User login

Factors Affecting Perceptions of Open, Mini-Open, and Arthroscopic Rotator Cuff Repair Techniques Among Medical Professionals

Rotator cuff tears are a common condition affecting the shoulder joint. Initial open repair techniques were associated with several complications, including severe early postoperative pain, deltoid detachment and/or weakness, risk for infection, and arthrofibrosis.1-3 In addition, open procedures cannot address other possible diagnoses, such as labral tears and loose bodies. These disadvantages promoted the development of an arthroscopically assisted mini-open technique.4 Superior long-term results, with more than 90% of patients achieving good to excellent results,5-13 established the mini-open rotator cuff repair (RCR) as the gold standard.3,6,10,12,14-16

Recently, as instrumentation for arthroscopy has improved, enthusiasm for all-arthroscopic techniques (hereafter referred to as arthroscopic repair) has grown. The appeal of arthroscopic repair includes potentially less initial pain, ability to treat intra-articular lesions concurrently, smaller skin incisions with better cosmesis, less soft-tissue dissection, and low risk for deltoid detachment.3,17 The potential advantages of arthroscopic repair can lead to perceptions of quicker healing and shorter recovery, which are not supported by the literature. However, arthroscopic repair is technically more challenging, time-consuming, and expensive than open or mini-open repairs,18,19 and though some investigators have reported a trend toward fewer complications,3 the long-term outcome of arthroscopic RCRs has not been shown to be better than that of other techniques.

Given that no differences have been shown between the emerging arthroscopic repair technique and mini-open repair with respect to range of motion or clinical scores in the short term,3 it is unclear what perceptions influence choice of technique for one’s own personal RCR.

We conducted a study to determine which RCR technique medical professionals (orthopedic attendings and residents, anesthesiologists, internal medicine attendings, main operating room nurses, and physical therapists) preferred for their own surgery and to analyze perceptions shaping those opinions. Orthopedic surgeons have the best concept of rotator cuff surgery, but anesthesiologists and nurses have a “front row seat” and opinions on types of rotator cuff surgery. Physical therapists, who treat patients with rotator cuff tears, also have a working knowledge of rotator cuff surgery. Finally, internists represent a rotator cuff injury referral service and may have patients who have undergone rotator cuff surgery. We hypothesized that most medical professionals, irrespective of specialty or career length, would prefer arthroscopic RCR because of its perceived superior outcome and fast recovery.

Materials and Methods

This cross-sectional, descriptive, survey-based study was approved by our institutional review board (IRB) and offered via 3 emails between April 2011 and June 2011 to attendings (orthopedists, internists, anesthesiologists), residents, and allied health professionals (AHPs; operating room nurses, physical therapists) involved in orthopedic care at our institution. Each email contained a hyperlink to the online survey (Appendix), which took about 10 minutes to complete and explored respondent demographics, exposure to the different techniques, and opinions regarding different aspects of RCR surgery and recovery.

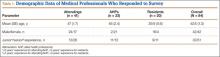

There were 84 respondents. The sexes were equally represented, and age ranged from 25 to 78 years (Table 1). Of the respondents, 41 (49%) were attendings, 20 (24%) were residents, and 23 (27%) were AHPs. Of the attendings, 13 (32%) were orthopedic surgeons, 26 (63%) were primary care physicians, and 2 (5%) did not specify their specialty. Four orthopedic surgeons had fellowship training in sports medicine or shoulder and elbow surgery. The attendings were overall more experienced in their profession than the other groups were, with 68% reporting more than 5 years of experience.

Descriptive statistics, including means and standard errors, were calculated. Fisher exact test was used to compare preferences of RCR type according to type of training and years of experience. Significance was set at P ≤ .05.

Results

Overall Responses (Table 2)

Of the 84 respondents, almost half (46%) preferred deferring their choice of RCR to their surgeon. Most of the other respondents preferred the arthroscopic technique (26%) or the mini-open repair (23%). There was no association between technique preference and medical professional type. Most respondents (63%) had never assisted in or performed rotator cuff surgery.

Seventy-four percent of all respondents indicated they thought arthroscopic, mini-open, and open RCRs are safe, and about half thought these procedures are fast. About half expressed no opinion about the cost-effectiveness of arthroscopic, mini-open, or open RCRs (54%, 52%, and 48%, respectively), and slightly more than half expressed no opinion about whether arthroscopic, mini-open, or open RCR provide the best outcome (58%, 60%, and 62%, respectively). Significantly (P < .05) more respondents thought arthroscopic and mini-open repairs, rather than open repairs, promote quick healing (64% and 45%, respectively, vs 15%), good cosmetic results (81% and 51%, respectively, vs 10%), and patient satisfaction (50% and 48%, respectively, vs 30%). However, a significant (P < .05) number also thought arthroscopic and mini-open repairs are harder to learn/more challenging to perform than open repairs (52% and 38%, respectively, vs 17%).

Of all factors considered, safety of arthroscopic repair garnered the highest consensus: 82%. Respondents were least opinionated about the outcome of the open repair technique, with more than 62% expressing no opinion about the outcome. The responses to the questions on the learning curves for the 3 techniques varied the most.

Responses by Group (Table 2)

Attendings. Of the 41 attendings, 24 (59%) responded they would defer to their surgeon’s technique preference for RCR. Of the other 17 who expressed a preference, most indicated arthroscopic or mini-open repair (17% each). There was a difference (P < .05) between years of experience and RCR preference: of the 13 attendings with less than 5 years of experience, arthroscopic repair was preferred by 31%; in contrast, of the 28 attendings with more than 5 years of experience, only 11% preferred arthroscopic repair.

Of the 11 attendings who performed rotator cuff surgery, 55% used the open technique, but most (8) preferred to have their own rotator cuff fixed arthroscopically or according to their surgeon’s preference. Only 1 surgeon preferred open repair for his own rotator cuff. Of the 4 surgeons who performed arthroscopic RCRs, 3 had less than 5 years of experience. Conversely, all 7 surgeons who performed mini-open or open repairs had more than 5 years of experience.

Of the 30 attendings who did not perform rotator cuff surgery, most (20) responded they would defer to their surgeon’s technique preference for RCR.

The attendings’ opinions on factors affecting rotator cuff surgery were similar to those of the other respondents with respect to safety, cost-effectiveness, recovery, cosmesis, patient satisfaction, outcome, and technical difficulty. Unlike the others, however, attendings considered all 3 repair techniques fast.

Residents. Of the 20 residents, 7 preferred arthroscopic, 5 preferred mini-open, and 1 preferred open repair; the other 7 responded they would defer to their surgeon’s preference. Residents’ opinions on each factor were more polarized and consistent across categories than those of the other groups. Residents overwhelmingly thought all 3 techniques (arthroscopic, mini-open, open) are safe (19, 19, and 18, respectively) and cost-effective (12, 14, and 14, respectively). Although most residents considered the open and mini-open repair techniques fast (19 and 15, respectively), only 8 considered arthroscopic RCR fast, and 4 considered it slow. Residents’ opinions about the technique that produces the best outcome were mixed. As with the other respondents, residents thought arthroscopic RCRs heal fast and produce great cosmetic results, but are challenging to perform and have a steep learning curve. Unlike the other respondents, most residents (12) considered open RCR easy to learn (P = .006), with a learning curve of fewer than 20 procedures.

AHPs. No AHP expressed a preference for open RCR. This group was evenly divided among 3 choices: deferring to their surgeon’s preference, arthroscopic repair, and mini-open repair. The 23 AHPs thought arthroscopic, mini-open, and open repairs are safe (17, 15, and 12, respectively), but most indicated they were “equivocal” about which techniques are cost-effective, challenging to perform, and produce the best outcomes. A significantly (P = .014) larger number of AHPs (7) considered open rotator cuff surgery slow compared with arthroscopic (0) and mini-open (2) repair techniques. As with the overall cohort, AHPs reported arthroscopic and mini-open repairs promote quick healing and good cosmetic results, but are challenging to perform.

