User login

Breastfeeding by patients with serious mental illness: An ethical approach

Difficult ethical situations can arise when treating perinatal women who have serious mental illness (SMI). Clinicians must consider ethical issues related to administering antipsychotic medications, the safety of breastfeeding, and concerns for child welfare. They need to carefully weigh the risks and benefits of each decision when treating perinatal women who have SMI. Ethical guidelines can help clinicians best support families in these situations.

In this article, we describe 2 cases of women with psychotic disorders who requested to breastfeed after delivering their child during an inpatient psychiatric hospitalization. The course of their hospitalizations illustrated common ethical questions and facilitated the creation of a framework to assist with complex decision-making regarding breastfeeding on inpatient psychiatric units.

CASE 1

Ms. C, age 41, is multigravida with a psychiatric history of chronic, severe schizoaffective disorder and lives in supportive housing. When Ms. C presents to the hospital in search of a rape kit, clinicians discover she is 22 weeks pregnant but has not received any prenatal care. Psychiatry is consulted because she is found to be intermittently agitated and endorses grandiose delusions. Ms. C requires involuntary hospitalization for decompensated psychosis because she refuses prenatal and psychiatric care. Because it has reassuring reproductive safety data,1 olanzapine 5 mg/d is started. However, Ms. C experiences minimal improvement from a maximum dose of 20 mg/d. After 13 weeks on the psychiatry unit, she is transferred to obstetrics service for preeclampsia with severe features. Ms. C requires an urgent cesarean delivery at 37 weeks. Her baby boy is transferred to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) for transient tachypnea. After delivery and in consultation with psychiatry, the pediatrics team calls Child Protective Services (CPS) due to concern for neglect driven by Ms. C’s psychiatric condition. Ms. C visits the child with medical unit staff supervision in the NICU without consulting with the psychiatry service or CPS. On postpartum Day 2, Ms. C is transferred back to psychiatry for persistent psychosis.

On postpartum Day 3, Ms. C starts to produce breastmilk and requests to breastfeed. At this time, the multidisciplinary team determines she is not able to visit her child in the NICU due to psychiatric instability. No plan is developed to facilitate hand expression or pumping of breastmilk while Ms. C is on the psychiatric unit. The clinical teams discuss whether the benefits of breastfeeding and/or pumping breastmilk would outweigh the risks. CPS determines that Ms. C is unable to retain custody and places the child in kinship foster care while awaiting clinical improvement from her.

CASE 2

Ms. S, age 32, has a history of schizophrenia. She lives with her husband and parents. She is pregnant for the first time and has been receiving consistent prenatal care. Ms. S is brought to the hospital by her husband for bizarre behavior and paranoia after self-discontinuing risperidone 2 mg twice daily due to concern about the medication’s influence on her pregnancy. An ultrasound confirms she is 37 weeks pregnant. Psychiatry is consulted because Ms. S is internally preoccupied, delusional, and endorses auditory hallucinations. She requires involuntary hospitalization for decompensated psychosis. During admission, Ms. S experiences improvement of her psychiatric symptoms while receiving risperidone 2 mg twice daily, which she takes consistently after receiving extensive psychoeducation regarding its safety profile during pregnancy and lactation.

After 2 weeks on the psychiatry unit, Ms. S’s care team transfers her to the obstetrics service with one-to-one supervision. At 39 weeks gestation, she has a vaginal delivery without complications. Because there are no concerns about infant harm, obstetrics, pediatrics, and psychiatry coordinate care so the baby can room in with Ms. S, her husband, and a staff supervisor to facilitate bonding. Ms. S starts to lactate, wishes to breastfeed, and meets with lactation, pediatric, obstetric, and psychiatric specialists to discuss the risks and benefits of breastfeeding and pumping breastmilk. She pursues direct breastfeeding until the baby is discharged home with the husband at postpartum Day 2. CPS is not called because there are no concerns for parental abuse or neglect at the infant’s discharge.

On postpartum Day 2, the obstetrics service transfers Ms. S back to the psychiatric unit for further treatment of her paranoia. She wishes to pump breastmilk while hospitalized, so the treatment team supplies a breast pump, facilitates the storage of breastmilk, and coordinates supervision during pumping to reduce the ligature risk. Ms. S’s husband visits daily to transport the milk and feed the infant breastmilk and formula to meet its nutritional needs. Ms. S maintains psychiatric stability while breast pumping, and the team helps transition her to breastfeeding during visitation with her husband and infant until she is discharged home at 2 weeks postpartum.

Continue to: Approaching care with a relational ethics framework

Approaching care with a relational ethics framework

A relational ethics framework was constructed to evaluate whether to support breastfeeding for both patients during their psychiatric hospitalizations. A relational ethics perspective is defined as “a moral responsibility within a context of human relations” [that] “recognizes the human interdependency and reciprocity within which personal autonomy is embedded.”2 This framework values connectedness and commonality between various and even conflicting parties. In the setting of a clinician-patient relationship, health care decisions are made with consideration of the patient’s traditional beliefs, values, and principles rather than the application of impartial moral principles. For these complex cases, this framework was chosen to determine the safest possible outcome for both mother and child.

Risks/benefits of breastfeeding by patients who have SMI

There are several methods of breastfeeding, including direct breastfeeding and other ways of expressing breastmilk such as pumping or hand expression.3 Unlike other forms of feeding using breastmilk, direct breastfeeding has been extensively studied, has well-established medical and psychological benefits for newborns and mothers, and enhances long-term bonding.4 Compared with their counterparts who do not breastfeed, mothers who breastfeed have lower rates of unintended pregnancy, cardiovascular disease, postpartum bleeding, osteoporosis, and breast and ovarian cancer.5 Among its key psychological benefits, breastfeeding is associated with an increase in maternal self-efficacy and, in some research, has been shown to be associated with a decreased risk of postpartum depression and stress.Additionally, breastfed infants experience lower rates of childhood infection and obesity, and improved nutrition, cognitive development, and immune function.6 The American Academy of Pediatrics recognizes these benefits and recommends that women exclusively breastfeed for 6 months postpartum and continue to breastfeed for 2 years or beyond if mutually desired by the mother and child.7 Absolute contraindications to breastfeeding must be ruled out (eg, infant classic galactosemia; maternal use of illicit substances such as cocaine, opioids, or phencyclidine; maternal HIV infection, etc).

The risks of breastfeeding by patients who have SMI must also be considered. In severe situations, the infant can be exposed to a mother’s agitation secondary to psychosis.8,9 The transmission of antipsychotic medication through breastmilk and associated adverse effects (eg, sedation, poor feeding, and extrapyramidal symptoms) are also potential risks and varies among different antipsychotic medications.1,10 Therefore, when prescribing an antipsychotic for a patient with SMI who breastfeeds, it is crucial to consider the medication’s safety profile as well as other factors, such as the relative infant dose (the weight-adjusted [ie, mg/kg] percentage of the maternal dosage ingested by a fully breastfed infant) and the molecular characteristics of the medication.10-12 Neonates should be routinely monitored for adverse effects, medication toxicity, and withdrawal symptoms, and care should be coordinated with the infant’s pediatrician. Certain antipsychotic medications, such as aripiprazole, may impact breastmilk production through the dopamine agonist’s interference of the prolactin reflex and anticholinergic properties.11,13 For a patient with SMI, perhaps the most significant risk involves the time and resources needed for breastfeeding, which can interfere with sleep and psychiatric treatment and possibly further exacerbate psychiatric symptoms.14-16 Additionally, breastfeeding difficulties or disruption can increase the risk of psychiatric symptoms and psychological distress.17 In Ms. C’s case, there was a delay in the baby latching as well as multiple medical and psychiatric factors that hindered the milk-ejection reflex to properly initiate; both of these factors rendered breastfeeding particularly difficult while Ms. C was on the inpatient psychiatry unit.17 In comparison, Ms. S was able to bond with her infant shortly after delivery, which facilitated the milk-ejection reflex and lactation.

