User login

Hemodialysis patient with finger ulcerations

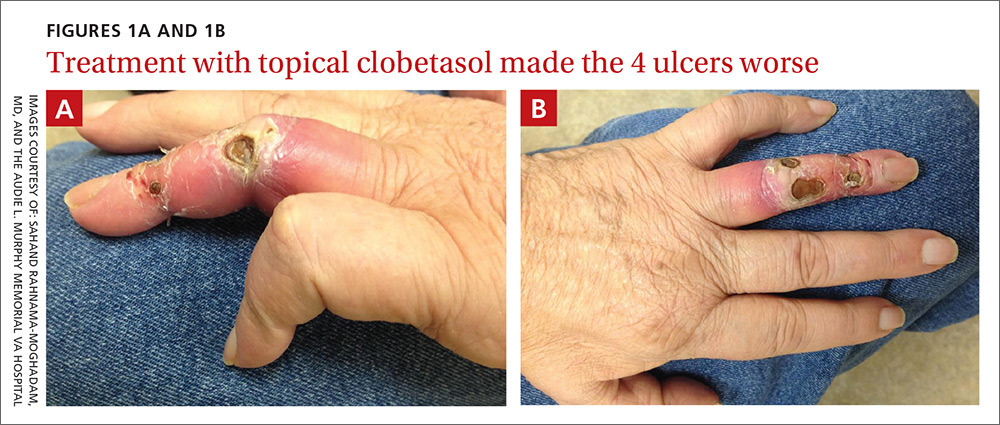

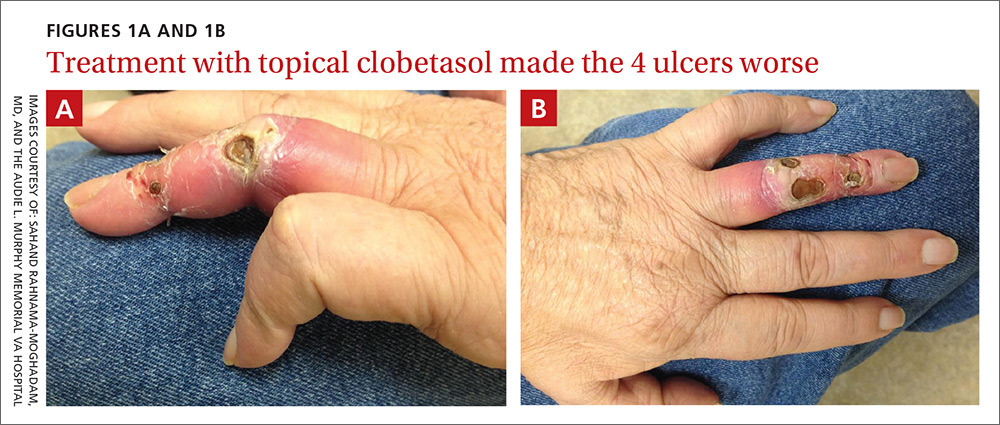

A 62-year-old man with end-stage renal disease presented to our dermatology clinic with 2-month-old ulcerations on his distal left ring finger. He was on hemodialysis and had a radiocephalic arteriovenous fistula (AVF) on his left arm. He had been empirically treated elsewhere with oral trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for a presumed bacterial infection, without improvement. He was then treated for contact dermatitis with topical clobetasol, which led to ulcer expansion and worsening pain.

At our clinic, the patient reported intermittent pain in his finger and paresthesias during activity and dialysis, but no tenderness of the ulcers. He had atrophy of the intrinsic left hand muscles (his non-dominant hand) with associated weakness. Three weeks earlier, he’d received a blood transfusion for anemia. Afterward, the pain in his hand improved and the ulcers decreased in size.

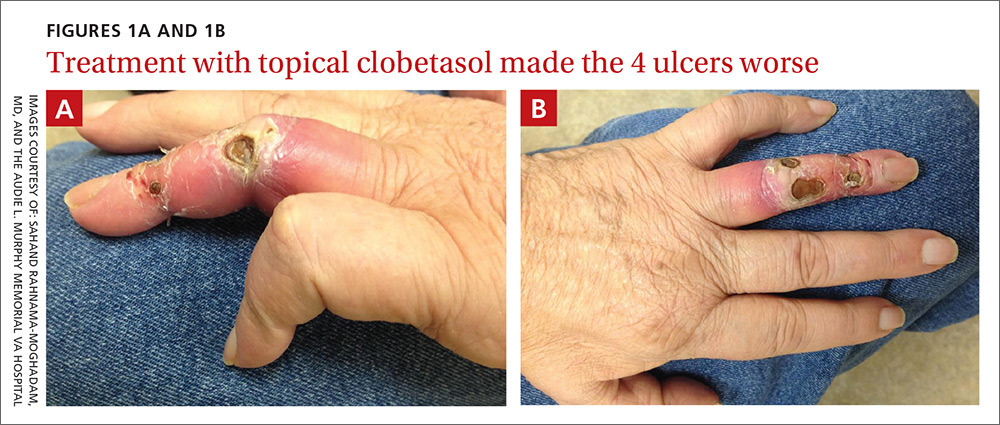

On exam, the AVF had a palpable thrill over the left forearm. The radial pulses were palpable bilaterally (2+) and the left ulnar artery was palpable, but diminished (1+). The patient’s left hand was cooler than the right (with a slight cyanotic hue and visible intrinsic muscle atrophy) and had decreased sensation to pain and temperature. Four ulcers with dry yellow eschar were located over the dorsal interphalangeal joints (FIGURES 1A AND 1B). They were essentially non-tender, but there was tenderness in the adjacent intact skin. There was violaceous blue edematous congestion noted on the fourth finger, and the distal phalange was constricted, giving it a “pseudoainhum” appearance.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Dialysis access steal syndrome

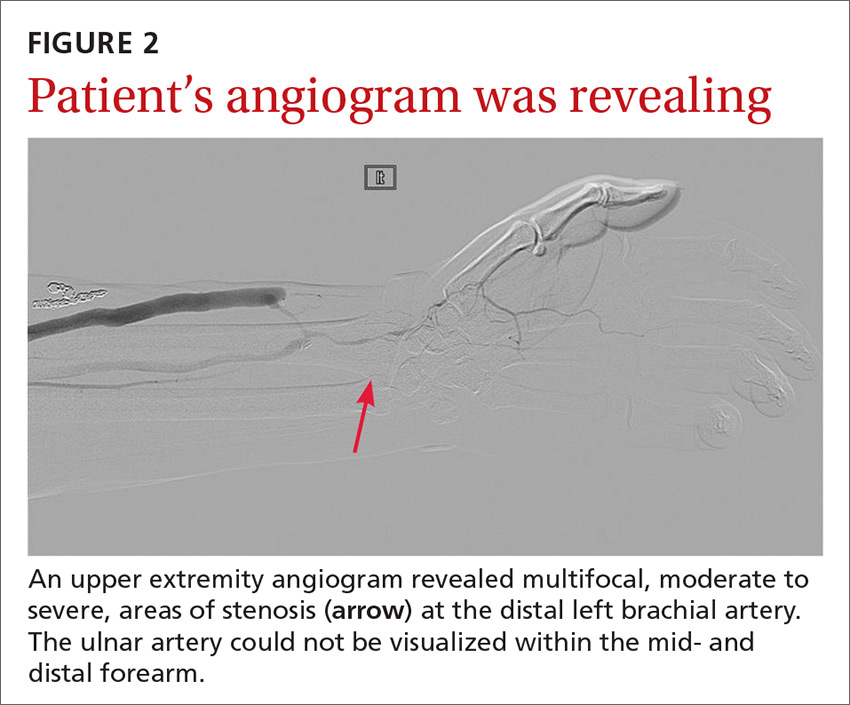

We suspected dialysis access steal syndrome (also known as AVF steal syndrome), so a duplex ultrasound was performed. The ultrasound was inconclusive. (We couldn’t confirm a limitation in blood flow, nor delineate anatomy.) So, we referred the patient for a thoracic and upper extremity angiogram.

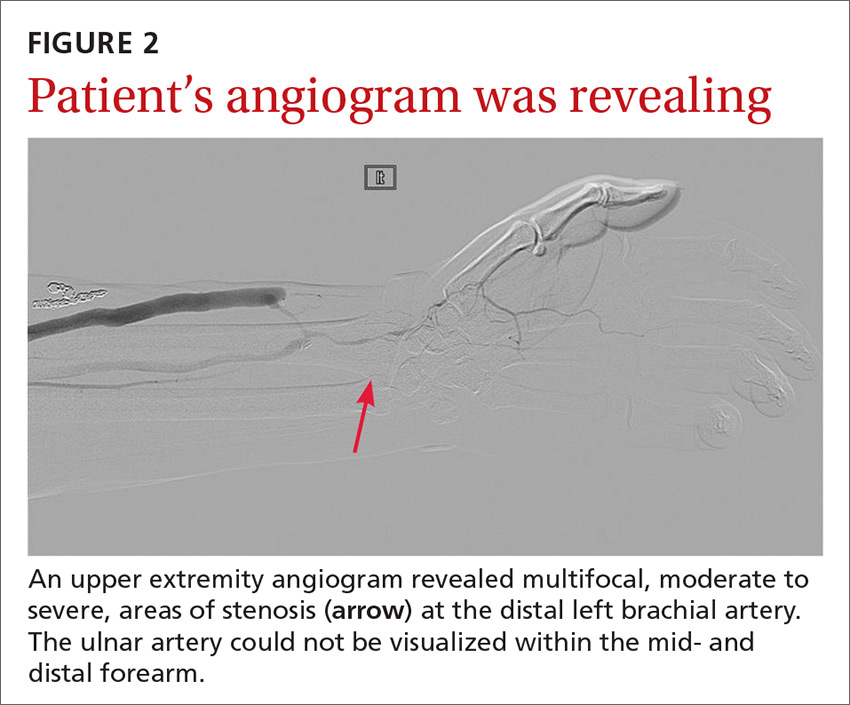

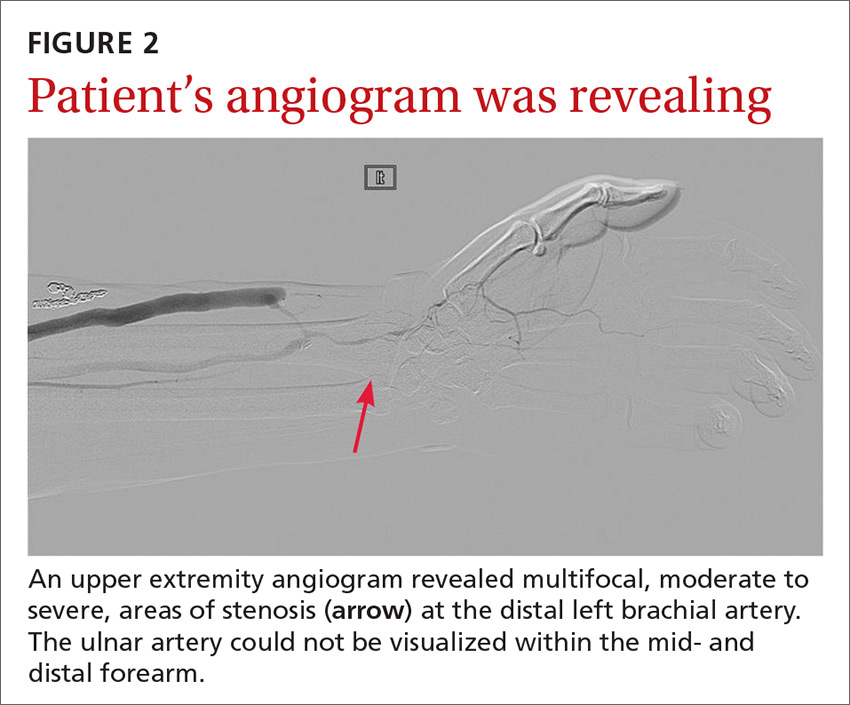

The angiogram demonstrated multifocal, moderate to severe, areas of stenosis at the distal left brachial artery. The radial artery was patent at the level of the wrist, but showed diffuse narrowing beyond the level of the arteriovenous (AV) anastomosis. There was only a faint palmar arch identified on the radial aspect of the hand with digital branches feeding the radial portion of the hand. In contrast, the ulnar artery was not seen within the mid- and distal forearm (FIGURE 2). Palmar branches to the ulnar half of the hand were not identified. The fistula itself didn’t show any stenosis.

Based on these findings, our suspicions of dialysis access steal syndrome were confirmed.

Dialysis access steal syndrome is caused by a significant decrease or reversal of blood flow in the arterial segment distal to the AVF or graft, which is induced by the low resistance of the fistula outflow. Patients with adequate collateral vasculature are able to compensate for the steal effect; however, patients with end-stage renal disease typically have preexisting vascular disease that increases the risk for vascular steal and, ultimately, demand ischemia after placement of an AVF.1 Interestingly, a steal effect occurs in 73% of patients after AVF construction, yet it is estimated that only 10% of patients demonstrating a steal phenomenon become symptomatic.2

In our patient’s case, the vaso-occlusive properties of topical steroids explain why the superpotent steroid (clobetasol) he was prescribed increased his pain and worsened the underlying problem.

A broad differential; a useful exam maneuver

The differential diagnosis of ulcers includes infection (mainly from bacterial or mycobacterial sources), trauma facilitated by neuropathy (neuropathic ulceration), vasculitis, and ischemia. When the history and physical exam suggest ischemic ulceration, then thromboembolism, thoracic outlet syndrome, vasculitis, atherosclerosis, and steal syndrome become more likely causes.

Signs and symptoms of ischemic steal syndrome are initially subtle and include extremity coolness, neurosensory changes, intrinsic muscle weakness, ulceration, and ultimately, gangrene of the affected extremity.3,4 A cold, numb, and/or painful hand during dialysis is another clue.3 Factors that increase the likelihood of the syndrome include age >60 years, female sex, and the presence of diabetes or peripheral artery disease.2,3,5,6

One physical exam maneuver that can help make the diagnosis of steal syndrome is manual occlusion of the AVF. If palpable distal pulses disappear when the AVF is patent and reappear when the fistula is occluded with downward pressure, then AVF steal syndrome is likely.4 Pain at rest, sensory loss, loss of pulse, and digital gangrene are emergency symptoms that warrant immediate surgical evaluation.3

Tests will confirm suspicions. Doppler ultrasound can be used to assess changes in the blood flow rate of the affected vessels when the AVF is patent vs when it is occluded. Similarly, pulse oximetry can be used with and without AVF occlusion to compare changes in oxygen saturation. The confirmatory diagnosis, however, is made via a fistulogram (angiography) with and without manual compression.6 Images taken after dye injection into the AVF show dramatic improvement of distal blood flow with AVF compression.

Treatment requires surgery

Severe steal-related ischemic manifestations that threaten the function and viability of digits require surgical treatment that is primarily directed toward improving distal blood flow and secondarily toward preserving hemodialysis access. Several surgical treatments are commonly used, including access ligation, banding, elongation, distal arterial ligation, and distal revascularization and interval ligation.2-5,7

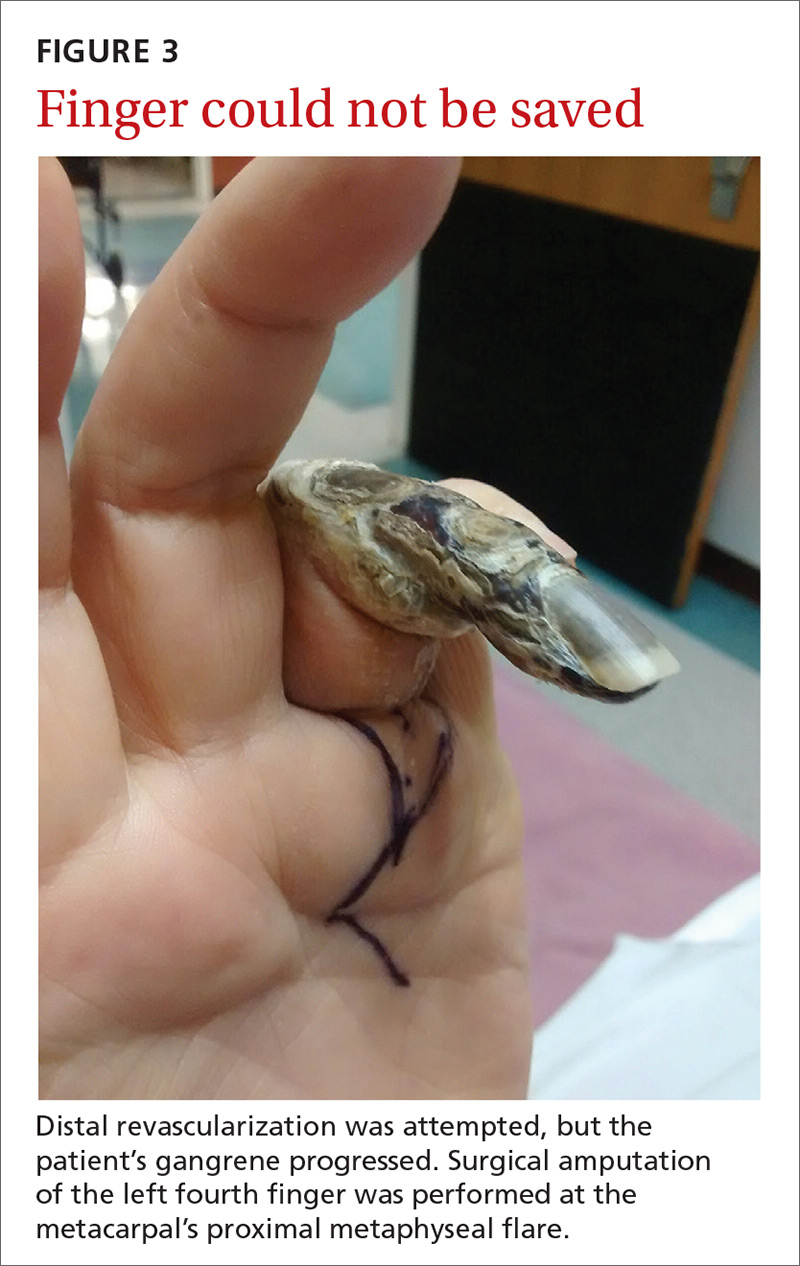

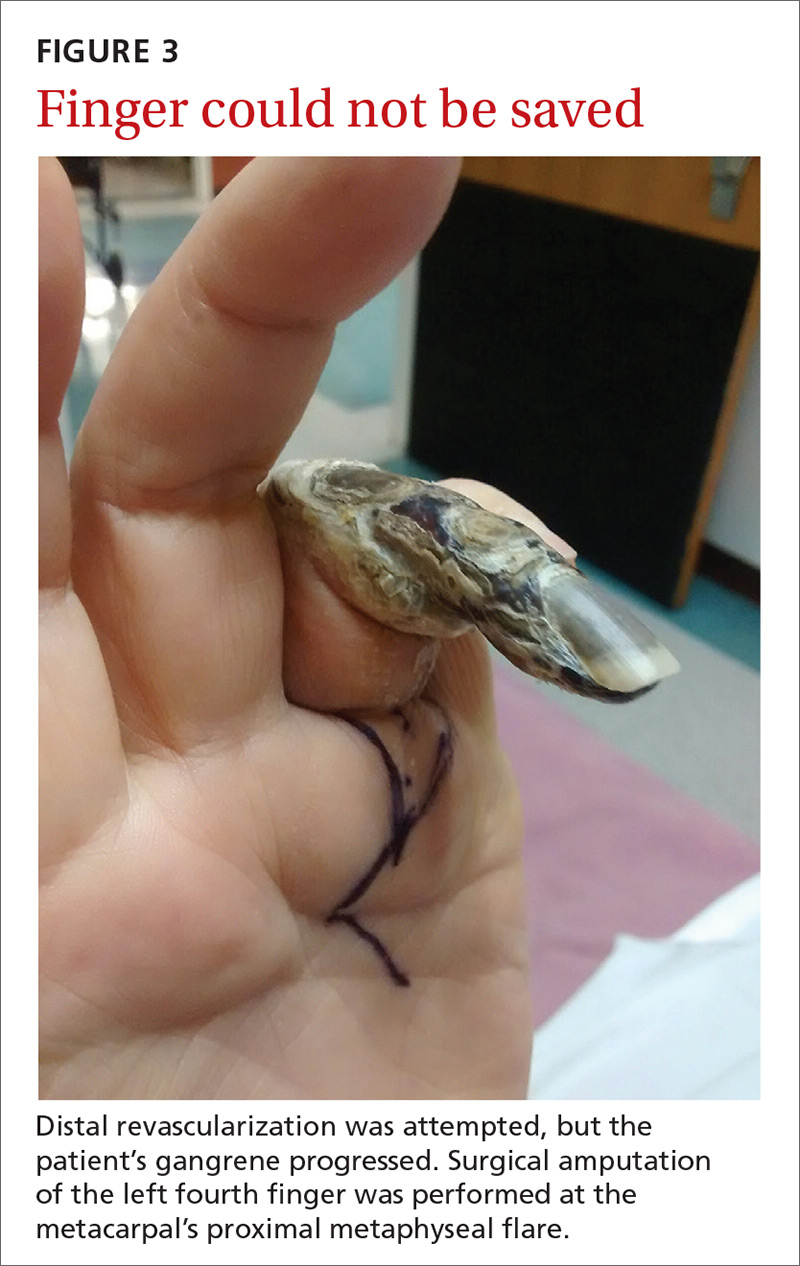

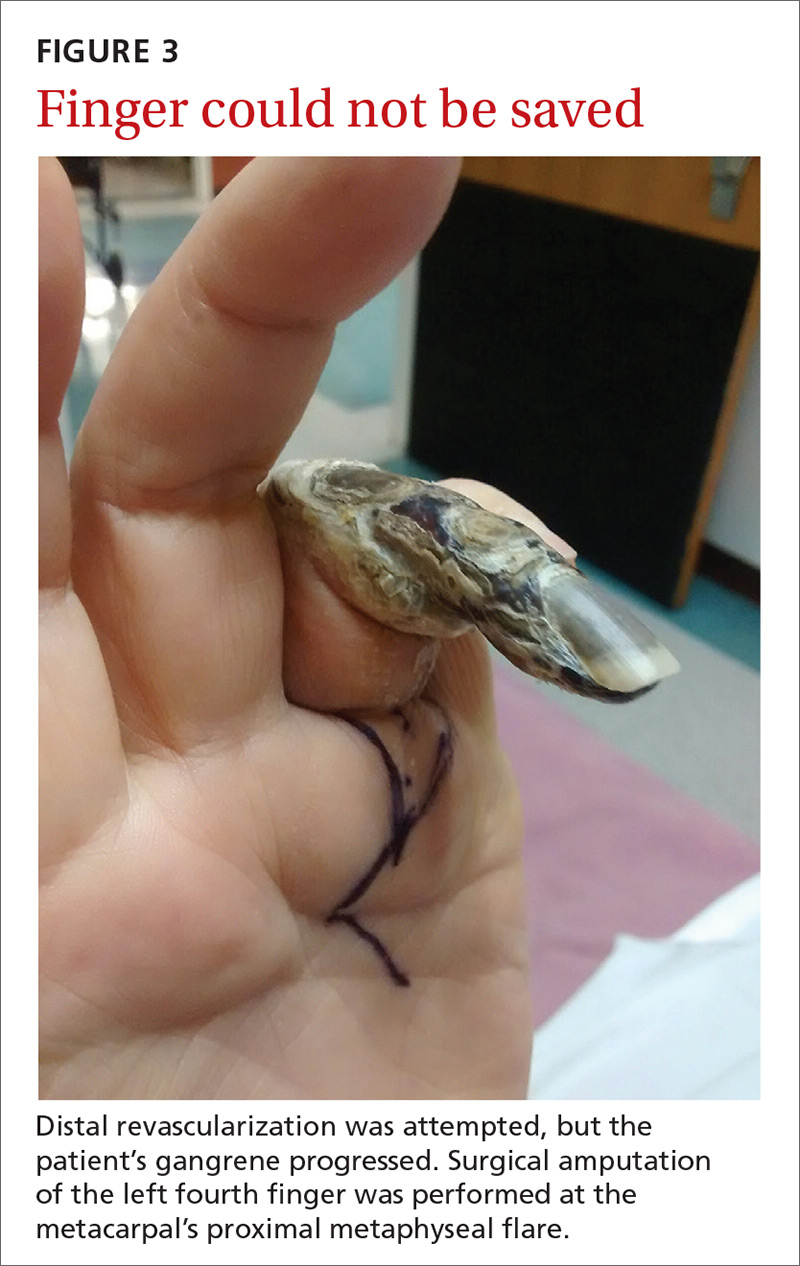

Our patient. Distal revascularization was attempted, but unfortunately, the patient’s gangrene was progressive (FIGURE 3) and surgical amputation of the left fourth finger was performed at the metacarpal’s proximal metaphyseal flare. The patient was transitioned to peritoneal dialysis to avoid further ischemia.

CORRESPONDENCE

Sahand Rahnama-Moghadam, MD, Department of Dermatology, Indiana University, 545 Barnhill Drive, Indianapolis, IN 46202; srahnama@iupui.edu.

1. Morsy AH, Kulbaski M, Chen C, et al. Incidence and characteristics of patients with hand ischemia after a hemodialysis access procedure. J Surg Res. 1998;74:8-10.

2. Puryear A, Villarreal S, Wells MJ, et al. JAAD grand rounds quiz. Hand ischemia in a hemodialysis patient. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:393-395.

3. Pelle MT, Miller OF 3rd. Dermatologic manifestations and management of vascular steal syndrome in hemodialysis patients with arteriovenous fistulas. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1296-1298.

4. Wixon CL, Hughes JD, Mills JL. Understanding strategies for the treatment of ischemic steal syndrome after hemodialysis access. J Am Coll Surg. 2000;191:301-310.

5. Gupta N, Yuo TH, Konig G 4th, et al. Treatment strategies of arterial steal after arteriovenous access. J Vasc Surg. 2011;54:162-167.

6. Zamani P, Kaufman J, Kinlay S. Ischemic steal syndrome following arm arteriovenous fistula for hemodialysis. Vasc Med. 2009;14:371-376.

7. Leake AE, Winger DG, Leers SA, et al. Management and outcomes of dialysis access-associated steal syndrome. J Vasc Surg. 2015;61:754-760.

A 62-year-old man with end-stage renal disease presented to our dermatology clinic with 2-month-old ulcerations on his distal left ring finger. He was on hemodialysis and had a radiocephalic arteriovenous fistula (AVF) on his left arm. He had been empirically treated elsewhere with oral trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for a presumed bacterial infection, without improvement. He was then treated for contact dermatitis with topical clobetasol, which led to ulcer expansion and worsening pain.

At our clinic, the patient reported intermittent pain in his finger and paresthesias during activity and dialysis, but no tenderness of the ulcers. He had atrophy of the intrinsic left hand muscles (his non-dominant hand) with associated weakness. Three weeks earlier, he’d received a blood transfusion for anemia. Afterward, the pain in his hand improved and the ulcers decreased in size.

On exam, the AVF had a palpable thrill over the left forearm. The radial pulses were palpable bilaterally (2+) and the left ulnar artery was palpable, but diminished (1+). The patient’s left hand was cooler than the right (with a slight cyanotic hue and visible intrinsic muscle atrophy) and had decreased sensation to pain and temperature. Four ulcers with dry yellow eschar were located over the dorsal interphalangeal joints (FIGURES 1A AND 1B). They were essentially non-tender, but there was tenderness in the adjacent intact skin. There was violaceous blue edematous congestion noted on the fourth finger, and the distal phalange was constricted, giving it a “pseudoainhum” appearance.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Dialysis access steal syndrome

We suspected dialysis access steal syndrome (also known as AVF steal syndrome), so a duplex ultrasound was performed. The ultrasound was inconclusive. (We couldn’t confirm a limitation in blood flow, nor delineate anatomy.) So, we referred the patient for a thoracic and upper extremity angiogram.

The angiogram demonstrated multifocal, moderate to severe, areas of stenosis at the distal left brachial artery. The radial artery was patent at the level of the wrist, but showed diffuse narrowing beyond the level of the arteriovenous (AV) anastomosis. There was only a faint palmar arch identified on the radial aspect of the hand with digital branches feeding the radial portion of the hand. In contrast, the ulnar artery was not seen within the mid- and distal forearm (FIGURE 2). Palmar branches to the ulnar half of the hand were not identified. The fistula itself didn’t show any stenosis.

Based on these findings, our suspicions of dialysis access steal syndrome were confirmed.

Dialysis access steal syndrome is caused by a significant decrease or reversal of blood flow in the arterial segment distal to the AVF or graft, which is induced by the low resistance of the fistula outflow. Patients with adequate collateral vasculature are able to compensate for the steal effect; however, patients with end-stage renal disease typically have preexisting vascular disease that increases the risk for vascular steal and, ultimately, demand ischemia after placement of an AVF.1 Interestingly, a steal effect occurs in 73% of patients after AVF construction, yet it is estimated that only 10% of patients demonstrating a steal phenomenon become symptomatic.2

In our patient’s case, the vaso-occlusive properties of topical steroids explain why the superpotent steroid (clobetasol) he was prescribed increased his pain and worsened the underlying problem.

A broad differential; a useful exam maneuver

The differential diagnosis of ulcers includes infection (mainly from bacterial or mycobacterial sources), trauma facilitated by neuropathy (neuropathic ulceration), vasculitis, and ischemia. When the history and physical exam suggest ischemic ulceration, then thromboembolism, thoracic outlet syndrome, vasculitis, atherosclerosis, and steal syndrome become more likely causes.

Signs and symptoms of ischemic steal syndrome are initially subtle and include extremity coolness, neurosensory changes, intrinsic muscle weakness, ulceration, and ultimately, gangrene of the affected extremity.3,4 A cold, numb, and/or painful hand during dialysis is another clue.3 Factors that increase the likelihood of the syndrome include age >60 years, female sex, and the presence of diabetes or peripheral artery disease.2,3,5,6

One physical exam maneuver that can help make the diagnosis of steal syndrome is manual occlusion of the AVF. If palpable distal pulses disappear when the AVF is patent and reappear when the fistula is occluded with downward pressure, then AVF steal syndrome is likely.4 Pain at rest, sensory loss, loss of pulse, and digital gangrene are emergency symptoms that warrant immediate surgical evaluation.3

Tests will confirm suspicions. Doppler ultrasound can be used to assess changes in the blood flow rate of the affected vessels when the AVF is patent vs when it is occluded. Similarly, pulse oximetry can be used with and without AVF occlusion to compare changes in oxygen saturation. The confirmatory diagnosis, however, is made via a fistulogram (angiography) with and without manual compression.6 Images taken after dye injection into the AVF show dramatic improvement of distal blood flow with AVF compression.

Treatment requires surgery

Severe steal-related ischemic manifestations that threaten the function and viability of digits require surgical treatment that is primarily directed toward improving distal blood flow and secondarily toward preserving hemodialysis access. Several surgical treatments are commonly used, including access ligation, banding, elongation, distal arterial ligation, and distal revascularization and interval ligation.2-5,7

Our patient. Distal revascularization was attempted, but unfortunately, the patient’s gangrene was progressive (FIGURE 3) and surgical amputation of the left fourth finger was performed at the metacarpal’s proximal metaphyseal flare. The patient was transitioned to peritoneal dialysis to avoid further ischemia.

CORRESPONDENCE

Sahand Rahnama-Moghadam, MD, Department of Dermatology, Indiana University, 545 Barnhill Drive, Indianapolis, IN 46202; srahnama@iupui.edu.

A 62-year-old man with end-stage renal disease presented to our dermatology clinic with 2-month-old ulcerations on his distal left ring finger. He was on hemodialysis and had a radiocephalic arteriovenous fistula (AVF) on his left arm. He had been empirically treated elsewhere with oral trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for a presumed bacterial infection, without improvement. He was then treated for contact dermatitis with topical clobetasol, which led to ulcer expansion and worsening pain.

At our clinic, the patient reported intermittent pain in his finger and paresthesias during activity and dialysis, but no tenderness of the ulcers. He had atrophy of the intrinsic left hand muscles (his non-dominant hand) with associated weakness. Three weeks earlier, he’d received a blood transfusion for anemia. Afterward, the pain in his hand improved and the ulcers decreased in size.

On exam, the AVF had a palpable thrill over the left forearm. The radial pulses were palpable bilaterally (2+) and the left ulnar artery was palpable, but diminished (1+). The patient’s left hand was cooler than the right (with a slight cyanotic hue and visible intrinsic muscle atrophy) and had decreased sensation to pain and temperature. Four ulcers with dry yellow eschar were located over the dorsal interphalangeal joints (FIGURES 1A AND 1B). They were essentially non-tender, but there was tenderness in the adjacent intact skin. There was violaceous blue edematous congestion noted on the fourth finger, and the distal phalange was constricted, giving it a “pseudoainhum” appearance.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Dialysis access steal syndrome

We suspected dialysis access steal syndrome (also known as AVF steal syndrome), so a duplex ultrasound was performed. The ultrasound was inconclusive. (We couldn’t confirm a limitation in blood flow, nor delineate anatomy.) So, we referred the patient for a thoracic and upper extremity angiogram.

The angiogram demonstrated multifocal, moderate to severe, areas of stenosis at the distal left brachial artery. The radial artery was patent at the level of the wrist, but showed diffuse narrowing beyond the level of the arteriovenous (AV) anastomosis. There was only a faint palmar arch identified on the radial aspect of the hand with digital branches feeding the radial portion of the hand. In contrast, the ulnar artery was not seen within the mid- and distal forearm (FIGURE 2). Palmar branches to the ulnar half of the hand were not identified. The fistula itself didn’t show any stenosis.

Based on these findings, our suspicions of dialysis access steal syndrome were confirmed.

Dialysis access steal syndrome is caused by a significant decrease or reversal of blood flow in the arterial segment distal to the AVF or graft, which is induced by the low resistance of the fistula outflow. Patients with adequate collateral vasculature are able to compensate for the steal effect; however, patients with end-stage renal disease typically have preexisting vascular disease that increases the risk for vascular steal and, ultimately, demand ischemia after placement of an AVF.1 Interestingly, a steal effect occurs in 73% of patients after AVF construction, yet it is estimated that only 10% of patients demonstrating a steal phenomenon become symptomatic.2

In our patient’s case, the vaso-occlusive properties of topical steroids explain why the superpotent steroid (clobetasol) he was prescribed increased his pain and worsened the underlying problem.

A broad differential; a useful exam maneuver

The differential diagnosis of ulcers includes infection (mainly from bacterial or mycobacterial sources), trauma facilitated by neuropathy (neuropathic ulceration), vasculitis, and ischemia. When the history and physical exam suggest ischemic ulceration, then thromboembolism, thoracic outlet syndrome, vasculitis, atherosclerosis, and steal syndrome become more likely causes.

Signs and symptoms of ischemic steal syndrome are initially subtle and include extremity coolness, neurosensory changes, intrinsic muscle weakness, ulceration, and ultimately, gangrene of the affected extremity.3,4 A cold, numb, and/or painful hand during dialysis is another clue.3 Factors that increase the likelihood of the syndrome include age >60 years, female sex, and the presence of diabetes or peripheral artery disease.2,3,5,6

One physical exam maneuver that can help make the diagnosis of steal syndrome is manual occlusion of the AVF. If palpable distal pulses disappear when the AVF is patent and reappear when the fistula is occluded with downward pressure, then AVF steal syndrome is likely.4 Pain at rest, sensory loss, loss of pulse, and digital gangrene are emergency symptoms that warrant immediate surgical evaluation.3

Tests will confirm suspicions. Doppler ultrasound can be used to assess changes in the blood flow rate of the affected vessels when the AVF is patent vs when it is occluded. Similarly, pulse oximetry can be used with and without AVF occlusion to compare changes in oxygen saturation. The confirmatory diagnosis, however, is made via a fistulogram (angiography) with and without manual compression.6 Images taken after dye injection into the AVF show dramatic improvement of distal blood flow with AVF compression.

Treatment requires surgery

Severe steal-related ischemic manifestations that threaten the function and viability of digits require surgical treatment that is primarily directed toward improving distal blood flow and secondarily toward preserving hemodialysis access. Several surgical treatments are commonly used, including access ligation, banding, elongation, distal arterial ligation, and distal revascularization and interval ligation.2-5,7

Our patient. Distal revascularization was attempted, but unfortunately, the patient’s gangrene was progressive (FIGURE 3) and surgical amputation of the left fourth finger was performed at the metacarpal’s proximal metaphyseal flare. The patient was transitioned to peritoneal dialysis to avoid further ischemia.

CORRESPONDENCE

Sahand Rahnama-Moghadam, MD, Department of Dermatology, Indiana University, 545 Barnhill Drive, Indianapolis, IN 46202; srahnama@iupui.edu.

1. Morsy AH, Kulbaski M, Chen C, et al. Incidence and characteristics of patients with hand ischemia after a hemodialysis access procedure. J Surg Res. 1998;74:8-10.

2. Puryear A, Villarreal S, Wells MJ, et al. JAAD grand rounds quiz. Hand ischemia in a hemodialysis patient. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:393-395.

3. Pelle MT, Miller OF 3rd. Dermatologic manifestations and management of vascular steal syndrome in hemodialysis patients with arteriovenous fistulas. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1296-1298.

4. Wixon CL, Hughes JD, Mills JL. Understanding strategies for the treatment of ischemic steal syndrome after hemodialysis access. J Am Coll Surg. 2000;191:301-310.

5. Gupta N, Yuo TH, Konig G 4th, et al. Treatment strategies of arterial steal after arteriovenous access. J Vasc Surg. 2011;54:162-167.

6. Zamani P, Kaufman J, Kinlay S. Ischemic steal syndrome following arm arteriovenous fistula for hemodialysis. Vasc Med. 2009;14:371-376.

7. Leake AE, Winger DG, Leers SA, et al. Management and outcomes of dialysis access-associated steal syndrome. J Vasc Surg. 2015;61:754-760.

1. Morsy AH, Kulbaski M, Chen C, et al. Incidence and characteristics of patients with hand ischemia after a hemodialysis access procedure. J Surg Res. 1998;74:8-10.

2. Puryear A, Villarreal S, Wells MJ, et al. JAAD grand rounds quiz. Hand ischemia in a hemodialysis patient. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:393-395.

3. Pelle MT, Miller OF 3rd. Dermatologic manifestations and management of vascular steal syndrome in hemodialysis patients with arteriovenous fistulas. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1296-1298.

4. Wixon CL, Hughes JD, Mills JL. Understanding strategies for the treatment of ischemic steal syndrome after hemodialysis access. J Am Coll Surg. 2000;191:301-310.

5. Gupta N, Yuo TH, Konig G 4th, et al. Treatment strategies of arterial steal after arteriovenous access. J Vasc Surg. 2011;54:162-167.

6. Zamani P, Kaufman J, Kinlay S. Ischemic steal syndrome following arm arteriovenous fistula for hemodialysis. Vasc Med. 2009;14:371-376.

7. Leake AE, Winger DG, Leers SA, et al. Management and outcomes of dialysis access-associated steal syndrome. J Vasc Surg. 2015;61:754-760.

Vesicular eruption in a 2-year-old boy

A 2-year-old boy with atopic dermatitis developed a flare of his eczema after having a bath with mint-scented soap. His mother treated the flare with over-the-counter topical hydrocortisone cream. Two to 3 days later, he developed grouped vesicles on the right side of his neck. Three days after that, he developed a painful generalized vesicular eruption all over his body.

The boy was admitted to a hospital for supportive care and empiric antibiotics, but was discharged when no bacterial infection was found. The patient’s mother was instructed to follow up with his primary care provider in the next 2 weeks.

Three days after his hospitalization, the eruption on the young boy’s body spread and he was uncomfortable. He was brought to our hospital’s pediatric clinic, where physicians examined him and decided to transfer him to the university hospital for further evaluation.

On exam, the boy was afebrile, but uncomfortable and irritable. Diffuse heme-crusted and punched-out erosions covered about 90% of his body (FIGURE). His mucous membranes were not involved. Underneath the heme-crusted erosions, there were lichenified pink plaques on the antecubital fossae, popliteal fossae, periocular face, and buttocks. The patient’s right dorsal foot had a small vesicle; all other vesicles on his body had crusted over.

The patient’s family indicated that the child had received the varicella vaccine without incident at 12 months of age. He had no history of travel, no contact with sick individuals, and no exposure to pets or other animals.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Eczema herpeticum

Eczema herpeticum (EH) was suspected based on the appearance of the lesions. A Tzanck smear came back positive for multinucleated giant cells and a herpes simplex virus (HSV) amplified probe came back positive for HSV-1—confirming the diagnosis.

EH—also known as Kaposi varicelliform eruption—is a superficial generalized viral infection (typically caused by HSV-1; HSV-2 is less common). The infection commonly occurs in patients with underlying atopic dermatitis, but may also occur in those with Darier disease, pemphigus, burns, and other conditions that disrupt the skin barrier. Other viruses, such as Coxsackie virus, can also cause EH. Eczema vaccinatum is a variant that may occur after smallpox vaccination.1 EH occurs more often in infants and children than in adults,2 and is a potentially life-threatening dermatologic emergency.

Who’s at risk? Patients with underlying chronic skin conditions such as eczema may have impaired cell-mediated immunity, making them more susceptible to a viral infection like EH.1 In addition, treatment of underlying chronic skin conditions with immunosuppressive therapies often increases susceptibility to superimposed infection.1 (In this case, the patient’s parents had treated an eczema flare with a topical hydrocortisone cream.) Lastly, increased risk may be associated with mutations in the gene encoding filaggrin.2

Areas affected. EH typically appears in areas of pre-existing dermatitis as monomorphic, discrete, 2- to 3-mm, punched-out, heme-crusted erosions with scalloped borders.2 The erosions initially appear as vesicles or pustules, which may appear concurrently with the erosions. The erosions can coalesce to form larger lesions.3 Fever, malaise, and lymphadenopathy may also be present.2,3

4 factors differentiate EH from other conditions

The differential for eczema herpeticum includes impetigo, bullous impetigo, shingles, chicken pox, scabies, pustular psoriasis, bullous pemphigoid, drug hypersensitivity reactions, and exacerbation of a primary dermatosis or skin condition.1,4

EH may be differentiated from these by its location, its development in the setting of pre-existing dermatitis, its response to antiviral medications, and the results of laboratory testing. Because of the vast differential, physicians must maintain a high index of suspicion for EH, particularly when a patient with a pre-existing skin condition presents with acute onset cutaneous pain.3

Perform a Tzanck smear to diagnose the underlying infection

If EH is suspected, treatment must be initiated immediately.3 (In our patient’s case, he was started on intravenous acyclovir 10 mg/kg every 8 hours.)

Once treatment is underway, a Tzanck smear of the vesicle base can be performed at the patient’s bedside to narrow the cause of the infection to HSV or varicella zoster virus (VZV). Multinucleated giant keratinocytes (as in our patient’s case) are diagnostic for one of the herpes viruses; concurrent inflammatory cells are also to be expected in an inflammatory skin condition but by themselves are not diagnostic of herpes.

If available in the laboratory, direct fluorescent antibody testing can differentiate between HSV and VZV. Alternatively, a nucleic acid amplified probe test may be used to provide a quick and specific result. The most specific test is a viral culture, but it lacks sensitivity and usually requires 2 to 5 daysfor results.2 A bacterial skin swab and blood culture should also be considered to direct antibiotic therapy if superinfection has occurred.

Antivirals and antibiotics should be given until lesions heal

Patients with EH should be admitted to the hospital for at least 24 to 48 hours of intravenous acyclovir.4 Antivirals—oral or intravenous—should be given for 10 to 14 days or until all mucocutaneous lesions are healed. Recommended dosing for acyclovir is 15 mg/kg (up to 400 mg) by mouth 3 to 5 times per day or, if severe, 5 mg/kg (if ≥12 years of age) to 10 mg/kg (if <12 years of age) intravenously every 8 hours.2 Patients should also receive a 3- to 6-month suppressive course of oral acyclovir, valacyclovir, or famciclovir.4

Intravenous antibiotics should also be considered, pending the results of bacterial skin swabs and a blood culture, as the skin of patients with atopic dermatitis is colonized with staphylococcus 90% of the time.4

Potential complications. Bacterial sepsis resulting from superinfection and disseminated HSV, although extremely rare, is the main cause of death associated with EH.3 One case in the literature described a 43-year-old woman with extensive EH superimposed on atopic dermatitis, disseminated HSV, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa septicemia. Despite treatment with intravenous acyclovir and antibiotics in a burn center intensive care unit, the patient experienced septic shock and disseminated intravascular coagulation with progression to multiorgan failure and death.3

Our patient’s antiviral regimen was transitioned to a 14-day course of oral acyclovir, which he completed. Topical steroids and an immunosuppressant (tacrolimus ointment) were applied concurrently. He was subsequently prescribed a 6-month suppressive course of acyclovir and was scheduled for follow-up at an outpatient dermatology clinic to discuss resuming therapy for atopic dermatitis.

CORRESPONDENCE

Sahand Rahnama-Moghadam, MD, 7323 Snowden Road #1205, San Antonio, TX 78240; rahnamamogha@uthscsa.edu.

1. Studdiford JS, Valko GP, Belin LJ, et al. Eczema herpeticum: making the diagnosis in the emergency department. J Emerg Med. 2011;40:167-169.

2. Mendoza N, Madkan V, Sra K, et al. Human herpesviruses. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, et al, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:1321-1343.

3. Mackool BT, Goverman J, Nazarian RM. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Case 14-2012. A 43-year-old woman with fever and a generalized rash. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1825-1834.

4. Kress DW. Pediatric dermatology emergencies. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2011;23:403-406.

A 2-year-old boy with atopic dermatitis developed a flare of his eczema after having a bath with mint-scented soap. His mother treated the flare with over-the-counter topical hydrocortisone cream. Two to 3 days later, he developed grouped vesicles on the right side of his neck. Three days after that, he developed a painful generalized vesicular eruption all over his body.

The boy was admitted to a hospital for supportive care and empiric antibiotics, but was discharged when no bacterial infection was found. The patient’s mother was instructed to follow up with his primary care provider in the next 2 weeks.

Three days after his hospitalization, the eruption on the young boy’s body spread and he was uncomfortable. He was brought to our hospital’s pediatric clinic, where physicians examined him and decided to transfer him to the university hospital for further evaluation.

On exam, the boy was afebrile, but uncomfortable and irritable. Diffuse heme-crusted and punched-out erosions covered about 90% of his body (FIGURE). His mucous membranes were not involved. Underneath the heme-crusted erosions, there were lichenified pink plaques on the antecubital fossae, popliteal fossae, periocular face, and buttocks. The patient’s right dorsal foot had a small vesicle; all other vesicles on his body had crusted over.

The patient’s family indicated that the child had received the varicella vaccine without incident at 12 months of age. He had no history of travel, no contact with sick individuals, and no exposure to pets or other animals.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Eczema herpeticum

Eczema herpeticum (EH) was suspected based on the appearance of the lesions. A Tzanck smear came back positive for multinucleated giant cells and a herpes simplex virus (HSV) amplified probe came back positive for HSV-1—confirming the diagnosis.

EH—also known as Kaposi varicelliform eruption—is a superficial generalized viral infection (typically caused by HSV-1; HSV-2 is less common). The infection commonly occurs in patients with underlying atopic dermatitis, but may also occur in those with Darier disease, pemphigus, burns, and other conditions that disrupt the skin barrier. Other viruses, such as Coxsackie virus, can also cause EH. Eczema vaccinatum is a variant that may occur after smallpox vaccination.1 EH occurs more often in infants and children than in adults,2 and is a potentially life-threatening dermatologic emergency.

Who’s at risk? Patients with underlying chronic skin conditions such as eczema may have impaired cell-mediated immunity, making them more susceptible to a viral infection like EH.1 In addition, treatment of underlying chronic skin conditions with immunosuppressive therapies often increases susceptibility to superimposed infection.1 (In this case, the patient’s parents had treated an eczema flare with a topical hydrocortisone cream.) Lastly, increased risk may be associated with mutations in the gene encoding filaggrin.2

Areas affected. EH typically appears in areas of pre-existing dermatitis as monomorphic, discrete, 2- to 3-mm, punched-out, heme-crusted erosions with scalloped borders.2 The erosions initially appear as vesicles or pustules, which may appear concurrently with the erosions. The erosions can coalesce to form larger lesions.3 Fever, malaise, and lymphadenopathy may also be present.2,3

4 factors differentiate EH from other conditions

The differential for eczema herpeticum includes impetigo, bullous impetigo, shingles, chicken pox, scabies, pustular psoriasis, bullous pemphigoid, drug hypersensitivity reactions, and exacerbation of a primary dermatosis or skin condition.1,4

EH may be differentiated from these by its location, its development in the setting of pre-existing dermatitis, its response to antiviral medications, and the results of laboratory testing. Because of the vast differential, physicians must maintain a high index of suspicion for EH, particularly when a patient with a pre-existing skin condition presents with acute onset cutaneous pain.3

Perform a Tzanck smear to diagnose the underlying infection

If EH is suspected, treatment must be initiated immediately.3 (In our patient’s case, he was started on intravenous acyclovir 10 mg/kg every 8 hours.)

Once treatment is underway, a Tzanck smear of the vesicle base can be performed at the patient’s bedside to narrow the cause of the infection to HSV or varicella zoster virus (VZV). Multinucleated giant keratinocytes (as in our patient’s case) are diagnostic for one of the herpes viruses; concurrent inflammatory cells are also to be expected in an inflammatory skin condition but by themselves are not diagnostic of herpes.

If available in the laboratory, direct fluorescent antibody testing can differentiate between HSV and VZV. Alternatively, a nucleic acid amplified probe test may be used to provide a quick and specific result. The most specific test is a viral culture, but it lacks sensitivity and usually requires 2 to 5 daysfor results.2 A bacterial skin swab and blood culture should also be considered to direct antibiotic therapy if superinfection has occurred.

Antivirals and antibiotics should be given until lesions heal

Patients with EH should be admitted to the hospital for at least 24 to 48 hours of intravenous acyclovir.4 Antivirals—oral or intravenous—should be given for 10 to 14 days or until all mucocutaneous lesions are healed. Recommended dosing for acyclovir is 15 mg/kg (up to 400 mg) by mouth 3 to 5 times per day or, if severe, 5 mg/kg (if ≥12 years of age) to 10 mg/kg (if <12 years of age) intravenously every 8 hours.2 Patients should also receive a 3- to 6-month suppressive course of oral acyclovir, valacyclovir, or famciclovir.4

Intravenous antibiotics should also be considered, pending the results of bacterial skin swabs and a blood culture, as the skin of patients with atopic dermatitis is colonized with staphylococcus 90% of the time.4

Potential complications. Bacterial sepsis resulting from superinfection and disseminated HSV, although extremely rare, is the main cause of death associated with EH.3 One case in the literature described a 43-year-old woman with extensive EH superimposed on atopic dermatitis, disseminated HSV, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa septicemia. Despite treatment with intravenous acyclovir and antibiotics in a burn center intensive care unit, the patient experienced septic shock and disseminated intravascular coagulation with progression to multiorgan failure and death.3

Our patient’s antiviral regimen was transitioned to a 14-day course of oral acyclovir, which he completed. Topical steroids and an immunosuppressant (tacrolimus ointment) were applied concurrently. He was subsequently prescribed a 6-month suppressive course of acyclovir and was scheduled for follow-up at an outpatient dermatology clinic to discuss resuming therapy for atopic dermatitis.

CORRESPONDENCE

Sahand Rahnama-Moghadam, MD, 7323 Snowden Road #1205, San Antonio, TX 78240; rahnamamogha@uthscsa.edu.

A 2-year-old boy with atopic dermatitis developed a flare of his eczema after having a bath with mint-scented soap. His mother treated the flare with over-the-counter topical hydrocortisone cream. Two to 3 days later, he developed grouped vesicles on the right side of his neck. Three days after that, he developed a painful generalized vesicular eruption all over his body.

The boy was admitted to a hospital for supportive care and empiric antibiotics, but was discharged when no bacterial infection was found. The patient’s mother was instructed to follow up with his primary care provider in the next 2 weeks.

Three days after his hospitalization, the eruption on the young boy’s body spread and he was uncomfortable. He was brought to our hospital’s pediatric clinic, where physicians examined him and decided to transfer him to the university hospital for further evaluation.

On exam, the boy was afebrile, but uncomfortable and irritable. Diffuse heme-crusted and punched-out erosions covered about 90% of his body (FIGURE). His mucous membranes were not involved. Underneath the heme-crusted erosions, there were lichenified pink plaques on the antecubital fossae, popliteal fossae, periocular face, and buttocks. The patient’s right dorsal foot had a small vesicle; all other vesicles on his body had crusted over.

The patient’s family indicated that the child had received the varicella vaccine without incident at 12 months of age. He had no history of travel, no contact with sick individuals, and no exposure to pets or other animals.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Eczema herpeticum

Eczema herpeticum (EH) was suspected based on the appearance of the lesions. A Tzanck smear came back positive for multinucleated giant cells and a herpes simplex virus (HSV) amplified probe came back positive for HSV-1—confirming the diagnosis.

EH—also known as Kaposi varicelliform eruption—is a superficial generalized viral infection (typically caused by HSV-1; HSV-2 is less common). The infection commonly occurs in patients with underlying atopic dermatitis, but may also occur in those with Darier disease, pemphigus, burns, and other conditions that disrupt the skin barrier. Other viruses, such as Coxsackie virus, can also cause EH. Eczema vaccinatum is a variant that may occur after smallpox vaccination.1 EH occurs more often in infants and children than in adults,2 and is a potentially life-threatening dermatologic emergency.

Who’s at risk? Patients with underlying chronic skin conditions such as eczema may have impaired cell-mediated immunity, making them more susceptible to a viral infection like EH.1 In addition, treatment of underlying chronic skin conditions with immunosuppressive therapies often increases susceptibility to superimposed infection.1 (In this case, the patient’s parents had treated an eczema flare with a topical hydrocortisone cream.) Lastly, increased risk may be associated with mutations in the gene encoding filaggrin.2

Areas affected. EH typically appears in areas of pre-existing dermatitis as monomorphic, discrete, 2- to 3-mm, punched-out, heme-crusted erosions with scalloped borders.2 The erosions initially appear as vesicles or pustules, which may appear concurrently with the erosions. The erosions can coalesce to form larger lesions.3 Fever, malaise, and lymphadenopathy may also be present.2,3

4 factors differentiate EH from other conditions

The differential for eczema herpeticum includes impetigo, bullous impetigo, shingles, chicken pox, scabies, pustular psoriasis, bullous pemphigoid, drug hypersensitivity reactions, and exacerbation of a primary dermatosis or skin condition.1,4

EH may be differentiated from these by its location, its development in the setting of pre-existing dermatitis, its response to antiviral medications, and the results of laboratory testing. Because of the vast differential, physicians must maintain a high index of suspicion for EH, particularly when a patient with a pre-existing skin condition presents with acute onset cutaneous pain.3

Perform a Tzanck smear to diagnose the underlying infection

If EH is suspected, treatment must be initiated immediately.3 (In our patient’s case, he was started on intravenous acyclovir 10 mg/kg every 8 hours.)

Once treatment is underway, a Tzanck smear of the vesicle base can be performed at the patient’s bedside to narrow the cause of the infection to HSV or varicella zoster virus (VZV). Multinucleated giant keratinocytes (as in our patient’s case) are diagnostic for one of the herpes viruses; concurrent inflammatory cells are also to be expected in an inflammatory skin condition but by themselves are not diagnostic of herpes.

If available in the laboratory, direct fluorescent antibody testing can differentiate between HSV and VZV. Alternatively, a nucleic acid amplified probe test may be used to provide a quick and specific result. The most specific test is a viral culture, but it lacks sensitivity and usually requires 2 to 5 daysfor results.2 A bacterial skin swab and blood culture should also be considered to direct antibiotic therapy if superinfection has occurred.

Antivirals and antibiotics should be given until lesions heal

Patients with EH should be admitted to the hospital for at least 24 to 48 hours of intravenous acyclovir.4 Antivirals—oral or intravenous—should be given for 10 to 14 days or until all mucocutaneous lesions are healed. Recommended dosing for acyclovir is 15 mg/kg (up to 400 mg) by mouth 3 to 5 times per day or, if severe, 5 mg/kg (if ≥12 years of age) to 10 mg/kg (if <12 years of age) intravenously every 8 hours.2 Patients should also receive a 3- to 6-month suppressive course of oral acyclovir, valacyclovir, or famciclovir.4

Intravenous antibiotics should also be considered, pending the results of bacterial skin swabs and a blood culture, as the skin of patients with atopic dermatitis is colonized with staphylococcus 90% of the time.4

Potential complications. Bacterial sepsis resulting from superinfection and disseminated HSV, although extremely rare, is the main cause of death associated with EH.3 One case in the literature described a 43-year-old woman with extensive EH superimposed on atopic dermatitis, disseminated HSV, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa septicemia. Despite treatment with intravenous acyclovir and antibiotics in a burn center intensive care unit, the patient experienced septic shock and disseminated intravascular coagulation with progression to multiorgan failure and death.3

Our patient’s antiviral regimen was transitioned to a 14-day course of oral acyclovir, which he completed. Topical steroids and an immunosuppressant (tacrolimus ointment) were applied concurrently. He was subsequently prescribed a 6-month suppressive course of acyclovir and was scheduled for follow-up at an outpatient dermatology clinic to discuss resuming therapy for atopic dermatitis.

CORRESPONDENCE

Sahand Rahnama-Moghadam, MD, 7323 Snowden Road #1205, San Antonio, TX 78240; rahnamamogha@uthscsa.edu.

1. Studdiford JS, Valko GP, Belin LJ, et al. Eczema herpeticum: making the diagnosis in the emergency department. J Emerg Med. 2011;40:167-169.

2. Mendoza N, Madkan V, Sra K, et al. Human herpesviruses. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, et al, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:1321-1343.

3. Mackool BT, Goverman J, Nazarian RM. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Case 14-2012. A 43-year-old woman with fever and a generalized rash. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1825-1834.

4. Kress DW. Pediatric dermatology emergencies. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2011;23:403-406.

1. Studdiford JS, Valko GP, Belin LJ, et al. Eczema herpeticum: making the diagnosis in the emergency department. J Emerg Med. 2011;40:167-169.

2. Mendoza N, Madkan V, Sra K, et al. Human herpesviruses. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, et al, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:1321-1343.

3. Mackool BT, Goverman J, Nazarian RM. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Case 14-2012. A 43-year-old woman with fever and a generalized rash. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1825-1834.

4. Kress DW. Pediatric dermatology emergencies. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2011;23:403-406.

Generalized rash follows ankle ulceration

A 31-year-old incarcerated man sought care for one crusted ulcer and one adjacent open ulcer with granulation tissue on his left malleolus. The ulcers were caused by chronic venous insufficiency—the result of previous trauma to the ankle. Concerned that the ulcers would become infected, the physician prescribed one double-strength tablet twice a day of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX). The patient took 2 doses of the antibiotic and one dose of naproxen.

When the patient awoke the next morning, he had a generalized skin eruption on his chin, trunk, buttocks, glans penis, and extremities (FIGURE). The rash began as red edematous plaques that became itchy and painful with dark, violaceous dusky centers surrounded by redness. The patient was treated with topical hydrocortisone 2.5% twice a day and oral diphenhydramine 25 mg followed by 50 mg, but the rash didn’t improve.

The patient was transported to the local emergency department where physicians noted that the patient had about 30 to 40 well-demarcated papules and plaques of various sizes that were haphazardly located over the patient’s chin, chest, back, upper and lower extremities, and genitalia. There was one lesion on the chest with central vesiculation. There were no lesions on the mucous membranes of his eyes, ears, nose, mouth, or anus.

The patient, whose vital signs were within normal limits, was empirically treated with one dose of methylprednisolone (125 mg intravenous [IV]) and started on IV piperacillin-tazobactam and vancomycin. Lab work revealed no elevation in his white blood cell count, creatinine, liver function enzymes, or C-reactive protein.

The patient subsequently revealed that he’d had a similar experience a year earlier after being treated with TMP-SMX for cellulitis. He noted that during the previous episode, the lesions were located on the exact same areas of his glans penis and chin.

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Disseminated fixed-drug eruption

The diagnosis was based on the morphologic characteristics of the eruption and the patient’s history of similar lesions that appeared in the exact same initial locations (chin and glans penis) following previous treatment with TMP-SMX.

A fixed-drug eruption is an adverse cutaneous reaction to a drug that is defined by a dusky red or violaceous macule, which evolves into a patch, and eventually, an edematous plaque. Fixed-drug eruptions are typically solitary, but may be generalized (as was the case with our patient).

The pathophysiology of the disease involves resident intra-epidermal CD8+ T-cells resembling effector memory T-cells. These T-cells are increased in number at the dermoepidermal junction of normal appearing skin; their aberrant activation leads to an inflammatory response, stimulating tissue destruction and formation of the classic fixed-drug lesion.1

The diagnosis is usually made based on a history of similar lesions recurring at the same location in response to a specific drug2 and the classic physical exam findings of well-demarcated, edematous, and violaceous plaques. To confirm a fixed-drug eruption in the case of clinical equipoise, a skin biopsy may be performed.

Classic histologic findings of a fixed-drug eruption include:

- band-like lichenoid lymphocytic infiltrates with vacuolar changes at the dermoepidermal junction,

- mixed cellular infiltrates, including eosinophils, throughout the dermis and occasional superficial and deep mixed cellular perivascular infiltrates, and

- abundant melanophages suggesting pigment incontinence.

There are several reports of similar TMP-SMX–induced generalized fixed-drug eruptions in the literature.3 One study of 64 cases of fixed-drug eruption found that TMP-SMX was the most common offender, causing 75% of fixed-drug eruption cases; naproxen sodium came in second with 12.5%.3 Other common culprits include the antipyretic metamizole and other pyrazolone derivatives such as tetracycline, metronidazole, ciprofloxacin, and phenytoin sodium.4 There is evidence supporting a correlation between the offending drug and the subsequent site of reaction; TMP-SMX is associated with mucosal junction and genital involvement.4,5 This finding may aid physicians in the investigation of provoking agents.

Distinguish fixed-drug eruptions from serious bullous diseases

Fixed-drug eruptions occasionally exhibit bullae and erosions and must be differentiated from more serious generalized bullous diseases, including Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN). The differential diagnosis also includes erythema multiforme, early bullous drug eruption, and bullous arthropod assault, which may leave similar hyperpigmented patches. Fixed-drug eruptions can be distinguished by the lack of simultaneous involvement of 2 mucosal surfaces, lack of generalized desquamation, and normal vital signs and lab values, including white blood cell count and erythrocyte sedimentation rate/C-reactive protein.

A subset of fixed-drug eruption, generalized bullous fixed-drug eruption (which has been defined as blistering on >10% of the body’s surface area at 3 different anatomic sites), may be particularly hard to distinguish from SJS and TEN. Generalized bullous fixed-drug eruption generally has a shorter latency period than SJS or TEN (usually <3 days compared to 7-10 days) and has less mucosal involvement.6

Symptomatic therapy includes antihistamines, glucocorticoid ointment

Management of a disseminated fixed-drug eruption requires a thorough history to identify the causative agent (including over-the-counter drugs, herbals, topicals, and eye drops). Most patients are asymptomatic, but some (like our patient) are symptomatic and experience generalized pruritus, cutaneous burning, and/or pain. Symptomatic therapy includes oral antihistamines and potent topical glucocorticoid ointment for non-eroded lesions. Additionally, if not medically contraindicated, oral steroids may be used for generalized or extremely painful mucosal lesions at a dose of 0.5 mg/kg daily for 3 to 5 days. Be advised, however, that these therapies are based on case report level data.2

Local wound care of eroded lesions includes keeping the site moist with a bland emollient and bandaging. The inciting agent must be added to the patient’s allergy list and avoided in the future. In equivocal cases, it is prudent to admit the patient for observation to ensure that the eruption is not a nascent SJS or TEN eruption.

Our patient was admitted to the observation unit overnight to monitor for the appearance of systemic symptoms and to assess the evolution of the rash for further mucosal involvement that could have indicated SJS. Upon reassessment the next day, his older lesions had evolved into vesiculated and necrotic areas as per the natural history of severe fixed-drug eruption.

He was prescribed prednisone 40 mg/d for 3 days to help with local inflammation, pain, and itching. TMP-SMX was added to his allergy list and he was given local wound care instructions. He was told to return if he developed any systemic symptoms.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jackie Bucher, MD, 7733 Louis Pasteur Drive Apt. 209, San Antonio, TX 78229; bucher@uthscsa.edu.

1. Shiohara T. Fixed drug eruption: pathogenesis and diagnostic tests. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;9:316-321.

2. Wolff K, Johnson RA. Dermatology and internal medicine: fixed drug eruption. In: Wolff K, Johnson RA, Saavedra AP, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Color Atlas and Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology. 6th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2009:566-568.

3. Ozkaya-Bayazit E, Bayazit H, Ozarmagan G. Drug related clinical pattern in fixed drug eruption. Eur J Dermatol. 2000;10:288-291.

4. Sharma VK, Dhar S, Gill AN. Drug related involvement of specific sites in fixed eruptions: a statistical evaluation. J Dermatol. 1996;23:530-534.

5. Thankappan TP, Zachariah J. Drug-specific clinical pattern in fixed drug eruptions. Int J Dermatol. 1991;30:867-870.

6. Cho YT, Lin JW, Chen YC, et al. Generalized bullous fixed drug eruption is distinct from Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis by immunohistopathological features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:539-548.

A 31-year-old incarcerated man sought care for one crusted ulcer and one adjacent open ulcer with granulation tissue on his left malleolus. The ulcers were caused by chronic venous insufficiency—the result of previous trauma to the ankle. Concerned that the ulcers would become infected, the physician prescribed one double-strength tablet twice a day of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX). The patient took 2 doses of the antibiotic and one dose of naproxen.

When the patient awoke the next morning, he had a generalized skin eruption on his chin, trunk, buttocks, glans penis, and extremities (FIGURE). The rash began as red edematous plaques that became itchy and painful with dark, violaceous dusky centers surrounded by redness. The patient was treated with topical hydrocortisone 2.5% twice a day and oral diphenhydramine 25 mg followed by 50 mg, but the rash didn’t improve.

The patient was transported to the local emergency department where physicians noted that the patient had about 30 to 40 well-demarcated papules and plaques of various sizes that were haphazardly located over the patient’s chin, chest, back, upper and lower extremities, and genitalia. There was one lesion on the chest with central vesiculation. There were no lesions on the mucous membranes of his eyes, ears, nose, mouth, or anus.

The patient, whose vital signs were within normal limits, was empirically treated with one dose of methylprednisolone (125 mg intravenous [IV]) and started on IV piperacillin-tazobactam and vancomycin. Lab work revealed no elevation in his white blood cell count, creatinine, liver function enzymes, or C-reactive protein.

The patient subsequently revealed that he’d had a similar experience a year earlier after being treated with TMP-SMX for cellulitis. He noted that during the previous episode, the lesions were located on the exact same areas of his glans penis and chin.

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Disseminated fixed-drug eruption

The diagnosis was based on the morphologic characteristics of the eruption and the patient’s history of similar lesions that appeared in the exact same initial locations (chin and glans penis) following previous treatment with TMP-SMX.

A fixed-drug eruption is an adverse cutaneous reaction to a drug that is defined by a dusky red or violaceous macule, which evolves into a patch, and eventually, an edematous plaque. Fixed-drug eruptions are typically solitary, but may be generalized (as was the case with our patient).

The pathophysiology of the disease involves resident intra-epidermal CD8+ T-cells resembling effector memory T-cells. These T-cells are increased in number at the dermoepidermal junction of normal appearing skin; their aberrant activation leads to an inflammatory response, stimulating tissue destruction and formation of the classic fixed-drug lesion.1

The diagnosis is usually made based on a history of similar lesions recurring at the same location in response to a specific drug2 and the classic physical exam findings of well-demarcated, edematous, and violaceous plaques. To confirm a fixed-drug eruption in the case of clinical equipoise, a skin biopsy may be performed.

Classic histologic findings of a fixed-drug eruption include:

- band-like lichenoid lymphocytic infiltrates with vacuolar changes at the dermoepidermal junction,

- mixed cellular infiltrates, including eosinophils, throughout the dermis and occasional superficial and deep mixed cellular perivascular infiltrates, and

- abundant melanophages suggesting pigment incontinence.

There are several reports of similar TMP-SMX–induced generalized fixed-drug eruptions in the literature.3 One study of 64 cases of fixed-drug eruption found that TMP-SMX was the most common offender, causing 75% of fixed-drug eruption cases; naproxen sodium came in second with 12.5%.3 Other common culprits include the antipyretic metamizole and other pyrazolone derivatives such as tetracycline, metronidazole, ciprofloxacin, and phenytoin sodium.4 There is evidence supporting a correlation between the offending drug and the subsequent site of reaction; TMP-SMX is associated with mucosal junction and genital involvement.4,5 This finding may aid physicians in the investigation of provoking agents.

Distinguish fixed-drug eruptions from serious bullous diseases

Fixed-drug eruptions occasionally exhibit bullae and erosions and must be differentiated from more serious generalized bullous diseases, including Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN). The differential diagnosis also includes erythema multiforme, early bullous drug eruption, and bullous arthropod assault, which may leave similar hyperpigmented patches. Fixed-drug eruptions can be distinguished by the lack of simultaneous involvement of 2 mucosal surfaces, lack of generalized desquamation, and normal vital signs and lab values, including white blood cell count and erythrocyte sedimentation rate/C-reactive protein.

A subset of fixed-drug eruption, generalized bullous fixed-drug eruption (which has been defined as blistering on >10% of the body’s surface area at 3 different anatomic sites), may be particularly hard to distinguish from SJS and TEN. Generalized bullous fixed-drug eruption generally has a shorter latency period than SJS or TEN (usually <3 days compared to 7-10 days) and has less mucosal involvement.6

Symptomatic therapy includes antihistamines, glucocorticoid ointment

Management of a disseminated fixed-drug eruption requires a thorough history to identify the causative agent (including over-the-counter drugs, herbals, topicals, and eye drops). Most patients are asymptomatic, but some (like our patient) are symptomatic and experience generalized pruritus, cutaneous burning, and/or pain. Symptomatic therapy includes oral antihistamines and potent topical glucocorticoid ointment for non-eroded lesions. Additionally, if not medically contraindicated, oral steroids may be used for generalized or extremely painful mucosal lesions at a dose of 0.5 mg/kg daily for 3 to 5 days. Be advised, however, that these therapies are based on case report level data.2

Local wound care of eroded lesions includes keeping the site moist with a bland emollient and bandaging. The inciting agent must be added to the patient’s allergy list and avoided in the future. In equivocal cases, it is prudent to admit the patient for observation to ensure that the eruption is not a nascent SJS or TEN eruption.

Our patient was admitted to the observation unit overnight to monitor for the appearance of systemic symptoms and to assess the evolution of the rash for further mucosal involvement that could have indicated SJS. Upon reassessment the next day, his older lesions had evolved into vesiculated and necrotic areas as per the natural history of severe fixed-drug eruption.

He was prescribed prednisone 40 mg/d for 3 days to help with local inflammation, pain, and itching. TMP-SMX was added to his allergy list and he was given local wound care instructions. He was told to return if he developed any systemic symptoms.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jackie Bucher, MD, 7733 Louis Pasteur Drive Apt. 209, San Antonio, TX 78229; bucher@uthscsa.edu.

A 31-year-old incarcerated man sought care for one crusted ulcer and one adjacent open ulcer with granulation tissue on his left malleolus. The ulcers were caused by chronic venous insufficiency—the result of previous trauma to the ankle. Concerned that the ulcers would become infected, the physician prescribed one double-strength tablet twice a day of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX). The patient took 2 doses of the antibiotic and one dose of naproxen.

When the patient awoke the next morning, he had a generalized skin eruption on his chin, trunk, buttocks, glans penis, and extremities (FIGURE). The rash began as red edematous plaques that became itchy and painful with dark, violaceous dusky centers surrounded by redness. The patient was treated with topical hydrocortisone 2.5% twice a day and oral diphenhydramine 25 mg followed by 50 mg, but the rash didn’t improve.

The patient was transported to the local emergency department where physicians noted that the patient had about 30 to 40 well-demarcated papules and plaques of various sizes that were haphazardly located over the patient’s chin, chest, back, upper and lower extremities, and genitalia. There was one lesion on the chest with central vesiculation. There were no lesions on the mucous membranes of his eyes, ears, nose, mouth, or anus.

The patient, whose vital signs were within normal limits, was empirically treated with one dose of methylprednisolone (125 mg intravenous [IV]) and started on IV piperacillin-tazobactam and vancomycin. Lab work revealed no elevation in his white blood cell count, creatinine, liver function enzymes, or C-reactive protein.

The patient subsequently revealed that he’d had a similar experience a year earlier after being treated with TMP-SMX for cellulitis. He noted that during the previous episode, the lesions were located on the exact same areas of his glans penis and chin.

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Disseminated fixed-drug eruption

The diagnosis was based on the morphologic characteristics of the eruption and the patient’s history of similar lesions that appeared in the exact same initial locations (chin and glans penis) following previous treatment with TMP-SMX.

A fixed-drug eruption is an adverse cutaneous reaction to a drug that is defined by a dusky red or violaceous macule, which evolves into a patch, and eventually, an edematous plaque. Fixed-drug eruptions are typically solitary, but may be generalized (as was the case with our patient).

The pathophysiology of the disease involves resident intra-epidermal CD8+ T-cells resembling effector memory T-cells. These T-cells are increased in number at the dermoepidermal junction of normal appearing skin; their aberrant activation leads to an inflammatory response, stimulating tissue destruction and formation of the classic fixed-drug lesion.1

The diagnosis is usually made based on a history of similar lesions recurring at the same location in response to a specific drug2 and the classic physical exam findings of well-demarcated, edematous, and violaceous plaques. To confirm a fixed-drug eruption in the case of clinical equipoise, a skin biopsy may be performed.

Classic histologic findings of a fixed-drug eruption include:

- band-like lichenoid lymphocytic infiltrates with vacuolar changes at the dermoepidermal junction,

- mixed cellular infiltrates, including eosinophils, throughout the dermis and occasional superficial and deep mixed cellular perivascular infiltrates, and

- abundant melanophages suggesting pigment incontinence.

There are several reports of similar TMP-SMX–induced generalized fixed-drug eruptions in the literature.3 One study of 64 cases of fixed-drug eruption found that TMP-SMX was the most common offender, causing 75% of fixed-drug eruption cases; naproxen sodium came in second with 12.5%.3 Other common culprits include the antipyretic metamizole and other pyrazolone derivatives such as tetracycline, metronidazole, ciprofloxacin, and phenytoin sodium.4 There is evidence supporting a correlation between the offending drug and the subsequent site of reaction; TMP-SMX is associated with mucosal junction and genital involvement.4,5 This finding may aid physicians in the investigation of provoking agents.

Distinguish fixed-drug eruptions from serious bullous diseases

Fixed-drug eruptions occasionally exhibit bullae and erosions and must be differentiated from more serious generalized bullous diseases, including Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN). The differential diagnosis also includes erythema multiforme, early bullous drug eruption, and bullous arthropod assault, which may leave similar hyperpigmented patches. Fixed-drug eruptions can be distinguished by the lack of simultaneous involvement of 2 mucosal surfaces, lack of generalized desquamation, and normal vital signs and lab values, including white blood cell count and erythrocyte sedimentation rate/C-reactive protein.

A subset of fixed-drug eruption, generalized bullous fixed-drug eruption (which has been defined as blistering on >10% of the body’s surface area at 3 different anatomic sites), may be particularly hard to distinguish from SJS and TEN. Generalized bullous fixed-drug eruption generally has a shorter latency period than SJS or TEN (usually <3 days compared to 7-10 days) and has less mucosal involvement.6

Symptomatic therapy includes antihistamines, glucocorticoid ointment

Management of a disseminated fixed-drug eruption requires a thorough history to identify the causative agent (including over-the-counter drugs, herbals, topicals, and eye drops). Most patients are asymptomatic, but some (like our patient) are symptomatic and experience generalized pruritus, cutaneous burning, and/or pain. Symptomatic therapy includes oral antihistamines and potent topical glucocorticoid ointment for non-eroded lesions. Additionally, if not medically contraindicated, oral steroids may be used for generalized or extremely painful mucosal lesions at a dose of 0.5 mg/kg daily for 3 to 5 days. Be advised, however, that these therapies are based on case report level data.2

Local wound care of eroded lesions includes keeping the site moist with a bland emollient and bandaging. The inciting agent must be added to the patient’s allergy list and avoided in the future. In equivocal cases, it is prudent to admit the patient for observation to ensure that the eruption is not a nascent SJS or TEN eruption.

Our patient was admitted to the observation unit overnight to monitor for the appearance of systemic symptoms and to assess the evolution of the rash for further mucosal involvement that could have indicated SJS. Upon reassessment the next day, his older lesions had evolved into vesiculated and necrotic areas as per the natural history of severe fixed-drug eruption.

He was prescribed prednisone 40 mg/d for 3 days to help with local inflammation, pain, and itching. TMP-SMX was added to his allergy list and he was given local wound care instructions. He was told to return if he developed any systemic symptoms.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jackie Bucher, MD, 7733 Louis Pasteur Drive Apt. 209, San Antonio, TX 78229; bucher@uthscsa.edu.

1. Shiohara T. Fixed drug eruption: pathogenesis and diagnostic tests. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;9:316-321.

2. Wolff K, Johnson RA. Dermatology and internal medicine: fixed drug eruption. In: Wolff K, Johnson RA, Saavedra AP, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Color Atlas and Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology. 6th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2009:566-568.

3. Ozkaya-Bayazit E, Bayazit H, Ozarmagan G. Drug related clinical pattern in fixed drug eruption. Eur J Dermatol. 2000;10:288-291.

4. Sharma VK, Dhar S, Gill AN. Drug related involvement of specific sites in fixed eruptions: a statistical evaluation. J Dermatol. 1996;23:530-534.

5. Thankappan TP, Zachariah J. Drug-specific clinical pattern in fixed drug eruptions. Int J Dermatol. 1991;30:867-870.

6. Cho YT, Lin JW, Chen YC, et al. Generalized bullous fixed drug eruption is distinct from Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis by immunohistopathological features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:539-548.

1. Shiohara T. Fixed drug eruption: pathogenesis and diagnostic tests. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;9:316-321.

2. Wolff K, Johnson RA. Dermatology and internal medicine: fixed drug eruption. In: Wolff K, Johnson RA, Saavedra AP, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Color Atlas and Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology. 6th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2009:566-568.

3. Ozkaya-Bayazit E, Bayazit H, Ozarmagan G. Drug related clinical pattern in fixed drug eruption. Eur J Dermatol. 2000;10:288-291.

4. Sharma VK, Dhar S, Gill AN. Drug related involvement of specific sites in fixed eruptions: a statistical evaluation. J Dermatol. 1996;23:530-534.

5. Thankappan TP, Zachariah J. Drug-specific clinical pattern in fixed drug eruptions. Int J Dermatol. 1991;30:867-870.

6. Cho YT, Lin JW, Chen YC, et al. Generalized bullous fixed drug eruption is distinct from Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis by immunohistopathological features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:539-548.