User login

What Are the Indications for a Blood Transfusion?

Case

A 65-year-old man with a history of coronary artery disease (CAD) presents to the ED after a mechanical fall. He was found to have a hip fracture, admitted to orthopedic service, and underwent an uneventful hip repair. His post-operative course was uncomplicated, except for his hemoglobin level of 7.5 g/dL, which had decreased from his pre-operative hemoglobin of 11.2 g/dL. The patient was without cardiac symptoms, was ambulating with assistance, had normal vital signs, and was otherwise having an unremarkable recovery. The orthopedic surgeon, who recently heard that you do not have to transfuse patients unless their hemoglobin is less than 7 g/dL, consulted the hospitalist to help make the decision. What would your recommendation be?

Overview

Blood transfusions are a common medical procedure routinely given in the hospital.1 An estimated 15 million red blood cell (RBC) units are transfused each year in the United States.2 Despite its common use, the clinical indications for transfusion continue to be the subject of considerable debate. Most clinicians would agree that treating a patient with a low hemoglobin level and symptoms of anemia is reasonable.1,3 However, in the absence of overt symptoms, there is debate about when transfusions are appropriate.2,3

Because tissue oxygen delivery is dependent on hemoglobin and cardiac output, past medical practice has supported the use of the “golden 10/30 rule,” by which patients are transfused to a hemoglobin concentration of 10 g/dL or a hematocrit of 30%, regardless of symptoms. The rationale for this approach is based on physiologic evidence that cardiac output increases when hemoglobin falls below 7 g/dl. In patients with cardiac disease, the ability to increase cardiac output is compromised. Therefore, in order to reduce strain on the heart, hemoglobin levels historically have been kept higher than this threshold.

However, several studies have forced us to re-evaluate this old paradigm, including increasing concern for the infectious and noninfectious complications associated with blood transfusions and the need for cost containment (see Table 1).1,2,4 Due to improved blood screening, infectious complications from transfusions have been greatly reduced; noninfectious complications are 1,000 times more likely than infectious ones.

Review of Data

Although a number of studies have been performed on the indications for blood transfusions, many of the trials conducted in the past were too small to substantiate a certain practice. However, three trials with a large number of participants have allowed for a more evidence-based approach to blood transfusions. The studies address different patient populations to help broaden the restrictive transfusion approach to a larger range of patients.

TRICC trial: critically ill patients5. The TRICC trial was the first major study that compared a liberal transfusion strategy (transfuse when Hb <10 g/dL) to a more conservative approach (transfuse when Hb <7 g/dL). In this multicenter, randomized controlled trial, Hébert et al enrolled 418 critically ill patients and found that there was no significant difference in 30-day all-cause mortality between the restrictive-strategy group (18.7%) and the liberal-strategy group (23.3%).

However, in the pre-determined subgroup analysis, patients who were less severely ill (APACHE II scores of <20) had 30-day all-cause mortality of 8.7%, compared with 16.1% in the liberal-strategy group. Interestingly, there were more cardiac complications (pulmonary edema, angina, MI, and cardiac arrest) in the liberal-strategy group (21%) compared with the restrictive-strategy group (13%). Despite this finding, 30-day mortality was not significantly different in patients with clinically significant cardiac disease (primary or secondary diagnosis of cardiac disease [20.5% restrictive versus 22.9% liberal]).

An average of 2.6 units of RBCs per patient were given in the restrictive group, while 5.6 units were given to patients in the liberal group. This reflects a 54% decrease in the number of transfusions used in the conservative group. All the patients in the liberal group received transfusions, while 33% of the restrictive group’s patients received no blood at all.

The results of this trial suggested that there is no clinical advantage in transfusing ICU patients to Hb values above 9 g/dL, even if they have a history of cardiac disease. In fact, it may be harmful to practice a liberal transfusion strategy in critically ill younger patients (<55 years old) and those who are less severely ill (APACHE II <20).5

FOCUS trial: hip surgery and history of cardiac disease6. The FOCUS trial is a recent study that looked at the optimal hemoglobin level at which an RBC transfusion is beneficial for patients undergoing hip surgery. This study enrolled patients aged 50 or older who had a history or risk factors for cardiovascular disease (clinical evidence of cardiovascular disease: h/o ischemic heart disease, EKG evidence of previous MI, h/o CHF/PVD, h/o stroke/TIA, h/o HTN, DM, hyperlipidemia (TC >200/LDL >130), current tobacco use, or Cr>2.0), who were undergoing primary surgical repair of a hip fracture, and who had Hb <10g/dL within three days after surgery.

More than 2,000 patients were assigned randomly to a liberal-strategy group (transfuse to maintain a Hb >10g/dL) or a restrictive strategy group (transfuse to maintain Hg >8g/dl or for symptoms or signs of anemia). These signs/symptoms included chest pain that was possibly cardiac-related, congestive heart failure, tachycardia, and unresponsive hypotension. The primary outcomes were mortality or inability to walk 10 feet without assistance at 60-day follow-up.

The FOCUS trial found no statistically significant difference in mortality rate (7.6% in the liberal group versus 6.6% in the restrictive group) or in the ability to walk at 60 days (35.2% in the liberal group versus 34.7% in the restrictive group). There were no significant differences in the rates of in-hospital acute MI, unstable angina, or death between the two groups.

Patients in the restrictive-strategy group received 65% fewer units of blood than the liberal group, with 59% receiving no blood after surgery compared with 3% of the liberal group. Overall, the liberal group received 1,866 units of blood, compared with 652 units in the restrictive group.

This trial helps support the findings in previous trials, such as TRICC, by showing that a restrictive transfusion strategy using a trigger point of 8 g/dl does not increase mortality or cardiovascular complications and does not decrease functional ability after orthopedic surgery.

TRAC trial: patients after cardiac surgery7. The TRAC trial was a prospective randomized trial in 502 patients undergoing cardiac surgery that assigned 253 patients to the liberal-transfusion-strategy group (Hb >10g/dl) and 249 to the restrictive-strategy group (Hb >8 g/dl). In this study, the primary endpoint of all-cause 30-day mortality occurred in 10% of the liberal group and 11% of the restrictive group. This difference was not significant.

Subanalysis showed that blood transfusion in both groups was an independent risk factor for the occurrence of respiratory, cardiac, renal, and infectious complications, in addition to the composite end point of 30-day mortality—again highlighting the risk involved in of blood transfusions.

These results support the other trial conclusions that a restrictive transfusion strategy of maintaining a hematocrit of 24% (Hb 8 g/dL) is as safe as a more liberal strategy with a hematocrit of 30% (Hb 10 g/dL). It also offers further evidence of the risks of blood transfusions and supports the view that blood transfusions should never be given simply to correct low hemoglobin levels.

Cochrane Review. A recent Cochrane Review that comprised 19 trials with a combined total of 6,264 patients also supported a restrictive-strategy approach.8 In this review, no difference in mortality was established between the restrictive and liberal transfusion groups, with a trend toward decreased hospital mortality in the restrictive-transfusion group. The authors of the study felt that for most patients, blood transfusion is not necessary until hemoglobin levels drop below 7-8 g/dL but emphasized that this criteria should not be generalized to patients with an acute cardiac issue.

Back to the Case

In this case, the patient is doing well post-operatively and has no cardiac symptoms or hypotension. However, based on the new available data from the FOCUS trial, given the patient’s history of CAD, and the threshold of 8 g/dL used in the study, it was recommended that the patient be transfused.

Bottom Line

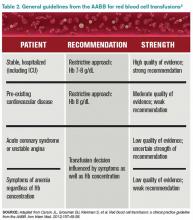

Current practice guidelines clearly support clinical judgment as the primary determinant in the decision to transfuse.2 However, current evidence is growing that our threshold for blood transfusions should be a hemoglobin level of 7-8 g/dl.

Dr. Chang is a hospitalist and assistant professor at Mount Sinai Medical Center in New York City, and is co-director of the medicine-geriatrics clerkship at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. Dr. Torgalkar is a hospitalist and assistant professor at Mount Sinai Medical Center.

References

- Sharma S, Sharma P, Tyler L. Transfusion of blood and blood products: indications and complications. Am Fam Physician. 2011;83:719-724.

- Carson JL, Grossman BJ, Kleinman S, et al. Red blood cell transfusion: a clinical practice guideline from the AABB. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157:49-58.

- Valeri CR, Crowley JP, Loscalzo J. The red cell transfusion trigger: has a sin of commission now become a sin of omission? Transfusion. 1998;38:602-610.

- Klein HG, Spahn DR, Carson JL. Red blood cell transfusion in clinical practice. Lancet. 2007;370(9585):415-426.

- Hébert PC, Wells G, Blajchman MA, et al. A multicenter, randomized, controlled clinical trial of transfusion requirements in critical care. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:409-17.

- Carson JL, Terrin ML, Noveck H, et al. Liberal or restrictive transfusion in high-risk patients after hip surgery. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2453-2462.

- Hajjar LA, Vincent JL, Galas FR, et al. Transfusion requirements after cardiac surgery: the TRACS randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2010;304:1559-1567.

- Carson JL, Carless PA, Hébert PC. Transfusion thresholds and other strategies for guiding allogeneic red blood cell transfusion. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012; 4:CD002042.

Case

A 65-year-old man with a history of coronary artery disease (CAD) presents to the ED after a mechanical fall. He was found to have a hip fracture, admitted to orthopedic service, and underwent an uneventful hip repair. His post-operative course was uncomplicated, except for his hemoglobin level of 7.5 g/dL, which had decreased from his pre-operative hemoglobin of 11.2 g/dL. The patient was without cardiac symptoms, was ambulating with assistance, had normal vital signs, and was otherwise having an unremarkable recovery. The orthopedic surgeon, who recently heard that you do not have to transfuse patients unless their hemoglobin is less than 7 g/dL, consulted the hospitalist to help make the decision. What would your recommendation be?

Overview

Blood transfusions are a common medical procedure routinely given in the hospital.1 An estimated 15 million red blood cell (RBC) units are transfused each year in the United States.2 Despite its common use, the clinical indications for transfusion continue to be the subject of considerable debate. Most clinicians would agree that treating a patient with a low hemoglobin level and symptoms of anemia is reasonable.1,3 However, in the absence of overt symptoms, there is debate about when transfusions are appropriate.2,3

Because tissue oxygen delivery is dependent on hemoglobin and cardiac output, past medical practice has supported the use of the “golden 10/30 rule,” by which patients are transfused to a hemoglobin concentration of 10 g/dL or a hematocrit of 30%, regardless of symptoms. The rationale for this approach is based on physiologic evidence that cardiac output increases when hemoglobin falls below 7 g/dl. In patients with cardiac disease, the ability to increase cardiac output is compromised. Therefore, in order to reduce strain on the heart, hemoglobin levels historically have been kept higher than this threshold.

However, several studies have forced us to re-evaluate this old paradigm, including increasing concern for the infectious and noninfectious complications associated with blood transfusions and the need for cost containment (see Table 1).1,2,4 Due to improved blood screening, infectious complications from transfusions have been greatly reduced; noninfectious complications are 1,000 times more likely than infectious ones.

Review of Data

Although a number of studies have been performed on the indications for blood transfusions, many of the trials conducted in the past were too small to substantiate a certain practice. However, three trials with a large number of participants have allowed for a more evidence-based approach to blood transfusions. The studies address different patient populations to help broaden the restrictive transfusion approach to a larger range of patients.

TRICC trial: critically ill patients5. The TRICC trial was the first major study that compared a liberal transfusion strategy (transfuse when Hb <10 g/dL) to a more conservative approach (transfuse when Hb <7 g/dL). In this multicenter, randomized controlled trial, Hébert et al enrolled 418 critically ill patients and found that there was no significant difference in 30-day all-cause mortality between the restrictive-strategy group (18.7%) and the liberal-strategy group (23.3%).

However, in the pre-determined subgroup analysis, patients who were less severely ill (APACHE II scores of <20) had 30-day all-cause mortality of 8.7%, compared with 16.1% in the liberal-strategy group. Interestingly, there were more cardiac complications (pulmonary edema, angina, MI, and cardiac arrest) in the liberal-strategy group (21%) compared with the restrictive-strategy group (13%). Despite this finding, 30-day mortality was not significantly different in patients with clinically significant cardiac disease (primary or secondary diagnosis of cardiac disease [20.5% restrictive versus 22.9% liberal]).

An average of 2.6 units of RBCs per patient were given in the restrictive group, while 5.6 units were given to patients in the liberal group. This reflects a 54% decrease in the number of transfusions used in the conservative group. All the patients in the liberal group received transfusions, while 33% of the restrictive group’s patients received no blood at all.

The results of this trial suggested that there is no clinical advantage in transfusing ICU patients to Hb values above 9 g/dL, even if they have a history of cardiac disease. In fact, it may be harmful to practice a liberal transfusion strategy in critically ill younger patients (<55 years old) and those who are less severely ill (APACHE II <20).5

FOCUS trial: hip surgery and history of cardiac disease6. The FOCUS trial is a recent study that looked at the optimal hemoglobin level at which an RBC transfusion is beneficial for patients undergoing hip surgery. This study enrolled patients aged 50 or older who had a history or risk factors for cardiovascular disease (clinical evidence of cardiovascular disease: h/o ischemic heart disease, EKG evidence of previous MI, h/o CHF/PVD, h/o stroke/TIA, h/o HTN, DM, hyperlipidemia (TC >200/LDL >130), current tobacco use, or Cr>2.0), who were undergoing primary surgical repair of a hip fracture, and who had Hb <10g/dL within three days after surgery.

More than 2,000 patients were assigned randomly to a liberal-strategy group (transfuse to maintain a Hb >10g/dL) or a restrictive strategy group (transfuse to maintain Hg >8g/dl or for symptoms or signs of anemia). These signs/symptoms included chest pain that was possibly cardiac-related, congestive heart failure, tachycardia, and unresponsive hypotension. The primary outcomes were mortality or inability to walk 10 feet without assistance at 60-day follow-up.

The FOCUS trial found no statistically significant difference in mortality rate (7.6% in the liberal group versus 6.6% in the restrictive group) or in the ability to walk at 60 days (35.2% in the liberal group versus 34.7% in the restrictive group). There were no significant differences in the rates of in-hospital acute MI, unstable angina, or death between the two groups.

Patients in the restrictive-strategy group received 65% fewer units of blood than the liberal group, with 59% receiving no blood after surgery compared with 3% of the liberal group. Overall, the liberal group received 1,866 units of blood, compared with 652 units in the restrictive group.

This trial helps support the findings in previous trials, such as TRICC, by showing that a restrictive transfusion strategy using a trigger point of 8 g/dl does not increase mortality or cardiovascular complications and does not decrease functional ability after orthopedic surgery.

TRAC trial: patients after cardiac surgery7. The TRAC trial was a prospective randomized trial in 502 patients undergoing cardiac surgery that assigned 253 patients to the liberal-transfusion-strategy group (Hb >10g/dl) and 249 to the restrictive-strategy group (Hb >8 g/dl). In this study, the primary endpoint of all-cause 30-day mortality occurred in 10% of the liberal group and 11% of the restrictive group. This difference was not significant.

Subanalysis showed that blood transfusion in both groups was an independent risk factor for the occurrence of respiratory, cardiac, renal, and infectious complications, in addition to the composite end point of 30-day mortality—again highlighting the risk involved in of blood transfusions.

These results support the other trial conclusions that a restrictive transfusion strategy of maintaining a hematocrit of 24% (Hb 8 g/dL) is as safe as a more liberal strategy with a hematocrit of 30% (Hb 10 g/dL). It also offers further evidence of the risks of blood transfusions and supports the view that blood transfusions should never be given simply to correct low hemoglobin levels.

Cochrane Review. A recent Cochrane Review that comprised 19 trials with a combined total of 6,264 patients also supported a restrictive-strategy approach.8 In this review, no difference in mortality was established between the restrictive and liberal transfusion groups, with a trend toward decreased hospital mortality in the restrictive-transfusion group. The authors of the study felt that for most patients, blood transfusion is not necessary until hemoglobin levels drop below 7-8 g/dL but emphasized that this criteria should not be generalized to patients with an acute cardiac issue.

Back to the Case

In this case, the patient is doing well post-operatively and has no cardiac symptoms or hypotension. However, based on the new available data from the FOCUS trial, given the patient’s history of CAD, and the threshold of 8 g/dL used in the study, it was recommended that the patient be transfused.

Bottom Line

Current practice guidelines clearly support clinical judgment as the primary determinant in the decision to transfuse.2 However, current evidence is growing that our threshold for blood transfusions should be a hemoglobin level of 7-8 g/dl.

Dr. Chang is a hospitalist and assistant professor at Mount Sinai Medical Center in New York City, and is co-director of the medicine-geriatrics clerkship at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. Dr. Torgalkar is a hospitalist and assistant professor at Mount Sinai Medical Center.

References

- Sharma S, Sharma P, Tyler L. Transfusion of blood and blood products: indications and complications. Am Fam Physician. 2011;83:719-724.

- Carson JL, Grossman BJ, Kleinman S, et al. Red blood cell transfusion: a clinical practice guideline from the AABB. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157:49-58.

- Valeri CR, Crowley JP, Loscalzo J. The red cell transfusion trigger: has a sin of commission now become a sin of omission? Transfusion. 1998;38:602-610.

- Klein HG, Spahn DR, Carson JL. Red blood cell transfusion in clinical practice. Lancet. 2007;370(9585):415-426.

- Hébert PC, Wells G, Blajchman MA, et al. A multicenter, randomized, controlled clinical trial of transfusion requirements in critical care. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:409-17.

- Carson JL, Terrin ML, Noveck H, et al. Liberal or restrictive transfusion in high-risk patients after hip surgery. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2453-2462.

- Hajjar LA, Vincent JL, Galas FR, et al. Transfusion requirements after cardiac surgery: the TRACS randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2010;304:1559-1567.

- Carson JL, Carless PA, Hébert PC. Transfusion thresholds and other strategies for guiding allogeneic red blood cell transfusion. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012; 4:CD002042.

Case

A 65-year-old man with a history of coronary artery disease (CAD) presents to the ED after a mechanical fall. He was found to have a hip fracture, admitted to orthopedic service, and underwent an uneventful hip repair. His post-operative course was uncomplicated, except for his hemoglobin level of 7.5 g/dL, which had decreased from his pre-operative hemoglobin of 11.2 g/dL. The patient was without cardiac symptoms, was ambulating with assistance, had normal vital signs, and was otherwise having an unremarkable recovery. The orthopedic surgeon, who recently heard that you do not have to transfuse patients unless their hemoglobin is less than 7 g/dL, consulted the hospitalist to help make the decision. What would your recommendation be?

Overview

Blood transfusions are a common medical procedure routinely given in the hospital.1 An estimated 15 million red blood cell (RBC) units are transfused each year in the United States.2 Despite its common use, the clinical indications for transfusion continue to be the subject of considerable debate. Most clinicians would agree that treating a patient with a low hemoglobin level and symptoms of anemia is reasonable.1,3 However, in the absence of overt symptoms, there is debate about when transfusions are appropriate.2,3

Because tissue oxygen delivery is dependent on hemoglobin and cardiac output, past medical practice has supported the use of the “golden 10/30 rule,” by which patients are transfused to a hemoglobin concentration of 10 g/dL or a hematocrit of 30%, regardless of symptoms. The rationale for this approach is based on physiologic evidence that cardiac output increases when hemoglobin falls below 7 g/dl. In patients with cardiac disease, the ability to increase cardiac output is compromised. Therefore, in order to reduce strain on the heart, hemoglobin levels historically have been kept higher than this threshold.

However, several studies have forced us to re-evaluate this old paradigm, including increasing concern for the infectious and noninfectious complications associated with blood transfusions and the need for cost containment (see Table 1).1,2,4 Due to improved blood screening, infectious complications from transfusions have been greatly reduced; noninfectious complications are 1,000 times more likely than infectious ones.

Review of Data

Although a number of studies have been performed on the indications for blood transfusions, many of the trials conducted in the past were too small to substantiate a certain practice. However, three trials with a large number of participants have allowed for a more evidence-based approach to blood transfusions. The studies address different patient populations to help broaden the restrictive transfusion approach to a larger range of patients.

TRICC trial: critically ill patients5. The TRICC trial was the first major study that compared a liberal transfusion strategy (transfuse when Hb <10 g/dL) to a more conservative approach (transfuse when Hb <7 g/dL). In this multicenter, randomized controlled trial, Hébert et al enrolled 418 critically ill patients and found that there was no significant difference in 30-day all-cause mortality between the restrictive-strategy group (18.7%) and the liberal-strategy group (23.3%).

However, in the pre-determined subgroup analysis, patients who were less severely ill (APACHE II scores of <20) had 30-day all-cause mortality of 8.7%, compared with 16.1% in the liberal-strategy group. Interestingly, there were more cardiac complications (pulmonary edema, angina, MI, and cardiac arrest) in the liberal-strategy group (21%) compared with the restrictive-strategy group (13%). Despite this finding, 30-day mortality was not significantly different in patients with clinically significant cardiac disease (primary or secondary diagnosis of cardiac disease [20.5% restrictive versus 22.9% liberal]).

An average of 2.6 units of RBCs per patient were given in the restrictive group, while 5.6 units were given to patients in the liberal group. This reflects a 54% decrease in the number of transfusions used in the conservative group. All the patients in the liberal group received transfusions, while 33% of the restrictive group’s patients received no blood at all.

The results of this trial suggested that there is no clinical advantage in transfusing ICU patients to Hb values above 9 g/dL, even if they have a history of cardiac disease. In fact, it may be harmful to practice a liberal transfusion strategy in critically ill younger patients (<55 years old) and those who are less severely ill (APACHE II <20).5

FOCUS trial: hip surgery and history of cardiac disease6. The FOCUS trial is a recent study that looked at the optimal hemoglobin level at which an RBC transfusion is beneficial for patients undergoing hip surgery. This study enrolled patients aged 50 or older who had a history or risk factors for cardiovascular disease (clinical evidence of cardiovascular disease: h/o ischemic heart disease, EKG evidence of previous MI, h/o CHF/PVD, h/o stroke/TIA, h/o HTN, DM, hyperlipidemia (TC >200/LDL >130), current tobacco use, or Cr>2.0), who were undergoing primary surgical repair of a hip fracture, and who had Hb <10g/dL within three days after surgery.

More than 2,000 patients were assigned randomly to a liberal-strategy group (transfuse to maintain a Hb >10g/dL) or a restrictive strategy group (transfuse to maintain Hg >8g/dl or for symptoms or signs of anemia). These signs/symptoms included chest pain that was possibly cardiac-related, congestive heart failure, tachycardia, and unresponsive hypotension. The primary outcomes were mortality or inability to walk 10 feet without assistance at 60-day follow-up.

The FOCUS trial found no statistically significant difference in mortality rate (7.6% in the liberal group versus 6.6% in the restrictive group) or in the ability to walk at 60 days (35.2% in the liberal group versus 34.7% in the restrictive group). There were no significant differences in the rates of in-hospital acute MI, unstable angina, or death between the two groups.

Patients in the restrictive-strategy group received 65% fewer units of blood than the liberal group, with 59% receiving no blood after surgery compared with 3% of the liberal group. Overall, the liberal group received 1,866 units of blood, compared with 652 units in the restrictive group.

This trial helps support the findings in previous trials, such as TRICC, by showing that a restrictive transfusion strategy using a trigger point of 8 g/dl does not increase mortality or cardiovascular complications and does not decrease functional ability after orthopedic surgery.

TRAC trial: patients after cardiac surgery7. The TRAC trial was a prospective randomized trial in 502 patients undergoing cardiac surgery that assigned 253 patients to the liberal-transfusion-strategy group (Hb >10g/dl) and 249 to the restrictive-strategy group (Hb >8 g/dl). In this study, the primary endpoint of all-cause 30-day mortality occurred in 10% of the liberal group and 11% of the restrictive group. This difference was not significant.

Subanalysis showed that blood transfusion in both groups was an independent risk factor for the occurrence of respiratory, cardiac, renal, and infectious complications, in addition to the composite end point of 30-day mortality—again highlighting the risk involved in of blood transfusions.

These results support the other trial conclusions that a restrictive transfusion strategy of maintaining a hematocrit of 24% (Hb 8 g/dL) is as safe as a more liberal strategy with a hematocrit of 30% (Hb 10 g/dL). It also offers further evidence of the risks of blood transfusions and supports the view that blood transfusions should never be given simply to correct low hemoglobin levels.

Cochrane Review. A recent Cochrane Review that comprised 19 trials with a combined total of 6,264 patients also supported a restrictive-strategy approach.8 In this review, no difference in mortality was established between the restrictive and liberal transfusion groups, with a trend toward decreased hospital mortality in the restrictive-transfusion group. The authors of the study felt that for most patients, blood transfusion is not necessary until hemoglobin levels drop below 7-8 g/dL but emphasized that this criteria should not be generalized to patients with an acute cardiac issue.

Back to the Case

In this case, the patient is doing well post-operatively and has no cardiac symptoms or hypotension. However, based on the new available data from the FOCUS trial, given the patient’s history of CAD, and the threshold of 8 g/dL used in the study, it was recommended that the patient be transfused.

Bottom Line

Current practice guidelines clearly support clinical judgment as the primary determinant in the decision to transfuse.2 However, current evidence is growing that our threshold for blood transfusions should be a hemoglobin level of 7-8 g/dl.

Dr. Chang is a hospitalist and assistant professor at Mount Sinai Medical Center in New York City, and is co-director of the medicine-geriatrics clerkship at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. Dr. Torgalkar is a hospitalist and assistant professor at Mount Sinai Medical Center.

References

- Sharma S, Sharma P, Tyler L. Transfusion of blood and blood products: indications and complications. Am Fam Physician. 2011;83:719-724.

- Carson JL, Grossman BJ, Kleinman S, et al. Red blood cell transfusion: a clinical practice guideline from the AABB. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157:49-58.

- Valeri CR, Crowley JP, Loscalzo J. The red cell transfusion trigger: has a sin of commission now become a sin of omission? Transfusion. 1998;38:602-610.

- Klein HG, Spahn DR, Carson JL. Red blood cell transfusion in clinical practice. Lancet. 2007;370(9585):415-426.

- Hébert PC, Wells G, Blajchman MA, et al. A multicenter, randomized, controlled clinical trial of transfusion requirements in critical care. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:409-17.

- Carson JL, Terrin ML, Noveck H, et al. Liberal or restrictive transfusion in high-risk patients after hip surgery. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2453-2462.

- Hajjar LA, Vincent JL, Galas FR, et al. Transfusion requirements after cardiac surgery: the TRACS randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2010;304:1559-1567.

- Carson JL, Carless PA, Hébert PC. Transfusion thresholds and other strategies for guiding allogeneic red blood cell transfusion. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012; 4:CD002042.