User login

Adipose Flap Versus Fascial Sling for Anterior Subcutaneous Transposition of the Ulnar Nerve

Compression of the ulnar nerve at the elbow, also referred to as cubital tunnel syndrome (CuTS), is the second most common peripheral nerve compression syndrome in the upper extremity.1,2 Although the ulnar nerve can be compressed at 5 different sites, including arcade of Struthers, medial intermuscular septum, medial epicondyle, and deep flexor aponeurosis, the cubital tunnel is most commonly affected.3 Patients typically present with paresthesias in the fourth and fifth digits and weakness of hand muscle intrinsics. Activity-related pain or pain at the medial elbow can also occur in more advanced pathology.4 It is estimated that conservative therapy fails and surgical intervention is required in up to 30% of patients with CuTS.1 Surgical approaches range from in situ decompression to transposition techniques, but there is no consensus in the orthopedic community as to which technique offers the best results. In a 2008 meta-analysis, Macadam and colleagues5 found no statistical differences in outcomes among the various surgical approaches. Nevertheless, subcutaneous transposition of the ulnar nerve at the elbow is a popular option.6

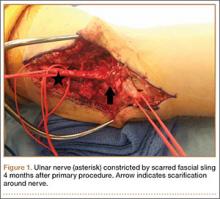

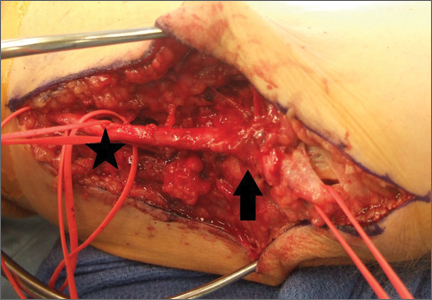

Despite the widespread success of surgical intervention for CuTS, persistent or recurrent pain occurs in 9.9% to 21.0% of cases.7-10 In addition, several investigators have cited perineural scarring as a major cause of recurrent symptoms after primary surgery.11-14 Filippi and colleagues11 noted that patients who required reoperation after primary anterior transposition had “serious epineural fibrosis and fibrosis around the transposed ulnar nerve.” At our institution, we have similarly found that scarring of the fascial sling around the ulnar nerve led to recurrence of CuTS within 4 months after initial surgery (Figure 1).

We therefore prefer to use a vascularized adipose flap to secure the anteriorly transposed ulnar nerve. This flap provides a pliable, vascularized adipose environment for the nerve, which helps reduce nerve adherence and may enhance nerve recovery.15 In the study reported here, we retrospectively reviewed the long-term outcomes of ulnar nerve anterior subcutaneous transposition secured with either an adipose flap or a fascial sling. We hypothesized that patients in the 2 groups (adipose flap, fascial sling) would have equivalent outcomes.

Materials and Methods

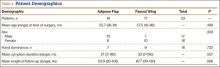

After obtaining institutional review board approval, we reviewed the medical and surgical records of 104 patients (107 limbs) who underwent transposition of the ulnar nerve secured with either an adipose flap (27 limbs) or a fascial sling (80 limbs) over a 14-year period. The fascial sling cohort was used as a comparison group, matched to the adipose flap cohort by sex, age at time of surgery, hand dominance, symptom duration, and length of follow-up (Table 1). Patients were indicated for surgery and were included in the study if they had a history and physical examination consistent with primary CuTS, symptom duration longer than 1 year, and failed conservative management, including activity modification, night splinting, elbow pads, occupational therapy, and home exercise regimen. Electrodiagnostic testing was used at the discretion of the attending surgeon when the diagnosis was not clear from the history and physical examination. All fascial sling procedures were performed at our institution by 1 of 3 fellowship-trained hand surgeons, including Dr. Rosenwasser. The adipose flap modification was performed only by Dr. Rosenwasser. Of the 27 patients in the adipose flap group, 23 underwent surgery for primary CuTS and were included in the study; the other 4 (revision cases) were excluded; 1 patient subsequently died of a cause unrelated to the surgical procedure, and 6 were lost to follow-up. Of the 80 patients in the fascial sling group, 30 underwent surgery for primary CuTS; 5 died before follow-up, and 8 declined to participate.

Thirty-three patients (16 adipose flap, 17 fascial sling) met the inclusion criteria. Of the 16 adipose flap patients, 15 underwent the physical examination and completed the questionnaire, and 1 was interviewed by telephone. Similarly, of the 17 fascial sling patients, 15 underwent the physical examination and completed the questionnaire, and 2 were interviewed by telephone. There were no bilateral cases. Conservative management (activity modification, night splinting, elbow pads, occupational therapy, home exercise) failed in all cases.

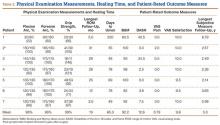

A trained study team member who was not part of the surgical team performed follow-up evaluations using objective outcome measures and subjective questionnaires. Patients were assessed at a mean follow-up of 5.6 years (range, 1.6-15.9 years). Patients completed the DASH (Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand) questionnaire16 and visual analog scales (VASs) for pain, numbness, tingling, and weakness in the ulnar nerve distribution. They also rated the presence of night symptoms that were interfering with sleep. The Modified Bishop Rating Scale (MBRS) was used to quantify patient self-reported data17,18 (Figure 2). The MBRS measures overall satisfaction, symptom improvement, presence of residual symptoms, ability to engage in activities, work capability, and subjective changes in strength and sensibility.

In the physical examinations, we tested for Tinel, Wartenberg, and Froment signs; performed an elbow flexion test; and measured elbow range of motion for flexion and extension as well as forearm pronation and supination. We also evaluated lateral pinch strength and grip strength, using a Jamar hydraulic pinch gauge and a Jamar dynamometer (Therapeutic Equipment Corp) and taking the average of 3 assessments. Fifth-digit abduction strength was graded on a standard muscle strength scale. Two-point discrimination was measured at the middle, ring, and small digits of the operated and contralateral hands.19

Surgical Technique

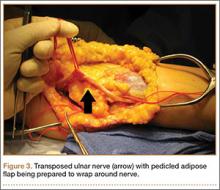

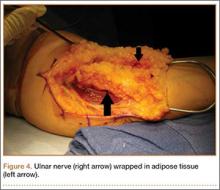

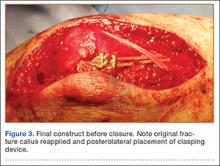

Standard ulnar nerve decompression with anterior subcutaneous transposition and the following modifications were performed on all patients.20 A posteromedial incision parallel to the intermuscular septum was developed and the ulnar nerve identified. Minimizing stripping of the vascular mesentery, the dissection continued along the course of the nerve, and the medial intermuscular septum was excised to prevent secondary compression after transposition. The ulnar nerve was mobilized and transposed anterior to the medial epicondyle (Figure 3). For patients who received the fascial sling, a fascial sleeve was elevated from the flexor-pronator mass and sutured to the edge of the retinaculum securing the nerve. For patients who received the adipose flap, the flap with its vascular pedicle intact was elevated from the subcutaneous tissue of the anterior skin overlying the transposed nerve. The adipose tissue was sharply dissected in half while sufficient subcutaneous tissue was kept between the skin and the flap. A plane was developed based on an anterior adipose pedicle, which included a cutaneous artery and a vein that would supply the vascularized adipose flap. The flap was elevated and wrapped around the nerve without tension while the ulnar nerve was protected from being kinked by the construct. The flap was sutured to the anterior subcutaneous tissue to create a tunnel of adipose tissue surrounding the nerve along its length (Figure 4). The elbow was then flexed and extended to ensure free nerve gliding before wound closure.

The patient was allowed to move the elbow within the bulky dressings immediately after surgery. After 2 weeks, sutures were removed. Formal occupational therapy is not needed for these patients, except in the presence of significant weakness.

Results

As mentioned, the 2 groups were matched on demographics: age at time of surgery, sex, symptom duration, and length of follow-up (Table 1).

For the 16 adipose flap patients (Table 2), mean DASH score was 19.9 (range, 0-71.7). Seven of these patients reported upper extremity pain with a mean VAS score of 1.7 (range, 0-8); 4 patients reported pain in the wrist and fourth and fifth digits; only 1 patient reported pain that occasionally woke the patient from sleep. Constant numbness was present in 6 patients. Four patients reported constant mild tingling in the hand, and 11 reported intermittent tingling. Eleven patients (68.7%) reported operated-arm weakness with a mean VAS score of 3.4 (range, 0-8). In patients who had a physical examination, mean elbow flexion–extension arc of motion was 134° (range, 95°-150°), representing 99% of the motion of the contralateral arm. Mean pronation–supination arc was 174° (range, 150°-180°), accounting for 104% of the contralateral arm. Mean lateral pinch strength was 73% of the contralateral arm, and mean grip strength was 114% of the contralateral arm. The Tinel sign was present in 2 patients, the Froment sign was present in 3 patients, and the elbow flexion test was positive in 2 patients. No patient had a positive Wartenberg sign. On the MBRS, 10 patients had an excellent score, and 6 had a good score.

For the 17 fascial sling patients (Table 2), mean DASH score was 22.7 (range, 0-63.3). Three patients reported upper extremity pain with a mean VAS score of 1.4 (range, 0-7); 3 patients reported pain that occasionally woke them from sleep. Seven patients had constant numbness in the distribution of the ulnar nerve. Two patients had constant paresthesias, and 7 had intermittent paresthesias. Nine patients (52.9%) reported arm weakness with a mean VAS score of 2.5 (range, 0-8). Mean elbow flexion–extension arc of motion was 136° (range, 100°-150°), representing 100% of the contralateral arm. Mean pronation–supination arc was 187° (range, 155°-225°), accounting for 102% of the contralateral arm. Mean lateral pinch strength was 93% of the contralateral arm, and mean grip strength was 80% of the contralateral arm. The Tinel sign was present in 6 patients, the Froment sign in 3 patients, and the Wartenberg sign in 2 patients. The elbow flexion test was positive in 4 patients. On the MBRS, 10 patients had an excellent score, and 7 had a good score.

There was no recurrence of CuTS in either group. One adipose flap patient developed a wound infection that required reoperation.

Discussion

Ulnar neuropathy was described by Magee and Phalen21 in 1949 and termed cubital tunnel syndrome by Feindel and Stratford22 in 1958. Since then, numerous procedures, including in situ decompression, medial epicondylectomy, and endoscopic decompression,23,24 have been advocated for the treatment of this condition. In addition, anterior transposition, which involves securing the ulnar nerve in a submuscular, intramuscular, or subcutaneous sleeve,6 remains a popular option. Despite more than half a century of surgical treatment for this condition, there is no consensus about which procedure offers the best outcomes. Bartels and colleagues8 retrospectively reviewed surgical treatments for CuTS, examining 3148 arms over a 27-year period. They found simple decompression and anterior intramuscular transposition had the best results, followed by medial epicondylectomy and anterior subcutaneous transposition, with anterior submuscular transposition yielding the poorest outcomes. Despite these findings, the operative groups’ recurrence rates remained significant. These results were challenged in a 2008 meta-analysis5 that found no significant difference among simple decompression, subcutaneous transposition, and submuscular transposition and instead demonstrated trends toward better outcomes with anterior transposition. Osterman and Davis7 reported a 5% to 15% rate of unsatisfactory outcomes with anterior subcutaneous transposition, a popular technique used by surgeons at our institution.

The causes for failure or recurrence of ulnar neuropathy after surgical intervention are multifactorial and include preexisting medical conditions and improper operative technique. It is well established that failure to excise all 5 anatomical points of entrapment, or creation of new points of tension during surgery, leads to poor outcomes.12 Nevertheless, the contribution of perineural scarring to postoperative recurrent ulnar neuropathy is currently being recognized: Gabel and Amadio13 described postoperative fibrosis in one-third of their patients with surgically treated recurrent CuTS, Rogers and colleagues14 noted dense perineural fibrosis after intramuscular and subcutaneous transposition procedures, Filippi and colleagues11 cited serious epineural fibrosis and fibrosis around the ulnar nerve as the main findings in their study of 22 patients with recurrent ulnar neuropathy, and Vogel and colleagues12 found that 88% of their patients with persistent CuTS after surgery exhibited perineural scarring.

We think that use of a scar tissue barrier during ulnar nerve transposition reduces the incidence of cicatrix and produces better outcomes—a position largely echoed by the orthopedic community, as fascial, fasciocutaneous, free, and venous flaps have all been used for such purposes.25,26 Vein wrapping has demonstrated good recovery of a nerve after perineural scarring.27 Advocates of intramuscular transposition argue that their technique provides the nerve with a vascularized tunnel, as segmental vascular stripping is an inevitability in transposition. However, this technique increases the incidence of scarring and potential muscle damage.28,29 We think the pedicled adipofascial flap benefits the peripheral nerve by providing a scar tissue barrier and an optimal milieu for vascular regeneration. Kilic and colleagues15 demonstrated the regenerative effects of adipose tissue flaps on peripheral nerves after crush injuries in a rat model, and Strickland and colleagues30 retrospectively examined the effects of hypothenar fat flaps on recalcitrant carpal tunnel syndrome, showing excellent results for this procedure. It is hypothesized that adipose tissue provides not only adipose-derived stem cells but also a rich vascular bed on which nerves will regenerate.

For all patients in the present study, symptoms improved, though the adipose flap and fascial sling groups were not significantly different in their outcomes. We used the MBRS to quantify and compare the groups’ patient-rated outcomes. No statistically significant difference was found between the adipose flap and fascial sling groups. On the MBRS, excellent and good outcomes were reported by 62.5% and 37.5% of the adipose flap patients, respectively, and 59% and 41% of the fascial sling patients (Table 3). Likewise, objective measurements did not show a significant difference between the 2 interventions—indicating that, compared with the current standard of care, adipose flaps are more efficacious in securing the anteriorly transposed nerve.

Complications of the adipose flap technique are consistent with those reported for other techniques for anterior transposition of the ulnar nerve. The most common complication is hematoma, which can be avoided with meticulous hemostasis. Damage of the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve or motor branches to the flexor carpi ulnaris has been reported for the fascial technique (we have not had such outcomes at our institution). Contraindications to the adipofascial technique include insufficient subcutaneous adipose tissue for covering the ulnar nerve.

This study was limited by its retrospective setup, which reduced access to preoperative objective and subjective data. The small sample size also limited our ability to demonstrate the advantageous effects of an adipofascial flap in preventing postoperative perineural scarring.

The adipose flap technique is a viable option for securing the anteriorly transposed ulnar nerve. Outcomes in this study demonstrated an efficacy comparable to that of the fascial sling technique. Symptoms resolve or improve, and the majority of patients are satisfied with long-term surgical outcomes. The adipofascial flap may have additional advantages, as it provides a pliable, vascular fat envelope mimicking the natural fatty environment of peripheral nerves.

1. Latinovic R, Gulliford MC, Hughes RA. Incidence of common compressive neuropathies in primary care. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006;77(2):263-265.

2. Robertson C, Saratsiotis J. A review of compression ulnar neuropathy at the elbow. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2005;28(5):345.

3. Posner MA. Compressive ulnar neuropathies at the elbow: I. Etiology and diagnosis. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1998;6(5):282-288.

4. Piligian G, Herbert R, Hearns M, Dropkin J, Landsbergis P, Cherniack M. Evaluation and management of chronic work-related musculoskeletal disorders of the distal upper extremity. Am J Ind Med. 2000;37(1):75-93.

5. Macadam SA, Gandhi R, Bezuhly M, Lefaivre KA. Simple decompression versus anterior subcutaneous and submuscular transposition of the ulnar nerve for cubital tunnel syndrome: a meta-analysis. J Hand Surg Am. 2008;33(8):1314.e1-e12.

6. Soltani AM, Best MJ, Francis CS, Allan BJ, Panthaki ZJ. Trends in the surgical treatment of cubital tunnel syndrome: an analysis of the National Survey of Ambulatory Surgery database. J Hand Surg Am. 2013;38(8):1551-1556.

7. Osterman AL, Davis CA. Subcutaneous transposition of the ulnar nerve for treatment of cubital tunnel syndrome. Hand Clin. 1996;12(2):421-433.

8. Bartels RH, Menovsky T, Van Overbeeke JJ, Verhagen WI. Surgical management of ulnar nerve compression at the elbow: an analysis of the literature. J Neurosurg. 1998;89(5):722-727.

9. Seradge H, Owen W. Cubital tunnel release with medial epicondylectomy factors influencing the outcome. J Hand Surg Am. 1998;23(3):483-491.

10. Schnabl SM, Kisslinger F, Schramm A, et al. Subjective outcome, neurophysiological investigations, postoperative complications and recurrence rate of partial medial epicondylectomy in cubital tunnel syndrome. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2011;131(8):1027-1033.

11. Filippi R, Charalampaki P, Reisch R, Koch D, Grunert P. Recurrent cubital tunnel syndrome. Etiology and treatment. Minim Invasive Neurosurg. 2001;44(4):197-201.

12. Vogel RB, Nossaman BC, Rayan GM. Revision anterior submuscular transposition of the ulnar nerve for failed subcutaneous transposition. Br J Plast Surg. 2004;57(4):311-316.

13. Gabel GT, Amadio PC. Reoperation for failed decompression of the ulnar nerve in the region of the elbow. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1990;72(2):213-219.

14. Rogers MR, Bergfield TG, Aulicino PL. The failed ulnar nerve transposition. Etiology and treatment. Clin Orthop. 1991;269:193-200.

15. Kilic A, Ojo B, Rajfer RA, et al. Effect of white adipose tissue flap and insulin-like growth factor-1 on nerve regeneration in rats. Microsurgery. 2013;33(5):367-375.

16. Ebersole GC, Davidge K, Damiano M, Mackinnon SE. Validity and responsiveness of the DASH questionnaire as an outcome measure following ulnar nerve transposition for cubital tunnel syndrome. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;132(1):81e-90e.

17. Kleinman WB, Bishop AT. Anterior intramuscular transposition of the ulnar nerve. J Hand Surg Am. 1989;14(6):972-979.

18. Dützmann S, Martin KD, Sobottka S, et al. Open vs retractor-endoscopic in situ decompression of the ulnar nerve in cubital tunnel syndrome: a retrospective cohort study. Neurosurgery. 2013;72(4):605-616.

19. Dellon AL, Mackinnon SE, Crosby PM. Reliability of two-point discrimination measurements. J Hand Surg Am. 1987;12(5 pt 1):693-696.

20. Danoff JR, Lombardi JM, Rosenwasser MP. Use of a pedicled adipose flap as a sling for anterior subcutaneous transposition of the ulnar nerve. J Hand Surg Am. 2014;39(3):552-555.

21. Magee RB, Phalen GS. Tardy ulnar palsy. Am J Surg. 1949;78(4):470-474.

22. Feindel W, Stratford J. Cubital tunnel compression in tardy ulnar palsy. Can Med Assoc J. 1958;78(5):351-353.

23. Tsai TM, Bonczar M, Tsuruta T, Syed SA. A new operative technique: cubital tunnel decompression with endoscopic assistance. Hand Clin. 1995;11(1):71-80.

24. Hoffmann R, Siemionow M. The endoscopic management of cubital tunnel syndrome. J Hand Surg Br. 2006;31(1):23-29.

25. Luchetti R, Riccio M, Papini Zorli I, Fairplay T. Protective coverage of the median nerve using fascial, fasciocutaneous or island flaps. Handchir Mikrochir Plast Chir. 2006;38(5):317-330.

26. Kokkalis ZT, Jain S, Sotereanos DG. Vein wrapping at cubital tunnel for ulnar nerve problems. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19(2):91-97.

27. Masear VR, Colgin S. The treatment of epineural scarring with allograft vein wrapping. Hand Clin. 1996;12(4):773-779.

28. Kleinman WB, Bishop AT. Anterior intramuscular transposition of the ulnar nerve. J Hand Surg Am. 1989;14(6):972-979.

29. Lundborg G. Surgical treatment for ulnar nerve entrapment at the elbow. J Hand Surg Br. 1992;17(3):245-247.

30. Strickland JW, Idler RS, Lourie GM, Plancher KD. The hypothenar fat pad flap for management of recalcitrant carpal tunnel syndrome. J Hand Surg Am. 1996;21(5):840-848.

Compression of the ulnar nerve at the elbow, also referred to as cubital tunnel syndrome (CuTS), is the second most common peripheral nerve compression syndrome in the upper extremity.1,2 Although the ulnar nerve can be compressed at 5 different sites, including arcade of Struthers, medial intermuscular septum, medial epicondyle, and deep flexor aponeurosis, the cubital tunnel is most commonly affected.3 Patients typically present with paresthesias in the fourth and fifth digits and weakness of hand muscle intrinsics. Activity-related pain or pain at the medial elbow can also occur in more advanced pathology.4 It is estimated that conservative therapy fails and surgical intervention is required in up to 30% of patients with CuTS.1 Surgical approaches range from in situ decompression to transposition techniques, but there is no consensus in the orthopedic community as to which technique offers the best results. In a 2008 meta-analysis, Macadam and colleagues5 found no statistical differences in outcomes among the various surgical approaches. Nevertheless, subcutaneous transposition of the ulnar nerve at the elbow is a popular option.6

Despite the widespread success of surgical intervention for CuTS, persistent or recurrent pain occurs in 9.9% to 21.0% of cases.7-10 In addition, several investigators have cited perineural scarring as a major cause of recurrent symptoms after primary surgery.11-14 Filippi and colleagues11 noted that patients who required reoperation after primary anterior transposition had “serious epineural fibrosis and fibrosis around the transposed ulnar nerve.” At our institution, we have similarly found that scarring of the fascial sling around the ulnar nerve led to recurrence of CuTS within 4 months after initial surgery (Figure 1).

We therefore prefer to use a vascularized adipose flap to secure the anteriorly transposed ulnar nerve. This flap provides a pliable, vascularized adipose environment for the nerve, which helps reduce nerve adherence and may enhance nerve recovery.15 In the study reported here, we retrospectively reviewed the long-term outcomes of ulnar nerve anterior subcutaneous transposition secured with either an adipose flap or a fascial sling. We hypothesized that patients in the 2 groups (adipose flap, fascial sling) would have equivalent outcomes.

Materials and Methods

After obtaining institutional review board approval, we reviewed the medical and surgical records of 104 patients (107 limbs) who underwent transposition of the ulnar nerve secured with either an adipose flap (27 limbs) or a fascial sling (80 limbs) over a 14-year period. The fascial sling cohort was used as a comparison group, matched to the adipose flap cohort by sex, age at time of surgery, hand dominance, symptom duration, and length of follow-up (Table 1). Patients were indicated for surgery and were included in the study if they had a history and physical examination consistent with primary CuTS, symptom duration longer than 1 year, and failed conservative management, including activity modification, night splinting, elbow pads, occupational therapy, and home exercise regimen. Electrodiagnostic testing was used at the discretion of the attending surgeon when the diagnosis was not clear from the history and physical examination. All fascial sling procedures were performed at our institution by 1 of 3 fellowship-trained hand surgeons, including Dr. Rosenwasser. The adipose flap modification was performed only by Dr. Rosenwasser. Of the 27 patients in the adipose flap group, 23 underwent surgery for primary CuTS and were included in the study; the other 4 (revision cases) were excluded; 1 patient subsequently died of a cause unrelated to the surgical procedure, and 6 were lost to follow-up. Of the 80 patients in the fascial sling group, 30 underwent surgery for primary CuTS; 5 died before follow-up, and 8 declined to participate.

Thirty-three patients (16 adipose flap, 17 fascial sling) met the inclusion criteria. Of the 16 adipose flap patients, 15 underwent the physical examination and completed the questionnaire, and 1 was interviewed by telephone. Similarly, of the 17 fascial sling patients, 15 underwent the physical examination and completed the questionnaire, and 2 were interviewed by telephone. There were no bilateral cases. Conservative management (activity modification, night splinting, elbow pads, occupational therapy, home exercise) failed in all cases.

A trained study team member who was not part of the surgical team performed follow-up evaluations using objective outcome measures and subjective questionnaires. Patients were assessed at a mean follow-up of 5.6 years (range, 1.6-15.9 years). Patients completed the DASH (Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand) questionnaire16 and visual analog scales (VASs) for pain, numbness, tingling, and weakness in the ulnar nerve distribution. They also rated the presence of night symptoms that were interfering with sleep. The Modified Bishop Rating Scale (MBRS) was used to quantify patient self-reported data17,18 (Figure 2). The MBRS measures overall satisfaction, symptom improvement, presence of residual symptoms, ability to engage in activities, work capability, and subjective changes in strength and sensibility.

In the physical examinations, we tested for Tinel, Wartenberg, and Froment signs; performed an elbow flexion test; and measured elbow range of motion for flexion and extension as well as forearm pronation and supination. We also evaluated lateral pinch strength and grip strength, using a Jamar hydraulic pinch gauge and a Jamar dynamometer (Therapeutic Equipment Corp) and taking the average of 3 assessments. Fifth-digit abduction strength was graded on a standard muscle strength scale. Two-point discrimination was measured at the middle, ring, and small digits of the operated and contralateral hands.19

Surgical Technique

Standard ulnar nerve decompression with anterior subcutaneous transposition and the following modifications were performed on all patients.20 A posteromedial incision parallel to the intermuscular septum was developed and the ulnar nerve identified. Minimizing stripping of the vascular mesentery, the dissection continued along the course of the nerve, and the medial intermuscular septum was excised to prevent secondary compression after transposition. The ulnar nerve was mobilized and transposed anterior to the medial epicondyle (Figure 3). For patients who received the fascial sling, a fascial sleeve was elevated from the flexor-pronator mass and sutured to the edge of the retinaculum securing the nerve. For patients who received the adipose flap, the flap with its vascular pedicle intact was elevated from the subcutaneous tissue of the anterior skin overlying the transposed nerve. The adipose tissue was sharply dissected in half while sufficient subcutaneous tissue was kept between the skin and the flap. A plane was developed based on an anterior adipose pedicle, which included a cutaneous artery and a vein that would supply the vascularized adipose flap. The flap was elevated and wrapped around the nerve without tension while the ulnar nerve was protected from being kinked by the construct. The flap was sutured to the anterior subcutaneous tissue to create a tunnel of adipose tissue surrounding the nerve along its length (Figure 4). The elbow was then flexed and extended to ensure free nerve gliding before wound closure.

The patient was allowed to move the elbow within the bulky dressings immediately after surgery. After 2 weeks, sutures were removed. Formal occupational therapy is not needed for these patients, except in the presence of significant weakness.

Results

As mentioned, the 2 groups were matched on demographics: age at time of surgery, sex, symptom duration, and length of follow-up (Table 1).

For the 16 adipose flap patients (Table 2), mean DASH score was 19.9 (range, 0-71.7). Seven of these patients reported upper extremity pain with a mean VAS score of 1.7 (range, 0-8); 4 patients reported pain in the wrist and fourth and fifth digits; only 1 patient reported pain that occasionally woke the patient from sleep. Constant numbness was present in 6 patients. Four patients reported constant mild tingling in the hand, and 11 reported intermittent tingling. Eleven patients (68.7%) reported operated-arm weakness with a mean VAS score of 3.4 (range, 0-8). In patients who had a physical examination, mean elbow flexion–extension arc of motion was 134° (range, 95°-150°), representing 99% of the motion of the contralateral arm. Mean pronation–supination arc was 174° (range, 150°-180°), accounting for 104% of the contralateral arm. Mean lateral pinch strength was 73% of the contralateral arm, and mean grip strength was 114% of the contralateral arm. The Tinel sign was present in 2 patients, the Froment sign was present in 3 patients, and the elbow flexion test was positive in 2 patients. No patient had a positive Wartenberg sign. On the MBRS, 10 patients had an excellent score, and 6 had a good score.

For the 17 fascial sling patients (Table 2), mean DASH score was 22.7 (range, 0-63.3). Three patients reported upper extremity pain with a mean VAS score of 1.4 (range, 0-7); 3 patients reported pain that occasionally woke them from sleep. Seven patients had constant numbness in the distribution of the ulnar nerve. Two patients had constant paresthesias, and 7 had intermittent paresthesias. Nine patients (52.9%) reported arm weakness with a mean VAS score of 2.5 (range, 0-8). Mean elbow flexion–extension arc of motion was 136° (range, 100°-150°), representing 100% of the contralateral arm. Mean pronation–supination arc was 187° (range, 155°-225°), accounting for 102% of the contralateral arm. Mean lateral pinch strength was 93% of the contralateral arm, and mean grip strength was 80% of the contralateral arm. The Tinel sign was present in 6 patients, the Froment sign in 3 patients, and the Wartenberg sign in 2 patients. The elbow flexion test was positive in 4 patients. On the MBRS, 10 patients had an excellent score, and 7 had a good score.

There was no recurrence of CuTS in either group. One adipose flap patient developed a wound infection that required reoperation.

Discussion

Ulnar neuropathy was described by Magee and Phalen21 in 1949 and termed cubital tunnel syndrome by Feindel and Stratford22 in 1958. Since then, numerous procedures, including in situ decompression, medial epicondylectomy, and endoscopic decompression,23,24 have been advocated for the treatment of this condition. In addition, anterior transposition, which involves securing the ulnar nerve in a submuscular, intramuscular, or subcutaneous sleeve,6 remains a popular option. Despite more than half a century of surgical treatment for this condition, there is no consensus about which procedure offers the best outcomes. Bartels and colleagues8 retrospectively reviewed surgical treatments for CuTS, examining 3148 arms over a 27-year period. They found simple decompression and anterior intramuscular transposition had the best results, followed by medial epicondylectomy and anterior subcutaneous transposition, with anterior submuscular transposition yielding the poorest outcomes. Despite these findings, the operative groups’ recurrence rates remained significant. These results were challenged in a 2008 meta-analysis5 that found no significant difference among simple decompression, subcutaneous transposition, and submuscular transposition and instead demonstrated trends toward better outcomes with anterior transposition. Osterman and Davis7 reported a 5% to 15% rate of unsatisfactory outcomes with anterior subcutaneous transposition, a popular technique used by surgeons at our institution.

The causes for failure or recurrence of ulnar neuropathy after surgical intervention are multifactorial and include preexisting medical conditions and improper operative technique. It is well established that failure to excise all 5 anatomical points of entrapment, or creation of new points of tension during surgery, leads to poor outcomes.12 Nevertheless, the contribution of perineural scarring to postoperative recurrent ulnar neuropathy is currently being recognized: Gabel and Amadio13 described postoperative fibrosis in one-third of their patients with surgically treated recurrent CuTS, Rogers and colleagues14 noted dense perineural fibrosis after intramuscular and subcutaneous transposition procedures, Filippi and colleagues11 cited serious epineural fibrosis and fibrosis around the ulnar nerve as the main findings in their study of 22 patients with recurrent ulnar neuropathy, and Vogel and colleagues12 found that 88% of their patients with persistent CuTS after surgery exhibited perineural scarring.

We think that use of a scar tissue barrier during ulnar nerve transposition reduces the incidence of cicatrix and produces better outcomes—a position largely echoed by the orthopedic community, as fascial, fasciocutaneous, free, and venous flaps have all been used for such purposes.25,26 Vein wrapping has demonstrated good recovery of a nerve after perineural scarring.27 Advocates of intramuscular transposition argue that their technique provides the nerve with a vascularized tunnel, as segmental vascular stripping is an inevitability in transposition. However, this technique increases the incidence of scarring and potential muscle damage.28,29 We think the pedicled adipofascial flap benefits the peripheral nerve by providing a scar tissue barrier and an optimal milieu for vascular regeneration. Kilic and colleagues15 demonstrated the regenerative effects of adipose tissue flaps on peripheral nerves after crush injuries in a rat model, and Strickland and colleagues30 retrospectively examined the effects of hypothenar fat flaps on recalcitrant carpal tunnel syndrome, showing excellent results for this procedure. It is hypothesized that adipose tissue provides not only adipose-derived stem cells but also a rich vascular bed on which nerves will regenerate.

For all patients in the present study, symptoms improved, though the adipose flap and fascial sling groups were not significantly different in their outcomes. We used the MBRS to quantify and compare the groups’ patient-rated outcomes. No statistically significant difference was found between the adipose flap and fascial sling groups. On the MBRS, excellent and good outcomes were reported by 62.5% and 37.5% of the adipose flap patients, respectively, and 59% and 41% of the fascial sling patients (Table 3). Likewise, objective measurements did not show a significant difference between the 2 interventions—indicating that, compared with the current standard of care, adipose flaps are more efficacious in securing the anteriorly transposed nerve.

Complications of the adipose flap technique are consistent with those reported for other techniques for anterior transposition of the ulnar nerve. The most common complication is hematoma, which can be avoided with meticulous hemostasis. Damage of the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve or motor branches to the flexor carpi ulnaris has been reported for the fascial technique (we have not had such outcomes at our institution). Contraindications to the adipofascial technique include insufficient subcutaneous adipose tissue for covering the ulnar nerve.

This study was limited by its retrospective setup, which reduced access to preoperative objective and subjective data. The small sample size also limited our ability to demonstrate the advantageous effects of an adipofascial flap in preventing postoperative perineural scarring.

The adipose flap technique is a viable option for securing the anteriorly transposed ulnar nerve. Outcomes in this study demonstrated an efficacy comparable to that of the fascial sling technique. Symptoms resolve or improve, and the majority of patients are satisfied with long-term surgical outcomes. The adipofascial flap may have additional advantages, as it provides a pliable, vascular fat envelope mimicking the natural fatty environment of peripheral nerves.

Compression of the ulnar nerve at the elbow, also referred to as cubital tunnel syndrome (CuTS), is the second most common peripheral nerve compression syndrome in the upper extremity.1,2 Although the ulnar nerve can be compressed at 5 different sites, including arcade of Struthers, medial intermuscular septum, medial epicondyle, and deep flexor aponeurosis, the cubital tunnel is most commonly affected.3 Patients typically present with paresthesias in the fourth and fifth digits and weakness of hand muscle intrinsics. Activity-related pain or pain at the medial elbow can also occur in more advanced pathology.4 It is estimated that conservative therapy fails and surgical intervention is required in up to 30% of patients with CuTS.1 Surgical approaches range from in situ decompression to transposition techniques, but there is no consensus in the orthopedic community as to which technique offers the best results. In a 2008 meta-analysis, Macadam and colleagues5 found no statistical differences in outcomes among the various surgical approaches. Nevertheless, subcutaneous transposition of the ulnar nerve at the elbow is a popular option.6

Despite the widespread success of surgical intervention for CuTS, persistent or recurrent pain occurs in 9.9% to 21.0% of cases.7-10 In addition, several investigators have cited perineural scarring as a major cause of recurrent symptoms after primary surgery.11-14 Filippi and colleagues11 noted that patients who required reoperation after primary anterior transposition had “serious epineural fibrosis and fibrosis around the transposed ulnar nerve.” At our institution, we have similarly found that scarring of the fascial sling around the ulnar nerve led to recurrence of CuTS within 4 months after initial surgery (Figure 1).

We therefore prefer to use a vascularized adipose flap to secure the anteriorly transposed ulnar nerve. This flap provides a pliable, vascularized adipose environment for the nerve, which helps reduce nerve adherence and may enhance nerve recovery.15 In the study reported here, we retrospectively reviewed the long-term outcomes of ulnar nerve anterior subcutaneous transposition secured with either an adipose flap or a fascial sling. We hypothesized that patients in the 2 groups (adipose flap, fascial sling) would have equivalent outcomes.

Materials and Methods

After obtaining institutional review board approval, we reviewed the medical and surgical records of 104 patients (107 limbs) who underwent transposition of the ulnar nerve secured with either an adipose flap (27 limbs) or a fascial sling (80 limbs) over a 14-year period. The fascial sling cohort was used as a comparison group, matched to the adipose flap cohort by sex, age at time of surgery, hand dominance, symptom duration, and length of follow-up (Table 1). Patients were indicated for surgery and were included in the study if they had a history and physical examination consistent with primary CuTS, symptom duration longer than 1 year, and failed conservative management, including activity modification, night splinting, elbow pads, occupational therapy, and home exercise regimen. Electrodiagnostic testing was used at the discretion of the attending surgeon when the diagnosis was not clear from the history and physical examination. All fascial sling procedures were performed at our institution by 1 of 3 fellowship-trained hand surgeons, including Dr. Rosenwasser. The adipose flap modification was performed only by Dr. Rosenwasser. Of the 27 patients in the adipose flap group, 23 underwent surgery for primary CuTS and were included in the study; the other 4 (revision cases) were excluded; 1 patient subsequently died of a cause unrelated to the surgical procedure, and 6 were lost to follow-up. Of the 80 patients in the fascial sling group, 30 underwent surgery for primary CuTS; 5 died before follow-up, and 8 declined to participate.

Thirty-three patients (16 adipose flap, 17 fascial sling) met the inclusion criteria. Of the 16 adipose flap patients, 15 underwent the physical examination and completed the questionnaire, and 1 was interviewed by telephone. Similarly, of the 17 fascial sling patients, 15 underwent the physical examination and completed the questionnaire, and 2 were interviewed by telephone. There were no bilateral cases. Conservative management (activity modification, night splinting, elbow pads, occupational therapy, home exercise) failed in all cases.

A trained study team member who was not part of the surgical team performed follow-up evaluations using objective outcome measures and subjective questionnaires. Patients were assessed at a mean follow-up of 5.6 years (range, 1.6-15.9 years). Patients completed the DASH (Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand) questionnaire16 and visual analog scales (VASs) for pain, numbness, tingling, and weakness in the ulnar nerve distribution. They also rated the presence of night symptoms that were interfering with sleep. The Modified Bishop Rating Scale (MBRS) was used to quantify patient self-reported data17,18 (Figure 2). The MBRS measures overall satisfaction, symptom improvement, presence of residual symptoms, ability to engage in activities, work capability, and subjective changes in strength and sensibility.

In the physical examinations, we tested for Tinel, Wartenberg, and Froment signs; performed an elbow flexion test; and measured elbow range of motion for flexion and extension as well as forearm pronation and supination. We also evaluated lateral pinch strength and grip strength, using a Jamar hydraulic pinch gauge and a Jamar dynamometer (Therapeutic Equipment Corp) and taking the average of 3 assessments. Fifth-digit abduction strength was graded on a standard muscle strength scale. Two-point discrimination was measured at the middle, ring, and small digits of the operated and contralateral hands.19

Surgical Technique

Standard ulnar nerve decompression with anterior subcutaneous transposition and the following modifications were performed on all patients.20 A posteromedial incision parallel to the intermuscular septum was developed and the ulnar nerve identified. Minimizing stripping of the vascular mesentery, the dissection continued along the course of the nerve, and the medial intermuscular septum was excised to prevent secondary compression after transposition. The ulnar nerve was mobilized and transposed anterior to the medial epicondyle (Figure 3). For patients who received the fascial sling, a fascial sleeve was elevated from the flexor-pronator mass and sutured to the edge of the retinaculum securing the nerve. For patients who received the adipose flap, the flap with its vascular pedicle intact was elevated from the subcutaneous tissue of the anterior skin overlying the transposed nerve. The adipose tissue was sharply dissected in half while sufficient subcutaneous tissue was kept between the skin and the flap. A plane was developed based on an anterior adipose pedicle, which included a cutaneous artery and a vein that would supply the vascularized adipose flap. The flap was elevated and wrapped around the nerve without tension while the ulnar nerve was protected from being kinked by the construct. The flap was sutured to the anterior subcutaneous tissue to create a tunnel of adipose tissue surrounding the nerve along its length (Figure 4). The elbow was then flexed and extended to ensure free nerve gliding before wound closure.

The patient was allowed to move the elbow within the bulky dressings immediately after surgery. After 2 weeks, sutures were removed. Formal occupational therapy is not needed for these patients, except in the presence of significant weakness.

Results

As mentioned, the 2 groups were matched on demographics: age at time of surgery, sex, symptom duration, and length of follow-up (Table 1).

For the 16 adipose flap patients (Table 2), mean DASH score was 19.9 (range, 0-71.7). Seven of these patients reported upper extremity pain with a mean VAS score of 1.7 (range, 0-8); 4 patients reported pain in the wrist and fourth and fifth digits; only 1 patient reported pain that occasionally woke the patient from sleep. Constant numbness was present in 6 patients. Four patients reported constant mild tingling in the hand, and 11 reported intermittent tingling. Eleven patients (68.7%) reported operated-arm weakness with a mean VAS score of 3.4 (range, 0-8). In patients who had a physical examination, mean elbow flexion–extension arc of motion was 134° (range, 95°-150°), representing 99% of the motion of the contralateral arm. Mean pronation–supination arc was 174° (range, 150°-180°), accounting for 104% of the contralateral arm. Mean lateral pinch strength was 73% of the contralateral arm, and mean grip strength was 114% of the contralateral arm. The Tinel sign was present in 2 patients, the Froment sign was present in 3 patients, and the elbow flexion test was positive in 2 patients. No patient had a positive Wartenberg sign. On the MBRS, 10 patients had an excellent score, and 6 had a good score.

For the 17 fascial sling patients (Table 2), mean DASH score was 22.7 (range, 0-63.3). Three patients reported upper extremity pain with a mean VAS score of 1.4 (range, 0-7); 3 patients reported pain that occasionally woke them from sleep. Seven patients had constant numbness in the distribution of the ulnar nerve. Two patients had constant paresthesias, and 7 had intermittent paresthesias. Nine patients (52.9%) reported arm weakness with a mean VAS score of 2.5 (range, 0-8). Mean elbow flexion–extension arc of motion was 136° (range, 100°-150°), representing 100% of the contralateral arm. Mean pronation–supination arc was 187° (range, 155°-225°), accounting for 102% of the contralateral arm. Mean lateral pinch strength was 93% of the contralateral arm, and mean grip strength was 80% of the contralateral arm. The Tinel sign was present in 6 patients, the Froment sign in 3 patients, and the Wartenberg sign in 2 patients. The elbow flexion test was positive in 4 patients. On the MBRS, 10 patients had an excellent score, and 7 had a good score.

There was no recurrence of CuTS in either group. One adipose flap patient developed a wound infection that required reoperation.

Discussion

Ulnar neuropathy was described by Magee and Phalen21 in 1949 and termed cubital tunnel syndrome by Feindel and Stratford22 in 1958. Since then, numerous procedures, including in situ decompression, medial epicondylectomy, and endoscopic decompression,23,24 have been advocated for the treatment of this condition. In addition, anterior transposition, which involves securing the ulnar nerve in a submuscular, intramuscular, or subcutaneous sleeve,6 remains a popular option. Despite more than half a century of surgical treatment for this condition, there is no consensus about which procedure offers the best outcomes. Bartels and colleagues8 retrospectively reviewed surgical treatments for CuTS, examining 3148 arms over a 27-year period. They found simple decompression and anterior intramuscular transposition had the best results, followed by medial epicondylectomy and anterior subcutaneous transposition, with anterior submuscular transposition yielding the poorest outcomes. Despite these findings, the operative groups’ recurrence rates remained significant. These results were challenged in a 2008 meta-analysis5 that found no significant difference among simple decompression, subcutaneous transposition, and submuscular transposition and instead demonstrated trends toward better outcomes with anterior transposition. Osterman and Davis7 reported a 5% to 15% rate of unsatisfactory outcomes with anterior subcutaneous transposition, a popular technique used by surgeons at our institution.

The causes for failure or recurrence of ulnar neuropathy after surgical intervention are multifactorial and include preexisting medical conditions and improper operative technique. It is well established that failure to excise all 5 anatomical points of entrapment, or creation of new points of tension during surgery, leads to poor outcomes.12 Nevertheless, the contribution of perineural scarring to postoperative recurrent ulnar neuropathy is currently being recognized: Gabel and Amadio13 described postoperative fibrosis in one-third of their patients with surgically treated recurrent CuTS, Rogers and colleagues14 noted dense perineural fibrosis after intramuscular and subcutaneous transposition procedures, Filippi and colleagues11 cited serious epineural fibrosis and fibrosis around the ulnar nerve as the main findings in their study of 22 patients with recurrent ulnar neuropathy, and Vogel and colleagues12 found that 88% of their patients with persistent CuTS after surgery exhibited perineural scarring.

We think that use of a scar tissue barrier during ulnar nerve transposition reduces the incidence of cicatrix and produces better outcomes—a position largely echoed by the orthopedic community, as fascial, fasciocutaneous, free, and venous flaps have all been used for such purposes.25,26 Vein wrapping has demonstrated good recovery of a nerve after perineural scarring.27 Advocates of intramuscular transposition argue that their technique provides the nerve with a vascularized tunnel, as segmental vascular stripping is an inevitability in transposition. However, this technique increases the incidence of scarring and potential muscle damage.28,29 We think the pedicled adipofascial flap benefits the peripheral nerve by providing a scar tissue barrier and an optimal milieu for vascular regeneration. Kilic and colleagues15 demonstrated the regenerative effects of adipose tissue flaps on peripheral nerves after crush injuries in a rat model, and Strickland and colleagues30 retrospectively examined the effects of hypothenar fat flaps on recalcitrant carpal tunnel syndrome, showing excellent results for this procedure. It is hypothesized that adipose tissue provides not only adipose-derived stem cells but also a rich vascular bed on which nerves will regenerate.

For all patients in the present study, symptoms improved, though the adipose flap and fascial sling groups were not significantly different in their outcomes. We used the MBRS to quantify and compare the groups’ patient-rated outcomes. No statistically significant difference was found between the adipose flap and fascial sling groups. On the MBRS, excellent and good outcomes were reported by 62.5% and 37.5% of the adipose flap patients, respectively, and 59% and 41% of the fascial sling patients (Table 3). Likewise, objective measurements did not show a significant difference between the 2 interventions—indicating that, compared with the current standard of care, adipose flaps are more efficacious in securing the anteriorly transposed nerve.

Complications of the adipose flap technique are consistent with those reported for other techniques for anterior transposition of the ulnar nerve. The most common complication is hematoma, which can be avoided with meticulous hemostasis. Damage of the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve or motor branches to the flexor carpi ulnaris has been reported for the fascial technique (we have not had such outcomes at our institution). Contraindications to the adipofascial technique include insufficient subcutaneous adipose tissue for covering the ulnar nerve.

This study was limited by its retrospective setup, which reduced access to preoperative objective and subjective data. The small sample size also limited our ability to demonstrate the advantageous effects of an adipofascial flap in preventing postoperative perineural scarring.

The adipose flap technique is a viable option for securing the anteriorly transposed ulnar nerve. Outcomes in this study demonstrated an efficacy comparable to that of the fascial sling technique. Symptoms resolve or improve, and the majority of patients are satisfied with long-term surgical outcomes. The adipofascial flap may have additional advantages, as it provides a pliable, vascular fat envelope mimicking the natural fatty environment of peripheral nerves.

1. Latinovic R, Gulliford MC, Hughes RA. Incidence of common compressive neuropathies in primary care. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006;77(2):263-265.

2. Robertson C, Saratsiotis J. A review of compression ulnar neuropathy at the elbow. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2005;28(5):345.

3. Posner MA. Compressive ulnar neuropathies at the elbow: I. Etiology and diagnosis. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1998;6(5):282-288.

4. Piligian G, Herbert R, Hearns M, Dropkin J, Landsbergis P, Cherniack M. Evaluation and management of chronic work-related musculoskeletal disorders of the distal upper extremity. Am J Ind Med. 2000;37(1):75-93.

5. Macadam SA, Gandhi R, Bezuhly M, Lefaivre KA. Simple decompression versus anterior subcutaneous and submuscular transposition of the ulnar nerve for cubital tunnel syndrome: a meta-analysis. J Hand Surg Am. 2008;33(8):1314.e1-e12.

6. Soltani AM, Best MJ, Francis CS, Allan BJ, Panthaki ZJ. Trends in the surgical treatment of cubital tunnel syndrome: an analysis of the National Survey of Ambulatory Surgery database. J Hand Surg Am. 2013;38(8):1551-1556.

7. Osterman AL, Davis CA. Subcutaneous transposition of the ulnar nerve for treatment of cubital tunnel syndrome. Hand Clin. 1996;12(2):421-433.

8. Bartels RH, Menovsky T, Van Overbeeke JJ, Verhagen WI. Surgical management of ulnar nerve compression at the elbow: an analysis of the literature. J Neurosurg. 1998;89(5):722-727.

9. Seradge H, Owen W. Cubital tunnel release with medial epicondylectomy factors influencing the outcome. J Hand Surg Am. 1998;23(3):483-491.

10. Schnabl SM, Kisslinger F, Schramm A, et al. Subjective outcome, neurophysiological investigations, postoperative complications and recurrence rate of partial medial epicondylectomy in cubital tunnel syndrome. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2011;131(8):1027-1033.

11. Filippi R, Charalampaki P, Reisch R, Koch D, Grunert P. Recurrent cubital tunnel syndrome. Etiology and treatment. Minim Invasive Neurosurg. 2001;44(4):197-201.

12. Vogel RB, Nossaman BC, Rayan GM. Revision anterior submuscular transposition of the ulnar nerve for failed subcutaneous transposition. Br J Plast Surg. 2004;57(4):311-316.

13. Gabel GT, Amadio PC. Reoperation for failed decompression of the ulnar nerve in the region of the elbow. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1990;72(2):213-219.

14. Rogers MR, Bergfield TG, Aulicino PL. The failed ulnar nerve transposition. Etiology and treatment. Clin Orthop. 1991;269:193-200.

15. Kilic A, Ojo B, Rajfer RA, et al. Effect of white adipose tissue flap and insulin-like growth factor-1 on nerve regeneration in rats. Microsurgery. 2013;33(5):367-375.

16. Ebersole GC, Davidge K, Damiano M, Mackinnon SE. Validity and responsiveness of the DASH questionnaire as an outcome measure following ulnar nerve transposition for cubital tunnel syndrome. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;132(1):81e-90e.

17. Kleinman WB, Bishop AT. Anterior intramuscular transposition of the ulnar nerve. J Hand Surg Am. 1989;14(6):972-979.

18. Dützmann S, Martin KD, Sobottka S, et al. Open vs retractor-endoscopic in situ decompression of the ulnar nerve in cubital tunnel syndrome: a retrospective cohort study. Neurosurgery. 2013;72(4):605-616.

19. Dellon AL, Mackinnon SE, Crosby PM. Reliability of two-point discrimination measurements. J Hand Surg Am. 1987;12(5 pt 1):693-696.

20. Danoff JR, Lombardi JM, Rosenwasser MP. Use of a pedicled adipose flap as a sling for anterior subcutaneous transposition of the ulnar nerve. J Hand Surg Am. 2014;39(3):552-555.

21. Magee RB, Phalen GS. Tardy ulnar palsy. Am J Surg. 1949;78(4):470-474.

22. Feindel W, Stratford J. Cubital tunnel compression in tardy ulnar palsy. Can Med Assoc J. 1958;78(5):351-353.

23. Tsai TM, Bonczar M, Tsuruta T, Syed SA. A new operative technique: cubital tunnel decompression with endoscopic assistance. Hand Clin. 1995;11(1):71-80.

24. Hoffmann R, Siemionow M. The endoscopic management of cubital tunnel syndrome. J Hand Surg Br. 2006;31(1):23-29.

25. Luchetti R, Riccio M, Papini Zorli I, Fairplay T. Protective coverage of the median nerve using fascial, fasciocutaneous or island flaps. Handchir Mikrochir Plast Chir. 2006;38(5):317-330.

26. Kokkalis ZT, Jain S, Sotereanos DG. Vein wrapping at cubital tunnel for ulnar nerve problems. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19(2):91-97.

27. Masear VR, Colgin S. The treatment of epineural scarring with allograft vein wrapping. Hand Clin. 1996;12(4):773-779.

28. Kleinman WB, Bishop AT. Anterior intramuscular transposition of the ulnar nerve. J Hand Surg Am. 1989;14(6):972-979.

29. Lundborg G. Surgical treatment for ulnar nerve entrapment at the elbow. J Hand Surg Br. 1992;17(3):245-247.

30. Strickland JW, Idler RS, Lourie GM, Plancher KD. The hypothenar fat pad flap for management of recalcitrant carpal tunnel syndrome. J Hand Surg Am. 1996;21(5):840-848.

1. Latinovic R, Gulliford MC, Hughes RA. Incidence of common compressive neuropathies in primary care. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006;77(2):263-265.

2. Robertson C, Saratsiotis J. A review of compression ulnar neuropathy at the elbow. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2005;28(5):345.

3. Posner MA. Compressive ulnar neuropathies at the elbow: I. Etiology and diagnosis. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1998;6(5):282-288.

4. Piligian G, Herbert R, Hearns M, Dropkin J, Landsbergis P, Cherniack M. Evaluation and management of chronic work-related musculoskeletal disorders of the distal upper extremity. Am J Ind Med. 2000;37(1):75-93.

5. Macadam SA, Gandhi R, Bezuhly M, Lefaivre KA. Simple decompression versus anterior subcutaneous and submuscular transposition of the ulnar nerve for cubital tunnel syndrome: a meta-analysis. J Hand Surg Am. 2008;33(8):1314.e1-e12.

6. Soltani AM, Best MJ, Francis CS, Allan BJ, Panthaki ZJ. Trends in the surgical treatment of cubital tunnel syndrome: an analysis of the National Survey of Ambulatory Surgery database. J Hand Surg Am. 2013;38(8):1551-1556.

7. Osterman AL, Davis CA. Subcutaneous transposition of the ulnar nerve for treatment of cubital tunnel syndrome. Hand Clin. 1996;12(2):421-433.

8. Bartels RH, Menovsky T, Van Overbeeke JJ, Verhagen WI. Surgical management of ulnar nerve compression at the elbow: an analysis of the literature. J Neurosurg. 1998;89(5):722-727.

9. Seradge H, Owen W. Cubital tunnel release with medial epicondylectomy factors influencing the outcome. J Hand Surg Am. 1998;23(3):483-491.

10. Schnabl SM, Kisslinger F, Schramm A, et al. Subjective outcome, neurophysiological investigations, postoperative complications and recurrence rate of partial medial epicondylectomy in cubital tunnel syndrome. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2011;131(8):1027-1033.

11. Filippi R, Charalampaki P, Reisch R, Koch D, Grunert P. Recurrent cubital tunnel syndrome. Etiology and treatment. Minim Invasive Neurosurg. 2001;44(4):197-201.

12. Vogel RB, Nossaman BC, Rayan GM. Revision anterior submuscular transposition of the ulnar nerve for failed subcutaneous transposition. Br J Plast Surg. 2004;57(4):311-316.

13. Gabel GT, Amadio PC. Reoperation for failed decompression of the ulnar nerve in the region of the elbow. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1990;72(2):213-219.

14. Rogers MR, Bergfield TG, Aulicino PL. The failed ulnar nerve transposition. Etiology and treatment. Clin Orthop. 1991;269:193-200.

15. Kilic A, Ojo B, Rajfer RA, et al. Effect of white adipose tissue flap and insulin-like growth factor-1 on nerve regeneration in rats. Microsurgery. 2013;33(5):367-375.

16. Ebersole GC, Davidge K, Damiano M, Mackinnon SE. Validity and responsiveness of the DASH questionnaire as an outcome measure following ulnar nerve transposition for cubital tunnel syndrome. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;132(1):81e-90e.

17. Kleinman WB, Bishop AT. Anterior intramuscular transposition of the ulnar nerve. J Hand Surg Am. 1989;14(6):972-979.

18. Dützmann S, Martin KD, Sobottka S, et al. Open vs retractor-endoscopic in situ decompression of the ulnar nerve in cubital tunnel syndrome: a retrospective cohort study. Neurosurgery. 2013;72(4):605-616.

19. Dellon AL, Mackinnon SE, Crosby PM. Reliability of two-point discrimination measurements. J Hand Surg Am. 1987;12(5 pt 1):693-696.

20. Danoff JR, Lombardi JM, Rosenwasser MP. Use of a pedicled adipose flap as a sling for anterior subcutaneous transposition of the ulnar nerve. J Hand Surg Am. 2014;39(3):552-555.

21. Magee RB, Phalen GS. Tardy ulnar palsy. Am J Surg. 1949;78(4):470-474.

22. Feindel W, Stratford J. Cubital tunnel compression in tardy ulnar palsy. Can Med Assoc J. 1958;78(5):351-353.

23. Tsai TM, Bonczar M, Tsuruta T, Syed SA. A new operative technique: cubital tunnel decompression with endoscopic assistance. Hand Clin. 1995;11(1):71-80.

24. Hoffmann R, Siemionow M. The endoscopic management of cubital tunnel syndrome. J Hand Surg Br. 2006;31(1):23-29.

25. Luchetti R, Riccio M, Papini Zorli I, Fairplay T. Protective coverage of the median nerve using fascial, fasciocutaneous or island flaps. Handchir Mikrochir Plast Chir. 2006;38(5):317-330.

26. Kokkalis ZT, Jain S, Sotereanos DG. Vein wrapping at cubital tunnel for ulnar nerve problems. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19(2):91-97.

27. Masear VR, Colgin S. The treatment of epineural scarring with allograft vein wrapping. Hand Clin. 1996;12(4):773-779.

28. Kleinman WB, Bishop AT. Anterior intramuscular transposition of the ulnar nerve. J Hand Surg Am. 1989;14(6):972-979.

29. Lundborg G. Surgical treatment for ulnar nerve entrapment at the elbow. J Hand Surg Br. 1992;17(3):245-247.

30. Strickland JW, Idler RS, Lourie GM, Plancher KD. The hypothenar fat pad flap for management of recalcitrant carpal tunnel syndrome. J Hand Surg Am. 1996;21(5):840-848.

Intra-articular Olecranon Fracture Fixed with an Iso-Elastic Tension Band

Surgical technique using isoelastic tension band for treatment of olecranon fractures.

To read the authors' full article click here.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Surgical technique using isoelastic tension band for treatment of olecranon fractures.

To read the authors' full article click here.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Surgical technique using isoelastic tension band for treatment of olecranon fractures.

To read the authors' full article click here.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Technique Using Isoelastic Tension Band for Treatment of Olecranon Fractures

Olecranon fractures are relatively common in adults and constitute 10% of all upper extremity injuries.1,2 An olecranon fracture may be sustained either directly (from blunt trauma or a fall onto the tip of the elbow) or indirectly (as a result of forceful hyperextension of the triceps during a fall onto an outstretched arm). Displaced olecranon fractures with extensor discontinuity require reduction and stabilization. One treatment option is tension band wiring (TBW), which is used to manage noncomminuted fractures.3 TBW, first described by Weber and Vasey4 in 1963, involves transforming the distractive forces of the triceps into dynamic compression forces across the olecranon articular surface using 2 intramedullary Kirschner wires (K-wires) and stainless steel wires looped in figure-of-8 fashion.

Various modifications of the TBW technique of Weber and Vasey4 have been proposed to reduce the frequency of complications. These modifications include substituting screws for K-wires, aiming the angle of the K-wires into the anterior coronoid cortex or loop configuration of the stainless steel wire, using double knots and twisting procedures to finalize fixation, and using alternative materials for the loop construct.5-8 In the literature and in our experience, patients often complain after surgery about prominent K-wires and the twisted knots used to tension the construct.9-12 Surgeons also must address the technical difficulties of positioning the brittle wire without kinking, and avoiding slack while tensioning.

In this article, we report on the clinical outcomes of a series of 7 patients with olecranon fracture treated with a US Food and Drug Administration–approved novel isoelastic ultrahigh-molecular-weight polyethylene (UHMWPE) cerclage cable (Iso-Elastic Cerclage System, Kinamed).

Materials and Methods

Surgical Technique

The patient is arranged in a sloppy lateral position to allow access to the posterior elbow. A nonsterile tourniquet is placed on the upper arm, and the limb is sterilely prepared and draped in standard fashion. A posterolateral incision is made around the olecranon and extended proximally 6 cm and distally 6 cm along the subcutaneous border of the ulna. The fracture is visualized and comminution identified.

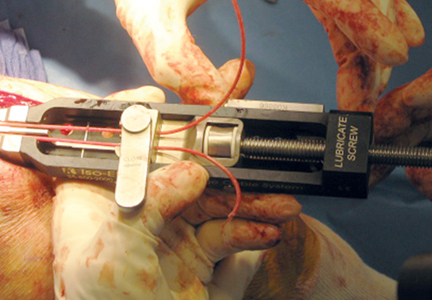

To provide anchorage for a pointed reduction clamp, the surgeon drills a 2.5-mm hole in the subcutaneous border of the ulnar shaft. The fracture is reduced in extension and the clamp affixed. The elbow is then flexed and the reduction confirmed visually and by imaging. After realignment of the articular surfaces, 2 longitudinal, parallel K-wires (diameter, 1.6-2.0 mm) are passed in antegrade direction through the proximal olecranon within the medullary canal of the shaft. The proximal ends must not cross the cortex so they may fully capture the figure-of-8 wire during subsequent, final advancement, and the distal ends must not pierce the anterior cortex. A 2.5-mm transverse hole is created distal to the fracture in the dorsal aspect of the ulnar shaft from medial to lateral at 2 times the distance from the tip of the olecranon to the fracture site. This hole is expanded with a 3.5-mm drill bit, allowing both strands of the cable to be passed simultaneously medial to lateral, making the figure-of-8. The 3.5-mm hole represents about 20% of the overall width of the bone, which we have not found to create a significant stress riser in either laboratory or clinical tests of this construct. Proximally, the cables are placed on the periosteum of the olecranon but deep to the triceps tendon and adjacent to the K-wires. The locking clip is placed on the posterolateral aspect of the elbow joint in a location where it can be covered with local tissue for adequate padding. The cable is then threaded through the clamping bracket and tightened slowly and gradually with a tensioning device to low torque level (Figure 1). At this stage, tension may be released to make any necessary adjustments. Last, the locking clip is deployed, securing the tension band in the clip, and the excess cable is trimmed with a scalpel. Softening and pliability of the cable during its insertion and tensioning should be noted.

The ends of the K-wires are now curved in a hook configuration. The tines of the hooks should be parallel to accommodate the cable, and then the triceps is sharply incised to bone. If the bone is hard, an awl is used to create a pilot hole so the hook may be impaled into bone while capturing the cable. Next, the triceps is closed over the pins, minimizing the potential for pin migration and backout. The 2 K-wires are left in place to keep the fragments in proper anatomical alignment during healing and to prevent displacement with elbow motion. Figure 2 is a schematic of the final construct, and Figure 3 shows the construct in a patient.

Reduction of the olecranon fracture is assessed by imaging in full extension to check for possible implant impingement. Last, we apply the previously harvested fracture callus to the fracture site. Layered closure is performed, and bulky soft dressings are applied. Postoperative immobilization with a splint is used. Gentle range-of-motion exercises begin in about 2 weeks and progress as pain allows.

A case example with preoperative and postoperative images taken at 3-month follow-up is provided in Figure 4. The entire surgical technique can be viewed in the Video.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Clinical Cases

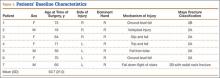

Between July 2007 and February 2011, 7 patients with displaced olecranon fractures underwent osteosynthesis using the isoelastic tension band (Table 1). According to the Mayo classification system, 5 of these patients had type 2A fractures, 1 had a type 2B fracture with an ipsilateral nondisplaced radial neck fracture, and 1 had a type 3B fracture. There were 4 female and 3 male patients. The injury was on the dominant side in 3 patients. All patients gave informed consent to evaluation at subsequent office visits and completed outcomes questionnaires by mail several years after surgery. Mean follow-up at which outcome measures questionnaires were obtained was 3.3 years (range, 2.1-6.8 years). Exclusion criteria were age under 18 years and inability to provide informed consent, fracture patterns with extensive articular comminution, and open fractures. Permission to conduct this research was granted by institutional review board.

At each visit, patients completed the Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand (DASH) functional outcome survey and were evaluated according to Broberg and Morrey’s elbow scoring system.13,14 Chart review consisted of evaluation of medical records, including radiographs and orthopedic physician notes in which preoperative examination was documented, mechanism of injury was noted, radiologic fracture pattern was evaluated, and time to bony union was recorded. Elbow motion was documented. Grip strength was measured with a calibrated Jamar dynamometer (Sammons Preston Rolyan) set at level 2, as delineated in Broberg and Morrey’s functional elbow scoring system.

Results

The 7 patients were assessed at a mean final follow-up of 19 months after surgery and received a mean Broberg and Morrey score of good (92.2/100) (Table 2). Restoration of motion and strength was excellent; compared with contralateral extremity, mean flexion arc was 96%, and mean forearm rotation was 96%. Grip was 99% of the noninjured side, perhaps the result of increased conditioning from physical therapy. Patients completed outcomes questionnaires at a mean of 3.3 years after surgery. Mean (SD) DASH score at this longest follow-up was 12.6 (17.2) (Table 2). Patients were satisfied (mean, 9.8/10; range, 9.5-10) and had little pain (mean, 0.8/10; range, 0-3). All fractures united, and there were no infections. One patient had a satisfactory union with complete restoration of motion and continued to play sports vocationally but developed pain over the locking clip 5 years after the index procedure and decided to have the implant removed. He had no radiographic evidence of K-wire or implant migration. Another patient had a minor degree of implant irritation at longest follow-up but did not request hardware removal.

Discussion

Stainless steel wire is often used in TBW because of its widespread availability, low cost, lack of immunogenicity, and relative strength.7 However, stainless steel wire has several disadvantages. It is susceptible to low-cycle fatigue failure, and fatigue strength may be seriously reduced secondary to incidental trauma to the wire on implantation.15,16 Other complications are kinking, skin irritation, implant prominence, fixation loss caused by wire loosening, and inadequate initial reduction potentially requiring revision.10,12,17-21

Isoelastic cable is a new type of cerclage cable that consists of UHMWPE strands braided over a nylon core. The particular property profile of the isoelastic tension band gives the cable intrinsic elastic and pliable qualities. In addition, unlike stainless steel, the band maintains a uniform, continuous compression force across a fracture site.22 Multifilament braided cables fatigue and fray, but the isoelastic cerclage cable showed no evidence of fraying or breakage after 1 million loading cycles.22,23 Compared with metal wire or braided metal cable, the band also has higher fatigue strength and higher ultimate tensile strength.7 Furthermore, the cable is less abrasive than stainless steel, so theoretically it is less irritating to surrounding subcutaneous tissue. Last, the pliability of the band allows the surgeon to create multiple loops of cable without the wire-failure side effects related to kinking, which is common with the metal construct.

In 2010, Ting and colleagues24 retrospectively studied implant failure complications associated with use of isoelastic cerclage cables in the treatment of periprosthetic fractures in total hip arthroplasty. They reported a breakage rate of 0% and noted that previously published breakage data for metallic cerclage devices ranged from 0% to 44%. They concluded that isoelastic cables were not associated with material failure, and there were no direct complications related to the cables. Similarly, Edwards and colleagues25 evaluated the same type of cable used in revision shoulder arthroplasty and reported excellent success and no failures. Although these data stem from use in the femur and humerus, we think the noted benefits apply to fractures of the elbow as well, as we observed a similar breakage rate (0%).

Various studies have addressed the clinical complaints and reoperation rates associated with retained metal implants after olecranon fixation. Traditional AO (Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Osteosynthesefragen) technique involves subcutaneous placement of stainless steel wires, which often results in tissue irritation. Reoperation rates as high as 80% have been reported, and a proportion of implant removals may in fact be caused by factors related to the subcutaneous placement of the metallic implants rather than K-wire migration alone.5,12,18 A nonmetallic isoelastic tension band can provide a more comfortable and less irritating implant, which could reduce the need for secondary intervention related to painful subcutaneous implant. One of our 7 patients had a symptomatic implant removed 5 years after surgery. This patient complained of pain over the area of the tension band device clip, so after fracture healing the entire fixation device was removed in the operating room. If reoperation is necessary, removal of intramedullary K-wires is relatively simple using a minimal incision; removal of stainless steel TBW may require a larger approach if the twisted knots cannot be easily retrieved.

A study of compression forces created by stainless steel wire demonstrated that a “finely tuned mechanical sense” was needed to produce optimal fixation compression when using stainless steel wire.26 It was observed that a submaximal twist created insufficient compressive force, while an ostensibly minimal increase in twisting force above optimum abruptly caused wire failure through breakage. Cerclage cables using clasping devices, such as the current isoelastic cerclage cable, were superior in ease of application. Furthermore, a clasping device allows for cable tension readjustment that is not possible with stainless steel wire. The clasping mechanism precludes the surgeon from having to bury the stainless steel knot and allows for the objective cable-tensioning not possible with stainless steel wire. Last, the tensioning device is titratable, which allows the surgeon to set the construct at a predetermined quantitative tension, which is of benefit in patients with osteopenia.

One limitation of this study is that it did not resolve the potential for K-wire migration, and we agree with previous recommendations that careful attention to surgical technique may avoid such a complication.10 In addition, the sample was small, and the study lacked a control group; a larger sample and a control group would have boosted study power. Nevertheless, the physical and functional outcomes associated with use of this technique were excellent. These results demonstrate an efficacious attempt to decrease secondary surgery rates and are therefore proof of concept that the isoelastic tension band may be used as an alternative to stainless steel in the TBW of displaced olecranon fractures with minimal or no comminution.

Conclusion

This easily reproducible technique for use of an isoelastic tension band in olecranon fracture fixation was associated with excellent physical and functional outcomes in a series of 7 patients. The rate of secondary intervention was slightly better for these patients than for patients treated with wire tension band fixation. Although more rigorous study of this device is needed, we think it is a promising alternative to wire tension band techniques.

1. Rommens PM, Küchle R, Schneider RU, Reuter M. Olecranon fractures in adults: factors influencing outcome. Injury. 2004;35(11):1149-1157.

2. Veillette CJ, Steinmann SP. Olecranon fractures. Orthop Clin North Am. 2008;39(2):229-236.

3. Newman SD, Mauffrey C, Krikler S. Olecranon fractures. Injury. 2009;40(6):575-581.

4. Weber BG, Vasey H. Osteosynthesis in olecranon fractures [in German]. Z Unfallmed Berufskr. 1963;56:90-96.

5. Netz P, Strömberg L. Non-sliding pins in traction absorbing wiring of fractures: a modified technique. Acta Orthop Scand. 1982;53(3):355-360.

6. Prayson MJ, Williams JL, Marshall MP, Scilaris TA, Lingenfelter EJ. Biomechanical comparison of fixation methods in transverse olecranon fractures: a cadaveric study. J Orthop Trauma. 1997;11(8):565-572.