonstrated a unique phenotype characterized by S-100 (bottom) and CD68 positivity.

Nonhealing Ulcer in a Patient With Crohn Disease

The Diagnosis: Mycobacterium abscessus Infection

Upon further testing, cultures were positive for Mycobacterium abscessus. Our patient was referred to infectious disease for co-management, and his treatment plan consisted of intravenous amikacin 885 mg 3 times weekly, intravenous imipenem 1 g twice daily, azithromycin 500 mg/d, and omadacycline 150 mg/d for at least 3 months. Magnetic resonance imaging findings were consistent with a combination of cellulitis and osteomyelitis, and our patient was referred to plastic surgery for debridement. He subsequently was lost to follow-up.

Mycobacterium abscessus is classified as both a nontuberculous and rapidly growing mycobacterium. Mycobacterium abscessus recently has emerged as a pathogen of increasing public health concern, especially due to its high rate of antibiotic resistance.1-5 It is highly prevalent in the environment, and infection has been reported from a wide variety of environmental sources.6-8 Immunocompromised individuals, such as our patient, undergoing anti–tumor necrosis factor therapy are at increased risk for infection from all Mycobacterium species.9-11 Recognizing these infections quickly is a priority for patient care, as M abscessus can lead to disseminated infection and high mortality rates.1

Histopathology of M abscessus consists of granulomatous inflammation with mixed granulomas12; however, these findings are not always appreciable, and staining does not always reveal visible organisms. In our patient, histopathology revealed patchy plasmalymphocytic infiltrates of the dermis and subcutaneous tissue, which are signs of generalized inflammation (Figure). Therefore, cultures positive for M abscessus are the gold standard for diagnosis and established the diagnosis in this case.

The differential diagnoses for our patient’s ulceration included squamous cell carcinoma, pyoderma gangrenosum, aseptic abscess ulcer, and pyodermatitispyostomatitis vegetans. Immunosuppressive therapy is a risk factor for squamous cell carcinoma13,14; however, ulcerated squamous cell carcinoma typically presents with prominent everted edges with a necrotic tumor base.15 Biopsy reveals cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm, large nuclei, and variable keratin pearls.16 Pyoderma gangrenosum is an inflammatory skin condition associated with Crohn disease and often is a diagnosis of exclusion characterized by neutrophilic infiltrates on biopsy.17-19 Aseptic abscess ulcers are characterized by neutrophil-filled lesions that respond to corticosteroids but not antibiotics.20 Pyodermatitis-pyostomatitis vegetans is a rare skin manifestation of inflammatory bowel disease associated with a pustular eruption of the skin and/or mouth. Histopathology reveals pustules within or below the epidermis with many eosinophils or neutrophils. Granulomas do not occur as in M abscessus.21

Treatment of M abscessus infection requires the coadministration of several antibiotics across multiple classes to ensure complete disease resolution. High rates of antibiotic resistance are characterized by at least partial resistance to almost every antibiotic; clarithromycin has near-complete efficacy, but resistant strains have started to emerge. Amikacin and cefoxitin are other antibiotics that have reported a resistance rate of less than 50%, but they are only effective 90% and 70% of the time, respectively.1,22 The antibiotic omadacycline, which is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration to treat acute bacterial skin and soft-tissue infections, also may have utility in treating M abscessus infections.23,24 Finally, phage therapy may offer a potential mode of treatment for this bacterium and was used to treat pulmonary infection in a patient with cystic fibrosis.25 Despite these newer innovations, the current standard of care involves clarithromycin or azithromycin in combination with a parenteral antibiotic such as cefoxitin, amikacin, or imipenem for at least 4 months.1

- Griffith DE, Aksamit T, Brown-Elliott BA, et al. An official ATS/IDSA statement: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:367-416.

- Jeong SH, Kim SY, Huh HJ, et al. Mycobacteriological characteristics and treatment outcomes in extrapulmonary Mycobacterium abscessus complex infections. Int J Infect Dis. 2017;60:49-56.

- Strnad L, Winthrop KL. Treatment of Mycobacterium abscessus complex. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;39:362-376.

- Cardenas DD, Yasmin T, Ahmed S. A rare insidious case of skin and soft tissue infection due to Mycobacterium abscessus: a case report. Cureus. 2022;14:E25725.

- Gonzalez-Santiago TM, Drage LA. Nontuberculous mycobacteria: skin and soft tissue infections. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:563-577.

- Dickison P, Howard V, O’Kane G, et al. Mycobacterium abscessus infection following penetrations through wetsuits. Australas J Dermatol. 2019;60:57-59.

- Choi H, Kim YI, Na CH, et al. Mycobacterium abscessus skin infection associated with shaving activity in a 75-year-old man. Ann Geriatr Med Res. 2018;22:204.

- Costa-Silva M, Cesar A, Gomes NP, et al. Mycobacterium abscessus infection in a spa worker. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2018;27:159-161.

- Besada E. Rapid growing mycobacteria and TNF-α blockers: case report of a fatal lung infection with Mycobacterium abscessus. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2011;29:705-707.

- Mufti AH, Toye BW, Mckendry RR, et al. Mycobacterium abscessus infection after use of tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor therapy: case report and review of infectious complications associated with tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor use. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2005;53:233-238.

- Lee SK, Kim SY, Kim EY, et al. Mycobacterial infections in patients treated with tumor necrosis factor antagonists in South Korea. Lung. 2013;191:565-571.

- Rodríguez G, Ortegón M, Camargo D, et al. Iatrogenic Mycobacterium abscessus infection: histopathology of 71 patients. Br J Dermatol. 1997;137:214-218.

- Firnhaber JM. Diagnosis and treatment of basal cell and squamous cell carcinoma. Am Fam Physician. 2012;86:161-168.

- Walker HS, Hardwicke J. Non-melanoma skin cancer. Surgery (Oxford). 2022;40:39-45.

- Browse NL. The skin. In: Browse NL, ed. An Introduction to the Symptoms and Signs of Surgical Disease. 3rd ed. London Arnold Publications; 2001:66-69.

- Weedon D. Squamous cell carcinoma. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 3rd ed. Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2010;691-700.

- Powell F, Schroeter A, Su W, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum: a review of 86 patients. QJM Int J Med. 1985;55:173-186.

- Brunsting LA, Goeckerman WH, O’Leary PA. Pyoderma (ecthyma) gangrenosum: clinical and experimental observations in five cases occurring in adults. Arch Dermatol. 1982;118:743-768.

- Maverakis E, Ma C, Shinkai K, et al. Diagnostic criteria of ulcerative pyoderma gangrenosum: a Delphi consensus of international experts. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:461-466.

- André MFJ, Piette JC, Kémény JL, et al. Aseptic abscesses: a study of 30 patients with or without inflammatory bowel disease and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2007;86:145. doi:10.1097/md.0b013e18064f9f3

- Femiano F, Lanza A, Buonaiuto C, et al. Pyostomatitis vegetans: a review of the literature. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2009;14:E114-E117.

