User login

Appraising the Evidence Supporting Choosing Wisely® Recommendations

As healthcare costs rise, physicians and other stakeholders are now seeking innovative and effective ways to reduce the provision of low-value services.1,2 The Choosing Wisely® campaign aims to further this goal by promoting lists of specific procedures, tests, and treatments that providers should avoid in selected clinical settings.3 On February 21, 2013, the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) released 2 Choosing Wisely® lists consisting of adult and pediatric services that are seen as costly to consumers and to the healthcare system, but which are often nonbeneficial or even harmful.4,5 A total of 80 physician and nurse specialty societies have joined in submitting additional lists.

Despite the growing enthusiasm for this effort, questions remain regarding the Choosing Wisely® campaign’s ability to initiate the meaningful de-adoption of low-value services. Specifically, prior efforts to reduce the use of services deemed to be of questionable benefit have met several challenges.2,6 Early analyses of the Choosing Wisely® recommendations reveal similar roadblocks and variable uptakes of several recommendations.7-10 While the reasons for difficulties in achieving de-adoption are broad, one important factor in whether clinicians are willing to follow guideline recommendations from such initiatives as Choosing Wisely®is the extent to which they believe in the underlying evidence.11 The current work seeks to formally evaluate the evidence supporting the Choosing Wisely® recommendations, and to compare the quality of evidence supporting SHM lists to other published Choosing Wisely® lists.

METHODS

Data Sources

Using the online listing of published Choosing Wisely® recommendations, a dataset was generated incorporating all 320 recommendations comprising the 58 lists published through August, 2014; these include both the adult and pediatric hospital medicine lists released by the SHM.4,5,12 Although data collection ended at this point, this represents a majority of all 81 lists and 535 recommendations published through December, 2017. The reviewers (A.J.A., A.G., M.W., T.S.V., M.S., and C.R.C) extracted information about the references cited for each recommendation.

Data Analysis

The reviewers obtained each reference cited by a Choosing Wisely® recommendation and categorized it by evidence strength along the following hierarchy: clinical practice guideline (CPG), primary research, review article, expert opinion, book, or others/unknown. CPGs were used as the highest level of evidence based on standard expectations for methodological rigor.13 Primary research was further rated as follows: systematic reviews and meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials (RCTs), observational studies, and case series. Each recommendation was graded using only the strongest piece of evidence cited.

Guideline Appraisal

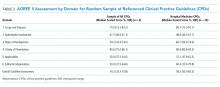

We further sought to evaluate the strength of referenced CPGs. To accomplish this, a 10% random sample of the Choosing Wisely® recommendations citing CPGs was selected, and the referenced CPGs were obtained. Separately, CPGs referenced by the SHM-published adult and pediatric lists were also obtained. For both groups, one CPG was randomly selected when a recommendation cited more than one CPG. These guidelines were assessed using the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation (AGREE) II instrument, a widely used instrument designed to assess CPG quality.14,15 AGREE II consists of 25 questions categorized into 6 domains: scope and purpose, stakeholder involvement, rigor of development, clarity of presentation, applicability, and editorial independence. Guidelines are also assigned an overall score. Two trained reviewers (A.J.A. and A.G.) assessed each of the sampled CPGs using a standardized form. Scores were then standardized using the method recommended by the instrument and reported as a percentage of available points. Although a standard interpretation of scores is not provided by the instrument, prior applications deemed scores below 50% as deficient16,17. When a recommendation item cited multiple CPGs, one was randomly selected. We also abstracted data on the year of publication, the evidence grade assigned to specific items recommended by Choosing Wisely®, and whether the CPG addressed the referring recommendation. All data management and analysis were conducted using Stata (V14.2, StataCorp, College Station, Texas).

RESULTS

A total of 320 recommendations were considered in our analysis, including 10 published across the 2 hospital medicine lists. When limited to the highest quality citation for each of the recommendations, 225 (70.3%) cited CPGs, whereas 71 (22.2%) cited primary research articles (Table 1). Specifically, 29 (9.1%) cited systematic reviews and meta-analyses, 28 (8.8%) cited observational studies, and 13 (4.1%) cited RCTs. One recommendation (0.3%) cited a case series as its highest level of evidence, 7 (2.2%) cited review articles, 7 (2.2%) cited editorials or opinion pieces, and 10 (3.1%) cited other types of documents, such as websites or books. Among hospital medicine recommendations, 9 (90%) referenced CPGs and 1 (10%) cited an observational study.

For the AGREE II assessment, we included 23 CPGs from the 225 referenced across all recommendations, after which we separately selected 6 CPGs from the hospital medicine recommendations. There was no overlap. Notably, 4 hospital medicine recommendations referenced a common CPG. Among the random sample of referenced CPGs, the median overall score obtained by using AGREE II was 54.2% (IQR 33.3%-70.8%, Table 2). This was similar to the median overall among hospital medicine guidelines (58.2%, IQR 50.0%-83.3%). Both hospital medicine and other sampled guidelines tended to score poorly in stakeholder involvement (48.6%, IQR 44.1%-61.1% and 47.2%, IQR 38.9%-61.1%, respectively). There were no significant differences between hospital medicine-referenced CPGs and the larger sample of CPGs in any AGREE II subdomains. The median age from the CPG publication to the list publication was 7 years (IQR 4–7) for hospital medicine recommendations and 3 years (IQR 2–6) for the nonhospital medicine recommendations. Substantial agreement was found between raters on the overall guideline assessment (ICC 0.80, 95% CI 0.58-0.91; Supplementary Table 1).

In terms of recommendation strengths and evidence grades, several recommendations were backed by Grades II–III (on a scale of I-III) evidence and level C (on a scale of A–C) recommendations in the reviewed CPG (Society of Maternal-Fetal Medicine, Recommendation 4, and Heart Rhythm Society, Recommendation 1). In one other case, the cited CPG did not directly address the Choosing Wisely® item (Society of Vascular Medicine, Recommendation 2).

DISCUSSION

Given the rising costs and the potential for iatrogenic harm, curbing ineffective practices has become an urgent concern. To achieve this, the Choosing Wisely® campaign has taken an important step by targeting certain low-value practices for de-adoption. However, the evidence supporting recommendations is variable. Specifically, 25 recommendations cited case series, review articles, or lower quality evidence as their highest level of support; moreover, among recommendations citing CPGs, quality, timeliness, and support for the recommendation item were variable. Although the hospital medicine lists tended to cite higher-quality evidence in the form of CPGs, these CPGs were often less recent than the guidelines referenced by other lists.

Our findings parallel those of other works that evaluate evidence among Choosing Wisely® recommendations and, more broadly, among CPGs.18–21 Lin and Yancey evaluated the quality of primary care-focused Choosing Wisely® recommendations using the Strength of Recommendation Taxonomy, a ranking system that evaluates evidence quality, consistency, and patient-centeredness.18 In their analysis, the authors found that many recommendations were based on lower quality evidence or relied on nonpatent-centered intermediate outcomes. Several groups, meanwhile, have evaluated the quality of evidence supporting CPG recommendations, finding them to be highly variable as well.19–21 These findings likely reflect inherent difficulties in the process, by which guideline development groups distill a broad evidence base into useful clinical recommendations, a reality that may have influenced the Choosing Wisely® list development groups seeking to make similar recommendations on low-value services.

These data should be taken in context due to several limitations. First, our sample of referenced CPGs includes only a small sample of all CPGs cited; thus, it may not be representative of all referenced guidelines. Second, the AGREE II assessment is inherently subjective, despite the availability of training materials. Third, data collection ended in April, 2014. Although this represents a majority of published lists to date, it is possible that more recent Choosing Wisely®lists include a stronger focus on evidence quality. Finally, references cited by Choosing Wisely®may not be representative of the entirety of the dataset that was considered when formulating the recommendations.

Despite these limitations, our findings suggest that Choosing Wisely®recommendations vary in terms of evidence strength. Although our results reveal that the majority of recommendations cite guidelines or high-quality original research, evidence gaps remain, with a small number citing low-quality evidence or low-quality CPGs as their highest form of support. Given the barriers to the successful de-implementation of low-value services, such campaigns as Choosing Wisely®face an uphill battle in their attempt to prompt behavior changes among providers and consumers.6-9 As a result, it is incumbent on funding agencies and medical journals to promote studies evaluating the harms and overall value of the care we deliver.

CONCLUSIONS

Although a majority of Choosing Wisely® recommendations cite high-quality evidence, some reference low-quality evidence or low-quality CPGs as their highest form of support. To overcome clinical inertia and other barriers to the successful de-implementation of low-value services, a clear rationale for the impetus to eradicate entrenched practices is critical.2,22 Choosing Wisely® has provided visionary leadership and a powerful platform to question low-value care. To expand the campaign’s efforts, the medical field must be able to generate the high-quality evidence necessary to support these efforts; further, list development groups must consider the availability of strong evidence when targeting services for de-implementation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported, in part, by a grant from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (No. K08HS020672, Dr. Cooke).

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

1. Institute of Medicine Roundtable on Evidence-Based Medicine. The Healthcare Imperative: Lowering Costs and Improving Outcomes: Workshop Series Summary. Yong P, Saudners R, Olsen L, editors. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press; 2010. PubMed

2. Weinberger SE. Providing high-value, cost-conscious care: a critical seventh general competency for physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(6):386-388. PubMed

3. Cassel CK, Guest JA. Choosing wisely: Helping physicians and patients make smart decisions about their care. JAMA. 2012;307(17):1801-1802. PubMed

4. Bulger J, Nickel W, Messler J, Goldstein J, O’Callaghan J, Auron M, et al. Choosing wisely in adult hospital medicine: Five opportunities for improved healthcare value. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(9):486-492. PubMed

5. Quinonez RA, Garber MD, Schroeder AR, Alverson BK, Nickel W, Goldstein J, et al. Choosing wisely in pediatric hospital medicine: Five opportunities for improved healthcare value. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(9):479-485. PubMed

6. Prasad V, Ioannidis JP. Evidence-based de-implementation for contradicted, unproven, and aspiring healthcare practices. Implement Sci. 2014;9:1. PubMed

7. Rosenberg A, Agiro A, Gottlieb M, Barron J, Brady P, Liu Y, et al. Early trends among seven recommendations from the Choosing Wisely campaign. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(12):1913-1920. PubMed

8. Zikmund-Fisher BJ, Kullgren JT, Fagerlin A, Klamerus ML, Bernstein SJ, Kerr EA. Perceived barriers to implementing individual Choosing Wisely® recommendations in two national surveys of primary care providers. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(2):210-217. PubMed

9. Bishop TF, Cea M, Miranda Y, Kim R, Lash-Dardia M, Lee JI, et al. Academic physicians’ views on low-value services and the choosing wisely campaign: A qualitative study. Healthc (Amsterdam, Netherlands). 2017;5(1-2):17-22. PubMed

10. Prochaska MT, Hohmann SF, Modes M, Arora VM. Trends in Troponin-only testing for AMI in academic teaching hospitals and the impact of Choosing Wisely®. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(12):957-962. PubMed

11. Cabana MD, Rand CS, Powe NR, Wu AW, Wilson MH, Abboud PA, et al. Why don’t physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? A framework for improvement. JAMA. 1999;282(15):1458-1465. PubMed

12. ABIM Foundation. ChoosingWisely.org Search Recommendations. 2014.

13. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Standards for Developing Trustworthy Clinical Practice Guidelines. Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust. Graham R, Mancher M, Miller Wolman D, Greenfield S, Steinberg E, editors. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press; 2011. PubMed

14. Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, et al. AGREE II: Advancing guideline development, reporting, and evaluation in health care. Prev Med (Baltim). 2010;51(5):421-424. PubMed

15. Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, et al. Development of the AGREE II, part 2: Assessment of validity of items and tools to support application. CMAJ. 2010;182(10):E472-E478. PubMed

16. He Z, Tian H, Song A, Jin L, Zhou X, Liu X, et al. Quality appraisal of clinical practice guidelines on pancreatic cancer. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94(12):e635. PubMed

17. Isaac A, Saginur M, Hartling L, Robinson JL. Quality of reporting and evidence in American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines. Pediatrics. 2013;131(4):732-738. PubMed

18. Lin KW, Yancey JR. Evaluating the Evidence for Choosing WiselyTM in Primary Care Using the Strength of Recommendation Taxonomy (SORT). J Am Board Fam Med. 2016;29(4):512-515. PubMed

19. McAlister FA, van Diepen S, Padwal RS, Johnson JA, Majumdar SR. How evidence-based are the recommendations in evidence-based guidelines? PLoS Med. 2007;4(8):e250. PubMed

20. Tricoci P, Allen JM, Kramer JM, Califf RM, Smith SC. Scientific evidence underlying the ACC/AHA clinical practice guidelines. JAMA. 2009;301(8):831-841. PubMed

21. Feuerstein JD, Gifford AE, Akbari M, Goldman J, Leffler DA, Sheth SG, et al. Systematic analysis underlying the quality of the scientific evidence and conflicts of interest in gastroenterology practice guidelines. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(11):1686-1693. PubMed

22. Robert G, Harlock J, Williams I. Disentangling rhetoric and reality: an international Delphi study of factors and processes that facilitate the successful implementation of decisions to decommission healthcare services. Implement Sci. 2014;9:123. PubMed

As healthcare costs rise, physicians and other stakeholders are now seeking innovative and effective ways to reduce the provision of low-value services.1,2 The Choosing Wisely® campaign aims to further this goal by promoting lists of specific procedures, tests, and treatments that providers should avoid in selected clinical settings.3 On February 21, 2013, the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) released 2 Choosing Wisely® lists consisting of adult and pediatric services that are seen as costly to consumers and to the healthcare system, but which are often nonbeneficial or even harmful.4,5 A total of 80 physician and nurse specialty societies have joined in submitting additional lists.

Despite the growing enthusiasm for this effort, questions remain regarding the Choosing Wisely® campaign’s ability to initiate the meaningful de-adoption of low-value services. Specifically, prior efforts to reduce the use of services deemed to be of questionable benefit have met several challenges.2,6 Early analyses of the Choosing Wisely® recommendations reveal similar roadblocks and variable uptakes of several recommendations.7-10 While the reasons for difficulties in achieving de-adoption are broad, one important factor in whether clinicians are willing to follow guideline recommendations from such initiatives as Choosing Wisely®is the extent to which they believe in the underlying evidence.11 The current work seeks to formally evaluate the evidence supporting the Choosing Wisely® recommendations, and to compare the quality of evidence supporting SHM lists to other published Choosing Wisely® lists.

