User login

What’s Eating You? Phlebotomine Sandflies and Leishmania Parasites

The genus Leishmania comprises protozoan parasites that cause approximately 2 million new cases of leishmaniasis each year across 98 countries.1 These protozoa are obligate intracellular parasites of phlebotomine sandfly species that transmit leishmaniasis and result in a considerable parasitic cause of fatalities globally, second only to malaria.2,3

Phlebotomine sandflies primarily live in tropical and subtropical regions and function as vectors for many pathogens in addition to Leishmania species, such as Bartonella species and arboviruses.3 In 2004, it was noted that the majority of leishmaniasis cases affected developing countries: 90% of visceral leishmaniasis cases occurred in Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Sudan, and Brazil, and 90% of cutaneous leishmaniasis cases occurred in Afghanistan, Algeria, Brazil, Iran, Peru, Saudi Arabia, and Syria.4 Of note, with recent environmental changes, phlebotomine sandflies have gradually migrated to more northerly latitudes, extending into Europe.5

Twenty Leishmania species and 30 sandfly species have been identified as causes of leishmaniasis.4Leishmania infection occurs when an infected sandfly bites a mammalian host and transmits the parasite’s flagellated form, known as a promastigote. Host inflammatory cells, such as monocytes and dendritic cells, phagocytize parasites that enter the skin. The interaction between parasites and dendritic cells become an important factor in the outcome of Leishmania infection in the host because dendritic cells promote development of CD4 and CD8 T lymphocytes with specificity to target Leishmania parasites and protect the host.1

The number of cases of leishmaniasis has increased worldwide, most likely due to changes in the environment and human behaviors such as urbanization, the creation of new settlements, and migration from rural to urban areas.3,5 Important risk factors in individual patients include malnutrition; low-quality housing and sanitation; a history of migration or travel; and immunosuppression, such as that caused by HIV co-infection.2,5

Case Report

An otherwise healthy 25-year-old Bangladeshi man presented to our community hospital for evaluation of a painful leg ulcer of 1 month’s duration. The patient had migrated from Bangladesh to Panama, then to Costa Rica, followed by Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, and, last, Texas. In Texas, he was identified by the US Immigration and Customs Enforcement, transported to a detention facility, and transferred to this hospital shortly afterward.

The patient reported that, during his extensive migration, he had lived in the jungle and reported what he described as mosquito bites on the legs. He subsequently developed a 3-cm ulcerated and crusted plaque with rolled borders on the right medial ankle (Figure 1). In addition, he had a palpable nodular cord on the medial leg from the ankle lesion to the mid thigh that was consistent with lymphocutaneous spread. Ultrasonography was negative for deep-vein thrombosis.

