User login

Erythematous Plaques and Nodules on the Abdomen and Groin

The Diagnosis: Inflammatory Urothelial Carcinoma

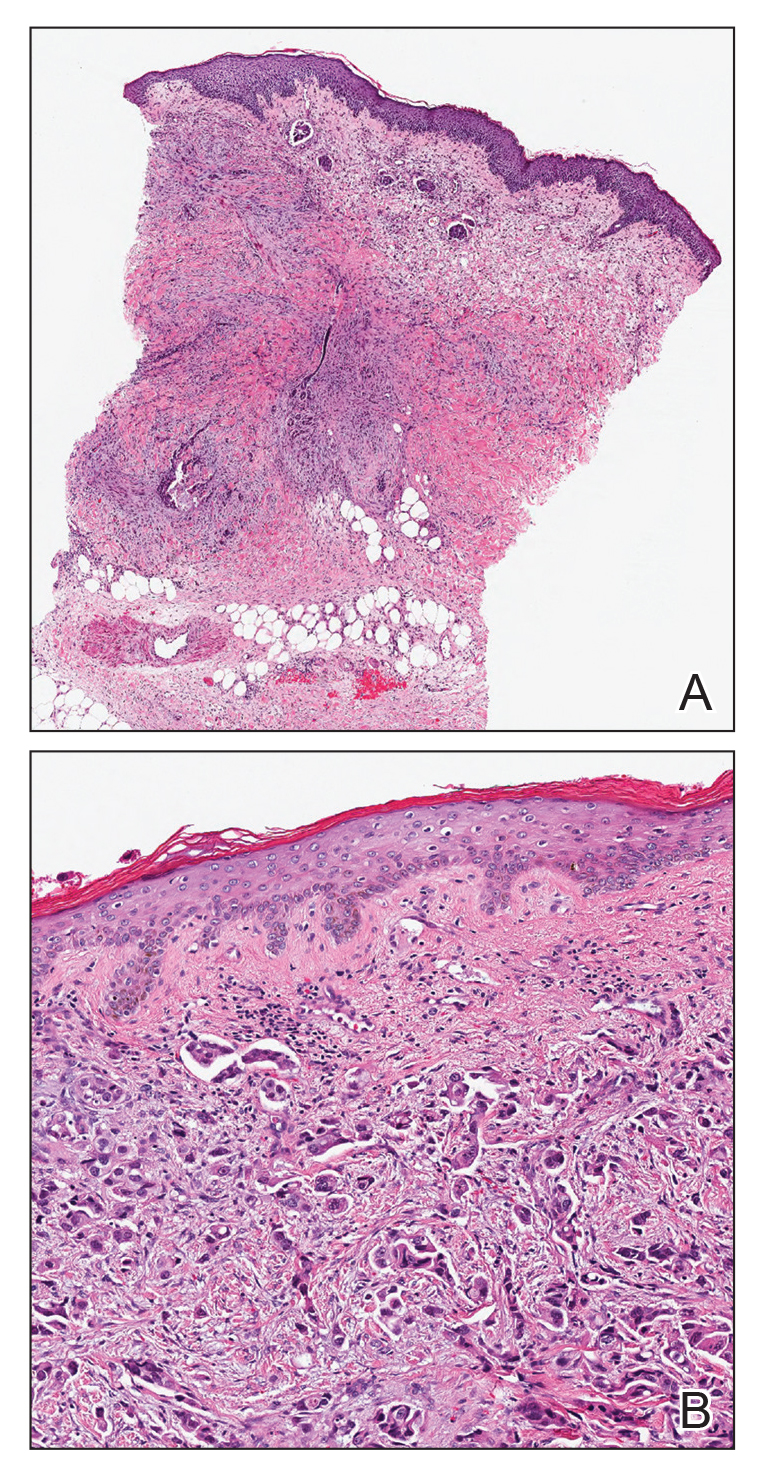

Microscopic examination revealed metastatic carcinoma with extensive dermal lymphatic invasion (Figure). Immunohistochemical stains were positive for p63 and GATA3, markers for urothelial carcinomas, and negative for S-100 and Melan-A, markers for melanoma. Thus, the biopsy was compatible with a diagnosis of urothelial carcinoma. Gram and Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stains were negative for bacterial or fungal organisms. An additional 4-mm punch biopsy was performed of the left thigh at the distal-most aspect of the eruption to determine the extent of cutaneous metastasis. Pathology again showed metastatic urothelial carcinoma with extensive dermal lymphatic involvement and overlying epidermal spongiosis.

