User login

Calculations of an academic hospitalist

The term “academic hospitalist” has come to mean more than a mere affiliation to an academic medical center (AMC). Academic hospitalists perform various clinical roles like staffing house staff teams, covering nonteaching services, critical care services, procedure teams, night services, medical consultation, and comanagement services.

Over the last decade, academic hospitalists have successfully managed many nonclinical roles in areas like research, medical unit leadership, faculty development, faculty affairs, quality, safety, informatics, utilization review, clinical documentation, throughput, group management, hospital administration, and educational leadership. The role of an academic hospital is as clear as a chocolate martini these days. Here we present some recent trends in academic hospital medicine.

Compensation

From SHM’s State of Hospital Medicine report (SoHM)2014 to 2018 data, the median compensation for U.S. academic hospitalists has risen by an average of 5.15% every year, although increases vary by rank.1 From 2016 to 2018, clinical instructors saw the most significant growth, 11.23% per year, suggesting a need to remain competitive for junior hospitalists. Compensation also varies by geographic area, with the Southern region reporting the highest compensation. Over the last decade, academic hospitalists received, on average, a 28%-35% lower salary, compared with community hospitalists.

Patient population and census

Lower patient encounters and compensation of the academic hospitalists poses the chicken or the egg dilemma. In the 2018 SoHM report, academic hospitalists had an average of 17% fewer encounters. Of note, AMC patients tend to have higher complexity, as measured by the Case Mix Index (CMI – the average diagnosis-related group weight of a hospital).2 A higher CMI is a surrogate marker for the diagnostic diversity, clinical complexity, and resource needs of the patient population in the hospital.

Productivity and financial metrics

The financial bottom line is a critical aspect, and as a report in the Journal of Hospital Medicine described, all health care executives look at business metrics while making decisions.3 Below are some significant academic and community comparisons from SoHM 2018.

- Collections, encounters, and wRVUs (work relative value units) were highly correlated. All of them were lower for academic hospitalists, corroborating the fact that they see a smaller number of patients. Clinical full-time equivalents (cFTE) is a vernacular of how much of the faculty time is devoted to clinical activities. The academic data from SoHM achieves the same target, as it is standardized to 100% billable clinical activity, so the fact that many academic hospitalists do not work a full-time clinical schedule is not a factor in their lower production.

- Charges had a smaller gap likely because of sicker patients in AMCs. The higher acuity difference can also explain 12% higher wRVU/encounter for academic hospitalists.

- The wRVU/encounter ratio can indicate a few patterns: high acuity of patients in AMCs, higher levels of evaluation and management documentation, or both. As the encounters and charges have the same percentage differences, we would place our bets on the former.

- Compensation per encounter and compensation per wRVU showed that academic hospitalists do get a slight advantage.

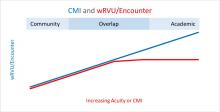

CMI and wRVUs

Although the SoHM does not capture information on patient acuity or CMI, we speculate that the relationship between CMI and wRVUs may be more or less linear at lower levels of acuity. However, once level III E/M billing is achieved (assuming there is no critical care provided), wRVUs/encounter plateau, even as acuity continues to increase. This plateau effect may be seen more often in high-acuity AMC settings than in community hospitals.

So, in our opinion, compensation models based solely on wRVU production would not do justice for hospitalists in AMC settings since these models would fail to capture the extra work involved with very-high-acuity patients. SoHM 2018 shows the financial support per wRVU for AMC is $45.81, and for the community is $41.28, an 11% difference. We think the higher financial support per wRVU for academic practices may be related to the lost wRVU potential of caring for very-high-acuity patients.

Conclusion

In an academic setting, hospitalists are reforming the field of hospital medicine and defining the ways we could deliver care. They are the pillars of collaboration, education, research, innovation, quality, and safety. It would be increasingly crucial for academic hospitalist leaders to use comparative metrics from SoHM to advocate for their group. The bottom line can be explained by the title of the qualitative study in JHM referenced above: “Collaboration, not calculation.”3

Dr. Chadha is division chief for the division of hospital medicine at the University of Kentucky Healthcare, Lexington. He actively leads efforts of recruiting, scheduling, practice analysis, and operation of the group. He is a first-time member of the practice analysis committee. Ms. Dede is division administrator for the division of hospital medicine at the University of Kentucky Healthcare. She prepares and manages budgets, liaisons with the downstream revenue teams, and contributes to the building of academic compensation models. She is serving in the practice administrators committee for the second year and is currently vice chair of the Executive Council for the Practice Administrators special interest group.

References

1. State of Hospital Medicine Report. https://www.hospitalmedicine.org/practice-management/shms-state-of-hospital-medicine/

2. Deloitte Center for Health Solutions. Academic Medical Centers: Joining forces with community providers for broad benefits and positive outcomes. 2015. https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/pages/life-sciences-and-health-care/articles/academic-medical-centers-consolidation.html

3. White AA et al. Collaboration, not calculation: A qualitative study of how hospital executives value hospital medicine groups. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(10):662‐7.

The term “academic hospitalist” has come to mean more than a mere affiliation to an academic medical center (AMC). Academic hospitalists perform various clinical roles like staffing house staff teams, covering nonteaching services, critical care services, procedure teams, night services, medical consultation, and comanagement services.

Over the last decade, academic hospitalists have successfully managed many nonclinical roles in areas like research, medical unit leadership, faculty development, faculty affairs, quality, safety, informatics, utilization review, clinical documentation, throughput, group management, hospital administration, and educational leadership. The role of an academic hospital is as clear as a chocolate martini these days. Here we present some recent trends in academic hospital medicine.

Compensation

From SHM’s State of Hospital Medicine report (SoHM)2014 to 2018 data, the median compensation for U.S. academic hospitalists has risen by an average of 5.15% every year, although increases vary by rank.1 From 2016 to 2018, clinical instructors saw the most significant growth, 11.23% per year, suggesting a need to remain competitive for junior hospitalists. Compensation also varies by geographic area, with the Southern region reporting the highest compensation. Over the last decade, academic hospitalists received, on average, a 28%-35% lower salary, compared with community hospitalists.

Patient population and census

Lower patient encounters and compensation of the academic hospitalists poses the chicken or the egg dilemma. In the 2018 SoHM report, academic hospitalists had an average of 17% fewer encounters. Of note, AMC patients tend to have higher complexity, as measured by the Case Mix Index (CMI – the average diagnosis-related group weight of a hospital).2 A higher CMI is a surrogate marker for the diagnostic diversity, clinical complexity, and resource needs of the patient population in the hospital.

Productivity and financial metrics

The financial bottom line is a critical aspect, and as a report in the Journal of Hospital Medicine described, all health care executives look at business metrics while making decisions.3 Below are some significant academic and community comparisons from SoHM 2018.

- Collections, encounters, and wRVUs (work relative value units) were highly correlated. All of them were lower for academic hospitalists, corroborating the fact that they see a smaller number of patients. Clinical full-time equivalents (cFTE) is a vernacular of how much of the faculty time is devoted to clinical activities. The academic data from SoHM achieves the same target, as it is standardized to 100% billable clinical activity, so the fact that many academic hospitalists do not work a full-time clinical schedule is not a factor in their lower production.

- Charges had a smaller gap likely because of sicker patients in AMCs. The higher acuity difference can also explain 12% higher wRVU/encounter for academic hospitalists.

- The wRVU/encounter ratio can indicate a few patterns: high acuity of patients in AMCs, higher levels of evaluation and management documentation, or both. As the encounters and charges have the same percentage differences, we would place our bets on the former.

- Compensation per encounter and compensation per wRVU showed that academic hospitalists do get a slight advantage.

CMI and wRVUs

Although the SoHM does not capture information on patient acuity or CMI, we speculate that the relationship between CMI and wRVUs may be more or less linear at lower levels of acuity. However, once level III E/M billing is achieved (assuming there is no critical care provided), wRVUs/encounter plateau, even as acuity continues to increase. This plateau effect may be seen more often in high-acuity AMC settings than in community hospitals.

So, in our opinion, compensation models based solely on wRVU production would not do justice for hospitalists in AMC settings since these models would fail to capture the extra work involved with very-high-acuity patients. SoHM 2018 shows the financial support per wRVU for AMC is $45.81, and for the community is $41.28, an 11% difference. We think the higher financial support per wRVU for academic practices may be related to the lost wRVU potential of caring for very-high-acuity patients.

Conclusion

In an academic setting, hospitalists are reforming the field of hospital medicine and defining the ways we could deliver care. They are the pillars of collaboration, education, research, innovation, quality, and safety. It would be increasingly crucial for academic hospitalist leaders to use comparative metrics from SoHM to advocate for their group. The bottom line can be explained by the title of the qualitative study in JHM referenced above: “Collaboration, not calculation.”3

Dr. Chadha is division chief for the division of hospital medicine at the University of Kentucky Healthcare, Lexington. He actively leads efforts of recruiting, scheduling, practice analysis, and operation of the group. He is a first-time member of the practice analysis committee. Ms. Dede is division administrator for the division of hospital medicine at the University of Kentucky Healthcare. She prepares and manages budgets, liaisons with the downstream revenue teams, and contributes to the building of academic compensation models. She is serving in the practice administrators committee for the second year and is currently vice chair of the Executive Council for the Practice Administrators special interest group.

References

1. State of Hospital Medicine Report. https://www.hospitalmedicine.org/practice-management/shms-state-of-hospital-medicine/

2. Deloitte Center for Health Solutions. Academic Medical Centers: Joining forces with community providers for broad benefits and positive outcomes. 2015. https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/pages/life-sciences-and-health-care/articles/academic-medical-centers-consolidation.html

3. White AA et al. Collaboration, not calculation: A qualitative study of how hospital executives value hospital medicine groups. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(10):662‐7.

The term “academic hospitalist” has come to mean more than a mere affiliation to an academic medical center (AMC). Academic hospitalists perform various clinical roles like staffing house staff teams, covering nonteaching services, critical care services, procedure teams, night services, medical consultation, and comanagement services.

Over the last decade, academic hospitalists have successfully managed many nonclinical roles in areas like research, medical unit leadership, faculty development, faculty affairs, quality, safety, informatics, utilization review, clinical documentation, throughput, group management, hospital administration, and educational leadership. The role of an academic hospital is as clear as a chocolate martini these days. Here we present some recent trends in academic hospital medicine.

Compensation

From SHM’s State of Hospital Medicine report (SoHM)2014 to 2018 data, the median compensation for U.S. academic hospitalists has risen by an average of 5.15% every year, although increases vary by rank.1 From 2016 to 2018, clinical instructors saw the most significant growth, 11.23% per year, suggesting a need to remain competitive for junior hospitalists. Compensation also varies by geographic area, with the Southern region reporting the highest compensation. Over the last decade, academic hospitalists received, on average, a 28%-35% lower salary, compared with community hospitalists.

Patient population and census

Lower patient encounters and compensation of the academic hospitalists poses the chicken or the egg dilemma. In the 2018 SoHM report, academic hospitalists had an average of 17% fewer encounters. Of note, AMC patients tend to have higher complexity, as measured by the Case Mix Index (CMI – the average diagnosis-related group weight of a hospital).2 A higher CMI is a surrogate marker for the diagnostic diversity, clinical complexity, and resource needs of the patient population in the hospital.

Productivity and financial metrics

The financial bottom line is a critical aspect, and as a report in the Journal of Hospital Medicine described, all health care executives look at business metrics while making decisions.3 Below are some significant academic and community comparisons from SoHM 2018.

- Collections, encounters, and wRVUs (work relative value units) were highly correlated. All of them were lower for academic hospitalists, corroborating the fact that they see a smaller number of patients. Clinical full-time equivalents (cFTE) is a vernacular of how much of the faculty time is devoted to clinical activities. The academic data from SoHM achieves the same target, as it is standardized to 100% billable clinical activity, so the fact that many academic hospitalists do not work a full-time clinical schedule is not a factor in their lower production.

- Charges had a smaller gap likely because of sicker patients in AMCs. The higher acuity difference can also explain 12% higher wRVU/encounter for academic hospitalists.

- The wRVU/encounter ratio can indicate a few patterns: high acuity of patients in AMCs, higher levels of evaluation and management documentation, or both. As the encounters and charges have the same percentage differences, we would place our bets on the former.

- Compensation per encounter and compensation per wRVU showed that academic hospitalists do get a slight advantage.

CMI and wRVUs

Although the SoHM does not capture information on patient acuity or CMI, we speculate that the relationship between CMI and wRVUs may be more or less linear at lower levels of acuity. However, once level III E/M billing is achieved (assuming there is no critical care provided), wRVUs/encounter plateau, even as acuity continues to increase. This plateau effect may be seen more often in high-acuity AMC settings than in community hospitals.

So, in our opinion, compensation models based solely on wRVU production would not do justice for hospitalists in AMC settings since these models would fail to capture the extra work involved with very-high-acuity patients. SoHM 2018 shows the financial support per wRVU for AMC is $45.81, and for the community is $41.28, an 11% difference. We think the higher financial support per wRVU for academic practices may be related to the lost wRVU potential of caring for very-high-acuity patients.

Conclusion

In an academic setting, hospitalists are reforming the field of hospital medicine and defining the ways we could deliver care. They are the pillars of collaboration, education, research, innovation, quality, and safety. It would be increasingly crucial for academic hospitalist leaders to use comparative metrics from SoHM to advocate for their group. The bottom line can be explained by the title of the qualitative study in JHM referenced above: “Collaboration, not calculation.”3

Dr. Chadha is division chief for the division of hospital medicine at the University of Kentucky Healthcare, Lexington. He actively leads efforts of recruiting, scheduling, practice analysis, and operation of the group. He is a first-time member of the practice analysis committee. Ms. Dede is division administrator for the division of hospital medicine at the University of Kentucky Healthcare. She prepares and manages budgets, liaisons with the downstream revenue teams, and contributes to the building of academic compensation models. She is serving in the practice administrators committee for the second year and is currently vice chair of the Executive Council for the Practice Administrators special interest group.

References

1. State of Hospital Medicine Report. https://www.hospitalmedicine.org/practice-management/shms-state-of-hospital-medicine/

2. Deloitte Center for Health Solutions. Academic Medical Centers: Joining forces with community providers for broad benefits and positive outcomes. 2015. https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/pages/life-sciences-and-health-care/articles/academic-medical-centers-consolidation.html

3. White AA et al. Collaboration, not calculation: A qualitative study of how hospital executives value hospital medicine groups. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(10):662‐7.

To be, or not to be ... on backup?

A staffing backup system is essential

It was late 2011. We were a practice of around 20 physicians, and just starting to integrate advanced practice providers into our practice. Our average daily census was about 100 patients and slightly more than 50% of our services were resident services.

My boss, colleague, friend, and mentor – Charles “Chuck” Sargent, MD, and I were on service together early one Saturday morning; Chuck gets a phone call that one of our colleagues was ill. With just 10 physicians working and 10 off, it was an ordeal for Chuck to call all 10 colleagues. Unlike most times, no one could come to moonlight that day. In the end Chuck and I took care of our colleague’s patients.

Yes, it was an exhausting few days, but illness and family needs do not come announced. Now, close to a decade later, we are a practice of 70 physicians and 16 advanced practice providers, our average daily census is about 270 patients, and we have two backup physicians every day – known as Jeopardy-1 and Jeopardy-2. Paternity leave, maternity leave, minor illness, minor trauma, surgery, and family needs are common for our practice. We considered it a good year when we utilized our Jeopardy-1 and Jeopardy-2 for 10% and 1% respectively; and for the past year with a lot of needs, we employed Jeopardy-1 and Jeopardy-2 for 25% and 10%, respectively.

A staffing backup system is a necessary tool for almost every practice. Not having a formal backup system doesn’t mean you don’t need one or you don’t have one – it is just called “no formal backup system.” The Society of Hospital Medicine’s State of Hospital Medicine Reports (SoHM) have been providing data about staffing backup systems every other year. Backup systems come in three flavors. The first system is no formal backup, which means the leaders of the program scramble for coverage every time there is a need. The second is a voluntary backup system in which clinicians volunteer to be on a backup schedule, and the third is a mandatory system in which all or most clinicians are required to be on the backup schedule.

The cumulative data reported in the 2014, 2016, and 2018 SoHM for hospital medicine groups serving adults only, children only, and both adults and children (weighted for number of groups reporting), suggests that 48.3% of respondent practices had no formal backup system, 31.7% had a voluntary system, and 20% had a mandatory backup system.

When we look at different populations served, the trend of “no formal backup system” responses is in decline. The 2014, 2016, and 2018 SoHM reports for hospital medicine groups serving adults, children, and both adults and children, reinforce such trends. The SoHM 2018 report shows 65.6% of hospital medicine groups serving children, 41.6% of groups serving adults, and only 25% of groups serving both adults and children have “no formal backup system.” Our medicine-pediatrics colleagues seem to be leading the trend and have already deduced that, for a solid practice, a backup system is a necessity.

It is also important to see the trend of “no formal backup system” based on geographic area, employer type, academic status, or total number of full-time employees. As we would have predicted, the larger the group the more likely they are to have a backup system. For academic practices a similar trend was seen; they had a higher percentage of some type of backup system year after year.

When it comes to compensation for backup work, four patterns were explored by the SoHM over the years. The most common type of arrangement was “no additional compensation for being on the backup schedule, but additional compensation was provided when called into work.” This kind of arrangement would be easiest to negotiate when the hospitalist and the employer sit across a table. There is nothing at risk for the employer when there isn’t a need, or when there is a need to fill a shift.

The least common method was “additional compensation for being on the backup schedule, but no additional compensation if called into work.” From employers’ perspectives, this is an extra expense and is not ideal for the hospitalist either. In the middle of the pack were “no additional compensation associated with the backup plan” (the second most common model), while the third most common model was “additional compensation for being on the backup schedule, as well as additional compensation if called into work.”

Once you have seen one hospital medicine practice, you have seen one hospital medicine practice. There are different needs for every group, and the backup system – as well its compensation model – has to be designed for it. Thankfully, the SoHM reports reveal the patterns and trends so that we don’t have to reinvent the wheel. For our practice, we decreased a week of clinical service for 2 weeks a year of backup. Every time we activate our backup system, the person coming in receives extra compensation or a similar shift off. In the long run, our backup system didn’t kill us, but rather made us stronger as a group.

Dr. Chadha is interim division chief in the division of hospital medicine at the University of Kentucky HealthCare in Lexington. He actively leads efforts of recruiting, scheduling, practice analysis, and operation of the group. He is a first-time member of the SHM Practice Analysis Committee. Ms. Babb is administrative support associate in the division of hospital medicine at University of Kentucky HealthCare.

A staffing backup system is essential

A staffing backup system is essential

It was late 2011. We were a practice of around 20 physicians, and just starting to integrate advanced practice providers into our practice. Our average daily census was about 100 patients and slightly more than 50% of our services were resident services.

My boss, colleague, friend, and mentor – Charles “Chuck” Sargent, MD, and I were on service together early one Saturday morning; Chuck gets a phone call that one of our colleagues was ill. With just 10 physicians working and 10 off, it was an ordeal for Chuck to call all 10 colleagues. Unlike most times, no one could come to moonlight that day. In the end Chuck and I took care of our colleague’s patients.

Yes, it was an exhausting few days, but illness and family needs do not come announced. Now, close to a decade later, we are a practice of 70 physicians and 16 advanced practice providers, our average daily census is about 270 patients, and we have two backup physicians every day – known as Jeopardy-1 and Jeopardy-2. Paternity leave, maternity leave, minor illness, minor trauma, surgery, and family needs are common for our practice. We considered it a good year when we utilized our Jeopardy-1 and Jeopardy-2 for 10% and 1% respectively; and for the past year with a lot of needs, we employed Jeopardy-1 and Jeopardy-2 for 25% and 10%, respectively.

A staffing backup system is a necessary tool for almost every practice. Not having a formal backup system doesn’t mean you don’t need one or you don’t have one – it is just called “no formal backup system.” The Society of Hospital Medicine’s State of Hospital Medicine Reports (SoHM) have been providing data about staffing backup systems every other year. Backup systems come in three flavors. The first system is no formal backup, which means the leaders of the program scramble for coverage every time there is a need. The second is a voluntary backup system in which clinicians volunteer to be on a backup schedule, and the third is a mandatory system in which all or most clinicians are required to be on the backup schedule.

The cumulative data reported in the 2014, 2016, and 2018 SoHM for hospital medicine groups serving adults only, children only, and both adults and children (weighted for number of groups reporting), suggests that 48.3% of respondent practices had no formal backup system, 31.7% had a voluntary system, and 20% had a mandatory backup system.

When we look at different populations served, the trend of “no formal backup system” responses is in decline. The 2014, 2016, and 2018 SoHM reports for hospital medicine groups serving adults, children, and both adults and children, reinforce such trends. The SoHM 2018 report shows 65.6% of hospital medicine groups serving children, 41.6% of groups serving adults, and only 25% of groups serving both adults and children have “no formal backup system.” Our medicine-pediatrics colleagues seem to be leading the trend and have already deduced that, for a solid practice, a backup system is a necessity.

It is also important to see the trend of “no formal backup system” based on geographic area, employer type, academic status, or total number of full-time employees. As we would have predicted, the larger the group the more likely they are to have a backup system. For academic practices a similar trend was seen; they had a higher percentage of some type of backup system year after year.

When it comes to compensation for backup work, four patterns were explored by the SoHM over the years. The most common type of arrangement was “no additional compensation for being on the backup schedule, but additional compensation was provided when called into work.” This kind of arrangement would be easiest to negotiate when the hospitalist and the employer sit across a table. There is nothing at risk for the employer when there isn’t a need, or when there is a need to fill a shift.

The least common method was “additional compensation for being on the backup schedule, but no additional compensation if called into work.” From employers’ perspectives, this is an extra expense and is not ideal for the hospitalist either. In the middle of the pack were “no additional compensation associated with the backup plan” (the second most common model), while the third most common model was “additional compensation for being on the backup schedule, as well as additional compensation if called into work.”

Once you have seen one hospital medicine practice, you have seen one hospital medicine practice. There are different needs for every group, and the backup system – as well its compensation model – has to be designed for it. Thankfully, the SoHM reports reveal the patterns and trends so that we don’t have to reinvent the wheel. For our practice, we decreased a week of clinical service for 2 weeks a year of backup. Every time we activate our backup system, the person coming in receives extra compensation or a similar shift off. In the long run, our backup system didn’t kill us, but rather made us stronger as a group.

Dr. Chadha is interim division chief in the division of hospital medicine at the University of Kentucky HealthCare in Lexington. He actively leads efforts of recruiting, scheduling, practice analysis, and operation of the group. He is a first-time member of the SHM Practice Analysis Committee. Ms. Babb is administrative support associate in the division of hospital medicine at University of Kentucky HealthCare.

It was late 2011. We were a practice of around 20 physicians, and just starting to integrate advanced practice providers into our practice. Our average daily census was about 100 patients and slightly more than 50% of our services were resident services.

My boss, colleague, friend, and mentor – Charles “Chuck” Sargent, MD, and I were on service together early one Saturday morning; Chuck gets a phone call that one of our colleagues was ill. With just 10 physicians working and 10 off, it was an ordeal for Chuck to call all 10 colleagues. Unlike most times, no one could come to moonlight that day. In the end Chuck and I took care of our colleague’s patients.

Yes, it was an exhausting few days, but illness and family needs do not come announced. Now, close to a decade later, we are a practice of 70 physicians and 16 advanced practice providers, our average daily census is about 270 patients, and we have two backup physicians every day – known as Jeopardy-1 and Jeopardy-2. Paternity leave, maternity leave, minor illness, minor trauma, surgery, and family needs are common for our practice. We considered it a good year when we utilized our Jeopardy-1 and Jeopardy-2 for 10% and 1% respectively; and for the past year with a lot of needs, we employed Jeopardy-1 and Jeopardy-2 for 25% and 10%, respectively.

A staffing backup system is a necessary tool for almost every practice. Not having a formal backup system doesn’t mean you don’t need one or you don’t have one – it is just called “no formal backup system.” The Society of Hospital Medicine’s State of Hospital Medicine Reports (SoHM) have been providing data about staffing backup systems every other year. Backup systems come in three flavors. The first system is no formal backup, which means the leaders of the program scramble for coverage every time there is a need. The second is a voluntary backup system in which clinicians volunteer to be on a backup schedule, and the third is a mandatory system in which all or most clinicians are required to be on the backup schedule.

The cumulative data reported in the 2014, 2016, and 2018 SoHM for hospital medicine groups serving adults only, children only, and both adults and children (weighted for number of groups reporting), suggests that 48.3% of respondent practices had no formal backup system, 31.7% had a voluntary system, and 20% had a mandatory backup system.

When we look at different populations served, the trend of “no formal backup system” responses is in decline. The 2014, 2016, and 2018 SoHM reports for hospital medicine groups serving adults, children, and both adults and children, reinforce such trends. The SoHM 2018 report shows 65.6% of hospital medicine groups serving children, 41.6% of groups serving adults, and only 25% of groups serving both adults and children have “no formal backup system.” Our medicine-pediatrics colleagues seem to be leading the trend and have already deduced that, for a solid practice, a backup system is a necessity.

It is also important to see the trend of “no formal backup system” based on geographic area, employer type, academic status, or total number of full-time employees. As we would have predicted, the larger the group the more likely they are to have a backup system. For academic practices a similar trend was seen; they had a higher percentage of some type of backup system year after year.

When it comes to compensation for backup work, four patterns were explored by the SoHM over the years. The most common type of arrangement was “no additional compensation for being on the backup schedule, but additional compensation was provided when called into work.” This kind of arrangement would be easiest to negotiate when the hospitalist and the employer sit across a table. There is nothing at risk for the employer when there isn’t a need, or when there is a need to fill a shift.

The least common method was “additional compensation for being on the backup schedule, but no additional compensation if called into work.” From employers’ perspectives, this is an extra expense and is not ideal for the hospitalist either. In the middle of the pack were “no additional compensation associated with the backup plan” (the second most common model), while the third most common model was “additional compensation for being on the backup schedule, as well as additional compensation if called into work.”

Once you have seen one hospital medicine practice, you have seen one hospital medicine practice. There are different needs for every group, and the backup system – as well its compensation model – has to be designed for it. Thankfully, the SoHM reports reveal the patterns and trends so that we don’t have to reinvent the wheel. For our practice, we decreased a week of clinical service for 2 weeks a year of backup. Every time we activate our backup system, the person coming in receives extra compensation or a similar shift off. In the long run, our backup system didn’t kill us, but rather made us stronger as a group.

Dr. Chadha is interim division chief in the division of hospital medicine at the University of Kentucky HealthCare in Lexington. He actively leads efforts of recruiting, scheduling, practice analysis, and operation of the group. He is a first-time member of the SHM Practice Analysis Committee. Ms. Babb is administrative support associate in the division of hospital medicine at University of Kentucky HealthCare.