User login

A Branching Algorithm

A 21-year-old man with a history of hypertension presented to the emergency department with four days of generalized abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting as well as one month of loose stools. He also had a headache (not further specified) for one day. Due to his nausea, he had been unable to take his medications for two days. Home blood pressure measurements over the preceding two days revealed systolic pressures exceeding 200 mm Hg. He did not experience fever, dyspnea, chest pain, vision changes, numbness, weakness, diaphoresis, or palpitations.

Abdominal pain with vomiting and diarrhea is often caused by a self-limited gastroenteritis. However, the priority initially is to exclude serious intraabdominal processes including arterial insufficiency, bowel obstruction, organ perforation, or organ-based infection or inflammation (eg, appendicitis, cholecystitis, pancreatitis). Essential hypertension accounts for 95% of cases of hypertension in the United States, but given this patient’s young age, secondary causes should be evaluated. These include primary aldosteronism (the most common endocrine cause for hypertension in young patients), chronic kidney disease, fibromuscular dysplasia, illicit drug use, hypercortisolism, pheochromocytoma, and coarctation of the aorta. Thyrotoxicosis can elevate blood pressure (although usually not to this extent) and cause hyperdefecation. While the etiology of the chronic hypertension is uncertain, the proximate cause of the acute rise in blood pressure is likely the stress of his acute illness and the inability to take his prescribed antihypertensive medications. In the setting of severe hypertension, his headache may reflect an intracranial hemorrhage and his abdominal pain could signal an aortic dissection.

His medical history included hypertension diagnosed at age 16 as well as anxiety diagnosed following a panic attack at age 19. Over the past year, he had also developed persistent nausea, which was attributed to gastroesophageal reflux disease. His medications included metoprolol 50 mg daily, amlodipine 5 mg daily, hydrochlorothiazide 12.5 mg daily, escitalopram 20 mg daily, and omeprazole 20 mg daily. His father and 15-year-old brother also had hypertension. He was a part-time student while working at a car dealership. He did not smoke or use drugs and he rarely drank alcohol.

The need for three antihypertensive medications (albeit at submaximal doses) reflects the severity of his hypertension (provided challenges with medication adherence have been excluded). His family history, especially that of his brother who was diagnosed with hypertension at an early age, and the patient’s own early onset hypertension point toward an inherited form of hypertension. Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease often results in hypertension before chronic kidney disease develops. Rare inherited forms of hypertension include familial hyperaldosteronism, apparent mineralocorticoid excess, Liddle syndrome, or a hereditary endocrine tumor syndrome predisposing to pheochromocytoma. Even among patients who report classic pheochromocytoma symptoms, such as headache and anxiety, the diagnosis remains unlikely as these symptoms are nonspecific and highly prevalent in the general population. However, once secondary hypertension is plausible or suspected, testing for hyperadrenergic states, which can also cause nausea and vomiting during times of catecholamine excess, should be pursued.

His temperature was 97.5°F, heart rate 95 beats per minute and regular, respiratory rate 18 breaths per minute, blood pressure 181/118 mm Hg (systolic and diastolic pressures in each arm were within 10 mm Hg), and oxygen saturation 100% on room air. Systolic and diastolic pressures did not decrease by more than 20 mm Hg and 10 mm Hg, respectively, after he stood for two minutes. His body mass index was 24 kg/m2. He was alert and appeared slightly anxious. There was a bounding point of maximal impulse in the fifth intercostal space at the midclavicular line and a 3/6 systolic murmur at the left upper sternal border with radiation to the carotid arteries. His abdomen was soft with generalized tenderness to palpation and without rebound tenderness, masses, organomegaly, or bruits. There was no costovertebral angle tenderness. No lymphadenopathy was present. His fundoscopic, pulmonary, skin and neurologic examinations were normal.

Laboratory studies revealed a white blood cell count of 13.3 × 103/uL with a normal differential, hemoglobin 13.9 g/dL, platelet count 373 × 103/uL, sodium 142 mmol/L, potassium 3.8 mmol/L, chloride 103 mmol/L,bicarbonate 25 mmol/L, blood urea nitrogen 12 mg/dL, creatinine 1.3 mg/dL (a baseline creatinine level was not available), glucose 88 mg/dL, calcium 10.6 mg/dL, albumin 4.9 g/dL, aspartate aminotransferase 27 IU/L, alanine aminotransferase 37 IU/L, and lipase 40 IU/L. Urinalysis revealed 5-10 white blood cells per high power field without casts and 10 mg/dL protein. Urine toxicology was not performed. Electrocardiogram (ECG) showed left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH). Chest radiography was normal.

The abdominal examination does not suggest peritonitis. The laboratory tests do not suggest inflammation of the liver, pancreas, or biliary tree as the cause of his abdominal pain or diarrhea. The murmur may indicate hypertrophic cardiomyopathy or a congenital anomaly such as bicuspid aortic valve; but neither would explain hypertension unless they were associated with another developmental abnormality, such as coarctation of the aorta. Tricuspid regurgitation is conceivable and if confirmed, might raise concern for carcinoid syndrome, which can cause diarrhea. The normal neurologic examination, including the absence of papilledema, lowers suspicion of intracranial hemorrhage as a cause of his headache.

The albumin of 4.9 g/dL likely reflects hypovolemia resulting from vomiting and diarrhea. Vasoconstriction associated with pheochromocytoma can cause pressure diuresis and resultant hypovolemia. Hyperaldosteronism arising from bilateral adrenal hyperplasia or adrenal adenoma commonly causes hypokalemia, although this is not a universal feature.

The duration of his mildly decreased glomerular filtration rate is uncertain. He may have chronic kidney disease from sustained hypertension, or acute kidney injury from hypovolemia. The mild pyuria could indicate infection or renal calculi, either of which could account for generalized abdominal pain or could reflect an acute renal injury from acute interstitial nephritis from his proton pump inhibitor or hydrochlorothiazide.

LVH on the ECG indicates longstanding hypertension. The chest radiograph does not reveal clues to the etiology of or sequelae from hypertension. In particular, there is no widened aorta to suggest aortic dissection, no pulmonary edema to indicate heart failure, and no rib notching that points toward aortic coarctation. A transthoracic echocardiogram to assess for valvular and other structural abnormalities is warranted.

Tests for secondary hypertension should be sent, including serum aldosterone and renin levels to assess for primary aldosteronism and plasma or 24-hour urine normetanephrine and metanephrine levels to assess for pheochromocytoma. Biochemical evaluation is the mainstay for endocrine hypertension evaluation and should be followed by imaging if abnormal results are found.

Intact parathyroid hormone (PTH) was 78 pg/mL (normal, 10-65 pg/mL), thyroid stimulating hormone 3.6 mIU/L (normal, 0.30-5.50 mIU/L), and morning cortisol 4.1 ug/dL (normal, >7.0 ug/dL). Plasma aldosterone was 14.6 ng/dL (normal, 1-16 ng/dL), plasma renin activity 3.6 ng/mL/hr (normal, 0.5-3.5 ng/mL/hr), and aldosterone-renin ratio 4.1 (normal, <20). Transthoracic echocardiogram showed LVH with normal valves, wall motion, and proximal aorta; the left ventricular ejection fraction was 70%. Magnetic resonance angiography of the renal vessels demonstrated no abnormalities.

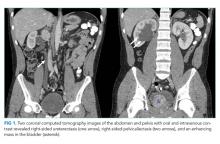

Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis with oral and intravenous contrast revealed a 5 cm heterogeneous enhancing mass associated with the prostate gland extending into the base of the bladder. The mass obstructed the right renal collecting system and ureter causing severe right-sided ureterectasis and hydronephrosis. There was also 2.8 cm right-sided paracaval lymph node enlargement and 2.1 cm right-sided and 1.5 cm left-sided external iliac lymph node enlargement (Figure 1). There were no adrenal masses.

He is young for prostate, bladder, or colorectal cancer, but early onset variations of these tumors, along with metastatic testicular cancer, must be considered for the pelvic mass and associated lymphadenopathy. Prostatic masses can be infectious (eg, abscess) or malignant (eg, adenocarcinoma, small cell carcinoma). Additional considerations for abdominopelvic cancer are sarcomas, germ cell tumors, or lymphoma. A low aldosterone-renin ratio coupled with a normal potassium level makes primary aldosteronism unlikely. The normal angiography excludes renovascular hypertension.