METHODS

Data Sources

Using the online listing of published Choosing Wisely® recommendations, a dataset was generated incorporating all 320 recommendations comprising the 58 lists published through August, 2014; these include both the adult and pediatric hospital medicine lists released by the SHM.4,5,12 Although data collection ended at this point, this represents a majority of all 81 lists and 535 recommendations published through December, 2017. The reviewers (A.J.A., A.G., M.W., T.S.V., M.S., and C.R.C) extracted information about the references cited for each recommendation.

Data Analysis

The reviewers obtained each reference cited by a Choosing Wisely® recommendation and categorized it by evidence strength along the following hierarchy: clinical practice guideline (CPG), primary research, review article, expert opinion, book, or others/unknown. CPGs were used as the highest level of evidence based on standard expectations for methodological rigor.13 Primary research was further rated as follows: systematic reviews and meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials (RCTs), observational studies, and case series. Each recommendation was graded using only the strongest piece of evidence cited.

Guideline Appraisal

We further sought to evaluate the strength of referenced CPGs. To accomplish this, a 10% random sample of the Choosing Wisely® recommendations citing CPGs was selected, and the referenced CPGs were obtained. Separately, CPGs referenced by the SHM-published adult and pediatric lists were also obtained. For both groups, one CPG was randomly selected when a recommendation cited more than one CPG. These guidelines were assessed using the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation (AGREE) II instrument, a widely used instrument designed to assess CPG quality.14,15 AGREE II consists of 25 questions categorized into 6 domains: scope and purpose, stakeholder involvement, rigor of development, clarity of presentation, applicability, and editorial independence. Guidelines are also assigned an overall score. Two trained reviewers (A.J.A. and A.G.) assessed each of the sampled CPGs using a standardized form. Scores were then standardized using the method recommended by the instrument and reported as a percentage of available points. Although a standard interpretation of scores is not provided by the instrument, prior applications deemed scores below 50% as deficient16,17. When a recommendation item cited multiple CPGs, one was randomly selected. We also abstracted data on the year of publication, the evidence grade assigned to specific items recommended by Choosing Wisely®, and whether the CPG addressed the referring recommendation. All data management and analysis were conducted using Stata (V14.2, StataCorp, College Station, Texas).

RESULTS

A total of 320 recommendations were considered in our analysis, including 10 published across the 2 hospital medicine lists. When limited to the highest quality citation for each of the recommendations, 225 (70.3%) cited CPGs, whereas 71 (22.2%) cited primary research articles (Table 1). Specifically, 29 (9.1%) cited systematic reviews and meta-analyses, 28 (8.8%) cited observational studies, and 13 (4.1%) cited RCTs. One recommendation (0.3%) cited a case series as its highest level of evidence, 7 (2.2%) cited review articles, 7 (2.2%) cited editorials or opinion pieces, and 10 (3.1%) cited other types of documents, such as websites or books. Among hospital medicine recommendations, 9 (90%) referenced CPGs and 1 (10%) cited an observational study.

For the AGREE II assessment, we included 23 CPGs from the 225 referenced across all recommendations, after which we separately selected 6 CPGs from the hospital medicine recommendations. There was no overlap. Notably, 4 hospital medicine recommendations referenced a common CPG. Among the random sample of referenced CPGs, the median overall score obtained by using AGREE II was 54.2% (IQR 33.3%-70.8%, Table 2). This was similar to the median overall among hospital medicine guidelines (58.2%, IQR 50.0%-83.3%). Both hospital medicine and other sampled guidelines tended to score poorly in stakeholder involvement (48.6%, IQR 44.1%-61.1% and 47.2%, IQR 38.9%-61.1%, respectively). There were no significant differences between hospital medicine-referenced CPGs and the larger sample of CPGs in any AGREE II subdomains. The median age from the CPG publication to the list publication was 7 years (IQR 4–7) for hospital medicine recommendations and 3 years (IQR 2–6) for the nonhospital medicine recommendations. Substantial agreement was found between raters on the overall guideline assessment (ICC 0.80, 95% CI 0.58-0.91; Supplementary Table 1).

In terms of recommendation strengths and evidence grades, several recommendations were backed by Grades II–III (on a scale of I-III) evidence and level C (on a scale of A–C) recommendations in the reviewed CPG (Society of Maternal-Fetal Medicine, Recommendation 4, and Heart Rhythm Society, Recommendation 1). In one other case, the cited CPG did not directly address the Choosing Wisely® item (Society of Vascular Medicine, Recommendation 2).

DISCUSSION

Given the rising costs and the potential for iatrogenic harm, curbing ineffective practices has become an urgent concern. To achieve this, the Choosing Wisely® campaign has taken an important step by targeting certain low-value practices for de-adoption. However, the evidence supporting recommendations is variable. Specifically, 25 recommendations cited case series, review articles, or lower quality evidence as their highest level of support; moreover, among recommendations citing CPGs, quality, timeliness, and support for the recommendation item were variable. Although the hospital medicine lists tended to cite higher-quality evidence in the form of CPGs, these CPGs were often less recent than the guidelines referenced by other lists.

Our findings parallel those of other works that evaluate evidence among Choosing Wisely® recommendations and, more broadly, among CPGs.18–21 Lin and Yancey evaluated the quality of primary care-focused Choosing Wisely® recommendations using the Strength of Recommendation Taxonomy, a ranking system that evaluates evidence quality, consistency, and patient-centeredness.18 In their analysis, the authors found that many recommendations were based on lower quality evidence or relied on nonpatent-centered intermediate outcomes. Several groups, meanwhile, have evaluated the quality of evidence supporting CPG recommendations, finding them to be highly variable as well.19–21 These findings likely reflect inherent difficulties in the process, by which guideline development groups distill a broad evidence base into useful clinical recommendations, a reality that may have influenced the Choosing Wisely® list development groups seeking to make similar recommendations on low-value services.

These data should be taken in context due to several limitations. First, our sample of referenced CPGs includes only a small sample of all CPGs cited; thus, it may not be representative of all referenced guidelines. Second, the AGREE II assessment is inherently subjective, despite the availability of training materials. Third, data collection ended in April, 2014. Although this represents a majority of published lists to date, it is possible that more recent Choosing Wisely®lists include a stronger focus on evidence quality. Finally, references cited by Choosing Wisely®may not be representative of the entirety of the dataset that was considered when formulating the recommendations.

Despite these limitations, our findings suggest that Choosing Wisely®recommendations vary in terms of evidence strength. Although our results reveal that the majority of recommendations cite guidelines or high-quality original research, evidence gaps remain, with a small number citing low-quality evidence or low-quality CPGs as their highest form of support. Given the barriers to the successful de-implementation of low-value services, such campaigns as Choosing Wisely®face an uphill battle in their attempt to prompt behavior changes among providers and consumers.6-9 As a result, it is incumbent on funding agencies and medical journals to promote studies evaluating the harms and overall value of the care we deliver.

CONCLUSIONS

Although a majority of Choosing Wisely® recommendations cite high-quality evidence, some reference low-quality evidence or low-quality CPGs as their highest form of support. To overcome clinical inertia and other barriers to the successful de-implementation of low-value services, a clear rationale for the impetus to eradicate entrenched practices is critical.2,22 Choosing Wisely® has provided visionary leadership and a powerful platform to question low-value care. To expand the campaign’s efforts, the medical field must be able to generate the high-quality evidence necessary to support these efforts; further, list development groups must consider the availability of strong evidence when targeting services for de-implementation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported, in part, by a grant from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (No. K08HS020672, Dr. Cooke).

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

As healthcare costs rise, physicians and other stakeholders are now seeking innovative and effective ways to reduce the provision of low-value services.1,2 The Choosing Wisely® campaign aims to further this goal by promoting lists of specific procedures, tests, and treatments that providers should avoid in selected clinical settings.3 On February 21, 2013, the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) released 2 Choosing Wisely® lists consisting of adult and pediatric services that are seen as costly to consumers and to the healthcare system, but which are often nonbeneficial or even harmful.4,5 A total of 80 physician and nurse specialty societies have joined in submitting additional lists.

Despite the growing enthusiasm for this effort, questions remain regarding the Choosing Wisely® campaign’s ability to initiate the meaningful de-adoption of low-value services. Specifically, prior efforts to reduce the use of services deemed to be of questionable benefit have met several challenges.2,6 Early analyses of the Choosing Wisely® recommendations reveal similar roadblocks and variable uptakes of several recommendations.7-10 While the reasons for difficulties in achieving de-adoption are broad, one important factor in whether clinicians are willing to follow guideline recommendations from such initiatives as Choosing Wisely®is the extent to which they believe in the underlying evidence.11 The current work seeks to formally evaluate the evidence supporting the Choosing Wisely® recommendations, and to compare the quality of evidence supporting SHM lists to other published Choosing Wisely® lists.

METHODS

Data Sources

Using the online listing of published Choosing Wisely® recommendations, a dataset was generated incorporating all 320 recommendations comprising the 58 lists published through August, 2014; these include both the adult and pediatric hospital medicine lists released by the SHM.4,5,12 Although data collection ended at this point, this represents a majority of all 81 lists and 535 recommendations published through December, 2017. The reviewers (A.J.A., A.G., M.W., T.S.V., M.S., and C.R.C) extracted information about the references cited for each recommendation.

Data Analysis

The reviewers obtained each reference cited by a Choosing Wisely® recommendation and categorized it by evidence strength along the following hierarchy: clinical practice guideline (CPG), primary research, review article, expert opinion, book, or others/unknown. CPGs were used as the highest level of evidence based on standard expectations for methodological rigor.13 Primary research was further rated as follows: systematic reviews and meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials (RCTs), observational studies, and case series. Each recommendation was graded using only the strongest piece of evidence cited.

Guideline Appraisal

We further sought to evaluate the strength of referenced CPGs. To accomplish this, a 10% random sample of the Choosing Wisely® recommendations citing CPGs was selected, and the referenced CPGs were obtained. Separately, CPGs referenced by the SHM-published adult and pediatric lists were also obtained. For both groups, one CPG was randomly selected when a recommendation cited more than one CPG. These guidelines were assessed using the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation (AGREE) II instrument, a widely used instrument designed to assess CPG quality.14,15 AGREE II consists of 25 questions categorized into 6 domains: scope and purpose, stakeholder involvement, rigor of development, clarity of presentation, applicability, and editorial independence. Guidelines are also assigned an overall score. Two trained reviewers (A.J.A. and A.G.) assessed each of the sampled CPGs using a standardized form. Scores were then standardized using the method recommended by the instrument and reported as a percentage of available points. Although a standard interpretation of scores is not provided by the instrument, prior applications deemed scores below 50% as deficient16,17. When a recommendation item cited multiple CPGs, one was randomly selected. We also abstracted data on the year of publication, the evidence grade assigned to specific items recommended by Choosing Wisely®, and whether the CPG addressed the referring recommendation. All data management and analysis were conducted using Stata (V14.2, StataCorp, College Station, Texas).

RESULTS

A total of 320 recommendations were considered in our analysis, including 10 published across the 2 hospital medicine lists. When limited to the highest quality citation for each of the recommendations, 225 (70.3%) cited CPGs, whereas 71 (22.2%) cited primary research articles (Table 1). Specifically, 29 (9.1%) cited systematic reviews and meta-analyses, 28 (8.8%) cited observational studies, and 13 (4.1%) cited RCTs. One recommendation (0.3%) cited a case series as its highest level of evidence, 7 (2.2%) cited review articles, 7 (2.2%) cited editorials or opinion pieces, and 10 (3.1%) cited other types of documents, such as websites or books. Among hospital medicine recommendations, 9 (90%) referenced CPGs and 1 (10%) cited an observational study.

For the AGREE II assessment, we included 23 CPGs from the 225 referenced across all recommendations, after which we separately selected 6 CPGs from the hospital medicine recommendations. There was no overlap. Notably, 4 hospital medicine recommendations referenced a common CPG. Among the random sample of referenced CPGs, the median overall score obtained by using AGREE II was 54.2% (IQR 33.3%-70.8%, Table 2). This was similar to the median overall among hospital medicine guidelines (58.2%, IQR 50.0%-83.3%). Both hospital medicine and other sampled guidelines tended to score poorly in stakeholder involvement (48.6%, IQR 44.1%-61.1% and 47.2%, IQR 38.9%-61.1%, respectively). There were no significant differences between hospital medicine-referenced CPGs and the larger sample of CPGs in any AGREE II subdomains. The median age from the CPG publication to the list publication was 7 years (IQR 4–7) for hospital medicine recommendations and 3 years (IQR 2–6) for the nonhospital medicine recommendations. Substantial agreement was found between raters on the overall guideline assessment (ICC 0.80, 95% CI 0.58-0.91; Supplementary Table 1).

In terms of recommendation strengths and evidence grades, several recommendations were backed by Grades II–III (on a scale of I-III) evidence and level C (on a scale of A–C) recommendations in the reviewed CPG (Society of Maternal-Fetal Medicine, Recommendation 4, and Heart Rhythm Society, Recommendation 1). In one other case, the cited CPG did not directly address the Choosing Wisely® item (Society of Vascular Medicine, Recommendation 2).

DISCUSSION

Given the rising costs and the potential for iatrogenic harm, curbing ineffective practices has become an urgent concern. To achieve this, the Choosing Wisely® campaign has taken an important step by targeting certain low-value practices for de-adoption. However, the evidence supporting recommendations is variable. Specifically, 25 recommendations cited case series, review articles, or lower quality evidence as their highest level of support; moreover, among recommendations citing CPGs, quality, timeliness, and support for the recommendation item were variable. Although the hospital medicine lists tended to cite higher-quality evidence in the form of CPGs, these CPGs were often less recent than the guidelines referenced by other lists.

