User login

Farewell to Larry Wellikson, MD, MHM

SHM cofounders praise the Society’s outgoing CEO

Setting the table for over 2 decades

I first met Larry in the spring of 1998 after I had made a presentation to the American College of Physicians’ Board of Regents on the Society for Hospital Medicine’s (then the National Association of Inpatient Physicians) new position statement that referral to hospitalists by primary care physicians should be voluntary. At the time, a number of managed care companies around the United States were compelling primary care physicians to use hospitalists to care for their hospitalized patients apparently because they felt hospitalists could do it more efficiently. SHM became the first professional society to voice the position which in turn was broadly endorsed by physician organizations, including the American Medical Association and the ACP.

Larry sought me out, engaged with me, and handed me his business card. He seemed keen on becoming a part of the rapidly accelerating hospitalist movement and, in retrospect, putting his signature on it. He had recently built and exited from a very large and successful independent physician association during the heyday of California managed care and was eager for a new challenge.

Unlike me, who was just a few years out of residency, Larry was at the height of his professional powers, with the right blend of experience on the one hand and energy on the other to take on a project like SHM.

Larry’s first contribution came in the form of facilitating a 2-day strategic planning meeting with the SHM board in the fall of 1998. John Nelson, MD, had moved to Philadelphia for 3 months to establish the operational foundation of SHM and guide SHM’s first staff member, Angela Musial. One of the most notable achievements during that time was a strategic planning board meeting, which largely set the course for SHM’s early years. Larry was a taskmaster, forcing us to make tough choices about what we wanted to accomplish and to establish concrete goals with timelines and milestones. The adult supervision Larry brought was a new and vital thing for us.

There was a lot at stake in ’97, ‘98, and ‘99. The demand for hospitalists across the nation was skyrocketing and there was a strong need for leadership and bold direction. Academics, community-based hospitalists, pediatricians, entrepreneurs, nonphysician hospital team members, heads of organized medicine, and government and industry leaders were just some of the key stakeholders looking for a seat at the HM table. That table would go on to be set for some 2 decades by Larry Wellikson.

From the beginning, many observers remarked that SHM had established an aggressive agenda. There was an unrelenting need to erect a big tent as a home for diverse stakeholders. John and I and the SHM board were doing all we could to continue to build momentum while also leading our local hospitalist groups and trying to maintain a semblance of balance with our young families back home.

It was against this backdrop, in late 1999, while on yet another flight crisscrossing the country to promote HM and SHM, that John; Bob Wachter, MD (who had by that time replaced John and I as SHM president); and I decided we needed a full-time CEO. By that time, each of us had participated in conversations with Larry. We rapidly decided, with buy-in from the board, that we would offer Larry the position. He accepted and became CEO in January 2000.

To list here all of Larry’s accomplishments since taking the helm at SHM would be impossible. Indeed, all that SHM has achieved is closely tied to Larry. Instead, I would like to call out character traits Larry brought to SHM that are now part of SHM’s DNA and a large part of the reason SHM has been so successful over the past 20 years.

Solution oriented. SHM’s culture has always been to take conditions as they are and work to make things better. There is no place for excessively airing grievances and complaining about “what is being done to us.”

Eschewing the status quo. We can do better. There is too much that needs to be done to wait.

Appropriately irreverent of the norms of the medical establishment. Physicians are by nature careful, plodding, considered, cautious, and methodical. The velocity of change in HM called for a different approach in order to be relevant, one better characterized as the move-fast-and-break-things ethos of a Silicon Valley startup.

Bringing diverse stakeholders to the table. A signature move has been to assemble influential people to lay out the issues before setting a course of action.

Strong bias to action. There is a time to analyze and discuss, but all of this ultimately is in service of taking action to achieve a tangible result.

Working to achieve consensus to a point, then moving forward. Considerable resources have been put into bringing stakeholders together, studying problems, and gaining a common understanding of issues. But this has never been at the expense of taking bold action, even if controversial at times.

Involving industry in creative ways to the benefit of patients. SHM pioneered an approach to use resources gained through industry partnerships to perform national scale improvement activities with groups of hospitalist mentor-experts working with local teams to make care more reliable for patients.

Tirelessly connecting to frontline hospitalists. The lifeblood of SHM is frontline hospitalists. Larry has taken the time to develop relationships with as many as possible, often through personally visiting their communities.

Dr. Whitcomb is chief medical officer at Remedy Partners in Darien, Conn., and cofounder and past president of SHM.

Dynamism

By John Nelson, MD, MHM

You probably know a few people with a magnetic personality. Larry Wellikson is the neodymium variety. Boundless energy, confidence that he has the answer or knows exactly where to find it, and ability to instantly recall every conversation he’s had with you, are traits that have energized his years leading SHM and have led countless people to regard him as friend and mentor.

Watch him at the SHM annual conference. There he goes, fast walking to his next commitment while facing backward to complete from a growing distance the conversation with a person he just bumped into along the way. It is like this for Larry from 6 a.m. until midnight. Like Alexander Hamilton, “the man is nonstop.”

Bill Campbell was the “Trillion Dollar Coach” who had his own success as a business leader, but is best known for mentoring Steve Jobs, the Google founders, and many others who went on to become titans of tech. Larry is hospital medicine’s “Coach,” and has inspired and guided the careers of so many clinicians, administrators, and entrepreneurs in hospital medicine and health care more broadly.

The biggest difference between these two highly effective leaders and mentors might be money; SHM has paid him pretty well, but alas, no stock options.

Larry is a great storyteller, and it doesn’t take long for a conversation with him to arrive at the point where he cites the example of how issues faced by someone else have parallels to your situation, the advice he gave that person, and how things turned out. Mostly this advice is about navigating professional life, but he is also happy to share wisdom about parenting, marriage, money, and sports. And most any other topic.

Larry was very accomplished even prior to connecting with SHM. He had a thriving clinical career, and though he left practice long ago he has maintained a close connection with many people he first met when they were his patients. I was surprised years ago when he drove up a new top-of-the-line Lexus – the two-seater with the solid convertible roof that folded into the trunk with the push of a button. I expressed surprise that he’d buy such a swanky car and he explained that a former patient, now long-time friend, was a Lexus distributor and arranged for Larry to drive it away for something like the cost of a Camry.

He also had terrific success forming and leading a large California independent physician association prior to connecting with SHM. Just ask him to show you the magazine with him on the cover and a glowing article detailing his accomplishments. Seriously, ask him, there’s a good chance he’ll have a copy with him.

When Dr. Win Whitcomb and I were trying to figure out how to start a new medical society and position our field to mature into a real specialty we were lucky enough to connect with many health care leaders who we thought could help. Most tended to pat us on the shoulder and say something along the lines of “good luck with your little hobby, now I have to get back to my important work.” But here was Larry with his impressive resume, having served as one of the leaders who crafted the merger of two giant medical societies (ACP and the American Society of Internal Medicine), keenly interested in our tiny new organization, and excited to serve as facilitator for our first strategic planning session.

SHM got a turbocharger when Larry signed on. For me it has felt like speeding down a highway, top down, radio blasting great music, and happy anticipation of what is around the next corner. I have never been disappointed, and certainly don’t plan to get out of Larry’s car just because he’s retiring as CEO.

Dr. Nelson is cofounder and past president of SHM and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants in La Quinta, Calif.

SHM cofounders praise the Society’s outgoing CEO

SHM cofounders praise the Society’s outgoing CEO

Setting the table for over 2 decades

I first met Larry in the spring of 1998 after I had made a presentation to the American College of Physicians’ Board of Regents on the Society for Hospital Medicine’s (then the National Association of Inpatient Physicians) new position statement that referral to hospitalists by primary care physicians should be voluntary. At the time, a number of managed care companies around the United States were compelling primary care physicians to use hospitalists to care for their hospitalized patients apparently because they felt hospitalists could do it more efficiently. SHM became the first professional society to voice the position which in turn was broadly endorsed by physician organizations, including the American Medical Association and the ACP.