His abdominal pain and gastrointestinal symptoms could arise from irritation of the bowel, distension of the right-sided urinary collecting system, or products secreted from the mass (eg, catecholamines). The hyperdynamic precordium, elevated ejection fraction, and murmur may reflect augmented blood flow from a hyperadrenergic state. A unifying diagnosis would be a pheochromocytoma. However, given the normal appearance of the adrenal glands on CT imaging, catecholamines arising from a paraganglioma, a tumor of the autonomic nervous system, is more likely. These tumors often secrete catecholamines and can be metastatic (suggested here by the lymphadenopathy). Functional imaging or biopsy of either the mass or an adjacent lymph node is indicated. However, because of the possibility of a catecholamine-secreting tumor, he should be treated with an alpha-adrenergic receptor antagonist before undergoing a biopsy to prevent unopposed vasoconstriction from catecholamine leakage.

Scrotal ultrasound revealed no evidence of a testicular tumor. Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) was 179 IU/L (normal, 120-240 IU/L) and prostate specific antigen (PSA) was 0.7 ng/mL (normal, <2.5 ng/mL). The patient was given amlodipine and labetalol with improvement of blood pressures to 160s/100s. His creatinine decreased to 1.1 mg/dL. He underwent CT-guided biopsy of a pelvic lymph node. CT of the head without intravenous contrast demonstrated no intracranial abnormalities. His headache resolved with improvement in blood pressure, and he had minimal gastrointestinal symptoms during his hospitalization. No stool studies were sent. A right-sided percutaneous nephrostomy was placed which yielded >15 L of urine from the tube over the next four days.

Upon the first episode of micturition through the urethra four days after percutaneous nephrostomy placement, he experienced severe lightheadedness, diaphoresis, and palpitations. These symptoms prompted him to recall similar episodes following micturition for several months prior to his hospitalization.

It is likely that contraction of the bladder during episodes of urination caused irritation of the pelvic mass, leading to catecholamine secretion. Another explanation for his recurrent lightheadedness would be a neurocardiogenic reflex with micturition (which when it culminates with loss of consciousness is called micturition syncope), but this would not explain his hypertension or bladder mass.

Biochemical tests that were ordered on admission but sent to a reference lab then returned. Plasma metanephrine was 0.2 nmol/L (normal, <0.5 nmol/L) and plasma normetanephrine 34.6 nmol/L (normal, <0.9 nmol/L). His 24-hour urine metanephrine was 72 ug/24 hr (normal, 0-300 ug/24 hr) and normetanephrine 8,511 ug/24 hr (normal, 50-800 ug/24 hr).

The markedly elevated plasma and urine normetanephrine levels confirm a diagnosis of a catecholamine-secreting tumor (paraganglioma). The tissue obtained from the CT-guided lymph node biopsy should be sent for markers of neuroendocrine tumors including chromogranin.

Lymph node biopsy revealed metastatic paraganglioma that was chromogranin A and synaptophysin positive (Figure 2). A fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) scan disclosed skull metastases. He was treated with phenoxybenzamine, amlodipine, and labetalol. Surgical resection of the pelvic mass was discussed, but the patient elected to defer surgery as the location of the primary tumor made it challenging to resect and would have required an ileal conduit.

After the diagnosis was made, the patient’s family recalled that a maternal uncle had been diagnosed with a paraganglioma of the carotid body. Genetic testing of the patient identified a succinate dehydrogenase complex subunit B (SDHB) pathogenic variant and confirmed hereditary paraganglioma syndrome (HPGL). One year after the diagnosis, liver and lung metastases developed. He was treated with lanreotide (somatostatin analogue), capecitabine, and temozolomide, as well as a craniotomy and radiotherapy for palliation of bony metastases. The patient died less than two years after diagnosis.

DISCUSSION

Most patients with hypertension (defined as blood pressure >130/80 mm Hg1) do not have an identifiable etiology (primary hypertension). Many components of this patient’s history, however, including his young age of onset, a teenage sibling with hypertension, lack of obesity, hypertension refractory to multiple medications, and LVH suggested secondary hypertension. Hypertension onset at an age less than 30 years, resistance to three or more medications,1,2 and/or acute onset hypertension at any age should prompt an evaluation for secondary causes.1 The prevalence of secondary hypertension is approximately 30% in hypertensive patients ages 18 to 40 years compared with 5%-10% in the overall adult population with hypertension.3 Among children and adolescents ages 0 to 19 years with hypertension, the prevalence of secondary hypertension may be as high as 57%.4

The most common etiology of secondary hypertension is primary aldosteronism.5,6 However, in young adults (ages 19 to 39 years), common etiologies also include renovascular disease and renal parenchymal disease.7 Other causes include obstructive sleep apnea, medications, stimulants (cocaine and amphetamines),8 and endocrinopathies such as thyrotoxicosis, Cushing syndrome, and catecholamine-secreting tumors.7 Less than 1% of secondary hypertension in all adults is due to catecholamine-secreting tumors, and the minority of those catecholamine-secreting tumors are paragangliomas.9

Paragangliomas are tumors of the peripheral autonomic nervous system. These neoplasms arise in the sympathetic and parasympathetic chains along the paravertebral and paraaortic axes. They are closely related to pheochromocytomas, which arise in the adrenal medulla.9 Most head and neck paragangliomas are biochemically silent and are generally discovered due to mass effect.10 The subset of paragangliomas that secrete catecholamines most often arise in the abdomen and pelvis, and their clinical presentation mimics that of pheochromocytomas, including episodic hypertension, palpitations, pallor, and diaphoresis.

This patient had persistent, nonepisodic hypertension, while palpitations and diaphoresis only manifested following micturition. Other cases of urinary bladder paragangliomas have described micturition-associated symptoms and hypertensive crises. Three-fold increases of catecholamine secretion after micturition have been observed in these patients, likely due to muscle contraction and pressure changes in the bladder leading to the systemic release of catecholamines.11

Epinephrine and norepinephrine are monoamine neurotransmitters that activate alpha-adrenergic and beta-adrenergic receptors. Adrenergic receptors are present in all tissues of the body but have prominent effects on the smooth muscle in the vasculature, gastrointestinal tract, urinary tract, and airways.12 Alpha-adrenergic vasoconstriction causes hypertension, which is commonly observed in patients with catecholamine-secreting tumors.10 Catecholamine excess due to secretion from these tumors causes headache in 60%-80% of patients, tachycardia/palpitations in 50%-70%, anxiety in 20%-40%, and nausea in 20%-25%.10 Other symptoms include sweating, pallor, dyspnea, and vertigo.9,10 This patient’s chronic nausea, which was attributed to gastroesophageal reflux, and his anxiety, attributed to generalized anxiety disorder, were likely symptoms of catecholamine excess.13

The best test for the diagnosis of paragangliomas and pheochromocytomas is the measurement of plasma free or 24-hour urinary fractionated metanephrines (test sensitivity of >90% and >90%, respectively).14 Screening for pheochromocytoma should be considered in hypertensive patients who have symptoms of catecholamine excess, refractory or paroxysmal hypertension, and/or familial pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma syndromes.15 Screening for pheochromocytoma should also be performed in children and adolescents with systolic or diastolic blood pressure that is greater than the 95th percentile for their age plus 5 mm Hg.16

While a typical tumor location and elevated metanephrine levels are sufficient to make the diagnosis of a pheochromocytoma or catecholamine-secreting paraganglioma, functional imaging with FDG-PET, Ga-DOTATATE-PET, or 123I-meta-iodobenzylguanidine (123I-MIBG) can further confirm the diagnosis and detect distant metastases. However, imaging has low sensitivity for these tumors and thus should only be considered for patients in whom metastatic disease is suspected.14 Biopsy is rarely needed and should be reserved for unusual metastatic locations. Treatment with an alpha-adrenergic receptor antagonist often reduces symptoms and lowers blood pressure. Definitive management typically involves surgical resection for benign disease. Surgery, radionuclide therapy, or chemotherapy is used for malignant disease.

While most pheochromocytomas are sporadic, up to 40% of paragangliomas are due to germline pathogenic variants.17 Mutations in the succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) group of genes are the most common germline pathogenic variants in the autosomal dominant hereditary paraganglioma syndrome (HPGL). Most paragangliomas and pheochromocytomas are localized and benign, but 10%-15% are metastatic.18 SDHB mutations are associated with a high risk of metastasis.19 Thus, genetic testing for patients and subsequent cascade testing to identify at-risk family members is advised in all patients with pheochromocytomas or paragangliomas.20 This patient’s younger brother and mother were both found to carry the same pathogenic SDHB variant, but neither was found to have paragangliomas. Annual metanephrine levels (urine or plasma) and every other year whole-body magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans were recommended for tumor surveillance.