Our findings parallel those of other works that evaluate evidence among Choosing Wisely® recommendations and, more broadly, among CPGs.18–21 Lin and Yancey evaluated the quality of primary care-focused Choosing Wisely® recommendations using the Strength of Recommendation Taxonomy, a ranking system that evaluates evidence quality, consistency, and patient-centeredness.18 In their analysis, the authors found that many recommendations were based on lower quality evidence or relied on nonpatent-centered intermediate outcomes. Several groups, meanwhile, have evaluated the quality of evidence supporting CPG recommendations, finding them to be highly variable as well.19–21 These findings likely reflect inherent difficulties in the process, by which guideline development groups distill a broad evidence base into useful clinical recommendations, a reality that may have influenced the Choosing Wisely® list development groups seeking to make similar recommendations on low-value services.

These data should be taken in context due to several limitations. First, our sample of referenced CPGs includes only a small sample of all CPGs cited; thus, it may not be representative of all referenced guidelines. Second, the AGREE II assessment is inherently subjective, despite the availability of training materials. Third, data collection ended in April, 2014. Although this represents a majority of published lists to date, it is possible that more recent Choosing Wisely®lists include a stronger focus on evidence quality. Finally, references cited by Choosing Wisely®may not be representative of the entirety of the dataset that was considered when formulating the recommendations.

Despite these limitations, our findings suggest that Choosing Wisely®recommendations vary in terms of evidence strength. Although our results reveal that the majority of recommendations cite guidelines or high-quality original research, evidence gaps remain, with a small number citing low-quality evidence or low-quality CPGs as their highest form of support. Given the barriers to the successful de-implementation of low-value services, such campaigns as Choosing Wisely®face an uphill battle in their attempt to prompt behavior changes among providers and consumers.6-9 As a result, it is incumbent on funding agencies and medical journals to promote studies evaluating the harms and overall value of the care we deliver.

CONCLUSIONS

Although a majority of Choosing Wisely® recommendations cite high-quality evidence, some reference low-quality evidence or low-quality CPGs as their highest form of support. To overcome clinical inertia and other barriers to the successful de-implementation of low-value services, a clear rationale for the impetus to eradicate entrenched practices is critical.2,22 Choosing Wisely® has provided visionary leadership and a powerful platform to question low-value care. To expand the campaign’s efforts, the medical field must be able to generate the high-quality evidence necessary to support these efforts; further, list development groups must consider the availability of strong evidence when targeting services for de-implementation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported, in part, by a grant from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (No. K08HS020672, Dr. Cooke).

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

1. Institute of Medicine Roundtable on Evidence-Based Medicine. The Healthcare Imperative: Lowering Costs and Improving Outcomes: Workshop Series Summary. Yong P, Saudners R, Olsen L, editors. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press; 2010. PubMed

2. Weinberger SE. Providing high-value, cost-conscious care: a critical seventh general competency for physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(6):386-388. PubMed

3. Cassel CK, Guest JA. Choosing wisely: Helping physicians and patients make smart decisions about their care. JAMA. 2012;307(17):1801-1802. PubMed

4. Bulger J, Nickel W, Messler J, Goldstein J, O’Callaghan J, Auron M, et al. Choosing wisely in adult hospital medicine: Five opportunities for improved healthcare value. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(9):486-492. PubMed

5. Quinonez RA, Garber MD, Schroeder AR, Alverson BK, Nickel W, Goldstein J, et al. Choosing wisely in pediatric hospital medicine: Five opportunities for improved healthcare value. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(9):479-485. PubMed

6. Prasad V, Ioannidis JP. Evidence-based de-implementation for contradicted, unproven, and aspiring healthcare practices. Implement Sci. 2014;9:1. PubMed

7. Rosenberg A, Agiro A, Gottlieb M, Barron J, Brady P, Liu Y, et al. Early trends among seven recommendations from the Choosing Wisely campaign. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(12):1913-1920. PubMed

8. Zikmund-Fisher BJ, Kullgren JT, Fagerlin A, Klamerus ML, Bernstein SJ, Kerr EA. Perceived barriers to implementing individual Choosing Wisely® recommendations in two national surveys of primary care providers. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(2):210-217. PubMed

9. Bishop TF, Cea M, Miranda Y, Kim R, Lash-Dardia M, Lee JI, et al. Academic physicians’ views on low-value services and the choosing wisely campaign: A qualitative study. Healthc (Amsterdam, Netherlands). 2017;5(1-2):17-22. PubMed

10. Prochaska MT, Hohmann SF, Modes M, Arora VM. Trends in Troponin-only testing for AMI in academic teaching hospitals and the impact of Choosing Wisely®. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(12):957-962. PubMed

11. Cabana MD, Rand CS, Powe NR, Wu AW, Wilson MH, Abboud PA, et al. Why don’t physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? A framework for improvement. JAMA. 1999;282(15):1458-1465. PubMed

12. ABIM Foundation. ChoosingWisely.org Search Recommendations. 2014.

13. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Standards for Developing Trustworthy Clinical Practice Guidelines. Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust. Graham R, Mancher M, Miller Wolman D, Greenfield S, Steinberg E, editors. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press; 2011. PubMed

14. Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, et al. AGREE II: Advancing guideline development, reporting, and evaluation in health care. Prev Med (Baltim). 2010;51(5):421-424. PubMed

15. Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, et al. Development of the AGREE II, part 2: Assessment of validity of items and tools to support application. CMAJ. 2010;182(10):E472-E478. PubMed

16. He Z, Tian H, Song A, Jin L, Zhou X, Liu X, et al. Quality appraisal of clinical practice guidelines on pancreatic cancer. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94(12):e635. PubMed

17. Isaac A, Saginur M, Hartling L, Robinson JL. Quality of reporting and evidence in American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines. Pediatrics. 2013;131(4):732-738. PubMed

18. Lin KW, Yancey JR. Evaluating the Evidence for Choosing WiselyTM in Primary Care Using the Strength of Recommendation Taxonomy (SORT). J Am Board Fam Med. 2016;29(4):512-515. PubMed

19. McAlister FA, van Diepen S, Padwal RS, Johnson JA, Majumdar SR. How evidence-based are the recommendations in evidence-based guidelines? PLoS Med. 2007;4(8):e250. PubMed

20. Tricoci P, Allen JM, Kramer JM, Califf RM, Smith SC. Scientific evidence underlying the ACC/AHA clinical practice guidelines. JAMA. 2009;301(8):831-841. PubMed

21. Feuerstein JD, Gifford AE, Akbari M, Goldman J, Leffler DA, Sheth SG, et al. Systematic analysis underlying the quality of the scientific evidence and conflicts of interest in gastroenterology practice guidelines. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(11):1686-1693. PubMed

22. Robert G, Harlock J, Williams I. Disentangling rhetoric and reality: an international Delphi study of factors and processes that facilitate the successful implementation of decisions to decommission healthcare services. Implement Sci. 2014;9:123. PubMed

1. Institute of Medicine Roundtable on Evidence-Based Medicine. The Healthcare Imperative: Lowering Costs and Improving Outcomes: Workshop Series Summary. Yong P, Saudners R, Olsen L, editors. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press; 2010. PubMed

2. Weinberger SE. Providing high-value, cost-conscious care: a critical seventh general competency for physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(6):386-388. PubMed