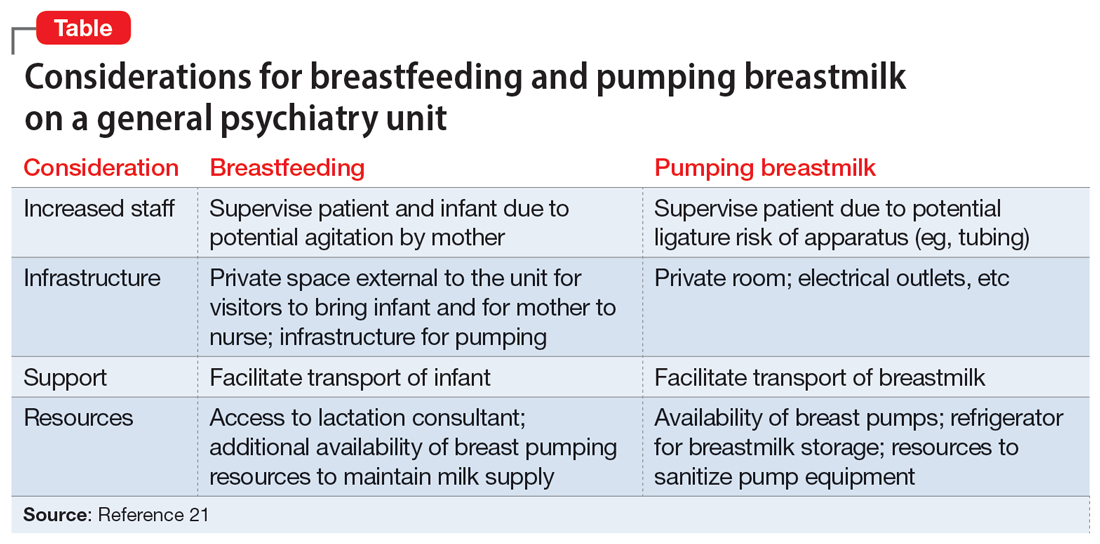

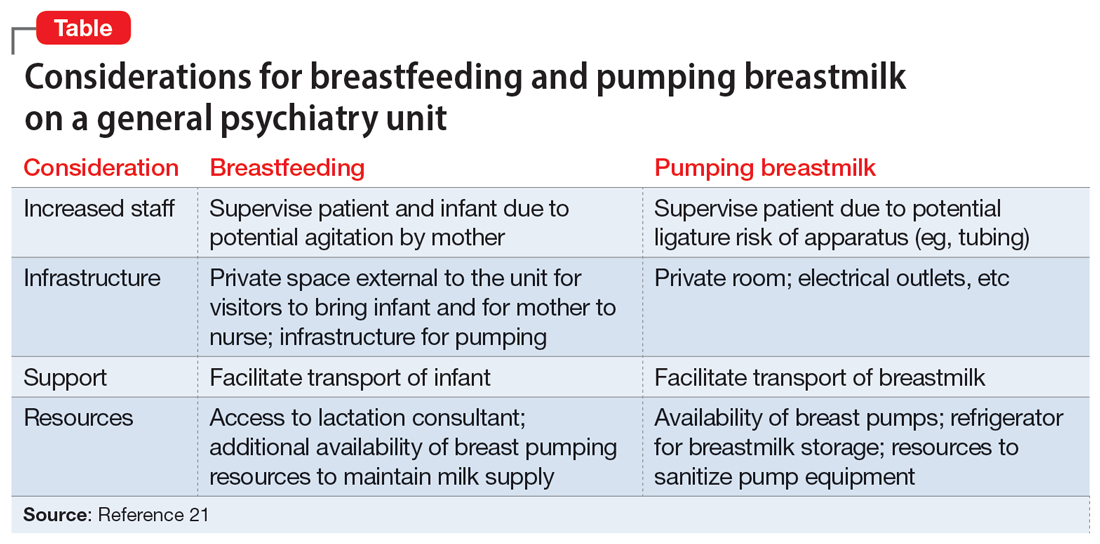

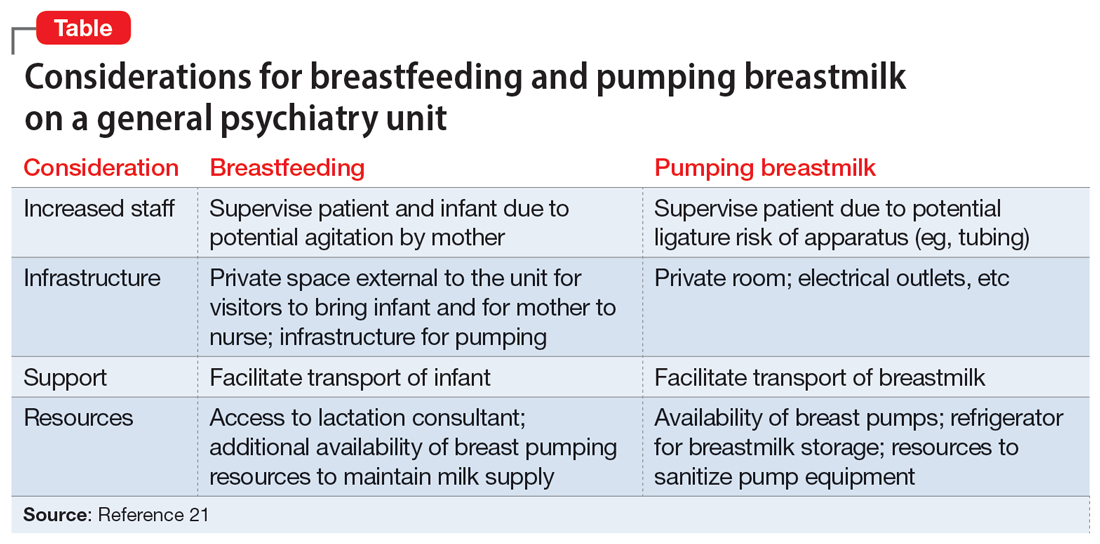

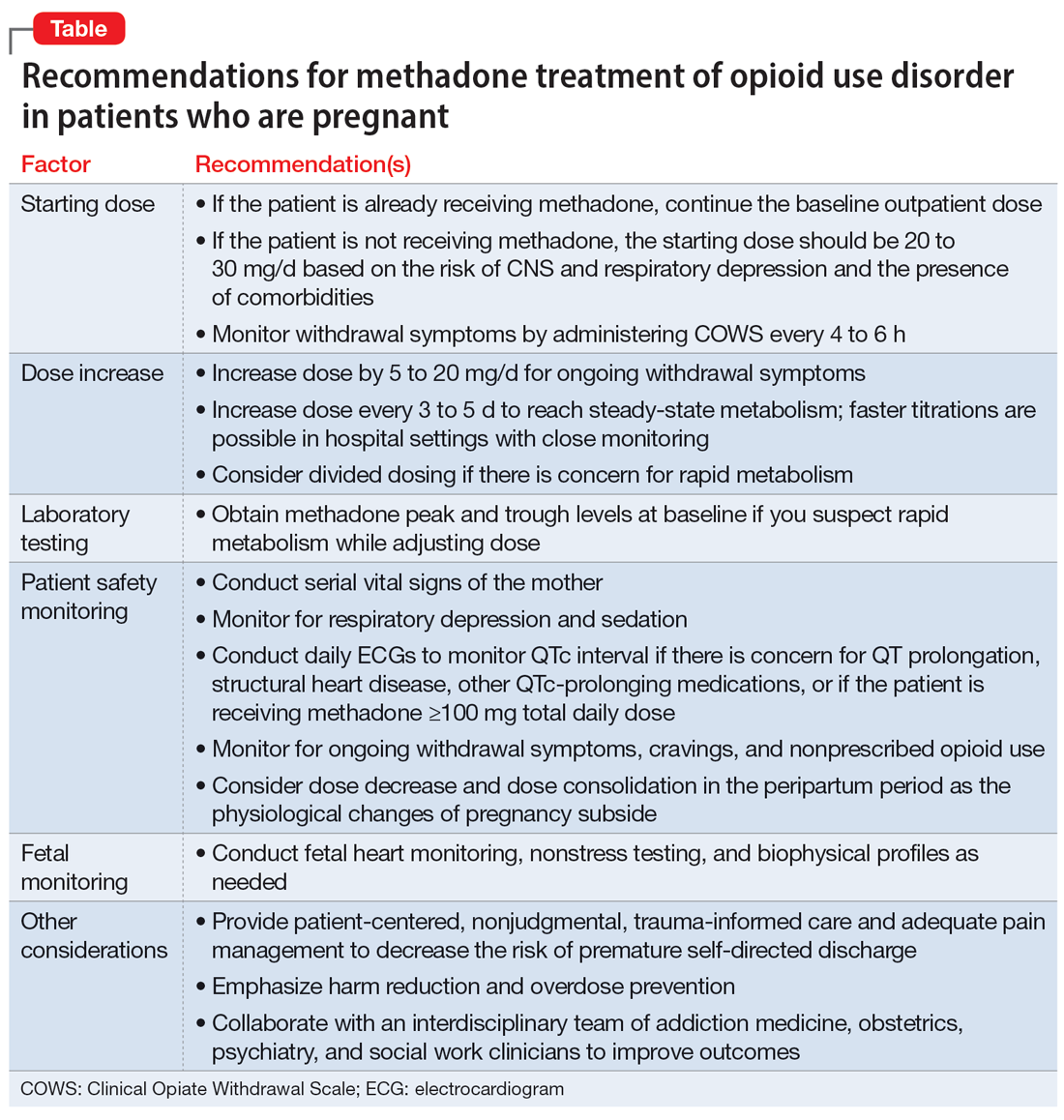

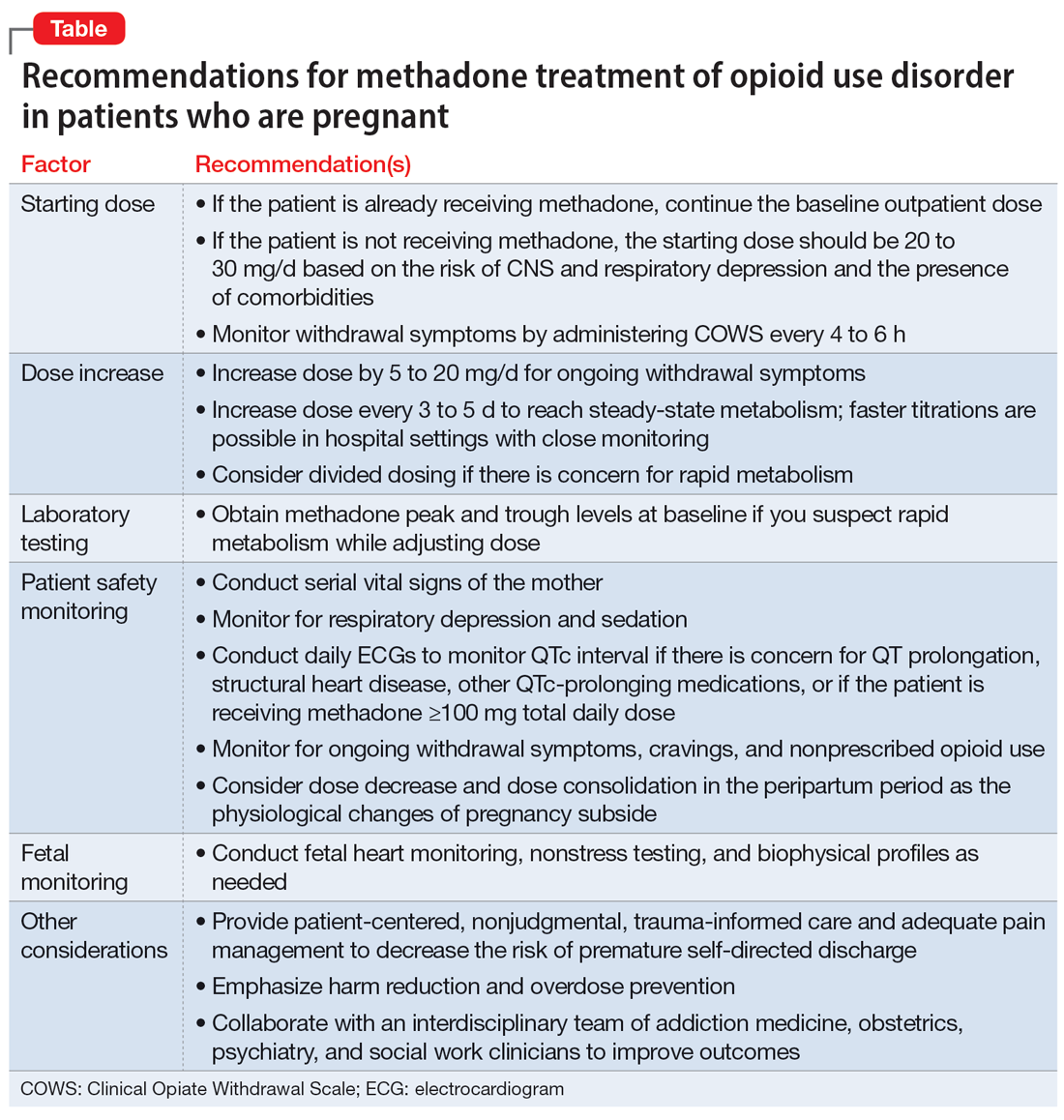

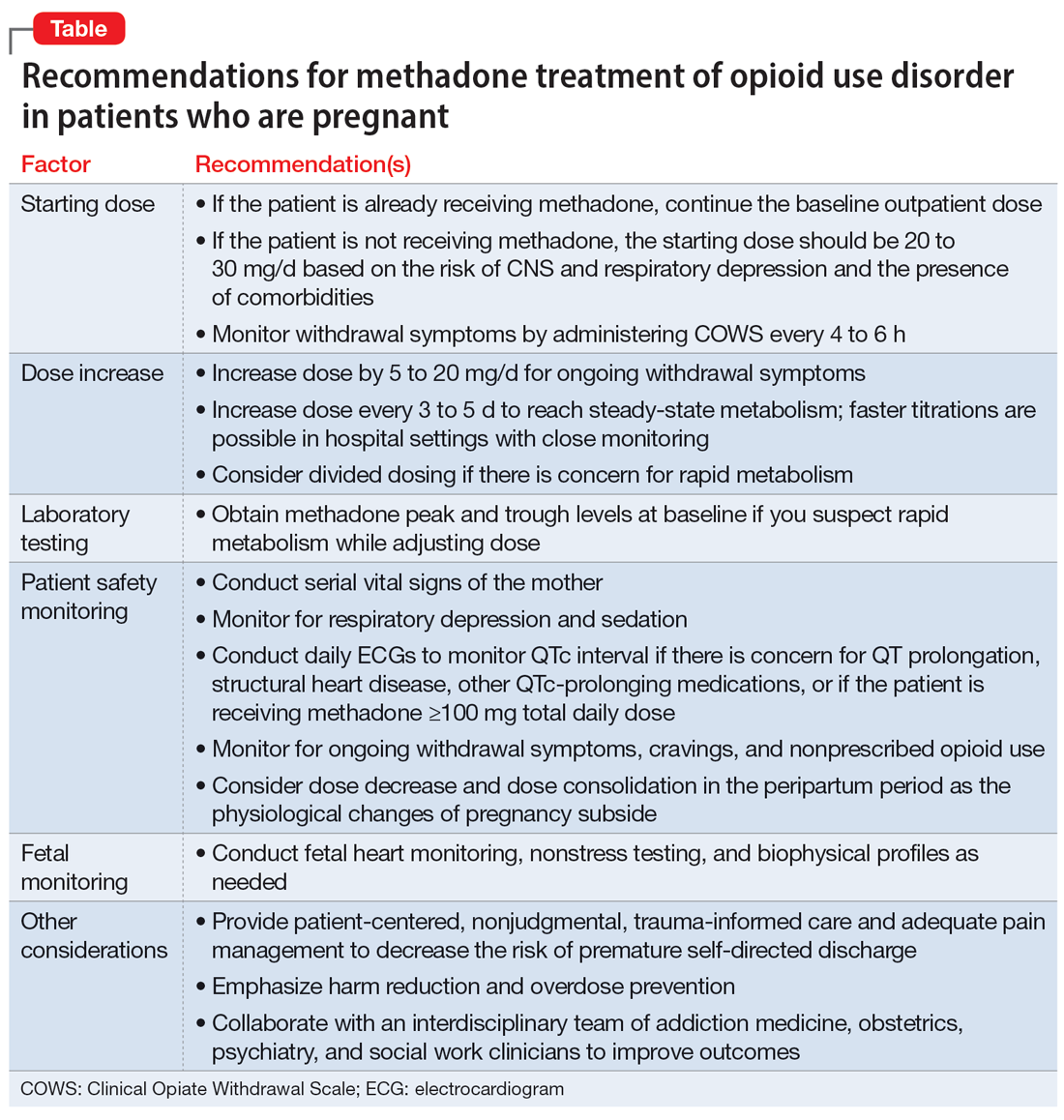

Patients who wish to directly breastfeed but struggle to do so while tending to their acute psychiatric condition can benefit from expression of breastmilk that can be provided to the infant or discarded to facilitate breastfeeding in the future.18 While expression of breastmilk may not be as advantageous for infant health as direct breastfeeding due to the potential changes in breastmilk composition from collecting, storing, and heating, this option can be more protective than formula feeding and facilitate future breastfeeding.19 In these clinical scenarios, it is standard care to provide a hospital-grade breast pump to the patient, much like a continuous positive airway pressure machine is provided to patients with obstructive sleep apnea.20 However, there is often considerable difficulty obtaining proper breastfeeding equipment and a lack of services devoted to perinatal care in general inpatient settings. Barriers to direct breastfeeding and pumping of breastmilk are highlighted in the Table.21

Limitations on breastfeeding on an inpatient unit

The limitations in care and restrictions placed on breastfeeding are more optimally addressed in a mother and baby unit (MBU). MBUs are specialized inpatient psychiatric units designed for mothers experiencing severe perinatal psychiatric difficulties. Unlike general psychiatric units, MBUs allow for joint, full-time admission of mothers and their infants. These units also include multidisciplinary staff who specialize in treating perinatal mental health issues as well as infant care and child development.22 Admission into an MBU is considered best practice for new mothers requiring treatment, particularly in the United Kingdom, Australia, and France, as it is well-recognized that the separation of mother and baby can be psychologically harmful.23 In the UK, most patients admitted to an MBU showed significant improvement of their psychiatric symptoms and reported overall high satisfaction with care.24,25 Patients who experience postpartum psychosis prefer MBUs over general psychiatric units because the latter often lack specialized perinatal support, appropriate visitor arrangements, and adequate time with their infant.26-28

Continue to: The resistance to adopting MBUs in the United States...

The resistance to adopting MBUs in the United States has posed significant barriers in care for perinatal patients and has been attributed to financial barriers, medicolegal risk, staffing, and safety concerns.29 Though currently there are no MBUs in the US, other specialized units have been created. A partial day hospitalization program created in 2000 in Rhode Island for mothers and infants revolutionized the psychiatric care experience for new mothers.30 Since then, other institutions have significantly expanded their services to include perinatal psychiatry inpatient units, yet unlike MBUs, these units typically do not provide overnight rooming-in with infants.31 They have the necessary resources and facilities to accommodate the mother’s needs and maximize positive mother-infant interaction, while actively integrating the infant into the mother’s treatment. Breast pumping is treated as a necessary medical procedure and patients can easily access hospital-grade breast pumps with staff supervision. At one such perinatal psychiatric inpatient unit, high rates of treatment satisfaction and significant improvements in symptoms of depression, anxiety, active suicidal ideation, and overall functioning were observed at discharge.32 Therefore, it is crucial to incorporate strategies in general psychiatry units to improve perinatal care, acknowledging that most patients will not have access to these specialized units.21

A framework to approaching the relational ethics decisions

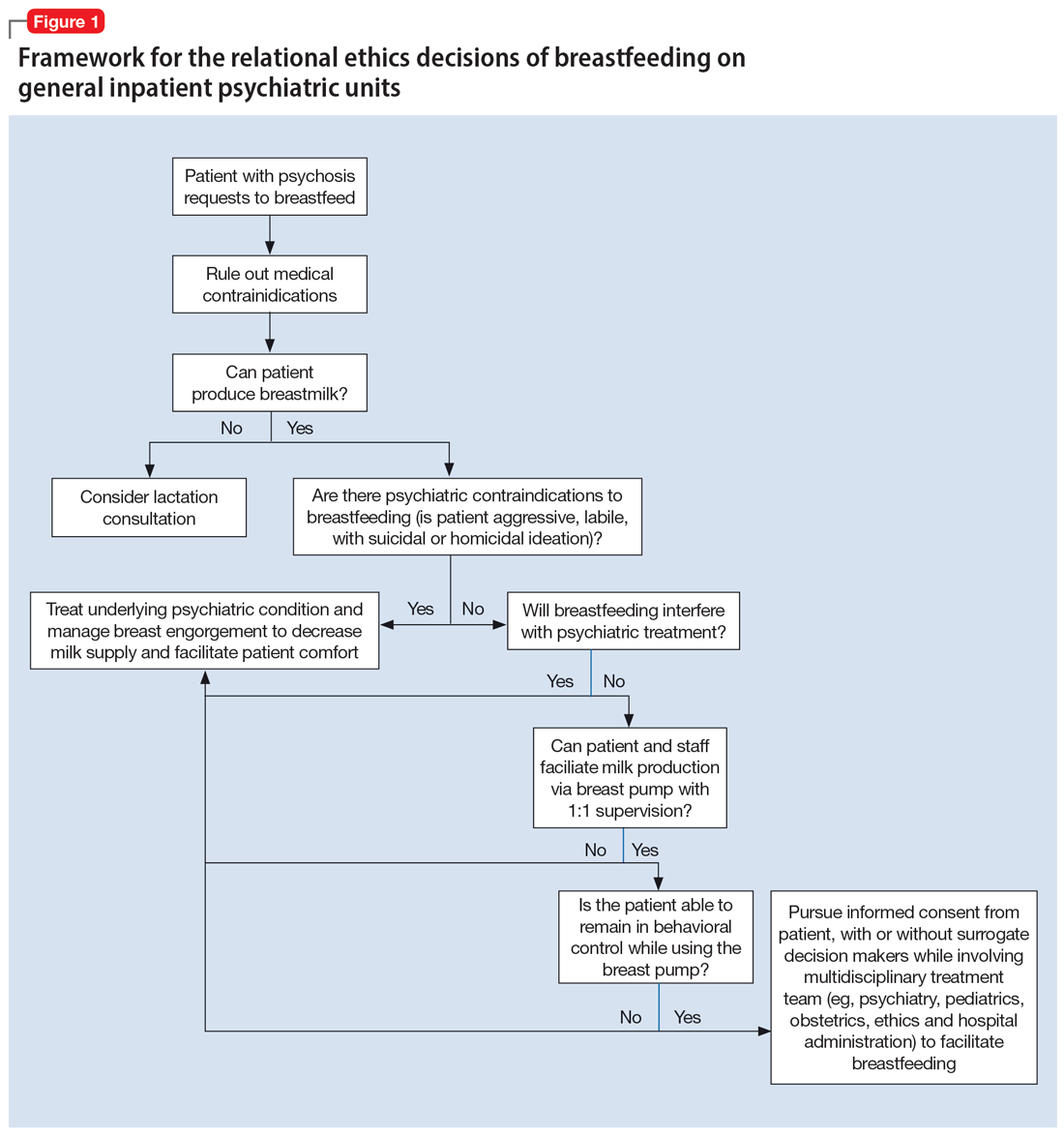

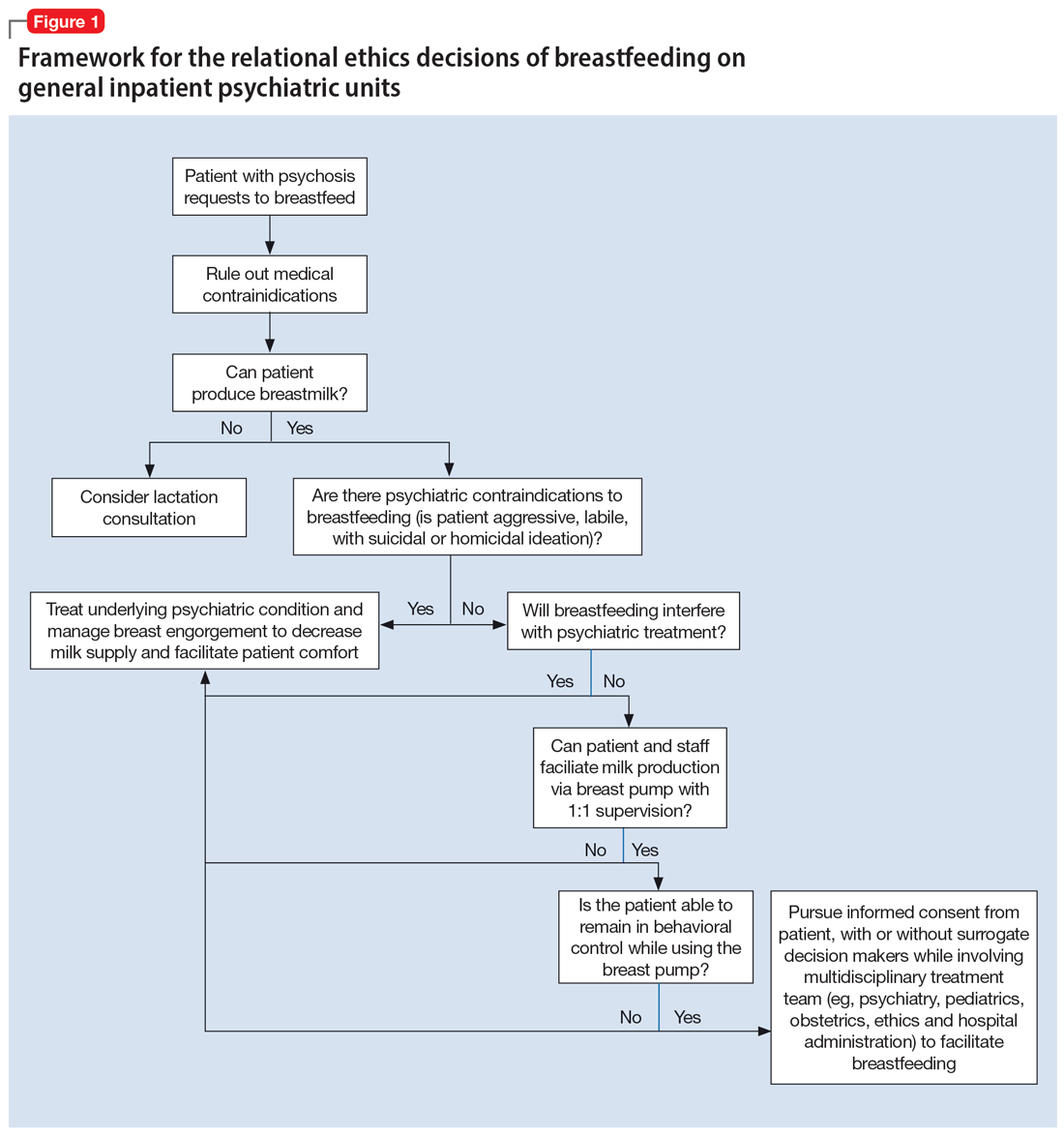

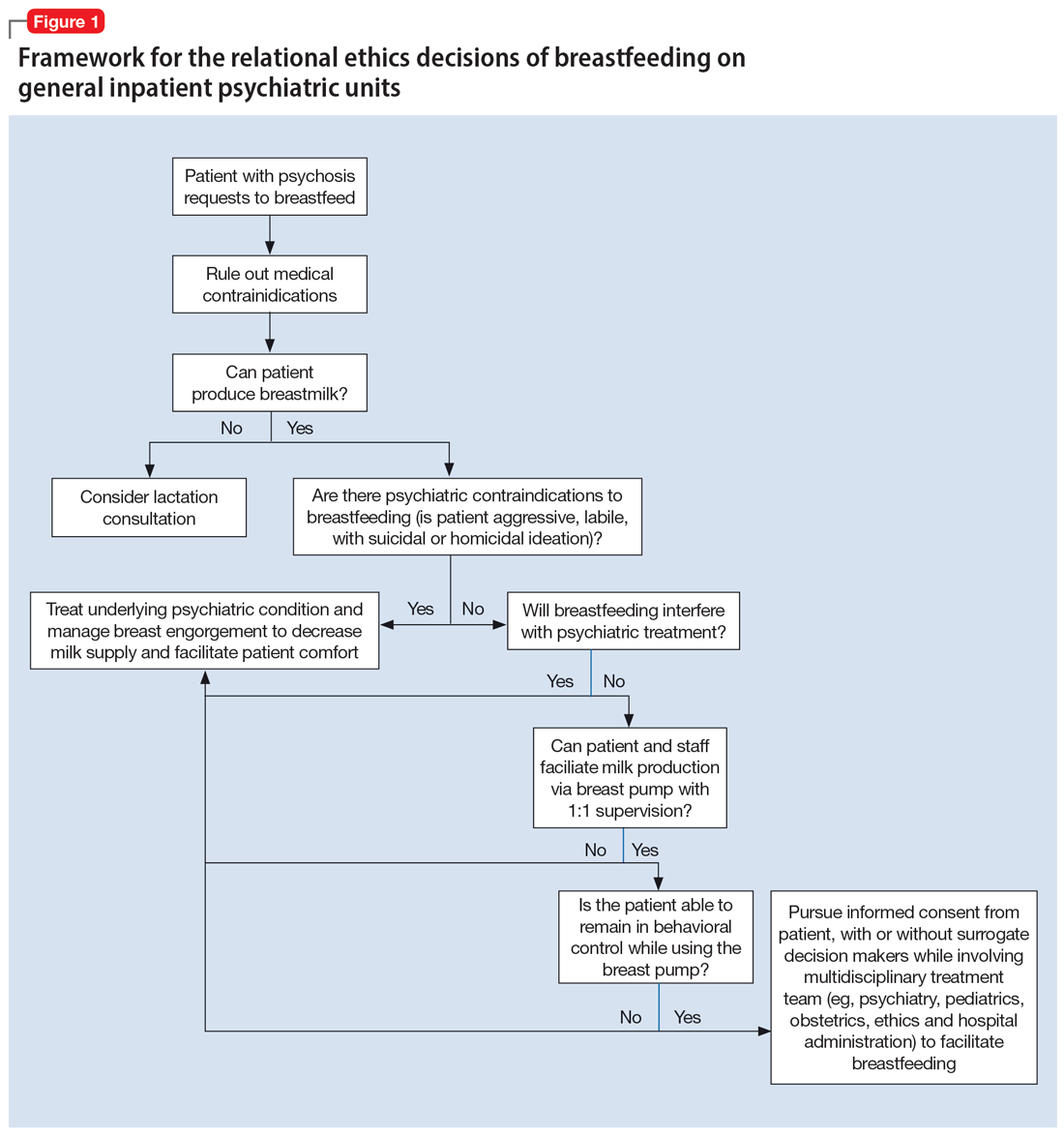

An interdisciplinary team used a relational ethics perspective to carefully analyze the risks and benefits of these complex cases. In Figure 1, we propose a framework for the relational ethics decisions of breastfeeding on general inpatient psychiatric units. In creating this framework, we considered principles of autonomy, beneficence, and nonmaleficence, along with the medical and logistical barriers to breastfeeding.

