User login

Botulinum Toxin and Glycopyrrolate Combination Therapy for Hailey-Hailey Disease

To the Editor:

Hailey-Hailey disease (HHD)(also known as familial benign chronic pemphigus) is an inherited autosomal-dominant condition in the family of chronic bullous diseases. It is characterized by flaccid blisters, erosions, and macerated vegetative plaques with a predilection for intertriginous sites. Lesions often are weeping, painful, pruritic, and malodorous, leading to decreased quality of life for patients. Complications of this chronic disease include an increased risk for secondary infection and malignant transformation to squamous cell carcinoma.1

Treatment of HHD remains difficult. Topical steroids, oral steroids, and ablative techniques such as dermabrasion and ablative lasers are the most widely reported therapies. OnabotulinumtoxinA has been described as a successful treatment for patients with HHD, including for disease recalcitrant to other therapies.2 We describe 2 patients with HHD who responded to treatment with intralesional onabotulinumtoxinA injections with and without adjuvant oral glycopyrrolate.

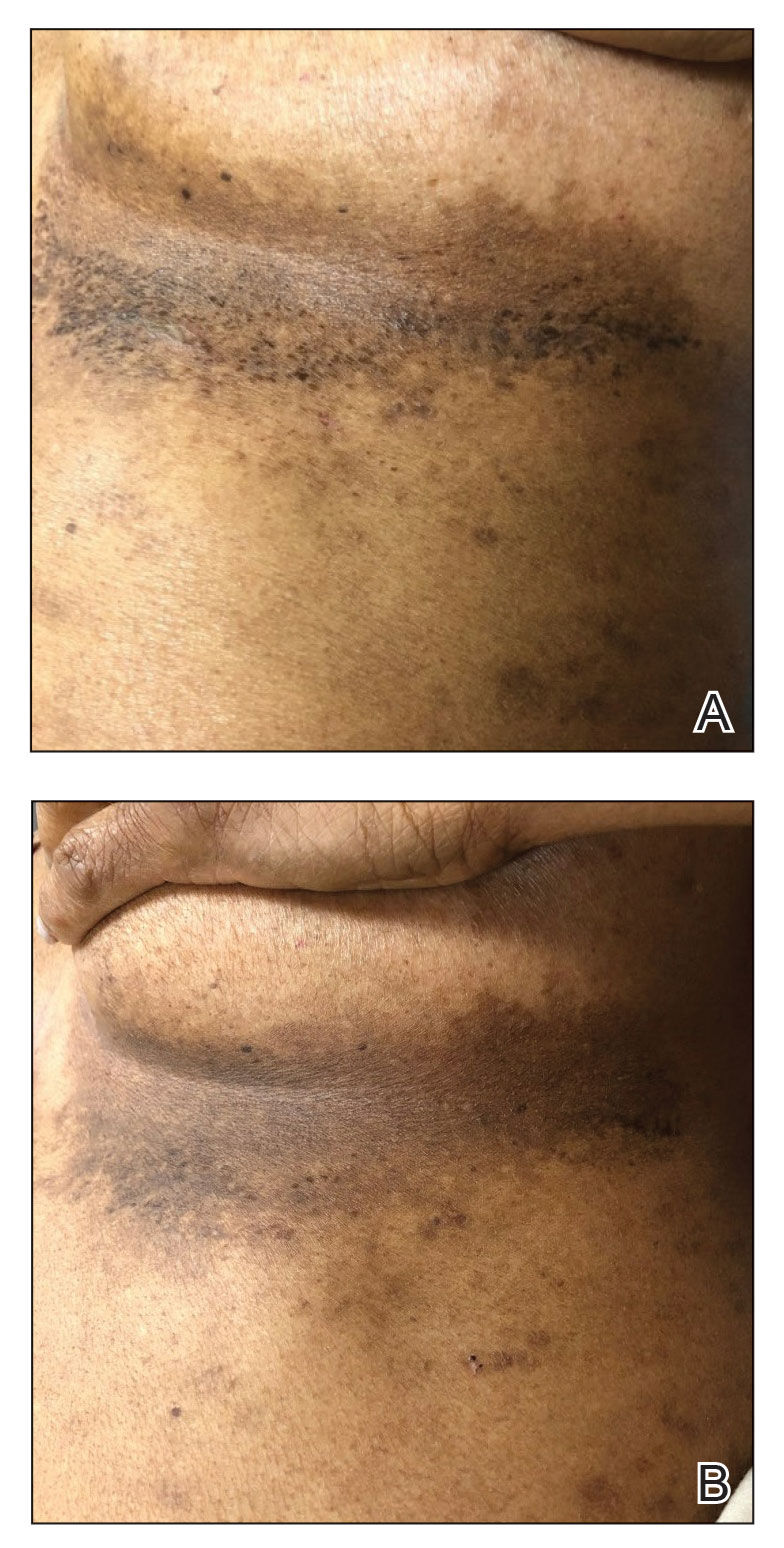

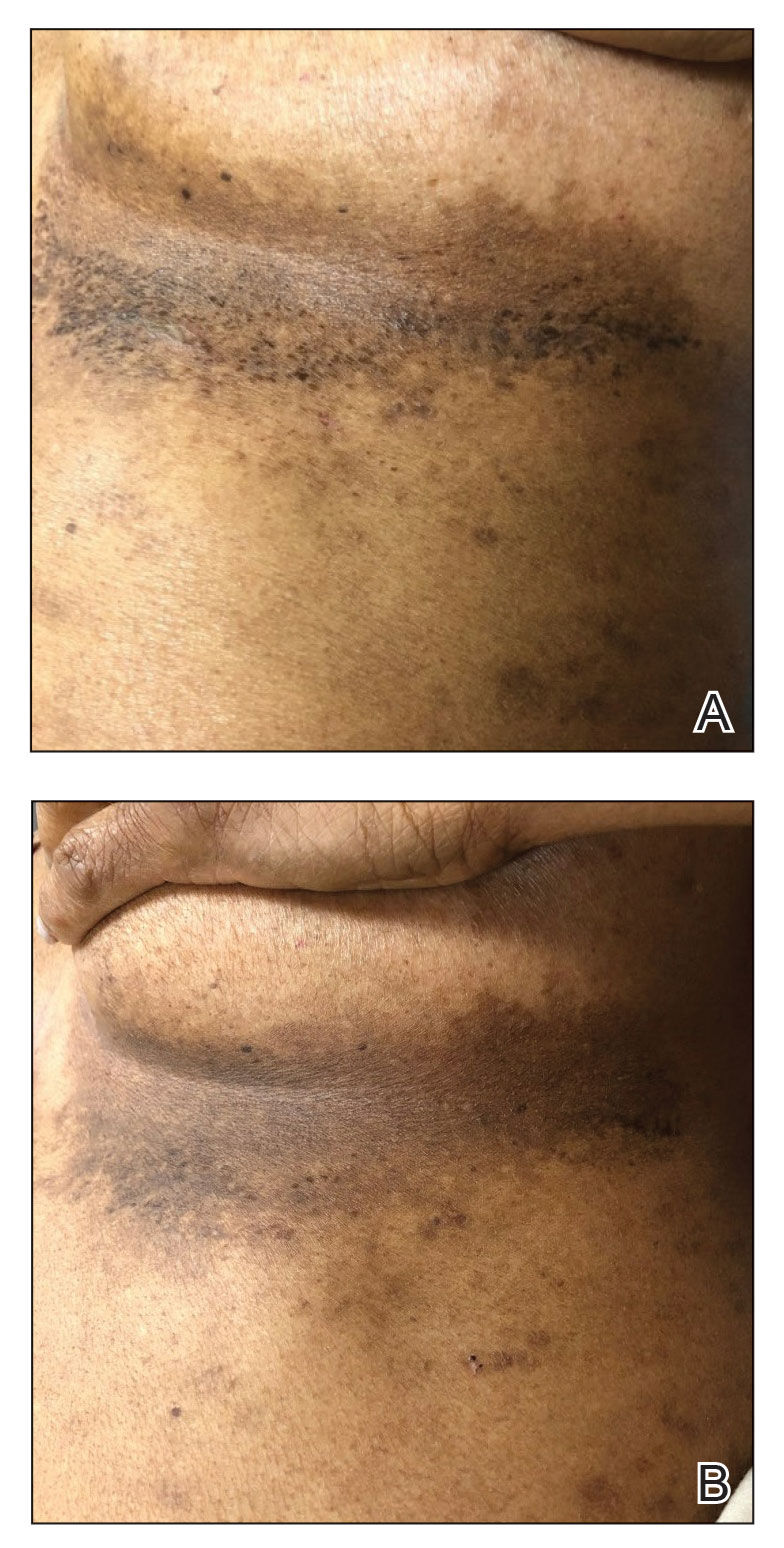

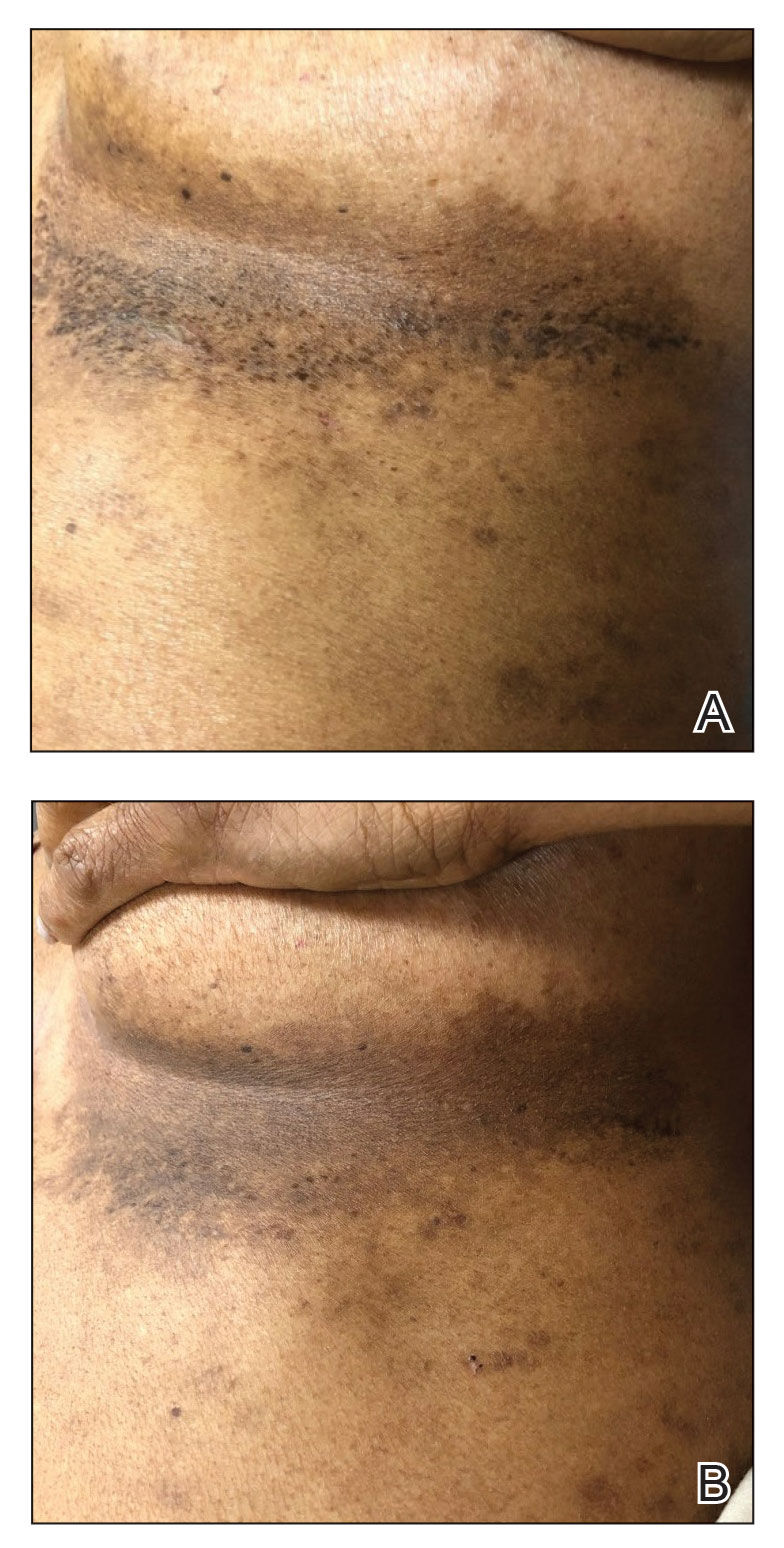

A 54-year-old woman presented with painful flaccid blisters under the breasts (Figure 1A) and in the axillae and groin of 3 weeks’ duration. Biopsy results from this initial visit were consistent with a diagnosis of HHD. The patient reported that the onset of blisters coincided with episodes of severe hyperhidrosis. Therapy with topical and oral steroids, antifungals, antibiotics, and topical aluminum chloride failed to achieve adequate disease control. After a discussion of the risks and benefits, the patient agreed to treatment with injections of onabotulinumtoxinA. At months 0, 3, and 6, the patient received 50 U of onabotulinumtoxinA under the breasts and in the axillae and the groin, for a total of 250 U each session. Each injection consisted of 2.5 U of onabotulinumtoxinA spaced 1-cm apart. Clinical improvement was noted within 2 weeks of initiating neuromodulator therapy. Follow-up at 9 months demonstrated improvement (Figure 1B); however, complete clearance was not achieved, and the patient required ongoing treatment with onabotulinumtoxinA every 3 months.

