User login

Pruritic, violaceous papules in a patient with renal cell carcinoma

Pembrolizumab (Keytruda) is a programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) blocking antibody used to treat different malignancies including melanoma, non–small cell lung cancer, and other advanced solid tumors and hematologic malignancies. and drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS).

Lichen planus-like adverse drug reactions, as seen in this patient, are also referred to as lichenoid drug eruption or drug-induced lichen planus. This cutaneous reaction is one of the more rare side effects of pembrolizumab. It should be noted that in lichenoid reactions, keratinocytes expressing PD-L1 are particularly affected, leading to a dense CD4/CD8 positive lymphocytic infiltration in the basal layer, necrosis of keratinocytes, acanthosis, and hypergranulosis. Subsequently, the cutaneous adverse reaction is a target effect of the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway and not a general hypersensitivity reaction. Clinically, both lichen planus and lichenoid drug eruptions exhibit erythematous papules and plaques. Lichenoid drug eruptions, however, can be scaly, pruritic, and heal with more hyperpigmentation.

A skin biopsy revealed irregular epidermal hyperplasia with jagged rete ridges. Within the dermis, there was a lichenoid inflammatory cell infiltrate obscuring the dermal-epidermal junction. The inflammatory cell infiltrate contained lymphocytes, histiocytes, and eosinophils. A diagnosis of a lichen planus-like adverse drug reaction to pembrolizumab was favored.

If the reaction is mild, topical corticosteroids and oral antihistamines can help with the drug-induced lichen planus. For more severe cases, systemic steroids can be given to help ease the reaction. Physicians should be aware of potential adverse drug effects that can mimic other medical conditions.

The case and photo were submitted by Ms. Towe, Nova Southeastern University College of Osteopathic Medicine, Davie, Florida, and Dr. Berke, Three Rivers Dermatology, Coraopolis, Pennsylvania. The column was edited by Donna Bilu Martin, MD.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@mdedge.com.

References

Bansal A et al. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2023 Apr 4;14(3):391-4. doi: 10.4103/idoj.idoj_377_22.

Sethi A, Raj M. Cureus. 2021 Mar 8;13(3):e13768. doi: 10.7759/cureus.13768.

Pembrolizumab (Keytruda) is a programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) blocking antibody used to treat different malignancies including melanoma, non–small cell lung cancer, and other advanced solid tumors and hematologic malignancies. and drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS).

Lichen planus-like adverse drug reactions, as seen in this patient, are also referred to as lichenoid drug eruption or drug-induced lichen planus. This cutaneous reaction is one of the more rare side effects of pembrolizumab. It should be noted that in lichenoid reactions, keratinocytes expressing PD-L1 are particularly affected, leading to a dense CD4/CD8 positive lymphocytic infiltration in the basal layer, necrosis of keratinocytes, acanthosis, and hypergranulosis. Subsequently, the cutaneous adverse reaction is a target effect of the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway and not a general hypersensitivity reaction. Clinically, both lichen planus and lichenoid drug eruptions exhibit erythematous papules and plaques. Lichenoid drug eruptions, however, can be scaly, pruritic, and heal with more hyperpigmentation.

A skin biopsy revealed irregular epidermal hyperplasia with jagged rete ridges. Within the dermis, there was a lichenoid inflammatory cell infiltrate obscuring the dermal-epidermal junction. The inflammatory cell infiltrate contained lymphocytes, histiocytes, and eosinophils. A diagnosis of a lichen planus-like adverse drug reaction to pembrolizumab was favored.

If the reaction is mild, topical corticosteroids and oral antihistamines can help with the drug-induced lichen planus. For more severe cases, systemic steroids can be given to help ease the reaction. Physicians should be aware of potential adverse drug effects that can mimic other medical conditions.

The case and photo were submitted by Ms. Towe, Nova Southeastern University College of Osteopathic Medicine, Davie, Florida, and Dr. Berke, Three Rivers Dermatology, Coraopolis, Pennsylvania. The column was edited by Donna Bilu Martin, MD.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@mdedge.com.

References

Bansal A et al. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2023 Apr 4;14(3):391-4. doi: 10.4103/idoj.idoj_377_22.

Sethi A, Raj M. Cureus. 2021 Mar 8;13(3):e13768. doi: 10.7759/cureus.13768.

