User login

Acroangiodermatitis of Mali and Stewart-Bluefarb Syndrome

Case Reports

Patient 1

A 56-year-old white man with a history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, sleep apnea, bilateral knee replacement, and cataract removal presented to the emergency department with a worsening rash on the left posterior medial leg of 6 months’ duration. He reported associated redness and tenderness with the plaques as well as increased swelling and firmness of the leg. He was admitted to the hospital where the infectious disease team treated him with cefazolin for presumed cellulitis. His condition did not improve, and another course of cefazolin was started in addition to oral fluconazole and clotrimazole–betamethasone dipropionate lotion for a possible fungal cause. Again, treatment provided no improvement.

He was then evaluated by dermatology. On physical examination, the patient had edema, warmth, and induration of the left lower leg. There also was an annular and serpiginous indurated plaque with minimal scale on the left lower leg (Figure 1). A firm, dark red to purple plaque on the left medial thigh with mild scale was present. There also was scaling of the right plantar foot.

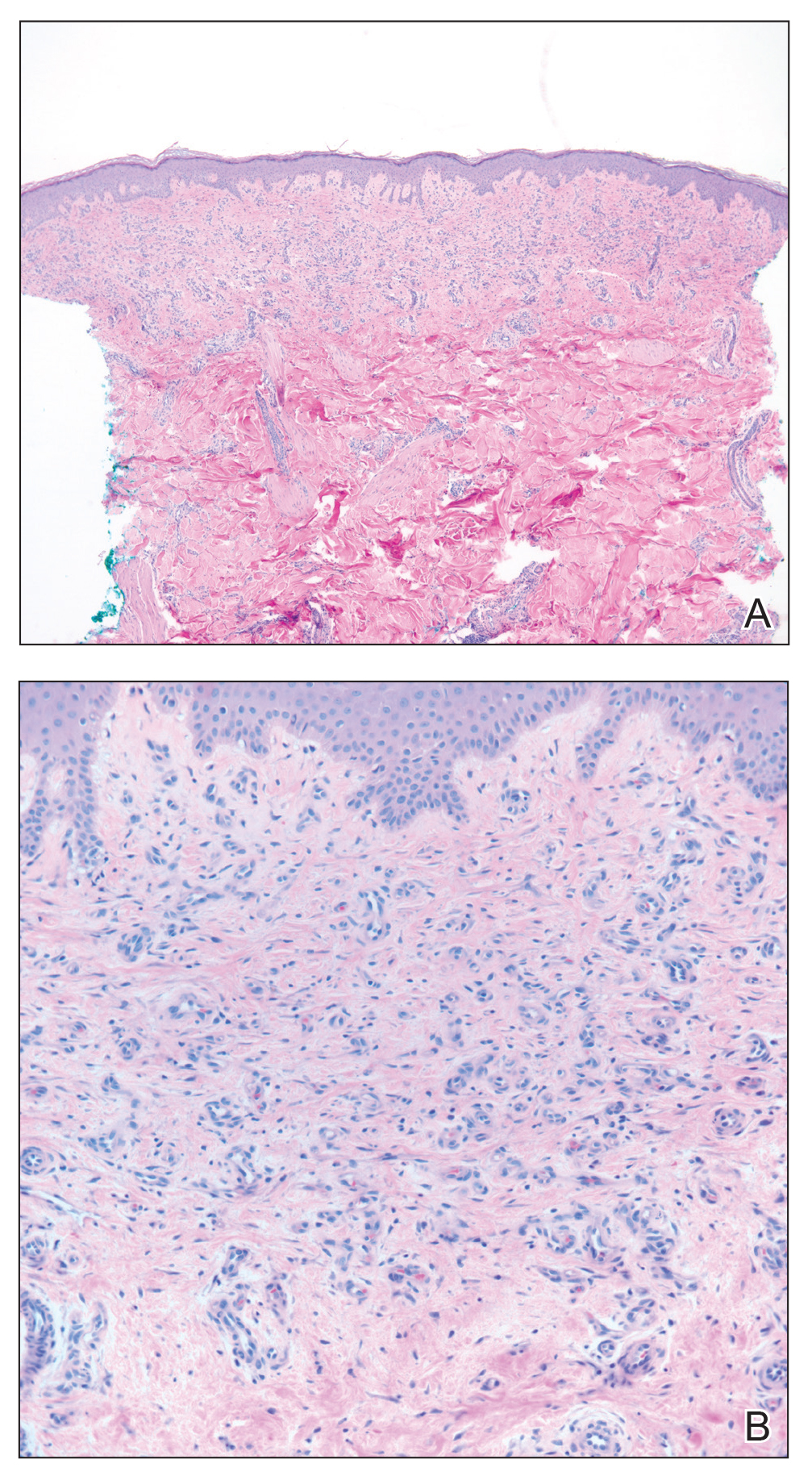

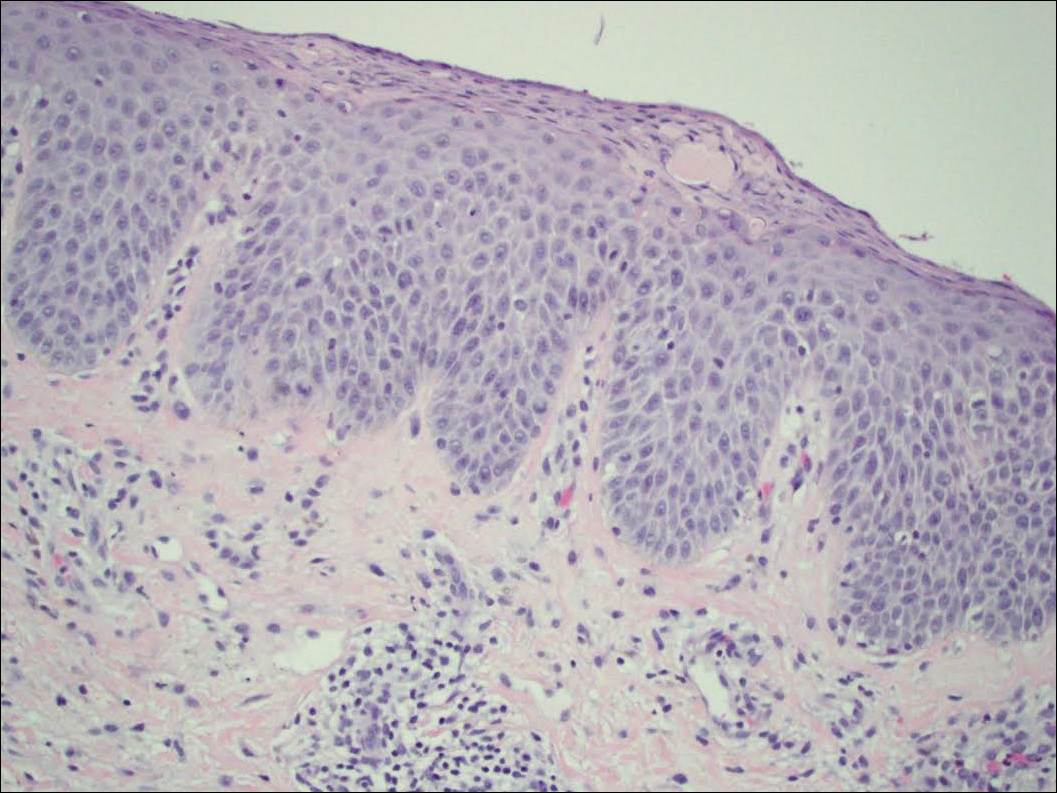

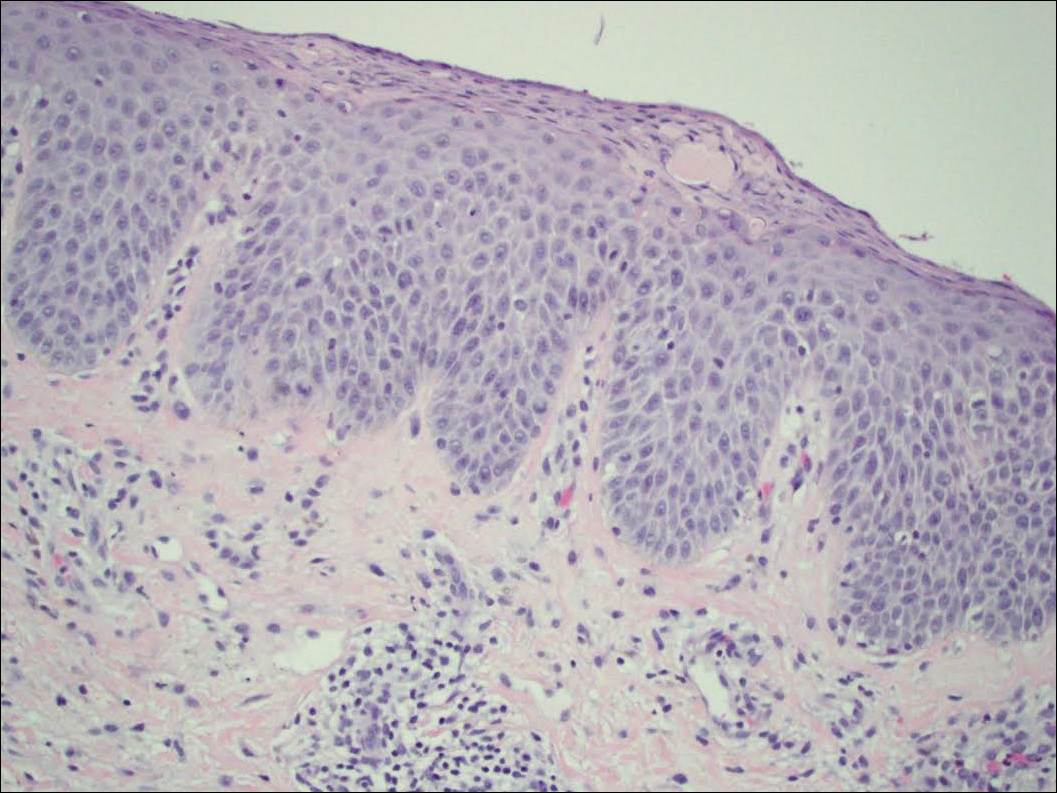

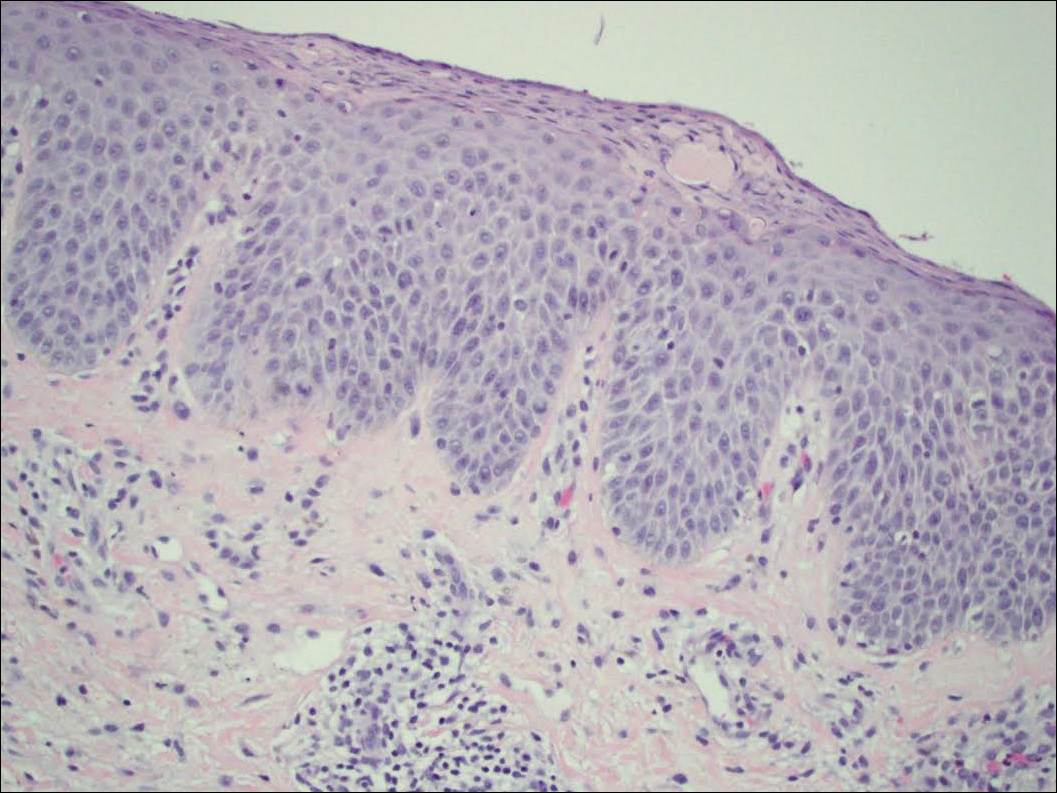

Skin biopsy revealed a dermal capillary proliferation with a scattering of inflammatory cells including eosinophils as well as dermal fibrosis (Figure 2). Periodic acid–Schiff and human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) immunostains were negative. Considering the degree and depth of vascular proliferation, Mali-type acroangiodermatitis (AAD) was the favored diagnosis.

Patient 2

A 72-year-old white man presented with a firm asymptomatic growth on the left dorsal forearm of 3 months’ duration. It was located near the site of a prior squamous cell carcinoma that was excised 1 year prior to presentation. The patient had no treatment or biopsy of the presenting lesion. His medical and surgical history included polycystic kidney disease and renal transplantation 4 years prior to presentation. He also had an arteriovenous fistula of the left arm. His other chronic diseases included chronic obstructive lung disease, congestive heart failure, hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and obstructive sleep apnea.

On physical examination, the patient had a 1-cm violaceous nodule on the extensor surface of the left mid forearm. An arteriovenous fistula was present proximal to the lesion on the left arm (Figure 3).

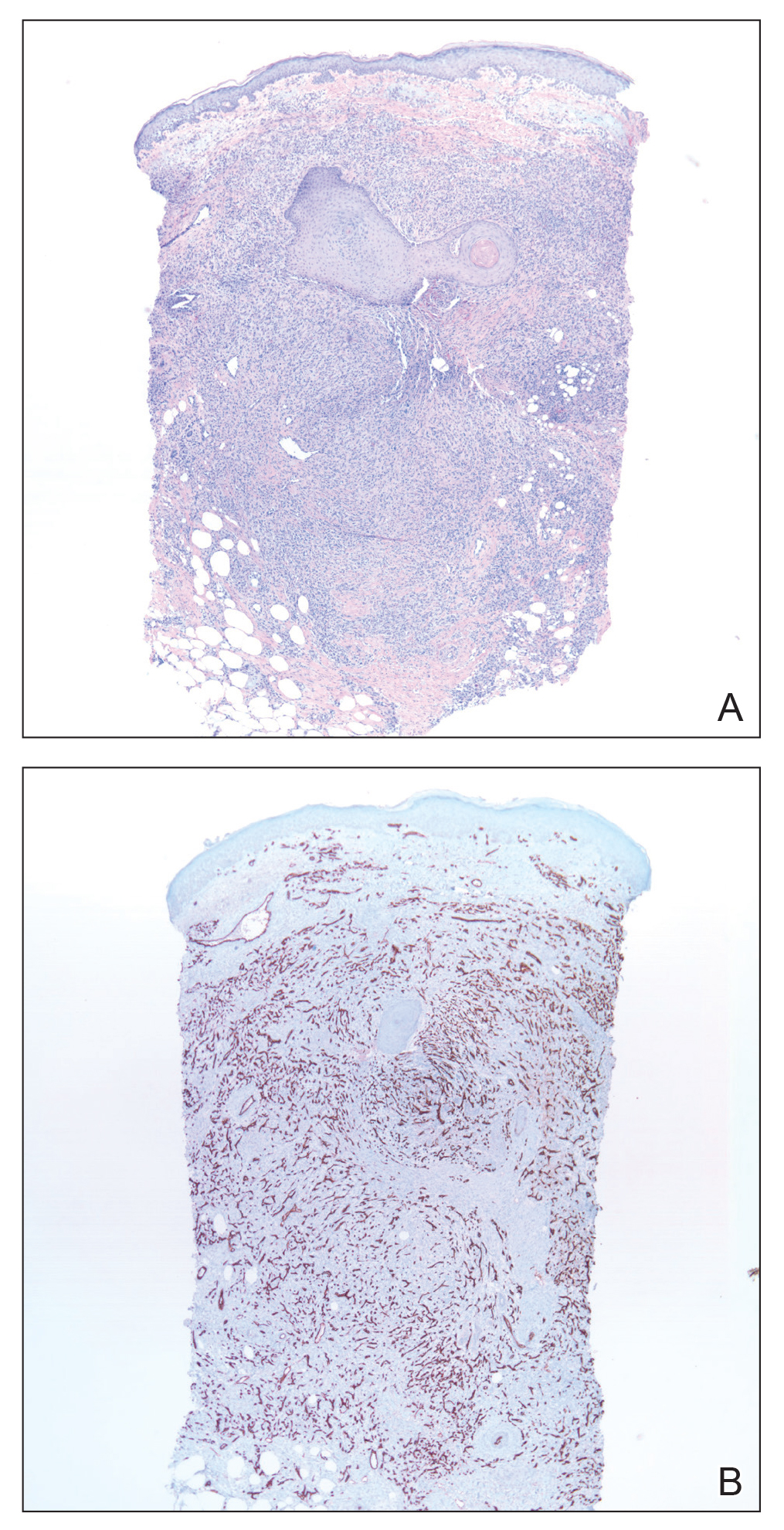

Skin biopsy revealed a tightly packed proliferation of small vascular channels that tested negative for HHV-8, tumor protein p63, and cytokeratin 5/6. Erythrocytes were noted in the lumen of some of these vessels. Neutrophils were scattered and clustered throughout the specimen (Figure 4A). Blood vessels were highlighted with CD34 (Figure 4B). Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stain was negative for infectious agents. These findings favored AAD secondary to an arteriovenous malformation, consistent with Stewart-Bluefarb syndrome (SBS).

Comment

Presentation of AAD

Acroangiodermatitis is a rare chronic inflammatory skin process involving a reactive proliferation of capillaries and fibrosis of the skin that resembles Kaposi sarcoma both clinically and histopathologically. The condition has been reported in patients with chronic venous insufficiency,1 congenital arteriovenous malformation,2 acquired iatrogenic arteriovenous fistula,3 paralyzed extremity,4 suction socket lower limb prosthesis (amputees),5 and minor trauma.6-8 The lesions of AAD tend to be circumscribed, slowly evolving, red-violaceous (or brown or dusky) macules, papules, or plaques that may become verrucous or develop into painful ulcerations. They generally occur on the distal dorsal aspects of the lower legs and feet.110

Variants of AAD

Mali et al9 first reported cutaneous manifestations resembling Kaposi sarcoma in 18 patients with chronic venous insufficiency in 1965. Two years later, Bluefarb and Adams10 described kaposiform skin lesions in one patient with a congenital arteriovenous malformation without chronic venous insufficiency. It was not until 1974, however, that Earhart et al11 proposed the term pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma.10,11 Based on these findings, AAD is described as 2 variants: Mali type and SBS.

Mali-type AAD is more common and typically occurs in elderly men. It classically presents bilaterally on the lower extremities in association with severe chronic venous insufficiency.5 Skin lesions usually occur on the medial aspect of the lower legs (as in patient 1), dorsum of the heel, hallux, or second toe.12

The etiology of Mali-type AAD is poorly understood. The leading theory is that the condition involves reduced perfusion due to chronic edema, resulting in neovascularization, fibroblast proliferation, hypertrophy, and inflammatory skin changes. When AAD occurs in the setting of a suction socket prosthesis, the negative pressure of the stump-socket environment is thought to alter local circulation, leading to proliferation of small blood vessels.5,13

Stewart-Bluefarb syndrome usually involves a single extremity in young adults with congenital arteriovenous malformations, amputees, and individuals with hemiplegia or iatrogenic arteriovenous fistulae (as in patient 2).1 It was once thought to occur secondary to Klippel-Trenaunay-Weber syndrome; however, SBS rarely is accompanied by limb hypertrophy.9 Pathogenesis is thought to involve an angiogenic response to a high perfusion rate and high oxygen saturation, which leads to fibroblast proliferation and reactive endothelial hyperplasia.1,14

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

Prompt identification of an underlying arteriovenous anomaly is critical, given the sequelae of high-flow shunts, which may result in skin ulceration, limb length discrepancy, cortical thinning of bone with regional osteoporosis, and congestive heart failure.1,5 Duplex ultrasonography is the first-line diagnostic modality because it is noninvasive and widely available. The key doppler feature of an arteriovenous malformation is low resistance and high diastolic pulsatile flow,1 which should be confirmed with magnetic resonance angiography or computed tomography angiography if present on ultrasonography.

The differential diagnosis of AAD includes Kaposi sarcoma, reactive angioendotheliomatosis, diffuse dermal angiomatosis, intravascular histiocytosis, glomeruloid angioendotheliomatosis, and angiopericytomatosis.15,16 These entities present as multiple erythematous, violaceous, purpuric patches and plaques generally on the extremities but can have a widely varied distribution. Some lesions evolve to necrosis or ulceration. Histopathologic analysis is useful to differentiate these entities.

Histopathology

The histopathologic features of AAD can be nonspecific; clinicopathologic correlation often is necessary to establish the diagnosis. Features include a proliferation of small thick-walled vessels, often in a lobular arrangement, in an edematous papillary dermis. Small thrombi may be observed. There may be increased fibroblasts; plump endothelial cells; a superficial mixed infiltrate comprised of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and eosinophils; and deposition of hemosiderin.2,5 These characteristics overlap with features of Kaposi sarcoma; AAD, however, lacks slitlike vascular spaces, perivascular CD34+ expression, and nuclear atypia. A negative HHV-8 stain will assist in ruling out Kaposi sarcoma.1,17

Management

Treatment reports are anecdotal. The goal is to correct underlying venous hypertension. Conservative measures with compression garments, intermittent pneumatic compression, and limb elevation are first line.18 Oral antibiotics and local wound care with topical emollients and corticosteroids have been shown to be effective treatments.19-21

Oral erythromycin 500 mg 4 times daily for 3 weeks and clobetasol propionate cream 0.05% healed a lower extremity ulcer in a patient with Mali-type AAD.21 In another patient, conservative treatment of Mali-type AAD failed, but rapid improvement of 2 lower extremity ulcers resulted after 3 weeks of oral dapsone 50 mg twice daily.22

Conclusion

Acroangiodermatitis is a rare entity that is characterized by erythematous violaceous papules and plaques of the extremities, commonly in the setting of chronic venous insufficiency or an arteriovenous shunt. Histopathologic analysis shows proliferation of capillaries with fibrosis, extravasation of erythrocytes, and deposition of hemosiderin without the spindle cells and slitlike vascular spaces characteristic of Kaposi sarcoma. Detection of an underlying arteriovenous malformation is essential, as the disease can have local and systemic consequences, such as skin ulceration and congestive heart failure.1 Treatment options are conservative, directed toward local wound care, compression, and management of complications, such as ulceration and infection, as well as obliterating any underlying arteriovenous malformation.

- Parsi K, O’Connor AA, Bester L. Stewart-Bluefarb syndrome: report of five cases and a review of literature. Phlebology. 2015;30:505-514.

- Larralde M, Gonzalez V, Marietti R, et al. Pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma with arteriovenous malformation. Pediatr Dermatol. 2001;18:325-327.

- Nakanishi G, Tachibana T, Soga H, et al. Pseudo-Kaposi’s sarcoma of the hand associated with acquired iatrogenic arteriovenous fistula. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:415-416.

- Landthaler M, Langehenke H, Holzmann H, et al. Mali’s acroangiodermatitis (pseudo-Kaposi) in paralyzed legs. Hautarzt. 1988;39:304-307.

- Trindade F, Requena L. Pseudo-Kaposi’s sarcoma because of suction socket lower limb prosthesis. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:482-485.

- Yu-Lu W, Tao Q, Hong-Zhong J, et al. Non-tender pedal plaques and nodules: pseudo-Kaposi’s sarcoma (Stewart-Bluefarb type) induced by trauma. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2015;13:927-930.

- Del-Río E, Aguilar A, Ambrojo P, et al. Pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma induced by minor trauma in a patient with Klippel-Trenaunay-Weber syndrome. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1993;18:151-153.

- Archie M, Khademi S, Aungst D, et al. A rare case of acroangiodermatitis associated with a congenital arteriovenous malformation (Stewart-Bluefarb Syndrome) in a young veteran: case report and review of the literature. Ann Vasc Surg. 2015;29:1448.e5-1448.e10.

- Mali JW, Kuiper JP, Hamers AA. Acro-angiodermatitis of the foot. Arch Dermatol. 1965;92:515-518.

- Bluefarb SM, Adams LA. Arteriovenous malformation with angiodermatitis. stasis dermatitis simulating Kaposi’s disease. Arch Dermatol. 1967;96:176-181.

- Earhart RN, Aeling JA, Nuss DD, et al. Pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma. A patient with arteriovenous malformation and skin lesions simulating Kaposi sarcoma. Arch Dermatol. 1974;110:907-910.

- Lugovic´ L, Pusic´ J, Situm M, et al. Acroangiodermatitis (pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma): three case reports. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2007;15:152-157.

- Horiguchi Y, Takahashi K, Tanizaki H, et al. Case of bilateral acroangiodermatitis due to symmetrical arteriovenous fistulas of the soles. J Dermatol. 2015;42:989-991.

- Dog˘an S, Boztepe G, Karaduman A. Pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma: a challenging vascular phenomenon. Dermatol Online J. 2007;13:22.

- Mazloom SE, Stallings A, Kyei A. Differentiating intralymphatic histiocytosis, intravascular histiocytosis, and subtypes of reactive angioendotheliomatosis: review of clinical and histologic features of all cases reported to date. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:33-39.

- Rongioletti F, Rebora A. Cutaneous reactive angiomatoses: patterns and classification of reactive vascular proliferation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:887-896.

- Kanitakis J, Narvaez D, Claudy A. Expression of the CD34 antigen distinguishes Kaposi’s sarcoma from pseudo-Kaposi’s sarcoma (acroangiodermatitis). Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:44-46.

- Pires A, Depairon M, Ricci C, et al. Effect of compression therapy on a pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma. Dermatology. 1999;198:439-441.

- Hayek S, Atiyeh B, Zgheib E. Stewart-Bluefarb syndrome: review of the literature and case report of chronic ulcer treatment with heparan sulphate (Cacipliq20®). Int Wound J. 2015;12:169-172.

- Varyani N, Thukral A, Kumar N, et al. Nonhealing ulcer: acroangiodermatitis of Mali. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2011;2011:909383.

- Mehta AA, Pereira RR, Nayak C, et al. Acroangiodermatitis of Mali: a rare vascular phenomenon. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2010;76:553-556.

- Rashkovsky I, Gilead L, Schamroth J, et al. Acro-angiodermatitis: review of the literature and report of a case. Acta Derm Venereol. 1995;75:475-478.

Case Reports

Patient 1

A 56-year-old white man with a history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, sleep apnea, bilateral knee replacement, and cataract removal presented to the emergency department with a worsening rash on the left posterior medial leg of 6 months’ duration. He reported associated redness and tenderness with the plaques as well as increased swelling and firmness of the leg. He was admitted to the hospital where the infectious disease team treated him with cefazolin for presumed cellulitis. His condition did not improve, and another course of cefazolin was started in addition to oral fluconazole and clotrimazole–betamethasone dipropionate lotion for a possible fungal cause. Again, treatment provided no improvement.

He was then evaluated by dermatology. On physical examination, the patient had edema, warmth, and induration of the left lower leg. There also was an annular and serpiginous indurated plaque with minimal scale on the left lower leg (Figure 1). A firm, dark red to purple plaque on the left medial thigh with mild scale was present. There also was scaling of the right plantar foot.

Skin biopsy revealed a dermal capillary proliferation with a scattering of inflammatory cells including eosinophils as well as dermal fibrosis (Figure 2). Periodic acid–Schiff and human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) immunostains were negative. Considering the degree and depth of vascular proliferation, Mali-type acroangiodermatitis (AAD) was the favored diagnosis.

Patient 2

A 72-year-old white man presented with a firm asymptomatic growth on the left dorsal forearm of 3 months’ duration. It was located near the site of a prior squamous cell carcinoma that was excised 1 year prior to presentation. The patient had no treatment or biopsy of the presenting lesion. His medical and surgical history included polycystic kidney disease and renal transplantation 4 years prior to presentation. He also had an arteriovenous fistula of the left arm. His other chronic diseases included chronic obstructive lung disease, congestive heart failure, hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and obstructive sleep apnea.

On physical examination, the patient had a 1-cm violaceous nodule on the extensor surface of the left mid forearm. An arteriovenous fistula was present proximal to the lesion on the left arm (Figure 3).

Skin biopsy revealed a tightly packed proliferation of small vascular channels that tested negative for HHV-8, tumor protein p63, and cytokeratin 5/6. Erythrocytes were noted in the lumen of some of these vessels. Neutrophils were scattered and clustered throughout the specimen (Figure 4A). Blood vessels were highlighted with CD34 (Figure 4B). Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stain was negative for infectious agents. These findings favored AAD secondary to an arteriovenous malformation, consistent with Stewart-Bluefarb syndrome (SBS).

Comment

Presentation of AAD

Acroangiodermatitis is a rare chronic inflammatory skin process involving a reactive proliferation of capillaries and fibrosis of the skin that resembles Kaposi sarcoma both clinically and histopathologically. The condition has been reported in patients with chronic venous insufficiency,1 congenital arteriovenous malformation,2 acquired iatrogenic arteriovenous fistula,3 paralyzed extremity,4 suction socket lower limb prosthesis (amputees),5 and minor trauma.6-8 The lesions of AAD tend to be circumscribed, slowly evolving, red-violaceous (or brown or dusky) macules, papules, or plaques that may become verrucous or develop into painful ulcerations. They generally occur on the distal dorsal aspects of the lower legs and feet.110

Variants of AAD

Mali et al9 first reported cutaneous manifestations resembling Kaposi sarcoma in 18 patients with chronic venous insufficiency in 1965. Two years later, Bluefarb and Adams10 described kaposiform skin lesions in one patient with a congenital arteriovenous malformation without chronic venous insufficiency. It was not until 1974, however, that Earhart et al11 proposed the term pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma.10,11 Based on these findings, AAD is described as 2 variants: Mali type and SBS.

Mali-type AAD is more common and typically occurs in elderly men. It classically presents bilaterally on the lower extremities in association with severe chronic venous insufficiency.5 Skin lesions usually occur on the medial aspect of the lower legs (as in patient 1), dorsum of the heel, hallux, or second toe.12

The etiology of Mali-type AAD is poorly understood. The leading theory is that the condition involves reduced perfusion due to chronic edema, resulting in neovascularization, fibroblast proliferation, hypertrophy, and inflammatory skin changes. When AAD occurs in the setting of a suction socket prosthesis, the negative pressure of the stump-socket environment is thought to alter local circulation, leading to proliferation of small blood vessels.5,13

Stewart-Bluefarb syndrome usually involves a single extremity in young adults with congenital arteriovenous malformations, amputees, and individuals with hemiplegia or iatrogenic arteriovenous fistulae (as in patient 2).1 It was once thought to occur secondary to Klippel-Trenaunay-Weber syndrome; however, SBS rarely is accompanied by limb hypertrophy.9 Pathogenesis is thought to involve an angiogenic response to a high perfusion rate and high oxygen saturation, which leads to fibroblast proliferation and reactive endothelial hyperplasia.1,14

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

Prompt identification of an underlying arteriovenous anomaly is critical, given the sequelae of high-flow shunts, which may result in skin ulceration, limb length discrepancy, cortical thinning of bone with regional osteoporosis, and congestive heart failure.1,5 Duplex ultrasonography is the first-line diagnostic modality because it is noninvasive and widely available. The key doppler feature of an arteriovenous malformation is low resistance and high diastolic pulsatile flow,1 which should be confirmed with magnetic resonance angiography or computed tomography angiography if present on ultrasonography.

The differential diagnosis of AAD includes Kaposi sarcoma, reactive angioendotheliomatosis, diffuse dermal angiomatosis, intravascular histiocytosis, glomeruloid angioendotheliomatosis, and angiopericytomatosis.15,16 These entities present as multiple erythematous, violaceous, purpuric patches and plaques generally on the extremities but can have a widely varied distribution. Some lesions evolve to necrosis or ulceration. Histopathologic analysis is useful to differentiate these entities.

Histopathology

The histopathologic features of AAD can be nonspecific; clinicopathologic correlation often is necessary to establish the diagnosis. Features include a proliferation of small thick-walled vessels, often in a lobular arrangement, in an edematous papillary dermis. Small thrombi may be observed. There may be increased fibroblasts; plump endothelial cells; a superficial mixed infiltrate comprised of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and eosinophils; and deposition of hemosiderin.2,5 These characteristics overlap with features of Kaposi sarcoma; AAD, however, lacks slitlike vascular spaces, perivascular CD34+ expression, and nuclear atypia. A negative HHV-8 stain will assist in ruling out Kaposi sarcoma.1,17

Management

Treatment reports are anecdotal. The goal is to correct underlying venous hypertension. Conservative measures with compression garments, intermittent pneumatic compression, and limb elevation are first line.18 Oral antibiotics and local wound care with topical emollients and corticosteroids have been shown to be effective treatments.19-21

Oral erythromycin 500 mg 4 times daily for 3 weeks and clobetasol propionate cream 0.05% healed a lower extremity ulcer in a patient with Mali-type AAD.21 In another patient, conservative treatment of Mali-type AAD failed, but rapid improvement of 2 lower extremity ulcers resulted after 3 weeks of oral dapsone 50 mg twice daily.22

Conclusion

Acroangiodermatitis is a rare entity that is characterized by erythematous violaceous papules and plaques of the extremities, commonly in the setting of chronic venous insufficiency or an arteriovenous shunt. Histopathologic analysis shows proliferation of capillaries with fibrosis, extravasation of erythrocytes, and deposition of hemosiderin without the spindle cells and slitlike vascular spaces characteristic of Kaposi sarcoma. Detection of an underlying arteriovenous malformation is essential, as the disease can have local and systemic consequences, such as skin ulceration and congestive heart failure.1 Treatment options are conservative, directed toward local wound care, compression, and management of complications, such as ulceration and infection, as well as obliterating any underlying arteriovenous malformation.

Case Reports

Patient 1

A 56-year-old white man with a history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, sleep apnea, bilateral knee replacement, and cataract removal presented to the emergency department with a worsening rash on the left posterior medial leg of 6 months’ duration. He reported associated redness and tenderness with the plaques as well as increased swelling and firmness of the leg. He was admitted to the hospital where the infectious disease team treated him with cefazolin for presumed cellulitis. His condition did not improve, and another course of cefazolin was started in addition to oral fluconazole and clotrimazole–betamethasone dipropionate lotion for a possible fungal cause. Again, treatment provided no improvement.

He was then evaluated by dermatology. On physical examination, the patient had edema, warmth, and induration of the left lower leg. There also was an annular and serpiginous indurated plaque with minimal scale on the left lower leg (Figure 1). A firm, dark red to purple plaque on the left medial thigh with mild scale was present. There also was scaling of the right plantar foot.

Skin biopsy revealed a dermal capillary proliferation with a scattering of inflammatory cells including eosinophils as well as dermal fibrosis (Figure 2). Periodic acid–Schiff and human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) immunostains were negative. Considering the degree and depth of vascular proliferation, Mali-type acroangiodermatitis (AAD) was the favored diagnosis.

Patient 2

A 72-year-old white man presented with a firm asymptomatic growth on the left dorsal forearm of 3 months’ duration. It was located near the site of a prior squamous cell carcinoma that was excised 1 year prior to presentation. The patient had no treatment or biopsy of the presenting lesion. His medical and surgical history included polycystic kidney disease and renal transplantation 4 years prior to presentation. He also had an arteriovenous fistula of the left arm. His other chronic diseases included chronic obstructive lung disease, congestive heart failure, hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and obstructive sleep apnea.

On physical examination, the patient had a 1-cm violaceous nodule on the extensor surface of the left mid forearm. An arteriovenous fistula was present proximal to the lesion on the left arm (Figure 3).

Skin biopsy revealed a tightly packed proliferation of small vascular channels that tested negative for HHV-8, tumor protein p63, and cytokeratin 5/6. Erythrocytes were noted in the lumen of some of these vessels. Neutrophils were scattered and clustered throughout the specimen (Figure 4A). Blood vessels were highlighted with CD34 (Figure 4B). Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stain was negative for infectious agents. These findings favored AAD secondary to an arteriovenous malformation, consistent with Stewart-Bluefarb syndrome (SBS).

Comment

Presentation of AAD

Acroangiodermatitis is a rare chronic inflammatory skin process involving a reactive proliferation of capillaries and fibrosis of the skin that resembles Kaposi sarcoma both clinically and histopathologically. The condition has been reported in patients with chronic venous insufficiency,1 congenital arteriovenous malformation,2 acquired iatrogenic arteriovenous fistula,3 paralyzed extremity,4 suction socket lower limb prosthesis (amputees),5 and minor trauma.6-8 The lesions of AAD tend to be circumscribed, slowly evolving, red-violaceous (or brown or dusky) macules, papules, or plaques that may become verrucous or develop into painful ulcerations. They generally occur on the distal dorsal aspects of the lower legs and feet.110

Variants of AAD

Mali et al9 first reported cutaneous manifestations resembling Kaposi sarcoma in 18 patients with chronic venous insufficiency in 1965. Two years later, Bluefarb and Adams10 described kaposiform skin lesions in one patient with a congenital arteriovenous malformation without chronic venous insufficiency. It was not until 1974, however, that Earhart et al11 proposed the term pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma.10,11 Based on these findings, AAD is described as 2 variants: Mali type and SBS.

Mali-type AAD is more common and typically occurs in elderly men. It classically presents bilaterally on the lower extremities in association with severe chronic venous insufficiency.5 Skin lesions usually occur on the medial aspect of the lower legs (as in patient 1), dorsum of the heel, hallux, or second toe.12

The etiology of Mali-type AAD is poorly understood. The leading theory is that the condition involves reduced perfusion due to chronic edema, resulting in neovascularization, fibroblast proliferation, hypertrophy, and inflammatory skin changes. When AAD occurs in the setting of a suction socket prosthesis, the negative pressure of the stump-socket environment is thought to alter local circulation, leading to proliferation of small blood vessels.5,13

Stewart-Bluefarb syndrome usually involves a single extremity in young adults with congenital arteriovenous malformations, amputees, and individuals with hemiplegia or iatrogenic arteriovenous fistulae (as in patient 2).1 It was once thought to occur secondary to Klippel-Trenaunay-Weber syndrome; however, SBS rarely is accompanied by limb hypertrophy.9 Pathogenesis is thought to involve an angiogenic response to a high perfusion rate and high oxygen saturation, which leads to fibroblast proliferation and reactive endothelial hyperplasia.1,14

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

Prompt identification of an underlying arteriovenous anomaly is critical, given the sequelae of high-flow shunts, which may result in skin ulceration, limb length discrepancy, cortical thinning of bone with regional osteoporosis, and congestive heart failure.1,5 Duplex ultrasonography is the first-line diagnostic modality because it is noninvasive and widely available. The key doppler feature of an arteriovenous malformation is low resistance and high diastolic pulsatile flow,1 which should be confirmed with magnetic resonance angiography or computed tomography angiography if present on ultrasonography.

The differential diagnosis of AAD includes Kaposi sarcoma, reactive angioendotheliomatosis, diffuse dermal angiomatosis, intravascular histiocytosis, glomeruloid angioendotheliomatosis, and angiopericytomatosis.15,16 These entities present as multiple erythematous, violaceous, purpuric patches and plaques generally on the extremities but can have a widely varied distribution. Some lesions evolve to necrosis or ulceration. Histopathologic analysis is useful to differentiate these entities.

Histopathology

The histopathologic features of AAD can be nonspecific; clinicopathologic correlation often is necessary to establish the diagnosis. Features include a proliferation of small thick-walled vessels, often in a lobular arrangement, in an edematous papillary dermis. Small thrombi may be observed. There may be increased fibroblasts; plump endothelial cells; a superficial mixed infiltrate comprised of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and eosinophils; and deposition of hemosiderin.2,5 These characteristics overlap with features of Kaposi sarcoma; AAD, however, lacks slitlike vascular spaces, perivascular CD34+ expression, and nuclear atypia. A negative HHV-8 stain will assist in ruling out Kaposi sarcoma.1,17

Management

Treatment reports are anecdotal. The goal is to correct underlying venous hypertension. Conservative measures with compression garments, intermittent pneumatic compression, and limb elevation are first line.18 Oral antibiotics and local wound care with topical emollients and corticosteroids have been shown to be effective treatments.19-21

Oral erythromycin 500 mg 4 times daily for 3 weeks and clobetasol propionate cream 0.05% healed a lower extremity ulcer in a patient with Mali-type AAD.21 In another patient, conservative treatment of Mali-type AAD failed, but rapid improvement of 2 lower extremity ulcers resulted after 3 weeks of oral dapsone 50 mg twice daily.22

Conclusion

Acroangiodermatitis is a rare entity that is characterized by erythematous violaceous papules and plaques of the extremities, commonly in the setting of chronic venous insufficiency or an arteriovenous shunt. Histopathologic analysis shows proliferation of capillaries with fibrosis, extravasation of erythrocytes, and deposition of hemosiderin without the spindle cells and slitlike vascular spaces characteristic of Kaposi sarcoma. Detection of an underlying arteriovenous malformation is essential, as the disease can have local and systemic consequences, such as skin ulceration and congestive heart failure.1 Treatment options are conservative, directed toward local wound care, compression, and management of complications, such as ulceration and infection, as well as obliterating any underlying arteriovenous malformation.

- Parsi K, O’Connor AA, Bester L. Stewart-Bluefarb syndrome: report of five cases and a review of literature. Phlebology. 2015;30:505-514.

- Larralde M, Gonzalez V, Marietti R, et al. Pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma with arteriovenous malformation. Pediatr Dermatol. 2001;18:325-327.

- Nakanishi G, Tachibana T, Soga H, et al. Pseudo-Kaposi’s sarcoma of the hand associated with acquired iatrogenic arteriovenous fistula. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:415-416.

- Landthaler M, Langehenke H, Holzmann H, et al. Mali’s acroangiodermatitis (pseudo-Kaposi) in paralyzed legs. Hautarzt. 1988;39:304-307.

- Trindade F, Requena L. Pseudo-Kaposi’s sarcoma because of suction socket lower limb prosthesis. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:482-485.

- Yu-Lu W, Tao Q, Hong-Zhong J, et al. Non-tender pedal plaques and nodules: pseudo-Kaposi’s sarcoma (Stewart-Bluefarb type) induced by trauma. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2015;13:927-930.

- Del-Río E, Aguilar A, Ambrojo P, et al. Pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma induced by minor trauma in a patient with Klippel-Trenaunay-Weber syndrome. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1993;18:151-153.

- Archie M, Khademi S, Aungst D, et al. A rare case of acroangiodermatitis associated with a congenital arteriovenous malformation (Stewart-Bluefarb Syndrome) in a young veteran: case report and review of the literature. Ann Vasc Surg. 2015;29:1448.e5-1448.e10.

- Mali JW, Kuiper JP, Hamers AA. Acro-angiodermatitis of the foot. Arch Dermatol. 1965;92:515-518.

- Bluefarb SM, Adams LA. Arteriovenous malformation with angiodermatitis. stasis dermatitis simulating Kaposi’s disease. Arch Dermatol. 1967;96:176-181.

- Earhart RN, Aeling JA, Nuss DD, et al. Pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma. A patient with arteriovenous malformation and skin lesions simulating Kaposi sarcoma. Arch Dermatol. 1974;110:907-910.

- Lugovic´ L, Pusic´ J, Situm M, et al. Acroangiodermatitis (pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma): three case reports. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2007;15:152-157.

- Horiguchi Y, Takahashi K, Tanizaki H, et al. Case of bilateral acroangiodermatitis due to symmetrical arteriovenous fistulas of the soles. J Dermatol. 2015;42:989-991.

- Dog˘an S, Boztepe G, Karaduman A. Pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma: a challenging vascular phenomenon. Dermatol Online J. 2007;13:22.

- Mazloom SE, Stallings A, Kyei A. Differentiating intralymphatic histiocytosis, intravascular histiocytosis, and subtypes of reactive angioendotheliomatosis: review of clinical and histologic features of all cases reported to date. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:33-39.

- Rongioletti F, Rebora A. Cutaneous reactive angiomatoses: patterns and classification of reactive vascular proliferation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:887-896.

- Kanitakis J, Narvaez D, Claudy A. Expression of the CD34 antigen distinguishes Kaposi’s sarcoma from pseudo-Kaposi’s sarcoma (acroangiodermatitis). Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:44-46.

- Pires A, Depairon M, Ricci C, et al. Effect of compression therapy on a pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma. Dermatology. 1999;198:439-441.

- Hayek S, Atiyeh B, Zgheib E. Stewart-Bluefarb syndrome: review of the literature and case report of chronic ulcer treatment with heparan sulphate (Cacipliq20®). Int Wound J. 2015;12:169-172.

- Varyani N, Thukral A, Kumar N, et al. Nonhealing ulcer: acroangiodermatitis of Mali. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2011;2011:909383.

- Mehta AA, Pereira RR, Nayak C, et al. Acroangiodermatitis of Mali: a rare vascular phenomenon. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2010;76:553-556.

- Rashkovsky I, Gilead L, Schamroth J, et al. Acro-angiodermatitis: review of the literature and report of a case. Acta Derm Venereol. 1995;75:475-478.

- Parsi K, O’Connor AA, Bester L. Stewart-Bluefarb syndrome: report of five cases and a review of literature. Phlebology. 2015;30:505-514.

- Larralde M, Gonzalez V, Marietti R, et al. Pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma with arteriovenous malformation. Pediatr Dermatol. 2001;18:325-327.

- Nakanishi G, Tachibana T, Soga H, et al. Pseudo-Kaposi’s sarcoma of the hand associated with acquired iatrogenic arteriovenous fistula. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:415-416.

- Landthaler M, Langehenke H, Holzmann H, et al. Mali’s acroangiodermatitis (pseudo-Kaposi) in paralyzed legs. Hautarzt. 1988;39:304-307.

- Trindade F, Requena L. Pseudo-Kaposi’s sarcoma because of suction socket lower limb prosthesis. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:482-485.

- Yu-Lu W, Tao Q, Hong-Zhong J, et al. Non-tender pedal plaques and nodules: pseudo-Kaposi’s sarcoma (Stewart-Bluefarb type) induced by trauma. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2015;13:927-930.

- Del-Río E, Aguilar A, Ambrojo P, et al. Pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma induced by minor trauma in a patient with Klippel-Trenaunay-Weber syndrome. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1993;18:151-153.

- Archie M, Khademi S, Aungst D, et al. A rare case of acroangiodermatitis associated with a congenital arteriovenous malformation (Stewart-Bluefarb Syndrome) in a young veteran: case report and review of the literature. Ann Vasc Surg. 2015;29:1448.e5-1448.e10.

- Mali JW, Kuiper JP, Hamers AA. Acro-angiodermatitis of the foot. Arch Dermatol. 1965;92:515-518.

- Bluefarb SM, Adams LA. Arteriovenous malformation with angiodermatitis. stasis dermatitis simulating Kaposi’s disease. Arch Dermatol. 1967;96:176-181.

- Earhart RN, Aeling JA, Nuss DD, et al. Pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma. A patient with arteriovenous malformation and skin lesions simulating Kaposi sarcoma. Arch Dermatol. 1974;110:907-910.

- Lugovic´ L, Pusic´ J, Situm M, et al. Acroangiodermatitis (pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma): three case reports. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2007;15:152-157.

- Horiguchi Y, Takahashi K, Tanizaki H, et al. Case of bilateral acroangiodermatitis due to symmetrical arteriovenous fistulas of the soles. J Dermatol. 2015;42:989-991.

- Dog˘an S, Boztepe G, Karaduman A. Pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma: a challenging vascular phenomenon. Dermatol Online J. 2007;13:22.

- Mazloom SE, Stallings A, Kyei A. Differentiating intralymphatic histiocytosis, intravascular histiocytosis, and subtypes of reactive angioendotheliomatosis: review of clinical and histologic features of all cases reported to date. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:33-39.

- Rongioletti F, Rebora A. Cutaneous reactive angiomatoses: patterns and classification of reactive vascular proliferation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:887-896.

- Kanitakis J, Narvaez D, Claudy A. Expression of the CD34 antigen distinguishes Kaposi’s sarcoma from pseudo-Kaposi’s sarcoma (acroangiodermatitis). Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:44-46.

- Pires A, Depairon M, Ricci C, et al. Effect of compression therapy on a pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma. Dermatology. 1999;198:439-441.

- Hayek S, Atiyeh B, Zgheib E. Stewart-Bluefarb syndrome: review of the literature and case report of chronic ulcer treatment with heparan sulphate (Cacipliq20®). Int Wound J. 2015;12:169-172.

- Varyani N, Thukral A, Kumar N, et al. Nonhealing ulcer: acroangiodermatitis of Mali. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2011;2011:909383.

- Mehta AA, Pereira RR, Nayak C, et al. Acroangiodermatitis of Mali: a rare vascular phenomenon. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2010;76:553-556.

- Rashkovsky I, Gilead L, Schamroth J, et al. Acro-angiodermatitis: review of the literature and report of a case. Acta Derm Venereol. 1995;75:475-478.

Practice Points

- Acroangiodermatitis (AAD) may mimic Kaposi sarcoma clinically and histopathologically. A human herpesvirus 8 stain is helpful to differentiate these two entities.

- Diagnosis of AAD should prompt investigation of an underlying arteriovenous malformation, as the disease may have systemic consequences such as congestive heart failure.

Photosensitive Atopic Dermatitis Exacerbated by UVB Exposure

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is the most common inflammatory skin condition, affecting approximately 15% to 20% of the global population.1,2 Atopic dermatitis is characterized by a chronic relapsing dermatitis with pruritus, often beginning in infancy or childhood. Atopic dermatitis is caused by a defect in epidermal barrier function, which results in increased transepidermal water loss.1 The criteria for AD include a pruritic skin condition plus 3 or more of the following: history of involvement of the skin creases, history of asthma or hay fever, history of AD in a first-degree relative (in children), 1-year history of generally dry skin, visible flexural eczema, and an age of onset of less than 2 years. Adults with AD frequently present with hand or facial dermatitis.1

UV light therapies including narrowband UVB (NB-UVB), UVA1, and psoralen plus UVA (PUVA) have all been used as effective treatments of AD.3,4 UV light is beneficial for AD patients due to its immunomodulatory effects, thickening of the stratum corneum, and the reduction of Staphylococcus aureus in the skin.2 Most patients with AD improve with light therapy; however, it is estimated that 1% to 3% of patients with AD will experience a paradoxical worsening of their AD after exposure to UV light.2,5 This condition is referred to as photosensitive AD and is characterized by a photodistributed rash in patients who fulfill the criteria of AD. Photosensitive AD has a female predominance and generally affects patients with late-onset disease with development of AD after puberty.2,5 The pathogenesis for the development of photosensitivity in patients with AD who previously tolerated exposure to sunlight is unknown.5 We describe a case of photosensitive AD exacerbated by UVB exposure.

Case Report

On physical examination the patient had thin, well-demarcated, erythematous papules and plaques with scaling, primarily on sun-exposed skin on the forehead (Figure 1A), cheeks (Figure 1B), eyelids, upper lip, neck (Figures 1B and 1C), upper chest (Figure 1C), and dorsal aspect of the hands, with excoriated pink papules on the forearms, shoulders, and back. A punch biopsy of the right neck showed spongiotic dermatitis with a perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate (Figure 2). Further workup was pursued including complete blood cell count, comprehensive metabolic profile, liver function panel, Sjögren syndrome antigen A/Sjögren syndrome antigen B test, antinuclear antibody test, human immunodeficiency virus 1/2 antigen/antibody test, hepatitis panel, and mycobacterium tuberculosis test, which were all within reference range. Photodermatosis was suspected and she underwent phototesting including UVA, NB-UVB, and visible light. Phototesting confirmed she had a UVB photosensitivity with a markedly decreased minimal erythema dose (MED) to NB-UVB. The MED to NB-UVB was positive at 24 hours to all tested sites, the lowest of which was 0.135 J/cm2. Eczematous changes began to develop at day 6 at doses of 0.945 and 1.080 J/cm2. The patient also underwent visible light testing, which was negative. The patient was patch tested for multiple standardized agents as well as personal products, all of which were negative. Subsequent photopatch testing revealed a slightly positive reaction to benzophenone 4, a common ingredient in sunscreens.

The patient was then started on mycophenolate mofetil and prednisone. Repeat MED testing to NB-UVB was performed. Her repeat MED to NB-UVB was determined to be 0.405 J/cm2, and hardening commenced at 3 times per week at 70% of the MED (0.2835 J/cm2). She began to flare and develop an eczematous reaction, thus the dose was decreased to 50% of the MED (0.2025 J/cm2), which she tolerated.

Comment

Classification and Clinical Presentation

The literature on photosensitive AD is scant, and this disease entity is rare. Alternative names include photoaggravated AD, photosensitive eczema, and light-exacerbated eczema.5 Two main studies have been conducted in recent years that were intended to characterize photosensitive AD. ten Berge et al5 conducted a retrospective study of 145 patients with AD that were phototested in 2009. They found that 3% of their total AD patient population had photosensitive AD.5 In 2016, Ellenbogen et al2 performed a similar single-center retrospective analysis of 17 patients with long-standing AD who suddenly developed photosensitivity.

Patients with photosensitive AD typically present with lesions on sun-exposed skin with coexisting eczematous lesions in sites with a predilection for AD.2 In the study conducted by ten Berge et al,5 2 main reaction patterns were observed: erythematous papules with pruritus and an eczematous reaction.

Histopathology

The histopathologic findings of photosensitive AD are nonspecific but are characterized by spongiotic dermatitis with a perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate.2

Diagnosis With Phototesting

Phototesting of patients with AD should be considered if there is a suspicion for photosensitivity based on persistent disease despite use of photoprotection and local treatment.5-7 Patients may not notice a correlation of skin exacerbations with UV exposure, especially if they are only sensitive to UVA, as it is still present on cloudy days and can penetrate glass windows.8 Phototesting evaluates the degree of sensitivity to UV light and the specific wavelength eliciting the cutaneous response. Phototesting consists of determining the MED to UVA and UVB, the minimal phototoxic dose for PUVA, and visible light exposure. Further evaluation may include photoprovocation testing or photopatch testing, as these patients can have coexisting photocontact allergies.

The MED is defined as the minimal dose of UV light needed to induce perceptible erythema in exposed skin.5 It is dependent on the light source and patient’s skin type, and individual units may vary. To determine the MED to UVA or UVB, 2×2-cm skin fields are irradiated with increasing cumulative UVA/UVB. The dose varies by skin type and it is then read at 24 hours. The majority of patients with photosensitive AD are reported to have a normal MED; however, some studies have reported the MED to be decreased.5,7-9 ten Berge et al5 found 7% of their study participants exhibited a lower MED, as seen in our patient.

The minimal phototoxic dose for PUVA is defined as the least exposure dose of UVA 1 hour after ingestion of 0.4 mg/kg of methoxsalen that produces pink erythema with 4 distinct borders at 48, 72, or 96 hours after ingestion.10 Visible light exposure is tested using a slide projector as the light source to an approximately 10×5-cm area of skin for 45 minutes. Any immediate or delayed reaction is abnormal and considered positive.10

Photoprovocation testing has been performed in several studies.2,5 It consists of exposing an 8-cm area of skin to 80 J/cm2 UVA and 10 mJ/cm2 UVB, which is read at 24, 48, or 72 hours. A papular or eczematous reaction is considered positive.2,11

The results of phototesting have varied between studies. ten Berge et al5 phototested 107 patients with AD and photosensitivity and 17% were found to be solely sensitive to UVA whereas 67% were found to be sensitive to UVA and UVB. In contrast, Ellenbogen et al2 only tested 17 patients with AD and photosensitivity and they found that 56% (9/16) were sensitive to UVA alone while only 44% (7/16) were sensitive to UVA and UVB.

Photopatch testing can help to rule out photosensitivity due to a substance in the presence of UV light. In studies of patients with photosensitive AD (N=125), photocontact reactions occurred in 23% and were predominantly associated with sunscreens, skin care products, and fragrances.5,12 Photopatch testing is done by placing duplicate sets of patches on nonlesional skin using the Finn Chamber technique. A published list of allergens, which were agreed upon by the European Society of Contact Dermatitis and the European Society for Photodermatology in 2000 are seen in Table 1.13 The list contains mainly UV filters and drugs. The patients’ own products also should be tested in addition to the published list of allergens, but a maximum of 30 patches should be placed at one time. The patches are removed at either 24 or 48 hours; some researchers have found greater sensitivity with the 48-hour time period, while others have not found a significant difference.10 One set of skin fields then is covered with an impermeable occlusive dressing as a control while the other is irradiated with 5 J/cm2 of a broad-spectrum UVA light source. UVA fluorescent lamps are the light source of choice because of their widespread availability, reproducible broad spectrum, and beam uniformity.10 In the study conducted by ten Berge et al,5 photopatch testing was performed on 125 patients, and 29 patients were found to be positive to one or more substances. Ellenbogen et al2 photopatch tested 5 patients with photosensitive AD and a clinical suspicion of photoallergy; however, all 5 were negative. Our patient underwent traditional patch testing due to clinical suspicion of a coexisting contact allergy, which was negative.

Differential Diagnosis

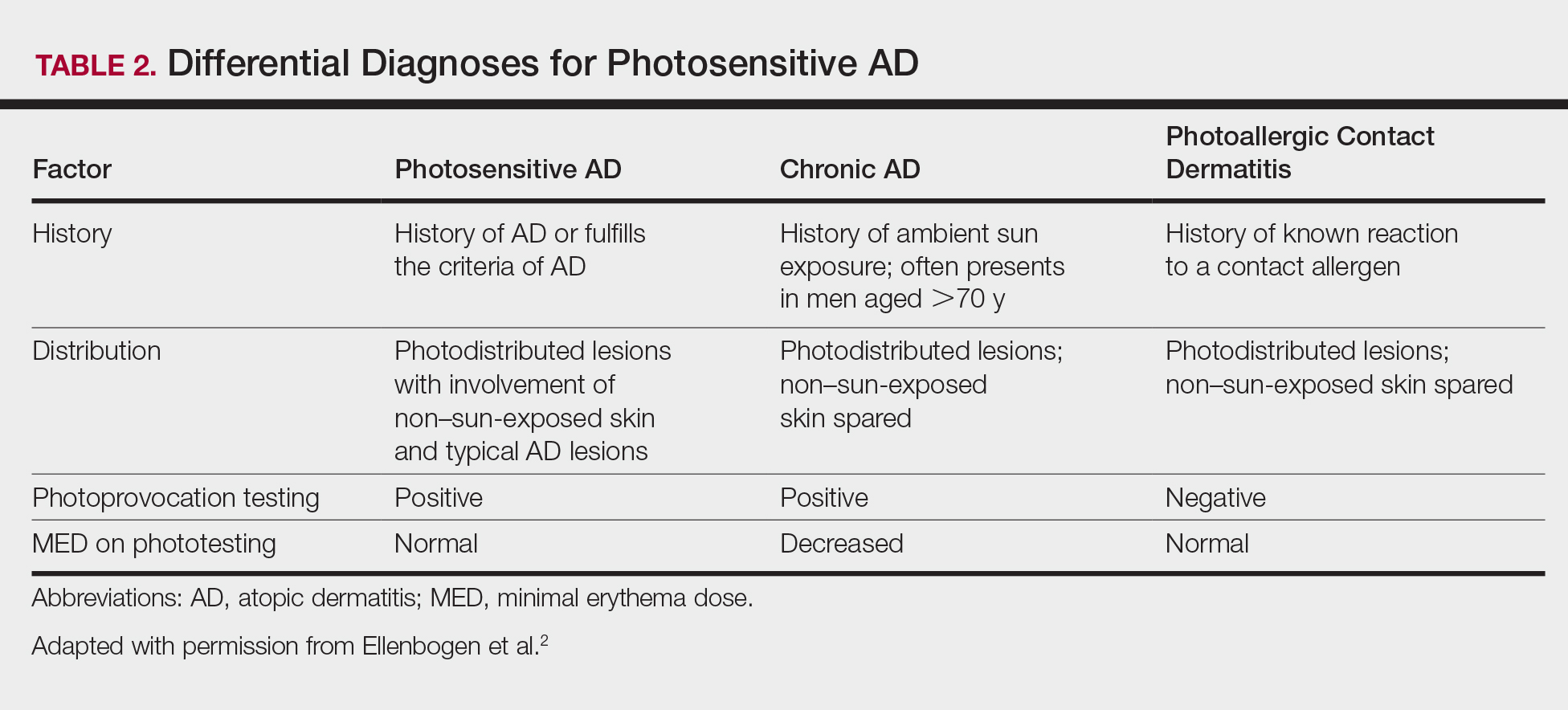

The differential diagnosis for photosensitive AD includes PMLE with coexisting AD, chronic AD, and photoallergic contact dermatitis. Photosensitive AD worsens with increasing exposure to uncontrolled sunlight, in contrast to patients with PMLE who experience UV radiation (UVR) hardening with increasing UV exposure during the summer months, resulting in improvement of skin lesions. Patients with chronic AD generally report a history of chronic ambient sun exposure and exhibit well-demarcated eczematous lesions in a photodistributed pattern with sparing of sun-protected skin.2 In contrast, photosensitive AD involves both sun-exposed and covered areas of the body. Chronic AD will have a positive photoprovocation test with a decreased MED (Table 2). Photoallergic contact dermatitis also will have photodistributed eczematous lesions with relative sparing of non–sun-exposed skin; however, these patients generally have negative photoprovocation testing with a normal MED.2 These patients may or may not have a history of reaction to a known allergen, but they likely will have a positive photopatch test.

Treatment

The treatment of photosensitive AD is based on the severity of the photosensitivity. Treatment for mild disease is limited to sun protection in addition to topical corticosteroids or topical calcineurin inhibitors. For moderate disease and unsatisfactory relief with proper sun protection, UVR hardening is recommended. If severe disease is present, immunosuppression with medications such as corticosteroids, cyclosporine, and mycophenolate mofetil is suggested to prevent flaring of disease during UVR hardening.2,5,8,14

Conclusion

Photosensitive AD is a rare entity characterized by a photodistributed rash and involvement of non–sun-exposed skin. Patients will either have a history of AD or fulfill the criteria of AD. They have positive photoprovocation testing and generally have a normal MED. They may have positive photopatch testing with coexisting photoallergies. Histopathology is nonspecific but shows spongiotic dermatitis with perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate. Diagnosis is essential, as this disease can be life altering and affect quality of life. Effective treatment options are available, and the therapeutic ladder is based on severity of disease.2,5

- Bieber T, Bussmann C. Atopic dermatitis. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo J, Rapini R, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Elsevier; 2012:203-230.

- Ellenbogen E, Wesselmann U, Hofmann SC, et al. Photosensitive atopic dermatitis—a neglected subset: clinical, laboratory, histological and photobiological workup. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:270-275.

- Yule S, Dawe RS, Cameron H, et al. Does narrow-band ultraviolet B phototherapy work in atopic dermatitis through a local or a systemic effect? Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2005;21:333-335.

- Sidbury R, Davis DM, Cohen DE, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis. section 3. Management and treatment with phototherapy and systemic agents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:327-349.

- ten Berge O, van Weelden H, Bruijnzeel-Koomen CA, et al. Throwing a light on photosensitivity in atopic dermatitis: a retrospective study. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2009;10:119-123.

- O’Gorman SM, Murphy GM. Photoaggravated disorders. Dermatol Clin. 2014;32:385-398.

- Crouch RB, Foley PA, Baker CS. Analysis of patients with suspected photosensitivity referred for investigation to an Australian photodermatology clinic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:714-720.

- Russell SC, Dawes RS, Collins P, et al. The photosensitivity dermatitis and actinic reticuloid syndrome (chronic actinic dermatitis) occurring in seven young atopic dermatitis patients. Br J Dermatol. 1998;138:496-501.

- Tajima T, Ibe M, Matsushita T, et al. A variety of skin responses to ultraviolet irradiation in patients with atopic dermatitis. J Dermatol Sci. 1998;17:101-107.

- Faurschou A, Wulf HC. European Dermatology Guideline for the photodermatoses: phototesting. European Dermatology Forum website. http://www.euroderm.org/edf/index.php/edf-guidelines/category/3-guidelines-on-photodermatoses. Accessed August 21, 2017.

- Keong CH, Kurumaji Y, Miyamoto C, et al. Photosensitivity in atopic dermatitis: demonstration of abnormal response to UVB. J Dermatol. 1992;19:342-347.

- Lee PA, Freeman S. Photosensitivity: the 9-year experience at a Sydney contact dermatitis clinic. Australas J Dermatol. 2002;43:289-292.

- Goncalo M, Ferguson J, Bonevalle A, et al. Photopatch testing: recommendations for a European photopatch test baseline series. Contact Dermatitis. 2013;68:239-243.

- Amon U, Mangalo S, Roth A. Clinical relevance of increased UV-sensitivity in patients with atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:AB39.

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is the most common inflammatory skin condition, affecting approximately 15% to 20% of the global population.1,2 Atopic dermatitis is characterized by a chronic relapsing dermatitis with pruritus, often beginning in infancy or childhood. Atopic dermatitis is caused by a defect in epidermal barrier function, which results in increased transepidermal water loss.1 The criteria for AD include a pruritic skin condition plus 3 or more of the following: history of involvement of the skin creases, history of asthma or hay fever, history of AD in a first-degree relative (in children), 1-year history of generally dry skin, visible flexural eczema, and an age of onset of less than 2 years. Adults with AD frequently present with hand or facial dermatitis.1

UV light therapies including narrowband UVB (NB-UVB), UVA1, and psoralen plus UVA (PUVA) have all been used as effective treatments of AD.3,4 UV light is beneficial for AD patients due to its immunomodulatory effects, thickening of the stratum corneum, and the reduction of Staphylococcus aureus in the skin.2 Most patients with AD improve with light therapy; however, it is estimated that 1% to 3% of patients with AD will experience a paradoxical worsening of their AD after exposure to UV light.2,5 This condition is referred to as photosensitive AD and is characterized by a photodistributed rash in patients who fulfill the criteria of AD. Photosensitive AD has a female predominance and generally affects patients with late-onset disease with development of AD after puberty.2,5 The pathogenesis for the development of photosensitivity in patients with AD who previously tolerated exposure to sunlight is unknown.5 We describe a case of photosensitive AD exacerbated by UVB exposure.

Case Report

On physical examination the patient had thin, well-demarcated, erythematous papules and plaques with scaling, primarily on sun-exposed skin on the forehead (Figure 1A), cheeks (Figure 1B), eyelids, upper lip, neck (Figures 1B and 1C), upper chest (Figure 1C), and dorsal aspect of the hands, with excoriated pink papules on the forearms, shoulders, and back. A punch biopsy of the right neck showed spongiotic dermatitis with a perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate (Figure 2). Further workup was pursued including complete blood cell count, comprehensive metabolic profile, liver function panel, Sjögren syndrome antigen A/Sjögren syndrome antigen B test, antinuclear antibody test, human immunodeficiency virus 1/2 antigen/antibody test, hepatitis panel, and mycobacterium tuberculosis test, which were all within reference range. Photodermatosis was suspected and she underwent phototesting including UVA, NB-UVB, and visible light. Phototesting confirmed she had a UVB photosensitivity with a markedly decreased minimal erythema dose (MED) to NB-UVB. The MED to NB-UVB was positive at 24 hours to all tested sites, the lowest of which was 0.135 J/cm2. Eczematous changes began to develop at day 6 at doses of 0.945 and 1.080 J/cm2. The patient also underwent visible light testing, which was negative. The patient was patch tested for multiple standardized agents as well as personal products, all of which were negative. Subsequent photopatch testing revealed a slightly positive reaction to benzophenone 4, a common ingredient in sunscreens.

The patient was then started on mycophenolate mofetil and prednisone. Repeat MED testing to NB-UVB was performed. Her repeat MED to NB-UVB was determined to be 0.405 J/cm2, and hardening commenced at 3 times per week at 70% of the MED (0.2835 J/cm2). She began to flare and develop an eczematous reaction, thus the dose was decreased to 50% of the MED (0.2025 J/cm2), which she tolerated.

Comment

Classification and Clinical Presentation

The literature on photosensitive AD is scant, and this disease entity is rare. Alternative names include photoaggravated AD, photosensitive eczema, and light-exacerbated eczema.5 Two main studies have been conducted in recent years that were intended to characterize photosensitive AD. ten Berge et al5 conducted a retrospective study of 145 patients with AD that were phototested in 2009. They found that 3% of their total AD patient population had photosensitive AD.5 In 2016, Ellenbogen et al2 performed a similar single-center retrospective analysis of 17 patients with long-standing AD who suddenly developed photosensitivity.

Patients with photosensitive AD typically present with lesions on sun-exposed skin with coexisting eczematous lesions in sites with a predilection for AD.2 In the study conducted by ten Berge et al,5 2 main reaction patterns were observed: erythematous papules with pruritus and an eczematous reaction.

Histopathology

The histopathologic findings of photosensitive AD are nonspecific but are characterized by spongiotic dermatitis with a perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate.2

Diagnosis With Phototesting

Phototesting of patients with AD should be considered if there is a suspicion for photosensitivity based on persistent disease despite use of photoprotection and local treatment.5-7 Patients may not notice a correlation of skin exacerbations with UV exposure, especially if they are only sensitive to UVA, as it is still present on cloudy days and can penetrate glass windows.8 Phototesting evaluates the degree of sensitivity to UV light and the specific wavelength eliciting the cutaneous response. Phototesting consists of determining the MED to UVA and UVB, the minimal phototoxic dose for PUVA, and visible light exposure. Further evaluation may include photoprovocation testing or photopatch testing, as these patients can have coexisting photocontact allergies.

The MED is defined as the minimal dose of UV light needed to induce perceptible erythema in exposed skin.5 It is dependent on the light source and patient’s skin type, and individual units may vary. To determine the MED to UVA or UVB, 2×2-cm skin fields are irradiated with increasing cumulative UVA/UVB. The dose varies by skin type and it is then read at 24 hours. The majority of patients with photosensitive AD are reported to have a normal MED; however, some studies have reported the MED to be decreased.5,7-9 ten Berge et al5 found 7% of their study participants exhibited a lower MED, as seen in our patient.

The minimal phototoxic dose for PUVA is defined as the least exposure dose of UVA 1 hour after ingestion of 0.4 mg/kg of methoxsalen that produces pink erythema with 4 distinct borders at 48, 72, or 96 hours after ingestion.10 Visible light exposure is tested using a slide projector as the light source to an approximately 10×5-cm area of skin for 45 minutes. Any immediate or delayed reaction is abnormal and considered positive.10

Photoprovocation testing has been performed in several studies.2,5 It consists of exposing an 8-cm area of skin to 80 J/cm2 UVA and 10 mJ/cm2 UVB, which is read at 24, 48, or 72 hours. A papular or eczematous reaction is considered positive.2,11

The results of phototesting have varied between studies. ten Berge et al5 phototested 107 patients with AD and photosensitivity and 17% were found to be solely sensitive to UVA whereas 67% were found to be sensitive to UVA and UVB. In contrast, Ellenbogen et al2 only tested 17 patients with AD and photosensitivity and they found that 56% (9/16) were sensitive to UVA alone while only 44% (7/16) were sensitive to UVA and UVB.

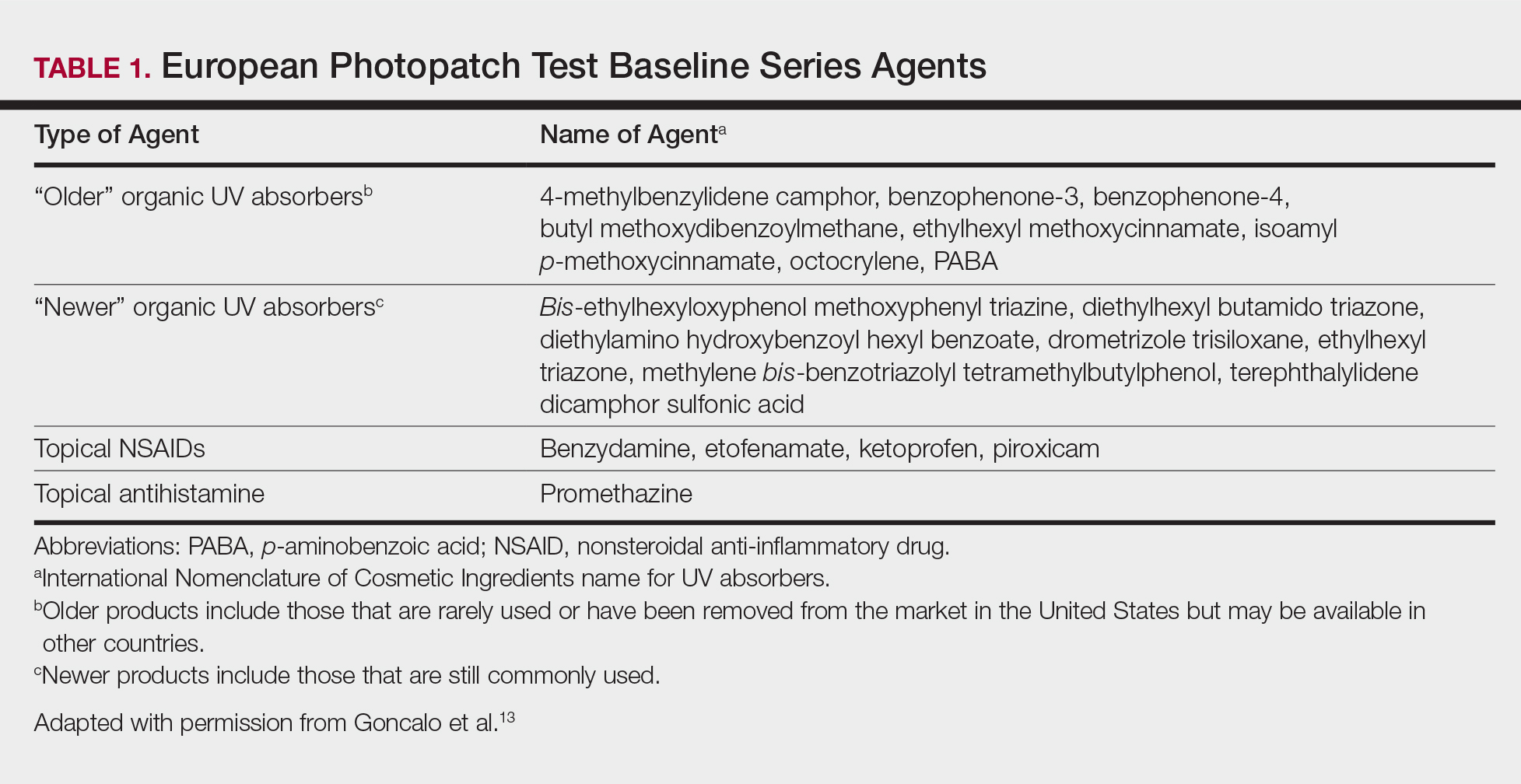

Photopatch testing can help to rule out photosensitivity due to a substance in the presence of UV light. In studies of patients with photosensitive AD (N=125), photocontact reactions occurred in 23% and were predominantly associated with sunscreens, skin care products, and fragrances.5,12 Photopatch testing is done by placing duplicate sets of patches on nonlesional skin using the Finn Chamber technique. A published list of allergens, which were agreed upon by the European Society of Contact Dermatitis and the European Society for Photodermatology in 2000 are seen in Table 1.13 The list contains mainly UV filters and drugs. The patients’ own products also should be tested in addition to the published list of allergens, but a maximum of 30 patches should be placed at one time. The patches are removed at either 24 or 48 hours; some researchers have found greater sensitivity with the 48-hour time period, while others have not found a significant difference.10 One set of skin fields then is covered with an impermeable occlusive dressing as a control while the other is irradiated with 5 J/cm2 of a broad-spectrum UVA light source. UVA fluorescent lamps are the light source of choice because of their widespread availability, reproducible broad spectrum, and beam uniformity.10 In the study conducted by ten Berge et al,5 photopatch testing was performed on 125 patients, and 29 patients were found to be positive to one or more substances. Ellenbogen et al2 photopatch tested 5 patients with photosensitive AD and a clinical suspicion of photoallergy; however, all 5 were negative. Our patient underwent traditional patch testing due to clinical suspicion of a coexisting contact allergy, which was negative.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for photosensitive AD includes PMLE with coexisting AD, chronic AD, and photoallergic contact dermatitis. Photosensitive AD worsens with increasing exposure to uncontrolled sunlight, in contrast to patients with PMLE who experience UV radiation (UVR) hardening with increasing UV exposure during the summer months, resulting in improvement of skin lesions. Patients with chronic AD generally report a history of chronic ambient sun exposure and exhibit well-demarcated eczematous lesions in a photodistributed pattern with sparing of sun-protected skin.2 In contrast, photosensitive AD involves both sun-exposed and covered areas of the body. Chronic AD will have a positive photoprovocation test with a decreased MED (Table 2). Photoallergic contact dermatitis also will have photodistributed eczematous lesions with relative sparing of non–sun-exposed skin; however, these patients generally have negative photoprovocation testing with a normal MED.2 These patients may or may not have a history of reaction to a known allergen, but they likely will have a positive photopatch test.

Treatment

The treatment of photosensitive AD is based on the severity of the photosensitivity. Treatment for mild disease is limited to sun protection in addition to topical corticosteroids or topical calcineurin inhibitors. For moderate disease and unsatisfactory relief with proper sun protection, UVR hardening is recommended. If severe disease is present, immunosuppression with medications such as corticosteroids, cyclosporine, and mycophenolate mofetil is suggested to prevent flaring of disease during UVR hardening.2,5,8,14

Conclusion

Photosensitive AD is a rare entity characterized by a photodistributed rash and involvement of non–sun-exposed skin. Patients will either have a history of AD or fulfill the criteria of AD. They have positive photoprovocation testing and generally have a normal MED. They may have positive photopatch testing with coexisting photoallergies. Histopathology is nonspecific but shows spongiotic dermatitis with perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate. Diagnosis is essential, as this disease can be life altering and affect quality of life. Effective treatment options are available, and the therapeutic ladder is based on severity of disease.2,5

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is the most common inflammatory skin condition, affecting approximately 15% to 20% of the global population.1,2 Atopic dermatitis is characterized by a chronic relapsing dermatitis with pruritus, often beginning in infancy or childhood. Atopic dermatitis is caused by a defect in epidermal barrier function, which results in increased transepidermal water loss.1 The criteria for AD include a pruritic skin condition plus 3 or more of the following: history of involvement of the skin creases, history of asthma or hay fever, history of AD in a first-degree relative (in children), 1-year history of generally dry skin, visible flexural eczema, and an age of onset of less than 2 years. Adults with AD frequently present with hand or facial dermatitis.1

UV light therapies including narrowband UVB (NB-UVB), UVA1, and psoralen plus UVA (PUVA) have all been used as effective treatments of AD.3,4 UV light is beneficial for AD patients due to its immunomodulatory effects, thickening of the stratum corneum, and the reduction of Staphylococcus aureus in the skin.2 Most patients with AD improve with light therapy; however, it is estimated that 1% to 3% of patients with AD will experience a paradoxical worsening of their AD after exposure to UV light.2,5 This condition is referred to as photosensitive AD and is characterized by a photodistributed rash in patients who fulfill the criteria of AD. Photosensitive AD has a female predominance and generally affects patients with late-onset disease with development of AD after puberty.2,5 The pathogenesis for the development of photosensitivity in patients with AD who previously tolerated exposure to sunlight is unknown.5 We describe a case of photosensitive AD exacerbated by UVB exposure.

Case Report

On physical examination the patient had thin, well-demarcated, erythematous papules and plaques with scaling, primarily on sun-exposed skin on the forehead (Figure 1A), cheeks (Figure 1B), eyelids, upper lip, neck (Figures 1B and 1C), upper chest (Figure 1C), and dorsal aspect of the hands, with excoriated pink papules on the forearms, shoulders, and back. A punch biopsy of the right neck showed spongiotic dermatitis with a perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate (Figure 2). Further workup was pursued including complete blood cell count, comprehensive metabolic profile, liver function panel, Sjögren syndrome antigen A/Sjögren syndrome antigen B test, antinuclear antibody test, human immunodeficiency virus 1/2 antigen/antibody test, hepatitis panel, and mycobacterium tuberculosis test, which were all within reference range. Photodermatosis was suspected and she underwent phototesting including UVA, NB-UVB, and visible light. Phototesting confirmed she had a UVB photosensitivity with a markedly decreased minimal erythema dose (MED) to NB-UVB. The MED to NB-UVB was positive at 24 hours to all tested sites, the lowest of which was 0.135 J/cm2. Eczematous changes began to develop at day 6 at doses of 0.945 and 1.080 J/cm2. The patient also underwent visible light testing, which was negative. The patient was patch tested for multiple standardized agents as well as personal products, all of which were negative. Subsequent photopatch testing revealed a slightly positive reaction to benzophenone 4, a common ingredient in sunscreens.

The patient was then started on mycophenolate mofetil and prednisone. Repeat MED testing to NB-UVB was performed. Her repeat MED to NB-UVB was determined to be 0.405 J/cm2, and hardening commenced at 3 times per week at 70% of the MED (0.2835 J/cm2). She began to flare and develop an eczematous reaction, thus the dose was decreased to 50% of the MED (0.2025 J/cm2), which she tolerated.

Comment

Classification and Clinical Presentation

The literature on photosensitive AD is scant, and this disease entity is rare. Alternative names include photoaggravated AD, photosensitive eczema, and light-exacerbated eczema.5 Two main studies have been conducted in recent years that were intended to characterize photosensitive AD. ten Berge et al5 conducted a retrospective study of 145 patients with AD that were phototested in 2009. They found that 3% of their total AD patient population had photosensitive AD.5 In 2016, Ellenbogen et al2 performed a similar single-center retrospective analysis of 17 patients with long-standing AD who suddenly developed photosensitivity.

Patients with photosensitive AD typically present with lesions on sun-exposed skin with coexisting eczematous lesions in sites with a predilection for AD.2 In the study conducted by ten Berge et al,5 2 main reaction patterns were observed: erythematous papules with pruritus and an eczematous reaction.

Histopathology

The histopathologic findings of photosensitive AD are nonspecific but are characterized by spongiotic dermatitis with a perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate.2

Diagnosis With Phototesting

Phototesting of patients with AD should be considered if there is a suspicion for photosensitivity based on persistent disease despite use of photoprotection and local treatment.5-7 Patients may not notice a correlation of skin exacerbations with UV exposure, especially if they are only sensitive to UVA, as it is still present on cloudy days and can penetrate glass windows.8 Phototesting evaluates the degree of sensitivity to UV light and the specific wavelength eliciting the cutaneous response. Phototesting consists of determining the MED to UVA and UVB, the minimal phototoxic dose for PUVA, and visible light exposure. Further evaluation may include photoprovocation testing or photopatch testing, as these patients can have coexisting photocontact allergies.

The MED is defined as the minimal dose of UV light needed to induce perceptible erythema in exposed skin.5 It is dependent on the light source and patient’s skin type, and individual units may vary. To determine the MED to UVA or UVB, 2×2-cm skin fields are irradiated with increasing cumulative UVA/UVB. The dose varies by skin type and it is then read at 24 hours. The majority of patients with photosensitive AD are reported to have a normal MED; however, some studies have reported the MED to be decreased.5,7-9 ten Berge et al5 found 7% of their study participants exhibited a lower MED, as seen in our patient.

The minimal phototoxic dose for PUVA is defined as the least exposure dose of UVA 1 hour after ingestion of 0.4 mg/kg of methoxsalen that produces pink erythema with 4 distinct borders at 48, 72, or 96 hours after ingestion.10 Visible light exposure is tested using a slide projector as the light source to an approximately 10×5-cm area of skin for 45 minutes. Any immediate or delayed reaction is abnormal and considered positive.10

Photoprovocation testing has been performed in several studies.2,5 It consists of exposing an 8-cm area of skin to 80 J/cm2 UVA and 10 mJ/cm2 UVB, which is read at 24, 48, or 72 hours. A papular or eczematous reaction is considered positive.2,11

The results of phototesting have varied between studies. ten Berge et al5 phototested 107 patients with AD and photosensitivity and 17% were found to be solely sensitive to UVA whereas 67% were found to be sensitive to UVA and UVB. In contrast, Ellenbogen et al2 only tested 17 patients with AD and photosensitivity and they found that 56% (9/16) were sensitive to UVA alone while only 44% (7/16) were sensitive to UVA and UVB.

Photopatch testing can help to rule out photosensitivity due to a substance in the presence of UV light. In studies of patients with photosensitive AD (N=125), photocontact reactions occurred in 23% and were predominantly associated with sunscreens, skin care products, and fragrances.5,12 Photopatch testing is done by placing duplicate sets of patches on nonlesional skin using the Finn Chamber technique. A published list of allergens, which were agreed upon by the European Society of Contact Dermatitis and the European Society for Photodermatology in 2000 are seen in Table 1.13 The list contains mainly UV filters and drugs. The patients’ own products also should be tested in addition to the published list of allergens, but a maximum of 30 patches should be placed at one time. The patches are removed at either 24 or 48 hours; some researchers have found greater sensitivity with the 48-hour time period, while others have not found a significant difference.10 One set of skin fields then is covered with an impermeable occlusive dressing as a control while the other is irradiated with 5 J/cm2 of a broad-spectrum UVA light source. UVA fluorescent lamps are the light source of choice because of their widespread availability, reproducible broad spectrum, and beam uniformity.10 In the study conducted by ten Berge et al,5 photopatch testing was performed on 125 patients, and 29 patients were found to be positive to one or more substances. Ellenbogen et al2 photopatch tested 5 patients with photosensitive AD and a clinical suspicion of photoallergy; however, all 5 were negative. Our patient underwent traditional patch testing due to clinical suspicion of a coexisting contact allergy, which was negative.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for photosensitive AD includes PMLE with coexisting AD, chronic AD, and photoallergic contact dermatitis. Photosensitive AD worsens with increasing exposure to uncontrolled sunlight, in contrast to patients with PMLE who experience UV radiation (UVR) hardening with increasing UV exposure during the summer months, resulting in improvement of skin lesions. Patients with chronic AD generally report a history of chronic ambient sun exposure and exhibit well-demarcated eczematous lesions in a photodistributed pattern with sparing of sun-protected skin.2 In contrast, photosensitive AD involves both sun-exposed and covered areas of the body. Chronic AD will have a positive photoprovocation test with a decreased MED (Table 2). Photoallergic contact dermatitis also will have photodistributed eczematous lesions with relative sparing of non–sun-exposed skin; however, these patients generally have negative photoprovocation testing with a normal MED.2 These patients may or may not have a history of reaction to a known allergen, but they likely will have a positive photopatch test.

Treatment

The treatment of photosensitive AD is based on the severity of the photosensitivity. Treatment for mild disease is limited to sun protection in addition to topical corticosteroids or topical calcineurin inhibitors. For moderate disease and unsatisfactory relief with proper sun protection, UVR hardening is recommended. If severe disease is present, immunosuppression with medications such as corticosteroids, cyclosporine, and mycophenolate mofetil is suggested to prevent flaring of disease during UVR hardening.2,5,8,14

Conclusion

Photosensitive AD is a rare entity characterized by a photodistributed rash and involvement of non–sun-exposed skin. Patients will either have a history of AD or fulfill the criteria of AD. They have positive photoprovocation testing and generally have a normal MED. They may have positive photopatch testing with coexisting photoallergies. Histopathology is nonspecific but shows spongiotic dermatitis with perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate. Diagnosis is essential, as this disease can be life altering and affect quality of life. Effective treatment options are available, and the therapeutic ladder is based on severity of disease.2,5

- Bieber T, Bussmann C. Atopic dermatitis. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo J, Rapini R, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Elsevier; 2012:203-230.

- Ellenbogen E, Wesselmann U, Hofmann SC, et al. Photosensitive atopic dermatitis—a neglected subset: clinical, laboratory, histological and photobiological workup. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:270-275.

- Yule S, Dawe RS, Cameron H, et al. Does narrow-band ultraviolet B phototherapy work in atopic dermatitis through a local or a systemic effect? Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2005;21:333-335.

- Sidbury R, Davis DM, Cohen DE, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis. section 3. Management and treatment with phototherapy and systemic agents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:327-349.

- ten Berge O, van Weelden H, Bruijnzeel-Koomen CA, et al. Throwing a light on photosensitivity in atopic dermatitis: a retrospective study. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2009;10:119-123.

- O’Gorman SM, Murphy GM. Photoaggravated disorders. Dermatol Clin. 2014;32:385-398.

- Crouch RB, Foley PA, Baker CS. Analysis of patients with suspected photosensitivity referred for investigation to an Australian photodermatology clinic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:714-720.

- Russell SC, Dawes RS, Collins P, et al. The photosensitivity dermatitis and actinic reticuloid syndrome (chronic actinic dermatitis) occurring in seven young atopic dermatitis patients. Br J Dermatol. 1998;138:496-501.

- Tajima T, Ibe M, Matsushita T, et al. A variety of skin responses to ultraviolet irradiation in patients with atopic dermatitis. J Dermatol Sci. 1998;17:101-107.

- Faurschou A, Wulf HC. European Dermatology Guideline for the photodermatoses: phototesting. European Dermatology Forum website. http://www.euroderm.org/edf/index.php/edf-guidelines/category/3-guidelines-on-photodermatoses. Accessed August 21, 2017.

- Keong CH, Kurumaji Y, Miyamoto C, et al. Photosensitivity in atopic dermatitis: demonstration of abnormal response to UVB. J Dermatol. 1992;19:342-347.

- Lee PA, Freeman S. Photosensitivity: the 9-year experience at a Sydney contact dermatitis clinic. Australas J Dermatol. 2002;43:289-292.

- Goncalo M, Ferguson J, Bonevalle A, et al. Photopatch testing: recommendations for a European photopatch test baseline series. Contact Dermatitis. 2013;68:239-243.

- Amon U, Mangalo S, Roth A. Clinical relevance of increased UV-sensitivity in patients with atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:AB39.

- Bieber T, Bussmann C. Atopic dermatitis. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo J, Rapini R, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Elsevier; 2012:203-230.

- Ellenbogen E, Wesselmann U, Hofmann SC, et al. Photosensitive atopic dermatitis—a neglected subset: clinical, laboratory, histological and photobiological workup. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:270-275.

- Yule S, Dawe RS, Cameron H, et al. Does narrow-band ultraviolet B phototherapy work in atopic dermatitis through a local or a systemic effect? Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2005;21:333-335.

- Sidbury R, Davis DM, Cohen DE, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis. section 3. Management and treatment with phototherapy and systemic agents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:327-349.

- ten Berge O, van Weelden H, Bruijnzeel-Koomen CA, et al. Throwing a light on photosensitivity in atopic dermatitis: a retrospective study. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2009;10:119-123.

- O’Gorman SM, Murphy GM. Photoaggravated disorders. Dermatol Clin. 2014;32:385-398.

- Crouch RB, Foley PA, Baker CS. Analysis of patients with suspected photosensitivity referred for investigation to an Australian photodermatology clinic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:714-720.

- Russell SC, Dawes RS, Collins P, et al. The photosensitivity dermatitis and actinic reticuloid syndrome (chronic actinic dermatitis) occurring in seven young atopic dermatitis patients. Br J Dermatol. 1998;138:496-501.