Discussion

As our population ages and continues to remain active, the demand for RCR has accelerated. National data show that 272,148 ambulatory RCRs and 20,433 inpatient RCRs were performed in 2006—an overall 141% increase in RCR since 1996.20 In 1996, 41 per 100,000 population underwent RCR.20 By 2006, this number ballooned to 98 per 100,000 population.20 There are 3 predominant techniques for repairing the rotator cuff: open, mini-open, and arthroscopic. As RCR use increases, we should consider the factors that medical professionals consider important when choosing a method for their own RCR.

Of the 84 medical professionals in our cohort, 39 (46%) indicated they would defer to their surgeon’s technique preference for RCR. Of the other 45, about equal numbers preferred arthroscopic and mini-open RCRs; only 2 preferred open RCRs. This finding suggests that the individual opinions of surgeons who perform RCRs have a substantial influence on a large proportion of medical professionals’ ultimate choice of RCR method. Interestingly, of the attendings who performed open RCR, only 1 expressed a preference for the open technique for his own RCR. This finding might suggest a shift in opinion and an emerging perception among surgeons performing RCR about the value of this technique.

Several factors may account for these evolving beliefs. We hypothesized that a biased favorable view of arthroscopic repair outcome might influence opinions. However, our results did not support the hypothesis. Medical professionals in our cohort were equivocal about the best RCR technique. No consensus was evident among attendings, residents, or AHPs. This lack of clinical agreement about rotator cuff surgery has been observed elsewhere—for example, among members of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS)21 and the European Society of Sports Traumatology, Knee Surgery, and Arthroscopy.22 Despite theoretical advantages of arthroscopic repair, there has been no documented significant difference in patient outcomes when compared with other techniques.23 To our knowledge, there have been only a few clinical studies comparing the different RCR techniques. A meta-analysis of 5 clinical studies comparing arthroscopic and mini-open RCR techniques showed no difference in clinical outcomes or complication rates.8 The 2012 AAOS clinical practice guidelines for RCR reflect these observations.24 That consortium of leading shoulder surgeons could not recommend a modality of surgical rotator cuff tear repair given the lack of conclusive evidence.24

At our institution, arthroscopic, mini-open, and open RCRs were performed by 36%, 9%, and 55% of our surgeons, respectively. A survey of AAOS surgeons showed that, of those who perform RCRs, 14.5%, 46.2%, and 36.6% used arthroscopic, mini-open, and open techniques, respectively.21 The greater use of open repairs at our institution might reflect the seniority of our faculty. Dunn and colleagues21 found that surgeons who preferred open RCR had been in practice longer than those who preferred the arthroscopic or mini-open technique. Of our 4 faculty who performed arthroscopic repairs, 3 were less than 5 years from completing their training. In contrast, all faculty who performed mini-open or open repairs were more than 5 years from completing their training. Furthermore, mean age of the surgeons who performed arthroscopic repair was 39.8 years (range, 32-51 years), and these surgeons were significantly younger than those who performed mini-open or open repair (mean age, 56.3 years; range, 41-78 years). Younger surgeon age has been associated with higher rates of arthroscopic repair.25

Attendings unaccustomed to arthroscopy may find it more challenging than the younger generation of surgeons, who are exposed to it early in training. Dunn and colleagues21 noted that the likelihood of performing an arthroscopic repair was influenced by the surgeon’s experience level. Fellowship-trained shoulder and sports medicine surgeons are also more likely to perform arthroscopic repairs than those with training limited to orthopedic residency.25 Arthroscopic RCR demands a high level of technical skill that many acquire in fellowship training.26 Mauro and colleagues26 found that surgeons trained in a sports medicine fellowship performed 82.6% of subacromial decompression and/or RCR procedures arthroscopically, compared with 54.5% to 70.1% for surgeons trained in other fellowships. In our cohort, with the exception of 1 surgeon, all fellowship-trained shoulder and sports medicine surgeons performed arthroscopic RCRs.

Although no conclusive evidence in the literature supports arthroscopic over the other repair types, the demand for arthroscopic RCR has rapidly increased relative to that for the others. Between 1996 and 2006, use of arthroscopic RCR increased 600%, from 8 to 58 per 100,000 population.20 In that same period, use of open RCR increased by only 34%.20 Similarly, Mauro and colleagues26 found that the proportion of subacromial decompression and RCRs performed arthroscopically rose from 58.3% in 2004 to 83.7% in 2009. Using the 2006 New York State Ambulatory Surgery Database, Churchill and Ghorai27 found that 74.5% of RCRs with acromioplasty were performed arthroscopically.

Respondent-indicated factors that may have contributed to the more favorable opinion of arthroscopic and mini-open repair include quick healing, good cosmetic results, and better perceived patient satisfaction. The literature supports these perceptions. Baker and Liu14 found shorter hospital stays and quicker return to activity with arthroscopic repair compared with open repair. Vitale and colleagues25 also noted that, compared with open or mini-open repair techniques, arthroscopic repair resulted in shorter hospitalization and quicker overall recovery.

If these selected health care professionals with some inside information on rotator cuff surgery have biases that affect their selection of rotator cuff procedures, we should acknowledge that nonmedical personnel, in particular our patients, also have biases. The knowledge base of patients may be further influenced by friends or family members who have had rotator cuff surgery, by lay publications, and by the Internet. Satisfaction with any surgical procedure depends not only on the success of the surgery and the rehabilitation but also on patient and provider expectations. Such expectations are influenced, in part, by biases.

Our medical professionals had similar opinions on safety, recovery, cosmesis, and overall outcome of the RCR techniques, but different opinions on procedure durations and associated training requirements. All residents except one indicated open repair was a quick procedure. In contrast, a significant number of AHPs thought open repair was time-consuming. The attendings considered all the methods fast. The residents’ opinions were the most consistent with the true operating times reported. According to the literature, total operating time for mini-open repair ranges from 10 to 16 minutes faster than that for arthroscopic repair.18,20,27 Ultimately, procedure duration did not affect the respondents’ technique preference for RCR.

There was substantial disagreement about the number of procedures needed to become proficient in the different repair techniques. Overall, however, there was consensus that arthroscopic and mini-open repairs had longer learning curves than open repair. Given the lack of agreement among orthopedic department chairmen and sports medicine fellowship directors regarding the minimum exposure needed (during residency) to become proficient in diagnostic shoulder arthroscopy,28 this finding is not surprising. Guttmann and colleagues29 attempted to quantify the learning curve for arthroscopic RCR by tracking operating time as a surrogate measure. They found that RCR operative time decreased rapidly during the initial block of 10 cases to the second block of 10 cases, but thereafter improvement continued at a much lower rate.29 None of our respondents thought the learning curve for arthroscopic RCR was under 10 cases, but no group, not even the attendings who performed RCRs, could agree on the minimum number of cases needed for proficiency. The longer learning curve for arthroscopic RCR did not discourage the respondents who preferred arthroscopic or mini-open RCR.

Cost was not an influential factor in opinions about which RCR method is optimal. Medical professionals were ambivalent about the cost-effectiveness of the different procedures, with most expressing no opinion on cost. Multiple investigators have shown that arthroscopic RCR costs as much as $1144 more than mini-open RCR,18,27 which has many of the advantages of arthroscopic repair but not the costly implants and instruments. As our medical community becomes more cost-conscious, concern about this factor may increase among medical professionals.

Our study had several limitations. Its results must be interpreted carefully, given they represent the viewpoints of a nonrandomized sample of motivated respondents at one institution. A selection bias excluded surgeons who were uncomfortable with RCR and unwilling to report any shortcomings. The conclusions cannot be generalized to other medical professionals or to other institutions. Furthermore, to develop a simple, straightforward survey focused on a specific type of rotator cuff tear, and to avoid confusion, we assumed that the treatment preference for the described tear was generalizable to all encountered tears. However, some surgeons have reported different repair techniques for different types and sizes of rotator cuff tears.25

Conclusion

Most of our surveyed medical professionals were willing to defer to their surgeon’s decision about which technique would be appropriate for their own personal RCR. There is a trend nationally, and at our institution, for increased use of arthroscopic RCR. Although medical professionals readily acknowledge it is unclear which repair method provides the best ultimate outcome, many perceive fast recovery and good cosmetic results with arthroscopic and mini-open repairs. When medical professionals are counseling patients, we need to recognize these personal biases because many patients defer to their surgeon’s counsel. For some medical professionals, cosmesis can be an important factor, but cost, procedure duration, potential technical challenges of arthroscopic repair, and other considerations may make other techniques more desirable for others.

1. Bennett WF. Arthroscopic repair of massive rotator cuff tears: a prospective cohort with 2- to 4-year follow-up. Arthroscopy. 2003;19(4):380-390.

2. Bennett WF. Arthroscopic repair of full-thickness supraspinatus tears (small-to-medium): a prospective study with 2- to 4-year follow-up. Arthroscopy. 2003;19(3):249-256.

3. Nho SJ, Shindle MK, Sherman SL, Freedman KB, Lyman S, MacGillivray JD. Systematic review of arthroscopic rotator cuff repair and mini-open rotator cuff repair. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(suppl 3):127-136.

4. Duralde XA, Greene RT. Mini-open rotator cuff repair via an anterosuperior approach. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17(5):715-721.

5. Blevins FT, Warren RF, Cavo C, et al. Arthroscopic assisted rotator cuff repair: results using a mini-open deltoid splitting approach. Arthroscopy. 1996;12(1):50-59.

6. Levy HJ, Uribe JW, Delaney LG. Arthroscopic assisted rotator cuff repair: preliminary results. Arthroscopy. 1990;6(1):55-60.

7. Liu SH. Arthroscopically-assisted rotator-cuff repair. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1994;76(4):592-595.

8. Morse K, Davis AD, Afra R, Kaye EK, Schepsis A, Voloshin I. Arthroscopic versus mini-open rotator cuff repair: a comprehensive review and meta-analysis. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36(9):1824-1828.

9. Park JY, Levine WN, Marra G, Pollock RG, Flatow EL, Bigliani LU. Portal-extension approach for the repair of small and medium rotator cuff tears. Am J Sports Med. 2000;28(3):312-316.

10. Paulos LE, Kody MH. Arthroscopically enhanced “miniapproach” to rotator cuff repair. Am J Sports Med. 1994;22(1):19-25.

11. Posada A, Uribe JW, Hechtman KS, Tjin-A-Tsoi EW, Zvijac JE. Mini-deltoid splitting rotator cuff repair: do results deteriorate with time? Arthroscopy. 2000;16(2):137-141.

12. Shinners TJ, Noordsij PG, Orwin JF. Arthroscopically assisted mini-open rotator cuff repair. Arthroscopy. 2002;18(1):21-26.

13. Weber SC. Arthroscopic debridement and acromioplasty versus mini-open repair in the treatment of significant partial-thickness rotator cuff tears. Arthroscopy. 1999;15(2):126-131.

14. Baker CL, Liu SH. Comparison of open and arthroscopically assisted rotator cuff repairs. Am J Sports Med. 1995;23(1):99-104.

15. Liu SH, Baker CL. Arthroscopically assisted rotator cuff repair: correlation of functional results with integrity of the cuff. Arthroscopy. 1994;10(1):54-60.

16. Pollock RG, Flatow EL. The rotator cuff, part II. Full-thickness tears. Mini-open repair. Orthop Clin North Am. 1997;28(2):169-177.

17. Yamaguchi K, Levine WN, Marra G, Galatz LM, Klepps S, Flatow EL. Transitioning to arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: the pros and cons. Instr Course Lect. 2003;52:81-92.

18. Adla DN, Rowsell M, Pandey R. Cost-effectiveness of open versus arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19(2):258-261.

19. Kose KC, Tezen E, Cebesoy O, et al. Mini-open versus all-arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: comparison of the operative costs and the clinical outcomes. Adv Ther. 2008;25(3):249-259.

20. Colvin AC, Egorova N, Harrison AK, Moskowitz A, Flatow EL. National trends in rotator cuff repair. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(3):227-233.

21. Dunn WR, Schackman BR, Walsh C, et al. Variation in orthopaedic surgeons’ perceptions about the indications for rotator cuff surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(9):1978-1984.

22. Randelli P, Arrigoni P, Cabitza F, Ragone V, Cabitza P. Current practice in shoulder pathology: results of a web-based survey among a community of 1,084 orthopedic surgeons. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2012;20(5):803-815.

23. Aleem AW, Brophy RH. Outcomes of rotator cuff surgery: what does the evidence tell us? Clin Sports Med. 2012;31(4):665-674.

24. Pedowitz RA, Yamaguchi K, Ahmad CS, et al. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons clinical practice guideline on: optimizing the management of rotator cuff problems. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(2):163-167.

25. Vitale MA, Kleweno CP, Jacir AM, Levine WN, Bigliani LU, Ahmad CS. Training resources in arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(6):1393-1398.

26. Mauro CS, Jordan SS, Irrgang JJ, Harner CD. Practice patterns for subacromial decompression and rotator cuff repair: an analysis of the American Board of Orthopaedic Surgery database. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(16):1492-1499.

27. Churchill RS, Ghorai JK. Total cost and operating room time comparison of rotator cuff repair techniques at low, intermediate, and high volume centers: mini-open versus all-arthroscopic. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19(5):716-721.

28. O’Neill PJ, Cosgarea AJ, Freedman JA, Queale WS, McFarland EG. Arthroscopic proficiency: a survey of orthopaedic sports medicine fellowship directors and orthopaedic surgery department chairs. Arthroscopy. 2002;18(7):795-800.

29. Guttmann D, Graham RD, MacLennan MJ, Lubowitz JH. Arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: the learning curve. Arthroscopy. 2005;21(4):394-400.

Rotator cuff tears are a common condition affecting the shoulder joint. Initial open repair techniques were associated with several complications, including severe early postoperative pain, deltoid detachment and/or weakness, risk for infection, and arthrofibrosis.1-3 In addition, open procedures cannot address other possible diagnoses, such as labral tears and loose bodies. These disadvantages promoted the development of an arthroscopically assisted mini-open technique.4 Superior long-term results, with more than 90% of patients achieving good to excellent results,5-13 established the mini-open rotator cuff repair (RCR) as the gold standard.3,6,10,12,14-16

Recently, as instrumentation for arthroscopy has improved, enthusiasm for all-arthroscopic techniques (hereafter referred to as arthroscopic repair) has grown. The appeal of arthroscopic repair includes potentially less initial pain, ability to treat intra-articular lesions concurrently, smaller skin incisions with better cosmesis, less soft-tissue dissection, and low risk for deltoid detachment.3,17 The potential advantages of arthroscopic repair can lead to perceptions of quicker healing and shorter recovery, which are not supported by the literature. However, arthroscopic repair is technically more challenging, time-consuming, and expensive than open or mini-open repairs,18,19 and though some investigators have reported a trend toward fewer complications,3 the long-term outcome of arthroscopic RCRs has not been shown to be better than that of other techniques.

Given that no differences have been shown between the emerging arthroscopic repair technique and mini-open repair with respect to range of motion or clinical scores in the short term,3 it is unclear what perceptions influence choice of technique for one’s own personal RCR.

We conducted a study to determine which RCR technique medical professionals (orthopedic attendings and residents, anesthesiologists, internal medicine attendings, main operating room nurses, and physical therapists) preferred for their own surgery and to analyze perceptions shaping those opinions. Orthopedic surgeons have the best concept of rotator cuff surgery, but anesthesiologists and nurses have a “front row seat” and opinions on types of rotator cuff surgery. Physical therapists, who treat patients with rotator cuff tears, also have a working knowledge of rotator cuff surgery. Finally, internists represent a rotator cuff injury referral service and may have patients who have undergone rotator cuff surgery. We hypothesized that most medical professionals, irrespective of specialty or career length, would prefer arthroscopic RCR because of its perceived superior outcome and fast recovery.

Materials and Methods

This cross-sectional, descriptive, survey-based study was approved by our institutional review board (IRB) and offered via 3 emails between April 2011 and June 2011 to attendings (orthopedists, internists, anesthesiologists), residents, and allied health professionals (AHPs; operating room nurses, physical therapists) involved in orthopedic care at our institution. Each email contained a hyperlink to the online survey (Appendix), which took about 10 minutes to complete and explored respondent demographics, exposure to the different techniques, and opinions regarding different aspects of RCR surgery and recovery.

There were 84 respondents. The sexes were equally represented, and age ranged from 25 to 78 years (Table 1). Of the respondents, 41 (49%) were attendings, 20 (24%) were residents, and 23 (27%) were AHPs. Of the attendings, 13 (32%) were orthopedic surgeons, 26 (63%) were primary care physicians, and 2 (5%) did not specify their specialty. Four orthopedic surgeons had fellowship training in sports medicine or shoulder and elbow surgery. The attendings were overall more experienced in their profession than the other groups were, with 68% reporting more than 5 years of experience.

Descriptive statistics, including means and standard errors, were calculated. Fisher exact test was used to compare preferences of RCR type according to type of training and years of experience. Significance was set at P ≤ .05.

Results

Overall Responses (Table 2)

Of the 84 respondents, almost half (46%) preferred deferring their choice of RCR to their surgeon. Most of the other respondents preferred the arthroscopic technique (26%) or the mini-open repair (23%). There was no association between technique preference and medical professional type. Most respondents (63%) had never assisted in or performed rotator cuff surgery.

Seventy-four percent of all respondents indicated they thought arthroscopic, mini-open, and open RCRs are safe, and about half thought these procedures are fast. About half expressed no opinion about the cost-effectiveness of arthroscopic, mini-open, or open RCRs (54%, 52%, and 48%, respectively), and slightly more than half expressed no opinion about whether arthroscopic, mini-open, or open RCR provide the best outcome (58%, 60%, and 62%, respectively). Significantly (P < .05) more respondents thought arthroscopic and mini-open repairs, rather than open repairs, promote quick healing (64% and 45%, respectively, vs 15%), good cosmetic results (81% and 51%, respectively, vs 10%), and patient satisfaction (50% and 48%, respectively, vs 30%). However, a significant (P < .05) number also thought arthroscopic and mini-open repairs are harder to learn/more challenging to perform than open repairs (52% and 38%, respectively, vs 17%).

Of all factors considered, safety of arthroscopic repair garnered the highest consensus: 82%. Respondents were least opinionated about the outcome of the open repair technique, with more than 62% expressing no opinion about the outcome. The responses to the questions on the learning curves for the 3 techniques varied the most.

Responses by Group (Table 2)

Attendings. Of the 41 attendings, 24 (59%) responded they would defer to their surgeon’s technique preference for RCR. Of the other 17 who expressed a preference, most indicated arthroscopic or mini-open repair (17% each). There was a difference (P < .05) between years of experience and RCR preference: of the 13 attendings with less than 5 years of experience, arthroscopic repair was preferred by 31%; in contrast, of the 28 attendings with more than 5 years of experience, only 11% preferred arthroscopic repair.

Of the 11 attendings who performed rotator cuff surgery, 55% used the open technique, but most (8) preferred to have their own rotator cuff fixed arthroscopically or according to their surgeon’s preference. Only 1 surgeon preferred open repair for his own rotator cuff. Of the 4 surgeons who performed arthroscopic RCRs, 3 had less than 5 years of experience. Conversely, all 7 surgeons who performed mini-open or open repairs had more than 5 years of experience.

Of the 30 attendings who did not perform rotator cuff surgery, most (20) responded they would defer to their surgeon’s technique preference for RCR.

The attendings’ opinions on factors affecting rotator cuff surgery were similar to those of the other respondents with respect to safety, cost-effectiveness, recovery, cosmesis, patient satisfaction, outcome, and technical difficulty. Unlike the others, however, attendings considered all 3 repair techniques fast.

Residents. Of the 20 residents, 7 preferred arthroscopic, 5 preferred mini-open, and 1 preferred open repair; the other 7 responded they would defer to their surgeon’s preference. Residents’ opinions on each factor were more polarized and consistent across categories than those of the other groups. Residents overwhelmingly thought all 3 techniques (arthroscopic, mini-open, open) are safe (19, 19, and 18, respectively) and cost-effective (12, 14, and 14, respectively). Although most residents considered the open and mini-open repair techniques fast (19 and 15, respectively), only 8 considered arthroscopic RCR fast, and 4 considered it slow. Residents’ opinions about the technique that produces the best outcome were mixed. As with the other respondents, residents thought arthroscopic RCRs heal fast and produce great cosmetic results, but are challenging to perform and have a steep learning curve. Unlike the other respondents, most residents (12) considered open RCR easy to learn (P = .006), with a learning curve of fewer than 20 procedures.

AHPs. No AHP expressed a preference for open RCR. This group was evenly divided among 3 choices: deferring to their surgeon’s preference, arthroscopic repair, and mini-open repair. The 23 AHPs thought arthroscopic, mini-open, and open repairs are safe (17, 15, and 12, respectively), but most indicated they were “equivocal” about which techniques are cost-effective, challenging to perform, and produce the best outcomes. A significantly (P = .014) larger number of AHPs (7) considered open rotator cuff surgery slow compared with arthroscopic (0) and mini-open (2) repair techniques. As with the overall cohort, AHPs reported arthroscopic and mini-open repairs promote quick healing and good cosmetic results, but are challenging to perform.

Discussion

As our population ages and continues to remain active, the demand for RCR has accelerated. National data show that 272,148 ambulatory RCRs and 20,433 inpatient RCRs were performed in 2006—an overall 141% increase in RCR since 1996.20 In 1996, 41 per 100,000 population underwent RCR.20 By 2006, this number ballooned to 98 per 100,000 population.20 There are 3 predominant techniques for repairing the rotator cuff: open, mini-open, and arthroscopic. As RCR use increases, we should consider the factors that medical professionals consider important when choosing a method for their own RCR.

Of the 84 medical professionals in our cohort, 39 (46%) indicated they would defer to their surgeon’s technique preference for RCR. Of the other 45, about equal numbers preferred arthroscopic and mini-open RCRs; only 2 preferred open RCRs. This finding suggests that the individual opinions of surgeons who perform RCRs have a substantial influence on a large proportion of medical professionals’ ultimate choice of RCR method. Interestingly, of the attendings who performed open RCR, only 1 expressed a preference for the open technique for his own RCR. This finding might suggest a shift in opinion and an emerging perception among surgeons performing RCR about the value of this technique.

Several factors may account for these evolving beliefs. We hypothesized that a biased favorable view of arthroscopic repair outcome might influence opinions. However, our results did not support the hypothesis. Medical professionals in our cohort were equivocal about the best RCR technique. No consensus was evident among attendings, residents, or AHPs. This lack of clinical agreement about rotator cuff surgery has been observed elsewhere—for example, among members of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS)21 and the European Society of Sports Traumatology, Knee Surgery, and Arthroscopy.22 Despite theoretical advantages of arthroscopic repair, there has been no documented significant difference in patient outcomes when compared with other techniques.23 To our knowledge, there have been only a few clinical studies comparing the different RCR techniques. A meta-analysis of 5 clinical studies comparing arthroscopic and mini-open RCR techniques showed no difference in clinical outcomes or complication rates.8 The 2012 AAOS clinical practice guidelines for RCR reflect these observations.24 That consortium of leading shoulder surgeons could not recommend a modality of surgical rotator cuff tear repair given the lack of conclusive evidence.24

At our institution, arthroscopic, mini-open, and open RCRs were performed by 36%, 9%, and 55% of our surgeons, respectively. A survey of AAOS surgeons showed that, of those who perform RCRs, 14.5%, 46.2%, and 36.6% used arthroscopic, mini-open, and open techniques, respectively.21 The greater use of open repairs at our institution might reflect the seniority of our faculty. Dunn and colleagues21 found that surgeons who preferred open RCR had been in practice longer than those who preferred the arthroscopic or mini-open technique. Of our 4 faculty who performed arthroscopic repairs, 3 were less than 5 years from completing their training. In contrast, all faculty who performed mini-open or open repairs were more than 5 years from completing their training. Furthermore, mean age of the surgeons who performed arthroscopic repair was 39.8 years (range, 32-51 years), and these surgeons were significantly younger than those who performed mini-open or open repair (mean age, 56.3 years; range, 41-78 years). Younger surgeon age has been associated with higher rates of arthroscopic repair.25

Attendings unaccustomed to arthroscopy may find it more challenging than the younger generation of surgeons, who are exposed to it early in training. Dunn and colleagues21 noted that the likelihood of performing an arthroscopic repair was influenced by the surgeon’s experience level. Fellowship-trained shoulder and sports medicine surgeons are also more likely to perform arthroscopic repairs than those with training limited to orthopedic residency.25 Arthroscopic RCR demands a high level of technical skill that many acquire in fellowship training.26 Mauro and colleagues26 found that surgeons trained in a sports medicine fellowship performed 82.6% of subacromial decompression and/or RCR procedures arthroscopically, compared with 54.5% to 70.1% for surgeons trained in other fellowships. In our cohort, with the exception of 1 surgeon, all fellowship-trained shoulder and sports medicine surgeons performed arthroscopic RCRs.

