User login

A skin lesion after cardiac catheterization

A 64-year-old man with diabetes and hypertension presented with a 2-day history of sudden onset of acute pain and cyanosis on the sole of his right foot 4 days after undergoing cardiac catheterization and coronary angiography.

A few days later, the patient returned with abdominal pain, diarrhea, and acute renal injury with urinary eosinophils (7% of the white blood cells in the urine) and proteinuria.

Q: Which is the most likely diagnosis?

- Infective endocarditis

- Pernio (chilblain)

- Cholesterol crystal embolism

- Cutaneous small-vessel vasculitis

A: Cholesterol crystal embolism is the correct diagnosis.

Infective endocarditis is an infection of the endocardium, but systemic signs may be present, including cutaneous lesions such as Osler nodes (painful papules on the tips of the fingers and toes) and Janeway lesions (painless macules on the palms and soles). Histologic staining of skin biopsy specimens often shows vasculitis, occasionally with a positive Gram stain. Severe renal injury is not common, and the timing of the acute illness and skin lesion fits better with an acute embolic phenomenon.

Pernio is a form of cold injury, localized in peripheral parts of the body and occurring after exposure to cold temperatures in damp conditions. It usually manifests bilaterally as painful erythematous or purple lesions on the acral areas of the hands and feet, nose, ears, and, rarely, the thighs and buttocks. Pernio most commonly affects women between 20 and 40 years of age. It can be idiopathic or associated with a systemic disease such as systemic lupus erythematosus or Sjögren syndrome.

Cutaneous small-vessel vasculitis is a heterogeneous group of disorders with inflammation and damage of the blood vessels; it may be limited to the skin or it may involve multiple systems. Palpable or nonpalpable purpura and ulceration are common clinical findings, and histologic study shows an inflammatory infiltrate of vessel walls, fibrinoid necrosis, thrombosis, and extravasation of red blood cells.

While this patient’s problems are not consistent with small-vessel vasculitis, the single skin lesion, the timing after the catheterization, and the urinary eosinophils are best explained by cholesterol embolization.

CHOLESTEROL CRYSTAL EMBOLISM

Cholesterol crystal embolism is commonly iatrogenic, a complication of mechanical damage to the arterial walls from vascular surgery or invasive percutaneous procedures. Material dislodged from atheromatous arterial plaques can occlude the small vessels of the feet, producing this syndrome.

The onset of the clinical disease is often delayed for days to weeks after an angiographic procedure.1 Spontaneous hemorrhage, disruption of plaque, or drug therapy with an anticoagulant or a fibrinolytic can precipitate embolization of cholesterol crystals. The source of the emboli is atheromatous plaque in major blood vessels, particularly the abdominal aorta.

Many organs and systems can be affected

These emboli can affect many organs and systems: eg, the kidneys (causing hypertension and acute renal failure), the muscles (causing myalgias), gastrointestinal organs (causing bleeding, abdominal pain, and bowel infarction), the lungs (causing acute respiratory distress syndrome), the eyes (causing Hollenhorst plaques in retinal arteries), and the central nervous system (causing stroke, confusion, and delirium). Cardiac or central nervous system involvement is associated with a high risk of death.

After angiography, clinical manifestations of cholesterol embolization have been reported in 0.06% to 1.4% of patients,2,3 although the finding of cholesterol emboli is more common in autopsy studies.4

Recognizing skin signs is the key

Cutaneous abnormalities are usually the earliest and often the only clinical manifestation of this syndrome. Findings on the lower limbs include blue toes, cutaneous nodules, and livedo reticularis, affecting the feet and legs and sometimes extending upward to the trunk. Other findings include digital infarcts, ulceration, gangrene, purpura, cyanosis, and splinter hemorrhages in the nail bed.

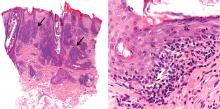

In our patient, microscopic study of skin biopsy specimens showed needle-shaped clefts within the lumen of blood vessels—ie, dissolved cholesterol crystals obstructing small arteries (Figure 2).

Biopsy studies of skin lesions are positive in a high percentage of cases, showing dissolved cholesterol crystals within the lumen of blood vessels, especially in the small to large arteries and arterioles of the deep dermis or subcutaneous fat. Deep biopsies and carefully examination are necessary, as emboli tend to be patchily distributed. Early recognition of cutaneous clinical findings is essential to establish the proper diagnosis and treatment.

The diagnostic triad of this disease includes blue toe syndrome, acute or subacute renal failure, and a temporal relation with an inciting event (particularly angiography). But despite these diagnostic criteria,2 the diagnosis is often based on a combination of signs and symptoms specific to end-organ damage and a systemic inflammatory response.3

Histologic confirmation is considered essential to the diagnosis of cholesterol crystal embolism, and as the skin is the most accessible site, skin biopsy provides the best sample for histologic diagnosis.5

Postprocedural embolism of a blood clot, vasculitis, and infective endocarditis are the most important differential diagnoses.6,7

Treatment is supportive, preventive

Treatment is mainly supportive with hemodynamic monitoring, nutritional and metabolic support, mechanical ventilation, and dialysis if necessary. The underlying atherosclerotic disease should be treated aggressively. Prevention of another episode involves modification of traditional risk factors such as serum cholesterol, diabetes, hypertension, and smoking. Additional vascular surgery procedures should be avoided, as they can induce new episodes.

- Donohue KG, Saap L, Falanga V. Cholesterol crystal embolization: an atherosclerotic disease with frequent and varied cutaneous manifestations. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2003; 17:504–511.

- Fukumoto Y, Tsutsui H, Tsuchihashi M, Masumoto A, Takeshita A; Cholesterol Embolism Study (CHEST) Investigators. The incidence and risk factors of cholesterol embolization syndrome, a complication of cardiac catheterization: a prospective study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003; 42:211–216.

- Johnson LW, Esente P, Giambartolomei A, et al. Peripheral vascular complications of coronary angioplasty by the femoral and brachial techniques. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn 1994; 31:165–172.

- Kronzon I, Saric M. Cholesterol embolization syndrome. Circulation 2010; 122:631–641.

- Jucgla A, Moreso F, Muniesa C, Moreno A, Vidaller A. Cholesterol embolism: still an unrecognized entity with a high mortality rate. J Am Acad Dermatol 2006; 55:786–793.

- Maki T, Izumi C, Miyake M, et al. Cholesterol embolism after cardiac catheterization mimicking infective endocarditis. Intern Med 2005; 44:1060–1063.

- Arias-Santiago S, Aneiros-Fernández J, Girón-Prieto MS, Fernández-Pugnaire MA, Naranjo-Sintes R. Palpable purpura. Cleve Clin J Med 2010; 77:205–206.

A 64-year-old man with diabetes and hypertension presented with a 2-day history of sudden onset of acute pain and cyanosis on the sole of his right foot 4 days after undergoing cardiac catheterization and coronary angiography.

A few days later, the patient returned with abdominal pain, diarrhea, and acute renal injury with urinary eosinophils (7% of the white blood cells in the urine) and proteinuria.

Q: Which is the most likely diagnosis?

- Infective endocarditis

- Pernio (chilblain)

- Cholesterol crystal embolism

- Cutaneous small-vessel vasculitis

A: Cholesterol crystal embolism is the correct diagnosis.

Infective endocarditis is an infection of the endocardium, but systemic signs may be present, including cutaneous lesions such as Osler nodes (painful papules on the tips of the fingers and toes) and Janeway lesions (painless macules on the palms and soles). Histologic staining of skin biopsy specimens often shows vasculitis, occasionally with a positive Gram stain. Severe renal injury is not common, and the timing of the acute illness and skin lesion fits better with an acute embolic phenomenon.

Pernio is a form of cold injury, localized in peripheral parts of the body and occurring after exposure to cold temperatures in damp conditions. It usually manifests bilaterally as painful erythematous or purple lesions on the acral areas of the hands and feet, nose, ears, and, rarely, the thighs and buttocks. Pernio most commonly affects women between 20 and 40 years of age. It can be idiopathic or associated with a systemic disease such as systemic lupus erythematosus or Sjögren syndrome.

Cutaneous small-vessel vasculitis is a heterogeneous group of disorders with inflammation and damage of the blood vessels; it may be limited to the skin or it may involve multiple systems. Palpable or nonpalpable purpura and ulceration are common clinical findings, and histologic study shows an inflammatory infiltrate of vessel walls, fibrinoid necrosis, thrombosis, and extravasation of red blood cells.

While this patient’s problems are not consistent with small-vessel vasculitis, the single skin lesion, the timing after the catheterization, and the urinary eosinophils are best explained by cholesterol embolization.

CHOLESTEROL CRYSTAL EMBOLISM

Cholesterol crystal embolism is commonly iatrogenic, a complication of mechanical damage to the arterial walls from vascular surgery or invasive percutaneous procedures. Material dislodged from atheromatous arterial plaques can occlude the small vessels of the feet, producing this syndrome.