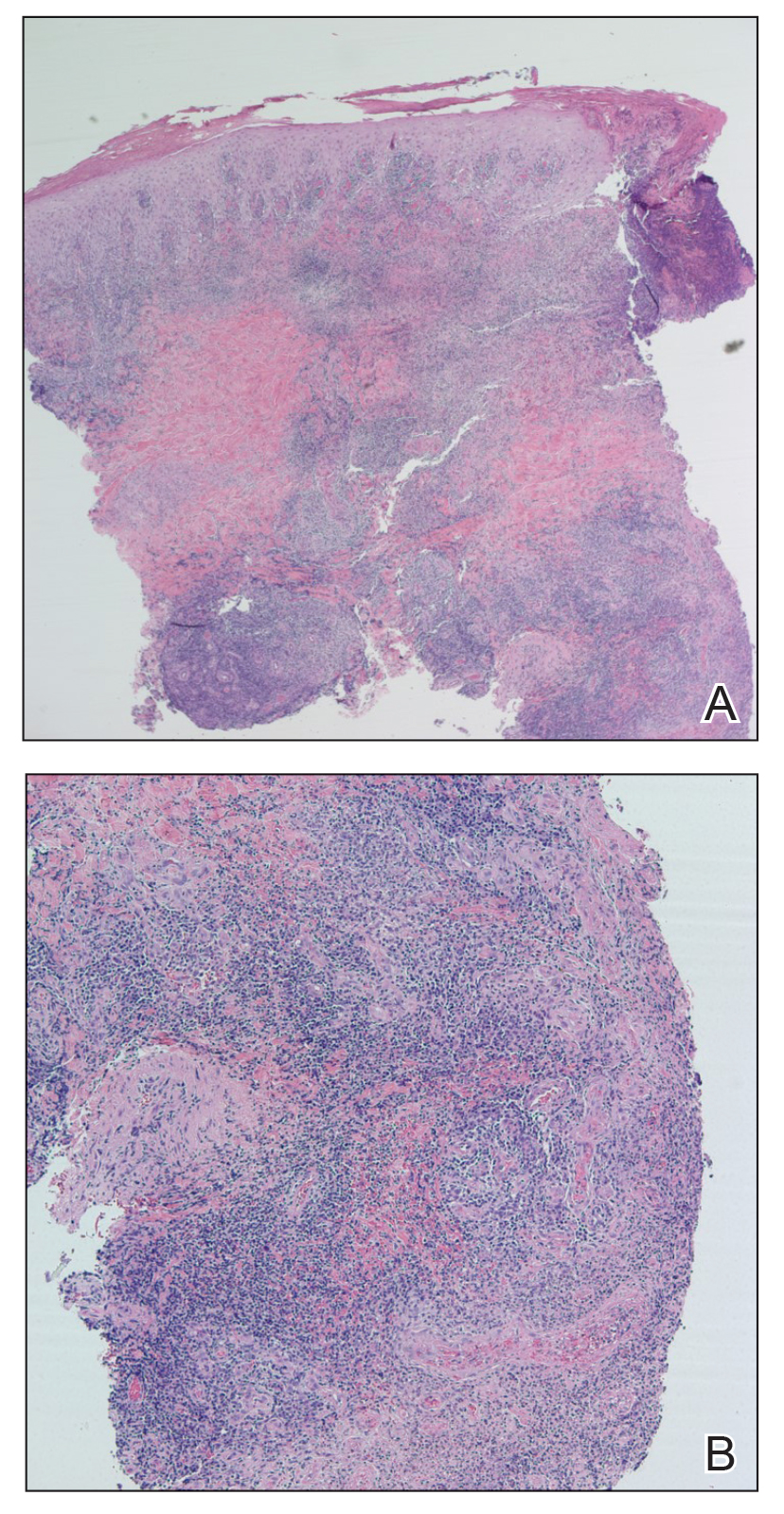

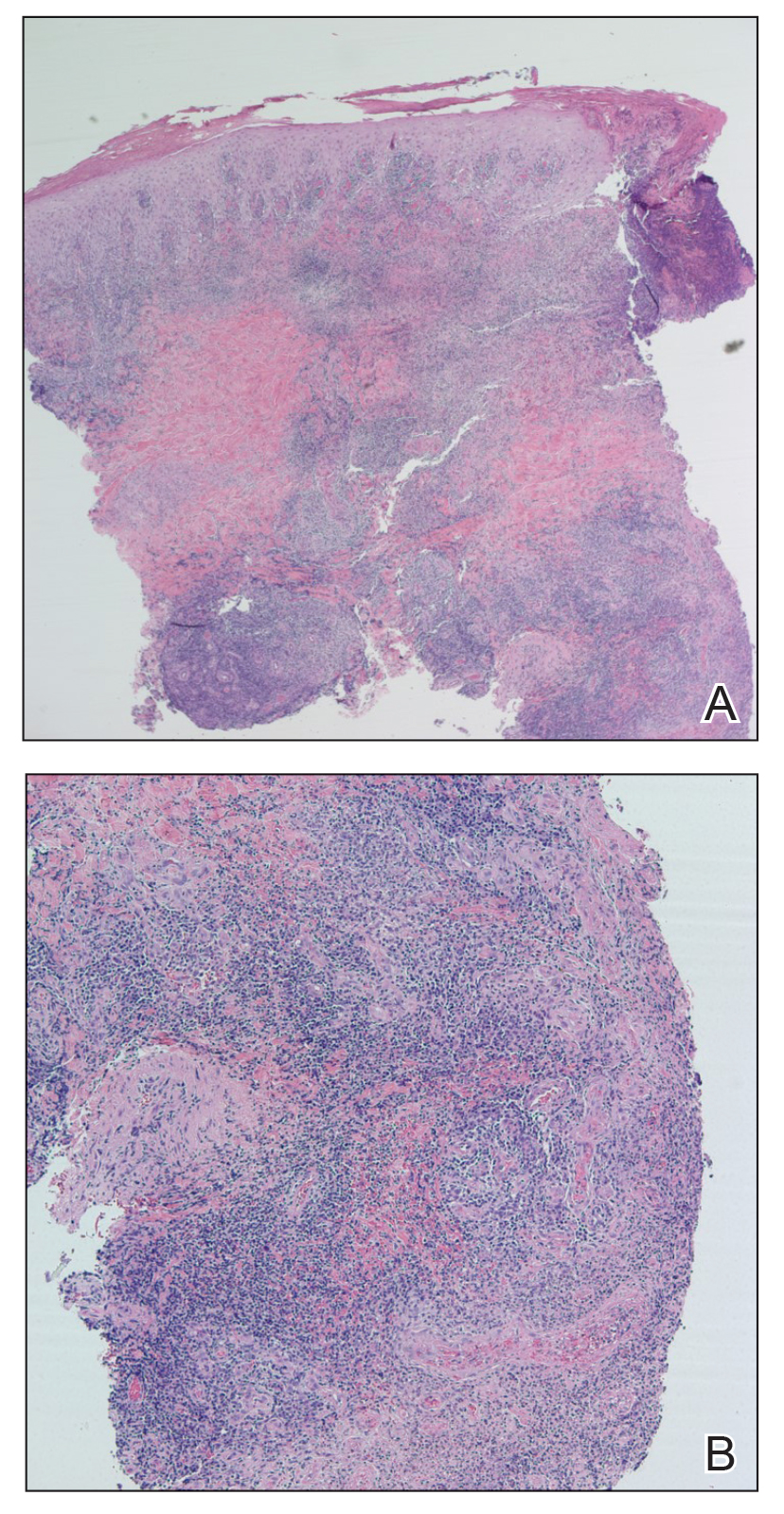

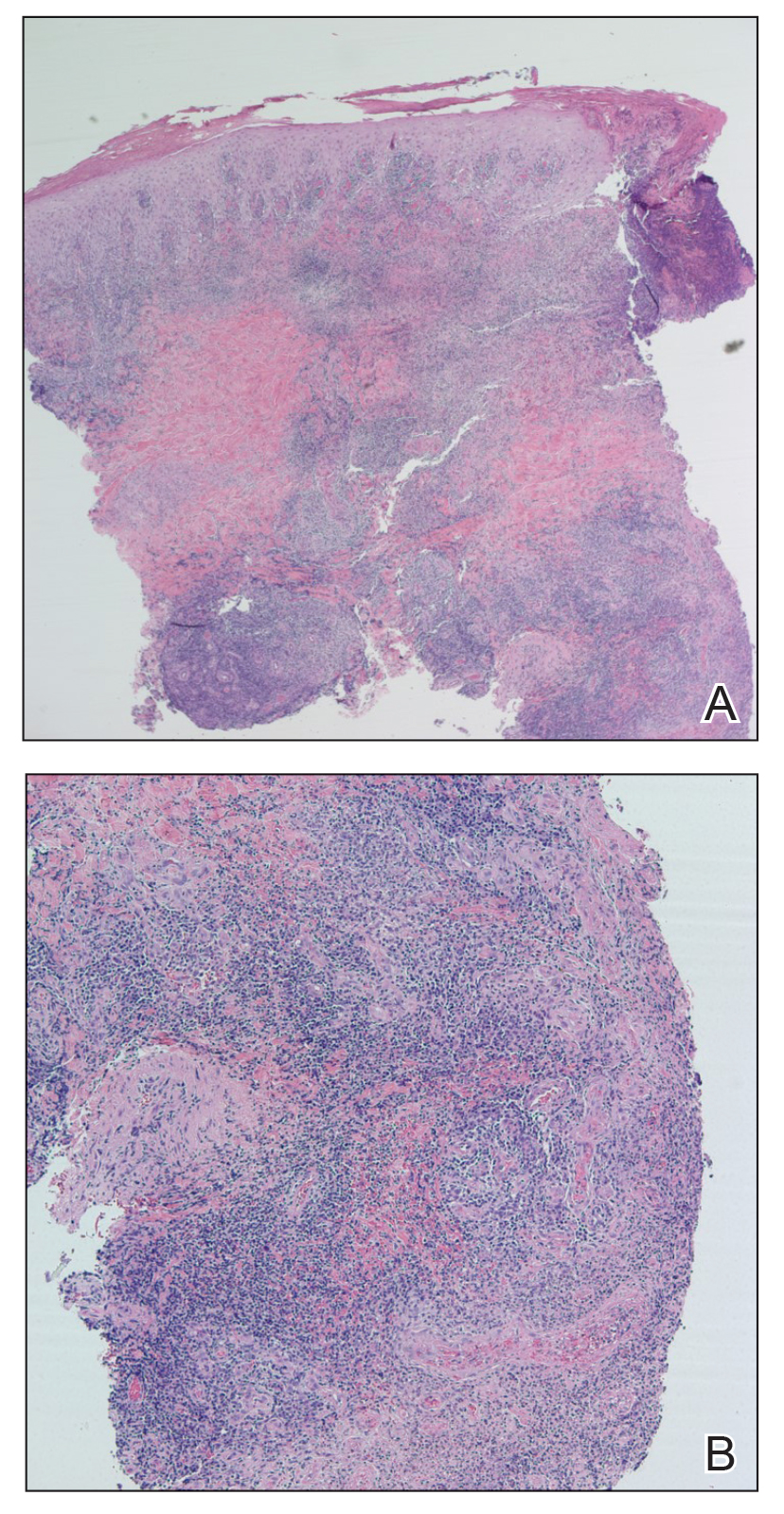

Because the patient’s recent migration from Central America was highly concerning for microbial infection, vancomycin and piperacillin-tazobactam were started empirically on admission. A punch biopsy from the right medial ankle was nondiagnostic, showing acute and chronic necrotizing inflammation along with numerous epithelioid histiocytes with a vaguely granulomatous appearance (Figure 2). A specimen from the right medial ankle that had already been taken by an astute border patrol medical provider was sent to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) for polymerase chain reaction analysis following admission and was found to be positive for Leishmania panamensis.

Given the concern for mucocutaneous leishmaniasis with this particular species, otolaryngology was consulted; however, the patient did not demonstrate mucocutaneous disease. Because of the elevated risk for persistent disease with L panamensis, systemic therapy was indicated and administered: IV amphotericin B 200 mg on days 1 through 5 and again on day 10. Improvement in the ulcer was seen after the 10-day regimen was completed.

Comment

Leishmaniasis can be broadly classified by geographic region or clinical presentation. Under the geographic region system, leishmaniasis can be categorized as Old World or New World. Old World leishmaniasis primarily is transmitted by Phlebotomus sandflies and carries the parasites Leishmania major and Leishmania tropica, among others. New World leishmaniasis is caused by Lutzomyia sandflies, which carry Leishmania mexicana, Leishmania braziliensis, Leishmania amazonensis, and others.6

Our patient presented with cutaneous leishmaniasis, one of 4 primary clinical disease forms of leishmaniasis; the other 3 forms under this classification system are diffuse cutaneous, mucocutaneous, and visceral leishmaniasis, also known as kala-azar.3,6 Cutaneous leishmaniasis is limited to the skin, particularly the face and extremities. This form is more common with Old World vectors, with most cases occurring in Peru, Brazil, and the Middle East. In Old World cutaneous leishmaniasis, the disease begins with a solitary nodule at the site of the bite that ulcerates and can continue to spread in a sporotrichoid pattern. This cutaneous form tends to heal slowly over months to years with residual scarring. New World cutaneous leishmaniasis can present with a variety of clinical manifestations, including ulcerative, sarcoidlike, miliary, and nodular lesions.6,7

The diffuse form of cutaneous leishmaniasis begins in a similar manner to the Old World cutaneous form: a single nodule spreads widely over the body, especially the nose, and covers the patient’s skin with keloidal or verrucous lesions that do not ulcerate. These nodules contain large groupings of Leishmania-filled foamy macrophages. Often, patients with diffuse cutaneous leishmaniasis are immunosuppressed and are unable to develop an immune response to leishmanin and other skin antigens.6,7

Mucocutaneous leishmaniasis predominantly is caused by the New World species L braziliensis but also has been attributed to L amazonensis, L panamensis, and L guyanensis. This form manifests as mucosal lesions that can develop simultaneously with cutaneous lesions but more commonly appear months to years after resolution of the skin infection. Patients often present with ulceration of the lip, nose, and oropharynx, and destruction of the nasopharynx can result in severe consequences such as obstruction of the airway and perforation of the nasal septum (also known as espundia).6,7

The most severe presentation of leishmaniasis is the visceral form (kala-azar), which presents with parasitic infection of the liver, spleen, and bone marrow. Most commonly caused by Leishmania donovani, Leishmania infantum, and Leishmania chagasi, this form has a long incubation period spanning months to years before presenting with diarrhea, hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, darkening of the skin (in Hindi, kala-azar means “black fever”), pancytopenia, lymphadenopathy, nephritis, and intestinal hemorrhage, among other severe manifestations. Visceral leishmaniasis has a poor prognosis: patients succumb to disease within 2 years if not treated.6,7

Diagnosis—Diagnosing leishmaniasis starts with a complete personal and medical history, paying close attention to travel and exposures. Diagnosis is most successfully performed by polymerase chain reaction analysis, which is both highly sensitive and specific but also can be determined by culture using Novy-McNeal-Nicolle medium or by light microscopy. Histologic findings include the marquee sign, which describes an array of amastigotes (promastigotes that have developed into the intracellular tissue-stage form) with kinetoplasts surrounding the periphery of parasitized histiocytes. Giemsa staining can be helpful in identifying organisms.2,6,7

The diagnosis in our case was challenging, as none of the above findings were seen in our patient. The specimen taken by the border patrol medical provider was negative on Gram, Giemsa, and Grocott-Gömöri methenamine silver staining; no amastigotes were identified. Another diagnostic modality (not performed in our patient) is the Montenegro delayed skin-reaction test, which often is positive in patients with cutaneous leishmaniasis but also yields a positive result in patients who have been cured of Leishmania infection.6

An important consideration in the diagnostic workup of leishmaniasis is that collaboration with the CDC can be helpful, such as in our case, as they provide clear guidance for specimen collection and processing.2

Treatment—Treating leishmaniasis is challenging and complex. Even the initial decision to treat depends on several factors, including the form of infection. Most visceral and mucocutaneous infections should be treated due to both the lack of self-resolution of these forms and the higher risk for a potentially life-threatening disease course; in contrast, cutaneous forms require further consideration before initiating treatment. Some indicators for treating cutaneous leishmaniasis include widespread infection, intention to decrease scarring, and lesions with the potential to cause further complications (eg, on the face or ears or close to joints).6-8

The treatment of choice for cutaneous and mucocutaneous leishmaniasis is pentavalent antimony; however, this drug can only be obtained in the United States for investigational use, requiring approval by the CDC. A 20-day intravenous or intramuscular course of 20 mg/kg per day typically is used for cutaneous cases; a 28-day course typically is used for mucosal forms.

Amphotericin B is not only the treatment of choice for visceral leishmaniasis but also is an important alternative therapy for patients with mucosal leishmaniasis or who are co-infected with HIV. Patients with visceral infection also should receive supportive care for any concomitant afflictions, such as malnutrition or other infections. Although different regimens have been described, the US Food and Drug Administration has created outlines of specific intravenous infusion schedules for liposomal amphotericin B in immunocompetent and immunosuppressed patients.8 Liposomal amphotericin B also has a more favorable toxicity profile than conventional amphotericin B deoxycholate, which is otherwise effective in combating visceral leishmaniasis.6-8

Other treatments that have been attempted include pentamidine, miltefosine, thermotherapy, oral itraconazole and fluconazole, rifampicin, metronidazole and cotrimoxazole, dapsone, photodynamic therapy, thermotherapy, topical paromomycin formulations, intralesional pentavalent antimony, and laser cryotherapy. Notable among these other agents is miltefosine, a US Food and Drug Administration–approved oral medication for adults and adolescents (used off-label for patients younger than 12 years) with cutaneous leishmaniasis caused by L braziliensis, L panamensis, or L guyanensis. Other oral options mentioned include the so-called azole antifungal medications, which historically have produced variable results. From the CDC’s reports, ketoconazole was moderately effective in Guatemala and Panama,8 whereas itraconazole did not demonstrate efficacy in Colombia, and the efficacy of fluconazole was inconsistent in different countries.8 When considering one of the local (as opposed to oral and parenteral) therapies mentioned, the extent of cutaneous findings as well as the risk of mucosal spread should be factored in.6-8

Understandably, a number of considerations can come into play in determining the appropriate treatment modality, including body region affected, clinical form, severity, and Leishmania species.6-8 Our case is of particular interest because it demonstrates the complexities behind the diagnosis and treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis, with careful consideration geared toward the species; for example, because our patient was infected with L panamensis, which is known to cause mucocutaneous disease, the infectious disease service decided to pursue systemic therapy with amphotericin B rather than topical treatment.

Prevention—Vector control is the primary means of preventing leishmaniasis under 2 umbrellas: environmental management and synthetic insecticides. The goal of environmental management is to eliminate the phlebotomine sandfly habitat; this was the primary method of vector control until 1940. Until that time, tree stumps were removed, indoor cracks and crevices were filled to prevent sandfly emergence, and areas around animal shelters were cleaned. These methods were highly dependent on community awareness and involvement; today, they can be combined with synthetic insecticides to offer maximum protection.

Synthetic insecticides include indoor sprays, treated nets, repellents, and impregnated dog collars, all of which control sandflies. However, the use of these insecticides in endemic areas, such as India, has driven development of insecticide resistance in many sandfly vector species.3

As of 2020, 5 vaccines against Leishmania have been created. Two are approved–one in Brazil and one in Uzbekistan–for human use as immunotherapy, while the other 3 have been developed to immunize dogs in Brazil. However, the effectiveness of these vaccines is under debate. First, one of the vaccines used as immunotherapy for cutaneous leishmaniasis must be used in combination with conventional chemotherapy; second, long-term effects of the canine vaccine are unknown.1 A preventive vaccine for humans is under development.1,3

Final Thoughts

Leishmaniasis remains a notable parasitic disease that is increasing in prevalence worldwide. Clinicians should be aware of this disease because early detection and treatment are essential to control infection.3 Health care providers in the United States should be especially aware of this condition among patients who have a history of travel or migration; those in Texas should recognize the current endemic status of leishmaniasis there.4,6

- Coutinho De Oliveira B, Duthie MS, Alves Pereira VR. Vaccines for leishmaniasis and the implications of their development for American tegumentary leishmaniasis. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2020;16:919-930. doi:10.1080/21645515.2019.1678998

- Chan CX, Simmons BJ, Call JE, et al. Cutaneous leishmaniasis successfully treated with miltefosine. Cutis. 2020;106:206-209. doi:10.12788/cutis.0086

- Balaska S, Fotakis EA, Chaskopoulou A, et al. Chemical control and insecticide resistance status of sand fly vectors worldwide. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2021;15:E0009586. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0009586

- Desjeux P. Leishmaniasis. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004;2:692. doi:10.1038/nrmicro981

- Michelutti A, Toniolo F, Bertola M, et al. Occurrence of Phlebotomine sand flies (Diptera: Psychodidae) in the northeastern plain of Italy. Parasit Vectors. 2021;14:164. doi:10.1186/s13071-021-04652-2

- Alkihan A, Hocker TLH. Infectious diseases: parasites and other creatures: protozoa. In: Alikhan A, Hocker TLH, eds. Review of Dermatology. Elsevier; 2024:329-331.

- Dinulos JGH. Infestations and bites. In: Habif TP, ed. Clinical Dermatology. Elsevier; 2016:630-634.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Leishmaniasis: resources for health professionals. US Department of Health and Human Services. March 20, 2023. Accessed October 5, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/leishmaniasis/health_professionals/index.html#:~:text=Liposomal%20amphotericin%20B%20is%20FDA,treatment%20of%20choice%20for%20U.S

The genus Leishmania comprises protozoan parasites that cause approximately 2 million new cases of leishmaniasis each year across 98 countries.1 These protozoa are obligate intracellular parasites of phlebotomine sandfly species that transmit leishmaniasis and result in a considerable parasitic cause of fatalities globally, second only to malaria.2,3

Phlebotomine sandflies primarily live in tropical and subtropical regions and function as vectors for many pathogens in addition to Leishmania species, such as Bartonella species and arboviruses.3 In 2004, it was noted that the majority of leishmaniasis cases affected developing countries: 90% of visceral leishmaniasis cases occurred in Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Sudan, and Brazil, and 90% of cutaneous leishmaniasis cases occurred in Afghanistan, Algeria, Brazil, Iran, Peru, Saudi Arabia, and Syria.4 Of note, with recent environmental changes, phlebotomine sandflies have gradually migrated to more northerly latitudes, extending into Europe.5

Twenty Leishmania species and 30 sandfly species have been identified as causes of leishmaniasis.4Leishmania infection occurs when an infected sandfly bites a mammalian host and transmits the parasite’s flagellated form, known as a promastigote. Host inflammatory cells, such as monocytes and dendritic cells, phagocytize parasites that enter the skin. The interaction between parasites and dendritic cells become an important factor in the outcome of Leishmania infection in the host because dendritic cells promote development of CD4 and CD8 T lymphocytes with specificity to target Leishmania parasites and protect the host.1

The number of cases of leishmaniasis has increased worldwide, most likely due to changes in the environment and human behaviors such as urbanization, the creation of new settlements, and migration from rural to urban areas.3,5 Important risk factors in individual patients include malnutrition; low-quality housing and sanitation; a history of migration or travel; and immunosuppression, such as that caused by HIV co-infection.2,5

Case Report

An otherwise healthy 25-year-old Bangladeshi man presented to our community hospital for evaluation of a painful leg ulcer of 1 month’s duration. The patient had migrated from Bangladesh to Panama, then to Costa Rica, followed by Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, and, last, Texas. In Texas, he was identified by the US Immigration and Customs Enforcement, transported to a detention facility, and transferred to this hospital shortly afterward.

The patient reported that, during his extensive migration, he had lived in the jungle and reported what he described as mosquito bites on the legs. He subsequently developed a 3-cm ulcerated and crusted plaque with rolled borders on the right medial ankle (Figure 1). In addition, he had a palpable nodular cord on the medial leg from the ankle lesion to the mid thigh that was consistent with lymphocutaneous spread. Ultrasonography was negative for deep-vein thrombosis.

Because the patient’s recent migration from Central America was highly concerning for microbial infection, vancomycin and piperacillin-tazobactam were started empirically on admission. A punch biopsy from the right medial ankle was nondiagnostic, showing acute and chronic necrotizing inflammation along with numerous epithelioid histiocytes with a vaguely granulomatous appearance (Figure 2). A specimen from the right medial ankle that had already been taken by an astute border patrol medical provider was sent to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) for polymerase chain reaction analysis following admission and was found to be positive for Leishmania panamensis.

Given the concern for mucocutaneous leishmaniasis with this particular species, otolaryngology was consulted; however, the patient did not demonstrate mucocutaneous disease. Because of the elevated risk for persistent disease with L panamensis, systemic therapy was indicated and administered: IV amphotericin B 200 mg on days 1 through 5 and again on day 10. Improvement in the ulcer was seen after the 10-day regimen was completed.

