User login

First-line or BiV backup? Conduction system pacing for CRT in heart failure

Pacing as a device therapy for heart failure (HF) is headed for what is probably its next big advance.

After decades of biventricular (BiV) pacemaker success in resynchronizing the ventricles and improving clinical outcomes, relatively new conduction-system pacing (CSP) techniques that avoid the pitfalls of right-ventricular (RV) pacing using BiV lead systems have been supplanting traditional cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) in selected patients at some major centers. In fact, they are solidly ensconced in a new guideline document addressing indications for CSP and BiV pacing in HF.

But , an alternative when BiV pacing isn’t appropriate or can’t be engaged.

That’s mainly because the limited, mostly observational evidence supporting CSP in the document can’t measure up to the clinical experience and plethora of large, randomized trials behind BiV-CRT.

But that shortfall is headed for change. Several new comparative studies, including a small, randomized trial, have added significantly to evidence suggesting that CSP is at least as effective as traditional CRT for procedural, functional safety, and clinical outcomes.

The new studies “are inherently prone to bias, but their results are really good,” observed Juan C. Diaz, MD. They show improvements in left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) and symptoms with CSP that are “outstanding compared to what we have been doing for the last 20 years,” he said in an interview.

Dr. Diaz, Clínica Las Vegas, Medellin, Colombia, is an investigator with the observational SYNCHRONY, which is among the new CSP studies formally presented at the annual scientific sessions of the Heart Rhythm Society. He is also lead author on its same-day publication in JACC: Clinical Electrophysiology.

Dr. Diaz said that CSP, which sustains pacing via the native conduction system, makes more “physiologic sense” than BiV pacing and represents “a step forward” for HF device therapy.

SYNCHRONY compared LBB-area with BiV pacing as the initial strategy for achieving cardiac resynchronization in patients with ischemic or nonischemic cardiomyopathy.

CSP is “a long way” from replacing conventional CRT, he said. But the new studies at the HRS sessions should help extend His-bundle and LBB-area pacing to more patients, he added, given the significant long-term “drawbacks” of BiV pacing. These include inevitable RV pacing, multiple leads, and the risks associated with chronic transvenous leads.

Zachary Goldberger, MD, University of Wisconsin–Madison, went a bit further in support of CSP as invited discussant for the SYNCHRONY presentation.

Given that it improved LVEF, heart failure class, HF hospitalizations (HFH), and mortality in that study and others, Dr. Goldberger said, CSP could potentially “become the dominant mode of resynchronization going forward.”

Other experts at the meeting saw CSP’s potential more as one of several pacing techniques that could be brought to bear for patients with CRT indications.

“Conduction system pacing is going to be a huge complement to biventricular pacing,” to which about 30% of patients have a “less than optimal response,” said Pugazhendhi Vijayaraman, MD, chief of clinical electrophysiology, Geisinger Heart Institute, Danville, Pa.

“I don’t think it needs to replace biventricular pacing, because biventricular pacing is a well-established, incredibly powerful therapy,” he told this news organization. But CSP is likely to provide “a good alternative option” in patients with poor responses to BiV-CRT.

It may, however, render some current BiV-pacing alternatives “obsolete,” Dr. Vijayaraman observed. “At our center, at least for the last 5 years, no patient has needed epicardial surgical left ventricular lead placement” because CSP was a better backup option.

Dr. Vijayaraman presented two of the meeting’s CSP vs. BiV pacing comparisons. In one, the 100-patient randomized HOT-CRT trial, contractile function improved significantly on CSP, which could be either His-bundle or LBB-area pacing.

He also presented an observational study of LBB-area pacing at 15 centers in Asia, Europe, and North America and led the authors of its simultaneous publication in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

“I think left-bundle conduction system pacing is the future, for sure,” Jagmeet P. Singh, MD, DPhil, told this news organization. Still, it doesn’t always work and when it does, it “doesn’t work equally in all patients,” he said.

“Conduction system pacing certainly makes a lot of sense,” especially in patients with left-bundle-branch block (LBBB), and “maybe not as a primary approach but certainly as a secondary approach,” said Dr. Singh, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, who is not a coauthor on any of the three studies.

He acknowledged that CSP may work well as a first-line option in patients with LBBB at some experienced centers. For those without LBBB or who have an intraventricular conduction delay, who represent 45%-50% of current CRT cases, Dr. Singh observed, “there’s still more evidence” that BiV-CRT is a more appropriate initial approach.

Standard CRT may fail, however, even in some patients who otherwise meet guideline-based indications. “We don’t really understand all the mechanisms for nonresponse in conventional biventricular pacing,” observed Niraj Varma, MD, PhD, Cleveland Clinic, also not involved with any of the three studies.

In some groups, including “patients with larger ventricles,” for example, BiV-CRT doesn’t always narrow the electrocardiographic QRS complex or preexcite delayed left ventricular (LV) activation, hallmarks of successful CRT, he said in an interview.

“I think we need to understand why this occurs in both situations,” but in such cases, CSP alone or as an adjunct to direct LV pacing may be successful. “Sometimes we need both an LV lead and the conduction-system pacing lead.”

Narrower, more efficient use of CSP as a BiV-CRT alternative may also boost its chances for success, Dr. Varma added. “I think we need to refine patient selection.”

HOT-CRT: Randomized CSP vs. BiV pacing trial

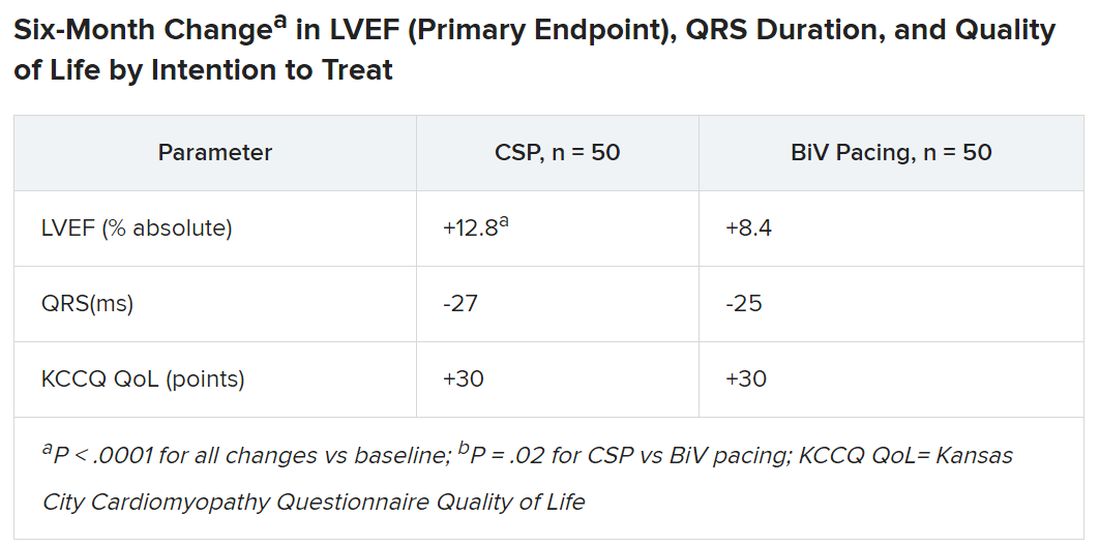

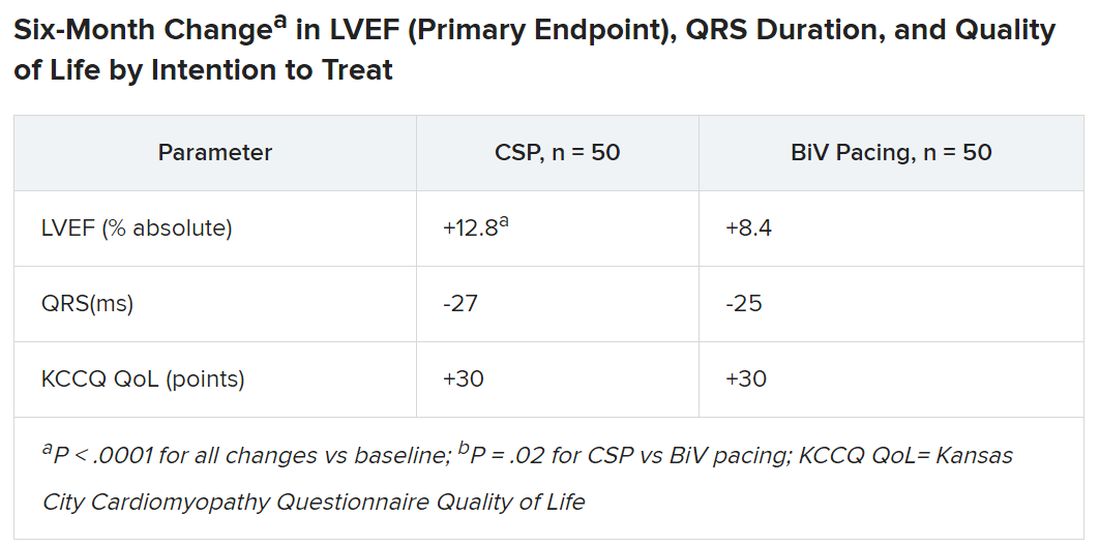

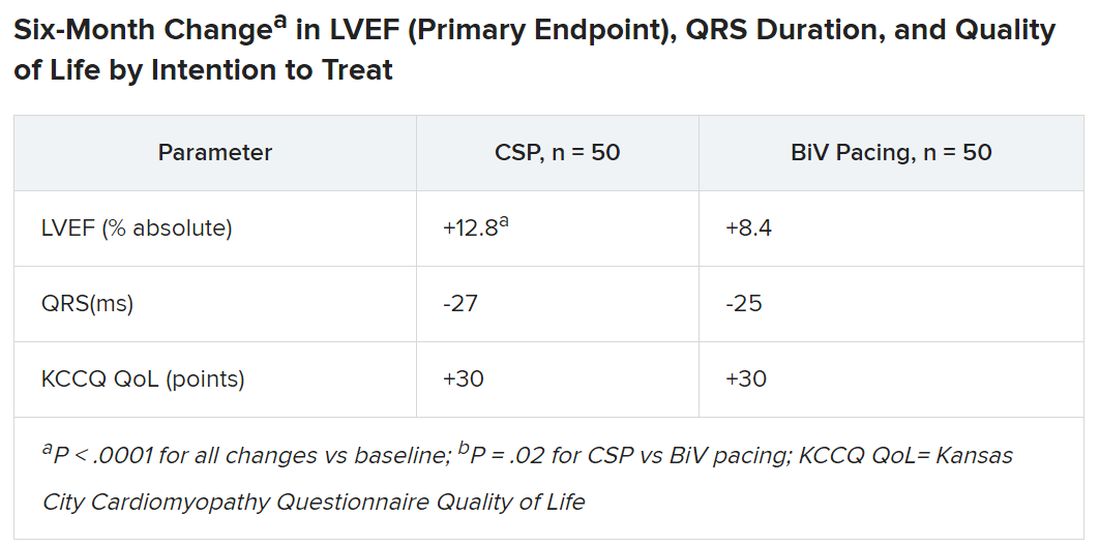

Conducted at three centers in a single health system, the His-optimized cardiac resynchronization therapy study (HOT-CRT) randomly assigned 100 patients with primary or secondary CRT indications to either to CSP – by either His-bundle or LBB-area pacing – or to standard BiV-CRT as the first-line resynchronization method.