The onset of the clinical disease is often delayed for days to weeks after an angiographic procedure.1 Spontaneous hemorrhage, disruption of plaque, or drug therapy with an anticoagulant or a fibrinolytic can precipitate embolization of cholesterol crystals. The source of the emboli is atheromatous plaque in major blood vessels, particularly the abdominal aorta.

Many organs and systems can be affected

These emboli can affect many organs and systems: eg, the kidneys (causing hypertension and acute renal failure), the muscles (causing myalgias), gastrointestinal organs (causing bleeding, abdominal pain, and bowel infarction), the lungs (causing acute respiratory distress syndrome), the eyes (causing Hollenhorst plaques in retinal arteries), and the central nervous system (causing stroke, confusion, and delirium). Cardiac or central nervous system involvement is associated with a high risk of death.

After angiography, clinical manifestations of cholesterol embolization have been reported in 0.06% to 1.4% of patients,2,3 although the finding of cholesterol emboli is more common in autopsy studies.4

Recognizing skin signs is the key

Cutaneous abnormalities are usually the earliest and often the only clinical manifestation of this syndrome. Findings on the lower limbs include blue toes, cutaneous nodules, and livedo reticularis, affecting the feet and legs and sometimes extending upward to the trunk. Other findings include digital infarcts, ulceration, gangrene, purpura, cyanosis, and splinter hemorrhages in the nail bed.

In our patient, microscopic study of skin biopsy specimens showed needle-shaped clefts within the lumen of blood vessels—ie, dissolved cholesterol crystals obstructing small arteries (Figure 2).

Biopsy studies of skin lesions are positive in a high percentage of cases, showing dissolved cholesterol crystals within the lumen of blood vessels, especially in the small to large arteries and arterioles of the deep dermis or subcutaneous fat. Deep biopsies and carefully examination are necessary, as emboli tend to be patchily distributed. Early recognition of cutaneous clinical findings is essential to establish the proper diagnosis and treatment.

The diagnostic triad of this disease includes blue toe syndrome, acute or subacute renal failure, and a temporal relation with an inciting event (particularly angiography). But despite these diagnostic criteria,2 the diagnosis is often based on a combination of signs and symptoms specific to end-organ damage and a systemic inflammatory response.3

Histologic confirmation is considered essential to the diagnosis of cholesterol crystal embolism, and as the skin is the most accessible site, skin biopsy provides the best sample for histologic diagnosis.5

Postprocedural embolism of a blood clot, vasculitis, and infective endocarditis are the most important differential diagnoses.6,7

Treatment is supportive, preventive

Treatment is mainly supportive with hemodynamic monitoring, nutritional and metabolic support, mechanical ventilation, and dialysis if necessary. The underlying atherosclerotic disease should be treated aggressively. Prevention of another episode involves modification of traditional risk factors such as serum cholesterol, diabetes, hypertension, and smoking. Additional vascular surgery procedures should be avoided, as they can induce new episodes.

A 64-year-old man with diabetes and hypertension presented with a 2-day history of sudden onset of acute pain and cyanosis on the sole of his right foot 4 days after undergoing cardiac catheterization and coronary angiography.

A few days later, the patient returned with abdominal pain, diarrhea, and acute renal injury with urinary eosinophils (7% of the white blood cells in the urine) and proteinuria.

Q: Which is the most likely diagnosis?

- Infective endocarditis

- Pernio (chilblain)

- Cholesterol crystal embolism

- Cutaneous small-vessel vasculitis

A: Cholesterol crystal embolism is the correct diagnosis.

Infective endocarditis is an infection of the endocardium, but systemic signs may be present, including cutaneous lesions such as Osler nodes (painful papules on the tips of the fingers and toes) and Janeway lesions (painless macules on the palms and soles). Histologic staining of skin biopsy specimens often shows vasculitis, occasionally with a positive Gram stain. Severe renal injury is not common, and the timing of the acute illness and skin lesion fits better with an acute embolic phenomenon.

Pernio is a form of cold injury, localized in peripheral parts of the body and occurring after exposure to cold temperatures in damp conditions. It usually manifests bilaterally as painful erythematous or purple lesions on the acral areas of the hands and feet, nose, ears, and, rarely, the thighs and buttocks. Pernio most commonly affects women between 20 and 40 years of age. It can be idiopathic or associated with a systemic disease such as systemic lupus erythematosus or Sjögren syndrome.

Cutaneous small-vessel vasculitis is a heterogeneous group of disorders with inflammation and damage of the blood vessels; it may be limited to the skin or it may involve multiple systems. Palpable or nonpalpable purpura and ulceration are common clinical findings, and histologic study shows an inflammatory infiltrate of vessel walls, fibrinoid necrosis, thrombosis, and extravasation of red blood cells.

While this patient’s problems are not consistent with small-vessel vasculitis, the single skin lesion, the timing after the catheterization, and the urinary eosinophils are best explained by cholesterol embolization.

CHOLESTEROL CRYSTAL EMBOLISM

Cholesterol crystal embolism is commonly iatrogenic, a complication of mechanical damage to the arterial walls from vascular surgery or invasive percutaneous procedures. Material dislodged from atheromatous arterial plaques can occlude the small vessels of the feet, producing this syndrome.

The onset of the clinical disease is often delayed for days to weeks after an angiographic procedure.1 Spontaneous hemorrhage, disruption of plaque, or drug therapy with an anticoagulant or a fibrinolytic can precipitate embolization of cholesterol crystals. The source of the emboli is atheromatous plaque in major blood vessels, particularly the abdominal aorta.

Many organs and systems can be affected

These emboli can affect many organs and systems: eg, the kidneys (causing hypertension and acute renal failure), the muscles (causing myalgias), gastrointestinal organs (causing bleeding, abdominal pain, and bowel infarction), the lungs (causing acute respiratory distress syndrome), the eyes (causing Hollenhorst plaques in retinal arteries), and the central nervous system (causing stroke, confusion, and delirium). Cardiac or central nervous system involvement is associated with a high risk of death.

After angiography, clinical manifestations of cholesterol embolization have been reported in 0.06% to 1.4% of patients,2,3 although the finding of cholesterol emboli is more common in autopsy studies.4

Recognizing skin signs is the key

Cutaneous abnormalities are usually the earliest and often the only clinical manifestation of this syndrome. Findings on the lower limbs include blue toes, cutaneous nodules, and livedo reticularis, affecting the feet and legs and sometimes extending upward to the trunk. Other findings include digital infarcts, ulceration, gangrene, purpura, cyanosis, and splinter hemorrhages in the nail bed.

In our patient, microscopic study of skin biopsy specimens showed needle-shaped clefts within the lumen of blood vessels—ie, dissolved cholesterol crystals obstructing small arteries (Figure 2).

Biopsy studies of skin lesions are positive in a high percentage of cases, showing dissolved cholesterol crystals within the lumen of blood vessels, especially in the small to large arteries and arterioles of the deep dermis or subcutaneous fat. Deep biopsies and carefully examination are necessary, as emboli tend to be patchily distributed. Early recognition of cutaneous clinical findings is essential to establish the proper diagnosis and treatment.

The diagnostic triad of this disease includes blue toe syndrome, acute or subacute renal failure, and a temporal relation with an inciting event (particularly angiography). But despite these diagnostic criteria,2 the diagnosis is often based on a combination of signs and symptoms specific to end-organ damage and a systemic inflammatory response.3

Histologic confirmation is considered essential to the diagnosis of cholesterol crystal embolism, and as the skin is the most accessible site, skin biopsy provides the best sample for histologic diagnosis.5

Postprocedural embolism of a blood clot, vasculitis, and infective endocarditis are the most important differential diagnoses.6,7

Treatment is supportive, preventive

Treatment is mainly supportive with hemodynamic monitoring, nutritional and metabolic support, mechanical ventilation, and dialysis if necessary. The underlying atherosclerotic disease should be treated aggressively. Prevention of another episode involves modification of traditional risk factors such as serum cholesterol, diabetes, hypertension, and smoking. Additional vascular surgery procedures should be avoided, as they can induce new episodes.

- Donohue KG, Saap L, Falanga V. Cholesterol crystal embolization: an atherosclerotic disease with frequent and varied cutaneous manifestations. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2003; 17:504–511.

- Fukumoto Y, Tsutsui H, Tsuchihashi M, Masumoto A, Takeshita A; Cholesterol Embolism Study (CHEST) Investigators. The incidence and risk factors of cholesterol embolization syndrome, a complication of cardiac catheterization: a prospective study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003; 42:211–216.

- Johnson LW, Esente P, Giambartolomei A, et al. Peripheral vascular complications of coronary angioplasty by the femoral and brachial techniques. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn 1994; 31:165–172.

- Kronzon I, Saric M. Cholesterol embolization syndrome. Circulation 2010; 122:631–641.

- Jucgla A, Moreso F, Muniesa C, Moreno A, Vidaller A. Cholesterol embolism: still an unrecognized entity with a high mortality rate. J Am Acad Dermatol 2006; 55:786–793.

- Maki T, Izumi C, Miyake M, et al. Cholesterol embolism after cardiac catheterization mimicking infective endocarditis. Intern Med 2005; 44:1060–1063.

- Arias-Santiago S, Aneiros-Fernández J, Girón-Prieto MS, Fernández-Pugnaire MA, Naranjo-Sintes R. Palpable purpura. Cleve Clin J Med 2010; 77:205–206.

- Donohue KG, Saap L, Falanga V. Cholesterol crystal embolization: an atherosclerotic disease with frequent and varied cutaneous manifestations. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2003; 17:504–511.

- Fukumoto Y, Tsutsui H, Tsuchihashi M, Masumoto A, Takeshita A; Cholesterol Embolism Study (CHEST) Investigators. The incidence and risk factors of cholesterol embolization syndrome, a complication of cardiac catheterization: a prospective study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003; 42:211–216.

- Johnson LW, Esente P, Giambartolomei A, et al. Peripheral vascular complications of coronary angioplasty by the femoral and brachial techniques. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn 1994; 31:165–172.

- Kronzon I, Saric M. Cholesterol embolization syndrome. Circulation 2010; 122:631–641.

- Jucgla A, Moreso F, Muniesa C, Moreno A, Vidaller A. Cholesterol embolism: still an unrecognized entity with a high mortality rate. J Am Acad Dermatol 2006; 55:786–793.

- Maki T, Izumi C, Miyake M, et al. Cholesterol embolism after cardiac catheterization mimicking infective endocarditis. Intern Med 2005; 44:1060–1063.

- Arias-Santiago S, Aneiros-Fernández J, Girón-Prieto MS, Fernández-Pugnaire MA, Naranjo-Sintes R. Palpable purpura. Cleve Clin J Med 2010; 77:205–206.

An erythematous plaque on the nose

A 38-year-old woman presented with a pruriginous and erythematous lesion on her nose that appeared during periods of cold weather. She said she is completely asymptomatic during the summer months.

Q: What is the most likely diagnosis?

- Lupus pernio

- Rosacea

- Seborrheic dermatitis

- Chilblain lupus erythematosus

- Lupus vulgaris

A: The diagnosis is chilblain lupus erythematosus.

The differential diagnosis of an erythematous lesion on the nose of a middle-aged woman also includes rosacea, lupus pernio, lupus vulgaris, and seborrheic dermatitis. Some of these lesions are exacerbated by cold. Usually, the diagnosis is based on clinical findings, but in some cases histologic features on biopsy study confirm the diagnosis.

Lesions of lupus pernio (sarcoidosis) remain unaltered with changes in temperature, and biopsy study usually shows granulomas without caseous necrosis with little inflammatory infiltrate at the periphery.

Rosacea usually gets worse with heat and with alcohol consumption, although it can be exacerbated by cold. Biopsy study shows a nonspecific perivascular and perifollicular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate accompanied occasionally by multinucleated cells.

Seborrheic dermatitis is a papulosquamous disorder characterized by greasy scaling over inflamed skin on the scalp, face, and trunk. Disease activity is increased in winter and spring, with remissions commonly occurring in summer. The histologic features of seborrheic dermatitis are nonspecific; in this case, the histologic features were compatible with chilblain lupus without changes of seborrheic dermatitis.

Lupus vulgaris is a chronic form of cutaneous tuberculosis characterized by redbrown papules with central atrophy. The nose and ears are usually affected. Histologically, granulomatous tubercles with epithelioid cells and caseation necrosis are usually found.

CHILBLAIN LUPUS ERYTHEMATOSUS

Pernio, or chilblain, is a localized inflammatory lesion of the skin resulting from an abnormal response to cold.1 The cutaneous lesions of chilblain may be classified as idiopathic, autoimmune-related (as in systemic lupus erythematosus, subacute cutaneous lupus), and induced by drugs such as terbinafine (Lamisil)2 or infliximab (Remicade).,3

Chilblain lupus is a rare form of cutaneous lupus erythematosus and should not be confused with lupus pernio, which is a misleading name used for a type of cutaneous sarcoidosis.4

Chilblain lupus is characterized by reddish-purple plaques in acral areas (more often the hands and feet, but also the nose and ears) that are induced by exposure to cold—unlike other lesions of lupus erythematosus, which worsen with exposure to sunlight. The main difference from the cutaneous variety of sarcoidosis (lupus pernio) is the histopathologic appearance. In patients with chilblain lupus, epidermal atrophy, perivascular and periadnexal inflammatory infiltrates, and degeneration of the basal layer are found, whereas in lupus pernio (sarcoidosis), we observe granulomas without caseous necrosis, but with few inflammatory infiltrates on the periphery.

PROPOSED DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA

Su et al5 have proposed diagnostic criteria for chilblain lupus. Their two major criteria are skin lesions in acral locations induced by exposure to cold or a drop in temperature, and evidence of lupus erythematosus in the skin lesions by histopathologic examination or immunofluorescence study. Both of these criteria must be met, plus one of three minor criteria: the coexistence of systemic lupus erythematosus or of skin lesions of discoid lupus erythematosus; response to lupus therapy; and negative results of testing for cryoglobulin and cold agglutinins.

CHILBLAIN LUPUS VS SYSTEMIC LUPUS

Chilblain lupus is an uncommon manifestation of systemic lupus erythematosus, and it is reported to occur in about 20% of patients with that condition.6 Often, the onset of chilblain lupus precedes the systemic disease. Patients with systemic lupus erythematosus and chilblain lupus do not usually present with renal disease, mucosal lesions, or central nervous system involvement. However, Raynaud phenomenon and photosensitivity have been reported to be more frequently associated with chilblain lupus.7

A disorder of peripheral circulation could be involved in the pathogenesis of chilblain lupus, and the association with Raynaud phenomenon, livedo reticularis, antiphospholipid syndrome, and changes in nailfold capillaries supports this hypothesis. Antinuclear antibody and anti-Ro/SS-A antibody are commonly detected in the serum of patients with chilblain lupus, and anti-Ro/SS-A antibody seems to be a major serologic marker of chilblain lupus in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus.7

TREATMENT

Protection from cold by physical measures is very important, as well as the use of topical or oral antibiotics if the lesions are infected. In severe cases unresponsive to topical corticosteroids, a calcium channel blocker is a good therapeutic option; antimalarials, commonly used in the treatment of lupus erythematosus, can also have a positive effect in patients with chilblain lupus.

CASE CONCLUDED

Our patient was advised to protect herself from the cold. Topical corticosteroids and oral hydroxychloroquine (200 mg/day) were prescribed, and they produced a good response. In severe cases, oral corticosteroids, etretinate (Tegison), mycophenolate (CellCept), or thalidomide (Thalomid) may be used.8

- Simon TD, Soep JB, Hollister JR. Pernio in pediatrics. Pediatrics 2005; 116:e472–e475.

- Bonsmann G, Schiller M, Luger TA, Ständer S. Terbinafine-induced subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. J Am Acad Dermatol 2001; 44:925–931.

- Richez C, Dumoulin C, Schaeverbeke T. Infliximab induced chilblain lupus in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 2005; 32:760–761.

- Arias-Santiago SA, Girón-Prieto MS, Callejas-Rubio JL, Fernández-Pugnaire MA, Ortego-Centeno N. Lupus pernio or chilblain lupus?: two different entities. Chest 2009; 136:946–947.

- Su WP, Perniciaro C, Rogers RS, White JW. Chilblain lupus erythematosus (lupus pernio): clinical review of the Mayo Clinic experience and proposal of diagnostic criteria. Cutis 1994; 54:395–399.

- Yell JA, Mbuagbaw J, Burge SM. Cutaneous manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus. Br J Dermatol 1996; 135:355–362.

- Franceschini F, Calzavara-Pinton P, Quinzanini M, et al. Chilblain lupus erythematosus is associated with antibodies to SSA/Ro. Lupus 1999; 8:215–219.

- Bouaziz JD, Barete S, Le Pelletier F, Amoura Z, Piette JC, Francès C. Cutaneous lesions of the digits in systemic lupus erythematosus: 50 cases. Lupus 2007; 16:163–167.

A 38-year-old woman presented with a pruriginous and erythematous lesion on her nose that appeared during periods of cold weather. She said she is completely asymptomatic during the summer months.

Q: What is the most likely diagnosis?

- Lupus pernio

- Rosacea

- Seborrheic dermatitis

- Chilblain lupus erythematosus

- Lupus vulgaris

A: The diagnosis is chilblain lupus erythematosus.

The differential diagnosis of an erythematous lesion on the nose of a middle-aged woman also includes rosacea, lupus pernio, lupus vulgaris, and seborrheic dermatitis. Some of these lesions are exacerbated by cold. Usually, the diagnosis is based on clinical findings, but in some cases histologic features on biopsy study confirm the diagnosis.

Lesions of lupus pernio (sarcoidosis) remain unaltered with changes in temperature, and biopsy study usually shows granulomas without caseous necrosis with little inflammatory infiltrate at the periphery.

Rosacea usually gets worse with heat and with alcohol consumption, although it can be exacerbated by cold. Biopsy study shows a nonspecific perivascular and perifollicular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate accompanied occasionally by multinucleated cells.

Seborrheic dermatitis is a papulosquamous disorder characterized by greasy scaling over inflamed skin on the scalp, face, and trunk. Disease activity is increased in winter and spring, with remissions commonly occurring in summer. The histologic features of seborrheic dermatitis are nonspecific; in this case, the histologic features were compatible with chilblain lupus without changes of seborrheic dermatitis.

Lupus vulgaris is a chronic form of cutaneous tuberculosis characterized by redbrown papules with central atrophy. The nose and ears are usually affected. Histologically, granulomatous tubercles with epithelioid cells and caseation necrosis are usually found.

CHILBLAIN LUPUS ERYTHEMATOSUS

Pernio, or chilblain, is a localized inflammatory lesion of the skin resulting from an abnormal response to cold.1 The cutaneous lesions of chilblain may be classified as idiopathic, autoimmune-related (as in systemic lupus erythematosus, subacute cutaneous lupus), and induced by drugs such as terbinafine (Lamisil)2 or infliximab (Remicade).,3

Chilblain lupus is a rare form of cutaneous lupus erythematosus and should not be confused with lupus pernio, which is a misleading name used for a type of cutaneous sarcoidosis.4

Chilblain lupus is characterized by reddish-purple plaques in acral areas (more often the hands and feet, but also the nose and ears) that are induced by exposure to cold—unlike other lesions of lupus erythematosus, which worsen with exposure to sunlight. The main difference from the cutaneous variety of sarcoidosis (lupus pernio) is the histopathologic appearance. In patients with chilblain lupus, epidermal atrophy, perivascular and periadnexal inflammatory infiltrates, and degeneration of the basal layer are found, whereas in lupus pernio (sarcoidosis), we observe granulomas without caseous necrosis, but with few inflammatory infiltrates on the periphery.

PROPOSED DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA

Su et al5 have proposed diagnostic criteria for chilblain lupus. Their two major criteria are skin lesions in acral locations induced by exposure to cold or a drop in temperature, and evidence of lupus erythematosus in the skin lesions by histopathologic examination or immunofluorescence study. Both of these criteria must be met, plus one of three minor criteria: the coexistence of systemic lupus erythematosus or of skin lesions of discoid lupus erythematosus; response to lupus therapy; and negative results of testing for cryoglobulin and cold agglutinins.

CHILBLAIN LUPUS VS SYSTEMIC LUPUS

Chilblain lupus is an uncommon manifestation of systemic lupus erythematosus, and it is reported to occur in about 20% of patients with that condition.6 Often, the onset of chilblain lupus precedes the systemic disease. Patients with systemic lupus erythematosus and chilblain lupus do not usually present with renal disease, mucosal lesions, or central nervous system involvement. However, Raynaud phenomenon and photosensitivity have been reported to be more frequently associated with chilblain lupus.7

A disorder of peripheral circulation could be involved in the pathogenesis of chilblain lupus, and the association with Raynaud phenomenon, livedo reticularis, antiphospholipid syndrome, and changes in nailfold capillaries supports this hypothesis. Antinuclear antibody and anti-Ro/SS-A antibody are commonly detected in the serum of patients with chilblain lupus, and anti-Ro/SS-A antibody seems to be a major serologic marker of chilblain lupus in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus.7

TREATMENT

Protection from cold by physical measures is very important, as well as the use of topical or oral antibiotics if the lesions are infected. In severe cases unresponsive to topical corticosteroids, a calcium channel blocker is a good therapeutic option; antimalarials, commonly used in the treatment of lupus erythematosus, can also have a positive effect in patients with chilblain lupus.

CASE CONCLUDED

Our patient was advised to protect herself from the cold. Topical corticosteroids and oral hydroxychloroquine (200 mg/day) were prescribed, and they produced a good response. In severe cases, oral corticosteroids, etretinate (Tegison), mycophenolate (CellCept), or thalidomide (Thalomid) may be used.8

A 38-year-old woman presented with a pruriginous and erythematous lesion on her nose that appeared during periods of cold weather. She said she is completely asymptomatic during the summer months.

Q: What is the most likely diagnosis?

- Lupus pernio

- Rosacea

- Seborrheic dermatitis

- Chilblain lupus erythematosus

- Lupus vulgaris

A: The diagnosis is chilblain lupus erythematosus.

The differential diagnosis of an erythematous lesion on the nose of a middle-aged woman also includes rosacea, lupus pernio, lupus vulgaris, and seborrheic dermatitis. Some of these lesions are exacerbated by cold. Usually, the diagnosis is based on clinical findings, but in some cases histologic features on biopsy study confirm the diagnosis.

Lesions of lupus pernio (sarcoidosis) remain unaltered with changes in temperature, and biopsy study usually shows granulomas without caseous necrosis with little inflammatory infiltrate at the periphery.

Rosacea usually gets worse with heat and with alcohol consumption, although it can be exacerbated by cold. Biopsy study shows a nonspecific perivascular and perifollicular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate accompanied occasionally by multinucleated cells.

Seborrheic dermatitis is a papulosquamous disorder characterized by greasy scaling over inflamed skin on the scalp, face, and trunk. Disease activity is increased in winter and spring, with remissions commonly occurring in summer. The histologic features of seborrheic dermatitis are nonspecific; in this case, the histologic features were compatible with chilblain lupus without changes of seborrheic dermatitis.

Lupus vulgaris is a chronic form of cutaneous tuberculosis characterized by redbrown papules with central atrophy. The nose and ears are usually affected. Histologically, granulomatous tubercles with epithelioid cells and caseation necrosis are usually found.

CHILBLAIN LUPUS ERYTHEMATOSUS

Pernio, or chilblain, is a localized inflammatory lesion of the skin resulting from an abnormal response to cold.1 The cutaneous lesions of chilblain may be classified as idiopathic, autoimmune-related (as in systemic lupus erythematosus, subacute cutaneous lupus), and induced by drugs such as terbinafine (Lamisil)2 or infliximab (Remicade).,3

Chilblain lupus is a rare form of cutaneous lupus erythematosus and should not be confused with lupus pernio, which is a misleading name used for a type of cutaneous sarcoidosis.4

Chilblain lupus is characterized by reddish-purple plaques in acral areas (more often the hands and feet, but also the nose and ears) that are induced by exposure to cold—unlike other lesions of lupus erythematosus, which worsen with exposure to sunlight. The main difference from the cutaneous variety of sarcoidosis (lupus pernio) is the histopathologic appearance. In patients with chilblain lupus, epidermal atrophy, perivascular and periadnexal inflammatory infiltrates, and degeneration of the basal layer are found, whereas in lupus pernio (sarcoidosis), we observe granulomas without caseous necrosis, but with few inflammatory infiltrates on the periphery.

PROPOSED DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA

Su et al5 have proposed diagnostic criteria for chilblain lupus. Their two major criteria are skin lesions in acral locations induced by exposure to cold or a drop in temperature, and evidence of lupus erythematosus in the skin lesions by histopathologic examination or immunofluorescence study. Both of these criteria must be met, plus one of three minor criteria: the coexistence of systemic lupus erythematosus or of skin lesions of discoid lupus erythematosus; response to lupus therapy; and negative results of testing for cryoglobulin and cold agglutinins.

CHILBLAIN LUPUS VS SYSTEMIC LUPUS

Chilblain lupus is an uncommon manifestation of systemic lupus erythematosus, and it is reported to occur in about 20% of patients with that condition.6 Often, the onset of chilblain lupus precedes the systemic disease. Patients with systemic lupus erythematosus and chilblain lupus do not usually present with renal disease, mucosal lesions, or central nervous system involvement. However, Raynaud phenomenon and photosensitivity have been reported to be more frequently associated with chilblain lupus.7

A disorder of peripheral circulation could be involved in the pathogenesis of chilblain lupus, and the association with Raynaud phenomenon, livedo reticularis, antiphospholipid syndrome, and changes in nailfold capillaries supports this hypothesis. Antinuclear antibody and anti-Ro/SS-A antibody are commonly detected in the serum of patients with chilblain lupus, and anti-Ro/SS-A antibody seems to be a major serologic marker of chilblain lupus in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus.7

TREATMENT

Protection from cold by physical measures is very important, as well as the use of topical or oral antibiotics if the lesions are infected. In severe cases unresponsive to topical corticosteroids, a calcium channel blocker is a good therapeutic option; antimalarials, commonly used in the treatment of lupus erythematosus, can also have a positive effect in patients with chilblain lupus.

CASE CONCLUDED

Our patient was advised to protect herself from the cold. Topical corticosteroids and oral hydroxychloroquine (200 mg/day) were prescribed, and they produced a good response. In severe cases, oral corticosteroids, etretinate (Tegison), mycophenolate (CellCept), or thalidomide (Thalomid) may be used.8

- Simon TD, Soep JB, Hollister JR. Pernio in pediatrics. Pediatrics 2005; 116:e472–e475.

- Bonsmann G, Schiller M, Luger TA, Ständer S. Terbinafine-induced subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. J Am Acad Dermatol 2001; 44:925–931.

- Richez C, Dumoulin C, Schaeverbeke T. Infliximab induced chilblain lupus in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 2005; 32:760–761.

- Arias-Santiago SA, Girón-Prieto MS, Callejas-Rubio JL, Fernández-Pugnaire MA, Ortego-Centeno N. Lupus pernio or chilblain lupus?: two different entities. Chest 2009; 136:946–947.

- Su WP, Perniciaro C, Rogers RS, White JW. Chilblain lupus erythematosus (lupus pernio): clinical review of the Mayo Clinic experience and proposal of diagnostic criteria. Cutis 1994; 54:395–399.

- Yell JA, Mbuagbaw J, Burge SM. Cutaneous manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus. Br J Dermatol 1996; 135:355–362.

- Franceschini F, Calzavara-Pinton P, Quinzanini M, et al. Chilblain lupus erythematosus is associated with antibodies to SSA/Ro. Lupus 1999; 8:215–219.

- Bouaziz JD, Barete S, Le Pelletier F, Amoura Z, Piette JC, Francès C. Cutaneous lesions of the digits in systemic lupus erythematosus: 50 cases. Lupus 2007; 16:163–167.

- Simon TD, Soep JB, Hollister JR. Pernio in pediatrics. Pediatrics 2005; 116:e472–e475.

- Bonsmann G, Schiller M, Luger TA, Ständer S. Terbinafine-induced subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. J Am Acad Dermatol 2001; 44:925–931.

- Richez C, Dumoulin C, Schaeverbeke T. Infliximab induced chilblain lupus in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 2005; 32:760–761.

- Arias-Santiago SA, Girón-Prieto MS, Callejas-Rubio JL, Fernández-Pugnaire MA, Ortego-Centeno N. Lupus pernio or chilblain lupus?: two different entities. Chest 2009; 136:946–947.

- Su WP, Perniciaro C, Rogers RS, White JW. Chilblain lupus erythematosus (lupus pernio): clinical review of the Mayo Clinic experience and proposal of diagnostic criteria. Cutis 1994; 54:395–399.

- Yell JA, Mbuagbaw J, Burge SM. Cutaneous manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus. Br J Dermatol 1996; 135:355–362.

- Franceschini F, Calzavara-Pinton P, Quinzanini M, et al. Chilblain lupus erythematosus is associated with antibodies to SSA/Ro. Lupus 1999; 8:215–219.

- Bouaziz JD, Barete S, Le Pelletier F, Amoura Z, Piette JC, Francès C. Cutaneous lesions of the digits in systemic lupus erythematosus: 50 cases. Lupus 2007; 16:163–167.

An erythematous plaque on the arm

A healthy 68-year-old farmer presents with an asymptomatic skin lesion on his right arm that appeared spontaneously without trauma or bite 5 months ago and has grown progressively since then.

Q: Which is the most likely diagnosis?

- Squamous cell carcinoma

- Cutaneous lymphoma

- Cutaneous mycobacteriosis

- Sarcoidosis

- Lichen planus

As for the other possibilities:

Cutaneous lymphoma, characterized by atypical proliferation of T or B lymphocytes in the skin, usually presents as a slow-growing indurated nodule or plaque.

Cutaneous mycobacteriosis is caused by infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis, M leprae, or M marinum. Caseous granulomas are often found on histopathologic study, but special culture and polymerase chain reaction tests are necessary for the diagnosis. Clinically, the lesion is an indurated nodule or plaque that grows slowly, with decreased sensitivity in the case of leprosy, and with a sporotrichoid pattern in the case of M marinum infection.

Our patient underwent a tuberculin skin test, which was negative, as were polymerase chain reaction testing and culture of the biopsy material for mycobacteria.

Sarcoidosis is a systemic disease of unknown cause characterized by noncaseous granulomas in the lungs, mediastinum, lymph nodes, or other sites.1 Cutaneous involvement includes nonspecific clinical forms (eg, nodosum erythema) and other more specific forms (eg, maculopapular, subcutaneous, cicatricial, or lupus pernio variants). This patient has no granulomas on skin biopsy.

Lichen planus is a chronic inflammatory disease of unknown cause that affects the skin, genitalia, mucous membranes, or appendages. It appears as pruritic purple polygonal papules with Wickham striae, usually affecting the wrists and ankles.

A COMMON FORM OF SKIN CANCER

Squamous cell carcinoma and basal cell carcinoma account for 95% of cases of nonmelanomatous skin cancer, and the incidence of squamous cell carcinoma has been increasing.

Long-term exposure to ultraviolet radiation (ie, sunlight), often related to occupation, is the most common cause of squamous cell carcinoma. Other risk factors include thermal injury or burns, ionizing radiation, human papilloma virus infection, immunosuppressive therapy (eg, after organ transplantation2), exposure to chemical carcinogens, and diseases such as xeroderma pigmentosum or oculocutaneous albinism. Unlike basal cell carcinoma, which usually arises de novo, squamous cell carcinoma often arises from precursor lesions, such as actinic keratosis and Bowen disease.

Squamous cell carcinoma commonly manifests as shallow ulcers, often with a keratinous crust and an elevated, indurated border, but also as plaques or nodules, as in this patient. Incipient lesions present as erythematous, firm, keratotic papules, but the lesions on sun-exposed areas such as the head or neck can be pigmented.

The surrounding skin usually shows changes of actinic damage, usually with ulceration, scaling, crusting, or verrucous appearance. When the lesion presents as an erythematous plaque, as in this patient, mycobacterial infection and cutaneous lymphoma should be ruled out. Histologic studies and culture for mycobacteria are necessary for an acute diagnosis. Other conditions in the differential diagnosis are keratoacanthoma, cutaneous metastasis, and sarcoidosis.

The only way to confirm the diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma is to obtain a specimen by biopsy or surgical excision. Histologic features include atypical keratinocytes extending from the epidermis to the dermis, with dyskeratosis, intercellular bridges, variable central keratinization, and “horn pearls,” depending on how well or how poorly differentiated the tumor.3 Most squamous cell carcinomas arise in solar keratoses, usually at the periphery of the tumor.

Most squamous cell carcinomas are only locally aggressive. Tumors greater than 5 mm in thickness have a 20% risk of metastasis.

TREATMENT OPTIONS

Surgical excision is the most common treatment. Other options are cryotherapy, topical chemotherapy, curettage and electrodesiccation, radiotherapy, and Mohs micrographic surgery. Photodynamic therapy or imiquimod (Aldara) are used only for noninvasive forms.

The possibility of metastasis should be investigated in cases of extensive squamous cell carcinoma, when mucous membranes are affected, and when squamous cell lesions are poorly differentiated.

Our patient’s tumor was removed, with adequate safety margins in surface and depth, and with dermo-epidermal graft closure. The lesion has not recurred at 9 months of follow-up.

- Hunninghake GW, Costabel U, Ando M, et al. ATS/ERS/WASOG statement on sarcoidosis. American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society/World Association of Sarcoidosis and other Granulomatous Disorders. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis 1999; 16:149–173.

- Rubel JR, Milford EL, Abdi R. Cutaneous neoplasms in renal transplant recipients. Eur J Dermatol 2002; 12:532–535.

- Cassarino DS, Derienzo DP, Barr RJ. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: a comprehensive clinicopathologic classification—part two. J Cutan Pathol 2006; 33:261–279.

A healthy 68-year-old farmer presents with an asymptomatic skin lesion on his right arm that appeared spontaneously without trauma or bite 5 months ago and has grown progressively since then.

Q: Which is the most likely diagnosis?

- Squamous cell carcinoma

- Cutaneous lymphoma

- Cutaneous mycobacteriosis

- Sarcoidosis

- Lichen planus

As for the other possibilities:

Cutaneous lymphoma, characterized by atypical proliferation of T or B lymphocytes in the skin, usually presents as a slow-growing indurated nodule or plaque.

Cutaneous mycobacteriosis is caused by infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis, M leprae, or M marinum. Caseous granulomas are often found on histopathologic study, but special culture and polymerase chain reaction tests are necessary for the diagnosis. Clinically, the lesion is an indurated nodule or plaque that grows slowly, with decreased sensitivity in the case of leprosy, and with a sporotrichoid pattern in the case of M marinum infection.

Our patient underwent a tuberculin skin test, which was negative, as were polymerase chain reaction testing and culture of the biopsy material for mycobacteria.

Sarcoidosis is a systemic disease of unknown cause characterized by noncaseous granulomas in the lungs, mediastinum, lymph nodes, or other sites.1 Cutaneous involvement includes nonspecific clinical forms (eg, nodosum erythema) and other more specific forms (eg, maculopapular, subcutaneous, cicatricial, or lupus pernio variants). This patient has no granulomas on skin biopsy.

Lichen planus is a chronic inflammatory disease of unknown cause that affects the skin, genitalia, mucous membranes, or appendages. It appears as pruritic purple polygonal papules with Wickham striae, usually affecting the wrists and ankles.

A COMMON FORM OF SKIN CANCER

Squamous cell carcinoma and basal cell carcinoma account for 95% of cases of nonmelanomatous skin cancer, and the incidence of squamous cell carcinoma has been increasing.

Long-term exposure to ultraviolet radiation (ie, sunlight), often related to occupation, is the most common cause of squamous cell carcinoma. Other risk factors include thermal injury or burns, ionizing radiation, human papilloma virus infection, immunosuppressive therapy (eg, after organ transplantation2), exposure to chemical carcinogens, and diseases such as xeroderma pigmentosum or oculocutaneous albinism. Unlike basal cell carcinoma, which usually arises de novo, squamous cell carcinoma often arises from precursor lesions, such as actinic keratosis and Bowen disease.

Squamous cell carcinoma commonly manifests as shallow ulcers, often with a keratinous crust and an elevated, indurated border, but also as plaques or nodules, as in this patient. Incipient lesions present as erythematous, firm, keratotic papules, but the lesions on sun-exposed areas such as the head or neck can be pigmented.

The surrounding skin usually shows changes of actinic damage, usually with ulceration, scaling, crusting, or verrucous appearance. When the lesion presents as an erythematous plaque, as in this patient, mycobacterial infection and cutaneous lymphoma should be ruled out. Histologic studies and culture for mycobacteria are necessary for an acute diagnosis. Other conditions in the differential diagnosis are keratoacanthoma, cutaneous metastasis, and sarcoidosis.

The only way to confirm the diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma is to obtain a specimen by biopsy or surgical excision. Histologic features include atypical keratinocytes extending from the epidermis to the dermis, with dyskeratosis, intercellular bridges, variable central keratinization, and “horn pearls,” depending on how well or how poorly differentiated the tumor.3 Most squamous cell carcinomas arise in solar keratoses, usually at the periphery of the tumor.

Most squamous cell carcinomas are only locally aggressive. Tumors greater than 5 mm in thickness have a 20% risk of metastasis.

TREATMENT OPTIONS

Surgical excision is the most common treatment. Other options are cryotherapy, topical chemotherapy, curettage and electrodesiccation, radiotherapy, and Mohs micrographic surgery. Photodynamic therapy or imiquimod (Aldara) are used only for noninvasive forms.

The possibility of metastasis should be investigated in cases of extensive squamous cell carcinoma, when mucous membranes are affected, and when squamous cell lesions are poorly differentiated.

Our patient’s tumor was removed, with adequate safety margins in surface and depth, and with dermo-epidermal graft closure. The lesion has not recurred at 9 months of follow-up.

A healthy 68-year-old farmer presents with an asymptomatic skin lesion on his right arm that appeared spontaneously without trauma or bite 5 months ago and has grown progressively since then.

Q: Which is the most likely diagnosis?

- Squamous cell carcinoma

- Cutaneous lymphoma

- Cutaneous mycobacteriosis

- Sarcoidosis

- Lichen planus

As for the other possibilities:

Cutaneous lymphoma, characterized by atypical proliferation of T or B lymphocytes in the skin, usually presents as a slow-growing indurated nodule or plaque.

Cutaneous mycobacteriosis is caused by infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis, M leprae, or M marinum. Caseous granulomas are often found on histopathologic study, but special culture and polymerase chain reaction tests are necessary for the diagnosis. Clinically, the lesion is an indurated nodule or plaque that grows slowly, with decreased sensitivity in the case of leprosy, and with a sporotrichoid pattern in the case of M marinum infection.

Our patient underwent a tuberculin skin test, which was negative, as were polymerase chain reaction testing and culture of the biopsy material for mycobacteria.

Sarcoidosis is a systemic disease of unknown cause characterized by noncaseous granulomas in the lungs, mediastinum, lymph nodes, or other sites.1 Cutaneous involvement includes nonspecific clinical forms (eg, nodosum erythema) and other more specific forms (eg, maculopapular, subcutaneous, cicatricial, or lupus pernio variants). This patient has no granulomas on skin biopsy.

Lichen planus is a chronic inflammatory disease of unknown cause that affects the skin, genitalia, mucous membranes, or appendages. It appears as pruritic purple polygonal papules with Wickham striae, usually affecting the wrists and ankles.

A COMMON FORM OF SKIN CANCER

Squamous cell carcinoma and basal cell carcinoma account for 95% of cases of nonmelanomatous skin cancer, and the incidence of squamous cell carcinoma has been increasing.

Long-term exposure to ultraviolet radiation (ie, sunlight), often related to occupation, is the most common cause of squamous cell carcinoma. Other risk factors include thermal injury or burns, ionizing radiation, human papilloma virus infection, immunosuppressive therapy (eg, after organ transplantation2), exposure to chemical carcinogens, and diseases such as xeroderma pigmentosum or oculocutaneous albinism. Unlike basal cell carcinoma, which usually arises de novo, squamous cell carcinoma often arises from precursor lesions, such as actinic keratosis and Bowen disease.

Squamous cell carcinoma commonly manifests as shallow ulcers, often with a keratinous crust and an elevated, indurated border, but also as plaques or nodules, as in this patient. Incipient lesions present as erythematous, firm, keratotic papules, but the lesions on sun-exposed areas such as the head or neck can be pigmented.

The surrounding skin usually shows changes of actinic damage, usually with ulceration, scaling, crusting, or verrucous appearance. When the lesion presents as an erythematous plaque, as in this patient, mycobacterial infection and cutaneous lymphoma should be ruled out. Histologic studies and culture for mycobacteria are necessary for an acute diagnosis. Other conditions in the differential diagnosis are keratoacanthoma, cutaneous metastasis, and sarcoidosis.

The only way to confirm the diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma is to obtain a specimen by biopsy or surgical excision. Histologic features include atypical keratinocytes extending from the epidermis to the dermis, with dyskeratosis, intercellular bridges, variable central keratinization, and “horn pearls,” depending on how well or how poorly differentiated the tumor.3 Most squamous cell carcinomas arise in solar keratoses, usually at the periphery of the tumor.

Most squamous cell carcinomas are only locally aggressive. Tumors greater than 5 mm in thickness have a 20% risk of metastasis.

TREATMENT OPTIONS

Surgical excision is the most common treatment. Other options are cryotherapy, topical chemotherapy, curettage and electrodesiccation, radiotherapy, and Mohs micrographic surgery. Photodynamic therapy or imiquimod (Aldara) are used only for noninvasive forms.

The possibility of metastasis should be investigated in cases of extensive squamous cell carcinoma, when mucous membranes are affected, and when squamous cell lesions are poorly differentiated.

Our patient’s tumor was removed, with adequate safety margins in surface and depth, and with dermo-epidermal graft closure. The lesion has not recurred at 9 months of follow-up.

- Hunninghake GW, Costabel U, Ando M, et al. ATS/ERS/WASOG statement on sarcoidosis. American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society/World Association of Sarcoidosis and other Granulomatous Disorders. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis 1999; 16:149–173.

- Rubel JR, Milford EL, Abdi R. Cutaneous neoplasms in renal transplant recipients. Eur J Dermatol 2002; 12:532–535.

- Cassarino DS, Derienzo DP, Barr RJ. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: a comprehensive clinicopathologic classification—part two. J Cutan Pathol 2006; 33:261–279.

- Hunninghake GW, Costabel U, Ando M, et al. ATS/ERS/WASOG statement on sarcoidosis. American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society/World Association of Sarcoidosis and other Granulomatous Disorders. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis 1999; 16:149–173.

- Rubel JR, Milford EL, Abdi R. Cutaneous neoplasms in renal transplant recipients. Eur J Dermatol 2002; 12:532–535.

- Cassarino DS, Derienzo DP, Barr RJ. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: a comprehensive clinicopathologic classification—part two. J Cutan Pathol 2006; 33:261–279.

Giant nodules on the hands

Q: Which is the most likely diagnosis?

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Nodular osteoarthritis

- Tophaceous gout

- Pseudogout

- Xanthoma tuberosum

A: Tophaceous gout is the diagnosis. This patient’s serum urate level was 9 mg/dL (normal range 4.0–8.0) despite allopurinol therapy, with normal levels of lipids, urea, and creatinine. Polarized light microscopy of aspirated synovial fluid showed monosodium urate crystals, thus confirming the diagnosis.

Rheumatoid arthritis is typically polyarticular and symmetrical and spares the distal interphalangeal joints. Subcutaneous rheumatoid nodules may mimic gouty tophi.

Pseudogout shares some of the features of gout. It results from deposits of calcium pyrophosphate crystals in and around the joints. The diagnosis is made by identifying the crystals on microscopy when calcinosis is seen on x-ray. Tophaceous nodules almost never occur.

Xanthoma tuberosum is associated with hypercholesterolemia, particularly with elevated levels of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol. Lesions occur on pressure areas such as the knees or elbows and vary in size and shape from small papules to firm, lobulated tumors. They are yellow or orange, often with an erythematous halo. They are not associated with chronic proliferative arthritis.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION OF GOUT

Gout is a common metabolic disease characterized by an intermittent course of acute inflammatory arthritis initially affecting one or a few joints. Almost all patients have hyperuricemia, but serum urate levels can be normal or low during an acute attack. On the other hand, many hyperuricemic patients never have a clinical event.

If the hyperuricemia is untreated, some patients develop chronic polyarthritis and nephrolithiasis.1 Inadequate treatment of hyperuricemia may result in chronic tophaceous gout. Although tophaceous gout usually is a sign of long-standing hyperuricemia, tophi can in rare cases be a first symptom of the disorder.2

Even though our patient had been on allopurinol therapy, the dose was not high enough to achieve a serum urate level significantly below the saturation point of urate (about 6.7 mg/dL).

- Logan JA, Morrison E, McGill PE. Serum uric acid in acute gout. Ann Rheum Dis 1997; 56:696–697.

- Thissen CA, Frank J, Lucker GP. Tophi as first clinical sign of gout. Int J Dermatol 2008; 47( suppl 1):49–51.

Q: Which is the most likely diagnosis?

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Nodular osteoarthritis

- Tophaceous gout

- Pseudogout

- Xanthoma tuberosum

A: Tophaceous gout is the diagnosis. This patient’s serum urate level was 9 mg/dL (normal range 4.0–8.0) despite allopurinol therapy, with normal levels of lipids, urea, and creatinine. Polarized light microscopy of aspirated synovial fluid showed monosodium urate crystals, thus confirming the diagnosis.

Rheumatoid arthritis is typically polyarticular and symmetrical and spares the distal interphalangeal joints. Subcutaneous rheumatoid nodules may mimic gouty tophi.

Pseudogout shares some of the features of gout. It results from deposits of calcium pyrophosphate crystals in and around the joints. The diagnosis is made by identifying the crystals on microscopy when calcinosis is seen on x-ray. Tophaceous nodules almost never occur.

Xanthoma tuberosum is associated with hypercholesterolemia, particularly with elevated levels of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol. Lesions occur on pressure areas such as the knees or elbows and vary in size and shape from small papules to firm, lobulated tumors. They are yellow or orange, often with an erythematous halo. They are not associated with chronic proliferative arthritis.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION OF GOUT

Gout is a common metabolic disease characterized by an intermittent course of acute inflammatory arthritis initially affecting one or a few joints. Almost all patients have hyperuricemia, but serum urate levels can be normal or low during an acute attack. On the other hand, many hyperuricemic patients never have a clinical event.

If the hyperuricemia is untreated, some patients develop chronic polyarthritis and nephrolithiasis.1 Inadequate treatment of hyperuricemia may result in chronic tophaceous gout. Although tophaceous gout usually is a sign of long-standing hyperuricemia, tophi can in rare cases be a first symptom of the disorder.2

Even though our patient had been on allopurinol therapy, the dose was not high enough to achieve a serum urate level significantly below the saturation point of urate (about 6.7 mg/dL).

Q: Which is the most likely diagnosis?

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Nodular osteoarthritis

- Tophaceous gout

- Pseudogout

- Xanthoma tuberosum

A: Tophaceous gout is the diagnosis. This patient’s serum urate level was 9 mg/dL (normal range 4.0–8.0) despite allopurinol therapy, with normal levels of lipids, urea, and creatinine. Polarized light microscopy of aspirated synovial fluid showed monosodium urate crystals, thus confirming the diagnosis.

Rheumatoid arthritis is typically polyarticular and symmetrical and spares the distal interphalangeal joints. Subcutaneous rheumatoid nodules may mimic gouty tophi.

Pseudogout shares some of the features of gout. It results from deposits of calcium pyrophosphate crystals in and around the joints. The diagnosis is made by identifying the crystals on microscopy when calcinosis is seen on x-ray. Tophaceous nodules almost never occur.

Xanthoma tuberosum is associated with hypercholesterolemia, particularly with elevated levels of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol. Lesions occur on pressure areas such as the knees or elbows and vary in size and shape from small papules to firm, lobulated tumors. They are yellow or orange, often with an erythematous halo. They are not associated with chronic proliferative arthritis.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION OF GOUT

Gout is a common metabolic disease characterized by an intermittent course of acute inflammatory arthritis initially affecting one or a few joints. Almost all patients have hyperuricemia, but serum urate levels can be normal or low during an acute attack. On the other hand, many hyperuricemic patients never have a clinical event.

If the hyperuricemia is untreated, some patients develop chronic polyarthritis and nephrolithiasis.1 Inadequate treatment of hyperuricemia may result in chronic tophaceous gout. Although tophaceous gout usually is a sign of long-standing hyperuricemia, tophi can in rare cases be a first symptom of the disorder.2

Even though our patient had been on allopurinol therapy, the dose was not high enough to achieve a serum urate level significantly below the saturation point of urate (about 6.7 mg/dL).

- Logan JA, Morrison E, McGill PE. Serum uric acid in acute gout. Ann Rheum Dis 1997; 56:696–697.

- Thissen CA, Frank J, Lucker GP. Tophi as first clinical sign of gout. Int J Dermatol 2008; 47( suppl 1):49–51.

- Logan JA, Morrison E, McGill PE. Serum uric acid in acute gout. Ann Rheum Dis 1997; 56:696–697.

- Thissen CA, Frank J, Lucker GP. Tophi as first clinical sign of gout. Int J Dermatol 2008; 47( suppl 1):49–51.

Palpable purpura

Q: Which is the most likely diagnosis?

- Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura

- Vitamin C deficiency (scurvy)

- Kaposi sarcoma not related to human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection

- Henoch-Schönlein purpura

- Polyarteritis nodosa

A: The correct answer is Henoch-Schönlein purpura.

Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura is an autoimmune disease caused by specific antibodies against platelet-membrane glycoproteins. It is characterized by thrombocytopenia not explainable by contact with toxic substances or by other causes. Along with nonpalpable purpura, other common signs are epistaxis, gingival bleeding, menorrhagia, and retinal hemorrhage.

Scurvy is an uncommon deficiency of ascorbic acid (vitamin C). The elderly and alcoholics are at higher risk, as they do not take in enough vitamin C in the diet. Patients usually show perifollicular hemorrhages of the skin and mucous membranes, typically petechial hemorrhage or ecchymosis of the gums around the upper incisors. Other cutaneous signs are follicular hyperkeratosis on the forearms, small corkscrew hairs, and sicca syndrome, which is more common in adults.

Non-HIV Kaposi sarcoma usually affects elderly patients, with pink, red, or brown papules or nodules on the legs and, less commonly, on the head and neck. Histopathologic examination shows newly formed irregular blood vessels with an inflammatory infiltrate of plasma cells and lymphocytes; immunohistochemical human herpes virus staining is usually positive.

Polyarteritis nodosa is a systemic vasculitis that affects medium or small arteries with necrotizing inflammation; renal glomeruli and arterioles, capillaries, and venules are unaffected. Skin manifestations include palpable purpura, livedo reticularis, ulcers, and distal gangrene. The condition also usually affects the kidneys, the heart, and the musculoskeletal and nervous systems.

A SYSTEMIC VASCULITIS

Henoch-Schönlein purpura is a systemic vasculitis affecting the skin, gastrointestinal tract, kidneys, and joints. Palpable purpura and joint pain are the most common and consistent presenting symptoms. The kidneys are affected in about one-third of children and in 60% of adults, and this is the major factor determining the long-term outcome.1

In our patient, laboratory testing that included a complete blood cell count, biochemical testing (including IgA levels), urinary sediment, and coagulation studies showed no abnormalities except elevations of the erythrocyte sedimentation rate and the concentration of C-reactive protein (an acute-phase reactant). These can be normal in some patients. Renal involvement was also not present.

DIAGNOSIS

The diagnosis relies on clinical manifestations. Because Henoch-Schönlein purpura is less common in adults, biopsy plays a more important role in establishing the diagnosis in this age group, and it does this by demonstrating leukocytoclastic vasculitis with a predominance of IgA deposition under immunofluorescence. Recent studies in children showed that an elevated IgA concentration along with reduced IgM levels was associated with a higher rate of severe complications.2 However, depending on the age of the biopsied lesion, IgA may not be detected.

TREATMENT DIRECTED AT SYMPTOMS

Our patient received oral corticosteroids 0.5 mg/kg per day for 20 days, and the lesions resolved by 4 weeks.

Management of Henoch-Schönlein purpura is mainly directed at the symptoms, with oral hydration and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. For severe cases, a short course of corticosteroids (0.5–1 mg/kg) may be used.

Although no controlled clinical trial has proven that Henoch-Schönlein purpura responds to corticosteroids, colchicine, or other drugs, corticosteroids are used most often, especially in patients with renal disease. Patients with severe renal insufficiency, abdominal pain, joint involvement, or bleeding should be hospitalized. Plasmapheresis3 has been used in severe cases.

HENOCH-SCHÖNLEIN PURPURA AND MALIGNANCY

During a follow-up evaluation 1 month later, our patient was diagnosed with adenocarcinoma of the breast. This highlights the value of a workup for cancer in adults with cutaneous vasculitis.

Cutaneous vasculitis can represent a paraneoplastic syndrome associated with a malignant tumor. The pathophysiology of this association is unclear, but one proposed mechanism is the exaggerated production of antibodies that react against tumor neoantigens, leading to the formation of immune complexes, or that occasionally recognize endothelial cells because of similarities with tumor antigens. Another theory is that abnormally high levels of inflammatory cytokines are produced by neoplastic cells or in response to decreased immune complex clearance.

Yet another theory is that hyperviscosity of the blood, seen in some cancers, increases the contact time for deposition of immune complexes and causes endothelial damage. Drugs used to treat cancer have also been reported to produce Henoch-Schönlein purpura.4

Although hematologic malignancy is three to five times more common than solid tumors in patients with small-vessel vasculitis, the disease has been associated with solid tumors of the liver, skin, colon, and breast in adults over age 40.5 An evaluation for neoplasm is therefore reasonable in adults with Henoch-Schönlein purpura, as is an evaluation for tumor recurrence or metastasis if the patient has been previously treated for a malignant tumor.

- Rieu P, Noël LH. Henoch-Schönlein nephritis in children and adults. Morphological features and clinicopathological correlations. Ann Med Interne (Paris) 1999; 150:151–159.

- Fretzayas A, Sionti I, Moustaki M, Nicolaidou P. Clinical impact of altered immunoglobulin levels in Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Pediatr Int 2009; 51:381–384.

- Donghi D, Schanz U, Sahrbacher U, et al. Life-threatening or organimpairing Henoch-Schönlein purpura: plasmapheresis may save lives and limit organ damage. Dermatology 2009; 219:167–170.

- Mitsui H, Shibagaki N, Kawamura T, Matsue H, Shimada S. A clinical study of Henoch-Schönlein purpura associated with malignancy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2009; 23:394–401.

- Maestri A, Malacarne P, Santini A. Henoch-Schönlein syndrome associated with breast cancer. A case report. Angiology 1995; 46:625–627.

Q: Which is the most likely diagnosis?

- Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura

- Vitamin C deficiency (scurvy)

- Kaposi sarcoma not related to human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection

- Henoch-Schönlein purpura

- Polyarteritis nodosa

A: The correct answer is Henoch-Schönlein purpura.

Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura is an autoimmune disease caused by specific antibodies against platelet-membrane glycoproteins. It is characterized by thrombocytopenia not explainable by contact with toxic substances or by other causes. Along with nonpalpable purpura, other common signs are epistaxis, gingival bleeding, menorrhagia, and retinal hemorrhage.

Scurvy is an uncommon deficiency of ascorbic acid (vitamin C). The elderly and alcoholics are at higher risk, as they do not take in enough vitamin C in the diet. Patients usually show perifollicular hemorrhages of the skin and mucous membranes, typically petechial hemorrhage or ecchymosis of the gums around the upper incisors. Other cutaneous signs are follicular hyperkeratosis on the forearms, small corkscrew hairs, and sicca syndrome, which is more common in adults.

Non-HIV Kaposi sarcoma usually affects elderly patients, with pink, red, or brown papules or nodules on the legs and, less commonly, on the head and neck. Histopathologic examination shows newly formed irregular blood vessels with an inflammatory infiltrate of plasma cells and lymphocytes; immunohistochemical human herpes virus staining is usually positive.

Polyarteritis nodosa is a systemic vasculitis that affects medium or small arteries with necrotizing inflammation; renal glomeruli and arterioles, capillaries, and venules are unaffected. Skin manifestations include palpable purpura, livedo reticularis, ulcers, and distal gangrene. The condition also usually affects the kidneys, the heart, and the musculoskeletal and nervous systems.

A SYSTEMIC VASCULITIS

Henoch-Schönlein purpura is a systemic vasculitis affecting the skin, gastrointestinal tract, kidneys, and joints. Palpable purpura and joint pain are the most common and consistent presenting symptoms. The kidneys are affected in about one-third of children and in 60% of adults, and this is the major factor determining the long-term outcome.1

In our patient, laboratory testing that included a complete blood cell count, biochemical testing (including IgA levels), urinary sediment, and coagulation studies showed no abnormalities except elevations of the erythrocyte sedimentation rate and the concentration of C-reactive protein (an acute-phase reactant). These can be normal in some patients. Renal involvement was also not present.

DIAGNOSIS

The diagnosis relies on clinical manifestations. Because Henoch-Schönlein purpura is less common in adults, biopsy plays a more important role in establishing the diagnosis in this age group, and it does this by demonstrating leukocytoclastic vasculitis with a predominance of IgA deposition under immunofluorescence. Recent studies in children showed that an elevated IgA concentration along with reduced IgM levels was associated with a higher rate of severe complications.2 However, depending on the age of the biopsied lesion, IgA may not be detected.

TREATMENT DIRECTED AT SYMPTOMS

Our patient received oral corticosteroids 0.5 mg/kg per day for 20 days, and the lesions resolved by 4 weeks.

Management of Henoch-Schönlein purpura is mainly directed at the symptoms, with oral hydration and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. For severe cases, a short course of corticosteroids (0.5–1 mg/kg) may be used.

Although no controlled clinical trial has proven that Henoch-Schönlein purpura responds to corticosteroids, colchicine, or other drugs, corticosteroids are used most often, especially in patients with renal disease. Patients with severe renal insufficiency, abdominal pain, joint involvement, or bleeding should be hospitalized. Plasmapheresis3 has been used in severe cases.

HENOCH-SCHÖNLEIN PURPURA AND MALIGNANCY

During a follow-up evaluation 1 month later, our patient was diagnosed with adenocarcinoma of the breast. This highlights the value of a workup for cancer in adults with cutaneous vasculitis.

Cutaneous vasculitis can represent a paraneoplastic syndrome associated with a malignant tumor. The pathophysiology of this association is unclear, but one proposed mechanism is the exaggerated production of antibodies that react against tumor neoantigens, leading to the formation of immune complexes, or that occasionally recognize endothelial cells because of similarities with tumor antigens. Another theory is that abnormally high levels of inflammatory cytokines are produced by neoplastic cells or in response to decreased immune complex clearance.

Yet another theory is that hyperviscosity of the blood, seen in some cancers, increases the contact time for deposition of immune complexes and causes endothelial damage. Drugs used to treat cancer have also been reported to produce Henoch-Schönlein purpura.4

Although hematologic malignancy is three to five times more common than solid tumors in patients with small-vessel vasculitis, the disease has been associated with solid tumors of the liver, skin, colon, and breast in adults over age 40.5 An evaluation for neoplasm is therefore reasonable in adults with Henoch-Schönlein purpura, as is an evaluation for tumor recurrence or metastasis if the patient has been previously treated for a malignant tumor.

Q: Which is the most likely diagnosis?

- Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura

- Vitamin C deficiency (scurvy)

- Kaposi sarcoma not related to human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection

- Henoch-Schönlein purpura

- Polyarteritis nodosa

A: The correct answer is Henoch-Schönlein purpura.

Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura is an autoimmune disease caused by specific antibodies against platelet-membrane glycoproteins. It is characterized by thrombocytopenia not explainable by contact with toxic substances or by other causes. Along with nonpalpable purpura, other common signs are epistaxis, gingival bleeding, menorrhagia, and retinal hemorrhage.

Scurvy is an uncommon deficiency of ascorbic acid (vitamin C). The elderly and alcoholics are at higher risk, as they do not take in enough vitamin C in the diet. Patients usually show perifollicular hemorrhages of the skin and mucous membranes, typically petechial hemorrhage or ecchymosis of the gums around the upper incisors. Other cutaneous signs are follicular hyperkeratosis on the forearms, small corkscrew hairs, and sicca syndrome, which is more common in adults.

Non-HIV Kaposi sarcoma usually affects elderly patients, with pink, red, or brown papules or nodules on the legs and, less commonly, on the head and neck. Histopathologic examination shows newly formed irregular blood vessels with an inflammatory infiltrate of plasma cells and lymphocytes; immunohistochemical human herpes virus staining is usually positive.

Polyarteritis nodosa is a systemic vasculitis that affects medium or small arteries with necrotizing inflammation; renal glomeruli and arterioles, capillaries, and venules are unaffected. Skin manifestations include palpable purpura, livedo reticularis, ulcers, and distal gangrene. The condition also usually affects the kidneys, the heart, and the musculoskeletal and nervous systems.

A SYSTEMIC VASCULITIS