The clinician team followed a logical branching algorithm for the diagnosis of severe hypertension with biochemical testing, advanced imaging, histology, and genetic testing to arrive at the final diagnosis of hereditary paraganglioma syndrome. Although this patient presented for urgent care because of the acute effects of catecholamine excess, he suffered from chronic effects (nausea, anxiety, and hypertension) for years. Each symptom had been diagnosed and treated in isolation, but the combination and severity in a young patient suggested a unifying diagnosis. The family history of hypertension (brother and father) suggested an inherited diagnosis from the father’s family, but the final answer rested on the other branch (maternal uncle) of the family tree.

KEY TEACHING POINTS

- Hypertension in a young adult is due to a secondary cause in up to 30% of patients.

- Pathologic catecholamine excess leads to hypertension, tachycardia, pallor, sweating, anxiety, and nausea. A sustained and unexplained combination of these symptoms should prompt a biochemical evaluation for pheochromocytoma or paraganglioma.

- Paragangliomas are tumors of the autonomic nervous system. The frequency of catecholamine secretion depends on their location in the body, and they are commonly caused by germline pathogenic variants.

Acknowledgments

This conundrum was presented during a live Grand Rounds with the expert clinician’s responses recorded and edited for space and clarity.

Disclosures

Dr. Dhaliwal reports speaking honoraria from ISMIE Mutual Insurance Company and GE Healthcare. All other authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

No sources of funding.

1. Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension. 2018;71(6):e13-e115. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYP.0000000000000065.

2. Acelajado MC, Calhoun DA. Resistant hypertension, secondary hypertension, and hypertensive crises: diagnostic evaluation and treatment. Cardiol Clin. 2010;28(4):639-654. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccl.2010.07.002.

3. Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure. Hypertension. 2003;42(6):1206-1252. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.HYP.0000107251.49515.c2.

4. Gupta-Malhotra M, Banker A, Shete S, et al. Essential hypertension vs. secondary hypertension among children. Am J Hypertens. 2015;28(1):73-80. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajh/hpu083.

5. Mosso L, Carvajal C, Gonzalez A, et al. Primary aldosteronism and hypertensive disease. Hypertension. 2003;42(2):161-165. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.HYP.0000079505.25750.11.

6. Kayser SC, Dekkers T, Groenewoud HJ, et al. Study heterogeneity and estimation of prevalence of primary aldosteronism: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;101(7):2826-2835. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2016-1472.

7. Charles L, Triscott J, Dobbs B. Secondary hypertension: discovering the underlying cause. Am Fam Physician. 2017;96(7):453-461.

8. Aronow WS. Drug-induced causes of secondary hypertension. Ann Transl Med. 2017;5(17):349. https://doi.org/10.21037/atm.2017.06.16.

9. Lenders JW, Eisenhofer G, Mannelli M, Pacak K. Phaeochromocytoma. Lancet. 2005;366(9486):665-675. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67139-5.

10. Mannelli M, Lenders JW, Pacak K, Parenti G, Eisenhofer G. Subclinical phaeochromocytoma. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;26(4):507-515. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beem.2011.10.008.

11. Kappers MH, van den Meiracker AH, Alwani RA, Kats E, Baggen MG. Paraganglioma of the urinary bladder. Neth J Med. 2008;66(4):163-165.

12. Paravati S, Warrington SJ. Physiology, Catecholamines. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing LLC; 2019.

13. King KS, Darmani NA, Hughes MS, Adams KT, Pacak K. Exercise-induced nausea and vomiting: another sign and symptom of pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Endocrine. 2010;37(3):403-407. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12020-010-9319-3.

14. Lenders JW, Duh QY, Eisenhofer G, et al. Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(6):1915-1942. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2014-1498.

15. Lenders JWM, Eisenhofer G. Update on modern management of pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul). 2017;32(2):152-161. https://doi.org/10.3803/EnM.2017.32.2.152.

16. National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group. The fourth report on the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2004;114(2):555-576.

17. Else T, Greenberg S, Fishbein L. Hereditary Paraganglioma-Pheochromocytoma Syndromes. In: Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, et al., eds. Gene Reviews. Seattle, WA: University of Washington; 1993.

18. Goldstein RE, O’Neill JA, Jr., Holcomb GW, 3rd, et al. Clinical experience over 48 years with pheochromocytoma. Ann Surg. 1999;229(6):755-764; discussion 764-756. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000658-199906000-00001.

19. Amar L, Baudin E, Burnichon N, et al. Succinate dehydrogenase B gene mutations predict survival in patients with malignant pheochromocytomas or paragangliomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92(10):3822-3828. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2007-0709.

20. Favier J, Amar L, Gimenez-Roqueplo AP. Paraganglioma and phaeochromocytoma: from genetics to personalized medicine. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2015;11(2):101-111. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrendo.2014.188.

A 21-year-old man with a history of hypertension presented to the emergency department with four days of generalized abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting as well as one month of loose stools. He also had a headache (not further specified) for one day. Due to his nausea, he had been unable to take his medications for two days. Home blood pressure measurements over the preceding two days revealed systolic pressures exceeding 200 mm Hg. He did not experience fever, dyspnea, chest pain, vision changes, numbness, weakness, diaphoresis, or palpitations.

Abdominal pain with vomiting and diarrhea is often caused by a self-limited gastroenteritis. However, the priority initially is to exclude serious intraabdominal processes including arterial insufficiency, bowel obstruction, organ perforation, or organ-based infection or inflammation (eg, appendicitis, cholecystitis, pancreatitis). Essential hypertension accounts for 95% of cases of hypertension in the United States, but given this patient’s young age, secondary causes should be evaluated. These include primary aldosteronism (the most common endocrine cause for hypertension in young patients), chronic kidney disease, fibromuscular dysplasia, illicit drug use, hypercortisolism, pheochromocytoma, and coarctation of the aorta. Thyrotoxicosis can elevate blood pressure (although usually not to this extent) and cause hyperdefecation. While the etiology of the chronic hypertension is uncertain, the proximate cause of the acute rise in blood pressure is likely the stress of his acute illness and the inability to take his prescribed antihypertensive medications. In the setting of severe hypertension, his headache may reflect an intracranial hemorrhage and his abdominal pain could signal an aortic dissection.

His medical history included hypertension diagnosed at age 16 as well as anxiety diagnosed following a panic attack at age 19. Over the past year, he had also developed persistent nausea, which was attributed to gastroesophageal reflux disease. His medications included metoprolol 50 mg daily, amlodipine 5 mg daily, hydrochlorothiazide 12.5 mg daily, escitalopram 20 mg daily, and omeprazole 20 mg daily. His father and 15-year-old brother also had hypertension. He was a part-time student while working at a car dealership. He did not smoke or use drugs and he rarely drank alcohol.

The need for three antihypertensive medications (albeit at submaximal doses) reflects the severity of his hypertension (provided challenges with medication adherence have been excluded). His family history, especially that of his brother who was diagnosed with hypertension at an early age, and the patient’s own early onset hypertension point toward an inherited form of hypertension. Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease often results in hypertension before chronic kidney disease develops. Rare inherited forms of hypertension include familial hyperaldosteronism, apparent mineralocorticoid excess, Liddle syndrome, or a hereditary endocrine tumor syndrome predisposing to pheochromocytoma. Even among patients who report classic pheochromocytoma symptoms, such as headache and anxiety, the diagnosis remains unlikely as these symptoms are nonspecific and highly prevalent in the general population. However, once secondary hypertension is plausible or suspected, testing for hyperadrenergic states, which can also cause nausea and vomiting during times of catecholamine excess, should be pursued.

His temperature was 97.5°F, heart rate 95 beats per minute and regular, respiratory rate 18 breaths per minute, blood pressure 181/118 mm Hg (systolic and diastolic pressures in each arm were within 10 mm Hg), and oxygen saturation 100% on room air. Systolic and diastolic pressures did not decrease by more than 20 mm Hg and 10 mm Hg, respectively, after he stood for two minutes. His body mass index was 24 kg/m2. He was alert and appeared slightly anxious. There was a bounding point of maximal impulse in the fifth intercostal space at the midclavicular line and a 3/6 systolic murmur at the left upper sternal border with radiation to the carotid arteries. His abdomen was soft with generalized tenderness to palpation and without rebound tenderness, masses, organomegaly, or bruits. There was no costovertebral angle tenderness. No lymphadenopathy was present. His fundoscopic, pulmonary, skin and neurologic examinations were normal.

Laboratory studies revealed a white blood cell count of 13.3 × 103/uL with a normal differential, hemoglobin 13.9 g/dL, platelet count 373 × 103/uL, sodium 142 mmol/L, potassium 3.8 mmol/L, chloride 103 mmol/L,bicarbonate 25 mmol/L, blood urea nitrogen 12 mg/dL, creatinine 1.3 mg/dL (a baseline creatinine level was not available), glucose 88 mg/dL, calcium 10.6 mg/dL, albumin 4.9 g/dL, aspartate aminotransferase 27 IU/L, alanine aminotransferase 37 IU/L, and lipase 40 IU/L. Urinalysis revealed 5-10 white blood cells per high power field without casts and 10 mg/dL protein. Urine toxicology was not performed. Electrocardiogram (ECG) showed left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH). Chest radiography was normal.

The abdominal examination does not suggest peritonitis. The laboratory tests do not suggest inflammation of the liver, pancreas, or biliary tree as the cause of his abdominal pain or diarrhea. The murmur may indicate hypertrophic cardiomyopathy or a congenital anomaly such as bicuspid aortic valve; but neither would explain hypertension unless they were associated with another developmental abnormality, such as coarctation of the aorta. Tricuspid regurgitation is conceivable and if confirmed, might raise concern for carcinoid syndrome, which can cause diarrhea. The normal neurologic examination, including the absence of papilledema, lowers suspicion of intracranial hemorrhage as a cause of his headache.

The albumin of 4.9 g/dL likely reflects hypovolemia resulting from vomiting and diarrhea. Vasoconstriction associated with pheochromocytoma can cause pressure diuresis and resultant hypovolemia. Hyperaldosteronism arising from bilateral adrenal hyperplasia or adrenal adenoma commonly causes hypokalemia, although this is not a universal feature.

The duration of his mildly decreased glomerular filtration rate is uncertain. He may have chronic kidney disease from sustained hypertension, or acute kidney injury from hypovolemia. The mild pyuria could indicate infection or renal calculi, either of which could account for generalized abdominal pain or could reflect an acute renal injury from acute interstitial nephritis from his proton pump inhibitor or hydrochlorothiazide.

LVH on the ECG indicates longstanding hypertension. The chest radiograph does not reveal clues to the etiology of or sequelae from hypertension. In particular, there is no widened aorta to suggest aortic dissection, no pulmonary edema to indicate heart failure, and no rib notching that points toward aortic coarctation. A transthoracic echocardiogram to assess for valvular and other structural abnormalities is warranted.

Tests for secondary hypertension should be sent, including serum aldosterone and renin levels to assess for primary aldosteronism and plasma or 24-hour urine normetanephrine and metanephrine levels to assess for pheochromocytoma. Biochemical evaluation is the mainstay for endocrine hypertension evaluation and should be followed by imaging if abnormal results are found.

Intact parathyroid hormone (PTH) was 78 pg/mL (normal, 10-65 pg/mL), thyroid stimulating hormone 3.6 mIU/L (normal, 0.30-5.50 mIU/L), and morning cortisol 4.1 ug/dL (normal, >7.0 ug/dL). Plasma aldosterone was 14.6 ng/dL (normal, 1-16 ng/dL), plasma renin activity 3.6 ng/mL/hr (normal, 0.5-3.5 ng/mL/hr), and aldosterone-renin ratio 4.1 (normal, <20). Transthoracic echocardiogram showed LVH with normal valves, wall motion, and proximal aorta; the left ventricular ejection fraction was 70%. Magnetic resonance angiography of the renal vessels demonstrated no abnormalities.

Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis with oral and intravenous contrast revealed a 5 cm heterogeneous enhancing mass associated with the prostate gland extending into the base of the bladder. The mass obstructed the right renal collecting system and ureter causing severe right-sided ureterectasis and hydronephrosis. There was also 2.8 cm right-sided paracaval lymph node enlargement and 2.1 cm right-sided and 1.5 cm left-sided external iliac lymph node enlargement (Figure 1). There were no adrenal masses.

He is young for prostate, bladder, or colorectal cancer, but early onset variations of these tumors, along with metastatic testicular cancer, must be considered for the pelvic mass and associated lymphadenopathy. Prostatic masses can be infectious (eg, abscess) or malignant (eg, adenocarcinoma, small cell carcinoma). Additional considerations for abdominopelvic cancer are sarcomas, germ cell tumors, or lymphoma. A low aldosterone-renin ratio coupled with a normal potassium level makes primary aldosteronism unlikely. The normal angiography excludes renovascular hypertension.

His abdominal pain and gastrointestinal symptoms could arise from irritation of the bowel, distension of the right-sided urinary collecting system, or products secreted from the mass (eg, catecholamines). The hyperdynamic precordium, elevated ejection fraction, and murmur may reflect augmented blood flow from a hyperadrenergic state. A unifying diagnosis would be a pheochromocytoma. However, given the normal appearance of the adrenal glands on CT imaging, catecholamines arising from a paraganglioma, a tumor of the autonomic nervous system, is more likely. These tumors often secrete catecholamines and can be metastatic (suggested here by the lymphadenopathy). Functional imaging or biopsy of either the mass or an adjacent lymph node is indicated. However, because of the possibility of a catecholamine-secreting tumor, he should be treated with an alpha-adrenergic receptor antagonist before undergoing a biopsy to prevent unopposed vasoconstriction from catecholamine leakage.

Scrotal ultrasound revealed no evidence of a testicular tumor. Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) was 179 IU/L (normal, 120-240 IU/L) and prostate specific antigen (PSA) was 0.7 ng/mL (normal, <2.5 ng/mL). The patient was given amlodipine and labetalol with improvement of blood pressures to 160s/100s. His creatinine decreased to 1.1 mg/dL. He underwent CT-guided biopsy of a pelvic lymph node. CT of the head without intravenous contrast demonstrated no intracranial abnormalities. His headache resolved with improvement in blood pressure, and he had minimal gastrointestinal symptoms during his hospitalization. No stool studies were sent. A right-sided percutaneous nephrostomy was placed which yielded >15 L of urine from the tube over the next four days.

Upon the first episode of micturition through the urethra four days after percutaneous nephrostomy placement, he experienced severe lightheadedness, diaphoresis, and palpitations. These symptoms prompted him to recall similar episodes following micturition for several months prior to his hospitalization.

It is likely that contraction of the bladder during episodes of urination caused irritation of the pelvic mass, leading to catecholamine secretion. Another explanation for his recurrent lightheadedness would be a neurocardiogenic reflex with micturition (which when it culminates with loss of consciousness is called micturition syncope), but this would not explain his hypertension or bladder mass.

Biochemical tests that were ordered on admission but sent to a reference lab then returned. Plasma metanephrine was 0.2 nmol/L (normal, <0.5 nmol/L) and plasma normetanephrine 34.6 nmol/L (normal, <0.9 nmol/L). His 24-hour urine metanephrine was 72 ug/24 hr (normal, 0-300 ug/24 hr) and normetanephrine 8,511 ug/24 hr (normal, 50-800 ug/24 hr).

The markedly elevated plasma and urine normetanephrine levels confirm a diagnosis of a catecholamine-secreting tumor (paraganglioma). The tissue obtained from the CT-guided lymph node biopsy should be sent for markers of neuroendocrine tumors including chromogranin.

Lymph node biopsy revealed metastatic paraganglioma that was chromogranin A and synaptophysin positive (Figure 2). A fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) scan disclosed skull metastases. He was treated with phenoxybenzamine, amlodipine, and labetalol. Surgical resection of the pelvic mass was discussed, but the patient elected to defer surgery as the location of the primary tumor made it challenging to resect and would have required an ileal conduit.

After the diagnosis was made, the patient’s family recalled that a maternal uncle had been diagnosed with a paraganglioma of the carotid body. Genetic testing of the patient identified a succinate dehydrogenase complex subunit B (SDHB) pathogenic variant and confirmed hereditary paraganglioma syndrome (HPGL). One year after the diagnosis, liver and lung metastases developed. He was treated with lanreotide (somatostatin analogue), capecitabine, and temozolomide, as well as a craniotomy and radiotherapy for palliation of bony metastases. The patient died less than two years after diagnosis.