Treatment crossovers, allowed for either pacing modality in the event of implantation failure, occurred in two patients and nine patients initially assigned to CSP and BiV pacing, respectively (4% vs. 18%), Dr. Vijayaraman reported.

Historically in trials, BiV pacing has elevated LVEF by about 7%, he said. The mean 12-point increase observed with CSP “is huge, in that sense.” HOT-CRT enrolled a predominantly male and White population at centers highly experienced in both CSP and BiV pacing, limiting its broad relevance to practice, as pointed out by both Dr. Vijayaraman and his presentation’s invited discussant, Yong-Mei Cha, MD, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. Dr. Cha, who is director of cardiac device services at her center, also highlighted the greater rate of crossover from BiV pacing to CSP, 18% vs. 4% in the other direction. “This is a very encouraging result,” because the implant-failure rate for LBB-area pacing may drop once more operators become “familiar and skilled with conduction-system pacing.” Overall, the study supports CSP as “a very good alternative for heart failure patients when BiV pacing fails.”

International comparison of CSP and BiV pacing

In Dr. Vijayaraman’s other study, the observational comparison of LBB-area pacing and BiV-CRT, the CSP technique emerged as a “reasonable alternative to biventricular pacing, not only for improvement in LV function but also to reduce adverse clinical outcomes.”

Indeed, in the international study of 1,778 mostly male patients with primary or secondary CRT indications who received LBB-area or BiV pacing (797 and 981 patients, respectively), those on CSP saw a significant drop in risk for the primary endpoint, death or HFH.

Mean LVEF improved from 27% to 41% in the LBB-area pacing group and 27% to 37% with BiV pacing (P < .001 for both changes) over a follow-up averaging 33 months. The difference in improvement between CSP and BiV pacing was significant at P < .001.

In adjusted analysis, the risk for death or HFH was greater for BiV-pacing patients, a difference driven by HFH events.

- Death or HF: hazard ratio, 1.49 (95% confidence interval, 1.21-1.84; P < .001).

- Death: HR, 1.14 (95% CI, 0.88-1.48; P = .313).

- HFH: HR, 1.49 (95% CI, 1.16-1.92; P = .002)

The analysis has all the “inherent biases” of an observational study. The risk for patient-selection bias, however, was somewhat mitigated by consistent practice patterns at participating centers, Dr. Vijayaraman told this news organization.

For example, he said, operators at six of the institutions were most likely to use CSP as the first-line approach, and the same number of centers usually went with BiV pacing.

SYNCHRONY: First-line LBB-area pacing vs. BiV-CRT

Outcomes using the two approaches were similar in the prospective, international, observational study of 371 patients with ischemic or nonischemic cardiomyopathy and standard CRT indications. Allocation of 128 patients to LBB-area pacing and 243 to BiV-CRT was based on patient and operator preferences, reported Jorge Romero Jr, MD, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, at the HRS sessions.

Risk for the death-HFH primary endpoint dropped 38% for those initially treated with LBB-area pacing, compared with BiV pacing, primarily because of a lower HFH risk:

- Death or HFH: HR, 0.62 (95% CI, 0.41-0.93; P = .02).

- Death: HR, 0.57 (95% CI, 0.25-1.32; P = .19).

- HFH: HR, 0.61 (95% CI, 0.34-0.93; P = .02)

Patients in the CSP group were also more likely to improve by at least one NYHA (New York Heart Association) class (80.4% vs. 67.9%; P < .001), consistent with their greater absolute change in LVEF (8.0 vs. 3.9 points; P < .01).

The findings “suggest that LBBAP [left-bundle branch area pacing] is an excellent alternative to BiV pacing,” with a comparable safety profile, write Jayanthi N. Koneru, MBBS, and Kenneth A. Ellenbogen, MD, in an editorial accompanying the published SYNCHRONY report.

“The differences in improvement of LVEF are encouraging for both groups,” but were superior for LBB-area pacing, continue Dr. Koneru and Dr. Ellenbogen, both with Virginia Commonwealth University Medical Center, Richmond. “Whether these results would have regressed to the mean over a longer period of follow-up or diverge further with LBB-area pacing continuing to be superior is unknown.”

Years for an answer?

A large randomized comparison of CSP and BiV-CRT, called Left vs. Left, is currently in early stages, Sana M. Al-Khatib, MD, MHS, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C., said in a media presentation on two of the presented studies. It has a planned enrollment of more than 2,100 patients on optimal meds with an LVEF of 50% or lower and either a QRS duration of at least 130 ms or an anticipated burden of RV pacing exceeding 40%.

The trial, she said, “will take years to give an answer, but it is actually designed to address the question of whether a composite endpoint of time to death or heart failure hospitalization can be improved with conduction system pacing vs. biventricular pacing.”

Dr. Al-Khatib is a coauthor on the new guideline covering both CSP and BiV-CRT in HF, as are Dr. Cha, Dr. Varma, Dr. Singh, Dr. Vijayaraman, and Dr. Goldberger; Dr. Ellenbogen is one of the reviewers.

Dr. Diaz discloses receiving honoraria or fees for speaking or teaching from Bayer Healthcare, Pfizer, AstraZeneca, Boston Scientific, and Medtronic. Dr. Vijayaraman discloses receiving honoraria or fees for speaking, teaching, or consulting for Abbott, Medtronic, Biotronik, and Boston Scientific; and receiving research grants from Medtronic. Dr. Varma discloses receiving honoraria or fees for speaking or consulting as an independent contractor for Medtronic, Boston Scientific, Biotronik, Impulse Dynamics USA, Cardiologs, Abbott, Pacemate, Implicity, and EP Solutions. Dr. Singh discloses receiving fees for consulting from EBR Systems, Merit Medical Systems, New Century Health, Biotronik, Abbott, Medtronic, MicroPort Scientific, Cardiologs, Sanofi, CVRx, Impulse Dynamics USA, Octagos, Implicity, Orchestra Biomed, Rhythm Management Group, and Biosense Webster; and receiving honoraria or fees for speaking and teaching from Medscape. Dr. Cha had no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Romero discloses receiving research grants from Biosense Webster; and speaking or receiving honoraria or fees for consulting, speaking, or teaching, or serving on a board for Sanofi, Boston Scientific, and AtriCure. Dr. Koneru discloses consulting for Medtronic and receiving honoraria from Abbott. Dr. Ellenbogen discloses consulting or lecturing for or receiving honoraria from Medtronic, Boston Scientific, and Abbott. Dr. Goldberger discloses receiving royalty income from and serving as an independent contractor for Elsevier. Dr. Al-Khatib discloses receiving research grants from Medtronic and Boston Scientific.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Pacing as a device therapy for heart failure (HF) is headed for what is probably its next big advance.

After decades of biventricular (BiV) pacemaker success in resynchronizing the ventricles and improving clinical outcomes, relatively new conduction-system pacing (CSP) techniques that avoid the pitfalls of right-ventricular (RV) pacing using BiV lead systems have been supplanting traditional cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) in selected patients at some major centers. In fact, they are solidly ensconced in a new guideline document addressing indications for CSP and BiV pacing in HF.

But , an alternative when BiV pacing isn’t appropriate or can’t be engaged.

That’s mainly because the limited, mostly observational evidence supporting CSP in the document can’t measure up to the clinical experience and plethora of large, randomized trials behind BiV-CRT.

But that shortfall is headed for change. Several new comparative studies, including a small, randomized trial, have added significantly to evidence suggesting that CSP is at least as effective as traditional CRT for procedural, functional safety, and clinical outcomes.

The new studies “are inherently prone to bias, but their results are really good,” observed Juan C. Diaz, MD. They show improvements in left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) and symptoms with CSP that are “outstanding compared to what we have been doing for the last 20 years,” he said in an interview.

Dr. Diaz, Clínica Las Vegas, Medellin, Colombia, is an investigator with the observational SYNCHRONY, which is among the new CSP studies formally presented at the annual scientific sessions of the Heart Rhythm Society. He is also lead author on its same-day publication in JACC: Clinical Electrophysiology.

Dr. Diaz said that CSP, which sustains pacing via the native conduction system, makes more “physiologic sense” than BiV pacing and represents “a step forward” for HF device therapy.

SYNCHRONY compared LBB-area with BiV pacing as the initial strategy for achieving cardiac resynchronization in patients with ischemic or nonischemic cardiomyopathy.

CSP is “a long way” from replacing conventional CRT, he said. But the new studies at the HRS sessions should help extend His-bundle and LBB-area pacing to more patients, he added, given the significant long-term “drawbacks” of BiV pacing. These include inevitable RV pacing, multiple leads, and the risks associated with chronic transvenous leads.