The patient had a history of bladder cancer diagnosed 1.5 years prior to presentation. It was a high-grade (World Health Organization) urothelial carcinoma that penetrated the bladder muscular wall, focally infiltrating into pericystic fat with multifocal seeding of pericystic lymphatics. It was unresponsive to bacillus Calmette-Guérin therapy. He underwent a cystoprostatectomy and bilateral staging lymph node dissection with clear surgical margins without adjuvant chemotherapy or radiation. He also reported a history of 2 prior cutaneous melanomas that were excised without sentinel lymph node biopsy.

Four months prior to presentation, he developed a mildly pruritic cutaneous eruption on the abdomen that was treated with topical miconazole for presumed tinea cruris without improvement. He also was previously diagnosed with candidiasis of his urostomy and was taking oral fluconazole. The patient was admitted for the abdominal pain and distension, and computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis revealed peritoneal carcinomatosis resulting in mechanical small bowel obstruction as well as enlarged pelvic and retroperitoneal lymph nodes. Confirmation of metastatic disease via skin biopsy avoided an invasive peritoneal biopsy. He was treated with triamcinolone acetonide ointment 0.1% with moderate relief of pruritus, and a palliative percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube was placed for bowel decompression. The patient's hospital course was complicated by Proteus mirabilis bacteremia requiring cefepime. He was transitioned to home hospice and died 1 month after presentation.

Inflammatory carcinoma, also called carcinoma erysipeloides, is a type of cutaneous metastasis most commonly seen in breast adenocarcinoma. Reported cases secondary to urothelial carcinoma are rare and most often involve the abdomen, groin, and lower extremities.1-5 Clinically, inflammatory carcinoma presents as erythematous indurated patches or plaques with well-defined borders, often with edema, warmth, and tenderness. Its morphologic appearance is due to the obstruction of lymphatic vessels by tumor cells and the release of inflammatory cytokines. Its presentation can mimic other dermatoses such as cellulitis, erysipelas, fungal infection, radiation dermatitis, Majocchi granuloma, or contact dermatitis.6 Cutaneous metastases may be the first clinical manifestations of metastatic disease, and they may occur due to hematogenous and lymphatic spread, direct contiguous tissue invasion, or iatrogenic implantation following surgical excision of the primary tumor. Histologically, nuclear markers GATA3 and p63 stain positively in urothelial carcinomas and are negative in prostatic adenocarcinomas.7,8 Other markers may be used such as cytokeratins 7 and 20, which are cytoplasmic epithelial markers that both stain positive in urothelial neoplasms.9

Inflammatory carcinoma may be treated with radiation or systemic chemotherapy depending on the extent of systemic involvement in the patient; however, its presence portends a poor prognosis. Less than 1% of genitourinary malignancies have cutaneous involvement, and median disease-specific survival is less than 6 months from presentation of the cutaneous metastasis.10 Clinicians faced with a recalcitrant inflammatory cutaneous eruption should maintain a high index of suspicion for cutaneous metastases, particularly in patients with a history of cancer. Early dermatology referral may help establish the diagnosis and guide disease-targeted therapy or goals of care discussions.

- Grace SA, Livingood MR, Boyd AS. Metastatic urothelial carcinoma presenting as carcinoma erysipeloides. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:513-515.

- Zangrilli A, Saraceno R, Sarmati L, et al. Erysipeloid cutaneous metastasis from bladder carcinoma. Eur J Dermatol. 2007;17:534-536.

- Chang CP, Lee Y, Shih HJ. Unusual presentation of cutaneous metastasis from bladder urothelial carcinoma. Chin J Cancer Res. 2013;25:362-365.

- Aloi F, Solaroli C, Paradiso M, et al. Inflammatory type cutaneous metastasis of bladder neoplasm: erysipeloid carcinoma [in Italian]. Minerva Urol Nefrol. 1998;50:205-208.

- Alcaraz I, Cerroni L, Rutten A, et al. Cutaneous metastases from internal malignancies: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:347-393.

- Al Ameer A, Imran M, Kaliyadan F, et al. Carcinoma erysipeloides as a presenting feature of breast carcinoma: a case report and brief review of literature. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6:396-398.

- Chang A, Amin A, Gabrielson E, et al. Utility of GATA3 immunohistochemistry in differentiating urothelial carcinoma from prostate adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinomas of the uterine cervix, anus, and lung. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:1472-1476.

- Ud Din N, Qureshi A, Mansoor S. Utility of p63 immunohistochemical stain in differentiating urothelial carcinomas from adenocarcinomas of prostate. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2011;54:59-62.

- Bassily NH, Vallorosi CJ, Akdas G, et al. Coordinate expression of cytokeratins 7 and 20 in prostate adenocarcinoma and bladder urothelial carcinoma. Am J Clin Pathol. 2000;113:383-388.

- Mueller TJ, Wu H, Greenberg RE, et al. Cutaneous metastases from genitourinary malignancies. Urology. 2004;63:1021-1026.

The Diagnosis: Inflammatory Urothelial Carcinoma

Microscopic examination revealed metastatic carcinoma with extensive dermal lymphatic invasion (Figure). Immunohistochemical stains were positive for p63 and GATA3, markers for urothelial carcinomas, and negative for S-100 and Melan-A, markers for melanoma. Thus, the biopsy was compatible with a diagnosis of urothelial carcinoma. Gram and Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stains were negative for bacterial or fungal organisms. An additional 4-mm punch biopsy was performed of the left thigh at the distal-most aspect of the eruption to determine the extent of cutaneous metastasis. Pathology again showed metastatic urothelial carcinoma with extensive dermal lymphatic involvement and overlying epidermal spongiosis.

The patient had a history of bladder cancer diagnosed 1.5 years prior to presentation. It was a high-grade (World Health Organization) urothelial carcinoma that penetrated the bladder muscular wall, focally infiltrating into pericystic fat with multifocal seeding of pericystic lymphatics. It was unresponsive to bacillus Calmette-Guérin therapy. He underwent a cystoprostatectomy and bilateral staging lymph node dissection with clear surgical margins without adjuvant chemotherapy or radiation. He also reported a history of 2 prior cutaneous melanomas that were excised without sentinel lymph node biopsy.

Four months prior to presentation, he developed a mildly pruritic cutaneous eruption on the abdomen that was treated with topical miconazole for presumed tinea cruris without improvement. He also was previously diagnosed with candidiasis of his urostomy and was taking oral fluconazole. The patient was admitted for the abdominal pain and distension, and computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis revealed peritoneal carcinomatosis resulting in mechanical small bowel obstruction as well as enlarged pelvic and retroperitoneal lymph nodes. Confirmation of metastatic disease via skin biopsy avoided an invasive peritoneal biopsy. He was treated with triamcinolone acetonide ointment 0.1% with moderate relief of pruritus, and a palliative percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube was placed for bowel decompression. The patient's hospital course was complicated by Proteus mirabilis bacteremia requiring cefepime. He was transitioned to home hospice and died 1 month after presentation.

Inflammatory carcinoma, also called carcinoma erysipeloides, is a type of cutaneous metastasis most commonly seen in breast adenocarcinoma. Reported cases secondary to urothelial carcinoma are rare and most often involve the abdomen, groin, and lower extremities.1-5 Clinically, inflammatory carcinoma presents as erythematous indurated patches or plaques with well-defined borders, often with edema, warmth, and tenderness. Its morphologic appearance is due to the obstruction of lymphatic vessels by tumor cells and the release of inflammatory cytokines. Its presentation can mimic other dermatoses such as cellulitis, erysipelas, fungal infection, radiation dermatitis, Majocchi granuloma, or contact dermatitis.6 Cutaneous metastases may be the first clinical manifestations of metastatic disease, and they may occur due to hematogenous and lymphatic spread, direct contiguous tissue invasion, or iatrogenic implantation following surgical excision of the primary tumor. Histologically, nuclear markers GATA3 and p63 stain positively in urothelial carcinomas and are negative in prostatic adenocarcinomas.7,8 Other markers may be used such as cytokeratins 7 and 20, which are cytoplasmic epithelial markers that both stain positive in urothelial neoplasms.9

