User login

Anti–PD1 Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor–Induced Bullous Pemphigoid in Metastatic Melanoma and Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer

Immune checkpoint inhibitors are used for a variety of advanced malignancies, including melanoma, non–small cell lung cancer, urothelial cancer, and renal cell carcinoma. Anti–programmed cell death 1 (PD1) targeted therapies, such as pembrolizumab and nivolumab, are improving patient survival. This class of immunotherapy is revolutionary but is associated with autoimmune adverse effects. A rare but increasingly reported adverse effect of anti-PD1 therapy is bullous pemphigoid (BP), an autoimmune blistering disease directed against

High clinical suspicion, early diagnosis, and proper management of immunotherapy-related BP are imperative for keeping patients on life-prolonging treatment. We present 3 cases of BP secondary to anti-PD1 immunotherapy in patients with melanoma or non–small cell lung cancer to highlight the diagnosis and treatment of BP as well as emphasize the importance of the dermatologist in the care of patients with immunotherapy-related skin disease.

Case Reports

Patient 1

A 72-year-old woman with metastatic BRAF-mutated melanoma from an unknown primary site presented with intensely pruritic papules on the back, chest, and extremities of 4 months’ duration. She described her symptoms as insidious in onset and refractory to clobetasol ointment, oral diphenhydramine, and over-the-counter anti-itch creams. The patient had been treated with oral dabrafenib 150 mg twice daily and trametinib 2 mg/d but was switched to pembrolizumab when the disease progressed. After 8 months, she had a complete radiologic response to pembrolizumab 2 mg/kg every 3 weeks, which was discontinued in favor of observation 3 months prior to presentation to dermatology.

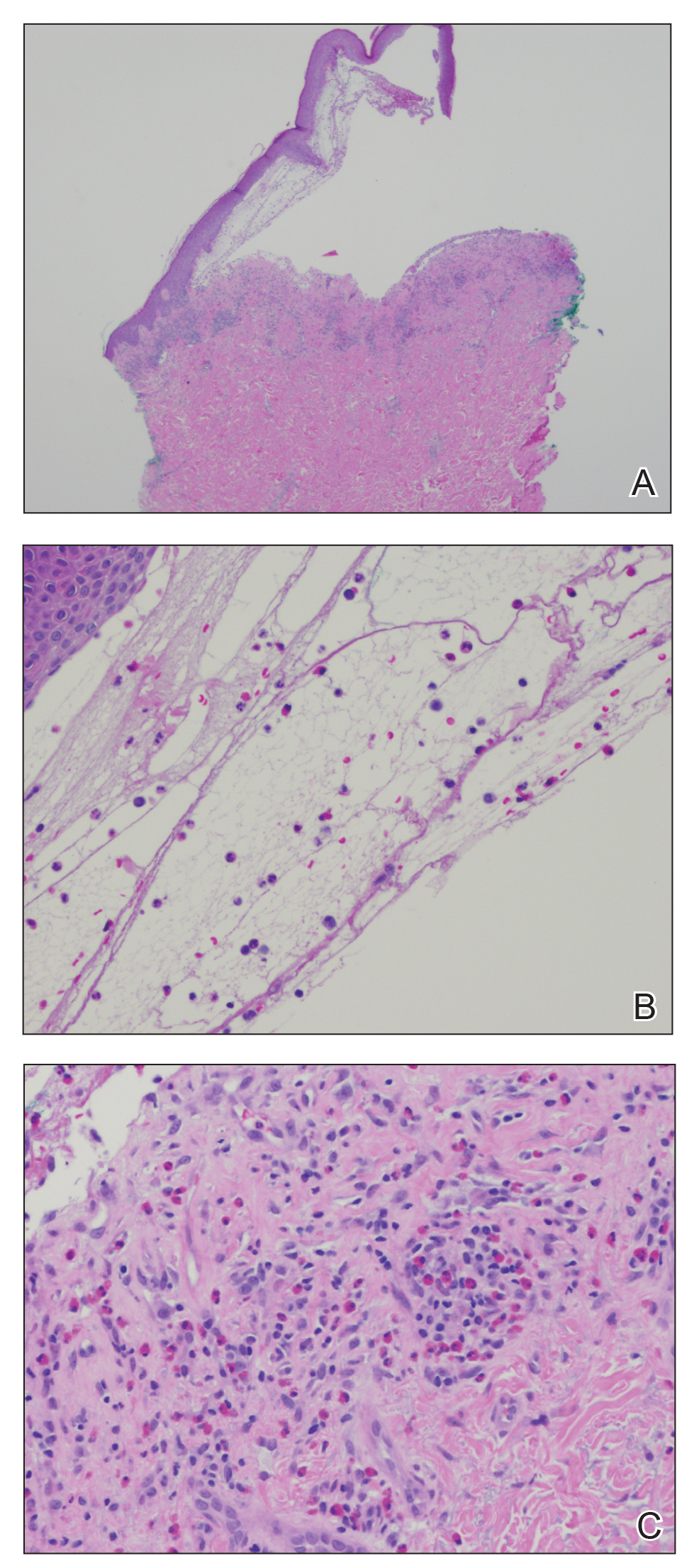

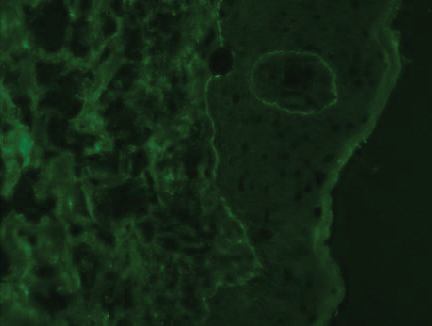

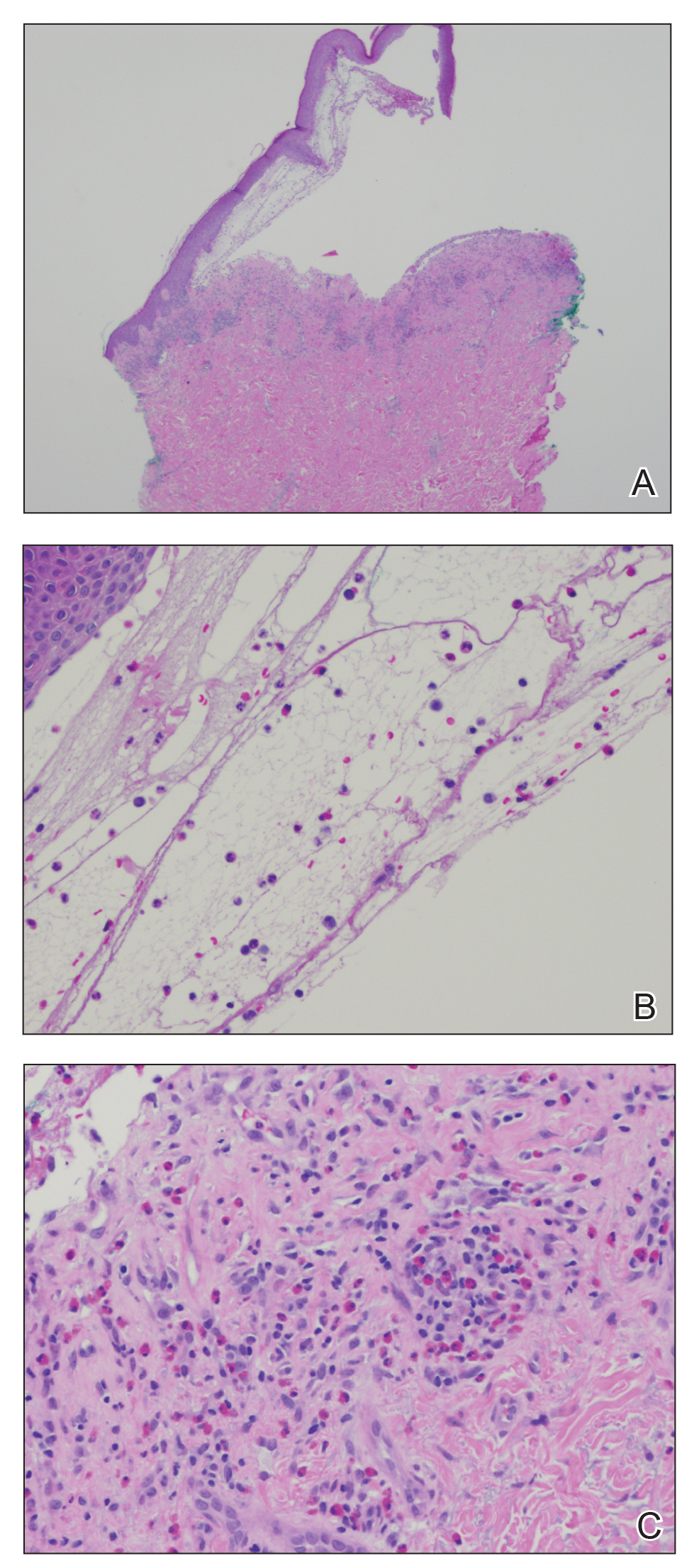

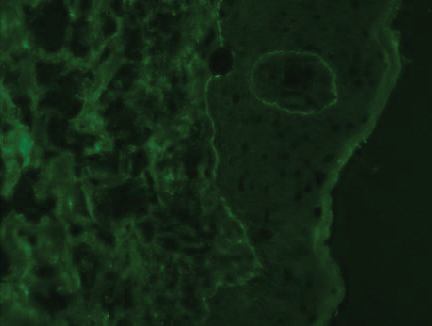

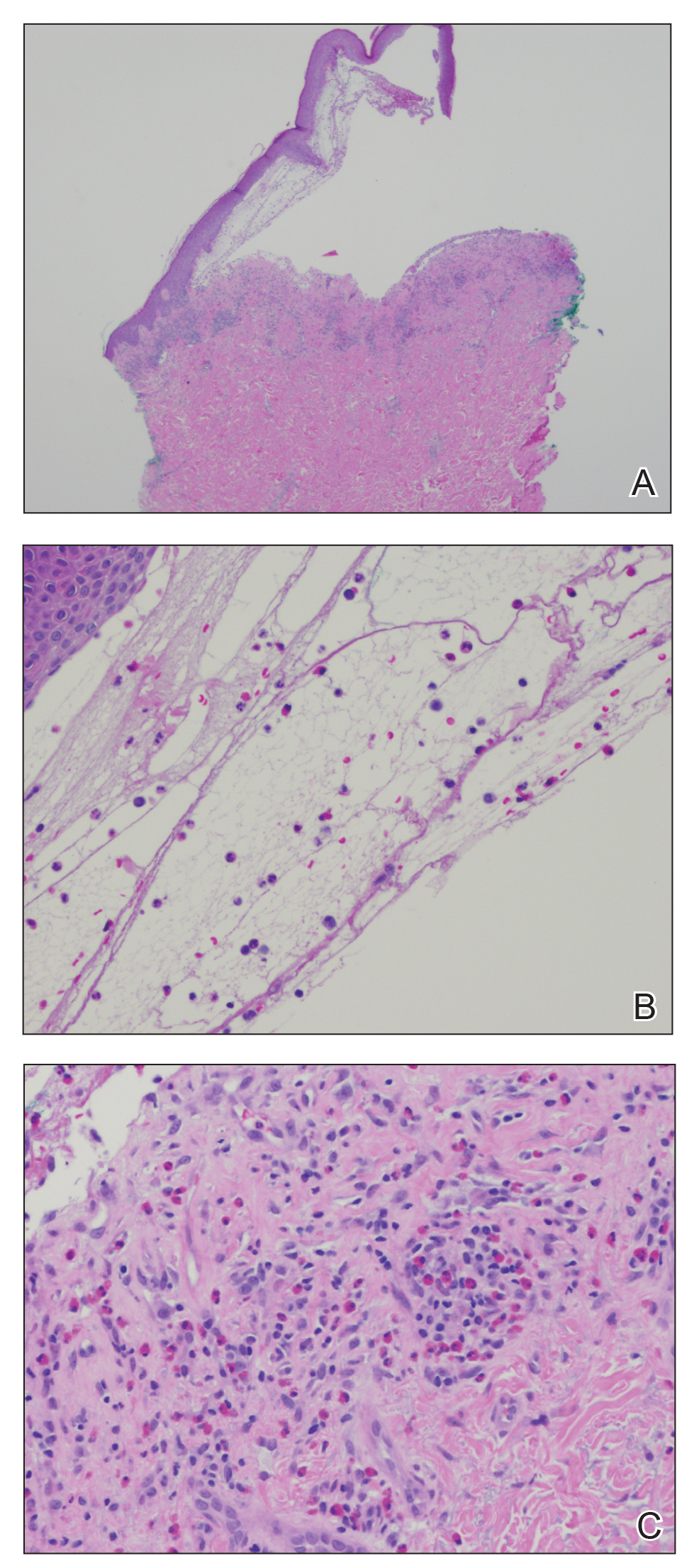

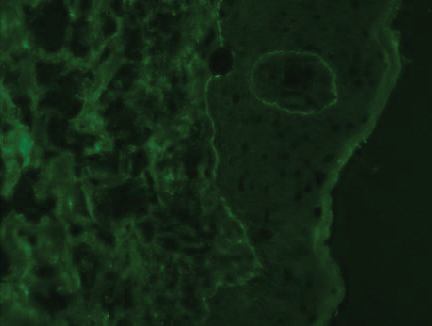

At the current presentation, physical examination revealed innumerable erythematous, excoriated, 2- to 4-mm, red papules diffusely scattered on the upper back, chest, abdomen, and thighs, with one 8×4-mm vesicle on the right side of the upper back (Figure 1). Discrete areas of depigmented macules, consistent with vitiligo, coalesced into patches on the legs, thighs, arms, and back. The patient was started on a 3-week oral prednisone taper for symptom relief. A hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)–stained punch biopsy of the back revealed a subepidermal split with eosinophils and a dense eosinophilic infiltrate in the dermis (Figure 2). Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) studies from a specimen adjacent to the biopsy collected for H&E staining showed linear deposition of IgA, IgG, and C3 along the dermoepidermal junction (Figure 3). Histologic findings were consistent with BP.

The patient was started on doxycycline 100 mg twice daily and clobetasol ointment 0.05% once daily to supplement the prednisone taper. At 3-week follow-up, she reported pruritus and a few erythematous macules but no new bullae. At 12 weeks, some papules persisted; however, the patient was averse to using systemic agents and decided that symptoms were adequately controlled with clobetasol ointment and oral doxycycline.

Because the patient currently remains in clinical and radiologic remission, anti-PD1 immune checkpoint inhibitors have not been restarted but remain an option for the future if disease recurs

Patient 2

An 82-year-old man with a history of stage IIC desmoplastic melanoma presented to dermatology with an intensely pruritic eruption on the legs, arms, waist, upper torso, and scalp of 3 weeks’ duration. Clobetasol ointment had provided minimal relief.

Six months prior to presenting to dermatology, the patient underwent immunotherapy with 4 cycles of ipilimumab 200 mg intravenous (IV) and nivolumab 240 mg IV every 2 weeks, receiving ipilimumab during the first cycle only because of a lack of availability at the pharmacy. He then received nivolumab 240 mg IV every 2 weeks as maintenance therapy. After the second dose of nivolumab maintenance therapy, however, he developed generalized bullae and pruritus. Dermatology was consulted during an oncology appointment, and his oncologist decided to hold nivolumab.

Physical examination revealed generalized tense and eroded bullae covering more than 50% of the body surface area and affecting the scalp, arms, legs, torso, and buttocks. Two punch biopsies were obtained. Hematoxylin and eosin staining revealed a subepidermal split with predominantly eosinophils and scattered neutrophils. Direct immunofluorescence studies showed linear deposition of IgG, IgA, and C3 along the dermoepidermal junction, consistent with BP.

The patient’s BP was difficult to control, requiring several hospital admissions for wound care, high-dose systemic steroids, and initiation of mycophenolate mofetil. After 4 months of waxing and waning symptoms, the BP was controlled with mycophenolate mofetil 1500 mg/d; clobetasol ointment 0.05%; and diphenhydramine for pruritus. Due to the prolonged recovery and severity of BP, the patient’s oncologist deemed that he was not a candidate for future immunotherapy.

Patient 3

A 68-year-old man with PD1-negative, metastatic, well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma of the lung presented to dermatology with a pruritic rash of 3 weeks’ duration. He had been receiving nivolumab for 2 years after disease progressed on prior chemotherapies and experienced several grade 1 or grade 2 nivolumab-induced autoimmune reactions including thyroiditis, dermatitis, and nephritis, for which he was taking prednisone 5 mg/d for suppression.

Physical examination revealed psoriasiform pink plaques on the arms, chest, and legs. The differential diagnosis at the time favored psoriasiform dermatitis over lichenoid dermatitis. A punch biopsy revealed psoriasiform dermatitis. The patient was prescribed fluocinonide ointment 0.05% daily. His plaques improved with topical steroids.

The patient returned approximately 1 month later with a report of a new blistering rash on the legs. Physical examination revealed interval improvement of the psoriasiform plaques on the scalp, torso, and extremities, but tense bullae were seen on the thighs, with surrounding superficial erosions at sites of recent bullae. Punch biopsies of the skin for H&E staining and DIF showed BP.

Prednisone was increased to 50 mg/d for a 3-week taper. Doxycycline 100 mg twice daily was started. The patient’s skin disease continued to be difficult to control with therapy; nivolumab was held by his oncologist.

Comment

Immunotherapy with immune checkpoint blockade represents a successful application of immune recognition to treat metastatic cancers, including melanoma, non–small cell lung cancer, urothelial cancer, and renal cell carcinoma.

Anti-PD1 targeted therapies improve survival in solid and hematologic malignancies, with a response rate as high as 40% in melanoma.2 Although these medications can prolong survival, many are associated with loss of self-tolerance and severe autoimmunelike events that can limit therapy.3 An exception is PD1-induced vitiligo, which patient 1 developed and has been associated with a better response to therapy.4

Anti-PD1–induced BP is a newly reported adverse effect. In its early stages, BP can be difficult to differentiate from eczematous or urticarial dermatitis.5-8 Discontinuation of immunotherapy has been reported in more than 70% of patients who develop BP.1 There are reports of successful treatment of BP with a course of a PD1 inhibitor,9 but 2 of our patients had severe BP that led to discontinuation of immunotherapy.

Consider Prescreening

Given that development of BP often leads to cessation of therapy, identifying patients at risk prior to starting an immune checkpoint inhibitor might have clinical utility. Biopsy with DIF is the gold standard for diagnosis, but serologic testing can be a useful adjunct because enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for BP antigen 1 and BP antigen 2 has a reported sensitivity and specificity of 87% and 98%, respectively.10 Serologic testing prior to starting therapy with an immune checkpoint inhibitor can provide a baseline for patients. A rise in titer, in conjunction with onset of a rash, might aid in earlier diagnosis, particularly because urticarial BP can be difficult to diagnose clinically.

Further study on the utility vs cost-benefit of these screening modalities is warranted. Their predictive utility might be limited, however, and positive serologic test results might have unanticipated consequences, such as hesitation in treating patients, thus leading to a delay in therapy or access to these medications.

Conclusion

The expanding use of immune checkpoint inhibitors is increasing survival in patients with metastatic melanoma and other malignancies. Adverse effects are part of the continuum of immune system stimulation, with overstimulation resulting in dermatitis; thyroiditis; pneumonitis; and less commonly hypophysitis, vitiligo, and colitis.

Rarely, immune checkpoint inhibition induces BP. Development of BP leads to discontinuation of therapy in more than half of reported cases due to lack of adequate treatment for this skin disease and its impact on quality of life. Therefore, quick diagnosis of BP in patients on immunotherapy and successful management techniques can prevent discontinuation of these lifesaving cancer therapies. For that reason, dermatologists play an important role in the management of patients on immune checkpoint inhibitors for cancer.

- Lopez AT, Khanna T, Antonov N, et al. A review of bullous pemphigoid associated with PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:664-669.

- Márquez-Rodas, I, Cerezuela P, Soria A, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitors: therapeutic advances in melanoma. Ann Transl Med. 2015;3:267.

- Friedman CF, Proverbs-Singh TA, Postow MA. Treatment of the immune-related adverse effects of immune checkpoint inhibitors a review. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2:1346-1353.

- Hua C, Boussemart L, Mateus C, et al. Association of vitiligo with tumor response in patients with metastatic melanoma treated with pembrolizumab. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:45-51.

- Hwang SJE, Carlos G, Chou S, et al. Bullous pemphigoid, an autoantibody-mediated disease, is a novel immune-related adverse event in patients treated with anti-programmed cell death 1 antibodies. Melanoma Res. 2016;26:413-416.

- Damsky W, Kole L, Tomayko MM. Development of bullous pemphigoid during nivolumab therapy. JAAD Case Rep. 2016;2:442-444.

- Garje R, Chau JJ, Chung J, et al. Acute flare of bullous pemphigus with pembrolizumab used for treatment of metastatic urothelial cancer. J Immunother. 2018;41:42-44.

- Ito M, Hoashi T, Endo Y, et al. Atypical pemphigus developed in a patient with urothelial carcinoma treated with nivolumab. J Dermatol. 2019;46:e90-e92.

- Chen W-S, Tetzlaff MT, Diwan H, et al. Suprabasal acantholytic dermatologic toxicities associated checkpoint inhibitor therapy: a spectrum of immune reactions from paraneoplastic pemphigus-like to Grover-like lesions. J Cutan Pathol. 2018;45:764-773.

- Muglia C, Bronsnick T, Kirkorian AY, et al. Questioning the specificity and sensitivity of ELISA for bullous pemphigoid diagnosis. Cutis. 2017;99:E27-E30.

Immune checkpoint inhibitors are used for a variety of advanced malignancies, including melanoma, non–small cell lung cancer, urothelial cancer, and renal cell carcinoma. Anti–programmed cell death 1 (PD1) targeted therapies, such as pembrolizumab and nivolumab, are improving patient survival. This class of immunotherapy is revolutionary but is associated with autoimmune adverse effects. A rare but increasingly reported adverse effect of anti-PD1 therapy is bullous pemphigoid (BP), an autoimmune blistering disease directed against

High clinical suspicion, early diagnosis, and proper management of immunotherapy-related BP are imperative for keeping patients on life-prolonging treatment. We present 3 cases of BP secondary to anti-PD1 immunotherapy in patients with melanoma or non–small cell lung cancer to highlight the diagnosis and treatment of BP as well as emphasize the importance of the dermatologist in the care of patients with immunotherapy-related skin disease.

Case Reports

Patient 1

A 72-year-old woman with metastatic BRAF-mutated melanoma from an unknown primary site presented with intensely pruritic papules on the back, chest, and extremities of 4 months’ duration. She described her symptoms as insidious in onset and refractory to clobetasol ointment, oral diphenhydramine, and over-the-counter anti-itch creams. The patient had been treated with oral dabrafenib 150 mg twice daily and trametinib 2 mg/d but was switched to pembrolizumab when the disease progressed. After 8 months, she had a complete radiologic response to pembrolizumab 2 mg/kg every 3 weeks, which was discontinued in favor of observation 3 months prior to presentation to dermatology.

At the current presentation, physical examination revealed innumerable erythematous, excoriated, 2- to 4-mm, red papules diffusely scattered on the upper back, chest, abdomen, and thighs, with one 8×4-mm vesicle on the right side of the upper back (Figure 1). Discrete areas of depigmented macules, consistent with vitiligo, coalesced into patches on the legs, thighs, arms, and back. The patient was started on a 3-week oral prednisone taper for symptom relief. A hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)–stained punch biopsy of the back revealed a subepidermal split with eosinophils and a dense eosinophilic infiltrate in the dermis (Figure 2). Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) studies from a specimen adjacent to the biopsy collected for H&E staining showed linear deposition of IgA, IgG, and C3 along the dermoepidermal junction (Figure 3). Histologic findings were consistent with BP.

The patient was started on doxycycline 100 mg twice daily and clobetasol ointment 0.05% once daily to supplement the prednisone taper. At 3-week follow-up, she reported pruritus and a few erythematous macules but no new bullae. At 12 weeks, some papules persisted; however, the patient was averse to using systemic agents and decided that symptoms were adequately controlled with clobetasol ointment and oral doxycycline.

Because the patient currently remains in clinical and radiologic remission, anti-PD1 immune checkpoint inhibitors have not been restarted but remain an option for the future if disease recurs

Patient 2

An 82-year-old man with a history of stage IIC desmoplastic melanoma presented to dermatology with an intensely pruritic eruption on the legs, arms, waist, upper torso, and scalp of 3 weeks’ duration. Clobetasol ointment had provided minimal relief.

Six months prior to presenting to dermatology, the patient underwent immunotherapy with 4 cycles of ipilimumab 200 mg intravenous (IV) and nivolumab 240 mg IV every 2 weeks, receiving ipilimumab during the first cycle only because of a lack of availability at the pharmacy. He then received nivolumab 240 mg IV every 2 weeks as maintenance therapy. After the second dose of nivolumab maintenance therapy, however, he developed generalized bullae and pruritus. Dermatology was consulted during an oncology appointment, and his oncologist decided to hold nivolumab.

Physical examination revealed generalized tense and eroded bullae covering more than 50% of the body surface area and affecting the scalp, arms, legs, torso, and buttocks. Two punch biopsies were obtained. Hematoxylin and eosin staining revealed a subepidermal split with predominantly eosinophils and scattered neutrophils. Direct immunofluorescence studies showed linear deposition of IgG, IgA, and C3 along the dermoepidermal junction, consistent with BP.

The patient’s BP was difficult to control, requiring several hospital admissions for wound care, high-dose systemic steroids, and initiation of mycophenolate mofetil. After 4 months of waxing and waning symptoms, the BP was controlled with mycophenolate mofetil 1500 mg/d; clobetasol ointment 0.05%; and diphenhydramine for pruritus. Due to the prolonged recovery and severity of BP, the patient’s oncologist deemed that he was not a candidate for future immunotherapy.

Patient 3

A 68-year-old man with PD1-negative, metastatic, well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma of the lung presented to dermatology with a pruritic rash of 3 weeks’ duration. He had been receiving nivolumab for 2 years after disease progressed on prior chemotherapies and experienced several grade 1 or grade 2 nivolumab-induced autoimmune reactions including thyroiditis, dermatitis, and nephritis, for which he was taking prednisone 5 mg/d for suppression.

Physical examination revealed psoriasiform pink plaques on the arms, chest, and legs. The differential diagnosis at the time favored psoriasiform dermatitis over lichenoid dermatitis. A punch biopsy revealed psoriasiform dermatitis. The patient was prescribed fluocinonide ointment 0.05% daily. His plaques improved with topical steroids.

The patient returned approximately 1 month later with a report of a new blistering rash on the legs. Physical examination revealed interval improvement of the psoriasiform plaques on the scalp, torso, and extremities, but tense bullae were seen on the thighs, with surrounding superficial erosions at sites of recent bullae. Punch biopsies of the skin for H&E staining and DIF showed BP.

Prednisone was increased to 50 mg/d for a 3-week taper. Doxycycline 100 mg twice daily was started. The patient’s skin disease continued to be difficult to control with therapy; nivolumab was held by his oncologist.

Comment

Immunotherapy with immune checkpoint blockade represents a successful application of immune recognition to treat metastatic cancers, including melanoma, non–small cell lung cancer, urothelial cancer, and renal cell carcinoma.

Anti-PD1 targeted therapies improve survival in solid and hematologic malignancies, with a response rate as high as 40% in melanoma.2 Although these medications can prolong survival, many are associated with loss of self-tolerance and severe autoimmunelike events that can limit therapy.3 An exception is PD1-induced vitiligo, which patient 1 developed and has been associated with a better response to therapy.4

Anti-PD1–induced BP is a newly reported adverse effect. In its early stages, BP can be difficult to differentiate from eczematous or urticarial dermatitis.5-8 Discontinuation of immunotherapy has been reported in more than 70% of patients who develop BP.1 There are reports of successful treatment of BP with a course of a PD1 inhibitor,9 but 2 of our patients had severe BP that led to discontinuation of immunotherapy.

Consider Prescreening

Given that development of BP often leads to cessation of therapy, identifying patients at risk prior to starting an immune checkpoint inhibitor might have clinical utility. Biopsy with DIF is the gold standard for diagnosis, but serologic testing can be a useful adjunct because enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for BP antigen 1 and BP antigen 2 has a reported sensitivity and specificity of 87% and 98%, respectively.10 Serologic testing prior to starting therapy with an immune checkpoint inhibitor can provide a baseline for patients. A rise in titer, in conjunction with onset of a rash, might aid in earlier diagnosis, particularly because urticarial BP can be difficult to diagnose clinically.

Further study on the utility vs cost-benefit of these screening modalities is warranted. Their predictive utility might be limited, however, and positive serologic test results might have unanticipated consequences, such as hesitation in treating patients, thus leading to a delay in therapy or access to these medications.

Conclusion

The expanding use of immune checkpoint inhibitors is increasing survival in patients with metastatic melanoma and other malignancies. Adverse effects are part of the continuum of immune system stimulation, with overstimulation resulting in dermatitis; thyroiditis; pneumonitis; and less commonly hypophysitis, vitiligo, and colitis.

Rarely, immune checkpoint inhibition induces BP. Development of BP leads to discontinuation of therapy in more than half of reported cases due to lack of adequate treatment for this skin disease and its impact on quality of life. Therefore, quick diagnosis of BP in patients on immunotherapy and successful management techniques can prevent discontinuation of these lifesaving cancer therapies. For that reason, dermatologists play an important role in the management of patients on immune checkpoint inhibitors for cancer.

Immune checkpoint inhibitors are used for a variety of advanced malignancies, including melanoma, non–small cell lung cancer, urothelial cancer, and renal cell carcinoma. Anti–programmed cell death 1 (PD1) targeted therapies, such as pembrolizumab and nivolumab, are improving patient survival. This class of immunotherapy is revolutionary but is associated with autoimmune adverse effects. A rare but increasingly reported adverse effect of anti-PD1 therapy is bullous pemphigoid (BP), an autoimmune blistering disease directed against

High clinical suspicion, early diagnosis, and proper management of immunotherapy-related BP are imperative for keeping patients on life-prolonging treatment. We present 3 cases of BP secondary to anti-PD1 immunotherapy in patients with melanoma or non–small cell lung cancer to highlight the diagnosis and treatment of BP as well as emphasize the importance of the dermatologist in the care of patients with immunotherapy-related skin disease.

Case Reports

Patient 1

A 72-year-old woman with metastatic BRAF-mutated melanoma from an unknown primary site presented with intensely pruritic papules on the back, chest, and extremities of 4 months’ duration. She described her symptoms as insidious in onset and refractory to clobetasol ointment, oral diphenhydramine, and over-the-counter anti-itch creams. The patient had been treated with oral dabrafenib 150 mg twice daily and trametinib 2 mg/d but was switched to pembrolizumab when the disease progressed. After 8 months, she had a complete radiologic response to pembrolizumab 2 mg/kg every 3 weeks, which was discontinued in favor of observation 3 months prior to presentation to dermatology.

At the current presentation, physical examination revealed innumerable erythematous, excoriated, 2- to 4-mm, red papules diffusely scattered on the upper back, chest, abdomen, and thighs, with one 8×4-mm vesicle on the right side of the upper back (Figure 1). Discrete areas of depigmented macules, consistent with vitiligo, coalesced into patches on the legs, thighs, arms, and back. The patient was started on a 3-week oral prednisone taper for symptom relief. A hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)–stained punch biopsy of the back revealed a subepidermal split with eosinophils and a dense eosinophilic infiltrate in the dermis (Figure 2). Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) studies from a specimen adjacent to the biopsy collected for H&E staining showed linear deposition of IgA, IgG, and C3 along the dermoepidermal junction (Figure 3). Histologic findings were consistent with BP.

The patient was started on doxycycline 100 mg twice daily and clobetasol ointment 0.05% once daily to supplement the prednisone taper. At 3-week follow-up, she reported pruritus and a few erythematous macules but no new bullae. At 12 weeks, some papules persisted; however, the patient was averse to using systemic agents and decided that symptoms were adequately controlled with clobetasol ointment and oral doxycycline.

Because the patient currently remains in clinical and radiologic remission, anti-PD1 immune checkpoint inhibitors have not been restarted but remain an option for the future if disease recurs

Patient 2

An 82-year-old man with a history of stage IIC desmoplastic melanoma presented to dermatology with an intensely pruritic eruption on the legs, arms, waist, upper torso, and scalp of 3 weeks’ duration. Clobetasol ointment had provided minimal relief.

Six months prior to presenting to dermatology, the patient underwent immunotherapy with 4 cycles of ipilimumab 200 mg intravenous (IV) and nivolumab 240 mg IV every 2 weeks, receiving ipilimumab during the first cycle only because of a lack of availability at the pharmacy. He then received nivolumab 240 mg IV every 2 weeks as maintenance therapy. After the second dose of nivolumab maintenance therapy, however, he developed generalized bullae and pruritus. Dermatology was consulted during an oncology appointment, and his oncologist decided to hold nivolumab.

Physical examination revealed generalized tense and eroded bullae covering more than 50% of the body surface area and affecting the scalp, arms, legs, torso, and buttocks. Two punch biopsies were obtained. Hematoxylin and eosin staining revealed a subepidermal split with predominantly eosinophils and scattered neutrophils. Direct immunofluorescence studies showed linear deposition of IgG, IgA, and C3 along the dermoepidermal junction, consistent with BP.

The patient’s BP was difficult to control, requiring several hospital admissions for wound care, high-dose systemic steroids, and initiation of mycophenolate mofetil. After 4 months of waxing and waning symptoms, the BP was controlled with mycophenolate mofetil 1500 mg/d; clobetasol ointment 0.05%; and diphenhydramine for pruritus. Due to the prolonged recovery and severity of BP, the patient’s oncologist deemed that he was not a candidate for future immunotherapy.

Patient 3

A 68-year-old man with PD1-negative, metastatic, well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma of the lung presented to dermatology with a pruritic rash of 3 weeks’ duration. He had been receiving nivolumab for 2 years after disease progressed on prior chemotherapies and experienced several grade 1 or grade 2 nivolumab-induced autoimmune reactions including thyroiditis, dermatitis, and nephritis, for which he was taking prednisone 5 mg/d for suppression.

Physical examination revealed psoriasiform pink plaques on the arms, chest, and legs. The differential diagnosis at the time favored psoriasiform dermatitis over lichenoid dermatitis. A punch biopsy revealed psoriasiform dermatitis. The patient was prescribed fluocinonide ointment 0.05% daily. His plaques improved with topical steroids.

The patient returned approximately 1 month later with a report of a new blistering rash on the legs. Physical examination revealed interval improvement of the psoriasiform plaques on the scalp, torso, and extremities, but tense bullae were seen on the thighs, with surrounding superficial erosions at sites of recent bullae. Punch biopsies of the skin for H&E staining and DIF showed BP.

Prednisone was increased to 50 mg/d for a 3-week taper. Doxycycline 100 mg twice daily was started. The patient’s skin disease continued to be difficult to control with therapy; nivolumab was held by his oncologist.

Comment

Immunotherapy with immune checkpoint blockade represents a successful application of immune recognition to treat metastatic cancers, including melanoma, non–small cell lung cancer, urothelial cancer, and renal cell carcinoma.

Anti-PD1 targeted therapies improve survival in solid and hematologic malignancies, with a response rate as high as 40% in melanoma.2 Although these medications can prolong survival, many are associated with loss of self-tolerance and severe autoimmunelike events that can limit therapy.3 An exception is PD1-induced vitiligo, which patient 1 developed and has been associated with a better response to therapy.4

Anti-PD1–induced BP is a newly reported adverse effect. In its early stages, BP can be difficult to differentiate from eczematous or urticarial dermatitis.5-8 Discontinuation of immunotherapy has been reported in more than 70% of patients who develop BP.1 There are reports of successful treatment of BP with a course of a PD1 inhibitor,9 but 2 of our patients had severe BP that led to discontinuation of immunotherapy.

Consider Prescreening

Given that development of BP often leads to cessation of therapy, identifying patients at risk prior to starting an immune checkpoint inhibitor might have clinical utility. Biopsy with DIF is the gold standard for diagnosis, but serologic testing can be a useful adjunct because enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for BP antigen 1 and BP antigen 2 has a reported sensitivity and specificity of 87% and 98%, respectively.10 Serologic testing prior to starting therapy with an immune checkpoint inhibitor can provide a baseline for patients. A rise in titer, in conjunction with onset of a rash, might aid in earlier diagnosis, particularly because urticarial BP can be difficult to diagnose clinically.

Further study on the utility vs cost-benefit of these screening modalities is warranted. Their predictive utility might be limited, however, and positive serologic test results might have unanticipated consequences, such as hesitation in treating patients, thus leading to a delay in therapy or access to these medications.

Conclusion

The expanding use of immune checkpoint inhibitors is increasing survival in patients with metastatic melanoma and other malignancies. Adverse effects are part of the continuum of immune system stimulation, with overstimulation resulting in dermatitis; thyroiditis; pneumonitis; and less commonly hypophysitis, vitiligo, and colitis.

Rarely, immune checkpoint inhibition induces BP. Development of BP leads to discontinuation of therapy in more than half of reported cases due to lack of adequate treatment for this skin disease and its impact on quality of life. Therefore, quick diagnosis of BP in patients on immunotherapy and successful management techniques can prevent discontinuation of these lifesaving cancer therapies. For that reason, dermatologists play an important role in the management of patients on immune checkpoint inhibitors for cancer.

- Lopez AT, Khanna T, Antonov N, et al. A review of bullous pemphigoid associated with PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:664-669.

- Márquez-Rodas, I, Cerezuela P, Soria A, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitors: therapeutic advances in melanoma. Ann Transl Med. 2015;3:267.

- Friedman CF, Proverbs-Singh TA, Postow MA. Treatment of the immune-related adverse effects of immune checkpoint inhibitors a review. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2:1346-1353.

- Hua C, Boussemart L, Mateus C, et al. Association of vitiligo with tumor response in patients with metastatic melanoma treated with pembrolizumab. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:45-51.

- Hwang SJE, Carlos G, Chou S, et al. Bullous pemphigoid, an autoantibody-mediated disease, is a novel immune-related adverse event in patients treated with anti-programmed cell death 1 antibodies. Melanoma Res. 2016;26:413-416.

- Damsky W, Kole L, Tomayko MM. Development of bullous pemphigoid during nivolumab therapy. JAAD Case Rep. 2016;2:442-444.

- Garje R, Chau JJ, Chung J, et al. Acute flare of bullous pemphigus with pembrolizumab used for treatment of metastatic urothelial cancer. J Immunother. 2018;41:42-44.

- Ito M, Hoashi T, Endo Y, et al. Atypical pemphigus developed in a patient with urothelial carcinoma treated with nivolumab. J Dermatol. 2019;46:e90-e92.

- Chen W-S, Tetzlaff MT, Diwan H, et al. Suprabasal acantholytic dermatologic toxicities associated checkpoint inhibitor therapy: a spectrum of immune reactions from paraneoplastic pemphigus-like to Grover-like lesions. J Cutan Pathol. 2018;45:764-773.

- Muglia C, Bronsnick T, Kirkorian AY, et al. Questioning the specificity and sensitivity of ELISA for bullous pemphigoid diagnosis. Cutis. 2017;99:E27-E30.

- Lopez AT, Khanna T, Antonov N, et al. A review of bullous pemphigoid associated with PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:664-669.

- Márquez-Rodas, I, Cerezuela P, Soria A, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitors: therapeutic advances in melanoma. Ann Transl Med. 2015;3:267.

- Friedman CF, Proverbs-Singh TA, Postow MA. Treatment of the immune-related adverse effects of immune checkpoint inhibitors a review. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2:1346-1353.

- Hua C, Boussemart L, Mateus C, et al. Association of vitiligo with tumor response in patients with metastatic melanoma treated with pembrolizumab. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:45-51.

- Hwang SJE, Carlos G, Chou S, et al. Bullous pemphigoid, an autoantibody-mediated disease, is a novel immune-related adverse event in patients treated with anti-programmed cell death 1 antibodies. Melanoma Res. 2016;26:413-416.

- Damsky W, Kole L, Tomayko MM. Development of bullous pemphigoid during nivolumab therapy. JAAD Case Rep. 2016;2:442-444.

- Garje R, Chau JJ, Chung J, et al. Acute flare of bullous pemphigus with pembrolizumab used for treatment of metastatic urothelial cancer. J Immunother. 2018;41:42-44.

- Ito M, Hoashi T, Endo Y, et al. Atypical pemphigus developed in a patient with urothelial carcinoma treated with nivolumab. J Dermatol. 2019;46:e90-e92.

- Chen W-S, Tetzlaff MT, Diwan H, et al. Suprabasal acantholytic dermatologic toxicities associated checkpoint inhibitor therapy: a spectrum of immune reactions from paraneoplastic pemphigus-like to Grover-like lesions. J Cutan Pathol. 2018;45:764-773.

- Muglia C, Bronsnick T, Kirkorian AY, et al. Questioning the specificity and sensitivity of ELISA for bullous pemphigoid diagnosis. Cutis. 2017;99:E27-E30.

Practice Points

- Anti–programmed cell death 1 (PD1) targeted therapies improve survival in solid and hematologic malignancies but are associated with autoimmune side effects, with bullous pemphigoid (BP) being the newest reported.

- Bullous pemphigoid can develop months into immunotherapy treatment.

- Bullous pemphigoid should be on the differential diagnosis in a patient who is on an anti-PD1 immune checkpoint inhibitor and develops 1 or more of the following: pruritus, dermatitis, and vesicles.

- Early diagnosis of BP is essential for keeping patients on immunotherapy because its severity often results in temporary or permanent discontinuation of treatment.