Larry sought me out, engaged with me, and handed me his business card. He seemed keen on becoming a part of the rapidly accelerating hospitalist movement and, in retrospect, putting his signature on it. He had recently built and exited from a very large and successful independent physician association during the heyday of California managed care and was eager for a new challenge.

Unlike me, who was just a few years out of residency, Larry was at the height of his professional powers, with the right blend of experience on the one hand and energy on the other to take on a project like SHM.

Larry’s first contribution came in the form of facilitating a 2-day strategic planning meeting with the SHM board in the fall of 1998. John Nelson, MD, had moved to Philadelphia for 3 months to establish the operational foundation of SHM and guide SHM’s first staff member, Angela Musial. One of the most notable achievements during that time was a strategic planning board meeting, which largely set the course for SHM’s early years. Larry was a taskmaster, forcing us to make tough choices about what we wanted to accomplish and to establish concrete goals with timelines and milestones. The adult supervision Larry brought was a new and vital thing for us.

There was a lot at stake in ’97, ‘98, and ‘99. The demand for hospitalists across the nation was skyrocketing and there was a strong need for leadership and bold direction. Academics, community-based hospitalists, pediatricians, entrepreneurs, nonphysician hospital team members, heads of organized medicine, and government and industry leaders were just some of the key stakeholders looking for a seat at the HM table. That table would go on to be set for some 2 decades by Larry Wellikson.

From the beginning, many observers remarked that SHM had established an aggressive agenda. There was an unrelenting need to erect a big tent as a home for diverse stakeholders. John and I and the SHM board were doing all we could to continue to build momentum while also leading our local hospitalist groups and trying to maintain a semblance of balance with our young families back home.

It was against this backdrop, in late 1999, while on yet another flight crisscrossing the country to promote HM and SHM, that John; Bob Wachter, MD (who had by that time replaced John and I as SHM president); and I decided we needed a full-time CEO. By that time, each of us had participated in conversations with Larry. We rapidly decided, with buy-in from the board, that we would offer Larry the position. He accepted and became CEO in January 2000.

To list here all of Larry’s accomplishments since taking the helm at SHM would be impossible. Indeed, all that SHM has achieved is closely tied to Larry. Instead, I would like to call out character traits Larry brought to SHM that are now part of SHM’s DNA and a large part of the reason SHM has been so successful over the past 20 years.

Solution oriented. SHM’s culture has always been to take conditions as they are and work to make things better. There is no place for excessively airing grievances and complaining about “what is being done to us.”

Eschewing the status quo. We can do better. There is too much that needs to be done to wait.

Appropriately irreverent of the norms of the medical establishment. Physicians are by nature careful, plodding, considered, cautious, and methodical. The velocity of change in HM called for a different approach in order to be relevant, one better characterized as the move-fast-and-break-things ethos of a Silicon Valley startup.

Bringing diverse stakeholders to the table. A signature move has been to assemble influential people to lay out the issues before setting a course of action.

Strong bias to action. There is a time to analyze and discuss, but all of this ultimately is in service of taking action to achieve a tangible result.

Working to achieve consensus to a point, then moving forward. Considerable resources have been put into bringing stakeholders together, studying problems, and gaining a common understanding of issues. But this has never been at the expense of taking bold action, even if controversial at times.

Involving industry in creative ways to the benefit of patients. SHM pioneered an approach to use resources gained through industry partnerships to perform national scale improvement activities with groups of hospitalist mentor-experts working with local teams to make care more reliable for patients.

Tirelessly connecting to frontline hospitalists. The lifeblood of SHM is frontline hospitalists. Larry has taken the time to develop relationships with as many as possible, often through personally visiting their communities.

Dr. Whitcomb is chief medical officer at Remedy Partners in Darien, Conn., and cofounder and past president of SHM.

Dynamism

By John Nelson, MD, MHM

You probably know a few people with a magnetic personality. Larry Wellikson is the neodymium variety. Boundless energy, confidence that he has the answer or knows exactly where to find it, and ability to instantly recall every conversation he’s had with you, are traits that have energized his years leading SHM and have led countless people to regard him as friend and mentor.

Watch him at the SHM annual conference. There he goes, fast walking to his next commitment while facing backward to complete from a growing distance the conversation with a person he just bumped into along the way. It is like this for Larry from 6 a.m. until midnight. Like Alexander Hamilton, “the man is nonstop.”

Bill Campbell was the “Trillion Dollar Coach” who had his own success as a business leader, but is best known for mentoring Steve Jobs, the Google founders, and many others who went on to become titans of tech. Larry is hospital medicine’s “Coach,” and has inspired and guided the careers of so many clinicians, administrators, and entrepreneurs in hospital medicine and health care more broadly.

The biggest difference between these two highly effective leaders and mentors might be money; SHM has paid him pretty well, but alas, no stock options.

Larry is a great storyteller, and it doesn’t take long for a conversation with him to arrive at the point where he cites the example of how issues faced by someone else have parallels to your situation, the advice he gave that person, and how things turned out. Mostly this advice is about navigating professional life, but he is also happy to share wisdom about parenting, marriage, money, and sports. And most any other topic.

Larry was very accomplished even prior to connecting with SHM. He had a thriving clinical career, and though he left practice long ago he has maintained a close connection with many people he first met when they were his patients. I was surprised years ago when he drove up a new top-of-the-line Lexus – the two-seater with the solid convertible roof that folded into the trunk with the push of a button. I expressed surprise that he’d buy such a swanky car and he explained that a former patient, now long-time friend, was a Lexus distributor and arranged for Larry to drive it away for something like the cost of a Camry.

He also had terrific success forming and leading a large California independent physician association prior to connecting with SHM. Just ask him to show you the magazine with him on the cover and a glowing article detailing his accomplishments. Seriously, ask him, there’s a good chance he’ll have a copy with him.

When Dr. Win Whitcomb and I were trying to figure out how to start a new medical society and position our field to mature into a real specialty we were lucky enough to connect with many health care leaders who we thought could help. Most tended to pat us on the shoulder and say something along the lines of “good luck with your little hobby, now I have to get back to my important work.” But here was Larry with his impressive resume, having served as one of the leaders who crafted the merger of two giant medical societies (ACP and the American Society of Internal Medicine), keenly interested in our tiny new organization, and excited to serve as facilitator for our first strategic planning session.

SHM got a turbocharger when Larry signed on. For me it has felt like speeding down a highway, top down, radio blasting great music, and happy anticipation of what is around the next corner. I have never been disappointed, and certainly don’t plan to get out of Larry’s car just because he’s retiring as CEO.

Dr. Nelson is cofounder and past president of SHM and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants in La Quinta, Calif.

Setting the table for over 2 decades

I first met Larry in the spring of 1998 after I had made a presentation to the American College of Physicians’ Board of Regents on the Society for Hospital Medicine’s (then the National Association of Inpatient Physicians) new position statement that referral to hospitalists by primary care physicians should be voluntary. At the time, a number of managed care companies around the United States were compelling primary care physicians to use hospitalists to care for their hospitalized patients apparently because they felt hospitalists could do it more efficiently. SHM became the first professional society to voice the position which in turn was broadly endorsed by physician organizations, including the American Medical Association and the ACP.

Larry sought me out, engaged with me, and handed me his business card. He seemed keen on becoming a part of the rapidly accelerating hospitalist movement and, in retrospect, putting his signature on it. He had recently built and exited from a very large and successful independent physician association during the heyday of California managed care and was eager for a new challenge.

Unlike me, who was just a few years out of residency, Larry was at the height of his professional powers, with the right blend of experience on the one hand and energy on the other to take on a project like SHM.

