User login

Discharge Appointments

Dicharge of a patient from the hospital is a complicated, interprofessional endeavor.1, 2 Several institutions report that discharge is one of the least satisfying elements of the patient's hospital experience.35 Recent evidence suggests that a poorly planned or disorganized discharge may compromise patient safety in the period soon after dismissal.6 Several initiatives have been aimed at improving patient satisfaction and safety related to discharge.710

In 2000 the Mayo Clinic (Rochester, Minnesota) Department of Internal Medicine leadership established a goal to improve patient satisfaction with the hospital dismissal process. Patient focus group data suggested that uncertainty about the anticipated date and time of discharge causes frustration to some patients and families.

We hypothesized that an appointment to leave the hospital might be practicable. We joined an Institute for Healthcare Improvement collaborative (Improving Flow Through Acute Care Settings, 1 of 6 Improvement Action Network [IMPACT] Learning and Innovation Communities) aimed at scheduling discharge appointments (DAs). The collaborating members deemed that, although the ideal DA is set at least a day in advance, a same‐day DA is also desirable for both patient satisfaction and staff task organization in pursuit of a high‐quality discharge.

METHODS

This project was approved by the Mayo Foundation Institutional Review Board. We tested the following hypotheses:

It is possible to make and display DAs in various care units.

Most DAs can be scheduled a day before dismissal.

Most DA patients depart on time.

Setting

Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, is a tertiary academic medical center with 2 hospitals (Saint Marys and Rochester Methodist) that house a total of 1951 licensed beds in 76 care units.

The preliminary study displaying DAs was carried out in the Innovation and Quality (IQ) Unit of Saint Marys Hospital, a 23‐bed general medical care unit that supports both resident and nonresident services. Traditionally, primary services usually consist of an attending physician and house officer physicians (junior and senior residents). Less commonly, primary services consist of an attending physician and either a nurse‐practitioner or a physician assistant.

The design pilot took place between August 2 and December 24, 2003. The subsequent, larger study of applicability took place across 8 care units (including the IQ Unit) between December 28, 2003, and April 25, 2004.

Preliminary Work: Design Pilot

We designed bedside dry‐erase wall displays and mounted them in the rooms in plain view of patients and their families and caregivers. Pilot testing of DA scheduling was done on a general medical care unit from August 2 to December 24, 2003. To optimize the process for scheduling a DA, our team developed 21 small tests to change the dismissal process through plan, do, study, and act cycles.11

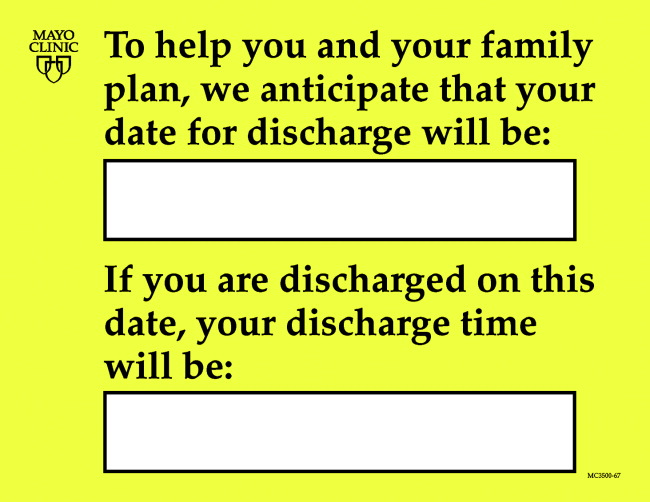

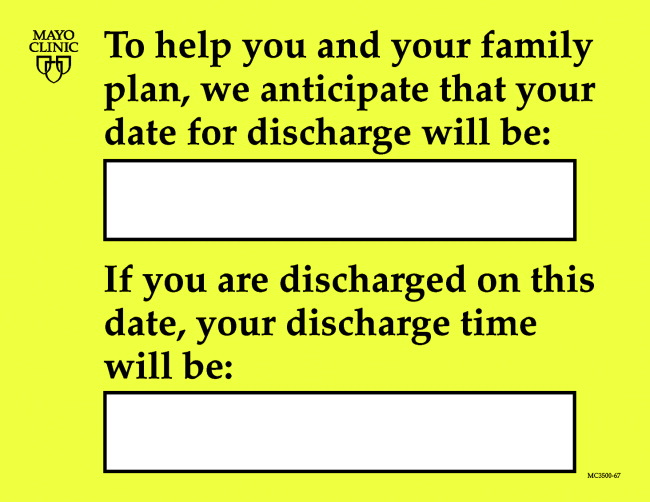

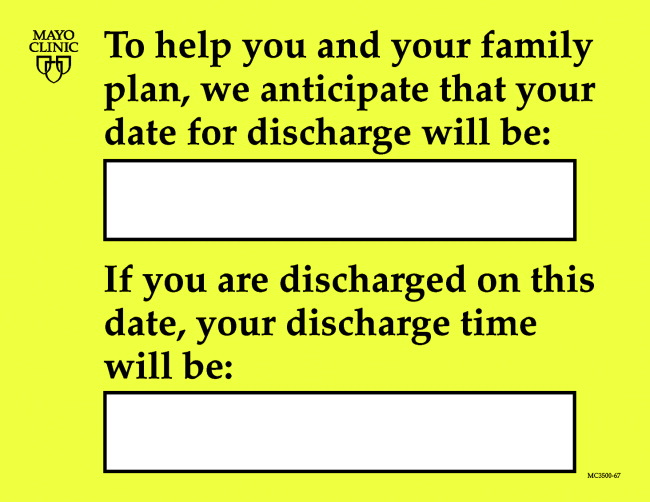

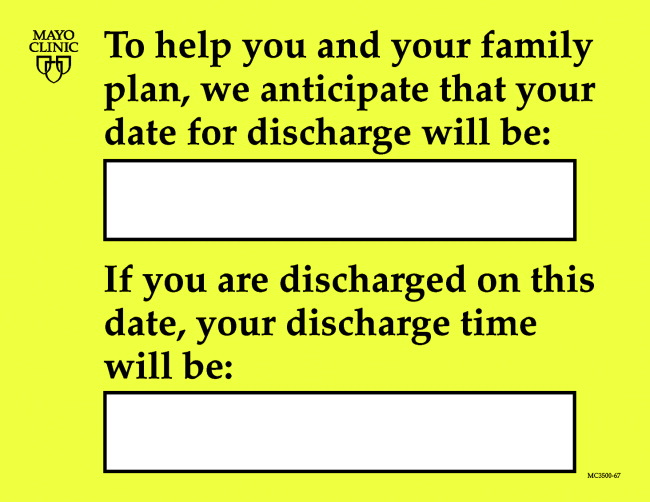

The recommended process was that as soon as an organized discharge could be reasonably envisioned, the primary service provider would discuss with the patient, family, and primary nurse (and a social service worker, if involved) the anticipated discharge day. A member of the primary service was to handwrite (with a marker) the anticipated day on the specially designed bedside dry‐erase board (Fig. 1) in view of the patient. The same primary service prescribers could amend this anticipated day (or time) by repeating the process of consultation and discussion as needed. The time of the DA could be written on the DA board (or amended) by either a member of the primary service or the primary care nurse.

Each morning, the primary care nurse transmitted the DA board data to the admission, discharge, and transfer log kept at the unit secretary desk (in which the actual discharge time has always been routinely recorded by the unit secretary).

Adoption of DA Scheduling in Other Care Units

Several meetings were held with 7 other patient care unit leaders about adopting the protocol. These units, both medical and surgical, were selected according to 3 criteria: (1) prior participation in unit‐level continuous improvement work, (2) current or recent work in any aspect of the discharge process, and (3) a reputation for having innovative nursing leadership and staff.

Data Acquisition and Analysis

Data were collected daily from each participating unit's admission, discharge, and transfer log: both the actual time of departure and the DA, if one had been scheduled. For each DA patient, the DA time was compared with the actual departure time.

RESULTS

During the 4‐month study of discharges across 8 care units, 1256 of 2046 patients (61%) received a DA; 576 of the DAs (46%) were scheduled at least 1 day in advance (Table 1). Among patients with a DA, 752 were discharged on time (60%), and only 240 (19%) were tardy.

| Unit | DAs | Departure time of patients compared with DA | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Type of unit | No. of patients | Patients with DAs, n (%) | DAs scheduled ϵ 1 day ahead, n (%) | On time, n (%)a | Early, n (%) | Late, n (%) |

| |||||||

| 1 | Neurology/neurosurgery | 525 | 270 (51) | 0 (0) | 175 (65) | 44 (16) | 51 (19) |

| 2 | Surgery (mixed) | 481 | 325 (68) | 289 (89) | 166 (51) | 101 (31) | 58 (18) |

| 3 | General internal medicine (IQ Unit) | 466 | 243 (52) | 35 (14) | 132 (54) | 50 (21) | 61 (25) |

| 4 | Neurology/neurosurgery | 267 | 189 (71) | 40 (21) | 119 (63) | 41 (22) | 29 (15) |

| 5 | Vascular surgery | 201 | 127 (63) | 127 (100) | 90 (71) | 12 (9) | 25 (20) |

| 6 | Psychiatry | 46 | 42 (91) | 42 (100) | 28 (67) | 9 (21) | 5 (12) |

| 7 | Orthopedic surgeryelective | 38 | 38 (100) | 22 (58) | 24 (63) | 3 (8) | 11 (29) |

| 8 | Orthopedic surgerytrauma | 22 | 22 (100) | 21 (95) | 18 (82) | 4 (18) | 0 (0) |

| Total | 2046 | 1256 (61) | 576 (46) | 752 (60) | 264 (21) | 240 (19) | |

DISCUSSION

In response to patient focus group feedback, we designed a tool and a process by which a DA could be made and posted at bedside. Among 2046 patients discharged from 8 care units over 4 months, 61% (1256) had a posted, in‐room DA. Almost half the patients with DAs (46%) had a DA scheduled at least 1 calendar day ahead. Remarkably, among patients with a DA, fewer than 20% were discharged tardily. In‐room posting of DAs across a spectrum of care units appears to be practicable, even in the face of extant diagnostic or therapeutic uncertainty.

This was an initial test‐of‐concept project and an exploratory trial. The limitations are: (1) satisfaction (patient, family, nurse, and physician) was not tested with any validated survey instrument, (2) length of stay was not studied, (3) reasons for variable DA success among care units were not ascertained, and (4) resource use was not measured.

Anecdotal information from a postdischarge phone survey indicated that patients seemed appreciative of a DA. The survey data were not included in this article because the survey tool was not a validated instrument and the interviewer (a coauthor) was not blinded to the hypothesis and was therefore subject to bias. No negative comments were received through informal real‐time feedback from patients and family during the making and posting of DAs, and encouraging comments were common.

Physician participation in posting the DA appeared to be key, and the unavoidable dialogue about the clinical rationale for a chosen date seemed welcome. A telling anecdote came from a patient who did not have a DA board: I didn't get the same treatment as my roommate with the [DA] board. The other doctors talked with [him] more about discharge. I wish my team would have done this more with me.

We cannot be certain of the reasons for the care unit disparity in setting and meeting DAs. We speculate that the level of staff enthusiasm for DAs explains the variation rather than patient population characteristics. Further, we cannot explain why 39% of the patients did not receive a DA. Physician feedback was generally, but not uniformly, positive. Negative comments that might explain DA omissions include: (1) patients already are informed and awarethe tool is superfluous; (2) the day of discharge is unknowable in advance; and (3) patients or family members will hold us to it or be upset if the DA is changed.

We expected that diagnostic uncertainty might pose challenges to providing DAs. When primary service providers were reassured that DAs could be amended, this concern was reduced (but not eliminated). It seemed useful for providers to envision the earliest day of discharge by assuming that the results of a pending key test or consultation would be favorable. Frequency of DA modification was not studied. DAs were amended, however, and patients (to our knowledge) seemed unperturbedperhaps because of an almost unavoidable discussion of the clinical rationale because the act of posting the DA occurred in full view of (and in partnership with) the patient.

A trend toward discharge earlier in the day was observed (data not shown). Theoretically, such a trend offers the potential to improve inpatient flow, in part by discharging patients before morning surgical cases are completed.

Although we had many favorable comments about DAs from patients, family members, and nurses, satisfaction of patients, families, and staff members deserves formal study. Further, it is not known whether unused DA boards might contribute to patient dissatisfaction. Any effect that the display of DAs may have on the length of stay also may be a topic worthy of future study.

CONCLUSIONS

Patients and their families sometimes desire more communication about the anticipated day and time of hospital discharge. We designed a process for making a tentative DA and a tool by which the DA could be posted at the bedside. The results of this study suggest that (1) despite some uncertainty it is possible to schedule and post DAs in‐room in various care units and in various settings, (2) DAs were made at least a day ahead of time in almost half the DA discharges, and (3) most DA discharges were characterized by on‐time departure. In addition, patient, family, and nursing satisfaction (in relation to the DA) warrants further investigation.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the valuable insights and collaboration of our colleagues Deborah R. Fischer, Steven L. Bahnemann, Matthew Skelton, MD, Lauri J. Dahl, Pamela O. Johnson, MSN, Debra A. Hernke, MSN, Susan L. Stirn, MSN, Barbara R. Spurrier, Ryan R. Armbruster, Todd J. Bille, and Donna K. Lawson of the Mayo Clinic and Mayo Foundation.