- Kasperbauer SH, De Groote MA. The treatment of rapidly growing mycobacterial infections. Clin Chest Med. 2015;36:67-78.

- Duah M, Beshay M. Omadacycline in first-line combination therapy for pulmonary Mycobacterium abscessus infection: a case series. Int J Infect Dis. 2022;122:953-956.

- Minhas R, Sharma S, Kundu S. Utilizing the promise of omadacycline in a resistant, non-tubercular mycobacterial pulmonary infection. Cureus. 2019;11:E5112.

- Dedrick RM, Guerrero-Bustamante CA, Garlena RA, et al. Engineered bacteriophages for treatment of a patient with a disseminated drug-resistant Mycobacterium abscessus. Nat Med. 2019;25:730-733.

The Diagnosis: Mycobacterium abscessus Infection

Upon further testing, cultures were positive for Mycobacterium abscessus. Our patient was referred to infectious disease for co-management, and his treatment plan consisted of intravenous amikacin 885 mg 3 times weekly, intravenous imipenem 1 g twice daily, azithromycin 500 mg/d, and omadacycline 150 mg/d for at least 3 months. Magnetic resonance imaging findings were consistent with a combination of cellulitis and osteomyelitis, and our patient was referred to plastic surgery for debridement. He subsequently was lost to follow-up.

Mycobacterium abscessus is classified as both a nontuberculous and rapidly growing mycobacterium. Mycobacterium abscessus recently has emerged as a pathogen of increasing public health concern, especially due to its high rate of antibiotic resistance.1-5 It is highly prevalent in the environment, and infection has been reported from a wide variety of environmental sources.6-8 Immunocompromised individuals, such as our patient, undergoing anti–tumor necrosis factor therapy are at increased risk for infection from all Mycobacterium species.9-11 Recognizing these infections quickly is a priority for patient care, as M abscessus can lead to disseminated infection and high mortality rates.1

Histopathology of M abscessus consists of granulomatous inflammation with mixed granulomas12; however, these findings are not always appreciable, and staining does not always reveal visible organisms. In our patient, histopathology revealed patchy plasmalymphocytic infiltrates of the dermis and subcutaneous tissue, which are signs of generalized inflammation (Figure). Therefore, cultures positive for M abscessus are the gold standard for diagnosis and established the diagnosis in this case.

The differential diagnoses for our patient’s ulceration included squamous cell carcinoma, pyoderma gangrenosum, aseptic abscess ulcer, and pyodermatitispyostomatitis vegetans. Immunosuppressive therapy is a risk factor for squamous cell carcinoma13,14; however, ulcerated squamous cell carcinoma typically presents with prominent everted edges with a necrotic tumor base.15 Biopsy reveals cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm, large nuclei, and variable keratin pearls.16 Pyoderma gangrenosum is an inflammatory skin condition associated with Crohn disease and often is a diagnosis of exclusion characterized by neutrophilic infiltrates on biopsy.17-19 Aseptic abscess ulcers are characterized by neutrophil-filled lesions that respond to corticosteroids but not antibiotics.20 Pyodermatitis-pyostomatitis vegetans is a rare skin manifestation of inflammatory bowel disease associated with a pustular eruption of the skin and/or mouth. Histopathology reveals pustules within or below the epidermis with many eosinophils or neutrophils. Granulomas do not occur as in M abscessus.21

Treatment of M abscessus infection requires the coadministration of several antibiotics across multiple classes to ensure complete disease resolution. High rates of antibiotic resistance are characterized by at least partial resistance to almost every antibiotic; clarithromycin has near-complete efficacy, but resistant strains have started to emerge. Amikacin and cefoxitin are other antibiotics that have reported a resistance rate of less than 50%, but they are only effective 90% and 70% of the time, respectively.1,22 The antibiotic omadacycline, which is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration to treat acute bacterial skin and soft-tissue infections, also may have utility in treating M abscessus infections.23,24 Finally, phage therapy may offer a potential mode of treatment for this bacterium and was used to treat pulmonary infection in a patient with cystic fibrosis.25 Despite these newer innovations, the current standard of care involves clarithromycin or azithromycin in combination with a parenteral antibiotic such as cefoxitin, amikacin, or imipenem for at least 4 months.1

The Diagnosis: Mycobacterium abscessus Infection

Upon further testing, cultures were positive for Mycobacterium abscessus. Our patient was referred to infectious disease for co-management, and his treatment plan consisted of intravenous amikacin 885 mg 3 times weekly, intravenous imipenem 1 g twice daily, azithromycin 500 mg/d, and omadacycline 150 mg/d for at least 3 months. Magnetic resonance imaging findings were consistent with a combination of cellulitis and osteomyelitis, and our patient was referred to plastic surgery for debridement. He subsequently was lost to follow-up.

Mycobacterium abscessus is classified as both a nontuberculous and rapidly growing mycobacterium. Mycobacterium abscessus recently has emerged as a pathogen of increasing public health concern, especially due to its high rate of antibiotic resistance.1-5 It is highly prevalent in the environment, and infection has been reported from a wide variety of environmental sources.6-8 Immunocompromised individuals, such as our patient, undergoing anti–tumor necrosis factor therapy are at increased risk for infection from all Mycobacterium species.9-11 Recognizing these infections quickly is a priority for patient care, as M abscessus can lead to disseminated infection and high mortality rates.1

Histopathology of M abscessus consists of granulomatous inflammation with mixed granulomas12; however, these findings are not always appreciable, and staining does not always reveal visible organisms. In our patient, histopathology revealed patchy plasmalymphocytic infiltrates of the dermis and subcutaneous tissue, which are signs of generalized inflammation (Figure). Therefore, cultures positive for M abscessus are the gold standard for diagnosis and established the diagnosis in this case.

