User login

Tender Annular Plaque on the Thigh

The Diagnosis: Ecthyma Gangrenosum

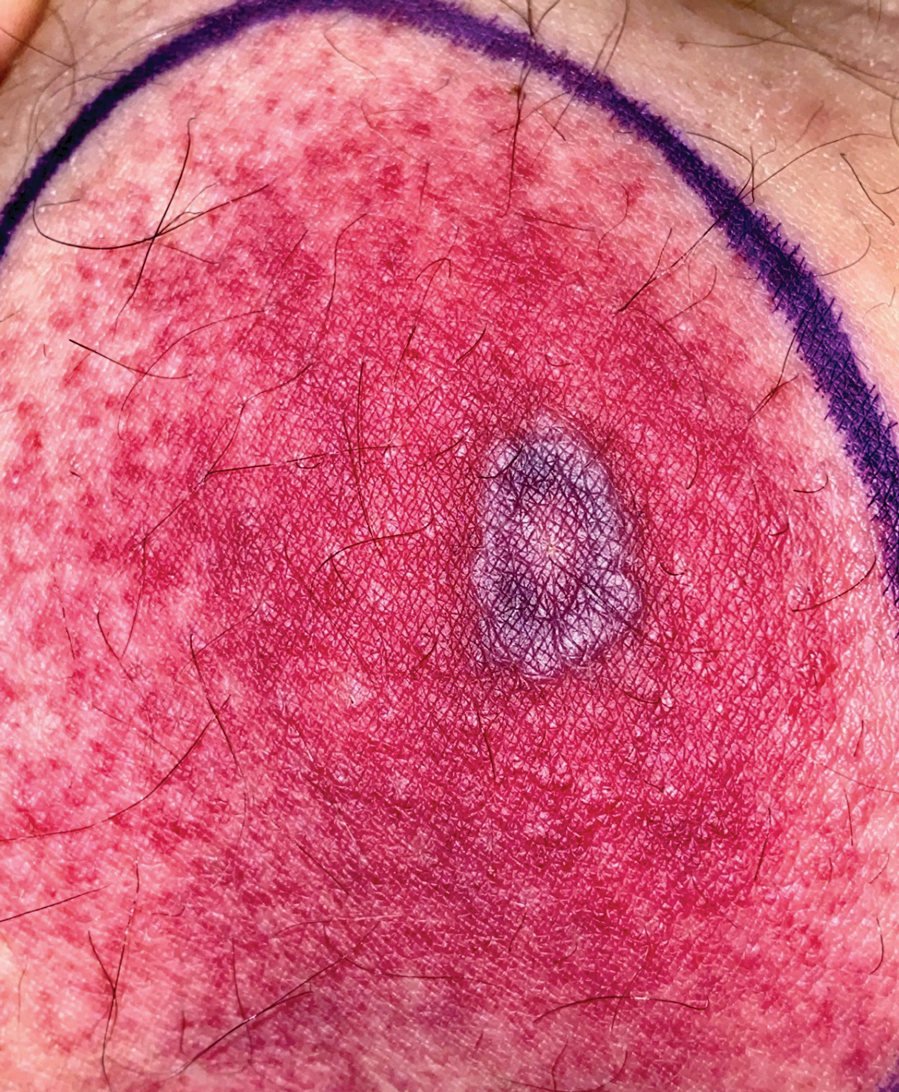

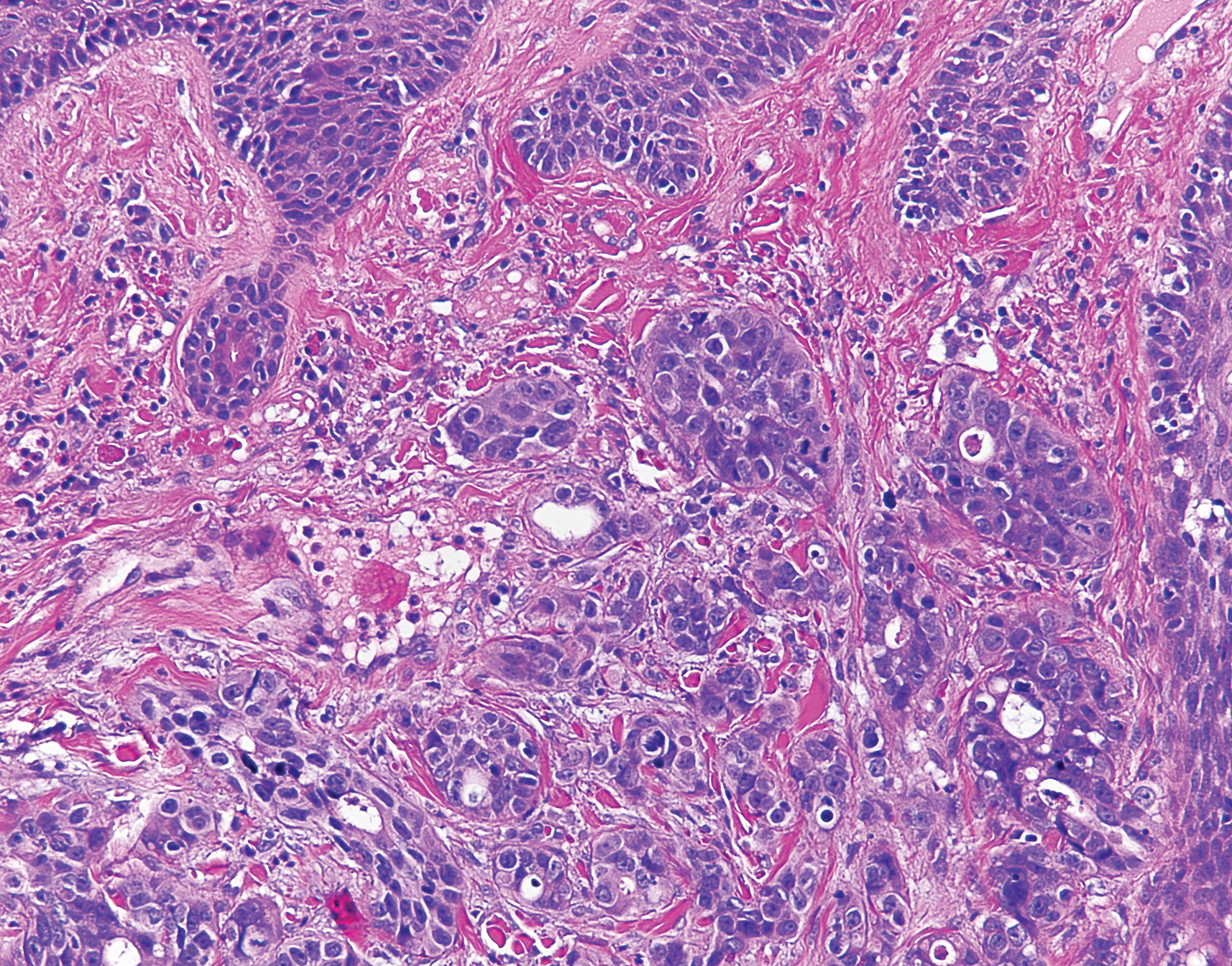

Histopathology revealed basophilic bacterial rods around necrotic vessels with thrombosis and edema (Figure). Blood and tissue cultures grew Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Based on the histopathology and clinical presentation, a diagnosis of P aeruginosa–associated ecthyma gangrenosum (EG) was made. The patient’s symptoms resolved with intravenous cefepime, and he later was transitioned to oral levofloxacin for outpatient treatment.

Ecthyma gangrenosum is an uncommon cutaneous manifestation of bacteremia that most commonly occurs secondary to P aeruginosa in immunocompromised patients, particularly patients with severe neutropenia in the setting of recent chemotherapy.1,2 Ecthyma gangrenosum can occur anywhere on the body, predominantly in moist areas such as the axillae and groin; the arms and legs, such as in our patient, as well as the trunk and face also may be involved.3 Other causes of EG skin lesions include methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, Citrobacter freundii, Escherichia coli, fungi such as Candida, and viruses such as herpes simplex virus.2,4-6 Common predisposing conditions associated with EG include neutropenia, leukemia, HIV, diabetes mellitus, extensive burn wounds, and a history of immunosuppressive medications. It also has been known to occur in otherwise healthy, immunocompetent individuals with no difference in clinical manifestation.2

The diagnosis is clinicopathologic, with initial evaluation including blood and wound cultures as well as a complete blood cell count once EG is suspected. An excisional or punch biopsy is performed for confirmation, showing many gram-negative, rod-shaped bacteria in cases of pseudomonal EG.7 Histopathology is characterized by bacterial perivascular invasion that then leads to secondary arteriole thrombosis, tissue edema, and separation of the epidermis.7,8 Resultant ischemic necrosis results in the classic macroscopic appearance of an erythematous macule that rapidly progresses into a central necrotic lesion surrounded by an erythematous or violaceous halo after undergoing a hemorrhagic bullous stage.1,9 A Wood lamp can be used to expedite the diagnosis, as Pseudomonas bacteria excretes a pigment (pyoverdine) that fluoresces yellowish green.10

Ecthyma gangrenosum can be classified as a primary skin lesion that may or may not be followed by bacteremia or as a lesion secondary to pseudomonal bacteremia.11 Bacteremia has been reported in half of cases, with hematogenous metastasis of the infection, likely in manifestations with multiple bilateral lesions.2 Our patient’s presentation of a single lesion revealed a positive blood culture result. Lesions also can develop by direct inoculation of the epidermis causing local destruction of the surrounding tissue. The nonbacteremic form of EG has been associated with a lower mortality rate of around 15% compared to patients with bacteremia ranging from 38% to 96%.12 The presence of neutropenia is the most important prognostic factor for mortality at the time of diagnosis.13

Prompt empiric therapy should be initiated after obtaining wound and blood cultures in those with infection until the causative organism and its susceptibility are identified. Pseudomonal infections account for 4% of all cases of hospital-acquired bacteremia and are the third leading cause of gram-negative bloodstream infection.7 Initial broad-spectrum antibiotics include antipseudomonal β-lactams (piperacillin-tazobactam), cephalosporins (cefepime), fluoroquinolones (levofloxacin), and carbapenems (imipenem).1,7 Medical therapy alone may be sufficient without requiring extensive surgical debridement to remove necrotic tissue in some patients. Surgical debridement usually is warranted for lesions larger than 10 cm in diameter.3 Our patient was treated with intravenous cefepime with resolution and was followed with outpatient oral levofloxacin as appropriate. A high index of suspicion should be maintained for relapsing pseudomonal EG infection among patients with AIDS, as the reported recurrence rate is 57%.14