3. Cassel CK, Guest JA. Choosing wisely: Helping physicians and patients make smart decisions about their care. JAMA. 2012;307(17):1801-1802. PubMed

4. Bulger J, Nickel W, Messler J, Goldstein J, O’Callaghan J, Auron M, et al. Choosing wisely in adult hospital medicine: Five opportunities for improved healthcare value. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(9):486-492. PubMed

5. Quinonez RA, Garber MD, Schroeder AR, Alverson BK, Nickel W, Goldstein J, et al. Choosing wisely in pediatric hospital medicine: Five opportunities for improved healthcare value. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(9):479-485. PubMed

6. Prasad V, Ioannidis JP. Evidence-based de-implementation for contradicted, unproven, and aspiring healthcare practices. Implement Sci. 2014;9:1. PubMed

7. Rosenberg A, Agiro A, Gottlieb M, Barron J, Brady P, Liu Y, et al. Early trends among seven recommendations from the Choosing Wisely campaign. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(12):1913-1920. PubMed

8. Zikmund-Fisher BJ, Kullgren JT, Fagerlin A, Klamerus ML, Bernstein SJ, Kerr EA. Perceived barriers to implementing individual Choosing Wisely® recommendations in two national surveys of primary care providers. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(2):210-217. PubMed

9. Bishop TF, Cea M, Miranda Y, Kim R, Lash-Dardia M, Lee JI, et al. Academic physicians’ views on low-value services and the choosing wisely campaign: A qualitative study. Healthc (Amsterdam, Netherlands). 2017;5(1-2):17-22. PubMed

10. Prochaska MT, Hohmann SF, Modes M, Arora VM. Trends in Troponin-only testing for AMI in academic teaching hospitals and the impact of Choosing Wisely®. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(12):957-962. PubMed

11. Cabana MD, Rand CS, Powe NR, Wu AW, Wilson MH, Abboud PA, et al. Why don’t physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? A framework for improvement. JAMA. 1999;282(15):1458-1465. PubMed

12. ABIM Foundation. ChoosingWisely.org Search Recommendations. 2014.

13. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Standards for Developing Trustworthy Clinical Practice Guidelines. Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust. Graham R, Mancher M, Miller Wolman D, Greenfield S, Steinberg E, editors. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press; 2011. PubMed

14. Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, et al. AGREE II: Advancing guideline development, reporting, and evaluation in health care. Prev Med (Baltim). 2010;51(5):421-424. PubMed

15. Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, et al. Development of the AGREE II, part 2: Assessment of validity of items and tools to support application. CMAJ. 2010;182(10):E472-E478. PubMed

16. He Z, Tian H, Song A, Jin L, Zhou X, Liu X, et al. Quality appraisal of clinical practice guidelines on pancreatic cancer. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94(12):e635. PubMed

17. Isaac A, Saginur M, Hartling L, Robinson JL. Quality of reporting and evidence in American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines. Pediatrics. 2013;131(4):732-738. PubMed

18. Lin KW, Yancey JR. Evaluating the Evidence for Choosing WiselyTM in Primary Care Using the Strength of Recommendation Taxonomy (SORT). J Am Board Fam Med. 2016;29(4):512-515. PubMed

19. McAlister FA, van Diepen S, Padwal RS, Johnson JA, Majumdar SR. How evidence-based are the recommendations in evidence-based guidelines? PLoS Med. 2007;4(8):e250. PubMed

20. Tricoci P, Allen JM, Kramer JM, Califf RM, Smith SC. Scientific evidence underlying the ACC/AHA clinical practice guidelines. JAMA. 2009;301(8):831-841. PubMed

21. Feuerstein JD, Gifford AE, Akbari M, Goldman J, Leffler DA, Sheth SG, et al. Systematic analysis underlying the quality of the scientific evidence and conflicts of interest in gastroenterology practice guidelines. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(11):1686-1693. PubMed

22. Robert G, Harlock J, Williams I. Disentangling rhetoric and reality: an international Delphi study of factors and processes that facilitate the successful implementation of decisions to decommission healthcare services. Implement Sci. 2014;9:123. PubMed

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine

Hospital Administrators’ Perspectives on Physician Engagement: A Qualitative Study

Disengaged physicians perform worse on multiple quality metrics and are more likely to make clinical errors.1,2 A growing body of literature has examined factors contributing to rising physician burnout, yet limited research has explored elements of physician engagement.3 Although some have described engagement as the polar opposite of burnout, addressing factors that contribute to burnout may not necessarily build physician engagement.4 The National Health Service (NHS) in the United Kingdom defines physician engagement as “the degree to which an employee is satisfied in their work, motivated to perform well, able to suggest and implement ideas for improvement, and their willingness to act as an advocate for their organization by recommending it as a place to work or be treated.”5

Few studies have attempted to document and interpret the variety of approaches that healthcare organizations have taken to identify and address this problem.6 The purpose of this study was to understand hospital administrators’ perspectives on issues related to physician engagement, including determinants of physician engagement, organizational efforts to improve physician engagement, and barriers to improving physician engagement.

METHODS

We conducted a qualitative study of hospital administrators by using an online anonymous questionnaire to explore perspectives on physician engagement. We used a convenience sample of hospital administrators affiliated with Vizient Inc. member hospitals. Vizient is the largest member-owned healthcare services company in the United States; and at the time of the study, it was composed of 1519 hospitals. Eligible hospital administrators included 2 hospital executive positions: Chief Medical Officers (CMOs) and Chief Quality Officers (CQOs). We chose to focus on CMOs and CQOs because their leadership roles overseeing physician employees may require them to address challenges with physician engagement.

The questionnaire focused on administrators’ perspectives on physician engagement, which we defined using the NHS definition stated above. Questions addressed perceived determinants of engagement, effective organizational efforts to improve engagement, and perceived barriers to improving engagement (supplementary Appendix 1). We included 2 yes/no questions and 4 open-ended questions. In May and June of 2016, we sent an e-mail to 432 unique hospital administrators explaining the purpose of the study and requested their participation through a hyperlink to an online questionnaire.

We used summary statistics to report results of yes/no questions and qualitative methods to analyze open-ended responses according to the principles of conventional content analysis, which avoids using preconceived categories and instead relies on inductive methods to allow categories to emerge from the data.7 Team members (T.J.R., K.O., and S.T.R.) performed close readings of responses and coded segments representing important concepts. Through iterative discussion, members of the research team reached consensus on the final code structure.

RESULTS

Our analyses focused on responses from 39 administrators that contained the most substantial qualitative information to the 4 open-ended questions included in the questionnaire. Among these respondents, 31 (79%) indicated that their hospital had surveyed physicians to assess their level of engagement, and 32 (82%) indicated that their hospital had implemented organizational efforts to improve physician engagement within the previous 3 years. Content analysis of open-ended responses yielded 5 themes that summarized perceived contributing factors to physician engagement: (1) physician-administration alignment, (2) physician input in decision-making, (3) appreciation of physician contributions, (4) communication between physicians and administration, and (5) hospital systems and workflow. In the Table, we present exemplary quotations for each theme and the question that prompted the quote.