The differential diagnoses for our patient’s ulceration included squamous cell carcinoma, pyoderma gangrenosum, aseptic abscess ulcer, and pyodermatitispyostomatitis vegetans. Immunosuppressive therapy is a risk factor for squamous cell carcinoma13,14; however, ulcerated squamous cell carcinoma typically presents with prominent everted edges with a necrotic tumor base.15 Biopsy reveals cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm, large nuclei, and variable keratin pearls.16 Pyoderma gangrenosum is an inflammatory skin condition associated with Crohn disease and often is a diagnosis of exclusion characterized by neutrophilic infiltrates on biopsy.17-19 Aseptic abscess ulcers are characterized by neutrophil-filled lesions that respond to corticosteroids but not antibiotics.20 Pyodermatitis-pyostomatitis vegetans is a rare skin manifestation of inflammatory bowel disease associated with a pustular eruption of the skin and/or mouth. Histopathology reveals pustules within or below the epidermis with many eosinophils or neutrophils. Granulomas do not occur as in M abscessus.21

Treatment of M abscessus infection requires the coadministration of several antibiotics across multiple classes to ensure complete disease resolution. High rates of antibiotic resistance are characterized by at least partial resistance to almost every antibiotic; clarithromycin has near-complete efficacy, but resistant strains have started to emerge. Amikacin and cefoxitin are other antibiotics that have reported a resistance rate of less than 50%, but they are only effective 90% and 70% of the time, respectively.1,22 The antibiotic omadacycline, which is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration to treat acute bacterial skin and soft-tissue infections, also may have utility in treating M abscessus infections.23,24 Finally, phage therapy may offer a potential mode of treatment for this bacterium and was used to treat pulmonary infection in a patient with cystic fibrosis.25 Despite these newer innovations, the current standard of care involves clarithromycin or azithromycin in combination with a parenteral antibiotic such as cefoxitin, amikacin, or imipenem for at least 4 months.1

- Griffith DE, Aksamit T, Brown-Elliott BA, et al. An official ATS/IDSA statement: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:367-416.

- Jeong SH, Kim SY, Huh HJ, et al. Mycobacteriological characteristics and treatment outcomes in extrapulmonary Mycobacterium abscessus complex infections. Int J Infect Dis. 2017;60:49-56.

- Strnad L, Winthrop KL. Treatment of Mycobacterium abscessus complex. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;39:362-376.

- Cardenas DD, Yasmin T, Ahmed S. A rare insidious case of skin and soft tissue infection due to Mycobacterium abscessus: a case report. Cureus. 2022;14:E25725.

- Gonzalez-Santiago TM, Drage LA. Nontuberculous mycobacteria: skin and soft tissue infections. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:563-577.

- Dickison P, Howard V, O’Kane G, et al. Mycobacterium abscessus infection following penetrations through wetsuits. Australas J Dermatol. 2019;60:57-59.

- Choi H, Kim YI, Na CH, et al. Mycobacterium abscessus skin infection associated with shaving activity in a 75-year-old man. Ann Geriatr Med Res. 2018;22:204.

- Costa-Silva M, Cesar A, Gomes NP, et al. Mycobacterium abscessus infection in a spa worker. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2018;27:159-161.

- Besada E. Rapid growing mycobacteria and TNF-α blockers: case report of a fatal lung infection with Mycobacterium abscessus. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2011;29:705-707.

- Mufti AH, Toye BW, Mckendry RR, et al. Mycobacterium abscessus infection after use of tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor therapy: case report and review of infectious complications associated with tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor use. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2005;53:233-238.

- Lee SK, Kim SY, Kim EY, et al. Mycobacterial infections in patients treated with tumor necrosis factor antagonists in South Korea. Lung. 2013;191:565-571.

- Rodríguez G, Ortegón M, Camargo D, et al. Iatrogenic Mycobacterium abscessus infection: histopathology of 71 patients. Br J Dermatol. 1997;137:214-218.

- Firnhaber JM. Diagnosis and treatment of basal cell and squamous cell carcinoma. Am Fam Physician. 2012;86:161-168.

- Walker HS, Hardwicke J. Non-melanoma skin cancer. Surgery (Oxford). 2022;40:39-45.

- Browse NL. The skin. In: Browse NL, ed. An Introduction to the Symptoms and Signs of Surgical Disease. 3rd ed. London Arnold Publications; 2001:66-69.

- Weedon D. Squamous cell carcinoma. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 3rd ed. Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2010;691-700.

- Powell F, Schroeter A, Su W, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum: a review of 86 patients. QJM Int J Med. 1985;55:173-186.

- Brunsting LA, Goeckerman WH, O’Leary PA. Pyoderma (ecthyma) gangrenosum: clinical and experimental observations in five cases occurring in adults. Arch Dermatol. 1982;118:743-768.

- Maverakis E, Ma C, Shinkai K, et al. Diagnostic criteria of ulcerative pyoderma gangrenosum: a Delphi consensus of international experts. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:461-466.

- André MFJ, Piette JC, Kémény JL, et al. Aseptic abscesses: a study of 30 patients with or without inflammatory bowel disease and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2007;86:145. doi:10.1097/md.0b013e18064f9f3

- Femiano F, Lanza A, Buonaiuto C, et al. Pyostomatitis vegetans: a review of the literature. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2009;14:E114-E117.

- Kasperbauer SH, De Groote MA. The treatment of rapidly growing mycobacterial infections. Clin Chest Med. 2015;36:67-78.

- Duah M, Beshay M. Omadacycline in first-line combination therapy for pulmonary Mycobacterium abscessus infection: a case series. Int J Infect Dis. 2022;122:953-956.

- Minhas R, Sharma S, Kundu S. Utilizing the promise of omadacycline in a resistant, non-tubercular mycobacterial pulmonary infection. Cureus. 2019;11:E5112.

- Dedrick RM, Guerrero-Bustamante CA, Garlena RA, et al. Engineered bacteriophages for treatment of a patient with a disseminated drug-resistant Mycobacterium abscessus. Nat Med. 2019;25:730-733.

- Griffith DE, Aksamit T, Brown-Elliott BA, et al. An official ATS/IDSA statement: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:367-416.

- Jeong SH, Kim SY, Huh HJ, et al. Mycobacteriological characteristics and treatment outcomes in extrapulmonary Mycobacterium abscessus complex infections. Int J Infect Dis. 2017;60:49-56.

- Strnad L, Winthrop KL. Treatment of Mycobacterium abscessus complex. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;39:362-376.

- Cardenas DD, Yasmin T, Ahmed S. A rare insidious case of skin and soft tissue infection due to Mycobacterium abscessus: a case report. Cureus. 2022;14:E25725.

- Gonzalez-Santiago TM, Drage LA. Nontuberculous mycobacteria: skin and soft tissue infections. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:563-577.

- Dickison P, Howard V, O’Kane G, et al. Mycobacterium abscessus infection following penetrations through wetsuits. Australas J Dermatol. 2019;60:57-59.

- Choi H, Kim YI, Na CH, et al. Mycobacterium abscessus skin infection associated with shaving activity in a 75-year-old man. Ann Geriatr Med Res. 2018;22:204.

- Costa-Silva M, Cesar A, Gomes NP, et al. Mycobacterium abscessus infection in a spa worker. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2018;27:159-161.

- Besada E. Rapid growing mycobacteria and TNF-α blockers: case report of a fatal lung infection with Mycobacterium abscessus. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2011;29:705-707.

- Mufti AH, Toye BW, Mckendry RR, et al. Mycobacterium abscessus infection after use of tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor therapy: case report and review of infectious complications associated with tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor use. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2005;53:233-238.

- Lee SK, Kim SY, Kim EY, et al. Mycobacterial infections in patients treated with tumor necrosis factor antagonists in South Korea. Lung. 2013;191:565-571.