Clinically, the differential diagnosis of EG presenting in immunocompromised patients or individuals with underlying malignancy includes pyoderma gangrenosum, papulonecrotic tuberculid, and leukemia cutis. An erythematous rash with central necrosis presenting in a patient with systemic symptoms is pathognomonic for erythema migrans and should be considered as a diagnostic possibility in areas endemic for Lyme disease in the United States, including the northeastern, mid-Atlantic, and north-central regions.15 A thorough history, physical examination, basic laboratory studies, and histopathology are critical to differentiate between these entities with similar macroscopic features. Pyoderma gangrenosum histologically manifests as a noninfectious, deep, suppurative folliculitis with leukocytoclastic vasculitis in 40% of cases.16 Although papulonecrotic tuberculid can present with dermal necrosis resulting from a hypersensitivity reaction to antigenic components of mycobacteria, there typically are granulomatous infiltrates present and a lack of observed organisms on histopathology.17 Although leukemia cutis infrequently occurs in patients diagnosed with leukemia, its salient features on pathology are nodular or diffuse infiltrates of leukemic cells in the dermis and subcutis with a high nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio, often with prominent nucleoli.18 Lyme disease can present in various ways; however, cutaneous involvement in the primary lesion is histologically characterized by a perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate containing plasma cells at the periphery of the expanding annular lesion and eosinophils present at the center.19

- Abdou A, Hassam B. Ecthyma gangrenosum [in French]. Pan Afr Med J. 2018;30:95. doi:10.11604/pamj.2018.30.95.6244

- Vaiman M, Lazarovitch T, Heller L, et al. Ecthyma gangrenosum and ecthyma-like lesions: review article. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2015;34:633-639. doi:10.1007/s10096-014-2277-6

- Vaiman M, Lasarovitch T, Heller L, et al. Ecthyma gangrenosum versus ecthyma-like lesions: should we separate these conditions? Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2015;24:69-72. doi:10.15570 /actaapa.2015.18

- Reich HL, Williams Fadeyi D, Naik NS, et al. Nonpseudomonal ecthyma gangrenosum. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50(5 suppl): S114-S117. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2003.09.019

- Hawkley T, Chang D, Pollard W, et al. Ecthyma gangrenosum caused by Citrobacter freundii [published online July 27, 2017]. BMJ Case Rep. doi:10.1136/bcr-2017-220996

- Santhaseelan RG, Muralidhar V. Non-pseudomonal ecthyma gangrenosum caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in a chronic alcoholic patient [published online August 3, 2017]. BMJ Case Rep. doi:10.1136/bcr-2017-220983m

- Bassetti M, Vena A, Croxatto A, et al. How to manage Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections [published online May 29, 2018]. Drugs Context. 2018;7:212527. doi:10.7573/dic.212527

- Llamas-Velasco M, Alegría V, Santos-Briz Á, et al. Occlusive nonvasculitic vasculopathy. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:637-662. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000000766

- Sarkar S, Patra AK, Mondal M. Ecthyma gangrenosum in the periorbital region in a previously healthy immunocompetent woman without bacteremia. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2016;7:36-39. doi:10.4103/2229-5178.174326

- Ponka D, Baddar F. Wood lamp examination. Can Fam Physician. 2012;58:976.

- Van den Broek PJ, Van der Meer JWM, Kunst MW. The pathogenesis of ecthyma gangrenosum. J Infect. 1979;1:263-267. doi:10.1016 /S0163-4453(79)91329-X

- Downey DM, O’Bryan MC, Burdette SD, et al. Ecthyma gangrenosum in a patient with toxic epidermal necrolysis. J Burn Care Res. 2007;28:198-202. doi:10.1097/BCR.0B013E31802CA481

- Martínez-Longoria CA, Rosales-Solis GM, Ocampo-Garza J, et al. Ecthyma gangrenosum: a report of eight cases. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92:698-700. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20175580

- Khan MO, Montecalvo MA, Davis I, et al. Ecthyma gangrenosum in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Cutis. 2000;66:121-123.

- Nadelman RB, Wormser GP. Lyme borreliosis. Lancet. 1998; 352:557-565.

- Su WP, Schroeter AL, Perry HO, et al. Histopathologic and immunopathologic study of pyoderma gangrenosum. J Cutan Pathol. 1986;13:323-330. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.1986.tb00466.x

- Tirumalae R, Yeliur IK, Antony M, et al. Papulonecrotic tuberculidclinicopathologic and molecular features of 12 Indian patients. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2014;4:17-22. doi:10.5826/dpc.0402a03

- Obiozor C, Ganguly S, Fraga GR. Leukemia cutis with lymphoglandular bodies: a clue to acute lymphoblastic leukemia cutis [published online August 15, 2015]. Dermatol Online J. 2015;21:13030/qt6m18g35f

- Vasudevan B, Chatterjee M. Lyme borreliosis and skin. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:167-174. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.110822

The Diagnosis: Ecthyma Gangrenosum

Histopathology revealed basophilic bacterial rods around necrotic vessels with thrombosis and edema (Figure). Blood and tissue cultures grew Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Based on the histopathology and clinical presentation, a diagnosis of P aeruginosa–associated ecthyma gangrenosum (EG) was made. The patient’s symptoms resolved with intravenous cefepime, and he later was transitioned to oral levofloxacin for outpatient treatment.

Ecthyma gangrenosum is an uncommon cutaneous manifestation of bacteremia that most commonly occurs secondary to P aeruginosa in immunocompromised patients, particularly patients with severe neutropenia in the setting of recent chemotherapy.1,2 Ecthyma gangrenosum can occur anywhere on the body, predominantly in moist areas such as the axillae and groin; the arms and legs, such as in our patient, as well as the trunk and face also may be involved.3 Other causes of EG skin lesions include methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, Citrobacter freundii, Escherichia coli, fungi such as Candida, and viruses such as herpes simplex virus.2,4-6 Common predisposing conditions associated with EG include neutropenia, leukemia, HIV, diabetes mellitus, extensive burn wounds, and a history of immunosuppressive medications. It also has been known to occur in otherwise healthy, immunocompetent individuals with no difference in clinical manifestation.2

The diagnosis is clinicopathologic, with initial evaluation including blood and wound cultures as well as a complete blood cell count once EG is suspected. An excisional or punch biopsy is performed for confirmation, showing many gram-negative, rod-shaped bacteria in cases of pseudomonal EG.7 Histopathology is characterized by bacterial perivascular invasion that then leads to secondary arteriole thrombosis, tissue edema, and separation of the epidermis.7,8 Resultant ischemic necrosis results in the classic macroscopic appearance of an erythematous macule that rapidly progresses into a central necrotic lesion surrounded by an erythematous or violaceous halo after undergoing a hemorrhagic bullous stage.1,9 A Wood lamp can be used to expedite the diagnosis, as Pseudomonas bacteria excretes a pigment (pyoverdine) that fluoresces yellowish green.10

Ecthyma gangrenosum can be classified as a primary skin lesion that may or may not be followed by bacteremia or as a lesion secondary to pseudomonal bacteremia.11 Bacteremia has been reported in half of cases, with hematogenous metastasis of the infection, likely in manifestations with multiple bilateral lesions.2 Our patient’s presentation of a single lesion revealed a positive blood culture result. Lesions also can develop by direct inoculation of the epidermis causing local destruction of the surrounding tissue. The nonbacteremic form of EG has been associated with a lower mortality rate of around 15% compared to patients with bacteremia ranging from 38% to 96%.12 The presence of neutropenia is the most important prognostic factor for mortality at the time of diagnosis.13

Prompt empiric therapy should be initiated after obtaining wound and blood cultures in those with infection until the causative organism and its susceptibility are identified. Pseudomonal infections account for 4% of all cases of hospital-acquired bacteremia and are the third leading cause of gram-negative bloodstream infection.7 Initial broad-spectrum antibiotics include antipseudomonal β-lactams (piperacillin-tazobactam), cephalosporins (cefepime), fluoroquinolones (levofloxacin), and carbapenems (imipenem).1,7 Medical therapy alone may be sufficient without requiring extensive surgical debridement to remove necrotic tissue in some patients. Surgical debridement usually is warranted for lesions larger than 10 cm in diameter.3 Our patient was treated with intravenous cefepime with resolution and was followed with outpatient oral levofloxacin as appropriate. A high index of suspicion should be maintained for relapsing pseudomonal EG infection among patients with AIDS, as the reported recurrence rate is 57%.14

Clinically, the differential diagnosis of EG presenting in immunocompromised patients or individuals with underlying malignancy includes pyoderma gangrenosum, papulonecrotic tuberculid, and leukemia cutis. An erythematous rash with central necrosis presenting in a patient with systemic symptoms is pathognomonic for erythema migrans and should be considered as a diagnostic possibility in areas endemic for Lyme disease in the United States, including the northeastern, mid-Atlantic, and north-central regions.15 A thorough history, physical examination, basic laboratory studies, and histopathology are critical to differentiate between these entities with similar macroscopic features. Pyoderma gangrenosum histologically manifests as a noninfectious, deep, suppurative folliculitis with leukocytoclastic vasculitis in 40% of cases.16 Although papulonecrotic tuberculid can present with dermal necrosis resulting from a hypersensitivity reaction to antigenic components of mycobacteria, there typically are granulomatous infiltrates present and a lack of observed organisms on histopathology.17 Although leukemia cutis infrequently occurs in patients diagnosed with leukemia, its salient features on pathology are nodular or diffuse infiltrates of leukemic cells in the dermis and subcutis with a high nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio, often with prominent nucleoli.18 Lyme disease can present in various ways; however, cutaneous involvement in the primary lesion is histologically characterized by a perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate containing plasma cells at the periphery of the expanding annular lesion and eosinophils present at the center.19

The Diagnosis: Ecthyma Gangrenosum

Histopathology revealed basophilic bacterial rods around necrotic vessels with thrombosis and edema (Figure). Blood and tissue cultures grew Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Based on the histopathology and clinical presentation, a diagnosis of P aeruginosa–associated ecthyma gangrenosum (EG) was made. The patient’s symptoms resolved with intravenous cefepime, and he later was transitioned to oral levofloxacin for outpatient treatment.

Ecthyma gangrenosum is an uncommon cutaneous manifestation of bacteremia that most commonly occurs secondary to P aeruginosa in immunocompromised patients, particularly patients with severe neutropenia in the setting of recent chemotherapy.1,2 Ecthyma gangrenosum can occur anywhere on the body, predominantly in moist areas such as the axillae and groin; the arms and legs, such as in our patient, as well as the trunk and face also may be involved.3 Other causes of EG skin lesions include methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, Citrobacter freundii, Escherichia coli, fungi such as Candida, and viruses such as herpes simplex virus.2,4-6 Common predisposing conditions associated with EG include neutropenia, leukemia, HIV, diabetes mellitus, extensive burn wounds, and a history of immunosuppressive medications. It also has been known to occur in otherwise healthy, immunocompetent individuals with no difference in clinical manifestation.2

The diagnosis is clinicopathologic, with initial evaluation including blood and wound cultures as well as a complete blood cell count once EG is suspected. An excisional or punch biopsy is performed for confirmation, showing many gram-negative, rod-shaped bacteria in cases of pseudomonal EG.7 Histopathology is characterized by bacterial perivascular invasion that then leads to secondary arteriole thrombosis, tissue edema, and separation of the epidermis.7,8 Resultant ischemic necrosis results in the classic macroscopic appearance of an erythematous macule that rapidly progresses into a central necrotic lesion surrounded by an erythematous or violaceous halo after undergoing a hemorrhagic bullous stage.1,9 A Wood lamp can be used to expedite the diagnosis, as Pseudomonas bacteria excretes a pigment (pyoverdine) that fluoresces yellowish green.10

Ecthyma gangrenosum can be classified as a primary skin lesion that may or may not be followed by bacteremia or as a lesion secondary to pseudomonal bacteremia.11 Bacteremia has been reported in half of cases, with hematogenous metastasis of the infection, likely in manifestations with multiple bilateral lesions.2 Our patient’s presentation of a single lesion revealed a positive blood culture result. Lesions also can develop by direct inoculation of the epidermis causing local destruction of the surrounding tissue. The nonbacteremic form of EG has been associated with a lower mortality rate of around 15% compared to patients with bacteremia ranging from 38% to 96%.12 The presence of neutropenia is the most important prognostic factor for mortality at the time of diagnosis.13

Prompt empiric therapy should be initiated after obtaining wound and blood cultures in those with infection until the causative organism and its susceptibility are identified. Pseudomonal infections account for 4% of all cases of hospital-acquired bacteremia and are the third leading cause of gram-negative bloodstream infection.7 Initial broad-spectrum antibiotics include antipseudomonal β-lactams (piperacillin-tazobactam), cephalosporins (cefepime), fluoroquinolones (levofloxacin), and carbapenems (imipenem).1,7 Medical therapy alone may be sufficient without requiring extensive surgical debridement to remove necrotic tissue in some patients. Surgical debridement usually is warranted for lesions larger than 10 cm in diameter.3 Our patient was treated with intravenous cefepime with resolution and was followed with outpatient oral levofloxacin as appropriate. A high index of suspicion should be maintained for relapsing pseudomonal EG infection among patients with AIDS, as the reported recurrence rate is 57%.14

Clinically, the differential diagnosis of EG presenting in immunocompromised patients or individuals with underlying malignancy includes pyoderma gangrenosum, papulonecrotic tuberculid, and leukemia cutis. An erythematous rash with central necrosis presenting in a patient with systemic symptoms is pathognomonic for erythema migrans and should be considered as a diagnostic possibility in areas endemic for Lyme disease in the United States, including the northeastern, mid-Atlantic, and north-central regions.15 A thorough history, physical examination, basic laboratory studies, and histopathology are critical to differentiate between these entities with similar macroscopic features. Pyoderma gangrenosum histologically manifests as a noninfectious, deep, suppurative folliculitis with leukocytoclastic vasculitis in 40% of cases.16 Although papulonecrotic tuberculid can present with dermal necrosis resulting from a hypersensitivity reaction to antigenic components of mycobacteria, there typically are granulomatous infiltrates present and a lack of observed organisms on histopathology.17 Although leukemia cutis infrequently occurs in patients diagnosed with leukemia, its salient features on pathology are nodular or diffuse infiltrates of leukemic cells in the dermis and subcutis with a high nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio, often with prominent nucleoli.18 Lyme disease can present in various ways; however, cutaneous involvement in the primary lesion is histologically characterized by a perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate containing plasma cells at the periphery of the expanding annular lesion and eosinophils present at the center.19

- Abdou A, Hassam B. Ecthyma gangrenosum [in French]. Pan Afr Med J. 2018;30:95. doi:10.11604/pamj.2018.30.95.6244

- Vaiman M, Lazarovitch T, Heller L, et al. Ecthyma gangrenosum and ecthyma-like lesions: review article. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2015;34:633-639. doi:10.1007/s10096-014-2277-6

- Vaiman M, Lasarovitch T, Heller L, et al. Ecthyma gangrenosum versus ecthyma-like lesions: should we separate these conditions? Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2015;24:69-72. doi:10.15570 /actaapa.2015.18

- Reich HL, Williams Fadeyi D, Naik NS, et al. Nonpseudomonal ecthyma gangrenosum. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50(5 suppl): S114-S117. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2003.09.019

- Hawkley T, Chang D, Pollard W, et al. Ecthyma gangrenosum caused by Citrobacter freundii [published online July 27, 2017]. BMJ Case Rep. doi:10.1136/bcr-2017-220996

- Santhaseelan RG, Muralidhar V. Non-pseudomonal ecthyma gangrenosum caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in a chronic alcoholic patient [published online August 3, 2017]. BMJ Case Rep. doi:10.1136/bcr-2017-220983m

- Bassetti M, Vena A, Croxatto A, et al. How to manage Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections [published online May 29, 2018]. Drugs Context. 2018;7:212527. doi:10.7573/dic.212527

- Llamas-Velasco M, Alegría V, Santos-Briz Á, et al. Occlusive nonvasculitic vasculopathy. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:637-662. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000000766

- Sarkar S, Patra AK, Mondal M. Ecthyma gangrenosum in the periorbital region in a previously healthy immunocompetent woman without bacteremia. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2016;7:36-39. doi:10.4103/2229-5178.174326

- Ponka D, Baddar F. Wood lamp examination. Can Fam Physician. 2012;58:976.

- Van den Broek PJ, Van der Meer JWM, Kunst MW. The pathogenesis of ecthyma gangrenosum. J Infect. 1979;1:263-267. doi:10.1016 /S0163-4453(79)91329-X

- Downey DM, O’Bryan MC, Burdette SD, et al. Ecthyma gangrenosum in a patient with toxic epidermal necrolysis. J Burn Care Res. 2007;28:198-202. doi:10.1097/BCR.0B013E31802CA481

- Martínez-Longoria CA, Rosales-Solis GM, Ocampo-Garza J, et al. Ecthyma gangrenosum: a report of eight cases. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92:698-700. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20175580

- Khan MO, Montecalvo MA, Davis I, et al. Ecthyma gangrenosum in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Cutis. 2000;66:121-123.

- Nadelman RB, Wormser GP. Lyme borreliosis. Lancet. 1998; 352:557-565.

- Su WP, Schroeter AL, Perry HO, et al. Histopathologic and immunopathologic study of pyoderma gangrenosum. J Cutan Pathol. 1986;13:323-330. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.1986.tb00466.x

- Tirumalae R, Yeliur IK, Antony M, et al. Papulonecrotic tuberculidclinicopathologic and molecular features of 12 Indian patients. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2014;4:17-22. doi:10.5826/dpc.0402a03

- Obiozor C, Ganguly S, Fraga GR. Leukemia cutis with lymphoglandular bodies: a clue to acute lymphoblastic leukemia cutis [published online August 15, 2015]. Dermatol Online J. 2015;21:13030/qt6m18g35f

- Vasudevan B, Chatterjee M. Lyme borreliosis and skin. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:167-174. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.110822

- Abdou A, Hassam B. Ecthyma gangrenosum [in French]. Pan Afr Med J. 2018;30:95. doi:10.11604/pamj.2018.30.95.6244

- Vaiman M, Lazarovitch T, Heller L, et al. Ecthyma gangrenosum and ecthyma-like lesions: review article. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2015;34:633-639. doi:10.1007/s10096-014-2277-6

- Vaiman M, Lasarovitch T, Heller L, et al. Ecthyma gangrenosum versus ecthyma-like lesions: should we separate these conditions? Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2015;24:69-72. doi:10.15570 /actaapa.2015.18

- Reich HL, Williams Fadeyi D, Naik NS, et al. Nonpseudomonal ecthyma gangrenosum. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50(5 suppl): S114-S117. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2003.09.019

- Hawkley T, Chang D, Pollard W, et al. Ecthyma gangrenosum caused by Citrobacter freundii [published online July 27, 2017]. BMJ Case Rep. doi:10.1136/bcr-2017-220996

- Santhaseelan RG, Muralidhar V. Non-pseudomonal ecthyma gangrenosum caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in a chronic alcoholic patient [published online August 3, 2017]. BMJ Case Rep. doi:10.1136/bcr-2017-220983m

- Bassetti M, Vena A, Croxatto A, et al. How to manage Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections [published online May 29, 2018]. Drugs Context. 2018;7:212527. doi:10.7573/dic.212527

- Llamas-Velasco M, Alegría V, Santos-Briz Á, et al. Occlusive nonvasculitic vasculopathy. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:637-662. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000000766

- Sarkar S, Patra AK, Mondal M. Ecthyma gangrenosum in the periorbital region in a previously healthy immunocompetent woman without bacteremia. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2016;7:36-39. doi:10.4103/2229-5178.174326

- Ponka D, Baddar F. Wood lamp examination. Can Fam Physician. 2012;58:976.

- Van den Broek PJ, Van der Meer JWM, Kunst MW. The pathogenesis of ecthyma gangrenosum. J Infect. 1979;1:263-267. doi:10.1016 /S0163-4453(79)91329-X

- Downey DM, O’Bryan MC, Burdette SD, et al. Ecthyma gangrenosum in a patient with toxic epidermal necrolysis. J Burn Care Res. 2007;28:198-202. doi:10.1097/BCR.0B013E31802CA481

- Martínez-Longoria CA, Rosales-Solis GM, Ocampo-Garza J, et al. Ecthyma gangrenosum: a report of eight cases. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92:698-700. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20175580

- Khan MO, Montecalvo MA, Davis I, et al. Ecthyma gangrenosum in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Cutis. 2000;66:121-123.

- Nadelman RB, Wormser GP. Lyme borreliosis. Lancet. 1998; 352:557-565.

- Su WP, Schroeter AL, Perry HO, et al. Histopathologic and immunopathologic study of pyoderma gangrenosum. J Cutan Pathol. 1986;13:323-330. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.1986.tb00466.x

- Tirumalae R, Yeliur IK, Antony M, et al. Papulonecrotic tuberculidclinicopathologic and molecular features of 12 Indian patients. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2014;4:17-22. doi:10.5826/dpc.0402a03

- Obiozor C, Ganguly S, Fraga GR. Leukemia cutis with lymphoglandular bodies: a clue to acute lymphoblastic leukemia cutis [published online August 15, 2015]. Dermatol Online J. 2015;21:13030/qt6m18g35f

- Vasudevan B, Chatterjee M. Lyme borreliosis and skin. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:167-174. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.110822

A 58-year-old man who was receiving gilteritinib therapy for relapsed acute myeloid leukemia presented to the emergency department with a painful, rapidly enlarging lesion on the right medial thigh of 2 days’ duration that was accompanied by fever (temperature, 39.2 °C) and body aches. Physical examination revealed a tender annular plaque with a dark violaceous halo overlying a larger area of erythema and induration. Laboratory evaluation revealed a white blood cell count of 600/μL (reference range, 4500–11,000/μL) and an absolute neutrophil count of 200/μL (reference range, 1800–7000/μL). A biopsy was performed.

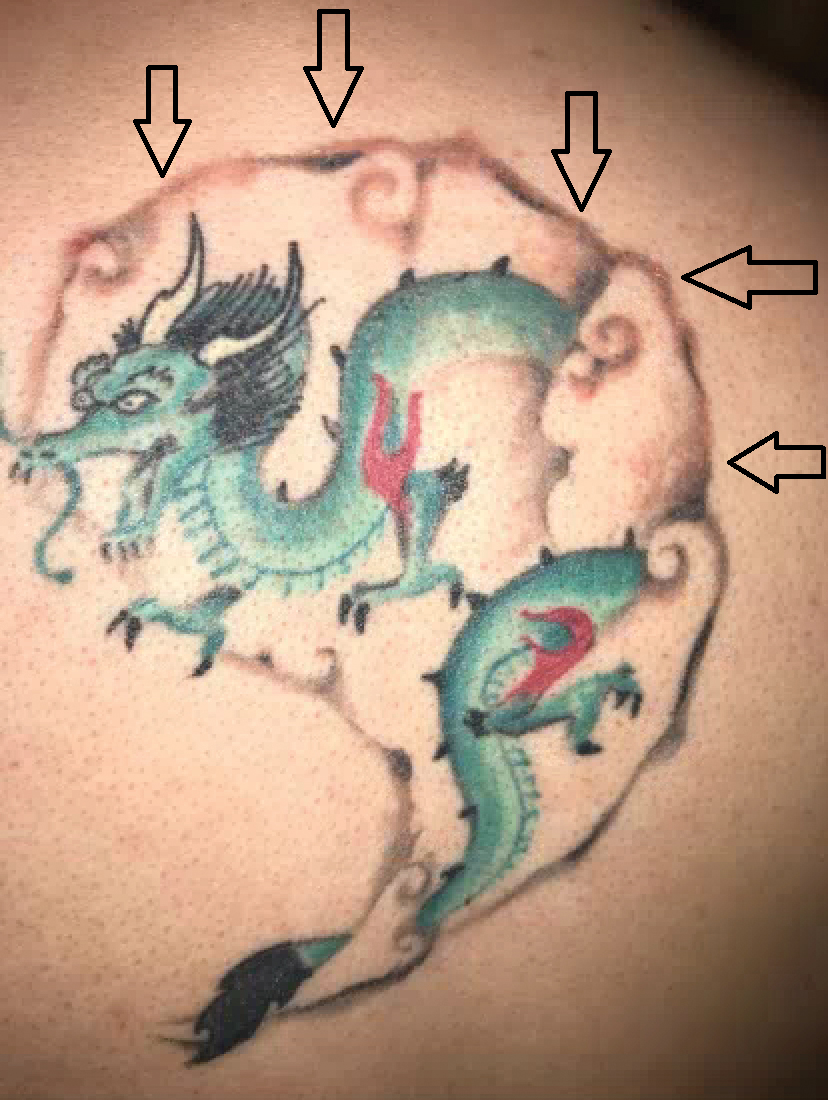

Erythematous Plaques on a Tattoo

The Diagnosis: Epidermodysplasia Verruciformis

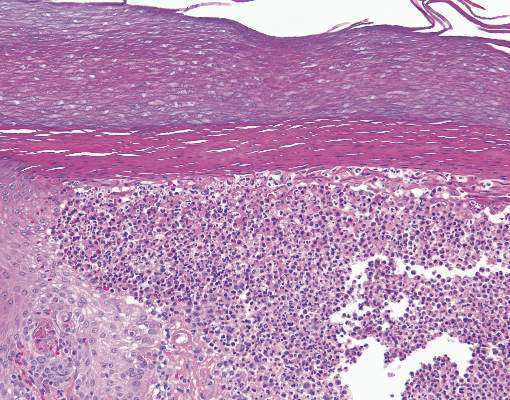

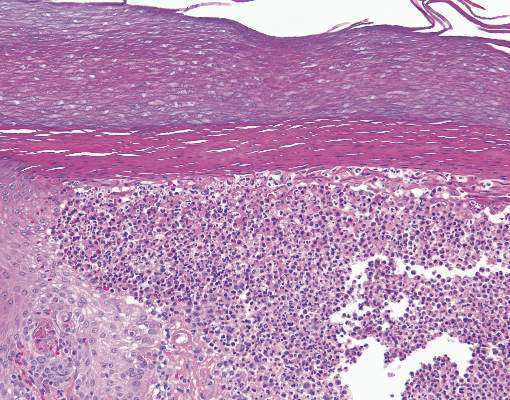

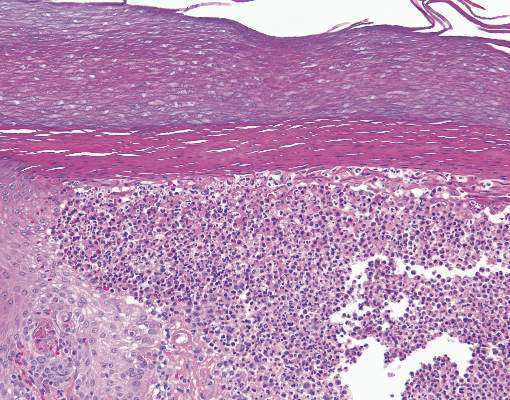

Histopathologic examination demonstrated acanthosis and coarse hypergranulosis with enlarged keratinocytes exhibiting blue cytoplasmic discoloration (Figure), which was suggestive of acquired epidermodysplasia verruciformis (EV).

Acquired EV is a rare dermatologic condition associated with specific human papillomavirus (HPV) types that presents with recalcitrant lesions most commonly in the setting of immunosuppression.1 The most common HPV types associated with EV are HPV-5 and -8, but associations with HPV-3, -9, -10, -12, -14, -15, -17, -19 to -25, -36 to -38, -47, and -50 also have been reported.1,2 Acquired EV has been identified in individuals with human immunodeficiency virus, as well as in immunosuppressed patients with organ transplantation, Hodgkin lymphoma, systemic lupus erythematosus, and IgM deficiency, and in patients taking immunosuppressive medications such as tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors.1,3 The diagnosis is clinicopathological with potential polymerase chain reaction studies to identify underlying HPV types.

Acquired EV presents as hypopigmented to red, tinea versicolor-like macules or as verrucous, flat-topped papules on the trunk, arms, and/or legs.4 Histopathology reveals viral epidermal cytopathic changes, blue cytoplasm, and coarse hypogranulosis.4

There is no standardized treatment regimen for acquired EV, and no single approach has proven to yield an efficacious clinical outcome. Topical treatment options include steroids, retinoids, immunomodulators, cryotherapy, and electrosurgery, whereas retinoids or interferon alfa have been used as oral systemic therapy. Photodynamic therapy also has been shown to improve symptoms.3 Combination therapy such as interferon alfa with zidovudine or imiquimod with oral isotretinoin has shown better results than any single treatment.4 Due to the underlying HPV infection and its role in promotion of skin cancer development, lesions can characteristically undergo malignant transformations into Bowen disease but most commonly invasive squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), with initial lesions preferentially affecting sun-exposed areas due to the synergistic effect of UV light with EV-HPV lesions. The EV-HPV strains 5, 8, and 41 carry the highest oncogenic potential.5 Little is known of the true incidence of oncogenicity for acquired EV. Regardless, consistent sun protection and lifelong clinical examinations are critical for prognosis.5

The differential diagnosis of EV presenting in a tattoo includes allergic contact dermatitis, cutaneous sarcoidosis, pityriasis versicolor, and SCC. The pathology is critical to differentiate between these entities. The most frequently reported skin reactions to tattoo ink include inflammatory diseases (eg, allergic contact dermatitis, granulomatous reaction) or infectious diseases (eg, bacterial, viral, fungal).6 Allergic contact dermatitis, typically red pigment, is a common tattoo reaction. The most common histologic feature, however, is spongiosis, which results from intercellular edema. It often is limited to the lower epidermis but may affect the upper layers if the reaction is severe.7 Cutaneous sarcoidosis is a great masquerader that can present in various ways; however, its salient features on pathology are noncaseating granuloma involving the basal cell layer and epithelioid granuloma consisting of Langerhans giant cells.8 Although pityriasis versicolor can present in young immunocompromised adults, histologically salient features are the presence of both spores and hyphae in the stratum corneum.9 Although immunosuppression is a known risk factor for SCC, it is characterized histologically by hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis, and acanthosis with thickened and elongated rete ridges. Scattered atypical cells and frequent mitoses are present.10

- Schultz B, Nguyen CV, Jacobson-Dunlop E. Acquired epidermodysplasia verruciformis in setting of tumor necrosis factor-α inhibitor therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol Case Rep. 2018;4:805-807.

- DeVilliers EM, Fauquet C, Brocker TR, et al. Classification of papillomaviruses. Virology. 2004;324:17-27.

- Zampetti A, Giurdanella F, Manco S, et al. Acquired epidermodysplasia verruciformis: a comprehensive review and a proposal for treatment. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:974-980.

- Henley JK, Hossler EW. Acquired epidermodysplasia verruciformis occurring in a renal transplant recipient. Cutis. 2017;99:E9-E12.

- Berk DR, Bruckner AL, Lu D. Epidermodysplasia verruciform-like lesions in an HIV patient. Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:1.

- Napolitano M, Megna M, Cappello M, et al. Skin diseases and tattoos: a five-year experience. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2018;153:644-648.

- Nixon RL, Mowad CM, Marks JG Jr. Allergic contact dermatitis. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2018:242-259.

- Ferringer T. Granulomatous and histiocytic diseases. In: Elston DM, Ferringer T, Ko C, et al, eds. Dermatopathology. 3rd ed. China: Elsevier; 2019:175-176.

- Elewski BE, Hughey LC, Hunt KM, et al. Fungal diseases. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2018:1329-1346.

- Soyer HP, Rigel DS, McMeniman E. Actinic keratosis, basal cell carcinoma, and squamous cell carcinoma. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2018:1887-1884.

The Diagnosis: Epidermodysplasia Verruciformis

Histopathologic examination demonstrated acanthosis and coarse hypergranulosis with enlarged keratinocytes exhibiting blue cytoplasmic discoloration (Figure), which was suggestive of acquired epidermodysplasia verruciformis (EV).

Acquired EV is a rare dermatologic condition associated with specific human papillomavirus (HPV) types that presents with recalcitrant lesions most commonly in the setting of immunosuppression.1 The most common HPV types associated with EV are HPV-5 and -8, but associations with HPV-3, -9, -10, -12, -14, -15, -17, -19 to -25, -36 to -38, -47, and -50 also have been reported.1,2 Acquired EV has been identified in individuals with human immunodeficiency virus, as well as in immunosuppressed patients with organ transplantation, Hodgkin lymphoma, systemic lupus erythematosus, and IgM deficiency, and in patients taking immunosuppressive medications such as tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors.1,3 The diagnosis is clinicopathological with potential polymerase chain reaction studies to identify underlying HPV types.

Acquired EV presents as hypopigmented to red, tinea versicolor-like macules or as verrucous, flat-topped papules on the trunk, arms, and/or legs.4 Histopathology reveals viral epidermal cytopathic changes, blue cytoplasm, and coarse hypogranulosis.4

There is no standardized treatment regimen for acquired EV, and no single approach has proven to yield an efficacious clinical outcome. Topical treatment options include steroids, retinoids, immunomodulators, cryotherapy, and electrosurgery, whereas retinoids or interferon alfa have been used as oral systemic therapy. Photodynamic therapy also has been shown to improve symptoms.3 Combination therapy such as interferon alfa with zidovudine or imiquimod with oral isotretinoin has shown better results than any single treatment.4 Due to the underlying HPV infection and its role in promotion of skin cancer development, lesions can characteristically undergo malignant transformations into Bowen disease but most commonly invasive squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), with initial lesions preferentially affecting sun-exposed areas due to the synergistic effect of UV light with EV-HPV lesions. The EV-HPV strains 5, 8, and 41 carry the highest oncogenic potential.5 Little is known of the true incidence of oncogenicity for acquired EV. Regardless, consistent sun protection and lifelong clinical examinations are critical for prognosis.5

The differential diagnosis of EV presenting in a tattoo includes allergic contact dermatitis, cutaneous sarcoidosis, pityriasis versicolor, and SCC. The pathology is critical to differentiate between these entities. The most frequently reported skin reactions to tattoo ink include inflammatory diseases (eg, allergic contact dermatitis, granulomatous reaction) or infectious diseases (eg, bacterial, viral, fungal).6 Allergic contact dermatitis, typically red pigment, is a common tattoo reaction. The most common histologic feature, however, is spongiosis, which results from intercellular edema. It often is limited to the lower epidermis but may affect the upper layers if the reaction is severe.7 Cutaneous sarcoidosis is a great masquerader that can present in various ways; however, its salient features on pathology are noncaseating granuloma involving the basal cell layer and epithelioid granuloma consisting of Langerhans giant cells.8 Although pityriasis versicolor can present in young immunocompromised adults, histologically salient features are the presence of both spores and hyphae in the stratum corneum.9 Although immunosuppression is a known risk factor for SCC, it is characterized histologically by hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis, and acanthosis with thickened and elongated rete ridges. Scattered atypical cells and frequent mitoses are present.10

The Diagnosis: Epidermodysplasia Verruciformis

Histopathologic examination demonstrated acanthosis and coarse hypergranulosis with enlarged keratinocytes exhibiting blue cytoplasmic discoloration (Figure), which was suggestive of acquired epidermodysplasia verruciformis (EV).

Acquired EV is a rare dermatologic condition associated with specific human papillomavirus (HPV) types that presents with recalcitrant lesions most commonly in the setting of immunosuppression.1 The most common HPV types associated with EV are HPV-5 and -8, but associations with HPV-3, -9, -10, -12, -14, -15, -17, -19 to -25, -36 to -38, -47, and -50 also have been reported.1,2 Acquired EV has been identified in individuals with human immunodeficiency virus, as well as in immunosuppressed patients with organ transplantation, Hodgkin lymphoma, systemic lupus erythematosus, and IgM deficiency, and in patients taking immunosuppressive medications such as tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors.1,3 The diagnosis is clinicopathological with potential polymerase chain reaction studies to identify underlying HPV types.

Acquired EV presents as hypopigmented to red, tinea versicolor-like macules or as verrucous, flat-topped papules on the trunk, arms, and/or legs.4 Histopathology reveals viral epidermal cytopathic changes, blue cytoplasm, and coarse hypogranulosis.4

There is no standardized treatment regimen for acquired EV, and no single approach has proven to yield an efficacious clinical outcome. Topical treatment options include steroids, retinoids, immunomodulators, cryotherapy, and electrosurgery, whereas retinoids or interferon alfa have been used as oral systemic therapy. Photodynamic therapy also has been shown to improve symptoms.3 Combination therapy such as interferon alfa with zidovudine or imiquimod with oral isotretinoin has shown better results than any single treatment.4 Due to the underlying HPV infection and its role in promotion of skin cancer development, lesions can characteristically undergo malignant transformations into Bowen disease but most commonly invasive squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), with initial lesions preferentially affecting sun-exposed areas due to the synergistic effect of UV light with EV-HPV lesions. The EV-HPV strains 5, 8, and 41 carry the highest oncogenic potential.5 Little is known of the true incidence of oncogenicity for acquired EV. Regardless, consistent sun protection and lifelong clinical examinations are critical for prognosis.5

The differential diagnosis of EV presenting in a tattoo includes allergic contact dermatitis, cutaneous sarcoidosis, pityriasis versicolor, and SCC. The pathology is critical to differentiate between these entities. The most frequently reported skin reactions to tattoo ink include inflammatory diseases (eg, allergic contact dermatitis, granulomatous reaction) or infectious diseases (eg, bacterial, viral, fungal).6 Allergic contact dermatitis, typically red pigment, is a common tattoo reaction. The most common histologic feature, however, is spongiosis, which results from intercellular edema. It often is limited to the lower epidermis but may affect the upper layers if the reaction is severe.7 Cutaneous sarcoidosis is a great masquerader that can present in various ways; however, its salient features on pathology are noncaseating granuloma involving the basal cell layer and epithelioid granuloma consisting of Langerhans giant cells.8 Although pityriasis versicolor can present in young immunocompromised adults, histologically salient features are the presence of both spores and hyphae in the stratum corneum.9 Although immunosuppression is a known risk factor for SCC, it is characterized histologically by hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis, and acanthosis with thickened and elongated rete ridges. Scattered atypical cells and frequent mitoses are present.10

- Schultz B, Nguyen CV, Jacobson-Dunlop E. Acquired epidermodysplasia verruciformis in setting of tumor necrosis factor-α inhibitor therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol Case Rep. 2018;4:805-807.

- DeVilliers EM, Fauquet C, Brocker TR, et al. Classification of papillomaviruses. Virology. 2004;324:17-27.

- Zampetti A, Giurdanella F, Manco S, et al. Acquired epidermodysplasia verruciformis: a comprehensive review and a proposal for treatment. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:974-980.

- Henley JK, Hossler EW. Acquired epidermodysplasia verruciformis occurring in a renal transplant recipient. Cutis. 2017;99:E9-E12.

- Berk DR, Bruckner AL, Lu D. Epidermodysplasia verruciform-like lesions in an HIV patient. Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:1.

- Napolitano M, Megna M, Cappello M, et al. Skin diseases and tattoos: a five-year experience. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2018;153:644-648.

- Nixon RL, Mowad CM, Marks JG Jr. Allergic contact dermatitis. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2018:242-259.

- Ferringer T. Granulomatous and histiocytic diseases. In: Elston DM, Ferringer T, Ko C, et al, eds. Dermatopathology. 3rd ed. China: Elsevier; 2019:175-176.

- Elewski BE, Hughey LC, Hunt KM, et al. Fungal diseases. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2018:1329-1346.

- Soyer HP, Rigel DS, McMeniman E. Actinic keratosis, basal cell carcinoma, and squamous cell carcinoma. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2018:1887-1884.

- Schultz B, Nguyen CV, Jacobson-Dunlop E. Acquired epidermodysplasia verruciformis in setting of tumor necrosis factor-α inhibitor therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol Case Rep. 2018;4:805-807.

- DeVilliers EM, Fauquet C, Brocker TR, et al. Classification of papillomaviruses. Virology. 2004;324:17-27.

- Zampetti A, Giurdanella F, Manco S, et al. Acquired epidermodysplasia verruciformis: a comprehensive review and a proposal for treatment. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:974-980.

- Henley JK, Hossler EW. Acquired epidermodysplasia verruciformis occurring in a renal transplant recipient. Cutis. 2017;99:E9-E12.

- Berk DR, Bruckner AL, Lu D. Epidermodysplasia verruciform-like lesions in an HIV patient. Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:1.

- Napolitano M, Megna M, Cappello M, et al. Skin diseases and tattoos: a five-year experience. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2018;153:644-648.

- Nixon RL, Mowad CM, Marks JG Jr. Allergic contact dermatitis. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2018:242-259.

- Ferringer T. Granulomatous and histiocytic diseases. In: Elston DM, Ferringer T, Ko C, et al, eds. Dermatopathology. 3rd ed. China: Elsevier; 2019:175-176.

- Elewski BE, Hughey LC, Hunt KM, et al. Fungal diseases. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2018:1329-1346.

- Soyer HP, Rigel DS, McMeniman E. Actinic keratosis, basal cell carcinoma, and squamous cell carcinoma. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2018:1887-1884.

A 29-year-old man presented with increased redness, dryness, and pruritus at the periphery of a tattoo (arrows) on the upper back of 4 months' duration. He was diagnosed with human immunodeficiency virus 8 months prior to presentation and had a history of cystic fibrosis, eczema, and genital molluscum contagiosum. Laboratory analysis 1 month prior revealed a CD4 count of 42 cells/mm3 (reference range, 500-1200 cells/mm3), and the viral load was 2388 copies/mL (reference range, 20-10,000,000 copies/mL). Physical examination revealed multiple erythematous, eczematous, linear plaques along the dark gray lines of the tattoo. A 1.1.2 ×0.7.2 ×0.1-cm shave biopsy specimen was obtained. After the biopsy, tretinoin cream 0.1% and betamethasone dipropionate ointment 0.05% were prescribed to be alternately applied on the tattoo lesions until resolution.

Cutaneous Metastases From Esophageal Adenocarcinoma on the Scalp

To the Editor:

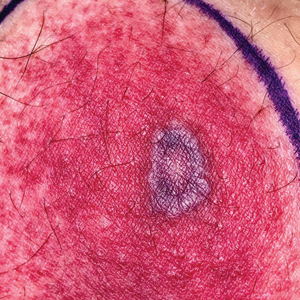

A 59-year-old man presented with a lesion on the right frontal scalp of 4 months’ duration and a lesion on the left frontal scalp of 1 month’s duration. Both lesions were tender, bleeding, nonhealing, and growing in size. The patient reported no improvement with the use of triple antibiotic ointment. He denied any associated symptoms or trauma to the affected areas. He had a history of stage IV esophageal adenocarcinoma that initially had been surgically removed 6 years prior but metastasized to the lungs and bone. The patient subsequently underwent treatment with FOLFOX (folinic acid, fluorouracil, oxaliplatin), trastuzumab, and radiation therapy.

Physical examination revealed a hyperkeratotic pink nodule with a central erosion and crust on the right frontal scalp measuring 1.5×2 cm in diameter (Figure 1A). The left frontal scalp lesion was a smooth pearly papule measuring 5×5 mm in diameter (Figure 1B). The differential diagnosis included basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and cutaneous metastases from esophageal adenocarcinoma. Shave biopsies were taken of both scalp lesions.

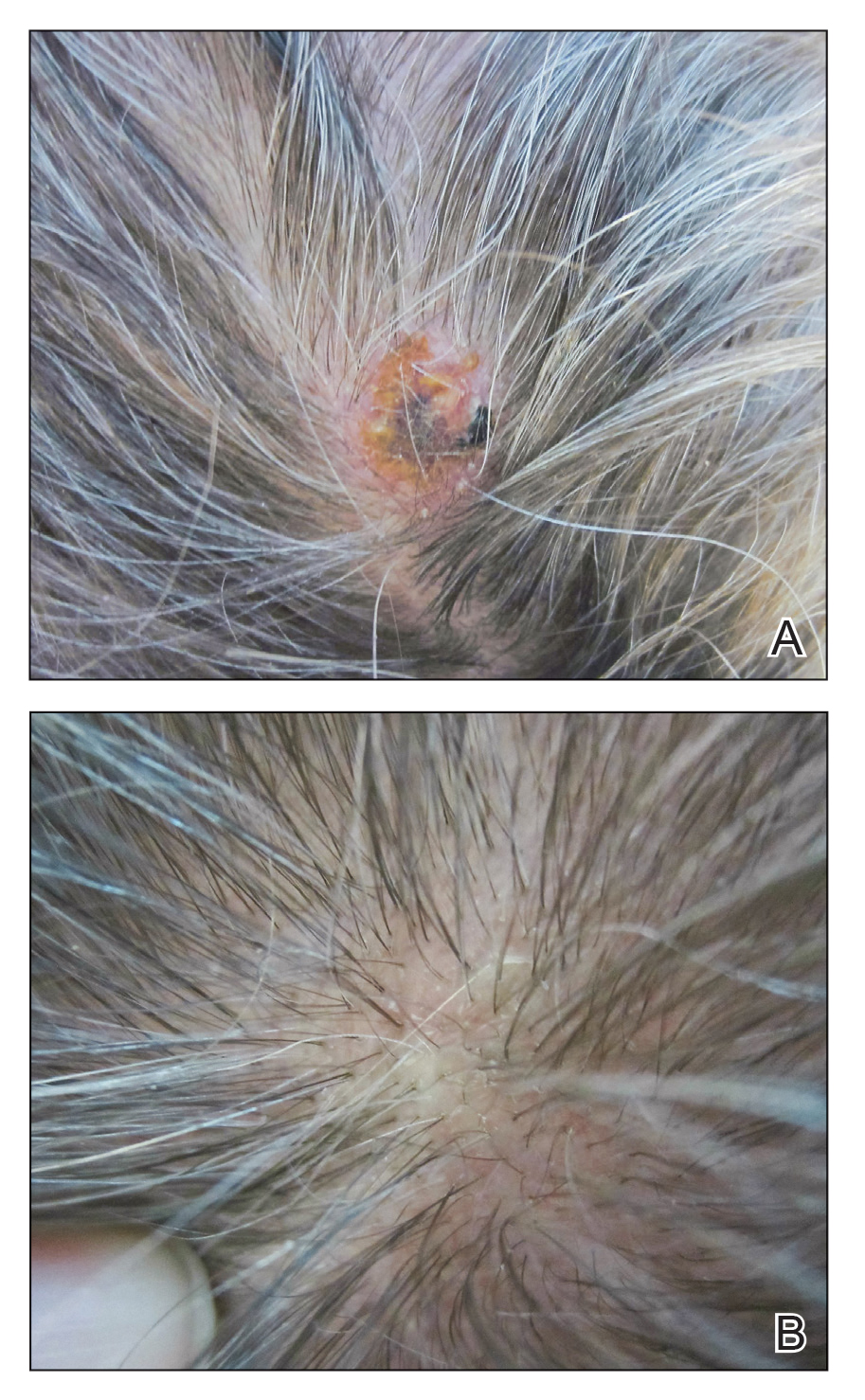

Histologic examination of both scalp lesions demonstrated a dermal gland-forming neoplasm with an infiltrative distribution that was comprised of irregular cribriform glands containing cellular debris (Figure 2). The cells of interest were enlarged and contained pleomorphic crowded nuclei that formed aberrant mitotic division figures. Both biopsies were positive for cytokeratin 7 and negative for cytokeratin 20 and CDX2. The final diagnosis for both scalp lesions was poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma, which was most suggestive of cutaneous metastases of the patient’s known esophageal adenocarcinoma. Given further metastasis, the patient was ultimately switched to ramucirumab and paclitaxel per oncology.

Esophageal carcinoma is the eighth most common cause of death related to cancer worldwide. Adenocarcinoma is the most prevalent histologic type of esophageal carcinoma, with an incidence as high as 5.69 per 100,000 individuals in the United States.1 Internal malignancies that lead to cutaneous metastases are not uncommon; however, the literature is limited on cutaneous scalp metastases from esophageal cancer. Cutaneous metastases secondary to internal malignancies present in less than 10% of overall cases; tend to derive from the breasts, lungs, and large bowel; and usually present in the sixth to seventh decades of life.2 Further, roughly 1% of all skin metastases originate from the esophagus.3 When there are cutaneous metastases to the scalp, they often arise from breast carcinomas and renal cell carcinomas.4,5 Rarely does esophageal cancer spread to the scalp.2,6-9 When cutaneous metastases originate from the esophagus, multiple cancers such as squamous cell carcinomas, mucoepidermoid carcinomas, small cell carcinomas, and adenocarcinomas can be the etiology of origin.10 Metastases originating from esophageal carcinomas frequently are diagnosed in the abdominal lymph nodes (45%), liver (35%), lungs (20%), cervical/supraclavicular lymph nodes (18%), bones (9%), adrenals (5%), peritoneum (2%), brain (2%), stomach (1%), pancreas (1%), pleura (1%), skin/body wall (1%), pericardium (1%), and spleen (1%).3 Additionally, multiple cutaneous scalp metastases from esophageal adenocarcinoma have been reported,7,9 as were seen in our case.

The clinical appearance of cutaneous scalp metastases has been described as inflammatory papules, indurated plaques, or nodules,2 which is consistent with our case, though the spectrum of presentation is admittedly broad. Histopathology of lesions characteristically shows prominent intraluminal necrotic cellular debris, which is common for adenocarcinomas of the gastrointestinal tract.7 However, utilizing immunohistochemical stains to detect specific antigens within tumor cells allows for better specificity of the tumor origin. More specifically, cytokeratin 7 and cytokeratin 20 are stained in esophageal metaplasia, such as Barrett esophagus, rather than in intestinal metaplasia inside the stomach.2,11 Therefore, discerning the location of the adenocarcinoma proves fruitful when using cytokeratin 7 and cytokeratin 20. Although CDX2 is an additional marker that can be used for gastrointestinal adenocarcinomas with decent sensitivity and specificity, it can still be expressed in mucinous ovarian carcinomas and urinary bladder adenocarcinomas.12 In our patient, the strong reactivity of cytokeratin 7 in addition to the characteristic morphology in both presenting biopsies was sufficient to make the diagnosis of cutaneous metastasis of esophageal adenocarcinoma to the scalp.

Our case highlights multiple cutaneous metastases of the scalp from a primary esophageal adenocarcinoma. Although cutaneous scalp metastasis of esophageal adenocarcinoma is rare, it is essential to provide a full-body skin examination, including the scalp, in patients with a history of esophageal cancer and to biopsy any suspicious nodules or plaques. The 1-year survival rate after diagnosis of esophageal carcinoma is less than 50%, and the 5-year survival rate is less than 10%.13 Identifying cutaneous metastasis of an esophageal adenocarcinoma can either change the staging of the cancer (if it was the first distant metastasis noted) or indicate an insufficient response to treatment in a patient with known metastatic disease, prompting a potential change in treatment.7

This case illustrates a rare site of metastasis of a fairly common cancer and highlights the histopathology and accompanying immunohistochemical stains that can be useful in diagnosis as well as the spectrum of its clinical presentation.

- Melhado R, Alderson D, Tucker O. The changing face of esophageal cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2010;2:1379-1404.

- Park JM, Kim DS, Oh SH, et al. A case of esophageal adenocarcinoma metastasized to the scalp [published online May 31, 2009]. Ann Dermatol. 2009;21:164-167.

- Quint LE, Hepburn LM, Francis IR, et al. Incidence and distribution of distant metastases from newly diagnosed esophageal carcinoma. Cancer. 1995;76:1120.

- Dobson C, Tagor V, Myint A, et al. Telangiectatic metastatic breast carcinoma in face and scalp mimicking cutaneous angiosarcoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:635-636.

- Riter H, Ghobrial I. Renal cell carcinoma with acrometastasis and scalp metastasis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2004;79:76.

- Roh EK, Nord R, Jukic DM. Scalp metastasis from esophageal adenocarcinoma. Cutis. 2006;77:106.

- Doumit G, Abouhassan W, Piliang M, et al. Scalp metastasis from esophageal adenocarcinoma: comparative histopathology dictates surgical approach. Ann Plast Surg. 2011;71:60-62.

- Roy AD, Sherparpa M, Prasad PR, et al. Scalp metastasis of gastro-esophageal junction adenocarcinoma: a rare occurrence. 2014;8:159-160.

- Stein R, Spencer J. Painful cutaneous metastases from esophageal carcinoma. Cutis. 2002;70:230.

- Schwartz RA. Cutaneous metastatic disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33(2 pt 1):161-182.

- Ormsby AH, Goldblum JR, Rice TW, et al. Cytokeratin subsets can reliably distinguish Barrett’s esophagus from intestinal metaplasia of the stomach. Hum Pathol. 1999;30:288-294.

- Werling RW, Yaziji H, Bacchi CE, et al. CDX2, a highly sensitive and specific marker of adenocarcinomas of intestinal origin: an immunohistochemical survey of 476 primary and metastatic carcinomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:303-310.

- Smith KJ, Williams J, Skelton H. Metastatic adenocarcinoma of the esophagus to the skin: new patterns of tumor recurrence and alternate treatments for palliation. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:425-431.

To the Editor:

A 59-year-old man presented with a lesion on the right frontal scalp of 4 months’ duration and a lesion on the left frontal scalp of 1 month’s duration. Both lesions were tender, bleeding, nonhealing, and growing in size. The patient reported no improvement with the use of triple antibiotic ointment. He denied any associated symptoms or trauma to the affected areas. He had a history of stage IV esophageal adenocarcinoma that initially had been surgically removed 6 years prior but metastasized to the lungs and bone. The patient subsequently underwent treatment with FOLFOX (folinic acid, fluorouracil, oxaliplatin), trastuzumab, and radiation therapy.

Physical examination revealed a hyperkeratotic pink nodule with a central erosion and crust on the right frontal scalp measuring 1.5×2 cm in diameter (Figure 1A). The left frontal scalp lesion was a smooth pearly papule measuring 5×5 mm in diameter (Figure 1B). The differential diagnosis included basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and cutaneous metastases from esophageal adenocarcinoma. Shave biopsies were taken of both scalp lesions.

Histologic examination of both scalp lesions demonstrated a dermal gland-forming neoplasm with an infiltrative distribution that was comprised of irregular cribriform glands containing cellular debris (Figure 2). The cells of interest were enlarged and contained pleomorphic crowded nuclei that formed aberrant mitotic division figures. Both biopsies were positive for cytokeratin 7 and negative for cytokeratin 20 and CDX2. The final diagnosis for both scalp lesions was poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma, which was most suggestive of cutaneous metastases of the patient’s known esophageal adenocarcinoma. Given further metastasis, the patient was ultimately switched to ramucirumab and paclitaxel per oncology.

Esophageal carcinoma is the eighth most common cause of death related to cancer worldwide. Adenocarcinoma is the most prevalent histologic type of esophageal carcinoma, with an incidence as high as 5.69 per 100,000 individuals in the United States.1 Internal malignancies that lead to cutaneous metastases are not uncommon; however, the literature is limited on cutaneous scalp metastases from esophageal cancer. Cutaneous metastases secondary to internal malignancies present in less than 10% of overall cases; tend to derive from the breasts, lungs, and large bowel; and usually present in the sixth to seventh decades of life.2 Further, roughly 1% of all skin metastases originate from the esophagus.3 When there are cutaneous metastases to the scalp, they often arise from breast carcinomas and renal cell carcinomas.4,5 Rarely does esophageal cancer spread to the scalp.2,6-9 When cutaneous metastases originate from the esophagus, multiple cancers such as squamous cell carcinomas, mucoepidermoid carcinomas, small cell carcinomas, and adenocarcinomas can be the etiology of origin.10 Metastases originating from esophageal carcinomas frequently are diagnosed in the abdominal lymph nodes (45%), liver (35%), lungs (20%), cervical/supraclavicular lymph nodes (18%), bones (9%), adrenals (5%), peritoneum (2%), brain (2%), stomach (1%), pancreas (1%), pleura (1%), skin/body wall (1%), pericardium (1%), and spleen (1%).3 Additionally, multiple cutaneous scalp metastases from esophageal adenocarcinoma have been reported,7,9 as were seen in our case.

The clinical appearance of cutaneous scalp metastases has been described as inflammatory papules, indurated plaques, or nodules,2 which is consistent with our case, though the spectrum of presentation is admittedly broad. Histopathology of lesions characteristically shows prominent intraluminal necrotic cellular debris, which is common for adenocarcinomas of the gastrointestinal tract.7 However, utilizing immunohistochemical stains to detect specific antigens within tumor cells allows for better specificity of the tumor origin. More specifically, cytokeratin 7 and cytokeratin 20 are stained in esophageal metaplasia, such as Barrett esophagus, rather than in intestinal metaplasia inside the stomach.2,11 Therefore, discerning the location of the adenocarcinoma proves fruitful when using cytokeratin 7 and cytokeratin 20. Although CDX2 is an additional marker that can be used for gastrointestinal adenocarcinomas with decent sensitivity and specificity, it can still be expressed in mucinous ovarian carcinomas and urinary bladder adenocarcinomas.12 In our patient, the strong reactivity of cytokeratin 7 in addition to the characteristic morphology in both presenting biopsies was sufficient to make the diagnosis of cutaneous metastasis of esophageal adenocarcinoma to the scalp.

Our case highlights multiple cutaneous metastases of the scalp from a primary esophageal adenocarcinoma. Although cutaneous scalp metastasis of esophageal adenocarcinoma is rare, it is essential to provide a full-body skin examination, including the scalp, in patients with a history of esophageal cancer and to biopsy any suspicious nodules or plaques. The 1-year survival rate after diagnosis of esophageal carcinoma is less than 50%, and the 5-year survival rate is less than 10%.13 Identifying cutaneous metastasis of an esophageal adenocarcinoma can either change the staging of the cancer (if it was the first distant metastasis noted) or indicate an insufficient response to treatment in a patient with known metastatic disease, prompting a potential change in treatment.7

This case illustrates a rare site of metastasis of a fairly common cancer and highlights the histopathology and accompanying immunohistochemical stains that can be useful in diagnosis as well as the spectrum of its clinical presentation.

To the Editor:

A 59-year-old man presented with a lesion on the right frontal scalp of 4 months’ duration and a lesion on the left frontal scalp of 1 month’s duration. Both lesions were tender, bleeding, nonhealing, and growing in size. The patient reported no improvement with the use of triple antibiotic ointment. He denied any associated symptoms or trauma to the affected areas. He had a history of stage IV esophageal adenocarcinoma that initially had been surgically removed 6 years prior but metastasized to the lungs and bone. The patient subsequently underwent treatment with FOLFOX (folinic acid, fluorouracil, oxaliplatin), trastuzumab, and radiation therapy.

Physical examination revealed a hyperkeratotic pink nodule with a central erosion and crust on the right frontal scalp measuring 1.5×2 cm in diameter (Figure 1A). The left frontal scalp lesion was a smooth pearly papule measuring 5×5 mm in diameter (Figure 1B). The differential diagnosis included basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and cutaneous metastases from esophageal adenocarcinoma. Shave biopsies were taken of both scalp lesions.

Histologic examination of both scalp lesions demonstrated a dermal gland-forming neoplasm with an infiltrative distribution that was comprised of irregular cribriform glands containing cellular debris (Figure 2). The cells of interest were enlarged and contained pleomorphic crowded nuclei that formed aberrant mitotic division figures. Both biopsies were positive for cytokeratin 7 and negative for cytokeratin 20 and CDX2. The final diagnosis for both scalp lesions was poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma, which was most suggestive of cutaneous metastases of the patient’s known esophageal adenocarcinoma. Given further metastasis, the patient was ultimately switched to ramucirumab and paclitaxel per oncology.

Esophageal carcinoma is the eighth most common cause of death related to cancer worldwide. Adenocarcinoma is the most prevalent histologic type of esophageal carcinoma, with an incidence as high as 5.69 per 100,000 individuals in the United States.1 Internal malignancies that lead to cutaneous metastases are not uncommon; however, the literature is limited on cutaneous scalp metastases from esophageal cancer. Cutaneous metastases secondary to internal malignancies present in less than 10% of overall cases; tend to derive from the breasts, lungs, and large bowel; and usually present in the sixth to seventh decades of life.2 Further, roughly 1% of all skin metastases originate from the esophagus.3 When there are cutaneous metastases to the scalp, they often arise from breast carcinomas and renal cell carcinomas.4,5 Rarely does esophageal cancer spread to the scalp.2,6-9 When cutaneous metastases originate from the esophagus, multiple cancers such as squamous cell carcinomas, mucoepidermoid carcinomas, small cell carcinomas, and adenocarcinomas can be the etiology of origin.10 Metastases originating from esophageal carcinomas frequently are diagnosed in the abdominal lymph nodes (45%), liver (35%), lungs (20%), cervical/supraclavicular lymph nodes (18%), bones (9%), adrenals (5%), peritoneum (2%), brain (2%), stomach (1%), pancreas (1%), pleura (1%), skin/body wall (1%), pericardium (1%), and spleen (1%).3 Additionally, multiple cutaneous scalp metastases from esophageal adenocarcinoma have been reported,7,9 as were seen in our case.

The clinical appearance of cutaneous scalp metastases has been described as inflammatory papules, indurated plaques, or nodules,2 which is consistent with our case, though the spectrum of presentation is admittedly broad. Histopathology of lesions characteristically shows prominent intraluminal necrotic cellular debris, which is common for adenocarcinomas of the gastrointestinal tract.7 However, utilizing immunohistochemical stains to detect specific antigens within tumor cells allows for better specificity of the tumor origin. More specifically, cytokeratin 7 and cytokeratin 20 are stained in esophageal metaplasia, such as Barrett esophagus, rather than in intestinal metaplasia inside the stomach.2,11 Therefore, discerning the location of the adenocarcinoma proves fruitful when using cytokeratin 7 and cytokeratin 20. Although CDX2 is an additional marker that can be used for gastrointestinal adenocarcinomas with decent sensitivity and specificity, it can still be expressed in mucinous ovarian carcinomas and urinary bladder adenocarcinomas.12 In our patient, the strong reactivity of cytokeratin 7 in addition to the characteristic morphology in both presenting biopsies was sufficient to make the diagnosis of cutaneous metastasis of esophageal adenocarcinoma to the scalp.

Our case highlights multiple cutaneous metastases of the scalp from a primary esophageal adenocarcinoma. Although cutaneous scalp metastasis of esophageal adenocarcinoma is rare, it is essential to provide a full-body skin examination, including the scalp, in patients with a history of esophageal cancer and to biopsy any suspicious nodules or plaques. The 1-year survival rate after diagnosis of esophageal carcinoma is less than 50%, and the 5-year survival rate is less than 10%.13 Identifying cutaneous metastasis of an esophageal adenocarcinoma can either change the staging of the cancer (if it was the first distant metastasis noted) or indicate an insufficient response to treatment in a patient with known metastatic disease, prompting a potential change in treatment.7

This case illustrates a rare site of metastasis of a fairly common cancer and highlights the histopathology and accompanying immunohistochemical stains that can be useful in diagnosis as well as the spectrum of its clinical presentation.

- Melhado R, Alderson D, Tucker O. The changing face of esophageal cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2010;2:1379-1404.

- Park JM, Kim DS, Oh SH, et al. A case of esophageal adenocarcinoma metastasized to the scalp [published online May 31, 2009]. Ann Dermatol. 2009;21:164-167.

- Quint LE, Hepburn LM, Francis IR, et al. Incidence and distribution of distant metastases from newly diagnosed esophageal carcinoma. Cancer. 1995;76:1120.

- Dobson C, Tagor V, Myint A, et al. Telangiectatic metastatic breast carcinoma in face and scalp mimicking cutaneous angiosarcoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:635-636.

- Riter H, Ghobrial I. Renal cell carcinoma with acrometastasis and scalp metastasis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2004;79:76.

- Roh EK, Nord R, Jukic DM. Scalp metastasis from esophageal adenocarcinoma. Cutis. 2006;77:106.

- Doumit G, Abouhassan W, Piliang M, et al. Scalp metastasis from esophageal adenocarcinoma: comparative histopathology dictates surgical approach. Ann Plast Surg. 2011;71:60-62.

- Roy AD, Sherparpa M, Prasad PR, et al. Scalp metastasis of gastro-esophageal junction adenocarcinoma: a rare occurrence. 2014;8:159-160.

- Stein R, Spencer J. Painful cutaneous metastases from esophageal carcinoma. Cutis. 2002;70:230.

- Schwartz RA. Cutaneous metastatic disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33(2 pt 1):161-182.

- Ormsby AH, Goldblum JR, Rice TW, et al. Cytokeratin subsets can reliably distinguish Barrett’s esophagus from intestinal metaplasia of the stomach. Hum Pathol. 1999;30:288-294.

- Werling RW, Yaziji H, Bacchi CE, et al. CDX2, a highly sensitive and specific marker of adenocarcinomas of intestinal origin: an immunohistochemical survey of 476 primary and metastatic carcinomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:303-310.

- Smith KJ, Williams J, Skelton H. Metastatic adenocarcinoma of the esophagus to the skin: new patterns of tumor recurrence and alternate treatments for palliation. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:425-431.

- Melhado R, Alderson D, Tucker O. The changing face of esophageal cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2010;2:1379-1404.

- Park JM, Kim DS, Oh SH, et al. A case of esophageal adenocarcinoma metastasized to the scalp [published online May 31, 2009]. Ann Dermatol. 2009;21:164-167.

- Quint LE, Hepburn LM, Francis IR, et al. Incidence and distribution of distant metastases from newly diagnosed esophageal carcinoma. Cancer. 1995;76:1120.

- Dobson C, Tagor V, Myint A, et al. Telangiectatic metastatic breast carcinoma in face and scalp mimicking cutaneous angiosarcoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:635-636.

- Riter H, Ghobrial I. Renal cell carcinoma with acrometastasis and scalp metastasis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2004;79:76.

- Roh EK, Nord R, Jukic DM. Scalp metastasis from esophageal adenocarcinoma. Cutis. 2006;77:106.

- Doumit G, Abouhassan W, Piliang M, et al. Scalp metastasis from esophageal adenocarcinoma: comparative histopathology dictates surgical approach. Ann Plast Surg. 2011;71:60-62.

- Roy AD, Sherparpa M, Prasad PR, et al. Scalp metastasis of gastro-esophageal junction adenocarcinoma: a rare occurrence. 2014;8:159-160.

- Stein R, Spencer J. Painful cutaneous metastases from esophageal carcinoma. Cutis. 2002;70:230.

- Schwartz RA. Cutaneous metastatic disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33(2 pt 1):161-182.

- Ormsby AH, Goldblum JR, Rice TW, et al. Cytokeratin subsets can reliably distinguish Barrett’s esophagus from intestinal metaplasia of the stomach. Hum Pathol. 1999;30:288-294.

- Werling RW, Yaziji H, Bacchi CE, et al. CDX2, a highly sensitive and specific marker of adenocarcinomas of intestinal origin: an immunohistochemical survey of 476 primary and metastatic carcinomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:303-310.

- Smith KJ, Williams J, Skelton H. Metastatic adenocarcinoma of the esophagus to the skin: new patterns of tumor recurrence and alternate treatments for palliation. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:425-431.

Practice Points

- In the setting of underlying esophageal adenocarcinoma, metastatic spread to the scalp should be considered in the differential diagnosis for any suspicious scalp lesions.

- Coupling histopathology with immunohistochemical stains may aid in the diagnosis for cutaneous metastasis of esophageal adenocarcinoma.

Smooth Papules on the Left Hand

The Diagnosis: Adult Colloid Milium

A 4-mm punch biopsy was performed and histopathologic evaluation revealed collections of amorphic eosinophilic material and fissures in the papillary dermis with sparing of the dermoepidermal junction, indicating adult colloid milium (Figure 1).

Adult colloid milium is an uncommon condition with grouped translucent to whitish papules that present on sun-exposed skin on the hands, face, neck, or ears in middle-aged adults.1 It has been associated with petrochemical exposure, tanning bed use, and excessive sun exposure. Our patient had a history of sun exposure, specifically to the left hand while driving. This condition is widely thought to be a result of photoinduced damage to elastic fibers and may potentially be a popular variant of severe solar elastosis.2 Due to vascular fragility, trauma to these locations often will result in hemorrhage into individual lesions, as observed in our patient (Figure 2).

Adult colloid milium is diagnosed clinically and may mimic lichen or systemic amyloidosis, syringomas, lipoid proteinosis, molluscum contagiosum, steatocystoma multiplex, and sarcoidosis.2

Biopsy often is helpful in determining the diagnosis. Histopathology reveals amorphous eosinophilic deposits with fissures in the papillary dermis. These deposits are thought to be remnants of degenerated elastic fibers. Stains often are helpful, as the deposits are weakly apple-green birefringent on Congo red stain and are periodic acid-Schiff and thioflavin T positive. Laminin and type IV collagen stains are negative with adult colloid milium but are positive with amyloidosis and lipoid proteinosis.3 Electron microscopy also may help distinguish between amyloidosis and adult colloid milium, as these conditions may have a similar histologic appearance.

Treatment has not proven to be consistently helpful, as cryotherapy and dermabrasion have been the mainstay of treatment, often with disappointing results.4 Laser treatment has been shown to be of some benefit in treating these lesions.2

- Touart DM, Sau P. Cutaneous deposition diseases. part I. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39(2, pt 1):149-171.

- Pourrabbani S, Marra DE, Iwasaki J, et al. Colloid milium: a review and update. J Drugs Dermatol. 2007;6:293-296.

- Calonje JE, Brenn T, Lazar A, et al. McKee's Pathology of the Skin. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2012.

- Netscher DT, Sharma S, Kinner BM, et al. Adult-type colloid milium of hands and face successfully treated with dermabrasion. South Med J. 1996;89:1004-1007.

The Diagnosis: Adult Colloid Milium

A 4-mm punch biopsy was performed and histopathologic evaluation revealed collections of amorphic eosinophilic material and fissures in the papillary dermis with sparing of the dermoepidermal junction, indicating adult colloid milium (Figure 1).

Adult colloid milium is an uncommon condition with grouped translucent to whitish papules that present on sun-exposed skin on the hands, face, neck, or ears in middle-aged adults.1 It has been associated with petrochemical exposure, tanning bed use, and excessive sun exposure. Our patient had a history of sun exposure, specifically to the left hand while driving. This condition is widely thought to be a result of photoinduced damage to elastic fibers and may potentially be a popular variant of severe solar elastosis.2 Due to vascular fragility, trauma to these locations often will result in hemorrhage into individual lesions, as observed in our patient (Figure 2).

Adult colloid milium is diagnosed clinically and may mimic lichen or systemic amyloidosis, syringomas, lipoid proteinosis, molluscum contagiosum, steatocystoma multiplex, and sarcoidosis.2

Biopsy often is helpful in determining the diagnosis. Histopathology reveals amorphous eosinophilic deposits with fissures in the papillary dermis. These deposits are thought to be remnants of degenerated elastic fibers. Stains often are helpful, as the deposits are weakly apple-green birefringent on Congo red stain and are periodic acid-Schiff and thioflavin T positive. Laminin and type IV collagen stains are negative with adult colloid milium but are positive with amyloidosis and lipoid proteinosis.3 Electron microscopy also may help distinguish between amyloidosis and adult colloid milium, as these conditions may have a similar histologic appearance.

Treatment has not proven to be consistently helpful, as cryotherapy and dermabrasion have been the mainstay of treatment, often with disappointing results.4 Laser treatment has been shown to be of some benefit in treating these lesions.2

The Diagnosis: Adult Colloid Milium

A 4-mm punch biopsy was performed and histopathologic evaluation revealed collections of amorphic eosinophilic material and fissures in the papillary dermis with sparing of the dermoepidermal junction, indicating adult colloid milium (Figure 1).

Adult colloid milium is an uncommon condition with grouped translucent to whitish papules that present on sun-exposed skin on the hands, face, neck, or ears in middle-aged adults.1 It has been associated with petrochemical exposure, tanning bed use, and excessive sun exposure. Our patient had a history of sun exposure, specifically to the left hand while driving. This condition is widely thought to be a result of photoinduced damage to elastic fibers and may potentially be a popular variant of severe solar elastosis.2 Due to vascular fragility, trauma to these locations often will result in hemorrhage into individual lesions, as observed in our patient (Figure 2).

Adult colloid milium is diagnosed clinically and may mimic lichen or systemic amyloidosis, syringomas, lipoid proteinosis, molluscum contagiosum, steatocystoma multiplex, and sarcoidosis.2

Biopsy often is helpful in determining the diagnosis. Histopathology reveals amorphous eosinophilic deposits with fissures in the papillary dermis. These deposits are thought to be remnants of degenerated elastic fibers. Stains often are helpful, as the deposits are weakly apple-green birefringent on Congo red stain and are periodic acid-Schiff and thioflavin T positive. Laminin and type IV collagen stains are negative with adult colloid milium but are positive with amyloidosis and lipoid proteinosis.3 Electron microscopy also may help distinguish between amyloidosis and adult colloid milium, as these conditions may have a similar histologic appearance.

Treatment has not proven to be consistently helpful, as cryotherapy and dermabrasion have been the mainstay of treatment, often with disappointing results.4 Laser treatment has been shown to be of some benefit in treating these lesions.2

- Touart DM, Sau P. Cutaneous deposition diseases. part I. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39(2, pt 1):149-171.

- Pourrabbani S, Marra DE, Iwasaki J, et al. Colloid milium: a review and update. J Drugs Dermatol. 2007;6:293-296.

- Calonje JE, Brenn T, Lazar A, et al. McKee's Pathology of the Skin. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2012.

- Netscher DT, Sharma S, Kinner BM, et al. Adult-type colloid milium of hands and face successfully treated with dermabrasion. South Med J. 1996;89:1004-1007.

- Touart DM, Sau P. Cutaneous deposition diseases. part I. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39(2, pt 1):149-171.

- Pourrabbani S, Marra DE, Iwasaki J, et al. Colloid milium: a review and update. J Drugs Dermatol. 2007;6:293-296.

- Calonje JE, Brenn T, Lazar A, et al. McKee's Pathology of the Skin. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2012.

- Netscher DT, Sharma S, Kinner BM, et al. Adult-type colloid milium of hands and face successfully treated with dermabrasion. South Med J. 1996;89:1004-1007.

A 41-year-old man presented to the outpatient dermatology clinic with multiple smooth papules on the left hand of 7 years' duration. The papules had been steadily increasing in number, and the patient reported that they were frequently symptomatic with a burning itching sensation. Physical examination revealed multiple 1- to 3-mm, dome-shaped, translucent to flesh-colored papules on the left hand with a few scattered bright red papules. No similar lesions were present on the right hand or elsewhere on the body. He had a history of hypertension but was otherwise healthy with no other chronic medical conditions.

Painful and Pruritic Erosions on the Back

The Diagnosis: Bullous Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus (BSLE) is a rare blistering disease that affects patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Our patient had a several-year history of SLE and was being managed by a rheumatologist. She was taking hydroxychloroquine at the time of the flare. Although BSLE tends to present in those with SLE that has already been diagnosed, BSLE has been reported as a possible initial manifestation of SLE.1

Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus is estimated to occur in less than 5% of patients with SLE and is more common in black women between the second and third decades of life,2 though it also can be seen in the pediatric population.3 The lesions of BSLE usually present as subepidermal blisters often located on the face, neck, and arms on an erythematous or possibly urticarial base. Although non-BSLE vesiculobullous eruptions may be seen in patients with SLE, BSLE is differentiated from these other eruptions by its appearance on sun-exposed and non-sun-exposed areas of the body, while other vesiculobullous eruptions associated with SLE typically are limited to sun-exposed sites.4

Due to its clinical presentation overlapping with several vesiculobullous conditions, a set of diagnostic criteria have been suggested for BSLE, including the following: (1) fulfillment of the American Rheumatism Association's criteria for SLE5; (2) a new-onset vesiculobullous eruption, primarily on sun-exposed skin; (3) histology showing a subepidermal blister with a predominantly neutrophilic infiltrate; (4) presence of IgG, IgA, IgM, and C3 at the basement membrane zone; (5) evidence of antibodies to type VII collagen; and (6) immunoelectron microscopy showing codistribution of immunoglobulin deposits with anchoring fibrils/type VII collagen. To meet the diagnosis of type I BSLE, all 6 criteria must be satisfied. To meet the diagnosis of type II BSLE, only criteria 1 to 4 need to be satisfied.6