Chronic conditions like diabetes or hypertension “often require long-term care through long-term monitoring,” observed a researcher, and “we know that continuous monitoring is superior to intermittent monitoring for long-term outcomes.”

So maybe practice should rely more on continuous ECG monitoring for patients with atrial fibrillation (AFib), also a chronic condition, proposed Dhanunjaya R. Lakkireddy, MD, of the Kansas City Heart Rhythm Institute, Overland Park, Kan., in presenting a new analysis at the annual scientific sessions of the Heart Rhythm Society.

(ILRs), compared with standard care. The latter could include intermittent 12-lead ECG, Holter, or other intermittent monitoring at physicians’ discretion.

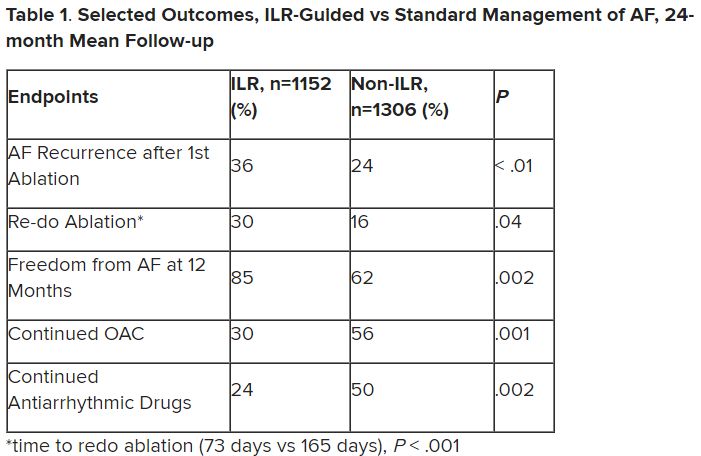

Patients with AFib and the ECG implants in the MONITOR-AF study, which was not randomized and therefore only suggestive, were managed “more efficiently” with greater access to electrophysiologists (P < .01) and adherence to oral anticoagulants (P = .020) and other medications.

Followed for a mean of 2 years, patients with ILRs were more likely to undergo catheter ablation, and their time to a catheter ablation “was impressively shorter, 153 days versus 426 days” (P < .001), Dr. Lakkireddy said.

The ILR group also had fewer strokes and bleeding complications and were less likely to be hospitalized for AFib-related reasons, he said, because “a lot of these patients were caught ahead of time through the remote monitoring.”

For example, ILR patients had fewer heart failure (HF) hospitalizations, likely because “you’re not allowing these patients to remain with untreated rapid ventricular rates for a long period of time. You intervene early, thereby mitigating the onset of heart failure.”

Indeed, Dr. Lakkireddy said, their cumulative rate of any cardiovascular complication was “dramatically lower” – 3.4 versus 10.4 events per 100 person-years (P < .001).

Certainly, a routine recommendation to consider AFib patients for continuous monitoring would require randomized-trial evidence, he acknowledged. “This is an observation registry and proof of concept from a very heterogeneous cohort of patients. There were no obvious set criteria for ILR implantation.”

Nonetheless, “continuous and dynamic monitoring enabled quicker decision-making and patient management,” Dr. Lakkireddy said. “Especially in those patients who may have silent atrial fibrillation, an ILR could significantly mitigate the risk of complications from stroke and heart failure exacerbations.”

Several randomized trials have supported “earlier, more aggressive treatment” for AFib, including EAST-AFNET4, EARLY-AF, and CABANA, observed Daniel Morin, MD, MPH, of Ochsner Medical Center, New Orleans, as the invited discussant for Dr. Lakkireddy’s presentation.

So, he continued, if the goal is to “get every single AFib patient to ablation just as soon as possible,” then maybe MONITOR-AF supports the use of ILRs in such cases.

Indeed, it is “certainly possible” that the continuous stream of data from ILRs “allows faster progression of therapy and possibly even better outcomes” as MONITOR-AF suggests, said Dr. Morin, who is director of electrophysiology research at his center.

Moreover, ILR data could potentially “support shared decision-making perhaps by convincing the patient, and maybe their insurers, that we should move forward with ablation.”

But given the study’s observational, registry-based nature, the MONITOR-AF analysis is limited by potential confounders that complicate its interpretation.

For example, Dr. Morin continued, all ILR patients but only 60% of those on standard care˙ had access to an electrophysiologist (P = .001). That means “less access to some antiarrhythmic medications and certainly far less access to ablation therapy.”

Moreover, “during shared decision-making, a patient who sees the results of their ILR monitoring may be more prone to seek out or to accept earlier, more definitive therapy via ablation,” he said. “The presence of an ILR may then be a good way to move the needle toward ablation.”

Of note, an overwhelming majority of ILR patients received ablation, 93.5%, compared with 58.6% of standard-care patients. “It’s unclear how much of that association was caused by the ILR’s presence vs. other factors, such as physician availability, physician aggressiveness, or patient willingness for intervention,” Dr. Morin noted.

MONITOR-AF included 2,458 patients with paroxysmal or persistent AFib who either were implanted with or did not receive an ILR from 2018 to 2021 and were followed for at least 12 months.

The two groups were similar, Dr. Lakkireddy reported, with respect to demographics and baseline history AFib, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, coronary disease, neurovascular events, peripheral artery disease, and obstructive sleep apnea.

Dr. Lakkireddy said a subgroup analysis is forthcoming, but that he’d “intuitively” think that the 15%-20% of AFib patients who are asymptomatic would gain the most from the ILR monitoring approach. There is already evidence that such patients tend to have the worst AFib outcomes, often receiving an AFib diagnosis only after presenting with consequences such as stroke or heart failure.

Dr. Lakkireddy disclosed receiving research grants, modest honoraria, or consulting fees from Abbott, Janssen, Boston Scientific, Johnson & Johnson, Biotronik, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pfizer, Atricure, Northeast Scientific, and Acutus. Dr. Morin disclosed receiving research grants, honoraria, or consulting fees from Abbott and serving on a speakers’ bureau for Boston Scientific, Medtronic, and Zoll Medical.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.