Larry’s first contribution came in the form of facilitating a 2-day strategic planning meeting with the SHM board in the fall of 1998. John Nelson, MD, had moved to Philadelphia for 3 months to establish the operational foundation of SHM and guide SHM’s first staff member, Angela Musial. One of the most notable achievements during that time was a strategic planning board meeting, which largely set the course for SHM’s early years. Larry was a taskmaster, forcing us to make tough choices about what we wanted to accomplish and to establish concrete goals with timelines and milestones. The adult supervision Larry brought was a new and vital thing for us.

There was a lot at stake in ’97, ‘98, and ‘99. The demand for hospitalists across the nation was skyrocketing and there was a strong need for leadership and bold direction. Academics, community-based hospitalists, pediatricians, entrepreneurs, nonphysician hospital team members, heads of organized medicine, and government and industry leaders were just some of the key stakeholders looking for a seat at the HM table. That table would go on to be set for some 2 decades by Larry Wellikson.

From the beginning, many observers remarked that SHM had established an aggressive agenda. There was an unrelenting need to erect a big tent as a home for diverse stakeholders. John and I and the SHM board were doing all we could to continue to build momentum while also leading our local hospitalist groups and trying to maintain a semblance of balance with our young families back home.

It was against this backdrop, in late 1999, while on yet another flight crisscrossing the country to promote HM and SHM, that John; Bob Wachter, MD (who had by that time replaced John and I as SHM president); and I decided we needed a full-time CEO. By that time, each of us had participated in conversations with Larry. We rapidly decided, with buy-in from the board, that we would offer Larry the position. He accepted and became CEO in January 2000.

To list here all of Larry’s accomplishments since taking the helm at SHM would be impossible. Indeed, all that SHM has achieved is closely tied to Larry. Instead, I would like to call out character traits Larry brought to SHM that are now part of SHM’s DNA and a large part of the reason SHM has been so successful over the past 20 years.

Solution oriented. SHM’s culture has always been to take conditions as they are and work to make things better. There is no place for excessively airing grievances and complaining about “what is being done to us.”

Eschewing the status quo. We can do better. There is too much that needs to be done to wait.

Appropriately irreverent of the norms of the medical establishment. Physicians are by nature careful, plodding, considered, cautious, and methodical. The velocity of change in HM called for a different approach in order to be relevant, one better characterized as the move-fast-and-break-things ethos of a Silicon Valley startup.

Bringing diverse stakeholders to the table. A signature move has been to assemble influential people to lay out the issues before setting a course of action.

Strong bias to action. There is a time to analyze and discuss, but all of this ultimately is in service of taking action to achieve a tangible result.

Working to achieve consensus to a point, then moving forward. Considerable resources have been put into bringing stakeholders together, studying problems, and gaining a common understanding of issues. But this has never been at the expense of taking bold action, even if controversial at times.

Involving industry in creative ways to the benefit of patients. SHM pioneered an approach to use resources gained through industry partnerships to perform national scale improvement activities with groups of hospitalist mentor-experts working with local teams to make care more reliable for patients.

Tirelessly connecting to frontline hospitalists. The lifeblood of SHM is frontline hospitalists. Larry has taken the time to develop relationships with as many as possible, often through personally visiting their communities.

Dr. Whitcomb is chief medical officer at Remedy Partners in Darien, Conn., and cofounder and past president of SHM.

Dynamism

By John Nelson, MD, MHM

You probably know a few people with a magnetic personality. Larry Wellikson is the neodymium variety. Boundless energy, confidence that he has the answer or knows exactly where to find it, and ability to instantly recall every conversation he’s had with you, are traits that have energized his years leading SHM and have led countless people to regard him as friend and mentor.

Watch him at the SHM annual conference. There he goes, fast walking to his next commitment while facing backward to complete from a growing distance the conversation with a person he just bumped into along the way. It is like this for Larry from 6 a.m. until midnight. Like Alexander Hamilton, “the man is nonstop.”

Bill Campbell was the “Trillion Dollar Coach” who had his own success as a business leader, but is best known for mentoring Steve Jobs, the Google founders, and many others who went on to become titans of tech. Larry is hospital medicine’s “Coach,” and has inspired and guided the careers of so many clinicians, administrators, and entrepreneurs in hospital medicine and health care more broadly.

The biggest difference between these two highly effective leaders and mentors might be money; SHM has paid him pretty well, but alas, no stock options.

Larry is a great storyteller, and it doesn’t take long for a conversation with him to arrive at the point where he cites the example of how issues faced by someone else have parallels to your situation, the advice he gave that person, and how things turned out. Mostly this advice is about navigating professional life, but he is also happy to share wisdom about parenting, marriage, money, and sports. And most any other topic.

Larry was very accomplished even prior to connecting with SHM. He had a thriving clinical career, and though he left practice long ago he has maintained a close connection with many people he first met when they were his patients. I was surprised years ago when he drove up a new top-of-the-line Lexus – the two-seater with the solid convertible roof that folded into the trunk with the push of a button. I expressed surprise that he’d buy such a swanky car and he explained that a former patient, now long-time friend, was a Lexus distributor and arranged for Larry to drive it away for something like the cost of a Camry.

He also had terrific success forming and leading a large California independent physician association prior to connecting with SHM. Just ask him to show you the magazine with him on the cover and a glowing article detailing his accomplishments. Seriously, ask him, there’s a good chance he’ll have a copy with him.

When Dr. Win Whitcomb and I were trying to figure out how to start a new medical society and position our field to mature into a real specialty we were lucky enough to connect with many health care leaders who we thought could help. Most tended to pat us on the shoulder and say something along the lines of “good luck with your little hobby, now I have to get back to my important work.” But here was Larry with his impressive resume, having served as one of the leaders who crafted the merger of two giant medical societies (ACP and the American Society of Internal Medicine), keenly interested in our tiny new organization, and excited to serve as facilitator for our first strategic planning session.

SHM got a turbocharger when Larry signed on. For me it has felt like speeding down a highway, top down, radio blasting great music, and happy anticipation of what is around the next corner. I have never been disappointed, and certainly don’t plan to get out of Larry’s car just because he’s retiring as CEO.

Dr. Nelson is cofounder and past president of SHM and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants in La Quinta, Calif.

Understanding the new CMS bundle model

Hospitalists have been among the highest-volume participants in Medicare’s Bundled Payments for Care Improvement (BPCI) demonstration model, initiating over 200,000 episodes representing $4.7 billion in spending since the model began.1 On Jan. 9, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services announced BPCI’s follow-on model, “BPCI Advanced.”2

BPCI launched in October 2013 and sunsets at the end of Q3 2018. BPCI Advanced starts immediately upon conclusion of BPCI (Q4 2018) and is slated to finish at year-end 2023.

CMS intends for the program to qualify as an Advanced Alternative Payment Model (APM). As BPCI Advanced focuses on episodes of care involving an inpatient stay (It also includes three outpatient episodes.) and the subsequent 90-day recovery period, it represents the first large-scale opportunity for hospitalists to meet criteria for Advanced APM participation. Qualifying for the Advanced APM track of the Quality Payment Program – which involves meeting patient volume or payment thresholds3 – comes with a 5% lump-sum bonus based on Medicare Part B fees and avoids exposure to penalties and reporting requirements of the Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS).

Key program features

Acute care hospitals and physician groups may initiate episodes under BPCI Advanced, assuming financial risk under the model. Similar to its predecessor, BPCI Advanced assigns a target price based on past claims payments associated with the “episode initiator.”

During the performance period, if the initiator can beat the price in the aggregate for its bundles, it can keep the difference, and if it comes in over the price, it must pay the difference back to Medicare. Medicare discounts the target price by 3%, effectively paying itself that amount. After that, there is no sharing of savings with Medicare, as opposed to the permanent ACO programs, where there is sharing after the ACO meets the minimum savings rate.