- Rodríguez G, Ortegón M, Camargo D, et al. Iatrogenic Mycobacterium abscessus infection: histopathology of 71 patients. Br J Dermatol. 1997;137:214-218.

- Firnhaber JM. Diagnosis and treatment of basal cell and squamous cell carcinoma. Am Fam Physician. 2012;86:161-168.

- Walker HS, Hardwicke J. Non-melanoma skin cancer. Surgery (Oxford). 2022;40:39-45.

- Browse NL. The skin. In: Browse NL, ed. An Introduction to the Symptoms and Signs of Surgical Disease. 3rd ed. London Arnold Publications; 2001:66-69.

- Weedon D. Squamous cell carcinoma. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 3rd ed. Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2010;691-700.

- Powell F, Schroeter A, Su W, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum: a review of 86 patients. QJM Int J Med. 1985;55:173-186.

- Brunsting LA, Goeckerman WH, O’Leary PA. Pyoderma (ecthyma) gangrenosum: clinical and experimental observations in five cases occurring in adults. Arch Dermatol. 1982;118:743-768.

- Maverakis E, Ma C, Shinkai K, et al. Diagnostic criteria of ulcerative pyoderma gangrenosum: a Delphi consensus of international experts. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:461-466.

- André MFJ, Piette JC, Kémény JL, et al. Aseptic abscesses: a study of 30 patients with or without inflammatory bowel disease and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2007;86:145. doi:10.1097/md.0b013e18064f9f3

- Femiano F, Lanza A, Buonaiuto C, et al. Pyostomatitis vegetans: a review of the literature. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2009;14:E114-E117.

- Kasperbauer SH, De Groote MA. The treatment of rapidly growing mycobacterial infections. Clin Chest Med. 2015;36:67-78.

- Duah M, Beshay M. Omadacycline in first-line combination therapy for pulmonary Mycobacterium abscessus infection: a case series. Int J Infect Dis. 2022;122:953-956.

- Minhas R, Sharma S, Kundu S. Utilizing the promise of omadacycline in a resistant, non-tubercular mycobacterial pulmonary infection. Cureus. 2019;11:E5112.

- Dedrick RM, Guerrero-Bustamante CA, Garlena RA, et al. Engineered bacteriophages for treatment of a patient with a disseminated drug-resistant Mycobacterium abscessus. Nat Med. 2019;25:730-733.

A 24-year-old man presented to our dermatology clinic with a painful lesion on the right buccal cheek of 4 months’ duration that had not changed in size or appearance. He had a history of Crohn disease that was being treated with 6-mercaptopurine and infliximab. He underwent jaw surgery 7 years prior for correction of an underbite, followed by subsequent surgery to remove the hardware 1 year after the initial procedure. He experienced recurring skin abscesses following the initial jaw surgery roughly once a year that were treated with bedside incision and drainage procedures in the emergency department followed by trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole with complete resolution; however, treatment with mupirocin ointment 2%, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and azithromycin did not provide symptomatic relief or resolution for the current lesion. Physical examination revealed a 4-cm ulceration with actively draining serosanguineous discharge. Two punch biopsies were performed; 48-hour bacterial and fungal cultures, as well as Giemsa, acid-fast bacilli, and periodic acid–Schiff staining were negative.

Cross-sectional Analysis of Matched Dermatology Residency Applicants Without US Home Programs

To the Editor:

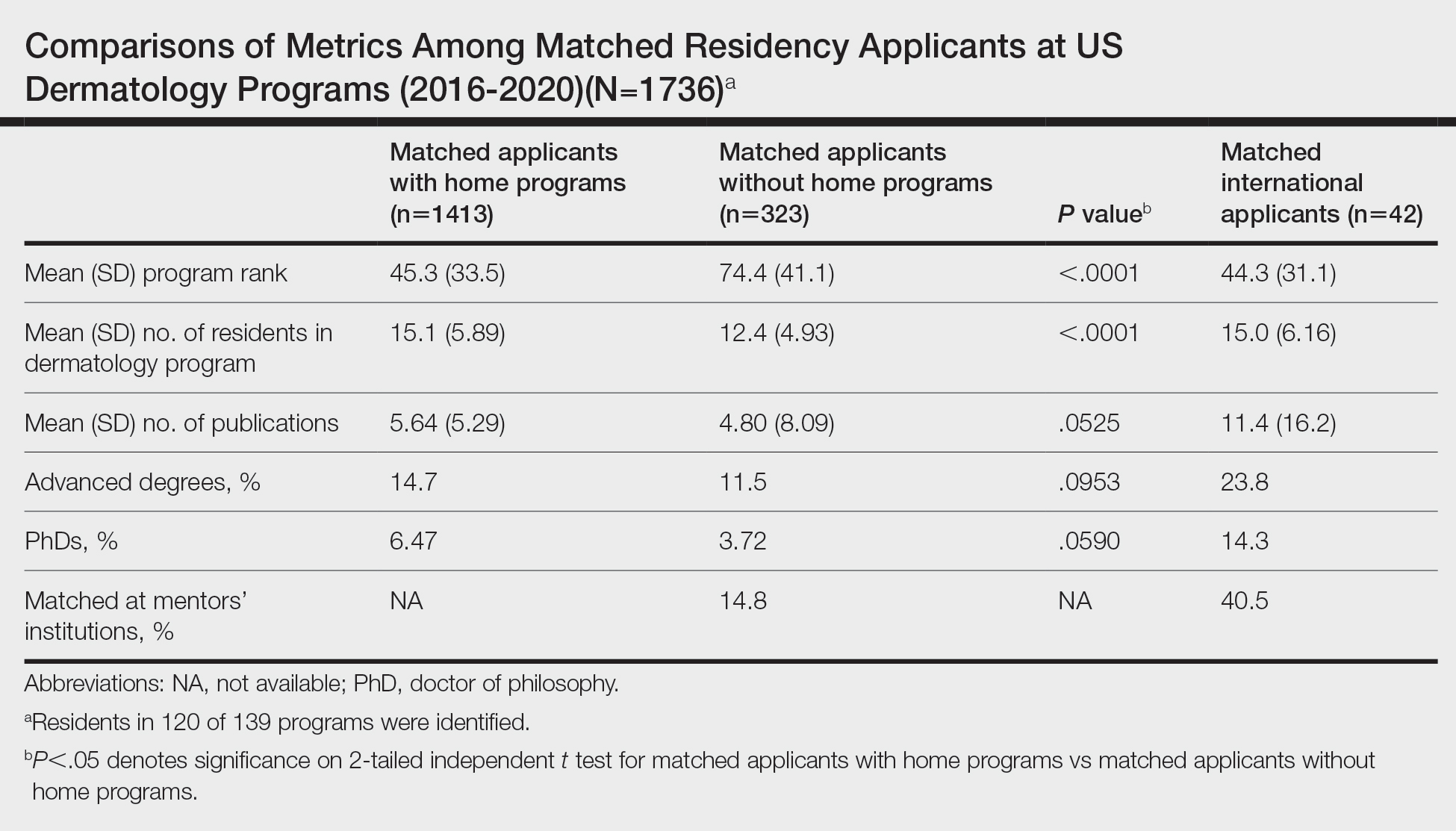

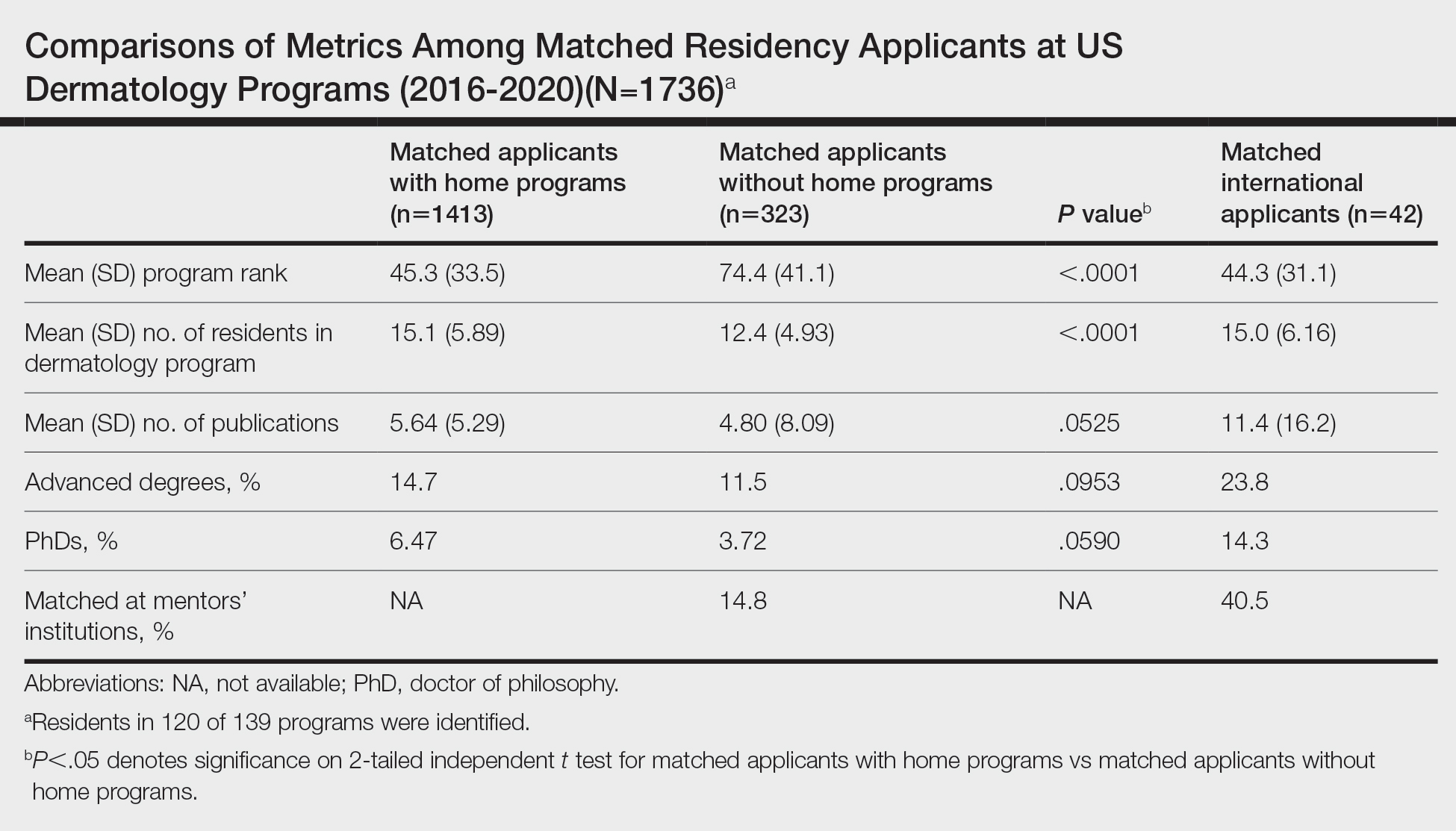

Dermatology is one of the most competitive residencies for matching, with a 57.5% match rate in 2022.1 Our prior study of research-mentor relationships among matched dermatology applicants corroborated the importance of home programs (HPs) and program connections.2 Therefore, our current objective was to compare profiles of matched dermatology applicants without HPs vs those with HPs.