In Ms. C’s case, the team determined that the risks—which included disrupting the mother’s psychiatric treatment, exposing her to psychological harm due to increasing attachment before remanding the child to CPS custody, and risks to the child due to potential unpredictable agitation driven by the treatment-refractory psychosis of the mother as well as that of other psychiatric patients—outweighed the benefits of breastfeeding. We instead recommended breast pumping as an alternative once Ms. C’s psychiatric stability improved. We presented Ms. C with the option of breast pumping on postpartum Day 5. During a 1-day period in which she showed improved behavioral control, she was counseled on the risks and benefits of breastfeeding and exclusive pumping and was notified that the team would help her with the necessary resources, including consultation with a lactation specialist and breast pump. Despite lactation consultant support, Ms. C had low milk production and difficulty with hand expression, which was very discouraging to her. She produced 1 ounce of milk that was shared with the newborn while in the NICU. Because Ms. C’s psychiatric symptoms continued to be severe, with lability and aggression, and because pumping was triggering distress, the multidisciplinary team determined the best course of care would be to focus on her psychiatric recovery rather than on pumping breastmilk. To reduce milk production and minimize discomfort secondary to breast engorgement, the lactation consultant recommended cold compresses, pain management, and compression of breasts. Ultimately, the mother-infant dyad was unable to reap the benefits of breastfeeding (via pumping or direct breastfeeding) due to the mother’s underlying psychiatric illness, although the staffing, psychosocial support, and logistical limitations contributed to this outcome.33

In Ms. S’s case, the treatment team determined that there were no medical or psychiatric contraindications to breastfeeding, and she was counseled on the risks and benefits of direct breastfeeding and pumping. The treatment team determined it was safe for Ms. S to directly breastfeed as there were no concerns for infant harm postdelivery with constant supervision while on the obstetrics floor. The patient opted to directly breastfeed, which was successful with the guidance of a lactation specialist. When she was transferred to the psychiatric unit on postpartum Day 2, her child was discharged home with the husband. The patient was then encouraged to pump while the psychiatrists monitored her symptoms closely and facilitated increased staff and resources. Transportation of breastmilk was made possible by the family, and on postpartum Day 5, as the patient maintained psychiatric stability, the team discussed with Ms. S and her husband the prospect of direct breastfeeding. The treatment team arranged for separate visitation hours to minimize the possibility of exposing the infant to aggression from other patients on the unit and advocated with hospital leadership to approve of infant visitation on the unit.

Impact of involvement of Child Protective Services

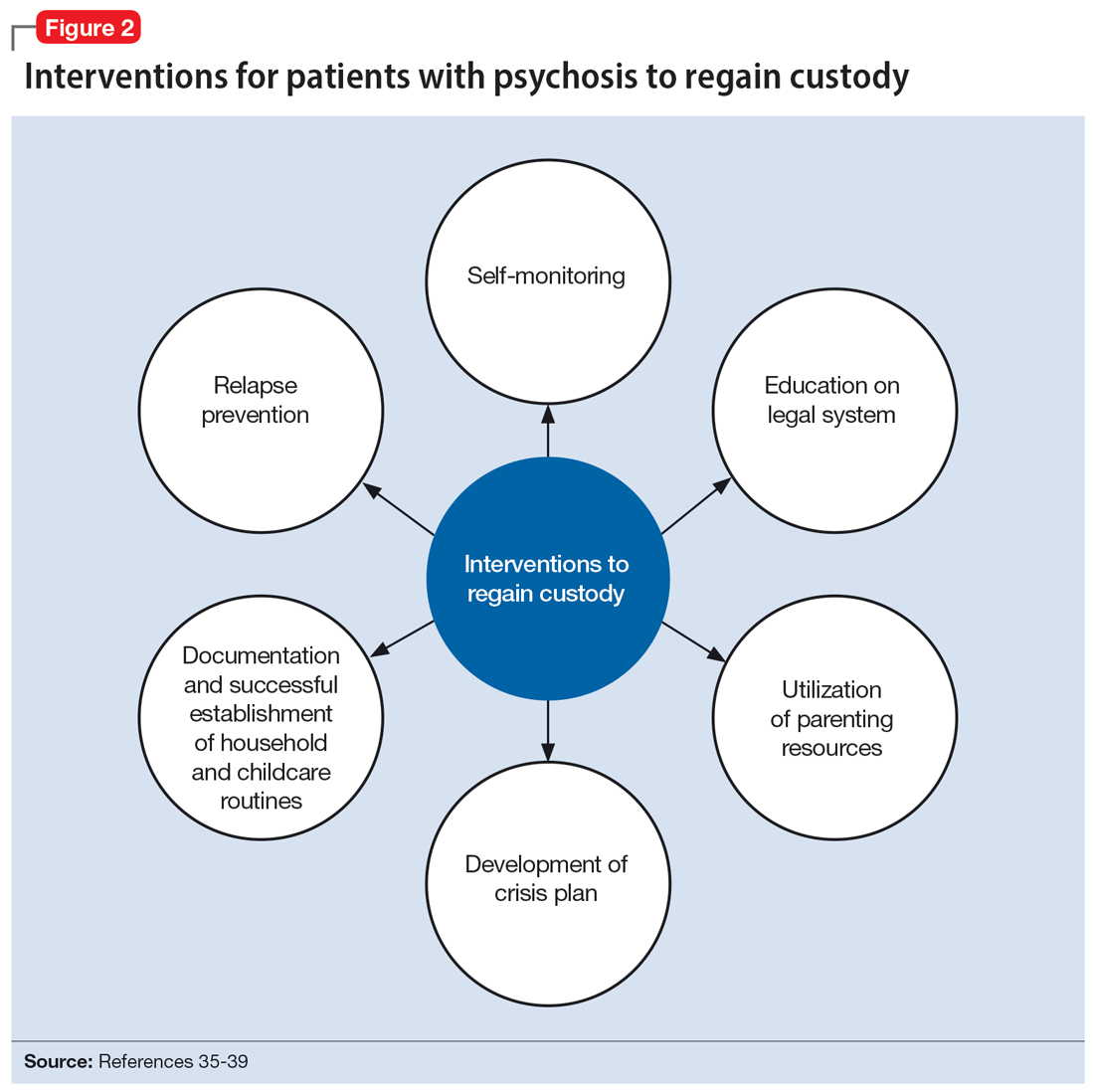

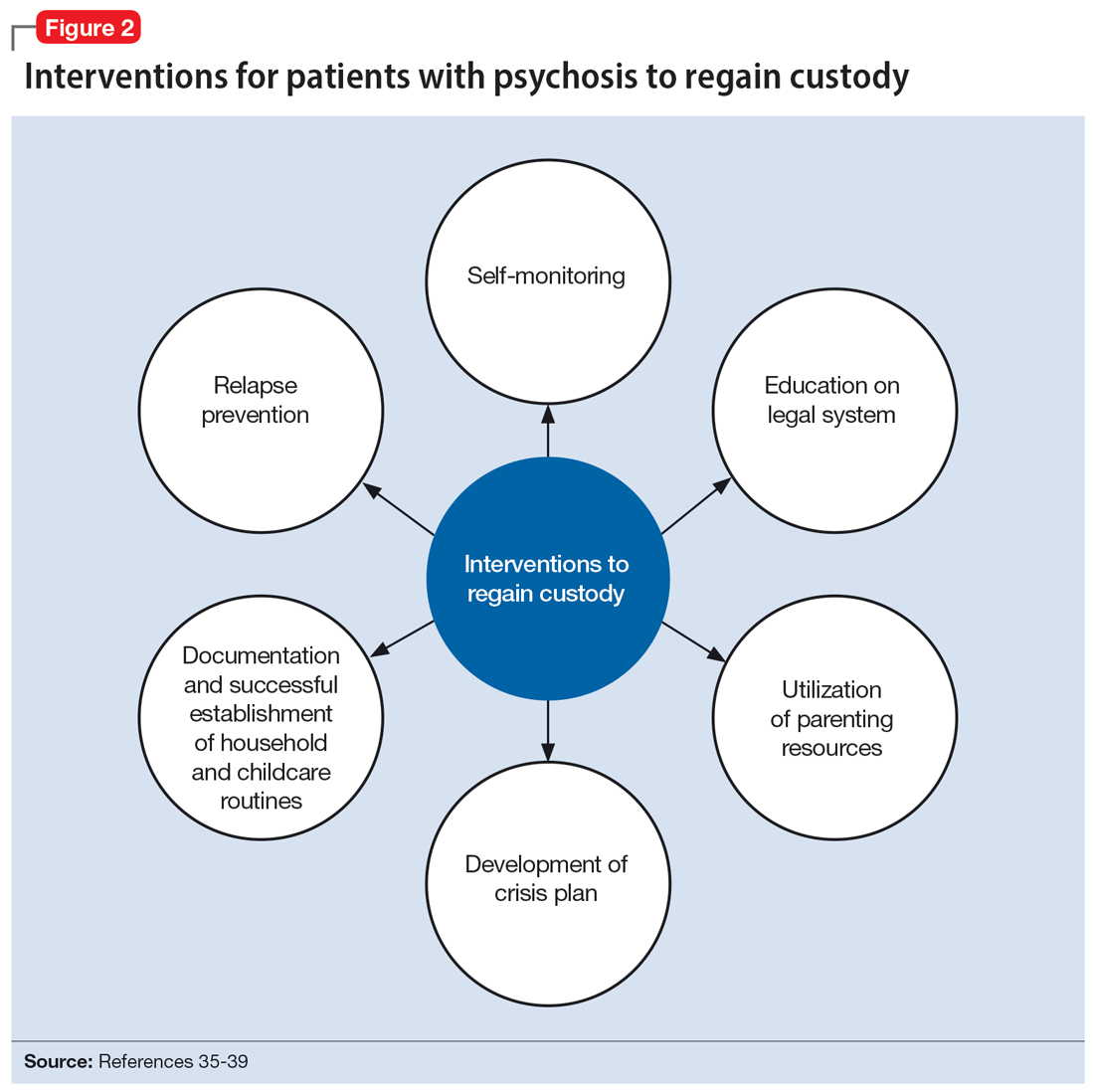

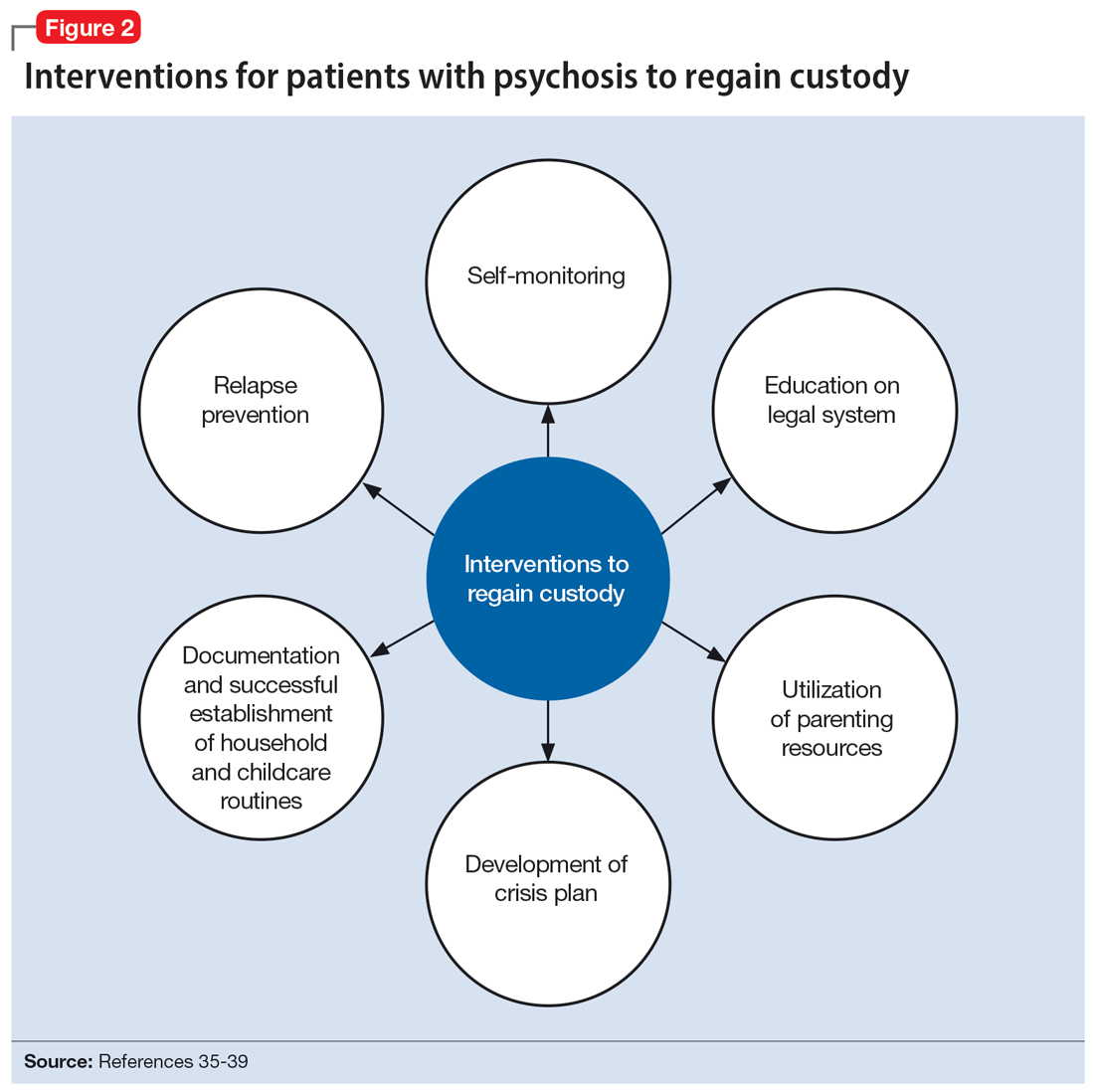

The involvement of CPS also added complexity to Ms. C’s case. Without proper legal guidance, mothers with psychosis who lose custody can find it difficult to navigate the legal system and maintain contact with their children.34 As the prevalence of custody loss in mothers with psychosis is high (approximately 50% according to research published in the last 10 years), effective interventions to reunite the mother and child must be promoted (Figure 2).35-39 Ultimately, the goal of psychiatric hospitalization for perinatal women who have SMI is psychiatric stabilization. The preemptive involvement of psychiatry is crucial because it can allow for early postpartum planning and can provide an opportunity to address feeding options and custody concerns with the patient, social supports and services, and various medical teams. In Ms. C’s case, she visited her baby in the NICU on postpartum Day 2 without consultation with psychiatry or CPS, which posed risks to the patient, infant, and staff. It is vital that various clinicians collaborate with each other and the patient, working towards the goal of optimizing the patient’s mental health to allow for parenting rights in the future and maximizing a sustainable attachment between the parent and child. In Ms. S’s case, the husband was able to facilitate caring for the baby while the mother was hospitalized and played an integral role in the feeding process via pumped breastmilk and transport of the infant for direct breastfeeding.

Continue to: The differences in these 2 cases...

The differences in these 2 cases show the extreme importance of social support to benefit both the mother and child, and the need for more comprehensive social services for women who do not have a social safety net.

Bottom Line

These complex cases highlight an ethical decision-making approach to breastfeeding in perinatal women who have serious mental illness. Collaborative care and shared decision-making, which highlight the interests of the mother and baby, are crucial when assessing the risks and benefits of breastfeeding and pumping breastmilk. Our relational ethics framework can be used to better evaluate and implement breastfeeding options on general psychiatric units.

Related Resources

- Tillman B, Sloan N, Westmoreland P. How COVID-19 affects peripartum women’s mental health. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(6):18-22. doi:10.12788/cp.0129

- Koch J, Preinitz J. Antidepressants for patients who are breastfeeding: what to consider. Current Psychiatry. 2023;22(5):20-23,48. doi:10.12788/cp.0355

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Risperidone • Risperdal

1. Brunner E, Falk DM, Jones M, et al. Olanzapine in pregnancy and breastfeeding: a review of data from global safety surveillance. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol. 2013;14:38. doi:10.1186/2050-6511-14-38

2. Seeman MV. Relational ethics: when mothers suffer from psychosis. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2004;7(3):201-210. doi:10.1007/s00737-004-0054-8

3. Motee A, Jeewon R. Importance of exclusive breastfeeding and complementary feeding among infants. Curr Res Nutr Food Sci. 2014;2(2). doi:10.12944/CRNFSJ.2.2.02

4. Committee Opinion No. 570: breastfeeding in underserved women: increasing initiation and continuation of breastfeeding. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(2 Pt 1):423-427. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000433008.93971.6a

5. Sibolboro Mezzacappa E, Endicott J. Parity mediates the association between infant feeding method and maternal depressive symptoms in the postpartum. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2007;10(6):259-266. doi:10.1007/s00737-007-0207-7

6. Kramer MS, Chalmers B, Hodnett ED, et al. Promotion of Breastfeeding Intervention Trial (PROBIT): a randomized trial in the Republic of Belarus. JAMA. 2001;285(4):413-420. doi:10.1001/jama.285.4.413

7. American Academy of Pediatrics. American Academy of Pediatrics calls for more support for breastfeeding mothers within updated policy recommendations. June 27, 2022. Accessed October 4, 2022. https://www.aap.org/en/news-room/news-releases/aap/2022/american-academy-of-pediatrics-calls-for-more-support-for-breastfeeding-mothers-within-updated-policy-recommendations

8. Hipwell AE, Kumar R. Maternal psychopathology and prediction of outcome based on mother-infant interaction ratings (BMIS). Br J Psychiatry. 1996;169(5):655-661. doi:10.1192/bjp.169.5.655

9. Chandra PS, Bhargavaraman RP, Raghunandan VN, et al. Delusions related to infant and their association with mother-infant interactions in postpartum psychotic disorders. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2006;9(5):285-288. doi:10.1007/s00737-006-0147-7

10. Klinger G, Stahl B, Fusar-Poli P, et al. Antipsychotic drugs and breastfeeding. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev. 2013;10(3):308-317.

11. Uguz F. A new safety scoring system for the use of psychotropic drugs during lactation. Am J Ther. 2021;28(1):e118-e126. doi:10.1097/MJT.0000000000000909

12. Hale TW, Krutsch K. Hale’s Medications & Mothers’ Milk, 2023: A Manual of Lactational Pharmacology. 20th ed. Springer Publishing Company; 2023.

13. Komaroff A. Aripiprazole and lactation failure: the importance of shared decision making. A case report. Case Rep Womens Health. 2021;30:e00308. doi:10.1016/j.crwh.2021.e00308

14. Dennis CL, McQueen K. Does maternal postpartum depressive symptomatology influence infant feeding outcomes? Acta Pediatr. 2007;96(4):590-594. doi:10.1111/j.1651-2227.2007.00184.x

15. Chaput KH, Nettel-Aguirre A, Musto R, et al. Breastfeeding difficulties and supports and risk of postpartum depression in a cohort of women who have given birth in Calgary: a prospective cohort study. CMAJ Open. 2016;4(1):E103-E109. doi:10.9778/cmajo.20150009

16. Dias CC, Figueiredo B. Breastfeeding and depression: a systematic review of the literature. J Affect Disord. 2015;171:142-154. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2014.09.022

17. Brown A, Rance J, Bennett P. Understanding the relationship between breastfeeding and postnatal depression: the role of pain and physical difficulties. J Adv Nurs. 2016;72(2):273-282. doi:10.1111/jan.12832

18. Rosenbaum KA. Exclusive breastmilk pumping: a concept analysis. Nurs Forum. 2022;57(5):946-953. doi:10.1111/nuf.12766

19. Boone KM, Geraghty SR, Keim SA. Feeding at the breast and expressed milk feeding: associations with otitis media and diarrhea in infants. J Pediatr. 2016;174:118-125. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.04.006

20. Epstein LJ, Kristo D, Strollo PJ Jr, et al; Adult Obstructive Sleep Apnea Task Force of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Clinical guideline for the evaluation, management and long-term care of obstructive sleep apnea in adults. J Clin Sleep Med. 2009;5(3):263-276.

21. Caan MP, Sreshta NE, Okwerekwu JA, et al. Clinical and legal considerations regarding breastfeeding on psychiatric units. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2022;50(2):200-207. doi:10.29158/JAAPL.210086-21

22. Glangeaud-Freudenthal NMC, Rainelli C, Cazas O, et al. Inpatient mother and baby psychiatric units (MBUs) and day cares. In: Sutter-Dallay AL, Glangeaud-Freudenthal NC, Guedeney A, et al, eds. Joint Care of Parents and Infants in Perinatal Psychiatry. Springer, Cham; 2016:147-164. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-21557-0_10

23. Dembosky A. A humane approach to caring for new mothers in psychiatric crisis. Health Aff (Millwood). 2021;40(10):1528-1533. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2021.01288

24. Connellan K, Bartholomaeus C, Due C, et al. A systematic review of research on psychiatric mother-baby units. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2017;20(3):373-388. doi:10.1007/s00737-017-0718-9

25. Griffiths J, Lever Taylor B, Morant N, et al. A qualitative comparison of experiences of specialist mother and baby units versus general psychiatric wards. BMC Psychiatry. 2019;19(1):401. doi:10.1186/s12888-019-2389-8

26. Heron J, Gilbert N, Dolman C, et al. Information and support needs during recovery from postpartum psychosis. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2012;15(3):155-165. doi:10.1007/s00737-012-0267-1

27. Robertson E, Lyons A. Living with puerperal psychosis: a qualitative analysis. Psychol Psychother. 2003;76(Pt 4):411-431. doi:10.1348/147608303770584755

28. Mental Welfare Commission for Scotland. Perinatal Themed Visit Report: Keeping Mothers and Babies in Mind. Mental Welfare Commission for Scotland; 2016.

29. Wisner KL, Jennings KD, Conley B. Clinical dilemmas due to the lack of inpatient mother-baby units. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1996;26(4):479-493. doi:10.2190/NFJK-A4V7-CXUU-AM89

30. Battle CL, Howard MM. A mother-baby psychiatric day hospital: history, rationale, and why perinatal mental health is important for obstetric medicine. Obstet Med. 2014;7(2):66-70. doi:10.1177/1753495X13514402

31. Bullard ES, Meltzer-Brody S, Rubinow DR. The need for comprehensive psychiatric perinatal care-the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Department of Psychiatry, Center for Women’s Mood Disorders launches the first dedicated inpatient program in the United States. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;201(5):e10-e11. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2009.05.004

32. Meltzer-Brody S, Brandon AR, Pearson B, et al. Evaluating the clinical effectiveness of a specialized perinatal psychiatry inpatient unit. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2014;17(2):107-113. doi:10.1007/s00737-013-0390-7

33. Alvarez-Toro V. Gender-specific care for women in psychiatric units. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2022;JAAPL.220015-21. doi:10.29158/JAAPL.220015-21

34. Diaz-Caneja A, Johnson S. The views and experiences of severely mentally ill mothers--a qualitative study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2004;39(6):472-482. doi:10.1007/s00127-004-0772-2

35. Gewurtz R, Krupa T, Eastabrook S, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of parenting among people served by assertive community treatment. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2004;28(1):63-65. doi:10.2975/28.2004.63.65

36. Howard LM, Kumar R, Thornicroft G. Psychosocial characteristics and needs of mothers with psychotic disorders. Br J Psychiatry. 2001;178:427-432. doi:10.1192/bjp.178.5.427

37. Hollingsworth LD. Child custody loss among women with persistent severe mental illness. Social Work Research. 2004;28(4):199-209. doi:10.1093/swr/28.4.199

38. Dipple H, Smith S, Andrews H, et al. The experience of motherhood in women with severe and enduring mental illness. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiolf. 2002;37(7):336-340. doi:10.1007/s00127-002-0559-2

39. Seeman MV. Intervention to prevent child custody loss in mothers with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res Treatment. 2012;2012:796763. doi:10.1155/2012/796763

Difficult ethical situations can arise when treating perinatal women who have serious mental illness (SMI). Clinicians must consider ethical issues related to administering antipsychotic medications, the safety of breastfeeding, and concerns for child welfare. They need to carefully weigh the risks and benefits of each decision when treating perinatal women who have SMI. Ethical guidelines can help clinicians best support families in these situations.

In this article, we describe 2 cases of women with psychotic disorders who requested to breastfeed after delivering their child during an inpatient psychiatric hospitalization. The course of their hospitalizations illustrated common ethical questions and facilitated the creation of a framework to assist with complex decision-making regarding breastfeeding on inpatient psychiatric units.

CASE 1

Ms. C, age 41, is multigravida with a psychiatric history of chronic, severe schizoaffective disorder and lives in supportive housing. When Ms. C presents to the hospital in search of a rape kit, clinicians discover she is 22 weeks pregnant but has not received any prenatal care. Psychiatry is consulted because she is found to be intermittently agitated and endorses grandiose delusions. Ms. C requires involuntary hospitalization for decompensated psychosis because she refuses prenatal and psychiatric care. Because it has reassuring reproductive safety data,1 olanzapine 5 mg/d is started. However, Ms. C experiences minimal improvement from a maximum dose of 20 mg/d. After 13 weeks on the psychiatry unit, she is transferred to obstetrics service for preeclampsia with severe features. Ms. C requires an urgent cesarean delivery at 37 weeks. Her baby boy is transferred to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) for transient tachypnea. After delivery and in consultation with psychiatry, the pediatrics team calls Child Protective Services (CPS) due to concern for neglect driven by Ms. C’s psychiatric condition. Ms. C visits the child with medical unit staff supervision in the NICU without consulting with the psychiatry service or CPS. On postpartum Day 2, Ms. C is transferred back to psychiatry for persistent psychosis.

On postpartum Day 3, Ms. C starts to produce breastmilk and requests to breastfeed. At this time, the multidisciplinary team determines she is not able to visit her child in the NICU due to psychiatric instability. No plan is developed to facilitate hand expression or pumping of breastmilk while Ms. C is on the psychiatric unit. The clinical teams discuss whether the benefits of breastfeeding and/or pumping breastmilk would outweigh the risks. CPS determines that Ms. C is unable to retain custody and places the child in kinship foster care while awaiting clinical improvement from her.

CASE 2

Ms. S, age 32, has a history of schizophrenia. She lives with her husband and parents. She is pregnant for the first time and has been receiving consistent prenatal care. Ms. S is brought to the hospital by her husband for bizarre behavior and paranoia after self-discontinuing risperidone 2 mg twice daily due to concern about the medication’s influence on her pregnancy. An ultrasound confirms she is 37 weeks pregnant. Psychiatry is consulted because Ms. S is internally preoccupied, delusional, and endorses auditory hallucinations. She requires involuntary hospitalization for decompensated psychosis. During admission, Ms. S experiences improvement of her psychiatric symptoms while receiving risperidone 2 mg twice daily, which she takes consistently after receiving extensive psychoeducation regarding its safety profile during pregnancy and lactation.

After 2 weeks on the psychiatry unit, Ms. S’s care team transfers her to the obstetrics service with one-to-one supervision. At 39 weeks gestation, she has a vaginal delivery without complications. Because there are no concerns about infant harm, obstetrics, pediatrics, and psychiatry coordinate care so the baby can room in with Ms. S, her husband, and a staff supervisor to facilitate bonding. Ms. S starts to lactate, wishes to breastfeed, and meets with lactation, pediatric, obstetric, and psychiatric specialists to discuss the risks and benefits of breastfeeding and pumping breastmilk. She pursues direct breastfeeding until the baby is discharged home with the husband at postpartum Day 2. CPS is not called because there are no concerns for parental abuse or neglect at the infant’s discharge.

On postpartum Day 2, the obstetrics service transfers Ms. S back to the psychiatric unit for further treatment of her paranoia. She wishes to pump breastmilk while hospitalized, so the treatment team supplies a breast pump, facilitates the storage of breastmilk, and coordinates supervision during pumping to reduce the ligature risk. Ms. S’s husband visits daily to transport the milk and feed the infant breastmilk and formula to meet its nutritional needs. Ms. S maintains psychiatric stability while breast pumping, and the team helps transition her to breastfeeding during visitation with her husband and infant until she is discharged home at 2 weeks postpartum.

Continue to: Approaching care with a relational ethics framework

Approaching care with a relational ethics framework

A relational ethics framework was constructed to evaluate whether to support breastfeeding for both patients during their psychiatric hospitalizations. A relational ethics perspective is defined as “a moral responsibility within a context of human relations” [that] “recognizes the human interdependency and reciprocity within which personal autonomy is embedded.”2 This framework values connectedness and commonality between various and even conflicting parties. In the setting of a clinician-patient relationship, health care decisions are made with consideration of the patient’s traditional beliefs, values, and principles rather than the application of impartial moral principles. For these complex cases, this framework was chosen to determine the safest possible outcome for both mother and child.

Risks/benefits of breastfeeding by patients who have SMI

There are several methods of breastfeeding, including direct breastfeeding and other ways of expressing breastmilk such as pumping or hand expression.3 Unlike other forms of feeding using breastmilk, direct breastfeeding has been extensively studied, has well-established medical and psychological benefits for newborns and mothers, and enhances long-term bonding.4 Compared with their counterparts who do not breastfeed, mothers who breastfeed have lower rates of unintended pregnancy, cardiovascular disease, postpartum bleeding, osteoporosis, and breast and ovarian cancer.5 Among its key psychological benefits, breastfeeding is associated with an increase in maternal self-efficacy and, in some research, has been shown to be associated with a decreased risk of postpartum depression and stress.Additionally, breastfed infants experience lower rates of childhood infection and obesity, and improved nutrition, cognitive development, and immune function.6 The American Academy of Pediatrics recognizes these benefits and recommends that women exclusively breastfeed for 6 months postpartum and continue to breastfeed for 2 years or beyond if mutually desired by the mother and child.7 Absolute contraindications to breastfeeding must be ruled out (eg, infant classic galactosemia; maternal use of illicit substances such as cocaine, opioids, or phencyclidine; maternal HIV infection, etc).

The risks of breastfeeding by patients who have SMI must also be considered. In severe situations, the infant can be exposed to a mother’s agitation secondary to psychosis.8,9 The transmission of antipsychotic medication through breastmilk and associated adverse effects (eg, sedation, poor feeding, and extrapyramidal symptoms) are also potential risks and varies among different antipsychotic medications.1,10 Therefore, when prescribing an antipsychotic for a patient with SMI who breastfeeds, it is crucial to consider the medication’s safety profile as well as other factors, such as the relative infant dose (the weight-adjusted [ie, mg/kg] percentage of the maternal dosage ingested by a fully breastfed infant) and the molecular characteristics of the medication.10-12 Neonates should be routinely monitored for adverse effects, medication toxicity, and withdrawal symptoms, and care should be coordinated with the infant’s pediatrician. Certain antipsychotic medications, such as aripiprazole, may impact breastmilk production through the dopamine agonist’s interference of the prolactin reflex and anticholinergic properties.11,13 For a patient with SMI, perhaps the most significant risk involves the time and resources needed for breastfeeding, which can interfere with sleep and psychiatric treatment and possibly further exacerbate psychiatric symptoms.14-16 Additionally, breastfeeding difficulties or disruption can increase the risk of psychiatric symptoms and psychological distress.17 In Ms. C’s case, there was a delay in the baby latching as well as multiple medical and psychiatric factors that hindered the milk-ejection reflex to properly initiate; both of these factors rendered breastfeeding particularly difficult while Ms. C was on the inpatient psychiatry unit.17 In comparison, Ms. S was able to bond with her infant shortly after delivery, which facilitated the milk-ejection reflex and lactation.

Patients who wish to directly breastfeed but struggle to do so while tending to their acute psychiatric condition can benefit from expression of breastmilk that can be provided to the infant or discarded to facilitate breastfeeding in the future.18 While expression of breastmilk may not be as advantageous for infant health as direct breastfeeding due to the potential changes in breastmilk composition from collecting, storing, and heating, this option can be more protective than formula feeding and facilitate future breastfeeding.19 In these clinical scenarios, it is standard care to provide a hospital-grade breast pump to the patient, much like a continuous positive airway pressure machine is provided to patients with obstructive sleep apnea.20 However, there is often considerable difficulty obtaining proper breastfeeding equipment and a lack of services devoted to perinatal care in general inpatient settings. Barriers to direct breastfeeding and pumping of breastmilk are highlighted in the Table.21

Limitations on breastfeeding on an inpatient unit

The limitations in care and restrictions placed on breastfeeding are more optimally addressed in a mother and baby unit (MBU). MBUs are specialized inpatient psychiatric units designed for mothers experiencing severe perinatal psychiatric difficulties. Unlike general psychiatric units, MBUs allow for joint, full-time admission of mothers and their infants. These units also include multidisciplinary staff who specialize in treating perinatal mental health issues as well as infant care and child development.22 Admission into an MBU is considered best practice for new mothers requiring treatment, particularly in the United Kingdom, Australia, and France, as it is well-recognized that the separation of mother and baby can be psychologically harmful.23 In the UK, most patients admitted to an MBU showed significant improvement of their psychiatric symptoms and reported overall high satisfaction with care.24,25 Patients who experience postpartum psychosis prefer MBUs over general psychiatric units because the latter often lack specialized perinatal support, appropriate visitor arrangements, and adequate time with their infant.26-28

Continue to: The resistance to adopting MBUs in the United States...

The resistance to adopting MBUs in the United States has posed significant barriers in care for perinatal patients and has been attributed to financial barriers, medicolegal risk, staffing, and safety concerns.29 Though currently there are no MBUs in the US, other specialized units have been created. A partial day hospitalization program created in 2000 in Rhode Island for mothers and infants revolutionized the psychiatric care experience for new mothers.30 Since then, other institutions have significantly expanded their services to include perinatal psychiatry inpatient units, yet unlike MBUs, these units typically do not provide overnight rooming-in with infants.31 They have the necessary resources and facilities to accommodate the mother’s needs and maximize positive mother-infant interaction, while actively integrating the infant into the mother’s treatment. Breast pumping is treated as a necessary medical procedure and patients can easily access hospital-grade breast pumps with staff supervision. At one such perinatal psychiatric inpatient unit, high rates of treatment satisfaction and significant improvements in symptoms of depression, anxiety, active suicidal ideation, and overall functioning were observed at discharge.32 Therefore, it is crucial to incorporate strategies in general psychiatry units to improve perinatal care, acknowledging that most patients will not have access to these specialized units.21

A framework to approaching the relational ethics decisions

An interdisciplinary team used a relational ethics perspective to carefully analyze the risks and benefits of these complex cases. In Figure 1, we propose a framework for the relational ethics decisions of breastfeeding on general inpatient psychiatric units. In creating this framework, we considered principles of autonomy, beneficence, and nonmaleficence, along with the medical and logistical barriers to breastfeeding.

In Ms. C’s case, the team determined that the risks—which included disrupting the mother’s psychiatric treatment, exposing her to psychological harm due to increasing attachment before remanding the child to CPS custody, and risks to the child due to potential unpredictable agitation driven by the treatment-refractory psychosis of the mother as well as that of other psychiatric patients—outweighed the benefits of breastfeeding. We instead recommended breast pumping as an alternative once Ms. C’s psychiatric stability improved. We presented Ms. C with the option of breast pumping on postpartum Day 5. During a 1-day period in which she showed improved behavioral control, she was counseled on the risks and benefits of breastfeeding and exclusive pumping and was notified that the team would help her with the necessary resources, including consultation with a lactation specialist and breast pump. Despite lactation consultant support, Ms. C had low milk production and difficulty with hand expression, which was very discouraging to her. She produced 1 ounce of milk that was shared with the newborn while in the NICU. Because Ms. C’s psychiatric symptoms continued to be severe, with lability and aggression, and because pumping was triggering distress, the multidisciplinary team determined the best course of care would be to focus on her psychiatric recovery rather than on pumping breastmilk. To reduce milk production and minimize discomfort secondary to breast engorgement, the lactation consultant recommended cold compresses, pain management, and compression of breasts. Ultimately, the mother-infant dyad was unable to reap the benefits of breastfeeding (via pumping or direct breastfeeding) due to the mother’s underlying psychiatric illness, although the staffing, psychosocial support, and logistical limitations contributed to this outcome.33

In Ms. S’s case, the treatment team determined that there were no medical or psychiatric contraindications to breastfeeding, and she was counseled on the risks and benefits of direct breastfeeding and pumping. The treatment team determined it was safe for Ms. S to directly breastfeed as there were no concerns for infant harm postdelivery with constant supervision while on the obstetrics floor. The patient opted to directly breastfeed, which was successful with the guidance of a lactation specialist. When she was transferred to the psychiatric unit on postpartum Day 2, her child was discharged home with the husband. The patient was then encouraged to pump while the psychiatrists monitored her symptoms closely and facilitated increased staff and resources. Transportation of breastmilk was made possible by the family, and on postpartum Day 5, as the patient maintained psychiatric stability, the team discussed with Ms. S and her husband the prospect of direct breastfeeding. The treatment team arranged for separate visitation hours to minimize the possibility of exposing the infant to aggression from other patients on the unit and advocated with hospital leadership to approve of infant visitation on the unit.

Impact of involvement of Child Protective Services

The involvement of CPS also added complexity to Ms. C’s case. Without proper legal guidance, mothers with psychosis who lose custody can find it difficult to navigate the legal system and maintain contact with their children.34 As the prevalence of custody loss in mothers with psychosis is high (approximately 50% according to research published in the last 10 years), effective interventions to reunite the mother and child must be promoted (Figure 2).35-39 Ultimately, the goal of psychiatric hospitalization for perinatal women who have SMI is psychiatric stabilization. The preemptive involvement of psychiatry is crucial because it can allow for early postpartum planning and can provide an opportunity to address feeding options and custody concerns with the patient, social supports and services, and various medical teams. In Ms. C’s case, she visited her baby in the NICU on postpartum Day 2 without consultation with psychiatry or CPS, which posed risks to the patient, infant, and staff. It is vital that various clinicians collaborate with each other and the patient, working towards the goal of optimizing the patient’s mental health to allow for parenting rights in the future and maximizing a sustainable attachment between the parent and child. In Ms. S’s case, the husband was able to facilitate caring for the baby while the mother was hospitalized and played an integral role in the feeding process via pumped breastmilk and transport of the infant for direct breastfeeding.

Continue to: The differences in these 2 cases...

The differences in these 2 cases show the extreme importance of social support to benefit both the mother and child, and the need for more comprehensive social services for women who do not have a social safety net.

Bottom Line

These complex cases highlight an ethical decision-making approach to breastfeeding in perinatal women who have serious mental illness. Collaborative care and shared decision-making, which highlight the interests of the mother and baby, are crucial when assessing the risks and benefits of breastfeeding and pumping breastmilk. Our relational ethics framework can be used to better evaluate and implement breastfeeding options on general psychiatric units.

Related Resources

- Tillman B, Sloan N, Westmoreland P. How COVID-19 affects peripartum women’s mental health. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(6):18-22. doi:10.12788/cp.0129

- Koch J, Preinitz J. Antidepressants for patients who are breastfeeding: what to consider. Current Psychiatry. 2023;22(5):20-23,48. doi:10.12788/cp.0355

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Risperidone • Risperdal

Difficult ethical situations can arise when treating perinatal women who have serious mental illness (SMI). Clinicians must consider ethical issues related to administering antipsychotic medications, the safety of breastfeeding, and concerns for child welfare. They need to carefully weigh the risks and benefits of each decision when treating perinatal women who have SMI. Ethical guidelines can help clinicians best support families in these situations.

In this article, we describe 2 cases of women with psychotic disorders who requested to breastfeed after delivering their child during an inpatient psychiatric hospitalization. The course of their hospitalizations illustrated common ethical questions and facilitated the creation of a framework to assist with complex decision-making regarding breastfeeding on inpatient psychiatric units.

CASE 1

Ms. C, age 41, is multigravida with a psychiatric history of chronic, severe schizoaffective disorder and lives in supportive housing. When Ms. C presents to the hospital in search of a rape kit, clinicians discover she is 22 weeks pregnant but has not received any prenatal care. Psychiatry is consulted because she is found to be intermittently agitated and endorses grandiose delusions. Ms. C requires involuntary hospitalization for decompensated psychosis because she refuses prenatal and psychiatric care. Because it has reassuring reproductive safety data,1 olanzapine 5 mg/d is started. However, Ms. C experiences minimal improvement from a maximum dose of 20 mg/d. After 13 weeks on the psychiatry unit, she is transferred to obstetrics service for preeclampsia with severe features. Ms. C requires an urgent cesarean delivery at 37 weeks. Her baby boy is transferred to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) for transient tachypnea. After delivery and in consultation with psychiatry, the pediatrics team calls Child Protective Services (CPS) due to concern for neglect driven by Ms. C’s psychiatric condition. Ms. C visits the child with medical unit staff supervision in the NICU without consulting with the psychiatry service or CPS. On postpartum Day 2, Ms. C is transferred back to psychiatry for persistent psychosis.

On postpartum Day 3, Ms. C starts to produce breastmilk and requests to breastfeed. At this time, the multidisciplinary team determines she is not able to visit her child in the NICU due to psychiatric instability. No plan is developed to facilitate hand expression or pumping of breastmilk while Ms. C is on the psychiatric unit. The clinical teams discuss whether the benefits of breastfeeding and/or pumping breastmilk would outweigh the risks. CPS determines that Ms. C is unable to retain custody and places the child in kinship foster care while awaiting clinical improvement from her.

CASE 2

Ms. S, age 32, has a history of schizophrenia. She lives with her husband and parents. She is pregnant for the first time and has been receiving consistent prenatal care. Ms. S is brought to the hospital by her husband for bizarre behavior and paranoia after self-discontinuing risperidone 2 mg twice daily due to concern about the medication’s influence on her pregnancy. An ultrasound confirms she is 37 weeks pregnant. Psychiatry is consulted because Ms. S is internally preoccupied, delusional, and endorses auditory hallucinations. She requires involuntary hospitalization for decompensated psychosis. During admission, Ms. S experiences improvement of her psychiatric symptoms while receiving risperidone 2 mg twice daily, which she takes consistently after receiving extensive psychoeducation regarding its safety profile during pregnancy and lactation.

After 2 weeks on the psychiatry unit, Ms. S’s care team transfers her to the obstetrics service with one-to-one supervision. At 39 weeks gestation, she has a vaginal delivery without complications. Because there are no concerns about infant harm, obstetrics, pediatrics, and psychiatry coordinate care so the baby can room in with Ms. S, her husband, and a staff supervisor to facilitate bonding. Ms. S starts to lactate, wishes to breastfeed, and meets with lactation, pediatric, obstetric, and psychiatric specialists to discuss the risks and benefits of breastfeeding and pumping breastmilk. She pursues direct breastfeeding until the baby is discharged home with the husband at postpartum Day 2. CPS is not called because there are no concerns for parental abuse or neglect at the infant’s discharge.

On postpartum Day 2, the obstetrics service transfers Ms. S back to the psychiatric unit for further treatment of her paranoia. She wishes to pump breastmilk while hospitalized, so the treatment team supplies a breast pump, facilitates the storage of breastmilk, and coordinates supervision during pumping to reduce the ligature risk. Ms. S’s husband visits daily to transport the milk and feed the infant breastmilk and formula to meet its nutritional needs. Ms. S maintains psychiatric stability while breast pumping, and the team helps transition her to breastfeeding during visitation with her husband and infant until she is discharged home at 2 weeks postpartum.

Continue to: Approaching care with a relational ethics framework

Approaching care with a relational ethics framework

A relational ethics framework was constructed to evaluate whether to support breastfeeding for both patients during their psychiatric hospitalizations. A relational ethics perspective is defined as “a moral responsibility within a context of human relations” [that] “recognizes the human interdependency and reciprocity within which personal autonomy is embedded.”2 This framework values connectedness and commonality between various and even conflicting parties. In the setting of a clinician-patient relationship, health care decisions are made with consideration of the patient’s traditional beliefs, values, and principles rather than the application of impartial moral principles. For these complex cases, this framework was chosen to determine the safest possible outcome for both mother and child.

Risks/benefits of breastfeeding by patients who have SMI

There are several methods of breastfeeding, including direct breastfeeding and other ways of expressing breastmilk such as pumping or hand expression.3 Unlike other forms of feeding using breastmilk, direct breastfeeding has been extensively studied, has well-established medical and psychological benefits for newborns and mothers, and enhances long-term bonding.4 Compared with their counterparts who do not breastfeed, mothers who breastfeed have lower rates of unintended pregnancy, cardiovascular disease, postpartum bleeding, osteoporosis, and breast and ovarian cancer.5 Among its key psychological benefits, breastfeeding is associated with an increase in maternal self-efficacy and, in some research, has been shown to be associated with a decreased risk of postpartum depression and stress.Additionally, breastfed infants experience lower rates of childhood infection and obesity, and improved nutrition, cognitive development, and immune function.6 The American Academy of Pediatrics recognizes these benefits and recommends that women exclusively breastfeed for 6 months postpartum and continue to breastfeed for 2 years or beyond if mutually desired by the mother and child.7 Absolute contraindications to breastfeeding must be ruled out (eg, infant classic galactosemia; maternal use of illicit substances such as cocaine, opioids, or phencyclidine; maternal HIV infection, etc).

The risks of breastfeeding by patients who have SMI must also be considered. In severe situations, the infant can be exposed to a mother’s agitation secondary to psychosis.8,9 The transmission of antipsychotic medication through breastmilk and associated adverse effects (eg, sedation, poor feeding, and extrapyramidal symptoms) are also potential risks and varies among different antipsychotic medications.1,10 Therefore, when prescribing an antipsychotic for a patient with SMI who breastfeeds, it is crucial to consider the medication’s safety profile as well as other factors, such as the relative infant dose (the weight-adjusted [ie, mg/kg] percentage of the maternal dosage ingested by a fully breastfed infant) and the molecular characteristics of the medication.10-12 Neonates should be routinely monitored for adverse effects, medication toxicity, and withdrawal symptoms, and care should be coordinated with the infant’s pediatrician. Certain antipsychotic medications, such as aripiprazole, may impact breastmilk production through the dopamine agonist’s interference of the prolactin reflex and anticholinergic properties.11,13 For a patient with SMI, perhaps the most significant risk involves the time and resources needed for breastfeeding, which can interfere with sleep and psychiatric treatment and possibly further exacerbate psychiatric symptoms.14-16 Additionally, breastfeeding difficulties or disruption can increase the risk of psychiatric symptoms and psychological distress.17 In Ms. C’s case, there was a delay in the baby latching as well as multiple medical and psychiatric factors that hindered the milk-ejection reflex to properly initiate; both of these factors rendered breastfeeding particularly difficult while Ms. C was on the inpatient psychiatry unit.17 In comparison, Ms. S was able to bond with her infant shortly after delivery, which facilitated the milk-ejection reflex and lactation.

Patients who wish to directly breastfeed but struggle to do so while tending to their acute psychiatric condition can benefit from expression of breastmilk that can be provided to the infant or discarded to facilitate breastfeeding in the future.18 While expression of breastmilk may not be as advantageous for infant health as direct breastfeeding due to the potential changes in breastmilk composition from collecting, storing, and heating, this option can be more protective than formula feeding and facilitate future breastfeeding.19 In these clinical scenarios, it is standard care to provide a hospital-grade breast pump to the patient, much like a continuous positive airway pressure machine is provided to patients with obstructive sleep apnea.20 However, there is often considerable difficulty obtaining proper breastfeeding equipment and a lack of services devoted to perinatal care in general inpatient settings. Barriers to direct breastfeeding and pumping of breastmilk are highlighted in the Table.21

Limitations on breastfeeding on an inpatient unit

The limitations in care and restrictions placed on breastfeeding are more optimally addressed in a mother and baby unit (MBU). MBUs are specialized inpatient psychiatric units designed for mothers experiencing severe perinatal psychiatric difficulties. Unlike general psychiatric units, MBUs allow for joint, full-time admission of mothers and their infants. These units also include multidisciplinary staff who specialize in treating perinatal mental health issues as well as infant care and child development.22 Admission into an MBU is considered best practice for new mothers requiring treatment, particularly in the United Kingdom, Australia, and France, as it is well-recognized that the separation of mother and baby can be psychologically harmful.23 In the UK, most patients admitted to an MBU showed significant improvement of their psychiatric symptoms and reported overall high satisfaction with care.24,25 Patients who experience postpartum psychosis prefer MBUs over general psychiatric units because the latter often lack specialized perinatal support, appropriate visitor arrangements, and adequate time with their infant.26-28

Continue to: The resistance to adopting MBUs in the United States...

The resistance to adopting MBUs in the United States has posed significant barriers in care for perinatal patients and has been attributed to financial barriers, medicolegal risk, staffing, and safety concerns.29 Though currently there are no MBUs in the US, other specialized units have been created. A partial day hospitalization program created in 2000 in Rhode Island for mothers and infants revolutionized the psychiatric care experience for new mothers.30 Since then, other institutions have significantly expanded their services to include perinatal psychiatry inpatient units, yet unlike MBUs, these units typically do not provide overnight rooming-in with infants.31 They have the necessary resources and facilities to accommodate the mother’s needs and maximize positive mother-infant interaction, while actively integrating the infant into the mother’s treatment. Breast pumping is treated as a necessary medical procedure and patients can easily access hospital-grade breast pumps with staff supervision. At one such perinatal psychiatric inpatient unit, high rates of treatment satisfaction and significant improvements in symptoms of depression, anxiety, active suicidal ideation, and overall functioning were observed at discharge.32 Therefore, it is crucial to incorporate strategies in general psychiatry units to improve perinatal care, acknowledging that most patients will not have access to these specialized units.21

A framework to approaching the relational ethics decisions

An interdisciplinary team used a relational ethics perspective to carefully analyze the risks and benefits of these complex cases. In Figure 1, we propose a framework for the relational ethics decisions of breastfeeding on general inpatient psychiatric units. In creating this framework, we considered principles of autonomy, beneficence, and nonmaleficence, along with the medical and logistical barriers to breastfeeding.

In Ms. C’s case, the team determined that the risks—which included disrupting the mother’s psychiatric treatment, exposing her to psychological harm due to increasing attachment before remanding the child to CPS custody, and risks to the child due to potential unpredictable agitation driven by the treatment-refractory psychosis of the mother as well as that of other psychiatric patients—outweighed the benefits of breastfeeding. We instead recommended breast pumping as an alternative once Ms. C’s psychiatric stability improved. We presented Ms. C with the option of breast pumping on postpartum Day 5. During a 1-day period in which she showed improved behavioral control, she was counseled on the risks and benefits of breastfeeding and exclusive pumping and was notified that the team would help her with the necessary resources, including consultation with a lactation specialist and breast pump. Despite lactation consultant support, Ms. C had low milk production and difficulty with hand expression, which was very discouraging to her. She produced 1 ounce of milk that was shared with the newborn while in the NICU. Because Ms. C’s psychiatric symptoms continued to be severe, with lability and aggression, and because pumping was triggering distress, the multidisciplinary team determined the best course of care would be to focus on her psychiatric recovery rather than on pumping breastmilk. To reduce milk production and minimize discomfort secondary to breast engorgement, the lactation consultant recommended cold compresses, pain management, and compression of breasts. Ultimately, the mother-infant dyad was unable to reap the benefits of breastfeeding (via pumping or direct breastfeeding) due to the mother’s underlying psychiatric illness, although the staffing, psychosocial support, and logistical limitations contributed to this outcome.33

In Ms. S’s case, the treatment team determined that there were no medical or psychiatric contraindications to breastfeeding, and she was counseled on the risks and benefits of direct breastfeeding and pumping. The treatment team determined it was safe for Ms. S to directly breastfeed as there were no concerns for infant harm postdelivery with constant supervision while on the obstetrics floor. The patient opted to directly breastfeed, which was successful with the guidance of a lactation specialist. When she was transferred to the psychiatric unit on postpartum Day 2, her child was discharged home with the husband. The patient was then encouraged to pump while the psychiatrists monitored her symptoms closely and facilitated increased staff and resources. Transportation of breastmilk was made possible by the family, and on postpartum Day 5, as the patient maintained psychiatric stability, the team discussed with Ms. S and her husband the prospect of direct breastfeeding. The treatment team arranged for separate visitation hours to minimize the possibility of exposing the infant to aggression from other patients on the unit and advocated with hospital leadership to approve of infant visitation on the unit.

Impact of involvement of Child Protective Services

The involvement of CPS also added complexity to Ms. C’s case. Without proper legal guidance, mothers with psychosis who lose custody can find it difficult to navigate the legal system and maintain contact with their children.34 As the prevalence of custody loss in mothers with psychosis is high (approximately 50% according to research published in the last 10 years), effective interventions to reunite the mother and child must be promoted (Figure 2).35-39 Ultimately, the goal of psychiatric hospitalization for perinatal women who have SMI is psychiatric stabilization. The preemptive involvement of psychiatry is crucial because it can allow for early postpartum planning and can provide an opportunity to address feeding options and custody concerns with the patient, social supports and services, and various medical teams. In Ms. C’s case, she visited her baby in the NICU on postpartum Day 2 without consultation with psychiatry or CPS, which posed risks to the patient, infant, and staff. It is vital that various clinicians collaborate with each other and the patient, working towards the goal of optimizing the patient’s mental health to allow for parenting rights in the future and maximizing a sustainable attachment between the parent and child. In Ms. S’s case, the husband was able to facilitate caring for the baby while the mother was hospitalized and played an integral role in the feeding process via pumped breastmilk and transport of the infant for direct breastfeeding.

Continue to: The differences in these 2 cases...

The differences in these 2 cases show the extreme importance of social support to benefit both the mother and child, and the need for more comprehensive social services for women who do not have a social safety net.

Bottom Line

These complex cases highlight an ethical decision-making approach to breastfeeding in perinatal women who have serious mental illness. Collaborative care and shared decision-making, which highlight the interests of the mother and baby, are crucial when assessing the risks and benefits of breastfeeding and pumping breastmilk. Our relational ethics framework can be used to better evaluate and implement breastfeeding options on general psychiatric units.

