User login

Numerous large nodules on scalp

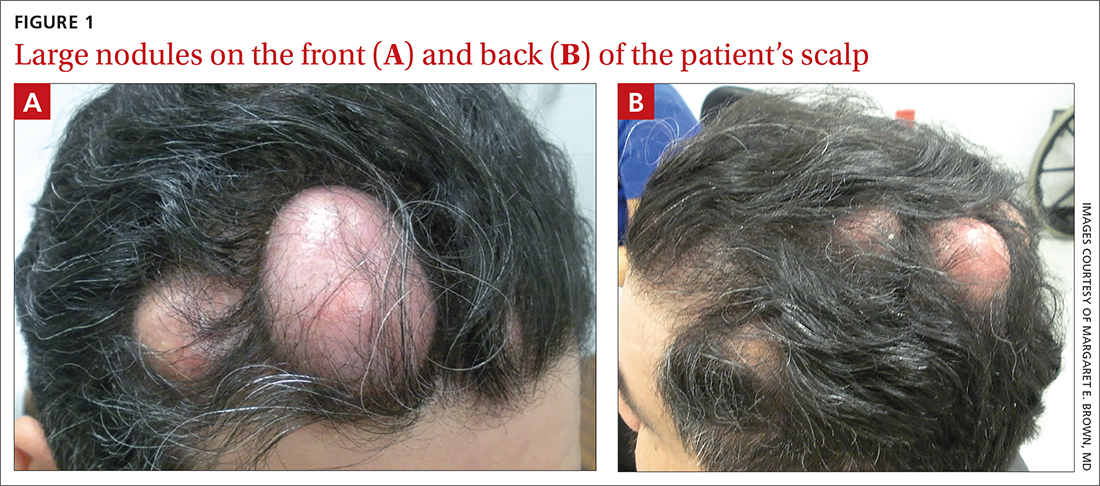

A 31-year-old Hispanic man presented for evaluation of numerous disfiguring growths on his scalp. They first appeared when he was 19 years old. A review of his family history revealed that his father had 2 “cysts” on his body.

The patient had 10 nodules on his scalp and upper back (Figures 1A and 1B). The ones on his scalp lacked puncta and appeared in a “turban tumor” configuration. The lesions were pink, smooth, and semisoft, and ranged in size from 1 to 6 cm.

Six years earlier, the patient had been seen for evaluation of 20 protuberant nodules. At the time, he had been referred to plastic surgery, where 15 lesions were excised. No other treatment was reported by the patient during the 6-year gap between exams.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Pilar cysts

Pilar cysts (PC), also known as trichilemma cysts, wen, or isthmus-catagen cysts, are benign cysts that manifest as smooth, firm, well-circumscribed, pink nodules. PCs originate from the follicular isthmus of the hair’s external root sheath1 and are found in 5% to 10% of the US population.2 Possible sites of appearance include the face, neck, trunk, and extremities, although 90% of PCs develop on the scalp.1 They tend to have an autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance with linkages to the short arm of chromosome 3.3 PCs can occasionally become inflamed following infection or trauma.

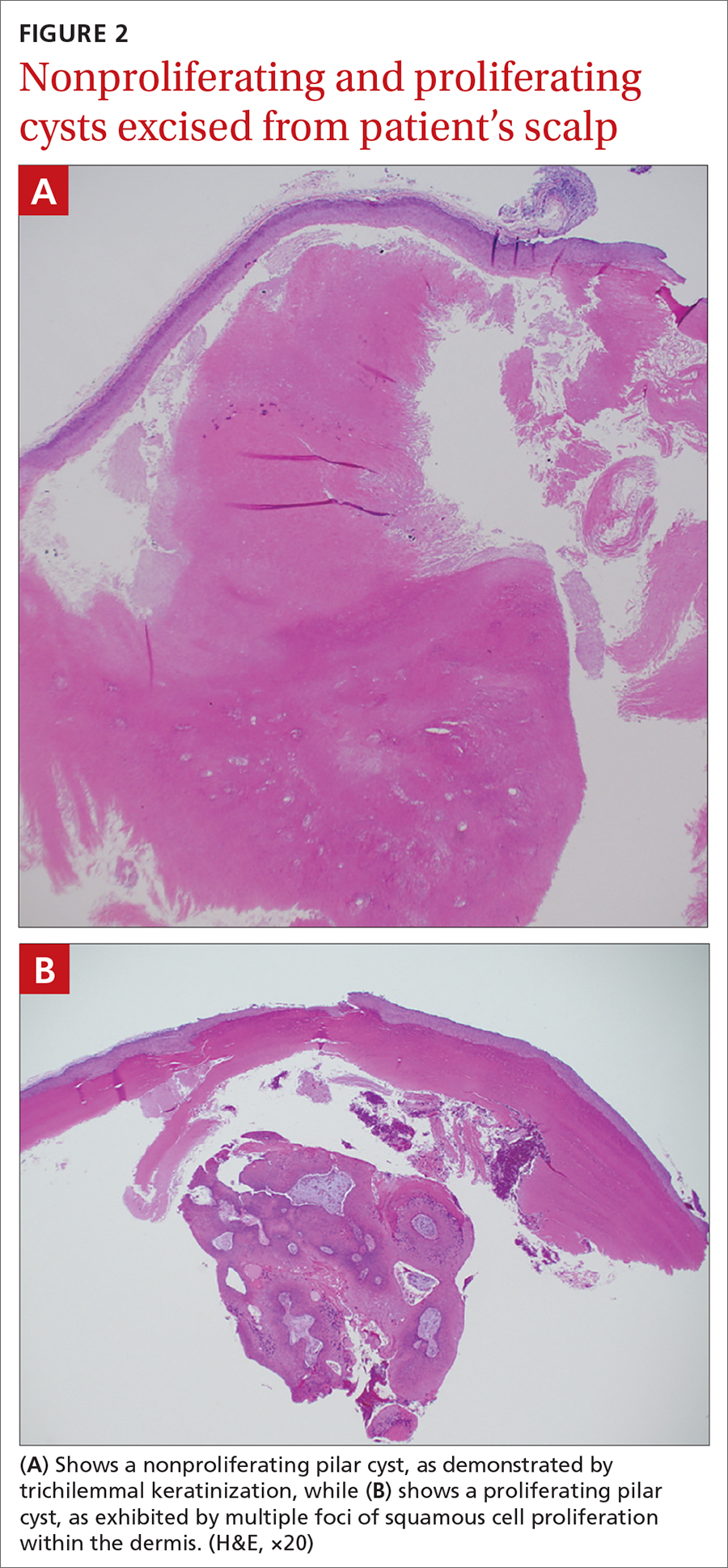

Characteristic histology of PCs demonstrates semisolid, keratin-filled, subepidermal cysts lined by stratified epithelium without a granular layer (trichilemmal keratinization). Lesions excised from this patient’s scalp showed 2 subtypes of PCs: nonproliferating (FIGURE 2A) and proliferating (FIGURE 2B). Subtypes appear similar on exam but can be differentiated on histology.

With gradual growth, proliferating PCs can reach up to 25 cm in diameter.1 Rapid growth, size > 5 cm, infiltration, or a non-scalp location may indicate malignancy.4

Differential diagnosis includes lipomas

The differential diagnosis for a lesion such as this includes epidermal inclusion cysts, dermoid cysts, and lipomas. Epidermal inclusion cysts have a punctum, whereas PCs do not. Dermoid cysts are single congenital lesions that manifest much earlier than PCs. Lipomas are easily movable rubbery bulges that appear more frequently in lipid-dense areas of the body.

For this patient, the striking turban tumor–like presentation, with numerous large cysts on the scalp, initially inspired a differential diagnosis including several genetic tumor syndromes. However, unlike the association between Gardner syndrome and numerous epidermoid cysts or Brooke-Spiegler syndrome and spiradenomas, no syndromes have been linked to numerous trichilemmal cysts.

Continue to: Excision is effective

Excision is effective

Excision is the treatment of choice for both proliferating and nonproliferating PCs.5 The local recurrence rate of proliferating PCs is 3.7% with a rare likelihood of transformation to trichilemmal carcinoma.6

Our patient continues to be followed in clinic for monitoring and periodic excision of bothersome cysts.

1. Ramaswamy AS, Manjunatha HK, Sunilkumar B, et al. Morphological spectrum of pilar cysts. N Am J Med Sci. 2013;5:124-128. http://doi.org/10.4103/1947-2714.107532

2. Ibrahim AE, Barikian A, Janom H, et al. Numerous recurrent trichilemmal cysts of the scalp: differential diagnosis and surgical management. J Craniofac Surg. 2012;23:e164-168. http://doi.org/10.1097/SCS.0b013e31824cdbd2

3. Adya KA, Inamadar AC, Palit A. Multiple firm mobile swellings over the scalp. Int J Trichology. 2012;4:98-99. http://doi.org/10.4103/0974-7753.96906

4. Folpe AL, Reisenauer AK, Mentzel T, et al. Proliferating trichilemmal tumors: clinicopathologic evaluation is a guide to biologic behavior. J Cutan Pathol. 2003;30:492-498. http://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0560.2003.00041.x

5. Leppard BJ, Sanderson KV. The natural history of trichilemmal cysts. Br J Dermatol. 1976;94:379-390. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2133.1976.tb06115.x

6. Kim UG, Kook DB, Kim TH, et al. Trichilemmal carcinoma from proliferating trichilemmal cyst on the posterior neck. Arch Craniofac Surg. 2017;18:50-53. http://doi.org/10.7181/acfs.2017.18.1.50

A 31-year-old Hispanic man presented for evaluation of numerous disfiguring growths on his scalp. They first appeared when he was 19 years old. A review of his family history revealed that his father had 2 “cysts” on his body.

The patient had 10 nodules on his scalp and upper back (Figures 1A and 1B). The ones on his scalp lacked puncta and appeared in a “turban tumor” configuration. The lesions were pink, smooth, and semisoft, and ranged in size from 1 to 6 cm.

Six years earlier, the patient had been seen for evaluation of 20 protuberant nodules. At the time, he had been referred to plastic surgery, where 15 lesions were excised. No other treatment was reported by the patient during the 6-year gap between exams.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Pilar cysts

Pilar cysts (PC), also known as trichilemma cysts, wen, or isthmus-catagen cysts, are benign cysts that manifest as smooth, firm, well-circumscribed, pink nodules. PCs originate from the follicular isthmus of the hair’s external root sheath1 and are found in 5% to 10% of the US population.2 Possible sites of appearance include the face, neck, trunk, and extremities, although 90% of PCs develop on the scalp.1 They tend to have an autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance with linkages to the short arm of chromosome 3.3 PCs can occasionally become inflamed following infection or trauma.

Characteristic histology of PCs demonstrates semisolid, keratin-filled, subepidermal cysts lined by stratified epithelium without a granular layer (trichilemmal keratinization). Lesions excised from this patient’s scalp showed 2 subtypes of PCs: nonproliferating (FIGURE 2A) and proliferating (FIGURE 2B). Subtypes appear similar on exam but can be differentiated on histology.

With gradual growth, proliferating PCs can reach up to 25 cm in diameter.1 Rapid growth, size > 5 cm, infiltration, or a non-scalp location may indicate malignancy.4

Differential diagnosis includes lipomas

The differential diagnosis for a lesion such as this includes epidermal inclusion cysts, dermoid cysts, and lipomas. Epidermal inclusion cysts have a punctum, whereas PCs do not. Dermoid cysts are single congenital lesions that manifest much earlier than PCs. Lipomas are easily movable rubbery bulges that appear more frequently in lipid-dense areas of the body.

For this patient, the striking turban tumor–like presentation, with numerous large cysts on the scalp, initially inspired a differential diagnosis including several genetic tumor syndromes. However, unlike the association between Gardner syndrome and numerous epidermoid cysts or Brooke-Spiegler syndrome and spiradenomas, no syndromes have been linked to numerous trichilemmal cysts.

Continue to: Excision is effective

Excision is effective

Excision is the treatment of choice for both proliferating and nonproliferating PCs.5 The local recurrence rate of proliferating PCs is 3.7% with a rare likelihood of transformation to trichilemmal carcinoma.6

Our patient continues to be followed in clinic for monitoring and periodic excision of bothersome cysts.

A 31-year-old Hispanic man presented for evaluation of numerous disfiguring growths on his scalp. They first appeared when he was 19 years old. A review of his family history revealed that his father had 2 “cysts” on his body.

The patient had 10 nodules on his scalp and upper back (Figures 1A and 1B). The ones on his scalp lacked puncta and appeared in a “turban tumor” configuration. The lesions were pink, smooth, and semisoft, and ranged in size from 1 to 6 cm.

Six years earlier, the patient had been seen for evaluation of 20 protuberant nodules. At the time, he had been referred to plastic surgery, where 15 lesions were excised. No other treatment was reported by the patient during the 6-year gap between exams.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Pilar cysts

Pilar cysts (PC), also known as trichilemma cysts, wen, or isthmus-catagen cysts, are benign cysts that manifest as smooth, firm, well-circumscribed, pink nodules. PCs originate from the follicular isthmus of the hair’s external root sheath1 and are found in 5% to 10% of the US population.2 Possible sites of appearance include the face, neck, trunk, and extremities, although 90% of PCs develop on the scalp.1 They tend to have an autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance with linkages to the short arm of chromosome 3.3 PCs can occasionally become inflamed following infection or trauma.

Characteristic histology of PCs demonstrates semisolid, keratin-filled, subepidermal cysts lined by stratified epithelium without a granular layer (trichilemmal keratinization). Lesions excised from this patient’s scalp showed 2 subtypes of PCs: nonproliferating (FIGURE 2A) and proliferating (FIGURE 2B). Subtypes appear similar on exam but can be differentiated on histology.

With gradual growth, proliferating PCs can reach up to 25 cm in diameter.1 Rapid growth, size > 5 cm, infiltration, or a non-scalp location may indicate malignancy.4

Differential diagnosis includes lipomas

The differential diagnosis for a lesion such as this includes epidermal inclusion cysts, dermoid cysts, and lipomas. Epidermal inclusion cysts have a punctum, whereas PCs do not. Dermoid cysts are single congenital lesions that manifest much earlier than PCs. Lipomas are easily movable rubbery bulges that appear more frequently in lipid-dense areas of the body.

For this patient, the striking turban tumor–like presentation, with numerous large cysts on the scalp, initially inspired a differential diagnosis including several genetic tumor syndromes. However, unlike the association between Gardner syndrome and numerous epidermoid cysts or Brooke-Spiegler syndrome and spiradenomas, no syndromes have been linked to numerous trichilemmal cysts.

Continue to: Excision is effective

Excision is effective

Excision is the treatment of choice for both proliferating and nonproliferating PCs.5 The local recurrence rate of proliferating PCs is 3.7% with a rare likelihood of transformation to trichilemmal carcinoma.6

Our patient continues to be followed in clinic for monitoring and periodic excision of bothersome cysts.

1. Ramaswamy AS, Manjunatha HK, Sunilkumar B, et al. Morphological spectrum of pilar cysts. N Am J Med Sci. 2013;5:124-128. http://doi.org/10.4103/1947-2714.107532

2. Ibrahim AE, Barikian A, Janom H, et al. Numerous recurrent trichilemmal cysts of the scalp: differential diagnosis and surgical management. J Craniofac Surg. 2012;23:e164-168. http://doi.org/10.1097/SCS.0b013e31824cdbd2

3. Adya KA, Inamadar AC, Palit A. Multiple firm mobile swellings over the scalp. Int J Trichology. 2012;4:98-99. http://doi.org/10.4103/0974-7753.96906

4. Folpe AL, Reisenauer AK, Mentzel T, et al. Proliferating trichilemmal tumors: clinicopathologic evaluation is a guide to biologic behavior. J Cutan Pathol. 2003;30:492-498. http://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0560.2003.00041.x

5. Leppard BJ, Sanderson KV. The natural history of trichilemmal cysts. Br J Dermatol. 1976;94:379-390. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2133.1976.tb06115.x

6. Kim UG, Kook DB, Kim TH, et al. Trichilemmal carcinoma from proliferating trichilemmal cyst on the posterior neck. Arch Craniofac Surg. 2017;18:50-53. http://doi.org/10.7181/acfs.2017.18.1.50

1. Ramaswamy AS, Manjunatha HK, Sunilkumar B, et al. Morphological spectrum of pilar cysts. N Am J Med Sci. 2013;5:124-128. http://doi.org/10.4103/1947-2714.107532

2. Ibrahim AE, Barikian A, Janom H, et al. Numerous recurrent trichilemmal cysts of the scalp: differential diagnosis and surgical management. J Craniofac Surg. 2012;23:e164-168. http://doi.org/10.1097/SCS.0b013e31824cdbd2

3. Adya KA, Inamadar AC, Palit A. Multiple firm mobile swellings over the scalp. Int J Trichology. 2012;4:98-99. http://doi.org/10.4103/0974-7753.96906

4. Folpe AL, Reisenauer AK, Mentzel T, et al. Proliferating trichilemmal tumors: clinicopathologic evaluation is a guide to biologic behavior. J Cutan Pathol. 2003;30:492-498. http://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0560.2003.00041.x

5. Leppard BJ, Sanderson KV. The natural history of trichilemmal cysts. Br J Dermatol. 1976;94:379-390. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2133.1976.tb06115.x

6. Kim UG, Kook DB, Kim TH, et al. Trichilemmal carcinoma from proliferating trichilemmal cyst on the posterior neck. Arch Craniofac Surg. 2017;18:50-53. http://doi.org/10.7181/acfs.2017.18.1.50

Hemorrhagic Papular Eruption on the Dorsal Hands

The Diagnosis: Heparin-Induced Bullous Hemorrhagic Dermatosis

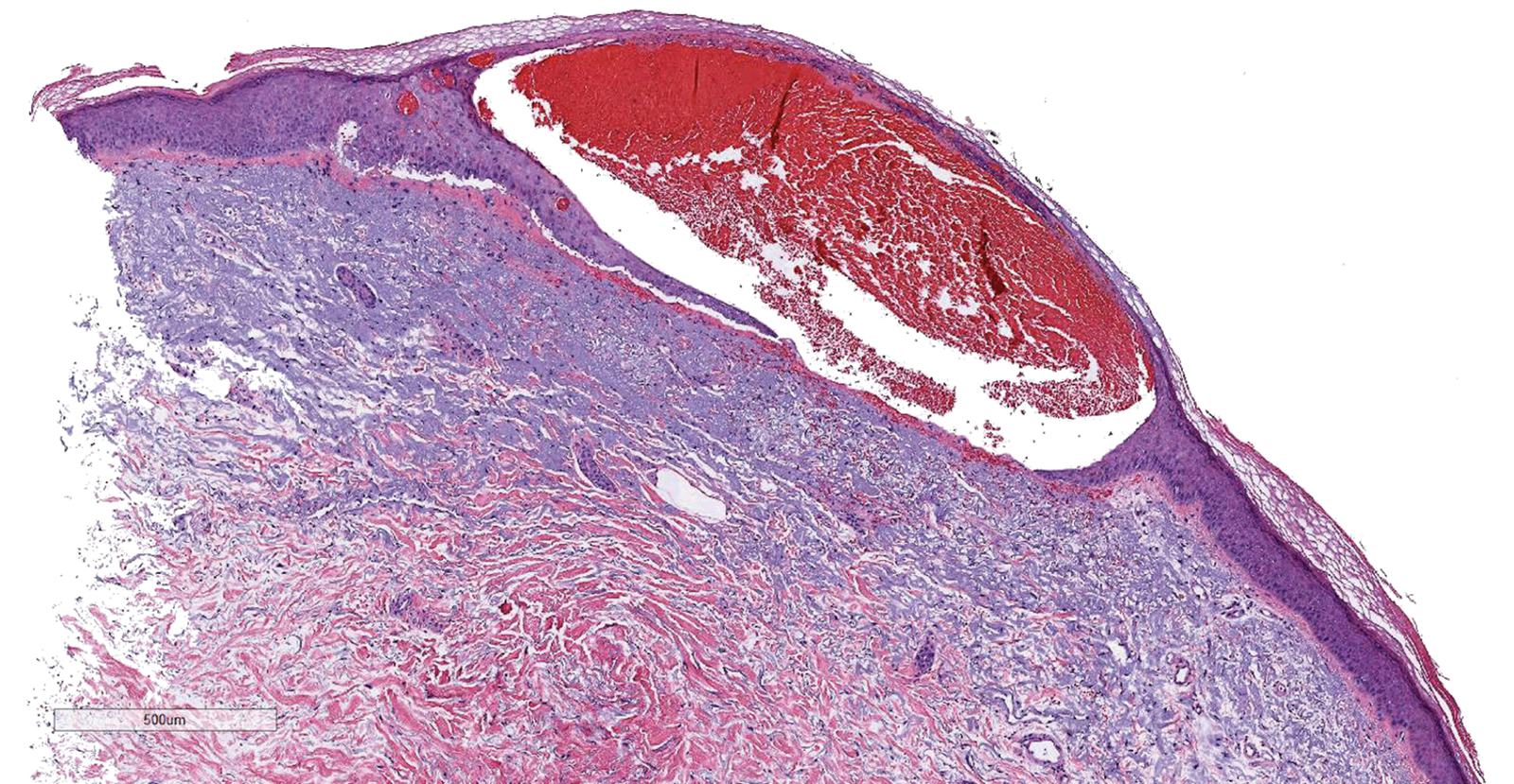

Results of a punch biopsy of one of the hemorrhagic papules revealed a subcorneal hemorrhagic vesicle without underlying vasculitis, vasculopathy, inflammation, or viral changes (Figure). Tissue and blood cultures were sterile. Heparin and platelet factor 4 antibody testing was negative. The patient was diagnosed with heparin induced bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis (BHD). After chest imaging ruled out a pulmonary embolism, anticoagulation therapy was discontinued. Respiratory symptoms improved on antibiotics, and the skin lesions resolved completely within 2 weeks.

Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis is an uncommon and underrecognized reaction to various anticoagulants. Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis presents with painless, noninflammatory, hemorrhagic vesicles and bullae occurring at sites distant from anticoagulant administration. The condition was first characterized in 2006 by Perrinaud et al,1 who presented 3 cases in patients treated with heparin and low-molecular-weight heparin. Since then, there have been at least 90 cases reported in the international literature, with elderly men found to be the more affected demographic (male to female ratio, 1.9:1).2 Typically, BHD presents within 1 week of administration of an anticoagulant, but delayed onset has been reported.2 Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis is most commonly observed with enoxaparin use but also has been described in association with unfractionated heparin, low-molecular-weight heparin products, and warfarin.2

The noninflammatory-appearing hemorrhagic papules and small plaques of BHD generally are seen on the extremities but can occur anywhere on the body including the oral mucosa.3 The differential diagnosis of BHD may include autoimmune vesiculobullous conditions, bullous drug eruptions, herpetic infection, supratherapeutic anticoagulation, porphyria cutanea tarda, amyloidosis, leukocytoclastic vasculitis, angioinvasive infections, and heparin necrosis. Diagnosis of BHD can be made clinically, but a biopsy is useful to exclude other conditions.

Histologically, BHD is characterized by the presence of intraepidermal hemorrhagic bullae without thrombotic, inflammatory, or vasculitic changes. Although heparinrelated skin lesions have been attributed to various mechanisms, including immune-mediated thrombocytopenia, type IV hypersensitivity reactions, type I allergic hypersensitivity reactions, pustulosis, and skin necrosis, the pathogenesis of BHD remains poorly understood.4 The condition has demonstrated koebnerization in some cases.5

In our patient, the absence of histologic inflammation, viral changes, vasculitis, and amyloid deposition helped rule out the other entities in the differential. The absence of heparin and platelet factor 4 antibodies helped exclude heparin necrosis. Direct immunofluorescence testing was not obtained in our patient but may be used to evaluate for an immunobullous etiology.

Management strategies for BHD are variable, and associated evidence is lacking. Treatment of BHD should be considered in the clinical context based on the necessity for anticoagulation and the severity of the eruption. Discontinuation of anticoagulation therapy, if possible, may prevent morbidity in some cases.6 If it is necessary to continue anticoagulation therapy, changing the drug or decreasing the dose are reasonable options. Skin lesions may resolve even if anticoagulation therapy is continued at the same dose.7,8 Concurrent supportive wound care is beneficial.

- Perrinaud A, Jacobi D, Machet MC, et al. Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis occurring at sites distant from subcutaneous injections of heparin: three cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54(suppl):S5-S7.

- Russo A, Curtis S, Balbuena-Merle R, et al. Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis is an under-recognized side effect of full dose low-molecular weight heparin: a case report and review of the literature [published online July 6, 2018]. Exp Hematol. 2018;7:15.

- Harris HB, Kurth BJ, Lam TK, et al. Heparin-induced bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis confined to the oral mucosa. Cutis. 2019;103:365-366, 370.

- Schindewolf M, Schwaner S, Wolter M, et al. Incidence and causes of heparin-induced skin lesions. CMAJ. 2009;181:477-481.

- Gargallo V, Romero FT, Rodríguez-Peralto JL, et al. Heparin induced bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis at a site distant from the injection. a report of five cases. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91:857-859.

- Choudhry S, Fishman PM, Hernandez C. Heparin-induced bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis. Cutis. 2013;91:93-98.

- Maldonado Cid P, Moreno Alonso de Celada R, Herranz Pinto P, et al. Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis at sites distant from subcutaneous injections of heparin: a report of 5 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:E220-E222.

- Snow SC, Pearson DR, Fathi R, et al. Heparin-induced haemorrhagic bullous dermatosis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2018;43:393-398.

The Diagnosis: Heparin-Induced Bullous Hemorrhagic Dermatosis

Results of a punch biopsy of one of the hemorrhagic papules revealed a subcorneal hemorrhagic vesicle without underlying vasculitis, vasculopathy, inflammation, or viral changes (Figure). Tissue and blood cultures were sterile. Heparin and platelet factor 4 antibody testing was negative. The patient was diagnosed with heparin induced bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis (BHD). After chest imaging ruled out a pulmonary embolism, anticoagulation therapy was discontinued. Respiratory symptoms improved on antibiotics, and the skin lesions resolved completely within 2 weeks.

Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis is an uncommon and underrecognized reaction to various anticoagulants. Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis presents with painless, noninflammatory, hemorrhagic vesicles and bullae occurring at sites distant from anticoagulant administration. The condition was first characterized in 2006 by Perrinaud et al,1 who presented 3 cases in patients treated with heparin and low-molecular-weight heparin. Since then, there have been at least 90 cases reported in the international literature, with elderly men found to be the more affected demographic (male to female ratio, 1.9:1).2 Typically, BHD presents within 1 week of administration of an anticoagulant, but delayed onset has been reported.2 Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis is most commonly observed with enoxaparin use but also has been described in association with unfractionated heparin, low-molecular-weight heparin products, and warfarin.2

The noninflammatory-appearing hemorrhagic papules and small plaques of BHD generally are seen on the extremities but can occur anywhere on the body including the oral mucosa.3 The differential diagnosis of BHD may include autoimmune vesiculobullous conditions, bullous drug eruptions, herpetic infection, supratherapeutic anticoagulation, porphyria cutanea tarda, amyloidosis, leukocytoclastic vasculitis, angioinvasive infections, and heparin necrosis. Diagnosis of BHD can be made clinically, but a biopsy is useful to exclude other conditions.

Histologically, BHD is characterized by the presence of intraepidermal hemorrhagic bullae without thrombotic, inflammatory, or vasculitic changes. Although heparinrelated skin lesions have been attributed to various mechanisms, including immune-mediated thrombocytopenia, type IV hypersensitivity reactions, type I allergic hypersensitivity reactions, pustulosis, and skin necrosis, the pathogenesis of BHD remains poorly understood.4 The condition has demonstrated koebnerization in some cases.5

In our patient, the absence of histologic inflammation, viral changes, vasculitis, and amyloid deposition helped rule out the other entities in the differential. The absence of heparin and platelet factor 4 antibodies helped exclude heparin necrosis. Direct immunofluorescence testing was not obtained in our patient but may be used to evaluate for an immunobullous etiology.

Management strategies for BHD are variable, and associated evidence is lacking. Treatment of BHD should be considered in the clinical context based on the necessity for anticoagulation and the severity of the eruption. Discontinuation of anticoagulation therapy, if possible, may prevent morbidity in some cases.6 If it is necessary to continue anticoagulation therapy, changing the drug or decreasing the dose are reasonable options. Skin lesions may resolve even if anticoagulation therapy is continued at the same dose.7,8 Concurrent supportive wound care is beneficial.

The Diagnosis: Heparin-Induced Bullous Hemorrhagic Dermatosis

Results of a punch biopsy of one of the hemorrhagic papules revealed a subcorneal hemorrhagic vesicle without underlying vasculitis, vasculopathy, inflammation, or viral changes (Figure). Tissue and blood cultures were sterile. Heparin and platelet factor 4 antibody testing was negative. The patient was diagnosed with heparin induced bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis (BHD). After chest imaging ruled out a pulmonary embolism, anticoagulation therapy was discontinued. Respiratory symptoms improved on antibiotics, and the skin lesions resolved completely within 2 weeks.

Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis is an uncommon and underrecognized reaction to various anticoagulants. Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis presents with painless, noninflammatory, hemorrhagic vesicles and bullae occurring at sites distant from anticoagulant administration. The condition was first characterized in 2006 by Perrinaud et al,1 who presented 3 cases in patients treated with heparin and low-molecular-weight heparin. Since then, there have been at least 90 cases reported in the international literature, with elderly men found to be the more affected demographic (male to female ratio, 1.9:1).2 Typically, BHD presents within 1 week of administration of an anticoagulant, but delayed onset has been reported.2 Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis is most commonly observed with enoxaparin use but also has been described in association with unfractionated heparin, low-molecular-weight heparin products, and warfarin.2

The noninflammatory-appearing hemorrhagic papules and small plaques of BHD generally are seen on the extremities but can occur anywhere on the body including the oral mucosa.3 The differential diagnosis of BHD may include autoimmune vesiculobullous conditions, bullous drug eruptions, herpetic infection, supratherapeutic anticoagulation, porphyria cutanea tarda, amyloidosis, leukocytoclastic vasculitis, angioinvasive infections, and heparin necrosis. Diagnosis of BHD can be made clinically, but a biopsy is useful to exclude other conditions.

Histologically, BHD is characterized by the presence of intraepidermal hemorrhagic bullae without thrombotic, inflammatory, or vasculitic changes. Although heparinrelated skin lesions have been attributed to various mechanisms, including immune-mediated thrombocytopenia, type IV hypersensitivity reactions, type I allergic hypersensitivity reactions, pustulosis, and skin necrosis, the pathogenesis of BHD remains poorly understood.4 The condition has demonstrated koebnerization in some cases.5

In our patient, the absence of histologic inflammation, viral changes, vasculitis, and amyloid deposition helped rule out the other entities in the differential. The absence of heparin and platelet factor 4 antibodies helped exclude heparin necrosis. Direct immunofluorescence testing was not obtained in our patient but may be used to evaluate for an immunobullous etiology.

Management strategies for BHD are variable, and associated evidence is lacking. Treatment of BHD should be considered in the clinical context based on the necessity for anticoagulation and the severity of the eruption. Discontinuation of anticoagulation therapy, if possible, may prevent morbidity in some cases.6 If it is necessary to continue anticoagulation therapy, changing the drug or decreasing the dose are reasonable options. Skin lesions may resolve even if anticoagulation therapy is continued at the same dose.7,8 Concurrent supportive wound care is beneficial.

- Perrinaud A, Jacobi D, Machet MC, et al. Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis occurring at sites distant from subcutaneous injections of heparin: three cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54(suppl):S5-S7.

- Russo A, Curtis S, Balbuena-Merle R, et al. Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis is an under-recognized side effect of full dose low-molecular weight heparin: a case report and review of the literature [published online July 6, 2018]. Exp Hematol. 2018;7:15.

- Harris HB, Kurth BJ, Lam TK, et al. Heparin-induced bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis confined to the oral mucosa. Cutis. 2019;103:365-366, 370.

- Schindewolf M, Schwaner S, Wolter M, et al. Incidence and causes of heparin-induced skin lesions. CMAJ. 2009;181:477-481.

- Gargallo V, Romero FT, Rodríguez-Peralto JL, et al. Heparin induced bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis at a site distant from the injection. a report of five cases. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91:857-859.

- Choudhry S, Fishman PM, Hernandez C. Heparin-induced bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis. Cutis. 2013;91:93-98.

- Maldonado Cid P, Moreno Alonso de Celada R, Herranz Pinto P, et al. Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis at sites distant from subcutaneous injections of heparin: a report of 5 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:E220-E222.

- Snow SC, Pearson DR, Fathi R, et al. Heparin-induced haemorrhagic bullous dermatosis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2018;43:393-398.

- Perrinaud A, Jacobi D, Machet MC, et al. Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis occurring at sites distant from subcutaneous injections of heparin: three cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54(suppl):S5-S7.

- Russo A, Curtis S, Balbuena-Merle R, et al. Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis is an under-recognized side effect of full dose low-molecular weight heparin: a case report and review of the literature [published online July 6, 2018]. Exp Hematol. 2018;7:15.

- Harris HB, Kurth BJ, Lam TK, et al. Heparin-induced bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis confined to the oral mucosa. Cutis. 2019;103:365-366, 370.

- Schindewolf M, Schwaner S, Wolter M, et al. Incidence and causes of heparin-induced skin lesions. CMAJ. 2009;181:477-481.

- Gargallo V, Romero FT, Rodríguez-Peralto JL, et al. Heparin induced bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis at a site distant from the injection. a report of five cases. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91:857-859.

- Choudhry S, Fishman PM, Hernandez C. Heparin-induced bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis. Cutis. 2013;91:93-98.

- Maldonado Cid P, Moreno Alonso de Celada R, Herranz Pinto P, et al. Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis at sites distant from subcutaneous injections of heparin: a report of 5 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:E220-E222.

- Snow SC, Pearson DR, Fathi R, et al. Heparin-induced haemorrhagic bullous dermatosis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2018;43:393-398.

A 66-year-old woman with a history of granulomatous lung disease managed with methotrexate and prednisone, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and Grave disease was admitted to the hospital for hypoxic respiratory failure. At admission, treatment was empirically initiated for pneumonia with intravenous ceftriaxone and azithromycin. Given the concern of a pulmonary embolism, intravenous heparin also was initiated. Dermatology was consulted for multiple painless blood blisters that erupted on the hands within 24 hours of admission. Physical examination revealed numerous firm hemorrhagic papules on the dorsal hands. Laboratory workup revealed a slightly elevated white blood cell count (11,800/µL [reference range, 4500–11,000/µL]), a normal stable platelet count (231,000/µL [reference range, 150,000– 350,000/µL]), and a normal international normalized ratio.

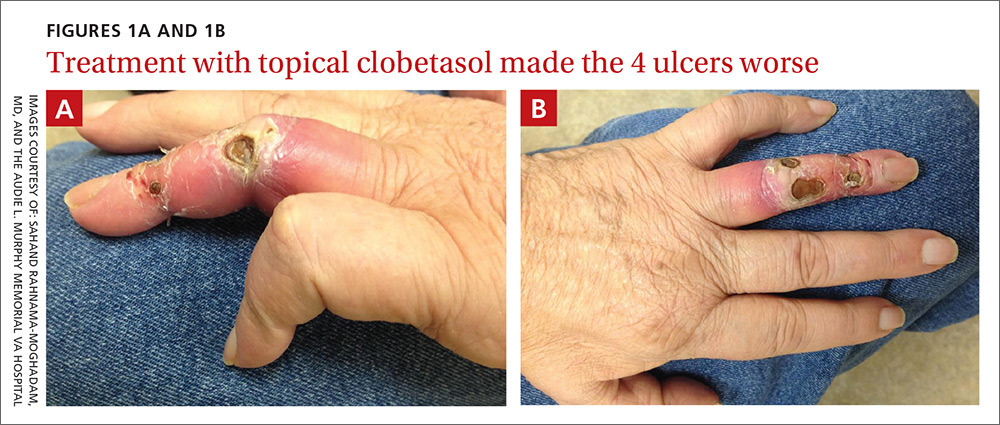

Hemodialysis patient with finger ulcerations

A 62-year-old man with end-stage renal disease presented to our dermatology clinic with 2-month-old ulcerations on his distal left ring finger. He was on hemodialysis and had a radiocephalic arteriovenous fistula (AVF) on his left arm. He had been empirically treated elsewhere with oral trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for a presumed bacterial infection, without improvement. He was then treated for contact dermatitis with topical clobetasol, which led to ulcer expansion and worsening pain.

At our clinic, the patient reported intermittent pain in his finger and paresthesias during activity and dialysis, but no tenderness of the ulcers. He had atrophy of the intrinsic left hand muscles (his non-dominant hand) with associated weakness. Three weeks earlier, he’d received a blood transfusion for anemia. Afterward, the pain in his hand improved and the ulcers decreased in size.

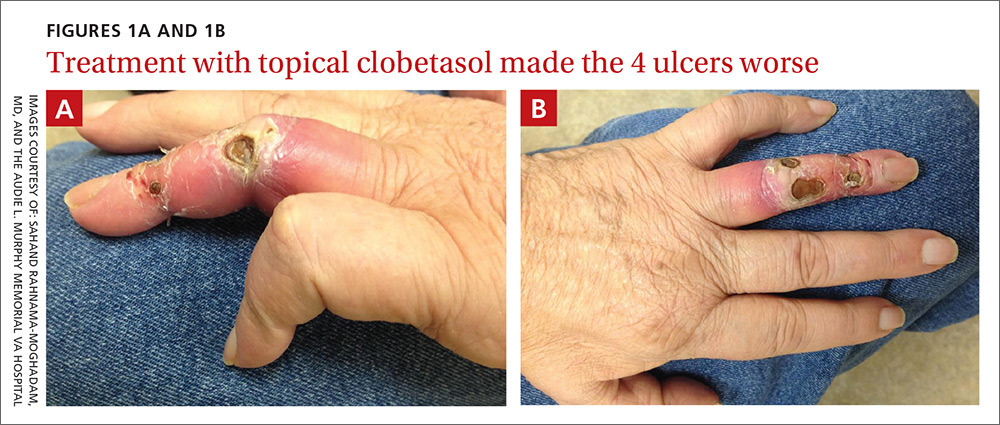

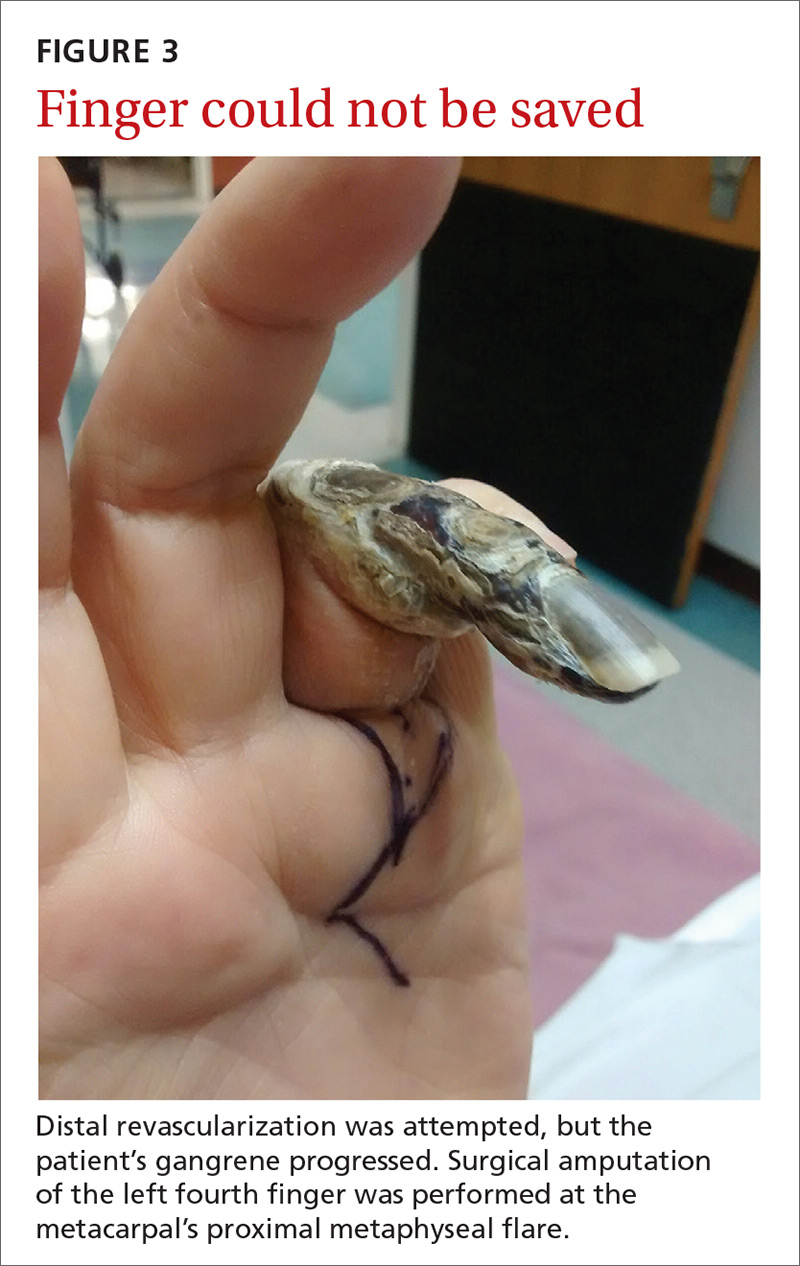

On exam, the AVF had a palpable thrill over the left forearm. The radial pulses were palpable bilaterally (2+) and the left ulnar artery was palpable, but diminished (1+). The patient’s left hand was cooler than the right (with a slight cyanotic hue and visible intrinsic muscle atrophy) and had decreased sensation to pain and temperature. Four ulcers with dry yellow eschar were located over the dorsal interphalangeal joints (FIGURES 1A AND 1B). They were essentially non-tender, but there was tenderness in the adjacent intact skin. There was violaceous blue edematous congestion noted on the fourth finger, and the distal phalange was constricted, giving it a “pseudoainhum” appearance.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Dialysis access steal syndrome

We suspected dialysis access steal syndrome (also known as AVF steal syndrome), so a duplex ultrasound was performed. The ultrasound was inconclusive. (We couldn’t confirm a limitation in blood flow, nor delineate anatomy.) So, we referred the patient for a thoracic and upper extremity angiogram.

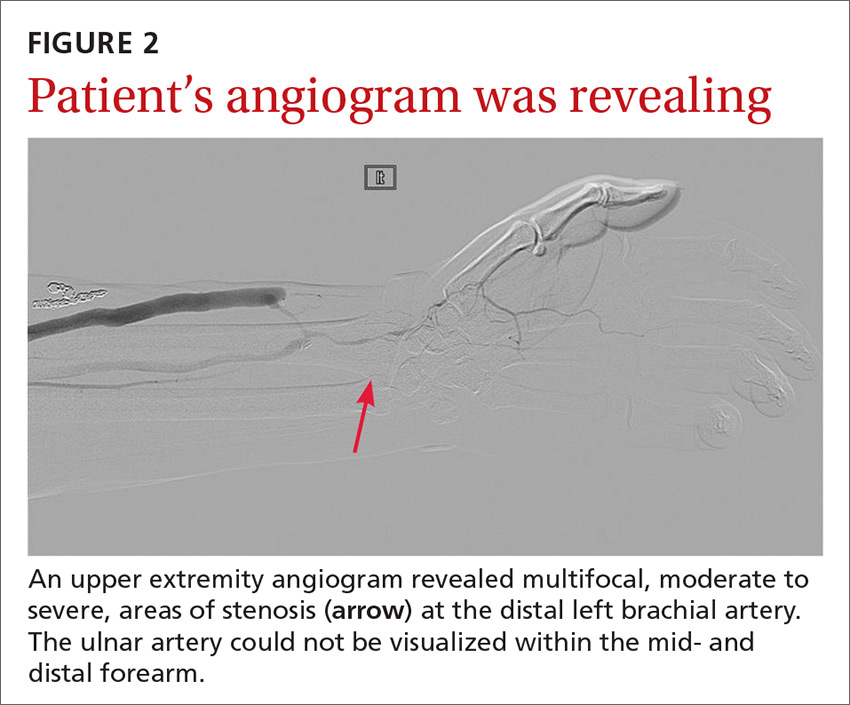

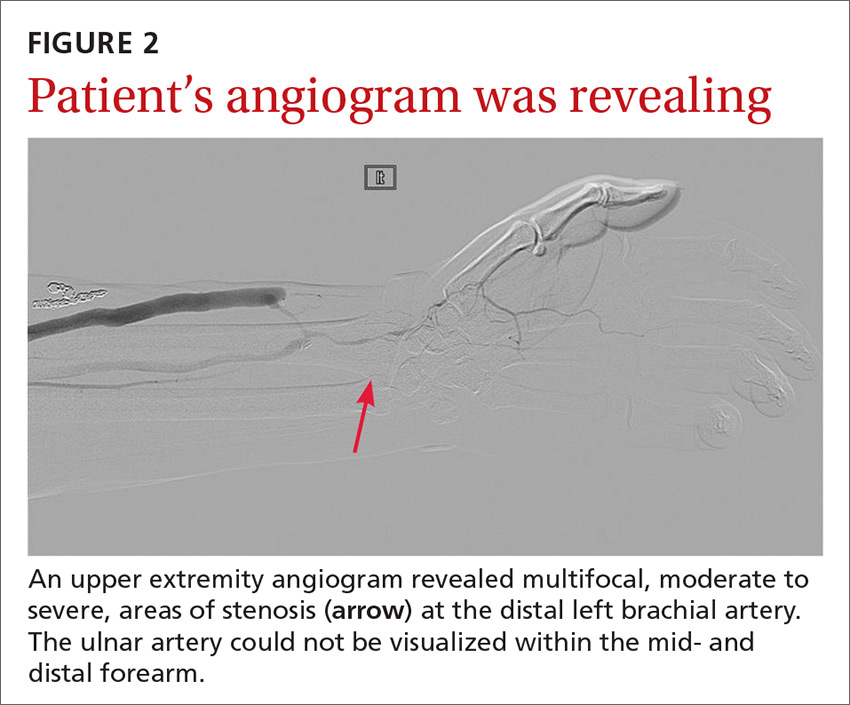

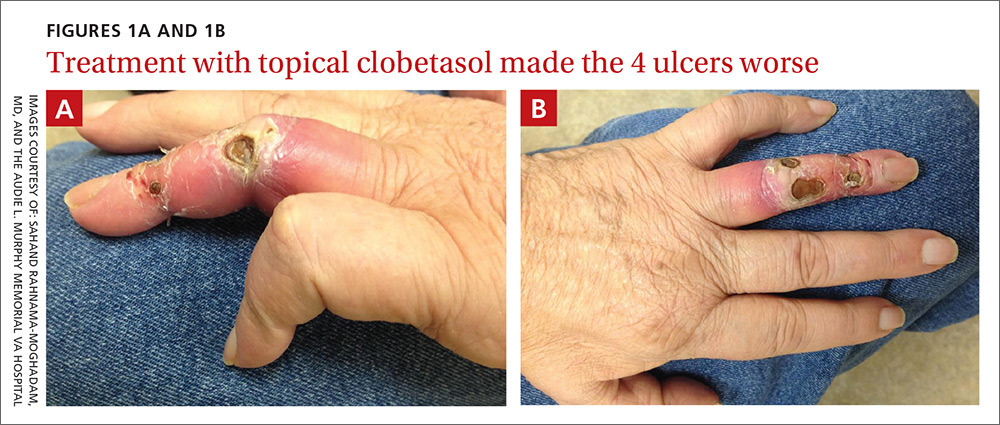

The angiogram demonstrated multifocal, moderate to severe, areas of stenosis at the distal left brachial artery. The radial artery was patent at the level of the wrist, but showed diffuse narrowing beyond the level of the arteriovenous (AV) anastomosis. There was only a faint palmar arch identified on the radial aspect of the hand with digital branches feeding the radial portion of the hand. In contrast, the ulnar artery was not seen within the mid- and distal forearm (FIGURE 2). Palmar branches to the ulnar half of the hand were not identified. The fistula itself didn’t show any stenosis.

Based on these findings, our suspicions of dialysis access steal syndrome were confirmed.

Dialysis access steal syndrome is caused by a significant decrease or reversal of blood flow in the arterial segment distal to the AVF or graft, which is induced by the low resistance of the fistula outflow. Patients with adequate collateral vasculature are able to compensate for the steal effect; however, patients with end-stage renal disease typically have preexisting vascular disease that increases the risk for vascular steal and, ultimately, demand ischemia after placement of an AVF.1 Interestingly, a steal effect occurs in 73% of patients after AVF construction, yet it is estimated that only 10% of patients demonstrating a steal phenomenon become symptomatic.2

In our patient’s case, the vaso-occlusive properties of topical steroids explain why the superpotent steroid (clobetasol) he was prescribed increased his pain and worsened the underlying problem.

A broad differential; a useful exam maneuver

The differential diagnosis of ulcers includes infection (mainly from bacterial or mycobacterial sources), trauma facilitated by neuropathy (neuropathic ulceration), vasculitis, and ischemia. When the history and physical exam suggest ischemic ulceration, then thromboembolism, thoracic outlet syndrome, vasculitis, atherosclerosis, and steal syndrome become more likely causes.

Signs and symptoms of ischemic steal syndrome are initially subtle and include extremity coolness, neurosensory changes, intrinsic muscle weakness, ulceration, and ultimately, gangrene of the affected extremity.3,4 A cold, numb, and/or painful hand during dialysis is another clue.3 Factors that increase the likelihood of the syndrome include age >60 years, female sex, and the presence of diabetes or peripheral artery disease.2,3,5,6

One physical exam maneuver that can help make the diagnosis of steal syndrome is manual occlusion of the AVF. If palpable distal pulses disappear when the AVF is patent and reappear when the fistula is occluded with downward pressure, then AVF steal syndrome is likely.4 Pain at rest, sensory loss, loss of pulse, and digital gangrene are emergency symptoms that warrant immediate surgical evaluation.3

Tests will confirm suspicions. Doppler ultrasound can be used to assess changes in the blood flow rate of the affected vessels when the AVF is patent vs when it is occluded. Similarly, pulse oximetry can be used with and without AVF occlusion to compare changes in oxygen saturation. The confirmatory diagnosis, however, is made via a fistulogram (angiography) with and without manual compression.6 Images taken after dye injection into the AVF show dramatic improvement of distal blood flow with AVF compression.

Treatment requires surgery

Severe steal-related ischemic manifestations that threaten the function and viability of digits require surgical treatment that is primarily directed toward improving distal blood flow and secondarily toward preserving hemodialysis access. Several surgical treatments are commonly used, including access ligation, banding, elongation, distal arterial ligation, and distal revascularization and interval ligation.2-5,7

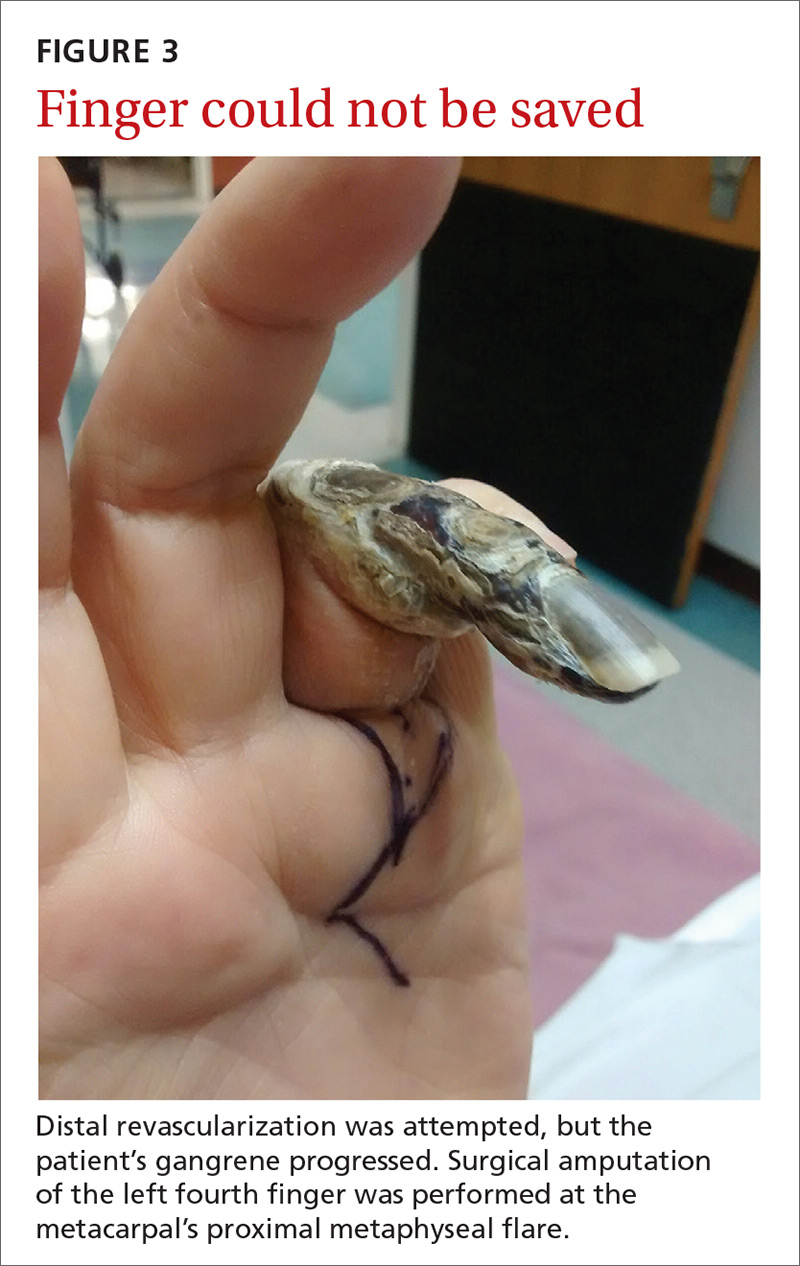

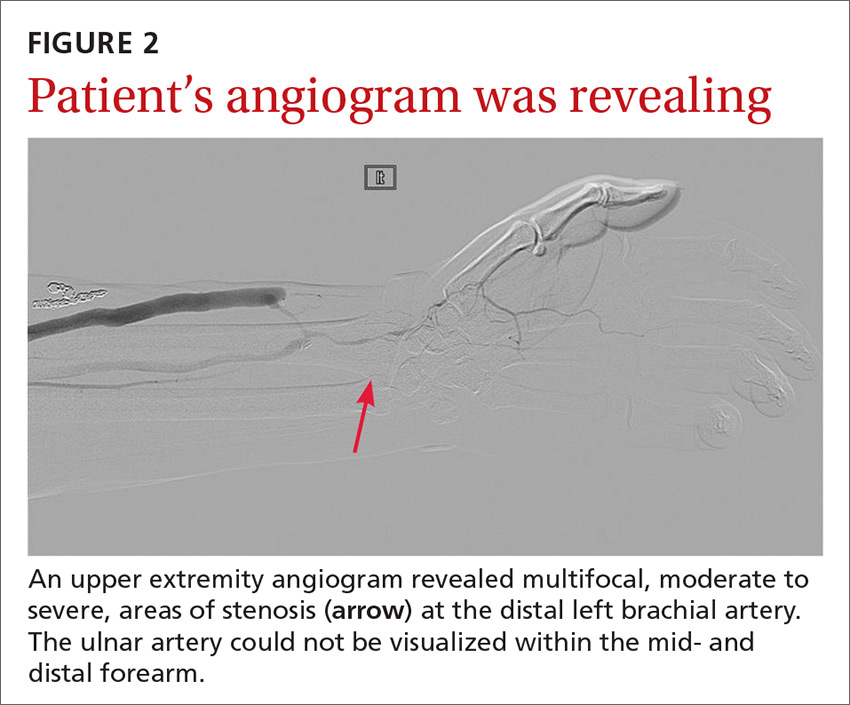

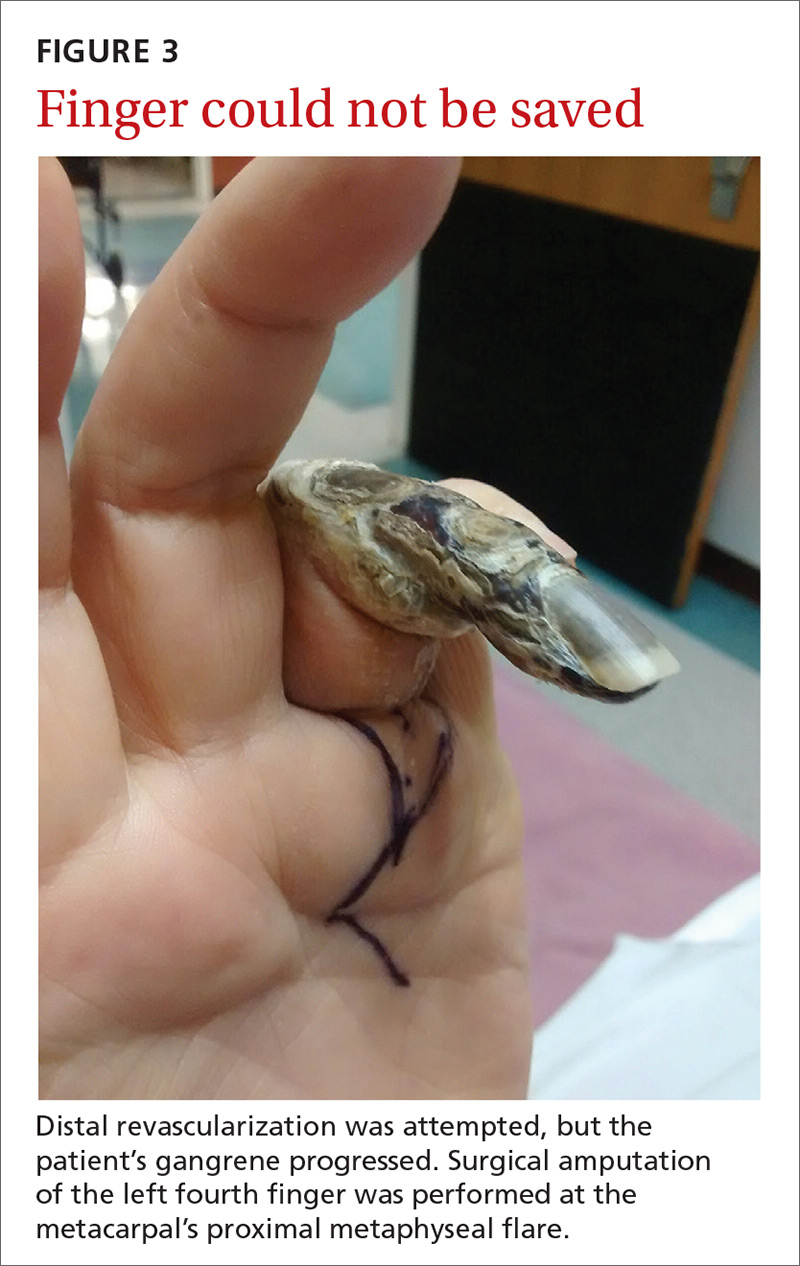

Our patient. Distal revascularization was attempted, but unfortunately, the patient’s gangrene was progressive (FIGURE 3) and surgical amputation of the left fourth finger was performed at the metacarpal’s proximal metaphyseal flare. The patient was transitioned to peritoneal dialysis to avoid further ischemia.

CORRESPONDENCE

Sahand Rahnama-Moghadam, MD, Department of Dermatology, Indiana University, 545 Barnhill Drive, Indianapolis, IN 46202; srahnama@iupui.edu.

1. Morsy AH, Kulbaski M, Chen C, et al. Incidence and characteristics of patients with hand ischemia after a hemodialysis access procedure. J Surg Res. 1998;74:8-10.

2. Puryear A, Villarreal S, Wells MJ, et al. JAAD grand rounds quiz. Hand ischemia in a hemodialysis patient. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:393-395.

3. Pelle MT, Miller OF 3rd. Dermatologic manifestations and management of vascular steal syndrome in hemodialysis patients with arteriovenous fistulas. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1296-1298.

4. Wixon CL, Hughes JD, Mills JL. Understanding strategies for the treatment of ischemic steal syndrome after hemodialysis access. J Am Coll Surg. 2000;191:301-310.

5. Gupta N, Yuo TH, Konig G 4th, et al. Treatment strategies of arterial steal after arteriovenous access. J Vasc Surg. 2011;54:162-167.

6. Zamani P, Kaufman J, Kinlay S. Ischemic steal syndrome following arm arteriovenous fistula for hemodialysis. Vasc Med. 2009;14:371-376.

7. Leake AE, Winger DG, Leers SA, et al. Management and outcomes of dialysis access-associated steal syndrome. J Vasc Surg. 2015;61:754-760.

A 62-year-old man with end-stage renal disease presented to our dermatology clinic with 2-month-old ulcerations on his distal left ring finger. He was on hemodialysis and had a radiocephalic arteriovenous fistula (AVF) on his left arm. He had been empirically treated elsewhere with oral trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for a presumed bacterial infection, without improvement. He was then treated for contact dermatitis with topical clobetasol, which led to ulcer expansion and worsening pain.

At our clinic, the patient reported intermittent pain in his finger and paresthesias during activity and dialysis, but no tenderness of the ulcers. He had atrophy of the intrinsic left hand muscles (his non-dominant hand) with associated weakness. Three weeks earlier, he’d received a blood transfusion for anemia. Afterward, the pain in his hand improved and the ulcers decreased in size.

On exam, the AVF had a palpable thrill over the left forearm. The radial pulses were palpable bilaterally (2+) and the left ulnar artery was palpable, but diminished (1+). The patient’s left hand was cooler than the right (with a slight cyanotic hue and visible intrinsic muscle atrophy) and had decreased sensation to pain and temperature. Four ulcers with dry yellow eschar were located over the dorsal interphalangeal joints (FIGURES 1A AND 1B). They were essentially non-tender, but there was tenderness in the adjacent intact skin. There was violaceous blue edematous congestion noted on the fourth finger, and the distal phalange was constricted, giving it a “pseudoainhum” appearance.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Dialysis access steal syndrome

We suspected dialysis access steal syndrome (also known as AVF steal syndrome), so a duplex ultrasound was performed. The ultrasound was inconclusive. (We couldn’t confirm a limitation in blood flow, nor delineate anatomy.) So, we referred the patient for a thoracic and upper extremity angiogram.

The angiogram demonstrated multifocal, moderate to severe, areas of stenosis at the distal left brachial artery. The radial artery was patent at the level of the wrist, but showed diffuse narrowing beyond the level of the arteriovenous (AV) anastomosis. There was only a faint palmar arch identified on the radial aspect of the hand with digital branches feeding the radial portion of the hand. In contrast, the ulnar artery was not seen within the mid- and distal forearm (FIGURE 2). Palmar branches to the ulnar half of the hand were not identified. The fistula itself didn’t show any stenosis.

Based on these findings, our suspicions of dialysis access steal syndrome were confirmed.

Dialysis access steal syndrome is caused by a significant decrease or reversal of blood flow in the arterial segment distal to the AVF or graft, which is induced by the low resistance of the fistula outflow. Patients with adequate collateral vasculature are able to compensate for the steal effect; however, patients with end-stage renal disease typically have preexisting vascular disease that increases the risk for vascular steal and, ultimately, demand ischemia after placement of an AVF.1 Interestingly, a steal effect occurs in 73% of patients after AVF construction, yet it is estimated that only 10% of patients demonstrating a steal phenomenon become symptomatic.2

In our patient’s case, the vaso-occlusive properties of topical steroids explain why the superpotent steroid (clobetasol) he was prescribed increased his pain and worsened the underlying problem.

A broad differential; a useful exam maneuver

The differential diagnosis of ulcers includes infection (mainly from bacterial or mycobacterial sources), trauma facilitated by neuropathy (neuropathic ulceration), vasculitis, and ischemia. When the history and physical exam suggest ischemic ulceration, then thromboembolism, thoracic outlet syndrome, vasculitis, atherosclerosis, and steal syndrome become more likely causes.

Signs and symptoms of ischemic steal syndrome are initially subtle and include extremity coolness, neurosensory changes, intrinsic muscle weakness, ulceration, and ultimately, gangrene of the affected extremity.3,4 A cold, numb, and/or painful hand during dialysis is another clue.3 Factors that increase the likelihood of the syndrome include age >60 years, female sex, and the presence of diabetes or peripheral artery disease.2,3,5,6

One physical exam maneuver that can help make the diagnosis of steal syndrome is manual occlusion of the AVF. If palpable distal pulses disappear when the AVF is patent and reappear when the fistula is occluded with downward pressure, then AVF steal syndrome is likely.4 Pain at rest, sensory loss, loss of pulse, and digital gangrene are emergency symptoms that warrant immediate surgical evaluation.3

Tests will confirm suspicions. Doppler ultrasound can be used to assess changes in the blood flow rate of the affected vessels when the AVF is patent vs when it is occluded. Similarly, pulse oximetry can be used with and without AVF occlusion to compare changes in oxygen saturation. The confirmatory diagnosis, however, is made via a fistulogram (angiography) with and without manual compression.6 Images taken after dye injection into the AVF show dramatic improvement of distal blood flow with AVF compression.

Treatment requires surgery

Severe steal-related ischemic manifestations that threaten the function and viability of digits require surgical treatment that is primarily directed toward improving distal blood flow and secondarily toward preserving hemodialysis access. Several surgical treatments are commonly used, including access ligation, banding, elongation, distal arterial ligation, and distal revascularization and interval ligation.2-5,7

Our patient. Distal revascularization was attempted, but unfortunately, the patient’s gangrene was progressive (FIGURE 3) and surgical amputation of the left fourth finger was performed at the metacarpal’s proximal metaphyseal flare. The patient was transitioned to peritoneal dialysis to avoid further ischemia.

CORRESPONDENCE

Sahand Rahnama-Moghadam, MD, Department of Dermatology, Indiana University, 545 Barnhill Drive, Indianapolis, IN 46202; srahnama@iupui.edu.

A 62-year-old man with end-stage renal disease presented to our dermatology clinic with 2-month-old ulcerations on his distal left ring finger. He was on hemodialysis and had a radiocephalic arteriovenous fistula (AVF) on his left arm. He had been empirically treated elsewhere with oral trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for a presumed bacterial infection, without improvement. He was then treated for contact dermatitis with topical clobetasol, which led to ulcer expansion and worsening pain.

At our clinic, the patient reported intermittent pain in his finger and paresthesias during activity and dialysis, but no tenderness of the ulcers. He had atrophy of the intrinsic left hand muscles (his non-dominant hand) with associated weakness. Three weeks earlier, he’d received a blood transfusion for anemia. Afterward, the pain in his hand improved and the ulcers decreased in size.

On exam, the AVF had a palpable thrill over the left forearm. The radial pulses were palpable bilaterally (2+) and the left ulnar artery was palpable, but diminished (1+). The patient’s left hand was cooler than the right (with a slight cyanotic hue and visible intrinsic muscle atrophy) and had decreased sensation to pain and temperature. Four ulcers with dry yellow eschar were located over the dorsal interphalangeal joints (FIGURES 1A AND 1B). They were essentially non-tender, but there was tenderness in the adjacent intact skin. There was violaceous blue edematous congestion noted on the fourth finger, and the distal phalange was constricted, giving it a “pseudoainhum” appearance.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Dialysis access steal syndrome

We suspected dialysis access steal syndrome (also known as AVF steal syndrome), so a duplex ultrasound was performed. The ultrasound was inconclusive. (We couldn’t confirm a limitation in blood flow, nor delineate anatomy.) So, we referred the patient for a thoracic and upper extremity angiogram.

The angiogram demonstrated multifocal, moderate to severe, areas of stenosis at the distal left brachial artery. The radial artery was patent at the level of the wrist, but showed diffuse narrowing beyond the level of the arteriovenous (AV) anastomosis. There was only a faint palmar arch identified on the radial aspect of the hand with digital branches feeding the radial portion of the hand. In contrast, the ulnar artery was not seen within the mid- and distal forearm (FIGURE 2). Palmar branches to the ulnar half of the hand were not identified. The fistula itself didn’t show any stenosis.

Based on these findings, our suspicions of dialysis access steal syndrome were confirmed.

Dialysis access steal syndrome is caused by a significant decrease or reversal of blood flow in the arterial segment distal to the AVF or graft, which is induced by the low resistance of the fistula outflow. Patients with adequate collateral vasculature are able to compensate for the steal effect; however, patients with end-stage renal disease typically have preexisting vascular disease that increases the risk for vascular steal and, ultimately, demand ischemia after placement of an AVF.1 Interestingly, a steal effect occurs in 73% of patients after AVF construction, yet it is estimated that only 10% of patients demonstrating a steal phenomenon become symptomatic.2

In our patient’s case, the vaso-occlusive properties of topical steroids explain why the superpotent steroid (clobetasol) he was prescribed increased his pain and worsened the underlying problem.

A broad differential; a useful exam maneuver

The differential diagnosis of ulcers includes infection (mainly from bacterial or mycobacterial sources), trauma facilitated by neuropathy (neuropathic ulceration), vasculitis, and ischemia. When the history and physical exam suggest ischemic ulceration, then thromboembolism, thoracic outlet syndrome, vasculitis, atherosclerosis, and steal syndrome become more likely causes.

Signs and symptoms of ischemic steal syndrome are initially subtle and include extremity coolness, neurosensory changes, intrinsic muscle weakness, ulceration, and ultimately, gangrene of the affected extremity.3,4 A cold, numb, and/or painful hand during dialysis is another clue.3 Factors that increase the likelihood of the syndrome include age >60 years, female sex, and the presence of diabetes or peripheral artery disease.2,3,5,6

One physical exam maneuver that can help make the diagnosis of steal syndrome is manual occlusion of the AVF. If palpable distal pulses disappear when the AVF is patent and reappear when the fistula is occluded with downward pressure, then AVF steal syndrome is likely.4 Pain at rest, sensory loss, loss of pulse, and digital gangrene are emergency symptoms that warrant immediate surgical evaluation.3

Tests will confirm suspicions. Doppler ultrasound can be used to assess changes in the blood flow rate of the affected vessels when the AVF is patent vs when it is occluded. Similarly, pulse oximetry can be used with and without AVF occlusion to compare changes in oxygen saturation. The confirmatory diagnosis, however, is made via a fistulogram (angiography) with and without manual compression.6 Images taken after dye injection into the AVF show dramatic improvement of distal blood flow with AVF compression.

Treatment requires surgery

Severe steal-related ischemic manifestations that threaten the function and viability of digits require surgical treatment that is primarily directed toward improving distal blood flow and secondarily toward preserving hemodialysis access. Several surgical treatments are commonly used, including access ligation, banding, elongation, distal arterial ligation, and distal revascularization and interval ligation.2-5,7

Our patient. Distal revascularization was attempted, but unfortunately, the patient’s gangrene was progressive (FIGURE 3) and surgical amputation of the left fourth finger was performed at the metacarpal’s proximal metaphyseal flare. The patient was transitioned to peritoneal dialysis to avoid further ischemia.

CORRESPONDENCE

Sahand Rahnama-Moghadam, MD, Department of Dermatology, Indiana University, 545 Barnhill Drive, Indianapolis, IN 46202; srahnama@iupui.edu.

1. Morsy AH, Kulbaski M, Chen C, et al. Incidence and characteristics of patients with hand ischemia after a hemodialysis access procedure. J Surg Res. 1998;74:8-10.

2. Puryear A, Villarreal S, Wells MJ, et al. JAAD grand rounds quiz. Hand ischemia in a hemodialysis patient. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:393-395.

3. Pelle MT, Miller OF 3rd. Dermatologic manifestations and management of vascular steal syndrome in hemodialysis patients with arteriovenous fistulas. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1296-1298.

4. Wixon CL, Hughes JD, Mills JL. Understanding strategies for the treatment of ischemic steal syndrome after hemodialysis access. J Am Coll Surg. 2000;191:301-310.

5. Gupta N, Yuo TH, Konig G 4th, et al. Treatment strategies of arterial steal after arteriovenous access. J Vasc Surg. 2011;54:162-167.

6. Zamani P, Kaufman J, Kinlay S. Ischemic steal syndrome following arm arteriovenous fistula for hemodialysis. Vasc Med. 2009;14:371-376.

7. Leake AE, Winger DG, Leers SA, et al. Management and outcomes of dialysis access-associated steal syndrome. J Vasc Surg. 2015;61:754-760.

1. Morsy AH, Kulbaski M, Chen C, et al. Incidence and characteristics of patients with hand ischemia after a hemodialysis access procedure. J Surg Res. 1998;74:8-10.

2. Puryear A, Villarreal S, Wells MJ, et al. JAAD grand rounds quiz. Hand ischemia in a hemodialysis patient. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:393-395.

3. Pelle MT, Miller OF 3rd. Dermatologic manifestations and management of vascular steal syndrome in hemodialysis patients with arteriovenous fistulas. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1296-1298.

4. Wixon CL, Hughes JD, Mills JL. Understanding strategies for the treatment of ischemic steal syndrome after hemodialysis access. J Am Coll Surg. 2000;191:301-310.

5. Gupta N, Yuo TH, Konig G 4th, et al. Treatment strategies of arterial steal after arteriovenous access. J Vasc Surg. 2011;54:162-167.

6. Zamani P, Kaufman J, Kinlay S. Ischemic steal syndrome following arm arteriovenous fistula for hemodialysis. Vasc Med. 2009;14:371-376.

7. Leake AE, Winger DG, Leers SA, et al. Management and outcomes of dialysis access-associated steal syndrome. J Vasc Surg. 2015;61:754-760.

Mucous Membrane Pemphigoid Involving the Trachea and Bronchi: An Extremely Rare and Life-Threatening Presentation

To the Editor:

Mucous membrane pemphigoid (MMP) is an autoimmune blistering disorder that causes subepithelial damage and scarring of mucosal surfaces with or without skin involvement.1 The clinical presentation is highly variable. The oropharynx is the most common site of initial presentation, followed by ocular, nasopharyngeal, anogenital, skin, laryngeal, and esophageal involvement.2 Patients often present to a variety of specialists depending on initial symptoms, and due to the diverse clinical manifestations, MMP often is misdiagnosed. Our patient presented an even greater challenge because the disease progressed to tracheal and bronchial involvement.

A 37-year-old man presented to his primary care physician with a chief concern of a sore throat and oral ulcers. The patient was treated with a course of antibiotics followed by a nystatin oral solution. He continued to develop ulcerative lesions on the soft palate, posterior pharynx, and nasal mucosae. He sought treatment from 2 otolaryngologists (ENTs) and a gastroenterologist, and continued to be treated with multiple oral antibiotics, fluconazole, and topical nystatin. Despite treatment, the patient developed pansinusitis and laryngitis and presented to the ENT department at our institution with severe hoarseness and dyspnea on exertion. Examination by the ENT department revealed ulcerative lesions of the nares with stenosis and ulcers along the soft palate. Videolaryngostroboscopy showed remarkable supraglottic edema with thick endolaryngeal mucus. The patient worked as a funeral director and had notable formaldehyde exposure. He also hunted wild game and performed taxidermy regularly.

The patient was admitted and treated with intravenous dexamethasone for a compromised airway. Subsequently, he was taken to the operating room and had biopsies performed of the posterior pharynx. Given his exposure history, the infectious disease department was consulted and he was evaluated for multiple viral, bacterial, and fungal suspects including leishmania and tularemia. Age-appropriate screening, physical examination, and review of systems were negative for an underlying neoplasm. Histopathologic examination revealed a subepithelial vesicular mucositis with a mixed infiltrate of lymphocytes and histiocytes. Direct immunofluorescence microscopy demonstrated strong linear fluorescence along the epithelial-subepithelial junction with IgG and C3. Based on these findings, the diagnosis of MMP was made.

Further testing for bullous pemphigoid antigen 1 (BP230) and bullous pemphigoid antigen 2 (BP180) were negative. On one occasion the patient tested positive for anti-BP230 IgG, but it was at a level judged to be insignificant (7.5 [reference range, <9]). The patient also was negative for autoantibodies against desmoglein 1 and 3. Indirect immunofluorescence using rat bladder epithelium was not performed.

The patient was started on methotrexate and oral prednisone by the rheumatology department, but after 1 week, he presented in respiratory distress and was taken for an emergency tracheostomy. The patient eventually was referred to the dermatology department where methotrexate was discontinued and the patient was started on titrating doses of prednisone and mycophenolate mofetil. Eight weeks later, the patient became completely aphonic and was taken by ENT for dilation of the supraglottic, glottic, and subglottic stenosis with mucosal triamcinolone injections. Doxycycline 100 mg twice daily and nicotinamide 500 mg twice daily was initiated in addition to mycophenolate mofetil 3 g and prednisone 80 mg, but again the patient developed near-complete tracheal stenosis just proximal to the tracheostomy entry site. At 16 weeks, balloon dilation was repeated with dexamethasone injections and topical mitomycin C. Subsequently, the patient regained some use of his voice. Although the next several laryngoscopes showed improvement in the patient’s epiglottis and glottis, the trachea continued to require debridement and dilation.

Despite maximal medical therapy and surgical interventions, the patient had little improvement in his voice and large clots of blood obstructed his tracheostomy daily. He was unable to sleep in his preferred position on the stomach (prone) due to dyspnea but had less distress sleeping on his back (supine). The patient was referred to the pulmonology department for an endotracheobronchoscopy to further evaluate the airway. It was discovered that the mucosa of the trachea from the level of the tracheostomy to the carina was friable with active erosions and thick bloody secretions (Figure 1). Lesions extended as far as the scope was able to visualize to the left upper lobe takeoff and the right mainstem bronchus (Figure 2). Biopsies of the carinal mucosa showed 3+/3+ linear fluorescence with IgG along the dermoepidermal junction. Salt-split studies were performed, but because the specimen was fragmented, it was not possible to assess if the fluorescence was present at the floor or at the roof of the split.

Given the severity of disease and failure to respond to other aggressive immunosuppressive therapies as well as having been with a tracheostomy for 22 months, the patient was started on 2 doses of intravenous rituximab 1 g 2 weeks apart along with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (3 times weekly) for pneumocystis pneumonia prophylaxis. No complications were observed during infusions. After 2 rituximab infusions, he was weaned off of prednisone and a repeat bronchoscopy showed no airway ulcers beyond the distal trachea or endobronchial obstruction. However, the subglottic space and area above the tracheostomy showed remarkable stenosis with a cobblestone pattern and granulation tissue with continued narrowing of the subglottic area. The ENT performed further dilation and after 34 months, the tracheostomy was removed and a T-tube was placed. The patient required cleaning out of the T-tube approximately every 3 months, and after 2 years the original T-tube was replaced with a new one. At the time of this report, the ENT recommended removing the T-tube, but the patient was reluctant to do so; therefore, a second T-tube replacement is planned. He continues to do well without relapse and has been off all medical therapy for nearly 4 years.

Mucous membrane pemphigoid is an acquired autoimmune subepithelial blistering disease that predominantly affects mucous membranes with or without skin involvement. This condition has been referred to as cicatricial pemphigoid, oral pemphigoid, and ocular cicatricial pemphigoid, among other names. It is characterized by linear deposition of IgG, IgA, or C3 along the epithelial basement membrane zone. According to the international consensus on MMP, the target antigens identified in the epithelial basement membrane zone include bullous pemphigoid antigen 1 (BP230), bullous pemphigoid antigen 2 (BP180), laminin 5 (α3, β3, γ2 chains), laminin 6 (α3 chain), type VII collagen, and integrin β4 subunit.3 Not all patients with MMP will have circulating autoantibodies to the above components, and although our patient did have detectable anti-BP230 IgG, it was not considered clinically significant. Furthermore, the type of autoantibody does not impact decisions regarding therapy selection.3

Although rare, MMP is well-known to dermatologists and ophthalmologists who manage a large majority of MMP patients depending on which mucosa is involved. Mucous membrane pemphigoid is extremely rare in the lower respiratory tract, and when these lesions are discovered, it often is in the face of life-threatening respiratory distress. Mucous membrane pemphigoid is a challenging disease to treat, even more so when the primary specialty physician is unable to visualize the affected areas. Our patient’s disease was limited primarily to the pharynx, larynx, trachea, and bronchi with few oral lesions. According to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms mucous membrane pemphigus, cicatricial pemphigoid, trachea, bronchus, and fatal, 8 reports (7 case reports and 1 prospective study) of MMP involving the lower respiratory tract have been published.4-11 Of the case reports, each patient also presented with involvement of the eyes or skin.4,5,7-11 Four of these cases were fatal secondary to cardiopulmonary arrest.5,7,9,10 In the prospective study, 110 consecutive patients with clinical, histologic, and immunologic criteria of MMP were examined with a flexible nasopharyngolaryngoscope.6 Thirty-eight patients had nose or throat symptoms but only 10 had laryngeal involvement and 5 had acute dyspnea. The nasal valves, choanae, pharynx, and/or larynx were severely scarred in 7 patients, which was fatal in 3.6

Medical treatment should be based on the following factors of the patient’s disease: site, severity, and rapidity of progression.3 High-risk patients can be defined as those who have lesions at any of the following sites: ocular, genital, nasopharyngeal, esophageal, and laryngeal mucosae. As our patient had involvement at several high-risk sites, in particular sites only visualized by various scoping procedures, a team of physicians including dermatologists, ENT physicians, pulmonologists, and oncologists was necessary to facilitate his care. Scarring is the hallmark of MMP and prevention of scarring is the most important aspect of treatment of MMP. Surgical repair of the previously involved mucosa is difficult, as the tissue is prone to re-scarring and difficult to heal. Over the last several years, there has been increasing evidence for the use of rituximab in autoimmune bullous skin diseases including pemphigus vulgaris, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, and MMP.12-14 After 2 infusions of rituximab, our patient had clearance of his disease and currently is doing well with a T-tube.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kim Yancey, MD (Dallas, Texas), for providing access to the patient’s diagnostic laboratory immunology and reviewing biopsy specimens; Luis Angel, MD (San Antonio, Texas), for providing bronchoscopy photographs; and C. Blake Simpson, MD (San Antonio, Texas), for co-managing this challenging case.

- James WD, Berger TG, Elston D. Chronic blistering diseases. In: James WD, Berger TG, Elston D. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Sanders Elsevier; 2010:448-467.

- Neff AG, Turner M, Mutasim DF. Treatment strategies in mucous membrane pemphigoid. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2008;4:617-626.

- Chan LS, Ahmed AR, Anhalt GJ, et al. The first international consensus on mucous membrane pemphigoid: definition, diagnostic criteria, pathogenic factors, medical treatment, and prognostic indicators. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:370-379.

- Kato K, Moriyama Y, Saito H, et al. A case of mucous membrane pemphigoid involving the trachea and bronchus with autoantibodies to β3 subunit of laminin-332. Acta Derm Venereol. 2014;94:237-238.

- Gamm DM, Harris A, Mehran RJ, et al. Mucous membrane pemphigoid with fatal bronchial involvement in a seventeen-year-old girl. Cornea. 2006;25:474-478.

- Alexandre M, Brette MD, Pascal F, et al. A prospective study of upper aerodigestive tract manifestations of mucous membrane pemphigoid. Medicine (Baltimore). 2006;85:239-252.

- de Carvalho CR, Amato MB, Da Silva LM, et al. Obstructive respiratory failure in cicatricial pemphigoid. Thorax. 1989;44:601-602.

- Müller LC, Salzer GM. Stenosis of left mainstem bronchus in a case of cicatricial pemphigoid. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1988;2:284-286.

- Camisa C, Allen CM. Death from CP in a young woman with oral, laryngeal, and bronchial involvement. Cutis. 1987;40:426-429.

- Derbes VJ, Pitot HC, Chernosky ME. Fatal cicatricial mucous membrane pemphigoid of the trachea. Dermatol Trop Ecol Geogr. 1962;1:114-117.

- Wieme N, Lambert J, Moerman M, et al. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita with combined features of bullous pemphigoid and cicatricial pemphigoid. Dermatology. 1999;198:310-313.

- Taylor J, McMillan R, Shephard M, et al. World Workshop on Oral Medicine VI: a systematic review of the treatment of mucous membrane pemphigoid [published online March 11, 2015]. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2015;120:161.e20-171.e20.

- Sobolewska B, Deuter C, Zierhut M. Current medical treatment of ocular mucous membrane pemphigoid [published online July 9, 2013]. Ocul Surf. 2013;11:259-266.

- Maley A, Warren M, Haberman I, et al. Rituximab combined with conventional therapy versus conventional therapy alone for the treatment of mucous membrane pemphigoid (MMP) [published online February 28, 2016]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:835-840.

To the Editor:

Mucous membrane pemphigoid (MMP) is an autoimmune blistering disorder that causes subepithelial damage and scarring of mucosal surfaces with or without skin involvement.1 The clinical presentation is highly variable. The oropharynx is the most common site of initial presentation, followed by ocular, nasopharyngeal, anogenital, skin, laryngeal, and esophageal involvement.2 Patients often present to a variety of specialists depending on initial symptoms, and due to the diverse clinical manifestations, MMP often is misdiagnosed. Our patient presented an even greater challenge because the disease progressed to tracheal and bronchial involvement.

A 37-year-old man presented to his primary care physician with a chief concern of a sore throat and oral ulcers. The patient was treated with a course of antibiotics followed by a nystatin oral solution. He continued to develop ulcerative lesions on the soft palate, posterior pharynx, and nasal mucosae. He sought treatment from 2 otolaryngologists (ENTs) and a gastroenterologist, and continued to be treated with multiple oral antibiotics, fluconazole, and topical nystatin. Despite treatment, the patient developed pansinusitis and laryngitis and presented to the ENT department at our institution with severe hoarseness and dyspnea on exertion. Examination by the ENT department revealed ulcerative lesions of the nares with stenosis and ulcers along the soft palate. Videolaryngostroboscopy showed remarkable supraglottic edema with thick endolaryngeal mucus. The patient worked as a funeral director and had notable formaldehyde exposure. He also hunted wild game and performed taxidermy regularly.

The patient was admitted and treated with intravenous dexamethasone for a compromised airway. Subsequently, he was taken to the operating room and had biopsies performed of the posterior pharynx. Given his exposure history, the infectious disease department was consulted and he was evaluated for multiple viral, bacterial, and fungal suspects including leishmania and tularemia. Age-appropriate screening, physical examination, and review of systems were negative for an underlying neoplasm. Histopathologic examination revealed a subepithelial vesicular mucositis with a mixed infiltrate of lymphocytes and histiocytes. Direct immunofluorescence microscopy demonstrated strong linear fluorescence along the epithelial-subepithelial junction with IgG and C3. Based on these findings, the diagnosis of MMP was made.

Further testing for bullous pemphigoid antigen 1 (BP230) and bullous pemphigoid antigen 2 (BP180) were negative. On one occasion the patient tested positive for anti-BP230 IgG, but it was at a level judged to be insignificant (7.5 [reference range, <9]). The patient also was negative for autoantibodies against desmoglein 1 and 3. Indirect immunofluorescence using rat bladder epithelium was not performed.

The patient was started on methotrexate and oral prednisone by the rheumatology department, but after 1 week, he presented in respiratory distress and was taken for an emergency tracheostomy. The patient eventually was referred to the dermatology department where methotrexate was discontinued and the patient was started on titrating doses of prednisone and mycophenolate mofetil. Eight weeks later, the patient became completely aphonic and was taken by ENT for dilation of the supraglottic, glottic, and subglottic stenosis with mucosal triamcinolone injections. Doxycycline 100 mg twice daily and nicotinamide 500 mg twice daily was initiated in addition to mycophenolate mofetil 3 g and prednisone 80 mg, but again the patient developed near-complete tracheal stenosis just proximal to the tracheostomy entry site. At 16 weeks, balloon dilation was repeated with dexamethasone injections and topical mitomycin C. Subsequently, the patient regained some use of his voice. Although the next several laryngoscopes showed improvement in the patient’s epiglottis and glottis, the trachea continued to require debridement and dilation.

Despite maximal medical therapy and surgical interventions, the patient had little improvement in his voice and large clots of blood obstructed his tracheostomy daily. He was unable to sleep in his preferred position on the stomach (prone) due to dyspnea but had less distress sleeping on his back (supine). The patient was referred to the pulmonology department for an endotracheobronchoscopy to further evaluate the airway. It was discovered that the mucosa of the trachea from the level of the tracheostomy to the carina was friable with active erosions and thick bloody secretions (Figure 1). Lesions extended as far as the scope was able to visualize to the left upper lobe takeoff and the right mainstem bronchus (Figure 2). Biopsies of the carinal mucosa showed 3+/3+ linear fluorescence with IgG along the dermoepidermal junction. Salt-split studies were performed, but because the specimen was fragmented, it was not possible to assess if the fluorescence was present at the floor or at the roof of the split.

Given the severity of disease and failure to respond to other aggressive immunosuppressive therapies as well as having been with a tracheostomy for 22 months, the patient was started on 2 doses of intravenous rituximab 1 g 2 weeks apart along with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (3 times weekly) for pneumocystis pneumonia prophylaxis. No complications were observed during infusions. After 2 rituximab infusions, he was weaned off of prednisone and a repeat bronchoscopy showed no airway ulcers beyond the distal trachea or endobronchial obstruction. However, the subglottic space and area above the tracheostomy showed remarkable stenosis with a cobblestone pattern and granulation tissue with continued narrowing of the subglottic area. The ENT performed further dilation and after 34 months, the tracheostomy was removed and a T-tube was placed. The patient required cleaning out of the T-tube approximately every 3 months, and after 2 years the original T-tube was replaced with a new one. At the time of this report, the ENT recommended removing the T-tube, but the patient was reluctant to do so; therefore, a second T-tube replacement is planned. He continues to do well without relapse and has been off all medical therapy for nearly 4 years.

Mucous membrane pemphigoid is an acquired autoimmune subepithelial blistering disease that predominantly affects mucous membranes with or without skin involvement. This condition has been referred to as cicatricial pemphigoid, oral pemphigoid, and ocular cicatricial pemphigoid, among other names. It is characterized by linear deposition of IgG, IgA, or C3 along the epithelial basement membrane zone. According to the international consensus on MMP, the target antigens identified in the epithelial basement membrane zone include bullous pemphigoid antigen 1 (BP230), bullous pemphigoid antigen 2 (BP180), laminin 5 (α3, β3, γ2 chains), laminin 6 (α3 chain), type VII collagen, and integrin β4 subunit.3 Not all patients with MMP will have circulating autoantibodies to the above components, and although our patient did have detectable anti-BP230 IgG, it was not considered clinically significant. Furthermore, the type of autoantibody does not impact decisions regarding therapy selection.3

Although rare, MMP is well-known to dermatologists and ophthalmologists who manage a large majority of MMP patients depending on which mucosa is involved. Mucous membrane pemphigoid is extremely rare in the lower respiratory tract, and when these lesions are discovered, it often is in the face of life-threatening respiratory distress. Mucous membrane pemphigoid is a challenging disease to treat, even more so when the primary specialty physician is unable to visualize the affected areas. Our patient’s disease was limited primarily to the pharynx, larynx, trachea, and bronchi with few oral lesions. According to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms mucous membrane pemphigus, cicatricial pemphigoid, trachea, bronchus, and fatal, 8 reports (7 case reports and 1 prospective study) of MMP involving the lower respiratory tract have been published.4-11 Of the case reports, each patient also presented with involvement of the eyes or skin.4,5,7-11 Four of these cases were fatal secondary to cardiopulmonary arrest.5,7,9,10 In the prospective study, 110 consecutive patients with clinical, histologic, and immunologic criteria of MMP were examined with a flexible nasopharyngolaryngoscope.6 Thirty-eight patients had nose or throat symptoms but only 10 had laryngeal involvement and 5 had acute dyspnea. The nasal valves, choanae, pharynx, and/or larynx were severely scarred in 7 patients, which was fatal in 3.6

Medical treatment should be based on the following factors of the patient’s disease: site, severity, and rapidity of progression.3 High-risk patients can be defined as those who have lesions at any of the following sites: ocular, genital, nasopharyngeal, esophageal, and laryngeal mucosae. As our patient had involvement at several high-risk sites, in particular sites only visualized by various scoping procedures, a team of physicians including dermatologists, ENT physicians, pulmonologists, and oncologists was necessary to facilitate his care. Scarring is the hallmark of MMP and prevention of scarring is the most important aspect of treatment of MMP. Surgical repair of the previously involved mucosa is difficult, as the tissue is prone to re-scarring and difficult to heal. Over the last several years, there has been increasing evidence for the use of rituximab in autoimmune bullous skin diseases including pemphigus vulgaris, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, and MMP.12-14 After 2 infusions of rituximab, our patient had clearance of his disease and currently is doing well with a T-tube.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kim Yancey, MD (Dallas, Texas), for providing access to the patient’s diagnostic laboratory immunology and reviewing biopsy specimens; Luis Angel, MD (San Antonio, Texas), for providing bronchoscopy photographs; and C. Blake Simpson, MD (San Antonio, Texas), for co-managing this challenging case.

To the Editor:

Mucous membrane pemphigoid (MMP) is an autoimmune blistering disorder that causes subepithelial damage and scarring of mucosal surfaces with or without skin involvement.1 The clinical presentation is highly variable. The oropharynx is the most common site of initial presentation, followed by ocular, nasopharyngeal, anogenital, skin, laryngeal, and esophageal involvement.2 Patients often present to a variety of specialists depending on initial symptoms, and due to the diverse clinical manifestations, MMP often is misdiagnosed. Our patient presented an even greater challenge because the disease progressed to tracheal and bronchial involvement.

A 37-year-old man presented to his primary care physician with a chief concern of a sore throat and oral ulcers. The patient was treated with a course of antibiotics followed by a nystatin oral solution. He continued to develop ulcerative lesions on the soft palate, posterior pharynx, and nasal mucosae. He sought treatment from 2 otolaryngologists (ENTs) and a gastroenterologist, and continued to be treated with multiple oral antibiotics, fluconazole, and topical nystatin. Despite treatment, the patient developed pansinusitis and laryngitis and presented to the ENT department at our institution with severe hoarseness and dyspnea on exertion. Examination by the ENT department revealed ulcerative lesions of the nares with stenosis and ulcers along the soft palate. Videolaryngostroboscopy showed remarkable supraglottic edema with thick endolaryngeal mucus. The patient worked as a funeral director and had notable formaldehyde exposure. He also hunted wild game and performed taxidermy regularly.

The patient was admitted and treated with intravenous dexamethasone for a compromised airway. Subsequently, he was taken to the operating room and had biopsies performed of the posterior pharynx. Given his exposure history, the infectious disease department was consulted and he was evaluated for multiple viral, bacterial, and fungal suspects including leishmania and tularemia. Age-appropriate screening, physical examination, and review of systems were negative for an underlying neoplasm. Histopathologic examination revealed a subepithelial vesicular mucositis with a mixed infiltrate of lymphocytes and histiocytes. Direct immunofluorescence microscopy demonstrated strong linear fluorescence along the epithelial-subepithelial junction with IgG and C3. Based on these findings, the diagnosis of MMP was made.

Further testing for bullous pemphigoid antigen 1 (BP230) and bullous pemphigoid antigen 2 (BP180) were negative. On one occasion the patient tested positive for anti-BP230 IgG, but it was at a level judged to be insignificant (7.5 [reference range, <9]). The patient also was negative for autoantibodies against desmoglein 1 and 3. Indirect immunofluorescence using rat bladder epithelium was not performed.

The patient was started on methotrexate and oral prednisone by the rheumatology department, but after 1 week, he presented in respiratory distress and was taken for an emergency tracheostomy. The patient eventually was referred to the dermatology department where methotrexate was discontinued and the patient was started on titrating doses of prednisone and mycophenolate mofetil. Eight weeks later, the patient became completely aphonic and was taken by ENT for dilation of the supraglottic, glottic, and subglottic stenosis with mucosal triamcinolone injections. Doxycycline 100 mg twice daily and nicotinamide 500 mg twice daily was initiated in addition to mycophenolate mofetil 3 g and prednisone 80 mg, but again the patient developed near-complete tracheal stenosis just proximal to the tracheostomy entry site. At 16 weeks, balloon dilation was repeated with dexamethasone injections and topical mitomycin C. Subsequently, the patient regained some use of his voice. Although the next several laryngoscopes showed improvement in the patient’s epiglottis and glottis, the trachea continued to require debridement and dilation.

Despite maximal medical therapy and surgical interventions, the patient had little improvement in his voice and large clots of blood obstructed his tracheostomy daily. He was unable to sleep in his preferred position on the stomach (prone) due to dyspnea but had less distress sleeping on his back (supine). The patient was referred to the pulmonology department for an endotracheobronchoscopy to further evaluate the airway. It was discovered that the mucosa of the trachea from the level of the tracheostomy to the carina was friable with active erosions and thick bloody secretions (Figure 1). Lesions extended as far as the scope was able to visualize to the left upper lobe takeoff and the right mainstem bronchus (Figure 2). Biopsies of the carinal mucosa showed 3+/3+ linear fluorescence with IgG along the dermoepidermal junction. Salt-split studies were performed, but because the specimen was fragmented, it was not possible to assess if the fluorescence was present at the floor or at the roof of the split.