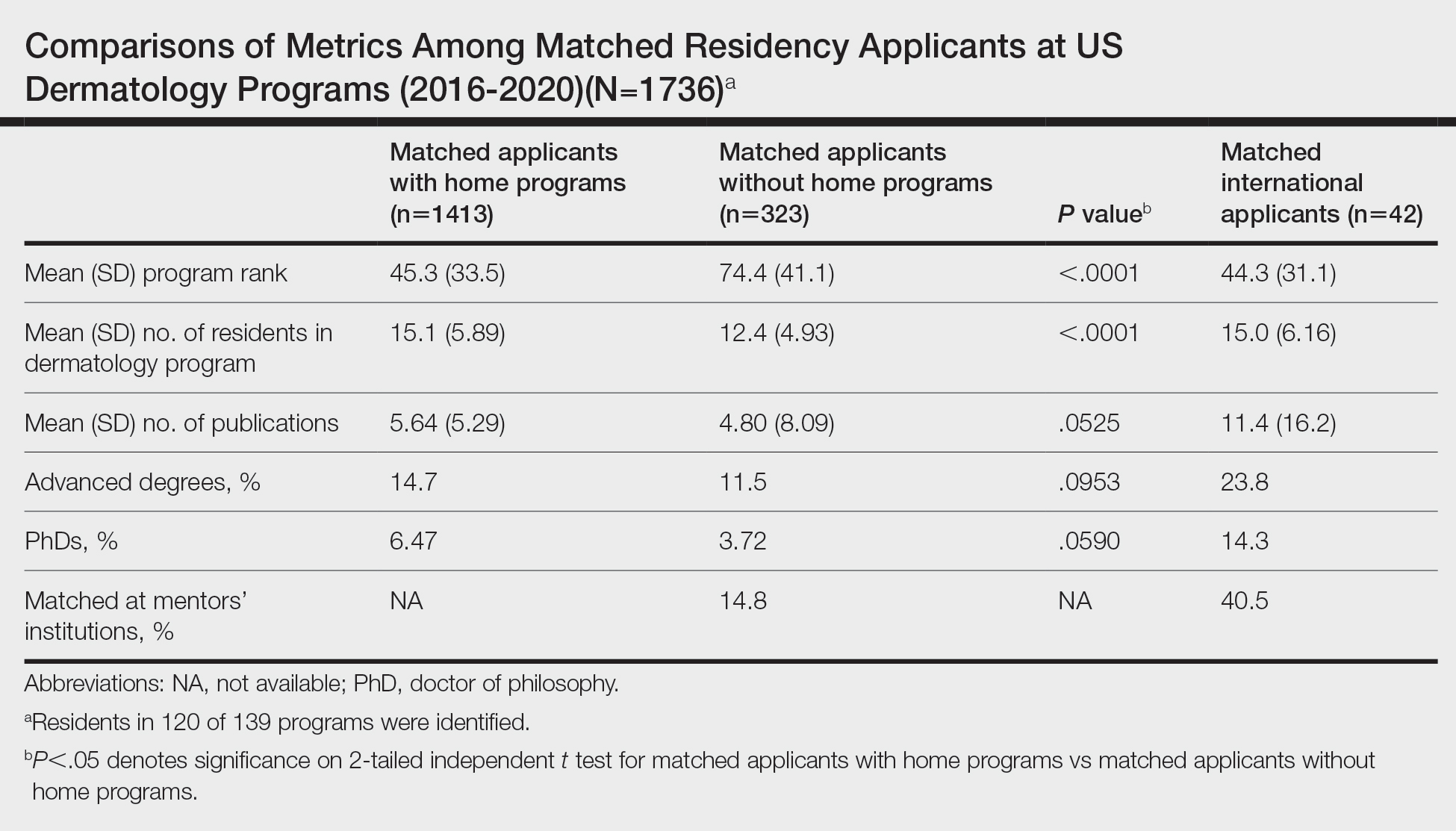

We searched websites of 139 dermatology programs nationwide and found 1736 matched applicants from 2016 to 2020; of them, 323 did not have HPs. We determined program rank by research output using Doximity Residency Navigator (https://www.doximity.com/residency/). Advanced degrees (ADs) of applicants were identified using program websites and LinkedIn. A PubMed search was conducted for number of articles published by each applicant before September 15 of their match year. For applicants without HPs, we identified the senior author on each publication. The senior author publishing with an applicant most often was considered the research mentor. Two-tailed independent t tests and χ2 tests were used to determine statistical significance (P<.05).

On average, matched applicants without HPs matched in lower-ranked (74.4) and smaller (12.4) programs compared with matched applicants with HPs (45.3 [P<.0001] and 15.1 [P<.0001], respectively)(eTable). The mean number of publications was similar between matched applicants with HPs and without HPs (5.64 and 4.80, respectively; P=.0525) as well as the percentage with ADs (14.7% and 11.5%, respectively; P=.0953). Overall, 14.8% of matched applicants without HPs matched at their mentors’ institutions.

Data were obtained for matched international applicants as a subset of non-HP applicants. Despite attending medical schools without associated HPs in the United States, international applicants matched at similarly ranked (44.3) and sized (15.0) programs, on average, compared with HP applicants. The mean number of publications was higher for international applicants (11.4) vs domestic applicants (5.33). International applicants more often had ADs (23.8%) and 60.1% of them held doctor of philosophy degrees. Overall, 40.5% of international applicants matched at their mentors’ institutions.

Our study suggests that matched dermatology applicants with and without HPs had similar achievements, on average, for the number of publications and percentage with ADs. However, non-HP applicants matched at lower-ranked programs than HP applicants. Therefore, applicants without HPs should strongly consider cultivating program connections, especially if they desire to match at higher-ranked dermatology programs. To illustrate, the rate of matching at research mentors’ institutions was approximately 3-times higher for international applicants than non-HP applicants overall. Despite the disadvantages of applying as international applicants, they were able to match at substantially higher-ranked dermatology programs than non-HP applicants. International applicants may have a longer time investment—the number of years from obtaining their medical degree or US medical license to matching—giving them time to produce quality research and develop meaningful relationships at an institution. Additionally, our prior study of the top 25 dermatology residencies showed that 26.2% of successful applicants matched at their research mentors’ institutions, with almost half of this subset matching at their HPs, where their mentors also practiced.2 Because of the potential benefits of having program connections, applicants without HPs should seek dermatology research mentors, especially via highly beneficial in-person networking opportunities (eg, away rotations, conferences) that had previously been limited during the COVID-19 pandemic.3 Formal mentorship programs giving priority to students without HPs recently have been developed, which only begins to address the inequities in the dermatology residency application process.4

Study limitations include lack of resident information on 15 program websites, missed publications due to applicant name changes, not accounting for abstracts and posters, and inability to collect data on unmatched applicants.

We hope that our study alleviates some concerns that applicants without HPs may have regarding applying for dermatology residency and encourages those with a genuine interest in dermatology to pursue the specialty, provided they find a strong research mentor. Residency programs should be cognizant of the unique challenges that non-HP applicants face for matching.

- National Resident Matching Program. Results and Data: 2022 Main Residency Match. National Resident Matching Program; May 2022. Accessed May 30, 2023. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11 /2022-Main-Match-Results-and-Data-Final-Revised.pdf

- Yeh C, Desai AD, Wilson BN, et al. Cross-sectional analysis of scholarly work and mentor relationships in matched dermatology residency applicants. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:1437-1439.

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Specialty recommendations on away rotations for 2021-22 academic year. Accessed May 24, 2023. https://students-residents.aamc.org/researching-residency-programs -and-building-application-strategy/specialty-response-covid-19

- derminterest Instagram page. DIGA is excited for the second year of our mentor-mentee program! Mentors are dermatology residents. Please keep in mind due to the current circumstances, dermatology residency 2021-2022 applicants without home programs will be prioritized as mentees. Please refrain from signing up if you were paired with a faculty mentor for the APD-DIGA Mentorship Program in May 2021. Contact @suryasweetie123 only if you have specific questions, otherwise all information is on our website and the link is here. Link is below and in our bio! #DIGA #derm #mentee #residencyapplication. Accessed May 24, 2023. https://www.instagram.com/p/CSrq0exMchY/

To the Editor:

Dermatology is one of the most competitive residencies for matching, with a 57.5% match rate in 2022.1 Our prior study of research-mentor relationships among matched dermatology applicants corroborated the importance of home programs (HPs) and program connections.2 Therefore, our current objective was to compare profiles of matched dermatology applicants without HPs vs those with HPs.

We searched websites of 139 dermatology programs nationwide and found 1736 matched applicants from 2016 to 2020; of them, 323 did not have HPs. We determined program rank by research output using Doximity Residency Navigator (https://www.doximity.com/residency/). Advanced degrees (ADs) of applicants were identified using program websites and LinkedIn. A PubMed search was conducted for number of articles published by each applicant before September 15 of their match year. For applicants without HPs, we identified the senior author on each publication. The senior author publishing with an applicant most often was considered the research mentor. Two-tailed independent t tests and χ2 tests were used to determine statistical significance (P<.05).