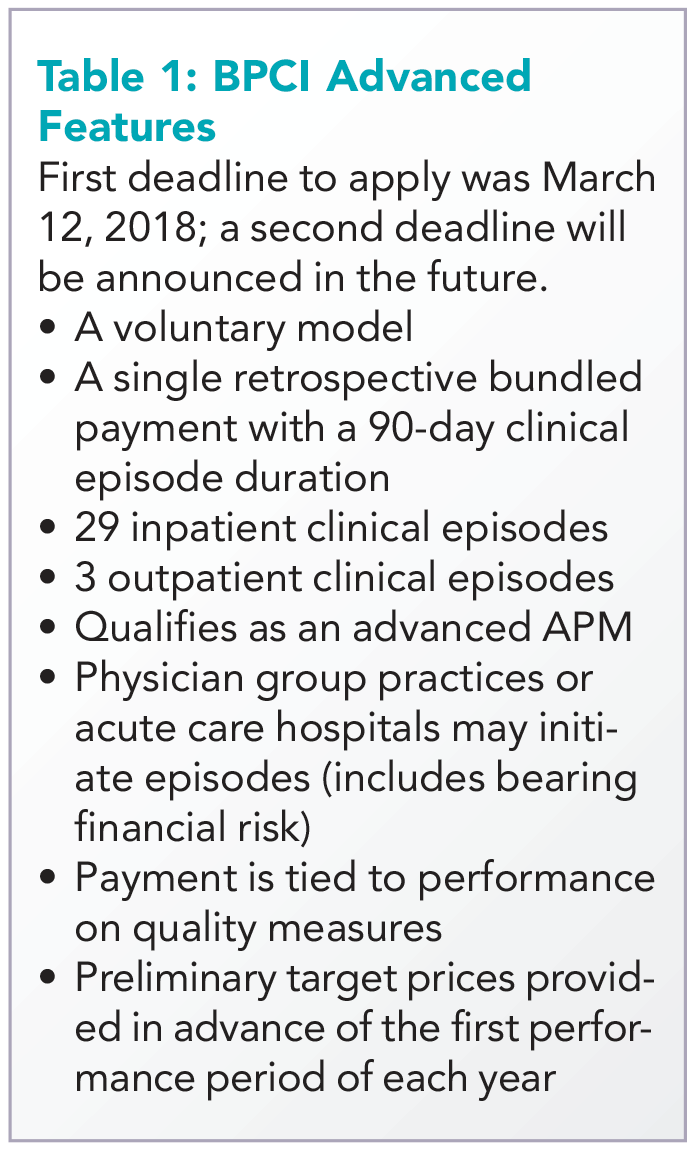

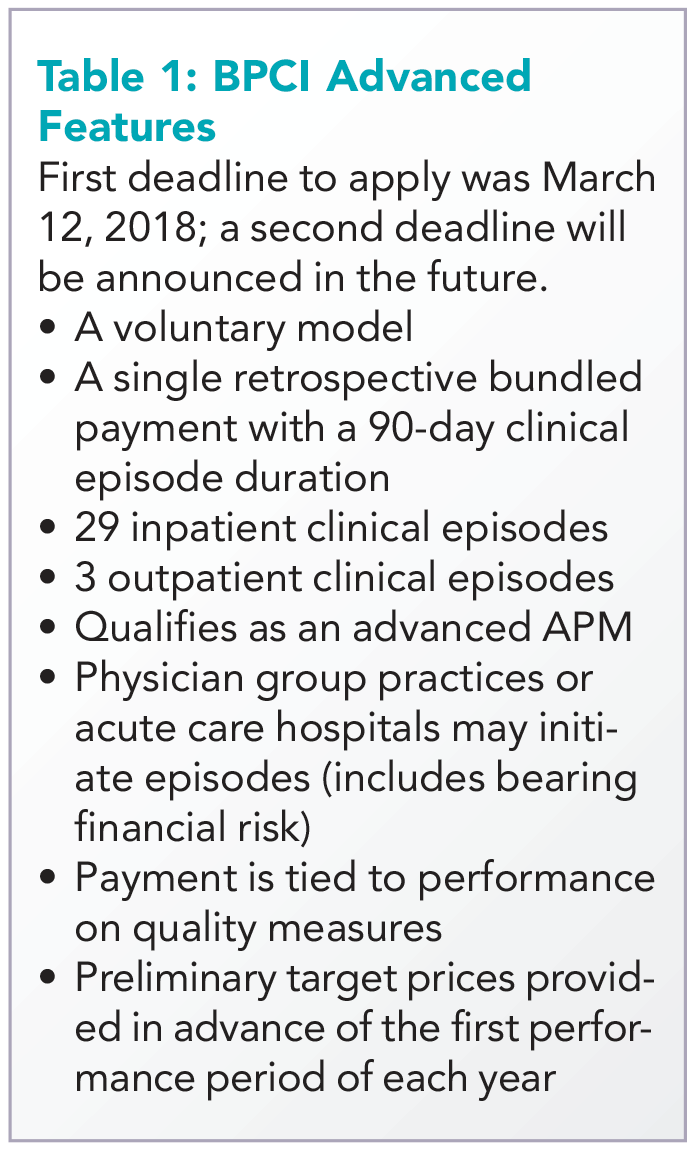

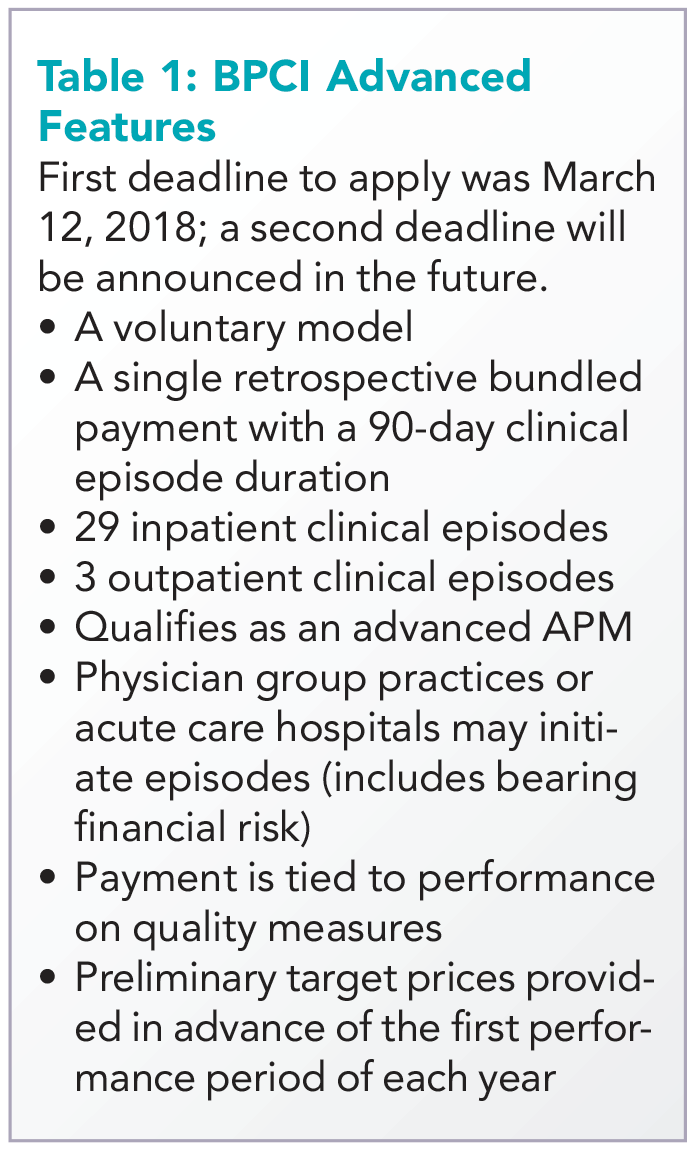

The program allows physician groups and hospital initiators to go it alone or to work with a “convener,” which may share risk and reward with initiators, and may provide software, analytics, networks of high-performing providers like nursing facilities, and knowledge of specific care redesign approaches to enable program success. See Table 1 for a listing of other notable features of BPCI Advanced.