Comment

Leishmaniasis can be broadly classified by geographic region or clinical presentation. Under the geographic region system, leishmaniasis can be categorized as Old World or New World. Old World leishmaniasis primarily is transmitted by Phlebotomus sandflies and carries the parasites Leishmania major and Leishmania tropica, among others. New World leishmaniasis is caused by Lutzomyia sandflies, which carry Leishmania mexicana, Leishmania braziliensis, Leishmania amazonensis, and others.6

Our patient presented with cutaneous leishmaniasis, one of 4 primary clinical disease forms of leishmaniasis; the other 3 forms under this classification system are diffuse cutaneous, mucocutaneous, and visceral leishmaniasis, also known as kala-azar.3,6 Cutaneous leishmaniasis is limited to the skin, particularly the face and extremities. This form is more common with Old World vectors, with most cases occurring in Peru, Brazil, and the Middle East. In Old World cutaneous leishmaniasis, the disease begins with a solitary nodule at the site of the bite that ulcerates and can continue to spread in a sporotrichoid pattern. This cutaneous form tends to heal slowly over months to years with residual scarring. New World cutaneous leishmaniasis can present with a variety of clinical manifestations, including ulcerative, sarcoidlike, miliary, and nodular lesions.6,7

The diffuse form of cutaneous leishmaniasis begins in a similar manner to the Old World cutaneous form: a single nodule spreads widely over the body, especially the nose, and covers the patient’s skin with keloidal or verrucous lesions that do not ulcerate. These nodules contain large groupings of Leishmania-filled foamy macrophages. Often, patients with diffuse cutaneous leishmaniasis are immunosuppressed and are unable to develop an immune response to leishmanin and other skin antigens.6,7

Mucocutaneous leishmaniasis predominantly is caused by the New World species L braziliensis but also has been attributed to L amazonensis, L panamensis, and L guyanensis. This form manifests as mucosal lesions that can develop simultaneously with cutaneous lesions but more commonly appear months to years after resolution of the skin infection. Patients often present with ulceration of the lip, nose, and oropharynx, and destruction of the nasopharynx can result in severe consequences such as obstruction of the airway and perforation of the nasal septum (also known as espundia).6,7

The most severe presentation of leishmaniasis is the visceral form (kala-azar), which presents with parasitic infection of the liver, spleen, and bone marrow. Most commonly caused by Leishmania donovani, Leishmania infantum, and Leishmania chagasi, this form has a long incubation period spanning months to years before presenting with diarrhea, hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, darkening of the skin (in Hindi, kala-azar means “black fever”), pancytopenia, lymphadenopathy, nephritis, and intestinal hemorrhage, among other severe manifestations. Visceral leishmaniasis has a poor prognosis: patients succumb to disease within 2 years if not treated.6,7

Diagnosis—Diagnosing leishmaniasis starts with a complete personal and medical history, paying close attention to travel and exposures. Diagnosis is most successfully performed by polymerase chain reaction analysis, which is both highly sensitive and specific but also can be determined by culture using Novy-McNeal-Nicolle medium or by light microscopy. Histologic findings include the marquee sign, which describes an array of amastigotes (promastigotes that have developed into the intracellular tissue-stage form) with kinetoplasts surrounding the periphery of parasitized histiocytes. Giemsa staining can be helpful in identifying organisms.2,6,7

The diagnosis in our case was challenging, as none of the above findings were seen in our patient. The specimen taken by the border patrol medical provider was negative on Gram, Giemsa, and Grocott-Gömöri methenamine silver staining; no amastigotes were identified. Another diagnostic modality (not performed in our patient) is the Montenegro delayed skin-reaction test, which often is positive in patients with cutaneous leishmaniasis but also yields a positive result in patients who have been cured of Leishmania infection.6

An important consideration in the diagnostic workup of leishmaniasis is that collaboration with the CDC can be helpful, such as in our case, as they provide clear guidance for specimen collection and processing.2

Treatment—Treating leishmaniasis is challenging and complex. Even the initial decision to treat depends on several factors, including the form of infection. Most visceral and mucocutaneous infections should be treated due to both the lack of self-resolution of these forms and the higher risk for a potentially life-threatening disease course; in contrast, cutaneous forms require further consideration before initiating treatment. Some indicators for treating cutaneous leishmaniasis include widespread infection, intention to decrease scarring, and lesions with the potential to cause further complications (eg, on the face or ears or close to joints).6-8

The treatment of choice for cutaneous and mucocutaneous leishmaniasis is pentavalent antimony; however, this drug can only be obtained in the United States for investigational use, requiring approval by the CDC. A 20-day intravenous or intramuscular course of 20 mg/kg per day typically is used for cutaneous cases; a 28-day course typically is used for mucosal forms.

Amphotericin B is not only the treatment of choice for visceral leishmaniasis but also is an important alternative therapy for patients with mucosal leishmaniasis or who are co-infected with HIV. Patients with visceral infection also should receive supportive care for any concomitant afflictions, such as malnutrition or other infections. Although different regimens have been described, the US Food and Drug Administration has created outlines of specific intravenous infusion schedules for liposomal amphotericin B in immunocompetent and immunosuppressed patients.8 Liposomal amphotericin B also has a more favorable toxicity profile than conventional amphotericin B deoxycholate, which is otherwise effective in combating visceral leishmaniasis.6-8

Other treatments that have been attempted include pentamidine, miltefosine, thermotherapy, oral itraconazole and fluconazole, rifampicin, metronidazole and cotrimoxazole, dapsone, photodynamic therapy, thermotherapy, topical paromomycin formulations, intralesional pentavalent antimony, and laser cryotherapy. Notable among these other agents is miltefosine, a US Food and Drug Administration–approved oral medication for adults and adolescents (used off-label for patients younger than 12 years) with cutaneous leishmaniasis caused by L braziliensis, L panamensis, or L guyanensis. Other oral options mentioned include the so-called azole antifungal medications, which historically have produced variable results. From the CDC’s reports, ketoconazole was moderately effective in Guatemala and Panama,8 whereas itraconazole did not demonstrate efficacy in Colombia, and the efficacy of fluconazole was inconsistent in different countries.8 When considering one of the local (as opposed to oral and parenteral) therapies mentioned, the extent of cutaneous findings as well as the risk of mucosal spread should be factored in.6-8

Understandably, a number of considerations can come into play in determining the appropriate treatment modality, including body region affected, clinical form, severity, and Leishmania species.6-8 Our case is of particular interest because it demonstrates the complexities behind the diagnosis and treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis, with careful consideration geared toward the species; for example, because our patient was infected with L panamensis, which is known to cause mucocutaneous disease, the infectious disease service decided to pursue systemic therapy with amphotericin B rather than topical treatment.

Prevention—Vector control is the primary means of preventing leishmaniasis under 2 umbrellas: environmental management and synthetic insecticides. The goal of environmental management is to eliminate the phlebotomine sandfly habitat; this was the primary method of vector control until 1940. Until that time, tree stumps were removed, indoor cracks and crevices were filled to prevent sandfly emergence, and areas around animal shelters were cleaned. These methods were highly dependent on community awareness and involvement; today, they can be combined with synthetic insecticides to offer maximum protection.

Synthetic insecticides include indoor sprays, treated nets, repellents, and impregnated dog collars, all of which control sandflies. However, the use of these insecticides in endemic areas, such as India, has driven development of insecticide resistance in many sandfly vector species.3

As of 2020, 5 vaccines against Leishmania have been created. Two are approved–one in Brazil and one in Uzbekistan–for human use as immunotherapy, while the other 3 have been developed to immunize dogs in Brazil. However, the effectiveness of these vaccines is under debate. First, one of the vaccines used as immunotherapy for cutaneous leishmaniasis must be used in combination with conventional chemotherapy; second, long-term effects of the canine vaccine are unknown.1 A preventive vaccine for humans is under development.1,3

Final Thoughts

Leishmaniasis remains a notable parasitic disease that is increasing in prevalence worldwide. Clinicians should be aware of this disease because early detection and treatment are essential to control infection.3 Health care providers in the United States should be especially aware of this condition among patients who have a history of travel or migration; those in Texas should recognize the current endemic status of leishmaniasis there.4,6

The genus Leishmania comprises protozoan parasites that cause approximately 2 million new cases of leishmaniasis each year across 98 countries.1 These protozoa are obligate intracellular parasites of phlebotomine sandfly species that transmit leishmaniasis and result in a considerable parasitic cause of fatalities globally, second only to malaria.2,3

Phlebotomine sandflies primarily live in tropical and subtropical regions and function as vectors for many pathogens in addition to Leishmania species, such as Bartonella species and arboviruses.3 In 2004, it was noted that the majority of leishmaniasis cases affected developing countries: 90% of visceral leishmaniasis cases occurred in Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Sudan, and Brazil, and 90% of cutaneous leishmaniasis cases occurred in Afghanistan, Algeria, Brazil, Iran, Peru, Saudi Arabia, and Syria.4 Of note, with recent environmental changes, phlebotomine sandflies have gradually migrated to more northerly latitudes, extending into Europe.5

Twenty Leishmania species and 30 sandfly species have been identified as causes of leishmaniasis.4Leishmania infection occurs when an infected sandfly bites a mammalian host and transmits the parasite’s flagellated form, known as a promastigote. Host inflammatory cells, such as monocytes and dendritic cells, phagocytize parasites that enter the skin. The interaction between parasites and dendritic cells become an important factor in the outcome of Leishmania infection in the host because dendritic cells promote development of CD4 and CD8 T lymphocytes with specificity to target Leishmania parasites and protect the host.1

The number of cases of leishmaniasis has increased worldwide, most likely due to changes in the environment and human behaviors such as urbanization, the creation of new settlements, and migration from rural to urban areas.3,5 Important risk factors in individual patients include malnutrition; low-quality housing and sanitation; a history of migration or travel; and immunosuppression, such as that caused by HIV co-infection.2,5

Case Report

An otherwise healthy 25-year-old Bangladeshi man presented to our community hospital for evaluation of a painful leg ulcer of 1 month’s duration. The patient had migrated from Bangladesh to Panama, then to Costa Rica, followed by Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, and, last, Texas. In Texas, he was identified by the US Immigration and Customs Enforcement, transported to a detention facility, and transferred to this hospital shortly afterward.

The patient reported that, during his extensive migration, he had lived in the jungle and reported what he described as mosquito bites on the legs. He subsequently developed a 3-cm ulcerated and crusted plaque with rolled borders on the right medial ankle (Figure 1). In addition, he had a palpable nodular cord on the medial leg from the ankle lesion to the mid thigh that was consistent with lymphocutaneous spread. Ultrasonography was negative for deep-vein thrombosis.

Because the patient’s recent migration from Central America was highly concerning for microbial infection, vancomycin and piperacillin-tazobactam were started empirically on admission. A punch biopsy from the right medial ankle was nondiagnostic, showing acute and chronic necrotizing inflammation along with numerous epithelioid histiocytes with a vaguely granulomatous appearance (Figure 2). A specimen from the right medial ankle that had already been taken by an astute border patrol medical provider was sent to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) for polymerase chain reaction analysis following admission and was found to be positive for Leishmania panamensis.