Related Resources

- Tillman B, Sloan N, Westmoreland P. How COVID-19 affects peripartum women’s mental health. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(6):18-22. doi:10.12788/cp.0129

- Koch J, Preinitz J. Antidepressants for patients who are breastfeeding: what to consider. Current Psychiatry. 2023;22(5):20-23,48. doi:10.12788/cp.0355

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Risperidone • Risperdal

1. Brunner E, Falk DM, Jones M, et al. Olanzapine in pregnancy and breastfeeding: a review of data from global safety surveillance. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol. 2013;14:38. doi:10.1186/2050-6511-14-38

2. Seeman MV. Relational ethics: when mothers suffer from psychosis. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2004;7(3):201-210. doi:10.1007/s00737-004-0054-8

3. Motee A, Jeewon R. Importance of exclusive breastfeeding and complementary feeding among infants. Curr Res Nutr Food Sci. 2014;2(2). doi:10.12944/CRNFSJ.2.2.02

4. Committee Opinion No. 570: breastfeeding in underserved women: increasing initiation and continuation of breastfeeding. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(2 Pt 1):423-427. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000433008.93971.6a

5. Sibolboro Mezzacappa E, Endicott J. Parity mediates the association between infant feeding method and maternal depressive symptoms in the postpartum. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2007;10(6):259-266. doi:10.1007/s00737-007-0207-7

6. Kramer MS, Chalmers B, Hodnett ED, et al. Promotion of Breastfeeding Intervention Trial (PROBIT): a randomized trial in the Republic of Belarus. JAMA. 2001;285(4):413-420. doi:10.1001/jama.285.4.413

7. American Academy of Pediatrics. American Academy of Pediatrics calls for more support for breastfeeding mothers within updated policy recommendations. June 27, 2022. Accessed October 4, 2022. https://www.aap.org/en/news-room/news-releases/aap/2022/american-academy-of-pediatrics-calls-for-more-support-for-breastfeeding-mothers-within-updated-policy-recommendations

8. Hipwell AE, Kumar R. Maternal psychopathology and prediction of outcome based on mother-infant interaction ratings (BMIS). Br J Psychiatry. 1996;169(5):655-661. doi:10.1192/bjp.169.5.655

9. Chandra PS, Bhargavaraman RP, Raghunandan VN, et al. Delusions related to infant and their association with mother-infant interactions in postpartum psychotic disorders. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2006;9(5):285-288. doi:10.1007/s00737-006-0147-7

10. Klinger G, Stahl B, Fusar-Poli P, et al. Antipsychotic drugs and breastfeeding. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev. 2013;10(3):308-317.

11. Uguz F. A new safety scoring system for the use of psychotropic drugs during lactation. Am J Ther. 2021;28(1):e118-e126. doi:10.1097/MJT.0000000000000909

12. Hale TW, Krutsch K. Hale’s Medications & Mothers’ Milk, 2023: A Manual of Lactational Pharmacology. 20th ed. Springer Publishing Company; 2023.

13. Komaroff A. Aripiprazole and lactation failure: the importance of shared decision making. A case report. Case Rep Womens Health. 2021;30:e00308. doi:10.1016/j.crwh.2021.e00308

14. Dennis CL, McQueen K. Does maternal postpartum depressive symptomatology influence infant feeding outcomes? Acta Pediatr. 2007;96(4):590-594. doi:10.1111/j.1651-2227.2007.00184.x

15. Chaput KH, Nettel-Aguirre A, Musto R, et al. Breastfeeding difficulties and supports and risk of postpartum depression in a cohort of women who have given birth in Calgary: a prospective cohort study. CMAJ Open. 2016;4(1):E103-E109. doi:10.9778/cmajo.20150009

16. Dias CC, Figueiredo B. Breastfeeding and depression: a systematic review of the literature. J Affect Disord. 2015;171:142-154. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2014.09.022

17. Brown A, Rance J, Bennett P. Understanding the relationship between breastfeeding and postnatal depression: the role of pain and physical difficulties. J Adv Nurs. 2016;72(2):273-282. doi:10.1111/jan.12832

18. Rosenbaum KA. Exclusive breastmilk pumping: a concept analysis. Nurs Forum. 2022;57(5):946-953. doi:10.1111/nuf.12766

19. Boone KM, Geraghty SR, Keim SA. Feeding at the breast and expressed milk feeding: associations with otitis media and diarrhea in infants. J Pediatr. 2016;174:118-125. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.04.006

20. Epstein LJ, Kristo D, Strollo PJ Jr, et al; Adult Obstructive Sleep Apnea Task Force of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Clinical guideline for the evaluation, management and long-term care of obstructive sleep apnea in adults. J Clin Sleep Med. 2009;5(3):263-276.

21. Caan MP, Sreshta NE, Okwerekwu JA, et al. Clinical and legal considerations regarding breastfeeding on psychiatric units. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2022;50(2):200-207. doi:10.29158/JAAPL.210086-21

22. Glangeaud-Freudenthal NMC, Rainelli C, Cazas O, et al. Inpatient mother and baby psychiatric units (MBUs) and day cares. In: Sutter-Dallay AL, Glangeaud-Freudenthal NC, Guedeney A, et al, eds. Joint Care of Parents and Infants in Perinatal Psychiatry. Springer, Cham; 2016:147-164. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-21557-0_10

23. Dembosky A. A humane approach to caring for new mothers in psychiatric crisis. Health Aff (Millwood). 2021;40(10):1528-1533. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2021.01288

24. Connellan K, Bartholomaeus C, Due C, et al. A systematic review of research on psychiatric mother-baby units. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2017;20(3):373-388. doi:10.1007/s00737-017-0718-9

25. Griffiths J, Lever Taylor B, Morant N, et al. A qualitative comparison of experiences of specialist mother and baby units versus general psychiatric wards. BMC Psychiatry. 2019;19(1):401. doi:10.1186/s12888-019-2389-8

26. Heron J, Gilbert N, Dolman C, et al. Information and support needs during recovery from postpartum psychosis. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2012;15(3):155-165. doi:10.1007/s00737-012-0267-1

27. Robertson E, Lyons A. Living with puerperal psychosis: a qualitative analysis. Psychol Psychother. 2003;76(Pt 4):411-431. doi:10.1348/147608303770584755

28. Mental Welfare Commission for Scotland. Perinatal Themed Visit Report: Keeping Mothers and Babies in Mind. Mental Welfare Commission for Scotland; 2016.

29. Wisner KL, Jennings KD, Conley B. Clinical dilemmas due to the lack of inpatient mother-baby units. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1996;26(4):479-493. doi:10.2190/NFJK-A4V7-CXUU-AM89

30. Battle CL, Howard MM. A mother-baby psychiatric day hospital: history, rationale, and why perinatal mental health is important for obstetric medicine. Obstet Med. 2014;7(2):66-70. doi:10.1177/1753495X13514402

31. Bullard ES, Meltzer-Brody S, Rubinow DR. The need for comprehensive psychiatric perinatal care-the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Department of Psychiatry, Center for Women’s Mood Disorders launches the first dedicated inpatient program in the United States. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;201(5):e10-e11. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2009.05.004

32. Meltzer-Brody S, Brandon AR, Pearson B, et al. Evaluating the clinical effectiveness of a specialized perinatal psychiatry inpatient unit. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2014;17(2):107-113. doi:10.1007/s00737-013-0390-7

33. Alvarez-Toro V. Gender-specific care for women in psychiatric units. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2022;JAAPL.220015-21. doi:10.29158/JAAPL.220015-21

34. Diaz-Caneja A, Johnson S. The views and experiences of severely mentally ill mothers--a qualitative study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2004;39(6):472-482. doi:10.1007/s00127-004-0772-2

35. Gewurtz R, Krupa T, Eastabrook S, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of parenting among people served by assertive community treatment. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2004;28(1):63-65. doi:10.2975/28.2004.63.65

36. Howard LM, Kumar R, Thornicroft G. Psychosocial characteristics and needs of mothers with psychotic disorders. Br J Psychiatry. 2001;178:427-432. doi:10.1192/bjp.178.5.427

37. Hollingsworth LD. Child custody loss among women with persistent severe mental illness. Social Work Research. 2004;28(4):199-209. doi:10.1093/swr/28.4.199

38. Dipple H, Smith S, Andrews H, et al. The experience of motherhood in women with severe and enduring mental illness. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiolf. 2002;37(7):336-340. doi:10.1007/s00127-002-0559-2

39. Seeman MV. Intervention to prevent child custody loss in mothers with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res Treatment. 2012;2012:796763. doi:10.1155/2012/796763

1. Brunner E, Falk DM, Jones M, et al. Olanzapine in pregnancy and breastfeeding: a review of data from global safety surveillance. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol. 2013;14:38. doi:10.1186/2050-6511-14-38

2. Seeman MV. Relational ethics: when mothers suffer from psychosis. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2004;7(3):201-210. doi:10.1007/s00737-004-0054-8

3. Motee A, Jeewon R. Importance of exclusive breastfeeding and complementary feeding among infants. Curr Res Nutr Food Sci. 2014;2(2). doi:10.12944/CRNFSJ.2.2.02

4. Committee Opinion No. 570: breastfeeding in underserved women: increasing initiation and continuation of breastfeeding. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(2 Pt 1):423-427. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000433008.93971.6a

5. Sibolboro Mezzacappa E, Endicott J. Parity mediates the association between infant feeding method and maternal depressive symptoms in the postpartum. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2007;10(6):259-266. doi:10.1007/s00737-007-0207-7

6. Kramer MS, Chalmers B, Hodnett ED, et al. Promotion of Breastfeeding Intervention Trial (PROBIT): a randomized trial in the Republic of Belarus. JAMA. 2001;285(4):413-420. doi:10.1001/jama.285.4.413

7. American Academy of Pediatrics. American Academy of Pediatrics calls for more support for breastfeeding mothers within updated policy recommendations. June 27, 2022. Accessed October 4, 2022. https://www.aap.org/en/news-room/news-releases/aap/2022/american-academy-of-pediatrics-calls-for-more-support-for-breastfeeding-mothers-within-updated-policy-recommendations

8. Hipwell AE, Kumar R. Maternal psychopathology and prediction of outcome based on mother-infant interaction ratings (BMIS). Br J Psychiatry. 1996;169(5):655-661. doi:10.1192/bjp.169.5.655

9. Chandra PS, Bhargavaraman RP, Raghunandan VN, et al. Delusions related to infant and their association with mother-infant interactions in postpartum psychotic disorders. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2006;9(5):285-288. doi:10.1007/s00737-006-0147-7

10. Klinger G, Stahl B, Fusar-Poli P, et al. Antipsychotic drugs and breastfeeding. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev. 2013;10(3):308-317.

11. Uguz F. A new safety scoring system for the use of psychotropic drugs during lactation. Am J Ther. 2021;28(1):e118-e126. doi:10.1097/MJT.0000000000000909

12. Hale TW, Krutsch K. Hale’s Medications & Mothers’ Milk, 2023: A Manual of Lactational Pharmacology. 20th ed. Springer Publishing Company; 2023.

13. Komaroff A. Aripiprazole and lactation failure: the importance of shared decision making. A case report. Case Rep Womens Health. 2021;30:e00308. doi:10.1016/j.crwh.2021.e00308

14. Dennis CL, McQueen K. Does maternal postpartum depressive symptomatology influence infant feeding outcomes? Acta Pediatr. 2007;96(4):590-594. doi:10.1111/j.1651-2227.2007.00184.x

15. Chaput KH, Nettel-Aguirre A, Musto R, et al. Breastfeeding difficulties and supports and risk of postpartum depression in a cohort of women who have given birth in Calgary: a prospective cohort study. CMAJ Open. 2016;4(1):E103-E109. doi:10.9778/cmajo.20150009

16. Dias CC, Figueiredo B. Breastfeeding and depression: a systematic review of the literature. J Affect Disord. 2015;171:142-154. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2014.09.022

17. Brown A, Rance J, Bennett P. Understanding the relationship between breastfeeding and postnatal depression: the role of pain and physical difficulties. J Adv Nurs. 2016;72(2):273-282. doi:10.1111/jan.12832

18. Rosenbaum KA. Exclusive breastmilk pumping: a concept analysis. Nurs Forum. 2022;57(5):946-953. doi:10.1111/nuf.12766

19. Boone KM, Geraghty SR, Keim SA. Feeding at the breast and expressed milk feeding: associations with otitis media and diarrhea in infants. J Pediatr. 2016;174:118-125. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.04.006

20. Epstein LJ, Kristo D, Strollo PJ Jr, et al; Adult Obstructive Sleep Apnea Task Force of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Clinical guideline for the evaluation, management and long-term care of obstructive sleep apnea in adults. J Clin Sleep Med. 2009;5(3):263-276.

21. Caan MP, Sreshta NE, Okwerekwu JA, et al. Clinical and legal considerations regarding breastfeeding on psychiatric units. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2022;50(2):200-207. doi:10.29158/JAAPL.210086-21

22. Glangeaud-Freudenthal NMC, Rainelli C, Cazas O, et al. Inpatient mother and baby psychiatric units (MBUs) and day cares. In: Sutter-Dallay AL, Glangeaud-Freudenthal NC, Guedeney A, et al, eds. Joint Care of Parents and Infants in Perinatal Psychiatry. Springer, Cham; 2016:147-164. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-21557-0_10

23. Dembosky A. A humane approach to caring for new mothers in psychiatric crisis. Health Aff (Millwood). 2021;40(10):1528-1533. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2021.01288

24. Connellan K, Bartholomaeus C, Due C, et al. A systematic review of research on psychiatric mother-baby units. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2017;20(3):373-388. doi:10.1007/s00737-017-0718-9