Zachary Goldberger, MD, University of Wisconsin–Madison, went a bit further in support of CSP as invited discussant for the SYNCHRONY presentation.

Given that it improved LVEF, heart failure class, HF hospitalizations (HFH), and mortality in that study and others, Dr. Goldberger said, CSP could potentially “become the dominant mode of resynchronization going forward.”

Other experts at the meeting saw CSP’s potential more as one of several pacing techniques that could be brought to bear for patients with CRT indications.

“Conduction system pacing is going to be a huge complement to biventricular pacing,” to which about 30% of patients have a “less than optimal response,” said Pugazhendhi Vijayaraman, MD, chief of clinical electrophysiology, Geisinger Heart Institute, Danville, Pa.

“I don’t think it needs to replace biventricular pacing, because biventricular pacing is a well-established, incredibly powerful therapy,” he told this news organization. But CSP is likely to provide “a good alternative option” in patients with poor responses to BiV-CRT.

It may, however, render some current BiV-pacing alternatives “obsolete,” Dr. Vijayaraman observed. “At our center, at least for the last 5 years, no patient has needed epicardial surgical left ventricular lead placement” because CSP was a better backup option.

Dr. Vijayaraman presented two of the meeting’s CSP vs. BiV pacing comparisons. In one, the 100-patient randomized HOT-CRT trial, contractile function improved significantly on CSP, which could be either His-bundle or LBB-area pacing.

He also presented an observational study of LBB-area pacing at 15 centers in Asia, Europe, and North America and led the authors of its simultaneous publication in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

“I think left-bundle conduction system pacing is the future, for sure,” Jagmeet P. Singh, MD, DPhil, told this news organization. Still, it doesn’t always work and when it does, it “doesn’t work equally in all patients,” he said.

“Conduction system pacing certainly makes a lot of sense,” especially in patients with left-bundle-branch block (LBBB), and “maybe not as a primary approach but certainly as a secondary approach,” said Dr. Singh, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, who is not a coauthor on any of the three studies.

He acknowledged that CSP may work well as a first-line option in patients with LBBB at some experienced centers. For those without LBBB or who have an intraventricular conduction delay, who represent 45%-50% of current CRT cases, Dr. Singh observed, “there’s still more evidence” that BiV-CRT is a more appropriate initial approach.

Standard CRT may fail, however, even in some patients who otherwise meet guideline-based indications. “We don’t really understand all the mechanisms for nonresponse in conventional biventricular pacing,” observed Niraj Varma, MD, PhD, Cleveland Clinic, also not involved with any of the three studies.

In some groups, including “patients with larger ventricles,” for example, BiV-CRT doesn’t always narrow the electrocardiographic QRS complex or preexcite delayed left ventricular (LV) activation, hallmarks of successful CRT, he said in an interview.

“I think we need to understand why this occurs in both situations,” but in such cases, CSP alone or as an adjunct to direct LV pacing may be successful. “Sometimes we need both an LV lead and the conduction-system pacing lead.”

Narrower, more efficient use of CSP as a BiV-CRT alternative may also boost its chances for success, Dr. Varma added. “I think we need to refine patient selection.”

HOT-CRT: Randomized CSP vs. BiV pacing trial

Conducted at three centers in a single health system, the His-optimized cardiac resynchronization therapy study (HOT-CRT) randomly assigned 100 patients with primary or secondary CRT indications to either to CSP – by either His-bundle or LBB-area pacing – or to standard BiV-CRT as the first-line resynchronization method.

Treatment crossovers, allowed for either pacing modality in the event of implantation failure, occurred in two patients and nine patients initially assigned to CSP and BiV pacing, respectively (4% vs. 18%), Dr. Vijayaraman reported.

Historically in trials, BiV pacing has elevated LVEF by about 7%, he said. The mean 12-point increase observed with CSP “is huge, in that sense.” HOT-CRT enrolled a predominantly male and White population at centers highly experienced in both CSP and BiV pacing, limiting its broad relevance to practice, as pointed out by both Dr. Vijayaraman and his presentation’s invited discussant, Yong-Mei Cha, MD, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. Dr. Cha, who is director of cardiac device services at her center, also highlighted the greater rate of crossover from BiV pacing to CSP, 18% vs. 4% in the other direction. “This is a very encouraging result,” because the implant-failure rate for LBB-area pacing may drop once more operators become “familiar and skilled with conduction-system pacing.” Overall, the study supports CSP as “a very good alternative for heart failure patients when BiV pacing fails.”

International comparison of CSP and BiV pacing

In Dr. Vijayaraman’s other study, the observational comparison of LBB-area pacing and BiV-CRT, the CSP technique emerged as a “reasonable alternative to biventricular pacing, not only for improvement in LV function but also to reduce adverse clinical outcomes.”

Indeed, in the international study of 1,778 mostly male patients with primary or secondary CRT indications who received LBB-area or BiV pacing (797 and 981 patients, respectively), those on CSP saw a significant drop in risk for the primary endpoint, death or HFH.

Mean LVEF improved from 27% to 41% in the LBB-area pacing group and 27% to 37% with BiV pacing (P < .001 for both changes) over a follow-up averaging 33 months. The difference in improvement between CSP and BiV pacing was significant at P < .001.

In adjusted analysis, the risk for death or HFH was greater for BiV-pacing patients, a difference driven by HFH events.

- Death or HF: hazard ratio, 1.49 (95% confidence interval, 1.21-1.84; P < .001).

- Death: HR, 1.14 (95% CI, 0.88-1.48; P = .313).

- HFH: HR, 1.49 (95% CI, 1.16-1.92; P = .002)

The analysis has all the “inherent biases” of an observational study. The risk for patient-selection bias, however, was somewhat mitigated by consistent practice patterns at participating centers, Dr. Vijayaraman told this news organization.

For example, he said, operators at six of the institutions were most likely to use CSP as the first-line approach, and the same number of centers usually went with BiV pacing.

SYNCHRONY: First-line LBB-area pacing vs. BiV-CRT

Outcomes using the two approaches were similar in the prospective, international, observational study of 371 patients with ischemic or nonischemic cardiomyopathy and standard CRT indications. Allocation of 128 patients to LBB-area pacing and 243 to BiV-CRT was based on patient and operator preferences, reported Jorge Romero Jr, MD, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, at the HRS sessions.

Risk for the death-HFH primary endpoint dropped 38% for those initially treated with LBB-area pacing, compared with BiV pacing, primarily because of a lower HFH risk:

- Death or HFH: HR, 0.62 (95% CI, 0.41-0.93; P = .02).

- Death: HR, 0.57 (95% CI, 0.25-1.32; P = .19).

- HFH: HR, 0.61 (95% CI, 0.34-0.93; P = .02)

Patients in the CSP group were also more likely to improve by at least one NYHA (New York Heart Association) class (80.4% vs. 67.9%; P < .001), consistent with their greater absolute change in LVEF (8.0 vs. 3.9 points; P < .01).

The findings “suggest that LBBAP [left-bundle branch area pacing] is an excellent alternative to BiV pacing,” with a comparable safety profile, write Jayanthi N. Koneru, MBBS, and Kenneth A. Ellenbogen, MD, in an editorial accompanying the published SYNCHRONY report.

“The differences in improvement of LVEF are encouraging for both groups,” but were superior for LBB-area pacing, continue Dr. Koneru and Dr. Ellenbogen, both with Virginia Commonwealth University Medical Center, Richmond. “Whether these results would have regressed to the mean over a longer period of follow-up or diverge further with LBB-area pacing continuing to be superior is unknown.”

Years for an answer?

A large randomized comparison of CSP and BiV-CRT, called Left vs. Left, is currently in early stages, Sana M. Al-Khatib, MD, MHS, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C., said in a media presentation on two of the presented studies. It has a planned enrollment of more than 2,100 patients on optimal meds with an LVEF of 50% or lower and either a QRS duration of at least 130 ms or an anticipated burden of RV pacing exceeding 40%.

The trial, she said, “will take years to give an answer, but it is actually designed to address the question of whether a composite endpoint of time to death or heart failure hospitalization can be improved with conduction system pacing vs. biventricular pacing.”

Dr. Al-Khatib is a coauthor on the new guideline covering both CSP and BiV-CRT in HF, as are Dr. Cha, Dr. Varma, Dr. Singh, Dr. Vijayaraman, and Dr. Goldberger; Dr. Ellenbogen is one of the reviewers.

Dr. Diaz discloses receiving honoraria or fees for speaking or teaching from Bayer Healthcare, Pfizer, AstraZeneca, Boston Scientific, and Medtronic. Dr. Vijayaraman discloses receiving honoraria or fees for speaking, teaching, or consulting for Abbott, Medtronic, Biotronik, and Boston Scientific; and receiving research grants from Medtronic. Dr. Varma discloses receiving honoraria or fees for speaking or consulting as an independent contractor for Medtronic, Boston Scientific, Biotronik, Impulse Dynamics USA, Cardiologs, Abbott, Pacemate, Implicity, and EP Solutions. Dr. Singh discloses receiving fees for consulting from EBR Systems, Merit Medical Systems, New Century Health, Biotronik, Abbott, Medtronic, MicroPort Scientific, Cardiologs, Sanofi, CVRx, Impulse Dynamics USA, Octagos, Implicity, Orchestra Biomed, Rhythm Management Group, and Biosense Webster; and receiving honoraria or fees for speaking and teaching from Medscape. Dr. Cha had no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Romero discloses receiving research grants from Biosense Webster; and speaking or receiving honoraria or fees for consulting, speaking, or teaching, or serving on a board for Sanofi, Boston Scientific, and AtriCure. Dr. Koneru discloses consulting for Medtronic and receiving honoraria from Abbott. Dr. Ellenbogen discloses consulting or lecturing for or receiving honoraria from Medtronic, Boston Scientific, and Abbott. Dr. Goldberger discloses receiving royalty income from and serving as an independent contractor for Elsevier. Dr. Al-Khatib discloses receiving research grants from Medtronic and Boston Scientific.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Pacing as a device therapy for heart failure (HF) is headed for what is probably its next big advance.

After decades of biventricular (BiV) pacemaker success in resynchronizing the ventricles and improving clinical outcomes, relatively new conduction-system pacing (CSP) techniques that avoid the pitfalls of right-ventricular (RV) pacing using BiV lead systems have been supplanting traditional cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) in selected patients at some major centers. In fact, they are solidly ensconced in a new guideline document addressing indications for CSP and BiV pacing in HF.

But , an alternative when BiV pacing isn’t appropriate or can’t be engaged.

That’s mainly because the limited, mostly observational evidence supporting CSP in the document can’t measure up to the clinical experience and plethora of large, randomized trials behind BiV-CRT.

But that shortfall is headed for change. Several new comparative studies, including a small, randomized trial, have added significantly to evidence suggesting that CSP is at least as effective as traditional CRT for procedural, functional safety, and clinical outcomes.

The new studies “are inherently prone to bias, but their results are really good,” observed Juan C. Diaz, MD. They show improvements in left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) and symptoms with CSP that are “outstanding compared to what we have been doing for the last 20 years,” he said in an interview.

Dr. Diaz, Clínica Las Vegas, Medellin, Colombia, is an investigator with the observational SYNCHRONY, which is among the new CSP studies formally presented at the annual scientific sessions of the Heart Rhythm Society. He is also lead author on its same-day publication in JACC: Clinical Electrophysiology.

Dr. Diaz said that CSP, which sustains pacing via the native conduction system, makes more “physiologic sense” than BiV pacing and represents “a step forward” for HF device therapy.

SYNCHRONY compared LBB-area with BiV pacing as the initial strategy for achieving cardiac resynchronization in patients with ischemic or nonischemic cardiomyopathy.

CSP is “a long way” from replacing conventional CRT, he said. But the new studies at the HRS sessions should help extend His-bundle and LBB-area pacing to more patients, he added, given the significant long-term “drawbacks” of BiV pacing. These include inevitable RV pacing, multiple leads, and the risks associated with chronic transvenous leads.

Zachary Goldberger, MD, University of Wisconsin–Madison, went a bit further in support of CSP as invited discussant for the SYNCHRONY presentation.

Given that it improved LVEF, heart failure class, HF hospitalizations (HFH), and mortality in that study and others, Dr. Goldberger said, CSP could potentially “become the dominant mode of resynchronization going forward.”

Other experts at the meeting saw CSP’s potential more as one of several pacing techniques that could be brought to bear for patients with CRT indications.

“Conduction system pacing is going to be a huge complement to biventricular pacing,” to which about 30% of patients have a “less than optimal response,” said Pugazhendhi Vijayaraman, MD, chief of clinical electrophysiology, Geisinger Heart Institute, Danville, Pa.

“I don’t think it needs to replace biventricular pacing, because biventricular pacing is a well-established, incredibly powerful therapy,” he told this news organization. But CSP is likely to provide “a good alternative option” in patients with poor responses to BiV-CRT.

It may, however, render some current BiV-pacing alternatives “obsolete,” Dr. Vijayaraman observed. “At our center, at least for the last 5 years, no patient has needed epicardial surgical left ventricular lead placement” because CSP was a better backup option.

Dr. Vijayaraman presented two of the meeting’s CSP vs. BiV pacing comparisons. In one, the 100-patient randomized HOT-CRT trial, contractile function improved significantly on CSP, which could be either His-bundle or LBB-area pacing.

He also presented an observational study of LBB-area pacing at 15 centers in Asia, Europe, and North America and led the authors of its simultaneous publication in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

“I think left-bundle conduction system pacing is the future, for sure,” Jagmeet P. Singh, MD, DPhil, told this news organization. Still, it doesn’t always work and when it does, it “doesn’t work equally in all patients,” he said.

“Conduction system pacing certainly makes a lot of sense,” especially in patients with left-bundle-branch block (LBBB), and “maybe not as a primary approach but certainly as a secondary approach,” said Dr. Singh, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, who is not a coauthor on any of the three studies.

He acknowledged that CSP may work well as a first-line option in patients with LBBB at some experienced centers. For those without LBBB or who have an intraventricular conduction delay, who represent 45%-50% of current CRT cases, Dr. Singh observed, “there’s still more evidence” that BiV-CRT is a more appropriate initial approach.

Standard CRT may fail, however, even in some patients who otherwise meet guideline-based indications. “We don’t really understand all the mechanisms for nonresponse in conventional biventricular pacing,” observed Niraj Varma, MD, PhD, Cleveland Clinic, also not involved with any of the three studies.

In some groups, including “patients with larger ventricles,” for example, BiV-CRT doesn’t always narrow the electrocardiographic QRS complex or preexcite delayed left ventricular (LV) activation, hallmarks of successful CRT, he said in an interview.

“I think we need to understand why this occurs in both situations,” but in such cases, CSP alone or as an adjunct to direct LV pacing may be successful. “Sometimes we need both an LV lead and the conduction-system pacing lead.”

Narrower, more efficient use of CSP as a BiV-CRT alternative may also boost its chances for success, Dr. Varma added. “I think we need to refine patient selection.”

HOT-CRT: Randomized CSP vs. BiV pacing trial

Conducted at three centers in a single health system, the His-optimized cardiac resynchronization therapy study (HOT-CRT) randomly assigned 100 patients with primary or secondary CRT indications to either to CSP – by either His-bundle or LBB-area pacing – or to standard BiV-CRT as the first-line resynchronization method.

Treatment crossovers, allowed for either pacing modality in the event of implantation failure, occurred in two patients and nine patients initially assigned to CSP and BiV pacing, respectively (4% vs. 18%), Dr. Vijayaraman reported.

Historically in trials, BiV pacing has elevated LVEF by about 7%, he said. The mean 12-point increase observed with CSP “is huge, in that sense.” HOT-CRT enrolled a predominantly male and White population at centers highly experienced in both CSP and BiV pacing, limiting its broad relevance to practice, as pointed out by both Dr. Vijayaraman and his presentation’s invited discussant, Yong-Mei Cha, MD, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. Dr. Cha, who is director of cardiac device services at her center, also highlighted the greater rate of crossover from BiV pacing to CSP, 18% vs. 4% in the other direction. “This is a very encouraging result,” because the implant-failure rate for LBB-area pacing may drop once more operators become “familiar and skilled with conduction-system pacing.” Overall, the study supports CSP as “a very good alternative for heart failure patients when BiV pacing fails.”

International comparison of CSP and BiV pacing

In Dr. Vijayaraman’s other study, the observational comparison of LBB-area pacing and BiV-CRT, the CSP technique emerged as a “reasonable alternative to biventricular pacing, not only for improvement in LV function but also to reduce adverse clinical outcomes.”

Indeed, in the international study of 1,778 mostly male patients with primary or secondary CRT indications who received LBB-area or BiV pacing (797 and 981 patients, respectively), those on CSP saw a significant drop in risk for the primary endpoint, death or HFH.

Mean LVEF improved from 27% to 41% in the LBB-area pacing group and 27% to 37% with BiV pacing (P < .001 for both changes) over a follow-up averaging 33 months. The difference in improvement between CSP and BiV pacing was significant at P < .001.

In adjusted analysis, the risk for death or HFH was greater for BiV-pacing patients, a difference driven by HFH events.

- Death or HF: hazard ratio, 1.49 (95% confidence interval, 1.21-1.84; P < .001).

- Death: HR, 1.14 (95% CI, 0.88-1.48; P = .313).

- HFH: HR, 1.49 (95% CI, 1.16-1.92; P = .002)

The analysis has all the “inherent biases” of an observational study. The risk for patient-selection bias, however, was somewhat mitigated by consistent practice patterns at participating centers, Dr. Vijayaraman told this news organization.

For example, he said, operators at six of the institutions were most likely to use CSP as the first-line approach, and the same number of centers usually went with BiV pacing.

SYNCHRONY: First-line LBB-area pacing vs. BiV-CRT

Outcomes using the two approaches were similar in the prospective, international, observational study of 371 patients with ischemic or nonischemic cardiomyopathy and standard CRT indications. Allocation of 128 patients to LBB-area pacing and 243 to BiV-CRT was based on patient and operator preferences, reported Jorge Romero Jr, MD, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, at the HRS sessions.

Risk for the death-HFH primary endpoint dropped 38% for those initially treated with LBB-area pacing, compared with BiV pacing, primarily because of a lower HFH risk:

- Death or HFH: HR, 0.62 (95% CI, 0.41-0.93; P = .02).

- Death: HR, 0.57 (95% CI, 0.25-1.32; P = .19).

- HFH: HR, 0.61 (95% CI, 0.34-0.93; P = .02)

Patients in the CSP group were also more likely to improve by at least one NYHA (New York Heart Association) class (80.4% vs. 67.9%; P < .001), consistent with their greater absolute change in LVEF (8.0 vs. 3.9 points; P < .01).

The findings “suggest that LBBAP [left-bundle branch area pacing] is an excellent alternative to BiV pacing,” with a comparable safety profile, write Jayanthi N. Koneru, MBBS, and Kenneth A. Ellenbogen, MD, in an editorial accompanying the published SYNCHRONY report.

“The differences in improvement of LVEF are encouraging for both groups,” but were superior for LBB-area pacing, continue Dr. Koneru and Dr. Ellenbogen, both with Virginia Commonwealth University Medical Center, Richmond. “Whether these results would have regressed to the mean over a longer period of follow-up or diverge further with LBB-area pacing continuing to be superior is unknown.”

Years for an answer?

A large randomized comparison of CSP and BiV-CRT, called Left vs. Left, is currently in early stages, Sana M. Al-Khatib, MD, MHS, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C., said in a media presentation on two of the presented studies. It has a planned enrollment of more than 2,100 patients on optimal meds with an LVEF of 50% or lower and either a QRS duration of at least 130 ms or an anticipated burden of RV pacing exceeding 40%.

The trial, she said, “will take years to give an answer, but it is actually designed to address the question of whether a composite endpoint of time to death or heart failure hospitalization can be improved with conduction system pacing vs. biventricular pacing.”

Dr. Al-Khatib is a coauthor on the new guideline covering both CSP and BiV-CRT in HF, as are Dr. Cha, Dr. Varma, Dr. Singh, Dr. Vijayaraman, and Dr. Goldberger; Dr. Ellenbogen is one of the reviewers.

Dr. Diaz discloses receiving honoraria or fees for speaking or teaching from Bayer Healthcare, Pfizer, AstraZeneca, Boston Scientific, and Medtronic. Dr. Vijayaraman discloses receiving honoraria or fees for speaking, teaching, or consulting for Abbott, Medtronic, Biotronik, and Boston Scientific; and receiving research grants from Medtronic. Dr. Varma discloses receiving honoraria or fees for speaking or consulting as an independent contractor for Medtronic, Boston Scientific, Biotronik, Impulse Dynamics USA, Cardiologs, Abbott, Pacemate, Implicity, and EP Solutions. Dr. Singh discloses receiving fees for consulting from EBR Systems, Merit Medical Systems, New Century Health, Biotronik, Abbott, Medtronic, MicroPort Scientific, Cardiologs, Sanofi, CVRx, Impulse Dynamics USA, Octagos, Implicity, Orchestra Biomed, Rhythm Management Group, and Biosense Webster; and receiving honoraria or fees for speaking and teaching from Medscape. Dr. Cha had no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Romero discloses receiving research grants from Biosense Webster; and speaking or receiving honoraria or fees for consulting, speaking, or teaching, or serving on a board for Sanofi, Boston Scientific, and AtriCure. Dr. Koneru discloses consulting for Medtronic and receiving honoraria from Abbott. Dr. Ellenbogen discloses consulting or lecturing for or receiving honoraria from Medtronic, Boston Scientific, and Abbott. Dr. Goldberger discloses receiving royalty income from and serving as an independent contractor for Elsevier. Dr. Al-Khatib discloses receiving research grants from Medtronic and Boston Scientific.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM HEART RHYTHM 2023

ECG implant tightens AFib management, improves outcomes in MONITOR-AF

Chronic conditions like diabetes or hypertension “often require long-term care through long-term monitoring,” observed a researcher, and “we know that continuous monitoring is superior to intermittent monitoring for long-term outcomes.”

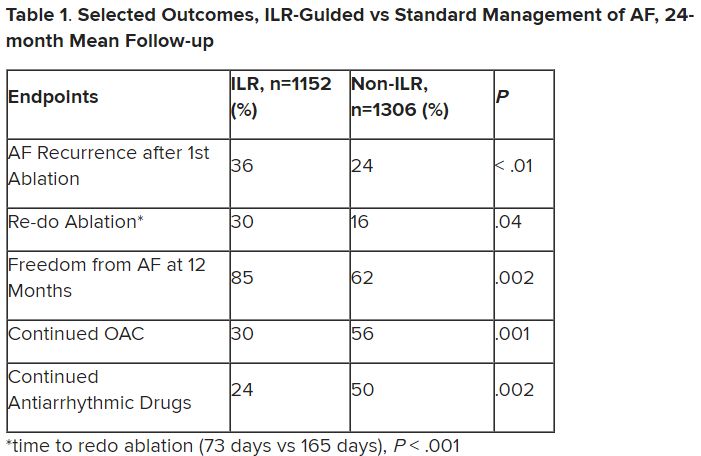

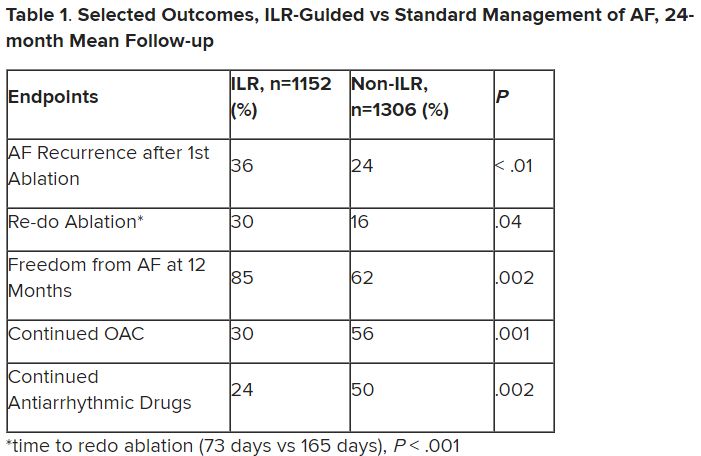

So maybe practice should rely more on continuous ECG monitoring for patients with atrial fibrillation (AFib), also a chronic condition, proposed Dhanunjaya R. Lakkireddy, MD, of the Kansas City Heart Rhythm Institute, Overland Park, Kan., in presenting a new analysis at the annual scientific sessions of the Heart Rhythm Society.

(ILRs), compared with standard care. The latter could include intermittent 12-lead ECG, Holter, or other intermittent monitoring at physicians’ discretion.

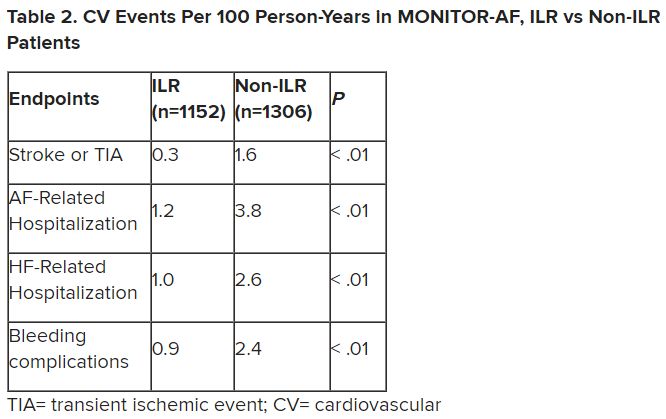

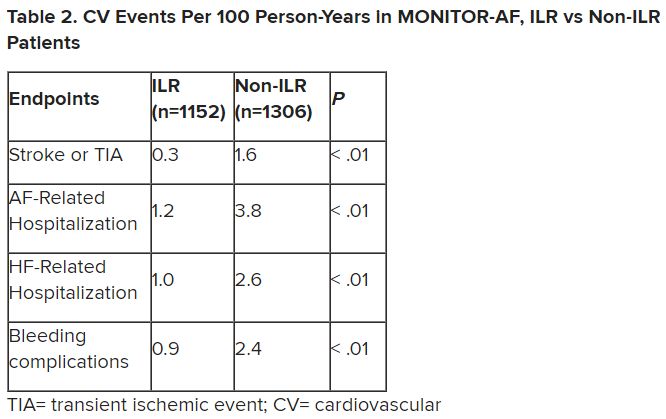

Patients with AFib and the ECG implants in the MONITOR-AF study, which was not randomized and therefore only suggestive, were managed “more efficiently” with greater access to electrophysiologists (P < .01) and adherence to oral anticoagulants (P = .020) and other medications.

Followed for a mean of 2 years, patients with ILRs were more likely to undergo catheter ablation, and their time to a catheter ablation “was impressively shorter, 153 days versus 426 days” (P < .001), Dr. Lakkireddy said.

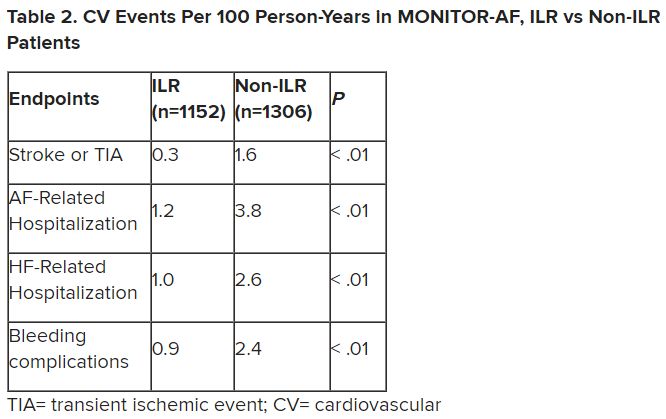

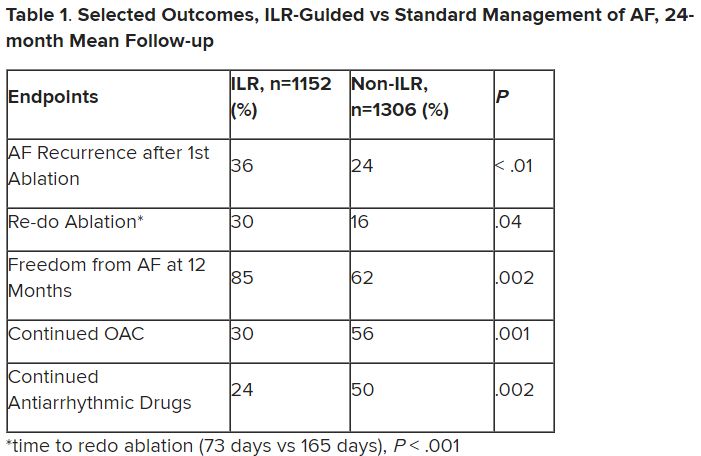

The ILR group also had fewer strokes and bleeding complications and were less likely to be hospitalized for AFib-related reasons, he said, because “a lot of these patients were caught ahead of time through the remote monitoring.”

For example, ILR patients had fewer heart failure (HF) hospitalizations, likely because “you’re not allowing these patients to remain with untreated rapid ventricular rates for a long period of time. You intervene early, thereby mitigating the onset of heart failure.”

Indeed, Dr. Lakkireddy said, their cumulative rate of any cardiovascular complication was “dramatically lower” – 3.4 versus 10.4 events per 100 person-years (P < .001).

Certainly, a routine recommendation to consider AFib patients for continuous monitoring would require randomized-trial evidence, he acknowledged. “This is an observation registry and proof of concept from a very heterogeneous cohort of patients. There were no obvious set criteria for ILR implantation.”

Nonetheless, “continuous and dynamic monitoring enabled quicker decision-making and patient management,” Dr. Lakkireddy said. “Especially in those patients who may have silent atrial fibrillation, an ILR could significantly mitigate the risk of complications from stroke and heart failure exacerbations.”

Several randomized trials have supported “earlier, more aggressive treatment” for AFib, including EAST-AFNET4, EARLY-AF, and CABANA, observed Daniel Morin, MD, MPH, of Ochsner Medical Center, New Orleans, as the invited discussant for Dr. Lakkireddy’s presentation.

So, he continued, if the goal is to “get every single AFib patient to ablation just as soon as possible,” then maybe MONITOR-AF supports the use of ILRs in such cases.

Indeed, it is “certainly possible” that the continuous stream of data from ILRs “allows faster progression of therapy and possibly even better outcomes” as MONITOR-AF suggests, said Dr. Morin, who is director of electrophysiology research at his center.

Moreover, ILR data could potentially “support shared decision-making perhaps by convincing the patient, and maybe their insurers, that we should move forward with ablation.”

But given the study’s observational, registry-based nature, the MONITOR-AF analysis is limited by potential confounders that complicate its interpretation.

For example, Dr. Morin continued, all ILR patients but only 60% of those on standard care˙ had access to an electrophysiologist (P = .001). That means “less access to some antiarrhythmic medications and certainly far less access to ablation therapy.”

Moreover, “during shared decision-making, a patient who sees the results of their ILR monitoring may be more prone to seek out or to accept earlier, more definitive therapy via ablation,” he said. “The presence of an ILR may then be a good way to move the needle toward ablation.”

Of note, an overwhelming majority of ILR patients received ablation, 93.5%, compared with 58.6% of standard-care patients. “It’s unclear how much of that association was caused by the ILR’s presence vs. other factors, such as physician availability, physician aggressiveness, or patient willingness for intervention,” Dr. Morin noted.

MONITOR-AF included 2,458 patients with paroxysmal or persistent AFib who either were implanted with or did not receive an ILR from 2018 to 2021 and were followed for at least 12 months.

The two groups were similar, Dr. Lakkireddy reported, with respect to demographics and baseline history AFib, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, coronary disease, neurovascular events, peripheral artery disease, and obstructive sleep apnea.

Dr. Lakkireddy said a subgroup analysis is forthcoming, but that he’d “intuitively” think that the 15%-20% of AFib patients who are asymptomatic would gain the most from the ILR monitoring approach. There is already evidence that such patients tend to have the worst AFib outcomes, often receiving an AFib diagnosis only after presenting with consequences such as stroke or heart failure.

Dr. Lakkireddy disclosed receiving research grants, modest honoraria, or consulting fees from Abbott, Janssen, Boston Scientific, Johnson & Johnson, Biotronik, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pfizer, Atricure, Northeast Scientific, and Acutus. Dr. Morin disclosed receiving research grants, honoraria, or consulting fees from Abbott and serving on a speakers’ bureau for Boston Scientific, Medtronic, and Zoll Medical.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Chronic conditions like diabetes or hypertension “often require long-term care through long-term monitoring,” observed a researcher, and “we know that continuous monitoring is superior to intermittent monitoring for long-term outcomes.”

So maybe practice should rely more on continuous ECG monitoring for patients with atrial fibrillation (AFib), also a chronic condition, proposed Dhanunjaya R. Lakkireddy, MD, of the Kansas City Heart Rhythm Institute, Overland Park, Kan., in presenting a new analysis at the annual scientific sessions of the Heart Rhythm Society.

(ILRs), compared with standard care. The latter could include intermittent 12-lead ECG, Holter, or other intermittent monitoring at physicians’ discretion.

Patients with AFib and the ECG implants in the MONITOR-AF study, which was not randomized and therefore only suggestive, were managed “more efficiently” with greater access to electrophysiologists (P < .01) and adherence to oral anticoagulants (P = .020) and other medications.

Followed for a mean of 2 years, patients with ILRs were more likely to undergo catheter ablation, and their time to a catheter ablation “was impressively shorter, 153 days versus 426 days” (P < .001), Dr. Lakkireddy said.

The ILR group also had fewer strokes and bleeding complications and were less likely to be hospitalized for AFib-related reasons, he said, because “a lot of these patients were caught ahead of time through the remote monitoring.”

For example, ILR patients had fewer heart failure (HF) hospitalizations, likely because “you’re not allowing these patients to remain with untreated rapid ventricular rates for a long period of time. You intervene early, thereby mitigating the onset of heart failure.”

Indeed, Dr. Lakkireddy said, their cumulative rate of any cardiovascular complication was “dramatically lower” – 3.4 versus 10.4 events per 100 person-years (P < .001).

Certainly, a routine recommendation to consider AFib patients for continuous monitoring would require randomized-trial evidence, he acknowledged. “This is an observation registry and proof of concept from a very heterogeneous cohort of patients. There were no obvious set criteria for ILR implantation.”

Nonetheless, “continuous and dynamic monitoring enabled quicker decision-making and patient management,” Dr. Lakkireddy said. “Especially in those patients who may have silent atrial fibrillation, an ILR could significantly mitigate the risk of complications from stroke and heart failure exacerbations.”

Several randomized trials have supported “earlier, more aggressive treatment” for AFib, including EAST-AFNET4, EARLY-AF, and CABANA, observed Daniel Morin, MD, MPH, of Ochsner Medical Center, New Orleans, as the invited discussant for Dr. Lakkireddy’s presentation.

So, he continued, if the goal is to “get every single AFib patient to ablation just as soon as possible,” then maybe MONITOR-AF supports the use of ILRs in such cases.

Indeed, it is “certainly possible” that the continuous stream of data from ILRs “allows faster progression of therapy and possibly even better outcomes” as MONITOR-AF suggests, said Dr. Morin, who is director of electrophysiology research at his center.

Moreover, ILR data could potentially “support shared decision-making perhaps by convincing the patient, and maybe their insurers, that we should move forward with ablation.”

But given the study’s observational, registry-based nature, the MONITOR-AF analysis is limited by potential confounders that complicate its interpretation.

For example, Dr. Morin continued, all ILR patients but only 60% of those on standard care˙ had access to an electrophysiologist (P = .001). That means “less access to some antiarrhythmic medications and certainly far less access to ablation therapy.”

Moreover, “during shared decision-making, a patient who sees the results of their ILR monitoring may be more prone to seek out or to accept earlier, more definitive therapy via ablation,” he said. “The presence of an ILR may then be a good way to move the needle toward ablation.”

Of note, an overwhelming majority of ILR patients received ablation, 93.5%, compared with 58.6% of standard-care patients. “It’s unclear how much of that association was caused by the ILR’s presence vs. other factors, such as physician availability, physician aggressiveness, or patient willingness for intervention,” Dr. Morin noted.

MONITOR-AF included 2,458 patients with paroxysmal or persistent AFib who either were implanted with or did not receive an ILR from 2018 to 2021 and were followed for at least 12 months.

The two groups were similar, Dr. Lakkireddy reported, with respect to demographics and baseline history AFib, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, coronary disease, neurovascular events, peripheral artery disease, and obstructive sleep apnea.

Dr. Lakkireddy said a subgroup analysis is forthcoming, but that he’d “intuitively” think that the 15%-20% of AFib patients who are asymptomatic would gain the most from the ILR monitoring approach. There is already evidence that such patients tend to have the worst AFib outcomes, often receiving an AFib diagnosis only after presenting with consequences such as stroke or heart failure.

Dr. Lakkireddy disclosed receiving research grants, modest honoraria, or consulting fees from Abbott, Janssen, Boston Scientific, Johnson & Johnson, Biotronik, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pfizer, Atricure, Northeast Scientific, and Acutus. Dr. Morin disclosed receiving research grants, honoraria, or consulting fees from Abbott and serving on a speakers’ bureau for Boston Scientific, Medtronic, and Zoll Medical.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Chronic conditions like diabetes or hypertension “often require long-term care through long-term monitoring,” observed a researcher, and “we know that continuous monitoring is superior to intermittent monitoring for long-term outcomes.”

So maybe practice should rely more on continuous ECG monitoring for patients with atrial fibrillation (AFib), also a chronic condition, proposed Dhanunjaya R. Lakkireddy, MD, of the Kansas City Heart Rhythm Institute, Overland Park, Kan., in presenting a new analysis at the annual scientific sessions of the Heart Rhythm Society.

(ILRs), compared with standard care. The latter could include intermittent 12-lead ECG, Holter, or other intermittent monitoring at physicians’ discretion.

Patients with AFib and the ECG implants in the MONITOR-AF study, which was not randomized and therefore only suggestive, were managed “more efficiently” with greater access to electrophysiologists (P < .01) and adherence to oral anticoagulants (P = .020) and other medications.

Followed for a mean of 2 years, patients with ILRs were more likely to undergo catheter ablation, and their time to a catheter ablation “was impressively shorter, 153 days versus 426 days” (P < .001), Dr. Lakkireddy said.

The ILR group also had fewer strokes and bleeding complications and were less likely to be hospitalized for AFib-related reasons, he said, because “a lot of these patients were caught ahead of time through the remote monitoring.”

For example, ILR patients had fewer heart failure (HF) hospitalizations, likely because “you’re not allowing these patients to remain with untreated rapid ventricular rates for a long period of time. You intervene early, thereby mitigating the onset of heart failure.”

Indeed, Dr. Lakkireddy said, their cumulative rate of any cardiovascular complication was “dramatically lower” – 3.4 versus 10.4 events per 100 person-years (P < .001).

Certainly, a routine recommendation to consider AFib patients for continuous monitoring would require randomized-trial evidence, he acknowledged. “This is an observation registry and proof of concept from a very heterogeneous cohort of patients. There were no obvious set criteria for ILR implantation.”

Nonetheless, “continuous and dynamic monitoring enabled quicker decision-making and patient management,” Dr. Lakkireddy said. “Especially in those patients who may have silent atrial fibrillation, an ILR could significantly mitigate the risk of complications from stroke and heart failure exacerbations.”

Several randomized trials have supported “earlier, more aggressive treatment” for AFib, including EAST-AFNET4, EARLY-AF, and CABANA, observed Daniel Morin, MD, MPH, of Ochsner Medical Center, New Orleans, as the invited discussant for Dr. Lakkireddy’s presentation.

So, he continued, if the goal is to “get every single AFib patient to ablation just as soon as possible,” then maybe MONITOR-AF supports the use of ILRs in such cases.

Indeed, it is “certainly possible” that the continuous stream of data from ILRs “allows faster progression of therapy and possibly even better outcomes” as MONITOR-AF suggests, said Dr. Morin, who is director of electrophysiology research at his center.

Moreover, ILR data could potentially “support shared decision-making perhaps by convincing the patient, and maybe their insurers, that we should move forward with ablation.”

But given the study’s observational, registry-based nature, the MONITOR-AF analysis is limited by potential confounders that complicate its interpretation.

For example, Dr. Morin continued, all ILR patients but only 60% of those on standard care˙ had access to an electrophysiologist (P = .001). That means “less access to some antiarrhythmic medications and certainly far less access to ablation therapy.”

Moreover, “during shared decision-making, a patient who sees the results of their ILR monitoring may be more prone to seek out or to accept earlier, more definitive therapy via ablation,” he said. “The presence of an ILR may then be a good way to move the needle toward ablation.”

Of note, an overwhelming majority of ILR patients received ablation, 93.5%, compared with 58.6% of standard-care patients. “It’s unclear how much of that association was caused by the ILR’s presence vs. other factors, such as physician availability, physician aggressiveness, or patient willingness for intervention,” Dr. Morin noted.

MONITOR-AF included 2,458 patients with paroxysmal or persistent AFib who either were implanted with or did not receive an ILR from 2018 to 2021 and were followed for at least 12 months.

The two groups were similar, Dr. Lakkireddy reported, with respect to demographics and baseline history AFib, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, coronary disease, neurovascular events, peripheral artery disease, and obstructive sleep apnea.

Dr. Lakkireddy said a subgroup analysis is forthcoming, but that he’d “intuitively” think that the 15%-20% of AFib patients who are asymptomatic would gain the most from the ILR monitoring approach. There is already evidence that such patients tend to have the worst AFib outcomes, often receiving an AFib diagnosis only after presenting with consequences such as stroke or heart failure.

Dr. Lakkireddy disclosed receiving research grants, modest honoraria, or consulting fees from Abbott, Janssen, Boston Scientific, Johnson & Johnson, Biotronik, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pfizer, Atricure, Northeast Scientific, and Acutus. Dr. Morin disclosed receiving research grants, honoraria, or consulting fees from Abbott and serving on a speakers’ bureau for Boston Scientific, Medtronic, and Zoll Medical.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM HEART RHYTHM 2023

Leadless dual-chamber pacemaker clears early safety, performance hurdles

Cardiology, well into the age of leadless pacemakers, could be headed for an age of leadless pacemaker systems in which various pacing functions are achieved by multiple implants that “talk” to each other.

Even now, a leadless two-part pacemaker system has shown it can safely achieve atrioventricular (AV) synchrony in patients with standard indications for a dual-chamber device, at least over the short term, suggests a prospective observational study. Currently available leadless pacemakers can stimulate only the right ventricle.

Experienced operators achieved a 98% implantation success rate in 300 patients who received an investigational dual-chamber leadless system, the AVEIR DR i2i (Abbott).

Its two separately implanted miniature pulse generators achieve AV synchrony via “beat-to-beat wireless bidirectional communication,” Daniel J. Cantillon, MD, said when presenting the study at the annual scientific sessions of the Heart Rhythm Societyin New Orleans.

The system seemed to work well regardless of the patient’s body orientation. “Sitting, supine, left lateral, right lateral, standing, normal walk, fast walk – we demonstrated robust AV synchrony in all of those positions and with movement,” said Dr. Cantillon, of the Cleveland Clinic.

Should the device be approved, it could “expand the use case for leadless cardiac pacing” to include atrial-only, ventricular-only, fully functional dual-chamber pacing scenarios.”

Dr. Cantillon is senior author on the study’s online publication in the New England Journal of Medicine, timed to coincide with his HRS presentation, with first author Reinoud E. Knops, MD, PhD, Amsterdam University Medical Center.

“The electrical performance of both the atrial and ventricular leadless pacemakers appears to be similar to that of transvenous dual-chamber pacemakers,” the published report states.

More data needed

The study is important and has “significant implications for our pacing field,” Jonathan P. Piccini, MD, MHS, said in an interview. It suggests that “dual-chamber pacing can be achieved with leadless technology” and “with a very high degree” of AV synchrony.

“Obviously, more data as the technology moves into clinical practice will be critical,” said Dr. Piccini, who directs cardiac electrophysiology at Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C. “We will also need to understand which patients are best served by leadless technology and which will be better served with traditional transvenous devices.”

The AVEIR DR i2i system consists of two leadless pulse generators for percutaneous implantation in the right atrium and right ventricle, respectively. They link like components of a wireless network to coordinate their separate sensing and rate-adaptive, AV-synchronous pacing functions.

The right ventricular implant “is physically identical to a commercially available single-chamber leadless pacemaker” from Abbott, the published report states.

Leadless pacemaker systems inherently avoid the two main sources of transvenous devices’ major complication – infection – by not requiring such leads or surgery for creating a pulse-generator subcutaneous pocket.

The first such systems consisted of one implant that could provide single-chamber ventricular pacing but not atrial pacing or AV synchronous pacing. The transcatheter single-chamber leadless Micra (Medtronic) for example, was approved in the United States in April 2016 for ventricular-only pacing.

A successor, the Micra AV, approved in 2020, was designed to simulate AV-synchronous pacing by stimulating the ventricle in sequence with mechanically sensed atrial contractions, as described by Dr. Cantillon and associates. But it could not directly pace the atrium, “rendering it inappropriate for patients with sinus-node dysfunction.”

The AVEIR DR i2i system doesn’t have those limitations. It was, however, associated with 35 device- or procedure-related complications in the study, of which the most common was procedural arrhythmia, “namely atrial fibrillation,” Dr. Cantillon said.

Atrial fibrillation can develop during implantation of pacemakers with transvenous leads but is generally terminated without being considered an important event. Yet the study classified it as a serious complication, inflating the complication rate, because “the patients had to be restored to sinus rhythm so we could assess the AV synchrony and also the atrial electrical performance,” he said.

Some of the devices dislodged from their implantation site within a month of the procedure, but “all of those patients were successfully managed percutaneously,” said Dr. Cantillon.

“The 1.7% dislodgement rate is something that we will need to keep an eye on, as embolization of devices is always a significant concern,” Dr. Piccini said. Still, the observed total complication rate “was certainly in line” with rates associated with conventional pacemaker implantation.

Reliable AV synchrony

Fred M. Kusumoto, MD, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, Fla., lauded what seems to be the system’s “incredibly reliable AV synchrony in different conditions, albeit in a very controlled environment.”

Of interest will be whether its performance, including maintenance of AV synchrony, holds up in “a more long-term evaluation in the outpatient setting,” said Dr. Kusumoto, speaking as the invited discussant for Dr. Cantillon’s presentation.

Also missing or in short supply from the study, he observed, are insights about long-term efficacy and complications, battery longevity, effectiveness of its rate-responsive capability, and any effect on clinical outcomes.

Local body network

Of the study’s 300 patients (mean age 69 years; 38% female) at 55 sites in Canada, Europe, and the United States, 63.3% had sinus-node dysfunction and 33.3% had AV block as their primary dual-chamber pacing indication; 298 were successfully implanted with both devices.

About 45% had a history of supraventricular arrhythmia, 4.3% had prior ventricular arrhythmia, and 20% had a history of arrhythmia ablation.

By 3 months, the group reported, the primary safety endpoint (freedom from device- or procedure-related serious adverse events) occurred in 90.3%, compared with the performance goal of 78% (P < .001).

The first of two primary performance endpoints (adequate atrial capture threshold and sensing amplitude by predefined criteria) was met in 90.2%, surpassing the 82.5% performance goal (P < .001).

The second primary performance goal (at least 70% AV synchrony with the patient sitting) was seen in 97.3% against the performance goal of 83% (P < .001).

What shouldn’t be “glossed over” from the study, Dr. Kusumoto offered, is that it’s possible to achieve a wireless connection “between two devices that are actually intracardiac.” That raises the prospect of a “local body network” that could be “expanded even more dramatically with other types of devices. I mean, think of the paradigm shift.”

The AVEIR DR i2i trial was funded by Abbott. Dr. Cantillon discloses receiving honoraria or fees for speaking or consulting from Abbott Laboratories, Boston Scientific, Biosense Webster, and Shockwave Medical, as well as holding royalty rights with AirStrip. Dr. Piccini has disclosed relationships with Abbott, Medtronic, Biotronik, Boston Scientific, and other drug and medical device companies. Dr. Kusumoto reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Cardiology, well into the age of leadless pacemakers, could be headed for an age of leadless pacemaker systems in which various pacing functions are achieved by multiple implants that “talk” to each other.

Even now, a leadless two-part pacemaker system has shown it can safely achieve atrioventricular (AV) synchrony in patients with standard indications for a dual-chamber device, at least over the short term, suggests a prospective observational study. Currently available leadless pacemakers can stimulate only the right ventricle.

Experienced operators achieved a 98% implantation success rate in 300 patients who received an investigational dual-chamber leadless system, the AVEIR DR i2i (Abbott).

Its two separately implanted miniature pulse generators achieve AV synchrony via “beat-to-beat wireless bidirectional communication,” Daniel J. Cantillon, MD, said when presenting the study at the annual scientific sessions of the Heart Rhythm Societyin New Orleans.

The system seemed to work well regardless of the patient’s body orientation. “Sitting, supine, left lateral, right lateral, standing, normal walk, fast walk – we demonstrated robust AV synchrony in all of those positions and with movement,” said Dr. Cantillon, of the Cleveland Clinic.

Should the device be approved, it could “expand the use case for leadless cardiac pacing” to include atrial-only, ventricular-only, fully functional dual-chamber pacing scenarios.”

Dr. Cantillon is senior author on the study’s online publication in the New England Journal of Medicine, timed to coincide with his HRS presentation, with first author Reinoud E. Knops, MD, PhD, Amsterdam University Medical Center.

“The electrical performance of both the atrial and ventricular leadless pacemakers appears to be similar to that of transvenous dual-chamber pacemakers,” the published report states.

More data needed

The study is important and has “significant implications for our pacing field,” Jonathan P. Piccini, MD, MHS, said in an interview. It suggests that “dual-chamber pacing can be achieved with leadless technology” and “with a very high degree” of AV synchrony.

“Obviously, more data as the technology moves into clinical practice will be critical,” said Dr. Piccini, who directs cardiac electrophysiology at Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C. “We will also need to understand which patients are best served by leadless technology and which will be better served with traditional transvenous devices.”

The AVEIR DR i2i system consists of two leadless pulse generators for percutaneous implantation in the right atrium and right ventricle, respectively. They link like components of a wireless network to coordinate their separate sensing and rate-adaptive, AV-synchronous pacing functions.

The right ventricular implant “is physically identical to a commercially available single-chamber leadless pacemaker” from Abbott, the published report states.

Leadless pacemaker systems inherently avoid the two main sources of transvenous devices’ major complication – infection – by not requiring such leads or surgery for creating a pulse-generator subcutaneous pocket.

The first such systems consisted of one implant that could provide single-chamber ventricular pacing but not atrial pacing or AV synchronous pacing. The transcatheter single-chamber leadless Micra (Medtronic) for example, was approved in the United States in April 2016 for ventricular-only pacing.

A successor, the Micra AV, approved in 2020, was designed to simulate AV-synchronous pacing by stimulating the ventricle in sequence with mechanically sensed atrial contractions, as described by Dr. Cantillon and associates. But it could not directly pace the atrium, “rendering it inappropriate for patients with sinus-node dysfunction.”

The AVEIR DR i2i system doesn’t have those limitations. It was, however, associated with 35 device- or procedure-related complications in the study, of which the most common was procedural arrhythmia, “namely atrial fibrillation,” Dr. Cantillon said.

Atrial fibrillation can develop during implantation of pacemakers with transvenous leads but is generally terminated without being considered an important event. Yet the study classified it as a serious complication, inflating the complication rate, because “the patients had to be restored to sinus rhythm so we could assess the AV synchrony and also the atrial electrical performance,” he said.

Some of the devices dislodged from their implantation site within a month of the procedure, but “all of those patients were successfully managed percutaneously,” said Dr. Cantillon.

“The 1.7% dislodgement rate is something that we will need to keep an eye on, as embolization of devices is always a significant concern,” Dr. Piccini said. Still, the observed total complication rate “was certainly in line” with rates associated with conventional pacemaker implantation.

Reliable AV synchrony

Fred M. Kusumoto, MD, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, Fla., lauded what seems to be the system’s “incredibly reliable AV synchrony in different conditions, albeit in a very controlled environment.”

Of interest will be whether its performance, including maintenance of AV synchrony, holds up in “a more long-term evaluation in the outpatient setting,” said Dr. Kusumoto, speaking as the invited discussant for Dr. Cantillon’s presentation.

Also missing or in short supply from the study, he observed, are insights about long-term efficacy and complications, battery longevity, effectiveness of its rate-responsive capability, and any effect on clinical outcomes.

Local body network

Of the study’s 300 patients (mean age 69 years; 38% female) at 55 sites in Canada, Europe, and the United States, 63.3% had sinus-node dysfunction and 33.3% had AV block as their primary dual-chamber pacing indication; 298 were successfully implanted with both devices.

About 45% had a history of supraventricular arrhythmia, 4.3% had prior ventricular arrhythmia, and 20% had a history of arrhythmia ablation.

By 3 months, the group reported, the primary safety endpoint (freedom from device- or procedure-related serious adverse events) occurred in 90.3%, compared with the performance goal of 78% (P < .001).

The first of two primary performance endpoints (adequate atrial capture threshold and sensing amplitude by predefined criteria) was met in 90.2%, surpassing the 82.5% performance goal (P < .001).

The second primary performance goal (at least 70% AV synchrony with the patient sitting) was seen in 97.3% against the performance goal of 83% (P < .001).

What shouldn’t be “glossed over” from the study, Dr. Kusumoto offered, is that it’s possible to achieve a wireless connection “between two devices that are actually intracardiac.” That raises the prospect of a “local body network” that could be “expanded even more dramatically with other types of devices. I mean, think of the paradigm shift.”

The AVEIR DR i2i trial was funded by Abbott. Dr. Cantillon discloses receiving honoraria or fees for speaking or consulting from Abbott Laboratories, Boston Scientific, Biosense Webster, and Shockwave Medical, as well as holding royalty rights with AirStrip. Dr. Piccini has disclosed relationships with Abbott, Medtronic, Biotronik, Boston Scientific, and other drug and medical device companies. Dr. Kusumoto reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Cardiology, well into the age of leadless pacemakers, could be headed for an age of leadless pacemaker systems in which various pacing functions are achieved by multiple implants that “talk” to each other.

Even now, a leadless two-part pacemaker system has shown it can safely achieve atrioventricular (AV) synchrony in patients with standard indications for a dual-chamber device, at least over the short term, suggests a prospective observational study. Currently available leadless pacemakers can stimulate only the right ventricle.

Experienced operators achieved a 98% implantation success rate in 300 patients who received an investigational dual-chamber leadless system, the AVEIR DR i2i (Abbott).

Its two separately implanted miniature pulse generators achieve AV synchrony via “beat-to-beat wireless bidirectional communication,” Daniel J. Cantillon, MD, said when presenting the study at the annual scientific sessions of the Heart Rhythm Societyin New Orleans.

The system seemed to work well regardless of the patient’s body orientation. “Sitting, supine, left lateral, right lateral, standing, normal walk, fast walk – we demonstrated robust AV synchrony in all of those positions and with movement,” said Dr. Cantillon, of the Cleveland Clinic.

Should the device be approved, it could “expand the use case for leadless cardiac pacing” to include atrial-only, ventricular-only, fully functional dual-chamber pacing scenarios.”

Dr. Cantillon is senior author on the study’s online publication in the New England Journal of Medicine, timed to coincide with his HRS presentation, with first author Reinoud E. Knops, MD, PhD, Amsterdam University Medical Center.

“The electrical performance of both the atrial and ventricular leadless pacemakers appears to be similar to that of transvenous dual-chamber pacemakers,” the published report states.

More data needed

The study is important and has “significant implications for our pacing field,” Jonathan P. Piccini, MD, MHS, said in an interview. It suggests that “dual-chamber pacing can be achieved with leadless technology” and “with a very high degree” of AV synchrony.

“Obviously, more data as the technology moves into clinical practice will be critical,” said Dr. Piccini, who directs cardiac electrophysiology at Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C. “We will also need to understand which patients are best served by leadless technology and which will be better served with traditional transvenous devices.”

The AVEIR DR i2i system consists of two leadless pulse generators for percutaneous implantation in the right atrium and right ventricle, respectively. They link like components of a wireless network to coordinate their separate sensing and rate-adaptive, AV-synchronous pacing functions.

The right ventricular implant “is physically identical to a commercially available single-chamber leadless pacemaker” from Abbott, the published report states.

Leadless pacemaker systems inherently avoid the two main sources of transvenous devices’ major complication – infection – by not requiring such leads or surgery for creating a pulse-generator subcutaneous pocket.

The first such systems consisted of one implant that could provide single-chamber ventricular pacing but not atrial pacing or AV synchronous pacing. The transcatheter single-chamber leadless Micra (Medtronic) for example, was approved in the United States in April 2016 for ventricular-only pacing.

A successor, the Micra AV, approved in 2020, was designed to simulate AV-synchronous pacing by stimulating the ventricle in sequence with mechanically sensed atrial contractions, as described by Dr. Cantillon and associates. But it could not directly pace the atrium, “rendering it inappropriate for patients with sinus-node dysfunction.”

The AVEIR DR i2i system doesn’t have those limitations. It was, however, associated with 35 device- or procedure-related complications in the study, of which the most common was procedural arrhythmia, “namely atrial fibrillation,” Dr. Cantillon said.

Atrial fibrillation can develop during implantation of pacemakers with transvenous leads but is generally terminated without being considered an important event. Yet the study classified it as a serious complication, inflating the complication rate, because “the patients had to be restored to sinus rhythm so we could assess the AV synchrony and also the atrial electrical performance,” he said.

Some of the devices dislodged from their implantation site within a month of the procedure, but “all of those patients were successfully managed percutaneously,” said Dr. Cantillon.

“The 1.7% dislodgement rate is something that we will need to keep an eye on, as embolization of devices is always a significant concern,” Dr. Piccini said. Still, the observed total complication rate “was certainly in line” with rates associated with conventional pacemaker implantation.

Reliable AV synchrony

Fred M. Kusumoto, MD, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, Fla., lauded what seems to be the system’s “incredibly reliable AV synchrony in different conditions, albeit in a very controlled environment.”

Of interest will be whether its performance, including maintenance of AV synchrony, holds up in “a more long-term evaluation in the outpatient setting,” said Dr. Kusumoto, speaking as the invited discussant for Dr. Cantillon’s presentation.

Also missing or in short supply from the study, he observed, are insights about long-term efficacy and complications, battery longevity, effectiveness of its rate-responsive capability, and any effect on clinical outcomes.

Local body network

Of the study’s 300 patients (mean age 69 years; 38% female) at 55 sites in Canada, Europe, and the United States, 63.3% had sinus-node dysfunction and 33.3% had AV block as their primary dual-chamber pacing indication; 298 were successfully implanted with both devices.

About 45% had a history of supraventricular arrhythmia, 4.3% had prior ventricular arrhythmia, and 20% had a history of arrhythmia ablation.