Given the concern for mucocutaneous leishmaniasis with this particular species, otolaryngology was consulted; however, the patient did not demonstrate mucocutaneous disease. Because of the elevated risk for persistent disease with L panamensis, systemic therapy was indicated and administered: IV amphotericin B 200 mg on days 1 through 5 and again on day 10. Improvement in the ulcer was seen after the 10-day regimen was completed.

Comment

Leishmaniasis can be broadly classified by geographic region or clinical presentation. Under the geographic region system, leishmaniasis can be categorized as Old World or New World. Old World leishmaniasis primarily is transmitted by Phlebotomus sandflies and carries the parasites Leishmania major and Leishmania tropica, among others. New World leishmaniasis is caused by Lutzomyia sandflies, which carry Leishmania mexicana, Leishmania braziliensis, Leishmania amazonensis, and others.6

Our patient presented with cutaneous leishmaniasis, one of 4 primary clinical disease forms of leishmaniasis; the other 3 forms under this classification system are diffuse cutaneous, mucocutaneous, and visceral leishmaniasis, also known as kala-azar.3,6 Cutaneous leishmaniasis is limited to the skin, particularly the face and extremities. This form is more common with Old World vectors, with most cases occurring in Peru, Brazil, and the Middle East. In Old World cutaneous leishmaniasis, the disease begins with a solitary nodule at the site of the bite that ulcerates and can continue to spread in a sporotrichoid pattern. This cutaneous form tends to heal slowly over months to years with residual scarring. New World cutaneous leishmaniasis can present with a variety of clinical manifestations, including ulcerative, sarcoidlike, miliary, and nodular lesions.6,7

The diffuse form of cutaneous leishmaniasis begins in a similar manner to the Old World cutaneous form: a single nodule spreads widely over the body, especially the nose, and covers the patient’s skin with keloidal or verrucous lesions that do not ulcerate. These nodules contain large groupings of Leishmania-filled foamy macrophages. Often, patients with diffuse cutaneous leishmaniasis are immunosuppressed and are unable to develop an immune response to leishmanin and other skin antigens.6,7

Mucocutaneous leishmaniasis predominantly is caused by the New World species L braziliensis but also has been attributed to L amazonensis, L panamensis, and L guyanensis. This form manifests as mucosal lesions that can develop simultaneously with cutaneous lesions but more commonly appear months to years after resolution of the skin infection. Patients often present with ulceration of the lip, nose, and oropharynx, and destruction of the nasopharynx can result in severe consequences such as obstruction of the airway and perforation of the nasal septum (also known as espundia).6,7

The most severe presentation of leishmaniasis is the visceral form (kala-azar), which presents with parasitic infection of the liver, spleen, and bone marrow. Most commonly caused by Leishmania donovani, Leishmania infantum, and Leishmania chagasi, this form has a long incubation period spanning months to years before presenting with diarrhea, hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, darkening of the skin (in Hindi, kala-azar means “black fever”), pancytopenia, lymphadenopathy, nephritis, and intestinal hemorrhage, among other severe manifestations. Visceral leishmaniasis has a poor prognosis: patients succumb to disease within 2 years if not treated.6,7

Diagnosis—Diagnosing leishmaniasis starts with a complete personal and medical history, paying close attention to travel and exposures. Diagnosis is most successfully performed by polymerase chain reaction analysis, which is both highly sensitive and specific but also can be determined by culture using Novy-McNeal-Nicolle medium or by light microscopy. Histologic findings include the marquee sign, which describes an array of amastigotes (promastigotes that have developed into the intracellular tissue-stage form) with kinetoplasts surrounding the periphery of parasitized histiocytes. Giemsa staining can be helpful in identifying organisms.2,6,7

The diagnosis in our case was challenging, as none of the above findings were seen in our patient. The specimen taken by the border patrol medical provider was negative on Gram, Giemsa, and Grocott-Gömöri methenamine silver staining; no amastigotes were identified. Another diagnostic modality (not performed in our patient) is the Montenegro delayed skin-reaction test, which often is positive in patients with cutaneous leishmaniasis but also yields a positive result in patients who have been cured of Leishmania infection.6

An important consideration in the diagnostic workup of leishmaniasis is that collaboration with the CDC can be helpful, such as in our case, as they provide clear guidance for specimen collection and processing.2

Treatment—Treating leishmaniasis is challenging and complex. Even the initial decision to treat depends on several factors, including the form of infection. Most visceral and mucocutaneous infections should be treated due to both the lack of self-resolution of these forms and the higher risk for a potentially life-threatening disease course; in contrast, cutaneous forms require further consideration before initiating treatment. Some indicators for treating cutaneous leishmaniasis include widespread infection, intention to decrease scarring, and lesions with the potential to cause further complications (eg, on the face or ears or close to joints).6-8

The treatment of choice for cutaneous and mucocutaneous leishmaniasis is pentavalent antimony; however, this drug can only be obtained in the United States for investigational use, requiring approval by the CDC. A 20-day intravenous or intramuscular course of 20 mg/kg per day typically is used for cutaneous cases; a 28-day course typically is used for mucosal forms.

Amphotericin B is not only the treatment of choice for visceral leishmaniasis but also is an important alternative therapy for patients with mucosal leishmaniasis or who are co-infected with HIV. Patients with visceral infection also should receive supportive care for any concomitant afflictions, such as malnutrition or other infections. Although different regimens have been described, the US Food and Drug Administration has created outlines of specific intravenous infusion schedules for liposomal amphotericin B in immunocompetent and immunosuppressed patients.8 Liposomal amphotericin B also has a more favorable toxicity profile than conventional amphotericin B deoxycholate, which is otherwise effective in combating visceral leishmaniasis.6-8

Other treatments that have been attempted include pentamidine, miltefosine, thermotherapy, oral itraconazole and fluconazole, rifampicin, metronidazole and cotrimoxazole, dapsone, photodynamic therapy, thermotherapy, topical paromomycin formulations, intralesional pentavalent antimony, and laser cryotherapy. Notable among these other agents is miltefosine, a US Food and Drug Administration–approved oral medication for adults and adolescents (used off-label for patients younger than 12 years) with cutaneous leishmaniasis caused by L braziliensis, L panamensis, or L guyanensis. Other oral options mentioned include the so-called azole antifungal medications, which historically have produced variable results. From the CDC’s reports, ketoconazole was moderately effective in Guatemala and Panama,8 whereas itraconazole did not demonstrate efficacy in Colombia, and the efficacy of fluconazole was inconsistent in different countries.8 When considering one of the local (as opposed to oral and parenteral) therapies mentioned, the extent of cutaneous findings as well as the risk of mucosal spread should be factored in.6-8

Understandably, a number of considerations can come into play in determining the appropriate treatment modality, including body region affected, clinical form, severity, and Leishmania species.6-8 Our case is of particular interest because it demonstrates the complexities behind the diagnosis and treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis, with careful consideration geared toward the species; for example, because our patient was infected with L panamensis, which is known to cause mucocutaneous disease, the infectious disease service decided to pursue systemic therapy with amphotericin B rather than topical treatment.

Prevention—Vector control is the primary means of preventing leishmaniasis under 2 umbrellas: environmental management and synthetic insecticides. The goal of environmental management is to eliminate the phlebotomine sandfly habitat; this was the primary method of vector control until 1940. Until that time, tree stumps were removed, indoor cracks and crevices were filled to prevent sandfly emergence, and areas around animal shelters were cleaned. These methods were highly dependent on community awareness and involvement; today, they can be combined with synthetic insecticides to offer maximum protection.

Synthetic insecticides include indoor sprays, treated nets, repellents, and impregnated dog collars, all of which control sandflies. However, the use of these insecticides in endemic areas, such as India, has driven development of insecticide resistance in many sandfly vector species.3

As of 2020, 5 vaccines against Leishmania have been created. Two are approved–one in Brazil and one in Uzbekistan–for human use as immunotherapy, while the other 3 have been developed to immunize dogs in Brazil. However, the effectiveness of these vaccines is under debate. First, one of the vaccines used as immunotherapy for cutaneous leishmaniasis must be used in combination with conventional chemotherapy; second, long-term effects of the canine vaccine are unknown.1 A preventive vaccine for humans is under development.1,3

Final Thoughts

Leishmaniasis remains a notable parasitic disease that is increasing in prevalence worldwide. Clinicians should be aware of this disease because early detection and treatment are essential to control infection.3 Health care providers in the United States should be especially aware of this condition among patients who have a history of travel or migration; those in Texas should recognize the current endemic status of leishmaniasis there.4,6

- Coutinho De Oliveira B, Duthie MS, Alves Pereira VR. Vaccines for leishmaniasis and the implications of their development for American tegumentary leishmaniasis. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2020;16:919-930. doi:10.1080/21645515.2019.1678998

- Chan CX, Simmons BJ, Call JE, et al. Cutaneous leishmaniasis successfully treated with miltefosine. Cutis. 2020;106:206-209. doi:10.12788/cutis.0086

- Balaska S, Fotakis EA, Chaskopoulou A, et al. Chemical control and insecticide resistance status of sand fly vectors worldwide. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2021;15:E0009586. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0009586

- Desjeux P. Leishmaniasis. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004;2:692. doi:10.1038/nrmicro981

- Michelutti A, Toniolo F, Bertola M, et al. Occurrence of Phlebotomine sand flies (Diptera: Psychodidae) in the northeastern plain of Italy. Parasit Vectors. 2021;14:164. doi:10.1186/s13071-021-04652-2

- Alkihan A, Hocker TLH. Infectious diseases: parasites and other creatures: protozoa. In: Alikhan A, Hocker TLH, eds. Review of Dermatology. Elsevier; 2024:329-331.