DISCUSSION

Results of this study provide insight into administrators’ perspectives on organizational factors affecting physician engagement in hospital settings. The majority of respondents believed physician engagement was sufficiently important to survey physicians to assess their level of engagement and implement interventions to improve engagement. We identified several overarching themes that transcend individual questions related to the determinants of engagement, organizational efforts to improve engagement, and barriers to improving engagement. Many responses focused on the relationship between administrators and physicians. Administrators in our study may also have backgrounds as physicians, providing them with a unique perspective on the importance of this relationship.

The evolution of healthcare over the past several decades has shifted power dynamics away from autonomous physician practices, particularly in hospital settings.8 Our study suggests that hospital administrators recognize the potential impact these changes have had on physician engagement and are attempting to address the detrimental effects. Furthermore, administrators acknowledged the importance of organization-directed solutions to address problems with physician morale. This finding represents a paradigm shift away from previous approaches that involved interventions directed at individual physicians.9

Our results represent a call to action for both physicians and administrators to work together to develop organizational solutions to improve physician engagement. Further research is needed to investigate the most effective ways to improve and sustain engagement. At a time when physicians are increasingly dissatisfied with their current work, understanding how to improve physician engagement is critical to maintaining a healthy and productive physician workforce.

Disclosure

Will Dardani is an employee of Vizient Inc. No other authors have conflicts of interest to declare.

1. West MA, Dawson JF. Employee engagement and NHS performance. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/employee-engagement-nhs-performance-west-dawson-leadership-review2012-paper.pdf. Accessed July 9, 2017

2. Prins JT, Hoekstra-Weebers JE, Gazendam-Donofrio SM, et al. Burnout and engagement among resident doctors in the Netherlands: a national study. Med Educ. 2010;44(3):236-247. PubMed

3. Ruotsalainen JH, Verbeek JH, Marine A, Serra C. Preventing occupational stress in healthcare workers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015(4):CD002892. PubMed

4. Gonzalez-Roma V, Schaufeli WB, Bakker AB, Lloret S. Burnout and work engagement: Independent factors or opposite poles. J Vocat Behav. 2006;60(1):165-174.

5. National Health Service. The staff engagement challenge–a factsheet for chief executives. http://www.nhsemployers.org/~/media/Employers/Documents/Retain%20and%20improve/23705%20Chief-executive%20Factsheet _WEB.pdf. Accessed July 9, 2017

6. Taitz JM, Lee TH, Sequist TD. A framework for engaging physicians in quality and safety. BMJ Qual Saf. 2012;21(9):722-728. PubMed

7. Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277-1288. PubMed

8. Emanuel EJ, Pearson SD. Physician autonomy and health care reform. JAMA. 2012;307(4):367-368. PubMed

9. Panagioti M, Panagopoulou E, Bower P, et al. Controlled Interventions to Reduce Burnout in Physicians: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(2):195-205. PubMed

Disengaged physicians perform worse on multiple quality metrics and are more likely to make clinical errors.1,2 A growing body of literature has examined factors contributing to rising physician burnout, yet limited research has explored elements of physician engagement.3 Although some have described engagement as the polar opposite of burnout, addressing factors that contribute to burnout may not necessarily build physician engagement.4 The National Health Service (NHS) in the United Kingdom defines physician engagement as “the degree to which an employee is satisfied in their work, motivated to perform well, able to suggest and implement ideas for improvement, and their willingness to act as an advocate for their organization by recommending it as a place to work or be treated.”5

Few studies have attempted to document and interpret the variety of approaches that healthcare organizations have taken to identify and address this problem.6 The purpose of this study was to understand hospital administrators’ perspectives on issues related to physician engagement, including determinants of physician engagement, organizational efforts to improve physician engagement, and barriers to improving physician engagement.

METHODS

We conducted a qualitative study of hospital administrators by using an online anonymous questionnaire to explore perspectives on physician engagement. We used a convenience sample of hospital administrators affiliated with Vizient Inc. member hospitals. Vizient is the largest member-owned healthcare services company in the United States; and at the time of the study, it was composed of 1519 hospitals. Eligible hospital administrators included 2 hospital executive positions: Chief Medical Officers (CMOs) and Chief Quality Officers (CQOs). We chose to focus on CMOs and CQOs because their leadership roles overseeing physician employees may require them to address challenges with physician engagement.

The questionnaire focused on administrators’ perspectives on physician engagement, which we defined using the NHS definition stated above. Questions addressed perceived determinants of engagement, effective organizational efforts to improve engagement, and perceived barriers to improving engagement (supplementary Appendix 1). We included 2 yes/no questions and 4 open-ended questions. In May and June of 2016, we sent an e-mail to 432 unique hospital administrators explaining the purpose of the study and requested their participation through a hyperlink to an online questionnaire.

We used summary statistics to report results of yes/no questions and qualitative methods to analyze open-ended responses according to the principles of conventional content analysis, which avoids using preconceived categories and instead relies on inductive methods to allow categories to emerge from the data.7 Team members (T.J.R., K.O., and S.T.R.) performed close readings of responses and coded segments representing important concepts. Through iterative discussion, members of the research team reached consensus on the final code structure.

RESULTS

Our analyses focused on responses from 39 administrators that contained the most substantial qualitative information to the 4 open-ended questions included in the questionnaire. Among these respondents, 31 (79%) indicated that their hospital had surveyed physicians to assess their level of engagement, and 32 (82%) indicated that their hospital had implemented organizational efforts to improve physician engagement within the previous 3 years. Content analysis of open-ended responses yielded 5 themes that summarized perceived contributing factors to physician engagement: (1) physician-administration alignment, (2) physician input in decision-making, (3) appreciation of physician contributions, (4) communication between physicians and administration, and (5) hospital systems and workflow. In the Table, we present exemplary quotations for each theme and the question that prompted the quote.

DISCUSSION

Results of this study provide insight into administrators’ perspectives on organizational factors affecting physician engagement in hospital settings. The majority of respondents believed physician engagement was sufficiently important to survey physicians to assess their level of engagement and implement interventions to improve engagement. We identified several overarching themes that transcend individual questions related to the determinants of engagement, organizational efforts to improve engagement, and barriers to improving engagement. Many responses focused on the relationship between administrators and physicians. Administrators in our study may also have backgrounds as physicians, providing them with a unique perspective on the importance of this relationship.

The evolution of healthcare over the past several decades has shifted power dynamics away from autonomous physician practices, particularly in hospital settings.8 Our study suggests that hospital administrators recognize the potential impact these changes have had on physician engagement and are attempting to address the detrimental effects. Furthermore, administrators acknowledged the importance of organization-directed solutions to address problems with physician morale. This finding represents a paradigm shift away from previous approaches that involved interventions directed at individual physicians.9

Our results represent a call to action for both physicians and administrators to work together to develop organizational solutions to improve physician engagement. Further research is needed to investigate the most effective ways to improve and sustain engagement. At a time when physicians are increasingly dissatisfied with their current work, understanding how to improve physician engagement is critical to maintaining a healthy and productive physician workforce.

Disclosure

Will Dardani is an employee of Vizient Inc. No other authors have conflicts of interest to declare.

Disengaged physicians perform worse on multiple quality metrics and are more likely to make clinical errors.1,2 A growing body of literature has examined factors contributing to rising physician burnout, yet limited research has explored elements of physician engagement.3 Although some have described engagement as the polar opposite of burnout, addressing factors that contribute to burnout may not necessarily build physician engagement.4 The National Health Service (NHS) in the United Kingdom defines physician engagement as “the degree to which an employee is satisfied in their work, motivated to perform well, able to suggest and implement ideas for improvement, and their willingness to act as an advocate for their organization by recommending it as a place to work or be treated.”5

Few studies have attempted to document and interpret the variety of approaches that healthcare organizations have taken to identify and address this problem.6 The purpose of this study was to understand hospital administrators’ perspectives on issues related to physician engagement, including determinants of physician engagement, organizational efforts to improve physician engagement, and barriers to improving physician engagement.

METHODS

We conducted a qualitative study of hospital administrators by using an online anonymous questionnaire to explore perspectives on physician engagement. We used a convenience sample of hospital administrators affiliated with Vizient Inc. member hospitals. Vizient is the largest member-owned healthcare services company in the United States; and at the time of the study, it was composed of 1519 hospitals. Eligible hospital administrators included 2 hospital executive positions: Chief Medical Officers (CMOs) and Chief Quality Officers (CQOs). We chose to focus on CMOs and CQOs because their leadership roles overseeing physician employees may require them to address challenges with physician engagement.

The questionnaire focused on administrators’ perspectives on physician engagement, which we defined using the NHS definition stated above. Questions addressed perceived determinants of engagement, effective organizational efforts to improve engagement, and perceived barriers to improving engagement (supplementary Appendix 1). We included 2 yes/no questions and 4 open-ended questions. In May and June of 2016, we sent an e-mail to 432 unique hospital administrators explaining the purpose of the study and requested their participation through a hyperlink to an online questionnaire.

We used summary statistics to report results of yes/no questions and qualitative methods to analyze open-ended responses according to the principles of conventional content analysis, which avoids using preconceived categories and instead relies on inductive methods to allow categories to emerge from the data.7 Team members (T.J.R., K.O., and S.T.R.) performed close readings of responses and coded segments representing important concepts. Through iterative discussion, members of the research team reached consensus on the final code structure.

RESULTS

Our analyses focused on responses from 39 administrators that contained the most substantial qualitative information to the 4 open-ended questions included in the questionnaire. Among these respondents, 31 (79%) indicated that their hospital had surveyed physicians to assess their level of engagement, and 32 (82%) indicated that their hospital had implemented organizational efforts to improve physician engagement within the previous 3 years. Content analysis of open-ended responses yielded 5 themes that summarized perceived contributing factors to physician engagement: (1) physician-administration alignment, (2) physician input in decision-making, (3) appreciation of physician contributions, (4) communication between physicians and administration, and (5) hospital systems and workflow. In the Table, we present exemplary quotations for each theme and the question that prompted the quote.

DISCUSSION

Results of this study provide insight into administrators’ perspectives on organizational factors affecting physician engagement in hospital settings. The majority of respondents believed physician engagement was sufficiently important to survey physicians to assess their level of engagement and implement interventions to improve engagement. We identified several overarching themes that transcend individual questions related to the determinants of engagement, organizational efforts to improve engagement, and barriers to improving engagement. Many responses focused on the relationship between administrators and physicians. Administrators in our study may also have backgrounds as physicians, providing them with a unique perspective on the importance of this relationship.

The evolution of healthcare over the past several decades has shifted power dynamics away from autonomous physician practices, particularly in hospital settings.8 Our study suggests that hospital administrators recognize the potential impact these changes have had on physician engagement and are attempting to address the detrimental effects. Furthermore, administrators acknowledged the importance of organization-directed solutions to address problems with physician morale. This finding represents a paradigm shift away from previous approaches that involved interventions directed at individual physicians.9

Our results represent a call to action for both physicians and administrators to work together to develop organizational solutions to improve physician engagement. Further research is needed to investigate the most effective ways to improve and sustain engagement. At a time when physicians are increasingly dissatisfied with their current work, understanding how to improve physician engagement is critical to maintaining a healthy and productive physician workforce.

Disclosure

Will Dardani is an employee of Vizient Inc. No other authors have conflicts of interest to declare.

1. West MA, Dawson JF. Employee engagement and NHS performance. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/employee-engagement-nhs-performance-west-dawson-leadership-review2012-paper.pdf. Accessed July 9, 2017

2. Prins JT, Hoekstra-Weebers JE, Gazendam-Donofrio SM, et al. Burnout and engagement among resident doctors in the Netherlands: a national study. Med Educ. 2010;44(3):236-247. PubMed

3. Ruotsalainen JH, Verbeek JH, Marine A, Serra C. Preventing occupational stress in healthcare workers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015(4):CD002892. PubMed

4. Gonzalez-Roma V, Schaufeli WB, Bakker AB, Lloret S. Burnout and work engagement: Independent factors or opposite poles. J Vocat Behav. 2006;60(1):165-174.

5. National Health Service. The staff engagement challenge–a factsheet for chief executives. http://www.nhsemployers.org/~/media/Employers/Documents/Retain%20and%20improve/23705%20Chief-executive%20Factsheet _WEB.pdf. Accessed July 9, 2017

6. Taitz JM, Lee TH, Sequist TD. A framework for engaging physicians in quality and safety. BMJ Qual Saf. 2012;21(9):722-728. PubMed

7. Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277-1288. PubMed

8. Emanuel EJ, Pearson SD. Physician autonomy and health care reform. JAMA. 2012;307(4):367-368. PubMed

9. Panagioti M, Panagopoulou E, Bower P, et al. Controlled Interventions to Reduce Burnout in Physicians: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(2):195-205. PubMed

1. West MA, Dawson JF. Employee engagement and NHS performance. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/employee-engagement-nhs-performance-west-dawson-leadership-review2012-paper.pdf. Accessed July 9, 2017

2. Prins JT, Hoekstra-Weebers JE, Gazendam-Donofrio SM, et al. Burnout and engagement among resident doctors in the Netherlands: a national study. Med Educ. 2010;44(3):236-247. PubMed

3. Ruotsalainen JH, Verbeek JH, Marine A, Serra C. Preventing occupational stress in healthcare workers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015(4):CD002892. PubMed

4. Gonzalez-Roma V, Schaufeli WB, Bakker AB, Lloret S. Burnout and work engagement: Independent factors or opposite poles. J Vocat Behav. 2006;60(1):165-174.

5. National Health Service. The staff engagement challenge–a factsheet for chief executives. http://www.nhsemployers.org/~/media/Employers/Documents/Retain%20and%20improve/23705%20Chief-executive%20Factsheet _WEB.pdf. Accessed July 9, 2017

6. Taitz JM, Lee TH, Sequist TD. A framework for engaging physicians in quality and safety. BMJ Qual Saf. 2012;21(9):722-728. PubMed

7. Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277-1288. PubMed

8. Emanuel EJ, Pearson SD. Physician autonomy and health care reform. JAMA. 2012;307(4):367-368. PubMed

9. Panagioti M, Panagopoulou E, Bower P, et al. Controlled Interventions to Reduce Burnout in Physicians: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(2):195-205. PubMed

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine