User login

Annular Erythematous Plaques With Central Hypopigmentation on Sun-Exposed Skin

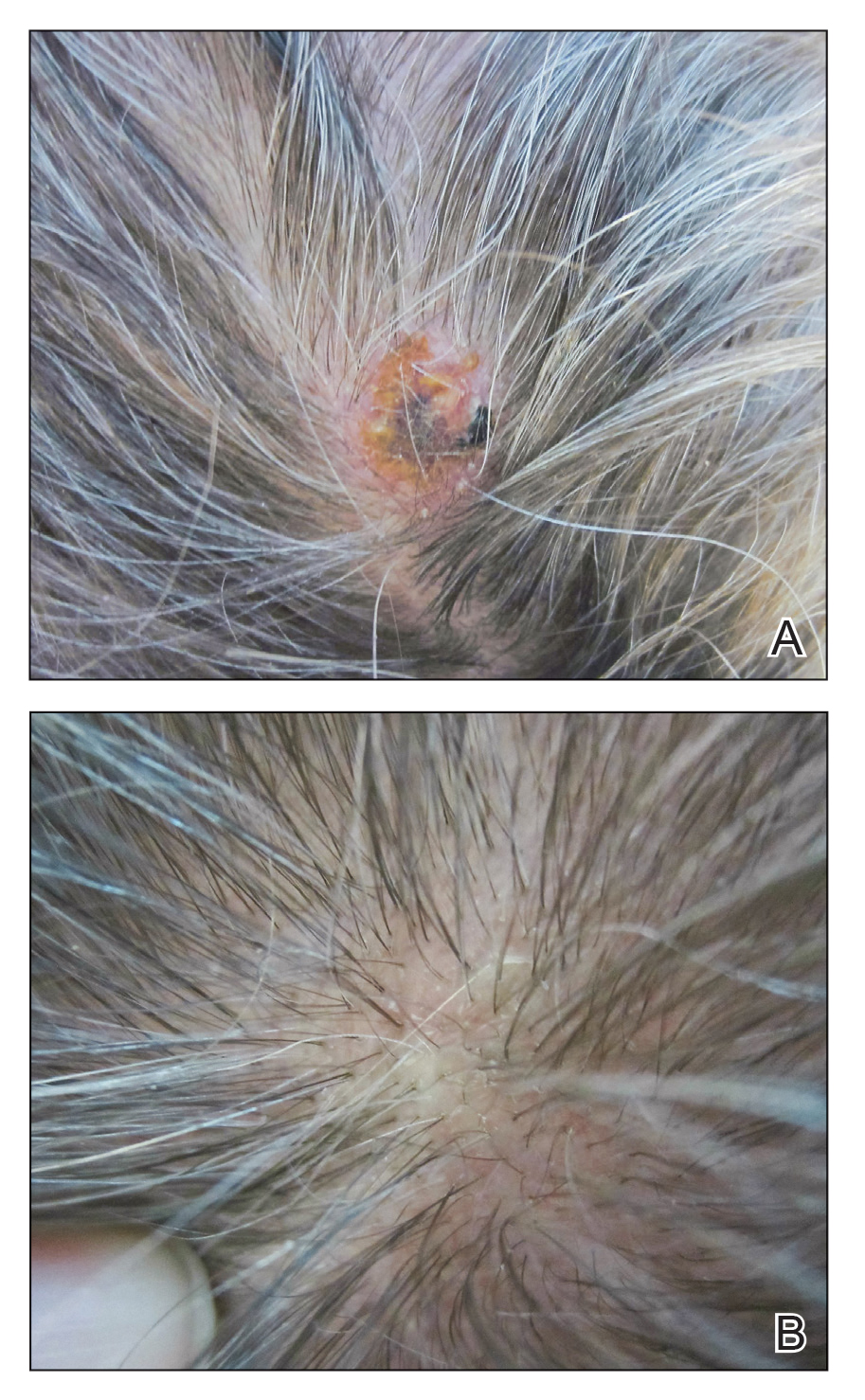

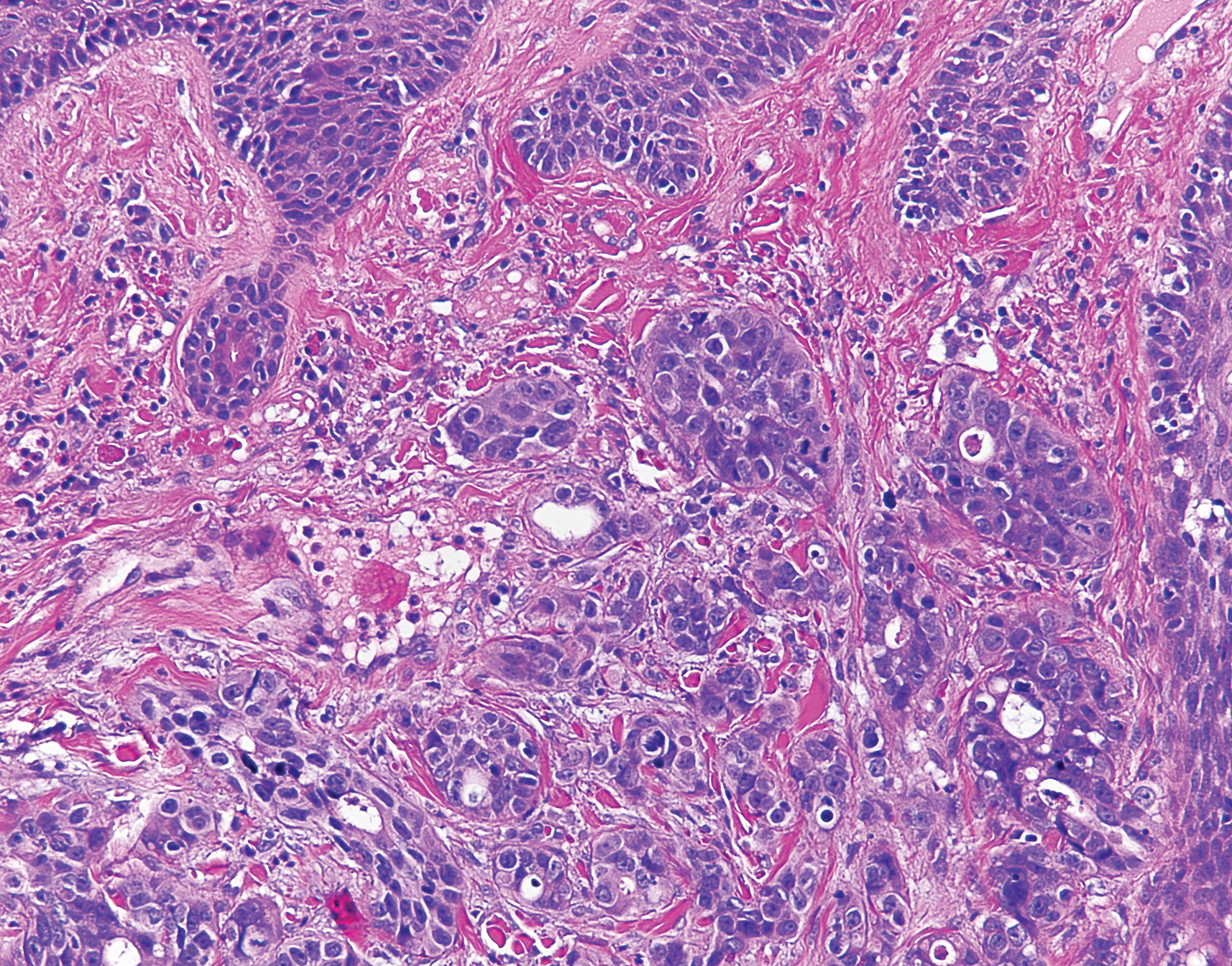

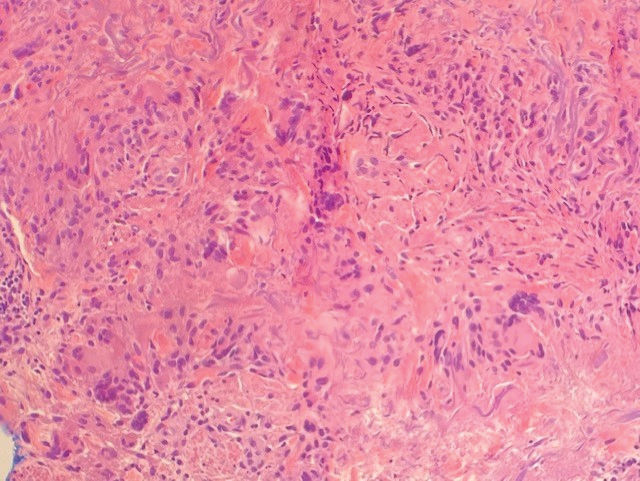

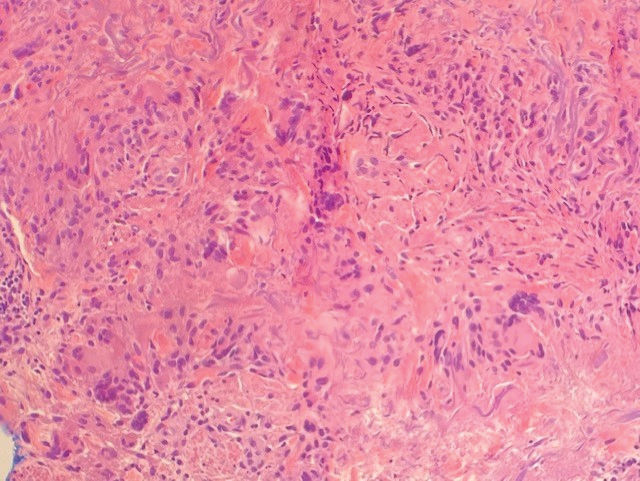

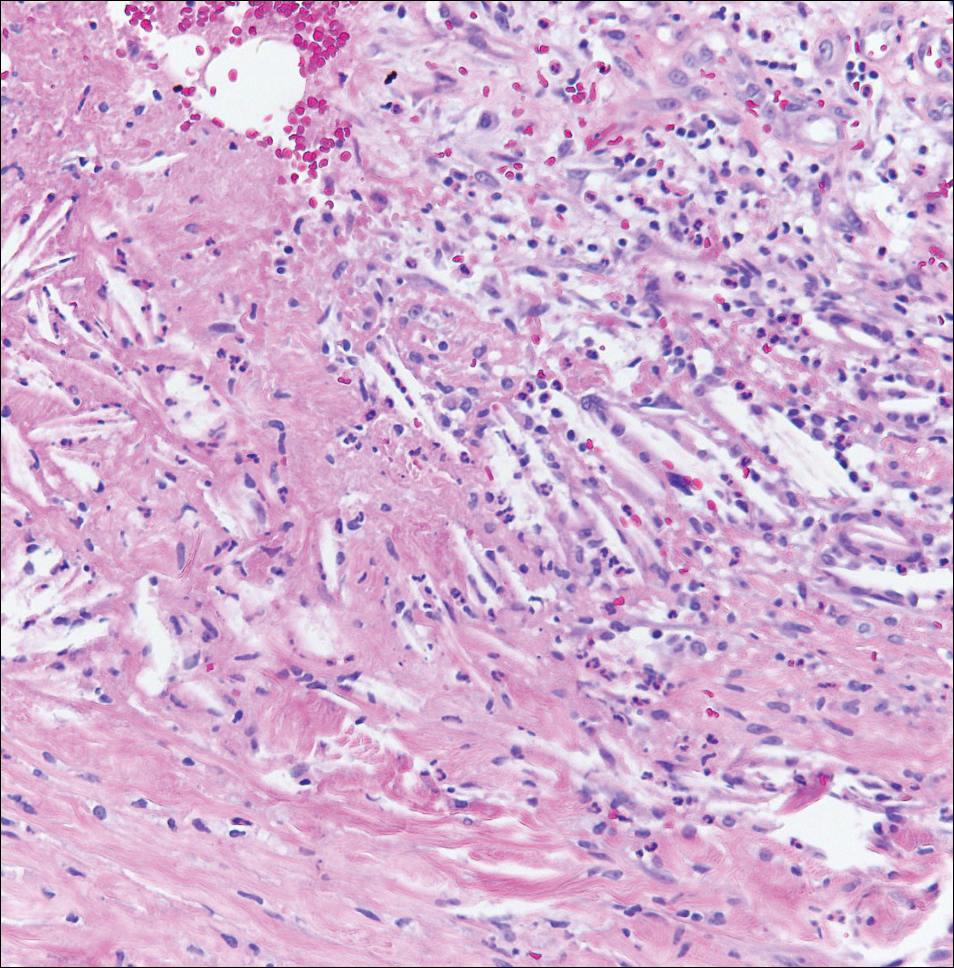

A biopsy showed a markedly elastotic dermis consisting of a palisading granulomatous inflammatory infiltrate and numerous multinucleated histiocytes (Figure). These histopathologic findings along with the clinical presentation confirmed a diagnosis of annular elastolytic granuloma (AEG). Treatment consisting of 3 months of oral minocycline, 2 months of oral doxycycline, and clobetasol ointment all failed. At that point, oral hydroxychloroquine was recommended. Our patient was lost to follow-up by dermatology, then subsequently was placed on hydroxychloroquine by rheumatology to treat both the osteoarthritis and AEG. A follow-up appointment with dermatology was planned for 3 months to monitor hydroxychloroquine treatment and monitor treatment progress; however, she did not follow-up or seek further treatment.

Annular elastolytic granuloma clinically is similar to granuloma annulare (GA), with both presenting as annular plaques surrounded by an elevated border.1 Although AEG clinically is distinct with hypopigmented atrophied plaque centers,2 a biopsy is required to confirm the lack of elastic tissue in zones of atrophy and the presence of multinucleated histiocytes.1,3 Lesions most commonly are seen clinically on sun-exposed areas in middle-aged White women; however, they rarely have been seen on frequently covered skin.4 Our case illustrates the striking photodistribution of AEG, especially on the posterior neck area. The clinical diagnoses of AEG, annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma, and GA in sun-exposed areas are synonymous and can be used interchangeably.5,6

Pathologies considered in the diagnosis of AEG include but are not limited to tinea corporis, annular lichen planus, erythema annulare centrifugum, and necrobiosis lipoidica. Scaling typically is absent in AEG, while tinea corporis presents with hyphae within the stratum corneum of the plaques.7 Papules along the periphery of annular lesions are more typical of annular lichen planus than AEG, and they tend to have a more purple hue.8 Erythema annulare centrifugum has annular erythematous plaques similar to those found in AEG but differs with scaling on the inner margins of these plaques. Histopathology presenting with a lymphocytic infiltrate surrounding vasculature and no indication of elastolytic degradation would further indicate a diagnosis of erythema annulare centrifugum.9 Histopathology showing necrobiosis, lipid depositions, and vascular wall thickenings is indicative of necrobiosis lipoidica.10

Similar to GA,11 the cause of AEG is idiopathic.2 Annular elastolytic granuloma and GA differ in the fact that elastin degradation is characteristic of AEG compared to collagen degradation in GA. It is suspected that elastin degradation in AEG patients is caused by an immune response triggering phagocytosis of elastin by multinucleated histiocytes.2 Actinic damage also is considered a possible cause of elastin fiber degradation in AEG.12 Granuloma annulare can be ruled out and the diagnosis of AEG confirmed with the absence of elastin fibers and mucin on pathology.13

Although there is no established first-line treatment of AEG, successful treatment has been achieved with antimalarial drugs paired with topical steroids.14 Treatment recommendations for AEG include minocycline, chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine, tranilast, and oral retinoids, as well as oral and topical steroids. In clinical cases where AEG occurs in the setting of a chronic disease such as diabetes mellitus, vascular occlusion, arthritis, or hypertension, treatment of underlying disease has been shown to resolve AEG symptoms.14

Although light therapy is not common for AEG, UV light radiation has demonstrated success in treating AEG.15,16 One study showed complete clearance of granulomatous papules after narrowband UVB treatment.15 Another study showed that 2 patients treated with psoralen plus UVA therapy reached complete clearance of AEG lasting at least 3 months after treatment.16

1. Lai JH, Murray SJ, Walsh NM. Evolution of granuloma annulare to mid-dermal elastolysis: report of a case and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2014;41:462-468. doi:10.1111/cup.12292 2. Klemke CD, Siebold D, Dippel E, et al. Generalised annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma. Dermatology. 2003;207:420-422. doi:10.1159/000074132 3. Limas C. The spectrum of primary cutaneous elastolytic granulomas and their distinction from granuloma annulare: a clinicopathological analysis. Histopathology. 2004;44:277-282. doi:10.1111/j.0309-0167.2004.01755.x 4. Revenga F, Rovira I, Pimentel J, et al. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma—actinic granuloma? Clin Exp Dermatol. 1996;21:51-53. 5. Hawryluk EB, Izikson L, English JC 3rd. Non-infectious granulomatous diseases of the skin and their associated systemic diseases: an evidence-based update to important clinical questions. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2010;11:171-181. doi:10.2165/11530080-000000000-00000 6. Berliner JG, Haemel A, LeBoit PE, et al. The sarcoidal variant of annular elastolytic granuloma. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:918-920. doi:10.1111/cup.12237 7. Pflederer RT, Ahmed S, Tonkovic-Capin V, et al. Annular polycyclic plaques on the chest and upper back [published online April 24, 2018]. JAAD Case Rep. 2018;4:405-407. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2017.07.022 8. Trayes KP, Savage K, Studdiford JS. Annular lesions: diagnosis and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2018;98:283-291. 9. Weyers W, Diaz-Cascajo C, Weyers I. Erythema annulare centrifugum: results of a clinicopathologic study of 73 patients. Am J Dermatopathol. 2003;25:451-462. doi:10.1097/00000372-200312000-00001 10. Dowling GB, Jones EW. Atypical (annular) necrobiosis lipoidica of the face and scalp. a report of the clinical and histological features of 7 cases. Dermatologica. 1967;135:11-26. doi:10.1159/000254156 11. Piette EW, Rosenbach M. Granuloma annulare: pathogenesis, disease associations and triggers, and therapeutic options. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:467-479. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015 .03.055 12. O’Brien JP, Regan W. Actinically degenerate elastic tissue is the likely antigenic basis of actinic granuloma of the skin and of temporal arteritis [published correction appears in J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000; 42(1 pt 1):148]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40(2 pt 1):214-222. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(99)70191-x 13. Rencic A, Nousari CH. Other rheumatologic diseases. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, et al, eds. Dermatology. 2nd ed. Elsevier Limited; 2008:600-601. 14. Burlando M, Herzum A, Cozzani E, et al. Can methotrexate be a successful treatment for unresponsive generalized annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma? case report and review of the literature. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34:E14705. doi:10.1111/dth.14705 15. Takata T, Ikeda M, Kodama H, et al. Regression of papular elastolytic giant cell granuloma using narrow-band UVB irradiation. Dermatology. 2006;212:77-79. doi:10.1159/000089028 16. Pérez-Pérez L, García-Gavín J, Allegue F, et al. Successful treatment of generalized elastolytic giant cell granuloma with psoralenultraviolet A. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2012;28:264-266. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0781.2012.00680.x

A biopsy showed a markedly elastotic dermis consisting of a palisading granulomatous inflammatory infiltrate and numerous multinucleated histiocytes (Figure). These histopathologic findings along with the clinical presentation confirmed a diagnosis of annular elastolytic granuloma (AEG). Treatment consisting of 3 months of oral minocycline, 2 months of oral doxycycline, and clobetasol ointment all failed. At that point, oral hydroxychloroquine was recommended. Our patient was lost to follow-up by dermatology, then subsequently was placed on hydroxychloroquine by rheumatology to treat both the osteoarthritis and AEG. A follow-up appointment with dermatology was planned for 3 months to monitor hydroxychloroquine treatment and monitor treatment progress; however, she did not follow-up or seek further treatment.

Annular elastolytic granuloma clinically is similar to granuloma annulare (GA), with both presenting as annular plaques surrounded by an elevated border.1 Although AEG clinically is distinct with hypopigmented atrophied plaque centers,2 a biopsy is required to confirm the lack of elastic tissue in zones of atrophy and the presence of multinucleated histiocytes.1,3 Lesions most commonly are seen clinically on sun-exposed areas in middle-aged White women; however, they rarely have been seen on frequently covered skin.4 Our case illustrates the striking photodistribution of AEG, especially on the posterior neck area. The clinical diagnoses of AEG, annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma, and GA in sun-exposed areas are synonymous and can be used interchangeably.5,6

Pathologies considered in the diagnosis of AEG include but are not limited to tinea corporis, annular lichen planus, erythema annulare centrifugum, and necrobiosis lipoidica. Scaling typically is absent in AEG, while tinea corporis presents with hyphae within the stratum corneum of the plaques.7 Papules along the periphery of annular lesions are more typical of annular lichen planus than AEG, and they tend to have a more purple hue.8 Erythema annulare centrifugum has annular erythematous plaques similar to those found in AEG but differs with scaling on the inner margins of these plaques. Histopathology presenting with a lymphocytic infiltrate surrounding vasculature and no indication of elastolytic degradation would further indicate a diagnosis of erythema annulare centrifugum.9 Histopathology showing necrobiosis, lipid depositions, and vascular wall thickenings is indicative of necrobiosis lipoidica.10

Similar to GA,11 the cause of AEG is idiopathic.2 Annular elastolytic granuloma and GA differ in the fact that elastin degradation is characteristic of AEG compared to collagen degradation in GA. It is suspected that elastin degradation in AEG patients is caused by an immune response triggering phagocytosis of elastin by multinucleated histiocytes.2 Actinic damage also is considered a possible cause of elastin fiber degradation in AEG.12 Granuloma annulare can be ruled out and the diagnosis of AEG confirmed with the absence of elastin fibers and mucin on pathology.13

Although there is no established first-line treatment of AEG, successful treatment has been achieved with antimalarial drugs paired with topical steroids.14 Treatment recommendations for AEG include minocycline, chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine, tranilast, and oral retinoids, as well as oral and topical steroids. In clinical cases where AEG occurs in the setting of a chronic disease such as diabetes mellitus, vascular occlusion, arthritis, or hypertension, treatment of underlying disease has been shown to resolve AEG symptoms.14

Although light therapy is not common for AEG, UV light radiation has demonstrated success in treating AEG.15,16 One study showed complete clearance of granulomatous papules after narrowband UVB treatment.15 Another study showed that 2 patients treated with psoralen plus UVA therapy reached complete clearance of AEG lasting at least 3 months after treatment.16

A biopsy showed a markedly elastotic dermis consisting of a palisading granulomatous inflammatory infiltrate and numerous multinucleated histiocytes (Figure). These histopathologic findings along with the clinical presentation confirmed a diagnosis of annular elastolytic granuloma (AEG). Treatment consisting of 3 months of oral minocycline, 2 months of oral doxycycline, and clobetasol ointment all failed. At that point, oral hydroxychloroquine was recommended. Our patient was lost to follow-up by dermatology, then subsequently was placed on hydroxychloroquine by rheumatology to treat both the osteoarthritis and AEG. A follow-up appointment with dermatology was planned for 3 months to monitor hydroxychloroquine treatment and monitor treatment progress; however, she did not follow-up or seek further treatment.

Annular elastolytic granuloma clinically is similar to granuloma annulare (GA), with both presenting as annular plaques surrounded by an elevated border.1 Although AEG clinically is distinct with hypopigmented atrophied plaque centers,2 a biopsy is required to confirm the lack of elastic tissue in zones of atrophy and the presence of multinucleated histiocytes.1,3 Lesions most commonly are seen clinically on sun-exposed areas in middle-aged White women; however, they rarely have been seen on frequently covered skin.4 Our case illustrates the striking photodistribution of AEG, especially on the posterior neck area. The clinical diagnoses of AEG, annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma, and GA in sun-exposed areas are synonymous and can be used interchangeably.5,6

Pathologies considered in the diagnosis of AEG include but are not limited to tinea corporis, annular lichen planus, erythema annulare centrifugum, and necrobiosis lipoidica. Scaling typically is absent in AEG, while tinea corporis presents with hyphae within the stratum corneum of the plaques.7 Papules along the periphery of annular lesions are more typical of annular lichen planus than AEG, and they tend to have a more purple hue.8 Erythema annulare centrifugum has annular erythematous plaques similar to those found in AEG but differs with scaling on the inner margins of these plaques. Histopathology presenting with a lymphocytic infiltrate surrounding vasculature and no indication of elastolytic degradation would further indicate a diagnosis of erythema annulare centrifugum.9 Histopathology showing necrobiosis, lipid depositions, and vascular wall thickenings is indicative of necrobiosis lipoidica.10

Similar to GA,11 the cause of AEG is idiopathic.2 Annular elastolytic granuloma and GA differ in the fact that elastin degradation is characteristic of AEG compared to collagen degradation in GA. It is suspected that elastin degradation in AEG patients is caused by an immune response triggering phagocytosis of elastin by multinucleated histiocytes.2 Actinic damage also is considered a possible cause of elastin fiber degradation in AEG.12 Granuloma annulare can be ruled out and the diagnosis of AEG confirmed with the absence of elastin fibers and mucin on pathology.13

Although there is no established first-line treatment of AEG, successful treatment has been achieved with antimalarial drugs paired with topical steroids.14 Treatment recommendations for AEG include minocycline, chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine, tranilast, and oral retinoids, as well as oral and topical steroids. In clinical cases where AEG occurs in the setting of a chronic disease such as diabetes mellitus, vascular occlusion, arthritis, or hypertension, treatment of underlying disease has been shown to resolve AEG symptoms.14

Although light therapy is not common for AEG, UV light radiation has demonstrated success in treating AEG.15,16 One study showed complete clearance of granulomatous papules after narrowband UVB treatment.15 Another study showed that 2 patients treated with psoralen plus UVA therapy reached complete clearance of AEG lasting at least 3 months after treatment.16

1. Lai JH, Murray SJ, Walsh NM. Evolution of granuloma annulare to mid-dermal elastolysis: report of a case and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2014;41:462-468. doi:10.1111/cup.12292 2. Klemke CD, Siebold D, Dippel E, et al. Generalised annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma. Dermatology. 2003;207:420-422. doi:10.1159/000074132 3. Limas C. The spectrum of primary cutaneous elastolytic granulomas and their distinction from granuloma annulare: a clinicopathological analysis. Histopathology. 2004;44:277-282. doi:10.1111/j.0309-0167.2004.01755.x 4. Revenga F, Rovira I, Pimentel J, et al. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma—actinic granuloma? Clin Exp Dermatol. 1996;21:51-53. 5. Hawryluk EB, Izikson L, English JC 3rd. Non-infectious granulomatous diseases of the skin and their associated systemic diseases: an evidence-based update to important clinical questions. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2010;11:171-181. doi:10.2165/11530080-000000000-00000 6. Berliner JG, Haemel A, LeBoit PE, et al. The sarcoidal variant of annular elastolytic granuloma. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:918-920. doi:10.1111/cup.12237 7. Pflederer RT, Ahmed S, Tonkovic-Capin V, et al. Annular polycyclic plaques on the chest and upper back [published online April 24, 2018]. JAAD Case Rep. 2018;4:405-407. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2017.07.022 8. Trayes KP, Savage K, Studdiford JS. Annular lesions: diagnosis and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2018;98:283-291. 9. Weyers W, Diaz-Cascajo C, Weyers I. Erythema annulare centrifugum: results of a clinicopathologic study of 73 patients. Am J Dermatopathol. 2003;25:451-462. doi:10.1097/00000372-200312000-00001 10. Dowling GB, Jones EW. Atypical (annular) necrobiosis lipoidica of the face and scalp. a report of the clinical and histological features of 7 cases. Dermatologica. 1967;135:11-26. doi:10.1159/000254156 11. Piette EW, Rosenbach M. Granuloma annulare: pathogenesis, disease associations and triggers, and therapeutic options. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:467-479. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015 .03.055 12. O’Brien JP, Regan W. Actinically degenerate elastic tissue is the likely antigenic basis of actinic granuloma of the skin and of temporal arteritis [published correction appears in J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000; 42(1 pt 1):148]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40(2 pt 1):214-222. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(99)70191-x 13. Rencic A, Nousari CH. Other rheumatologic diseases. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, et al, eds. Dermatology. 2nd ed. Elsevier Limited; 2008:600-601. 14. Burlando M, Herzum A, Cozzani E, et al. Can methotrexate be a successful treatment for unresponsive generalized annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma? case report and review of the literature. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34:E14705. doi:10.1111/dth.14705 15. Takata T, Ikeda M, Kodama H, et al. Regression of papular elastolytic giant cell granuloma using narrow-band UVB irradiation. Dermatology. 2006;212:77-79. doi:10.1159/000089028 16. Pérez-Pérez L, García-Gavín J, Allegue F, et al. Successful treatment of generalized elastolytic giant cell granuloma with psoralenultraviolet A. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2012;28:264-266. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0781.2012.00680.x

1. Lai JH, Murray SJ, Walsh NM. Evolution of granuloma annulare to mid-dermal elastolysis: report of a case and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2014;41:462-468. doi:10.1111/cup.12292 2. Klemke CD, Siebold D, Dippel E, et al. Generalised annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma. Dermatology. 2003;207:420-422. doi:10.1159/000074132 3. Limas C. The spectrum of primary cutaneous elastolytic granulomas and their distinction from granuloma annulare: a clinicopathological analysis. Histopathology. 2004;44:277-282. doi:10.1111/j.0309-0167.2004.01755.x 4. Revenga F, Rovira I, Pimentel J, et al. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma—actinic granuloma? Clin Exp Dermatol. 1996;21:51-53. 5. Hawryluk EB, Izikson L, English JC 3rd. Non-infectious granulomatous diseases of the skin and their associated systemic diseases: an evidence-based update to important clinical questions. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2010;11:171-181. doi:10.2165/11530080-000000000-00000 6. Berliner JG, Haemel A, LeBoit PE, et al. The sarcoidal variant of annular elastolytic granuloma. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:918-920. doi:10.1111/cup.12237 7. Pflederer RT, Ahmed S, Tonkovic-Capin V, et al. Annular polycyclic plaques on the chest and upper back [published online April 24, 2018]. JAAD Case Rep. 2018;4:405-407. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2017.07.022 8. Trayes KP, Savage K, Studdiford JS. Annular lesions: diagnosis and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2018;98:283-291. 9. Weyers W, Diaz-Cascajo C, Weyers I. Erythema annulare centrifugum: results of a clinicopathologic study of 73 patients. Am J Dermatopathol. 2003;25:451-462. doi:10.1097/00000372-200312000-00001 10. Dowling GB, Jones EW. Atypical (annular) necrobiosis lipoidica of the face and scalp. a report of the clinical and histological features of 7 cases. Dermatologica. 1967;135:11-26. doi:10.1159/000254156 11. Piette EW, Rosenbach M. Granuloma annulare: pathogenesis, disease associations and triggers, and therapeutic options. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:467-479. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015 .03.055 12. O’Brien JP, Regan W. Actinically degenerate elastic tissue is the likely antigenic basis of actinic granuloma of the skin and of temporal arteritis [published correction appears in J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000; 42(1 pt 1):148]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40(2 pt 1):214-222. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(99)70191-x 13. Rencic A, Nousari CH. Other rheumatologic diseases. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, et al, eds. Dermatology. 2nd ed. Elsevier Limited; 2008:600-601. 14. Burlando M, Herzum A, Cozzani E, et al. Can methotrexate be a successful treatment for unresponsive generalized annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma? case report and review of the literature. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34:E14705. doi:10.1111/dth.14705 15. Takata T, Ikeda M, Kodama H, et al. Regression of papular elastolytic giant cell granuloma using narrow-band UVB irradiation. Dermatology. 2006;212:77-79. doi:10.1159/000089028 16. Pérez-Pérez L, García-Gavín J, Allegue F, et al. Successful treatment of generalized elastolytic giant cell granuloma with psoralenultraviolet A. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2012;28:264-266. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0781.2012.00680.x

A 67-year-old White woman presented to our dermatology clinic with pruritic annular erythematous plaques with central hypopigmentation on the forearms, dorsal aspect of the hands, neck, and fingers of 3 to 4 months’ duration. The patient rated the severity of pruritus an 8 on a 10-point scale. A review of symptoms was positive for fatigue, joint pain, and headache. The patient had a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus, osteoarthritis, thyroid disease, and stage 3 renal failure. A punch biopsy from the left forearm was performed.

Eczema Herpeticum in a Patient With Hailey-Hailey Disease Confounded by Coexistent Psoriasis

To the Editor:

Hailey-Hailey disease (HHD), also known as benign familial pemphigus, is an uncommon autosomal-dominant skin disease.1 Defects in the ATPase type 2C member 1 gene, ATP2C1, result in abnormal intracellular epidermal adherence, and patients experience recurring blisters in skin folds. Longitudinal white streaks of the fingernails also may be present.1 The illness does not appear until puberty and is heightened by the second or third decade of life. Family history often suggests the presence of disease.2 Misdiagnosis of HHD occurs because of a wide spectrum of presentations. The presence of superimposed infections and carcinomas may both obscure and exacerbate this disease.2

Herpes simplex viruse types 1 and 2 (HSV-1 and HSV-2) are DNA viruses that cause common recurrent diseases. Usually, HSV-1 is associated with infection of the mouth and HSV-2 is associated with infection of the genitalia.3 Longitudinal cutaneous lesions manifest as grouped vesicles on an erythematous base. Tzanck smear of herpetic vesicles will reveal the presence of multinucleated giant cells. A direct fluorescent antibody technique also may be used to confirm the diagnosis.3

Erythrodermic HHD disease is a rare condition; moreover, there are only a few reported cases with coexistence of HHD and HSV in the literature.3-6 We report a rare presentation of erythrodermic HHD and coexistent psoriasis with HSV superinfection.

A 69-year-old man presented to an outpatient dermatology clinic for evaluation and treatment of a rash on the scalp, face, back, and lower legs. The patient confirmed a dandruff diagnosis on the scalp and face as well as psoriasis on the trunk and extremities for the last 45 years. He described a history of successful treatment with topical agents and UV light therapy. A family history revealed that the patient’s father and 1 of 2 siblings had a similar rash and “skin problems.” The patient had a medical history of thyroid cancer treated with radiation treatment and a partial thyroidectomy 35 years prior to the current presentation as well as incompletely treated chronic hepatitis C.

A search of medical records revealed a punch biopsy from the posterior neck that demonstrated an acantholytic dyskeratosis with suprabasal acantholysis. Clinicians were unable to differentiate if it was Darier disease (DAR) or HHD. Treatment of the patient’s seborrheic dermatitis and acantholytic disorder was successful at that time with ketoconazole shampoo, ketoconazole cream, desonide cream, and triamcinolone cream. The patient remained stable for 5 years before presenting again to the dermatology clinic for worsening rash despite topical therapies.

At the current presentation, physical examination at the outpatient dermatology clinic revealed few scaly, erythematous, eroded papules distributed on the mid-back; erythematous greasy scaling on the scalp, face, and chest; and pink scaly plaques with white-silvery scale on the anterior lower legs. Histopathology of a specimen from the right mid-back demonstrated acantholysis with suprabasal clefting, hyperkeratosis, and parakeratosis with no dyskeratotic cells identified. The pathologic differential diagnosis included primary acantholytic processes including Grover disease, DAR, HHD, and pemphigus. Pathology from the right shin demonstrated acanthosis, confluent parakeratosis with associated decreased granular cell layer and collections of neutrophils within the stratum corneum, spongiosis, and superficial dermal perivascular chronic inflammation with focal exocytosis and dilated blood vessels in the papillary dermis. The clinical and pathological diagnosis on the lower legs was consistent with psoriasis. Diagnoses of seborrheic dermatitis, psoriasis on the lower legs, and HHD vs DAR on the back and chest were made. The patient was instructed to continue ketoconazole shampoo, ketoconazole cream, and desonide for seborrheic dermatitis; fluocinonide ointment 0.05% to the lower legs for psoriasis; and triamcinolone cream and a bland moisturizer to the back and chest for HHD.

Over the ensuing months, the rash worsened with erythema and scaling affecting more than half of the body surface area. Topical corticosteroids and bland emollients resulted in minimal success. Biologics and acitretin were considered for the psoriasiform dermatitis but avoided due to the patient’s medical history of thyroid cancer and chronic hepatitis C infection. Because the patient described prior success with UV light therapy for psoriasis, he requested light therapy. A subsequent trial of narrowband UVB light therapy initially improved some of the psoriasiform dermatitis on the trunk and extremities; however, after 4 weeks of treatment, the patient described pain in some of the skin and felt he was burned by minimal exposure to light therapy on one particular visit, which caused him to stop light therapy.

Approximately 2 weeks later, the patient presented to the emergency department stating his psoriasis was infected; he was diagnosed with psoriasis with secondary cellulitis and received intravenous vancomycin and piperacillin-tazobactam, with bacterial cultures demonstrating Corynebacterium and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Some improvement was noted in the patient’s skin after antibiotics were initiated, but he continued to describe worsening “burning and pain” throughout the psoriasis lesions. The patient’s care was transferred to the Veterans Affairs hospital where a dermatology inpatient consultation was placed.

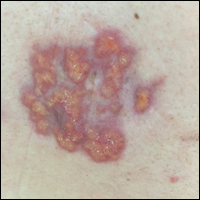

Our initial dermatologic examination revealed generalized scaly erythroderma on the neck, trunk, and extremities, sparing the face, palms, and soles (Figure 1). Multiple crusted and intact vesicles also were present overlying the erythematous plaques on the chest, back, and proximal extremities, most grouped in clusters. The patient endorsed new symptoms of pain and burning. Tzanck smear from the abdomen along with shave biopsies from the left flank and right abdomen were performed, and intravenous acyclovir was initiated immediately after these procedures.

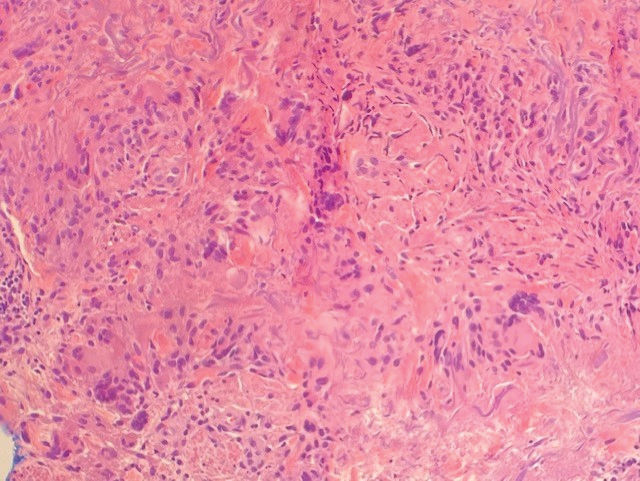

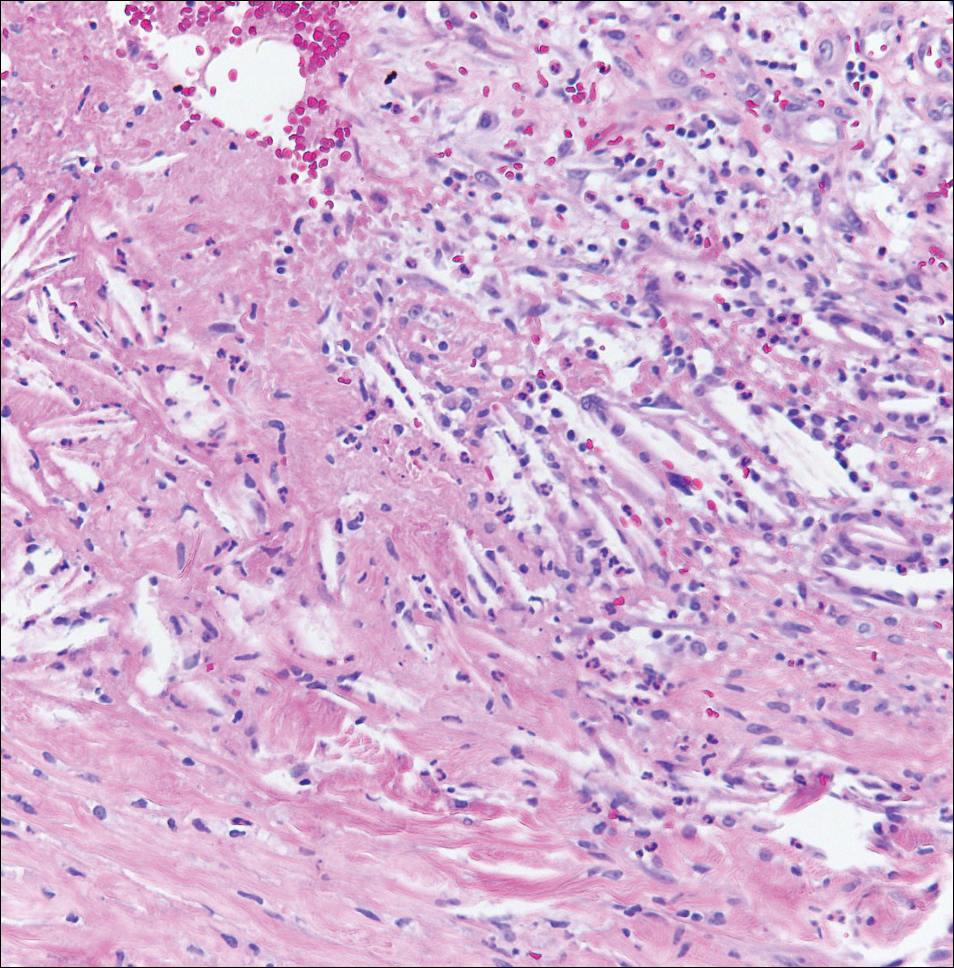

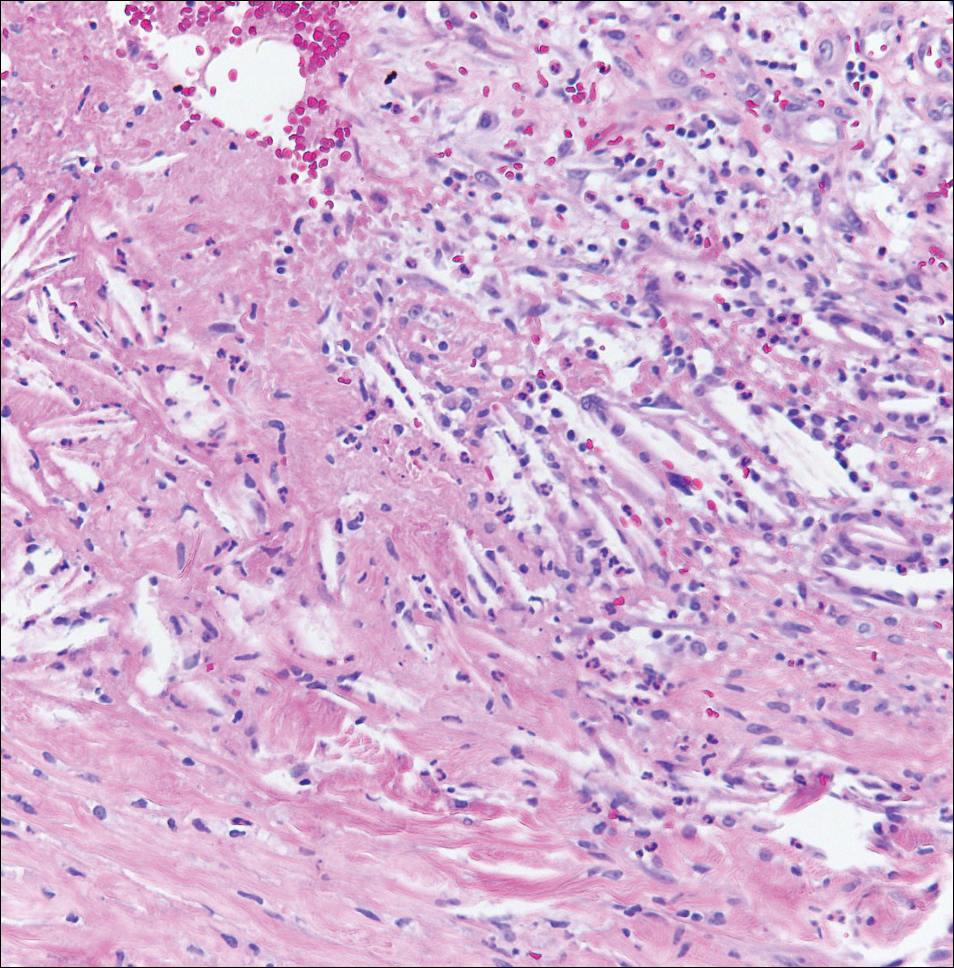

Viral cultures were taken but were incorrectly processed by the laboratory. Tzanck smear showed severe acute inflammation with numerous neutrophils, multinucleated giant cells with viral nuclear changes, and positive immunostaining for HSV and negative immunostaining for herpes zoster. Both pathology specimens revealed an intense acute mixed, mainly neutrophilic, inflammatory infiltrate extending into the deeper dermis as well as distorted and necrotic hair follicles, some of which displayed multinucleated epithelial cells with margination of chromatin that were positive for both HSV-1 and HSV-2 and negative for herpes zoster (Figure 2). The positivity of both HSV strains might represent co-infection or could be a cross-reaction of antibodies used in immunohistochemistry to the HSV antigens. There was acantholysis surrounding the ulceration and extending through the full thickness of the epidermis with a dilapidated brick wall pattern (Figure 3) as well as negative immunohistochemical staining for HSV-1 and HSV-2 antigens. The clinical and histological picture together, along with prior clinical and pathological reports, confirmed the diagnoses of acute erythrodermic HHD with HSV superinfection.

The patient’s condition and pain improved within 24 hours on intravenous acyclovir. On the third day, his lesions were resolving and symptoms improved, so he was transitioned to oral acyclovir and discharged from the hospital. Follow-up in the dermatology outpatient clinic 1 week later revealed that all vesicles and papules had cleared, but the patient was still erythrodermic. Because HHD cannot always be distinguished histologically from other forms of pemphigus but yields a negative immunofluorescence, direct immunofluorescence and indirect immunofluorescence were obtained upon patient follow-up in the clinic and were both negative. Hepatitis C viral loads were undetectable. Consultations to gastroenterology and oncology teams were placed for consideration of systemic agents, and the patient was initiated on oral acitretin 25 mg daily, along with clobetasol as adjuvant therapy for any residual skin plaques. The laboratory results were closely monitored. Within 4 weeks after starting acitretin, the patient’s erythroderma had completely resolved. The patient has remained stable since then, except for one episode of secondary Staphylococcus infection that cleared on oral antibiotics. The patient remains stable and clear on oral acitretin 25 mg daily, with concomitant desonide cream and fluocinonide ointment as needed.

Hailey-Hailey disease is characterized by recurrent episodes of erythema, blisters, and plaques localized to intertriginous and perianal areas.1,2 Patients display a spectrum of lesions that vary in severity.8 Typical histologic examination reveals a dilapidated brick wall appearance. Pathology of well-developed lesions will show suprabasal acantholysis with minimal dyskeratosis.2

The generalized form of HHD is an extremely rare variant of the disease.10 Generalized HHD may resemble acute hypersensitivity reaction, erythema multiforme, and toxic epidermal necrolysis.1 Chronic diseases, such as psoriasis (as in this patient), also may contribute to a clinically confusing picture.8 Hailey-Hailey disease and psoriasis are thought to occasionally koebnerize (isomorphic response) to areas of trauma.16 Our patient experienced widespread erythematous papules and plaques not restricted to skin folds. His skin lesions continued to worsen over several months progressing to erythroderma. The presence of suprabasal acantholysis in a dilapidated brick wall pattern, along with the patient’s history, prior pathology reports, clinical picture, and negative direct immunofluorescence and indirect immunofluorescence studies helped to confirm the diagnosis of erythrodermic HHD.

Hailey-Hailey disease is caused by heterozygous mutations in the ATP2C1 gene on chromosome 3q21-24 coding for a Golgi ATPase called SPCA1 (secretory pathway calcium/manganese-ATPase).9 Subsequent disturbances in cytosolic-Golgi calcium concentrations interfere with epidermal keratinocyte adherence resulting in acantholytic disease. Studies of interfamilial and intrafamilial mutations fail to pinpoint a common mutation pattern among patients with generalized phenotypes,9 which further supports theories that intrinsic or extrinsic factors such as friction, heat, radiation, contact allergens, and infection affect the severity of HHD disease and not the type of mutation.3,9

Generalization of HHD is likely caused by nonspecific triggers in an already genetically disturbed epidermis.10 Interrupted epithelial function exposes skin to infections that exacerbate the underlying disease. Superimposing bacterial infections are commonly reported in HHD. Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, and Candida species colonize the skin and aggravate the disease.11 Much less commonly, HSV superinfection can complicate HHD.3-7 No data are currently available about the frequency or incidence of Herpesviridae in HHD.7 Some studies suggest that UVB light therapy can be an exacerbating factor in DAR and some but not all HHD patients,12,13 while other case reports14,15 document clinically improved responses using phototherapy for patients with HHD. Clinicians should remain suspicious and evaluate for HSV infection in refractory or sudden exacerbation of HHD.7 Furthermore, coexistent psoriasis and HHD also is a rare entity but has been described,8 which illustrates the importance of not attributing all skin manifestations to a previously diagnosed disorder but instead keeping an open mind in case new dermatologic conditions present themselves at a later time.

We present a rare case of erythrodermic HHD and coexistent psoriasis with HSV superinfection. We hope to draw awareness to this association of generalized HHD with both HSV and psoriasis to help clinicians make the correct diagnosis promptly in similar cases in the future.

- Chave TA, Milligan A. Acute generalized Hailey-Hailey disease. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2002;27:290-292.

- Mohr MR, Erdag G, Shada Al, et al. Two patients with Hailey-Hailey disease, multiple primary melanomas, and other cancers. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:211-215.

- Lee GM, Kim YM, Lee SY, et al. A case of eczema herpeticum with Hailey-Hailey Disease. Ann Dermatol. 2009;21:311-314.

- Zaim MT, Bickers DR. Herpes simplex associated with Hailey-Hailey disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:701-702.

- Peppiatt T, Keefe M, White JE. Hailey-Hailey disease-exacerbation by herpes simplex virus and patch tests. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2006;17:201-202.

- Almeida L, Grossman ME. Benign familial pemphigus complicated by herpes simplex virus. Cutis. 1989;44:261-262.

- Nikkels AF, Delvenne P, Herfs M, et al. Occult herpes simplex virus colonization of bullous dermatitides. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2008;9:163-168.

- Chao SC, Lee JY, Wu MC, et al. A novel splice mutation in the ATP2C1 gene in a woman with concomitant psoriasis vulgaris and disseminated Hailey-Hailey disease. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:947-951.

- Ikeda S, Shigihara T, Mayuzumi N, et al. Mutations of ATP2C1 in Japanese patients with Hailey-Hailey disease: intrafamilial and interfamilial phenotype variations and lack of correlation with mutation patterns. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;117:1654-1656.

- Marsch W, Stuttgen G. Generalized Hailey-Hailey disease. Br J Dermatol. 1978;99:553-559.

- Friedman-Birnbaum R, Haim S, Marcus S. Generalized familial benign chronic pemphigus. Dermatologica. 1980;161:112-115.

- Richard G, Linse R, Harth W. Hailey-Hailey disease. early detection of heterozygotes by an ultraviolet provocation tests—clinical relevance of the method. Hautarzt. 1993;44:376-379.

- Mayuzumi N, Ikeda S, Kawada H, et al. Effects of ultraviolet B irradiation, proinflammatory cytokines and raised extracellular calcium concentration on the expression of ATP2A2 and ATP2C1. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:697-701.

- Vanderbeck KA, Giroux L, Murugan NJ, et al. Combined therapeutic use of oral alitretinoin and narrowband ultraviolet-B therapy in the treatment of Hailey-Hailey disease. Dermatol Rep. 2014;6:5604.

- Mizuno K, Hamada T, Hasimoto T, et al. Successful treatment with narrow-band UVB therapy for a case of generalized Hailey-Hailey disease with a novel splice-site mutation in ATP2C1 gene. Dermatol Ther. 2014;27:233-235.

- Thappa DM. The isomorphic phenomenon of Koebner. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2004;70:187-189.

To the Editor:

Hailey-Hailey disease (HHD), also known as benign familial pemphigus, is an uncommon autosomal-dominant skin disease.1 Defects in the ATPase type 2C member 1 gene, ATP2C1, result in abnormal intracellular epidermal adherence, and patients experience recurring blisters in skin folds. Longitudinal white streaks of the fingernails also may be present.1 The illness does not appear until puberty and is heightened by the second or third decade of life. Family history often suggests the presence of disease.2 Misdiagnosis of HHD occurs because of a wide spectrum of presentations. The presence of superimposed infections and carcinomas may both obscure and exacerbate this disease.2

Herpes simplex viruse types 1 and 2 (HSV-1 and HSV-2) are DNA viruses that cause common recurrent diseases. Usually, HSV-1 is associated with infection of the mouth and HSV-2 is associated with infection of the genitalia.3 Longitudinal cutaneous lesions manifest as grouped vesicles on an erythematous base. Tzanck smear of herpetic vesicles will reveal the presence of multinucleated giant cells. A direct fluorescent antibody technique also may be used to confirm the diagnosis.3

Erythrodermic HHD disease is a rare condition; moreover, there are only a few reported cases with coexistence of HHD and HSV in the literature.3-6 We report a rare presentation of erythrodermic HHD and coexistent psoriasis with HSV superinfection.

A 69-year-old man presented to an outpatient dermatology clinic for evaluation and treatment of a rash on the scalp, face, back, and lower legs. The patient confirmed a dandruff diagnosis on the scalp and face as well as psoriasis on the trunk and extremities for the last 45 years. He described a history of successful treatment with topical agents and UV light therapy. A family history revealed that the patient’s father and 1 of 2 siblings had a similar rash and “skin problems.” The patient had a medical history of thyroid cancer treated with radiation treatment and a partial thyroidectomy 35 years prior to the current presentation as well as incompletely treated chronic hepatitis C.

A search of medical records revealed a punch biopsy from the posterior neck that demonstrated an acantholytic dyskeratosis with suprabasal acantholysis. Clinicians were unable to differentiate if it was Darier disease (DAR) or HHD. Treatment of the patient’s seborrheic dermatitis and acantholytic disorder was successful at that time with ketoconazole shampoo, ketoconazole cream, desonide cream, and triamcinolone cream. The patient remained stable for 5 years before presenting again to the dermatology clinic for worsening rash despite topical therapies.

At the current presentation, physical examination at the outpatient dermatology clinic revealed few scaly, erythematous, eroded papules distributed on the mid-back; erythematous greasy scaling on the scalp, face, and chest; and pink scaly plaques with white-silvery scale on the anterior lower legs. Histopathology of a specimen from the right mid-back demonstrated acantholysis with suprabasal clefting, hyperkeratosis, and parakeratosis with no dyskeratotic cells identified. The pathologic differential diagnosis included primary acantholytic processes including Grover disease, DAR, HHD, and pemphigus. Pathology from the right shin demonstrated acanthosis, confluent parakeratosis with associated decreased granular cell layer and collections of neutrophils within the stratum corneum, spongiosis, and superficial dermal perivascular chronic inflammation with focal exocytosis and dilated blood vessels in the papillary dermis. The clinical and pathological diagnosis on the lower legs was consistent with psoriasis. Diagnoses of seborrheic dermatitis, psoriasis on the lower legs, and HHD vs DAR on the back and chest were made. The patient was instructed to continue ketoconazole shampoo, ketoconazole cream, and desonide for seborrheic dermatitis; fluocinonide ointment 0.05% to the lower legs for psoriasis; and triamcinolone cream and a bland moisturizer to the back and chest for HHD.

Over the ensuing months, the rash worsened with erythema and scaling affecting more than half of the body surface area. Topical corticosteroids and bland emollients resulted in minimal success. Biologics and acitretin were considered for the psoriasiform dermatitis but avoided due to the patient’s medical history of thyroid cancer and chronic hepatitis C infection. Because the patient described prior success with UV light therapy for psoriasis, he requested light therapy. A subsequent trial of narrowband UVB light therapy initially improved some of the psoriasiform dermatitis on the trunk and extremities; however, after 4 weeks of treatment, the patient described pain in some of the skin and felt he was burned by minimal exposure to light therapy on one particular visit, which caused him to stop light therapy.

Approximately 2 weeks later, the patient presented to the emergency department stating his psoriasis was infected; he was diagnosed with psoriasis with secondary cellulitis and received intravenous vancomycin and piperacillin-tazobactam, with bacterial cultures demonstrating Corynebacterium and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Some improvement was noted in the patient’s skin after antibiotics were initiated, but he continued to describe worsening “burning and pain” throughout the psoriasis lesions. The patient’s care was transferred to the Veterans Affairs hospital where a dermatology inpatient consultation was placed.

Our initial dermatologic examination revealed generalized scaly erythroderma on the neck, trunk, and extremities, sparing the face, palms, and soles (Figure 1). Multiple crusted and intact vesicles also were present overlying the erythematous plaques on the chest, back, and proximal extremities, most grouped in clusters. The patient endorsed new symptoms of pain and burning. Tzanck smear from the abdomen along with shave biopsies from the left flank and right abdomen were performed, and intravenous acyclovir was initiated immediately after these procedures.

Viral cultures were taken but were incorrectly processed by the laboratory. Tzanck smear showed severe acute inflammation with numerous neutrophils, multinucleated giant cells with viral nuclear changes, and positive immunostaining for HSV and negative immunostaining for herpes zoster. Both pathology specimens revealed an intense acute mixed, mainly neutrophilic, inflammatory infiltrate extending into the deeper dermis as well as distorted and necrotic hair follicles, some of which displayed multinucleated epithelial cells with margination of chromatin that were positive for both HSV-1 and HSV-2 and negative for herpes zoster (Figure 2). The positivity of both HSV strains might represent co-infection or could be a cross-reaction of antibodies used in immunohistochemistry to the HSV antigens. There was acantholysis surrounding the ulceration and extending through the full thickness of the epidermis with a dilapidated brick wall pattern (Figure 3) as well as negative immunohistochemical staining for HSV-1 and HSV-2 antigens. The clinical and histological picture together, along with prior clinical and pathological reports, confirmed the diagnoses of acute erythrodermic HHD with HSV superinfection.

The patient’s condition and pain improved within 24 hours on intravenous acyclovir. On the third day, his lesions were resolving and symptoms improved, so he was transitioned to oral acyclovir and discharged from the hospital. Follow-up in the dermatology outpatient clinic 1 week later revealed that all vesicles and papules had cleared, but the patient was still erythrodermic. Because HHD cannot always be distinguished histologically from other forms of pemphigus but yields a negative immunofluorescence, direct immunofluorescence and indirect immunofluorescence were obtained upon patient follow-up in the clinic and were both negative. Hepatitis C viral loads were undetectable. Consultations to gastroenterology and oncology teams were placed for consideration of systemic agents, and the patient was initiated on oral acitretin 25 mg daily, along with clobetasol as adjuvant therapy for any residual skin plaques. The laboratory results were closely monitored. Within 4 weeks after starting acitretin, the patient’s erythroderma had completely resolved. The patient has remained stable since then, except for one episode of secondary Staphylococcus infection that cleared on oral antibiotics. The patient remains stable and clear on oral acitretin 25 mg daily, with concomitant desonide cream and fluocinonide ointment as needed.

Hailey-Hailey disease is characterized by recurrent episodes of erythema, blisters, and plaques localized to intertriginous and perianal areas.1,2 Patients display a spectrum of lesions that vary in severity.8 Typical histologic examination reveals a dilapidated brick wall appearance. Pathology of well-developed lesions will show suprabasal acantholysis with minimal dyskeratosis.2

The generalized form of HHD is an extremely rare variant of the disease.10 Generalized HHD may resemble acute hypersensitivity reaction, erythema multiforme, and toxic epidermal necrolysis.1 Chronic diseases, such as psoriasis (as in this patient), also may contribute to a clinically confusing picture.8 Hailey-Hailey disease and psoriasis are thought to occasionally koebnerize (isomorphic response) to areas of trauma.16 Our patient experienced widespread erythematous papules and plaques not restricted to skin folds. His skin lesions continued to worsen over several months progressing to erythroderma. The presence of suprabasal acantholysis in a dilapidated brick wall pattern, along with the patient’s history, prior pathology reports, clinical picture, and negative direct immunofluorescence and indirect immunofluorescence studies helped to confirm the diagnosis of erythrodermic HHD.

Hailey-Hailey disease is caused by heterozygous mutations in the ATP2C1 gene on chromosome 3q21-24 coding for a Golgi ATPase called SPCA1 (secretory pathway calcium/manganese-ATPase).9 Subsequent disturbances in cytosolic-Golgi calcium concentrations interfere with epidermal keratinocyte adherence resulting in acantholytic disease. Studies of interfamilial and intrafamilial mutations fail to pinpoint a common mutation pattern among patients with generalized phenotypes,9 which further supports theories that intrinsic or extrinsic factors such as friction, heat, radiation, contact allergens, and infection affect the severity of HHD disease and not the type of mutation.3,9

Generalization of HHD is likely caused by nonspecific triggers in an already genetically disturbed epidermis.10 Interrupted epithelial function exposes skin to infections that exacerbate the underlying disease. Superimposing bacterial infections are commonly reported in HHD. Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, and Candida species colonize the skin and aggravate the disease.11 Much less commonly, HSV superinfection can complicate HHD.3-7 No data are currently available about the frequency or incidence of Herpesviridae in HHD.7 Some studies suggest that UVB light therapy can be an exacerbating factor in DAR and some but not all HHD patients,12,13 while other case reports14,15 document clinically improved responses using phototherapy for patients with HHD. Clinicians should remain suspicious and evaluate for HSV infection in refractory or sudden exacerbation of HHD.7 Furthermore, coexistent psoriasis and HHD also is a rare entity but has been described,8 which illustrates the importance of not attributing all skin manifestations to a previously diagnosed disorder but instead keeping an open mind in case new dermatologic conditions present themselves at a later time.

We present a rare case of erythrodermic HHD and coexistent psoriasis with HSV superinfection. We hope to draw awareness to this association of generalized HHD with both HSV and psoriasis to help clinicians make the correct diagnosis promptly in similar cases in the future.

To the Editor:

Hailey-Hailey disease (HHD), also known as benign familial pemphigus, is an uncommon autosomal-dominant skin disease.1 Defects in the ATPase type 2C member 1 gene, ATP2C1, result in abnormal intracellular epidermal adherence, and patients experience recurring blisters in skin folds. Longitudinal white streaks of the fingernails also may be present.1 The illness does not appear until puberty and is heightened by the second or third decade of life. Family history often suggests the presence of disease.2 Misdiagnosis of HHD occurs because of a wide spectrum of presentations. The presence of superimposed infections and carcinomas may both obscure and exacerbate this disease.2

Herpes simplex viruse types 1 and 2 (HSV-1 and HSV-2) are DNA viruses that cause common recurrent diseases. Usually, HSV-1 is associated with infection of the mouth and HSV-2 is associated with infection of the genitalia.3 Longitudinal cutaneous lesions manifest as grouped vesicles on an erythematous base. Tzanck smear of herpetic vesicles will reveal the presence of multinucleated giant cells. A direct fluorescent antibody technique also may be used to confirm the diagnosis.3

Erythrodermic HHD disease is a rare condition; moreover, there are only a few reported cases with coexistence of HHD and HSV in the literature.3-6 We report a rare presentation of erythrodermic HHD and coexistent psoriasis with HSV superinfection.

A 69-year-old man presented to an outpatient dermatology clinic for evaluation and treatment of a rash on the scalp, face, back, and lower legs. The patient confirmed a dandruff diagnosis on the scalp and face as well as psoriasis on the trunk and extremities for the last 45 years. He described a history of successful treatment with topical agents and UV light therapy. A family history revealed that the patient’s father and 1 of 2 siblings had a similar rash and “skin problems.” The patient had a medical history of thyroid cancer treated with radiation treatment and a partial thyroidectomy 35 years prior to the current presentation as well as incompletely treated chronic hepatitis C.

A search of medical records revealed a punch biopsy from the posterior neck that demonstrated an acantholytic dyskeratosis with suprabasal acantholysis. Clinicians were unable to differentiate if it was Darier disease (DAR) or HHD. Treatment of the patient’s seborrheic dermatitis and acantholytic disorder was successful at that time with ketoconazole shampoo, ketoconazole cream, desonide cream, and triamcinolone cream. The patient remained stable for 5 years before presenting again to the dermatology clinic for worsening rash despite topical therapies.

At the current presentation, physical examination at the outpatient dermatology clinic revealed few scaly, erythematous, eroded papules distributed on the mid-back; erythematous greasy scaling on the scalp, face, and chest; and pink scaly plaques with white-silvery scale on the anterior lower legs. Histopathology of a specimen from the right mid-back demonstrated acantholysis with suprabasal clefting, hyperkeratosis, and parakeratosis with no dyskeratotic cells identified. The pathologic differential diagnosis included primary acantholytic processes including Grover disease, DAR, HHD, and pemphigus. Pathology from the right shin demonstrated acanthosis, confluent parakeratosis with associated decreased granular cell layer and collections of neutrophils within the stratum corneum, spongiosis, and superficial dermal perivascular chronic inflammation with focal exocytosis and dilated blood vessels in the papillary dermis. The clinical and pathological diagnosis on the lower legs was consistent with psoriasis. Diagnoses of seborrheic dermatitis, psoriasis on the lower legs, and HHD vs DAR on the back and chest were made. The patient was instructed to continue ketoconazole shampoo, ketoconazole cream, and desonide for seborrheic dermatitis; fluocinonide ointment 0.05% to the lower legs for psoriasis; and triamcinolone cream and a bland moisturizer to the back and chest for HHD.

Over the ensuing months, the rash worsened with erythema and scaling affecting more than half of the body surface area. Topical corticosteroids and bland emollients resulted in minimal success. Biologics and acitretin were considered for the psoriasiform dermatitis but avoided due to the patient’s medical history of thyroid cancer and chronic hepatitis C infection. Because the patient described prior success with UV light therapy for psoriasis, he requested light therapy. A subsequent trial of narrowband UVB light therapy initially improved some of the psoriasiform dermatitis on the trunk and extremities; however, after 4 weeks of treatment, the patient described pain in some of the skin and felt he was burned by minimal exposure to light therapy on one particular visit, which caused him to stop light therapy.

Approximately 2 weeks later, the patient presented to the emergency department stating his psoriasis was infected; he was diagnosed with psoriasis with secondary cellulitis and received intravenous vancomycin and piperacillin-tazobactam, with bacterial cultures demonstrating Corynebacterium and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Some improvement was noted in the patient’s skin after antibiotics were initiated, but he continued to describe worsening “burning and pain” throughout the psoriasis lesions. The patient’s care was transferred to the Veterans Affairs hospital where a dermatology inpatient consultation was placed.

Our initial dermatologic examination revealed generalized scaly erythroderma on the neck, trunk, and extremities, sparing the face, palms, and soles (Figure 1). Multiple crusted and intact vesicles also were present overlying the erythematous plaques on the chest, back, and proximal extremities, most grouped in clusters. The patient endorsed new symptoms of pain and burning. Tzanck smear from the abdomen along with shave biopsies from the left flank and right abdomen were performed, and intravenous acyclovir was initiated immediately after these procedures.

Viral cultures were taken but were incorrectly processed by the laboratory. Tzanck smear showed severe acute inflammation with numerous neutrophils, multinucleated giant cells with viral nuclear changes, and positive immunostaining for HSV and negative immunostaining for herpes zoster. Both pathology specimens revealed an intense acute mixed, mainly neutrophilic, inflammatory infiltrate extending into the deeper dermis as well as distorted and necrotic hair follicles, some of which displayed multinucleated epithelial cells with margination of chromatin that were positive for both HSV-1 and HSV-2 and negative for herpes zoster (Figure 2). The positivity of both HSV strains might represent co-infection or could be a cross-reaction of antibodies used in immunohistochemistry to the HSV antigens. There was acantholysis surrounding the ulceration and extending through the full thickness of the epidermis with a dilapidated brick wall pattern (Figure 3) as well as negative immunohistochemical staining for HSV-1 and HSV-2 antigens. The clinical and histological picture together, along with prior clinical and pathological reports, confirmed the diagnoses of acute erythrodermic HHD with HSV superinfection.

The patient’s condition and pain improved within 24 hours on intravenous acyclovir. On the third day, his lesions were resolving and symptoms improved, so he was transitioned to oral acyclovir and discharged from the hospital. Follow-up in the dermatology outpatient clinic 1 week later revealed that all vesicles and papules had cleared, but the patient was still erythrodermic. Because HHD cannot always be distinguished histologically from other forms of pemphigus but yields a negative immunofluorescence, direct immunofluorescence and indirect immunofluorescence were obtained upon patient follow-up in the clinic and were both negative. Hepatitis C viral loads were undetectable. Consultations to gastroenterology and oncology teams were placed for consideration of systemic agents, and the patient was initiated on oral acitretin 25 mg daily, along with clobetasol as adjuvant therapy for any residual skin plaques. The laboratory results were closely monitored. Within 4 weeks after starting acitretin, the patient’s erythroderma had completely resolved. The patient has remained stable since then, except for one episode of secondary Staphylococcus infection that cleared on oral antibiotics. The patient remains stable and clear on oral acitretin 25 mg daily, with concomitant desonide cream and fluocinonide ointment as needed.

Hailey-Hailey disease is characterized by recurrent episodes of erythema, blisters, and plaques localized to intertriginous and perianal areas.1,2 Patients display a spectrum of lesions that vary in severity.8 Typical histologic examination reveals a dilapidated brick wall appearance. Pathology of well-developed lesions will show suprabasal acantholysis with minimal dyskeratosis.2

The generalized form of HHD is an extremely rare variant of the disease.10 Generalized HHD may resemble acute hypersensitivity reaction, erythema multiforme, and toxic epidermal necrolysis.1 Chronic diseases, such as psoriasis (as in this patient), also may contribute to a clinically confusing picture.8 Hailey-Hailey disease and psoriasis are thought to occasionally koebnerize (isomorphic response) to areas of trauma.16 Our patient experienced widespread erythematous papules and plaques not restricted to skin folds. His skin lesions continued to worsen over several months progressing to erythroderma. The presence of suprabasal acantholysis in a dilapidated brick wall pattern, along with the patient’s history, prior pathology reports, clinical picture, and negative direct immunofluorescence and indirect immunofluorescence studies helped to confirm the diagnosis of erythrodermic HHD.

Hailey-Hailey disease is caused by heterozygous mutations in the ATP2C1 gene on chromosome 3q21-24 coding for a Golgi ATPase called SPCA1 (secretory pathway calcium/manganese-ATPase).9 Subsequent disturbances in cytosolic-Golgi calcium concentrations interfere with epidermal keratinocyte adherence resulting in acantholytic disease. Studies of interfamilial and intrafamilial mutations fail to pinpoint a common mutation pattern among patients with generalized phenotypes,9 which further supports theories that intrinsic or extrinsic factors such as friction, heat, radiation, contact allergens, and infection affect the severity of HHD disease and not the type of mutation.3,9

Generalization of HHD is likely caused by nonspecific triggers in an already genetically disturbed epidermis.10 Interrupted epithelial function exposes skin to infections that exacerbate the underlying disease. Superimposing bacterial infections are commonly reported in HHD. Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, and Candida species colonize the skin and aggravate the disease.11 Much less commonly, HSV superinfection can complicate HHD.3-7 No data are currently available about the frequency or incidence of Herpesviridae in HHD.7 Some studies suggest that UVB light therapy can be an exacerbating factor in DAR and some but not all HHD patients,12,13 while other case reports14,15 document clinically improved responses using phototherapy for patients with HHD. Clinicians should remain suspicious and evaluate for HSV infection in refractory or sudden exacerbation of HHD.7 Furthermore, coexistent psoriasis and HHD also is a rare entity but has been described,8 which illustrates the importance of not attributing all skin manifestations to a previously diagnosed disorder but instead keeping an open mind in case new dermatologic conditions present themselves at a later time.

We present a rare case of erythrodermic HHD and coexistent psoriasis with HSV superinfection. We hope to draw awareness to this association of generalized HHD with both HSV and psoriasis to help clinicians make the correct diagnosis promptly in similar cases in the future.

- Chave TA, Milligan A. Acute generalized Hailey-Hailey disease. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2002;27:290-292.

- Mohr MR, Erdag G, Shada Al, et al. Two patients with Hailey-Hailey disease, multiple primary melanomas, and other cancers. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:211-215.

- Lee GM, Kim YM, Lee SY, et al. A case of eczema herpeticum with Hailey-Hailey Disease. Ann Dermatol. 2009;21:311-314.

- Zaim MT, Bickers DR. Herpes simplex associated with Hailey-Hailey disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:701-702.

- Peppiatt T, Keefe M, White JE. Hailey-Hailey disease-exacerbation by herpes simplex virus and patch tests. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2006;17:201-202.

- Almeida L, Grossman ME. Benign familial pemphigus complicated by herpes simplex virus. Cutis. 1989;44:261-262.

- Nikkels AF, Delvenne P, Herfs M, et al. Occult herpes simplex virus colonization of bullous dermatitides. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2008;9:163-168.

- Chao SC, Lee JY, Wu MC, et al. A novel splice mutation in the ATP2C1 gene in a woman with concomitant psoriasis vulgaris and disseminated Hailey-Hailey disease. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:947-951.

- Ikeda S, Shigihara T, Mayuzumi N, et al. Mutations of ATP2C1 in Japanese patients with Hailey-Hailey disease: intrafamilial and interfamilial phenotype variations and lack of correlation with mutation patterns. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;117:1654-1656.

- Marsch W, Stuttgen G. Generalized Hailey-Hailey disease. Br J Dermatol. 1978;99:553-559.

- Friedman-Birnbaum R, Haim S, Marcus S. Generalized familial benign chronic pemphigus. Dermatologica. 1980;161:112-115.

- Richard G, Linse R, Harth W. Hailey-Hailey disease. early detection of heterozygotes by an ultraviolet provocation tests—clinical relevance of the method. Hautarzt. 1993;44:376-379.

- Mayuzumi N, Ikeda S, Kawada H, et al. Effects of ultraviolet B irradiation, proinflammatory cytokines and raised extracellular calcium concentration on the expression of ATP2A2 and ATP2C1. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:697-701.

- Vanderbeck KA, Giroux L, Murugan NJ, et al. Combined therapeutic use of oral alitretinoin and narrowband ultraviolet-B therapy in the treatment of Hailey-Hailey disease. Dermatol Rep. 2014;6:5604.

- Mizuno K, Hamada T, Hasimoto T, et al. Successful treatment with narrow-band UVB therapy for a case of generalized Hailey-Hailey disease with a novel splice-site mutation in ATP2C1 gene. Dermatol Ther. 2014;27:233-235.

- Thappa DM. The isomorphic phenomenon of Koebner. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2004;70:187-189.

- Chave TA, Milligan A. Acute generalized Hailey-Hailey disease. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2002;27:290-292.

- Mohr MR, Erdag G, Shada Al, et al. Two patients with Hailey-Hailey disease, multiple primary melanomas, and other cancers. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:211-215.

- Lee GM, Kim YM, Lee SY, et al. A case of eczema herpeticum with Hailey-Hailey Disease. Ann Dermatol. 2009;21:311-314.

- Zaim MT, Bickers DR. Herpes simplex associated with Hailey-Hailey disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:701-702.

- Peppiatt T, Keefe M, White JE. Hailey-Hailey disease-exacerbation by herpes simplex virus and patch tests. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2006;17:201-202.

- Almeida L, Grossman ME. Benign familial pemphigus complicated by herpes simplex virus. Cutis. 1989;44:261-262.

- Nikkels AF, Delvenne P, Herfs M, et al. Occult herpes simplex virus colonization of bullous dermatitides. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2008;9:163-168.

- Chao SC, Lee JY, Wu MC, et al. A novel splice mutation in the ATP2C1 gene in a woman with concomitant psoriasis vulgaris and disseminated Hailey-Hailey disease. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:947-951.

- Ikeda S, Shigihara T, Mayuzumi N, et al. Mutations of ATP2C1 in Japanese patients with Hailey-Hailey disease: intrafamilial and interfamilial phenotype variations and lack of correlation with mutation patterns. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;117:1654-1656.

- Marsch W, Stuttgen G. Generalized Hailey-Hailey disease. Br J Dermatol. 1978;99:553-559.

- Friedman-Birnbaum R, Haim S, Marcus S. Generalized familial benign chronic pemphigus. Dermatologica. 1980;161:112-115.

- Richard G, Linse R, Harth W. Hailey-Hailey disease. early detection of heterozygotes by an ultraviolet provocation tests—clinical relevance of the method. Hautarzt. 1993;44:376-379.

- Mayuzumi N, Ikeda S, Kawada H, et al. Effects of ultraviolet B irradiation, proinflammatory cytokines and raised extracellular calcium concentration on the expression of ATP2A2 and ATP2C1. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:697-701.

- Vanderbeck KA, Giroux L, Murugan NJ, et al. Combined therapeutic use of oral alitretinoin and narrowband ultraviolet-B therapy in the treatment of Hailey-Hailey disease. Dermatol Rep. 2014;6:5604.

- Mizuno K, Hamada T, Hasimoto T, et al. Successful treatment with narrow-band UVB therapy for a case of generalized Hailey-Hailey disease with a novel splice-site mutation in ATP2C1 gene. Dermatol Ther. 2014;27:233-235.

- Thappa DM. The isomorphic phenomenon of Koebner. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2004;70:187-189.

Practice Points

- Misdiagnosis of Hailey-Hailey disease (HHD) occurs because of a wide spectrum of presentations.

- Hailey-Hailey disease and psoriasis are thought to occasionally koebnerize (isomorphic response) to areas of trauma.

- Clinicians should remain suspicious and evaluate for herpes simplex virus infection in refractory or sudden exacerbation of HHD.

Phytophotodermatitis in a Butterfly Enthusiast Induced by Common Rue

To the Editor:

Phytophotodermatitis is common in dermatology during the summer months, especially in individuals who spend time outdoors; however, identification of the offending plant can be challenging. We report a case of phytophotodermatitis in which the causative plant, common rue, was not identified until it was revealed that the patient was a butterfly enthusiast.

A 60-year-old woman presented to the outpatient dermatology clinic in late summer for a routine skin examination. An eruption was noted over the right thigh and knee that had first appeared approximately 2 weeks prior. The rash started as pruritic blisters but gradually progressed to erythema and then eventually to brown markings, which were observed at the current presentation. Physical examination revealed hyperpigmented, brown, streaky, linear patches and plaques over the right thigh, knee, and lower leg (Figure). When asked about her hobbies, the patient reported an affinity for butterflies and noted that she attracts them with specific species of plants in her garden. She recalled recently planting the herb of grace, or common rue, to attract the giant swallowtail butterfly (Papilio cresphontes). Upon further inquiry, she remembered working in the garden on her knees and digging up roots near the common rue plant while wearing shorts approximately 2 weeks prior to the current presentation. Given the streaky linear pattern of the eruption along with recent sun exposure and exposure to the common rue plant, a diagnosis of phytophotodermatitis was made. No further treatment was sought, as the eruption was not bothersome to her. She was intrigued that the common rue plant had caused the dermatitis and planned on taking proper precautions when working near the plant in the future.

In this case, the observed phototoxic skin findings resulted from exposure to common rue (Ruta graveolens),a pungently scented evergreen shrub native to the Mediterranean region and a member of the Rutaceae family. Extracts have been used in homeopathic practices for bruises, sprains, headache, neck stiffness, rheumatologic pain, neuralgia, stomach problems, and phlebitis, as well as in seasonings, soaps, creams, and perfumes.1 The most commonly encountered plants known to cause phytophotodermatitis belong to the Apiaceae and Rutaceae families.2 Members of Apiaceae include angelica, celery, dill, fennel, hogweed, parsley, and parsnip. Aside from the common rue plant, the Rutaceae family also includes bergamot orange, bitter orange, burning bush (or gas plant), grapefruit, lemon, and lime. Other potential offending agents are fig, mustard, buttercup, St. John’s wort, and scurfpea. The phototoxic properties are due to furocoumarins, which include psoralens and angelicins. They are inert until activated by UVA radiation, which inflicts direct cellular damage, causing vacuolization and apoptosis of keratinocytes, similar to a sunburn.3 Clinical findings typically present 24 hours after sun exposure with erythema, edema, pain, and occasionally vesicles or bullae in severe cases. Unlike sunburn, lesions often present in linear, streaky, or bizarre patterns, reflective of the direct contact with the plant. The lesions eventually transition to hyperpigmentation, which may take months to years to resolve.

Other considerations in cases of suspected phytophotodermatitis include polymorphic light eruption, actinic prurigo, hydroa vacciniforme, chronic actinic dermatitis, solar urticaria, drug reactions, porphyria, Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome, lupus erythematosus, and dermatomyositis.4 Clinicians should suspect phytophotodermatitis with phototoxic findings in bartenders, citrus farm workers, gardeners, chefs, and kitchen workers, especially those handling limes and celery. As in our case, phytophotodermatitis also should be considered in butterfly enthusiasts trying to attract the giant swallowtail butterfly. The caterpillars feed on the leaves of the common rue plant, one of a select few plants that giant swallowtail butterflies use as a host due to its bitter leaves that aid in avoiding predators.5

This case illustrates a unique perspective of phytophotodermatitis, as butterfly enthusiasm is not commonly reported in association with the common rue plant with respect to phytophotodermatitis. This case underscores the importance of inquiring about patients’ professions and hobbies, both in dermatology and other specialties.

- Atta AH, Alkofahi A. Anti-nociceptive and anti-inflammatory effects of some Jordanian medicinal plant extracts. J Ethnopharmacol. 1998;60:117-124.

- McGovern TW. Dermatoses due to plants. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. 2nd ed. Edinburgh, Scotland: Mosby; 2007:265-283.

- Hawk JLM, Calonje E. The photosensitivity disorders. In: Elder DE, ed. Lever’s Histopathology of the Skin. 9th ed. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2005:345-353.

- Lim HW. Abnormal responses to ultraviolet radiation: photosensitivity induced by exogenous agents. In: Wolff K, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2012:1066-1074.

- McAuslane H. Giant swallowtail. University of Florida Department of Entomology and Nematology Featured Creatures website. http://entnemdept.ufl.edu/creatures/citrus/giantswallowtail.htm. Revised January 2018. Accessed April 10, 2020.

To the Editor:

Phytophotodermatitis is common in dermatology during the summer months, especially in individuals who spend time outdoors; however, identification of the offending plant can be challenging. We report a case of phytophotodermatitis in which the causative plant, common rue, was not identified until it was revealed that the patient was a butterfly enthusiast.

A 60-year-old woman presented to the outpatient dermatology clinic in late summer for a routine skin examination. An eruption was noted over the right thigh and knee that had first appeared approximately 2 weeks prior. The rash started as pruritic blisters but gradually progressed to erythema and then eventually to brown markings, which were observed at the current presentation. Physical examination revealed hyperpigmented, brown, streaky, linear patches and plaques over the right thigh, knee, and lower leg (Figure). When asked about her hobbies, the patient reported an affinity for butterflies and noted that she attracts them with specific species of plants in her garden. She recalled recently planting the herb of grace, or common rue, to attract the giant swallowtail butterfly (Papilio cresphontes). Upon further inquiry, she remembered working in the garden on her knees and digging up roots near the common rue plant while wearing shorts approximately 2 weeks prior to the current presentation. Given the streaky linear pattern of the eruption along with recent sun exposure and exposure to the common rue plant, a diagnosis of phytophotodermatitis was made. No further treatment was sought, as the eruption was not bothersome to her. She was intrigued that the common rue plant had caused the dermatitis and planned on taking proper precautions when working near the plant in the future.

In this case, the observed phototoxic skin findings resulted from exposure to common rue (Ruta graveolens),a pungently scented evergreen shrub native to the Mediterranean region and a member of the Rutaceae family. Extracts have been used in homeopathic practices for bruises, sprains, headache, neck stiffness, rheumatologic pain, neuralgia, stomach problems, and phlebitis, as well as in seasonings, soaps, creams, and perfumes.1 The most commonly encountered plants known to cause phytophotodermatitis belong to the Apiaceae and Rutaceae families.2 Members of Apiaceae include angelica, celery, dill, fennel, hogweed, parsley, and parsnip. Aside from the common rue plant, the Rutaceae family also includes bergamot orange, bitter orange, burning bush (or gas plant), grapefruit, lemon, and lime. Other potential offending agents are fig, mustard, buttercup, St. John’s wort, and scurfpea. The phototoxic properties are due to furocoumarins, which include psoralens and angelicins. They are inert until activated by UVA radiation, which inflicts direct cellular damage, causing vacuolization and apoptosis of keratinocytes, similar to a sunburn.3 Clinical findings typically present 24 hours after sun exposure with erythema, edema, pain, and occasionally vesicles or bullae in severe cases. Unlike sunburn, lesions often present in linear, streaky, or bizarre patterns, reflective of the direct contact with the plant. The lesions eventually transition to hyperpigmentation, which may take months to years to resolve.

Other considerations in cases of suspected phytophotodermatitis include polymorphic light eruption, actinic prurigo, hydroa vacciniforme, chronic actinic dermatitis, solar urticaria, drug reactions, porphyria, Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome, lupus erythematosus, and dermatomyositis.4 Clinicians should suspect phytophotodermatitis with phototoxic findings in bartenders, citrus farm workers, gardeners, chefs, and kitchen workers, especially those handling limes and celery. As in our case, phytophotodermatitis also should be considered in butterfly enthusiasts trying to attract the giant swallowtail butterfly. The caterpillars feed on the leaves of the common rue plant, one of a select few plants that giant swallowtail butterflies use as a host due to its bitter leaves that aid in avoiding predators.5

This case illustrates a unique perspective of phytophotodermatitis, as butterfly enthusiasm is not commonly reported in association with the common rue plant with respect to phytophotodermatitis. This case underscores the importance of inquiring about patients’ professions and hobbies, both in dermatology and other specialties.

To the Editor:

Phytophotodermatitis is common in dermatology during the summer months, especially in individuals who spend time outdoors; however, identification of the offending plant can be challenging. We report a case of phytophotodermatitis in which the causative plant, common rue, was not identified until it was revealed that the patient was a butterfly enthusiast.

A 60-year-old woman presented to the outpatient dermatology clinic in late summer for a routine skin examination. An eruption was noted over the right thigh and knee that had first appeared approximately 2 weeks prior. The rash started as pruritic blisters but gradually progressed to erythema and then eventually to brown markings, which were observed at the current presentation. Physical examination revealed hyperpigmented, brown, streaky, linear patches and plaques over the right thigh, knee, and lower leg (Figure). When asked about her hobbies, the patient reported an affinity for butterflies and noted that she attracts them with specific species of plants in her garden. She recalled recently planting the herb of grace, or common rue, to attract the giant swallowtail butterfly (Papilio cresphontes). Upon further inquiry, she remembered working in the garden on her knees and digging up roots near the common rue plant while wearing shorts approximately 2 weeks prior to the current presentation. Given the streaky linear pattern of the eruption along with recent sun exposure and exposure to the common rue plant, a diagnosis of phytophotodermatitis was made. No further treatment was sought, as the eruption was not bothersome to her. She was intrigued that the common rue plant had caused the dermatitis and planned on taking proper precautions when working near the plant in the future.