DISCUSSION

Most patients with hypertension (defined as blood pressure >130/80 mm Hg1) do not have an identifiable etiology (primary hypertension). Many components of this patient’s history, however, including his young age of onset, a teenage sibling with hypertension, lack of obesity, hypertension refractory to multiple medications, and LVH suggested secondary hypertension. Hypertension onset at an age less than 30 years, resistance to three or more medications,1,2 and/or acute onset hypertension at any age should prompt an evaluation for secondary causes.1 The prevalence of secondary hypertension is approximately 30% in hypertensive patients ages 18 to 40 years compared with 5%-10% in the overall adult population with hypertension.3 Among children and adolescents ages 0 to 19 years with hypertension, the prevalence of secondary hypertension may be as high as 57%.4

The most common etiology of secondary hypertension is primary aldosteronism.5,6 However, in young adults (ages 19 to 39 years), common etiologies also include renovascular disease and renal parenchymal disease.7 Other causes include obstructive sleep apnea, medications, stimulants (cocaine and amphetamines),8 and endocrinopathies such as thyrotoxicosis, Cushing syndrome, and catecholamine-secreting tumors.7 Less than 1% of secondary hypertension in all adults is due to catecholamine-secreting tumors, and the minority of those catecholamine-secreting tumors are paragangliomas.9

Paragangliomas are tumors of the peripheral autonomic nervous system. These neoplasms arise in the sympathetic and parasympathetic chains along the paravertebral and paraaortic axes. They are closely related to pheochromocytomas, which arise in the adrenal medulla.9 Most head and neck paragangliomas are biochemically silent and are generally discovered due to mass effect.10 The subset of paragangliomas that secrete catecholamines most often arise in the abdomen and pelvis, and their clinical presentation mimics that of pheochromocytomas, including episodic hypertension, palpitations, pallor, and diaphoresis.

This patient had persistent, nonepisodic hypertension, while palpitations and diaphoresis only manifested following micturition. Other cases of urinary bladder paragangliomas have described micturition-associated symptoms and hypertensive crises. Three-fold increases of catecholamine secretion after micturition have been observed in these patients, likely due to muscle contraction and pressure changes in the bladder leading to the systemic release of catecholamines.11

Epinephrine and norepinephrine are monoamine neurotransmitters that activate alpha-adrenergic and beta-adrenergic receptors. Adrenergic receptors are present in all tissues of the body but have prominent effects on the smooth muscle in the vasculature, gastrointestinal tract, urinary tract, and airways.12 Alpha-adrenergic vasoconstriction causes hypertension, which is commonly observed in patients with catecholamine-secreting tumors.10 Catecholamine excess due to secretion from these tumors causes headache in 60%-80% of patients, tachycardia/palpitations in 50%-70%, anxiety in 20%-40%, and nausea in 20%-25%.10 Other symptoms include sweating, pallor, dyspnea, and vertigo.9,10 This patient’s chronic nausea, which was attributed to gastroesophageal reflux, and his anxiety, attributed to generalized anxiety disorder, were likely symptoms of catecholamine excess.13

The best test for the diagnosis of paragangliomas and pheochromocytomas is the measurement of plasma free or 24-hour urinary fractionated metanephrines (test sensitivity of >90% and >90%, respectively).14 Screening for pheochromocytoma should be considered in hypertensive patients who have symptoms of catecholamine excess, refractory or paroxysmal hypertension, and/or familial pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma syndromes.15 Screening for pheochromocytoma should also be performed in children and adolescents with systolic or diastolic blood pressure that is greater than the 95th percentile for their age plus 5 mm Hg.16

While a typical tumor location and elevated metanephrine levels are sufficient to make the diagnosis of a pheochromocytoma or catecholamine-secreting paraganglioma, functional imaging with FDG-PET, Ga-DOTATATE-PET, or 123I-meta-iodobenzylguanidine (123I-MIBG) can further confirm the diagnosis and detect distant metastases. However, imaging has low sensitivity for these tumors and thus should only be considered for patients in whom metastatic disease is suspected.14 Biopsy is rarely needed and should be reserved for unusual metastatic locations. Treatment with an alpha-adrenergic receptor antagonist often reduces symptoms and lowers blood pressure. Definitive management typically involves surgical resection for benign disease. Surgery, radionuclide therapy, or chemotherapy is used for malignant disease.

While most pheochromocytomas are sporadic, up to 40% of paragangliomas are due to germline pathogenic variants.17 Mutations in the succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) group of genes are the most common germline pathogenic variants in the autosomal dominant hereditary paraganglioma syndrome (HPGL). Most paragangliomas and pheochromocytomas are localized and benign, but 10%-15% are metastatic.18 SDHB mutations are associated with a high risk of metastasis.19 Thus, genetic testing for patients and subsequent cascade testing to identify at-risk family members is advised in all patients with pheochromocytomas or paragangliomas.20 This patient’s younger brother and mother were both found to carry the same pathogenic SDHB variant, but neither was found to have paragangliomas. Annual metanephrine levels (urine or plasma) and every other year whole-body magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans were recommended for tumor surveillance.

The clinician team followed a logical branching algorithm for the diagnosis of severe hypertension with biochemical testing, advanced imaging, histology, and genetic testing to arrive at the final diagnosis of hereditary paraganglioma syndrome. Although this patient presented for urgent care because of the acute effects of catecholamine excess, he suffered from chronic effects (nausea, anxiety, and hypertension) for years. Each symptom had been diagnosed and treated in isolation, but the combination and severity in a young patient suggested a unifying diagnosis. The family history of hypertension (brother and father) suggested an inherited diagnosis from the father’s family, but the final answer rested on the other branch (maternal uncle) of the family tree.

KEY TEACHING POINTS

- Hypertension in a young adult is due to a secondary cause in up to 30% of patients.

- Pathologic catecholamine excess leads to hypertension, tachycardia, pallor, sweating, anxiety, and nausea. A sustained and unexplained combination of these symptoms should prompt a biochemical evaluation for pheochromocytoma or paraganglioma.

- Paragangliomas are tumors of the autonomic nervous system. The frequency of catecholamine secretion depends on their location in the body, and they are commonly caused by germline pathogenic variants.

Acknowledgments

This conundrum was presented during a live Grand Rounds with the expert clinician’s responses recorded and edited for space and clarity.

Disclosures

Dr. Dhaliwal reports speaking honoraria from ISMIE Mutual Insurance Company and GE Healthcare. All other authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

No sources of funding.

A 21-year-old man with a history of hypertension presented to the emergency department with four days of generalized abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting as well as one month of loose stools. He also had a headache (not further specified) for one day. Due to his nausea, he had been unable to take his medications for two days. Home blood pressure measurements over the preceding two days revealed systolic pressures exceeding 200 mm Hg. He did not experience fever, dyspnea, chest pain, vision changes, numbness, weakness, diaphoresis, or palpitations.

Abdominal pain with vomiting and diarrhea is often caused by a self-limited gastroenteritis. However, the priority initially is to exclude serious intraabdominal processes including arterial insufficiency, bowel obstruction, organ perforation, or organ-based infection or inflammation (eg, appendicitis, cholecystitis, pancreatitis). Essential hypertension accounts for 95% of cases of hypertension in the United States, but given this patient’s young age, secondary causes should be evaluated. These include primary aldosteronism (the most common endocrine cause for hypertension in young patients), chronic kidney disease, fibromuscular dysplasia, illicit drug use, hypercortisolism, pheochromocytoma, and coarctation of the aorta. Thyrotoxicosis can elevate blood pressure (although usually not to this extent) and cause hyperdefecation. While the etiology of the chronic hypertension is uncertain, the proximate cause of the acute rise in blood pressure is likely the stress of his acute illness and the inability to take his prescribed antihypertensive medications. In the setting of severe hypertension, his headache may reflect an intracranial hemorrhage and his abdominal pain could signal an aortic dissection.

His medical history included hypertension diagnosed at age 16 as well as anxiety diagnosed following a panic attack at age 19. Over the past year, he had also developed persistent nausea, which was attributed to gastroesophageal reflux disease. His medications included metoprolol 50 mg daily, amlodipine 5 mg daily, hydrochlorothiazide 12.5 mg daily, escitalopram 20 mg daily, and omeprazole 20 mg daily. His father and 15-year-old brother also had hypertension. He was a part-time student while working at a car dealership. He did not smoke or use drugs and he rarely drank alcohol.

The need for three antihypertensive medications (albeit at submaximal doses) reflects the severity of his hypertension (provided challenges with medication adherence have been excluded). His family history, especially that of his brother who was diagnosed with hypertension at an early age, and the patient’s own early onset hypertension point toward an inherited form of hypertension. Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease often results in hypertension before chronic kidney disease develops. Rare inherited forms of hypertension include familial hyperaldosteronism, apparent mineralocorticoid excess, Liddle syndrome, or a hereditary endocrine tumor syndrome predisposing to pheochromocytoma. Even among patients who report classic pheochromocytoma symptoms, such as headache and anxiety, the diagnosis remains unlikely as these symptoms are nonspecific and highly prevalent in the general population. However, once secondary hypertension is plausible or suspected, testing for hyperadrenergic states, which can also cause nausea and vomiting during times of catecholamine excess, should be pursued.

His temperature was 97.5°F, heart rate 95 beats per minute and regular, respiratory rate 18 breaths per minute, blood pressure 181/118 mm Hg (systolic and diastolic pressures in each arm were within 10 mm Hg), and oxygen saturation 100% on room air. Systolic and diastolic pressures did not decrease by more than 20 mm Hg and 10 mm Hg, respectively, after he stood for two minutes. His body mass index was 24 kg/m2. He was alert and appeared slightly anxious. There was a bounding point of maximal impulse in the fifth intercostal space at the midclavicular line and a 3/6 systolic murmur at the left upper sternal border with radiation to the carotid arteries. His abdomen was soft with generalized tenderness to palpation and without rebound tenderness, masses, organomegaly, or bruits. There was no costovertebral angle tenderness. No lymphadenopathy was present. His fundoscopic, pulmonary, skin and neurologic examinations were normal.

Laboratory studies revealed a white blood cell count of 13.3 × 103/uL with a normal differential, hemoglobin 13.9 g/dL, platelet count 373 × 103/uL, sodium 142 mmol/L, potassium 3.8 mmol/L, chloride 103 mmol/L,bicarbonate 25 mmol/L, blood urea nitrogen 12 mg/dL, creatinine 1.3 mg/dL (a baseline creatinine level was not available), glucose 88 mg/dL, calcium 10.6 mg/dL, albumin 4.9 g/dL, aspartate aminotransferase 27 IU/L, alanine aminotransferase 37 IU/L, and lipase 40 IU/L. Urinalysis revealed 5-10 white blood cells per high power field without casts and 10 mg/dL protein. Urine toxicology was not performed. Electrocardiogram (ECG) showed left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH). Chest radiography was normal.

The abdominal examination does not suggest peritonitis. The laboratory tests do not suggest inflammation of the liver, pancreas, or biliary tree as the cause of his abdominal pain or diarrhea. The murmur may indicate hypertrophic cardiomyopathy or a congenital anomaly such as bicuspid aortic valve; but neither would explain hypertension unless they were associated with another developmental abnormality, such as coarctation of the aorta. Tricuspid regurgitation is conceivable and if confirmed, might raise concern for carcinoid syndrome, which can cause diarrhea. The normal neurologic examination, including the absence of papilledema, lowers suspicion of intracranial hemorrhage as a cause of his headache.

The albumin of 4.9 g/dL likely reflects hypovolemia resulting from vomiting and diarrhea. Vasoconstriction associated with pheochromocytoma can cause pressure diuresis and resultant hypovolemia. Hyperaldosteronism arising from bilateral adrenal hyperplasia or adrenal adenoma commonly causes hypokalemia, although this is not a universal feature.

The duration of his mildly decreased glomerular filtration rate is uncertain. He may have chronic kidney disease from sustained hypertension, or acute kidney injury from hypovolemia. The mild pyuria could indicate infection or renal calculi, either of which could account for generalized abdominal pain or could reflect an acute renal injury from acute interstitial nephritis from his proton pump inhibitor or hydrochlorothiazide.

LVH on the ECG indicates longstanding hypertension. The chest radiograph does not reveal clues to the etiology of or sequelae from hypertension. In particular, there is no widened aorta to suggest aortic dissection, no pulmonary edema to indicate heart failure, and no rib notching that points toward aortic coarctation. A transthoracic echocardiogram to assess for valvular and other structural abnormalities is warranted.

Tests for secondary hypertension should be sent, including serum aldosterone and renin levels to assess for primary aldosteronism and plasma or 24-hour urine normetanephrine and metanephrine levels to assess for pheochromocytoma. Biochemical evaluation is the mainstay for endocrine hypertension evaluation and should be followed by imaging if abnormal results are found.

Intact parathyroid hormone (PTH) was 78 pg/mL (normal, 10-65 pg/mL), thyroid stimulating hormone 3.6 mIU/L (normal, 0.30-5.50 mIU/L), and morning cortisol 4.1 ug/dL (normal, >7.0 ug/dL). Plasma aldosterone was 14.6 ng/dL (normal, 1-16 ng/dL), plasma renin activity 3.6 ng/mL/hr (normal, 0.5-3.5 ng/mL/hr), and aldosterone-renin ratio 4.1 (normal, <20). Transthoracic echocardiogram showed LVH with normal valves, wall motion, and proximal aorta; the left ventricular ejection fraction was 70%. Magnetic resonance angiography of the renal vessels demonstrated no abnormalities.

Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis with oral and intravenous contrast revealed a 5 cm heterogeneous enhancing mass associated with the prostate gland extending into the base of the bladder. The mass obstructed the right renal collecting system and ureter causing severe right-sided ureterectasis and hydronephrosis. There was also 2.8 cm right-sided paracaval lymph node enlargement and 2.1 cm right-sided and 1.5 cm left-sided external iliac lymph node enlargement (Figure 1). There were no adrenal masses.

He is young for prostate, bladder, or colorectal cancer, but early onset variations of these tumors, along with metastatic testicular cancer, must be considered for the pelvic mass and associated lymphadenopathy. Prostatic masses can be infectious (eg, abscess) or malignant (eg, adenocarcinoma, small cell carcinoma). Additional considerations for abdominopelvic cancer are sarcomas, germ cell tumors, or lymphoma. A low aldosterone-renin ratio coupled with a normal potassium level makes primary aldosteronism unlikely. The normal angiography excludes renovascular hypertension.

His abdominal pain and gastrointestinal symptoms could arise from irritation of the bowel, distension of the right-sided urinary collecting system, or products secreted from the mass (eg, catecholamines). The hyperdynamic precordium, elevated ejection fraction, and murmur may reflect augmented blood flow from a hyperadrenergic state. A unifying diagnosis would be a pheochromocytoma. However, given the normal appearance of the adrenal glands on CT imaging, catecholamines arising from a paraganglioma, a tumor of the autonomic nervous system, is more likely. These tumors often secrete catecholamines and can be metastatic (suggested here by the lymphadenopathy). Functional imaging or biopsy of either the mass or an adjacent lymph node is indicated. However, because of the possibility of a catecholamine-secreting tumor, he should be treated with an alpha-adrenergic receptor antagonist before undergoing a biopsy to prevent unopposed vasoconstriction from catecholamine leakage.

Scrotal ultrasound revealed no evidence of a testicular tumor. Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) was 179 IU/L (normal, 120-240 IU/L) and prostate specific antigen (PSA) was 0.7 ng/mL (normal, <2.5 ng/mL). The patient was given amlodipine and labetalol with improvement of blood pressures to 160s/100s. His creatinine decreased to 1.1 mg/dL. He underwent CT-guided biopsy of a pelvic lymph node. CT of the head without intravenous contrast demonstrated no intracranial abnormalities. His headache resolved with improvement in blood pressure, and he had minimal gastrointestinal symptoms during his hospitalization. No stool studies were sent. A right-sided percutaneous nephrostomy was placed which yielded >15 L of urine from the tube over the next four days.

Upon the first episode of micturition through the urethra four days after percutaneous nephrostomy placement, he experienced severe lightheadedness, diaphoresis, and palpitations. These symptoms prompted him to recall similar episodes following micturition for several months prior to his hospitalization.

It is likely that contraction of the bladder during episodes of urination caused irritation of the pelvic mass, leading to catecholamine secretion. Another explanation for his recurrent lightheadedness would be a neurocardiogenic reflex with micturition (which when it culminates with loss of consciousness is called micturition syncope), but this would not explain his hypertension or bladder mass.

Biochemical tests that were ordered on admission but sent to a reference lab then returned. Plasma metanephrine was 0.2 nmol/L (normal, <0.5 nmol/L) and plasma normetanephrine 34.6 nmol/L (normal, <0.9 nmol/L). His 24-hour urine metanephrine was 72 ug/24 hr (normal, 0-300 ug/24 hr) and normetanephrine 8,511 ug/24 hr (normal, 50-800 ug/24 hr).

The markedly elevated plasma and urine normetanephrine levels confirm a diagnosis of a catecholamine-secreting tumor (paraganglioma). The tissue obtained from the CT-guided lymph node biopsy should be sent for markers of neuroendocrine tumors including chromogranin.

Lymph node biopsy revealed metastatic paraganglioma that was chromogranin A and synaptophysin positive (Figure 2). A fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) scan disclosed skull metastases. He was treated with phenoxybenzamine, amlodipine, and labetalol. Surgical resection of the pelvic mass was discussed, but the patient elected to defer surgery as the location of the primary tumor made it challenging to resect and would have required an ileal conduit.