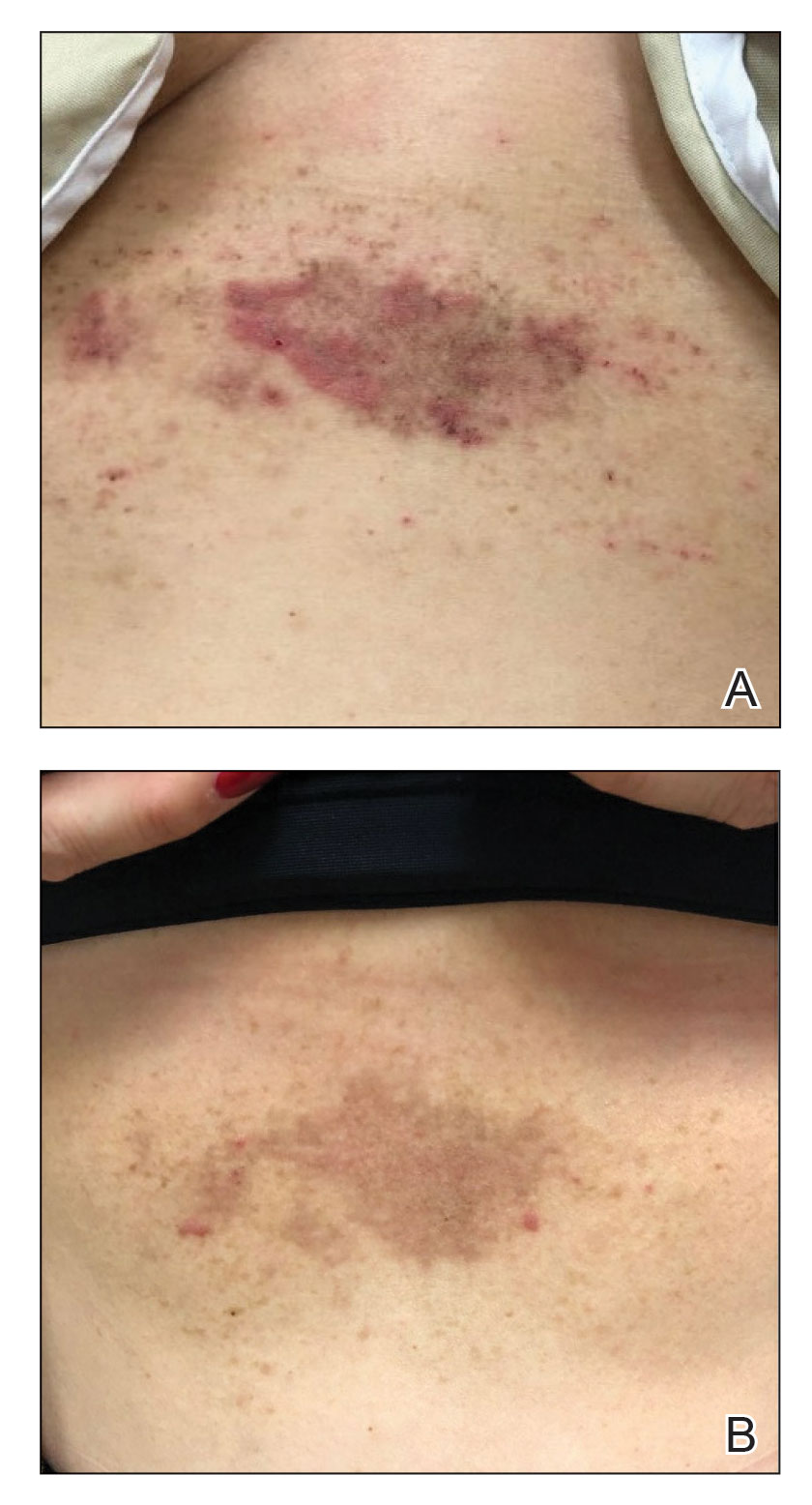

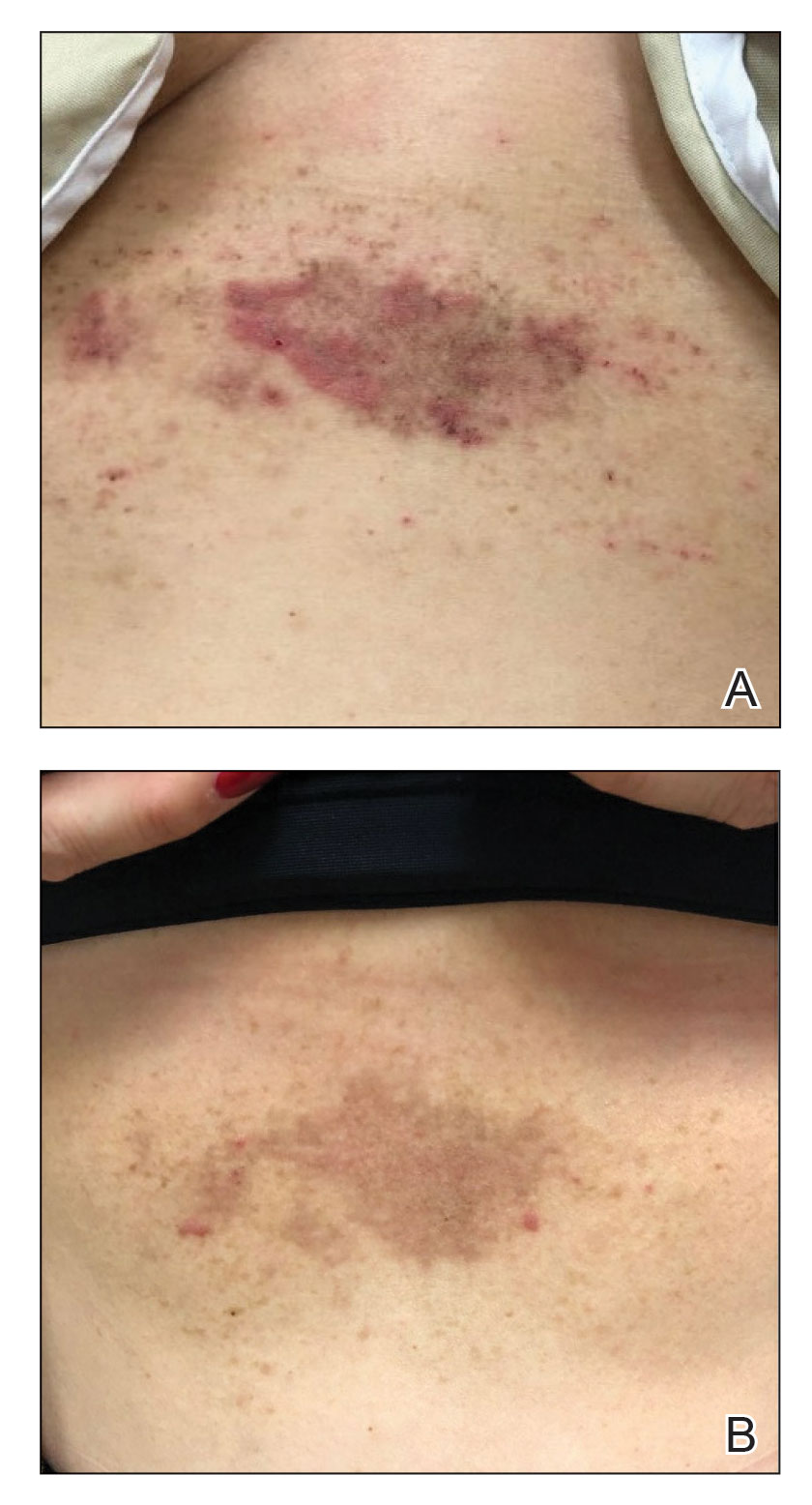

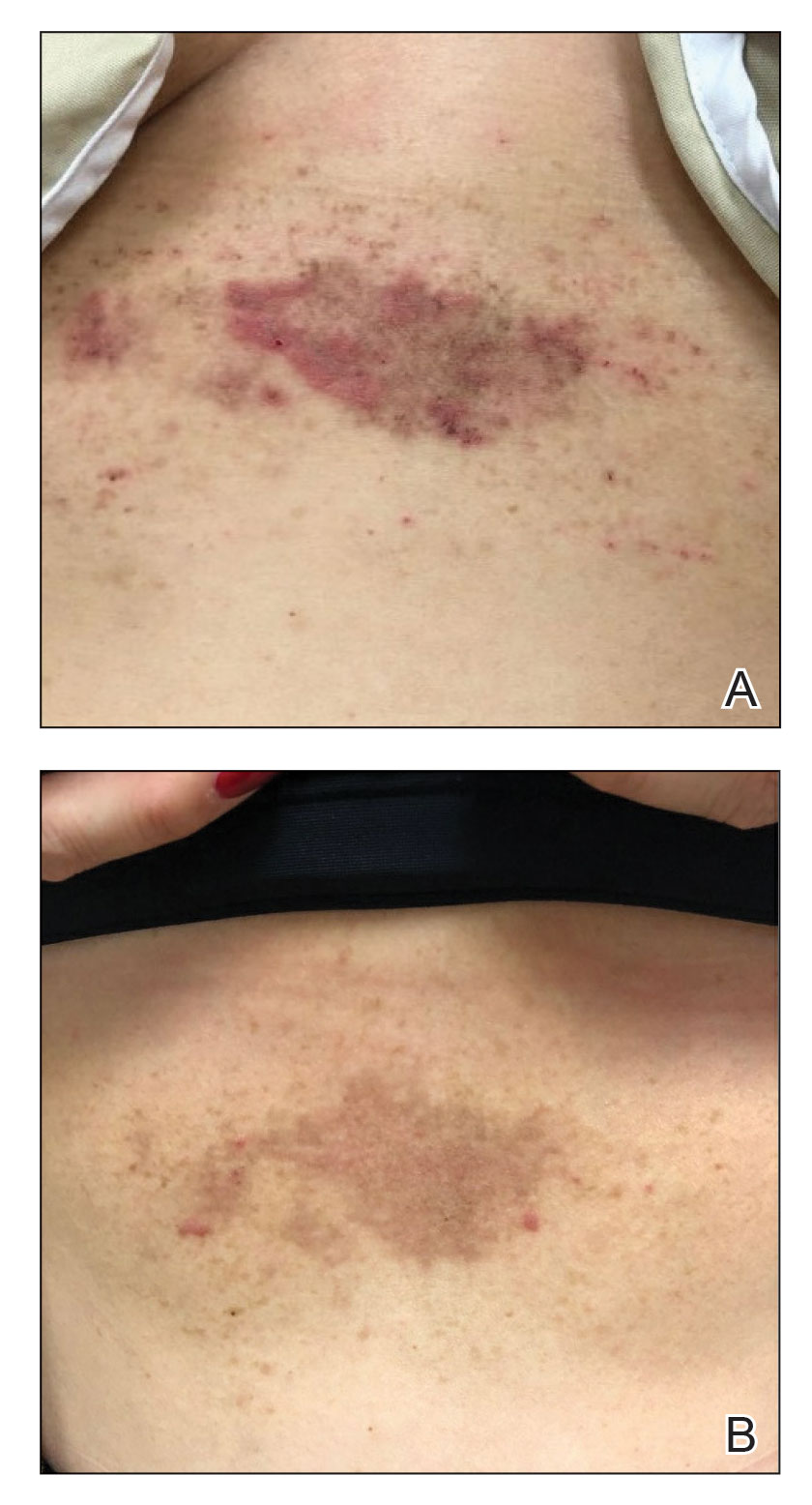

A 43-year-old woman presented with erythematous eroded plaques of the antecubital fossae, axillae, and chest (Figure 2A) of 10 years’ duration. A biopsy from an outside provider demonstrated findings consistent with a diagnosis of HHD. Prior therapies included topical and oral steroids. After a discussion of the risks and benefits, the patient was treated with onabotulinumtoxinA injections in combination with oral glycopyrrolate 5 mg daily. She received 30 U of onabotulinumtoxinA to each axilla, 10 U to each antecubital fossa, and 20 U to the central chest. At 1 month follow-up, the patient reported great improvement in lesion burden and active disease (Figure 2B). Nine months after treatment, her HHD was in complete remission with glycopyrrolate alone and she did not require further therapy with onabotulinumtoxinA.

Hailey-Hailey disease has been attributed to mutations of the ATPase secretory pathway Ca2+ transporting 1 gene, ATP2C1, that lead to aberrations in calcium signaling and subsequent impaired adhesion between keratinocytes.2 These compromised cell-cell connections are worsened by the presence of humidity, causing further acantholysis. Chemical denervation of the sweat glands with botulinum toxin has been postulated to improve HHD by reducing moisture in vulnerable areas. Our 2 cases add to the existing literature documenting tangible clinical results that correlate with this hypothesis.3-5

Our second case is unique in that the patient achieved rapid improvement using a combination of onabotulinumtoxinA and glycopyrrolate therapy. Both onabotulinumtoxinA and glycopyrrolate inhibit acetylcholine signaling that is required for sweat production; however, each drug exerts its effect on different zones of the cholinergic pathway, which may partially account for the synergistic effect of onabotulinumtoxinA and glycopyrrolate to improve HHD, as sweating is dually inhibited by the 2 drugs. Additionally, the combined local and systemic administration of these anticholinergic medications may further potentiate the sweat blockade, particularly in areas most prone to disease.

Botulinum toxin for the treatment of HHD is an effective monotherapy. The addition of an oral anticholinergic to local neuromodulator injections may speed symptom resolution and sustain disease remission. Further studies to evaluate this combination are warranted.

- Palmer DD, Perry HO. Benign familial chronic pemphigus. Arch Dermatol. 1962;86:493-502. doi:10.1001/archderm.1962.01590100107020

- Farahnik B, Blattner CM, Mortazie MB, et al. Interventional treatments for Hailey-Hailey disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:551-558.e553. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.08.039

- Bessa GR, Glaziovine TC, Manzoni AP, et al. Hailey-Hailey disease treatment with botulinum toxin type A. An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85:717-722. doi:10.1590/s0365-05962010000500021

- Lapiere JC, Hirsh A, Gordon KB, et al. Botulinum toxin type A for the treatment of axillary Hailey-Hailey disease. Dermatol Surg. 2000;26:371-374. doi:10.1046/j.1524-4725.2000.99278.x

- Koeyers WJ, Van Der Geer S, Krekels G. Botulinum toxin type A as an adjuvant treatment modality for extensive Hailey-Hailey disease. J Dermatolog Treat. 2008;19:251-254. doi:10.1080/09546630801955135

To the Editor:

Hailey-Hailey disease (HHD)(also known as familial benign chronic pemphigus) is an inherited autosomal-dominant condition in the family of chronic bullous diseases. It is characterized by flaccid blisters, erosions, and macerated vegetative plaques with a predilection for intertriginous sites. Lesions often are weeping, painful, pruritic, and malodorous, leading to decreased quality of life for patients. Complications of this chronic disease include an increased risk for secondary infection and malignant transformation to squamous cell carcinoma.1

Treatment of HHD remains difficult. Topical steroids, oral steroids, and ablative techniques such as dermabrasion and ablative lasers are the most widely reported therapies. OnabotulinumtoxinA has been described as a successful treatment for patients with HHD, including for disease recalcitrant to other therapies.2 We describe 2 patients with HHD who responded to treatment with intralesional onabotulinumtoxinA injections with and without adjuvant oral glycopyrrolate.

A 54-year-old woman presented with painful flaccid blisters under the breasts (Figure 1A) and in the axillae and groin of 3 weeks’ duration. Biopsy results from this initial visit were consistent with a diagnosis of HHD. The patient reported that the onset of blisters coincided with episodes of severe hyperhidrosis. Therapy with topical and oral steroids, antifungals, antibiotics, and topical aluminum chloride failed to achieve adequate disease control. After a discussion of the risks and benefits, the patient agreed to treatment with injections of onabotulinumtoxinA. At months 0, 3, and 6, the patient received 50 U of onabotulinumtoxinA under the breasts and in the axillae and the groin, for a total of 250 U each session. Each injection consisted of 2.5 U of onabotulinumtoxinA spaced 1-cm apart. Clinical improvement was noted within 2 weeks of initiating neuromodulator therapy. Follow-up at 9 months demonstrated improvement (Figure 1B); however, complete clearance was not achieved, and the patient required ongoing treatment with onabotulinumtoxinA every 3 months.

A 43-year-old woman presented with erythematous eroded plaques of the antecubital fossae, axillae, and chest (Figure 2A) of 10 years’ duration. A biopsy from an outside provider demonstrated findings consistent with a diagnosis of HHD. Prior therapies included topical and oral steroids. After a discussion of the risks and benefits, the patient was treated with onabotulinumtoxinA injections in combination with oral glycopyrrolate 5 mg daily. She received 30 U of onabotulinumtoxinA to each axilla, 10 U to each antecubital fossa, and 20 U to the central chest. At 1 month follow-up, the patient reported great improvement in lesion burden and active disease (Figure 2B). Nine months after treatment, her HHD was in complete remission with glycopyrrolate alone and she did not require further therapy with onabotulinumtoxinA.

Hailey-Hailey disease has been attributed to mutations of the ATPase secretory pathway Ca2+ transporting 1 gene, ATP2C1, that lead to aberrations in calcium signaling and subsequent impaired adhesion between keratinocytes.2 These compromised cell-cell connections are worsened by the presence of humidity, causing further acantholysis. Chemical denervation of the sweat glands with botulinum toxin has been postulated to improve HHD by reducing moisture in vulnerable areas. Our 2 cases add to the existing literature documenting tangible clinical results that correlate with this hypothesis.3-5

Our second case is unique in that the patient achieved rapid improvement using a combination of onabotulinumtoxinA and glycopyrrolate therapy. Both onabotulinumtoxinA and glycopyrrolate inhibit acetylcholine signaling that is required for sweat production; however, each drug exerts its effect on different zones of the cholinergic pathway, which may partially account for the synergistic effect of onabotulinumtoxinA and glycopyrrolate to improve HHD, as sweating is dually inhibited by the 2 drugs. Additionally, the combined local and systemic administration of these anticholinergic medications may further potentiate the sweat blockade, particularly in areas most prone to disease.

Botulinum toxin for the treatment of HHD is an effective monotherapy. The addition of an oral anticholinergic to local neuromodulator injections may speed symptom resolution and sustain disease remission. Further studies to evaluate this combination are warranted.

To the Editor:

Hailey-Hailey disease (HHD)(also known as familial benign chronic pemphigus) is an inherited autosomal-dominant condition in the family of chronic bullous diseases. It is characterized by flaccid blisters, erosions, and macerated vegetative plaques with a predilection for intertriginous sites. Lesions often are weeping, painful, pruritic, and malodorous, leading to decreased quality of life for patients. Complications of this chronic disease include an increased risk for secondary infection and malignant transformation to squamous cell carcinoma.1

Treatment of HHD remains difficult. Topical steroids, oral steroids, and ablative techniques such as dermabrasion and ablative lasers are the most widely reported therapies. OnabotulinumtoxinA has been described as a successful treatment for patients with HHD, including for disease recalcitrant to other therapies.2 We describe 2 patients with HHD who responded to treatment with intralesional onabotulinumtoxinA injections with and without adjuvant oral glycopyrrolate.

A 54-year-old woman presented with painful flaccid blisters under the breasts (Figure 1A) and in the axillae and groin of 3 weeks’ duration. Biopsy results from this initial visit were consistent with a diagnosis of HHD. The patient reported that the onset of blisters coincided with episodes of severe hyperhidrosis. Therapy with topical and oral steroids, antifungals, antibiotics, and topical aluminum chloride failed to achieve adequate disease control. After a discussion of the risks and benefits, the patient agreed to treatment with injections of onabotulinumtoxinA. At months 0, 3, and 6, the patient received 50 U of onabotulinumtoxinA under the breasts and in the axillae and the groin, for a total of 250 U each session. Each injection consisted of 2.5 U of onabotulinumtoxinA spaced 1-cm apart. Clinical improvement was noted within 2 weeks of initiating neuromodulator therapy. Follow-up at 9 months demonstrated improvement (Figure 1B); however, complete clearance was not achieved, and the patient required ongoing treatment with onabotulinumtoxinA every 3 months.

A 43-year-old woman presented with erythematous eroded plaques of the antecubital fossae, axillae, and chest (Figure 2A) of 10 years’ duration. A biopsy from an outside provider demonstrated findings consistent with a diagnosis of HHD. Prior therapies included topical and oral steroids. After a discussion of the risks and benefits, the patient was treated with onabotulinumtoxinA injections in combination with oral glycopyrrolate 5 mg daily. She received 30 U of onabotulinumtoxinA to each axilla, 10 U to each antecubital fossa, and 20 U to the central chest. At 1 month follow-up, the patient reported great improvement in lesion burden and active disease (Figure 2B). Nine months after treatment, her HHD was in complete remission with glycopyrrolate alone and she did not require further therapy with onabotulinumtoxinA.

Hailey-Hailey disease has been attributed to mutations of the ATPase secretory pathway Ca2+ transporting 1 gene, ATP2C1, that lead to aberrations in calcium signaling and subsequent impaired adhesion between keratinocytes.2 These compromised cell-cell connections are worsened by the presence of humidity, causing further acantholysis. Chemical denervation of the sweat glands with botulinum toxin has been postulated to improve HHD by reducing moisture in vulnerable areas. Our 2 cases add to the existing literature documenting tangible clinical results that correlate with this hypothesis.3-5

Our second case is unique in that the patient achieved rapid improvement using a combination of onabotulinumtoxinA and glycopyrrolate therapy. Both onabotulinumtoxinA and glycopyrrolate inhibit acetylcholine signaling that is required for sweat production; however, each drug exerts its effect on different zones of the cholinergic pathway, which may partially account for the synergistic effect of onabotulinumtoxinA and glycopyrrolate to improve HHD, as sweating is dually inhibited by the 2 drugs. Additionally, the combined local and systemic administration of these anticholinergic medications may further potentiate the sweat blockade, particularly in areas most prone to disease.

Botulinum toxin for the treatment of HHD is an effective monotherapy. The addition of an oral anticholinergic to local neuromodulator injections may speed symptom resolution and sustain disease remission. Further studies to evaluate this combination are warranted.

- Palmer DD, Perry HO. Benign familial chronic pemphigus. Arch Dermatol. 1962;86:493-502. doi:10.1001/archderm.1962.01590100107020

- Farahnik B, Blattner CM, Mortazie MB, et al. Interventional treatments for Hailey-Hailey disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:551-558.e553. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.08.039

- Bessa GR, Glaziovine TC, Manzoni AP, et al. Hailey-Hailey disease treatment with botulinum toxin type A. An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85:717-722. doi:10.1590/s0365-05962010000500021

- Lapiere JC, Hirsh A, Gordon KB, et al. Botulinum toxin type A for the treatment of axillary Hailey-Hailey disease. Dermatol Surg. 2000;26:371-374. doi:10.1046/j.1524-4725.2000.99278.x

- Koeyers WJ, Van Der Geer S, Krekels G. Botulinum toxin type A as an adjuvant treatment modality for extensive Hailey-Hailey disease. J Dermatolog Treat. 2008;19:251-254. doi:10.1080/09546630801955135

- Palmer DD, Perry HO. Benign familial chronic pemphigus. Arch Dermatol. 1962;86:493-502. doi:10.1001/archderm.1962.01590100107020

- Farahnik B, Blattner CM, Mortazie MB, et al. Interventional treatments for Hailey-Hailey disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:551-558.e553. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.08.039

- Bessa GR, Glaziovine TC, Manzoni AP, et al. Hailey-Hailey disease treatment with botulinum toxin type A. An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85:717-722. doi:10.1590/s0365-05962010000500021

- Lapiere JC, Hirsh A, Gordon KB, et al. Botulinum toxin type A for the treatment of axillary Hailey-Hailey disease. Dermatol Surg. 2000;26:371-374. doi:10.1046/j.1524-4725.2000.99278.x

- Koeyers WJ, Van Der Geer S, Krekels G. Botulinum toxin type A as an adjuvant treatment modality for extensive Hailey-Hailey disease. J Dermatolog Treat. 2008;19:251-254. doi:10.1080/09546630801955135

Practice Points

- Hailey-Hailey disease is associated with decreased quality of life for patients, and current treatment options are limited.

- A combination of local neuromodulator injections and systemic oral anticholinergic therapy may provide sustained disease remission compared to neuromodulator therapy alone.

Acquired Unilateral Nevoid Telangiectasia With Pruritus and Unknown Etiology

To the Editor:

Unilateral nevoid telangiectasia (UNT) is a rare cutaneous disease characterized by superficial telangiectases arranged in a unilateral linear pattern. First described by Alfred Blaschko in 1899, this rare disease has been reported in higher frequency in recent years, with approximately 100 cases published in the literature according to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the term unilateral nevoid telangiectasia.1 Unilateral nevoid telangiectasia can be congenital or acquired; occurs more commonly in women; and typically involves the dermatomal distributions of the trigeminal, cervical, and upper thoracic nerves. Although the pathogenesis of the disease remains unknown, the currently proposed etiology involves hyperestrogenic states, including puberty, pregnancy, and chronic liver disease.2 We report a case of progressively worsening, pruritic, unilateral telangiectases of unknown etiology.

A 55-year-old woman presented to our dermatology clinic with progressive red spots involving the right side of the upper body of 3 years’ duration. She noted pruritus, and the rash was otherwise asymptomatic. Her medical history was notable for hypertension, dyspepsia, sciatica, uterine fibroids, and a hysterectomy. Her medications included lisinopril, hydrochlorothiazide, tramadol, aspirin, and a multivitamin. The patient did not report the use of oral contraceptive pills or hormone replacement therapy. She also denied the use of cigarettes or illicit drugs but reported occasional alcohol consumption. A review of systems was negative for any constitutional symptoms or symptoms of liver disease. Her family history also was noncontributory.

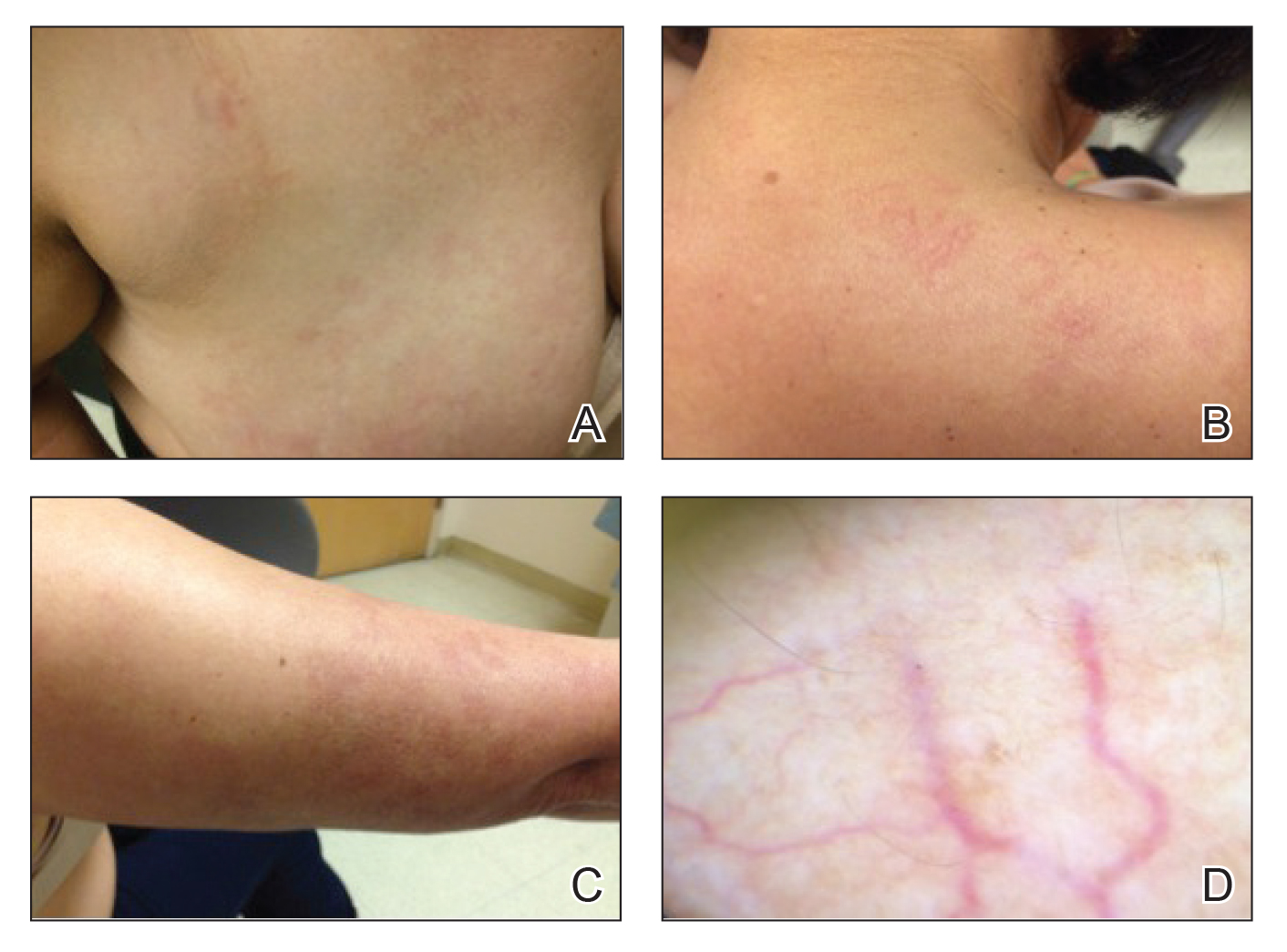

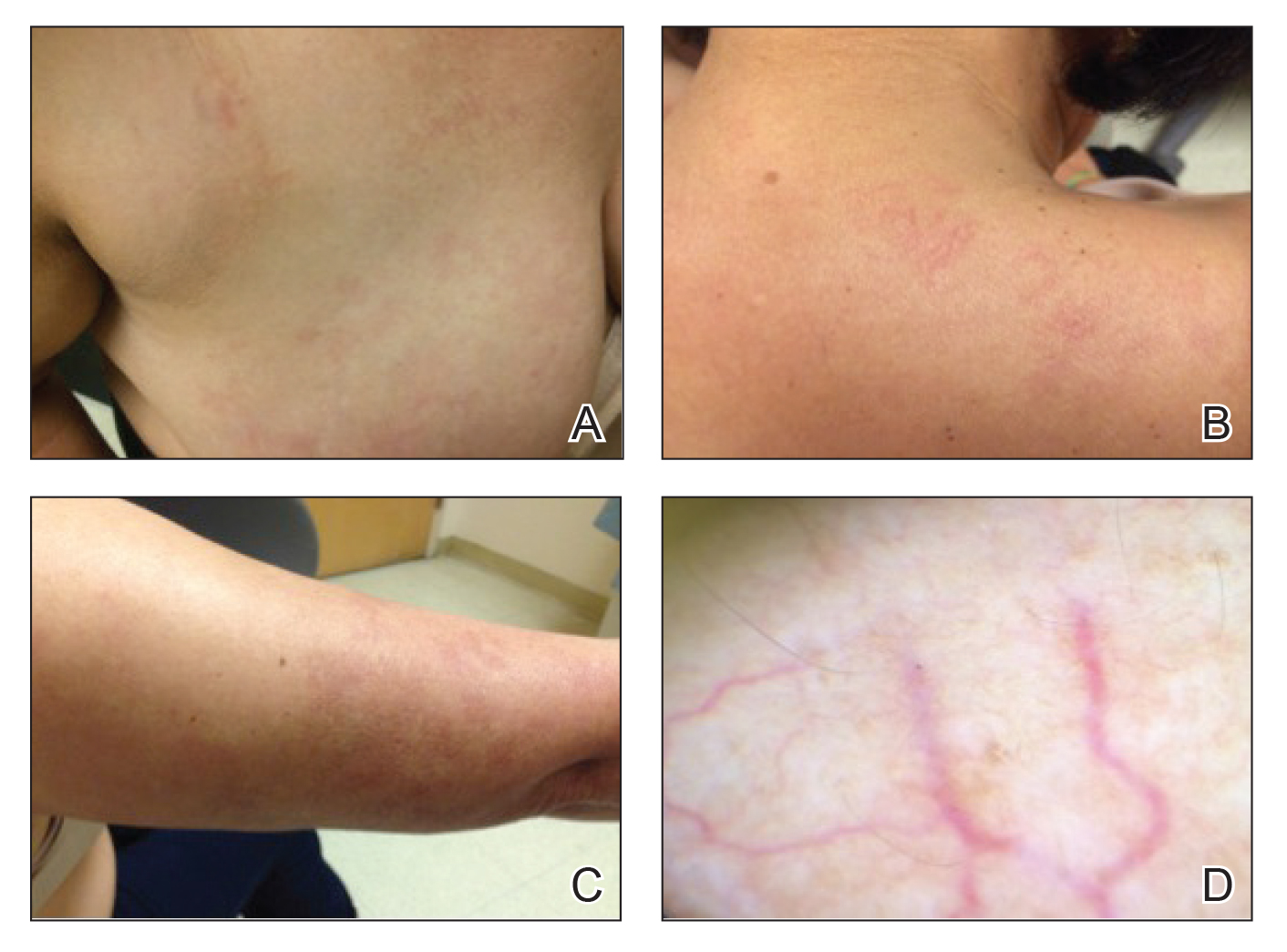

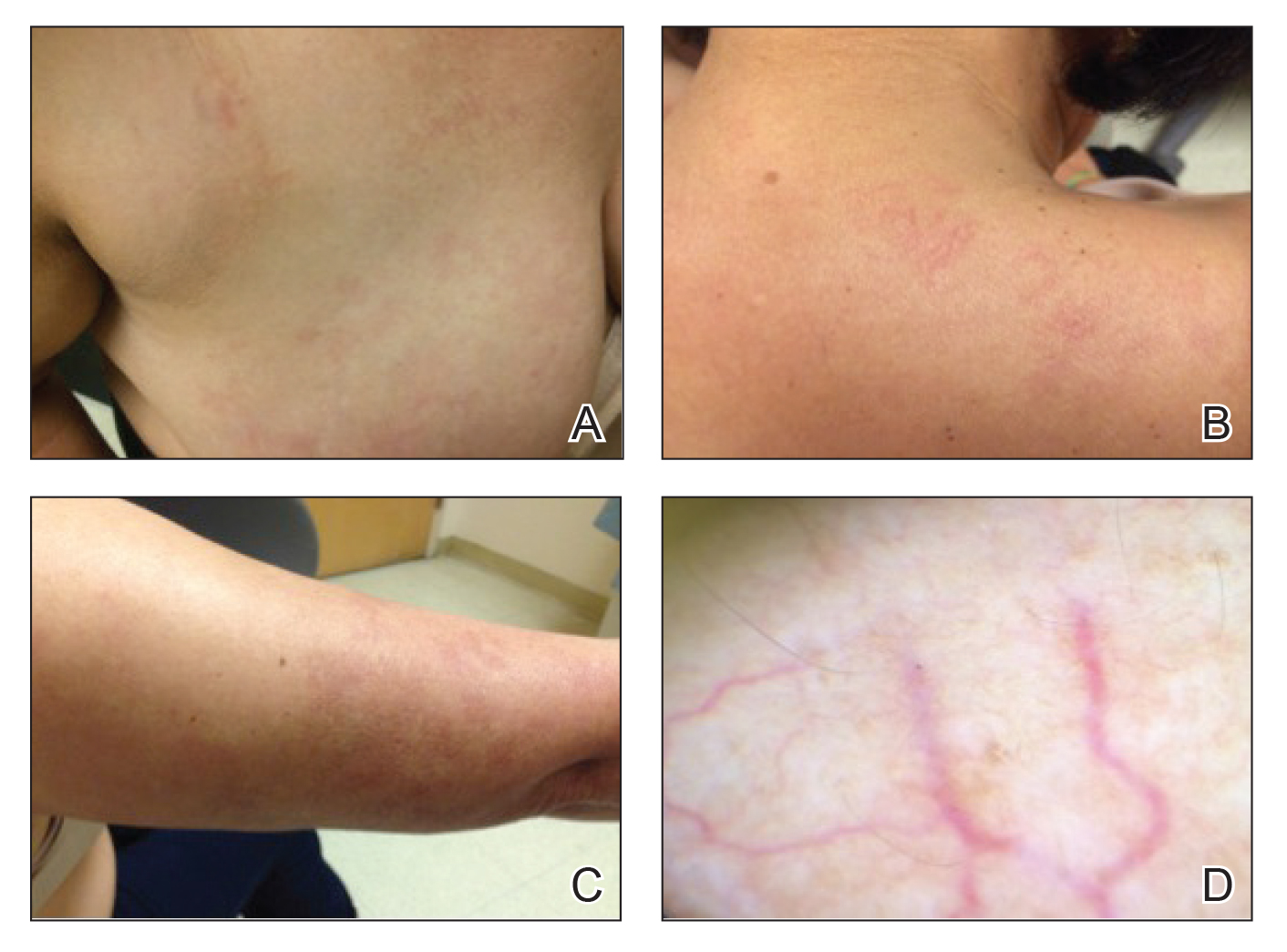

Physical examination revealed multiple, 1- to 3-mm, telangiectatic macules and patches in a blaschkoid distribution on the right side of the upper chest, back, shoulder, and arm (Figure, A–C). Darier sign was negative. There was no evidence of palmar erythema, hepatosplenomegaly, ascites, thyromegaly, or thyroid nodules. Dermoscopy confirmed the presence of telangiectasia (Figure, D). More specifically, dermoscopy revealed plump telangiectasia with faint pigment in the background, consistent with UNT. Additionally, there was no pink-white, shiny, scarlike background, and vessels were not thin or arborized, further supporting our diagnosis vs other entities included in the differential diagnosis.

Laboratory testing for estrogen levels was within normal postmenopausal limits. A complete blood cell count, basic metabolic panel, hepatic panel, and thyroid stimulating hormone levels all were within reference range. Hepatitis B and C virus testing was nonreactive. The diagnosis of UNT was made based on clinical characteristics. The patient then was referred for pulsed dye laser treatment.

Since the first reports of UNT in 1899, it has been described in multiple individually reported cases. The typical description of UNT involves linearly arranged telangiectasia of one side of the body, following either dermatomal or blaschkoid distribution, most commonly along the C3 and C4 dermatome. In 1970, Selmanowitz3 divided the diagnosis into 2 categories: congenital and acquired. The congenital form is less common overall, seen more frequently in males, and occurs in direct relation to the neonatal period.4 The acquired form that is more common overall and seen more frequently in females is suggested to be due to hyperestrogenic states. Most reports of the acquired form involve some underlying pathology that may lead to higher estrogen states. In a review article published in 2011, Wenson et al1 summarized the reported cases to date. The authors found that out of close to 100 cases reported, 26 acquired cases were associated with pregnancy and 23 with puberty. They further found 10 cases associated with hepatic disease, 2 associated with hormonal contraceptive pills, 1 associated with hyperthyroidism, and 1 associated with carcinoid syndrome.1Interestingly, a more varied presentation of disease has been reported, as cases are now being reported in healthy patients with no comorbidities or reasons for hyperestrogenism.5 In fact, presentations in healthy adult men have led some authors to believe that estrogen may not play a major role in the pathogenesis of the disease.5-8 Reports of 16 cases of UNT have indicated no association with hyperestrogenic states.1 Because the etiology remains unknown, individual cases both supporting and refuting the hypothesis of estrogen-driven vessel inflammation may drive the investigation of further explanations.

Because UNT usually is asymptomatic, treatment options are largely based on improvement in appearance of the lesions. The pulsed dye laser (PDL) has shown success in treatment of lesions, as Sharma et al,9 reported resolution of lesions in 9 cases. These cases were not without side effects, as some patients did experience reversible pigmentary changes. Other studies have validated the use of PDL for cosmetic improvement of UNT; however, some studies have noted the recurrence of lesions after treatment.10

Our case provides another unique presentation of UNT. Our patient was a healthy adult woman with no hyperestrogen-based etiology for disease. Importantly, our patient also represented a rare instance of UNT presenting with symptoms such as pruritus, though UNT classically is described as an asymptomatic phenomenon. In our patient, treatment with PDL was suggested and believed to be warranted not only for cosmetic improvement but also in light of the fact that her lesions were symptomatic.

- Wenson SF, Jan F, Sepehr A. Unilateral nevoid telangiectasia syndrome: a case report and review of the literature. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:2.

- Wilkin JK. Unilateral nevoid telangiectasia: three new cases and the role of estrogen. Arch Dermatol. 1977;113:486-488.

- Selmanowitz VJ. Unilateral nevoid telangiectasia. Ann Intern Med. 1970;73:87-90.

- Karakas¸ M, Durdu M, Sönmezog˘lu S, et al. Unilateral nevoid telangiectasia. J Dermatol. 2004;31:109-112.

- Jordão JM, Haendchen LC, Berestinas TC, et al. Acquired unilateral nevoid telangiectasia in a healthy men. An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85:912-914.

- Tas¸kapan O, Harmanyeri Y, Sener O, et al. Acquired unilateral nevoid telangiectasia syndrome. Acta Derm Venereol. 1997;77:62-63.

- Karabudak O, Dogan B, Taskapan O, et al. Acquired unilateral nevoid telangiectasia syndrome. J Dermatol. 2006;33:825-826.

- Jucas JJ, Rietschel RL, Lewis CW. Unilateral nevoid telangiectasia. Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:359-360.

- Sharma VK, Khandpur S. Unilateral nevoid telangiectasia—response to pulsed dye laser. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:960-964.

- Cliff S, Harland CC. Recurrence of unilateral naevoid telangiectatic syndrome following treatment with the pulsed dye laser. J Cutan Laser Ther. 1999;1:105-107.

To the Editor:

Unilateral nevoid telangiectasia (UNT) is a rare cutaneous disease characterized by superficial telangiectases arranged in a unilateral linear pattern. First described by Alfred Blaschko in 1899, this rare disease has been reported in higher frequency in recent years, with approximately 100 cases published in the literature according to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the term unilateral nevoid telangiectasia.1 Unilateral nevoid telangiectasia can be congenital or acquired; occurs more commonly in women; and typically involves the dermatomal distributions of the trigeminal, cervical, and upper thoracic nerves. Although the pathogenesis of the disease remains unknown, the currently proposed etiology involves hyperestrogenic states, including puberty, pregnancy, and chronic liver disease.2 We report a case of progressively worsening, pruritic, unilateral telangiectases of unknown etiology.

A 55-year-old woman presented to our dermatology clinic with progressive red spots involving the right side of the upper body of 3 years’ duration. She noted pruritus, and the rash was otherwise asymptomatic. Her medical history was notable for hypertension, dyspepsia, sciatica, uterine fibroids, and a hysterectomy. Her medications included lisinopril, hydrochlorothiazide, tramadol, aspirin, and a multivitamin. The patient did not report the use of oral contraceptive pills or hormone replacement therapy. She also denied the use of cigarettes or illicit drugs but reported occasional alcohol consumption. A review of systems was negative for any constitutional symptoms or symptoms of liver disease. Her family history also was noncontributory.

Physical examination revealed multiple, 1- to 3-mm, telangiectatic macules and patches in a blaschkoid distribution on the right side of the upper chest, back, shoulder, and arm (Figure, A–C). Darier sign was negative. There was no evidence of palmar erythema, hepatosplenomegaly, ascites, thyromegaly, or thyroid nodules. Dermoscopy confirmed the presence of telangiectasia (Figure, D). More specifically, dermoscopy revealed plump telangiectasia with faint pigment in the background, consistent with UNT. Additionally, there was no pink-white, shiny, scarlike background, and vessels were not thin or arborized, further supporting our diagnosis vs other entities included in the differential diagnosis.

Laboratory testing for estrogen levels was within normal postmenopausal limits. A complete blood cell count, basic metabolic panel, hepatic panel, and thyroid stimulating hormone levels all were within reference range. Hepatitis B and C virus testing was nonreactive. The diagnosis of UNT was made based on clinical characteristics. The patient then was referred for pulsed dye laser treatment.

Since the first reports of UNT in 1899, it has been described in multiple individually reported cases. The typical description of UNT involves linearly arranged telangiectasia of one side of the body, following either dermatomal or blaschkoid distribution, most commonly along the C3 and C4 dermatome. In 1970, Selmanowitz3 divided the diagnosis into 2 categories: congenital and acquired. The congenital form is less common overall, seen more frequently in males, and occurs in direct relation to the neonatal period.4 The acquired form that is more common overall and seen more frequently in females is suggested to be due to hyperestrogenic states. Most reports of the acquired form involve some underlying pathology that may lead to higher estrogen states. In a review article published in 2011, Wenson et al1 summarized the reported cases to date. The authors found that out of close to 100 cases reported, 26 acquired cases were associated with pregnancy and 23 with puberty. They further found 10 cases associated with hepatic disease, 2 associated with hormonal contraceptive pills, 1 associated with hyperthyroidism, and 1 associated with carcinoid syndrome.1Interestingly, a more varied presentation of disease has been reported, as cases are now being reported in healthy patients with no comorbidities or reasons for hyperestrogenism.5 In fact, presentations in healthy adult men have led some authors to believe that estrogen may not play a major role in the pathogenesis of the disease.5-8 Reports of 16 cases of UNT have indicated no association with hyperestrogenic states.1 Because the etiology remains unknown, individual cases both supporting and refuting the hypothesis of estrogen-driven vessel inflammation may drive the investigation of further explanations.

Because UNT usually is asymptomatic, treatment options are largely based on improvement in appearance of the lesions. The pulsed dye laser (PDL) has shown success in treatment of lesions, as Sharma et al,9 reported resolution of lesions in 9 cases. These cases were not without side effects, as some patients did experience reversible pigmentary changes. Other studies have validated the use of PDL for cosmetic improvement of UNT; however, some studies have noted the recurrence of lesions after treatment.10

Our case provides another unique presentation of UNT. Our patient was a healthy adult woman with no hyperestrogen-based etiology for disease. Importantly, our patient also represented a rare instance of UNT presenting with symptoms such as pruritus, though UNT classically is described as an asymptomatic phenomenon. In our patient, treatment with PDL was suggested and believed to be warranted not only for cosmetic improvement but also in light of the fact that her lesions were symptomatic.

To the Editor:

Unilateral nevoid telangiectasia (UNT) is a rare cutaneous disease characterized by superficial telangiectases arranged in a unilateral linear pattern. First described by Alfred Blaschko in 1899, this rare disease has been reported in higher frequency in recent years, with approximately 100 cases published in the literature according to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the term unilateral nevoid telangiectasia.1 Unilateral nevoid telangiectasia can be congenital or acquired; occurs more commonly in women; and typically involves the dermatomal distributions of the trigeminal, cervical, and upper thoracic nerves. Although the pathogenesis of the disease remains unknown, the currently proposed etiology involves hyperestrogenic states, including puberty, pregnancy, and chronic liver disease.2 We report a case of progressively worsening, pruritic, unilateral telangiectases of unknown etiology.

A 55-year-old woman presented to our dermatology clinic with progressive red spots involving the right side of the upper body of 3 years’ duration. She noted pruritus, and the rash was otherwise asymptomatic. Her medical history was notable for hypertension, dyspepsia, sciatica, uterine fibroids, and a hysterectomy. Her medications included lisinopril, hydrochlorothiazide, tramadol, aspirin, and a multivitamin. The patient did not report the use of oral contraceptive pills or hormone replacement therapy. She also denied the use of cigarettes or illicit drugs but reported occasional alcohol consumption. A review of systems was negative for any constitutional symptoms or symptoms of liver disease. Her family history also was noncontributory.

Physical examination revealed multiple, 1- to 3-mm, telangiectatic macules and patches in a blaschkoid distribution on the right side of the upper chest, back, shoulder, and arm (Figure, A–C). Darier sign was negative. There was no evidence of palmar erythema, hepatosplenomegaly, ascites, thyromegaly, or thyroid nodules. Dermoscopy confirmed the presence of telangiectasia (Figure, D). More specifically, dermoscopy revealed plump telangiectasia with faint pigment in the background, consistent with UNT. Additionally, there was no pink-white, shiny, scarlike background, and vessels were not thin or arborized, further supporting our diagnosis vs other entities included in the differential diagnosis.

Laboratory testing for estrogen levels was within normal postmenopausal limits. A complete blood cell count, basic metabolic panel, hepatic panel, and thyroid stimulating hormone levels all were within reference range. Hepatitis B and C virus testing was nonreactive. The diagnosis of UNT was made based on clinical characteristics. The patient then was referred for pulsed dye laser treatment.

Since the first reports of UNT in 1899, it has been described in multiple individually reported cases. The typical description of UNT involves linearly arranged telangiectasia of one side of the body, following either dermatomal or blaschkoid distribution, most commonly along the C3 and C4 dermatome. In 1970, Selmanowitz3 divided the diagnosis into 2 categories: congenital and acquired. The congenital form is less common overall, seen more frequently in males, and occurs in direct relation to the neonatal period.4 The acquired form that is more common overall and seen more frequently in females is suggested to be due to hyperestrogenic states. Most reports of the acquired form involve some underlying pathology that may lead to higher estrogen states. In a review article published in 2011, Wenson et al1 summarized the reported cases to date. The authors found that out of close to 100 cases reported, 26 acquired cases were associated with pregnancy and 23 with puberty. They further found 10 cases associated with hepatic disease, 2 associated with hormonal contraceptive pills, 1 associated with hyperthyroidism, and 1 associated with carcinoid syndrome.1Interestingly, a more varied presentation of disease has been reported, as cases are now being reported in healthy patients with no comorbidities or reasons for hyperestrogenism.5 In fact, presentations in healthy adult men have led some authors to believe that estrogen may not play a major role in the pathogenesis of the disease.5-8 Reports of 16 cases of UNT have indicated no association with hyperestrogenic states.1 Because the etiology remains unknown, individual cases both supporting and refuting the hypothesis of estrogen-driven vessel inflammation may drive the investigation of further explanations.

Because UNT usually is asymptomatic, treatment options are largely based on improvement in appearance of the lesions. The pulsed dye laser (PDL) has shown success in treatment of lesions, as Sharma et al,9 reported resolution of lesions in 9 cases. These cases were not without side effects, as some patients did experience reversible pigmentary changes. Other studies have validated the use of PDL for cosmetic improvement of UNT; however, some studies have noted the recurrence of lesions after treatment.10

Our case provides another unique presentation of UNT. Our patient was a healthy adult woman with no hyperestrogen-based etiology for disease. Importantly, our patient also represented a rare instance of UNT presenting with symptoms such as pruritus, though UNT classically is described as an asymptomatic phenomenon. In our patient, treatment with PDL was suggested and believed to be warranted not only for cosmetic improvement but also in light of the fact that her lesions were symptomatic.

- Wenson SF, Jan F, Sepehr A. Unilateral nevoid telangiectasia syndrome: a case report and review of the literature. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:2.

- Wilkin JK. Unilateral nevoid telangiectasia: three new cases and the role of estrogen. Arch Dermatol. 1977;113:486-488.

- Selmanowitz VJ. Unilateral nevoid telangiectasia. Ann Intern Med. 1970;73:87-90.

- Karakas¸ M, Durdu M, Sönmezog˘lu S, et al. Unilateral nevoid telangiectasia. J Dermatol. 2004;31:109-112.

- Jordão JM, Haendchen LC, Berestinas TC, et al. Acquired unilateral nevoid telangiectasia in a healthy men. An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85:912-914.

- Tas¸kapan O, Harmanyeri Y, Sener O, et al. Acquired unilateral nevoid telangiectasia syndrome. Acta Derm Venereol. 1997;77:62-63.

- Karabudak O, Dogan B, Taskapan O, et al. Acquired unilateral nevoid telangiectasia syndrome. J Dermatol. 2006;33:825-826.

- Jucas JJ, Rietschel RL, Lewis CW. Unilateral nevoid telangiectasia. Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:359-360.

- Sharma VK, Khandpur S. Unilateral nevoid telangiectasia—response to pulsed dye laser. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:960-964.

- Cliff S, Harland CC. Recurrence of unilateral naevoid telangiectatic syndrome following treatment with the pulsed dye laser. J Cutan Laser Ther. 1999;1:105-107.

- Wenson SF, Jan F, Sepehr A. Unilateral nevoid telangiectasia syndrome: a case report and review of the literature. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:2.

- Wilkin JK. Unilateral nevoid telangiectasia: three new cases and the role of estrogen. Arch Dermatol. 1977;113:486-488.

- Selmanowitz VJ. Unilateral nevoid telangiectasia. Ann Intern Med. 1970;73:87-90.

- Karakas¸ M, Durdu M, Sönmezog˘lu S, et al. Unilateral nevoid telangiectasia. J Dermatol. 2004;31:109-112.

- Jordão JM, Haendchen LC, Berestinas TC, et al. Acquired unilateral nevoid telangiectasia in a healthy men. An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85:912-914.

- Tas¸kapan O, Harmanyeri Y, Sener O, et al. Acquired unilateral nevoid telangiectasia syndrome. Acta Derm Venereol. 1997;77:62-63.

- Karabudak O, Dogan B, Taskapan O, et al. Acquired unilateral nevoid telangiectasia syndrome. J Dermatol. 2006;33:825-826.

- Jucas JJ, Rietschel RL, Lewis CW. Unilateral nevoid telangiectasia. Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:359-360.

- Sharma VK, Khandpur S. Unilateral nevoid telangiectasia—response to pulsed dye laser. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:960-964.

- Cliff S, Harland CC. Recurrence of unilateral naevoid telangiectatic syndrome following treatment with the pulsed dye laser. J Cutan Laser Ther. 1999;1:105-107.

Practice Points

- Unilateral nevoid telangiectasia may present in patients without an underlying hyperestrogenic state.

- Unilateral nevoid telangiectasia may present with symptoms including pruritus.

Pulmonary Hemorrhage as the Initial Presentation of AIDS-Related Kaposi Sarcoma

To the Editor:

Kaposi sarcoma (KS) is an angioproliferative tumor of endothelial origin associated with human herpesvirus 8 infection. It is one of the most prevalent opportunistic infections associated with AIDS and is considered an AIDS-defining illness. In the general population, the incidence of KS is 1 in 100,000 worldwide.1 At the onset of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) epidemic in the early 1980s, 25% of individuals with AIDS were found to have KS at the time of AIDS diagnosis. Beginning in the mid-1980s and early 1990s with the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), the incidence of KS declined to 2% to 4%,2 likely secondary to restoration of immune response.3

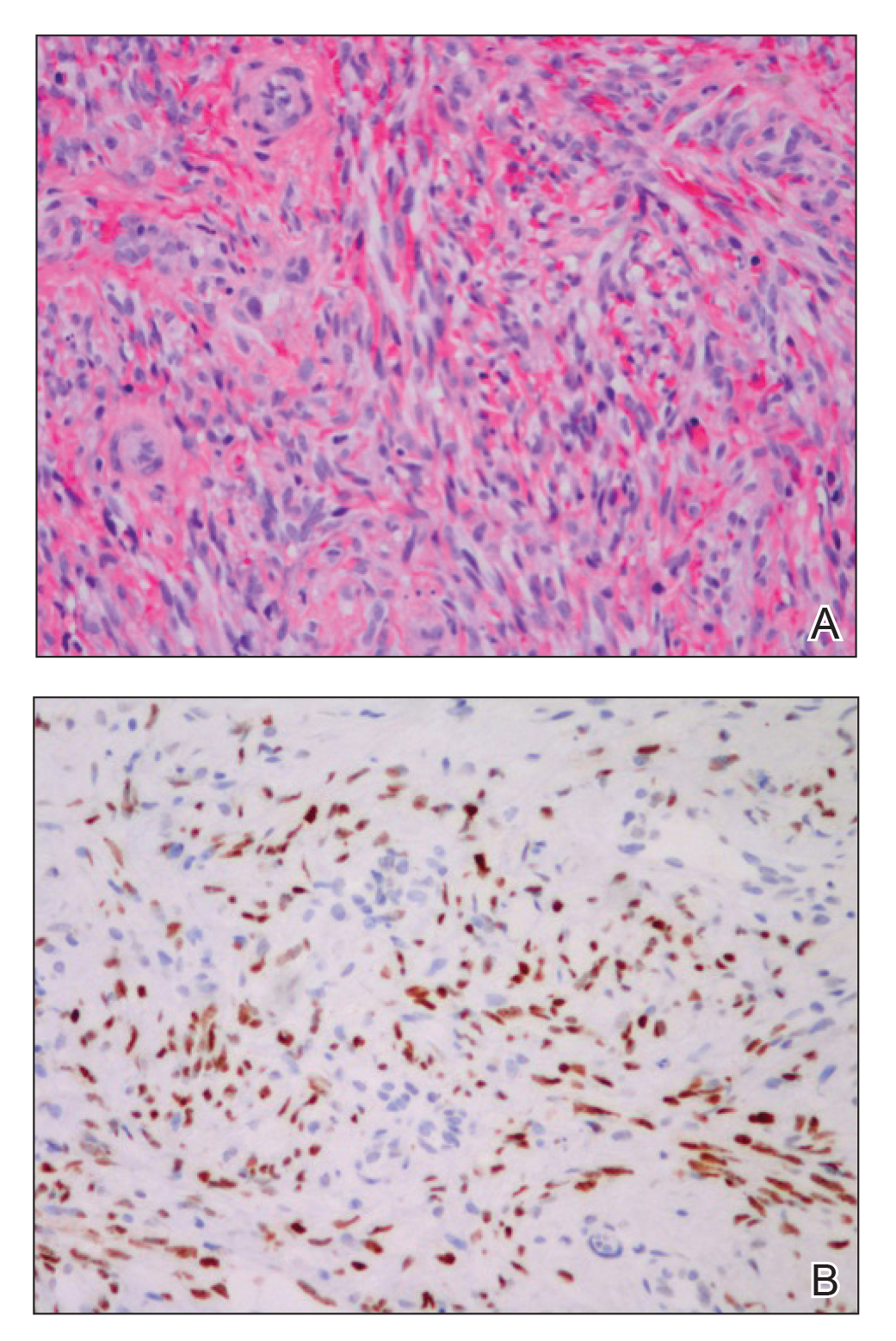

The clinical course of KS ranges from benign to severe, involving both cutaneous and visceral forms of disease. Cutaneous KS is the most common form of disease and typically characterizes the initial presentation. It is classically described as violaceous patches, papules, or plaques that can become confluent, forming larger tumors over time. Biopsy of cutaneous lesions may vary based on the clinical morphology. The patch stage typically is characterized by abnormal proliferating vessels surrounding larger ectatic vessels.4 Vascular spaces are more jagged and lined by thin endothelial cells extending into the dermis, forming the classic promontory sign.5 In the plaque stage, the vascular infiltrate becomes more diffuse, involving the dermis and subcutis, and there is proliferation of spindle cells.4 In the nodular stage, spindle-shaped tumor cells form fascicles and vascular spaces become more dilated.4,5 Advanced lesions are further associated with hyaline globules staining positive with periodic acid–Schiff.4 Lymphocytes, plasma cells, and hemosiderin-laden macrophages are admixed within this pathologic architecture.4,5

Visceral KS most commonly occurs in the oropharynx, respiratory tract, and gastrointestinal tract, and rarely is the initial presentation of disease. Classically, visceral KS is an aggressive, potentially life-threatening form of disease and has been found to have a much worse prognosis than cutaneous KS alone. Pulmonary involvement is the second most common site of extracutaneous KS and is known as the most severely life-threatening form of disease.1 Interestingly, since the advent of HAART, the incidence of KS with involvement of the visceral organs has declined at a more dramatic rate than cutaneous KS alone.3 Therefore, although more aggressive in nature, KS with visceral features has become increasingly rare and should be largely preventable given advances in AIDS therapy. We present a case of advanced AIDS-related KS with pulmonary involvement that is rarely seen after the advent of HAART.

A 39-year-old man with HIV diagnosed 8 years prior presented with fever, chest pain, progressive dyspnea, and hemoptysis of 5 months’ duration. At the time, he was nonadherent to medications and had poor follow-up with primary care physicians. At presentation he was tachycardic (149 beats per minute), tachypneic (26 breaths per minute), and his oxygen saturation was 80% on room air. Physical examination of the skin revealed asymptomatic violaceous penile lesions that the patient reported had been present for the last 8 months (Figure 1). Pertinent laboratory values included an HIV-1 viral load of 480,135 copies/mL (reference range, <20 copies/mL) and CD4 count of 14 cells/mm3 (reference range, 480–1700 cells/mm3). A chest radiograph was obtained and revealed bibasilar opacities compatible with a pleural and/or parenchymal process. Bronchoscopy was then performed and revealed bloody secretions throughout the tracheobronchial tree.

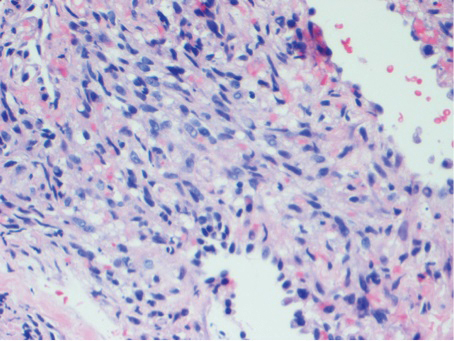

Histologic examination of biopsies of the penile lesions revealed spindle cell proliferation with hemorrhage (Figure 2A) that stained positively for HHV-8 (Figure 2B), consistent with KS. Biopsies taken during bronchoscopy similarly revealed spindle cells with hemorrhage (Figure 3). The patient was diagnosed with AIDS-related KS with visceral involvement of the lung parenchyma and tracheobronchial tree. The patient was then admitted to the medical intensive care unit and intubated. Therapy with HAART and paclitaxel was initiated. After 7 days of poor response to therapy, the family opted for terminal extubation and comfort care measures. The patient died hours later.

This case report describes the classic phenomenon of AIDS-related KS in a patient with a long-standing history of immunocompromise. Even in the era of HAART, this patient developed a severe form of visceral KS with involvement of the respiratory tract and lung parenchyma.

Since the advent of HAART for the treatment of HIV/AIDS, the incidence of KS, both visceral and cutaneous forms, has dramatically declined; the risk for visceral KS declined by more than 50% but less than 30% for cutaneous KS, supporting the observation that although visceral involvement has classically been noted as the more aggressive and life-threatening form of disease, HAART appears to have a stronger effect on visceral disease than cutaneous disease.3 Although the overall impact of AIDS-defining illnesses has substantially improved over the years, those with AIDS infection remain at risk for opportunistic illness.2

It has been shown that HAART therapy leads to response in more than 50% of cases of KS.5 The administration of HAART in KS patients is associated with improved survival and an 80% reduced risk of death, even when started after KS is diagnosed.6 In a comparison of the differences in clinical manifestations of KS between patients who were already receiving HAART at the time of KS diagnosis to those who were not on HAART, it was shown that patients already on therapy presented with less aggressive clinical features. A smaller percentage of patients who were already on HAART at KS diagnosis presented with visceral disease compared to those who were not on therapy.7

It is evident that treatment of AIDS patients with HAART is not only first-line therapy for the disease but also the best preventative measure against development of KS. Management of KS also centers around the initiation of HAART if the patient is not already maintained on the proper therapy.8 In addition to HAART, treatment options for visceral KS include a variety of chemotherapeutic agents, including but not limited to the use of single-agent adriamycin, vinblastine, paclitaxel, and thalidomide, or combination therapies.

Although notable advances have been made in the management of AIDS patients, this case highlights the need for clinicians to be aware of the risk for KS in the context of immunocompromise. Specifically, patients with advanced AIDS who are not adherent to HAART or who have a poor response to therapy have an amplified risk for developing KS in general as well as an increased risk for developing more severe visceral KS. Maintenance of patients with HAART is shown to greatly reduce the risk for both cutaneous and visceral KS; therefore, patient adherence with therapy is of utmost importance in preventing the occurrence of this deadly disease and its complications. Appropriate follow-up should be made, ensuring that these patients at high risk are adherent to therapy and have proper access to medical care to allow for prevention and early identification of potential complications.

- La Ferla L, Pinzone MR, Nunnari G, et al. Kaposi’s sarcoma in HIV-positive patients: the state of art in the HARRT-era. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2013;17:2354-2365.

- Engels EA, Pfeiffer RM, Goedert JJ, et al; HIV/AIDS Cancer Match Study. Trends in cancer risk among people with AIDS in the United States 1980-2002. AIDS. 2006;20:1645-1654.

- Grabar S, Abraham B, Mahamat A, et al. Differential impact of combination antiretroviral therapy in preventing Kaposi’s sarcoma with and without visceral involvement. JCO. 2006;24:3408-3414.

- Grayson W, Pantanowitz L. Histological variants of cutaneous Kaposi sarcoma [published online July 25, 2008]. Diagn Pathol. 2008;3:31.

- Radu O, Pantanowitz L. Kaposi sarcoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2013;137:289-294.

- Tam HK, Zhang ZF, Jacobson LP, et al. Effect of highly active antiretroviral therapy on survival among HIV-infected men with Kaposi sarcoma or non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Int J Cancer. 2002;98:916-922.

- Nasti G, Martellotta F, Berretta M, et al. Impact of highly active antiretroviral therapy on the presenting features and outcome of patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-related Kaposi sarcoma. Cancer. 2003;98:2440-2446.

- Dupont C, Vasseur E, Beauchet A, et al. Long-term efficacy on Kaposi’s sarcoma of highly active antriretroviral therapy in a cohort of HIV-positive patients. AIDS. 2000;14:987-993.

To the Editor:

Kaposi sarcoma (KS) is an angioproliferative tumor of endothelial origin associated with human herpesvirus 8 infection. It is one of the most prevalent opportunistic infections associated with AIDS and is considered an AIDS-defining illness. In the general population, the incidence of KS is 1 in 100,000 worldwide.1 At the onset of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) epidemic in the early 1980s, 25% of individuals with AIDS were found to have KS at the time of AIDS diagnosis. Beginning in the mid-1980s and early 1990s with the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), the incidence of KS declined to 2% to 4%,2 likely secondary to restoration of immune response.3

The clinical course of KS ranges from benign to severe, involving both cutaneous and visceral forms of disease. Cutaneous KS is the most common form of disease and typically characterizes the initial presentation. It is classically described as violaceous patches, papules, or plaques that can become confluent, forming larger tumors over time. Biopsy of cutaneous lesions may vary based on the clinical morphology. The patch stage typically is characterized by abnormal proliferating vessels surrounding larger ectatic vessels.4 Vascular spaces are more jagged and lined by thin endothelial cells extending into the dermis, forming the classic promontory sign.5 In the plaque stage, the vascular infiltrate becomes more diffuse, involving the dermis and subcutis, and there is proliferation of spindle cells.4 In the nodular stage, spindle-shaped tumor cells form fascicles and vascular spaces become more dilated.4,5 Advanced lesions are further associated with hyaline globules staining positive with periodic acid–Schiff.4 Lymphocytes, plasma cells, and hemosiderin-laden macrophages are admixed within this pathologic architecture.4,5

Visceral KS most commonly occurs in the oropharynx, respiratory tract, and gastrointestinal tract, and rarely is the initial presentation of disease. Classically, visceral KS is an aggressive, potentially life-threatening form of disease and has been found to have a much worse prognosis than cutaneous KS alone. Pulmonary involvement is the second most common site of extracutaneous KS and is known as the most severely life-threatening form of disease.1 Interestingly, since the advent of HAART, the incidence of KS with involvement of the visceral organs has declined at a more dramatic rate than cutaneous KS alone.3 Therefore, although more aggressive in nature, KS with visceral features has become increasingly rare and should be largely preventable given advances in AIDS therapy. We present a case of advanced AIDS-related KS with pulmonary involvement that is rarely seen after the advent of HAART.

A 39-year-old man with HIV diagnosed 8 years prior presented with fever, chest pain, progressive dyspnea, and hemoptysis of 5 months’ duration. At the time, he was nonadherent to medications and had poor follow-up with primary care physicians. At presentation he was tachycardic (149 beats per minute), tachypneic (26 breaths per minute), and his oxygen saturation was 80% on room air. Physical examination of the skin revealed asymptomatic violaceous penile lesions that the patient reported had been present for the last 8 months (Figure 1). Pertinent laboratory values included an HIV-1 viral load of 480,135 copies/mL (reference range, <20 copies/mL) and CD4 count of 14 cells/mm3 (reference range, 480–1700 cells/mm3). A chest radiograph was obtained and revealed bibasilar opacities compatible with a pleural and/or parenchymal process. Bronchoscopy was then performed and revealed bloody secretions throughout the tracheobronchial tree.

Histologic examination of biopsies of the penile lesions revealed spindle cell proliferation with hemorrhage (Figure 2A) that stained positively for HHV-8 (Figure 2B), consistent with KS. Biopsies taken during bronchoscopy similarly revealed spindle cells with hemorrhage (Figure 3). The patient was diagnosed with AIDS-related KS with visceral involvement of the lung parenchyma and tracheobronchial tree. The patient was then admitted to the medical intensive care unit and intubated. Therapy with HAART and paclitaxel was initiated. After 7 days of poor response to therapy, the family opted for terminal extubation and comfort care measures. The patient died hours later.

This case report describes the classic phenomenon of AIDS-related KS in a patient with a long-standing history of immunocompromise. Even in the era of HAART, this patient developed a severe form of visceral KS with involvement of the respiratory tract and lung parenchyma.

Since the advent of HAART for the treatment of HIV/AIDS, the incidence of KS, both visceral and cutaneous forms, has dramatically declined; the risk for visceral KS declined by more than 50% but less than 30% for cutaneous KS, supporting the observation that although visceral involvement has classically been noted as the more aggressive and life-threatening form of disease, HAART appears to have a stronger effect on visceral disease than cutaneous disease.3 Although the overall impact of AIDS-defining illnesses has substantially improved over the years, those with AIDS infection remain at risk for opportunistic illness.2

It has been shown that HAART therapy leads to response in more than 50% of cases of KS.5 The administration of HAART in KS patients is associated with improved survival and an 80% reduced risk of death, even when started after KS is diagnosed.6 In a comparison of the differences in clinical manifestations of KS between patients who were already receiving HAART at the time of KS diagnosis to those who were not on HAART, it was shown that patients already on therapy presented with less aggressive clinical features. A smaller percentage of patients who were already on HAART at KS diagnosis presented with visceral disease compared to those who were not on therapy.7

It is evident that treatment of AIDS patients with HAART is not only first-line therapy for the disease but also the best preventative measure against development of KS. Management of KS also centers around the initiation of HAART if the patient is not already maintained on the proper therapy.8 In addition to HAART, treatment options for visceral KS include a variety of chemotherapeutic agents, including but not limited to the use of single-agent adriamycin, vinblastine, paclitaxel, and thalidomide, or combination therapies.

Although notable advances have been made in the management of AIDS patients, this case highlights the need for clinicians to be aware of the risk for KS in the context of immunocompromise. Specifically, patients with advanced AIDS who are not adherent to HAART or who have a poor response to therapy have an amplified risk for developing KS in general as well as an increased risk for developing more severe visceral KS. Maintenance of patients with HAART is shown to greatly reduce the risk for both cutaneous and visceral KS; therefore, patient adherence with therapy is of utmost importance in preventing the occurrence of this deadly disease and its complications. Appropriate follow-up should be made, ensuring that these patients at high risk are adherent to therapy and have proper access to medical care to allow for prevention and early identification of potential complications.

To the Editor:

Kaposi sarcoma (KS) is an angioproliferative tumor of endothelial origin associated with human herpesvirus 8 infection. It is one of the most prevalent opportunistic infections associated with AIDS and is considered an AIDS-defining illness. In the general population, the incidence of KS is 1 in 100,000 worldwide.1 At the onset of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) epidemic in the early 1980s, 25% of individuals with AIDS were found to have KS at the time of AIDS diagnosis. Beginning in the mid-1980s and early 1990s with the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), the incidence of KS declined to 2% to 4%,2 likely secondary to restoration of immune response.3

The clinical course of KS ranges from benign to severe, involving both cutaneous and visceral forms of disease. Cutaneous KS is the most common form of disease and typically characterizes the initial presentation. It is classically described as violaceous patches, papules, or plaques that can become confluent, forming larger tumors over time. Biopsy of cutaneous lesions may vary based on the clinical morphology. The patch stage typically is characterized by abnormal proliferating vessels surrounding larger ectatic vessels.4 Vascular spaces are more jagged and lined by thin endothelial cells extending into the dermis, forming the classic promontory sign.5 In the plaque stage, the vascular infiltrate becomes more diffuse, involving the dermis and subcutis, and there is proliferation of spindle cells.4 In the nodular stage, spindle-shaped tumor cells form fascicles and vascular spaces become more dilated.4,5 Advanced lesions are further associated with hyaline globules staining positive with periodic acid–Schiff.4 Lymphocytes, plasma cells, and hemosiderin-laden macrophages are admixed within this pathologic architecture.4,5

Visceral KS most commonly occurs in the oropharynx, respiratory tract, and gastrointestinal tract, and rarely is the initial presentation of disease. Classically, visceral KS is an aggressive, potentially life-threatening form of disease and has been found to have a much worse prognosis than cutaneous KS alone. Pulmonary involvement is the second most common site of extracutaneous KS and is known as the most severely life-threatening form of disease.1 Interestingly, since the advent of HAART, the incidence of KS with involvement of the visceral organs has declined at a more dramatic rate than cutaneous KS alone.3 Therefore, although more aggressive in nature, KS with visceral features has become increasingly rare and should be largely preventable given advances in AIDS therapy. We present a case of advanced AIDS-related KS with pulmonary involvement that is rarely seen after the advent of HAART.

A 39-year-old man with HIV diagnosed 8 years prior presented with fever, chest pain, progressive dyspnea, and hemoptysis of 5 months’ duration. At the time, he was nonadherent to medications and had poor follow-up with primary care physicians. At presentation he was tachycardic (149 beats per minute), tachypneic (26 breaths per minute), and his oxygen saturation was 80% on room air. Physical examination of the skin revealed asymptomatic violaceous penile lesions that the patient reported had been present for the last 8 months (Figure 1). Pertinent laboratory values included an HIV-1 viral load of 480,135 copies/mL (reference range, <20 copies/mL) and CD4 count of 14 cells/mm3 (reference range, 480–1700 cells/mm3). A chest radiograph was obtained and revealed bibasilar opacities compatible with a pleural and/or parenchymal process. Bronchoscopy was then performed and revealed bloody secretions throughout the tracheobronchial tree.

Histologic examination of biopsies of the penile lesions revealed spindle cell proliferation with hemorrhage (Figure 2A) that stained positively for HHV-8 (Figure 2B), consistent with KS. Biopsies taken during bronchoscopy similarly revealed spindle cells with hemorrhage (Figure 3). The patient was diagnosed with AIDS-related KS with visceral involvement of the lung parenchyma and tracheobronchial tree. The patient was then admitted to the medical intensive care unit and intubated. Therapy with HAART and paclitaxel was initiated. After 7 days of poor response to therapy, the family opted for terminal extubation and comfort care measures. The patient died hours later.

This case report describes the classic phenomenon of AIDS-related KS in a patient with a long-standing history of immunocompromise. Even in the era of HAART, this patient developed a severe form of visceral KS with involvement of the respiratory tract and lung parenchyma.

Since the advent of HAART for the treatment of HIV/AIDS, the incidence of KS, both visceral and cutaneous forms, has dramatically declined; the risk for visceral KS declined by more than 50% but less than 30% for cutaneous KS, supporting the observation that although visceral involvement has classically been noted as the more aggressive and life-threatening form of disease, HAART appears to have a stronger effect on visceral disease than cutaneous disease.3 Although the overall impact of AIDS-defining illnesses has substantially improved over the years, those with AIDS infection remain at risk for opportunistic illness.2

It has been shown that HAART therapy leads to response in more than 50% of cases of KS.5 The administration of HAART in KS patients is associated with improved survival and an 80% reduced risk of death, even when started after KS is diagnosed.6 In a comparison of the differences in clinical manifestations of KS between patients who were already receiving HAART at the time of KS diagnosis to those who were not on HAART, it was shown that patients already on therapy presented with less aggressive clinical features. A smaller percentage of patients who were already on HAART at KS diagnosis presented with visceral disease compared to those who were not on therapy.7

It is evident that treatment of AIDS patients with HAART is not only first-line therapy for the disease but also the best preventative measure against development of KS. Management of KS also centers around the initiation of HAART if the patient is not already maintained on the proper therapy.8 In addition to HAART, treatment options for visceral KS include a variety of chemotherapeutic agents, including but not limited to the use of single-agent adriamycin, vinblastine, paclitaxel, and thalidomide, or combination therapies.

Although notable advances have been made in the management of AIDS patients, this case highlights the need for clinicians to be aware of the risk for KS in the context of immunocompromise. Specifically, patients with advanced AIDS who are not adherent to HAART or who have a poor response to therapy have an amplified risk for developing KS in general as well as an increased risk for developing more severe visceral KS. Maintenance of patients with HAART is shown to greatly reduce the risk for both cutaneous and visceral KS; therefore, patient adherence with therapy is of utmost importance in preventing the occurrence of this deadly disease and its complications. Appropriate follow-up should be made, ensuring that these patients at high risk are adherent to therapy and have proper access to medical care to allow for prevention and early identification of potential complications.

- La Ferla L, Pinzone MR, Nunnari G, et al. Kaposi’s sarcoma in HIV-positive patients: the state of art in the HARRT-era. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2013;17:2354-2365.

- Engels EA, Pfeiffer RM, Goedert JJ, et al; HIV/AIDS Cancer Match Study. Trends in cancer risk among people with AIDS in the United States 1980-2002. AIDS. 2006;20:1645-1654.

- Grabar S, Abraham B, Mahamat A, et al. Differential impact of combination antiretroviral therapy in preventing Kaposi’s sarcoma with and without visceral involvement. JCO. 2006;24:3408-3414.

- Grayson W, Pantanowitz L. Histological variants of cutaneous Kaposi sarcoma [published online July 25, 2008]. Diagn Pathol. 2008;3:31.

- Radu O, Pantanowitz L. Kaposi sarcoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2013;137:289-294.

- Tam HK, Zhang ZF, Jacobson LP, et al. Effect of highly active antiretroviral therapy on survival among HIV-infected men with Kaposi sarcoma or non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Int J Cancer. 2002;98:916-922.

- Nasti G, Martellotta F, Berretta M, et al. Impact of highly active antiretroviral therapy on the presenting features and outcome of patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-related Kaposi sarcoma. Cancer. 2003;98:2440-2446.

- Dupont C, Vasseur E, Beauchet A, et al. Long-term efficacy on Kaposi’s sarcoma of highly active antriretroviral therapy in a cohort of HIV-positive patients. AIDS. 2000;14:987-993.

- La Ferla L, Pinzone MR, Nunnari G, et al. Kaposi’s sarcoma in HIV-positive patients: the state of art in the HARRT-era. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2013;17:2354-2365.

- Engels EA, Pfeiffer RM, Goedert JJ, et al; HIV/AIDS Cancer Match Study. Trends in cancer risk among people with AIDS in the United States 1980-2002. AIDS. 2006;20:1645-1654.

- Grabar S, Abraham B, Mahamat A, et al. Differential impact of combination antiretroviral therapy in preventing Kaposi’s sarcoma with and without visceral involvement. JCO. 2006;24:3408-3414.

- Grayson W, Pantanowitz L. Histological variants of cutaneous Kaposi sarcoma [published online July 25, 2008]. Diagn Pathol. 2008;3:31.

- Radu O, Pantanowitz L. Kaposi sarcoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2013;137:289-294.

- Tam HK, Zhang ZF, Jacobson LP, et al. Effect of highly active antiretroviral therapy on survival among HIV-infected men with Kaposi sarcoma or non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Int J Cancer. 2002;98:916-922.

- Nasti G, Martellotta F, Berretta M, et al. Impact of highly active antiretroviral therapy on the presenting features and outcome of patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-related Kaposi sarcoma. Cancer. 2003;98:2440-2446.

- Dupont C, Vasseur E, Beauchet A, et al. Long-term efficacy on Kaposi’s sarcoma of highly active antriretroviral therapy in a cohort of HIV-positive patients. AIDS. 2000;14:987-993.

Practice Points

- Visceral Kaposi sarcoma (KS) should be considered in patients with unexplained systemic symptoms in the setting of poorly controlled human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).

- If cutaneous KS is diagnosed in an HIV patient, a detailed history and physical examination should be undertaken to evaluate for signs of systemic disease.