Quality measures

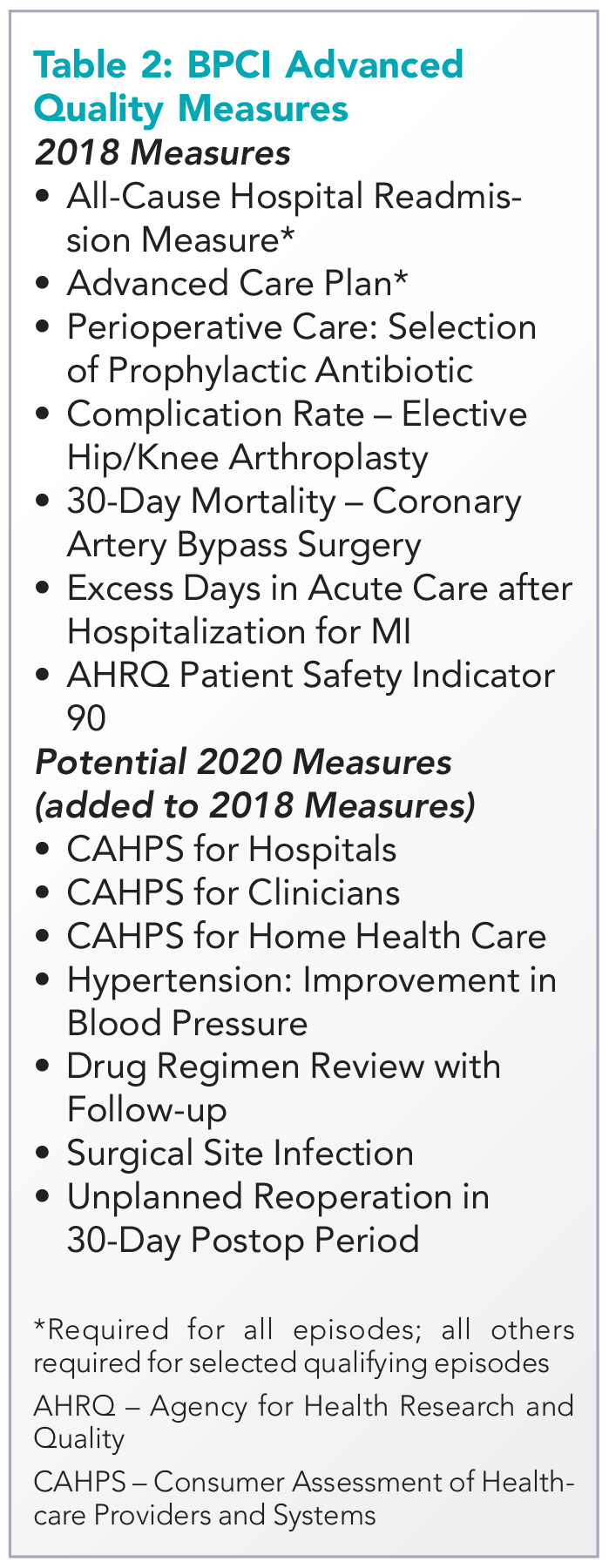

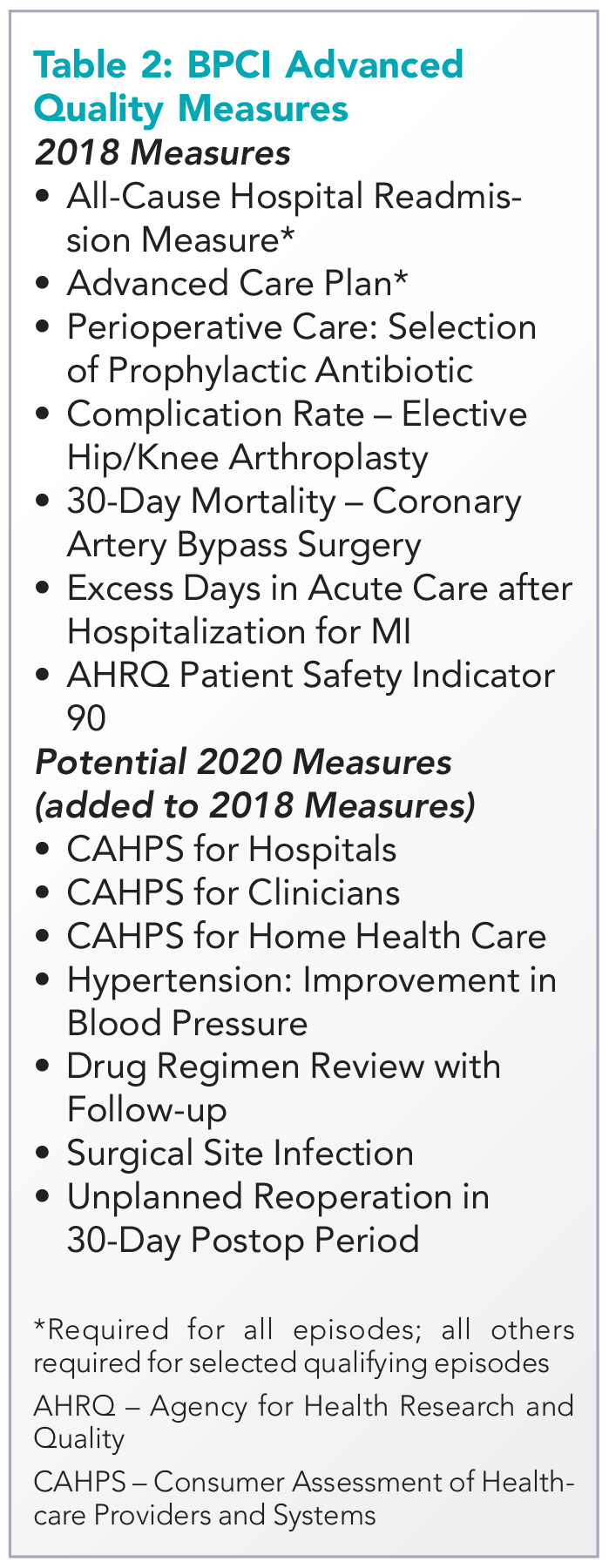

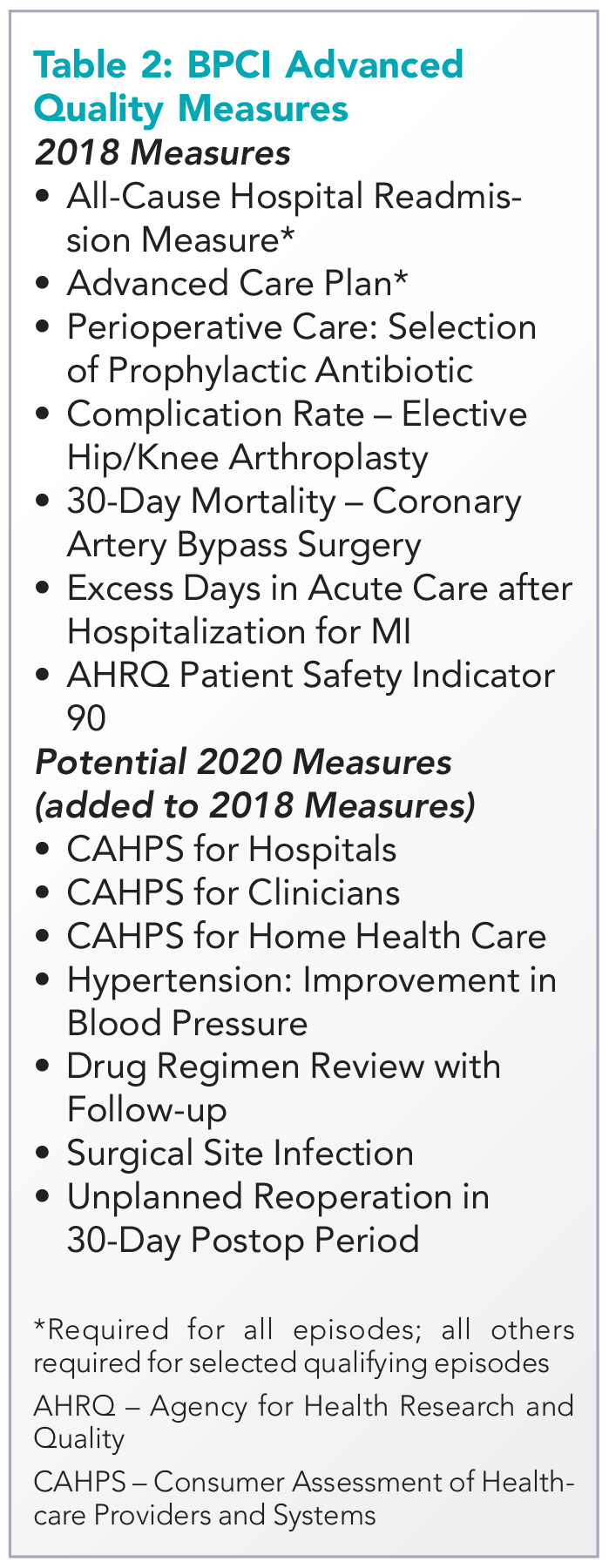

BPCI Advanced qualifies as an Advanced APM in part because payment is tied to performance on a set of quality measures (see Table 2). There are two measures applied to all episodes: all-cause hospital readmissions and advance care plan. These are notable because hospitalists may be especially focused on improvement activities in these areas.

While the advance care plan measure refers to a process reflected by record documentation and is therefore directly under the control of hospitalists, readmissions – and most of the other measures – require a team approach. Because the outcome measures are risk adjusted, accurate and complete clinical documentation is crucial, as it drives how risk is adjusted. Of note, all the 2018 measures, collected directly through claims, will place no additional administrative burden for collection on providers.

Two ways for hospitalists to participate

Hospitalist groups – whether independent or employed – may be episode initiators in BPCI Advanced. In this case, any episodes in which the group participates that carry the name of a member of the hospitalist group in the “Attending Provider” field on the hospital bill claim form to Medicare (and the associated carrier claim) are attributed to that member’s physician group.

For example, if the group has chosen heart failure as an episode in which to participate at the program’s outset, a hospitalization is assigned the heart failure DRG (diagnosis-related group) and a group member is the Attending Provider on the claim form (and submits a claim for the physician services), then the episode is attributed to that group. This means that the group is responsible for payments represented by Medicare Part A and Part B claims (with a few exclusions like trauma and cancer) against the target price for the initial hospitalization and subsequent 90-day period. In practice, hospitalists are rewarded for actions aimed at optimizing location after discharge,4 avoiding readmissions, choosing efficient nursing facilities, and helping patients to maximize functional status.

The other way hospitalists may participate is through an agreement to share in savings with a hospital or physician group episode initiator. This requires hospitalist individuals or groups to enter into a contract with the initiator that meets certain program requirements – for example, report quality measures, engage in care redesign, use certified EHR technology (hospital-based clinicians automatically fulfill this criterion).

If there is broad participation, BPCI Advanced could represent a key milestone for hospitalists, as they seek to be recognized for the value they confer to the system as a whole instead of simply their professional billings. While there are legitimate concerns about the effect MIPS may have on health care value and the complexity of participation in APMs, barring a repeal of the law that created them, hospitalists now have the chance to extend their influence within and outside the hospital’s four walls and be more fairly rewarded for it.

Dr. Whitcomb is chief medical officer at Remedy Partners in Darien, Conn., and cofounder and past president of the Society of Hospital Medicine. Contact him at wfwhit@comcast.net. Disclosure: The author’s employer, Remedy Partners, is an Awardee Convener for the BPCI initiative and intends to apply as a Convener in BPCI Advanced.

References

1. Based on BPCI awardee convener Remedy Partners claims analysis.

2. https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/bpci-advanced.

3. https://qpp.cms.gov/apms/overview.