- ,,, et al.Learning from patients: a discharge planning improvement project.Jt Comm J Qual Improv.1996;22:311–22.

- ,,,,,, et al.Payer‐hospital collaboration to improve patient satisfaction with hospital discharge.Jt Comm J Qual Improv.1996;22:336–344.

- ,,,,,.How was your hospital stay? Patients' reports about their care in Canadian hospitals.CMAJ.1994;150:1813–1822.

- .A hospitalization from hell: a patient's perspective on quality.Ann Intern Med.2003;138:33–39.

- ,,.Predictors of elder and family caregiver satisfaction with discharge planning.J Cardiovasc Nurs.2000;14:76–87.

- ,,,,.The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital.Ann Intern Med.2003;138:161–167.

- ,,, et al.Patient callback program: a quality improvement, customer service, and marketing tool.J Health Care Mark.1993;13:60–65.

- ,,,.Effects of a medical team coordinator on length of hospital stay.CMAJ.1992;146:511–515.

- ,.Discharge planning from hospital to home.Cochrane Database Syst Rev.2000;4:CD000313.

- ,,,.Continuity of care and patient outcomes after hospital discharge.J Gen Intern Med.2004;19:624–631.

- Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Cambridge, UK: Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Available from: http://www.ihi.org/IHI/Topics/Improvement/ImprovementMethods/HowToImprove/testingchanges.htm. Accessed July 28,2006.

Dicharge of a patient from the hospital is a complicated, interprofessional endeavor.1, 2 Several institutions report that discharge is one of the least satisfying elements of the patient's hospital experience.35 Recent evidence suggests that a poorly planned or disorganized discharge may compromise patient safety in the period soon after dismissal.6 Several initiatives have been aimed at improving patient satisfaction and safety related to discharge.710

In 2000 the Mayo Clinic (Rochester, Minnesota) Department of Internal Medicine leadership established a goal to improve patient satisfaction with the hospital dismissal process. Patient focus group data suggested that uncertainty about the anticipated date and time of discharge causes frustration to some patients and families.

We hypothesized that an appointment to leave the hospital might be practicable. We joined an Institute for Healthcare Improvement collaborative (Improving Flow Through Acute Care Settings, 1 of 6 Improvement Action Network [IMPACT] Learning and Innovation Communities) aimed at scheduling discharge appointments (DAs). The collaborating members deemed that, although the ideal DA is set at least a day in advance, a same‐day DA is also desirable for both patient satisfaction and staff task organization in pursuit of a high‐quality discharge.

METHODS

This project was approved by the Mayo Foundation Institutional Review Board. We tested the following hypotheses:

It is possible to make and display DAs in various care units.

Most DAs can be scheduled a day before dismissal.

Most DA patients depart on time.

Setting

Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, is a tertiary academic medical center with 2 hospitals (Saint Marys and Rochester Methodist) that house a total of 1951 licensed beds in 76 care units.

The preliminary study displaying DAs was carried out in the Innovation and Quality (IQ) Unit of Saint Marys Hospital, a 23‐bed general medical care unit that supports both resident and nonresident services. Traditionally, primary services usually consist of an attending physician and house officer physicians (junior and senior residents). Less commonly, primary services consist of an attending physician and either a nurse‐practitioner or a physician assistant.

The design pilot took place between August 2 and December 24, 2003. The subsequent, larger study of applicability took place across 8 care units (including the IQ Unit) between December 28, 2003, and April 25, 2004.

Preliminary Work: Design Pilot

We designed bedside dry‐erase wall displays and mounted them in the rooms in plain view of patients and their families and caregivers. Pilot testing of DA scheduling was done on a general medical care unit from August 2 to December 24, 2003. To optimize the process for scheduling a DA, our team developed 21 small tests to change the dismissal process through plan, do, study, and act cycles.11

The recommended process was that as soon as an organized discharge could be reasonably envisioned, the primary service provider would discuss with the patient, family, and primary nurse (and a social service worker, if involved) the anticipated discharge day. A member of the primary service was to handwrite (with a marker) the anticipated day on the specially designed bedside dry‐erase board (Fig. 1) in view of the patient. The same primary service prescribers could amend this anticipated day (or time) by repeating the process of consultation and discussion as needed. The time of the DA could be written on the DA board (or amended) by either a member of the primary service or the primary care nurse.

Each morning, the primary care nurse transmitted the DA board data to the admission, discharge, and transfer log kept at the unit secretary desk (in which the actual discharge time has always been routinely recorded by the unit secretary).

Adoption of DA Scheduling in Other Care Units

Several meetings were held with 7 other patient care unit leaders about adopting the protocol. These units, both medical and surgical, were selected according to 3 criteria: (1) prior participation in unit‐level continuous improvement work, (2) current or recent work in any aspect of the discharge process, and (3) a reputation for having innovative nursing leadership and staff.

Data Acquisition and Analysis

Data were collected daily from each participating unit's admission, discharge, and transfer log: both the actual time of departure and the DA, if one had been scheduled. For each DA patient, the DA time was compared with the actual departure time.

RESULTS

During the 4‐month study of discharges across 8 care units, 1256 of 2046 patients (61%) received a DA; 576 of the DAs (46%) were scheduled at least 1 day in advance (Table 1). Among patients with a DA, 752 were discharged on time (60%), and only 240 (19%) were tardy.

| Unit | DAs | Departure time of patients compared with DA | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Type of unit | No. of patients | Patients with DAs, n (%) | DAs scheduled ϵ 1 day ahead, n (%) | On time, n (%)a | Early, n (%) | Late, n (%) |

| |||||||

| 1 | Neurology/neurosurgery | 525 | 270 (51) | 0 (0) | 175 (65) | 44 (16) | 51 (19) |

| 2 | Surgery (mixed) | 481 | 325 (68) | 289 (89) | 166 (51) | 101 (31) | 58 (18) |

| 3 | General internal medicine (IQ Unit) | 466 | 243 (52) | 35 (14) | 132 (54) | 50 (21) | 61 (25) |

| 4 | Neurology/neurosurgery | 267 | 189 (71) | 40 (21) | 119 (63) | 41 (22) | 29 (15) |

| 5 | Vascular surgery | 201 | 127 (63) | 127 (100) | 90 (71) | 12 (9) | 25 (20) |

| 6 | Psychiatry | 46 | 42 (91) | 42 (100) | 28 (67) | 9 (21) | 5 (12) |

| 7 | Orthopedic surgeryelective | 38 | 38 (100) | 22 (58) | 24 (63) | 3 (8) | 11 (29) |

| 8 | Orthopedic surgerytrauma | 22 | 22 (100) | 21 (95) | 18 (82) | 4 (18) | 0 (0) |

| Total | 2046 | 1256 (61) | 576 (46) | 752 (60) | 264 (21) | 240 (19) | |

DISCUSSION

In response to patient focus group feedback, we designed a tool and a process by which a DA could be made and posted at bedside. Among 2046 patients discharged from 8 care units over 4 months, 61% (1256) had a posted, in‐room DA. Almost half the patients with DAs (46%) had a DA scheduled at least 1 calendar day ahead. Remarkably, among patients with a DA, fewer than 20% were discharged tardily. In‐room posting of DAs across a spectrum of care units appears to be practicable, even in the face of extant diagnostic or therapeutic uncertainty.

This was an initial test‐of‐concept project and an exploratory trial. The limitations are: (1) satisfaction (patient, family, nurse, and physician) was not tested with any validated survey instrument, (2) length of stay was not studied, (3) reasons for variable DA success among care units were not ascertained, and (4) resource use was not measured.

Anecdotal information from a postdischarge phone survey indicated that patients seemed appreciative of a DA. The survey data were not included in this article because the survey tool was not a validated instrument and the interviewer (a coauthor) was not blinded to the hypothesis and was therefore subject to bias. No negative comments were received through informal real‐time feedback from patients and family during the making and posting of DAs, and encouraging comments were common.

Physician participation in posting the DA appeared to be key, and the unavoidable dialogue about the clinical rationale for a chosen date seemed welcome. A telling anecdote came from a patient who did not have a DA board: I didn't get the same treatment as my roommate with the [DA] board. The other doctors talked with [him] more about discharge. I wish my team would have done this more with me.

We cannot be certain of the reasons for the care unit disparity in setting and meeting DAs. We speculate that the level of staff enthusiasm for DAs explains the variation rather than patient population characteristics. Further, we cannot explain why 39% of the patients did not receive a DA. Physician feedback was generally, but not uniformly, positive. Negative comments that might explain DA omissions include: (1) patients already are informed and awarethe tool is superfluous; (2) the day of discharge is unknowable in advance; and (3) patients or family members will hold us to it or be upset if the DA is changed.

We expected that diagnostic uncertainty might pose challenges to providing DAs. When primary service providers were reassured that DAs could be amended, this concern was reduced (but not eliminated). It seemed useful for providers to envision the earliest day of discharge by assuming that the results of a pending key test or consultation would be favorable. Frequency of DA modification was not studied. DAs were amended, however, and patients (to our knowledge) seemed unperturbedperhaps because of an almost unavoidable discussion of the clinical rationale because the act of posting the DA occurred in full view of (and in partnership with) the patient.

A trend toward discharge earlier in the day was observed (data not shown). Theoretically, such a trend offers the potential to improve inpatient flow, in part by discharging patients before morning surgical cases are completed.

Although we had many favorable comments about DAs from patients, family members, and nurses, satisfaction of patients, families, and staff members deserves formal study. Further, it is not known whether unused DA boards might contribute to patient dissatisfaction. Any effect that the display of DAs may have on the length of stay also may be a topic worthy of future study.

CONCLUSIONS

Patients and their families sometimes desire more communication about the anticipated day and time of hospital discharge. We designed a process for making a tentative DA and a tool by which the DA could be posted at the bedside. The results of this study suggest that (1) despite some uncertainty it is possible to schedule and post DAs in‐room in various care units and in various settings, (2) DAs were made at least a day ahead of time in almost half the DA discharges, and (3) most DA discharges were characterized by on‐time departure. In addition, patient, family, and nursing satisfaction (in relation to the DA) warrants further investigation.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the valuable insights and collaboration of our colleagues Deborah R. Fischer, Steven L. Bahnemann, Matthew Skelton, MD, Lauri J. Dahl, Pamela O. Johnson, MSN, Debra A. Hernke, MSN, Susan L. Stirn, MSN, Barbara R. Spurrier, Ryan R. Armbruster, Todd J. Bille, and Donna K. Lawson of the Mayo Clinic and Mayo Foundation.

Dicharge of a patient from the hospital is a complicated, interprofessional endeavor.1, 2 Several institutions report that discharge is one of the least satisfying elements of the patient's hospital experience.35 Recent evidence suggests that a poorly planned or disorganized discharge may compromise patient safety in the period soon after dismissal.6 Several initiatives have been aimed at improving patient satisfaction and safety related to discharge.710

In 2000 the Mayo Clinic (Rochester, Minnesota) Department of Internal Medicine leadership established a goal to improve patient satisfaction with the hospital dismissal process. Patient focus group data suggested that uncertainty about the anticipated date and time of discharge causes frustration to some patients and families.

We hypothesized that an appointment to leave the hospital might be practicable. We joined an Institute for Healthcare Improvement collaborative (Improving Flow Through Acute Care Settings, 1 of 6 Improvement Action Network [IMPACT] Learning and Innovation Communities) aimed at scheduling discharge appointments (DAs). The collaborating members deemed that, although the ideal DA is set at least a day in advance, a same‐day DA is also desirable for both patient satisfaction and staff task organization in pursuit of a high‐quality discharge.

METHODS

This project was approved by the Mayo Foundation Institutional Review Board. We tested the following hypotheses:

It is possible to make and display DAs in various care units.

Most DAs can be scheduled a day before dismissal.

Most DA patients depart on time.

Setting

Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, is a tertiary academic medical center with 2 hospitals (Saint Marys and Rochester Methodist) that house a total of 1951 licensed beds in 76 care units.

The preliminary study displaying DAs was carried out in the Innovation and Quality (IQ) Unit of Saint Marys Hospital, a 23‐bed general medical care unit that supports both resident and nonresident services. Traditionally, primary services usually consist of an attending physician and house officer physicians (junior and senior residents). Less commonly, primary services consist of an attending physician and either a nurse‐practitioner or a physician assistant.

The design pilot took place between August 2 and December 24, 2003. The subsequent, larger study of applicability took place across 8 care units (including the IQ Unit) between December 28, 2003, and April 25, 2004.

Preliminary Work: Design Pilot

We designed bedside dry‐erase wall displays and mounted them in the rooms in plain view of patients and their families and caregivers. Pilot testing of DA scheduling was done on a general medical care unit from August 2 to December 24, 2003. To optimize the process for scheduling a DA, our team developed 21 small tests to change the dismissal process through plan, do, study, and act cycles.11

The recommended process was that as soon as an organized discharge could be reasonably envisioned, the primary service provider would discuss with the patient, family, and primary nurse (and a social service worker, if involved) the anticipated discharge day. A member of the primary service was to handwrite (with a marker) the anticipated day on the specially designed bedside dry‐erase board (Fig. 1) in view of the patient. The same primary service prescribers could amend this anticipated day (or time) by repeating the process of consultation and discussion as needed. The time of the DA could be written on the DA board (or amended) by either a member of the primary service or the primary care nurse.

Each morning, the primary care nurse transmitted the DA board data to the admission, discharge, and transfer log kept at the unit secretary desk (in which the actual discharge time has always been routinely recorded by the unit secretary).

Adoption of DA Scheduling in Other Care Units

Several meetings were held with 7 other patient care unit leaders about adopting the protocol. These units, both medical and surgical, were selected according to 3 criteria: (1) prior participation in unit‐level continuous improvement work, (2) current or recent work in any aspect of the discharge process, and (3) a reputation for having innovative nursing leadership and staff.

Data Acquisition and Analysis

Data were collected daily from each participating unit's admission, discharge, and transfer log: both the actual time of departure and the DA, if one had been scheduled. For each DA patient, the DA time was compared with the actual departure time.

RESULTS

During the 4‐month study of discharges across 8 care units, 1256 of 2046 patients (61%) received a DA; 576 of the DAs (46%) were scheduled at least 1 day in advance (Table 1). Among patients with a DA, 752 were discharged on time (60%), and only 240 (19%) were tardy.

| Unit | DAs | Departure time of patients compared with DA | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Type of unit | No. of patients | Patients with DAs, n (%) | DAs scheduled ϵ 1 day ahead, n (%) | On time, n (%)a | Early, n (%) | Late, n (%) |

| |||||||

| 1 | Neurology/neurosurgery | 525 | 270 (51) | 0 (0) | 175 (65) | 44 (16) | 51 (19) |

| 2 | Surgery (mixed) | 481 | 325 (68) | 289 (89) | 166 (51) | 101 (31) | 58 (18) |

| 3 | General internal medicine (IQ Unit) | 466 | 243 (52) | 35 (14) | 132 (54) | 50 (21) | 61 (25) |

| 4 | Neurology/neurosurgery | 267 | 189 (71) | 40 (21) | 119 (63) | 41 (22) | 29 (15) |

| 5 | Vascular surgery | 201 | 127 (63) | 127 (100) | 90 (71) | 12 (9) | 25 (20) |

| 6 | Psychiatry | 46 | 42 (91) | 42 (100) | 28 (67) | 9 (21) | 5 (12) |

| 7 | Orthopedic surgeryelective | 38 | 38 (100) | 22 (58) | 24 (63) | 3 (8) | 11 (29) |

| 8 | Orthopedic surgerytrauma | 22 | 22 (100) | 21 (95) | 18 (82) | 4 (18) | 0 (0) |

| Total | 2046 | 1256 (61) | 576 (46) | 752 (60) | 264 (21) | 240 (19) | |

DISCUSSION

In response to patient focus group feedback, we designed a tool and a process by which a DA could be made and posted at bedside. Among 2046 patients discharged from 8 care units over 4 months, 61% (1256) had a posted, in‐room DA. Almost half the patients with DAs (46%) had a DA scheduled at least 1 calendar day ahead. Remarkably, among patients with a DA, fewer than 20% were discharged tardily. In‐room posting of DAs across a spectrum of care units appears to be practicable, even in the face of extant diagnostic or therapeutic uncertainty.

This was an initial test‐of‐concept project and an exploratory trial. The limitations are: (1) satisfaction (patient, family, nurse, and physician) was not tested with any validated survey instrument, (2) length of stay was not studied, (3) reasons for variable DA success among care units were not ascertained, and (4) resource use was not measured.

Anecdotal information from a postdischarge phone survey indicated that patients seemed appreciative of a DA. The survey data were not included in this article because the survey tool was not a validated instrument and the interviewer (a coauthor) was not blinded to the hypothesis and was therefore subject to bias. No negative comments were received through informal real‐time feedback from patients and family during the making and posting of DAs, and encouraging comments were common.

Physician participation in posting the DA appeared to be key, and the unavoidable dialogue about the clinical rationale for a chosen date seemed welcome. A telling anecdote came from a patient who did not have a DA board: I didn't get the same treatment as my roommate with the [DA] board. The other doctors talked with [him] more about discharge. I wish my team would have done this more with me.

We cannot be certain of the reasons for the care unit disparity in setting and meeting DAs. We speculate that the level of staff enthusiasm for DAs explains the variation rather than patient population characteristics. Further, we cannot explain why 39% of the patients did not receive a DA. Physician feedback was generally, but not uniformly, positive. Negative comments that might explain DA omissions include: (1) patients already are informed and awarethe tool is superfluous; (2) the day of discharge is unknowable in advance; and (3) patients or family members will hold us to it or be upset if the DA is changed.

We expected that diagnostic uncertainty might pose challenges to providing DAs. When primary service providers were reassured that DAs could be amended, this concern was reduced (but not eliminated). It seemed useful for providers to envision the earliest day of discharge by assuming that the results of a pending key test or consultation would be favorable. Frequency of DA modification was not studied. DAs were amended, however, and patients (to our knowledge) seemed unperturbedperhaps because of an almost unavoidable discussion of the clinical rationale because the act of posting the DA occurred in full view of (and in partnership with) the patient.

A trend toward discharge earlier in the day was observed (data not shown). Theoretically, such a trend offers the potential to improve inpatient flow, in part by discharging patients before morning surgical cases are completed.

Although we had many favorable comments about DAs from patients, family members, and nurses, satisfaction of patients, families, and staff members deserves formal study. Further, it is not known whether unused DA boards might contribute to patient dissatisfaction. Any effect that the display of DAs may have on the length of stay also may be a topic worthy of future study.

CONCLUSIONS

Patients and their families sometimes desire more communication about the anticipated day and time of hospital discharge. We designed a process for making a tentative DA and a tool by which the DA could be posted at the bedside. The results of this study suggest that (1) despite some uncertainty it is possible to schedule and post DAs in‐room in various care units and in various settings, (2) DAs were made at least a day ahead of time in almost half the DA discharges, and (3) most DA discharges were characterized by on‐time departure. In addition, patient, family, and nursing satisfaction (in relation to the DA) warrants further investigation.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the valuable insights and collaboration of our colleagues Deborah R. Fischer, Steven L. Bahnemann, Matthew Skelton, MD, Lauri J. Dahl, Pamela O. Johnson, MSN, Debra A. Hernke, MSN, Susan L. Stirn, MSN, Barbara R. Spurrier, Ryan R. Armbruster, Todd J. Bille, and Donna K. Lawson of the Mayo Clinic and Mayo Foundation.

- ,,, et al.Learning from patients: a discharge planning improvement project.Jt Comm J Qual Improv.1996;22:311–22.

- ,,,,,, et al.Payer‐hospital collaboration to improve patient satisfaction with hospital discharge.Jt Comm J Qual Improv.1996;22:336–344.

- ,,,,,.How was your hospital stay? Patients' reports about their care in Canadian hospitals.CMAJ.1994;150:1813–1822.

- .A hospitalization from hell: a patient's perspective on quality.Ann Intern Med.2003;138:33–39.

- ,,.Predictors of elder and family caregiver satisfaction with discharge planning.J Cardiovasc Nurs.2000;14:76–87.

- ,,,,.The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital.Ann Intern Med.2003;138:161–167.

- ,,, et al.Patient callback program: a quality improvement, customer service, and marketing tool.J Health Care Mark.1993;13:60–65.

- ,,,.Effects of a medical team coordinator on length of hospital stay.CMAJ.1992;146:511–515.

- ,.Discharge planning from hospital to home.Cochrane Database Syst Rev.2000;4:CD000313.

- ,,,.Continuity of care and patient outcomes after hospital discharge.J Gen Intern Med.2004;19:624–631.

- Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Cambridge, UK: Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Available from: http://www.ihi.org/IHI/Topics/Improvement/ImprovementMethods/HowToImprove/testingchanges.htm. Accessed July 28,2006.

- ,,, et al.Learning from patients: a discharge planning improvement project.Jt Comm J Qual Improv.1996;22:311–22.

- ,,,,,, et al.Payer‐hospital collaboration to improve patient satisfaction with hospital discharge.Jt Comm J Qual Improv.1996;22:336–344.

- ,,,,,.How was your hospital stay? Patients' reports about their care in Canadian hospitals.CMAJ.1994;150:1813–1822.

- .A hospitalization from hell: a patient's perspective on quality.Ann Intern Med.2003;138:33–39.

- ,,.Predictors of elder and family caregiver satisfaction with discharge planning.J Cardiovasc Nurs.2000;14:76–87.

- ,,,,.The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital.Ann Intern Med.2003;138:161–167.

- ,,, et al.Patient callback program: a quality improvement, customer service, and marketing tool.J Health Care Mark.1993;13:60–65.

- ,,,.Effects of a medical team coordinator on length of hospital stay.CMAJ.1992;146:511–515.

- ,.Discharge planning from hospital to home.Cochrane Database Syst Rev.2000;4:CD000313.

- ,,,.Continuity of care and patient outcomes after hospital discharge.J Gen Intern Med.2004;19:624–631.

- Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Cambridge, UK: Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Available from: http://www.ihi.org/IHI/Topics/Improvement/ImprovementMethods/HowToImprove/testingchanges.htm. Accessed July 28,2006.

Copyright © 2007 Society of Hospital Medicine