Inflammatory carcinoma may be treated with radiation or systemic chemotherapy depending on the extent of systemic involvement in the patient; however, its presence portends a poor prognosis. Less than 1% of genitourinary malignancies have cutaneous involvement, and median disease-specific survival is less than 6 months from presentation of the cutaneous metastasis.10 Clinicians faced with a recalcitrant inflammatory cutaneous eruption should maintain a high index of suspicion for cutaneous metastases, particularly in patients with a history of cancer. Early dermatology referral may help establish the diagnosis and guide disease-targeted therapy or goals of care discussions.

The Diagnosis: Inflammatory Urothelial Carcinoma

Microscopic examination revealed metastatic carcinoma with extensive dermal lymphatic invasion (Figure). Immunohistochemical stains were positive for p63 and GATA3, markers for urothelial carcinomas, and negative for S-100 and Melan-A, markers for melanoma. Thus, the biopsy was compatible with a diagnosis of urothelial carcinoma. Gram and Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stains were negative for bacterial or fungal organisms. An additional 4-mm punch biopsy was performed of the left thigh at the distal-most aspect of the eruption to determine the extent of cutaneous metastasis. Pathology again showed metastatic urothelial carcinoma with extensive dermal lymphatic involvement and overlying epidermal spongiosis.

The patient had a history of bladder cancer diagnosed 1.5 years prior to presentation. It was a high-grade (World Health Organization) urothelial carcinoma that penetrated the bladder muscular wall, focally infiltrating into pericystic fat with multifocal seeding of pericystic lymphatics. It was unresponsive to bacillus Calmette-Guérin therapy. He underwent a cystoprostatectomy and bilateral staging lymph node dissection with clear surgical margins without adjuvant chemotherapy or radiation. He also reported a history of 2 prior cutaneous melanomas that were excised without sentinel lymph node biopsy.

Four months prior to presentation, he developed a mildly pruritic cutaneous eruption on the abdomen that was treated with topical miconazole for presumed tinea cruris without improvement. He also was previously diagnosed with candidiasis of his urostomy and was taking oral fluconazole. The patient was admitted for the abdominal pain and distension, and computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis revealed peritoneal carcinomatosis resulting in mechanical small bowel obstruction as well as enlarged pelvic and retroperitoneal lymph nodes. Confirmation of metastatic disease via skin biopsy avoided an invasive peritoneal biopsy. He was treated with triamcinolone acetonide ointment 0.1% with moderate relief of pruritus, and a palliative percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube was placed for bowel decompression. The patient's hospital course was complicated by Proteus mirabilis bacteremia requiring cefepime. He was transitioned to home hospice and died 1 month after presentation.

Inflammatory carcinoma, also called carcinoma erysipeloides, is a type of cutaneous metastasis most commonly seen in breast adenocarcinoma. Reported cases secondary to urothelial carcinoma are rare and most often involve the abdomen, groin, and lower extremities.1-5 Clinically, inflammatory carcinoma presents as erythematous indurated patches or plaques with well-defined borders, often with edema, warmth, and tenderness. Its morphologic appearance is due to the obstruction of lymphatic vessels by tumor cells and the release of inflammatory cytokines. Its presentation can mimic other dermatoses such as cellulitis, erysipelas, fungal infection, radiation dermatitis, Majocchi granuloma, or contact dermatitis.6 Cutaneous metastases may be the first clinical manifestations of metastatic disease, and they may occur due to hematogenous and lymphatic spread, direct contiguous tissue invasion, or iatrogenic implantation following surgical excision of the primary tumor. Histologically, nuclear markers GATA3 and p63 stain positively in urothelial carcinomas and are negative in prostatic adenocarcinomas.7,8 Other markers may be used such as cytokeratins 7 and 20, which are cytoplasmic epithelial markers that both stain positive in urothelial neoplasms.9