Although no conclusive evidence in the literature supports arthroscopic over the other repair types, the demand for arthroscopic RCR has rapidly increased relative to that for the others. Between 1996 and 2006, use of arthroscopic RCR increased 600%, from 8 to 58 per 100,000 population.20 In that same period, use of open RCR increased by only 34%.20 Similarly, Mauro and colleagues26 found that the proportion of subacromial decompression and RCRs performed arthroscopically rose from 58.3% in 2004 to 83.7% in 2009. Using the 2006 New York State Ambulatory Surgery Database, Churchill and Ghorai27 found that 74.5% of RCRs with acromioplasty were performed arthroscopically.

Respondent-indicated factors that may have contributed to the more favorable opinion of arthroscopic and mini-open repair include quick healing, good cosmetic results, and better perceived patient satisfaction. The literature supports these perceptions. Baker and Liu14 found shorter hospital stays and quicker return to activity with arthroscopic repair compared with open repair. Vitale and colleagues25 also noted that, compared with open or mini-open repair techniques, arthroscopic repair resulted in shorter hospitalization and quicker overall recovery.

If these selected health care professionals with some inside information on rotator cuff surgery have biases that affect their selection of rotator cuff procedures, we should acknowledge that nonmedical personnel, in particular our patients, also have biases. The knowledge base of patients may be further influenced by friends or family members who have had rotator cuff surgery, by lay publications, and by the Internet. Satisfaction with any surgical procedure depends not only on the success of the surgery and the rehabilitation but also on patient and provider expectations. Such expectations are influenced, in part, by biases.

Our medical professionals had similar opinions on safety, recovery, cosmesis, and overall outcome of the RCR techniques, but different opinions on procedure durations and associated training requirements. All residents except one indicated open repair was a quick procedure. In contrast, a significant number of AHPs thought open repair was time-consuming. The attendings considered all the methods fast. The residents’ opinions were the most consistent with the true operating times reported. According to the literature, total operating time for mini-open repair ranges from 10 to 16 minutes faster than that for arthroscopic repair.18,20,27 Ultimately, procedure duration did not affect the respondents’ technique preference for RCR.

There was substantial disagreement about the number of procedures needed to become proficient in the different repair techniques. Overall, however, there was consensus that arthroscopic and mini-open repairs had longer learning curves than open repair. Given the lack of agreement among orthopedic department chairmen and sports medicine fellowship directors regarding the minimum exposure needed (during residency) to become proficient in diagnostic shoulder arthroscopy,28 this finding is not surprising. Guttmann and colleagues29 attempted to quantify the learning curve for arthroscopic RCR by tracking operating time as a surrogate measure. They found that RCR operative time decreased rapidly during the initial block of 10 cases to the second block of 10 cases, but thereafter improvement continued at a much lower rate.29 None of our respondents thought the learning curve for arthroscopic RCR was under 10 cases, but no group, not even the attendings who performed RCRs, could agree on the minimum number of cases needed for proficiency. The longer learning curve for arthroscopic RCR did not discourage the respondents who preferred arthroscopic or mini-open RCR.

Cost was not an influential factor in opinions about which RCR method is optimal. Medical professionals were ambivalent about the cost-effectiveness of the different procedures, with most expressing no opinion on cost. Multiple investigators have shown that arthroscopic RCR costs as much as $1144 more than mini-open RCR,18,27 which has many of the advantages of arthroscopic repair but not the costly implants and instruments. As our medical community becomes more cost-conscious, concern about this factor may increase among medical professionals.

Our study had several limitations. Its results must be interpreted carefully, given they represent the viewpoints of a nonrandomized sample of motivated respondents at one institution. A selection bias excluded surgeons who were uncomfortable with RCR and unwilling to report any shortcomings. The conclusions cannot be generalized to other medical professionals or to other institutions. Furthermore, to develop a simple, straightforward survey focused on a specific type of rotator cuff tear, and to avoid confusion, we assumed that the treatment preference for the described tear was generalizable to all encountered tears. However, some surgeons have reported different repair techniques for different types and sizes of rotator cuff tears.25

Conclusion

Most of our surveyed medical professionals were willing to defer to their surgeon’s decision about which technique would be appropriate for their own personal RCR. There is a trend nationally, and at our institution, for increased use of arthroscopic RCR. Although medical professionals readily acknowledge it is unclear which repair method provides the best ultimate outcome, many perceive fast recovery and good cosmetic results with arthroscopic and mini-open repairs. When medical professionals are counseling patients, we need to recognize these personal biases because many patients defer to their surgeon’s counsel. For some medical professionals, cosmesis can be an important factor, but cost, procedure duration, potential technical challenges of arthroscopic repair, and other considerations may make other techniques more desirable for others.

Rotator cuff tears are a common condition affecting the shoulder joint. Initial open repair techniques were associated with several complications, including severe early postoperative pain, deltoid detachment and/or weakness, risk for infection, and arthrofibrosis.1-3 In addition, open procedures cannot address other possible diagnoses, such as labral tears and loose bodies. These disadvantages promoted the development of an arthroscopically assisted mini-open technique.4 Superior long-term results, with more than 90% of patients achieving good to excellent results,5-13 established the mini-open rotator cuff repair (RCR) as the gold standard.3,6,10,12,14-16

Recently, as instrumentation for arthroscopy has improved, enthusiasm for all-arthroscopic techniques (hereafter referred to as arthroscopic repair) has grown. The appeal of arthroscopic repair includes potentially less initial pain, ability to treat intra-articular lesions concurrently, smaller skin incisions with better cosmesis, less soft-tissue dissection, and low risk for deltoid detachment.3,17 The potential advantages of arthroscopic repair can lead to perceptions of quicker healing and shorter recovery, which are not supported by the literature. However, arthroscopic repair is technically more challenging, time-consuming, and expensive than open or mini-open repairs,18,19 and though some investigators have reported a trend toward fewer complications,3 the long-term outcome of arthroscopic RCRs has not been shown to be better than that of other techniques.

Given that no differences have been shown between the emerging arthroscopic repair technique and mini-open repair with respect to range of motion or clinical scores in the short term,3 it is unclear what perceptions influence choice of technique for one’s own personal RCR.

We conducted a study to determine which RCR technique medical professionals (orthopedic attendings and residents, anesthesiologists, internal medicine attendings, main operating room nurses, and physical therapists) preferred for their own surgery and to analyze perceptions shaping those opinions. Orthopedic surgeons have the best concept of rotator cuff surgery, but anesthesiologists and nurses have a “front row seat” and opinions on types of rotator cuff surgery. Physical therapists, who treat patients with rotator cuff tears, also have a working knowledge of rotator cuff surgery. Finally, internists represent a rotator cuff injury referral service and may have patients who have undergone rotator cuff surgery. We hypothesized that most medical professionals, irrespective of specialty or career length, would prefer arthroscopic RCR because of its perceived superior outcome and fast recovery.

Materials and Methods

This cross-sectional, descriptive, survey-based study was approved by our institutional review board (IRB) and offered via 3 emails between April 2011 and June 2011 to attendings (orthopedists, internists, anesthesiologists), residents, and allied health professionals (AHPs; operating room nurses, physical therapists) involved in orthopedic care at our institution. Each email contained a hyperlink to the online survey (Appendix), which took about 10 minutes to complete and explored respondent demographics, exposure to the different techniques, and opinions regarding different aspects of RCR surgery and recovery.

There were 84 respondents. The sexes were equally represented, and age ranged from 25 to 78 years (Table 1). Of the respondents, 41 (49%) were attendings, 20 (24%) were residents, and 23 (27%) were AHPs. Of the attendings, 13 (32%) were orthopedic surgeons, 26 (63%) were primary care physicians, and 2 (5%) did not specify their specialty. Four orthopedic surgeons had fellowship training in sports medicine or shoulder and elbow surgery. The attendings were overall more experienced in their profession than the other groups were, with 68% reporting more than 5 years of experience.

Descriptive statistics, including means and standard errors, were calculated. Fisher exact test was used to compare preferences of RCR type according to type of training and years of experience. Significance was set at P ≤ .05.

Results

Overall Responses (Table 2)

Of the 84 respondents, almost half (46%) preferred deferring their choice of RCR to their surgeon. Most of the other respondents preferred the arthroscopic technique (26%) or the mini-open repair (23%). There was no association between technique preference and medical professional type. Most respondents (63%) had never assisted in or performed rotator cuff surgery.

Seventy-four percent of all respondents indicated they thought arthroscopic, mini-open, and open RCRs are safe, and about half thought these procedures are fast. About half expressed no opinion about the cost-effectiveness of arthroscopic, mini-open, or open RCRs (54%, 52%, and 48%, respectively), and slightly more than half expressed no opinion about whether arthroscopic, mini-open, or open RCR provide the best outcome (58%, 60%, and 62%, respectively). Significantly (P < .05) more respondents thought arthroscopic and mini-open repairs, rather than open repairs, promote quick healing (64% and 45%, respectively, vs 15%), good cosmetic results (81% and 51%, respectively, vs 10%), and patient satisfaction (50% and 48%, respectively, vs 30%). However, a significant (P < .05) number also thought arthroscopic and mini-open repairs are harder to learn/more challenging to perform than open repairs (52% and 38%, respectively, vs 17%).

Of all factors considered, safety of arthroscopic repair garnered the highest consensus: 82%. Respondents were least opinionated about the outcome of the open repair technique, with more than 62% expressing no opinion about the outcome. The responses to the questions on the learning curves for the 3 techniques varied the most.

Responses by Group (Table 2)

Attendings. Of the 41 attendings, 24 (59%) responded they would defer to their surgeon’s technique preference for RCR. Of the other 17 who expressed a preference, most indicated arthroscopic or mini-open repair (17% each). There was a difference (P < .05) between years of experience and RCR preference: of the 13 attendings with less than 5 years of experience, arthroscopic repair was preferred by 31%; in contrast, of the 28 attendings with more than 5 years of experience, only 11% preferred arthroscopic repair.

Of the 11 attendings who performed rotator cuff surgery, 55% used the open technique, but most (8) preferred to have their own rotator cuff fixed arthroscopically or according to their surgeon’s preference. Only 1 surgeon preferred open repair for his own rotator cuff. Of the 4 surgeons who performed arthroscopic RCRs, 3 had less than 5 years of experience. Conversely, all 7 surgeons who performed mini-open or open repairs had more than 5 years of experience.

Of the 30 attendings who did not perform rotator cuff surgery, most (20) responded they would defer to their surgeon’s technique preference for RCR.

The attendings’ opinions on factors affecting rotator cuff surgery were similar to those of the other respondents with respect to safety, cost-effectiveness, recovery, cosmesis, patient satisfaction, outcome, and technical difficulty. Unlike the others, however, attendings considered all 3 repair techniques fast.

Residents. Of the 20 residents, 7 preferred arthroscopic, 5 preferred mini-open, and 1 preferred open repair; the other 7 responded they would defer to their surgeon’s preference. Residents’ opinions on each factor were more polarized and consistent across categories than those of the other groups. Residents overwhelmingly thought all 3 techniques (arthroscopic, mini-open, open) are safe (19, 19, and 18, respectively) and cost-effective (12, 14, and 14, respectively). Although most residents considered the open and mini-open repair techniques fast (19 and 15, respectively), only 8 considered arthroscopic RCR fast, and 4 considered it slow. Residents’ opinions about the technique that produces the best outcome were mixed. As with the other respondents, residents thought arthroscopic RCRs heal fast and produce great cosmetic results, but are challenging to perform and have a steep learning curve. Unlike the other respondents, most residents (12) considered open RCR easy to learn (P = .006), with a learning curve of fewer than 20 procedures.

AHPs. No AHP expressed a preference for open RCR. This group was evenly divided among 3 choices: deferring to their surgeon’s preference, arthroscopic repair, and mini-open repair. The 23 AHPs thought arthroscopic, mini-open, and open repairs are safe (17, 15, and 12, respectively), but most indicated they were “equivocal” about which techniques are cost-effective, challenging to perform, and produce the best outcomes. A significantly (P = .014) larger number of AHPs (7) considered open rotator cuff surgery slow compared with arthroscopic (0) and mini-open (2) repair techniques. As with the overall cohort, AHPs reported arthroscopic and mini-open repairs promote quick healing and good cosmetic results, but are challenging to perform.

Discussion

As our population ages and continues to remain active, the demand for RCR has accelerated. National data show that 272,148 ambulatory RCRs and 20,433 inpatient RCRs were performed in 2006—an overall 141% increase in RCR since 1996.20 In 1996, 41 per 100,000 population underwent RCR.20 By 2006, this number ballooned to 98 per 100,000 population.20 There are 3 predominant techniques for repairing the rotator cuff: open, mini-open, and arthroscopic. As RCR use increases, we should consider the factors that medical professionals consider important when choosing a method for their own RCR.

Of the 84 medical professionals in our cohort, 39 (46%) indicated they would defer to their surgeon’s technique preference for RCR. Of the other 45, about equal numbers preferred arthroscopic and mini-open RCRs; only 2 preferred open RCRs. This finding suggests that the individual opinions of surgeons who perform RCRs have a substantial influence on a large proportion of medical professionals’ ultimate choice of RCR method. Interestingly, of the attendings who performed open RCR, only 1 expressed a preference for the open technique for his own RCR. This finding might suggest a shift in opinion and an emerging perception among surgeons performing RCR about the value of this technique.

Several factors may account for these evolving beliefs. We hypothesized that a biased favorable view of arthroscopic repair outcome might influence opinions. However, our results did not support the hypothesis. Medical professionals in our cohort were equivocal about the best RCR technique. No consensus was evident among attendings, residents, or AHPs. This lack of clinical agreement about rotator cuff surgery has been observed elsewhere—for example, among members of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS)21 and the European Society of Sports Traumatology, Knee Surgery, and Arthroscopy.22 Despite theoretical advantages of arthroscopic repair, there has been no documented significant difference in patient outcomes when compared with other techniques.23 To our knowledge, there have been only a few clinical studies comparing the different RCR techniques. A meta-analysis of 5 clinical studies comparing arthroscopic and mini-open RCR techniques showed no difference in clinical outcomes or complication rates.8 The 2012 AAOS clinical practice guidelines for RCR reflect these observations.24 That consortium of leading shoulder surgeons could not recommend a modality of surgical rotator cuff tear repair given the lack of conclusive evidence.24

At our institution, arthroscopic, mini-open, and open RCRs were performed by 36%, 9%, and 55% of our surgeons, respectively. A survey of AAOS surgeons showed that, of those who perform RCRs, 14.5%, 46.2%, and 36.6% used arthroscopic, mini-open, and open techniques, respectively.21 The greater use of open repairs at our institution might reflect the seniority of our faculty. Dunn and colleagues21 found that surgeons who preferred open RCR had been in practice longer than those who preferred the arthroscopic or mini-open technique. Of our 4 faculty who performed arthroscopic repairs, 3 were less than 5 years from completing their training. In contrast, all faculty who performed mini-open or open repairs were more than 5 years from completing their training. Furthermore, mean age of the surgeons who performed arthroscopic repair was 39.8 years (range, 32-51 years), and these surgeons were significantly younger than those who performed mini-open or open repair (mean age, 56.3 years; range, 41-78 years). Younger surgeon age has been associated with higher rates of arthroscopic repair.25

Attendings unaccustomed to arthroscopy may find it more challenging than the younger generation of surgeons, who are exposed to it early in training. Dunn and colleagues21 noted that the likelihood of performing an arthroscopic repair was influenced by the surgeon’s experience level. Fellowship-trained shoulder and sports medicine surgeons are also more likely to perform arthroscopic repairs than those with training limited to orthopedic residency.25 Arthroscopic RCR demands a high level of technical skill that many acquire in fellowship training.26 Mauro and colleagues26 found that surgeons trained in a sports medicine fellowship performed 82.6% of subacromial decompression and/or RCR procedures arthroscopically, compared with 54.5% to 70.1% for surgeons trained in other fellowships. In our cohort, with the exception of 1 surgeon, all fellowship-trained shoulder and sports medicine surgeons performed arthroscopic RCRs.

Although no conclusive evidence in the literature supports arthroscopic over the other repair types, the demand for arthroscopic RCR has rapidly increased relative to that for the others. Between 1996 and 2006, use of arthroscopic RCR increased 600%, from 8 to 58 per 100,000 population.20 In that same period, use of open RCR increased by only 34%.20 Similarly, Mauro and colleagues26 found that the proportion of subacromial decompression and RCRs performed arthroscopically rose from 58.3% in 2004 to 83.7% in 2009. Using the 2006 New York State Ambulatory Surgery Database, Churchill and Ghorai27 found that 74.5% of RCRs with acromioplasty were performed arthroscopically.

Respondent-indicated factors that may have contributed to the more favorable opinion of arthroscopic and mini-open repair include quick healing, good cosmetic results, and better perceived patient satisfaction. The literature supports these perceptions. Baker and Liu14 found shorter hospital stays and quicker return to activity with arthroscopic repair compared with open repair. Vitale and colleagues25 also noted that, compared with open or mini-open repair techniques, arthroscopic repair resulted in shorter hospitalization and quicker overall recovery.

If these selected health care professionals with some inside information on rotator cuff surgery have biases that affect their selection of rotator cuff procedures, we should acknowledge that nonmedical personnel, in particular our patients, also have biases. The knowledge base of patients may be further influenced by friends or family members who have had rotator cuff surgery, by lay publications, and by the Internet. Satisfaction with any surgical procedure depends not only on the success of the surgery and the rehabilitation but also on patient and provider expectations. Such expectations are influenced, in part, by biases.

Our medical professionals had similar opinions on safety, recovery, cosmesis, and overall outcome of the RCR techniques, but different opinions on procedure durations and associated training requirements. All residents except one indicated open repair was a quick procedure. In contrast, a significant number of AHPs thought open repair was time-consuming. The attendings considered all the methods fast. The residents’ opinions were the most consistent with the true operating times reported. According to the literature, total operating time for mini-open repair ranges from 10 to 16 minutes faster than that for arthroscopic repair.18,20,27 Ultimately, procedure duration did not affect the respondents’ technique preference for RCR.

There was substantial disagreement about the number of procedures needed to become proficient in the different repair techniques. Overall, however, there was consensus that arthroscopic and mini-open repairs had longer learning curves than open repair. Given the lack of agreement among orthopedic department chairmen and sports medicine fellowship directors regarding the minimum exposure needed (during residency) to become proficient in diagnostic shoulder arthroscopy,28 this finding is not surprising. Guttmann and colleagues29 attempted to quantify the learning curve for arthroscopic RCR by tracking operating time as a surrogate measure. They found that RCR operative time decreased rapidly during the initial block of 10 cases to the second block of 10 cases, but thereafter improvement continued at a much lower rate.29 None of our respondents thought the learning curve for arthroscopic RCR was under 10 cases, but no group, not even the attendings who performed RCRs, could agree on the minimum number of cases needed for proficiency. The longer learning curve for arthroscopic RCR did not discourage the respondents who preferred arthroscopic or mini-open RCR.

Cost was not an influential factor in opinions about which RCR method is optimal. Medical professionals were ambivalent about the cost-effectiveness of the different procedures, with most expressing no opinion on cost. Multiple investigators have shown that arthroscopic RCR costs as much as $1144 more than mini-open RCR,18,27 which has many of the advantages of arthroscopic repair but not the costly implants and instruments. As our medical community becomes more cost-conscious, concern about this factor may increase among medical professionals.

Our study had several limitations. Its results must be interpreted carefully, given they represent the viewpoints of a nonrandomized sample of motivated respondents at one institution. A selection bias excluded surgeons who were uncomfortable with RCR and unwilling to report any shortcomings. The conclusions cannot be generalized to other medical professionals or to other institutions. Furthermore, to develop a simple, straightforward survey focused on a specific type of rotator cuff tear, and to avoid confusion, we assumed that the treatment preference for the described tear was generalizable to all encountered tears. However, some surgeons have reported different repair techniques for different types and sizes of rotator cuff tears.25

Conclusion

Most of our surveyed medical professionals were willing to defer to their surgeon’s decision about which technique would be appropriate for their own personal RCR. There is a trend nationally, and at our institution, for increased use of arthroscopic RCR. Although medical professionals readily acknowledge it is unclear which repair method provides the best ultimate outcome, many perceive fast recovery and good cosmetic results with arthroscopic and mini-open repairs. When medical professionals are counseling patients, we need to recognize these personal biases because many patients defer to their surgeon’s counsel. For some medical professionals, cosmesis can be an important factor, but cost, procedure duration, potential technical challenges of arthroscopic repair, and other considerations may make other techniques more desirable for others.

1. Bennett WF. Arthroscopic repair of massive rotator cuff tears: a prospective cohort with 2- to 4-year follow-up. Arthroscopy. 2003;19(4):380-390.

2. Bennett WF. Arthroscopic repair of full-thickness supraspinatus tears (small-to-medium): a prospective study with 2- to 4-year follow-up. Arthroscopy. 2003;19(3):249-256.

3. Nho SJ, Shindle MK, Sherman SL, Freedman KB, Lyman S, MacGillivray JD. Systematic review of arthroscopic rotator cuff repair and mini-open rotator cuff repair. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(suppl 3):127-136.

4. Duralde XA, Greene RT. Mini-open rotator cuff repair via an anterosuperior approach. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17(5):715-721.

5. Blevins FT, Warren RF, Cavo C, et al. Arthroscopic assisted rotator cuff repair: results using a mini-open deltoid splitting approach. Arthroscopy. 1996;12(1):50-59.

6. Levy HJ, Uribe JW, Delaney LG. Arthroscopic assisted rotator cuff repair: preliminary results. Arthroscopy. 1990;6(1):55-60.

7. Liu SH. Arthroscopically-assisted rotator-cuff repair. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1994;76(4):592-595.

8. Morse K, Davis AD, Afra R, Kaye EK, Schepsis A, Voloshin I. Arthroscopic versus mini-open rotator cuff repair: a comprehensive review and meta-analysis. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36(9):1824-1828.

9. Park JY, Levine WN, Marra G, Pollock RG, Flatow EL, Bigliani LU. Portal-extension approach for the repair of small and medium rotator cuff tears. Am J Sports Med. 2000;28(3):312-316.

10. Paulos LE, Kody MH. Arthroscopically enhanced “miniapproach” to rotator cuff repair. Am J Sports Med. 1994;22(1):19-25.

11. Posada A, Uribe JW, Hechtman KS, Tjin-A-Tsoi EW, Zvijac JE. Mini-deltoid splitting rotator cuff repair: do results deteriorate with time? Arthroscopy. 2000;16(2):137-141.

12. Shinners TJ, Noordsij PG, Orwin JF. Arthroscopically assisted mini-open rotator cuff repair. Arthroscopy. 2002;18(1):21-26.

13. Weber SC. Arthroscopic debridement and acromioplasty versus mini-open repair in the treatment of significant partial-thickness rotator cuff tears. Arthroscopy. 1999;15(2):126-131.

14. Baker CL, Liu SH. Comparison of open and arthroscopically assisted rotator cuff repairs. Am J Sports Med. 1995;23(1):99-104.

15. Liu SH, Baker CL. Arthroscopically assisted rotator cuff repair: correlation of functional results with integrity of the cuff. Arthroscopy. 1994;10(1):54-60.

16. Pollock RG, Flatow EL. The rotator cuff, part II. Full-thickness tears. Mini-open repair. Orthop Clin North Am. 1997;28(2):169-177.

17. Yamaguchi K, Levine WN, Marra G, Galatz LM, Klepps S, Flatow EL. Transitioning to arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: the pros and cons. Instr Course Lect. 2003;52:81-92.

18. Adla DN, Rowsell M, Pandey R. Cost-effectiveness of open versus arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19(2):258-261.

19. Kose KC, Tezen E, Cebesoy O, et al. Mini-open versus all-arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: comparison of the operative costs and the clinical outcomes. Adv Ther. 2008;25(3):249-259.

20. Colvin AC, Egorova N, Harrison AK, Moskowitz A, Flatow EL. National trends in rotator cuff repair. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(3):227-233.

21. Dunn WR, Schackman BR, Walsh C, et al. Variation in orthopaedic surgeons’ perceptions about the indications for rotator cuff surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(9):1978-1984.

22. Randelli P, Arrigoni P, Cabitza F, Ragone V, Cabitza P. Current practice in shoulder pathology: results of a web-based survey among a community of 1,084 orthopedic surgeons. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2012;20(5):803-815.

23. Aleem AW, Brophy RH. Outcomes of rotator cuff surgery: what does the evidence tell us? Clin Sports Med. 2012;31(4):665-674.

24. Pedowitz RA, Yamaguchi K, Ahmad CS, et al. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons clinical practice guideline on: optimizing the management of rotator cuff problems. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(2):163-167.

25. Vitale MA, Kleweno CP, Jacir AM, Levine WN, Bigliani LU, Ahmad CS. Training resources in arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(6):1393-1398.

26. Mauro CS, Jordan SS, Irrgang JJ, Harner CD. Practice patterns for subacromial decompression and rotator cuff repair: an analysis of the American Board of Orthopaedic Surgery database. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(16):1492-1499.

27. Churchill RS, Ghorai JK. Total cost and operating room time comparison of rotator cuff repair techniques at low, intermediate, and high volume centers: mini-open versus all-arthroscopic. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19(5):716-721.

28. O’Neill PJ, Cosgarea AJ, Freedman JA, Queale WS, McFarland EG. Arthroscopic proficiency: a survey of orthopaedic sports medicine fellowship directors and orthopaedic surgery department chairs. Arthroscopy. 2002;18(7):795-800.

29. Guttmann D, Graham RD, MacLennan MJ, Lubowitz JH. Arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: the learning curve. Arthroscopy. 2005;21(4):394-400.

1. Bennett WF. Arthroscopic repair of massive rotator cuff tears: a prospective cohort with 2- to 4-year follow-up. Arthroscopy. 2003;19(4):380-390.

2. Bennett WF. Arthroscopic repair of full-thickness supraspinatus tears (small-to-medium): a prospective study with 2- to 4-year follow-up. Arthroscopy. 2003;19(3):249-256.

3. Nho SJ, Shindle MK, Sherman SL, Freedman KB, Lyman S, MacGillivray JD. Systematic review of arthroscopic rotator cuff repair and mini-open rotator cuff repair. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(suppl 3):127-136.

4. Duralde XA, Greene RT. Mini-open rotator cuff repair via an anterosuperior approach. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17(5):715-721.

5. Blevins FT, Warren RF, Cavo C, et al. Arthroscopic assisted rotator cuff repair: results using a mini-open deltoid splitting approach. Arthroscopy. 1996;12(1):50-59.

6. Levy HJ, Uribe JW, Delaney LG. Arthroscopic assisted rotator cuff repair: preliminary results. Arthroscopy. 1990;6(1):55-60.

7. Liu SH. Arthroscopically-assisted rotator-cuff repair. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1994;76(4):592-595.

8. Morse K, Davis AD, Afra R, Kaye EK, Schepsis A, Voloshin I. Arthroscopic versus mini-open rotator cuff repair: a comprehensive review and meta-analysis. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36(9):1824-1828.

9. Park JY, Levine WN, Marra G, Pollock RG, Flatow EL, Bigliani LU. Portal-extension approach for the repair of small and medium rotator cuff tears. Am J Sports Med. 2000;28(3):312-316.

10. Paulos LE, Kody MH. Arthroscopically enhanced “miniapproach” to rotator cuff repair. Am J Sports Med. 1994;22(1):19-25.

11. Posada A, Uribe JW, Hechtman KS, Tjin-A-Tsoi EW, Zvijac JE. Mini-deltoid splitting rotator cuff repair: do results deteriorate with time? Arthroscopy. 2000;16(2):137-141.

12. Shinners TJ, Noordsij PG, Orwin JF. Arthroscopically assisted mini-open rotator cuff repair. Arthroscopy. 2002;18(1):21-26.

13. Weber SC. Arthroscopic debridement and acromioplasty versus mini-open repair in the treatment of significant partial-thickness rotator cuff tears. Arthroscopy. 1999;15(2):126-131.

14. Baker CL, Liu SH. Comparison of open and arthroscopically assisted rotator cuff repairs. Am J Sports Med. 1995;23(1):99-104.

15. Liu SH, Baker CL. Arthroscopically assisted rotator cuff repair: correlation of functional results with integrity of the cuff. Arthroscopy. 1994;10(1):54-60.

16. Pollock RG, Flatow EL. The rotator cuff, part II. Full-thickness tears. Mini-open repair. Orthop Clin North Am. 1997;28(2):169-177.

17. Yamaguchi K, Levine WN, Marra G, Galatz LM, Klepps S, Flatow EL. Transitioning to arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: the pros and cons. Instr Course Lect. 2003;52:81-92.

18. Adla DN, Rowsell M, Pandey R. Cost-effectiveness of open versus arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19(2):258-261.

19. Kose KC, Tezen E, Cebesoy O, et al. Mini-open versus all-arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: comparison of the operative costs and the clinical outcomes. Adv Ther. 2008;25(3):249-259.

20. Colvin AC, Egorova N, Harrison AK, Moskowitz A, Flatow EL. National trends in rotator cuff repair. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(3):227-233.

21. Dunn WR, Schackman BR, Walsh C, et al. Variation in orthopaedic surgeons’ perceptions about the indications for rotator cuff surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(9):1978-1984.

22. Randelli P, Arrigoni P, Cabitza F, Ragone V, Cabitza P. Current practice in shoulder pathology: results of a web-based survey among a community of 1,084 orthopedic surgeons. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2012;20(5):803-815.

23. Aleem AW, Brophy RH. Outcomes of rotator cuff surgery: what does the evidence tell us? Clin Sports Med. 2012;31(4):665-674.

24. Pedowitz RA, Yamaguchi K, Ahmad CS, et al. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons clinical practice guideline on: optimizing the management of rotator cuff problems. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(2):163-167.

25. Vitale MA, Kleweno CP, Jacir AM, Levine WN, Bigliani LU, Ahmad CS. Training resources in arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(6):1393-1398.

26. Mauro CS, Jordan SS, Irrgang JJ, Harner CD. Practice patterns for subacromial decompression and rotator cuff repair: an analysis of the American Board of Orthopaedic Surgery database. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(16):1492-1499.

27. Churchill RS, Ghorai JK. Total cost and operating room time comparison of rotator cuff repair techniques at low, intermediate, and high volume centers: mini-open versus all-arthroscopic. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19(5):716-721.

28. O’Neill PJ, Cosgarea AJ, Freedman JA, Queale WS, McFarland EG. Arthroscopic proficiency: a survey of orthopaedic sports medicine fellowship directors and orthopaedic surgery department chairs. Arthroscopy. 2002;18(7):795-800.

29. Guttmann D, Graham RD, MacLennan MJ, Lubowitz JH. Arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: the learning curve. Arthroscopy. 2005;21(4):394-400.