User login

Opportunities and Challenges for Improving the Patient Experience in the Acute and Post–Acute Care Setting Using Patient Portals: The Patient’s Perspective

To realize the vision of patient-centered care, efforts are focusing on engaging patients and “care partners,” often a family caregiver, by using patient-facing technologies.1-4 Web-based patient portals linked to the electronic health record (EHR) provide patients and care partners with the ability to access personal health information online and to communicate with clinicians. In recent years, institutions have been increasing patient portal offerings to improve the patient experience, promote safety, and optimize healthcare delivery.5-7

DRIVERS OF ADOPTION

The adoption of patient portals has been driven by federal incentive programs (Meaningful Use), efforts by the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services, and the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology to improve patient outcomes and the transition toward value-based reimbursement.2,8,9 The vast majority of use has been in ambulatory settings; use for acute care is nascent at best.10 Among hospitalized patients, few bring an internet-enabled computer or mobile device to access personal health records online.11 However, evidence suggests that care partners will use portals on behalf of acutely ill patients.4 As the Caregiver Advise, Record, Enable Act is implemented, hospitals will be required to identify patients’ care partners during hospitalization, inform them when the patient is ready for discharge, and provide self-management instructions during the transition home.12 In this context, understanding how best to leverage acute care patient portals will be important to institutions, clinicians, and vendors.

CURRENT KNOWLEDGE

The literature regarding acute care patient portals is rapidly growing.4,10 Hospitalized patients have unmet information and communication needs, and hospital-based clinicians struggle to meet these needs in a timely manner.13-15 In general, patients feel that using a mobile device to access personal health records has the potential to improve their experience.11 Early studies suggest that acute care patient portals can promote patient-centered communication and collaboration during hospitalization, including in intensive care settings.4,16,17 Furthermore, the use of acute care patient portals can improve perception of safety and quality, decrease anxiety, and increase understanding of health conditions.3,14 Although early evidence is promising, considerable knowledge gaps exist regarding patient outcomes over the acute episode of care.10,18

OUTSTANDING QUESTIONS

A clear area of interest is accessing acute care patient portals via mobile technology to engage patients during recovery from hospitalization.4,11 Although we do not yet know whether use during care transitions will favorably impact outcomes, given the high rate of harm after discharge, this seems likely.19 The few studies evaluating the effect on validated measures of engagement (Patient Activation Measure) and hospital readmissions have not shown demonstrable improvement to date.20,21 Clearly, optimizing acute care patient portals with regard to patient-clinician communication, as well as the type, timing, and format of information delivered, will be necessary to maximize value.4,22

From the patient’s perspective, there is much we can learn.23 Is the information that is presented pertinent, timely, and easy to understand? Will the use of portals detract from face-to-face interactions? Does greater transparency foster more accountability? Achieving an appropriate balance of digital health-information sharing for hospitalized patients is challenging given the sensitivity of patient data when diagnoses are uncertain and treatments are in flux.4,24 These questions must be answered as hospitals implement acute care patient portals.

ACUTE CARE PATIENT PORTAL TASK FORCE

To start addressing knowledge gaps, we established a task force of 21 leading researchers, informatics and policy experts, and clinical leaders. The Acute Care Patient Portal Task Force was a subgroup of the Libretto Consortium, a collaboration of 4 academic medical centers established by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation to design, develop, and implement technologies to engage patients, care partners, and providers in preventing harm in hospital settings. Initially, we were challenged with assessing stakeholders’ perspectives from early adopter institutions. We learned that acute care patient portals must offer an integrated experience across care settings, humanize the patient-clinician relationship, enable equitable access, and align with institutional strategy to promote sustainability.19

Cognitive Support

The opportunities identified include acclimatizing and assimilating to the hospital environment (reviewing policies and patient rights) and facilitating self-education and preparation by linking to personal health information and providing structured guidance at transitions.4 For example, a care partner of an incapacitated patient may watch a video to orient to the intensive care unit, navigate educational content linked to the patient’s admission diagnosis (pneumonia) entered in the EHR, view the timing of an upcoming imaging study (chest computed tomography scan), and complete a standardized checklist prior to discharge.

The main challenges we identified include ensuring accuracy of hospital-, unit-, and patient-level information, addressing information overload, configuring notification and display settings to optimize the user experience, presenting information at an appropriate health literacy level,4,21 and addressing security and privacy concerns when expanding access to family members.24

Respect and Boundaries

Opportunities identified include supporting individual learning styles by using interactive features of mobile devices to improve comprehension for visual, auditory, and tactile learners and reinforcing learning through the use of various types of digital media.25-27 For example, a visual learner may view a video tutorial for a newly prescribed medication. A tactile learner may prefer to use interactive graphical displays that exploit multidimensional touch capabilities of mobile devices to learn about active conditions or an upcoming procedure. An auditory learner may choose to use intelligent personal assistants to navigate their plan of care (“Hey Siri, what is my schedule for today?”). By addressing the learning preferences of patients and time constraints of clinicians, institutions can use acute care patient portals to promote more respectful interactions and collaborative decision-making during important care processes, such as obtaining surgical consent.28,29

We also identified opportunities to facilitate personalization by tailoring educational content and by enabling the use of patient-generated health data collected from wearable devices. For example, patients may prefer to interact with a virtual advocate to review discharge instructions (“Louis” in Project Re-Engineered Discharge) when personalized to their demographics and health literacy level.30-32 Patients may choose to upload step counts from wearable devices so that clinicians can monitor activity goals in preparation for discharge and while recovering afterwards. When supported in these ways, acute care patient portals allow patients to have more meaningful interactions with clinicians about diagnoses, treatments, prognosis, and goals for recovery.

The main challenges we identified include balancing interactions with technology and clinicians, ensuring clinicians understand how patients from different socioeconomic backgrounds use existing and newer technology to enhance self-management, assessing health and technology literacy, and understanding individual preferences for sharing patient-generated health data. Importantly, we must remain vigilant that patients will express concern about overdependence on technology, especially if it detracts from in-person interaction; our panelists emphasized that technology should never replace “human touch.”

Patient and Family Empowerment

The opportunities identified include promoting patient-centered communication by supporting a real-time and asynchronous dialogue among patients, care partners, and care team members (including ambulatory clinicians) while minimizing conversational silos4,33; displaying names, roles, and pictures of all care team members4,34; fostering transparency by sharing clinician documentation in progress notes and sign-outs35; ensuring accountability for a single plan of care spanning shift changes and handoffs, and providing a mechanism to enable real-time feedback.

Hospitalization can be a vulnerable and isolating experience, perpetuated by a lack of timely and coordinated communication with the care team. We identified opportunities to mitigate anxiety by promoting shared understanding when questions require input from multiple clinicians, when team members change, or when patients wish to communicate with their longitudinal ambulatory providers.4,34 For example, inviting patients to review clinicians’ progress notes should stimulate more open and meaningful communication.35 Furthermore, requesting that patients state their wishes, preferences, and goals could improve overall concordance with care team members.36,37 Empowering patients and care partners to voice their concerns, particularly those related to miscommunication, may mitigate harm propagated by handoffs, shift work, and weekend coverage.38,39 While reporting safety concerns represents a novel mechanism to augment medical-error reporting by clinicians alone,23,40 this strategy will be most effective when aligned with standardized communication initiatives (I-PASS) that have been proven to reduce medical errors and preventable adverse events and are being implemented nationally.41 Finally, by leveraging tools that facilitate instantaneous feedback, patients can be empowered to react to their plan (ranking skilled nursing facility options) as it is developed.

The main challenges we identified include managing expectations regarding the use of communication tools, accurately and reliably identifying care team members in the EHR,34 acknowledging patients as equal partners, ensuring patients receive a consistent message about diagnoses and therapies during handoffs and when multiple consultants have conflicting opinions about the plan,37 and addressing patient concerns fairly and respectfully.

RECOMMENDATIONS AND CONCLUSIONS

In summary, the patient-centered themes we identified serve as guiding principles for institutions, clinicians, and vendors who wish to use patient portals to improve the acute and postacute care patient experience. One central message resonates: Patients do not simply want access to their health information and the ability to communicate with the clinicians who furnish this information; they want to feel supported, respected, and empowered when doing so. It is only through partnership with patients and their advocates that we can fully realize the impact of digital technologies when patients are in their most vulnerable state.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank their colleagues and the patient and family advocates who contributed to this body of work as part of the Acute Care Patient Portal Task Force and conference: Brittany Couture; Ronen Rozenblum, PhD, MPH; Jennifer Prey, MPhil, MS, PhD; Kristin O’Reilly, RN, BSN, MPH; Patricia Q. Bourie, RN, MS, Cindy Dwyer, RN, BSN,S; Ryan Greysen, MD, MHS, MA; Jeffery Smith, MPP; Michael Gropper, MD, PhD; Patricia Dykes, RN, PhD; Martha B. Carnie; Jeffrey W. Mello; and Jane Webster.

Disclosure

Anuj K. Dalal, MD, David W. Bates, MD, MSc, and Sarah Collins, RN, PhD, are responsible for the conception or design of the work; acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data; drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content; and final approval of the version to be published. The authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work and to ensure that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. This work was supported by a grant from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation ([GBMF] #4993). GBMF had no role in the design or conduct of the study; the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data; or preparation or review of the manuscript. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of GBMF. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

1. Sarkar U, Bates DW. Care partners and online patient portals. JAMA. 2014;311(4):357-358. PubMed

2. Grando MA, Rozenblum R, Bates DW, eds. Information Technology for Patient Empowerment in Healthcare, 1st Edition. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter Inc.; 2015.

3. Kelly MM, Hoonakker PLT, Dean SM. Using an inpatient portal to engage families in pediatric hospital care. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2016;24(1):153-161. PubMed

4. Dalal AK, Dykes PC, Collins S, et al. A web-based, patient-centered toolkit to engage patients and caregivers in the acute care setting: A preliminary evaluation. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2016;23(1):80-87. PubMed

5. Prey JE, Restaino S, Vawdrey DK. Providing hospital patients with access to their medical records. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2014;2014:1884-1893. PubMed

6. Herrin J, Harris KG, Kenward K, Hines S, Joshi MS, Frosch DL. Patient and family engagement: A survey of US hospital practices. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;25(3):182-189. PubMed

7. Tom JO, Mangione-Smith R, Solomon C, Grossman DC. Integrated personal health record use: Association with parent-reported care experiences. Pediatrics. 2012;130(1):e183-e190. PubMed

8. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), HHS. Medicare and Medicaid Programs; Electronic Health Record Incentive Program-Stage 2. Federal Register Final Rule. Sect. 170; 2012. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2012/03/07/2012-4443/medicare-and-medicaid-programs-electronic-health-record-incentive-program-stage-2. Accessed March 1, 2017.

9. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), HHS. Medicare program; merit-based incentive payment system (MIPS) and alternative payment model (APM) incentive under the physician fee schedule, and criteria for physician-focused payment models. Final rule with comment period. Fed Regist. 2016;81(214):77008-77831. PubMed

10. Prey JE, Woollen J, Wilcox L, et al. Patient engagement in the inpatient setting: A systematic review. J Am Med Informat Assoc. 2014;21(4):742-750. PubMed

11. Ludwin S, Greysen SR. Use of smartphones and mobile devices in hospitalized patients: Untapped opportunities for inpatient engagement. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(7):459-461. PubMed

12. Coleman EA. Family caregivers as partners in care transitions: The caregiver advise record and enable act. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(12):883-885. PubMed

13. Kaziunas E, Hanauer DA, Ackerman MS, Choi SW. Identifying unmet informational needs in the inpatient setting to increase patient and caregiver engagement in the context of pediatric hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2016;23(1):94-104. PubMed

14. Woollen J, Prey J, Wilcox L, et al. Patient experiences using an inpatient personal health record. Appl Clin Inform. 2016;7(2):446-460. PubMed

15. Irizarry T, DeVito Dabbs A, Curran CR. Patient portals and patient engagement: A state of the science review. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17(6):e148. doi:10.2196/jmir.4255. PubMed

16. Vawdrey DK, Wilcox LG, Collins SA, et al. A tablet computer application for patients to participate in their hospital care. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2011;2011:1428-1435. PubMed

17. Collins SA, Rozenblum R, Leung WY, et al. Acute care patient portals: A qualitative study of stakeholder perspectives on current practices. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2016;24(e1):e9-e17. PubMed

18. Berger Z, Flickinger TE, Pfoh E, Martinez KA, Dy SM. Promoting engagement by patients and families to reduce adverse events in acute care settings: A systematic review. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;23(7):548-555. PubMed

19. Forster AJ, Murff HJ, Peterson JF, Gandhi TK, Bates DW. The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(3):161-167. PubMed

20. Griffin A, Skinner A, Thornhill J, Weinberger M. Patient Portals: Who uses them? What features do they use? And do they reduce hospital readmissions? Appl Clin Inform. 2016;7(2):489-501. PubMed

21. O’Leary KJ, Lohman ME, Culver E, Killarney A, Randy Smith G Jr, Liebovitz DM. The effect of tablet computers with a mobile patient portal application on hospitalized patients’ knowledge and activation. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2016;23(1):159-165. PubMed

22. O’Leary KJ, Sharma RK, Killarney A, et al. Patients’ and Healthcare Providers’ Perceptions of a Mobile Portal Application for Hospitalized Patients. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2016;16(1):123. PubMed

23. Pell JM, Mancuso M, Limon S, Oman K, Lin CT. Patient access to electronic health records during hospitalization. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(5):856-858. PubMed

24. Brown SM, Aboumatar HJ, Francis L, et al. Balancing digital information-sharing and patient privacy when engaging families in the intensive care unit. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2016;23(5):995-1000. PubMed

25. Krishna S, Francisco BD, Balas EA, et al. Internet-enabled interactive multimedia asthma education program: A randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2003;111(3):503-510. PubMed

26. Fox MP. A systematic review of the literature reporting on studies that examined the impact of interactive, computer-based patient education programs. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;77(1):6-13. PubMed

27. Morgan ER, Laing K, McCarthy J, McCrate F, Seal MD. Using tablet-based technology in patient education about systemic therapy options for early-stage breast cancer: A pilot study. Curr Oncol. 2015;22(5):e364-e369. PubMed

28. Nehme J, El-Khani U, Chow A, Hakky S, Ahmed AR, Purkayastha S. The use of multimedia consent programs for surgical procedures: A systematic review. Surg Innov. 2013;20(1):13-23. PubMed

29. Waller A, Forshaw K, Carey M, et al. Optimizing patient preparation and surgical experience using eHealth technology. JMIR Med Inform. 2015;3(3):e29. PubMed

30. Abbott MB, Shaw P. Virtual nursing avatars: Nurse roles and evolving concepts of care. Online J Issues Nurs. 2016;21(3):7. PubMed

31. Cawthon C, Walia S, Osborn CY, Niesner KJ, Schnipper JL, Kripalani S. Improving care transitions: The patient perspective. J Health Commun. 2012;17 Suppl 3:312-324. PubMed

32. Bickmore TW, Pfeifer LM, Byron D, et al. Usability of conversational agents by patients with inadequate health literacy: Evidence from two clinical trials. J Health Commun. 2010;15 Suppl 2:197-210. PubMed

33. 2017;376(20):1905-1907. N Engl J Med.42. Mandl KD, Kohane IS. A 21st-century health IT system—creating a real-world information economy. PubMed

34. 2014;371(19):1803-1812.N Engl J Med41. Starmer AJ, Spector ND, Srivastava R, et al. Changes in medical errors after implementation of a handoff program. PubMed

35. 2016;24(1):153-161.J Am Med Inform Assoc.40. Kelly MM, Hoonakker PLT, Dean SM. Using an inpatient portal to engage families in pediatric hospital care. PubMed

36. 2017;171(4):372-381.JAMA Pediatr.39. Khan A, Coffey M, Litterer KP, et al. Families as partners in hospital error and adverse event surveillance. PubMed

37. 2017;17(4):389-402.Acad Pediatr.38. Khan A, Baird J, Rogers JE, et al. Parent and provider experience and shared understanding after a family-centered nighttime communication intervention. PubMed

38. 2016;6(6):319-329.Hosp Pediatr. 37. Khan A, Rogers JE, Forster CS, Furtak SL, Schuster MA, Landrigan CP. Communication and shared understanding between parents and resident-physicians at night. PubMed

39. 2016;11(9):615-619.J Hosp Med36. Figueroa JF, Schnipper JL, McNally K, Stade D, Lipsitz SR, Dalal AK. How often are hospitalized patients and providers on the same page with regard to the patient’s primary recovery goal for hospitalization? PubMed

40. 2013;8(7):414-417.J Hosp Med.35. Feldman HJ, Walker J, Li J, Delbanco T. OpenNotes: Hospitalists’ challenge and opportunity. PubMed

41. 2016;11(5):381-385.J Hosp Med.34. Dalal AK, Schnipper JL. Care team identification in the electronic health record: A critical first step for patient-centered communication.PubMed

42. 2016;24(e1):e178-e184.J Am Med Inform Assoc.33. Dalal AK, Schnipper J, Massaro A, et al. A web-based and mobile patient-centered “microblog” messaging platform to improve care team communication in acute care. PubMed

To realize the vision of patient-centered care, efforts are focusing on engaging patients and “care partners,” often a family caregiver, by using patient-facing technologies.1-4 Web-based patient portals linked to the electronic health record (EHR) provide patients and care partners with the ability to access personal health information online and to communicate with clinicians. In recent years, institutions have been increasing patient portal offerings to improve the patient experience, promote safety, and optimize healthcare delivery.5-7

DRIVERS OF ADOPTION

The adoption of patient portals has been driven by federal incentive programs (Meaningful Use), efforts by the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services, and the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology to improve patient outcomes and the transition toward value-based reimbursement.2,8,9 The vast majority of use has been in ambulatory settings; use for acute care is nascent at best.10 Among hospitalized patients, few bring an internet-enabled computer or mobile device to access personal health records online.11 However, evidence suggests that care partners will use portals on behalf of acutely ill patients.4 As the Caregiver Advise, Record, Enable Act is implemented, hospitals will be required to identify patients’ care partners during hospitalization, inform them when the patient is ready for discharge, and provide self-management instructions during the transition home.12 In this context, understanding how best to leverage acute care patient portals will be important to institutions, clinicians, and vendors.

CURRENT KNOWLEDGE

The literature regarding acute care patient portals is rapidly growing.4,10 Hospitalized patients have unmet information and communication needs, and hospital-based clinicians struggle to meet these needs in a timely manner.13-15 In general, patients feel that using a mobile device to access personal health records has the potential to improve their experience.11 Early studies suggest that acute care patient portals can promote patient-centered communication and collaboration during hospitalization, including in intensive care settings.4,16,17 Furthermore, the use of acute care patient portals can improve perception of safety and quality, decrease anxiety, and increase understanding of health conditions.3,14 Although early evidence is promising, considerable knowledge gaps exist regarding patient outcomes over the acute episode of care.10,18

OUTSTANDING QUESTIONS

A clear area of interest is accessing acute care patient portals via mobile technology to engage patients during recovery from hospitalization.4,11 Although we do not yet know whether use during care transitions will favorably impact outcomes, given the high rate of harm after discharge, this seems likely.19 The few studies evaluating the effect on validated measures of engagement (Patient Activation Measure) and hospital readmissions have not shown demonstrable improvement to date.20,21 Clearly, optimizing acute care patient portals with regard to patient-clinician communication, as well as the type, timing, and format of information delivered, will be necessary to maximize value.4,22

From the patient’s perspective, there is much we can learn.23 Is the information that is presented pertinent, timely, and easy to understand? Will the use of portals detract from face-to-face interactions? Does greater transparency foster more accountability? Achieving an appropriate balance of digital health-information sharing for hospitalized patients is challenging given the sensitivity of patient data when diagnoses are uncertain and treatments are in flux.4,24 These questions must be answered as hospitals implement acute care patient portals.

ACUTE CARE PATIENT PORTAL TASK FORCE

To start addressing knowledge gaps, we established a task force of 21 leading researchers, informatics and policy experts, and clinical leaders. The Acute Care Patient Portal Task Force was a subgroup of the Libretto Consortium, a collaboration of 4 academic medical centers established by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation to design, develop, and implement technologies to engage patients, care partners, and providers in preventing harm in hospital settings. Initially, we were challenged with assessing stakeholders’ perspectives from early adopter institutions. We learned that acute care patient portals must offer an integrated experience across care settings, humanize the patient-clinician relationship, enable equitable access, and align with institutional strategy to promote sustainability.19

Cognitive Support

The opportunities identified include acclimatizing and assimilating to the hospital environment (reviewing policies and patient rights) and facilitating self-education and preparation by linking to personal health information and providing structured guidance at transitions.4 For example, a care partner of an incapacitated patient may watch a video to orient to the intensive care unit, navigate educational content linked to the patient’s admission diagnosis (pneumonia) entered in the EHR, view the timing of an upcoming imaging study (chest computed tomography scan), and complete a standardized checklist prior to discharge.

The main challenges we identified include ensuring accuracy of hospital-, unit-, and patient-level information, addressing information overload, configuring notification and display settings to optimize the user experience, presenting information at an appropriate health literacy level,4,21 and addressing security and privacy concerns when expanding access to family members.24

Respect and Boundaries

Opportunities identified include supporting individual learning styles by using interactive features of mobile devices to improve comprehension for visual, auditory, and tactile learners and reinforcing learning through the use of various types of digital media.25-27 For example, a visual learner may view a video tutorial for a newly prescribed medication. A tactile learner may prefer to use interactive graphical displays that exploit multidimensional touch capabilities of mobile devices to learn about active conditions or an upcoming procedure. An auditory learner may choose to use intelligent personal assistants to navigate their plan of care (“Hey Siri, what is my schedule for today?”). By addressing the learning preferences of patients and time constraints of clinicians, institutions can use acute care patient portals to promote more respectful interactions and collaborative decision-making during important care processes, such as obtaining surgical consent.28,29

We also identified opportunities to facilitate personalization by tailoring educational content and by enabling the use of patient-generated health data collected from wearable devices. For example, patients may prefer to interact with a virtual advocate to review discharge instructions (“Louis” in Project Re-Engineered Discharge) when personalized to their demographics and health literacy level.30-32 Patients may choose to upload step counts from wearable devices so that clinicians can monitor activity goals in preparation for discharge and while recovering afterwards. When supported in these ways, acute care patient portals allow patients to have more meaningful interactions with clinicians about diagnoses, treatments, prognosis, and goals for recovery.

The main challenges we identified include balancing interactions with technology and clinicians, ensuring clinicians understand how patients from different socioeconomic backgrounds use existing and newer technology to enhance self-management, assessing health and technology literacy, and understanding individual preferences for sharing patient-generated health data. Importantly, we must remain vigilant that patients will express concern about overdependence on technology, especially if it detracts from in-person interaction; our panelists emphasized that technology should never replace “human touch.”

Patient and Family Empowerment

The opportunities identified include promoting patient-centered communication by supporting a real-time and asynchronous dialogue among patients, care partners, and care team members (including ambulatory clinicians) while minimizing conversational silos4,33; displaying names, roles, and pictures of all care team members4,34; fostering transparency by sharing clinician documentation in progress notes and sign-outs35; ensuring accountability for a single plan of care spanning shift changes and handoffs, and providing a mechanism to enable real-time feedback.

Hospitalization can be a vulnerable and isolating experience, perpetuated by a lack of timely and coordinated communication with the care team. We identified opportunities to mitigate anxiety by promoting shared understanding when questions require input from multiple clinicians, when team members change, or when patients wish to communicate with their longitudinal ambulatory providers.4,34 For example, inviting patients to review clinicians’ progress notes should stimulate more open and meaningful communication.35 Furthermore, requesting that patients state their wishes, preferences, and goals could improve overall concordance with care team members.36,37 Empowering patients and care partners to voice their concerns, particularly those related to miscommunication, may mitigate harm propagated by handoffs, shift work, and weekend coverage.38,39 While reporting safety concerns represents a novel mechanism to augment medical-error reporting by clinicians alone,23,40 this strategy will be most effective when aligned with standardized communication initiatives (I-PASS) that have been proven to reduce medical errors and preventable adverse events and are being implemented nationally.41 Finally, by leveraging tools that facilitate instantaneous feedback, patients can be empowered to react to their plan (ranking skilled nursing facility options) as it is developed.

The main challenges we identified include managing expectations regarding the use of communication tools, accurately and reliably identifying care team members in the EHR,34 acknowledging patients as equal partners, ensuring patients receive a consistent message about diagnoses and therapies during handoffs and when multiple consultants have conflicting opinions about the plan,37 and addressing patient concerns fairly and respectfully.

RECOMMENDATIONS AND CONCLUSIONS

In summary, the patient-centered themes we identified serve as guiding principles for institutions, clinicians, and vendors who wish to use patient portals to improve the acute and postacute care patient experience. One central message resonates: Patients do not simply want access to their health information and the ability to communicate with the clinicians who furnish this information; they want to feel supported, respected, and empowered when doing so. It is only through partnership with patients and their advocates that we can fully realize the impact of digital technologies when patients are in their most vulnerable state.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank their colleagues and the patient and family advocates who contributed to this body of work as part of the Acute Care Patient Portal Task Force and conference: Brittany Couture; Ronen Rozenblum, PhD, MPH; Jennifer Prey, MPhil, MS, PhD; Kristin O’Reilly, RN, BSN, MPH; Patricia Q. Bourie, RN, MS, Cindy Dwyer, RN, BSN,S; Ryan Greysen, MD, MHS, MA; Jeffery Smith, MPP; Michael Gropper, MD, PhD; Patricia Dykes, RN, PhD; Martha B. Carnie; Jeffrey W. Mello; and Jane Webster.

Disclosure

Anuj K. Dalal, MD, David W. Bates, MD, MSc, and Sarah Collins, RN, PhD, are responsible for the conception or design of the work; acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data; drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content; and final approval of the version to be published. The authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work and to ensure that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. This work was supported by a grant from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation ([GBMF] #4993). GBMF had no role in the design or conduct of the study; the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data; or preparation or review of the manuscript. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of GBMF. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

To realize the vision of patient-centered care, efforts are focusing on engaging patients and “care partners,” often a family caregiver, by using patient-facing technologies.1-4 Web-based patient portals linked to the electronic health record (EHR) provide patients and care partners with the ability to access personal health information online and to communicate with clinicians. In recent years, institutions have been increasing patient portal offerings to improve the patient experience, promote safety, and optimize healthcare delivery.5-7

DRIVERS OF ADOPTION

The adoption of patient portals has been driven by federal incentive programs (Meaningful Use), efforts by the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services, and the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology to improve patient outcomes and the transition toward value-based reimbursement.2,8,9 The vast majority of use has been in ambulatory settings; use for acute care is nascent at best.10 Among hospitalized patients, few bring an internet-enabled computer or mobile device to access personal health records online.11 However, evidence suggests that care partners will use portals on behalf of acutely ill patients.4 As the Caregiver Advise, Record, Enable Act is implemented, hospitals will be required to identify patients’ care partners during hospitalization, inform them when the patient is ready for discharge, and provide self-management instructions during the transition home.12 In this context, understanding how best to leverage acute care patient portals will be important to institutions, clinicians, and vendors.

CURRENT KNOWLEDGE

The literature regarding acute care patient portals is rapidly growing.4,10 Hospitalized patients have unmet information and communication needs, and hospital-based clinicians struggle to meet these needs in a timely manner.13-15 In general, patients feel that using a mobile device to access personal health records has the potential to improve their experience.11 Early studies suggest that acute care patient portals can promote patient-centered communication and collaboration during hospitalization, including in intensive care settings.4,16,17 Furthermore, the use of acute care patient portals can improve perception of safety and quality, decrease anxiety, and increase understanding of health conditions.3,14 Although early evidence is promising, considerable knowledge gaps exist regarding patient outcomes over the acute episode of care.10,18

OUTSTANDING QUESTIONS

A clear area of interest is accessing acute care patient portals via mobile technology to engage patients during recovery from hospitalization.4,11 Although we do not yet know whether use during care transitions will favorably impact outcomes, given the high rate of harm after discharge, this seems likely.19 The few studies evaluating the effect on validated measures of engagement (Patient Activation Measure) and hospital readmissions have not shown demonstrable improvement to date.20,21 Clearly, optimizing acute care patient portals with regard to patient-clinician communication, as well as the type, timing, and format of information delivered, will be necessary to maximize value.4,22

From the patient’s perspective, there is much we can learn.23 Is the information that is presented pertinent, timely, and easy to understand? Will the use of portals detract from face-to-face interactions? Does greater transparency foster more accountability? Achieving an appropriate balance of digital health-information sharing for hospitalized patients is challenging given the sensitivity of patient data when diagnoses are uncertain and treatments are in flux.4,24 These questions must be answered as hospitals implement acute care patient portals.

ACUTE CARE PATIENT PORTAL TASK FORCE

To start addressing knowledge gaps, we established a task force of 21 leading researchers, informatics and policy experts, and clinical leaders. The Acute Care Patient Portal Task Force was a subgroup of the Libretto Consortium, a collaboration of 4 academic medical centers established by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation to design, develop, and implement technologies to engage patients, care partners, and providers in preventing harm in hospital settings. Initially, we were challenged with assessing stakeholders’ perspectives from early adopter institutions. We learned that acute care patient portals must offer an integrated experience across care settings, humanize the patient-clinician relationship, enable equitable access, and align with institutional strategy to promote sustainability.19

Cognitive Support

The opportunities identified include acclimatizing and assimilating to the hospital environment (reviewing policies and patient rights) and facilitating self-education and preparation by linking to personal health information and providing structured guidance at transitions.4 For example, a care partner of an incapacitated patient may watch a video to orient to the intensive care unit, navigate educational content linked to the patient’s admission diagnosis (pneumonia) entered in the EHR, view the timing of an upcoming imaging study (chest computed tomography scan), and complete a standardized checklist prior to discharge.

The main challenges we identified include ensuring accuracy of hospital-, unit-, and patient-level information, addressing information overload, configuring notification and display settings to optimize the user experience, presenting information at an appropriate health literacy level,4,21 and addressing security and privacy concerns when expanding access to family members.24

Respect and Boundaries

Opportunities identified include supporting individual learning styles by using interactive features of mobile devices to improve comprehension for visual, auditory, and tactile learners and reinforcing learning through the use of various types of digital media.25-27 For example, a visual learner may view a video tutorial for a newly prescribed medication. A tactile learner may prefer to use interactive graphical displays that exploit multidimensional touch capabilities of mobile devices to learn about active conditions or an upcoming procedure. An auditory learner may choose to use intelligent personal assistants to navigate their plan of care (“Hey Siri, what is my schedule for today?”). By addressing the learning preferences of patients and time constraints of clinicians, institutions can use acute care patient portals to promote more respectful interactions and collaborative decision-making during important care processes, such as obtaining surgical consent.28,29

We also identified opportunities to facilitate personalization by tailoring educational content and by enabling the use of patient-generated health data collected from wearable devices. For example, patients may prefer to interact with a virtual advocate to review discharge instructions (“Louis” in Project Re-Engineered Discharge) when personalized to their demographics and health literacy level.30-32 Patients may choose to upload step counts from wearable devices so that clinicians can monitor activity goals in preparation for discharge and while recovering afterwards. When supported in these ways, acute care patient portals allow patients to have more meaningful interactions with clinicians about diagnoses, treatments, prognosis, and goals for recovery.

The main challenges we identified include balancing interactions with technology and clinicians, ensuring clinicians understand how patients from different socioeconomic backgrounds use existing and newer technology to enhance self-management, assessing health and technology literacy, and understanding individual preferences for sharing patient-generated health data. Importantly, we must remain vigilant that patients will express concern about overdependence on technology, especially if it detracts from in-person interaction; our panelists emphasized that technology should never replace “human touch.”

Patient and Family Empowerment

The opportunities identified include promoting patient-centered communication by supporting a real-time and asynchronous dialogue among patients, care partners, and care team members (including ambulatory clinicians) while minimizing conversational silos4,33; displaying names, roles, and pictures of all care team members4,34; fostering transparency by sharing clinician documentation in progress notes and sign-outs35; ensuring accountability for a single plan of care spanning shift changes and handoffs, and providing a mechanism to enable real-time feedback.

Hospitalization can be a vulnerable and isolating experience, perpetuated by a lack of timely and coordinated communication with the care team. We identified opportunities to mitigate anxiety by promoting shared understanding when questions require input from multiple clinicians, when team members change, or when patients wish to communicate with their longitudinal ambulatory providers.4,34 For example, inviting patients to review clinicians’ progress notes should stimulate more open and meaningful communication.35 Furthermore, requesting that patients state their wishes, preferences, and goals could improve overall concordance with care team members.36,37 Empowering patients and care partners to voice their concerns, particularly those related to miscommunication, may mitigate harm propagated by handoffs, shift work, and weekend coverage.38,39 While reporting safety concerns represents a novel mechanism to augment medical-error reporting by clinicians alone,23,40 this strategy will be most effective when aligned with standardized communication initiatives (I-PASS) that have been proven to reduce medical errors and preventable adverse events and are being implemented nationally.41 Finally, by leveraging tools that facilitate instantaneous feedback, patients can be empowered to react to their plan (ranking skilled nursing facility options) as it is developed.

The main challenges we identified include managing expectations regarding the use of communication tools, accurately and reliably identifying care team members in the EHR,34 acknowledging patients as equal partners, ensuring patients receive a consistent message about diagnoses and therapies during handoffs and when multiple consultants have conflicting opinions about the plan,37 and addressing patient concerns fairly and respectfully.

RECOMMENDATIONS AND CONCLUSIONS

In summary, the patient-centered themes we identified serve as guiding principles for institutions, clinicians, and vendors who wish to use patient portals to improve the acute and postacute care patient experience. One central message resonates: Patients do not simply want access to their health information and the ability to communicate with the clinicians who furnish this information; they want to feel supported, respected, and empowered when doing so. It is only through partnership with patients and their advocates that we can fully realize the impact of digital technologies when patients are in their most vulnerable state.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank their colleagues and the patient and family advocates who contributed to this body of work as part of the Acute Care Patient Portal Task Force and conference: Brittany Couture; Ronen Rozenblum, PhD, MPH; Jennifer Prey, MPhil, MS, PhD; Kristin O’Reilly, RN, BSN, MPH; Patricia Q. Bourie, RN, MS, Cindy Dwyer, RN, BSN,S; Ryan Greysen, MD, MHS, MA; Jeffery Smith, MPP; Michael Gropper, MD, PhD; Patricia Dykes, RN, PhD; Martha B. Carnie; Jeffrey W. Mello; and Jane Webster.

Disclosure

Anuj K. Dalal, MD, David W. Bates, MD, MSc, and Sarah Collins, RN, PhD, are responsible for the conception or design of the work; acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data; drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content; and final approval of the version to be published. The authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work and to ensure that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. This work was supported by a grant from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation ([GBMF] #4993). GBMF had no role in the design or conduct of the study; the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data; or preparation or review of the manuscript. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of GBMF. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

1. Sarkar U, Bates DW. Care partners and online patient portals. JAMA. 2014;311(4):357-358. PubMed

2. Grando MA, Rozenblum R, Bates DW, eds. Information Technology for Patient Empowerment in Healthcare, 1st Edition. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter Inc.; 2015.

3. Kelly MM, Hoonakker PLT, Dean SM. Using an inpatient portal to engage families in pediatric hospital care. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2016;24(1):153-161. PubMed

4. Dalal AK, Dykes PC, Collins S, et al. A web-based, patient-centered toolkit to engage patients and caregivers in the acute care setting: A preliminary evaluation. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2016;23(1):80-87. PubMed

5. Prey JE, Restaino S, Vawdrey DK. Providing hospital patients with access to their medical records. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2014;2014:1884-1893. PubMed

6. Herrin J, Harris KG, Kenward K, Hines S, Joshi MS, Frosch DL. Patient and family engagement: A survey of US hospital practices. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;25(3):182-189. PubMed

7. Tom JO, Mangione-Smith R, Solomon C, Grossman DC. Integrated personal health record use: Association with parent-reported care experiences. Pediatrics. 2012;130(1):e183-e190. PubMed

8. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), HHS. Medicare and Medicaid Programs; Electronic Health Record Incentive Program-Stage 2. Federal Register Final Rule. Sect. 170; 2012. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2012/03/07/2012-4443/medicare-and-medicaid-programs-electronic-health-record-incentive-program-stage-2. Accessed March 1, 2017.

9. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), HHS. Medicare program; merit-based incentive payment system (MIPS) and alternative payment model (APM) incentive under the physician fee schedule, and criteria for physician-focused payment models. Final rule with comment period. Fed Regist. 2016;81(214):77008-77831. PubMed

10. Prey JE, Woollen J, Wilcox L, et al. Patient engagement in the inpatient setting: A systematic review. J Am Med Informat Assoc. 2014;21(4):742-750. PubMed

11. Ludwin S, Greysen SR. Use of smartphones and mobile devices in hospitalized patients: Untapped opportunities for inpatient engagement. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(7):459-461. PubMed

12. Coleman EA. Family caregivers as partners in care transitions: The caregiver advise record and enable act. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(12):883-885. PubMed

13. Kaziunas E, Hanauer DA, Ackerman MS, Choi SW. Identifying unmet informational needs in the inpatient setting to increase patient and caregiver engagement in the context of pediatric hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2016;23(1):94-104. PubMed

14. Woollen J, Prey J, Wilcox L, et al. Patient experiences using an inpatient personal health record. Appl Clin Inform. 2016;7(2):446-460. PubMed

15. Irizarry T, DeVito Dabbs A, Curran CR. Patient portals and patient engagement: A state of the science review. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17(6):e148. doi:10.2196/jmir.4255. PubMed

16. Vawdrey DK, Wilcox LG, Collins SA, et al. A tablet computer application for patients to participate in their hospital care. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2011;2011:1428-1435. PubMed

17. Collins SA, Rozenblum R, Leung WY, et al. Acute care patient portals: A qualitative study of stakeholder perspectives on current practices. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2016;24(e1):e9-e17. PubMed

18. Berger Z, Flickinger TE, Pfoh E, Martinez KA, Dy SM. Promoting engagement by patients and families to reduce adverse events in acute care settings: A systematic review. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;23(7):548-555. PubMed

19. Forster AJ, Murff HJ, Peterson JF, Gandhi TK, Bates DW. The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(3):161-167. PubMed

20. Griffin A, Skinner A, Thornhill J, Weinberger M. Patient Portals: Who uses them? What features do they use? And do they reduce hospital readmissions? Appl Clin Inform. 2016;7(2):489-501. PubMed

21. O’Leary KJ, Lohman ME, Culver E, Killarney A, Randy Smith G Jr, Liebovitz DM. The effect of tablet computers with a mobile patient portal application on hospitalized patients’ knowledge and activation. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2016;23(1):159-165. PubMed

22. O’Leary KJ, Sharma RK, Killarney A, et al. Patients’ and Healthcare Providers’ Perceptions of a Mobile Portal Application for Hospitalized Patients. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2016;16(1):123. PubMed

23. Pell JM, Mancuso M, Limon S, Oman K, Lin CT. Patient access to electronic health records during hospitalization. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(5):856-858. PubMed

24. Brown SM, Aboumatar HJ, Francis L, et al. Balancing digital information-sharing and patient privacy when engaging families in the intensive care unit. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2016;23(5):995-1000. PubMed

25. Krishna S, Francisco BD, Balas EA, et al. Internet-enabled interactive multimedia asthma education program: A randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2003;111(3):503-510. PubMed

26. Fox MP. A systematic review of the literature reporting on studies that examined the impact of interactive, computer-based patient education programs. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;77(1):6-13. PubMed

27. Morgan ER, Laing K, McCarthy J, McCrate F, Seal MD. Using tablet-based technology in patient education about systemic therapy options for early-stage breast cancer: A pilot study. Curr Oncol. 2015;22(5):e364-e369. PubMed

28. Nehme J, El-Khani U, Chow A, Hakky S, Ahmed AR, Purkayastha S. The use of multimedia consent programs for surgical procedures: A systematic review. Surg Innov. 2013;20(1):13-23. PubMed

29. Waller A, Forshaw K, Carey M, et al. Optimizing patient preparation and surgical experience using eHealth technology. JMIR Med Inform. 2015;3(3):e29. PubMed

30. Abbott MB, Shaw P. Virtual nursing avatars: Nurse roles and evolving concepts of care. Online J Issues Nurs. 2016;21(3):7. PubMed

31. Cawthon C, Walia S, Osborn CY, Niesner KJ, Schnipper JL, Kripalani S. Improving care transitions: The patient perspective. J Health Commun. 2012;17 Suppl 3:312-324. PubMed

32. Bickmore TW, Pfeifer LM, Byron D, et al. Usability of conversational agents by patients with inadequate health literacy: Evidence from two clinical trials. J Health Commun. 2010;15 Suppl 2:197-210. PubMed

33. 2017;376(20):1905-1907. N Engl J Med.42. Mandl KD, Kohane IS. A 21st-century health IT system—creating a real-world information economy. PubMed

34. 2014;371(19):1803-1812.N Engl J Med41. Starmer AJ, Spector ND, Srivastava R, et al. Changes in medical errors after implementation of a handoff program. PubMed

35. 2016;24(1):153-161.J Am Med Inform Assoc.40. Kelly MM, Hoonakker PLT, Dean SM. Using an inpatient portal to engage families in pediatric hospital care. PubMed

36. 2017;171(4):372-381.JAMA Pediatr.39. Khan A, Coffey M, Litterer KP, et al. Families as partners in hospital error and adverse event surveillance. PubMed

37. 2017;17(4):389-402.Acad Pediatr.38. Khan A, Baird J, Rogers JE, et al. Parent and provider experience and shared understanding after a family-centered nighttime communication intervention. PubMed

38. 2016;6(6):319-329.Hosp Pediatr. 37. Khan A, Rogers JE, Forster CS, Furtak SL, Schuster MA, Landrigan CP. Communication and shared understanding between parents and resident-physicians at night. PubMed

39. 2016;11(9):615-619.J Hosp Med36. Figueroa JF, Schnipper JL, McNally K, Stade D, Lipsitz SR, Dalal AK. How often are hospitalized patients and providers on the same page with regard to the patient’s primary recovery goal for hospitalization? PubMed

40. 2013;8(7):414-417.J Hosp Med.35. Feldman HJ, Walker J, Li J, Delbanco T. OpenNotes: Hospitalists’ challenge and opportunity. PubMed

41. 2016;11(5):381-385.J Hosp Med.34. Dalal AK, Schnipper JL. Care team identification in the electronic health record: A critical first step for patient-centered communication.PubMed

42. 2016;24(e1):e178-e184.J Am Med Inform Assoc.33. Dalal AK, Schnipper J, Massaro A, et al. A web-based and mobile patient-centered “microblog” messaging platform to improve care team communication in acute care. PubMed

1. Sarkar U, Bates DW. Care partners and online patient portals. JAMA. 2014;311(4):357-358. PubMed

2. Grando MA, Rozenblum R, Bates DW, eds. Information Technology for Patient Empowerment in Healthcare, 1st Edition. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter Inc.; 2015.

3. Kelly MM, Hoonakker PLT, Dean SM. Using an inpatient portal to engage families in pediatric hospital care. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2016;24(1):153-161. PubMed

4. Dalal AK, Dykes PC, Collins S, et al. A web-based, patient-centered toolkit to engage patients and caregivers in the acute care setting: A preliminary evaluation. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2016;23(1):80-87. PubMed

5. Prey JE, Restaino S, Vawdrey DK. Providing hospital patients with access to their medical records. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2014;2014:1884-1893. PubMed

6. Herrin J, Harris KG, Kenward K, Hines S, Joshi MS, Frosch DL. Patient and family engagement: A survey of US hospital practices. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;25(3):182-189. PubMed

7. Tom JO, Mangione-Smith R, Solomon C, Grossman DC. Integrated personal health record use: Association with parent-reported care experiences. Pediatrics. 2012;130(1):e183-e190. PubMed

8. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), HHS. Medicare and Medicaid Programs; Electronic Health Record Incentive Program-Stage 2. Federal Register Final Rule. Sect. 170; 2012. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2012/03/07/2012-4443/medicare-and-medicaid-programs-electronic-health-record-incentive-program-stage-2. Accessed March 1, 2017.

9. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), HHS. Medicare program; merit-based incentive payment system (MIPS) and alternative payment model (APM) incentive under the physician fee schedule, and criteria for physician-focused payment models. Final rule with comment period. Fed Regist. 2016;81(214):77008-77831. PubMed

10. Prey JE, Woollen J, Wilcox L, et al. Patient engagement in the inpatient setting: A systematic review. J Am Med Informat Assoc. 2014;21(4):742-750. PubMed

11. Ludwin S, Greysen SR. Use of smartphones and mobile devices in hospitalized patients: Untapped opportunities for inpatient engagement. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(7):459-461. PubMed

12. Coleman EA. Family caregivers as partners in care transitions: The caregiver advise record and enable act. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(12):883-885. PubMed

13. Kaziunas E, Hanauer DA, Ackerman MS, Choi SW. Identifying unmet informational needs in the inpatient setting to increase patient and caregiver engagement in the context of pediatric hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2016;23(1):94-104. PubMed

14. Woollen J, Prey J, Wilcox L, et al. Patient experiences using an inpatient personal health record. Appl Clin Inform. 2016;7(2):446-460. PubMed

15. Irizarry T, DeVito Dabbs A, Curran CR. Patient portals and patient engagement: A state of the science review. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17(6):e148. doi:10.2196/jmir.4255. PubMed

16. Vawdrey DK, Wilcox LG, Collins SA, et al. A tablet computer application for patients to participate in their hospital care. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2011;2011:1428-1435. PubMed

17. Collins SA, Rozenblum R, Leung WY, et al. Acute care patient portals: A qualitative study of stakeholder perspectives on current practices. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2016;24(e1):e9-e17. PubMed

18. Berger Z, Flickinger TE, Pfoh E, Martinez KA, Dy SM. Promoting engagement by patients and families to reduce adverse events in acute care settings: A systematic review. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;23(7):548-555. PubMed

19. Forster AJ, Murff HJ, Peterson JF, Gandhi TK, Bates DW. The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(3):161-167. PubMed

20. Griffin A, Skinner A, Thornhill J, Weinberger M. Patient Portals: Who uses them? What features do they use? And do they reduce hospital readmissions? Appl Clin Inform. 2016;7(2):489-501. PubMed

21. O’Leary KJ, Lohman ME, Culver E, Killarney A, Randy Smith G Jr, Liebovitz DM. The effect of tablet computers with a mobile patient portal application on hospitalized patients’ knowledge and activation. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2016;23(1):159-165. PubMed

22. O’Leary KJ, Sharma RK, Killarney A, et al. Patients’ and Healthcare Providers’ Perceptions of a Mobile Portal Application for Hospitalized Patients. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2016;16(1):123. PubMed

23. Pell JM, Mancuso M, Limon S, Oman K, Lin CT. Patient access to electronic health records during hospitalization. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(5):856-858. PubMed

24. Brown SM, Aboumatar HJ, Francis L, et al. Balancing digital information-sharing and patient privacy when engaging families in the intensive care unit. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2016;23(5):995-1000. PubMed

25. Krishna S, Francisco BD, Balas EA, et al. Internet-enabled interactive multimedia asthma education program: A randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2003;111(3):503-510. PubMed

26. Fox MP. A systematic review of the literature reporting on studies that examined the impact of interactive, computer-based patient education programs. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;77(1):6-13. PubMed

27. Morgan ER, Laing K, McCarthy J, McCrate F, Seal MD. Using tablet-based technology in patient education about systemic therapy options for early-stage breast cancer: A pilot study. Curr Oncol. 2015;22(5):e364-e369. PubMed

28. Nehme J, El-Khani U, Chow A, Hakky S, Ahmed AR, Purkayastha S. The use of multimedia consent programs for surgical procedures: A systematic review. Surg Innov. 2013;20(1):13-23. PubMed

29. Waller A, Forshaw K, Carey M, et al. Optimizing patient preparation and surgical experience using eHealth technology. JMIR Med Inform. 2015;3(3):e29. PubMed

30. Abbott MB, Shaw P. Virtual nursing avatars: Nurse roles and evolving concepts of care. Online J Issues Nurs. 2016;21(3):7. PubMed

31. Cawthon C, Walia S, Osborn CY, Niesner KJ, Schnipper JL, Kripalani S. Improving care transitions: The patient perspective. J Health Commun. 2012;17 Suppl 3:312-324. PubMed

32. Bickmore TW, Pfeifer LM, Byron D, et al. Usability of conversational agents by patients with inadequate health literacy: Evidence from two clinical trials. J Health Commun. 2010;15 Suppl 2:197-210. PubMed

33. 2017;376(20):1905-1907. N Engl J Med.42. Mandl KD, Kohane IS. A 21st-century health IT system—creating a real-world information economy. PubMed

34. 2014;371(19):1803-1812.N Engl J Med41. Starmer AJ, Spector ND, Srivastava R, et al. Changes in medical errors after implementation of a handoff program. PubMed

35. 2016;24(1):153-161.J Am Med Inform Assoc.40. Kelly MM, Hoonakker PLT, Dean SM. Using an inpatient portal to engage families in pediatric hospital care. PubMed

36. 2017;171(4):372-381.JAMA Pediatr.39. Khan A, Coffey M, Litterer KP, et al. Families as partners in hospital error and adverse event surveillance. PubMed

37. 2017;17(4):389-402.Acad Pediatr.38. Khan A, Baird J, Rogers JE, et al. Parent and provider experience and shared understanding after a family-centered nighttime communication intervention. PubMed

38. 2016;6(6):319-329.Hosp Pediatr. 37. Khan A, Rogers JE, Forster CS, Furtak SL, Schuster MA, Landrigan CP. Communication and shared understanding between parents and resident-physicians at night. PubMed

39. 2016;11(9):615-619.J Hosp Med36. Figueroa JF, Schnipper JL, McNally K, Stade D, Lipsitz SR, Dalal AK. How often are hospitalized patients and providers on the same page with regard to the patient’s primary recovery goal for hospitalization? PubMed

40. 2013;8(7):414-417.J Hosp Med.35. Feldman HJ, Walker J, Li J, Delbanco T. OpenNotes: Hospitalists’ challenge and opportunity. PubMed

41. 2016;11(5):381-385.J Hosp Med.34. Dalal AK, Schnipper JL. Care team identification in the electronic health record: A critical first step for patient-centered communication.PubMed

42. 2016;24(e1):e178-e184.J Am Med Inform Assoc.33. Dalal AK, Schnipper J, Massaro A, et al. A web-based and mobile patient-centered “microblog” messaging platform to improve care team communication in acute care. PubMed

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

Electronic Communication

INTRODUCTION

Coordination of care within a practice, during transitions of care, and between primary and specialty care teams requires more than data exchange; it requires effective communication among healthcare providers.[1, 2, 3] In clinical terms, data exchange, communication, and care coordination are related, but they represent distinct concepts.[4] Data exchange refers to transfer of information between settings, independent of the individuals involved, whereas communication is the multistep process that enables information exchange between two people.[5] Care coordination, as defined by O'Malley, is integration of care in consultation with patients, their families and caregivers across all of a patient's conditions, needs, clinicians and settings.[3]

Strong collaboration among providers has been associated with improved patient outcomes.[2, 6] Yet, despite the significant role of communication in healthcare, communication may not take place at all, even at high‐stakes events like transitions of care,[7, 8] or it may be done poorly at the risk of substantial clinical morbidity and mortality.[9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16]

Proof of the global effectiveness of health information technology (HIT) to improve patient care is lacking, but data from some studies demonstrate real improvements in quality and safety in specific areas,[17, 18, 19] especially with computerized physician order entry[20] and electronic prescribing.[21]

The limited information about the effect of HIT on communication focuses largely on the anticipated improvements in patient‐physician communication[22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27]; provider‐to‐provider communication within the electronic domain is not as well understood. A recent review of interventions involving communication devices such as pagers and mobile phones found limited high‐quality evidence in the literature.[28] Clinicians have described what they consider to be key characteristics of clinical electronic communications systems such as security/reliability, cross coverage, overall convenience, and message prioritization.[29] Although the electronic health record (EHR) is expected to assist with this communication,[30] it also has the potential to impede effective communication, leading physicians to resort to more traditional workarounds.[31, 32, 33]

Measuring and improving the use of EHRs nationally were driving forces behind the creation of the Meaningful Use incentive program in the United States.[34] To receive the incentive payments, providers must meet and report on a series of measures set in three stages over the course of five years.[35] In the current state, Meaningful Use does not reward provider‐to‐provider communication within the EHR.[36, 37] The main communication objectives for stages 1 and 2 concentrate on patient‐to‐provider communication, such as patient portals and patient‐to‐provider messaging.[36, 37]

Understanding the current evidence for provider‐to‐provider communication within EHRs, its reported effectiveness, and its shortcomings may help to develop a roadmap for identifying next‐generation solutions to support coordination of care.[38, 39] This review assesses the literature regarding provider‐to‐provider electronic communication tools (as supported within or external to an EHR). It is intended as a comprehensive view of studies reporting quantitative measures of the impact of electronic communication on providers and patients.

METHODS

Definitions and Conceptual Model of Provider‐to‐Provider Communication

We conducted a systematic review of studies of provider‐to‐provider electronic communication. This review included only formal clinical communication between providers and was informed by the Coiera communications paradigm.[5] This paradigm consists of four steps: (1) task identification, when a task is identified and associated with the appropriate individual; (2) connection, when an attempt is made to contact that person; (3) communication, when task‐specific information is exchanged between the parties; and (4) disconnection, when the task reaches some stage of completion.

Literature Review

We examined written electronic communication between providers including e‐mail, text messaging, and instant messaging. We did not review provider‐to‐provider telephone or telehealth communication, as these are not generally supported within EHR systems. Communication in all clinical contexts was included among providers within an individual clinic or hospital and among providers across specialties or practice settings.[40] We excluded physician handoff communication because it has been extensively reviewed elsewhere and because handoff occurs largely through verbal exchange not recorded in the EHR.[41, 42] Communication from clinical information systems to providers, such as automated notification of unacknowledged orders, was also excluded, as it is not within the scope of provider‐to‐provider interaction.

Data Sources and Searches

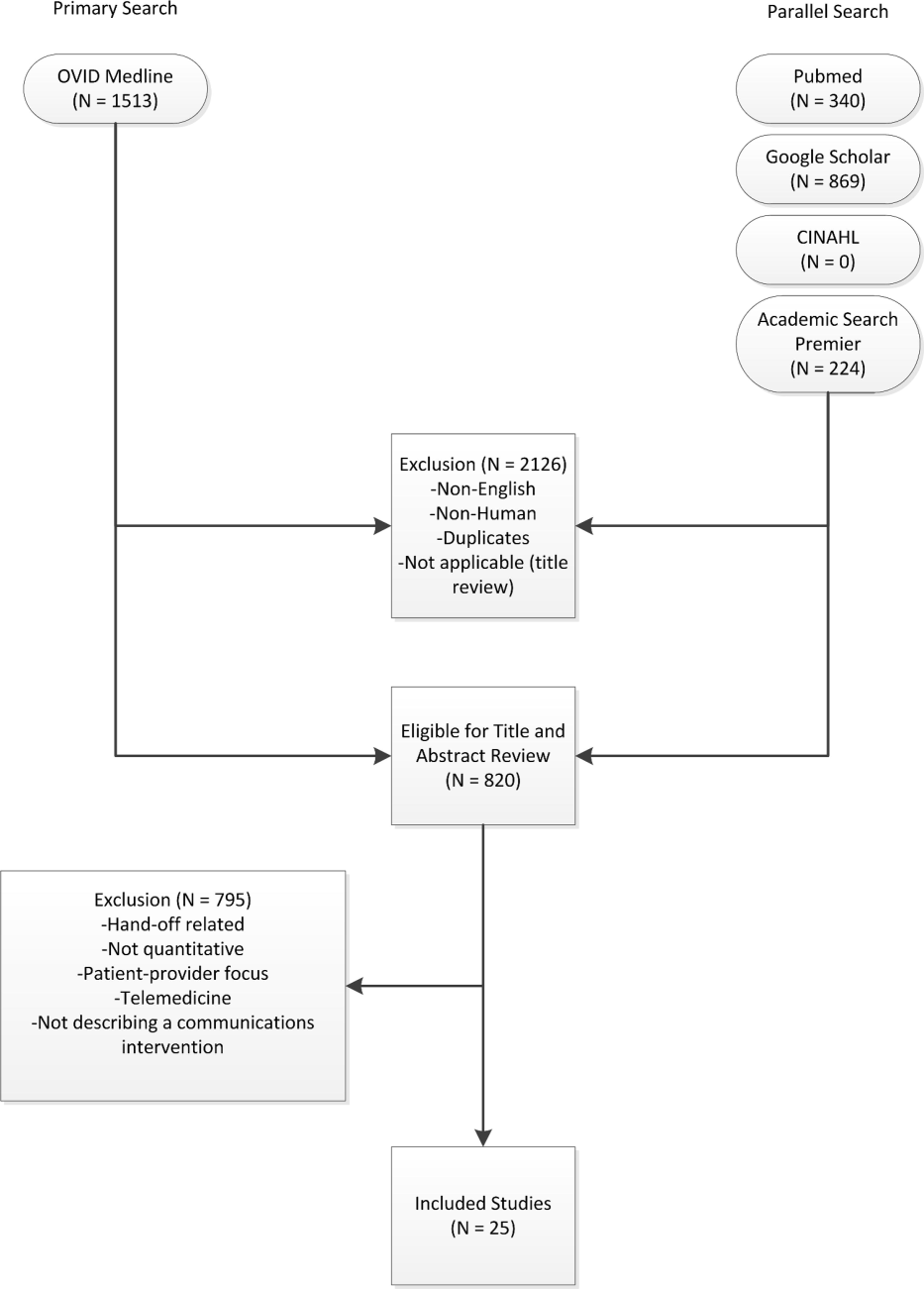

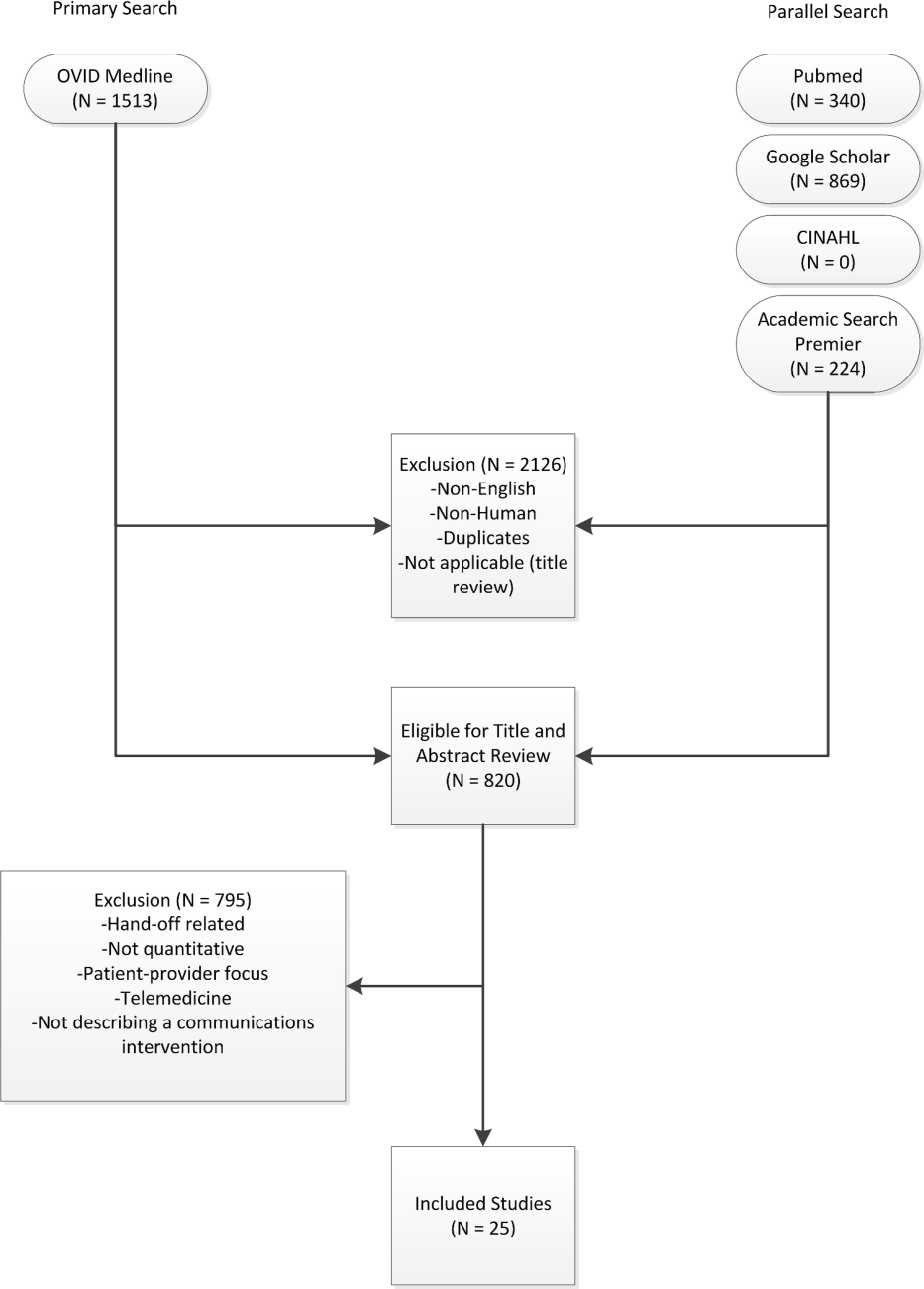

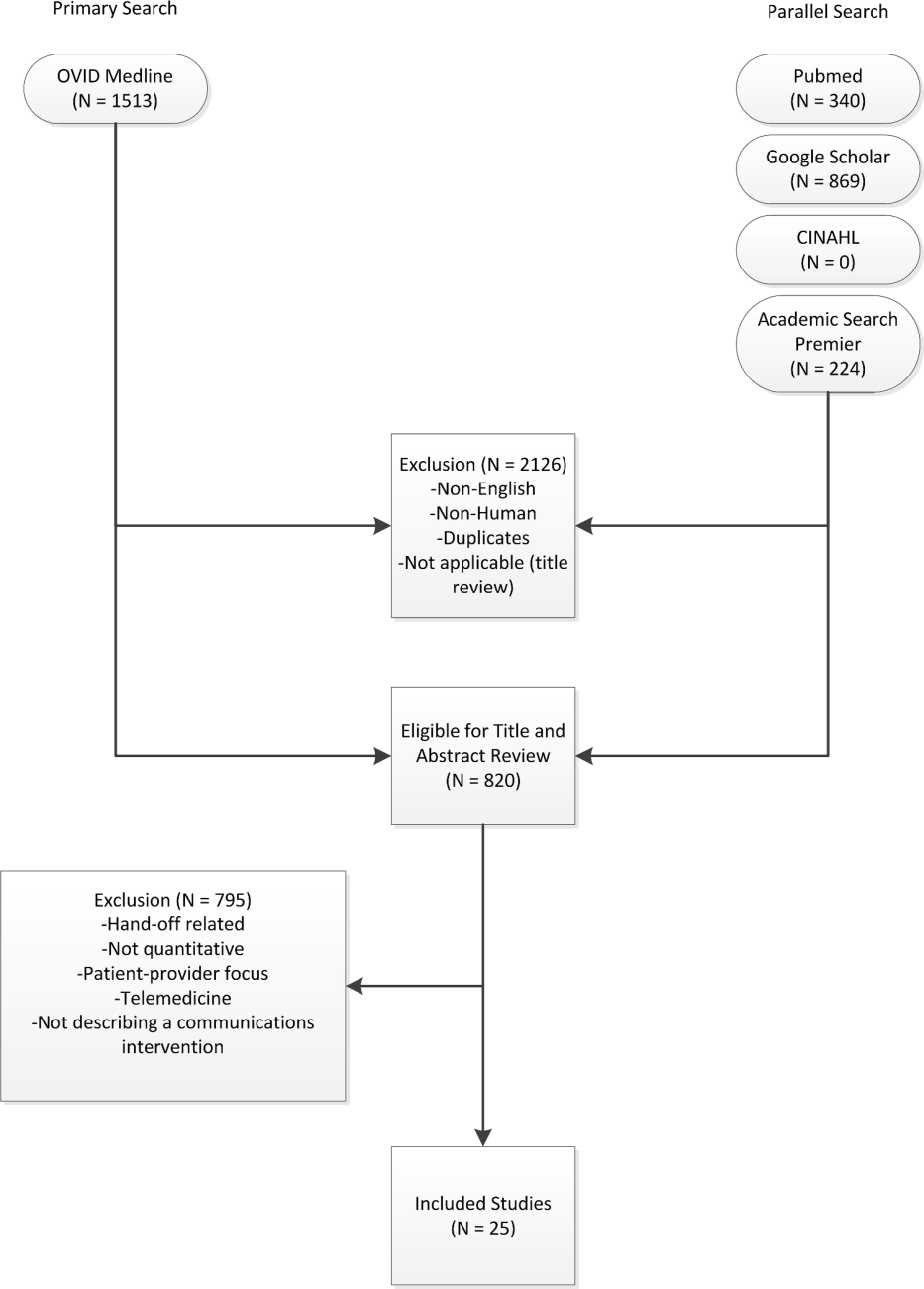

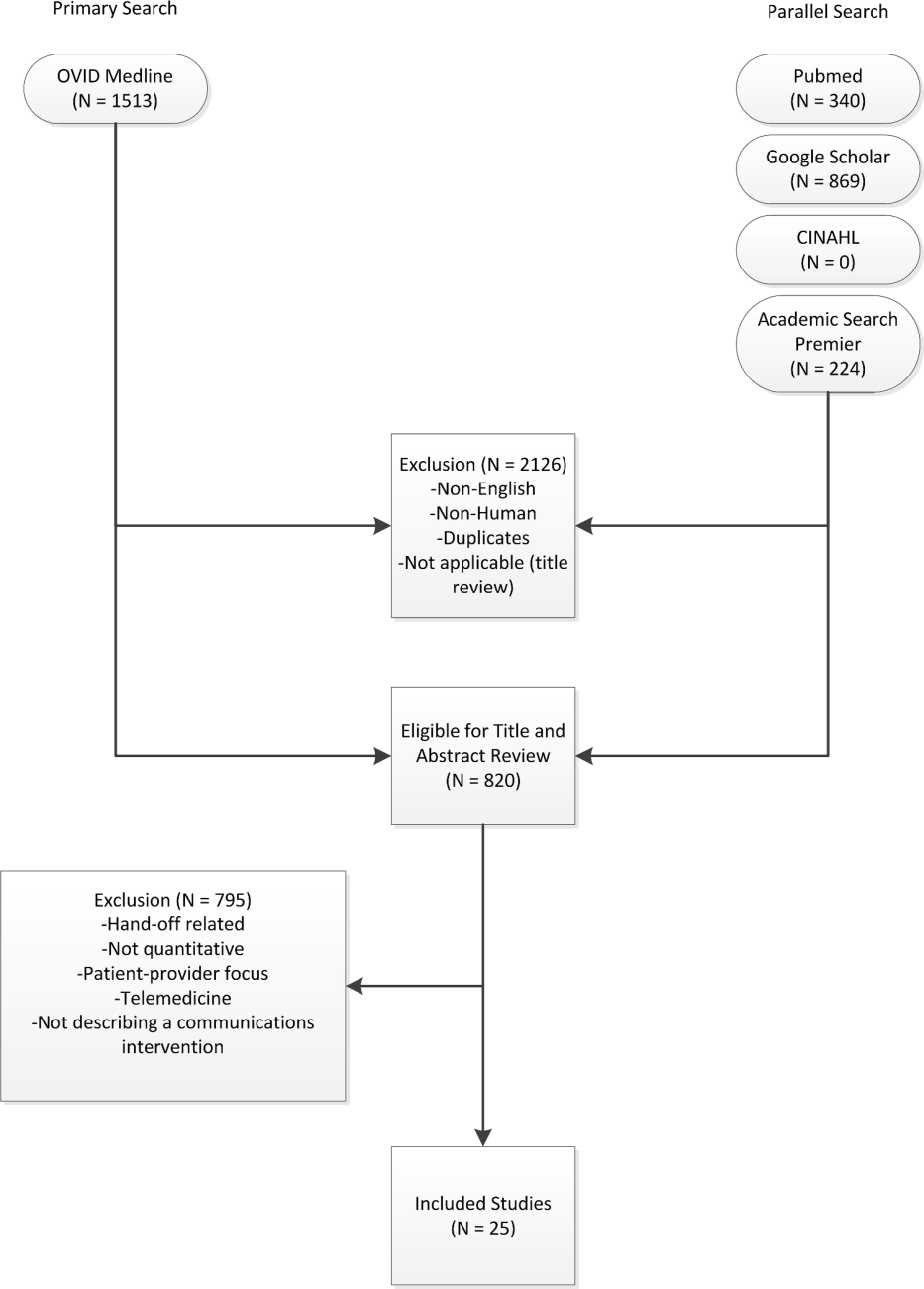

A comprehensive literature search was conducted in Ovid MEDLINE with the input of a medical librarian, and a parallel search was performed using PubMed. The Ovid MEDLINE query and parallel database search terms are documented in Table 1. Subsearches were conducted in Google Scholar, the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), and Academic Search Premier for peer‐reviewed journals. Subsequent studies citing the initially detected articles were found through citation maps.

| Database | Strategy | Items Reviewed |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Ovid MEDLINE | Query terms: exp medicine/ or physicians or exp outpatient clinics/ or exp hospitals/ AND *communication/ or *computer communication networks/ or *interprofessional relations/ or *continuity of patient care/ AND electronic mail or referral and consultation or text messaging/ or reminder systems. | 1513 |

| PubMed | Healthcare, provider, communication, messaging, e‐mail, texting, text messaging, instant messaging, paging, coordination, referral, EHR, EMR, electronic health record, electronic medical record, electronic, and physician. Excluding patient‐provider and patient‐physician | 340 |

| Google Scholar | Physician‐physician electronic communication excluding physician‐patient | 940 |

| CINAHL | Medical records and communication; or computerized patient records and communication | None |

| Academic Search Premier (peer‐reviewed journals) | Electronic health record and communication | 54 |

| Communication and electronic health record | 80 | |

| Physician‐physician communication | 2 | |

| Physicians and electronic health records | 88 | |

Study Selection

Paper Inclusion Criteria

Requirements included publication in English‐language peer‐reviewed journals. Included studies provided quantitative provider‐to‐provider communication data, provider satisfaction statistics, or EHR communication data. Provider‐to‐staff communication was also included if it fell within the scope of studies of communication between providers.

Paper Exclusion Criteria

Studies excluded in this review were articles that reviewed EHR systems without any focus on communication between providers and those that discussed EHR models and strategies but did not include actual testing and quantitative results. Results that included nontraditional online documents or that were found on nonpeer‐reviewed websites were also discarded. Duplicate records or publications that covered the same study were also removed. The most common reason for exclusion was the lack of quantitative evaluation.

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Three authors (Walsh, Siegler, Stetson) reviewed titles and abstracts of resultant studies against inclusion and exclusion criteria (Figure 1). Studies were evaluated qualitatively and findings summarized. Given the heterogeneous nature of data reported, statistical analysis was not possible.

RESULTS

The primary and parallel searches produced 2946 results that were weaned through title review and exclusion of duplicates, nonEnglish‐language, and nonhuman studies to 820 articles for title and abstract review (Figure 1). After careful review of the articles' titles, abstracts, or full content (where appropriate), twenty‐five articles met inclusion criteria and presented data about provider‐to‐provider electronic communication, either within an EHR or through a system designed to promote provider‐to‐provider communication. All of the studies that met inclusion criteria focused on physicians as providers. Five studies (20%) described trial design, three (12%) were pilot studies, and seventeen (68%) were observational studies. Thirteen of twenty‐five articles (52%) described studies conducted in the United States and twelve in Europe.

Most of the studies (56%) focused on electronic referrals between primary care and subspecialty providers. The clinical need was to communicate information on a specific patient with a specialist who shared responsibility for the overall plan of care. Only two studies evaluated curbside consultation, where providers ask for clinical recommendations without formally engaging a specialist in the plan of care for a particular patient. Table 2 summarizes included studies and has been organized with respect to clinical need under evaluation. The major themes that emerged from this review included: studies of penetration of communication tools either within the EHR system (intra‐EHR IT) or external to the EHR (extra‐EHR IT); electronic referrals; curbside consultations; and test results reporting (results notification).

| Primary Author, Year | Design | Intervention | Measurement | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Need: Communicate care across clinical settings (inpatient‐outpatient) | ||||

| Branger, 1992[4, 6] | Observational study | Introduction of electronic messaging system in the Netherlands between hospital and PCPs. | Satisfaction survey data using Likert scale of usefulness. | Free text messaging to exchange patient data was rated very useful or useful by 20 of 27 PCP respondents. |

| Reponen, 2004[66] | Observational study | Finnish study of electronic referrals XML messages between EHRs or secure web links. | User questionnaire. No description of respondents was provided. | Internists surveyed estimated that electronic referrals accelerate the referral process by 1 week. |

| Need: Communicate care across specialties (primary care physicians‐specialists) | ||||

| Kooijman, 1998[67] | Observational study | Survey of 45 PCPs who received notes from specialists via Electronic Data Interchange. | User questionnaire with 5‐point Likert scale of satisfaction, from 1 (much better) to 5 (much worse). | Highest satisfaction scores for speed (1.51.8) and efficiency (1.51.7) for electronic messages, with lower scores for reliability (2.52.7) and clarity (2.5). |

| Harno, 2000[4][8] | Nonrandomized trial | Eight‐month prospective comparative study in Finland of outpatient clinics in hospitals with and without intranet referral systems. | Comparison of numbers of electronic referrals, clinic visits, costs. | There were 43% of electronic referrals and 79% of outpatient referrals that resulted in outpatient visits. A 3‐fold increase in productivity overall and 7‐fold reduction in visit costs per patient using e‐mail consultation. |

| Moorman, 2001[4][7] | Observational study | Supersedes Branger, 1999.[68] Analyzes intra‐EHR communications between PCPs and consultant in Netherlands re: diabetes management of patients (19941998). | Descriptive statistics of number of messages, content, whether message had been copied into EMR; survey of PCPs (12 of 15 responded). | Decline in integration by PCPs of messages in the EHR from 75% to 51% over first 3 years. Despite this, most PCPs wanted to extend messaging to other patient groups. |

| Bergus, 2006[69] | Observational study | Follow‐up of Bergus, 1998[54]; evaluated formulation of clinical referrals to specialists at the University of Iowa by retrospective review of e‐mail transcripts. | Analyzed taxonomy of clinical questions; assessed need for clinical consultation of 1618 clinical questions. | Specialists less likely to recommend clinic consultation if referral specified the clinical task (OR: 0.36, P<0.001), intervention (OR: 0.62, P=0.004), or outcome (OR: 0.49, P<0.001). This effect was independent of clinical content (P>0.05). |

| Dennison, 2006[70] | Pilot study | Construction of an electronic referral pro forma to facilitate referral of patients to colorectal surgeons. | Descriptive statistics. Comparisons of patient attendance rate, delays to booking and to actual appointment between 54 electronic referrals and 189 paper referrals. | Compared to paper referrals, electronic referrals were booked more quickly (same day vs 1 week later on average) and patients had lower nonattendance rates (8.5% vs 22.5%). Both results stated as statistically significant, but P values were not provided. |

| Shaw, 2007[49] | Observational study | Dermatology electronic referral in England. | Content of 131 electronic vs 139 paper referrals to dermatologists(NHS Choose and Book).[71] | Paper superior to electronic for clinical data such as current treatments (included in 68% of paper vs 39% of electronic referrals, P<0.001); electronic superior for demographic data. |

| Gandhi, 2008[50] | Nonrandomized trial | Electronic referral tool in the Partners Healthcare System in Massachusetts that included a structured referral‐letter generator and referral status tracker. Assigned to 1 intervention site and 1 control site. | Survey assessment. Fifty‐four of 117 PCPs responded (46%), 235 of 430 specialists responded (55%), 143 out of 210 patients responded (69%). | Intervention group showed high voluntary adoption (99%), higher information transfer rates prior to subspecialty visit (62% vs 12%), and lower rates of conflicting information being given to patients (6% vs 20%). |

| John, 2008[72] | Pilot study | Validation study of the Lower Gastrointestinal e‐RP (through the Choose and Book System in the United Kingdom) intended to improve yield of colon cancers diagnosed and to reduce delays in diagnosis. | Comparison of actual to simulated referral patterns through e‐RP for 300 patients divided into colorectal cancer, 2‐week wait suspected cancer, and routine referral groups. | e‐RP was more accurate than traditional referral at upgrading patients who had cancer to the appropriate suspected cancer referral group (85% vs 43%, P=0.002). |

| Kim, 2009[73] | Observational study | Electronic referrals via a portal to San Francisco General Hospital. Included reply functionality and ability to forward messaging to a scheduler for calendaring. | Impact of electronic referral system as measured by questionnaire to referring providers. A total of 298/368 participated (24 clinics); 53.5% attending physicians. | Electronic referrals improved overall quality of care (reported by 72%), guidance of presubspecialty visit (73%), and the ability to track referrals (89%). Small change in access for urgent issues (35% better, 49% reported no change). |

| Scott, 2009[74] | Pilot study | Pilot of urgent electronic referral system from PCPs to oncologists at South West Wales Cancer Centre. | Satisfaction statistics (10‐point Likert scale) collected from PCPs via interview. | Over 6 months, 99 referrals submitted; 81% were processed within 1 hour with high satisfaction scores. |

| Were, 2009[75] | Nonrandomized trial | Geriatrics consultants were provided system to make electronic recommendations (consultant‐recommended orders) in the native CPOE system along with consult notes in the intervention vs consult notes alone in the control. | Rates of implementation of consultant recommendations. Qualitative survey of users of the new system. | Higher total number of recommendations (247 vs 192, P<0.05) and higher implementation rates of consultant‐recommended orders in the intervention group vs control (78% vs 59%, P=0.01). High satisfaction scores on 5‐point Likert scale for the intervention system with good survey response rate (83%). |