Inflammatory carcinoma may be treated with radiation or systemic chemotherapy depending on the extent of systemic involvement in the patient; however, its presence portends a poor prognosis. Less than 1% of genitourinary malignancies have cutaneous involvement, and median disease-specific survival is less than 6 months from presentation of the cutaneous metastasis.10 Clinicians faced with a recalcitrant inflammatory cutaneous eruption should maintain a high index of suspicion for cutaneous metastases, particularly in patients with a history of cancer. Early dermatology referral may help establish the diagnosis and guide disease-targeted therapy or goals of care discussions.

- Grace SA, Livingood MR, Boyd AS. Metastatic urothelial carcinoma presenting as carcinoma erysipeloides. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:513-515.

- Zangrilli A, Saraceno R, Sarmati L, et al. Erysipeloid cutaneous metastasis from bladder carcinoma. Eur J Dermatol. 2007;17:534-536.

- Chang CP, Lee Y, Shih HJ. Unusual presentation of cutaneous metastasis from bladder urothelial carcinoma. Chin J Cancer Res. 2013;25:362-365.

- Aloi F, Solaroli C, Paradiso M, et al. Inflammatory type cutaneous metastasis of bladder neoplasm: erysipeloid carcinoma [in Italian]. Minerva Urol Nefrol. 1998;50:205-208.

- Alcaraz I, Cerroni L, Rutten A, et al. Cutaneous metastases from internal malignancies: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:347-393.

- Al Ameer A, Imran M, Kaliyadan F, et al. Carcinoma erysipeloides as a presenting feature of breast carcinoma: a case report and brief review of literature. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6:396-398.

- Chang A, Amin A, Gabrielson E, et al. Utility of GATA3 immunohistochemistry in differentiating urothelial carcinoma from prostate adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinomas of the uterine cervix, anus, and lung. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:1472-1476.

- Ud Din N, Qureshi A, Mansoor S. Utility of p63 immunohistochemical stain in differentiating urothelial carcinomas from adenocarcinomas of prostate. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2011;54:59-62.

- Bassily NH, Vallorosi CJ, Akdas G, et al. Coordinate expression of cytokeratins 7 and 20 in prostate adenocarcinoma and bladder urothelial carcinoma. Am J Clin Pathol. 2000;113:383-388.

- Mueller TJ, Wu H, Greenberg RE, et al. Cutaneous metastases from genitourinary malignancies. Urology. 2004;63:1021-1026.

- Grace SA, Livingood MR, Boyd AS. Metastatic urothelial carcinoma presenting as carcinoma erysipeloides. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:513-515.

- Zangrilli A, Saraceno R, Sarmati L, et al. Erysipeloid cutaneous metastasis from bladder carcinoma. Eur J Dermatol. 2007;17:534-536.

- Chang CP, Lee Y, Shih HJ. Unusual presentation of cutaneous metastasis from bladder urothelial carcinoma. Chin J Cancer Res. 2013;25:362-365.

- Aloi F, Solaroli C, Paradiso M, et al. Inflammatory type cutaneous metastasis of bladder neoplasm: erysipeloid carcinoma [in Italian]. Minerva Urol Nefrol. 1998;50:205-208.

- Alcaraz I, Cerroni L, Rutten A, et al. Cutaneous metastases from internal malignancies: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:347-393.

- Al Ameer A, Imran M, Kaliyadan F, et al. Carcinoma erysipeloides as a presenting feature of breast carcinoma: a case report and brief review of literature. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6:396-398.

- Chang A, Amin A, Gabrielson E, et al. Utility of GATA3 immunohistochemistry in differentiating urothelial carcinoma from prostate adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinomas of the uterine cervix, anus, and lung. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:1472-1476.

- Ud Din N, Qureshi A, Mansoor S. Utility of p63 immunohistochemical stain in differentiating urothelial carcinomas from adenocarcinomas of prostate. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2011;54:59-62.

- Bassily NH, Vallorosi CJ, Akdas G, et al. Coordinate expression of cytokeratins 7 and 20 in prostate adenocarcinoma and bladder urothelial carcinoma. Am J Clin Pathol. 2000;113:383-388.

- Mueller TJ, Wu H, Greenberg RE, et al. Cutaneous metastases from genitourinary malignancies. Urology. 2004;63:1021-1026.

An 82-year-old man presented with acute abdominal pain and distension as well as an abdominal rash of 4 months' duration that was expanding despite treatment with topical miconazole. He had a history of melanoma and bladder cancer treated with cystoprostatectomy. He previously was diagnosed with candidiasis of his urostomy and was taking oral fluconazole. Physical examination revealed a large, well-demarcated, erythematous, smooth plaque covering the entire abdomen, scrotum, penis, inguinal folds, and bilateral upper thighs, with several satellite plaques and firm nodules clustered around the umbilicus. An 8-mm punch biopsy of a periumbilical nodule was performed.

Sporotrichoid Fluctuant Nodules

The Diagnosis: Atypical Mycobacterial Infection

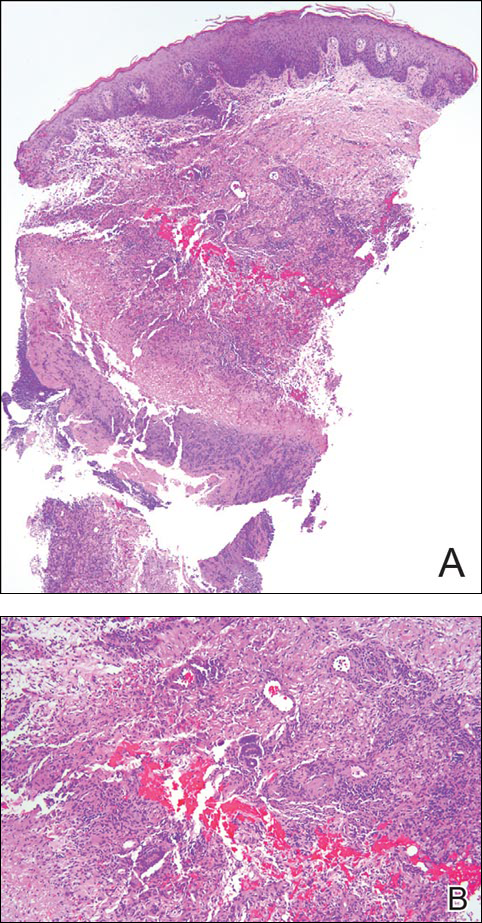

Punch biopsy specimens demonstrated necrotizing granulomatous inflammation in the dermis and subcutis (Figure). Special staining for microorganisms was negative. Tissue culture grew Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare (MAI). The patient began treatment with azithromycin, ethambutol, and rifabutin. Tissue susceptibilities later showed resistance to rifabutin and sensitivity to clarithromycin, moxifloxacin, and clofazimine. She subsequently was switched to azithromycin, clofazimine, and moxifloxacin with good response.

Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare is a slow-growing, nonchromogenic, atypical mycobacteria. Although ubiquitous, it tends to only cause serious infection in the setting of immunosuppression. Transmission usually is through the respiratory or gastrointestinal tract.1 Skin infections with MAI are uncommon and usually are secondary to seeding from disseminated infection or from direct inoculation.2

The clinical presentations of primary cutaneous MAI are myriad, including an isolated red nodule, multiple ulcers, abscesses, draining sinuses, facial nodules, granulomatous plaques, and panniculitis.2,3 Of 3 reported cases of primary cutaneous MAI in the form of sporotrichoid lesions, 2 involved patients with AIDS2 and 1 involved a cardiac transplant recipient.4

Cutaneous MAI is typically diagnosed with skin biopsy and tissue culture. Tissue culture is critical for determining the specific mycobacterial species and antibiotic susceptibilities. Polymerase chain reaction has been utilized to rapidly diagnose cutaneous MAI infection from an acid-fast bacilli–positive tissue sample in which the tissue culture was negative.5

Recommended treatment protocols for MAI involve multidrug regimens because of the intrinsic resistance of MAI and the concern for development of resistance with monotherapy.2 No definitive guidelines exist for treatment of primary cutaneous MAI infections. However, regimens for the treatment of pulmonary infection that also have been successfully utilized for cutaneous infection include a macrolide, ethambutol, and a rifamycin.6 Clinicians should be aware of MAI as a cause of primary cutaneous infections presenting as lymphocutaneous suppurative nodules and ulcerations.

- Hautmann G, Lotti T. Atypical mycobacterial infections of the skin. Dermatol Clin. 1994;12:657-668.

- Kayal JD, McCall CO. Sporotrichoid cutaneous Mycobacterium avium complex infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47(5 suppl):S249-S250.

- Kullavanijaya P, Sirimachan S, Surarak S. Primary cutaneous infection with Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex resembling lupus vulgaris. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136:264-266.

- Wood C, Nickoloff BJ, Todes-Taylor NR. Pseudotumor resulting from atypical mycobacterial infection: a “histoid” variety of Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex infection. Am J Clin Pathol. 1985;83:524-527.

- Carlos CA, Tang YW, Adler DJ, et al. Mycobacterial infection identified with broad-range PCR amplification and suspension array identification. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:795-797.

- Griffith DE, Aksamit T, Brown-Elliot BA, et al. An official ATS/IDSA statement: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:367-416.

The Diagnosis: Atypical Mycobacterial Infection

Punch biopsy specimens demonstrated necrotizing granulomatous inflammation in the dermis and subcutis (Figure). Special staining for microorganisms was negative. Tissue culture grew Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare (MAI). The patient began treatment with azithromycin, ethambutol, and rifabutin. Tissue susceptibilities later showed resistance to rifabutin and sensitivity to clarithromycin, moxifloxacin, and clofazimine. She subsequently was switched to azithromycin, clofazimine, and moxifloxacin with good response.

Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare is a slow-growing, nonchromogenic, atypical mycobacteria. Although ubiquitous, it tends to only cause serious infection in the setting of immunosuppression. Transmission usually is through the respiratory or gastrointestinal tract.1 Skin infections with MAI are uncommon and usually are secondary to seeding from disseminated infection or from direct inoculation.2

The clinical presentations of primary cutaneous MAI are myriad, including an isolated red nodule, multiple ulcers, abscesses, draining sinuses, facial nodules, granulomatous plaques, and panniculitis.2,3 Of 3 reported cases of primary cutaneous MAI in the form of sporotrichoid lesions, 2 involved patients with AIDS2 and 1 involved a cardiac transplant recipient.4

Cutaneous MAI is typically diagnosed with skin biopsy and tissue culture. Tissue culture is critical for determining the specific mycobacterial species and antibiotic susceptibilities. Polymerase chain reaction has been utilized to rapidly diagnose cutaneous MAI infection from an acid-fast bacilli–positive tissue sample in which the tissue culture was negative.5

Recommended treatment protocols for MAI involve multidrug regimens because of the intrinsic resistance of MAI and the concern for development of resistance with monotherapy.2 No definitive guidelines exist for treatment of primary cutaneous MAI infections. However, regimens for the treatment of pulmonary infection that also have been successfully utilized for cutaneous infection include a macrolide, ethambutol, and a rifamycin.6 Clinicians should be aware of MAI as a cause of primary cutaneous infections presenting as lymphocutaneous suppurative nodules and ulcerations.

The Diagnosis: Atypical Mycobacterial Infection

Punch biopsy specimens demonstrated necrotizing granulomatous inflammation in the dermis and subcutis (Figure). Special staining for microorganisms was negative. Tissue culture grew Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare (MAI). The patient began treatment with azithromycin, ethambutol, and rifabutin. Tissue susceptibilities later showed resistance to rifabutin and sensitivity to clarithromycin, moxifloxacin, and clofazimine. She subsequently was switched to azithromycin, clofazimine, and moxifloxacin with good response.

Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare is a slow-growing, nonchromogenic, atypical mycobacteria. Although ubiquitous, it tends to only cause serious infection in the setting of immunosuppression. Transmission usually is through the respiratory or gastrointestinal tract.1 Skin infections with MAI are uncommon and usually are secondary to seeding from disseminated infection or from direct inoculation.2

The clinical presentations of primary cutaneous MAI are myriad, including an isolated red nodule, multiple ulcers, abscesses, draining sinuses, facial nodules, granulomatous plaques, and panniculitis.2,3 Of 3 reported cases of primary cutaneous MAI in the form of sporotrichoid lesions, 2 involved patients with AIDS2 and 1 involved a cardiac transplant recipient.4

Cutaneous MAI is typically diagnosed with skin biopsy and tissue culture. Tissue culture is critical for determining the specific mycobacterial species and antibiotic susceptibilities. Polymerase chain reaction has been utilized to rapidly diagnose cutaneous MAI infection from an acid-fast bacilli–positive tissue sample in which the tissue culture was negative.5

Recommended treatment protocols for MAI involve multidrug regimens because of the intrinsic resistance of MAI and the concern for development of resistance with monotherapy.2 No definitive guidelines exist for treatment of primary cutaneous MAI infections. However, regimens for the treatment of pulmonary infection that also have been successfully utilized for cutaneous infection include a macrolide, ethambutol, and a rifamycin.6 Clinicians should be aware of MAI as a cause of primary cutaneous infections presenting as lymphocutaneous suppurative nodules and ulcerations.

- Hautmann G, Lotti T. Atypical mycobacterial infections of the skin. Dermatol Clin. 1994;12:657-668.

- Kayal JD, McCall CO. Sporotrichoid cutaneous Mycobacterium avium complex infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47(5 suppl):S249-S250.

- Kullavanijaya P, Sirimachan S, Surarak S. Primary cutaneous infection with Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex resembling lupus vulgaris. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136:264-266.

- Wood C, Nickoloff BJ, Todes-Taylor NR. Pseudotumor resulting from atypical mycobacterial infection: a “histoid” variety of Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex infection. Am J Clin Pathol. 1985;83:524-527.

- Carlos CA, Tang YW, Adler DJ, et al. Mycobacterial infection identified with broad-range PCR amplification and suspension array identification. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:795-797.

- Griffith DE, Aksamit T, Brown-Elliot BA, et al. An official ATS/IDSA statement: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:367-416.

- Hautmann G, Lotti T. Atypical mycobacterial infections of the skin. Dermatol Clin. 1994;12:657-668.

- Kayal JD, McCall CO. Sporotrichoid cutaneous Mycobacterium avium complex infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47(5 suppl):S249-S250.

- Kullavanijaya P, Sirimachan S, Surarak S. Primary cutaneous infection with Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex resembling lupus vulgaris. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136:264-266.

- Wood C, Nickoloff BJ, Todes-Taylor NR. Pseudotumor resulting from atypical mycobacterial infection: a “histoid” variety of Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex infection. Am J Clin Pathol. 1985;83:524-527.

- Carlos CA, Tang YW, Adler DJ, et al. Mycobacterial infection identified with broad-range PCR amplification and suspension array identification. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:795-797.

- Griffith DE, Aksamit T, Brown-Elliot BA, et al. An official ATS/IDSA statement: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:367-416.

A woman in her 50s presented with low-grade subjective intermittent fevers and painful draining ulcerations on the legs of 7 months’ duration. Her medical history was remarkable for polymyositis and interstitial lung disease managed with prednisone and mycophenolate mofetil. While living in Taiwan, she developed lower extremity abscesses and persistent fevers. The patient denied any skin injuries or exposure to animals or brackish water. Mycophenolate mofetil was discontinued, and she was treated with multiple antibiotics alone and in combination without improvement, including amoxicillin–clavulanic acid, levofloxacin, azithromycin, moxifloxacin, rifampin, rifabutin, and ethambutol. She returned to the United States for evaluation. Physical examination revealed ulcerations with purulent drainage and interconnected sinus tracts with rare fluctuant nodules along the right leg. A single similar lesion was present on the right chest wall. There was no clinical evidence of disseminated disease.