On average, matched applicants without HPs matched in lower-ranked (74.4) and smaller (12.4) programs compared with matched applicants with HPs (45.3 [P<.0001] and 15.1 [P<.0001], respectively)(eTable). The mean number of publications was similar between matched applicants with HPs and without HPs (5.64 and 4.80, respectively; P=.0525) as well as the percentage with ADs (14.7% and 11.5%, respectively; P=.0953). Overall, 14.8% of matched applicants without HPs matched at their mentors’ institutions.

Data were obtained for matched international applicants as a subset of non-HP applicants. Despite attending medical schools without associated HPs in the United States, international applicants matched at similarly ranked (44.3) and sized (15.0) programs, on average, compared with HP applicants. The mean number of publications was higher for international applicants (11.4) vs domestic applicants (5.33). International applicants more often had ADs (23.8%) and 60.1% of them held doctor of philosophy degrees. Overall, 40.5% of international applicants matched at their mentors’ institutions.

Our study suggests that matched dermatology applicants with and without HPs had similar achievements, on average, for the number of publications and percentage with ADs. However, non-HP applicants matched at lower-ranked programs than HP applicants. Therefore, applicants without HPs should strongly consider cultivating program connections, especially if they desire to match at higher-ranked dermatology programs. To illustrate, the rate of matching at research mentors’ institutions was approximately 3-times higher for international applicants than non-HP applicants overall. Despite the disadvantages of applying as international applicants, they were able to match at substantially higher-ranked dermatology programs than non-HP applicants. International applicants may have a longer time investment—the number of years from obtaining their medical degree or US medical license to matching—giving them time to produce quality research and develop meaningful relationships at an institution. Additionally, our prior study of the top 25 dermatology residencies showed that 26.2% of successful applicants matched at their research mentors’ institutions, with almost half of this subset matching at their HPs, where their mentors also practiced.2 Because of the potential benefits of having program connections, applicants without HPs should seek dermatology research mentors, especially via highly beneficial in-person networking opportunities (eg, away rotations, conferences) that had previously been limited during the COVID-19 pandemic.3 Formal mentorship programs giving priority to students without HPs recently have been developed, which only begins to address the inequities in the dermatology residency application process.4

Study limitations include lack of resident information on 15 program websites, missed publications due to applicant name changes, not accounting for abstracts and posters, and inability to collect data on unmatched applicants.

We hope that our study alleviates some concerns that applicants without HPs may have regarding applying for dermatology residency and encourages those with a genuine interest in dermatology to pursue the specialty, provided they find a strong research mentor. Residency programs should be cognizant of the unique challenges that non-HP applicants face for matching.

To the Editor:

Dermatology is one of the most competitive residencies for matching, with a 57.5% match rate in 2022.1 Our prior study of research-mentor relationships among matched dermatology applicants corroborated the importance of home programs (HPs) and program connections.2 Therefore, our current objective was to compare profiles of matched dermatology applicants without HPs vs those with HPs.

We searched websites of 139 dermatology programs nationwide and found 1736 matched applicants from 2016 to 2020; of them, 323 did not have HPs. We determined program rank by research output using Doximity Residency Navigator (https://www.doximity.com/residency/). Advanced degrees (ADs) of applicants were identified using program websites and LinkedIn. A PubMed search was conducted for number of articles published by each applicant before September 15 of their match year. For applicants without HPs, we identified the senior author on each publication. The senior author publishing with an applicant most often was considered the research mentor. Two-tailed independent t tests and χ2 tests were used to determine statistical significance (P<.05).

On average, matched applicants without HPs matched in lower-ranked (74.4) and smaller (12.4) programs compared with matched applicants with HPs (45.3 [P<.0001] and 15.1 [P<.0001], respectively)(eTable). The mean number of publications was similar between matched applicants with HPs and without HPs (5.64 and 4.80, respectively; P=.0525) as well as the percentage with ADs (14.7% and 11.5%, respectively; P=.0953). Overall, 14.8% of matched applicants without HPs matched at their mentors’ institutions.

Data were obtained for matched international applicants as a subset of non-HP applicants. Despite attending medical schools without associated HPs in the United States, international applicants matched at similarly ranked (44.3) and sized (15.0) programs, on average, compared with HP applicants. The mean number of publications was higher for international applicants (11.4) vs domestic applicants (5.33). International applicants more often had ADs (23.8%) and 60.1% of them held doctor of philosophy degrees. Overall, 40.5% of international applicants matched at their mentors’ institutions.

Our study suggests that matched dermatology applicants with and without HPs had similar achievements, on average, for the number of publications and percentage with ADs. However, non-HP applicants matched at lower-ranked programs than HP applicants. Therefore, applicants without HPs should strongly consider cultivating program connections, especially if they desire to match at higher-ranked dermatology programs. To illustrate, the rate of matching at research mentors’ institutions was approximately 3-times higher for international applicants than non-HP applicants overall. Despite the disadvantages of applying as international applicants, they were able to match at substantially higher-ranked dermatology programs than non-HP applicants. International applicants may have a longer time investment—the number of years from obtaining their medical degree or US medical license to matching—giving them time to produce quality research and develop meaningful relationships at an institution. Additionally, our prior study of the top 25 dermatology residencies showed that 26.2% of successful applicants matched at their research mentors’ institutions, with almost half of this subset matching at their HPs, where their mentors also practiced.2 Because of the potential benefits of having program connections, applicants without HPs should seek dermatology research mentors, especially via highly beneficial in-person networking opportunities (eg, away rotations, conferences) that had previously been limited during the COVID-19 pandemic.3 Formal mentorship programs giving priority to students without HPs recently have been developed, which only begins to address the inequities in the dermatology residency application process.4

Study limitations include lack of resident information on 15 program websites, missed publications due to applicant name changes, not accounting for abstracts and posters, and inability to collect data on unmatched applicants.

We hope that our study alleviates some concerns that applicants without HPs may have regarding applying for dermatology residency and encourages those with a genuine interest in dermatology to pursue the specialty, provided they find a strong research mentor. Residency programs should be cognizant of the unique challenges that non-HP applicants face for matching.

- National Resident Matching Program. Results and Data: 2022 Main Residency Match. National Resident Matching Program; May 2022. Accessed May 30, 2023. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11 /2022-Main-Match-Results-and-Data-Final-Revised.pdf

- Yeh C, Desai AD, Wilson BN, et al. Cross-sectional analysis of scholarly work and mentor relationships in matched dermatology residency applicants. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:1437-1439.

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Specialty recommendations on away rotations for 2021-22 academic year. Accessed May 24, 2023. https://students-residents.aamc.org/researching-residency-programs -and-building-application-strategy/specialty-response-covid-19

- derminterest Instagram page. DIGA is excited for the second year of our mentor-mentee program! Mentors are dermatology residents. Please keep in mind due to the current circumstances, dermatology residency 2021-2022 applicants without home programs will be prioritized as mentees. Please refrain from signing up if you were paired with a faculty mentor for the APD-DIGA Mentorship Program in May 2021. Contact @suryasweetie123 only if you have specific questions, otherwise all information is on our website and the link is here. Link is below and in our bio! #DIGA #derm #mentee #residencyapplication. Accessed May 24, 2023. https://www.instagram.com/p/CSrq0exMchY/

- National Resident Matching Program. Results and Data: 2022 Main Residency Match. National Resident Matching Program; May 2022. Accessed May 30, 2023. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11 /2022-Main-Match-Results-and-Data-Final-Revised.pdf

- Yeh C, Desai AD, Wilson BN, et al. Cross-sectional analysis of scholarly work and mentor relationships in matched dermatology residency applicants. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:1437-1439.

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Specialty recommendations on away rotations for 2021-22 academic year. Accessed May 24, 2023. https://students-residents.aamc.org/researching-residency-programs -and-building-application-strategy/specialty-response-covid-19

- derminterest Instagram page. DIGA is excited for the second year of our mentor-mentee program! Mentors are dermatology residents. Please keep in mind due to the current circumstances, dermatology residency 2021-2022 applicants without home programs will be prioritized as mentees. Please refrain from signing up if you were paired with a faculty mentor for the APD-DIGA Mentorship Program in May 2021. Contact @suryasweetie123 only if you have specific questions, otherwise all information is on our website and the link is here. Link is below and in our bio! #DIGA #derm #mentee #residencyapplication. Accessed May 24, 2023. https://www.instagram.com/p/CSrq0exMchY/

Practice Points

- Our study suggests that matched dermatology applicants with and without home programs (HPs) had similar achievements, on average, for number of publications and holding advanced degrees.

- Because of the potential benefits of having program connections for matching in dermatology, applicants without HPs should seek dermatology research mentors.

Teaching Evidence-Based Dermatology Using a Web-Based Journal Club: A Pilot Study and Survey

To the Editor:

With a steady increase in dermatology publications over recent decades, there is an expanding pool of evidence to address clinical questions.1 Residency training is the time when appraising the medical literature and practicing evidence-based medicine is most honed. Evidence-based medicine is an essential component of Practice-based Learning and Improvement, a required core competency of the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education.2 Assimilation of new research evidence is traditionally taught through didactics and journal club discussions in residency.

However, at a time when the demand for information overwhelms safeguards that exist to evaluate its quality, it is more important than ever to be equipped with the proper tools to critically appraise novel literature. Beyond accepting a scientific article at face value, physicians must learn to ask targeted questions of the study design, results, and clinical relevance. These questions change based on the type of study, and organizations such as the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine provide guidance through critical appraisal worksheets.3

To investigate the utility of using guided questions to evaluate the reliability, significance, and applicability of clinical evidence, we beta tested a novel web-based application in an academic dermatology setting to design and run a journal club for residents. Six dermatology residents participated in this institutional review board–approved study comprised of 3 phases: (1) independent article appraisal through the web-based application, (2) group discussion, and (3) anonymous postsurvey.

Using this platform, we uploaded a recent article into the interactive reader, which contained an integrated tool for appraisal based on specific questions. Because the article described the results of a randomized clinical trial, we used questions from the Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine’s Randomised Controlled Trials Critical Appraisal Worksheet, which has a series of questions to evaluate internal validity, results, and external validity and applicability.3

Residents used the platform to independently read the article, highlight areas of the text that corresponded to 8 critical appraisal questions, and answer yes or no to these questions. Based on residents’ answers, a final appraisal score (on a scale of 1% to 100%) was generated. Simultaneously, the attending dermatologist leading the journal club (C.W.) also completed the assignment to establish an expert score.

Scores from the residents’ independent appraisal ranged from 75% to 100% (mean, 85.4%). Upon discussing the article in a group setting, the residents established a consensus score of 75%. This consensus score matched the expert score, which suggested to us that both independently reviewing the article using guided questions and conducting a group debriefing were necessary to match the expert level of critical appraisal.

Of note, the residents’ average independent appraisal score was higher than both the consensus and expert scores, indicating that the residents evaluated the article less critically on their own. With more practice using this method, it is possible that the precision and accuracy of the residents’ critical appraisal of scientific articles will improve.

In the postsurvey, we asked residents about the critical appraisal of the medical literature. All residents agreed that evaluating the quality of evidence when reading a scientific article was somewhat important or very important to them; however, only 2 of 6 evaluated the quality of evidence all the time, and the other 4 did so half of the time or less than half of the time.

When critically appraising articles, 2 of 6 residents used specific rubrics half of the time; 4 of 6 less than half of the time. Most important, 5 of 6 residents agreed that the quality of evidence affected their management decisions more than half of the time or all of the time. Although it is clear that residents value evidence-based medicine and understand the importance of evaluating the quality of evidence, doing so currently might not be simple or practical.

An organized framework for appraising articles would streamline the process. Five of 6 residents agreed that the use of specific questions as a guide made it easier to appraise an article for the quality of its evidence. Four of 6 residents found that juxtaposing specific questions with the interactive reader was helpful; 5 of 6 agreed that they would use a web-based journal club platform if given the option.

Lastly, 5 of 6 residents agreed that if such a tool were available, a platform containing all major dermatology publications in an interactive reader format, along with relevant appraisal questions on the side, would be useful.

This pilot study augmented the typical journal club experience by emphasizing goal-directed reading and the importance of analyzing the quality of evidence. The combination of independent appraisal of an article using targeted questions and a group debrief led to better understanding of the evidence and its clinical applicability. The COVID-19 pandemic may be a better time than ever to explore innovative ways to teach evidence-based medicine in residency training.

- Mimouni D, Pavlovsky L, Akerman L, et al. Trends in dermatology publications over the past 15 years. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2010;11:55-58. doi:10.2165/11530190-000000000-00000.

- NEJM Knowledge+ Team. Exploring the ACGME Core Competencies: Practice-Based Learning and Improvement (part 2 of 7). Massachusetts Medical Society. NEJM Knowledge+ website. Published July 28, 2016. Accessed January 15, 2022. https://knowledgeplus.nejm.org/blog/practice-based-learning-and-improvement/

- University of Oxford. Critical appraisal tools. Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine website. Accessed January 2, 2022. www.cebm.ox.ac.uk/resources/ebm-tools/critical-appraisal-tools

To the Editor:

With a steady increase in dermatology publications over recent decades, there is an expanding pool of evidence to address clinical questions.1 Residency training is the time when appraising the medical literature and practicing evidence-based medicine is most honed. Evidence-based medicine is an essential component of Practice-based Learning and Improvement, a required core competency of the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education.2 Assimilation of new research evidence is traditionally taught through didactics and journal club discussions in residency.