Pembrolizumab (Keytruda) is a programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) blocking antibody used to treat different malignancies including melanoma, non–small cell lung cancer, and other advanced solid tumors and hematologic malignancies. and drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS).

Lichen planus-like adverse drug reactions, as seen in this patient, are also referred to as lichenoid drug eruption or drug-induced lichen planus. This cutaneous reaction is one of the more rare side effects of pembrolizumab. It should be noted that in lichenoid reactions, keratinocytes expressing PD-L1 are particularly affected, leading to a dense CD4/CD8 positive lymphocytic infiltration in the basal layer, necrosis of keratinocytes, acanthosis, and hypergranulosis. Subsequently, the cutaneous adverse reaction is a target effect of the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway and not a general hypersensitivity reaction. Clinically, both lichen planus and lichenoid drug eruptions exhibit erythematous papules and plaques. Lichenoid drug eruptions, however, can be scaly, pruritic, and heal with more hyperpigmentation.

A skin biopsy revealed irregular epidermal hyperplasia with jagged rete ridges. Within the dermis, there was a lichenoid inflammatory cell infiltrate obscuring the dermal-epidermal junction. The inflammatory cell infiltrate contained lymphocytes, histiocytes, and eosinophils. A diagnosis of a lichen planus-like adverse drug reaction to pembrolizumab was favored.

If the reaction is mild, topical corticosteroids and oral antihistamines can help with the drug-induced lichen planus. For more severe cases, systemic steroids can be given to help ease the reaction. Physicians should be aware of potential adverse drug effects that can mimic other medical conditions.

The case and photo were submitted by Ms. Towe, Nova Southeastern University College of Osteopathic Medicine, Davie, Florida, and Dr. Berke, Three Rivers Dermatology, Coraopolis, Pennsylvania. The column was edited by Donna Bilu Martin, MD.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@mdedge.com.

References

Bansal A et al. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2023 Apr 4;14(3):391-4. doi: 10.4103/idoj.idoj_377_22.

Sethi A, Raj M. Cureus. 2021 Mar 8;13(3):e13768. doi: 10.7759/cureus.13768.

A White male presented with a purulent erythematous edematous plaque with central necrosis and ulceration on his right flank

Lyme disease is the most commonly transmitted tick-borne illness in the United States. This infection is typically transmitted through a bite by the Ixodes tick commonly found in the Midwest, Northeast, and mid-Atlantic regions; however, the geographical distribution continues to expand over time in the United States. Ticks must be attached for 24-48 hours to transmit the pathogen. There are three general stages of the disease: early localized, early disseminated, and late disseminated.

The most common presentation is the early localized disease, which manifests between 3 and 30 days after an infected tick bite. Approximately 70%-80% of cases feature a targetlike lesion that expands centrifugally at the site of the bite. Most commonly, lesions appear on the abdomen, groin, axilla, and popliteal fossa. The diagnosis of ECM requires lesions at least 5 cm in size. Lesions may be asymptomatic, although burning may occur in half of patients. Atypical presentations include bullous, vesicular, hemorrhagic, or necrotic lesions. Up to half of patients may develop multiple ECM lesions. Palms and soles are spared. Differential diagnoses include arthropod reactions, pyoderma gangrenosum, cellulitis, herpes simplex virus and varicella zoster virus, contact dermatitis, or granuloma annulare. The rash is often accompanied by systemic symptoms including fatigue, myalgia, headache, and fever.

The next two stages include early and late disseminated infection. Early disseminated infection often occurs 3-12 weeks after infection and is characterized by muscle pain, dizziness, headache, and cardiac symptoms. CNS involvement occurs in about 20% of patients. Joint involvement may include the knee, ankle, and wrist. If symptoms are only in one joint, septic arthritis is part of the differential diagnosis, so clinical correlation and labs must be considered. Late disseminated infection occurs months or years after initial infection and includes neurologic and rheumatologic symptoms including meningitis, Bell’s palsy, arthritis, and dysesthesia. Knee arthritis is a key feature of this stage. Patients commonly have radicular pain and fibromyalgia-type pain. More severe disease processes include encephalomyelitis, arrhythmias, and heart block.

ECM is often a clinical diagnosis because serologic testing may not be positive during the first 2 weeks of infection. The screening serologic test is the ELISA, and a Western blot confirms the results. Skin histopathology for Lyme disease is often nonspecific and reveals a perivascular infiltrate of histiocytes, plasma cells, and lymphocytes. Silver stain or antibody testing may be used to identify the spirochete. In acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans, late Lyme disease presenting on the distal extremities, lymphocytic and plasma cell infiltrates are present. In borrelial lymphocytoma, a dense dermal lymphocytic infiltrate is present.

The standard for treatment of early localized disease is oral doxycycline in adults. Alternatives may be used if a patient is allergic or for children under 9. Disseminated disease may be treated with IV ceftriaxone and topical steroids are used if ocular symptoms are involved. Early treatment is often curative.

This patient’s antibodies were negative initially, but became positive after 6 weeks. He was treated empirically at the time of his office visit with doxycycline for 1 month.

This case and the photo were submitted by Lucas Shapiro, BS, of Nova Southeastern University College of Osteopathic Medicine, Fort Lauderdale, Fla., and Susannah Berke, MD, Three Rivers Dermatology, Coraopolis, Pa. The column was edited by Donna Bilu Martin, MD.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at MDedge.com/Dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@mdedge.com.

References

Carriveau A et al. Nurs Clin North Am. 2019 Jun;54(2):261-75.

Skar GL and Simonsen KA. Lyme Disease. [Updated 2023 May 31]. In: “StatPearls” [Internet]. Treasure Island, Fla.: StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan.

Tiger JB et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014 Oct;71(4):e133-4.

Lyme disease is the most commonly transmitted tick-borne illness in the United States. This infection is typically transmitted through a bite by the Ixodes tick commonly found in the Midwest, Northeast, and mid-Atlantic regions; however, the geographical distribution continues to expand over time in the United States. Ticks must be attached for 24-48 hours to transmit the pathogen. There are three general stages of the disease: early localized, early disseminated, and late disseminated.

The most common presentation is the early localized disease, which manifests between 3 and 30 days after an infected tick bite. Approximately 70%-80% of cases feature a targetlike lesion that expands centrifugally at the site of the bite. Most commonly, lesions appear on the abdomen, groin, axilla, and popliteal fossa. The diagnosis of ECM requires lesions at least 5 cm in size. Lesions may be asymptomatic, although burning may occur in half of patients. Atypical presentations include bullous, vesicular, hemorrhagic, or necrotic lesions. Up to half of patients may develop multiple ECM lesions. Palms and soles are spared. Differential diagnoses include arthropod reactions, pyoderma gangrenosum, cellulitis, herpes simplex virus and varicella zoster virus, contact dermatitis, or granuloma annulare. The rash is often accompanied by systemic symptoms including fatigue, myalgia, headache, and fever.

The next two stages include early and late disseminated infection. Early disseminated infection often occurs 3-12 weeks after infection and is characterized by muscle pain, dizziness, headache, and cardiac symptoms. CNS involvement occurs in about 20% of patients. Joint involvement may include the knee, ankle, and wrist. If symptoms are only in one joint, septic arthritis is part of the differential diagnosis, so clinical correlation and labs must be considered. Late disseminated infection occurs months or years after initial infection and includes neurologic and rheumatologic symptoms including meningitis, Bell’s palsy, arthritis, and dysesthesia. Knee arthritis is a key feature of this stage. Patients commonly have radicular pain and fibromyalgia-type pain. More severe disease processes include encephalomyelitis, arrhythmias, and heart block.

ECM is often a clinical diagnosis because serologic testing may not be positive during the first 2 weeks of infection. The screening serologic test is the ELISA, and a Western blot confirms the results. Skin histopathology for Lyme disease is often nonspecific and reveals a perivascular infiltrate of histiocytes, plasma cells, and lymphocytes. Silver stain or antibody testing may be used to identify the spirochete. In acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans, late Lyme disease presenting on the distal extremities, lymphocytic and plasma cell infiltrates are present. In borrelial lymphocytoma, a dense dermal lymphocytic infiltrate is present.

The standard for treatment of early localized disease is oral doxycycline in adults. Alternatives may be used if a patient is allergic or for children under 9. Disseminated disease may be treated with IV ceftriaxone and topical steroids are used if ocular symptoms are involved. Early treatment is often curative.

This patient’s antibodies were negative initially, but became positive after 6 weeks. He was treated empirically at the time of his office visit with doxycycline for 1 month.

This case and the photo were submitted by Lucas Shapiro, BS, of Nova Southeastern University College of Osteopathic Medicine, Fort Lauderdale, Fla., and Susannah Berke, MD, Three Rivers Dermatology, Coraopolis, Pa. The column was edited by Donna Bilu Martin, MD.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at MDedge.com/Dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@mdedge.com.

References

Carriveau A et al. Nurs Clin North Am. 2019 Jun;54(2):261-75.

Skar GL and Simonsen KA. Lyme Disease. [Updated 2023 May 31]. In: “StatPearls” [Internet]. Treasure Island, Fla.: StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan.

Tiger JB et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014 Oct;71(4):e133-4.

Lyme disease is the most commonly transmitted tick-borne illness in the United States. This infection is typically transmitted through a bite by the Ixodes tick commonly found in the Midwest, Northeast, and mid-Atlantic regions; however, the geographical distribution continues to expand over time in the United States. Ticks must be attached for 24-48 hours to transmit the pathogen. There are three general stages of the disease: early localized, early disseminated, and late disseminated.

The most common presentation is the early localized disease, which manifests between 3 and 30 days after an infected tick bite. Approximately 70%-80% of cases feature a targetlike lesion that expands centrifugally at the site of the bite. Most commonly, lesions appear on the abdomen, groin, axilla, and popliteal fossa. The diagnosis of ECM requires lesions at least 5 cm in size. Lesions may be asymptomatic, although burning may occur in half of patients. Atypical presentations include bullous, vesicular, hemorrhagic, or necrotic lesions. Up to half of patients may develop multiple ECM lesions. Palms and soles are spared. Differential diagnoses include arthropod reactions, pyoderma gangrenosum, cellulitis, herpes simplex virus and varicella zoster virus, contact dermatitis, or granuloma annulare. The rash is often accompanied by systemic symptoms including fatigue, myalgia, headache, and fever.

The next two stages include early and late disseminated infection. Early disseminated infection often occurs 3-12 weeks after infection and is characterized by muscle pain, dizziness, headache, and cardiac symptoms. CNS involvement occurs in about 20% of patients. Joint involvement may include the knee, ankle, and wrist. If symptoms are only in one joint, septic arthritis is part of the differential diagnosis, so clinical correlation and labs must be considered. Late disseminated infection occurs months or years after initial infection and includes neurologic and rheumatologic symptoms including meningitis, Bell’s palsy, arthritis, and dysesthesia. Knee arthritis is a key feature of this stage. Patients commonly have radicular pain and fibromyalgia-type pain. More severe disease processes include encephalomyelitis, arrhythmias, and heart block.

ECM is often a clinical diagnosis because serologic testing may not be positive during the first 2 weeks of infection. The screening serologic test is the ELISA, and a Western blot confirms the results. Skin histopathology for Lyme disease is often nonspecific and reveals a perivascular infiltrate of histiocytes, plasma cells, and lymphocytes. Silver stain or antibody testing may be used to identify the spirochete. In acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans, late Lyme disease presenting on the distal extremities, lymphocytic and plasma cell infiltrates are present. In borrelial lymphocytoma, a dense dermal lymphocytic infiltrate is present.

The standard for treatment of early localized disease is oral doxycycline in adults. Alternatives may be used if a patient is allergic or for children under 9. Disseminated disease may be treated with IV ceftriaxone and topical steroids are used if ocular symptoms are involved. Early treatment is often curative.

This patient’s antibodies were negative initially, but became positive after 6 weeks. He was treated empirically at the time of his office visit with doxycycline for 1 month.

This case and the photo were submitted by Lucas Shapiro, BS, of Nova Southeastern University College of Osteopathic Medicine, Fort Lauderdale, Fla., and Susannah Berke, MD, Three Rivers Dermatology, Coraopolis, Pa. The column was edited by Donna Bilu Martin, MD.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at MDedge.com/Dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@mdedge.com.

References

Carriveau A et al. Nurs Clin North Am. 2019 Jun;54(2):261-75.

Skar GL and Simonsen KA. Lyme Disease. [Updated 2023 May 31]. In: “StatPearls” [Internet]. Treasure Island, Fla.: StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan.

Tiger JB et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014 Oct;71(4):e133-4.

A White male presented with a 1-month history of recurrent, widespread, painful sores

Coinfection of staphylococci and streptococci can make it more challenging to treat. Lesions typically begin as a vesicle that enlarges and forms an ulcer with a hemorrhagic crust. Even with treatment, the depth of the lesions may result in scarring. Shins and dorsal feet are nearly always involved. Systemic involvement is rare.

Open wounds, bites, or dermatoses are risk factors for the development of ecthyma. Additionally, poor hygiene and malnutrition play a major role in inoculation and severity of the disease. Poor hygiene may serve as the initiating factor for infection, but malnutrition permits further development because of the body’s inability to mount a sufficient immune response. Intravenous drug users and patients with HIV tend to be affected.

When diagnosing ecthyma, it is important to correlate clinical signs with a bacterial culture. This condition can be difficult to treat because of both coinfection and growing antibiotic resistance in staphylococcal and streptococcal species. Specifically, S. aureus has been found to be resistant to beta-lactam antibiotics for many years, with methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) being first detected in 1961. While a variety of antibiotics are indicated, the prescription should be tailored to cover the cultured organism.

Topical antibiotics are sufficient for more superficial lesions. Both topical and oral antibiotics may be recommended for ecthyma as the infection can spread more deeply into the skin, eventually causing a cellulitis. Treatment protocol for oral agents varies based on which drug is indicated. This patient was seen in the emergency room. His white blood cell count was elevated at 9 × 109/L. He was started empirically on amoxicillin/clavulanate (Augmentin) and ciprofloxacin. Bacterial cultures grew out Streptococcus pyogenes.

The case and photos were submitted by Lucas Shapiro, BS, Nova Southeastern University College of Osteopathic Medicine, Fort Lauderdale, Fla., and Susannah Berke, MD, Three Rivers Dermatology, Coraopolis, Pa. Dr. Bilu Martin edited the column. Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Kwak Y et al. Infect Chemother. 2017 Dec;49(4):301-25.

2. Pereira LB. An Bras Dermatol. 2014 Mar-Apr;89(2):293-9.

3. Wasserzug O et al. Clin Infect Dis. 2009 May 1;48(9):1213-9.

Coinfection of staphylococci and streptococci can make it more challenging to treat. Lesions typically begin as a vesicle that enlarges and forms an ulcer with a hemorrhagic crust. Even with treatment, the depth of the lesions may result in scarring. Shins and dorsal feet are nearly always involved. Systemic involvement is rare.

Open wounds, bites, or dermatoses are risk factors for the development of ecthyma. Additionally, poor hygiene and malnutrition play a major role in inoculation and severity of the disease. Poor hygiene may serve as the initiating factor for infection, but malnutrition permits further development because of the body’s inability to mount a sufficient immune response. Intravenous drug users and patients with HIV tend to be affected.

When diagnosing ecthyma, it is important to correlate clinical signs with a bacterial culture. This condition can be difficult to treat because of both coinfection and growing antibiotic resistance in staphylococcal and streptococcal species. Specifically, S. aureus has been found to be resistant to beta-lactam antibiotics for many years, with methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) being first detected in 1961. While a variety of antibiotics are indicated, the prescription should be tailored to cover the cultured organism.

Topical antibiotics are sufficient for more superficial lesions. Both topical and oral antibiotics may be recommended for ecthyma as the infection can spread more deeply into the skin, eventually causing a cellulitis. Treatment protocol for oral agents varies based on which drug is indicated. This patient was seen in the emergency room. His white blood cell count was elevated at 9 × 109/L. He was started empirically on amoxicillin/clavulanate (Augmentin) and ciprofloxacin. Bacterial cultures grew out Streptococcus pyogenes.

The case and photos were submitted by Lucas Shapiro, BS, Nova Southeastern University College of Osteopathic Medicine, Fort Lauderdale, Fla., and Susannah Berke, MD, Three Rivers Dermatology, Coraopolis, Pa. Dr. Bilu Martin edited the column. Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Kwak Y et al. Infect Chemother. 2017 Dec;49(4):301-25.

2. Pereira LB. An Bras Dermatol. 2014 Mar-Apr;89(2):293-9.

3. Wasserzug O et al. Clin Infect Dis. 2009 May 1;48(9):1213-9.

Coinfection of staphylococci and streptococci can make it more challenging to treat. Lesions typically begin as a vesicle that enlarges and forms an ulcer with a hemorrhagic crust. Even with treatment, the depth of the lesions may result in scarring. Shins and dorsal feet are nearly always involved. Systemic involvement is rare.

Open wounds, bites, or dermatoses are risk factors for the development of ecthyma. Additionally, poor hygiene and malnutrition play a major role in inoculation and severity of the disease. Poor hygiene may serve as the initiating factor for infection, but malnutrition permits further development because of the body’s inability to mount a sufficient immune response. Intravenous drug users and patients with HIV tend to be affected.

When diagnosing ecthyma, it is important to correlate clinical signs with a bacterial culture. This condition can be difficult to treat because of both coinfection and growing antibiotic resistance in staphylococcal and streptococcal species. Specifically, S. aureus has been found to be resistant to beta-lactam antibiotics for many years, with methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) being first detected in 1961. While a variety of antibiotics are indicated, the prescription should be tailored to cover the cultured organism.

Topical antibiotics are sufficient for more superficial lesions. Both topical and oral antibiotics may be recommended for ecthyma as the infection can spread more deeply into the skin, eventually causing a cellulitis. Treatment protocol for oral agents varies based on which drug is indicated. This patient was seen in the emergency room. His white blood cell count was elevated at 9 × 109/L. He was started empirically on amoxicillin/clavulanate (Augmentin) and ciprofloxacin. Bacterial cultures grew out Streptococcus pyogenes.

The case and photos were submitted by Lucas Shapiro, BS, Nova Southeastern University College of Osteopathic Medicine, Fort Lauderdale, Fla., and Susannah Berke, MD, Three Rivers Dermatology, Coraopolis, Pa. Dr. Bilu Martin edited the column. Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Kwak Y et al. Infect Chemother. 2017 Dec;49(4):301-25.

2. Pereira LB. An Bras Dermatol. 2014 Mar-Apr;89(2):293-9.

3. Wasserzug O et al. Clin Infect Dis. 2009 May 1;48(9):1213-9.

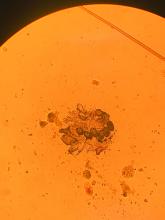

75-year-old White male presenting with progressive pruritus and a worsening rash

, although it can also be contracted through contaminated bedding and clothing. It can affect all races and ages.

Patients typically present with extremely pruritic, symmetric papules and excoriations. In nodular scabies, nodules and large papules are seen on exam. Thin lines in the skin called burrows may be present, especially in the webs between fingers. Female mites create burrows as they tunnel through the epidermis and lay eggs. The wrists, areola, waistline, and groin may all be involved, creating an imaginary circle between the areas described as the “circle of Hebra.” Penile and scrotal lesions are common in men.

Patients usually experience worse pruritus at night, which disturbs sleep. Crusted scabies is a severe form of scabies more often seen in those with immunocompromised immune systems. Clinically, thick crusted and scaly patches are present that are teeming with mites.

Diagnosis can be confirmed by performing a scabies prep, during which a burrow is scraped with a surgical blade. A drop of mineral oil is placed on the skin cells. The mite, ova, and feces can be visualized under the microscope. Wrists and hands usually have the highest yield for finding the parasites.

Topical treatments include permethrin 5% cream, lindane, benzyl benzoate, and crotamiton, and should be applied as two treatments a week apart. In the United States, permethrin is most commonly used. Ivermectin pills are used off label and are very effective and may be repeated for 1-2 weeks. All household contacts should be treated. Patients may still have pruritus for 2-4 weeks following treatment.

In this patient, a scabies prep was performed prior to performing repeat skin biopsies. Microscopic examination revealed ova, one mite, and feces. Treatment was initiated with ivermectin and permethrin.

Photos and case were submitted by Susannah Berke, MD, and Damon McClain, MD, Three Rivers Dermatology, Coraopolis, Pa.; and Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@mdedge.com.

, although it can also be contracted through contaminated bedding and clothing. It can affect all races and ages.

Patients typically present with extremely pruritic, symmetric papules and excoriations. In nodular scabies, nodules and large papules are seen on exam. Thin lines in the skin called burrows may be present, especially in the webs between fingers. Female mites create burrows as they tunnel through the epidermis and lay eggs. The wrists, areola, waistline, and groin may all be involved, creating an imaginary circle between the areas described as the “circle of Hebra.” Penile and scrotal lesions are common in men.

Patients usually experience worse pruritus at night, which disturbs sleep. Crusted scabies is a severe form of scabies more often seen in those with immunocompromised immune systems. Clinically, thick crusted and scaly patches are present that are teeming with mites.

Diagnosis can be confirmed by performing a scabies prep, during which a burrow is scraped with a surgical blade. A drop of mineral oil is placed on the skin cells. The mite, ova, and feces can be visualized under the microscope. Wrists and hands usually have the highest yield for finding the parasites.

Topical treatments include permethrin 5% cream, lindane, benzyl benzoate, and crotamiton, and should be applied as two treatments a week apart. In the United States, permethrin is most commonly used. Ivermectin pills are used off label and are very effective and may be repeated for 1-2 weeks. All household contacts should be treated. Patients may still have pruritus for 2-4 weeks following treatment.

In this patient, a scabies prep was performed prior to performing repeat skin biopsies. Microscopic examination revealed ova, one mite, and feces. Treatment was initiated with ivermectin and permethrin.

Photos and case were submitted by Susannah Berke, MD, and Damon McClain, MD, Three Rivers Dermatology, Coraopolis, Pa.; and Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@mdedge.com.

, although it can also be contracted through contaminated bedding and clothing. It can affect all races and ages.

Patients typically present with extremely pruritic, symmetric papules and excoriations. In nodular scabies, nodules and large papules are seen on exam. Thin lines in the skin called burrows may be present, especially in the webs between fingers. Female mites create burrows as they tunnel through the epidermis and lay eggs. The wrists, areola, waistline, and groin may all be involved, creating an imaginary circle between the areas described as the “circle of Hebra.” Penile and scrotal lesions are common in men.

Patients usually experience worse pruritus at night, which disturbs sleep. Crusted scabies is a severe form of scabies more often seen in those with immunocompromised immune systems. Clinically, thick crusted and scaly patches are present that are teeming with mites.

Diagnosis can be confirmed by performing a scabies prep, during which a burrow is scraped with a surgical blade. A drop of mineral oil is placed on the skin cells. The mite, ova, and feces can be visualized under the microscope. Wrists and hands usually have the highest yield for finding the parasites.

Topical treatments include permethrin 5% cream, lindane, benzyl benzoate, and crotamiton, and should be applied as two treatments a week apart. In the United States, permethrin is most commonly used. Ivermectin pills are used off label and are very effective and may be repeated for 1-2 weeks. All household contacts should be treated. Patients may still have pruritus for 2-4 weeks following treatment.

In this patient, a scabies prep was performed prior to performing repeat skin biopsies. Microscopic examination revealed ova, one mite, and feces. Treatment was initiated with ivermectin and permethrin.

Photos and case were submitted by Susannah Berke, MD, and Damon McClain, MD, Three Rivers Dermatology, Coraopolis, Pa.; and Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@mdedge.com.

A 70-year-old man presents with firm papules on his hand and fingers

, although women are more often affected than men. GA most commonly appears in the first 3 decades of life. Although the etiology is not known, GA may represent a delayed hypersensitivity reaction. A link between GA and diabetes mellitus, autoimmune thyroiditis, dyslipidemia, and rarely, malignancy may exist.

GA is most commonly localized, presenting as an asymptomatic, erythematous, annular plaque with a firm border and central clearing localized to the wrists, ankles, and dorsal hands or feet. This form is the type most often seen in children. Generalized GA is far less common and presents later in life as multiple asymptomatic or pruritic papules and plaques on the trunk and extremities. Less common variants include subcutaneous GA, patch GA, atypical GA, and perforating GA. Perforating GA occurs on the dorsal hands and presents as (umbilicated) papules, and seems consistent with this patient’s clinical presentation. Histologically, transepidermal elimination of collagen is typically seen in perforating GA.1

Histology in this patient’s biopsy revealed a granulomatous dermatitis consistent with granuloma annulare. A palisaded arrangement of histiocytic cells surrounding altered collagen with increased dermal mucin was seen. There was associated perivascular mononuclear inflammatory infiltrates. The overlying epidermis was unremarkable.

Granuloma annulare often spontaneously resolves without sequelae. In some cases, atrophy may result. Lesions may also recur. Localized GA is often treated with high-potency topical corticosteroids or intralesional corticosteroids. For generalized GA, topical or intralesional corticosteroids may be used for select lesions. Topical calcineurin inhibitors, light therapy, cryotherapy, imiquimod, hydroxychloroquine, isotretinoin, and dapsone have also been reported in the literature as possible treatments.

This case and photo were provided by Dr. Berke, of Three Rivers Dermatology, Pittsburgh, and Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@mdedge.com.

References

1 Alves J, Barreiros H, Bartolo E. Healthcare (Basel). 2014 Sep 4;2(3):338-45.

2. Bolognia J et al. Dermatology (St. Louis: Mosby/Elsevier, 2008).

3. “Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin,” 13th ed. James W et al. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier, 2006.

, although women are more often affected than men. GA most commonly appears in the first 3 decades of life. Although the etiology is not known, GA may represent a delayed hypersensitivity reaction. A link between GA and diabetes mellitus, autoimmune thyroiditis, dyslipidemia, and rarely, malignancy may exist.

GA is most commonly localized, presenting as an asymptomatic, erythematous, annular plaque with a firm border and central clearing localized to the wrists, ankles, and dorsal hands or feet. This form is the type most often seen in children. Generalized GA is far less common and presents later in life as multiple asymptomatic or pruritic papules and plaques on the trunk and extremities. Less common variants include subcutaneous GA, patch GA, atypical GA, and perforating GA. Perforating GA occurs on the dorsal hands and presents as (umbilicated) papules, and seems consistent with this patient’s clinical presentation. Histologically, transepidermal elimination of collagen is typically seen in perforating GA.1

Histology in this patient’s biopsy revealed a granulomatous dermatitis consistent with granuloma annulare. A palisaded arrangement of histiocytic cells surrounding altered collagen with increased dermal mucin was seen. There was associated perivascular mononuclear inflammatory infiltrates. The overlying epidermis was unremarkable.

Granuloma annulare often spontaneously resolves without sequelae. In some cases, atrophy may result. Lesions may also recur. Localized GA is often treated with high-potency topical corticosteroids or intralesional corticosteroids. For generalized GA, topical or intralesional corticosteroids may be used for select lesions. Topical calcineurin inhibitors, light therapy, cryotherapy, imiquimod, hydroxychloroquine, isotretinoin, and dapsone have also been reported in the literature as possible treatments.

This case and photo were provided by Dr. Berke, of Three Rivers Dermatology, Pittsburgh, and Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@mdedge.com.

References

1 Alves J, Barreiros H, Bartolo E. Healthcare (Basel). 2014 Sep 4;2(3):338-45.

2. Bolognia J et al. Dermatology (St. Louis: Mosby/Elsevier, 2008).

3. “Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin,” 13th ed. James W et al. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier, 2006.

, although women are more often affected than men. GA most commonly appears in the first 3 decades of life. Although the etiology is not known, GA may represent a delayed hypersensitivity reaction. A link between GA and diabetes mellitus, autoimmune thyroiditis, dyslipidemia, and rarely, malignancy may exist.

GA is most commonly localized, presenting as an asymptomatic, erythematous, annular plaque with a firm border and central clearing localized to the wrists, ankles, and dorsal hands or feet. This form is the type most often seen in children. Generalized GA is far less common and presents later in life as multiple asymptomatic or pruritic papules and plaques on the trunk and extremities. Less common variants include subcutaneous GA, patch GA, atypical GA, and perforating GA. Perforating GA occurs on the dorsal hands and presents as (umbilicated) papules, and seems consistent with this patient’s clinical presentation. Histologically, transepidermal elimination of collagen is typically seen in perforating GA.1

Histology in this patient’s biopsy revealed a granulomatous dermatitis consistent with granuloma annulare. A palisaded arrangement of histiocytic cells surrounding altered collagen with increased dermal mucin was seen. There was associated perivascular mononuclear inflammatory infiltrates. The overlying epidermis was unremarkable.

Granuloma annulare often spontaneously resolves without sequelae. In some cases, atrophy may result. Lesions may also recur. Localized GA is often treated with high-potency topical corticosteroids or intralesional corticosteroids. For generalized GA, topical or intralesional corticosteroids may be used for select lesions. Topical calcineurin inhibitors, light therapy, cryotherapy, imiquimod, hydroxychloroquine, isotretinoin, and dapsone have also been reported in the literature as possible treatments.

This case and photo were provided by Dr. Berke, of Three Rivers Dermatology, Pittsburgh, and Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@mdedge.com.

References

1 Alves J, Barreiros H, Bartolo E. Healthcare (Basel). 2014 Sep 4;2(3):338-45.

2. Bolognia J et al. Dermatology (St. Louis: Mosby/Elsevier, 2008).

3. “Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin,” 13th ed. James W et al. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier, 2006.