4. Whitcomb W. Choosing location after discharge wisely. The-hospitalist.org. 2018 Jan 3. Digital edition. Accessed Jan 13, 2018.

Hospitalists have been among the highest-volume participants in Medicare’s Bundled Payments for Care Improvement (BPCI) demonstration model, initiating over 200,000 episodes representing $4.7 billion in spending since the model began.1 On Jan. 9, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services announced BPCI’s follow-on model, “BPCI Advanced.”2

BPCI launched in October 2013 and sunsets at the end of Q3 2018. BPCI Advanced starts immediately upon conclusion of BPCI (Q4 2018) and is slated to finish at year-end 2023.

CMS intends for the program to qualify as an Advanced Alternative Payment Model (APM). As BPCI Advanced focuses on episodes of care involving an inpatient stay (It also includes three outpatient episodes.) and the subsequent 90-day recovery period, it represents the first large-scale opportunity for hospitalists to meet criteria for Advanced APM participation. Qualifying for the Advanced APM track of the Quality Payment Program – which involves meeting patient volume or payment thresholds3 – comes with a 5% lump-sum bonus based on Medicare Part B fees and avoids exposure to penalties and reporting requirements of the Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS).

Key program features

Acute care hospitals and physician groups may initiate episodes under BPCI Advanced, assuming financial risk under the model. Similar to its predecessor, BPCI Advanced assigns a target price based on past claims payments associated with the “episode initiator.”

During the performance period, if the initiator can beat the price in the aggregate for its bundles, it can keep the difference, and if it comes in over the price, it must pay the difference back to Medicare. Medicare discounts the target price by 3%, effectively paying itself that amount. After that, there is no sharing of savings with Medicare, as opposed to the permanent ACO programs, where there is sharing after the ACO meets the minimum savings rate.

The program allows physician groups and hospital initiators to go it alone or to work with a “convener,” which may share risk and reward with initiators, and may provide software, analytics, networks of high-performing providers like nursing facilities, and knowledge of specific care redesign approaches to enable program success. See Table 1 for a listing of other notable features of BPCI Advanced.

Quality measures

BPCI Advanced qualifies as an Advanced APM in part because payment is tied to performance on a set of quality measures (see Table 2). There are two measures applied to all episodes: all-cause hospital readmissions and advance care plan. These are notable because hospitalists may be especially focused on improvement activities in these areas.

While the advance care plan measure refers to a process reflected by record documentation and is therefore directly under the control of hospitalists, readmissions – and most of the other measures – require a team approach. Because the outcome measures are risk adjusted, accurate and complete clinical documentation is crucial, as it drives how risk is adjusted. Of note, all the 2018 measures, collected directly through claims, will place no additional administrative burden for collection on providers.

Two ways for hospitalists to participate

Hospitalist groups – whether independent or employed – may be episode initiators in BPCI Advanced. In this case, any episodes in which the group participates that carry the name of a member of the hospitalist group in the “Attending Provider” field on the hospital bill claim form to Medicare (and the associated carrier claim) are attributed to that member’s physician group.

For example, if the group has chosen heart failure as an episode in which to participate at the program’s outset, a hospitalization is assigned the heart failure DRG (diagnosis-related group) and a group member is the Attending Provider on the claim form (and submits a claim for the physician services), then the episode is attributed to that group. This means that the group is responsible for payments represented by Medicare Part A and Part B claims (with a few exclusions like trauma and cancer) against the target price for the initial hospitalization and subsequent 90-day period. In practice, hospitalists are rewarded for actions aimed at optimizing location after discharge,4 avoiding readmissions, choosing efficient nursing facilities, and helping patients to maximize functional status.

The other way hospitalists may participate is through an agreement to share in savings with a hospital or physician group episode initiator. This requires hospitalist individuals or groups to enter into a contract with the initiator that meets certain program requirements – for example, report quality measures, engage in care redesign, use certified EHR technology (hospital-based clinicians automatically fulfill this criterion).

If there is broad participation, BPCI Advanced could represent a key milestone for hospitalists, as they seek to be recognized for the value they confer to the system as a whole instead of simply their professional billings. While there are legitimate concerns about the effect MIPS may have on health care value and the complexity of participation in APMs, barring a repeal of the law that created them, hospitalists now have the chance to extend their influence within and outside the hospital’s four walls and be more fairly rewarded for it.

Dr. Whitcomb is chief medical officer at Remedy Partners in Darien, Conn., and cofounder and past president of the Society of Hospital Medicine. Contact him at wfwhit@comcast.net. Disclosure: The author’s employer, Remedy Partners, is an Awardee Convener for the BPCI initiative and intends to apply as a Convener in BPCI Advanced.

References

1. Based on BPCI awardee convener Remedy Partners claims analysis.

2. https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/bpci-advanced.

3. https://qpp.cms.gov/apms/overview.

4. Whitcomb W. Choosing location after discharge wisely. The-hospitalist.org. 2018 Jan 3. Digital edition. Accessed Jan 13, 2018.

Hospitalists have been among the highest-volume participants in Medicare’s Bundled Payments for Care Improvement (BPCI) demonstration model, initiating over 200,000 episodes representing $4.7 billion in spending since the model began.1 On Jan. 9, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services announced BPCI’s follow-on model, “BPCI Advanced.”2

BPCI launched in October 2013 and sunsets at the end of Q3 2018. BPCI Advanced starts immediately upon conclusion of BPCI (Q4 2018) and is slated to finish at year-end 2023.

CMS intends for the program to qualify as an Advanced Alternative Payment Model (APM). As BPCI Advanced focuses on episodes of care involving an inpatient stay (It also includes three outpatient episodes.) and the subsequent 90-day recovery period, it represents the first large-scale opportunity for hospitalists to meet criteria for Advanced APM participation. Qualifying for the Advanced APM track of the Quality Payment Program – which involves meeting patient volume or payment thresholds3 – comes with a 5% lump-sum bonus based on Medicare Part B fees and avoids exposure to penalties and reporting requirements of the Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS).

Key program features

Acute care hospitals and physician groups may initiate episodes under BPCI Advanced, assuming financial risk under the model. Similar to its predecessor, BPCI Advanced assigns a target price based on past claims payments associated with the “episode initiator.”

During the performance period, if the initiator can beat the price in the aggregate for its bundles, it can keep the difference, and if it comes in over the price, it must pay the difference back to Medicare. Medicare discounts the target price by 3%, effectively paying itself that amount. After that, there is no sharing of savings with Medicare, as opposed to the permanent ACO programs, where there is sharing after the ACO meets the minimum savings rate.

The program allows physician groups and hospital initiators to go it alone or to work with a “convener,” which may share risk and reward with initiators, and may provide software, analytics, networks of high-performing providers like nursing facilities, and knowledge of specific care redesign approaches to enable program success. See Table 1 for a listing of other notable features of BPCI Advanced.

Quality measures

BPCI Advanced qualifies as an Advanced APM in part because payment is tied to performance on a set of quality measures (see Table 2). There are two measures applied to all episodes: all-cause hospital readmissions and advance care plan. These are notable because hospitalists may be especially focused on improvement activities in these areas.

While the advance care plan measure refers to a process reflected by record documentation and is therefore directly under the control of hospitalists, readmissions – and most of the other measures – require a team approach. Because the outcome measures are risk adjusted, accurate and complete clinical documentation is crucial, as it drives how risk is adjusted. Of note, all the 2018 measures, collected directly through claims, will place no additional administrative burden for collection on providers.

Two ways for hospitalists to participate

Hospitalist groups – whether independent or employed – may be episode initiators in BPCI Advanced. In this case, any episodes in which the group participates that carry the name of a member of the hospitalist group in the “Attending Provider” field on the hospital bill claim form to Medicare (and the associated carrier claim) are attributed to that member’s physician group.

For example, if the group has chosen heart failure as an episode in which to participate at the program’s outset, a hospitalization is assigned the heart failure DRG (diagnosis-related group) and a group member is the Attending Provider on the claim form (and submits a claim for the physician services), then the episode is attributed to that group. This means that the group is responsible for payments represented by Medicare Part A and Part B claims (with a few exclusions like trauma and cancer) against the target price for the initial hospitalization and subsequent 90-day period. In practice, hospitalists are rewarded for actions aimed at optimizing location after discharge,4 avoiding readmissions, choosing efficient nursing facilities, and helping patients to maximize functional status.

The other way hospitalists may participate is through an agreement to share in savings with a hospital or physician group episode initiator. This requires hospitalist individuals or groups to enter into a contract with the initiator that meets certain program requirements – for example, report quality measures, engage in care redesign, use certified EHR technology (hospital-based clinicians automatically fulfill this criterion).

If there is broad participation, BPCI Advanced could represent a key milestone for hospitalists, as they seek to be recognized for the value they confer to the system as a whole instead of simply their professional billings. While there are legitimate concerns about the effect MIPS may have on health care value and the complexity of participation in APMs, barring a repeal of the law that created them, hospitalists now have the chance to extend their influence within and outside the hospital’s four walls and be more fairly rewarded for it.

Dr. Whitcomb is chief medical officer at Remedy Partners in Darien, Conn., and cofounder and past president of the Society of Hospital Medicine. Contact him at wfwhit@comcast.net. Disclosure: The author’s employer, Remedy Partners, is an Awardee Convener for the BPCI initiative and intends to apply as a Convener in BPCI Advanced.

References

1. Based on BPCI awardee convener Remedy Partners claims analysis.

2. https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/bpci-advanced.

3. https://qpp.cms.gov/apms/overview.

4. Whitcomb W. Choosing location after discharge wisely. The-hospitalist.org. 2018 Jan 3. Digital edition. Accessed Jan 13, 2018.

How’s your postacute network doing?

By now, nearly all hospitals are developing networks of postacute facilities for some or all of their patients, such as those in ACOs, bundled payments, or other value-based programs. Commonly referred to as preferred providers, performance networks, narrow networks, or similar, these networks of skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) and other entities that provide postacute care (like home health agencies) are usually chosen because they have demonstrated that they provide high quality, cost-effective care for patients after they leave the hospital.

While case managers are often the ones who counsel patients and caregivers on the details of the network, hospitalists should have at least a high-level grasp of which facilities are on the list and what the network selection criteria are. I would argue that hospitalists should lead the discussion with patients on postacute facility selection as it relates to which facilities are in the network and why going to a network facility is advantageous. Why? Because as hospitalist practices begin to share clinical and financial risk for patients, or at least become eligible to share in savings as MACRA encourages, they will have a vested interest in network facilities’ performance.

Postacute care network selection criteria

There is a range of criteria – usually incorporating measures of quality and efficiency – for including providers like SNFs in networks. In terms of quality, criteria can include physician/provider availability, star ratings on Nursing Home Compare, care transitions measures, Department of Public Health inspection survey scores, Joint Commission accreditation, etc.