After the diagnosis was made, the patient’s family recalled that a maternal uncle had been diagnosed with a paraganglioma of the carotid body. Genetic testing of the patient identified a succinate dehydrogenase complex subunit B (SDHB) pathogenic variant and confirmed hereditary paraganglioma syndrome (HPGL). One year after the diagnosis, liver and lung metastases developed. He was treated with lanreotide (somatostatin analogue), capecitabine, and temozolomide, as well as a craniotomy and radiotherapy for palliation of bony metastases. The patient died less than two years after diagnosis.

DISCUSSION

Most patients with hypertension (defined as blood pressure >130/80 mm Hg1) do not have an identifiable etiology (primary hypertension). Many components of this patient’s history, however, including his young age of onset, a teenage sibling with hypertension, lack of obesity, hypertension refractory to multiple medications, and LVH suggested secondary hypertension. Hypertension onset at an age less than 30 years, resistance to three or more medications,1,2 and/or acute onset hypertension at any age should prompt an evaluation for secondary causes.1 The prevalence of secondary hypertension is approximately 30% in hypertensive patients ages 18 to 40 years compared with 5%-10% in the overall adult population with hypertension.3 Among children and adolescents ages 0 to 19 years with hypertension, the prevalence of secondary hypertension may be as high as 57%.4

The most common etiology of secondary hypertension is primary aldosteronism.5,6 However, in young adults (ages 19 to 39 years), common etiologies also include renovascular disease and renal parenchymal disease.7 Other causes include obstructive sleep apnea, medications, stimulants (cocaine and amphetamines),8 and endocrinopathies such as thyrotoxicosis, Cushing syndrome, and catecholamine-secreting tumors.7 Less than 1% of secondary hypertension in all adults is due to catecholamine-secreting tumors, and the minority of those catecholamine-secreting tumors are paragangliomas.9

Paragangliomas are tumors of the peripheral autonomic nervous system. These neoplasms arise in the sympathetic and parasympathetic chains along the paravertebral and paraaortic axes. They are closely related to pheochromocytomas, which arise in the adrenal medulla.9 Most head and neck paragangliomas are biochemically silent and are generally discovered due to mass effect.10 The subset of paragangliomas that secrete catecholamines most often arise in the abdomen and pelvis, and their clinical presentation mimics that of pheochromocytomas, including episodic hypertension, palpitations, pallor, and diaphoresis.

This patient had persistent, nonepisodic hypertension, while palpitations and diaphoresis only manifested following micturition. Other cases of urinary bladder paragangliomas have described micturition-associated symptoms and hypertensive crises. Three-fold increases of catecholamine secretion after micturition have been observed in these patients, likely due to muscle contraction and pressure changes in the bladder leading to the systemic release of catecholamines.11

Epinephrine and norepinephrine are monoamine neurotransmitters that activate alpha-adrenergic and beta-adrenergic receptors. Adrenergic receptors are present in all tissues of the body but have prominent effects on the smooth muscle in the vasculature, gastrointestinal tract, urinary tract, and airways.12 Alpha-adrenergic vasoconstriction causes hypertension, which is commonly observed in patients with catecholamine-secreting tumors.10 Catecholamine excess due to secretion from these tumors causes headache in 60%-80% of patients, tachycardia/palpitations in 50%-70%, anxiety in 20%-40%, and nausea in 20%-25%.10 Other symptoms include sweating, pallor, dyspnea, and vertigo.9,10 This patient’s chronic nausea, which was attributed to gastroesophageal reflux, and his anxiety, attributed to generalized anxiety disorder, were likely symptoms of catecholamine excess.13

The best test for the diagnosis of paragangliomas and pheochromocytomas is the measurement of plasma free or 24-hour urinary fractionated metanephrines (test sensitivity of >90% and >90%, respectively).14 Screening for pheochromocytoma should be considered in hypertensive patients who have symptoms of catecholamine excess, refractory or paroxysmal hypertension, and/or familial pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma syndromes.15 Screening for pheochromocytoma should also be performed in children and adolescents with systolic or diastolic blood pressure that is greater than the 95th percentile for their age plus 5 mm Hg.16

While a typical tumor location and elevated metanephrine levels are sufficient to make the diagnosis of a pheochromocytoma or catecholamine-secreting paraganglioma, functional imaging with FDG-PET, Ga-DOTATATE-PET, or 123I-meta-iodobenzylguanidine (123I-MIBG) can further confirm the diagnosis and detect distant metastases. However, imaging has low sensitivity for these tumors and thus should only be considered for patients in whom metastatic disease is suspected.14 Biopsy is rarely needed and should be reserved for unusual metastatic locations. Treatment with an alpha-adrenergic receptor antagonist often reduces symptoms and lowers blood pressure. Definitive management typically involves surgical resection for benign disease. Surgery, radionuclide therapy, or chemotherapy is used for malignant disease.

While most pheochromocytomas are sporadic, up to 40% of paragangliomas are due to germline pathogenic variants.17 Mutations in the succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) group of genes are the most common germline pathogenic variants in the autosomal dominant hereditary paraganglioma syndrome (HPGL). Most paragangliomas and pheochromocytomas are localized and benign, but 10%-15% are metastatic.18 SDHB mutations are associated with a high risk of metastasis.19 Thus, genetic testing for patients and subsequent cascade testing to identify at-risk family members is advised in all patients with pheochromocytomas or paragangliomas.20 This patient’s younger brother and mother were both found to carry the same pathogenic SDHB variant, but neither was found to have paragangliomas. Annual metanephrine levels (urine or plasma) and every other year whole-body magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans were recommended for tumor surveillance.

The clinician team followed a logical branching algorithm for the diagnosis of severe hypertension with biochemical testing, advanced imaging, histology, and genetic testing to arrive at the final diagnosis of hereditary paraganglioma syndrome. Although this patient presented for urgent care because of the acute effects of catecholamine excess, he suffered from chronic effects (nausea, anxiety, and hypertension) for years. Each symptom had been diagnosed and treated in isolation, but the combination and severity in a young patient suggested a unifying diagnosis. The family history of hypertension (brother and father) suggested an inherited diagnosis from the father’s family, but the final answer rested on the other branch (maternal uncle) of the family tree.

KEY TEACHING POINTS

- Hypertension in a young adult is due to a secondary cause in up to 30% of patients.

- Pathologic catecholamine excess leads to hypertension, tachycardia, pallor, sweating, anxiety, and nausea. A sustained and unexplained combination of these symptoms should prompt a biochemical evaluation for pheochromocytoma or paraganglioma.

- Paragangliomas are tumors of the autonomic nervous system. The frequency of catecholamine secretion depends on their location in the body, and they are commonly caused by germline pathogenic variants.

Acknowledgments

This conundrum was presented during a live Grand Rounds with the expert clinician’s responses recorded and edited for space and clarity.

Disclosures

Dr. Dhaliwal reports speaking honoraria from ISMIE Mutual Insurance Company and GE Healthcare. All other authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

No sources of funding.

1. Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension. 2018;71(6):e13-e115. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYP.0000000000000065.

2. Acelajado MC, Calhoun DA. Resistant hypertension, secondary hypertension, and hypertensive crises: diagnostic evaluation and treatment. Cardiol Clin. 2010;28(4):639-654. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccl.2010.07.002.

3. Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure. Hypertension. 2003;42(6):1206-1252. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.HYP.0000107251.49515.c2.

4. Gupta-Malhotra M, Banker A, Shete S, et al. Essential hypertension vs. secondary hypertension among children. Am J Hypertens. 2015;28(1):73-80. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajh/hpu083.

5. Mosso L, Carvajal C, Gonzalez A, et al. Primary aldosteronism and hypertensive disease. Hypertension. 2003;42(2):161-165. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.HYP.0000079505.25750.11.

6. Kayser SC, Dekkers T, Groenewoud HJ, et al. Study heterogeneity and estimation of prevalence of primary aldosteronism: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;101(7):2826-2835. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2016-1472.

7. Charles L, Triscott J, Dobbs B. Secondary hypertension: discovering the underlying cause. Am Fam Physician. 2017;96(7):453-461.

8. Aronow WS. Drug-induced causes of secondary hypertension. Ann Transl Med. 2017;5(17):349. https://doi.org/10.21037/atm.2017.06.16.

9. Lenders JW, Eisenhofer G, Mannelli M, Pacak K. Phaeochromocytoma. Lancet. 2005;366(9486):665-675. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67139-5.

10. Mannelli M, Lenders JW, Pacak K, Parenti G, Eisenhofer G. Subclinical phaeochromocytoma. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;26(4):507-515. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beem.2011.10.008.

11. Kappers MH, van den Meiracker AH, Alwani RA, Kats E, Baggen MG. Paraganglioma of the urinary bladder. Neth J Med. 2008;66(4):163-165.