- Dinulos JGH. Infestations and bites. In: Habif TP, ed. Clinical Dermatology. Elsevier; 2016:630-634.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Leishmaniasis: resources for health professionals. US Department of Health and Human Services. March 20, 2023. Accessed October 5, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/leishmaniasis/health_professionals/index.html#:~:text=Liposomal%20amphotericin%20B%20is%20FDA,treatment%20of%20choice%20for%20U.S

- Coutinho De Oliveira B, Duthie MS, Alves Pereira VR. Vaccines for leishmaniasis and the implications of their development for American tegumentary leishmaniasis. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2020;16:919-930. doi:10.1080/21645515.2019.1678998

- Chan CX, Simmons BJ, Call JE, et al. Cutaneous leishmaniasis successfully treated with miltefosine. Cutis. 2020;106:206-209. doi:10.12788/cutis.0086

- Balaska S, Fotakis EA, Chaskopoulou A, et al. Chemical control and insecticide resistance status of sand fly vectors worldwide. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2021;15:E0009586. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0009586

- Desjeux P. Leishmaniasis. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004;2:692. doi:10.1038/nrmicro981

- Michelutti A, Toniolo F, Bertola M, et al. Occurrence of Phlebotomine sand flies (Diptera: Psychodidae) in the northeastern plain of Italy. Parasit Vectors. 2021;14:164. doi:10.1186/s13071-021-04652-2

- Alkihan A, Hocker TLH. Infectious diseases: parasites and other creatures: protozoa. In: Alikhan A, Hocker TLH, eds. Review of Dermatology. Elsevier; 2024:329-331.

- Dinulos JGH. Infestations and bites. In: Habif TP, ed. Clinical Dermatology. Elsevier; 2016:630-634.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Leishmaniasis: resources for health professionals. US Department of Health and Human Services. March 20, 2023. Accessed October 5, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/leishmaniasis/health_professionals/index.html#:~:text=Liposomal%20amphotericin%20B%20is%20FDA,treatment%20of%20choice%20for%20U.S

Practice Points

- The Phlebotomus and Lutzomyia genera of sandflies are vectors of Leishmania parasites, which can result in an array of clinical findings associated with leishmaniasis.

- Treatment options for leishmaniasis differ based on whether the infection is considered uncomplicated or complicated, which depends on the species of Leishmania; the number, size, and location of the lesion(s); and host immune status.

- All US practitioners should be aware of this pathogen, especially with regard to patients who have a history of travel to other countries. Health care professionals in states such as Texas and Oklahoma should be especially cognizant because these constitute one of the few areas in the United States where locally acquired cases of leishmaniasis have been reported.

Diffuse annular lesions

A 24-YEAR-OLD WOMAN with a history of guttate psoriasis, for which she was taking adalimumab, presented with a 2-week history of diffuse papules and plaques on her neck, back, torso, and upper and lower extremities (FIGURE 1). She said that the lesions were pruritic and seemed similar to those that erupted during past outbreaks of psoriasis—although they were more numerous and progressive. So, the patient (a nurse) decided to take her biweekly dose (40 mg) of adalimumab 1 week early. After administration, the rash significantly worsened, spreading to the rest of her trunk and extremities.

Physical exam was notable for multiple erythematous papules and plaques with central clearing and light peripheral scaling on both arms and legs, as well as her chest and back. The patient also indicated she’d adopted a stray cat 2 weeks prior. Given the patient’s pet exposure and the annular nature of the lesions, a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation was done.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Tinea corporis

