User login

Medical Communities Go Virtual

Throughout history, physicians have formed communities to aid in the dissemination of knowledge, skills, and professional norms. From local physician groups to international societies and conferences, this drive to connect with members of our profession across the globe is timeless. We do so to learn from each other and continue to move the field of medicine forward.

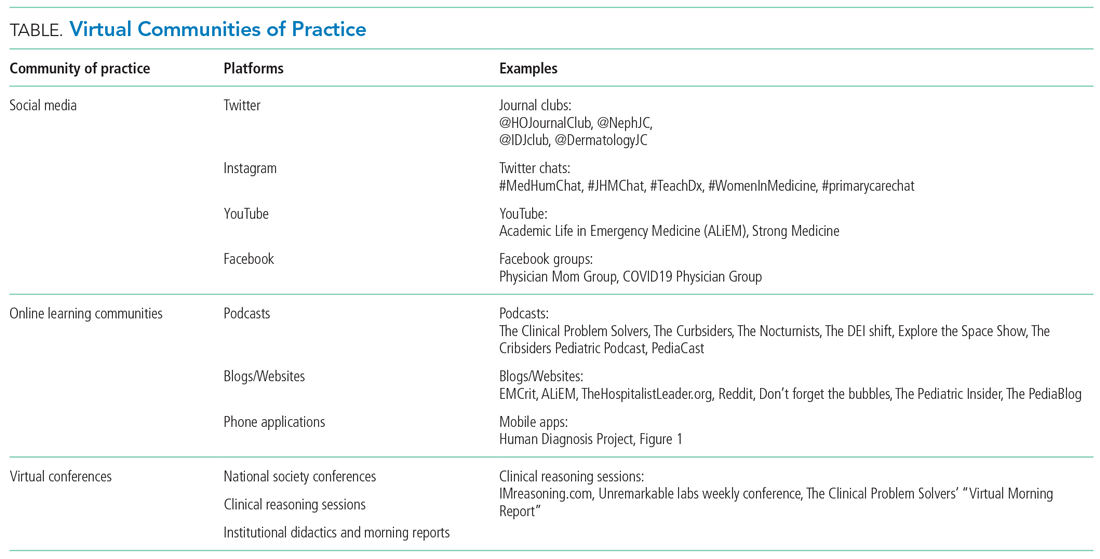

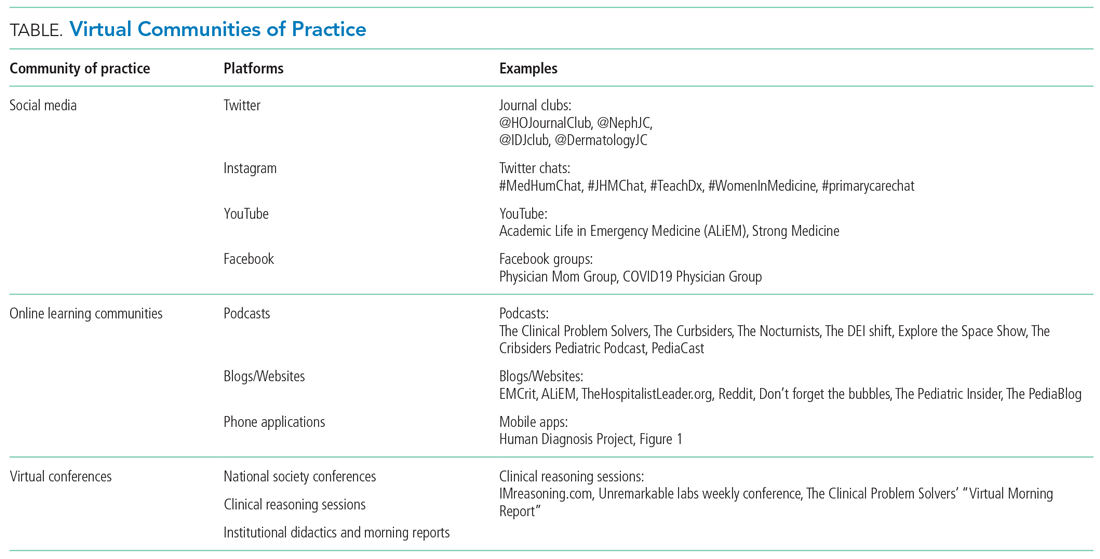

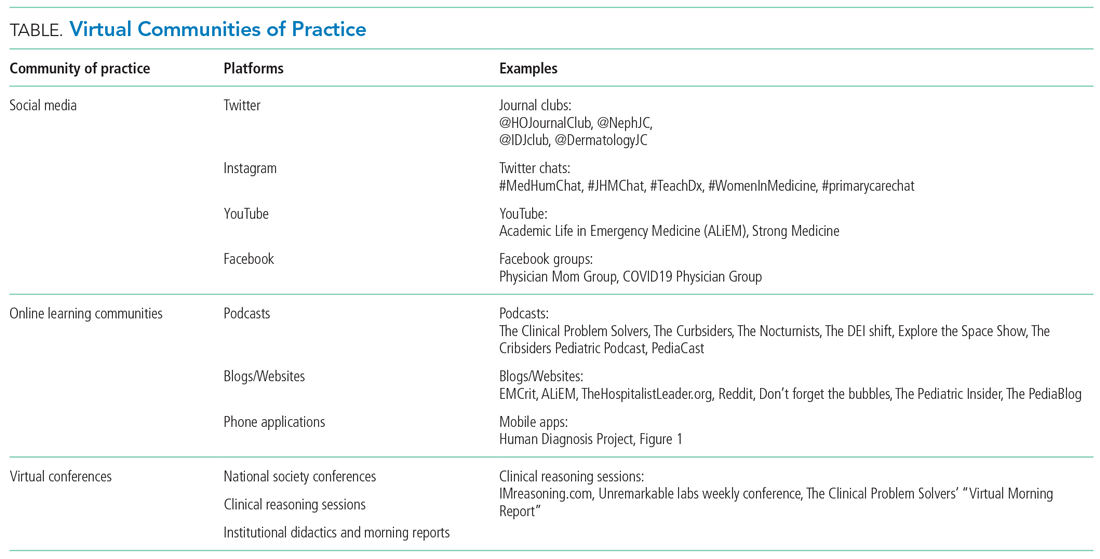

Yet, these communities are being strained by necessary physical distancing required during the COVID-19 pandemic. Many physicians accustomed to a sense of community are now finding themselves surprisingly isolated and alone. Into this distanced landscape, however, new digital groups—specifically social media (SoMe), online learning communities, and virtual conferences—have emerged. We are all active members in virtual communities; all of the authors are team members of The Clinical Problem Solvers podcast and one author of this paper, A.P., has previously served as the medical education lead for the Human Diagnosis Project. Both entities are described later in this article. Here, we provide an overview of these virtual communities and discuss how they have the potential to more equitably and effectively disseminate medical knowledge and education both during and after the COVID-19 pandemic (Table).

SOCIAL MEDIA

Even prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, SoMe—especially Twitter—had become a virtual gathering place where digital colleagues exchange Twitter handles like business cards.1,2 They celebrate each other’s achievements and provide support during difficult times.

Importantly, the format of Twitter tends toward a flattened hierarchy. It is this egalitarian nature that has served SoMe well in its position as a modern learning community. Users from across the experience spectrum engage with and create novel educational content. This often occurs in the form of Tweetorials, or short lessons conveyed over a series of linked tweets. These have gained immense popularity on the platform and are becoming increasingly recognized forms of scholarship.3 Further, case-based lessons have become ubiquitous and are valuable opportunities for users to learn from other members of their digital communities. During the current pandemic, SoMe has become extremely important in the early dissemination and critique of the slew of research on the COVID-19 crisis.4

Beyond its role as an educational platform, SoMe functions as a virtual gathering place for members of the medical community to discuss topics relevant to the field. Subspecialists and researchers have gathered in digital journal clubs (eg, #NephJC, #IDJClub, #BloodandBone) and a number of journals have hosted live Twitter chats covering topics like controversies in clinical practice or professional development (eg, #JHMChat). More recently, social issues affecting the medical field, such as gender equity and the growing antiracism movement, have led to robust discussion on this medium.

Beyond Twitter, many medical professionals gather and exchange ideas on other platforms. Virtual networking and educational groups have arisen using Slack and Facebook.5-7 Trainees and faculty members alike consume and produce content on YouTube, which often serve to teach technical skills.8 Given widespread use of SoMe, we anticipate that the range of platforms utilized by medical professionals will continue to expand in the future.

ONLINE LEARNING COMMUNITIES

There have long existed multiple print and online forums dedicated to the development of clinical skills. These include clinical challenges in medical journals, interactive online cases, and more formal diagnostic education curricula at academic centers.9-11 With the COVID-19 pandemic, it has become more difficult to ensure that trainees have an in-person learning community to discuss and receive feedback. This has led to a wider adoption of application-based clinical exercises, educational podcasts, and curricular innovations to support these virtual efforts.

The Human Diagnosis Project (Human Dx) is a smart-phone application that provides a platform for individuals to submit clinical cases that can be rapidly peer-reviewed and disseminated to the larger user pool. Human Dx is notable for fostering a strong sense of community amongst its users.12,13 Case consumers and case creators are able to engage in further discussion after solving a case, and opportunities for feedback and growth are ample.

Medical education podcasts have taken on greater importance during the pandemic.14,15 Many educators have begun referring their learners towards certain podcasts as in-person learning communities have been put on hold. Medical professionals may appreciate the up-to-date and candid conversations held on many podcasts, which can provide both educationally useful and emotionally sympathetic connections to their distanced peers. Similarly, while academic clinicians previously benefitted from invited grand rounds speakers, they may now find that such expert discussants are most easily accessible through their appearances on podcasts.

As institutions suspended clerkships during the pandemic, many created virtual communities for trainees to engage in diagnostic reasoning and education. They built novel curricula that meld asynchronous learning with online community-based learning.14 Gamified learning tools and quizzes have also been incorporated into these hybrid curricula to help ensure participation of learners within their virtual communities.16,17

VIRTUAL CONFERENCES

Perhaps the most notable advance in digital communities catalyzed by the COVID-19 pandemic has been the increasing reliance on and comfort with video-based software. While many of our clinical, administrative, and social activities have migrated toward these virtual environments, they have also been used for a variety of activities related to education and professional development.

As institutions struggled to adapt to physical distancing, many medical schools and residency programs have moved their regular meetings and conferences to virtual platforms. Similar free and open-access conferences have also emerged, including the “Virtual Morning Report” (VMR) series from The Clinical Problem Solvers podcast, wherein a few individuals are invited to discuss a case on the video conference, with the remainder of the audience contributing via the chat feature.

Beyond the growing popularity of video conferencing for education, these virtual sessions have become their own community. On The Clinical Problem Solvers VMR, many participants, ranging from preclinical students to seasoned attendings, show up on a daily basis and interact with each other as close friends, as do members of more insular institutional sessions (eg, residency run reports). In these strangely isolating times, many of us have experienced comfort in seeing the faces of our friends and colleagues joining us to listen and discuss cases.

Separately, many professional societies have struggled with how to replace their large yearly in-person conferences, which would pose substantial infectious risks were they to be held in person. While many of those scheduled to occur during the early days of the pandemic were canceled or held limited online sessions, the trend towards virtual conference platforms seems to be accelerating. Organizers of the 2020 Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (March 8-11, 2020) decided to convert from an in-person to entirely virtual conference 48 hours before it started. With the benefit of more forewarning, other conferences are planning and exploring best practices to promote networking and advancement of research goals at future academic meetings.18,19

BENEFITS OF VIRTUAL COMMUNITIES

The growing importance of these new digital communities could be viewed as a necessary evolution in the way that we gather and learn from each other. Traditional physician communities were inherently restricted by location, specialty, and hierarchy, thereby limiting the dissemination of knowledge and changes to professional norms. These restrictions could conceivably insulate and promote elite institutions in a fashion that perpetuates the inequalities within global medical systems. Unrestricted and open-access virtual communities, in contrast, have the potential to remove historical barriers and connect first-class mentors with trainees they would never have met otherwise.

Beyond promoting a more equitable distribution of knowledge and resources, these virtual communities are well suited to harness the benefits of group learning. The concept of communities of practice (CoP) refers to groupings of individuals involved in a personal or professional endeavor, with the community facilitating advancement of their own knowledge and skill set. Members of the CoP learn from each other, with more established members passing down essential knowledge and cultural norms. The three main components of CoP are maintaining a social network, a mutual enterprise (eg, a common goal), and a shared repertoire (eg, experiences, languages, etc).

Designing virtual learning spaces with these aspects in mind may allow these communities to function as CoPs. Some strategies include use of chat functions in videoconferences (to promote further dialogue) and development of dedicated sessions for specific subgroups or aims (eg, professional mentorship). The anticipated benefits of integrating virtual CoPs into medical education are notable, as a number of studies have already suggested that they are effective for disseminating knowledge, enhancing social learning, and aiding with professional development.7,20-23 These virtual CoPs continue to evolve, however, and further research is warranted to clarify how best to utilize them in medical education and professional societies.

CONCLUSION

Amidst the tragic loss of lives and financial calamity, the COVID-19 pandemic has also spurred innovation and change in the way health professionals learn and communicate. Going forward, the medical establishment should capitalize on these recent innovations and work to further build, recognize, and foster such digital gathering spaces in order to more equitably and effectively disseminate knowledge and educational resources.

Despite physical distancing, health professionals have grown closer during these past few months. Innovations spurred by the pandemic have made us stronger and more united. Our experience with social media, online learning communities, and virtual conferences suggests the opportunity to grow and evolve from this experience. As Anthony Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, said in March 2020, “...life is not going to be how it used to be [after the pandemic]…” Let’s hope he’s right.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Reza Manesh, MD, Rabih Geha, MD, and Jack Penner, MD, for their careful review of the manuscript.

1. Markham MJ, Gentile D, Graham DL. Social media for networking, professional development, and patient engagement. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2017;37:782-787. https://doi.org/10.1200/EDBK_180077

2. Melvin L, Chan T. Using Twitter in clinical education and practice. J Grad Med Educ. 2014;6(3):581-582. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-14-00342.1

3. Breu AC. Why is a cow? Curiosity, Tweetorials, and the return to why. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(12):1097-1098. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1906790

4. Chan AKM, Nickson CP, Rudolph JW, Lee A, Joynt GM. Social media for rapid knowledge dissemination: early experience from the COVID-19 pandemic. Anaesthesia. 2020:10.1111/anae.15057. https://doi.org/10.1111/anae.15057

5. Pander T, Pinilla S, Dimitriadis K, Fischer MR. The use of Facebook in medical education--a literature review. GMS Z Med Ausbild. 2014;31(3):Doc33. https://doi.org/10.3205/zma000925

6. Cree-Green M, Carreau AM, Davis SM, et al. Peer mentoring for professional and personal growth in academic medicine. J Investig Med. 2020;68(6):1128-1134. https://doi.org/10.1136/jim-2020-001391

7. Yarris LM, Chan TM, Gottlieb M, Juve AM. Finding your people in the digital age: virtual communities of practice to promote education scholarship. J Grad Med Educ. 2019;11(1):1-5. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-18-01093.1

8. Sterling M, Leung P, Wright D, Bishop TF. The use of social media in graduate medical education: a systematic review. Acad Med. 2017;92(7):1043-1056. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001617

9. Manesh R, Dhaliwal G. Digital tools to enhance clinical reasoning. Med Clin North Am. 2018;102(3):559-565. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcna.2017.12.015

10. Subramanian A, Connor DM, Berger G, et al. A curriculum for diagnostic reasoning: JGIM’s exercises in clinical reasoning. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(3):344-345. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-018-4689-y

11. Olson APJ, Singhal G, Dhaliwal G. Diagnosis education - an emerging field. Diagnosis (Berl). 2019;6(2):75-77. https://doi.org/10.1515/dx-2019-0029

12. Chatterjee S, Desai S, Manesh R, Sun J, Nundy S, Wright SM. Assessment of a simulated case-based measurement of physician diagnostic performance. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(1):e187006. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.7006

13. Russell SW, Desai SV, O’Rourke P, et al. The genealogy of teaching clinical reasoning and diagnostic skill: the GEL Study. Diagnosis (Berl). 2020;7(3):197-203. https://doi.org/10.1515/dx-2019-0107

14. Geha R, Dhaliwal G. Pilot virtual clerkship curriculum during the COVID-19 pandemic: podcasts, peers, and problem-solving. Med Educ. 2020;54(9):855-856. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.14246

15. AlGaeed M, Grewal M, Richardson PK, Leon Guerrero CR. COVID-19: Neurology residents’ perspective. J Clin Neurosci. 2020;78:452-453. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocn.2020.05.032

16. Moro C, Stromberga Z. Enhancing variety through gamified, interactive learning experiences. Med Educ. 2020. Online ahead of print. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.14251

17. Morawo A, Sun C, Lowden M. Enhancing engagement during live virtual learning using interactive quizzes. Med Educ. 2020. Online ahead of print. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.14253

18. Rubinger L, Gazendam A, Ekhtiari S, et al. Maximizing virtual meetings and conferences: a review of best practices. Int Orthop. 2020;44(8):1461-1466. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-020-04615-9

19. Woolston C. Learning to love virtual conferences in the coronavirus era. Nature. 2020;582(7810):135-136. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-01489-0

20. Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Steinert Y. Medicine as a community of practice: implications for medical education. Acad Med. 2018;93(2):185-191. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001826

21. McLoughlin C, Patel KD, O’Callaghan T, Reeves S. The use of virtual communities of practice to improve interprofessional collaboration and education: findings from an integrated review. J Interprof Care. 2018;32(2):136-142. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2017.1377692

22. Barnett S, Jones SC, Caton T, Iverson D, Bennett S, Robinson L. Implementing a virtual community of practice for family physician training: a mixed-methods case study. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16(3):e83. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.3083

23. Healy MG, Traeger LN, Axelsson CGS, et al. NEJM Knowledge+ Question of the Week: a novel virtual learning community effectively utilizing an online discussion forum. Med Teach. 2019;41(11):1270-1276. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2019.1635685

Throughout history, physicians have formed communities to aid in the dissemination of knowledge, skills, and professional norms. From local physician groups to international societies and conferences, this drive to connect with members of our profession across the globe is timeless. We do so to learn from each other and continue to move the field of medicine forward.

Yet, these communities are being strained by necessary physical distancing required during the COVID-19 pandemic. Many physicians accustomed to a sense of community are now finding themselves surprisingly isolated and alone. Into this distanced landscape, however, new digital groups—specifically social media (SoMe), online learning communities, and virtual conferences—have emerged. We are all active members in virtual communities; all of the authors are team members of The Clinical Problem Solvers podcast and one author of this paper, A.P., has previously served as the medical education lead for the Human Diagnosis Project. Both entities are described later in this article. Here, we provide an overview of these virtual communities and discuss how they have the potential to more equitably and effectively disseminate medical knowledge and education both during and after the COVID-19 pandemic (Table).

SOCIAL MEDIA

Even prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, SoMe—especially Twitter—had become a virtual gathering place where digital colleagues exchange Twitter handles like business cards.1,2 They celebrate each other’s achievements and provide support during difficult times.

Importantly, the format of Twitter tends toward a flattened hierarchy. It is this egalitarian nature that has served SoMe well in its position as a modern learning community. Users from across the experience spectrum engage with and create novel educational content. This often occurs in the form of Tweetorials, or short lessons conveyed over a series of linked tweets. These have gained immense popularity on the platform and are becoming increasingly recognized forms of scholarship.3 Further, case-based lessons have become ubiquitous and are valuable opportunities for users to learn from other members of their digital communities. During the current pandemic, SoMe has become extremely important in the early dissemination and critique of the slew of research on the COVID-19 crisis.4

Beyond its role as an educational platform, SoMe functions as a virtual gathering place for members of the medical community to discuss topics relevant to the field. Subspecialists and researchers have gathered in digital journal clubs (eg, #NephJC, #IDJClub, #BloodandBone) and a number of journals have hosted live Twitter chats covering topics like controversies in clinical practice or professional development (eg, #JHMChat). More recently, social issues affecting the medical field, such as gender equity and the growing antiracism movement, have led to robust discussion on this medium.

Beyond Twitter, many medical professionals gather and exchange ideas on other platforms. Virtual networking and educational groups have arisen using Slack and Facebook.5-7 Trainees and faculty members alike consume and produce content on YouTube, which often serve to teach technical skills.8 Given widespread use of SoMe, we anticipate that the range of platforms utilized by medical professionals will continue to expand in the future.

ONLINE LEARNING COMMUNITIES

There have long existed multiple print and online forums dedicated to the development of clinical skills. These include clinical challenges in medical journals, interactive online cases, and more formal diagnostic education curricula at academic centers.9-11 With the COVID-19 pandemic, it has become more difficult to ensure that trainees have an in-person learning community to discuss and receive feedback. This has led to a wider adoption of application-based clinical exercises, educational podcasts, and curricular innovations to support these virtual efforts.

The Human Diagnosis Project (Human Dx) is a smart-phone application that provides a platform for individuals to submit clinical cases that can be rapidly peer-reviewed and disseminated to the larger user pool. Human Dx is notable for fostering a strong sense of community amongst its users.12,13 Case consumers and case creators are able to engage in further discussion after solving a case, and opportunities for feedback and growth are ample.

Medical education podcasts have taken on greater importance during the pandemic.14,15 Many educators have begun referring their learners towards certain podcasts as in-person learning communities have been put on hold. Medical professionals may appreciate the up-to-date and candid conversations held on many podcasts, which can provide both educationally useful and emotionally sympathetic connections to their distanced peers. Similarly, while academic clinicians previously benefitted from invited grand rounds speakers, they may now find that such expert discussants are most easily accessible through their appearances on podcasts.

As institutions suspended clerkships during the pandemic, many created virtual communities for trainees to engage in diagnostic reasoning and education. They built novel curricula that meld asynchronous learning with online community-based learning.14 Gamified learning tools and quizzes have also been incorporated into these hybrid curricula to help ensure participation of learners within their virtual communities.16,17

VIRTUAL CONFERENCES

Perhaps the most notable advance in digital communities catalyzed by the COVID-19 pandemic has been the increasing reliance on and comfort with video-based software. While many of our clinical, administrative, and social activities have migrated toward these virtual environments, they have also been used for a variety of activities related to education and professional development.

As institutions struggled to adapt to physical distancing, many medical schools and residency programs have moved their regular meetings and conferences to virtual platforms. Similar free and open-access conferences have also emerged, including the “Virtual Morning Report” (VMR) series from The Clinical Problem Solvers podcast, wherein a few individuals are invited to discuss a case on the video conference, with the remainder of the audience contributing via the chat feature.

Beyond the growing popularity of video conferencing for education, these virtual sessions have become their own community. On The Clinical Problem Solvers VMR, many participants, ranging from preclinical students to seasoned attendings, show up on a daily basis and interact with each other as close friends, as do members of more insular institutional sessions (eg, residency run reports). In these strangely isolating times, many of us have experienced comfort in seeing the faces of our friends and colleagues joining us to listen and discuss cases.

Separately, many professional societies have struggled with how to replace their large yearly in-person conferences, which would pose substantial infectious risks were they to be held in person. While many of those scheduled to occur during the early days of the pandemic were canceled or held limited online sessions, the trend towards virtual conference platforms seems to be accelerating. Organizers of the 2020 Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (March 8-11, 2020) decided to convert from an in-person to entirely virtual conference 48 hours before it started. With the benefit of more forewarning, other conferences are planning and exploring best practices to promote networking and advancement of research goals at future academic meetings.18,19

BENEFITS OF VIRTUAL COMMUNITIES

The growing importance of these new digital communities could be viewed as a necessary evolution in the way that we gather and learn from each other. Traditional physician communities were inherently restricted by location, specialty, and hierarchy, thereby limiting the dissemination of knowledge and changes to professional norms. These restrictions could conceivably insulate and promote elite institutions in a fashion that perpetuates the inequalities within global medical systems. Unrestricted and open-access virtual communities, in contrast, have the potential to remove historical barriers and connect first-class mentors with trainees they would never have met otherwise.

Beyond promoting a more equitable distribution of knowledge and resources, these virtual communities are well suited to harness the benefits of group learning. The concept of communities of practice (CoP) refers to groupings of individuals involved in a personal or professional endeavor, with the community facilitating advancement of their own knowledge and skill set. Members of the CoP learn from each other, with more established members passing down essential knowledge and cultural norms. The three main components of CoP are maintaining a social network, a mutual enterprise (eg, a common goal), and a shared repertoire (eg, experiences, languages, etc).

Designing virtual learning spaces with these aspects in mind may allow these communities to function as CoPs. Some strategies include use of chat functions in videoconferences (to promote further dialogue) and development of dedicated sessions for specific subgroups or aims (eg, professional mentorship). The anticipated benefits of integrating virtual CoPs into medical education are notable, as a number of studies have already suggested that they are effective for disseminating knowledge, enhancing social learning, and aiding with professional development.7,20-23 These virtual CoPs continue to evolve, however, and further research is warranted to clarify how best to utilize them in medical education and professional societies.

CONCLUSION

Amidst the tragic loss of lives and financial calamity, the COVID-19 pandemic has also spurred innovation and change in the way health professionals learn and communicate. Going forward, the medical establishment should capitalize on these recent innovations and work to further build, recognize, and foster such digital gathering spaces in order to more equitably and effectively disseminate knowledge and educational resources.

Despite physical distancing, health professionals have grown closer during these past few months. Innovations spurred by the pandemic have made us stronger and more united. Our experience with social media, online learning communities, and virtual conferences suggests the opportunity to grow and evolve from this experience. As Anthony Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, said in March 2020, “...life is not going to be how it used to be [after the pandemic]…” Let’s hope he’s right.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Reza Manesh, MD, Rabih Geha, MD, and Jack Penner, MD, for their careful review of the manuscript.

Throughout history, physicians have formed communities to aid in the dissemination of knowledge, skills, and professional norms. From local physician groups to international societies and conferences, this drive to connect with members of our profession across the globe is timeless. We do so to learn from each other and continue to move the field of medicine forward.

Yet, these communities are being strained by necessary physical distancing required during the COVID-19 pandemic. Many physicians accustomed to a sense of community are now finding themselves surprisingly isolated and alone. Into this distanced landscape, however, new digital groups—specifically social media (SoMe), online learning communities, and virtual conferences—have emerged. We are all active members in virtual communities; all of the authors are team members of The Clinical Problem Solvers podcast and one author of this paper, A.P., has previously served as the medical education lead for the Human Diagnosis Project. Both entities are described later in this article. Here, we provide an overview of these virtual communities and discuss how they have the potential to more equitably and effectively disseminate medical knowledge and education both during and after the COVID-19 pandemic (Table).

SOCIAL MEDIA

Even prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, SoMe—especially Twitter—had become a virtual gathering place where digital colleagues exchange Twitter handles like business cards.1,2 They celebrate each other’s achievements and provide support during difficult times.

Importantly, the format of Twitter tends toward a flattened hierarchy. It is this egalitarian nature that has served SoMe well in its position as a modern learning community. Users from across the experience spectrum engage with and create novel educational content. This often occurs in the form of Tweetorials, or short lessons conveyed over a series of linked tweets. These have gained immense popularity on the platform and are becoming increasingly recognized forms of scholarship.3 Further, case-based lessons have become ubiquitous and are valuable opportunities for users to learn from other members of their digital communities. During the current pandemic, SoMe has become extremely important in the early dissemination and critique of the slew of research on the COVID-19 crisis.4

Beyond its role as an educational platform, SoMe functions as a virtual gathering place for members of the medical community to discuss topics relevant to the field. Subspecialists and researchers have gathered in digital journal clubs (eg, #NephJC, #IDJClub, #BloodandBone) and a number of journals have hosted live Twitter chats covering topics like controversies in clinical practice or professional development (eg, #JHMChat). More recently, social issues affecting the medical field, such as gender equity and the growing antiracism movement, have led to robust discussion on this medium.

Beyond Twitter, many medical professionals gather and exchange ideas on other platforms. Virtual networking and educational groups have arisen using Slack and Facebook.5-7 Trainees and faculty members alike consume and produce content on YouTube, which often serve to teach technical skills.8 Given widespread use of SoMe, we anticipate that the range of platforms utilized by medical professionals will continue to expand in the future.

ONLINE LEARNING COMMUNITIES

There have long existed multiple print and online forums dedicated to the development of clinical skills. These include clinical challenges in medical journals, interactive online cases, and more formal diagnostic education curricula at academic centers.9-11 With the COVID-19 pandemic, it has become more difficult to ensure that trainees have an in-person learning community to discuss and receive feedback. This has led to a wider adoption of application-based clinical exercises, educational podcasts, and curricular innovations to support these virtual efforts.

The Human Diagnosis Project (Human Dx) is a smart-phone application that provides a platform for individuals to submit clinical cases that can be rapidly peer-reviewed and disseminated to the larger user pool. Human Dx is notable for fostering a strong sense of community amongst its users.12,13 Case consumers and case creators are able to engage in further discussion after solving a case, and opportunities for feedback and growth are ample.

Medical education podcasts have taken on greater importance during the pandemic.14,15 Many educators have begun referring their learners towards certain podcasts as in-person learning communities have been put on hold. Medical professionals may appreciate the up-to-date and candid conversations held on many podcasts, which can provide both educationally useful and emotionally sympathetic connections to their distanced peers. Similarly, while academic clinicians previously benefitted from invited grand rounds speakers, they may now find that such expert discussants are most easily accessible through their appearances on podcasts.

As institutions suspended clerkships during the pandemic, many created virtual communities for trainees to engage in diagnostic reasoning and education. They built novel curricula that meld asynchronous learning with online community-based learning.14 Gamified learning tools and quizzes have also been incorporated into these hybrid curricula to help ensure participation of learners within their virtual communities.16,17

VIRTUAL CONFERENCES

Perhaps the most notable advance in digital communities catalyzed by the COVID-19 pandemic has been the increasing reliance on and comfort with video-based software. While many of our clinical, administrative, and social activities have migrated toward these virtual environments, they have also been used for a variety of activities related to education and professional development.

As institutions struggled to adapt to physical distancing, many medical schools and residency programs have moved their regular meetings and conferences to virtual platforms. Similar free and open-access conferences have also emerged, including the “Virtual Morning Report” (VMR) series from The Clinical Problem Solvers podcast, wherein a few individuals are invited to discuss a case on the video conference, with the remainder of the audience contributing via the chat feature.

Beyond the growing popularity of video conferencing for education, these virtual sessions have become their own community. On The Clinical Problem Solvers VMR, many participants, ranging from preclinical students to seasoned attendings, show up on a daily basis and interact with each other as close friends, as do members of more insular institutional sessions (eg, residency run reports). In these strangely isolating times, many of us have experienced comfort in seeing the faces of our friends and colleagues joining us to listen and discuss cases.

Separately, many professional societies have struggled with how to replace their large yearly in-person conferences, which would pose substantial infectious risks were they to be held in person. While many of those scheduled to occur during the early days of the pandemic were canceled or held limited online sessions, the trend towards virtual conference platforms seems to be accelerating. Organizers of the 2020 Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (March 8-11, 2020) decided to convert from an in-person to entirely virtual conference 48 hours before it started. With the benefit of more forewarning, other conferences are planning and exploring best practices to promote networking and advancement of research goals at future academic meetings.18,19

BENEFITS OF VIRTUAL COMMUNITIES

The growing importance of these new digital communities could be viewed as a necessary evolution in the way that we gather and learn from each other. Traditional physician communities were inherently restricted by location, specialty, and hierarchy, thereby limiting the dissemination of knowledge and changes to professional norms. These restrictions could conceivably insulate and promote elite institutions in a fashion that perpetuates the inequalities within global medical systems. Unrestricted and open-access virtual communities, in contrast, have the potential to remove historical barriers and connect first-class mentors with trainees they would never have met otherwise.

Beyond promoting a more equitable distribution of knowledge and resources, these virtual communities are well suited to harness the benefits of group learning. The concept of communities of practice (CoP) refers to groupings of individuals involved in a personal or professional endeavor, with the community facilitating advancement of their own knowledge and skill set. Members of the CoP learn from each other, with more established members passing down essential knowledge and cultural norms. The three main components of CoP are maintaining a social network, a mutual enterprise (eg, a common goal), and a shared repertoire (eg, experiences, languages, etc).

Designing virtual learning spaces with these aspects in mind may allow these communities to function as CoPs. Some strategies include use of chat functions in videoconferences (to promote further dialogue) and development of dedicated sessions for specific subgroups or aims (eg, professional mentorship). The anticipated benefits of integrating virtual CoPs into medical education are notable, as a number of studies have already suggested that they are effective for disseminating knowledge, enhancing social learning, and aiding with professional development.7,20-23 These virtual CoPs continue to evolve, however, and further research is warranted to clarify how best to utilize them in medical education and professional societies.

CONCLUSION

Amidst the tragic loss of lives and financial calamity, the COVID-19 pandemic has also spurred innovation and change in the way health professionals learn and communicate. Going forward, the medical establishment should capitalize on these recent innovations and work to further build, recognize, and foster such digital gathering spaces in order to more equitably and effectively disseminate knowledge and educational resources.

Despite physical distancing, health professionals have grown closer during these past few months. Innovations spurred by the pandemic have made us stronger and more united. Our experience with social media, online learning communities, and virtual conferences suggests the opportunity to grow and evolve from this experience. As Anthony Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, said in March 2020, “...life is not going to be how it used to be [after the pandemic]…” Let’s hope he’s right.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Reza Manesh, MD, Rabih Geha, MD, and Jack Penner, MD, for their careful review of the manuscript.

1. Markham MJ, Gentile D, Graham DL. Social media for networking, professional development, and patient engagement. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2017;37:782-787. https://doi.org/10.1200/EDBK_180077

2. Melvin L, Chan T. Using Twitter in clinical education and practice. J Grad Med Educ. 2014;6(3):581-582. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-14-00342.1

3. Breu AC. Why is a cow? Curiosity, Tweetorials, and the return to why. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(12):1097-1098. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1906790

4. Chan AKM, Nickson CP, Rudolph JW, Lee A, Joynt GM. Social media for rapid knowledge dissemination: early experience from the COVID-19 pandemic. Anaesthesia. 2020:10.1111/anae.15057. https://doi.org/10.1111/anae.15057

5. Pander T, Pinilla S, Dimitriadis K, Fischer MR. The use of Facebook in medical education--a literature review. GMS Z Med Ausbild. 2014;31(3):Doc33. https://doi.org/10.3205/zma000925

6. Cree-Green M, Carreau AM, Davis SM, et al. Peer mentoring for professional and personal growth in academic medicine. J Investig Med. 2020;68(6):1128-1134. https://doi.org/10.1136/jim-2020-001391

7. Yarris LM, Chan TM, Gottlieb M, Juve AM. Finding your people in the digital age: virtual communities of practice to promote education scholarship. J Grad Med Educ. 2019;11(1):1-5. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-18-01093.1

8. Sterling M, Leung P, Wright D, Bishop TF. The use of social media in graduate medical education: a systematic review. Acad Med. 2017;92(7):1043-1056. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001617

9. Manesh R, Dhaliwal G. Digital tools to enhance clinical reasoning. Med Clin North Am. 2018;102(3):559-565. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcna.2017.12.015

10. Subramanian A, Connor DM, Berger G, et al. A curriculum for diagnostic reasoning: JGIM’s exercises in clinical reasoning. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(3):344-345. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-018-4689-y

11. Olson APJ, Singhal G, Dhaliwal G. Diagnosis education - an emerging field. Diagnosis (Berl). 2019;6(2):75-77. https://doi.org/10.1515/dx-2019-0029

12. Chatterjee S, Desai S, Manesh R, Sun J, Nundy S, Wright SM. Assessment of a simulated case-based measurement of physician diagnostic performance. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(1):e187006. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.7006

13. Russell SW, Desai SV, O’Rourke P, et al. The genealogy of teaching clinical reasoning and diagnostic skill: the GEL Study. Diagnosis (Berl). 2020;7(3):197-203. https://doi.org/10.1515/dx-2019-0107

14. Geha R, Dhaliwal G. Pilot virtual clerkship curriculum during the COVID-19 pandemic: podcasts, peers, and problem-solving. Med Educ. 2020;54(9):855-856. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.14246

15. AlGaeed M, Grewal M, Richardson PK, Leon Guerrero CR. COVID-19: Neurology residents’ perspective. J Clin Neurosci. 2020;78:452-453. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocn.2020.05.032

16. Moro C, Stromberga Z. Enhancing variety through gamified, interactive learning experiences. Med Educ. 2020. Online ahead of print. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.14251

17. Morawo A, Sun C, Lowden M. Enhancing engagement during live virtual learning using interactive quizzes. Med Educ. 2020. Online ahead of print. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.14253

18. Rubinger L, Gazendam A, Ekhtiari S, et al. Maximizing virtual meetings and conferences: a review of best practices. Int Orthop. 2020;44(8):1461-1466. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-020-04615-9

19. Woolston C. Learning to love virtual conferences in the coronavirus era. Nature. 2020;582(7810):135-136. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-01489-0

20. Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Steinert Y. Medicine as a community of practice: implications for medical education. Acad Med. 2018;93(2):185-191. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001826

21. McLoughlin C, Patel KD, O’Callaghan T, Reeves S. The use of virtual communities of practice to improve interprofessional collaboration and education: findings from an integrated review. J Interprof Care. 2018;32(2):136-142. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2017.1377692

22. Barnett S, Jones SC, Caton T, Iverson D, Bennett S, Robinson L. Implementing a virtual community of practice for family physician training: a mixed-methods case study. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16(3):e83. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.3083

23. Healy MG, Traeger LN, Axelsson CGS, et al. NEJM Knowledge+ Question of the Week: a novel virtual learning community effectively utilizing an online discussion forum. Med Teach. 2019;41(11):1270-1276. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2019.1635685

1. Markham MJ, Gentile D, Graham DL. Social media for networking, professional development, and patient engagement. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2017;37:782-787. https://doi.org/10.1200/EDBK_180077

2. Melvin L, Chan T. Using Twitter in clinical education and practice. J Grad Med Educ. 2014;6(3):581-582. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-14-00342.1

3. Breu AC. Why is a cow? Curiosity, Tweetorials, and the return to why. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(12):1097-1098. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1906790

4. Chan AKM, Nickson CP, Rudolph JW, Lee A, Joynt GM. Social media for rapid knowledge dissemination: early experience from the COVID-19 pandemic. Anaesthesia. 2020:10.1111/anae.15057. https://doi.org/10.1111/anae.15057

5. Pander T, Pinilla S, Dimitriadis K, Fischer MR. The use of Facebook in medical education--a literature review. GMS Z Med Ausbild. 2014;31(3):Doc33. https://doi.org/10.3205/zma000925

6. Cree-Green M, Carreau AM, Davis SM, et al. Peer mentoring for professional and personal growth in academic medicine. J Investig Med. 2020;68(6):1128-1134. https://doi.org/10.1136/jim-2020-001391

7. Yarris LM, Chan TM, Gottlieb M, Juve AM. Finding your people in the digital age: virtual communities of practice to promote education scholarship. J Grad Med Educ. 2019;11(1):1-5. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-18-01093.1

8. Sterling M, Leung P, Wright D, Bishop TF. The use of social media in graduate medical education: a systematic review. Acad Med. 2017;92(7):1043-1056. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001617

9. Manesh R, Dhaliwal G. Digital tools to enhance clinical reasoning. Med Clin North Am. 2018;102(3):559-565. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcna.2017.12.015

10. Subramanian A, Connor DM, Berger G, et al. A curriculum for diagnostic reasoning: JGIM’s exercises in clinical reasoning. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(3):344-345. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-018-4689-y

11. Olson APJ, Singhal G, Dhaliwal G. Diagnosis education - an emerging field. Diagnosis (Berl). 2019;6(2):75-77. https://doi.org/10.1515/dx-2019-0029

12. Chatterjee S, Desai S, Manesh R, Sun J, Nundy S, Wright SM. Assessment of a simulated case-based measurement of physician diagnostic performance. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(1):e187006. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.7006

13. Russell SW, Desai SV, O’Rourke P, et al. The genealogy of teaching clinical reasoning and diagnostic skill: the GEL Study. Diagnosis (Berl). 2020;7(3):197-203. https://doi.org/10.1515/dx-2019-0107

14. Geha R, Dhaliwal G. Pilot virtual clerkship curriculum during the COVID-19 pandemic: podcasts, peers, and problem-solving. Med Educ. 2020;54(9):855-856. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.14246

15. AlGaeed M, Grewal M, Richardson PK, Leon Guerrero CR. COVID-19: Neurology residents’ perspective. J Clin Neurosci. 2020;78:452-453. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocn.2020.05.032

16. Moro C, Stromberga Z. Enhancing variety through gamified, interactive learning experiences. Med Educ. 2020. Online ahead of print. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.14251

17. Morawo A, Sun C, Lowden M. Enhancing engagement during live virtual learning using interactive quizzes. Med Educ. 2020. Online ahead of print. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.14253

18. Rubinger L, Gazendam A, Ekhtiari S, et al. Maximizing virtual meetings and conferences: a review of best practices. Int Orthop. 2020;44(8):1461-1466. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-020-04615-9

19. Woolston C. Learning to love virtual conferences in the coronavirus era. Nature. 2020;582(7810):135-136. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-01489-0

20. Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Steinert Y. Medicine as a community of practice: implications for medical education. Acad Med. 2018;93(2):185-191. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001826

21. McLoughlin C, Patel KD, O’Callaghan T, Reeves S. The use of virtual communities of practice to improve interprofessional collaboration and education: findings from an integrated review. J Interprof Care. 2018;32(2):136-142. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2017.1377692

22. Barnett S, Jones SC, Caton T, Iverson D, Bennett S, Robinson L. Implementing a virtual community of practice for family physician training: a mixed-methods case study. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16(3):e83. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.3083

23. Healy MG, Traeger LN, Axelsson CGS, et al. NEJM Knowledge+ Question of the Week: a novel virtual learning community effectively utilizing an online discussion forum. Med Teach. 2019;41(11):1270-1276. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2019.1635685

© 2020 Society of Hospital Medicine