A few caveats regarding specific selection criteria:

Star ratings on Nursing Home Compare

These are derived from nursing staffing ratios, health inspections, and 16 quality measures. More than half of the quality measures pertain to long-stay residents who typically are not in the ACO or bundled payment program for which the network was created (these are usually short-stay patients).

SNF length of stay

High readmission rates from a SNF can actually lower its length of stay, so including “balancing” measures such as readmissions should be considered.

What about patient choice?

Narrow postacute networks are not only becoming the norm, but there is also broad recognition from CMS, MedPAC, and industry leaders that value-based payment programs require such networks to succeed. That said, case managers and other discharge planners may still resist networks on the grounds that they might be perceived as restricting patient choice. One approach to balancing differing views on patient choice is to give patients the traditional longer list of available postacute providers, and also furnish the shorter network list accompanied by an explanation of why certain SNFs are in the network. Thankfully, as ACOs and bundles become widespread, resistance to narrow networks is dying down.

What role should hospitalists play in network referrals?

High functioning hospitalist practices should lead the discussion with patients and the health care team on referrals to network SNFs. Why? Patients are looking for their doctors to guide them on such decisions. Only if the physician opts not to have the discussion will patients look to the case manager for direction on which postacute facility to choose. A better option still would be for the hospitalists to partner with case managers to have the conversation with patients. In such a scenario, the hospitalist can begin the discussion and cover the major points, and the case manager can follow with more detailed information. For less mature hospitalist practices, the case manager can play a larger role in the discussion. In any case, as value-based models become ubiquitous, and shared savings become a driver of hospitalist revenue, hospitalists’ knowledge of and active participation in conversations around narrow networks and referrals will be necessary.

Dr. Whitcomb is chief medical officer at Remedy Partners in Darien, Conn. He is a cofounder and past president of SHM.

By now, nearly all hospitals are developing networks of postacute facilities for some or all of their patients, such as those in ACOs, bundled payments, or other value-based programs. Commonly referred to as preferred providers, performance networks, narrow networks, or similar, these networks of skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) and other entities that provide postacute care (like home health agencies) are usually chosen because they have demonstrated that they provide high quality, cost-effective care for patients after they leave the hospital.

While case managers are often the ones who counsel patients and caregivers on the details of the network, hospitalists should have at least a high-level grasp of which facilities are on the list and what the network selection criteria are. I would argue that hospitalists should lead the discussion with patients on postacute facility selection as it relates to which facilities are in the network and why going to a network facility is advantageous. Why? Because as hospitalist practices begin to share clinical and financial risk for patients, or at least become eligible to share in savings as MACRA encourages, they will have a vested interest in network facilities’ performance.

Postacute care network selection criteria

There is a range of criteria – usually incorporating measures of quality and efficiency – for including providers like SNFs in networks. In terms of quality, criteria can include physician/provider availability, star ratings on Nursing Home Compare, care transitions measures, Department of Public Health inspection survey scores, Joint Commission accreditation, etc.

A few caveats regarding specific selection criteria:

Star ratings on Nursing Home Compare

These are derived from nursing staffing ratios, health inspections, and 16 quality measures. More than half of the quality measures pertain to long-stay residents who typically are not in the ACO or bundled payment program for which the network was created (these are usually short-stay patients).

SNF length of stay

High readmission rates from a SNF can actually lower its length of stay, so including “balancing” measures such as readmissions should be considered.

What about patient choice?

Narrow postacute networks are not only becoming the norm, but there is also broad recognition from CMS, MedPAC, and industry leaders that value-based payment programs require such networks to succeed. That said, case managers and other discharge planners may still resist networks on the grounds that they might be perceived as restricting patient choice. One approach to balancing differing views on patient choice is to give patients the traditional longer list of available postacute providers, and also furnish the shorter network list accompanied by an explanation of why certain SNFs are in the network. Thankfully, as ACOs and bundles become widespread, resistance to narrow networks is dying down.

What role should hospitalists play in network referrals?

High functioning hospitalist practices should lead the discussion with patients and the health care team on referrals to network SNFs. Why? Patients are looking for their doctors to guide them on such decisions. Only if the physician opts not to have the discussion will patients look to the case manager for direction on which postacute facility to choose. A better option still would be for the hospitalists to partner with case managers to have the conversation with patients. In such a scenario, the hospitalist can begin the discussion and cover the major points, and the case manager can follow with more detailed information. For less mature hospitalist practices, the case manager can play a larger role in the discussion. In any case, as value-based models become ubiquitous, and shared savings become a driver of hospitalist revenue, hospitalists’ knowledge of and active participation in conversations around narrow networks and referrals will be necessary.

Dr. Whitcomb is chief medical officer at Remedy Partners in Darien, Conn. He is a cofounder and past president of SHM.

By now, nearly all hospitals are developing networks of postacute facilities for some or all of their patients, such as those in ACOs, bundled payments, or other value-based programs. Commonly referred to as preferred providers, performance networks, narrow networks, or similar, these networks of skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) and other entities that provide postacute care (like home health agencies) are usually chosen because they have demonstrated that they provide high quality, cost-effective care for patients after they leave the hospital.

While case managers are often the ones who counsel patients and caregivers on the details of the network, hospitalists should have at least a high-level grasp of which facilities are on the list and what the network selection criteria are. I would argue that hospitalists should lead the discussion with patients on postacute facility selection as it relates to which facilities are in the network and why going to a network facility is advantageous. Why? Because as hospitalist practices begin to share clinical and financial risk for patients, or at least become eligible to share in savings as MACRA encourages, they will have a vested interest in network facilities’ performance.

Postacute care network selection criteria

There is a range of criteria – usually incorporating measures of quality and efficiency – for including providers like SNFs in networks. In terms of quality, criteria can include physician/provider availability, star ratings on Nursing Home Compare, care transitions measures, Department of Public Health inspection survey scores, Joint Commission accreditation, etc.

A few caveats regarding specific selection criteria:

Star ratings on Nursing Home Compare

These are derived from nursing staffing ratios, health inspections, and 16 quality measures. More than half of the quality measures pertain to long-stay residents who typically are not in the ACO or bundled payment program for which the network was created (these are usually short-stay patients).

SNF length of stay

High readmission rates from a SNF can actually lower its length of stay, so including “balancing” measures such as readmissions should be considered.

What about patient choice?

Narrow postacute networks are not only becoming the norm, but there is also broad recognition from CMS, MedPAC, and industry leaders that value-based payment programs require such networks to succeed. That said, case managers and other discharge planners may still resist networks on the grounds that they might be perceived as restricting patient choice. One approach to balancing differing views on patient choice is to give patients the traditional longer list of available postacute providers, and also furnish the shorter network list accompanied by an explanation of why certain SNFs are in the network. Thankfully, as ACOs and bundles become widespread, resistance to narrow networks is dying down.

What role should hospitalists play in network referrals?

High functioning hospitalist practices should lead the discussion with patients and the health care team on referrals to network SNFs. Why? Patients are looking for their doctors to guide them on such decisions. Only if the physician opts not to have the discussion will patients look to the case manager for direction on which postacute facility to choose. A better option still would be for the hospitalists to partner with case managers to have the conversation with patients. In such a scenario, the hospitalist can begin the discussion and cover the major points, and the case manager can follow with more detailed information. For less mature hospitalist practices, the case manager can play a larger role in the discussion. In any case, as value-based models become ubiquitous, and shared savings become a driver of hospitalist revenue, hospitalists’ knowledge of and active participation in conversations around narrow networks and referrals will be necessary.

Dr. Whitcomb is chief medical officer at Remedy Partners in Darien, Conn. He is a cofounder and past president of SHM.