12. Paravati S, Warrington SJ. Physiology, Catecholamines. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing LLC; 2019.

13. King KS, Darmani NA, Hughes MS, Adams KT, Pacak K. Exercise-induced nausea and vomiting: another sign and symptom of pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Endocrine. 2010;37(3):403-407. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12020-010-9319-3.

14. Lenders JW, Duh QY, Eisenhofer G, et al. Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(6):1915-1942. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2014-1498.

15. Lenders JWM, Eisenhofer G. Update on modern management of pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul). 2017;32(2):152-161. https://doi.org/10.3803/EnM.2017.32.2.152.

16. National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group. The fourth report on the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2004;114(2):555-576.

17. Else T, Greenberg S, Fishbein L. Hereditary Paraganglioma-Pheochromocytoma Syndromes. In: Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, et al., eds. Gene Reviews. Seattle, WA: University of Washington; 1993.

18. Goldstein RE, O’Neill JA, Jr., Holcomb GW, 3rd, et al. Clinical experience over 48 years with pheochromocytoma. Ann Surg. 1999;229(6):755-764; discussion 764-756. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000658-199906000-00001.

19. Amar L, Baudin E, Burnichon N, et al. Succinate dehydrogenase B gene mutations predict survival in patients with malignant pheochromocytomas or paragangliomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92(10):3822-3828. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2007-0709.

20. Favier J, Amar L, Gimenez-Roqueplo AP. Paraganglioma and phaeochromocytoma: from genetics to personalized medicine. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2015;11(2):101-111. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrendo.2014.188.

1. Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension. 2018;71(6):e13-e115. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYP.0000000000000065.

2. Acelajado MC, Calhoun DA. Resistant hypertension, secondary hypertension, and hypertensive crises: diagnostic evaluation and treatment. Cardiol Clin. 2010;28(4):639-654. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccl.2010.07.002.

3. Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure. Hypertension. 2003;42(6):1206-1252. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.HYP.0000107251.49515.c2.

4. Gupta-Malhotra M, Banker A, Shete S, et al. Essential hypertension vs. secondary hypertension among children. Am J Hypertens. 2015;28(1):73-80. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajh/hpu083.

5. Mosso L, Carvajal C, Gonzalez A, et al. Primary aldosteronism and hypertensive disease. Hypertension. 2003;42(2):161-165. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.HYP.0000079505.25750.11.

6. Kayser SC, Dekkers T, Groenewoud HJ, et al. Study heterogeneity and estimation of prevalence of primary aldosteronism: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;101(7):2826-2835. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2016-1472.

7. Charles L, Triscott J, Dobbs B. Secondary hypertension: discovering the underlying cause. Am Fam Physician. 2017;96(7):453-461.

8. Aronow WS. Drug-induced causes of secondary hypertension. Ann Transl Med. 2017;5(17):349. https://doi.org/10.21037/atm.2017.06.16.

9. Lenders JW, Eisenhofer G, Mannelli M, Pacak K. Phaeochromocytoma. Lancet. 2005;366(9486):665-675. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67139-5.

10. Mannelli M, Lenders JW, Pacak K, Parenti G, Eisenhofer G. Subclinical phaeochromocytoma. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;26(4):507-515. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beem.2011.10.008.

11. Kappers MH, van den Meiracker AH, Alwani RA, Kats E, Baggen MG. Paraganglioma of the urinary bladder. Neth J Med. 2008;66(4):163-165.

12. Paravati S, Warrington SJ. Physiology, Catecholamines. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing LLC; 2019.

13. King KS, Darmani NA, Hughes MS, Adams KT, Pacak K. Exercise-induced nausea and vomiting: another sign and symptom of pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Endocrine. 2010;37(3):403-407. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12020-010-9319-3.

14. Lenders JW, Duh QY, Eisenhofer G, et al. Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(6):1915-1942. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2014-1498.

15. Lenders JWM, Eisenhofer G. Update on modern management of pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul). 2017;32(2):152-161. https://doi.org/10.3803/EnM.2017.32.2.152.

16. National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group. The fourth report on the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2004;114(2):555-576.

17. Else T, Greenberg S, Fishbein L. Hereditary Paraganglioma-Pheochromocytoma Syndromes. In: Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, et al., eds. Gene Reviews. Seattle, WA: University of Washington; 1993.

18. Goldstein RE, O’Neill JA, Jr., Holcomb GW, 3rd, et al. Clinical experience over 48 years with pheochromocytoma. Ann Surg. 1999;229(6):755-764; discussion 764-756. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000658-199906000-00001.

19. Amar L, Baudin E, Burnichon N, et al. Succinate dehydrogenase B gene mutations predict survival in patients with malignant pheochromocytomas or paragangliomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92(10):3822-3828. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2007-0709.

20. Favier J, Amar L, Gimenez-Roqueplo AP. Paraganglioma and phaeochromocytoma: from genetics to personalized medicine. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2015;11(2):101-111. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrendo.2014.188.

© 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine

Appraising the Evidence Supporting Choosing Wisely® Recommendations

As healthcare costs rise, physicians and other stakeholders are now seeking innovative and effective ways to reduce the provision of low-value services.1,2 The Choosing Wisely® campaign aims to further this goal by promoting lists of specific procedures, tests, and treatments that providers should avoid in selected clinical settings.3 On February 21, 2013, the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) released 2 Choosing Wisely® lists consisting of adult and pediatric services that are seen as costly to consumers and to the healthcare system, but which are often nonbeneficial or even harmful.4,5 A total of 80 physician and nurse specialty societies have joined in submitting additional lists.

Despite the growing enthusiasm for this effort, questions remain regarding the Choosing Wisely® campaign’s ability to initiate the meaningful de-adoption of low-value services. Specifically, prior efforts to reduce the use of services deemed to be of questionable benefit have met several challenges.2,6 Early analyses of the Choosing Wisely® recommendations reveal similar roadblocks and variable uptakes of several recommendations.7-10 While the reasons for difficulties in achieving de-adoption are broad, one important factor in whether clinicians are willing to follow guideline recommendations from such initiatives as Choosing Wisely®is the extent to which they believe in the underlying evidence.11 The current work seeks to formally evaluate the evidence supporting the Choosing Wisely® recommendations, and to compare the quality of evidence supporting SHM lists to other published Choosing Wisely® lists.

METHODS

Data Sources

Using the online listing of published Choosing Wisely® recommendations, a dataset was generated incorporating all 320 recommendations comprising the 58 lists published through August, 2014; these include both the adult and pediatric hospital medicine lists released by the SHM.4,5,12 Although data collection ended at this point, this represents a majority of all 81 lists and 535 recommendations published through December, 2017. The reviewers (A.J.A., A.G., M.W., T.S.V., M.S., and C.R.C) extracted information about the references cited for each recommendation.

Data Analysis

The reviewers obtained each reference cited by a Choosing Wisely® recommendation and categorized it by evidence strength along the following hierarchy: clinical practice guideline (CPG), primary research, review article, expert opinion, book, or others/unknown. CPGs were used as the highest level of evidence based on standard expectations for methodological rigor.13 Primary research was further rated as follows: systematic reviews and meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials (RCTs), observational studies, and case series. Each recommendation was graded using only the strongest piece of evidence cited.

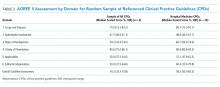

Guideline Appraisal

We further sought to evaluate the strength of referenced CPGs. To accomplish this, a 10% random sample of the Choosing Wisely® recommendations citing CPGs was selected, and the referenced CPGs were obtained. Separately, CPGs referenced by the SHM-published adult and pediatric lists were also obtained. For both groups, one CPG was randomly selected when a recommendation cited more than one CPG. These guidelines were assessed using the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation (AGREE) II instrument, a widely used instrument designed to assess CPG quality.14,15 AGREE II consists of 25 questions categorized into 6 domains: scope and purpose, stakeholder involvement, rigor of development, clarity of presentation, applicability, and editorial independence. Guidelines are also assigned an overall score. Two trained reviewers (A.J.A. and A.G.) assessed each of the sampled CPGs using a standardized form. Scores were then standardized using the method recommended by the instrument and reported as a percentage of available points. Although a standard interpretation of scores is not provided by the instrument, prior applications deemed scores below 50% as deficient16,17. When a recommendation item cited multiple CPGs, one was randomly selected. We also abstracted data on the year of publication, the evidence grade assigned to specific items recommended by Choosing Wisely®, and whether the CPG addressed the referring recommendation. All data management and analysis were conducted using Stata (V14.2, StataCorp, College Station, Texas).

RESULTS