User login

Methodological Progress Note: Interrupted Time Series

Hospital medicine research often asks the question whether an intervention, such as a policy or guideline, has improved quality of care and/or whether there were any unintended consequences. Alternatively, investigators may be interested in understanding the impact of an event, such as a natural disaster or a pandemic, on hospital care. The study design that provides the best estimate of the causal effect of the intervention is the randomized controlled trial (RCT). The goal of randomization, which can be implemented at the patient or cluster level (eg, hospitals), is attaining a balance of the known and unknown confounders between study groups.

However, an RCT may not be feasible for several reasons: complexity, insufficient setup time or funding, ethical barriers to randomization, unwillingness of funders or payers to withhold the intervention from patients (ie, the control group), or anticipated contamination of the intervention into the control group (eg, provider practice change interventions). In addition, it may be impossible to conduct an RCT because the investigator does not have control over the design of an intervention or because they are studying an event, such as a pandemic.

In the June 2020 issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, Coon et al1 use a type of quasi-experimental design (QED)—specifically, the interrupted time series (ITS)—to examine the impact of the adoption of ward-based high-flow nasal cannula protocols on intensive care unit (ICU) admission for bronchiolitis at children’s hospitals. In this methodologic progress note, we discuss QEDs for evaluating the impact of healthcare interventions or events and focus on ITS, one of the strongest QEDs.

WHAT IS A QUASI-EXPERIMENTAL DESIGN?

Quasi-experimental design refers to a broad range of nonrandomized or partially randomized pre- vs postintervention studies.2 In order to test a causal hypothesis without randomization, QEDs define a comparison group or a time period in which an intervention has not been implemented, as well as at least one group or time period in which an intervention has been implemented. In a QED, the control may lack similarity with the intervention group or time period because of differences in the patients, sites, or time period (sometimes referred to as having a “nonequivalent control group”). Several design and analytic approaches are available to enhance the extent to which the study is able to make conclusions about the causal impact of the intervention.2,3 Because randomization is not necessary, QEDs allow for inclusion of a broader population than that which is feasible by RCTs, which increases the applicability and generalizability of the results. Therefore, they are a powerful research design to test the effectiveness of interventions in real-world settings.

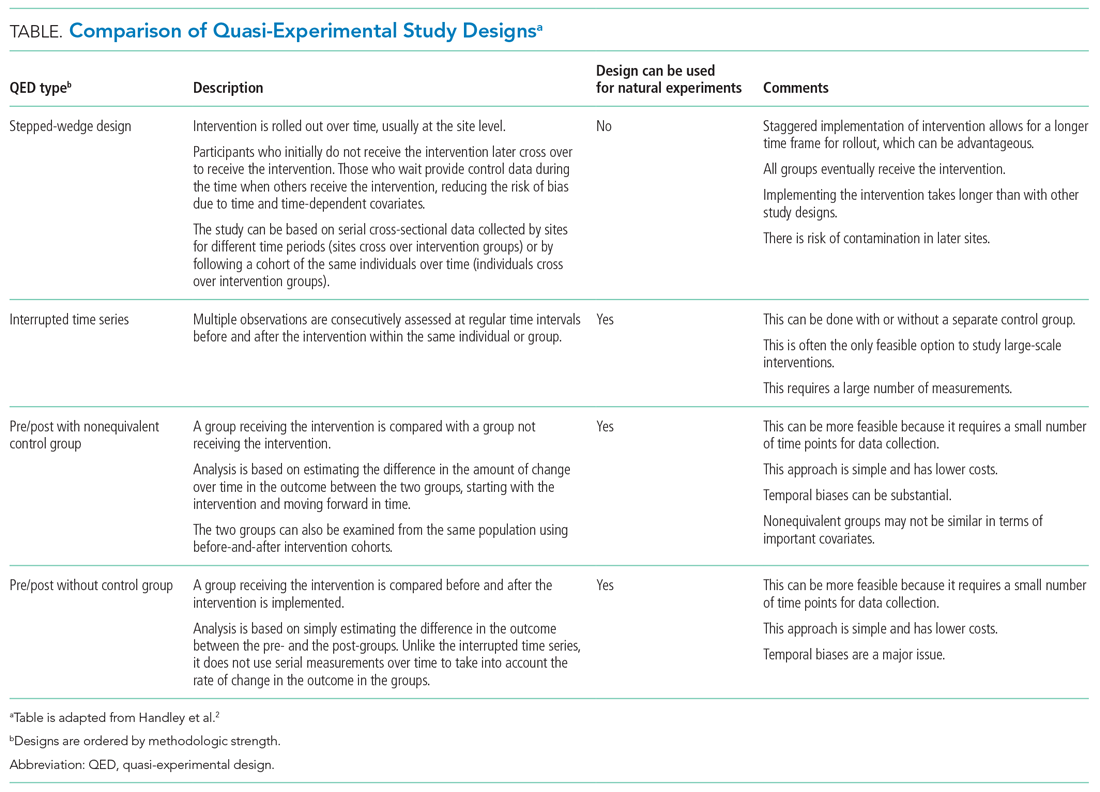

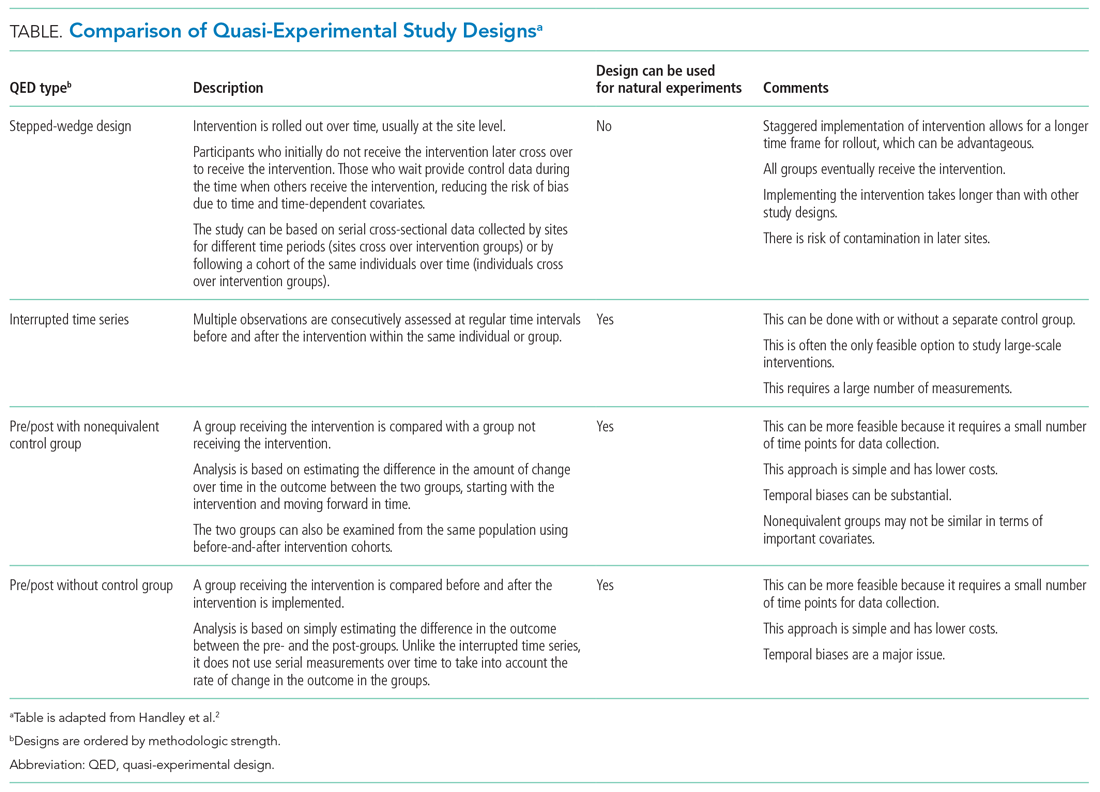

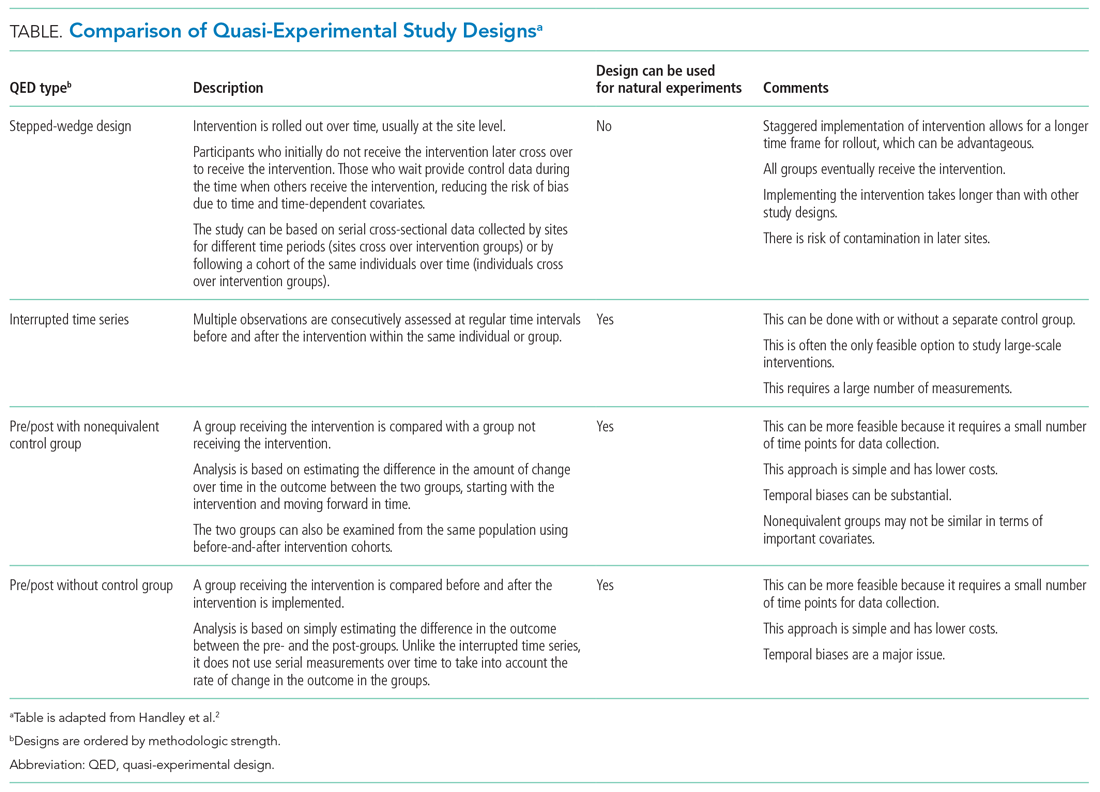

The choice of which QED depends on whether the investigators are conducting a prospective evaluation and have control over the study design (ie, the ordering of the intervention, selection of sites or individuals, and/or timing and frequency of the data collection) or whether the investigators do not have control over the intervention, which is also known as a “natural experiment.”4,5 Some studies may also incorporate two QEDs in tandem.6 The Table provides a brief summary of different QEDs, ordered by methodologic strength, and distinguishes those that can be used to study natural experiments. In the study by Coon et al,1 an ITS is used as opposed to a methodologically stronger QED, such as the stepped-wedge design, because the investigators did not have control over the rollout of heated high-flow nasal canula protocols across hospitals.

WHAT IS AN INTERRUPTED TIME SERIES?

Interrupted time series designs use repeated observations of an outcome over time. This method then divides, or “interrupts,” the series of data into two time periods: before the intervention or event and after. Using data from the preintervention period, an underlying trend in the outcome is estimated and assumed to continue forward into the postintervention period to estimate what would have occurred without the intervention. Any significant change in the outcome at the beginning of the postintervention period or change in the trend in the postintervention is then attributed to the intervention.

There are several important methodologic considerations when designing an ITS study, as detailed in other review papers.2,3,7,8 An ITS design can be retrospective or prospective. It can be of a single center or include multiple sites, as in Coon et al. It can be conducted with or without a control. The inclusion of a control, when appropriately chosen, improves the strength of the study design because it can account for seasonal trends and potential confounders that vary over time. The control can be a different group of hospitals or participants that are similar but did not receive the intervention, or it can be a different outcome in the same group of hospitals or participants that are not expected to be affected by the intervention. The ITS design may also be set up to estimate the individual effects of multicomponent interventions. If the different components are phased in sequentially over time, then it may be possible to interrupt the time series at these points and estimate the impact of each intervention component.

Other examples of ITS studies in hospital medicine include those that evaluated the impact of a readmission-reduction program,9 of state sepsis regulations on in-hospital mortality,10 of resident duty-hour reform on mortality among hospitalized patients,11 of a quality-improvement initiative on early discharge,12 and of national guidelines on pediatric pneumonia antibiotic selection.13 There are several types of ITS analysis, and in this article, we focus on segmented regression without a control group.7,8

WHAT IS A SEGMENTED REGRESSION ITS?

Segmented regression is the statistical model used to measure (a) the immediate change in the outcome (level) at the start of the intervention and (b) the change in the trend of the outcome (slope) in the postintervention period vs that in the preintervention period. Therefore, the intervention effect size is expressed in terms of the level change and the slope change. To function properly, the models require several repeated (eg, monthly) measurements of the outcome before and after the intervention. Some experts suggest a minimum of 4 to 12 observations, depending on a number of factors including the stability of the outcome and seasonal variations.7,8 If changes before and after more than one intervention are being examined, there should be the minimum number of observations separating them. Unlike typical regression models, time-series models can correct for autocorrelation if it is present in the data. Autocorrelation is the type of correlation that arises when data are collected over time, with those closest in time being more strongly correlated (there are also other types of autocorrelation, such as seasonal patterns). Using available statistical software, autocorrelation can be detected and, if present, it can be controlled for in the segmented regression models.

HOW ARE SEGMENTED REGRESSION RESULTS PRESENTED?

Coon et al present results of their ITS analysis in a panel of figures detailing each study outcome, ICU admission, ICU length of stay, total length of stay, and rates of mechanical ventilation. Each panel shows the rate of change in the outcome per season across hospitals, before and after adoption of heated high-flow nasal cannula protocols, and the level change at the time of adoption.

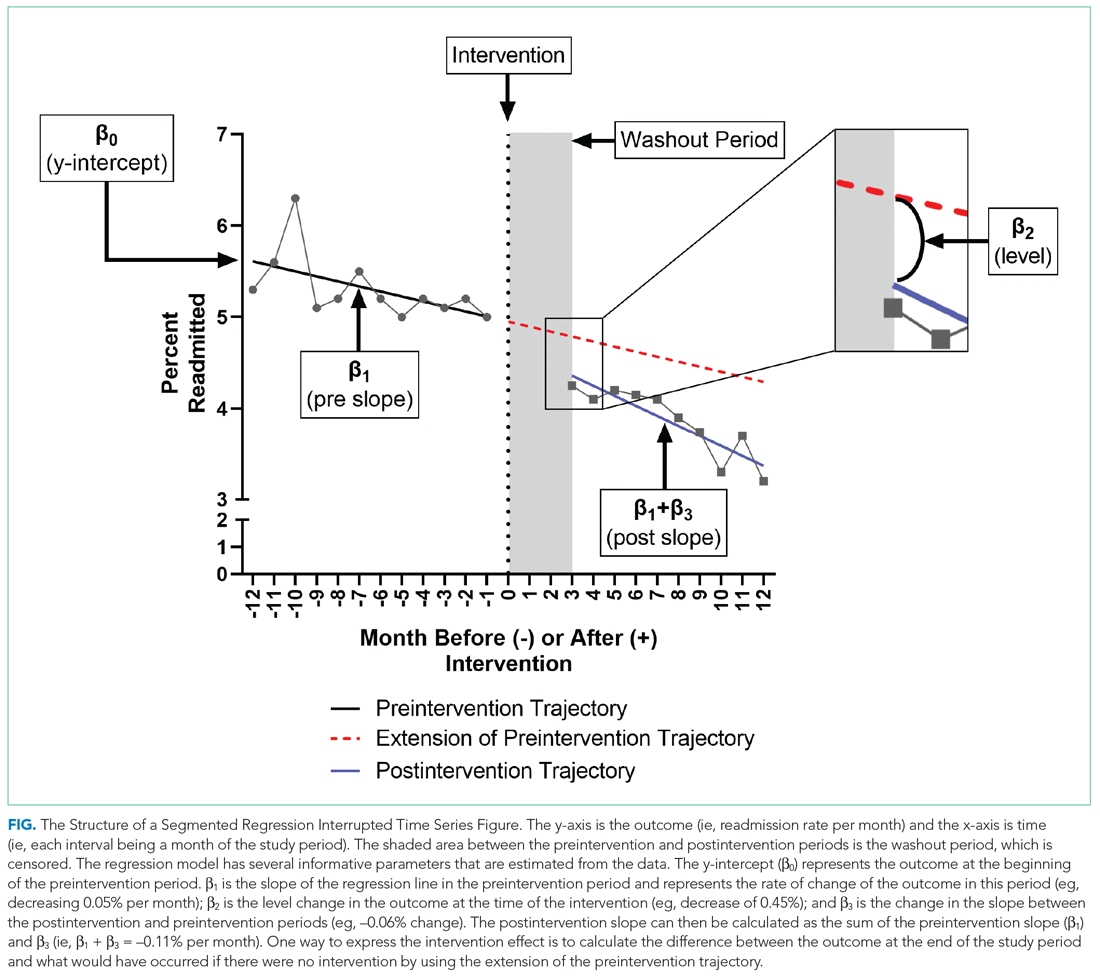

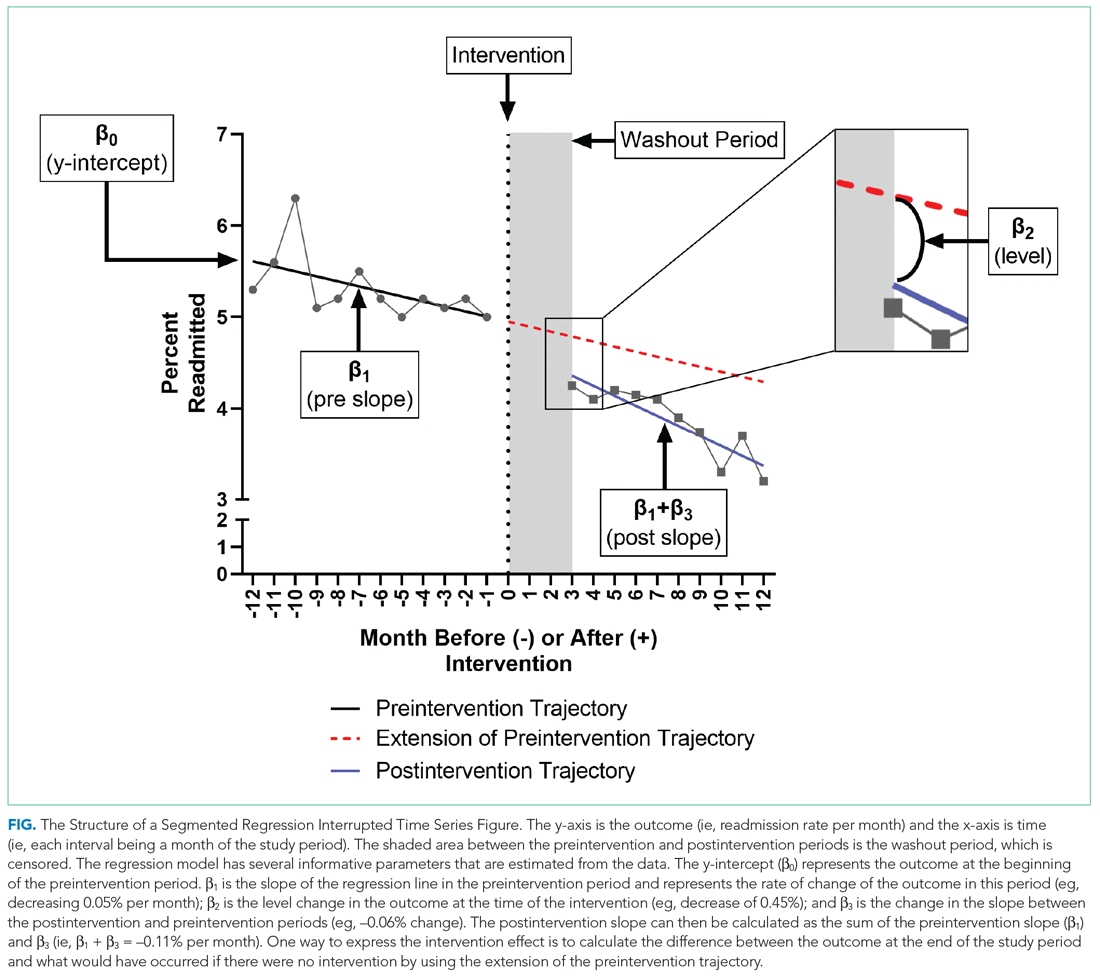

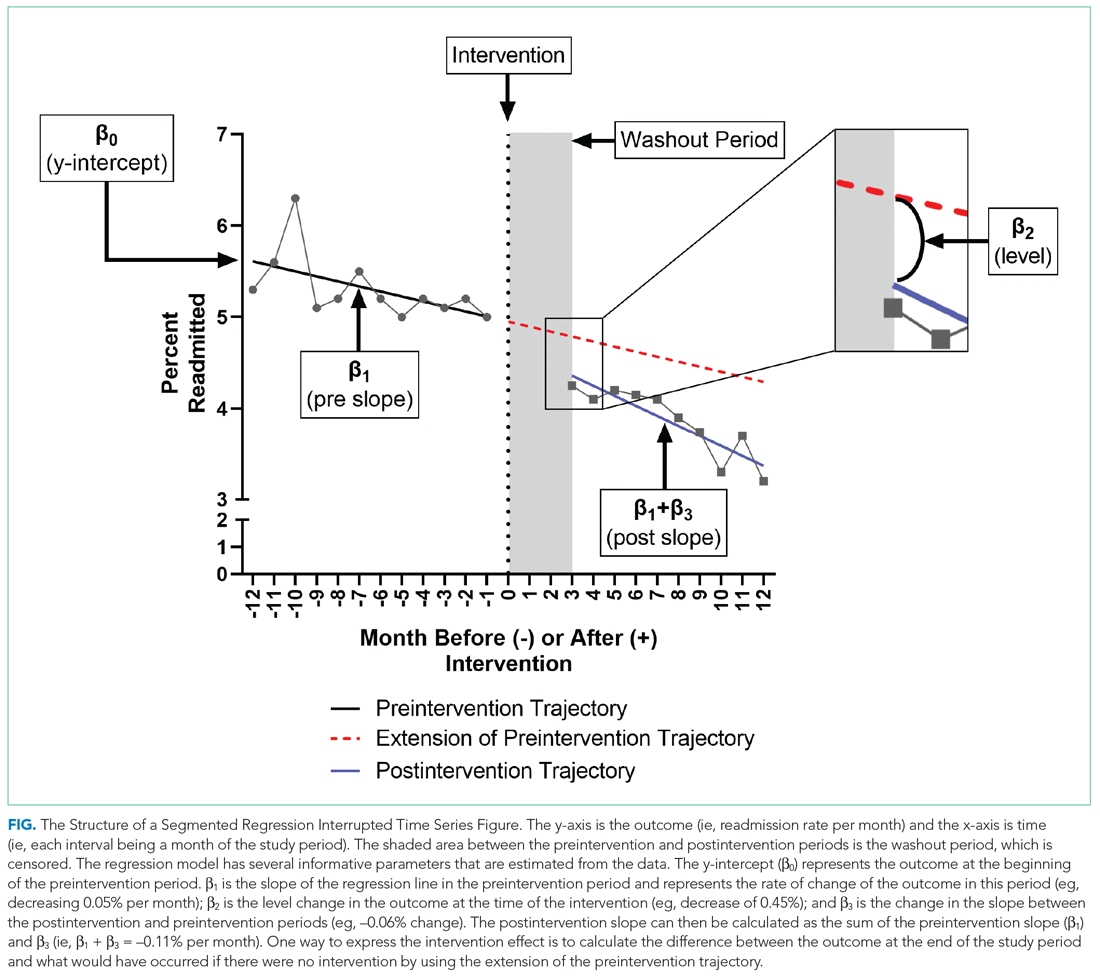

To further explain how segmented regression results are presented, in the Figure we detail the structure of a segmented regression figure evaluating the impact of an intervention without a control group. In addition to the regression figure, authors typically provide 95% CIs around the rates, level change, and the difference between the postintervention and preintervention periods, along with P values demonstrating whether the rates, level change, and the differences between period slopes differ significantly from zero.

WHAT ARE THE UNDERLYING ASSUMPTIONS OF THE SEGMENTED REGRESSION ITS?

Segmented regression models assume a linear trend in the outcome. If the outcome follows a nonlinear pattern (eg, exponential spread of a disease during a pandemic), then using different distributions in the modeling or transformations of the data may be necessary. The validity of the comparison between the pre- and postintervention groups relies on the similarity between the populations. When there is imbalance, investigators can consider matching based on important characteristics or applying risk adjustment as necessary. Another important assumption is that the outcome of interest is unchanged in the absence of the intervention. Finally, the analysis assumes that the intervention is fully implemented at the time the postintervention period begins. Often, there is a washout period during which the old approach is stopped and the new approach (the intervention) is being implemented and can easily be taken into account.

WHAT ARE THE STRENGTHS OF THE SEGMENTED REGRESSION ITS?

There are several strengths of the ITS analysis and segmented regression.7,8 First, this approach accounts for a possible secular trend in the outcome measure that may have been present prior to the intervention. For example, investigators might conclude that a readmissions program was effective in reducing readmissions if they found that the mean readmission percentage in the period after the intervention was significantly lower than before using a simple pre/post study design. However, what if the readmission rate was already going down prior to the intervention? Using an ITS approach, they may have found that the rate of readmissions simply continued to decrease after the intervention at the same rate that it was decreasing prior to the intervention and, therefore, conclude that the intervention was not effective. Second, because the ITS approach evaluates changes in rates of an outcome at a population level, confounding by individual-level variables will not introduce serious bias unless the confounding occurred at the same time as the intervention. Third, ITS can be used to measure the unintended consequences of interventions or events, and investigators can construct separate time-series analyses for different outcomes. Fourth, ITS can be used to evaluate the impact of the intervention on subpopulations (eg, those grouped by age, sex, race) by conducting stratified analysis. Fifth, ITS provides simple and clear graphical results that can be easily understood by various audiences.

WHAT ARE THE IMPORTANT LIMITATIONS OF AN ITS?

By accounting for preintervention trends, ITS studies permit stronger causal inference than do cross-sectional or simple pre/post QEDs, but they may by prone to confounding by cointerventions or by changes in the population composition. Causal inference based on the ITS analysis is only valid to the extent to which the intervention was the only thing that changed at the point in time between the preintervention and postintervention periods. It is important for investigators to consider this in the design and discuss any coincident interventions. If there are multiple interventions over time, it is possible to account for these changes in the study design by creating multiple points of interruption provided there are sufficient measurements of the outcome between interventions. If the composition of the population changes at the same time as the intervention, this introduces bias. Changes in the ability to measure the outcome or changes to its definition also threaten the validity of the study’s inferences. Finally, it is also important to remember that when the outcome is a population-level measurement, inferences about individual-level outcomes are inappropriate due to ecological fallacies (ie, when inferences about individuals are deduced from inferences about the group to which those individuals belong). For example, Coon et al found that infants with bronchiolitis in the ward-based high-flow nasal cannula protocol group had greater ICU admission rates. It would be inappropriate to conclude that, based on this, an individual infant in a hospital on a ward-based protocol is more likely to be admitted to the ICU.

CONCLUSION

Studies evaluating interventions and events are important for informing healthcare practice, policy, and public health. While an RCT is the preferred method for such evaluations, investigators must often consider alternative study designs when an RCT is not feasible or when more real-world outcome evaluation is desired. Quasi-experimental designs are employed in studies that do not use randomization to study the impact of interventions in real-world settings, and an interrupted time series is a strong QED for the evaluation of interventions and natural experiments.

1. Coon ER, Stoddard G, Brady PW. Intensive care unit utilization after adoption of a ward-based high flow nasal cannula protocol. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(6):325-330. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3417

2. Handley MA, Lyles CR, McCulloch C, Cattamanchi A. Selecting and improving quasi-experimental designs in effectiveness and implementation research. Annu Rev Public Health. 2018;39:5-25. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040617-014128

3. Craig P, Katikireddi SV, Leyland A, Popham F. Natural experiments: an overview of methods, approaches, and contributions to public health intervention research. Annu Rev Public Health. 2017;38:39-56. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031816-044327

4. Craig P, Cooper C, Gunnell D, et al. Using natural experiments to evaluate population health interventions: new Medical Research Council guidance. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2012;66(12):1182-1186. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2011-200375

5. Coly A, Parry G. Evaluating Complex Health Interventions: A Guide to Rigorous Research Designs. AcademyHealth; 2017.

6. Orenstein EW, Rasooly IR, Mai MV, et al. Influence of simulation on electronic health record use patterns among pediatric residents. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2018;25(11):1501-1506. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocy105

7. Penfold RB, Zhang F. Use of interrupted time series analysis in evaluating health care quality improvements. Acad Pediatr. 2013;13(6 Suppl):S38-S44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2013.08.002

8. Wagner AK, Soumerai SB, Zhang F, Ross‐Degnan D. Segmented regression analysis of interrupted time series studies in medication use research. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2002;27(4):299-309. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2710.2002.00430.x

9. Desai NR, Ross JS, Kwon JY, et al. Association between hospital penalty status under the hospital readmission reduction program and readmission rates for target and nontarget conditions. JAMA. 2016;316(24):2647-2656. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.18533

10. Kahn JM, Davis BS, Yabes JG, et al. Association between state-mandated protocolized sepsis care and in-hospital mortality among adults with sepsis. JAMA. 2019;322(3):240-250. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2019.9021

11. Volpp KG, Rosen AK, Rosenbaum PR, et al. Mortality among hospitalized Medicare beneficiaries in the first 2 years following ACGME resident duty hour reform. JAMA. 2007;298(9):975-983. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.298.9.975

12. Destino L, Bennett D, Wood M, et al. Improving patient flow: analysis of an initiative to improve early discharge. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(1):22-27. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3133

13. Williams DJ, Hall M, Gerber JS, et al; Pediatric Research in Inpatient Settings Network. Impact of a national guideline on antibiotic selection for hospitalized pneumonia. Pediatrics. 2017;139(4):e20163231. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-3231

Hospital medicine research often asks the question whether an intervention, such as a policy or guideline, has improved quality of care and/or whether there were any unintended consequences. Alternatively, investigators may be interested in understanding the impact of an event, such as a natural disaster or a pandemic, on hospital care. The study design that provides the best estimate of the causal effect of the intervention is the randomized controlled trial (RCT). The goal of randomization, which can be implemented at the patient or cluster level (eg, hospitals), is attaining a balance of the known and unknown confounders between study groups.

However, an RCT may not be feasible for several reasons: complexity, insufficient setup time or funding, ethical barriers to randomization, unwillingness of funders or payers to withhold the intervention from patients (ie, the control group), or anticipated contamination of the intervention into the control group (eg, provider practice change interventions). In addition, it may be impossible to conduct an RCT because the investigator does not have control over the design of an intervention or because they are studying an event, such as a pandemic.

In the June 2020 issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, Coon et al1 use a type of quasi-experimental design (QED)—specifically, the interrupted time series (ITS)—to examine the impact of the adoption of ward-based high-flow nasal cannula protocols on intensive care unit (ICU) admission for bronchiolitis at children’s hospitals. In this methodologic progress note, we discuss QEDs for evaluating the impact of healthcare interventions or events and focus on ITS, one of the strongest QEDs.

WHAT IS A QUASI-EXPERIMENTAL DESIGN?

Quasi-experimental design refers to a broad range of nonrandomized or partially randomized pre- vs postintervention studies.2 In order to test a causal hypothesis without randomization, QEDs define a comparison group or a time period in which an intervention has not been implemented, as well as at least one group or time period in which an intervention has been implemented. In a QED, the control may lack similarity with the intervention group or time period because of differences in the patients, sites, or time period (sometimes referred to as having a “nonequivalent control group”). Several design and analytic approaches are available to enhance the extent to which the study is able to make conclusions about the causal impact of the intervention.2,3 Because randomization is not necessary, QEDs allow for inclusion of a broader population than that which is feasible by RCTs, which increases the applicability and generalizability of the results. Therefore, they are a powerful research design to test the effectiveness of interventions in real-world settings.

The choice of which QED depends on whether the investigators are conducting a prospective evaluation and have control over the study design (ie, the ordering of the intervention, selection of sites or individuals, and/or timing and frequency of the data collection) or whether the investigators do not have control over the intervention, which is also known as a “natural experiment.”4,5 Some studies may also incorporate two QEDs in tandem.6 The Table provides a brief summary of different QEDs, ordered by methodologic strength, and distinguishes those that can be used to study natural experiments. In the study by Coon et al,1 an ITS is used as opposed to a methodologically stronger QED, such as the stepped-wedge design, because the investigators did not have control over the rollout of heated high-flow nasal canula protocols across hospitals.

WHAT IS AN INTERRUPTED TIME SERIES?

Interrupted time series designs use repeated observations of an outcome over time. This method then divides, or “interrupts,” the series of data into two time periods: before the intervention or event and after. Using data from the preintervention period, an underlying trend in the outcome is estimated and assumed to continue forward into the postintervention period to estimate what would have occurred without the intervention. Any significant change in the outcome at the beginning of the postintervention period or change in the trend in the postintervention is then attributed to the intervention.

There are several important methodologic considerations when designing an ITS study, as detailed in other review papers.2,3,7,8 An ITS design can be retrospective or prospective. It can be of a single center or include multiple sites, as in Coon et al. It can be conducted with or without a control. The inclusion of a control, when appropriately chosen, improves the strength of the study design because it can account for seasonal trends and potential confounders that vary over time. The control can be a different group of hospitals or participants that are similar but did not receive the intervention, or it can be a different outcome in the same group of hospitals or participants that are not expected to be affected by the intervention. The ITS design may also be set up to estimate the individual effects of multicomponent interventions. If the different components are phased in sequentially over time, then it may be possible to interrupt the time series at these points and estimate the impact of each intervention component.

Other examples of ITS studies in hospital medicine include those that evaluated the impact of a readmission-reduction program,9 of state sepsis regulations on in-hospital mortality,10 of resident duty-hour reform on mortality among hospitalized patients,11 of a quality-improvement initiative on early discharge,12 and of national guidelines on pediatric pneumonia antibiotic selection.13 There are several types of ITS analysis, and in this article, we focus on segmented regression without a control group.7,8

WHAT IS A SEGMENTED REGRESSION ITS?

Segmented regression is the statistical model used to measure (a) the immediate change in the outcome (level) at the start of the intervention and (b) the change in the trend of the outcome (slope) in the postintervention period vs that in the preintervention period. Therefore, the intervention effect size is expressed in terms of the level change and the slope change. To function properly, the models require several repeated (eg, monthly) measurements of the outcome before and after the intervention. Some experts suggest a minimum of 4 to 12 observations, depending on a number of factors including the stability of the outcome and seasonal variations.7,8 If changes before and after more than one intervention are being examined, there should be the minimum number of observations separating them. Unlike typical regression models, time-series models can correct for autocorrelation if it is present in the data. Autocorrelation is the type of correlation that arises when data are collected over time, with those closest in time being more strongly correlated (there are also other types of autocorrelation, such as seasonal patterns). Using available statistical software, autocorrelation can be detected and, if present, it can be controlled for in the segmented regression models.

HOW ARE SEGMENTED REGRESSION RESULTS PRESENTED?

Coon et al present results of their ITS analysis in a panel of figures detailing each study outcome, ICU admission, ICU length of stay, total length of stay, and rates of mechanical ventilation. Each panel shows the rate of change in the outcome per season across hospitals, before and after adoption of heated high-flow nasal cannula protocols, and the level change at the time of adoption.

To further explain how segmented regression results are presented, in the Figure we detail the structure of a segmented regression figure evaluating the impact of an intervention without a control group. In addition to the regression figure, authors typically provide 95% CIs around the rates, level change, and the difference between the postintervention and preintervention periods, along with P values demonstrating whether the rates, level change, and the differences between period slopes differ significantly from zero.

WHAT ARE THE UNDERLYING ASSUMPTIONS OF THE SEGMENTED REGRESSION ITS?

Segmented regression models assume a linear trend in the outcome. If the outcome follows a nonlinear pattern (eg, exponential spread of a disease during a pandemic), then using different distributions in the modeling or transformations of the data may be necessary. The validity of the comparison between the pre- and postintervention groups relies on the similarity between the populations. When there is imbalance, investigators can consider matching based on important characteristics or applying risk adjustment as necessary. Another important assumption is that the outcome of interest is unchanged in the absence of the intervention. Finally, the analysis assumes that the intervention is fully implemented at the time the postintervention period begins. Often, there is a washout period during which the old approach is stopped and the new approach (the intervention) is being implemented and can easily be taken into account.

WHAT ARE THE STRENGTHS OF THE SEGMENTED REGRESSION ITS?

There are several strengths of the ITS analysis and segmented regression.7,8 First, this approach accounts for a possible secular trend in the outcome measure that may have been present prior to the intervention. For example, investigators might conclude that a readmissions program was effective in reducing readmissions if they found that the mean readmission percentage in the period after the intervention was significantly lower than before using a simple pre/post study design. However, what if the readmission rate was already going down prior to the intervention? Using an ITS approach, they may have found that the rate of readmissions simply continued to decrease after the intervention at the same rate that it was decreasing prior to the intervention and, therefore, conclude that the intervention was not effective. Second, because the ITS approach evaluates changes in rates of an outcome at a population level, confounding by individual-level variables will not introduce serious bias unless the confounding occurred at the same time as the intervention. Third, ITS can be used to measure the unintended consequences of interventions or events, and investigators can construct separate time-series analyses for different outcomes. Fourth, ITS can be used to evaluate the impact of the intervention on subpopulations (eg, those grouped by age, sex, race) by conducting stratified analysis. Fifth, ITS provides simple and clear graphical results that can be easily understood by various audiences.

WHAT ARE THE IMPORTANT LIMITATIONS OF AN ITS?

By accounting for preintervention trends, ITS studies permit stronger causal inference than do cross-sectional or simple pre/post QEDs, but they may by prone to confounding by cointerventions or by changes in the population composition. Causal inference based on the ITS analysis is only valid to the extent to which the intervention was the only thing that changed at the point in time between the preintervention and postintervention periods. It is important for investigators to consider this in the design and discuss any coincident interventions. If there are multiple interventions over time, it is possible to account for these changes in the study design by creating multiple points of interruption provided there are sufficient measurements of the outcome between interventions. If the composition of the population changes at the same time as the intervention, this introduces bias. Changes in the ability to measure the outcome or changes to its definition also threaten the validity of the study’s inferences. Finally, it is also important to remember that when the outcome is a population-level measurement, inferences about individual-level outcomes are inappropriate due to ecological fallacies (ie, when inferences about individuals are deduced from inferences about the group to which those individuals belong). For example, Coon et al found that infants with bronchiolitis in the ward-based high-flow nasal cannula protocol group had greater ICU admission rates. It would be inappropriate to conclude that, based on this, an individual infant in a hospital on a ward-based protocol is more likely to be admitted to the ICU.

CONCLUSION

Studies evaluating interventions and events are important for informing healthcare practice, policy, and public health. While an RCT is the preferred method for such evaluations, investigators must often consider alternative study designs when an RCT is not feasible or when more real-world outcome evaluation is desired. Quasi-experimental designs are employed in studies that do not use randomization to study the impact of interventions in real-world settings, and an interrupted time series is a strong QED for the evaluation of interventions and natural experiments.

Hospital medicine research often asks the question whether an intervention, such as a policy or guideline, has improved quality of care and/or whether there were any unintended consequences. Alternatively, investigators may be interested in understanding the impact of an event, such as a natural disaster or a pandemic, on hospital care. The study design that provides the best estimate of the causal effect of the intervention is the randomized controlled trial (RCT). The goal of randomization, which can be implemented at the patient or cluster level (eg, hospitals), is attaining a balance of the known and unknown confounders between study groups.

However, an RCT may not be feasible for several reasons: complexity, insufficient setup time or funding, ethical barriers to randomization, unwillingness of funders or payers to withhold the intervention from patients (ie, the control group), or anticipated contamination of the intervention into the control group (eg, provider practice change interventions). In addition, it may be impossible to conduct an RCT because the investigator does not have control over the design of an intervention or because they are studying an event, such as a pandemic.

In the June 2020 issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, Coon et al1 use a type of quasi-experimental design (QED)—specifically, the interrupted time series (ITS)—to examine the impact of the adoption of ward-based high-flow nasal cannula protocols on intensive care unit (ICU) admission for bronchiolitis at children’s hospitals. In this methodologic progress note, we discuss QEDs for evaluating the impact of healthcare interventions or events and focus on ITS, one of the strongest QEDs.

WHAT IS A QUASI-EXPERIMENTAL DESIGN?

Quasi-experimental design refers to a broad range of nonrandomized or partially randomized pre- vs postintervention studies.2 In order to test a causal hypothesis without randomization, QEDs define a comparison group or a time period in which an intervention has not been implemented, as well as at least one group or time period in which an intervention has been implemented. In a QED, the control may lack similarity with the intervention group or time period because of differences in the patients, sites, or time period (sometimes referred to as having a “nonequivalent control group”). Several design and analytic approaches are available to enhance the extent to which the study is able to make conclusions about the causal impact of the intervention.2,3 Because randomization is not necessary, QEDs allow for inclusion of a broader population than that which is feasible by RCTs, which increases the applicability and generalizability of the results. Therefore, they are a powerful research design to test the effectiveness of interventions in real-world settings.

The choice of which QED depends on whether the investigators are conducting a prospective evaluation and have control over the study design (ie, the ordering of the intervention, selection of sites or individuals, and/or timing and frequency of the data collection) or whether the investigators do not have control over the intervention, which is also known as a “natural experiment.”4,5 Some studies may also incorporate two QEDs in tandem.6 The Table provides a brief summary of different QEDs, ordered by methodologic strength, and distinguishes those that can be used to study natural experiments. In the study by Coon et al,1 an ITS is used as opposed to a methodologically stronger QED, such as the stepped-wedge design, because the investigators did not have control over the rollout of heated high-flow nasal canula protocols across hospitals.

WHAT IS AN INTERRUPTED TIME SERIES?

Interrupted time series designs use repeated observations of an outcome over time. This method then divides, or “interrupts,” the series of data into two time periods: before the intervention or event and after. Using data from the preintervention period, an underlying trend in the outcome is estimated and assumed to continue forward into the postintervention period to estimate what would have occurred without the intervention. Any significant change in the outcome at the beginning of the postintervention period or change in the trend in the postintervention is then attributed to the intervention.

There are several important methodologic considerations when designing an ITS study, as detailed in other review papers.2,3,7,8 An ITS design can be retrospective or prospective. It can be of a single center or include multiple sites, as in Coon et al. It can be conducted with or without a control. The inclusion of a control, when appropriately chosen, improves the strength of the study design because it can account for seasonal trends and potential confounders that vary over time. The control can be a different group of hospitals or participants that are similar but did not receive the intervention, or it can be a different outcome in the same group of hospitals or participants that are not expected to be affected by the intervention. The ITS design may also be set up to estimate the individual effects of multicomponent interventions. If the different components are phased in sequentially over time, then it may be possible to interrupt the time series at these points and estimate the impact of each intervention component.

Other examples of ITS studies in hospital medicine include those that evaluated the impact of a readmission-reduction program,9 of state sepsis regulations on in-hospital mortality,10 of resident duty-hour reform on mortality among hospitalized patients,11 of a quality-improvement initiative on early discharge,12 and of national guidelines on pediatric pneumonia antibiotic selection.13 There are several types of ITS analysis, and in this article, we focus on segmented regression without a control group.7,8

WHAT IS A SEGMENTED REGRESSION ITS?

Segmented regression is the statistical model used to measure (a) the immediate change in the outcome (level) at the start of the intervention and (b) the change in the trend of the outcome (slope) in the postintervention period vs that in the preintervention period. Therefore, the intervention effect size is expressed in terms of the level change and the slope change. To function properly, the models require several repeated (eg, monthly) measurements of the outcome before and after the intervention. Some experts suggest a minimum of 4 to 12 observations, depending on a number of factors including the stability of the outcome and seasonal variations.7,8 If changes before and after more than one intervention are being examined, there should be the minimum number of observations separating them. Unlike typical regression models, time-series models can correct for autocorrelation if it is present in the data. Autocorrelation is the type of correlation that arises when data are collected over time, with those closest in time being more strongly correlated (there are also other types of autocorrelation, such as seasonal patterns). Using available statistical software, autocorrelation can be detected and, if present, it can be controlled for in the segmented regression models.

HOW ARE SEGMENTED REGRESSION RESULTS PRESENTED?

Coon et al present results of their ITS analysis in a panel of figures detailing each study outcome, ICU admission, ICU length of stay, total length of stay, and rates of mechanical ventilation. Each panel shows the rate of change in the outcome per season across hospitals, before and after adoption of heated high-flow nasal cannula protocols, and the level change at the time of adoption.

To further explain how segmented regression results are presented, in the Figure we detail the structure of a segmented regression figure evaluating the impact of an intervention without a control group. In addition to the regression figure, authors typically provide 95% CIs around the rates, level change, and the difference between the postintervention and preintervention periods, along with P values demonstrating whether the rates, level change, and the differences between period slopes differ significantly from zero.

WHAT ARE THE UNDERLYING ASSUMPTIONS OF THE SEGMENTED REGRESSION ITS?

Segmented regression models assume a linear trend in the outcome. If the outcome follows a nonlinear pattern (eg, exponential spread of a disease during a pandemic), then using different distributions in the modeling or transformations of the data may be necessary. The validity of the comparison between the pre- and postintervention groups relies on the similarity between the populations. When there is imbalance, investigators can consider matching based on important characteristics or applying risk adjustment as necessary. Another important assumption is that the outcome of interest is unchanged in the absence of the intervention. Finally, the analysis assumes that the intervention is fully implemented at the time the postintervention period begins. Often, there is a washout period during which the old approach is stopped and the new approach (the intervention) is being implemented and can easily be taken into account.

WHAT ARE THE STRENGTHS OF THE SEGMENTED REGRESSION ITS?

There are several strengths of the ITS analysis and segmented regression.7,8 First, this approach accounts for a possible secular trend in the outcome measure that may have been present prior to the intervention. For example, investigators might conclude that a readmissions program was effective in reducing readmissions if they found that the mean readmission percentage in the period after the intervention was significantly lower than before using a simple pre/post study design. However, what if the readmission rate was already going down prior to the intervention? Using an ITS approach, they may have found that the rate of readmissions simply continued to decrease after the intervention at the same rate that it was decreasing prior to the intervention and, therefore, conclude that the intervention was not effective. Second, because the ITS approach evaluates changes in rates of an outcome at a population level, confounding by individual-level variables will not introduce serious bias unless the confounding occurred at the same time as the intervention. Third, ITS can be used to measure the unintended consequences of interventions or events, and investigators can construct separate time-series analyses for different outcomes. Fourth, ITS can be used to evaluate the impact of the intervention on subpopulations (eg, those grouped by age, sex, race) by conducting stratified analysis. Fifth, ITS provides simple and clear graphical results that can be easily understood by various audiences.

WHAT ARE THE IMPORTANT LIMITATIONS OF AN ITS?

By accounting for preintervention trends, ITS studies permit stronger causal inference than do cross-sectional or simple pre/post QEDs, but they may by prone to confounding by cointerventions or by changes in the population composition. Causal inference based on the ITS analysis is only valid to the extent to which the intervention was the only thing that changed at the point in time between the preintervention and postintervention periods. It is important for investigators to consider this in the design and discuss any coincident interventions. If there are multiple interventions over time, it is possible to account for these changes in the study design by creating multiple points of interruption provided there are sufficient measurements of the outcome between interventions. If the composition of the population changes at the same time as the intervention, this introduces bias. Changes in the ability to measure the outcome or changes to its definition also threaten the validity of the study’s inferences. Finally, it is also important to remember that when the outcome is a population-level measurement, inferences about individual-level outcomes are inappropriate due to ecological fallacies (ie, when inferences about individuals are deduced from inferences about the group to which those individuals belong). For example, Coon et al found that infants with bronchiolitis in the ward-based high-flow nasal cannula protocol group had greater ICU admission rates. It would be inappropriate to conclude that, based on this, an individual infant in a hospital on a ward-based protocol is more likely to be admitted to the ICU.

CONCLUSION

Studies evaluating interventions and events are important for informing healthcare practice, policy, and public health. While an RCT is the preferred method for such evaluations, investigators must often consider alternative study designs when an RCT is not feasible or when more real-world outcome evaluation is desired. Quasi-experimental designs are employed in studies that do not use randomization to study the impact of interventions in real-world settings, and an interrupted time series is a strong QED for the evaluation of interventions and natural experiments.

1. Coon ER, Stoddard G, Brady PW. Intensive care unit utilization after adoption of a ward-based high flow nasal cannula protocol. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(6):325-330. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3417

2. Handley MA, Lyles CR, McCulloch C, Cattamanchi A. Selecting and improving quasi-experimental designs in effectiveness and implementation research. Annu Rev Public Health. 2018;39:5-25. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040617-014128

3. Craig P, Katikireddi SV, Leyland A, Popham F. Natural experiments: an overview of methods, approaches, and contributions to public health intervention research. Annu Rev Public Health. 2017;38:39-56. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031816-044327

4. Craig P, Cooper C, Gunnell D, et al. Using natural experiments to evaluate population health interventions: new Medical Research Council guidance. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2012;66(12):1182-1186. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2011-200375

5. Coly A, Parry G. Evaluating Complex Health Interventions: A Guide to Rigorous Research Designs. AcademyHealth; 2017.

6. Orenstein EW, Rasooly IR, Mai MV, et al. Influence of simulation on electronic health record use patterns among pediatric residents. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2018;25(11):1501-1506. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocy105

7. Penfold RB, Zhang F. Use of interrupted time series analysis in evaluating health care quality improvements. Acad Pediatr. 2013;13(6 Suppl):S38-S44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2013.08.002

8. Wagner AK, Soumerai SB, Zhang F, Ross‐Degnan D. Segmented regression analysis of interrupted time series studies in medication use research. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2002;27(4):299-309. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2710.2002.00430.x

9. Desai NR, Ross JS, Kwon JY, et al. Association between hospital penalty status under the hospital readmission reduction program and readmission rates for target and nontarget conditions. JAMA. 2016;316(24):2647-2656. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.18533

10. Kahn JM, Davis BS, Yabes JG, et al. Association between state-mandated protocolized sepsis care and in-hospital mortality among adults with sepsis. JAMA. 2019;322(3):240-250. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2019.9021

11. Volpp KG, Rosen AK, Rosenbaum PR, et al. Mortality among hospitalized Medicare beneficiaries in the first 2 years following ACGME resident duty hour reform. JAMA. 2007;298(9):975-983. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.298.9.975

12. Destino L, Bennett D, Wood M, et al. Improving patient flow: analysis of an initiative to improve early discharge. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(1):22-27. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3133

13. Williams DJ, Hall M, Gerber JS, et al; Pediatric Research in Inpatient Settings Network. Impact of a national guideline on antibiotic selection for hospitalized pneumonia. Pediatrics. 2017;139(4):e20163231. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-3231

1. Coon ER, Stoddard G, Brady PW. Intensive care unit utilization after adoption of a ward-based high flow nasal cannula protocol. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(6):325-330. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3417

2. Handley MA, Lyles CR, McCulloch C, Cattamanchi A. Selecting and improving quasi-experimental designs in effectiveness and implementation research. Annu Rev Public Health. 2018;39:5-25. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040617-014128

3. Craig P, Katikireddi SV, Leyland A, Popham F. Natural experiments: an overview of methods, approaches, and contributions to public health intervention research. Annu Rev Public Health. 2017;38:39-56. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031816-044327

4. Craig P, Cooper C, Gunnell D, et al. Using natural experiments to evaluate population health interventions: new Medical Research Council guidance. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2012;66(12):1182-1186. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2011-200375

5. Coly A, Parry G. Evaluating Complex Health Interventions: A Guide to Rigorous Research Designs. AcademyHealth; 2017.

6. Orenstein EW, Rasooly IR, Mai MV, et al. Influence of simulation on electronic health record use patterns among pediatric residents. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2018;25(11):1501-1506. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocy105

7. Penfold RB, Zhang F. Use of interrupted time series analysis in evaluating health care quality improvements. Acad Pediatr. 2013;13(6 Suppl):S38-S44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2013.08.002

8. Wagner AK, Soumerai SB, Zhang F, Ross‐Degnan D. Segmented regression analysis of interrupted time series studies in medication use research. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2002;27(4):299-309. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2710.2002.00430.x

9. Desai NR, Ross JS, Kwon JY, et al. Association between hospital penalty status under the hospital readmission reduction program and readmission rates for target and nontarget conditions. JAMA. 2016;316(24):2647-2656. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.18533

10. Kahn JM, Davis BS, Yabes JG, et al. Association between state-mandated protocolized sepsis care and in-hospital mortality among adults with sepsis. JAMA. 2019;322(3):240-250. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2019.9021

11. Volpp KG, Rosen AK, Rosenbaum PR, et al. Mortality among hospitalized Medicare beneficiaries in the first 2 years following ACGME resident duty hour reform. JAMA. 2007;298(9):975-983. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.298.9.975

12. Destino L, Bennett D, Wood M, et al. Improving patient flow: analysis of an initiative to improve early discharge. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(1):22-27. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3133

13. Williams DJ, Hall M, Gerber JS, et al; Pediatric Research in Inpatient Settings Network. Impact of a national guideline on antibiotic selection for hospitalized pneumonia. Pediatrics. 2017;139(4):e20163231. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-3231

© 2021 Society of Hospital Medicine

Choosing Wisely® in Pediatric Hospital Medicine: Time to Celebrate?

The Choosing Wisely® campaign, launched in 2012 by the American Board of Internal Medicine, aims to reduce overuse of tests and treatments that do not add value for patients. The campaign has caught the attention of the medical profession and spread internationally. Over the last seven years, most specialty societies have published specific recommendations on what tests and treatments clinicians should stop doing. However, has this campaign actually had an impact on the testing and treating behaviors of clinicians?

In this issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, Reyes and colleagues examine changes in five overuse metrics linked with the 2013 Choosing Wisely® Pediatric Hospital Medicine recommendations at 37 children’s hospitals from 2008 to 2017, five years before and after the recommendations were published.1,2 The tests and treatments targeted by these recommendations are not individually costly, but given the high prevalence of the conditions, the cumulative cost is not insignificant. More importantly, reducing the potentially harmful long-term effects of unnecessary radiation and adverse effects from exposure to inappropriate systemic steroids and antacids is a laudable goal. Results from unnecessary tests may also lead to a further cascade of unnecessary testing and/or treatment.3

The authors used an administrative data source, the Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS), to measure billing charges for the tests and medications linked with the overuse measures in over 278,000 hospitalizations. The good news is that overuse declined over the 10-year study period. After adjusting for differences in patient characteristics over time, they observed a substantial absolute reduction in bronchiolitis bronchodilator use (36.6%, from 64% in 2008 to 27.4% in 2017) and chest x-ray (CXR) use (31.5%, from 58.4% to 26.9%). There were also reductions for the other metrics: acid-suppressing medications for gastroesophageal reflux (24.1%, from 63% to 48.9%), asthma CXR use (20.8%, from 52.8% to 32%), and steroids for lower respiratory tract infections (2.9%, from 15.1% to 12.2%). We would not expect the goal for these overuse metrics to be zero percent given the diagnostic uncertainties in real-world clinical decision-making.

The Choosing Wisely® Pediatric Hospital Medicine recommendations, however, were associated with only a modest impact on the overuse decline. A before-and-after interrupted time series analysis showed that the overuse measures were on the downturn prior to the recommendations being published. Then after publication, only the rate of CXR use in asthma decreased immediately. The rate of bronchodilator use for bronchiolitis declined in the following five-year period. There were no changes in the rate of decline in overuse for the other tests and treatments associated with the recommendations.

With such a widespread national campaign, a control group of hospitals to better understand the specific influence of the Choosing Wisely® recommendations was not possible. The decline in overuse over the 10-year period reported by Reyes et al. is likely due to a combination of efforts at multiple levels—including national society guidelines, local hospital guidelines and pathways, increased awareness by clinicians of the problem of overuse, and focused quality improvement efforts.

The use of the PHIS database provided Reyes et al. a powerful data source to evaluate overuse across a large number of patients and hospitals efficiently. However, there are limitations with administrative data that are important to consider. Detailed clinical data, such as patient disease characteristics and test and treatment indications, are not available, which limits the specificity of these measures. For example, one of the recommendations suggests that gastroesophageal reflux should not be routinely treated with acid suppression therapy. Using administrative data, it is impossible to know whether the use of antacids in hospitalized children with a primary discharge diagnosis code of gastroesophageal reflux was inappropriate or because they failed other treatments in the outpatient setting and/or had complicated disease appropriately warranting treatment. This misclassification would result in an overestimation of overuse. The authors did attempt to minimize the possibility of misclassification by excluding children with comorbidities, those who had longer hospital stays, those admitted to the intensive care unit, and those with greater severity of illness where some of these tests and treatments would be indicated.

While the report by Reyes et al. focuses on Pediatric Hospital Medicine Choosing Wisely®recommendations, it is important to recognize that tests and treatments for conditions like asthma, bronchiolitis, and lower respiratory tract infections are initially performed in the emergency department (ED). Collaboration between the ED and the Hospital Medicine Unit is essential to tackle the issue of overuse.4

The study by Reyes et al. provides a nice description of the trends in the Choosing Wisely®overuse metrics at a group of children’s hospitals and is one of few such reports. The NIH funded, Eliminating Monitor Overuse: pulse oximetry (EMO: SpO2) study is focusing on the 5th Choosing Wisely® Pediatric Hospital Medicine recommendation that was not studied by Reyes.5

So then, with the decline in overuse reported in this study over 10 years, is it time to celebrate? Not yet. There is much work to do in the pursuit of Choosing Wisely®: developing a host of valid measures of overuse in pediatric hospital care, expanding the examination of overuse to community hospitals where the majority of children are hospitalized, and using implementation science theory to de-implement the ingrained practices.

1. Reyes M, Etigner B, Hall M, et al. Impact of the choosing wisely campaign recommendations for hospitalized children on clinical practice: trends from 2008 to 2017 [published online ahead of print September 18, 2019]. J Hosp Medicine. 2020;15(2):124-125. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3291

2. Quinonez RA, Garber MD, Schroeder AR, et al. Choosing wisely in pediatric hospital medicine: five opportunities from improved healthcare value. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(9):479-495. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2064.

3. Schuh S, Lalani A, Allen U, et al. Evaluation of the utility of radiography in acute bronchiolitis. J Pediatr. 2007;150(4):429-433. https://doi.org/16/j.jpeds.2007.01.005.

4. Mussman GM, Lossius M, Wasif F, et al. Multisite emergency department inpatient collaborative to reduce unnecessary bronchiolitis care. Pediatrics. 2018;141(2):e20170830. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-0830.

5. Rasooly IR, Beidas RS, Wolk CB, Barg F, et al. Measuring overuse of continuous pulse oximetry in bronchiolitis and developing strategies for large-scale deimplementation: study protocol for a feasibility trial. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2019;5(1):68. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40814-019-0453-2.

The Choosing Wisely® campaign, launched in 2012 by the American Board of Internal Medicine, aims to reduce overuse of tests and treatments that do not add value for patients. The campaign has caught the attention of the medical profession and spread internationally. Over the last seven years, most specialty societies have published specific recommendations on what tests and treatments clinicians should stop doing. However, has this campaign actually had an impact on the testing and treating behaviors of clinicians?

In this issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, Reyes and colleagues examine changes in five overuse metrics linked with the 2013 Choosing Wisely® Pediatric Hospital Medicine recommendations at 37 children’s hospitals from 2008 to 2017, five years before and after the recommendations were published.1,2 The tests and treatments targeted by these recommendations are not individually costly, but given the high prevalence of the conditions, the cumulative cost is not insignificant. More importantly, reducing the potentially harmful long-term effects of unnecessary radiation and adverse effects from exposure to inappropriate systemic steroids and antacids is a laudable goal. Results from unnecessary tests may also lead to a further cascade of unnecessary testing and/or treatment.3

The authors used an administrative data source, the Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS), to measure billing charges for the tests and medications linked with the overuse measures in over 278,000 hospitalizations. The good news is that overuse declined over the 10-year study period. After adjusting for differences in patient characteristics over time, they observed a substantial absolute reduction in bronchiolitis bronchodilator use (36.6%, from 64% in 2008 to 27.4% in 2017) and chest x-ray (CXR) use (31.5%, from 58.4% to 26.9%). There were also reductions for the other metrics: acid-suppressing medications for gastroesophageal reflux (24.1%, from 63% to 48.9%), asthma CXR use (20.8%, from 52.8% to 32%), and steroids for lower respiratory tract infections (2.9%, from 15.1% to 12.2%). We would not expect the goal for these overuse metrics to be zero percent given the diagnostic uncertainties in real-world clinical decision-making.

The Choosing Wisely® Pediatric Hospital Medicine recommendations, however, were associated with only a modest impact on the overuse decline. A before-and-after interrupted time series analysis showed that the overuse measures were on the downturn prior to the recommendations being published. Then after publication, only the rate of CXR use in asthma decreased immediately. The rate of bronchodilator use for bronchiolitis declined in the following five-year period. There were no changes in the rate of decline in overuse for the other tests and treatments associated with the recommendations.

With such a widespread national campaign, a control group of hospitals to better understand the specific influence of the Choosing Wisely® recommendations was not possible. The decline in overuse over the 10-year period reported by Reyes et al. is likely due to a combination of efforts at multiple levels—including national society guidelines, local hospital guidelines and pathways, increased awareness by clinicians of the problem of overuse, and focused quality improvement efforts.

The use of the PHIS database provided Reyes et al. a powerful data source to evaluate overuse across a large number of patients and hospitals efficiently. However, there are limitations with administrative data that are important to consider. Detailed clinical data, such as patient disease characteristics and test and treatment indications, are not available, which limits the specificity of these measures. For example, one of the recommendations suggests that gastroesophageal reflux should not be routinely treated with acid suppression therapy. Using administrative data, it is impossible to know whether the use of antacids in hospitalized children with a primary discharge diagnosis code of gastroesophageal reflux was inappropriate or because they failed other treatments in the outpatient setting and/or had complicated disease appropriately warranting treatment. This misclassification would result in an overestimation of overuse. The authors did attempt to minimize the possibility of misclassification by excluding children with comorbidities, those who had longer hospital stays, those admitted to the intensive care unit, and those with greater severity of illness where some of these tests and treatments would be indicated.

While the report by Reyes et al. focuses on Pediatric Hospital Medicine Choosing Wisely®recommendations, it is important to recognize that tests and treatments for conditions like asthma, bronchiolitis, and lower respiratory tract infections are initially performed in the emergency department (ED). Collaboration between the ED and the Hospital Medicine Unit is essential to tackle the issue of overuse.4

The study by Reyes et al. provides a nice description of the trends in the Choosing Wisely®overuse metrics at a group of children’s hospitals and is one of few such reports. The NIH funded, Eliminating Monitor Overuse: pulse oximetry (EMO: SpO2) study is focusing on the 5th Choosing Wisely® Pediatric Hospital Medicine recommendation that was not studied by Reyes.5

So then, with the decline in overuse reported in this study over 10 years, is it time to celebrate? Not yet. There is much work to do in the pursuit of Choosing Wisely®: developing a host of valid measures of overuse in pediatric hospital care, expanding the examination of overuse to community hospitals where the majority of children are hospitalized, and using implementation science theory to de-implement the ingrained practices.

The Choosing Wisely® campaign, launched in 2012 by the American Board of Internal Medicine, aims to reduce overuse of tests and treatments that do not add value for patients. The campaign has caught the attention of the medical profession and spread internationally. Over the last seven years, most specialty societies have published specific recommendations on what tests and treatments clinicians should stop doing. However, has this campaign actually had an impact on the testing and treating behaviors of clinicians?

In this issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, Reyes and colleagues examine changes in five overuse metrics linked with the 2013 Choosing Wisely® Pediatric Hospital Medicine recommendations at 37 children’s hospitals from 2008 to 2017, five years before and after the recommendations were published.1,2 The tests and treatments targeted by these recommendations are not individually costly, but given the high prevalence of the conditions, the cumulative cost is not insignificant. More importantly, reducing the potentially harmful long-term effects of unnecessary radiation and adverse effects from exposure to inappropriate systemic steroids and antacids is a laudable goal. Results from unnecessary tests may also lead to a further cascade of unnecessary testing and/or treatment.3

The authors used an administrative data source, the Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS), to measure billing charges for the tests and medications linked with the overuse measures in over 278,000 hospitalizations. The good news is that overuse declined over the 10-year study period. After adjusting for differences in patient characteristics over time, they observed a substantial absolute reduction in bronchiolitis bronchodilator use (36.6%, from 64% in 2008 to 27.4% in 2017) and chest x-ray (CXR) use (31.5%, from 58.4% to 26.9%). There were also reductions for the other metrics: acid-suppressing medications for gastroesophageal reflux (24.1%, from 63% to 48.9%), asthma CXR use (20.8%, from 52.8% to 32%), and steroids for lower respiratory tract infections (2.9%, from 15.1% to 12.2%). We would not expect the goal for these overuse metrics to be zero percent given the diagnostic uncertainties in real-world clinical decision-making.

The Choosing Wisely® Pediatric Hospital Medicine recommendations, however, were associated with only a modest impact on the overuse decline. A before-and-after interrupted time series analysis showed that the overuse measures were on the downturn prior to the recommendations being published. Then after publication, only the rate of CXR use in asthma decreased immediately. The rate of bronchodilator use for bronchiolitis declined in the following five-year period. There were no changes in the rate of decline in overuse for the other tests and treatments associated with the recommendations.

With such a widespread national campaign, a control group of hospitals to better understand the specific influence of the Choosing Wisely® recommendations was not possible. The decline in overuse over the 10-year period reported by Reyes et al. is likely due to a combination of efforts at multiple levels—including national society guidelines, local hospital guidelines and pathways, increased awareness by clinicians of the problem of overuse, and focused quality improvement efforts.

The use of the PHIS database provided Reyes et al. a powerful data source to evaluate overuse across a large number of patients and hospitals efficiently. However, there are limitations with administrative data that are important to consider. Detailed clinical data, such as patient disease characteristics and test and treatment indications, are not available, which limits the specificity of these measures. For example, one of the recommendations suggests that gastroesophageal reflux should not be routinely treated with acid suppression therapy. Using administrative data, it is impossible to know whether the use of antacids in hospitalized children with a primary discharge diagnosis code of gastroesophageal reflux was inappropriate or because they failed other treatments in the outpatient setting and/or had complicated disease appropriately warranting treatment. This misclassification would result in an overestimation of overuse. The authors did attempt to minimize the possibility of misclassification by excluding children with comorbidities, those who had longer hospital stays, those admitted to the intensive care unit, and those with greater severity of illness where some of these tests and treatments would be indicated.

While the report by Reyes et al. focuses on Pediatric Hospital Medicine Choosing Wisely®recommendations, it is important to recognize that tests and treatments for conditions like asthma, bronchiolitis, and lower respiratory tract infections are initially performed in the emergency department (ED). Collaboration between the ED and the Hospital Medicine Unit is essential to tackle the issue of overuse.4

The study by Reyes et al. provides a nice description of the trends in the Choosing Wisely®overuse metrics at a group of children’s hospitals and is one of few such reports. The NIH funded, Eliminating Monitor Overuse: pulse oximetry (EMO: SpO2) study is focusing on the 5th Choosing Wisely® Pediatric Hospital Medicine recommendation that was not studied by Reyes.5

So then, with the decline in overuse reported in this study over 10 years, is it time to celebrate? Not yet. There is much work to do in the pursuit of Choosing Wisely®: developing a host of valid measures of overuse in pediatric hospital care, expanding the examination of overuse to community hospitals where the majority of children are hospitalized, and using implementation science theory to de-implement the ingrained practices.

1. Reyes M, Etigner B, Hall M, et al. Impact of the choosing wisely campaign recommendations for hospitalized children on clinical practice: trends from 2008 to 2017 [published online ahead of print September 18, 2019]. J Hosp Medicine. 2020;15(2):124-125. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3291

2. Quinonez RA, Garber MD, Schroeder AR, et al. Choosing wisely in pediatric hospital medicine: five opportunities from improved healthcare value. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(9):479-495. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2064.

3. Schuh S, Lalani A, Allen U, et al. Evaluation of the utility of radiography in acute bronchiolitis. J Pediatr. 2007;150(4):429-433. https://doi.org/16/j.jpeds.2007.01.005.

4. Mussman GM, Lossius M, Wasif F, et al. Multisite emergency department inpatient collaborative to reduce unnecessary bronchiolitis care. Pediatrics. 2018;141(2):e20170830. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-0830.

5. Rasooly IR, Beidas RS, Wolk CB, Barg F, et al. Measuring overuse of continuous pulse oximetry in bronchiolitis and developing strategies for large-scale deimplementation: study protocol for a feasibility trial. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2019;5(1):68. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40814-019-0453-2.

1. Reyes M, Etigner B, Hall M, et al. Impact of the choosing wisely campaign recommendations for hospitalized children on clinical practice: trends from 2008 to 2017 [published online ahead of print September 18, 2019]. J Hosp Medicine. 2020;15(2):124-125. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3291

2. Quinonez RA, Garber MD, Schroeder AR, et al. Choosing wisely in pediatric hospital medicine: five opportunities from improved healthcare value. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(9):479-495. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2064.

3. Schuh S, Lalani A, Allen U, et al. Evaluation of the utility of radiography in acute bronchiolitis. J Pediatr. 2007;150(4):429-433. https://doi.org/16/j.jpeds.2007.01.005.

4. Mussman GM, Lossius M, Wasif F, et al. Multisite emergency department inpatient collaborative to reduce unnecessary bronchiolitis care. Pediatrics. 2018;141(2):e20170830. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-0830.

5. Rasooly IR, Beidas RS, Wolk CB, Barg F, et al. Measuring overuse of continuous pulse oximetry in bronchiolitis and developing strategies for large-scale deimplementation: study protocol for a feasibility trial. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2019;5(1):68. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40814-019-0453-2.

© 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine