User login

Efficacy, Safety, and Tolerability of Halobetasol Propionate 0.01%–Tazarotene 0.045% Lotion for Moderate to Severe Plaque Psoriasis in the Hispanic Population: Post Hoc Analysis

Psoriasis is a common chronic inflammatory disease affecting a diverse patient population, yet epidemiological and clinical data related to psoriasis in patients with skin of color are sparse. The Hispanic ethnic group includes a broad range of skin types and cultures. Prevalence of psoriasis in a Hispanic population has been reported as lower than in a white population1; however, these data may be influenced by the finding that Hispanic patients are less likely to see a dermatologist when they have skin problems.2 In addition, socioeconomic disparities and cultural variations among racial/ethnic groups may contribute to differences in access to care and thresholds for seeking care,3 leading to a tendency for more severe disease in skin of color and Hispanic ethnic groups.4,5 Greater impairments in health-related quality of life have been reported in patients with skin of color and Hispanic racial/ethnic groups compared to white patients, independent of psoriasis severity.4,6 Postinflammatory pigment alteration at the sites of resolving lesions, a common clinical feature in skin of color, may contribute to the impact of psoriasis on quality of life in patients with skin of color. Psoriasis in darker skin types also can present diagnostic challenges due to overlapping features with other papulosquamous disorders and less conspicuous erythema.7

We present a post hoc analysis of the treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis with a novel fixed-combination halobetasol propionate (HP) 0.01%–tazarotene (TAZ) 0.045% lotion in a Hispanic patient population. Historically, clinical trials for psoriasis have enrolled low proportions of Hispanic patients and other patients with skin of color; in this analysis, the Hispanic population (115/418) represented 28% of the total study population and provided valuable insights.

Methods

Study Design

Two phase 3 randomized controlled trials were conducted to demonstrate the efficacy and safety of HP/TAZ lotion. Patients with a clinical diagnosis of moderate or severe localized psoriasis (N=418) were randomized to receive HP/TAZ lotion or vehicle (2:1 ratio) once daily for 8 weeks with a 4-week posttreatment follow-up.8,9 A post hoc analysis was conducted on data of the self-identified Hispanic population.

Assessments

Efficacy assessments included treatment success (at least a 2-grade improvement from baseline in the investigator global assessment [IGA] and a score of clear or almost clear) and impact on individual signs of psoriasis (at least a 2-grade improvement in erythema, plaque elevation, and scaling) at the target lesion. In addition, reduction in body surface area (BSA) was recorded, and an IGA×BSA score was calculated by multiplying IGA by BSA at each timepoint for each individual patient. A clinically meaningful improvement in disease severity (percentage of patients achieving a 75% reduction in IGA×BSA [IGA×BSA-75]) also was calculated.

Information on reported and observed adverse events (AEs) was obtained at each visit. The safety population included 112 participants (76 in the HP/TAZ group and 36 in the vehicle group).

Statistical Analysis

The statistical and analytical plan is detailed elsewhere9 and relevant to this post hoc analysis. No statistical analysis was carried out to compare data in the Hispanic population with either the overall study population or the non-Hispanic population.

Results

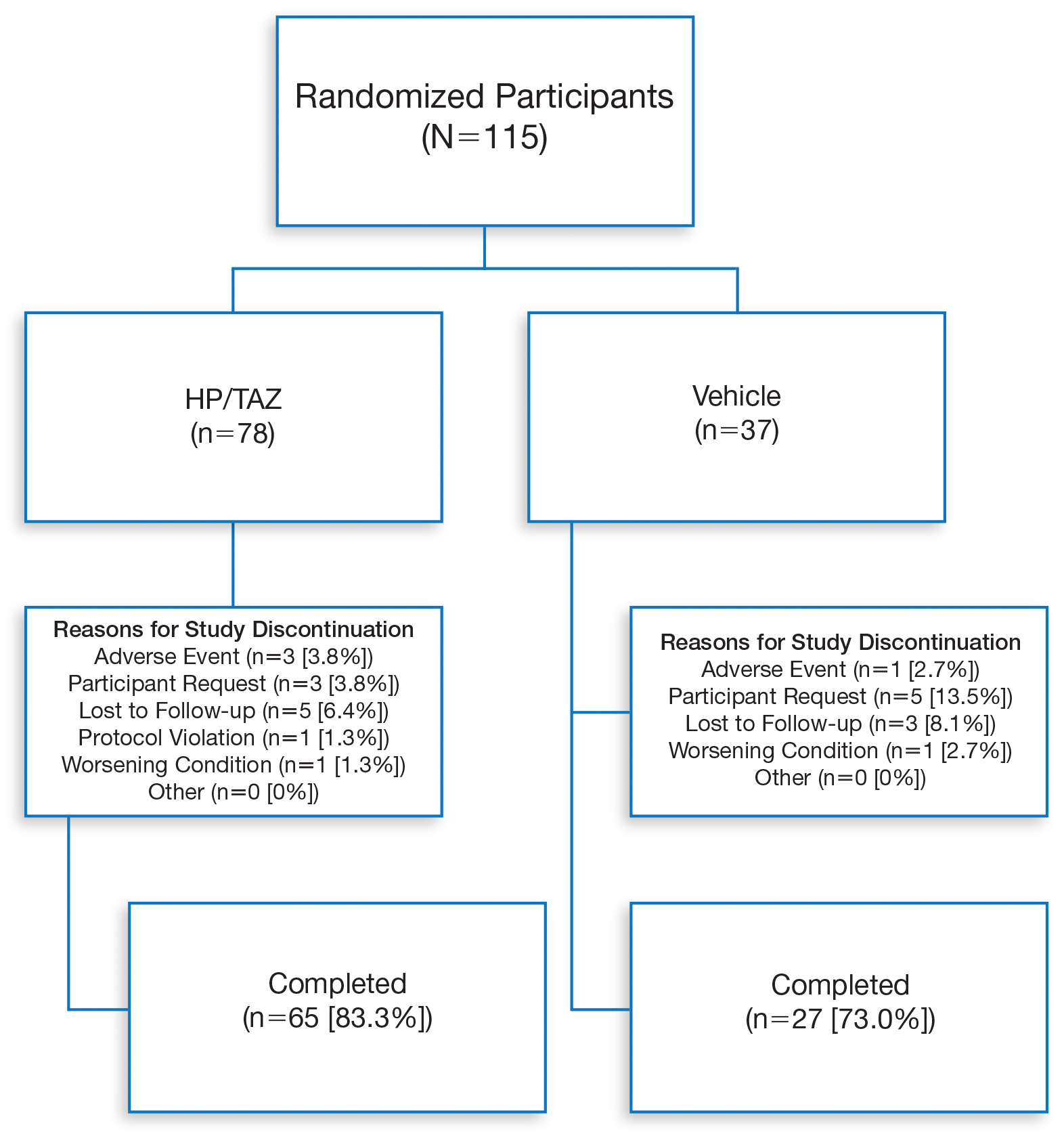

Overall, 115 Hispanic patients (27.5%) were enrolled (eFigure). Patients had a mean (standard deviation [SD]) age of 46.7 (13.12) years, and more than two-thirds were male (n=80, 69.6%).

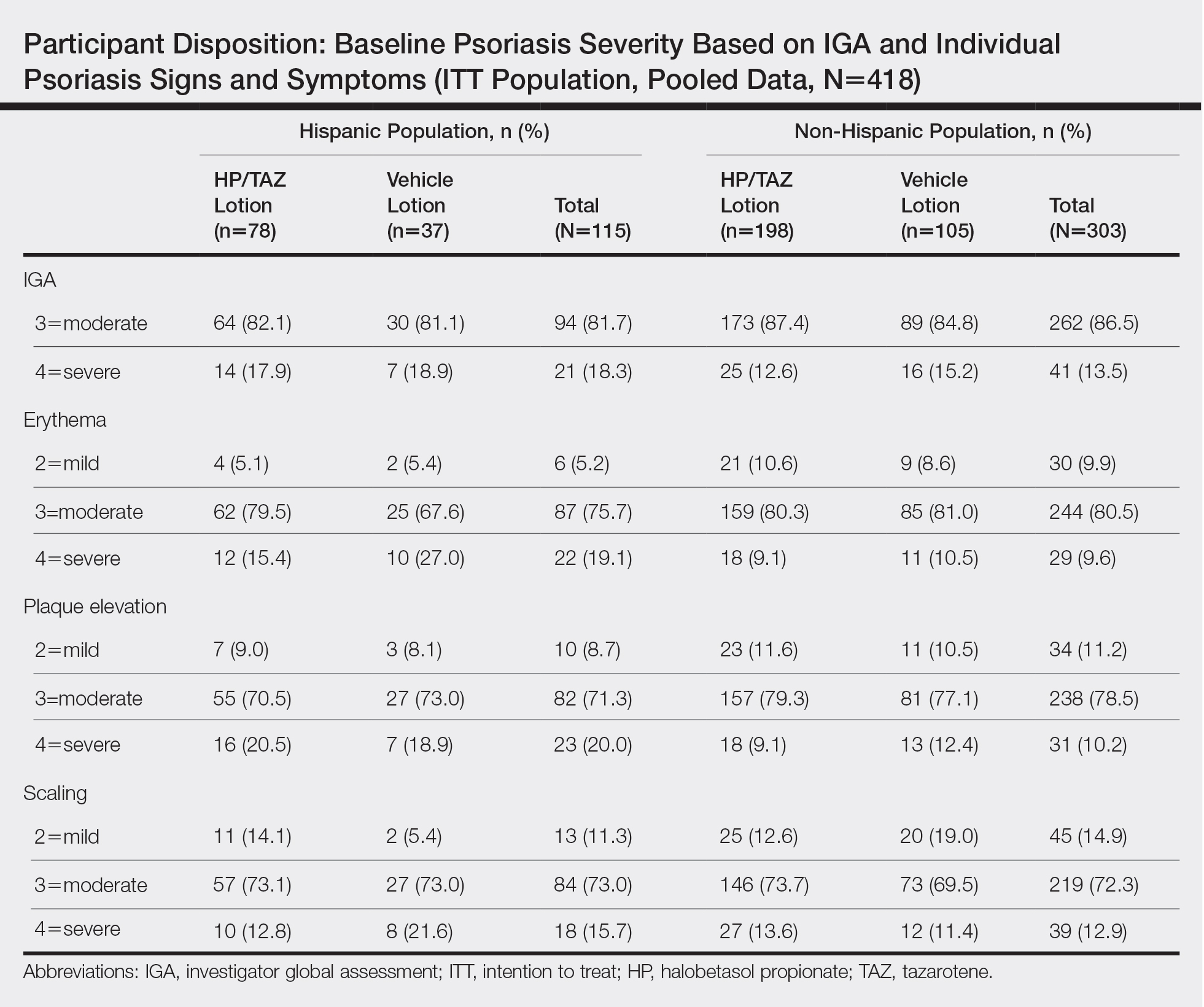

Overall completion rates (80.0%) for Hispanic patients were similar to those in the overall study population, though there were more discontinuations in the vehicle group. The main reasons for treatment discontinuation among Hispanic patients were participant request (n=8, 7.0%), lost to follow-up (n=8, 7.0%), and AEs (n=4, 3.5%). Hispanic patients in this study had more severe disease—18.3% (n=21) had an IGA score of 4 compared to 13.5% (n=41) of non-Hispanic patients—and more severe erythema (19.1% vs 9.6%), plaque elevation (20.0% vs 10.2%), and scaling (15.7% vs 12.9%) compared to the non-Hispanic populations (Table).

Efficacy of HP/TAZ lotion in Hispanic patients was similar to the overall study populations,9 though maintenance of effect posttreatment appeared to be better. The incidence of treatment-related AEs also was lower.

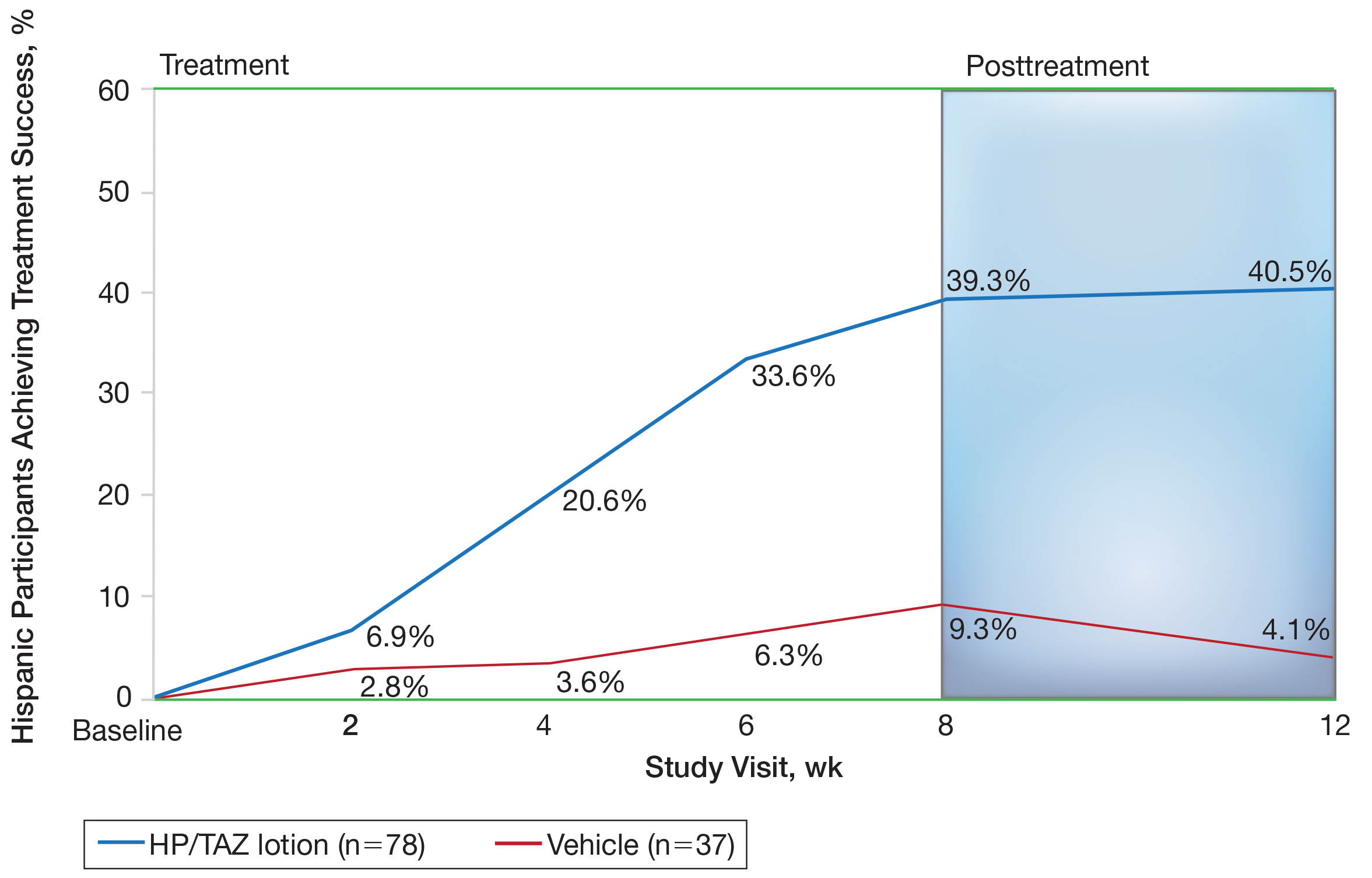

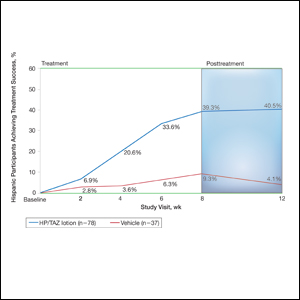

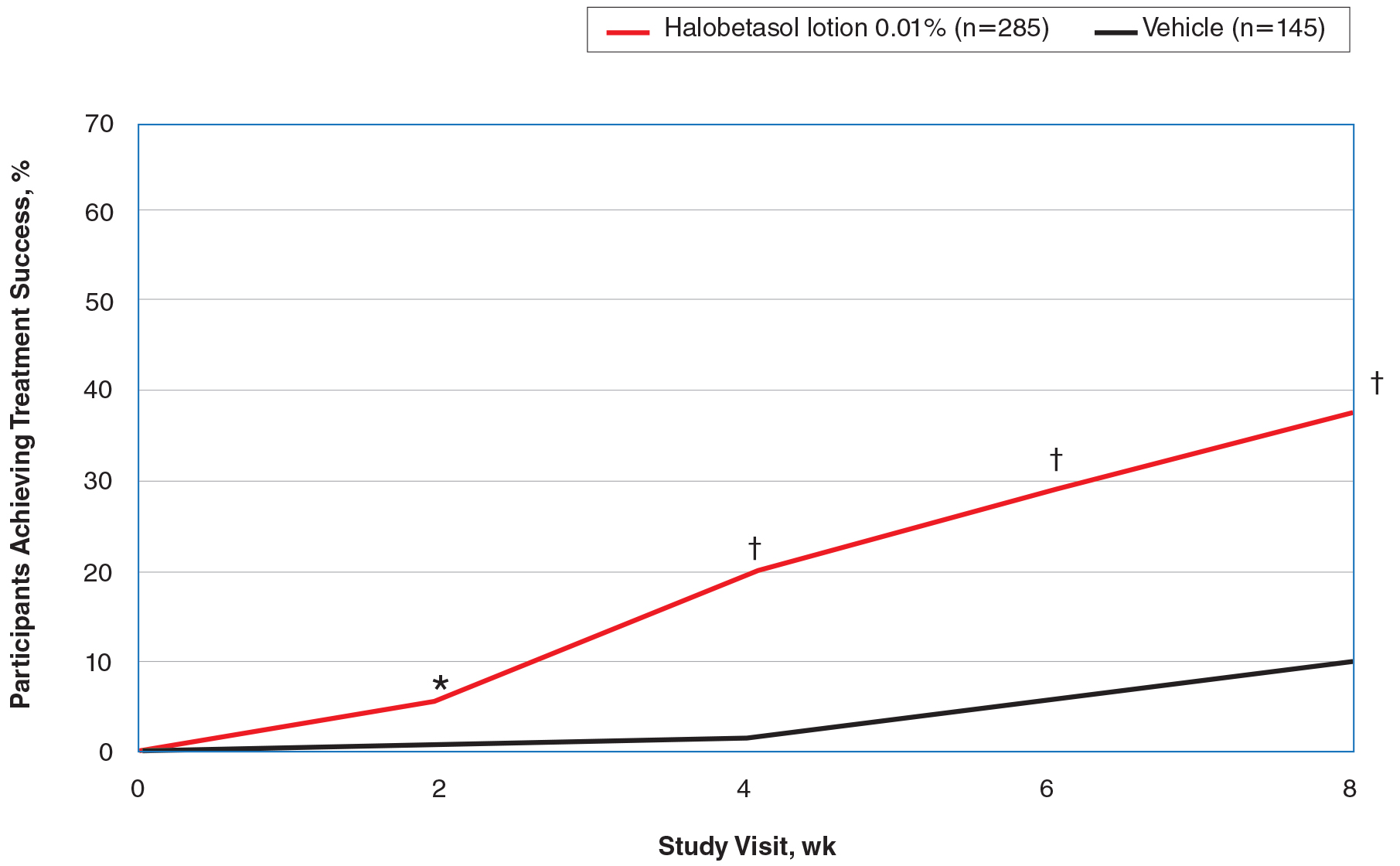

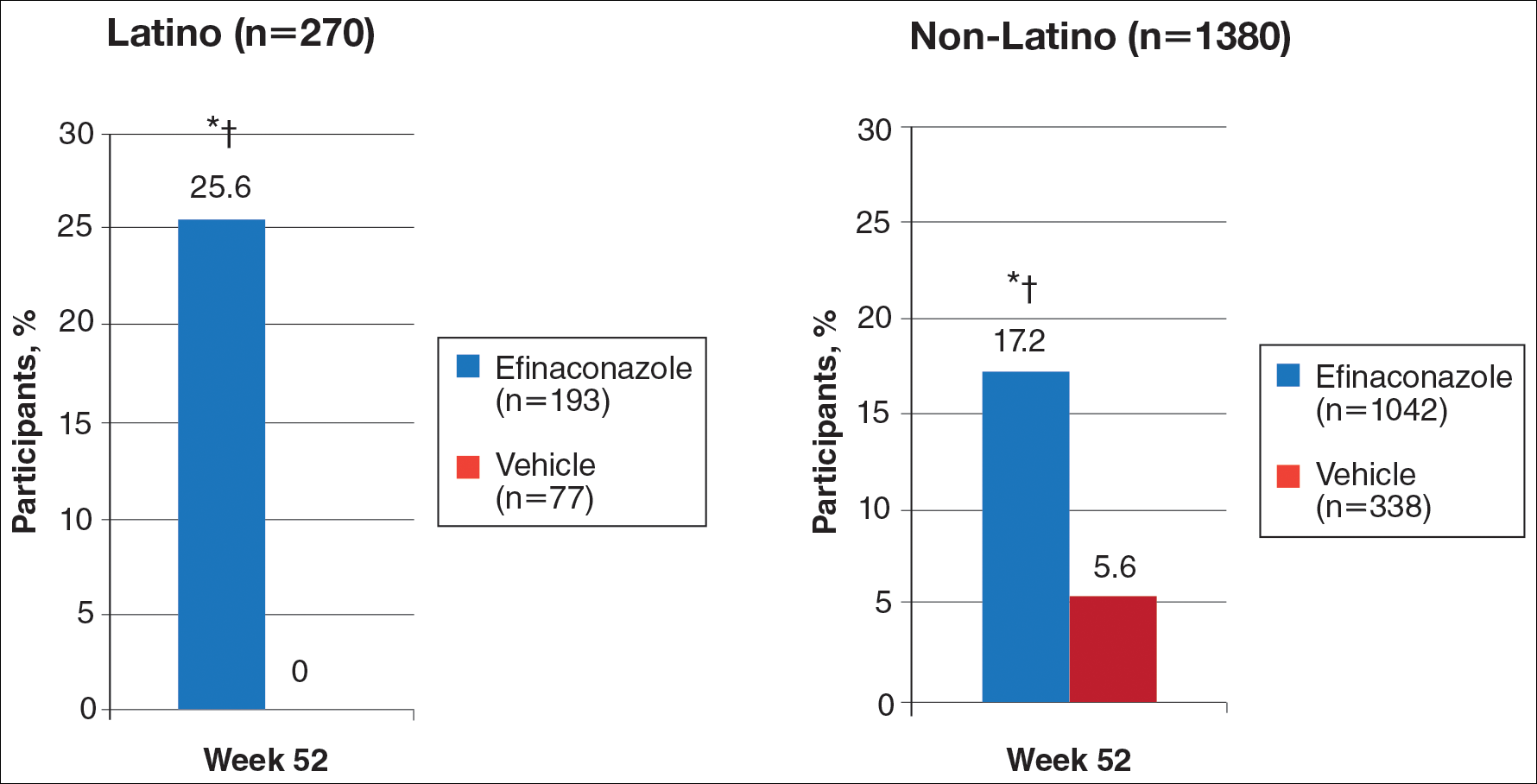

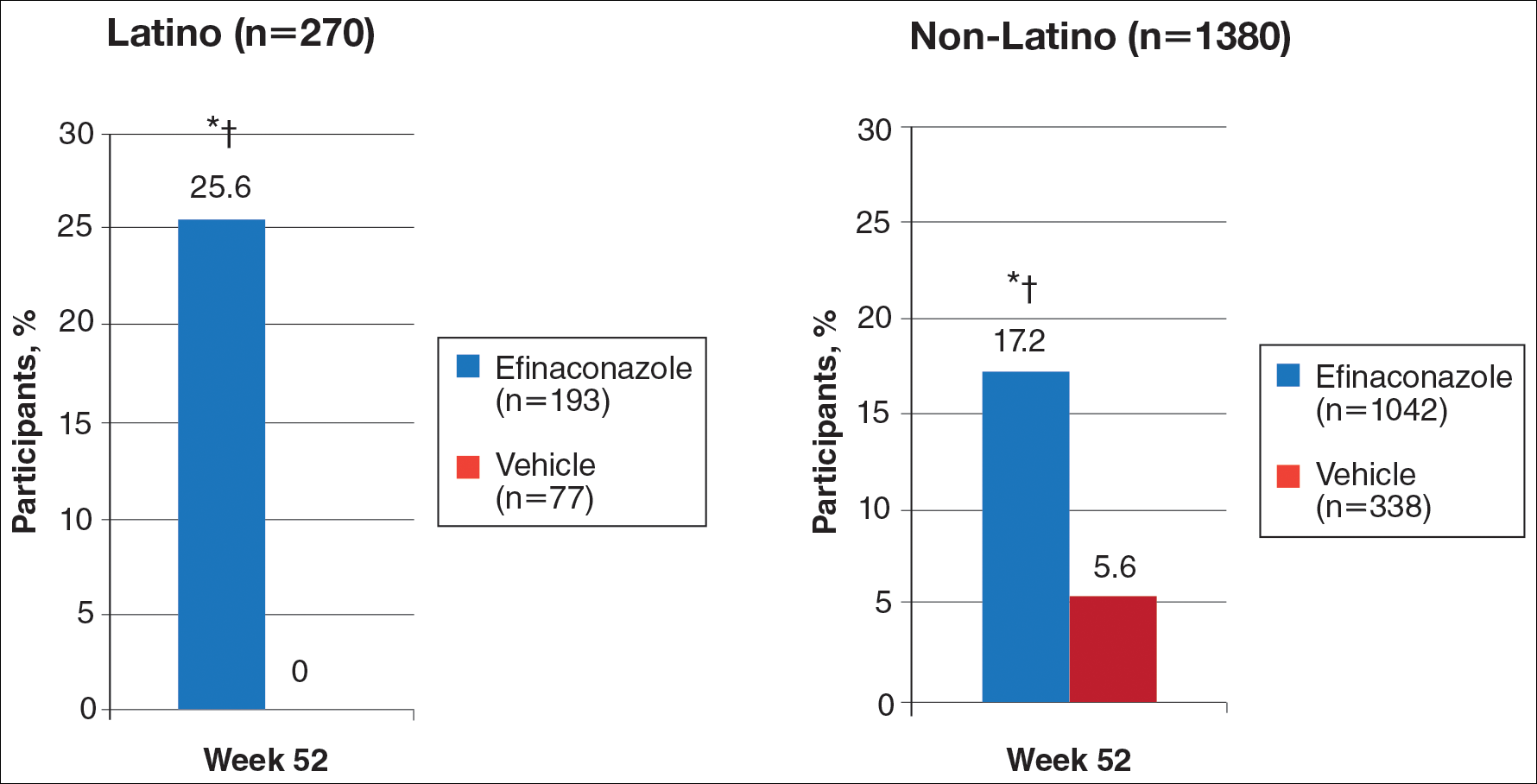

Halobetasol propionate 0.01%–TAZ 0.045% lotion demonstrated statistically significant superiority based on treatment success compared to vehicle as early as week 4 (P=.034). By week 8, 39.3% of participants treated with HP/TAZ lotion achieved treatment success compared to 9.3% of participants in the vehicle group (P=.002)(Figure 1). Treatment success was maintained over the 4-week posttreatment period, whereby 40.5% of the HP/TAZ-treated participants were treatment successes at week 12 compared to only 4.1% of participants in the vehicle group (P<.001).

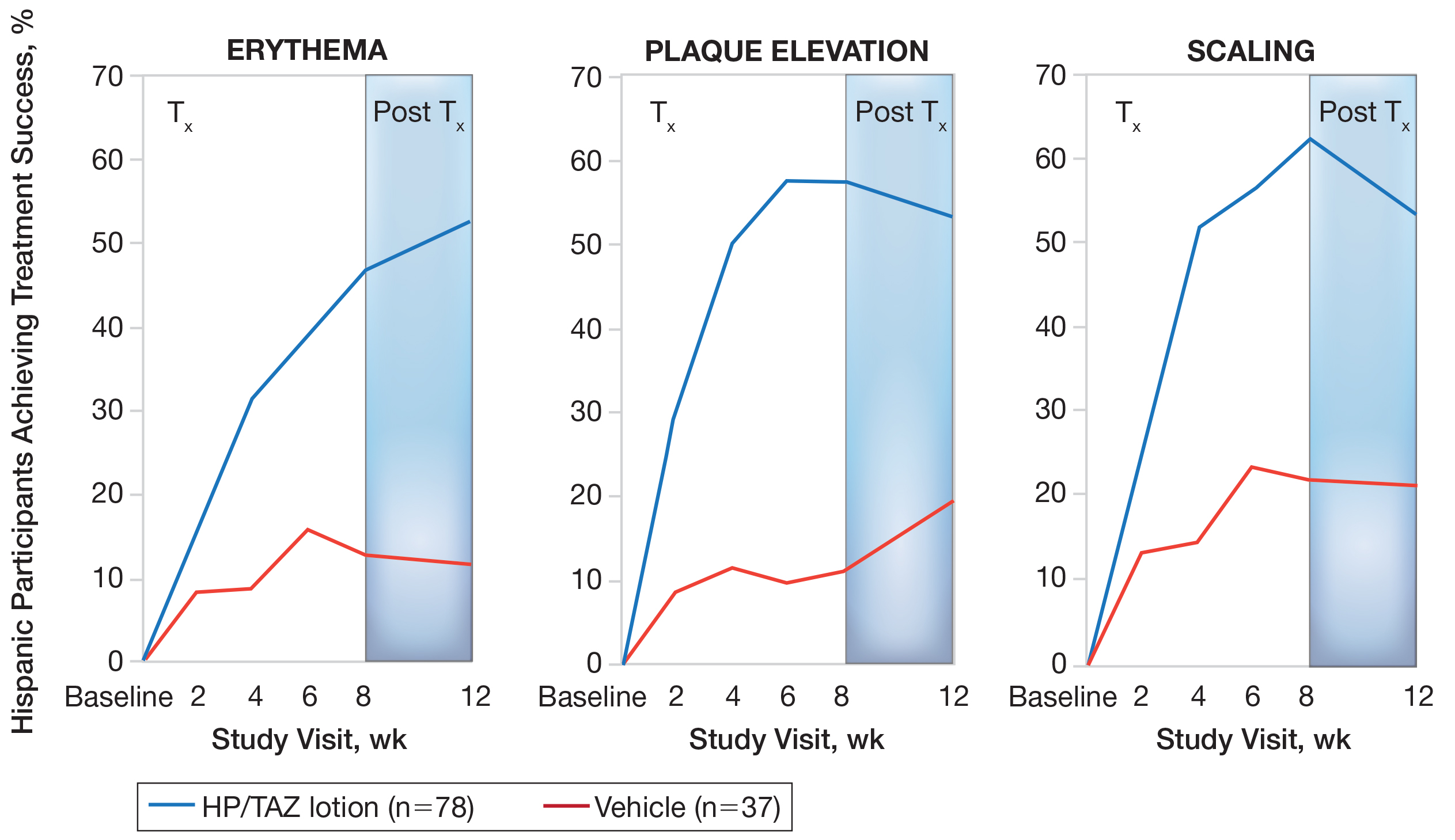

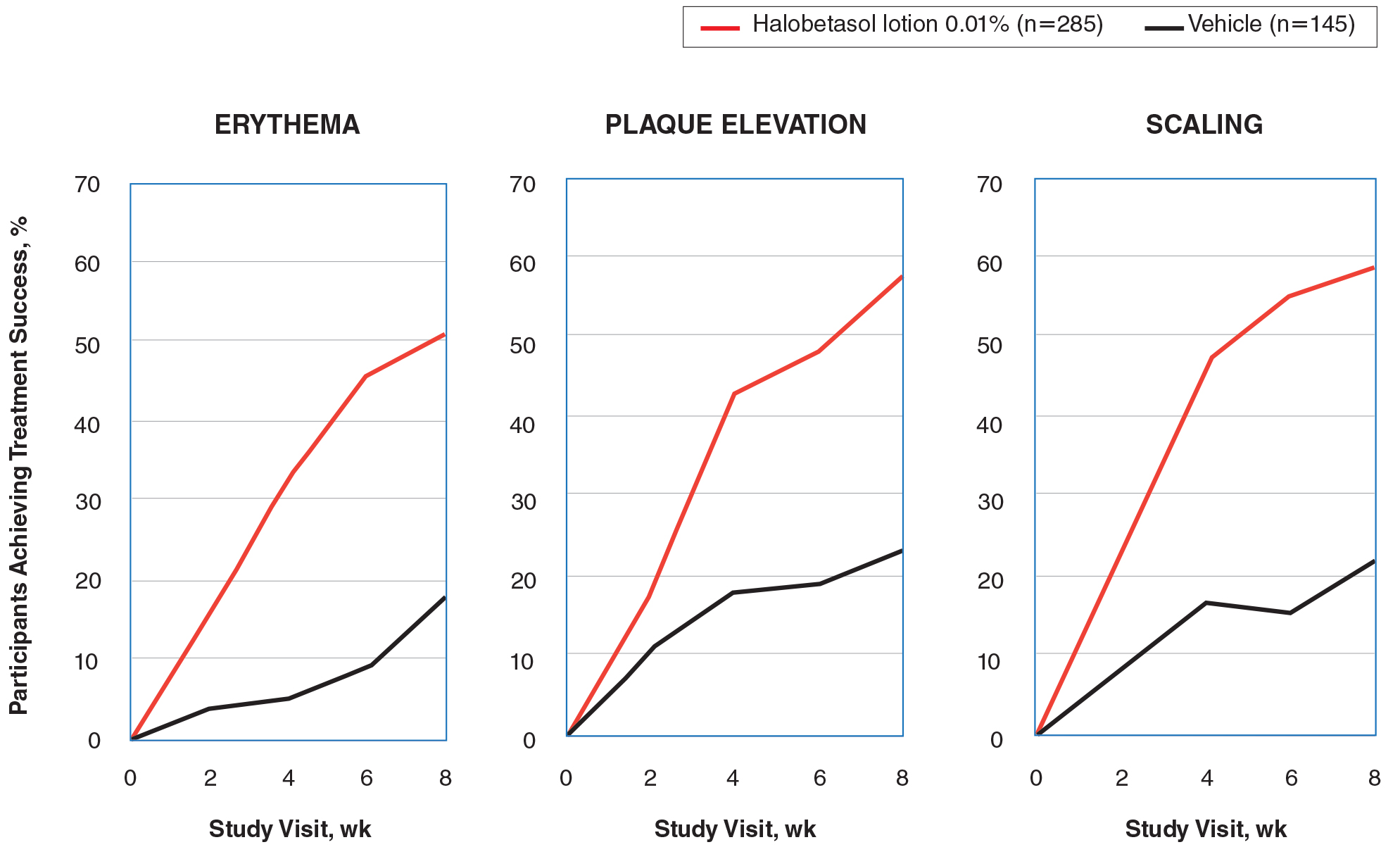

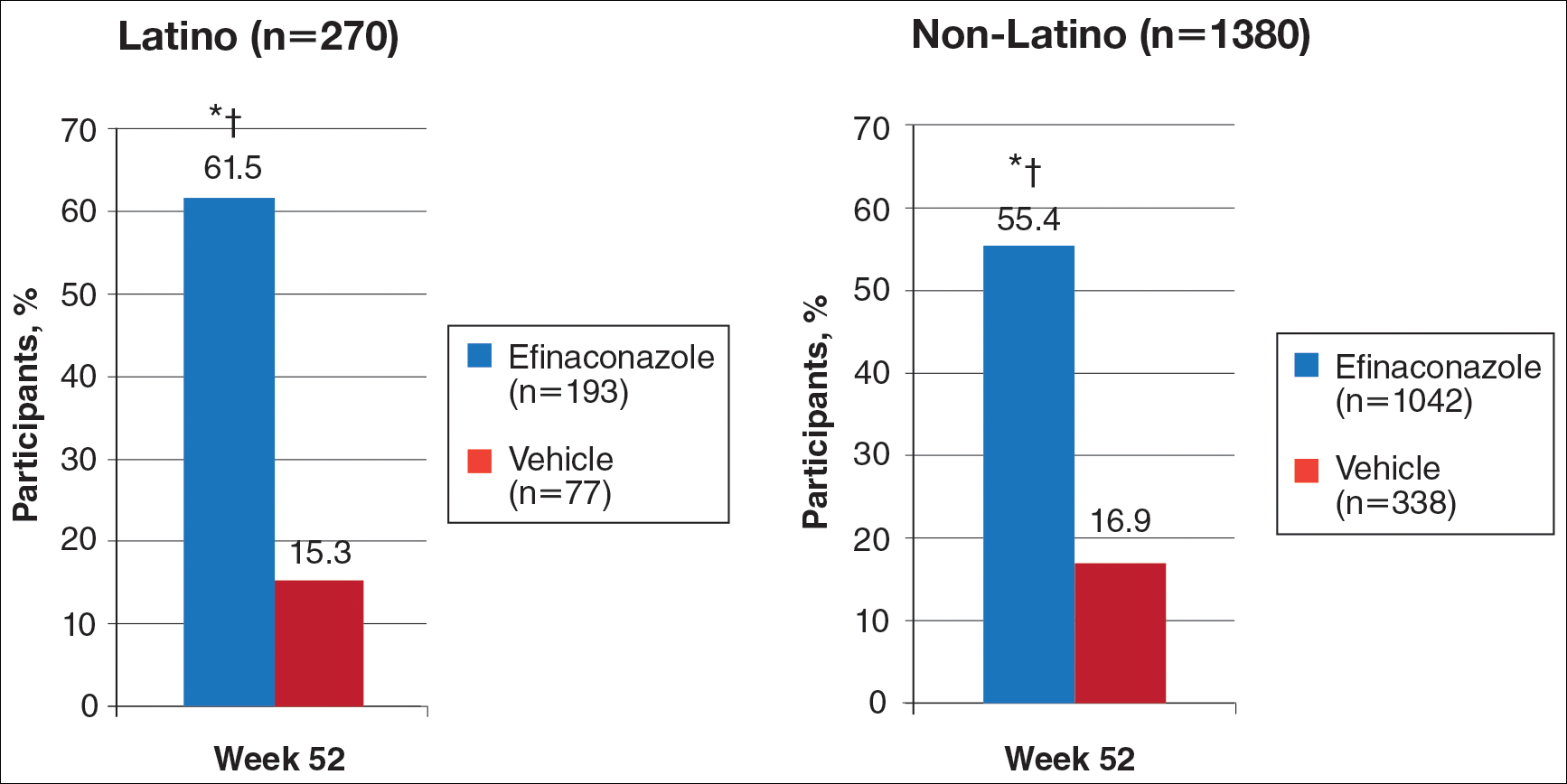

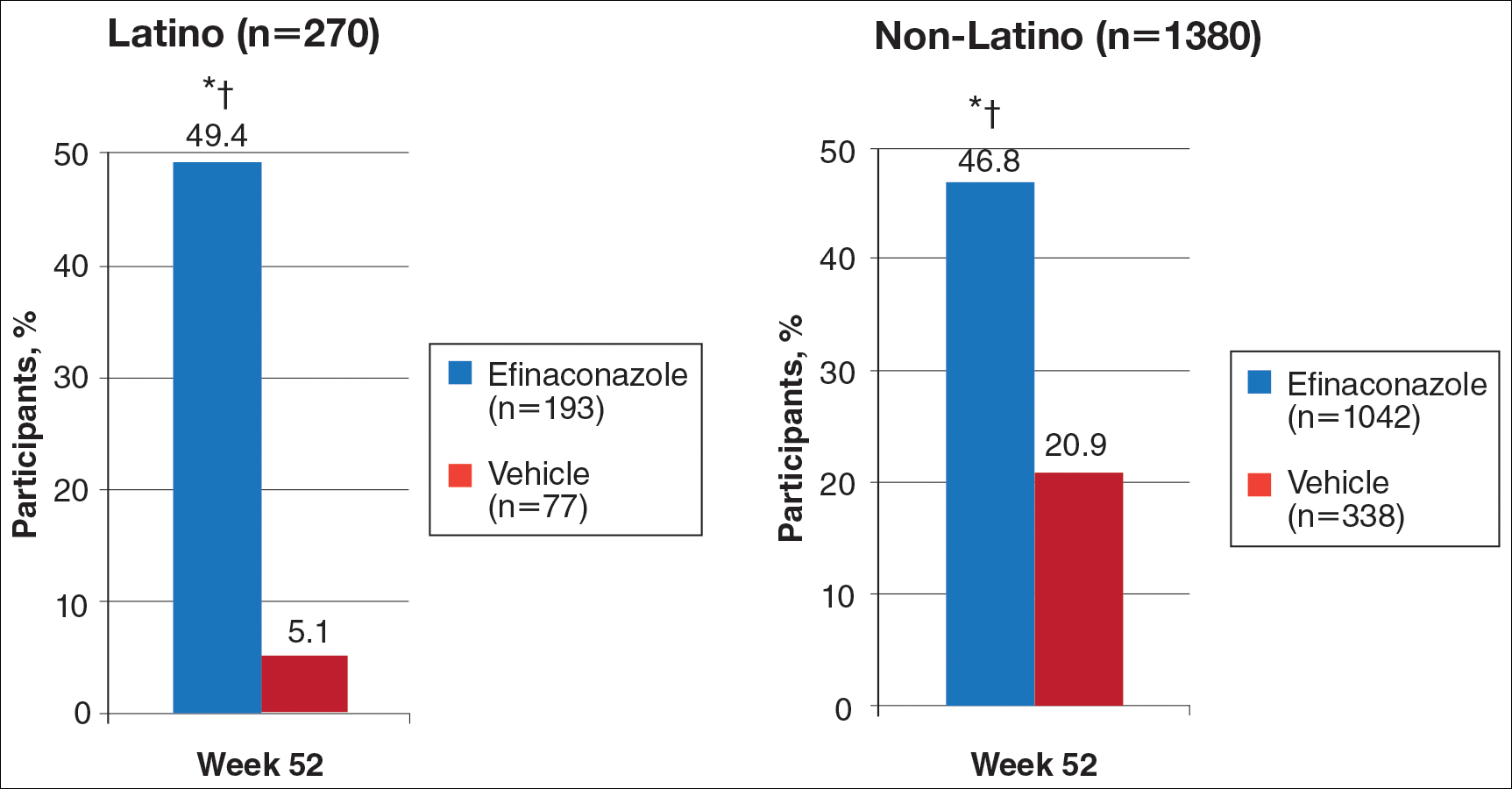

Improvements in psoriasis signs and symptoms at the target lesion were statistically significant compared to vehicle from week 2 (plaque elevation, P=.018) or week 4 (erythema, P=.004; scaling, P<.001)(Figure 2). By week 8, 46.8%, 58.1%, and 63.2% of participants showed at least a 2-grade improvement from baseline and were therefore treatment successes for erythema, plaque elevation, and scaling, respectively (all statistically significant [P<.001] compared to vehicle). The number of participants who achieved at least a 2-grade improvement in erythema with HP/TAZ lotion increased posttreatment from 46.8% to 53.0%.

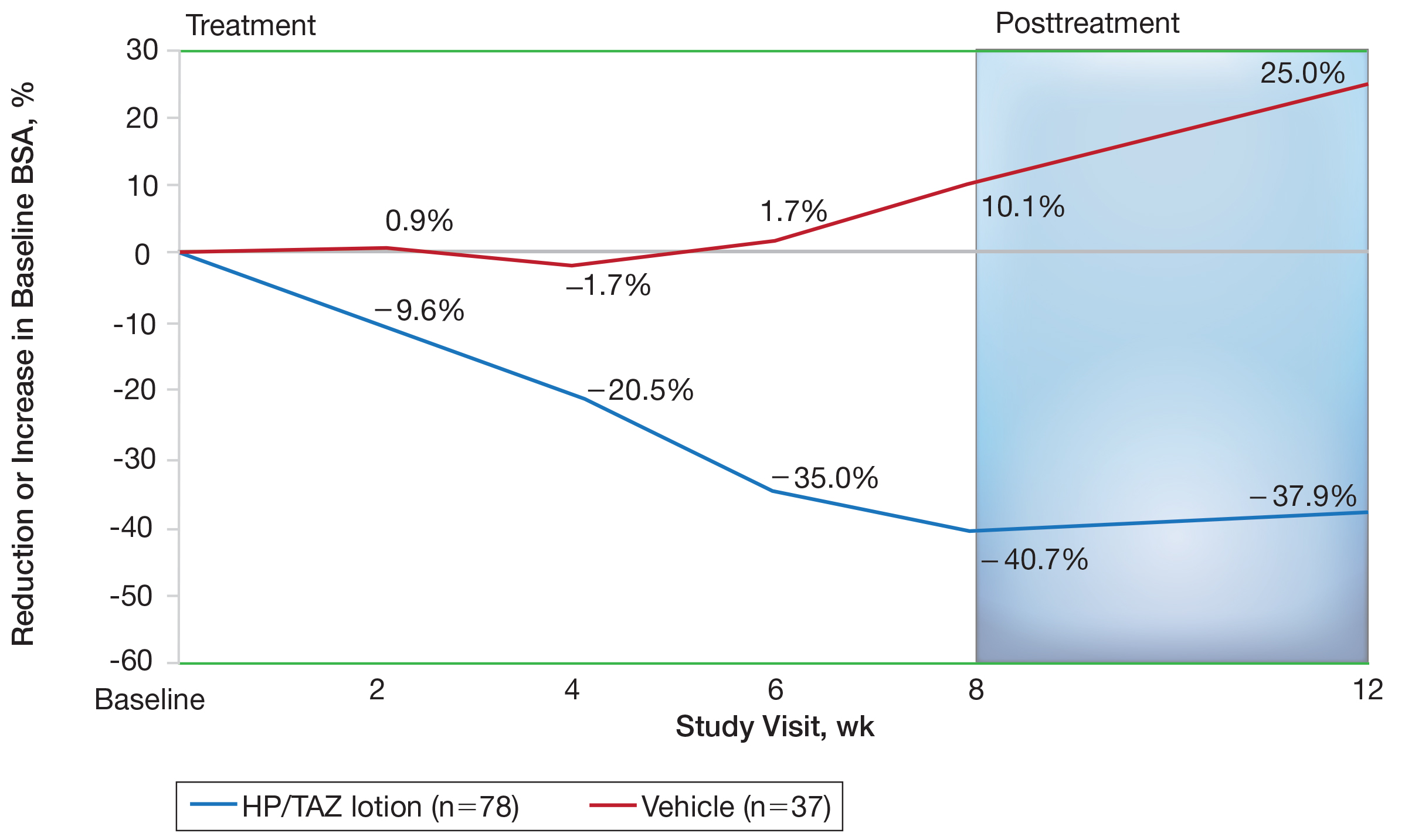

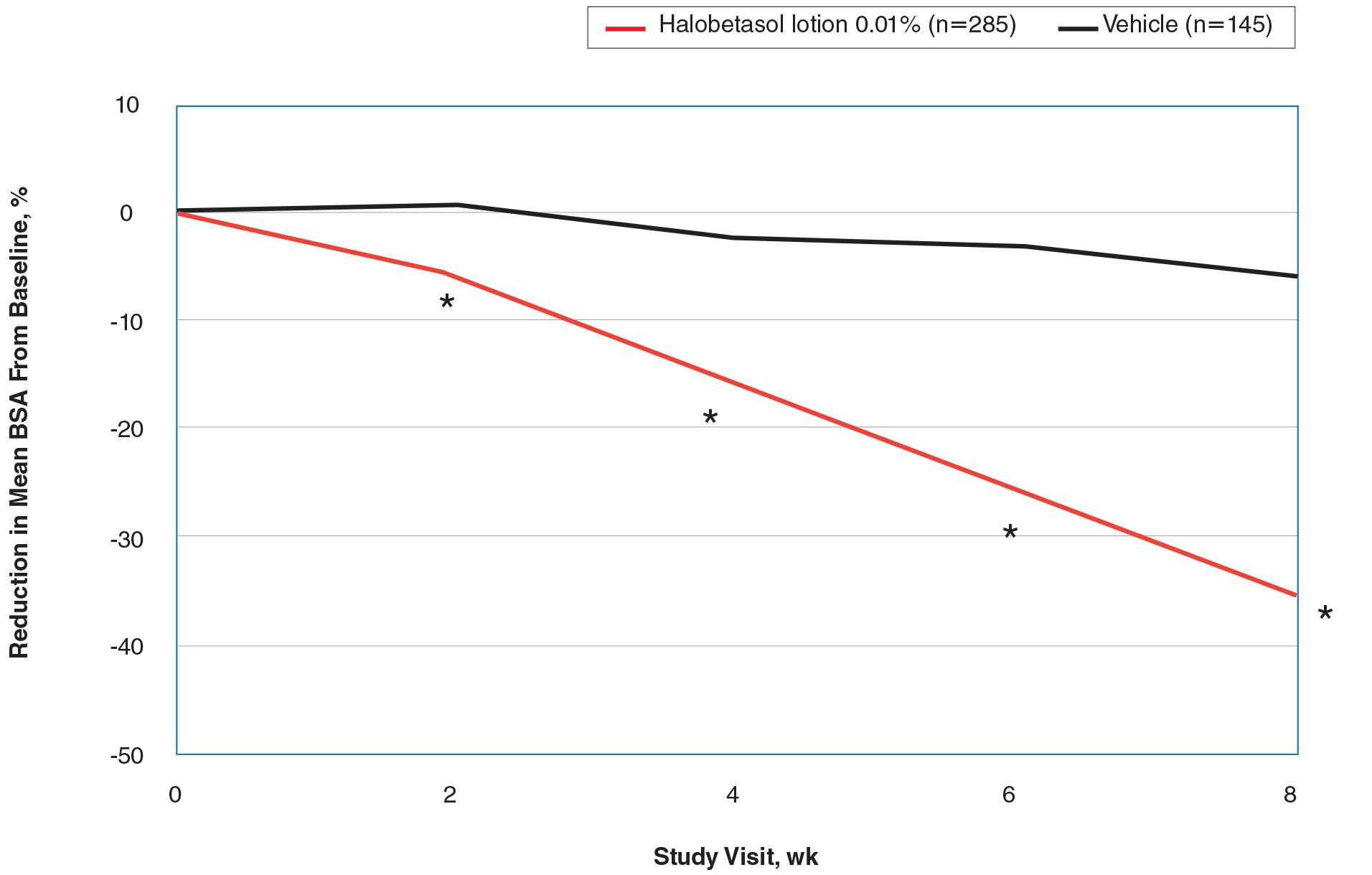

Mean (SD) baseline BSA was 6.2 (3.07), and the mean (SD) size of the target lesion was 36.3 (21.85) cm2. Overall, BSA also was significantly reduced in participants treated with HP/TAZ lotion compared to vehicle. At week 8, the mean percentage change from baseline was —40.7% compared to an increase (+10.1%) in the vehicle group (P=.002)(Figure 3). Improvements in BSA were maintained posttreatment, whereas in the vehicle group, mean (SD) BSA had increased to 6.1 (4.64).

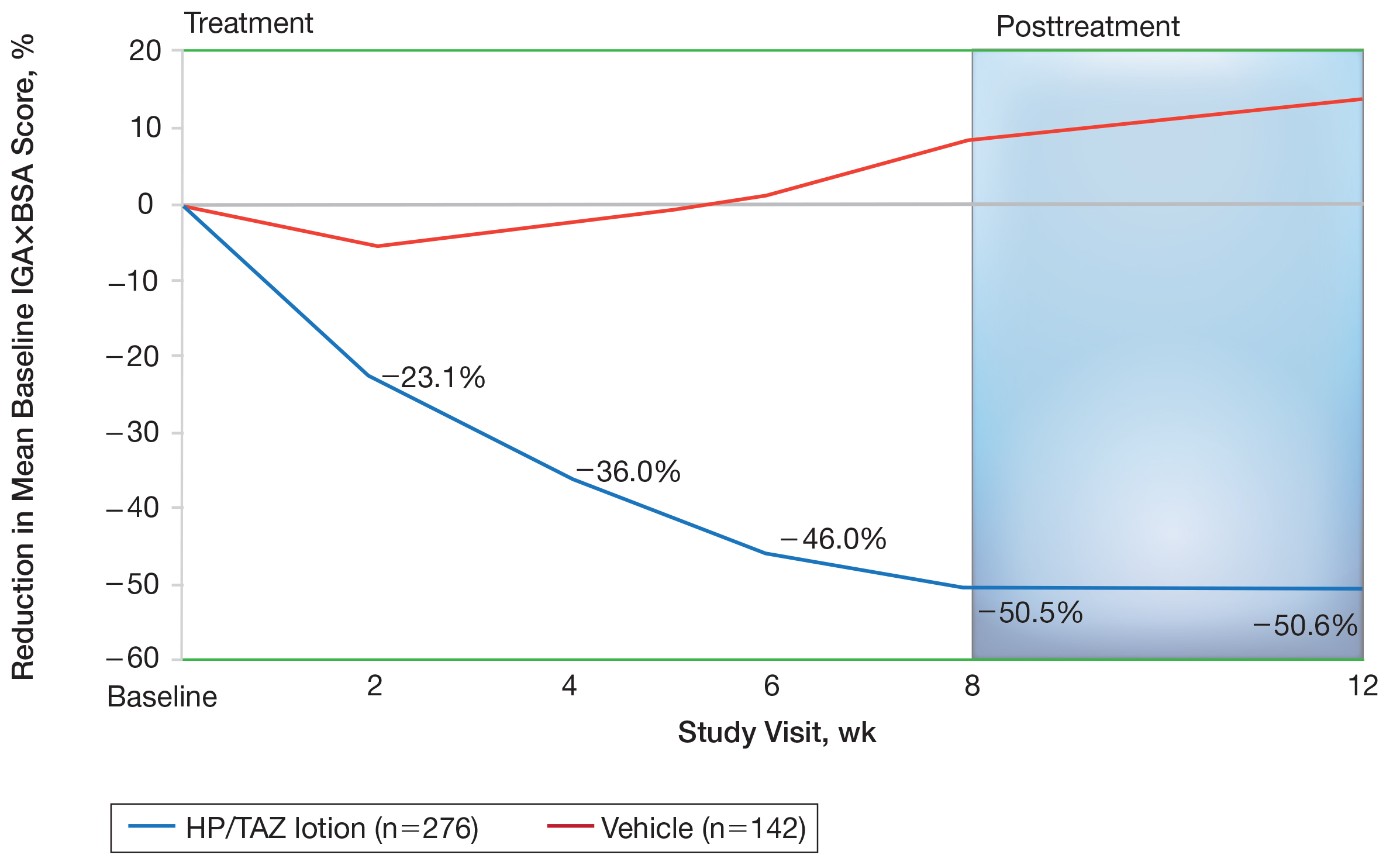

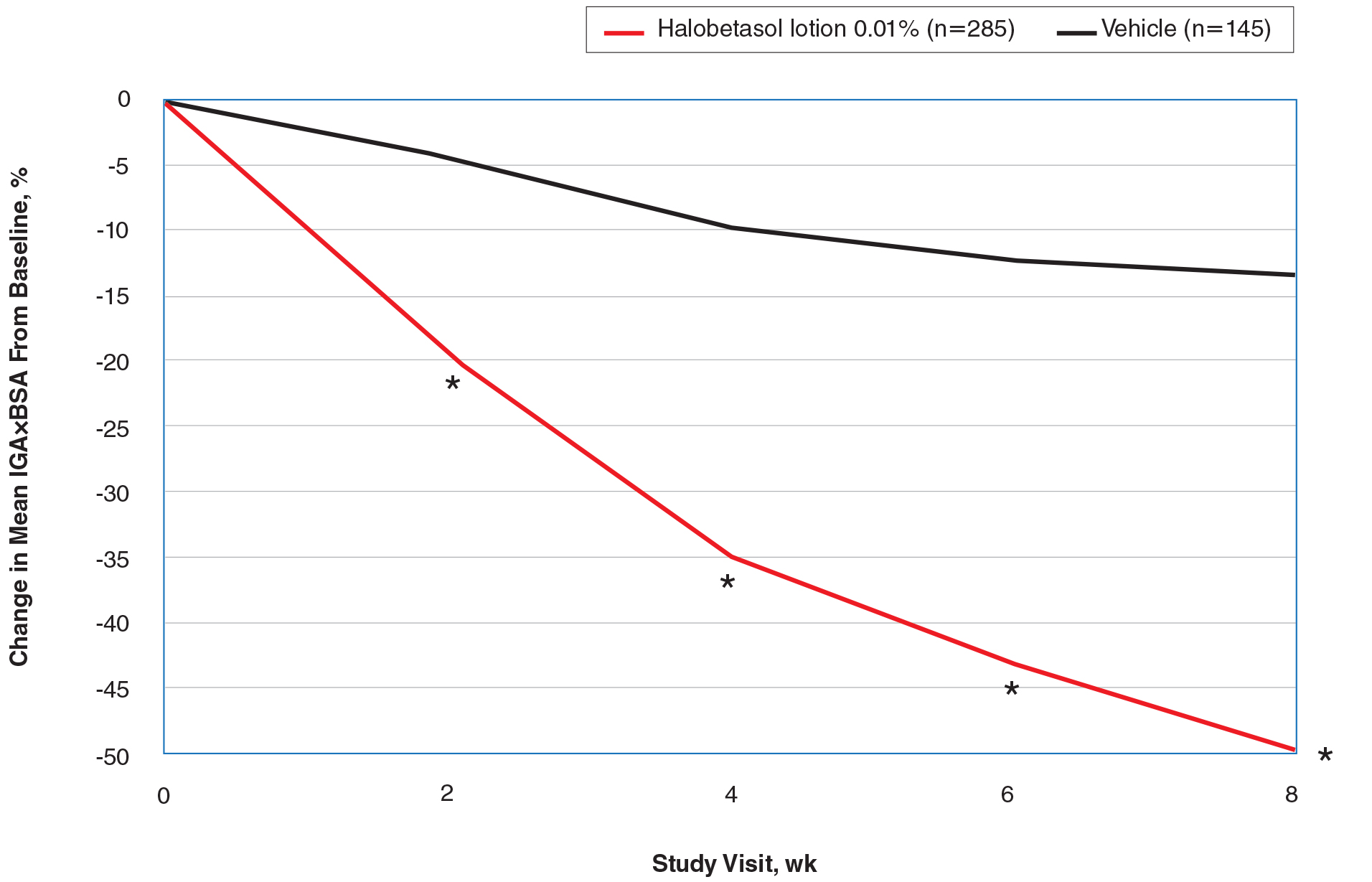

Halobetasol propionate 0.01%–TAZ 0.045% lotion achieved a 50.5% reduction from baseline IGA×BSA by week 8 compared to an 8.5% increase with vehicle (P<.001)(Figure 4). Differences in treatment groups were significant from week 2 (P=.016). Efficacy was maintained posttreatment, with a 50.6% reduction from baseline IGA×BSA at week 12 compared to an increase of 13.6% in the vehicle group (P<.001). Again, although results were similar to the overall study population at week 8 (50.5% vs 51.9%), maintenance of effect was better posttreatment (50.6% vs 46.6%).10

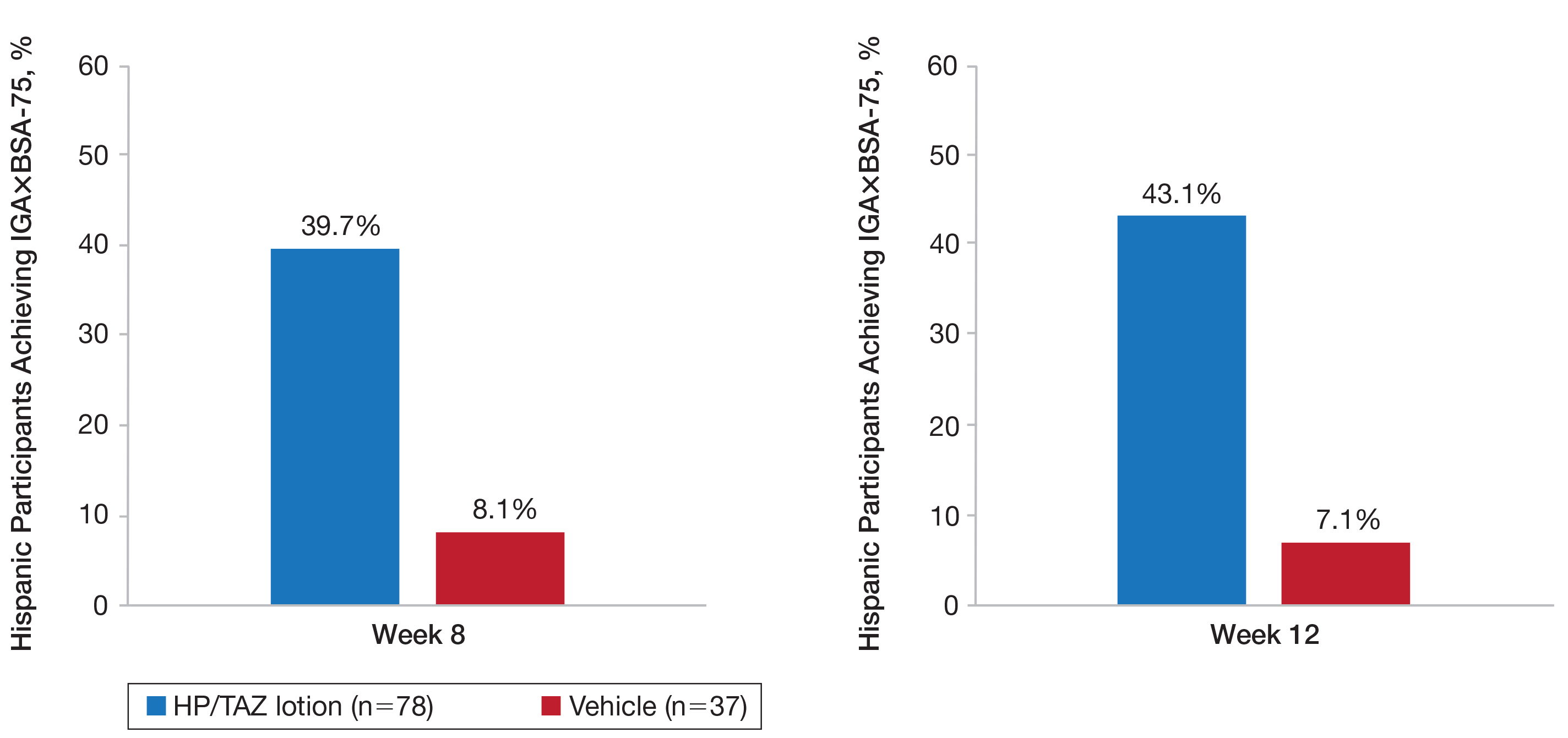

A clinically meaningful effect (IGA×BSA-75) was achieved in 39.7% of Hispanic participants treated with HP/TAZ lotion compared to 8.1% of participants treated with vehicle (P<.001) at week 8. The benefits were significantly different from week 4 and more participants maintained a clinically meaningful effect posttreatment (43.1% vs 7.1%, P<.001)(Figure 5).

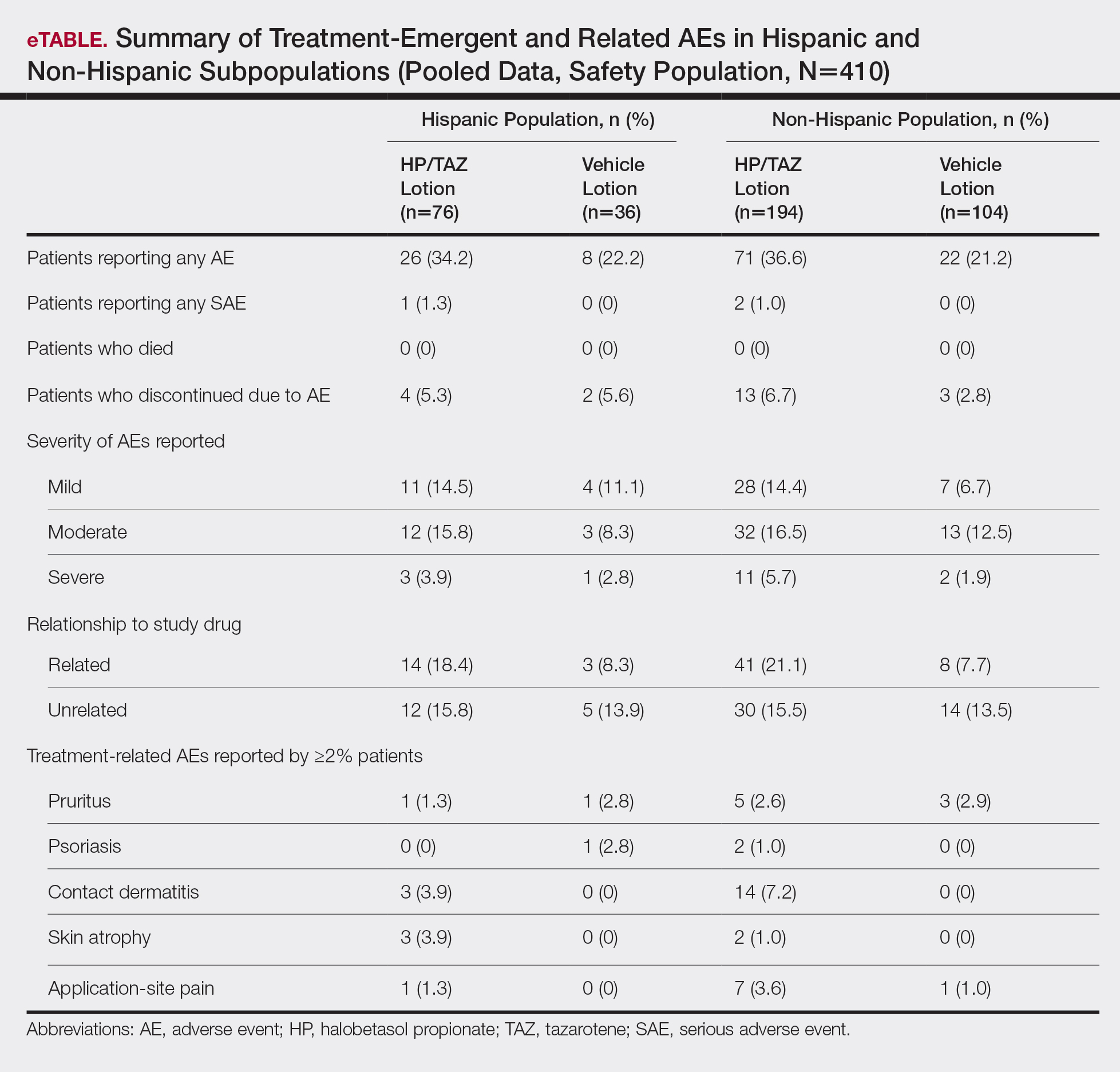

For Hispanic participants overall, 34 participants reported AEs: 26 (34.2%) treated with HP/TAZ lotion and 8 (22.2%) treated with vehicle (eTable). There was 1 (1.3%) serious AE in the HP/TAZ group. Most of the AEs were mild or moderate, with approximately half being related to study treatment. The most common treatment-related AEs in Hispanic participants treated with HP/TAZ lotion were contact dermatitis (n=3, 3.9%) and skin atrophy (n=3, 3.9%) compared to contact dermatitis (n=14, 7.2%) and application-site pain (n=7, 3.6%) in the non-Hispanic population. Pruritus was the most common AE in Hispanic participants treated with vehicle.

Comment

The large number of Hispanic patients in the 2 phase 3 trials8,9 allowed for this valuable subgroup analysis on the topical treatment of Hispanic patients with plaque psoriasis. Validation of observed differences in maintenance of effect and tolerability warrant further study. Prior clinical studies in psoriasis have tended to enroll a small proportion of Hispanic patients without any post hoc analysis. For example, in a pooled analysis of 4 phase 3 trials with secukinumab, Hispanic patients accounted for only 16% of the overall population.11 In our analysis, the Hispanic cohort represented 28% of the overall study population of 2 phase 3 studies investigating the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of HP/TAZ lotion in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis.8,9 In addition, proportionately more Hispanic patients had severe disease (IGA of 4) or severe signs and symptoms of psoriasis (erythema, plaque elevation, and scaling) than the non-Hispanic population. This finding supports other studies that have suggested Hispanic patients with psoriasis tend to have more severe disease but also may reflect thresholds for seeking care.3-5

Halobetasol propionate 0.01%–TAZ 0.045% lotion was significantly more effective than vehicle for all efficacy assessments. In general, efficacy results with HP/TAZ lotion were similar to those reported in the overall phase 3 study populations over the 8-week treatment period. The only noticeable difference was in the posttreatment period. In the overall study population, efficacy was maintained over the 4-week posttreatment period in the HP/TAZ group. In the Hispanic subpopulation, there appeared to be continued improvement in the number of participants achieving treatment success (IGA and erythema), clinically meaningful success, and further reductions in BSA. Although there is a paucity of studies evaluating psoriasis therapies in Hispanic populations, data on etanercept and secukinumab have been published.6,11

Onset of effect also is an important aspect of treatment. In patients with skin of color, including patients of Hispanic ethnicity and higher Fitzpatrick skin phototypes, early clearance of lesions may help limit the severity and duration of postinflammatory pigment alteration. Improvements in IGA×BSA scores were significant compared to vehicle from week 2 (P=.016), and a clinically meaningful improvement with HP/TAZ lotion (IGA×BSA-75) was seen by week 4 (P=.024).

Halobetasol propionate 0.01%–TAZ 0.045% lotion was well tolerated, both in the 2 phase 3 studies and in the post hoc analysis of the Hispanic subpopulation. The incidence of skin atrophy (n=3, 3.9%) was more common vs the non-Hispanic population (n=2, 1.0%). Other common AEs—contact dermatitis, pruritus, and application-site pain—were more common in the non-Hispanic population.

A limitation of our analysis was that it was a post hoc analysis of the Hispanic participants. The phase 3 studies were not designed to specifically study the impact of treatment on ethnicity/race, though the number of Hispanic participants enrolled in the 2 studies was relatively high. The absence of Fitzpatrick skin phototypes in this data set is another limitation of this study.

Conclusion

Halobetasol propionate 0.01%–TAZ 0.045% lotion was associated with significant, rapid, and sustained reductions in disease severity in a Hispanic population with moderate to severe psoriasis that continued to show improvement posttreatment with good tolerability and safety.

Acknowledgments

We thank Brian Bulley, MSc (Konic Limited, United Kingdom), for assistance with the preparation of the manuscript. Ortho Dermatologics funded Konic’s activities pertaining to this manuscript.

- Rachakonda TD, Schupp CW, Armstrong AW. Psoriasis prevalence among adults in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:512-516.

- Davis SA, Narahari S, Feldman SR, et al. Top dermatologic conditions in patients of color: an analysis of nationally representative data. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:466-473.

- Setta-Kaffetzi N, Navarini AA, Patel VM, et al. Rare pathogenic variants in IL36RN underlie a spectrum of psoriasis-associated pustular phenotypes. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:1366-1369.

- Yan D, Afifi L, Jeon C, et al. A cross-sectional study of the distribution of psoriasis subtypes in different ethno-racial groups. Dermatol Online J. 2018;24. pii:13030/qt5z21q4k2.

- Abrouk M, Lee K, Brodsky M, et al. Ethnicity affects the presenting severity of psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:180-182.

- Shah SK, Arthur A, Yang YC, et al. A retrospective study to investigate racial and ethnic variations in the treatment of psoriasis with etanercept. J Drugs Dermatol. 2011;10:866-872.

- Alexis AF, Blackcloud P. Psoriasis in skin of color: epidemiology, genetics, clinical presentation, and treatment nuances. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:16-24.

- Gold LS, Lebwohl MG, Sugarman JL, et al. Safety and efficacy of a fixed combination of halobetasol and tazarotene in the treatment of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: results of 2 phase 3 randomized controlled trials. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:287-293.

- Sugarman JL, Weiss J, Tanghetti EA, et al. Safety and efficacy of a fixed combination halobetasol and tazarotene lotion in the treatment of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: a pooled analysis of two phase 3 studies. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018;17:855-861.

- Blauvelt A, Green LJ, Lebwohl MG, et al. Efficacy of a once-daily fixed combination halobetasol (0.01%) and tazarotene (0.045%) lotion in the treatment of localized moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019;18:297-299.

- Adsit S, Zaldivar ER, Sofen H, et al. Secukinumab is efficacious and safe in Hispanic patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: pooled analysis of four phase 3 trials. Adv Ther. 2017;34:1327-1339.

Psoriasis is a common chronic inflammatory disease affecting a diverse patient population, yet epidemiological and clinical data related to psoriasis in patients with skin of color are sparse. The Hispanic ethnic group includes a broad range of skin types and cultures. Prevalence of psoriasis in a Hispanic population has been reported as lower than in a white population1; however, these data may be influenced by the finding that Hispanic patients are less likely to see a dermatologist when they have skin problems.2 In addition, socioeconomic disparities and cultural variations among racial/ethnic groups may contribute to differences in access to care and thresholds for seeking care,3 leading to a tendency for more severe disease in skin of color and Hispanic ethnic groups.4,5 Greater impairments in health-related quality of life have been reported in patients with skin of color and Hispanic racial/ethnic groups compared to white patients, independent of psoriasis severity.4,6 Postinflammatory pigment alteration at the sites of resolving lesions, a common clinical feature in skin of color, may contribute to the impact of psoriasis on quality of life in patients with skin of color. Psoriasis in darker skin types also can present diagnostic challenges due to overlapping features with other papulosquamous disorders and less conspicuous erythema.7

We present a post hoc analysis of the treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis with a novel fixed-combination halobetasol propionate (HP) 0.01%–tazarotene (TAZ) 0.045% lotion in a Hispanic patient population. Historically, clinical trials for psoriasis have enrolled low proportions of Hispanic patients and other patients with skin of color; in this analysis, the Hispanic population (115/418) represented 28% of the total study population and provided valuable insights.

Methods

Study Design

Two phase 3 randomized controlled trials were conducted to demonstrate the efficacy and safety of HP/TAZ lotion. Patients with a clinical diagnosis of moderate or severe localized psoriasis (N=418) were randomized to receive HP/TAZ lotion or vehicle (2:1 ratio) once daily for 8 weeks with a 4-week posttreatment follow-up.8,9 A post hoc analysis was conducted on data of the self-identified Hispanic population.

Assessments

Efficacy assessments included treatment success (at least a 2-grade improvement from baseline in the investigator global assessment [IGA] and a score of clear or almost clear) and impact on individual signs of psoriasis (at least a 2-grade improvement in erythema, plaque elevation, and scaling) at the target lesion. In addition, reduction in body surface area (BSA) was recorded, and an IGA×BSA score was calculated by multiplying IGA by BSA at each timepoint for each individual patient. A clinically meaningful improvement in disease severity (percentage of patients achieving a 75% reduction in IGA×BSA [IGA×BSA-75]) also was calculated.

Information on reported and observed adverse events (AEs) was obtained at each visit. The safety population included 112 participants (76 in the HP/TAZ group and 36 in the vehicle group).

Statistical Analysis

The statistical and analytical plan is detailed elsewhere9 and relevant to this post hoc analysis. No statistical analysis was carried out to compare data in the Hispanic population with either the overall study population or the non-Hispanic population.

Results

Overall, 115 Hispanic patients (27.5%) were enrolled (eFigure). Patients had a mean (standard deviation [SD]) age of 46.7 (13.12) years, and more than two-thirds were male (n=80, 69.6%).

Overall completion rates (80.0%) for Hispanic patients were similar to those in the overall study population, though there were more discontinuations in the vehicle group. The main reasons for treatment discontinuation among Hispanic patients were participant request (n=8, 7.0%), lost to follow-up (n=8, 7.0%), and AEs (n=4, 3.5%). Hispanic patients in this study had more severe disease—18.3% (n=21) had an IGA score of 4 compared to 13.5% (n=41) of non-Hispanic patients—and more severe erythema (19.1% vs 9.6%), plaque elevation (20.0% vs 10.2%), and scaling (15.7% vs 12.9%) compared to the non-Hispanic populations (Table).

Efficacy of HP/TAZ lotion in Hispanic patients was similar to the overall study populations,9 though maintenance of effect posttreatment appeared to be better. The incidence of treatment-related AEs also was lower.

Halobetasol propionate 0.01%–TAZ 0.045% lotion demonstrated statistically significant superiority based on treatment success compared to vehicle as early as week 4 (P=.034). By week 8, 39.3% of participants treated with HP/TAZ lotion achieved treatment success compared to 9.3% of participants in the vehicle group (P=.002)(Figure 1). Treatment success was maintained over the 4-week posttreatment period, whereby 40.5% of the HP/TAZ-treated participants were treatment successes at week 12 compared to only 4.1% of participants in the vehicle group (P<.001).

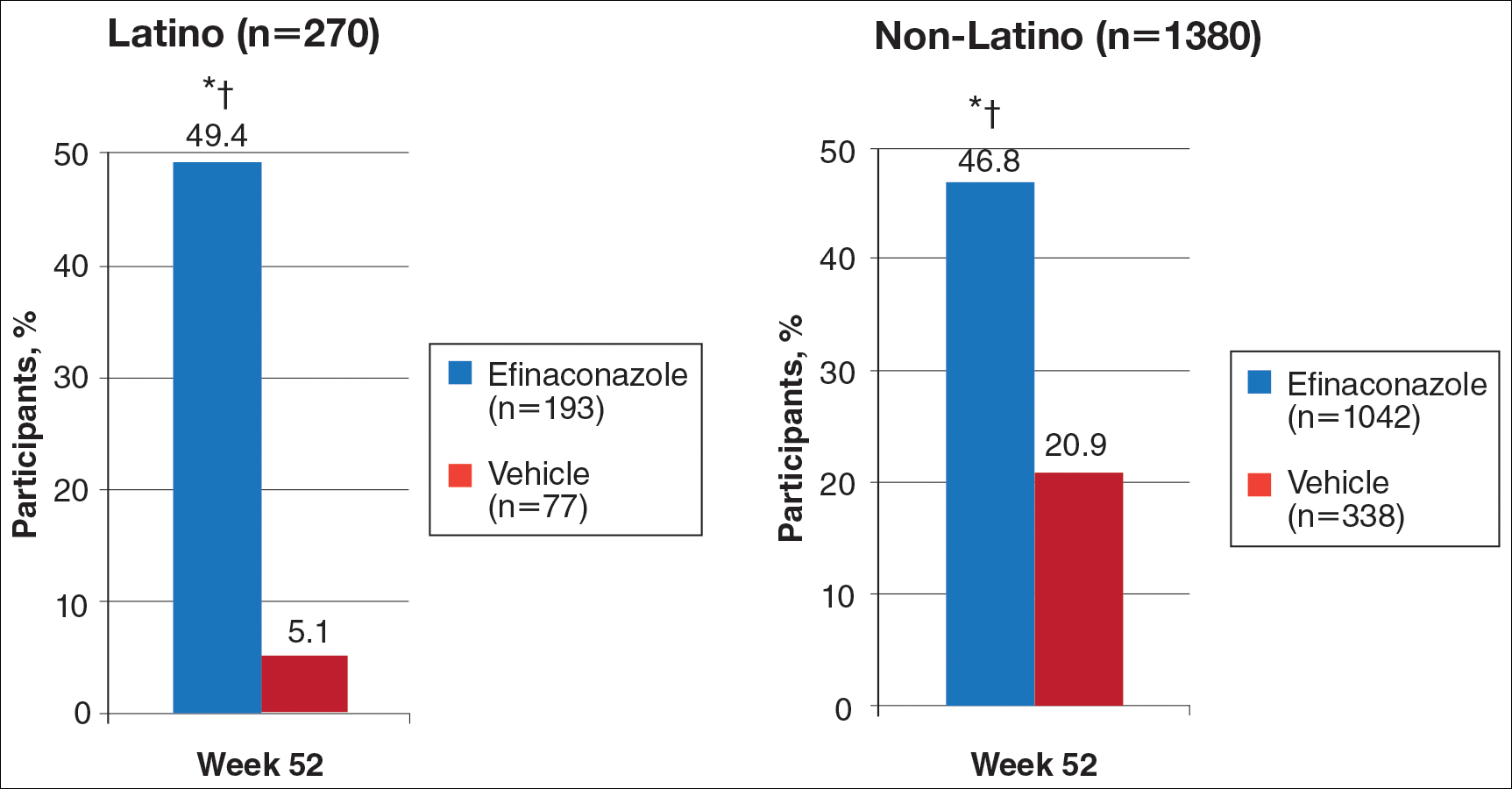

Improvements in psoriasis signs and symptoms at the target lesion were statistically significant compared to vehicle from week 2 (plaque elevation, P=.018) or week 4 (erythema, P=.004; scaling, P<.001)(Figure 2). By week 8, 46.8%, 58.1%, and 63.2% of participants showed at least a 2-grade improvement from baseline and were therefore treatment successes for erythema, plaque elevation, and scaling, respectively (all statistically significant [P<.001] compared to vehicle). The number of participants who achieved at least a 2-grade improvement in erythema with HP/TAZ lotion increased posttreatment from 46.8% to 53.0%.

Mean (SD) baseline BSA was 6.2 (3.07), and the mean (SD) size of the target lesion was 36.3 (21.85) cm2. Overall, BSA also was significantly reduced in participants treated with HP/TAZ lotion compared to vehicle. At week 8, the mean percentage change from baseline was —40.7% compared to an increase (+10.1%) in the vehicle group (P=.002)(Figure 3). Improvements in BSA were maintained posttreatment, whereas in the vehicle group, mean (SD) BSA had increased to 6.1 (4.64).

Halobetasol propionate 0.01%–TAZ 0.045% lotion achieved a 50.5% reduction from baseline IGA×BSA by week 8 compared to an 8.5% increase with vehicle (P<.001)(Figure 4). Differences in treatment groups were significant from week 2 (P=.016). Efficacy was maintained posttreatment, with a 50.6% reduction from baseline IGA×BSA at week 12 compared to an increase of 13.6% in the vehicle group (P<.001). Again, although results were similar to the overall study population at week 8 (50.5% vs 51.9%), maintenance of effect was better posttreatment (50.6% vs 46.6%).10

A clinically meaningful effect (IGA×BSA-75) was achieved in 39.7% of Hispanic participants treated with HP/TAZ lotion compared to 8.1% of participants treated with vehicle (P<.001) at week 8. The benefits were significantly different from week 4 and more participants maintained a clinically meaningful effect posttreatment (43.1% vs 7.1%, P<.001)(Figure 5).

For Hispanic participants overall, 34 participants reported AEs: 26 (34.2%) treated with HP/TAZ lotion and 8 (22.2%) treated with vehicle (eTable). There was 1 (1.3%) serious AE in the HP/TAZ group. Most of the AEs were mild or moderate, with approximately half being related to study treatment. The most common treatment-related AEs in Hispanic participants treated with HP/TAZ lotion were contact dermatitis (n=3, 3.9%) and skin atrophy (n=3, 3.9%) compared to contact dermatitis (n=14, 7.2%) and application-site pain (n=7, 3.6%) in the non-Hispanic population. Pruritus was the most common AE in Hispanic participants treated with vehicle.

Comment

The large number of Hispanic patients in the 2 phase 3 trials8,9 allowed for this valuable subgroup analysis on the topical treatment of Hispanic patients with plaque psoriasis. Validation of observed differences in maintenance of effect and tolerability warrant further study. Prior clinical studies in psoriasis have tended to enroll a small proportion of Hispanic patients without any post hoc analysis. For example, in a pooled analysis of 4 phase 3 trials with secukinumab, Hispanic patients accounted for only 16% of the overall population.11 In our analysis, the Hispanic cohort represented 28% of the overall study population of 2 phase 3 studies investigating the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of HP/TAZ lotion in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis.8,9 In addition, proportionately more Hispanic patients had severe disease (IGA of 4) or severe signs and symptoms of psoriasis (erythema, plaque elevation, and scaling) than the non-Hispanic population. This finding supports other studies that have suggested Hispanic patients with psoriasis tend to have more severe disease but also may reflect thresholds for seeking care.3-5

Halobetasol propionate 0.01%–TAZ 0.045% lotion was significantly more effective than vehicle for all efficacy assessments. In general, efficacy results with HP/TAZ lotion were similar to those reported in the overall phase 3 study populations over the 8-week treatment period. The only noticeable difference was in the posttreatment period. In the overall study population, efficacy was maintained over the 4-week posttreatment period in the HP/TAZ group. In the Hispanic subpopulation, there appeared to be continued improvement in the number of participants achieving treatment success (IGA and erythema), clinically meaningful success, and further reductions in BSA. Although there is a paucity of studies evaluating psoriasis therapies in Hispanic populations, data on etanercept and secukinumab have been published.6,11

Onset of effect also is an important aspect of treatment. In patients with skin of color, including patients of Hispanic ethnicity and higher Fitzpatrick skin phototypes, early clearance of lesions may help limit the severity and duration of postinflammatory pigment alteration. Improvements in IGA×BSA scores were significant compared to vehicle from week 2 (P=.016), and a clinically meaningful improvement with HP/TAZ lotion (IGA×BSA-75) was seen by week 4 (P=.024).

Halobetasol propionate 0.01%–TAZ 0.045% lotion was well tolerated, both in the 2 phase 3 studies and in the post hoc analysis of the Hispanic subpopulation. The incidence of skin atrophy (n=3, 3.9%) was more common vs the non-Hispanic population (n=2, 1.0%). Other common AEs—contact dermatitis, pruritus, and application-site pain—were more common in the non-Hispanic population.

A limitation of our analysis was that it was a post hoc analysis of the Hispanic participants. The phase 3 studies were not designed to specifically study the impact of treatment on ethnicity/race, though the number of Hispanic participants enrolled in the 2 studies was relatively high. The absence of Fitzpatrick skin phototypes in this data set is another limitation of this study.

Conclusion

Halobetasol propionate 0.01%–TAZ 0.045% lotion was associated with significant, rapid, and sustained reductions in disease severity in a Hispanic population with moderate to severe psoriasis that continued to show improvement posttreatment with good tolerability and safety.

Acknowledgments

We thank Brian Bulley, MSc (Konic Limited, United Kingdom), for assistance with the preparation of the manuscript. Ortho Dermatologics funded Konic’s activities pertaining to this manuscript.

Psoriasis is a common chronic inflammatory disease affecting a diverse patient population, yet epidemiological and clinical data related to psoriasis in patients with skin of color are sparse. The Hispanic ethnic group includes a broad range of skin types and cultures. Prevalence of psoriasis in a Hispanic population has been reported as lower than in a white population1; however, these data may be influenced by the finding that Hispanic patients are less likely to see a dermatologist when they have skin problems.2 In addition, socioeconomic disparities and cultural variations among racial/ethnic groups may contribute to differences in access to care and thresholds for seeking care,3 leading to a tendency for more severe disease in skin of color and Hispanic ethnic groups.4,5 Greater impairments in health-related quality of life have been reported in patients with skin of color and Hispanic racial/ethnic groups compared to white patients, independent of psoriasis severity.4,6 Postinflammatory pigment alteration at the sites of resolving lesions, a common clinical feature in skin of color, may contribute to the impact of psoriasis on quality of life in patients with skin of color. Psoriasis in darker skin types also can present diagnostic challenges due to overlapping features with other papulosquamous disorders and less conspicuous erythema.7

We present a post hoc analysis of the treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis with a novel fixed-combination halobetasol propionate (HP) 0.01%–tazarotene (TAZ) 0.045% lotion in a Hispanic patient population. Historically, clinical trials for psoriasis have enrolled low proportions of Hispanic patients and other patients with skin of color; in this analysis, the Hispanic population (115/418) represented 28% of the total study population and provided valuable insights.

Methods

Study Design

Two phase 3 randomized controlled trials were conducted to demonstrate the efficacy and safety of HP/TAZ lotion. Patients with a clinical diagnosis of moderate or severe localized psoriasis (N=418) were randomized to receive HP/TAZ lotion or vehicle (2:1 ratio) once daily for 8 weeks with a 4-week posttreatment follow-up.8,9 A post hoc analysis was conducted on data of the self-identified Hispanic population.

Assessments

Efficacy assessments included treatment success (at least a 2-grade improvement from baseline in the investigator global assessment [IGA] and a score of clear or almost clear) and impact on individual signs of psoriasis (at least a 2-grade improvement in erythema, plaque elevation, and scaling) at the target lesion. In addition, reduction in body surface area (BSA) was recorded, and an IGA×BSA score was calculated by multiplying IGA by BSA at each timepoint for each individual patient. A clinically meaningful improvement in disease severity (percentage of patients achieving a 75% reduction in IGA×BSA [IGA×BSA-75]) also was calculated.

Information on reported and observed adverse events (AEs) was obtained at each visit. The safety population included 112 participants (76 in the HP/TAZ group and 36 in the vehicle group).

Statistical Analysis

The statistical and analytical plan is detailed elsewhere9 and relevant to this post hoc analysis. No statistical analysis was carried out to compare data in the Hispanic population with either the overall study population or the non-Hispanic population.

Results

Overall, 115 Hispanic patients (27.5%) were enrolled (eFigure). Patients had a mean (standard deviation [SD]) age of 46.7 (13.12) years, and more than two-thirds were male (n=80, 69.6%).

Overall completion rates (80.0%) for Hispanic patients were similar to those in the overall study population, though there were more discontinuations in the vehicle group. The main reasons for treatment discontinuation among Hispanic patients were participant request (n=8, 7.0%), lost to follow-up (n=8, 7.0%), and AEs (n=4, 3.5%). Hispanic patients in this study had more severe disease—18.3% (n=21) had an IGA score of 4 compared to 13.5% (n=41) of non-Hispanic patients—and more severe erythema (19.1% vs 9.6%), plaque elevation (20.0% vs 10.2%), and scaling (15.7% vs 12.9%) compared to the non-Hispanic populations (Table).

Efficacy of HP/TAZ lotion in Hispanic patients was similar to the overall study populations,9 though maintenance of effect posttreatment appeared to be better. The incidence of treatment-related AEs also was lower.

Halobetasol propionate 0.01%–TAZ 0.045% lotion demonstrated statistically significant superiority based on treatment success compared to vehicle as early as week 4 (P=.034). By week 8, 39.3% of participants treated with HP/TAZ lotion achieved treatment success compared to 9.3% of participants in the vehicle group (P=.002)(Figure 1). Treatment success was maintained over the 4-week posttreatment period, whereby 40.5% of the HP/TAZ-treated participants were treatment successes at week 12 compared to only 4.1% of participants in the vehicle group (P<.001).

Improvements in psoriasis signs and symptoms at the target lesion were statistically significant compared to vehicle from week 2 (plaque elevation, P=.018) or week 4 (erythema, P=.004; scaling, P<.001)(Figure 2). By week 8, 46.8%, 58.1%, and 63.2% of participants showed at least a 2-grade improvement from baseline and were therefore treatment successes for erythema, plaque elevation, and scaling, respectively (all statistically significant [P<.001] compared to vehicle). The number of participants who achieved at least a 2-grade improvement in erythema with HP/TAZ lotion increased posttreatment from 46.8% to 53.0%.

Mean (SD) baseline BSA was 6.2 (3.07), and the mean (SD) size of the target lesion was 36.3 (21.85) cm2. Overall, BSA also was significantly reduced in participants treated with HP/TAZ lotion compared to vehicle. At week 8, the mean percentage change from baseline was —40.7% compared to an increase (+10.1%) in the vehicle group (P=.002)(Figure 3). Improvements in BSA were maintained posttreatment, whereas in the vehicle group, mean (SD) BSA had increased to 6.1 (4.64).

Halobetasol propionate 0.01%–TAZ 0.045% lotion achieved a 50.5% reduction from baseline IGA×BSA by week 8 compared to an 8.5% increase with vehicle (P<.001)(Figure 4). Differences in treatment groups were significant from week 2 (P=.016). Efficacy was maintained posttreatment, with a 50.6% reduction from baseline IGA×BSA at week 12 compared to an increase of 13.6% in the vehicle group (P<.001). Again, although results were similar to the overall study population at week 8 (50.5% vs 51.9%), maintenance of effect was better posttreatment (50.6% vs 46.6%).10

A clinically meaningful effect (IGA×BSA-75) was achieved in 39.7% of Hispanic participants treated with HP/TAZ lotion compared to 8.1% of participants treated with vehicle (P<.001) at week 8. The benefits were significantly different from week 4 and more participants maintained a clinically meaningful effect posttreatment (43.1% vs 7.1%, P<.001)(Figure 5).

For Hispanic participants overall, 34 participants reported AEs: 26 (34.2%) treated with HP/TAZ lotion and 8 (22.2%) treated with vehicle (eTable). There was 1 (1.3%) serious AE in the HP/TAZ group. Most of the AEs were mild or moderate, with approximately half being related to study treatment. The most common treatment-related AEs in Hispanic participants treated with HP/TAZ lotion were contact dermatitis (n=3, 3.9%) and skin atrophy (n=3, 3.9%) compared to contact dermatitis (n=14, 7.2%) and application-site pain (n=7, 3.6%) in the non-Hispanic population. Pruritus was the most common AE in Hispanic participants treated with vehicle.

Comment

The large number of Hispanic patients in the 2 phase 3 trials8,9 allowed for this valuable subgroup analysis on the topical treatment of Hispanic patients with plaque psoriasis. Validation of observed differences in maintenance of effect and tolerability warrant further study. Prior clinical studies in psoriasis have tended to enroll a small proportion of Hispanic patients without any post hoc analysis. For example, in a pooled analysis of 4 phase 3 trials with secukinumab, Hispanic patients accounted for only 16% of the overall population.11 In our analysis, the Hispanic cohort represented 28% of the overall study population of 2 phase 3 studies investigating the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of HP/TAZ lotion in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis.8,9 In addition, proportionately more Hispanic patients had severe disease (IGA of 4) or severe signs and symptoms of psoriasis (erythema, plaque elevation, and scaling) than the non-Hispanic population. This finding supports other studies that have suggested Hispanic patients with psoriasis tend to have more severe disease but also may reflect thresholds for seeking care.3-5

Halobetasol propionate 0.01%–TAZ 0.045% lotion was significantly more effective than vehicle for all efficacy assessments. In general, efficacy results with HP/TAZ lotion were similar to those reported in the overall phase 3 study populations over the 8-week treatment period. The only noticeable difference was in the posttreatment period. In the overall study population, efficacy was maintained over the 4-week posttreatment period in the HP/TAZ group. In the Hispanic subpopulation, there appeared to be continued improvement in the number of participants achieving treatment success (IGA and erythema), clinically meaningful success, and further reductions in BSA. Although there is a paucity of studies evaluating psoriasis therapies in Hispanic populations, data on etanercept and secukinumab have been published.6,11

Onset of effect also is an important aspect of treatment. In patients with skin of color, including patients of Hispanic ethnicity and higher Fitzpatrick skin phototypes, early clearance of lesions may help limit the severity and duration of postinflammatory pigment alteration. Improvements in IGA×BSA scores were significant compared to vehicle from week 2 (P=.016), and a clinically meaningful improvement with HP/TAZ lotion (IGA×BSA-75) was seen by week 4 (P=.024).

Halobetasol propionate 0.01%–TAZ 0.045% lotion was well tolerated, both in the 2 phase 3 studies and in the post hoc analysis of the Hispanic subpopulation. The incidence of skin atrophy (n=3, 3.9%) was more common vs the non-Hispanic population (n=2, 1.0%). Other common AEs—contact dermatitis, pruritus, and application-site pain—were more common in the non-Hispanic population.

A limitation of our analysis was that it was a post hoc analysis of the Hispanic participants. The phase 3 studies were not designed to specifically study the impact of treatment on ethnicity/race, though the number of Hispanic participants enrolled in the 2 studies was relatively high. The absence of Fitzpatrick skin phototypes in this data set is another limitation of this study.

Conclusion

Halobetasol propionate 0.01%–TAZ 0.045% lotion was associated with significant, rapid, and sustained reductions in disease severity in a Hispanic population with moderate to severe psoriasis that continued to show improvement posttreatment with good tolerability and safety.

Acknowledgments

We thank Brian Bulley, MSc (Konic Limited, United Kingdom), for assistance with the preparation of the manuscript. Ortho Dermatologics funded Konic’s activities pertaining to this manuscript.

- Rachakonda TD, Schupp CW, Armstrong AW. Psoriasis prevalence among adults in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:512-516.

- Davis SA, Narahari S, Feldman SR, et al. Top dermatologic conditions in patients of color: an analysis of nationally representative data. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:466-473.

- Setta-Kaffetzi N, Navarini AA, Patel VM, et al. Rare pathogenic variants in IL36RN underlie a spectrum of psoriasis-associated pustular phenotypes. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:1366-1369.

- Yan D, Afifi L, Jeon C, et al. A cross-sectional study of the distribution of psoriasis subtypes in different ethno-racial groups. Dermatol Online J. 2018;24. pii:13030/qt5z21q4k2.

- Abrouk M, Lee K, Brodsky M, et al. Ethnicity affects the presenting severity of psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:180-182.

- Shah SK, Arthur A, Yang YC, et al. A retrospective study to investigate racial and ethnic variations in the treatment of psoriasis with etanercept. J Drugs Dermatol. 2011;10:866-872.

- Alexis AF, Blackcloud P. Psoriasis in skin of color: epidemiology, genetics, clinical presentation, and treatment nuances. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:16-24.

- Gold LS, Lebwohl MG, Sugarman JL, et al. Safety and efficacy of a fixed combination of halobetasol and tazarotene in the treatment of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: results of 2 phase 3 randomized controlled trials. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:287-293.

- Sugarman JL, Weiss J, Tanghetti EA, et al. Safety and efficacy of a fixed combination halobetasol and tazarotene lotion in the treatment of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: a pooled analysis of two phase 3 studies. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018;17:855-861.

- Blauvelt A, Green LJ, Lebwohl MG, et al. Efficacy of a once-daily fixed combination halobetasol (0.01%) and tazarotene (0.045%) lotion in the treatment of localized moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019;18:297-299.

- Adsit S, Zaldivar ER, Sofen H, et al. Secukinumab is efficacious and safe in Hispanic patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: pooled analysis of four phase 3 trials. Adv Ther. 2017;34:1327-1339.

- Rachakonda TD, Schupp CW, Armstrong AW. Psoriasis prevalence among adults in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:512-516.

- Davis SA, Narahari S, Feldman SR, et al. Top dermatologic conditions in patients of color: an analysis of nationally representative data. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:466-473.

- Setta-Kaffetzi N, Navarini AA, Patel VM, et al. Rare pathogenic variants in IL36RN underlie a spectrum of psoriasis-associated pustular phenotypes. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:1366-1369.

- Yan D, Afifi L, Jeon C, et al. A cross-sectional study of the distribution of psoriasis subtypes in different ethno-racial groups. Dermatol Online J. 2018;24. pii:13030/qt5z21q4k2.

- Abrouk M, Lee K, Brodsky M, et al. Ethnicity affects the presenting severity of psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:180-182.

- Shah SK, Arthur A, Yang YC, et al. A retrospective study to investigate racial and ethnic variations in the treatment of psoriasis with etanercept. J Drugs Dermatol. 2011;10:866-872.

- Alexis AF, Blackcloud P. Psoriasis in skin of color: epidemiology, genetics, clinical presentation, and treatment nuances. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:16-24.

- Gold LS, Lebwohl MG, Sugarman JL, et al. Safety and efficacy of a fixed combination of halobetasol and tazarotene in the treatment of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: results of 2 phase 3 randomized controlled trials. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:287-293.

- Sugarman JL, Weiss J, Tanghetti EA, et al. Safety and efficacy of a fixed combination halobetasol and tazarotene lotion in the treatment of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: a pooled analysis of two phase 3 studies. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018;17:855-861.

- Blauvelt A, Green LJ, Lebwohl MG, et al. Efficacy of a once-daily fixed combination halobetasol (0.01%) and tazarotene (0.045%) lotion in the treatment of localized moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019;18:297-299.

- Adsit S, Zaldivar ER, Sofen H, et al. Secukinumab is efficacious and safe in Hispanic patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: pooled analysis of four phase 3 trials. Adv Ther. 2017;34:1327-1339.

Practice Points

- Although psoriasis is a common inflammatory disease, data in the Hispanic population are sparse and disease may be more severe.

- A recent clinical investigation with halobetasol propionate 0.01%–tazarotene 0.045% lotion included a number of Hispanic patients, affording an ideal opportunity to provide important data on this population.

- This fixed-combination therapy was associated with significant, rapid, and sustained reductions in disease severity in a Hispanic population with moderate to severe psoriasis that continued to show improvement posttreatment with good tolerability and safety.

Safety and Efficacy of Halobetasol Propionate Lotion 0.01% in the Treatment of Moderate to Severe Plaque Psoriasis: A Pooled Analysis of 2 Phase 3 Studies

Psoriasis is a chronic, immune-mediated, inflammatory disease affecting almost 2% of the population.1-3 It is characterized by patches of raised reddish skin covered by silvery-white scales. Most patients have limited disease (<5% body surface area [BSA] involvement) that can be managed with topical agents.4 Topical corticosteroids (TCSs) are considered first-line therapy for mild to moderate disease because of the inflammatory nature of the condition and often are used in conjunction with systemic agents in more severe psoriasis.4

As many as 20% to 30% of patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis have inadequate disease control.5 Several factors may affect patient outcomes; however, drug selection and patient adherence are important given the chronic nature of the disease. A survey of 1200 patients with psoriasis reported nonadherence rates of 73% with topical therapy.6 In addition, patients tend to apply less than the recommended dose or abandon treatment altogether if rapid improvement does not occur7,8; it is not uncommon for patients with psoriasis to mistakenly believe treatment will improve their condition within 1 to 2 weeks.9 Patient satisfaction with topical treatments is low, partly because of these false expectations and formulation issues. Treatments can be greasy and sticky, with unpleasant odors and the potential to stain clothes and linens.7,10 Safety concerns with TCSs also limit their consecutive use beyond 2 to 4 weeks, which is not ideal for a disease that requires a long-term management strategy.

A potent/superpotent TCS that is administered once daily and has a safety profile that affords longer-term, once-daily treatment in an aesthetically pleasing formulation would seem ideal. Herein, we investigate the safety and tolerability of a novel low-concentration (0.01%) lotion formulation of halobetasol propionate (HP), reporting on the pooled data from 2 phase 3 clinical studies in participants with moderate to severe psoriasis.

METHODS

Study Design

We conducted 2 multicenter, double-blind, randomized, parallel-group phase 3 studies to assess the safety, tolerability, and efficacy of HP lotion 0.01% in participants with a clinical diagnosis of moderate to severe psoriasis with an investigator global assessment (IGA) score of 3 or 4 and an affected BSA of 3% to 12%. Participants were randomized (2:1) to receive HP lotion or vehicle applied topically to the affected area once daily for 8 weeks.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The studies included individuals of either sex aged 18 years or older. A target lesion was defined primarily to assess signs of psoriasis, measuring 16 to 100 cm2, with a score of 3 (moderate) or higher for 2 of 3 different psoriasis signs—erythema, plaque elevation, and scaling—and summed score of 8 or higher, with no sign scoring less than 2. Participants who had pustular psoriasis or used phototherapy, photochemotherapy, or systemic psoriasis therapy within the prior 4 weeks or biologics within the prior 3 months, or those who were diagnosed with skin conditions that would interfere with the interpretation of results were excluded from the studies.

Study Oversight

Participants provided written informed consent before study-related procedures were performed, and the protocol and consent were approved by institutional review boards or ethics committees at all investigational sites. The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of Good Clinical Practice and the Declaration of Helsinki.

Efficacy Assessment

A 5-point scale ranging from 0 (clear) to 4 (severe) was used by the investigator at each study visit to assess the overall psoriasis severity of the treatable areas. Treatment success (the percentage of participants with at least a 2-grade improvement in baseline IGA score and a score of 0 [clear] or 1 [almost clear]) was evaluated at weeks 2, 4, 6, and 8, w

Signs of psoriasis at the target lesion were assessed at each visit using individual 5-point scales ranging from 0 (clear) to 4 (severe). Treatment success was defined as at least a 2-grade improvement from baseline score for each of the key signs—erythema, plaque elevation, and scaling—and reported at weeks 2, 4, 6, and 8, with a posttreatment follow-up at week 12.

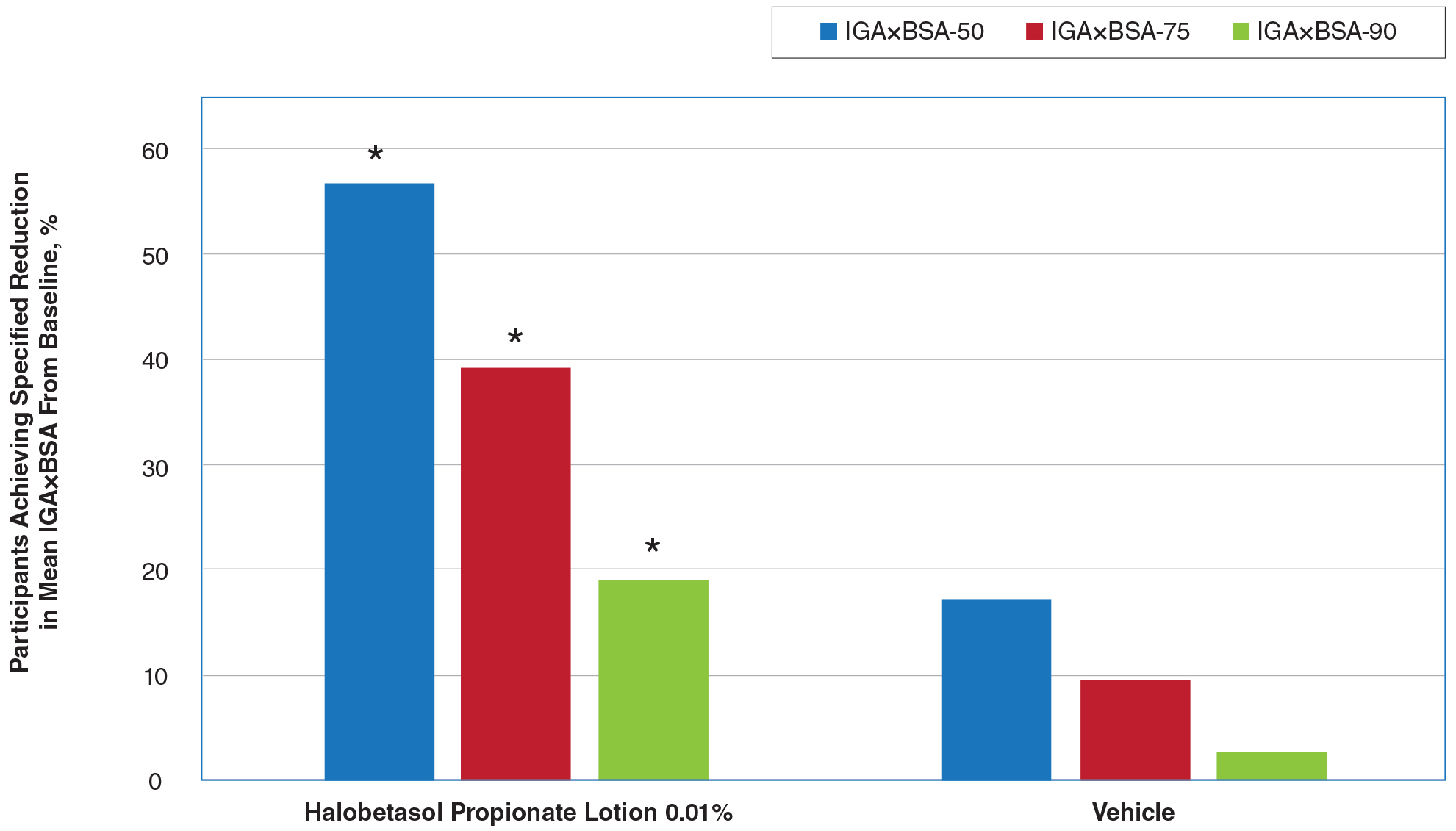

Affected BSA also was evaluated at each visit. In addition, an IGA×BSA composite score was calculated by multiplying the IGA by the BSA (range, 9–48 [eg, maximum IGA=4 and maximum BSA=12]) at each time point. The mean percentage change in IGA×BSA from baseline was calculated for each study visit. Additional end points included the achievement of a 50%, 75%, and 90% or greater reduction from baseline IGA×BSA score—IGA×BSA-50, IGA×BSA-75, and IGA×BSA-90—at week 8.

Safety Assessment

Safety evaluations including adverse events (AEs), local skin reactions (LSRs), vital signs, laboratory evaluations, and physical examinations were performed. Information on reported and observed AEs was obtained at each visit. Routine safety laboratory tests were performed at screening, week 4, and week 8. An abbreviated physical examination was performed at baseline, week 8 (end of treatment), and week 12 (end of study). Treatment areas also were examined by the investigator at baseline and each subsequent visit for the presence or absence of marked known drug-related AEs including skin atrophy, striae, telangiectasia, and folliculitis.

LSR Assessment

Local skin reactions such as itching, dryness, and burning/stinging were evaluated at each study visit using 4-point scales ranging from 0 (clear) to 3 (severe). Given the nature of the disease, the presence of LSRs and symptoms at baseline is commonplace, and as such, these evaluations identified both improvement and any emergent issues.

Statistical Analysis

The primary study goal was to assess differences in treatment efficacy between HP lotion and vehicle with respect to IGA. All statistical processing was performed using SAS unless otherwise stated; statistical tests were 2-sided and performed at the 0.05 level of significance. Markov Chain Monte Carlo multiple imputation was the primary method used to handle missing efficacy data. No imputations were made for missing safety data. All participants were randomized, and the dispensed study drug was included in the intention-to-treat analysis set. This analysis was considered primary for the evaluation of efficacy. Data were analyzed using Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel tests, stratified by analysis center.

Body surface area data were analyzed in a post hoc analysis of covariance with factors of treatment and analysis center and baseline BSA as a covariate. P values for comparisons of percentage change in IGA×BSA were derived from a Wilcoxon rank sum test. For IGA×BSA-50, IGA×BSA-75, and IGA×BSA-90, P values were derived from a Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test. Last observation carried forward was used to impute data for IGA and BSA through week 8 prior to analysis.

The primary safety analysis was conducted at week 8 using the safety analysis set, which included all participants who were randomized, received at least 1 confirmed dose of the study drug, and had at least 1 postbaseline safety assessment. Adverse events were recorded and classified using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA, Version 18.0). A post hoc Wilcoxon rank sum test was conducted to compare itching, dryness, and burning/stinging scores at week 8 for HP lotion versus vehicle.

RESULTS

Participant Disposition

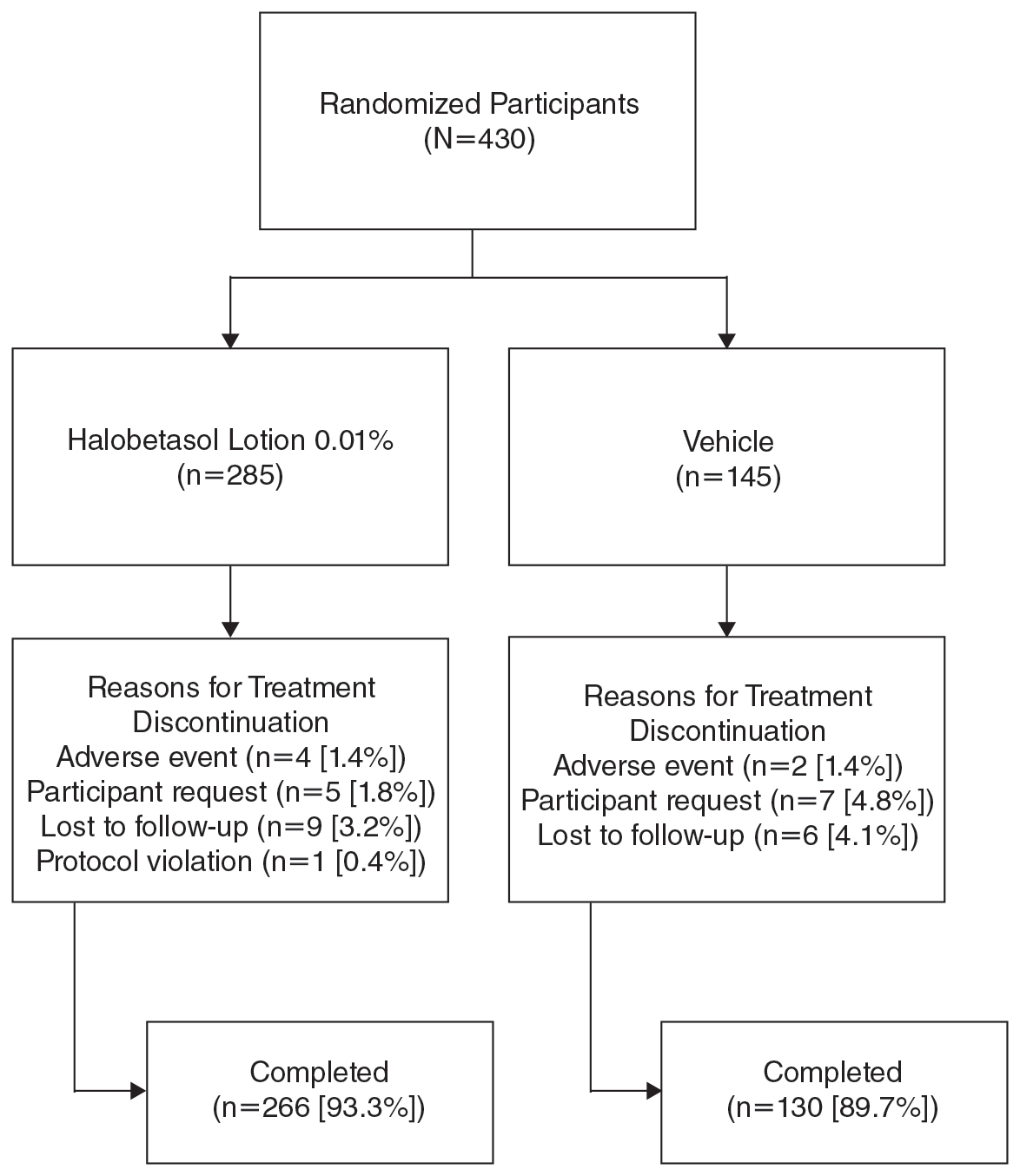

Overall, 430 participants were randomized (2:1) to HP lotion (n=285) or vehicle (n=145)(eFigure 1) and included in the intention-to-treat population. Across the 2 studies, 93.3% (n=266) of participants treated with HP lotion and 89.7% (n=130) of participants treated with vehicle completed treatment. The main reasons for study discontinuation with HP lotion were lost to follow-up (3.2%; n=9), participant request (1.8%; n=5), and AEs (1.4%; n=4). Participant request (4.8%; n=7), lost to follow-up (4.1%; n=6), and AEs (1.4%; n=2) also were the main reasons for treatment discontinuation in the vehicle arm.

A total of 426 participants were included in the safety population, with no postbaseline safety evaluation in 4 participants.

Baseline Participant Demographics

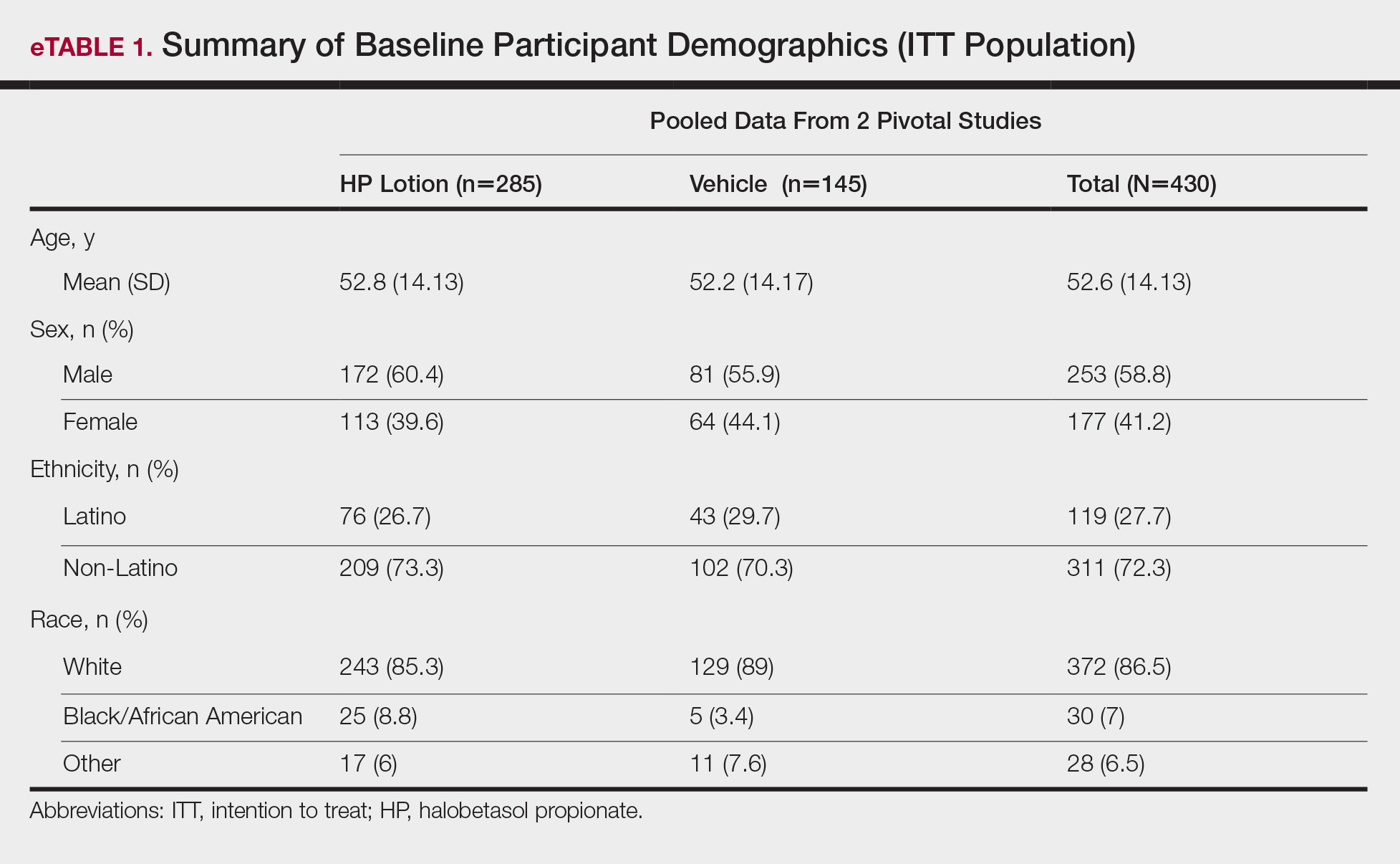

Demographic data were comparable across the 2 studies. The mean age (SD) was 52.6 (14.13) years. Overall, the majority of participants were male (58.8%; n=253) and white (86.5%; n=372)(eTable 1).

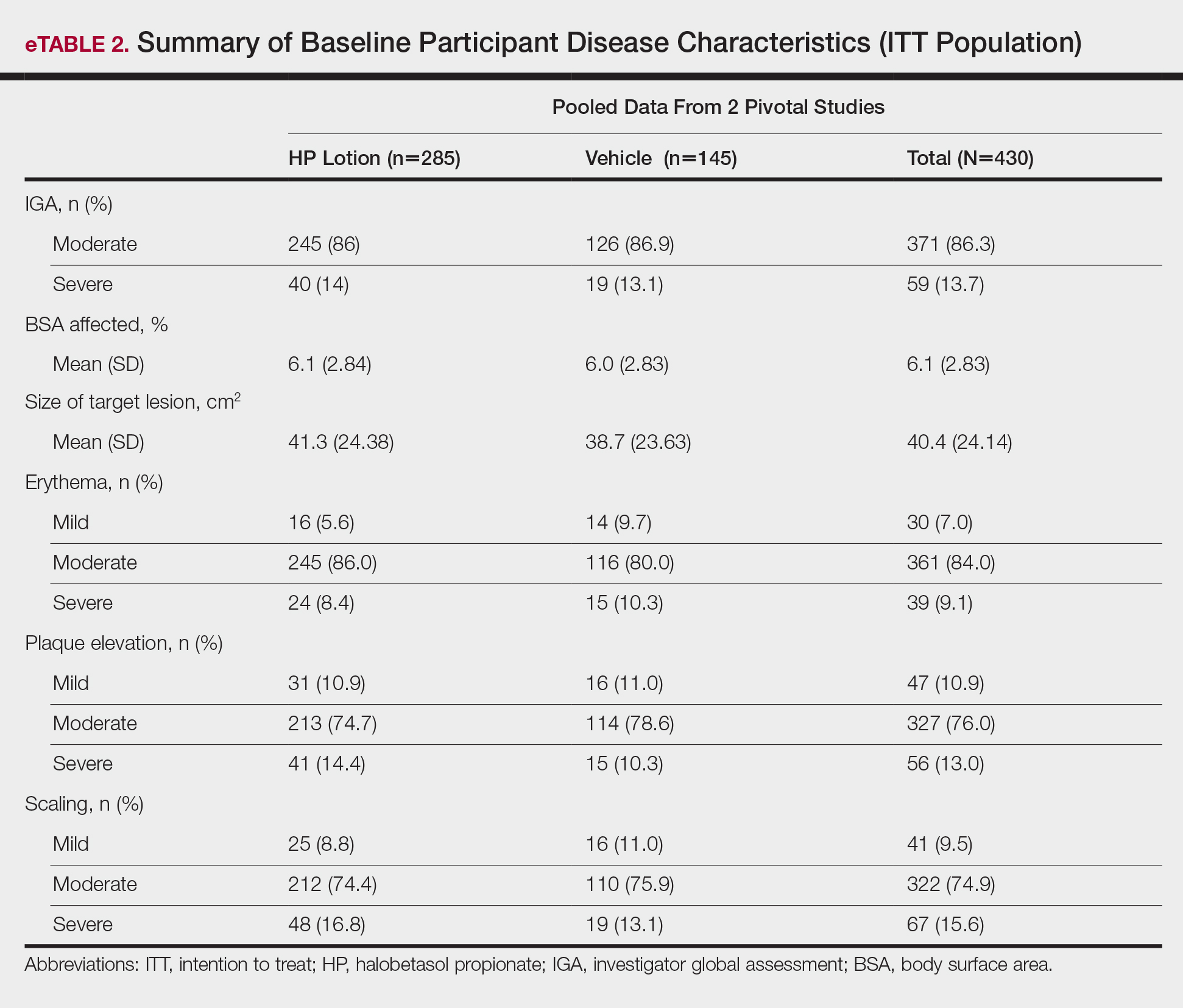

Baseline disease characteristics also were comparable across the treatment groups. Participants had moderate (86.3%; n=371) or severe (13.7%; n=59) disease, with a mean BSA (SD) of 6.1% (2.83) and mean size of target lesion (SD) of 40.4 cm2 (24.14). The majority of participants had moderate (erythema, 84.0%; plaque elevation, 76.0%; and scaling, 74.9%) or severe (erythema, 9.1%; plaque elevation, 13.0%; and scaling, 15.6%) signs of psoriasis at the target lesion site (eTable 2).

Efficacy Evaluation

IGA of Disease Severity

Halobetasol propionate lotion was consistently more effective than its vehicle in achieving treatment success (at least a 2-grade improvement in baseline IGA score and a score of 0 [clear] or 1 [almost clear]). Halobetasol propionate lotion demonstrated statistically significant superiority over vehicle as early as week 2 (P=.003). By week 8, 37.43% of participants in the HP lotion group achieved treatment success compared with 10.03% in the vehicle group (P<.001)(Figure 1).

Overall, 39% of participants who had moderate disease (IGA score, 3) at baseline were treatment successes with HP lotion at week 8 compared with 11.53% of participants treated with vehicle; 27.97% of participants with severe disease (IGA score, 4) were treatment successes, with at least a 3-grade improvement in IGA. No participants with severe psoriasis who were treated with vehicle achieved treatment success at week 8. Efficacy was similar in female and male participants, allowing for vehicle effects.

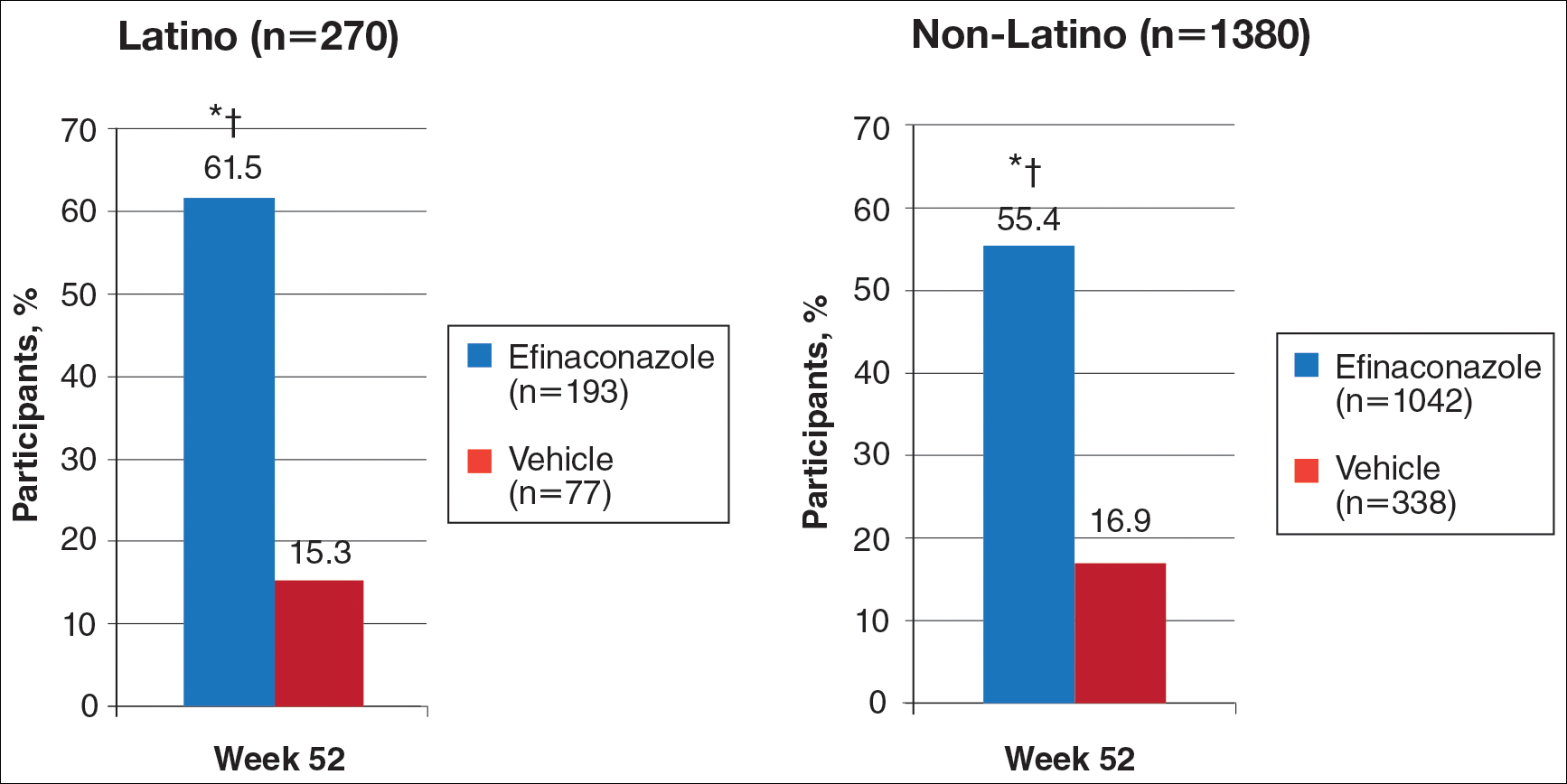

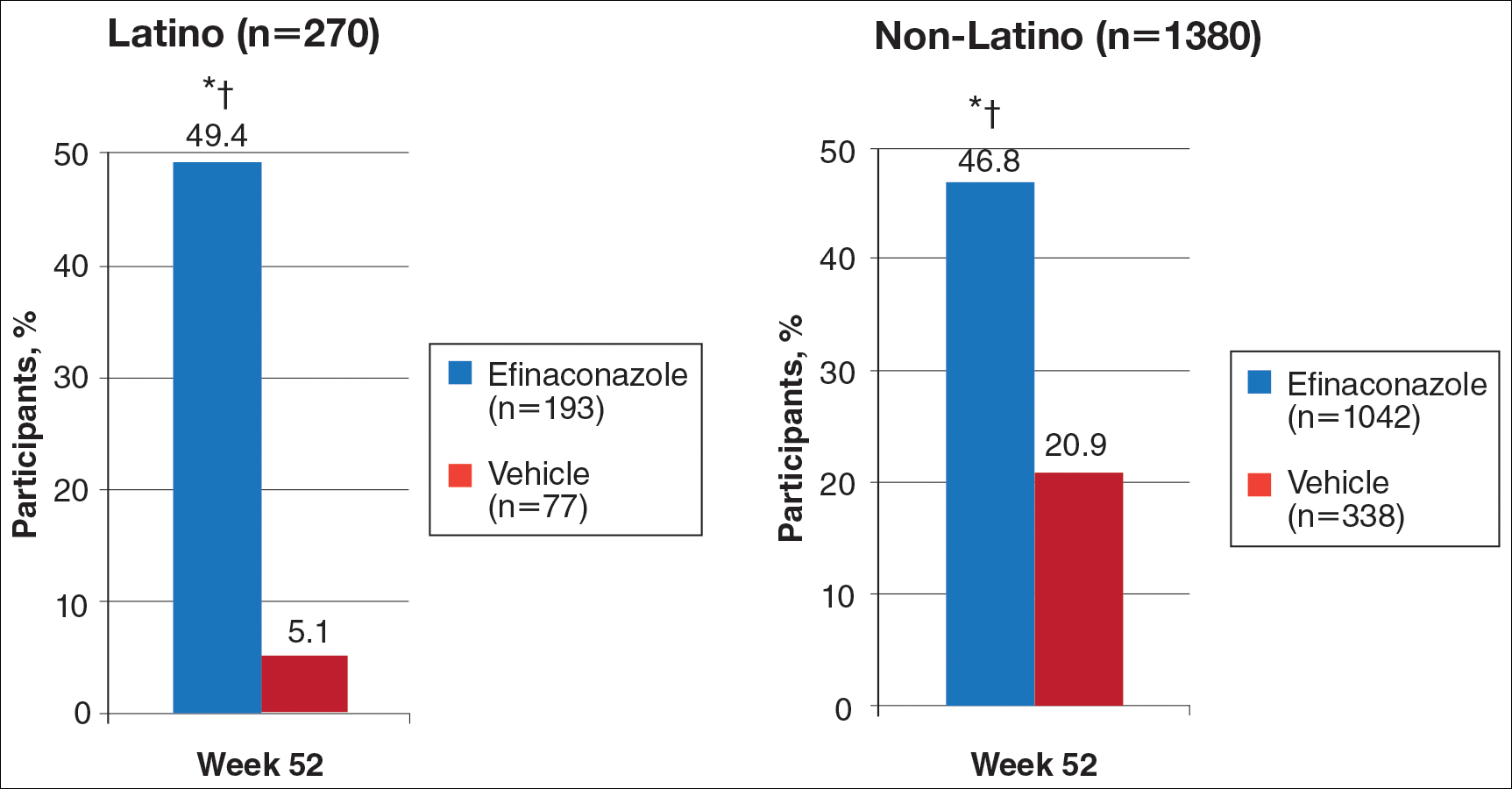

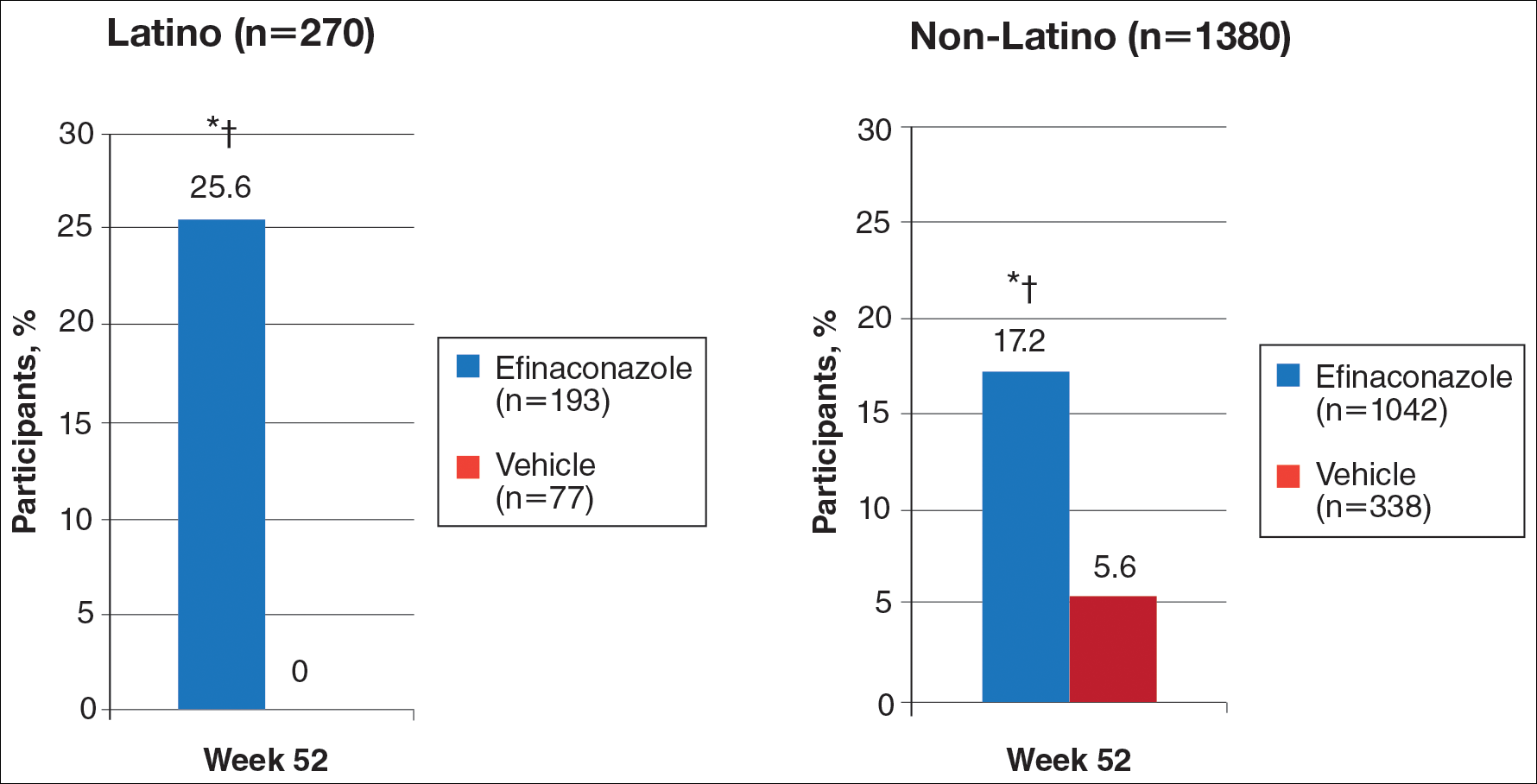

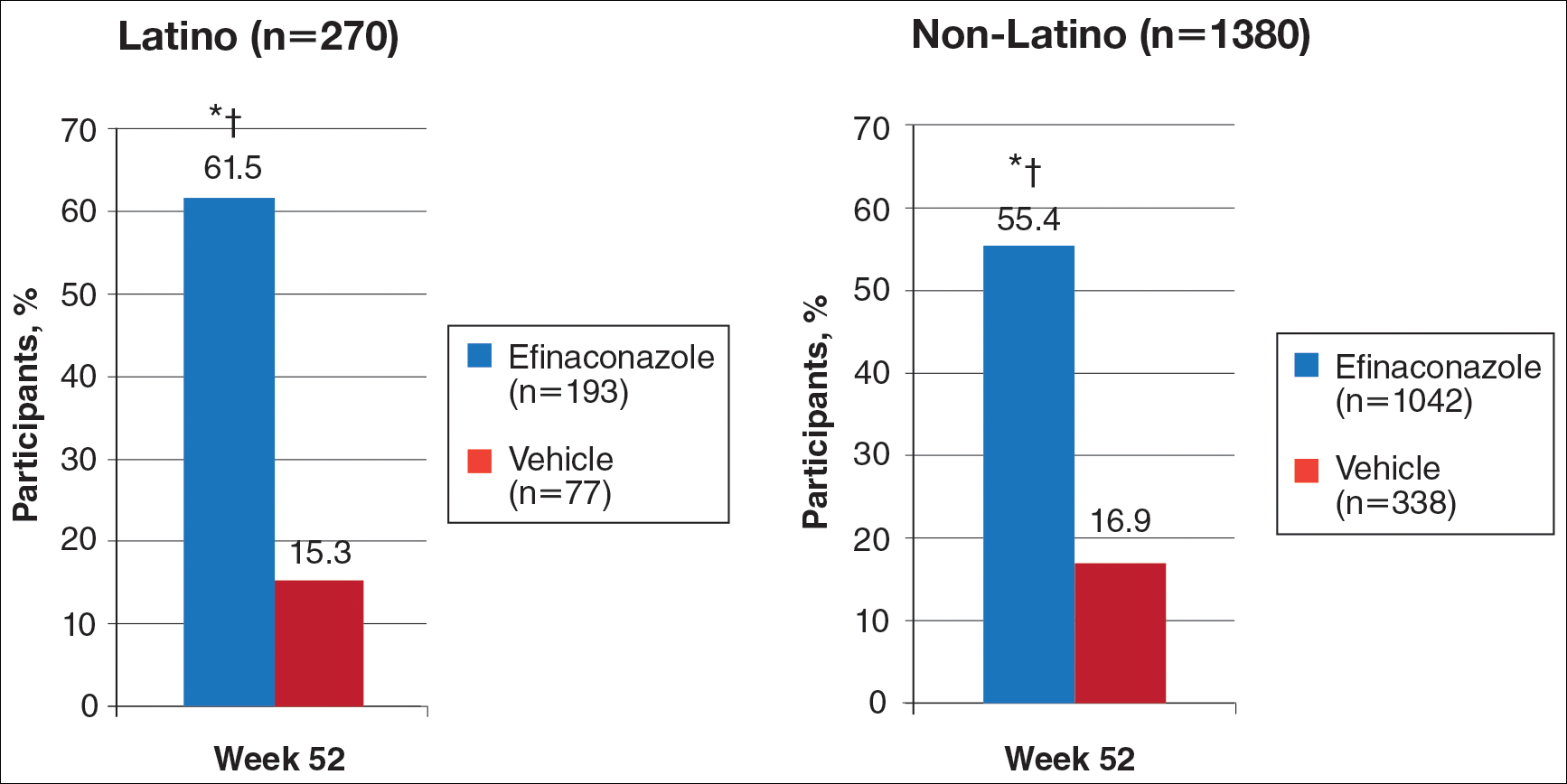

Severity of Signs of Psoriasis (Erythema, Plaque Elevation, and Scaling) at Target Lesion Site

Halobetasol propionate lotion was statistically superior to vehicle in reducing the psoriasis signs of erythema, plaque elevation, and scaling at the target lesion from week 2. At week 8, treatment success (at least a 2-grade improvement from baseline) was achieved by 51.48% (erythema), 57.64% (plaque elevation), and 58.98% (scaling) of participants compared with 17.85%, 23.61%, and 22.82%, respectively, with vehicle (all P<.001)(Figure 2).

BSA Assessment

Halobetasol propionate lotion was statistically superior to vehicle in reducing BSA from week 2. At week 8 there was a 35.20% reduction in mean BSA for HP lotion compared to 5.85% for vehicle (P<.001)(eFigure 2).

IGA×BSA Composite Score

At baseline, the mean IGA×BSA scores for HP lotion and vehicle were similar: 19.3 and 18.8, respectively. By week 8, the percentage change in mean IGA×BSA score with HP lotion was 49.44% compared to 13.35% with vehicle (P<.001). Differences were significant from week 2 (P<.001)(Figure 3).

By week 8, 56.8% of participants (n=162) treated with HP lotion had achieved a 50% or greater reduction in baseline IGA×BSA compared to 17.2% of participants treated with vehicle (P<.001). Reductions of IGA×BSA-75 and IGA×BSA-90 were achieved in 39.3% and 19.3% of participants treated with HP lotion, respectively, compared with 9.7% and 2.8% of participants treated with vehicle (both P<.001)(eFigure 3).

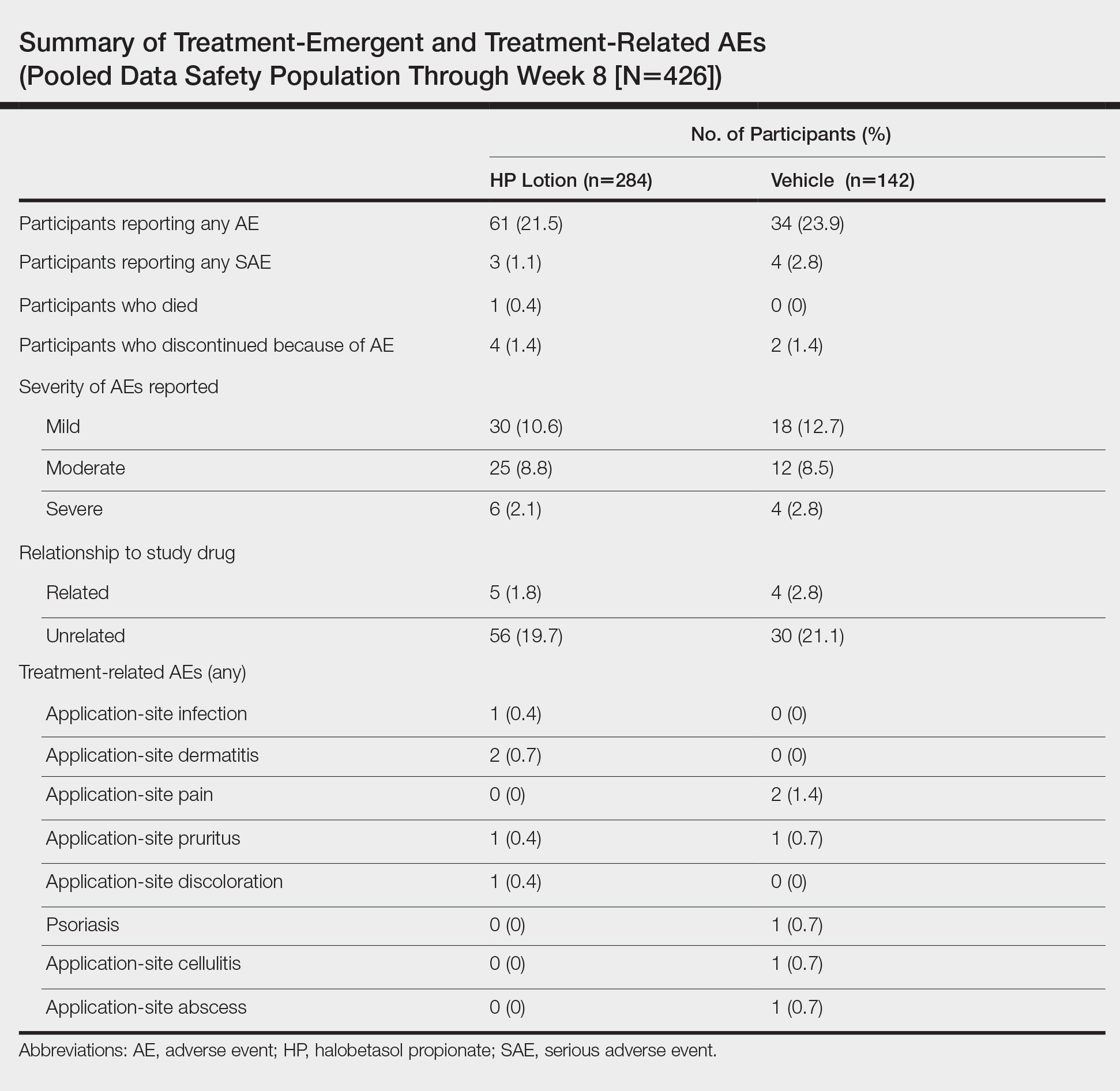

Safety Evaluation

Adverse event reports were low and similar between the active and vehicle groups. Overall, 61 participants (21.5%) treated with HP lotion reported AEs compared with 34 participants (23.9%) treated with vehicle (Table). The majority of participants treated with HP lotion (90.2%) had AEs that were mild or moderate. There was 1 AE of telangiectasia, not considered treatment related. There were 5 treatment-related AEs for HP lotion, all at the application site: dermatitis (0.7%; n=2), infection (0.4%; n=1), pruritus (0.4%; n=1), and discoloration (0.4%; n=1). There were no AE reports of skin atrophy or folliculitis.

Local Skin Reactions

Most LSRs at baseline were mild to moderate in severity. Itching was the most common, present in 76.8% of participants. Participant-reported burning/stinging was less common, reported by 40.6% of participants. Investigator-reported dryness was noted in 65.7% of participants. There was a rapid improvement in participant-reported itching as early as week 2 that was sustained to the end of the studies, with more gradual improvements in skin dryness and burning/stinging.

COMMENT

Plaque psoriasis is a chronic condition. The rationale behind the development of HP lotion 0.01% was to provide optimal topical treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis, allowing for the potential of prolonged use beyond the 2-week consecutive use normally applied to HP cream 0.05% in a light, once-daily, aesthetically pleasing lotion formulation that patients would prefer.

Treatment success was rapid and achieved in more than 37% of participants by week 8, with significant improvements in psoriasis signs and symptoms (erythema, plaque elevation, and scaling) compared with vehicle. However, IGA does not consider BSA involvement, a key aspect of disease severity,11,12 and improvements in psoriasis signs of erythema, plaque elevation, and scaling were only assessed at the target lesion. Recently, the product of the IGA and BSA involvement (IGA×BSA) has been proposed as a simple alternative for assessing response to therapy that has been consistently shown to be highly correlated with the psoriasis area and severity index.13-19 Halobetasol propionate lotion 0.01% achieved a 50% reduction in IGA×BSA score by week 8. This efficacy compares well with results reported with apremilast in patients with moderate plaque psoriasis.20

Achieving clinically meaningful outcomes is an important aspect of disease management, especially in psoriasis with its disease burden and detriment to quality of life. It has been suggested that achieving a 75% or greater reduction from baseline IGA×BSA score (IGA×BSA-75) is an appropriate clinical goal.20 In our investigation, IGA×BSA-75 was achieved by 39% of participants treated with HP lotion by week 8, which again compares favorably with 35% of participants in the apremilast study who achieved IGA×BSA-75 at week 16.20

Physicians continue to have long-term safety concerns with TCSs,4,11,12 participants remain concerned about the risk for skin thinning,13 and product labelling restricts HP cream 0.05% consecutive use to 2 weeks. In clinical experience, HP cream 0.05% is well tolerated, with potential local AEs similar to those experienced with other superpotent TCSs. In short-term clinical trials, local AEs at the site of application were reported in up to 13% of patients21-26; itching, burning, or stinging were the most common local AEs (reported in 4.4% of patients).27

There were minimal safety concerns in our 2 studies using an 8-week, once-daily treatment regimen with HP lotion 0.01%. Local AEs at the application site were reported in less than 1% of participants. Baseline itching, dryness, and burning/stinging all improved with treatment.

CONCLUSION

Halobetasol propionate lotion 0.01% provides rapid improvement in disease severity. Halobetasol propionate lotion was consistently more effective than vehicle in achieving treatment success; reducing the BSA affected by the disease; reducing erythema, plaque elevation, and scaling at the target lesion; and improving IGA×BSA score over 8 weeks, which is a realistic time frame to see improvement in psoriasis with a topical steroid. There were minimal safety concerns with prolonged use. Halobetasol propionate lotion may provide an effective and reasonable treatment option in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis.

Acknowledgment

We thank Brian Bulley, MSc (Konic Limited, United Kingdom), for assistance with the preparation of this article. Ortho Dermatologics funded Mr. Bulley’s activities pertaining to this article.

- Gudjonsson JE, Elder JT. Psoriasis: epidemiology. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:535-546.

- Liu Y, Krueger JG, Bowcock AM. Psoriasis: genetic associations and immune system changes. Genes Immun. 2007;8:1-12.

- Nestle FO, Kaplan DH, Barker J. Psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:496-509.

- Menter A, Korman NJ, Elmets CA, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. section 3. guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with topical therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:643-659.

- Alinia H, Moradi Tuchayi S, Smith JA, et al. Long-term adherence to topical psoriasis treatment can be abysmal: a 1-year randomized intervention study using objective electronic adherence monitoring. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176:759-764.

- Young M, Aldredge L, Parker P. Psoriasis for the primary care practitioner. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2017;29:157-178.

- Devaux S, Castela A, Archier E, et al. Adherence to topical treatment in psoriasis: a systematic literature review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26(suppl 3):61-67.

- Ersser SJ, Cowdell FC, Latter SM, et al. Self-management experiences in adults with mild-moderate psoriasis: an exploratory study and implications for improved support. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:1044-1049.

- Choi CW, Kim BR, Ohn J, et al. The advantage of cyclosporine A and methotrexate rotational therapy in long-term systemic treatment for chronic plaque psoriasis in a real world practice. Ann Dermatol. 2017;29:55-60.

- Callis Duffin K, Yeung H, Takeshita J, et al. Patient satisfaction with treatments for moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis in clinical practice. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:672-680.

- Spuls PI, Lecluse LL, Poulsen ML, et al. How good are clinical severity and outcome measures for psoriasis? quantitative evaluation in a systematic review. J Invest Dermatol. 2010;130:933-943.

- Menter A, Gottlieb A, Feldman SR, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: section 1. overview of psoriasis and guidelines of care for the treatment of psoriasis with biologics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:826-850.

- Bozek A, Reich A. The reliability of three psoriasis assessment tools: psoriasis area severity index, body surface area and physician global assessment. Adv Clin Exp Med. 2017;26:851-856.

- Walsh JA, McFadden M, Woodcock J, et al. Product of the Physician Global Assessment and body surface area: a simple static measure of psoriasis severity in a longitudinal cohort. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:931-937.

- Paul C, Cather J, Gooderham M, et al. Efficacy and safety of apremilast, an oral phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor, in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis over 52 weeks: a phase III, randomized, controlled trial (ESTEEM 2). Br J Dermatol. 2015;173:1387-1399.

- Duffin KC, Papp KA, Bagel J, et al. Evaluation of the Physician Global Assessment and body surface area composite tool for assessing psoriasis response to apremilast therapy: results from ESTEEM 1 and ESTEEM 2. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16:147-153.

- Chiesa Fuxench ZC, Callis DK, Siegel M, et al. Validity of the Simple Measure for Assessing Psoriasis Activity (S-MAPA) for objectively evaluating disease severity in patients with plaque psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:868-870.

- Walsh J. Comparative assessment of PASI and variations of PGA×BSA as measures of psoriasis severity in a clinical trial of moderate to severe psoriasis [poster 1830]. Presented at: Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology; March 20-24, 2015; San Francisco, CA.

- Gottlieb AB, Merola JF, Chen R, et al. Assessing clinical response and defining minimal disease activity in plaque psoriasis with the Physician Global Assessment and body surface area (PGA×BSA) composite tool: An analysis of apremilast phase 3 ESTEEM data. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:1178-1180.

- Strober B, Bagel J, Lebwohl M, et al. Efficacy and safety of apremilast in patients with moderate plaque psoriasis with lower BSA: week 16 results from the UNVEIL study. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16:801-808.

- Bernhard J, Whitmore C, Guzzo C, et al. Evaluation of halobetasol propionate ointment in the treatment of plaque psoriasis: report on two double-blind, vehicle-controlled studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:1170-1174.

- Katz HI, Gross E, Buxman M, et al. A double-blind, vehicle-controlled paired comparison of halobetasol propionate cream on patients with plaque psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:1175-1178.

- Blum G, Yawalkar S. A comparative, multicenter, double blind trial of 0.05% halobetasol propionate ointment and 0.1% betamethasone valerate ointment in the treatment of patients with chronic, localized plaque psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:1153-1156.

- Goldberg B, Hartdegen R, Presbury D, et al. A double-blind, multicenter comparison of 0.05% halobetasol propionate ointment and 0.05% clobetasol propionate ointment in patients with chronic, localized plaque psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:1145-1148.

- Mensing H, Korsukewitz G, Yawalkar S. A double-blind, multicenter comparison between 0.05% halobetasol propionate ointment and 0.05% betamethasone dipropionate ointment in chronic plaque psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:1149-1152.

- Herz G, Blum G, Yawalkar S. Halobetasol propionate cream by day and halobetasol propionate ointment at night for the treatment of pediatric patients with chronic, localized psoriasis and atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:1166-1169.

- Ultravate [package insert]. Jacksonville, FL: Ranbaxy; 2012.

Psoriasis is a chronic, immune-mediated, inflammatory disease affecting almost 2% of the population.1-3 It is characterized by patches of raised reddish skin covered by silvery-white scales. Most patients have limited disease (<5% body surface area [BSA] involvement) that can be managed with topical agents.4 Topical corticosteroids (TCSs) are considered first-line therapy for mild to moderate disease because of the inflammatory nature of the condition and often are used in conjunction with systemic agents in more severe psoriasis.4

As many as 20% to 30% of patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis have inadequate disease control.5 Several factors may affect patient outcomes; however, drug selection and patient adherence are important given the chronic nature of the disease. A survey of 1200 patients with psoriasis reported nonadherence rates of 73% with topical therapy.6 In addition, patients tend to apply less than the recommended dose or abandon treatment altogether if rapid improvement does not occur7,8; it is not uncommon for patients with psoriasis to mistakenly believe treatment will improve their condition within 1 to 2 weeks.9 Patient satisfaction with topical treatments is low, partly because of these false expectations and formulation issues. Treatments can be greasy and sticky, with unpleasant odors and the potential to stain clothes and linens.7,10 Safety concerns with TCSs also limit their consecutive use beyond 2 to 4 weeks, which is not ideal for a disease that requires a long-term management strategy.

A potent/superpotent TCS that is administered once daily and has a safety profile that affords longer-term, once-daily treatment in an aesthetically pleasing formulation would seem ideal. Herein, we investigate the safety and tolerability of a novel low-concentration (0.01%) lotion formulation of halobetasol propionate (HP), reporting on the pooled data from 2 phase 3 clinical studies in participants with moderate to severe psoriasis.

METHODS

Study Design

We conducted 2 multicenter, double-blind, randomized, parallel-group phase 3 studies to assess the safety, tolerability, and efficacy of HP lotion 0.01% in participants with a clinical diagnosis of moderate to severe psoriasis with an investigator global assessment (IGA) score of 3 or 4 and an affected BSA of 3% to 12%. Participants were randomized (2:1) to receive HP lotion or vehicle applied topically to the affected area once daily for 8 weeks.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The studies included individuals of either sex aged 18 years or older. A target lesion was defined primarily to assess signs of psoriasis, measuring 16 to 100 cm2, with a score of 3 (moderate) or higher for 2 of 3 different psoriasis signs—erythema, plaque elevation, and scaling—and summed score of 8 or higher, with no sign scoring less than 2. Participants who had pustular psoriasis or used phototherapy, photochemotherapy, or systemic psoriasis therapy within the prior 4 weeks or biologics within the prior 3 months, or those who were diagnosed with skin conditions that would interfere with the interpretation of results were excluded from the studies.

Study Oversight

Participants provided written informed consent before study-related procedures were performed, and the protocol and consent were approved by institutional review boards or ethics committees at all investigational sites. The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of Good Clinical Practice and the Declaration of Helsinki.

Efficacy Assessment

A 5-point scale ranging from 0 (clear) to 4 (severe) was used by the investigator at each study visit to assess the overall psoriasis severity of the treatable areas. Treatment success (the percentage of participants with at least a 2-grade improvement in baseline IGA score and a score of 0 [clear] or 1 [almost clear]) was evaluated at weeks 2, 4, 6, and 8, w

Signs of psoriasis at the target lesion were assessed at each visit using individual 5-point scales ranging from 0 (clear) to 4 (severe). Treatment success was defined as at least a 2-grade improvement from baseline score for each of the key signs—erythema, plaque elevation, and scaling—and reported at weeks 2, 4, 6, and 8, with a posttreatment follow-up at week 12.

Affected BSA also was evaluated at each visit. In addition, an IGA×BSA composite score was calculated by multiplying the IGA by the BSA (range, 9–48 [eg, maximum IGA=4 and maximum BSA=12]) at each time point. The mean percentage change in IGA×BSA from baseline was calculated for each study visit. Additional end points included the achievement of a 50%, 75%, and 90% or greater reduction from baseline IGA×BSA score—IGA×BSA-50, IGA×BSA-75, and IGA×BSA-90—at week 8.

Safety Assessment

Safety evaluations including adverse events (AEs), local skin reactions (LSRs), vital signs, laboratory evaluations, and physical examinations were performed. Information on reported and observed AEs was obtained at each visit. Routine safety laboratory tests were performed at screening, week 4, and week 8. An abbreviated physical examination was performed at baseline, week 8 (end of treatment), and week 12 (end of study). Treatment areas also were examined by the investigator at baseline and each subsequent visit for the presence or absence of marked known drug-related AEs including skin atrophy, striae, telangiectasia, and folliculitis.

LSR Assessment

Local skin reactions such as itching, dryness, and burning/stinging were evaluated at each study visit using 4-point scales ranging from 0 (clear) to 3 (severe). Given the nature of the disease, the presence of LSRs and symptoms at baseline is commonplace, and as such, these evaluations identified both improvement and any emergent issues.

Statistical Analysis

The primary study goal was to assess differences in treatment efficacy between HP lotion and vehicle with respect to IGA. All statistical processing was performed using SAS unless otherwise stated; statistical tests were 2-sided and performed at the 0.05 level of significance. Markov Chain Monte Carlo multiple imputation was the primary method used to handle missing efficacy data. No imputations were made for missing safety data. All participants were randomized, and the dispensed study drug was included in the intention-to-treat analysis set. This analysis was considered primary for the evaluation of efficacy. Data were analyzed using Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel tests, stratified by analysis center.

Body surface area data were analyzed in a post hoc analysis of covariance with factors of treatment and analysis center and baseline BSA as a covariate. P values for comparisons of percentage change in IGA×BSA were derived from a Wilcoxon rank sum test. For IGA×BSA-50, IGA×BSA-75, and IGA×BSA-90, P values were derived from a Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test. Last observation carried forward was used to impute data for IGA and BSA through week 8 prior to analysis.

The primary safety analysis was conducted at week 8 using the safety analysis set, which included all participants who were randomized, received at least 1 confirmed dose of the study drug, and had at least 1 postbaseline safety assessment. Adverse events were recorded and classified using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA, Version 18.0). A post hoc Wilcoxon rank sum test was conducted to compare itching, dryness, and burning/stinging scores at week 8 for HP lotion versus vehicle.

RESULTS

Participant Disposition

Overall, 430 participants were randomized (2:1) to HP lotion (n=285) or vehicle (n=145)(eFigure 1) and included in the intention-to-treat population. Across the 2 studies, 93.3% (n=266) of participants treated with HP lotion and 89.7% (n=130) of participants treated with vehicle completed treatment. The main reasons for study discontinuation with HP lotion were lost to follow-up (3.2%; n=9), participant request (1.8%; n=5), and AEs (1.4%; n=4). Participant request (4.8%; n=7), lost to follow-up (4.1%; n=6), and AEs (1.4%; n=2) also were the main reasons for treatment discontinuation in the vehicle arm.

A total of 426 participants were included in the safety population, with no postbaseline safety evaluation in 4 participants.

Baseline Participant Demographics

Demographic data were comparable across the 2 studies. The mean age (SD) was 52.6 (14.13) years. Overall, the majority of participants were male (58.8%; n=253) and white (86.5%; n=372)(eTable 1).

Baseline disease characteristics also were comparable across the treatment groups. Participants had moderate (86.3%; n=371) or severe (13.7%; n=59) disease, with a mean BSA (SD) of 6.1% (2.83) and mean size of target lesion (SD) of 40.4 cm2 (24.14). The majority of participants had moderate (erythema, 84.0%; plaque elevation, 76.0%; and scaling, 74.9%) or severe (erythema, 9.1%; plaque elevation, 13.0%; and scaling, 15.6%) signs of psoriasis at the target lesion site (eTable 2).

Efficacy Evaluation

IGA of Disease Severity

Halobetasol propionate lotion was consistently more effective than its vehicle in achieving treatment success (at least a 2-grade improvement in baseline IGA score and a score of 0 [clear] or 1 [almost clear]). Halobetasol propionate lotion demonstrated statistically significant superiority over vehicle as early as week 2 (P=.003). By week 8, 37.43% of participants in the HP lotion group achieved treatment success compared with 10.03% in the vehicle group (P<.001)(Figure 1).

Overall, 39% of participants who had moderate disease (IGA score, 3) at baseline were treatment successes with HP lotion at week 8 compared with 11.53% of participants treated with vehicle; 27.97% of participants with severe disease (IGA score, 4) were treatment successes, with at least a 3-grade improvement in IGA. No participants with severe psoriasis who were treated with vehicle achieved treatment success at week 8. Efficacy was similar in female and male participants, allowing for vehicle effects.

Severity of Signs of Psoriasis (Erythema, Plaque Elevation, and Scaling) at Target Lesion Site

Halobetasol propionate lotion was statistically superior to vehicle in reducing the psoriasis signs of erythema, plaque elevation, and scaling at the target lesion from week 2. At week 8, treatment success (at least a 2-grade improvement from baseline) was achieved by 51.48% (erythema), 57.64% (plaque elevation), and 58.98% (scaling) of participants compared with 17.85%, 23.61%, and 22.82%, respectively, with vehicle (all P<.001)(Figure 2).

BSA Assessment

Halobetasol propionate lotion was statistically superior to vehicle in reducing BSA from week 2. At week 8 there was a 35.20% reduction in mean BSA for HP lotion compared to 5.85% for vehicle (P<.001)(eFigure 2).

IGA×BSA Composite Score

At baseline, the mean IGA×BSA scores for HP lotion and vehicle were similar: 19.3 and 18.8, respectively. By week 8, the percentage change in mean IGA×BSA score with HP lotion was 49.44% compared to 13.35% with vehicle (P<.001). Differences were significant from week 2 (P<.001)(Figure 3).

By week 8, 56.8% of participants (n=162) treated with HP lotion had achieved a 50% or greater reduction in baseline IGA×BSA compared to 17.2% of participants treated with vehicle (P<.001). Reductions of IGA×BSA-75 and IGA×BSA-90 were achieved in 39.3% and 19.3% of participants treated with HP lotion, respectively, compared with 9.7% and 2.8% of participants treated with vehicle (both P<.001)(eFigure 3).

Safety Evaluation

Adverse event reports were low and similar between the active and vehicle groups. Overall, 61 participants (21.5%) treated with HP lotion reported AEs compared with 34 participants (23.9%) treated with vehicle (Table). The majority of participants treated with HP lotion (90.2%) had AEs that were mild or moderate. There was 1 AE of telangiectasia, not considered treatment related. There were 5 treatment-related AEs for HP lotion, all at the application site: dermatitis (0.7%; n=2), infection (0.4%; n=1), pruritus (0.4%; n=1), and discoloration (0.4%; n=1). There were no AE reports of skin atrophy or folliculitis.

Local Skin Reactions

Most LSRs at baseline were mild to moderate in severity. Itching was the most common, present in 76.8% of participants. Participant-reported burning/stinging was less common, reported by 40.6% of participants. Investigator-reported dryness was noted in 65.7% of participants. There was a rapid improvement in participant-reported itching as early as week 2 that was sustained to the end of the studies, with more gradual improvements in skin dryness and burning/stinging.

COMMENT

Plaque psoriasis is a chronic condition. The rationale behind the development of HP lotion 0.01% was to provide optimal topical treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis, allowing for the potential of prolonged use beyond the 2-week consecutive use normally applied to HP cream 0.05% in a light, once-daily, aesthetically pleasing lotion formulation that patients would prefer.

Treatment success was rapid and achieved in more than 37% of participants by week 8, with significant improvements in psoriasis signs and symptoms (erythema, plaque elevation, and scaling) compared with vehicle. However, IGA does not consider BSA involvement, a key aspect of disease severity,11,12 and improvements in psoriasis signs of erythema, plaque elevation, and scaling were only assessed at the target lesion. Recently, the product of the IGA and BSA involvement (IGA×BSA) has been proposed as a simple alternative for assessing response to therapy that has been consistently shown to be highly correlated with the psoriasis area and severity index.13-19 Halobetasol propionate lotion 0.01% achieved a 50% reduction in IGA×BSA score by week 8. This efficacy compares well with results reported with apremilast in patients with moderate plaque psoriasis.20

Achieving clinically meaningful outcomes is an important aspect of disease management, especially in psoriasis with its disease burden and detriment to quality of life. It has been suggested that achieving a 75% or greater reduction from baseline IGA×BSA score (IGA×BSA-75) is an appropriate clinical goal.20 In our investigation, IGA×BSA-75 was achieved by 39% of participants treated with HP lotion by week 8, which again compares favorably with 35% of participants in the apremilast study who achieved IGA×BSA-75 at week 16.20

Physicians continue to have long-term safety concerns with TCSs,4,11,12 participants remain concerned about the risk for skin thinning,13 and product labelling restricts HP cream 0.05% consecutive use to 2 weeks. In clinical experience, HP cream 0.05% is well tolerated, with potential local AEs similar to those experienced with other superpotent TCSs. In short-term clinical trials, local AEs at the site of application were reported in up to 13% of patients21-26; itching, burning, or stinging were the most common local AEs (reported in 4.4% of patients).27

There were minimal safety concerns in our 2 studies using an 8-week, once-daily treatment regimen with HP lotion 0.01%. Local AEs at the application site were reported in less than 1% of participants. Baseline itching, dryness, and burning/stinging all improved with treatment.

CONCLUSION