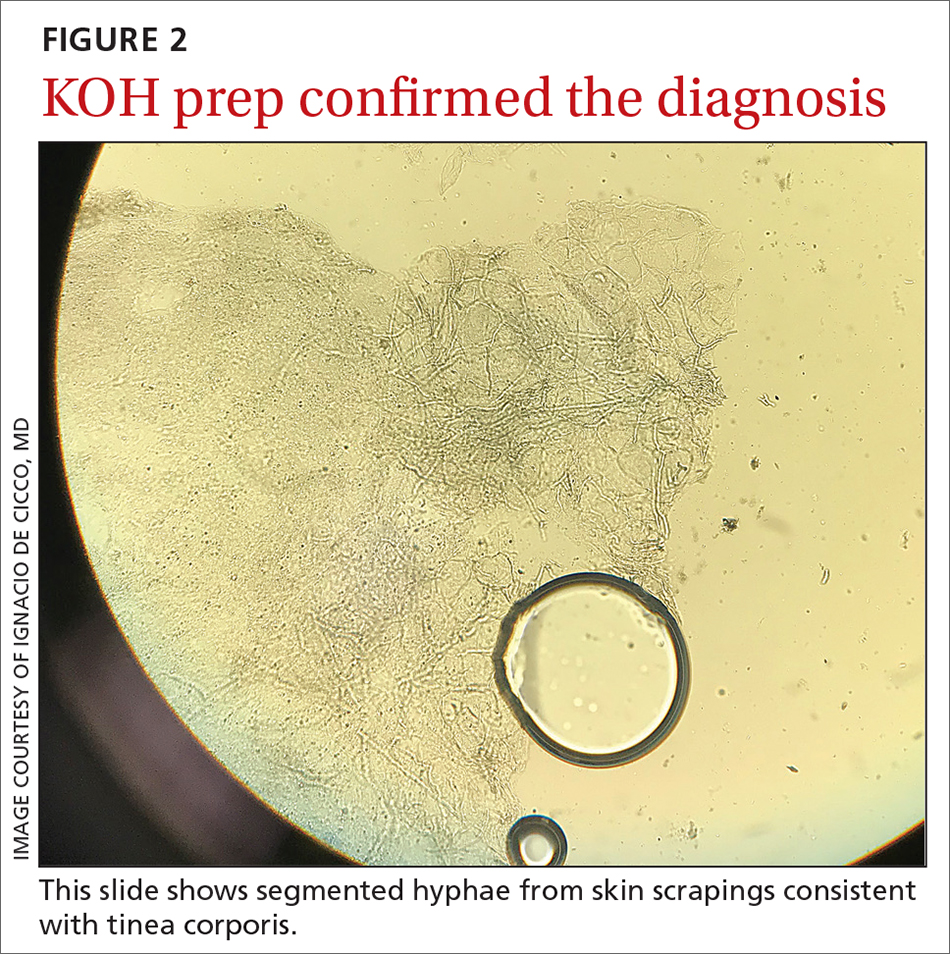

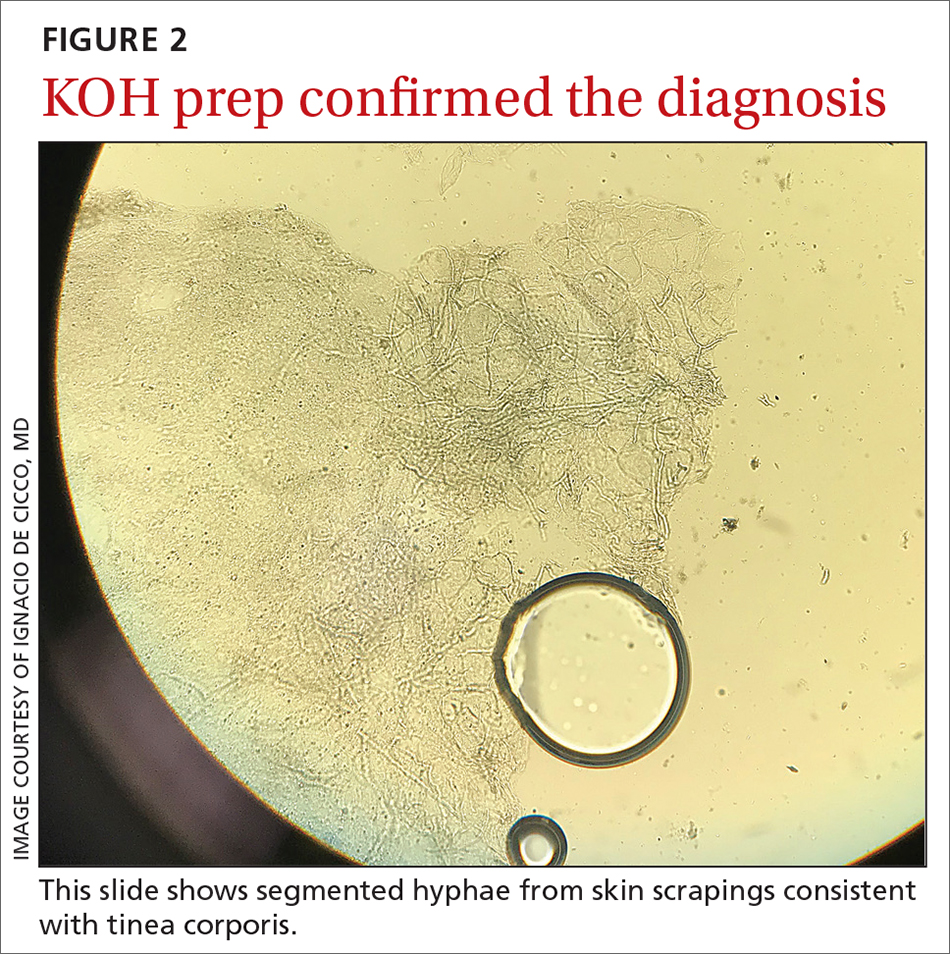

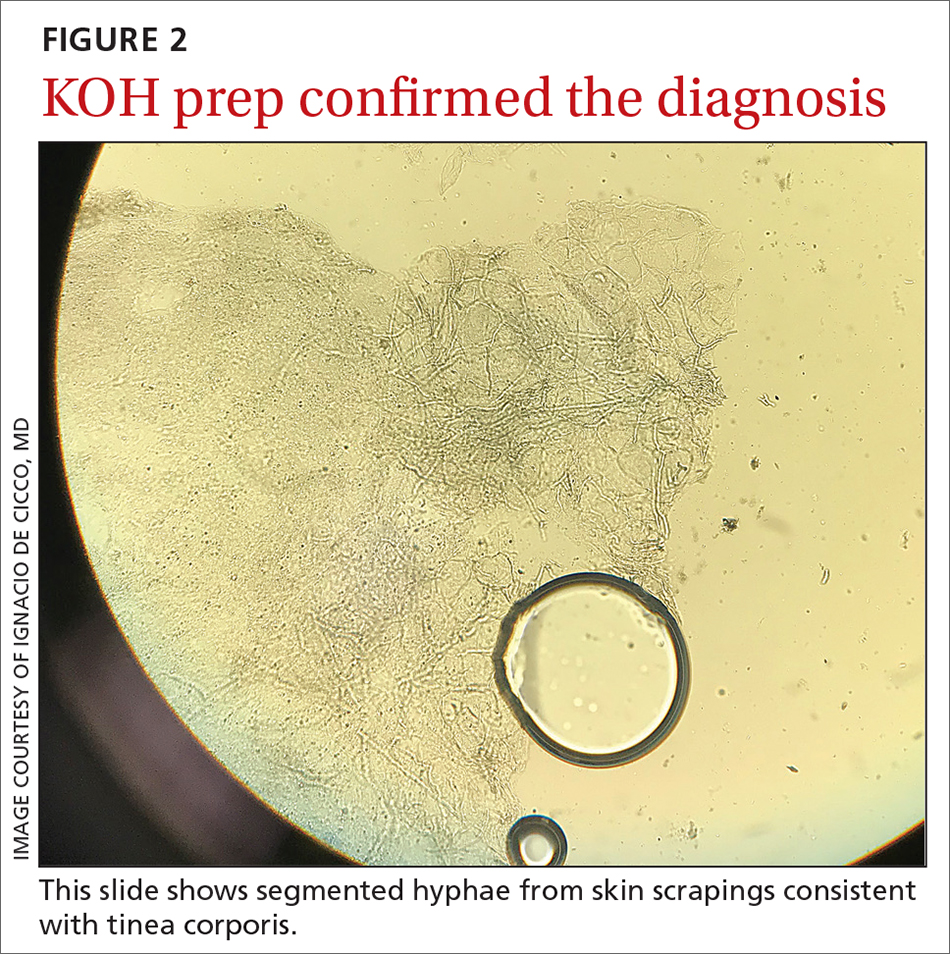

The KOH preparation was positive for hyphae in 4 separate sites (trunk, left arm, left leg, and left neck), confirming the diagnosis of severe extensive tinea corporis (FIGURE 2).

Dermatophyte (tinea) infections are caused by fungi that invade and reproduce in the skin, hair, and nails. Dermatophytes, which include the genera Trichophyton, Microsporum, and Epidermophyton, are the most common cause of superficial mycotic infections. As of 2016, the worldwide prevalence of superficial mycotic infections was 20% to 25%.1 Tinea corporis can result from contact with people, animals, or soil. Infections resulting from animal-to-human contact are often transmitted by domestic animals. In this case, the patient’s exposure was from her new cat.

Tinea corporis classically manifests as pruritic, erythematous patches or plaques with central clearing, giving it an annular appearance. The response to a tinea infection depends on the immune system of the host and can range in severity from superficial to severe.2 There are 2 forms of severe dermatophytosis: invasive, which involves localized perifollicular sites or deep dermatophytosis, and extensive, which is confined to the stratum corneum but results in numerous lesions.3

The diagnosis of tinea corporis is commonly confirmed using direct microscopic examination with 10% to 20% KOH preparation, which will show branching and septate hyphal filaments.4

Several conditions with annular lesions comprise the differential

The findings of pruritic annular erythematous lesions on the patient’s neck, chest, trunk, and bilateral extremities led the patient to suspect this was a worsening case of her guttate psoriasis. Other possible diagnoses included pityriasis rosea, subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE), and secondary syphilis.

Continue to: Guttate psoriasis

Guttate psoriasis would not typically progress during treatment with adalimumab, although tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors have been associated with worsening psoriasis. Guttate psoriasis manifests with small, pink to red, scaly raindrop-shaped patches over the trunk and extremities.

Pityriasis rosea, a rash that resembles branches of a Christmas tree, was strongly considered given the appearance of the lesions on the patient’s back. It commonly manifests as round to oval lesions with a subtle advancing border and central fine scaling, similar in shape and color to the lesions seen in tinea corporis.

SCLE has been associated with use of TNF inhibitors, but our patient had no other lupus-like symptoms, such as fatigue, fever, headaches, or joint pain. SCLE lesions are often annular with raised pink to red borders similar in appearance to tinea corporis.

Secondary syphilis was ruled out in this patient because she had a negative rapid plasma reagin test. Secondary syphilis most commonly manifests with diffuse, nonpruritic pink to red-brown lesions on the palms and soles of patients. Patients often have prodromal symptoms that include fever, weight loss, myalgias, headache, and sore throat.

Terbinafine, Yes, but for how long?

Historically, terbinafine has been prescribed at 250 mg once daily for 2 weeks for extensive tinea corporis. However, recent studies in India suggest that terbinafine should be dosed at 250 mg twice daily, with longer durations of treatment, due to resistance.5 In the United States, it is reasonable to prescribe oral terbinafine 250 mg once daily for 4 weeks and then re-evaluate the patient in a case of extensive tinea corporis.

Other oral antifungals that can effectively treat extensive tinea corporis include itraconazole, fluconazole, and griseofulvin.1 Itraconazole and terbinafine are equally effective and safe in the treatment of tinea corporis, although itraconazole is significantly more expensive.6 Furthermore, a recent study found that combination therapy with oral terbinafine and itraconazole is as safe as monotherapy and is an option when terbinafine resistance is suspected.7

Our patient was initially started on oral terbinafine 250 mg/d. After the first dose, the patient requested a change in medication because there was no improvement in the rash. The patient was then prescribed oral fluconazole 300 mg daily and the tinea cleared after 2 months of daily therapy. (We surmise the treatment course may have been prolonged due to the possible immunosuppressant effects of adalimumab.) At the completion of treatment for the tinea corporis, the patient was restarted on adalimumab 40 mg biweekly for her psoriasis.

1. Sahoo AK, Mahajan R. Management of tinea corporis, tinea cruris, and tinea pedis: a comprehensive review. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2016;7:77-86. doi: 10.4103/2229-5178.178099

2. Weitzman I, Summerbell RC. The dermatophytes. Clin Microbial Rev. 1995:8:240-259. doi: 10.1128/CMR.8.2.240

3. Rouzaud C, Hay R, Chosidow O, et al. Severe dermatophytosis and acquired or innate immunodeficiency: a review. J Fungi (Basel). 2015;2:4. doi: 10.3390/jof2010004

4. Kurade SM, Amladi SA, Miskeen AK. Skin scraping and a potassium hydroxide mount. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2006;72:238-41. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.25794

5. Khurana A, Sardana K, Chowdhary A. Antifungal resistance in dermatophytes: recent trends and therapeutic implications. Fungal Genet Biol. 2019;132:103255. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2019.103255

6. Bhatia A, Kanish B, Badyal DK, et al. Efficacy of oral terbinafine versus itraconazole in treatment of dermatophytic infection of skin - a prospective, randomized comparative study. Indian J Pharmacol. 2019;51:116-119.

7. Sharma P, Bhalla M, Thami GP, et al. Evaluation of efficacy and safety of oral terbinafine and itraconazole combination therapy in the management of dermatophytosis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2020;31:749-753. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2019.1612835

A 24-YEAR-OLD WOMAN with a history of guttate psoriasis, for which she was taking adalimumab, presented with a 2-week history of diffuse papules and plaques on her neck, back, torso, and upper and lower extremities (FIGURE 1). She said that the lesions were pruritic and seemed similar to those that erupted during past outbreaks of psoriasis—although they were more numerous and progressive. So, the patient (a nurse) decided to take her biweekly dose (40 mg) of adalimumab 1 week early. After administration, the rash significantly worsened, spreading to the rest of her trunk and extremities.

Physical exam was notable for multiple erythematous papules and plaques with central clearing and light peripheral scaling on both arms and legs, as well as her chest and back. The patient also indicated she’d adopted a stray cat 2 weeks prior. Given the patient’s pet exposure and the annular nature of the lesions, a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation was done.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Tinea corporis

The KOH preparation was positive for hyphae in 4 separate sites (trunk, left arm, left leg, and left neck), confirming the diagnosis of severe extensive tinea corporis (FIGURE 2).

Dermatophyte (tinea) infections are caused by fungi that invade and reproduce in the skin, hair, and nails. Dermatophytes, which include the genera Trichophyton, Microsporum, and Epidermophyton, are the most common cause of superficial mycotic infections. As of 2016, the worldwide prevalence of superficial mycotic infections was 20% to 25%.1 Tinea corporis can result from contact with people, animals, or soil. Infections resulting from animal-to-human contact are often transmitted by domestic animals. In this case, the patient’s exposure was from her new cat.

Tinea corporis classically manifests as pruritic, erythematous patches or plaques with central clearing, giving it an annular appearance. The response to a tinea infection depends on the immune system of the host and can range in severity from superficial to severe.2 There are 2 forms of severe dermatophytosis: invasive, which involves localized perifollicular sites or deep dermatophytosis, and extensive, which is confined to the stratum corneum but results in numerous lesions.3

The diagnosis of tinea corporis is commonly confirmed using direct microscopic examination with 10% to 20% KOH preparation, which will show branching and septate hyphal filaments.4

Several conditions with annular lesions comprise the differential

The findings of pruritic annular erythematous lesions on the patient’s neck, chest, trunk, and bilateral extremities led the patient to suspect this was a worsening case of her guttate psoriasis. Other possible diagnoses included pityriasis rosea, subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE), and secondary syphilis.

Continue to: Guttate psoriasis

Guttate psoriasis would not typically progress during treatment with adalimumab, although tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors have been associated with worsening psoriasis. Guttate psoriasis manifests with small, pink to red, scaly raindrop-shaped patches over the trunk and extremities.

Pityriasis rosea, a rash that resembles branches of a Christmas tree, was strongly considered given the appearance of the lesions on the patient’s back. It commonly manifests as round to oval lesions with a subtle advancing border and central fine scaling, similar in shape and color to the lesions seen in tinea corporis.

SCLE has been associated with use of TNF inhibitors, but our patient had no other lupus-like symptoms, such as fatigue, fever, headaches, or joint pain. SCLE lesions are often annular with raised pink to red borders similar in appearance to tinea corporis.

Secondary syphilis was ruled out in this patient because she had a negative rapid plasma reagin test. Secondary syphilis most commonly manifests with diffuse, nonpruritic pink to red-brown lesions on the palms and soles of patients. Patients often have prodromal symptoms that include fever, weight loss, myalgias, headache, and sore throat.

Terbinafine, Yes, but for how long?

Historically, terbinafine has been prescribed at 250 mg once daily for 2 weeks for extensive tinea corporis. However, recent studies in India suggest that terbinafine should be dosed at 250 mg twice daily, with longer durations of treatment, due to resistance.5 In the United States, it is reasonable to prescribe oral terbinafine 250 mg once daily for 4 weeks and then re-evaluate the patient in a case of extensive tinea corporis.

Other oral antifungals that can effectively treat extensive tinea corporis include itraconazole, fluconazole, and griseofulvin.1 Itraconazole and terbinafine are equally effective and safe in the treatment of tinea corporis, although itraconazole is significantly more expensive.6 Furthermore, a recent study found that combination therapy with oral terbinafine and itraconazole is as safe as monotherapy and is an option when terbinafine resistance is suspected.7

Our patient was initially started on oral terbinafine 250 mg/d. After the first dose, the patient requested a change in medication because there was no improvement in the rash. The patient was then prescribed oral fluconazole 300 mg daily and the tinea cleared after 2 months of daily therapy. (We surmise the treatment course may have been prolonged due to the possible immunosuppressant effects of adalimumab.) At the completion of treatment for the tinea corporis, the patient was restarted on adalimumab 40 mg biweekly for her psoriasis.

A 24-YEAR-OLD WOMAN with a history of guttate psoriasis, for which she was taking adalimumab, presented with a 2-week history of diffuse papules and plaques on her neck, back, torso, and upper and lower extremities (FIGURE 1). She said that the lesions were pruritic and seemed similar to those that erupted during past outbreaks of psoriasis—although they were more numerous and progressive. So, the patient (a nurse) decided to take her biweekly dose (40 mg) of adalimumab 1 week early. After administration, the rash significantly worsened, spreading to the rest of her trunk and extremities.

Physical exam was notable for multiple erythematous papules and plaques with central clearing and light peripheral scaling on both arms and legs, as well as her chest and back. The patient also indicated she’d adopted a stray cat 2 weeks prior. Given the patient’s pet exposure and the annular nature of the lesions, a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation was done.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Tinea corporis

The KOH preparation was positive for hyphae in 4 separate sites (trunk, left arm, left leg, and left neck), confirming the diagnosis of severe extensive tinea corporis (FIGURE 2).

Dermatophyte (tinea) infections are caused by fungi that invade and reproduce in the skin, hair, and nails. Dermatophytes, which include the genera Trichophyton, Microsporum, and Epidermophyton, are the most common cause of superficial mycotic infections. As of 2016, the worldwide prevalence of superficial mycotic infections was 20% to 25%.1 Tinea corporis can result from contact with people, animals, or soil. Infections resulting from animal-to-human contact are often transmitted by domestic animals. In this case, the patient’s exposure was from her new cat.

Tinea corporis classically manifests as pruritic, erythematous patches or plaques with central clearing, giving it an annular appearance. The response to a tinea infection depends on the immune system of the host and can range in severity from superficial to severe.2 There are 2 forms of severe dermatophytosis: invasive, which involves localized perifollicular sites or deep dermatophytosis, and extensive, which is confined to the stratum corneum but results in numerous lesions.3

The diagnosis of tinea corporis is commonly confirmed using direct microscopic examination with 10% to 20% KOH preparation, which will show branching and septate hyphal filaments.4

Several conditions with annular lesions comprise the differential

The findings of pruritic annular erythematous lesions on the patient’s neck, chest, trunk, and bilateral extremities led the patient to suspect this was a worsening case of her guttate psoriasis. Other possible diagnoses included pityriasis rosea, subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE), and secondary syphilis.

Continue to: Guttate psoriasis

Guttate psoriasis would not typically progress during treatment with adalimumab, although tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors have been associated with worsening psoriasis. Guttate psoriasis manifests with small, pink to red, scaly raindrop-shaped patches over the trunk and extremities.

Pityriasis rosea, a rash that resembles branches of a Christmas tree, was strongly considered given the appearance of the lesions on the patient’s back. It commonly manifests as round to oval lesions with a subtle advancing border and central fine scaling, similar in shape and color to the lesions seen in tinea corporis.

SCLE has been associated with use of TNF inhibitors, but our patient had no other lupus-like symptoms, such as fatigue, fever, headaches, or joint pain. SCLE lesions are often annular with raised pink to red borders similar in appearance to tinea corporis.

Secondary syphilis was ruled out in this patient because she had a negative rapid plasma reagin test. Secondary syphilis most commonly manifests with diffuse, nonpruritic pink to red-brown lesions on the palms and soles of patients. Patients often have prodromal symptoms that include fever, weight loss, myalgias, headache, and sore throat.

Terbinafine, Yes, but for how long?

Historically, terbinafine has been prescribed at 250 mg once daily for 2 weeks for extensive tinea corporis. However, recent studies in India suggest that terbinafine should be dosed at 250 mg twice daily, with longer durations of treatment, due to resistance.5 In the United States, it is reasonable to prescribe oral terbinafine 250 mg once daily for 4 weeks and then re-evaluate the patient in a case of extensive tinea corporis.

Other oral antifungals that can effectively treat extensive tinea corporis include itraconazole, fluconazole, and griseofulvin.1 Itraconazole and terbinafine are equally effective and safe in the treatment of tinea corporis, although itraconazole is significantly more expensive.6 Furthermore, a recent study found that combination therapy with oral terbinafine and itraconazole is as safe as monotherapy and is an option when terbinafine resistance is suspected.7

Our patient was initially started on oral terbinafine 250 mg/d. After the first dose, the patient requested a change in medication because there was no improvement in the rash. The patient was then prescribed oral fluconazole 300 mg daily and the tinea cleared after 2 months of daily therapy. (We surmise the treatment course may have been prolonged due to the possible immunosuppressant effects of adalimumab.) At the completion of treatment for the tinea corporis, the patient was restarted on adalimumab 40 mg biweekly for her psoriasis.

1. Sahoo AK, Mahajan R. Management of tinea corporis, tinea cruris, and tinea pedis: a comprehensive review. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2016;7:77-86. doi: 10.4103/2229-5178.178099

2. Weitzman I, Summerbell RC. The dermatophytes. Clin Microbial Rev. 1995:8:240-259. doi: 10.1128/CMR.8.2.240

3. Rouzaud C, Hay R, Chosidow O, et al. Severe dermatophytosis and acquired or innate immunodeficiency: a review. J Fungi (Basel). 2015;2:4. doi: 10.3390/jof2010004

4. Kurade SM, Amladi SA, Miskeen AK. Skin scraping and a potassium hydroxide mount. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2006;72:238-41. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.25794

5. Khurana A, Sardana K, Chowdhary A. Antifungal resistance in dermatophytes: recent trends and therapeutic implications. Fungal Genet Biol. 2019;132:103255. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2019.103255

6. Bhatia A, Kanish B, Badyal DK, et al. Efficacy of oral terbinafine versus itraconazole in treatment of dermatophytic infection of skin - a prospective, randomized comparative study. Indian J Pharmacol. 2019;51:116-119.

7. Sharma P, Bhalla M, Thami GP, et al. Evaluation of efficacy and safety of oral terbinafine and itraconazole combination therapy in the management of dermatophytosis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2020;31:749-753. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2019.1612835

1. Sahoo AK, Mahajan R. Management of tinea corporis, tinea cruris, and tinea pedis: a comprehensive review. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2016;7:77-86. doi: 10.4103/2229-5178.178099

2. Weitzman I, Summerbell RC. The dermatophytes. Clin Microbial Rev. 1995:8:240-259. doi: 10.1128/CMR.8.2.240

3. Rouzaud C, Hay R, Chosidow O, et al. Severe dermatophytosis and acquired or innate immunodeficiency: a review. J Fungi (Basel). 2015;2:4. doi: 10.3390/jof2010004

4. Kurade SM, Amladi SA, Miskeen AK. Skin scraping and a potassium hydroxide mount. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2006;72:238-41. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.25794

5. Khurana A, Sardana K, Chowdhary A. Antifungal resistance in dermatophytes: recent trends and therapeutic implications. Fungal Genet Biol. 2019;132:103255. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2019.103255

6. Bhatia A, Kanish B, Badyal DK, et al. Efficacy of oral terbinafine versus itraconazole in treatment of dermatophytic infection of skin - a prospective, randomized comparative study. Indian J Pharmacol. 2019;51:116-119.

7. Sharma P, Bhalla M, Thami GP, et al. Evaluation of efficacy and safety of oral terbinafine and itraconazole combination therapy in the management of dermatophytosis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2020;31:749-753. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2019.1612835