Treating TD and associated symptoms

Antibiotic treatment

Given that most cases of TD are caused by bacterial pathogens, antibiotics are considered the mainstay of treatment. Concerns about the ill effects of antibiotic use in the case of enterohemorrhagic E coli(EHEC O157:H7) can be allayed because this strain is rarely a cause of TD.9Patient factors that increase vulnerability to TD are immunodeficiency, achlorhydric states such as atrophic gastritis, and chronic use of proton pump inhibitors.

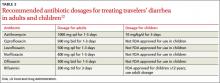

Consider local resistance patterns and risk of invasive infection. Which antibiotic to recommend is governed by the antibiotic resistance patterns prevalent in the travel destinations and by the risk of infection by invasive pathogens. Invasive TD is generally caused by Campylobacter, Shigella, or Salmonella and manifests clinically with bloody diarrhea, fever, or both. Rifaximin at a dose of 200 mg orally 3 times daily is effective for noninvasive TD.31,32 However, travelers who develop invasive TD need an alternative to rifaximin. (Those who advocate reserving antibiotic treatment only for invasive diarrhea will not see a role for rifaximin in the first place.) In most invasive cases, a fluoroquinolone will suffice.10-12,19,32 However, increasing prevalence of fluoroquinolone-resistantCampylobacter species has been reported in South and Southeast Asia. In those locations, azithromycin is an effective alternative, albeit with risk of nausea.33TABLE 212 provides details of recommended antibiotic dosages for adults and children. The duration of treatment is generally 1 day unless symptoms persist, in which case a 3-day course is recommended.10-12,19,32 If the traveler experiences persistent, new, or worsening symptoms beyond this point, immediate evaluation by a physician is required.

Non-antibiotic treatment

The antimotility agent loperamide is a well-established antidiarrheal agent. Its effective and safe use as an adjunct to antibiotics in the treatment of TD has been demonstrated in several studies.10-12,19,32,34 It is generally not used to treat children with TD9

No other non-antibiotic treatment for TD has significant guideline or clinical trial support. Bismuth subsalicylate can be helpful as an antidiarrheal agent,35 but is not often recommended because the regimen makes adherence difficult and because antibiotics and loperamide are effective.

Oral rehydration is usually a mainstay of treating gastrointestinal disease among infants and children. However, it, too, has a limited role in cases of TD because dehydration is not usually a significant part of the clinical presentation, perhaps because vomiting is not often prominent.

CASE Advice regarding safe food and beverage choices is essential for the patient and her children. Despite the increased risk for TD due to her history and her use of the immunosuppressant methotrexate, she decides not to pursue antibiotic prophylaxis. Bismuth is also contraindicated because of the methotrexate. Her teenage daughter declines bismuth prophylaxis, and her toddler is too young for it.

The patient does accept a prescription for azithromycin for her and her daughters in case they experience TD. This choice is appropriate given the destination of India and concern about Campylobacterresistance to fluoroquinolones. You also recommend loperamide for use by the mother and older child, in conjunction with the antibiotic.

Two weeks after their trip abroad, the travelers return for an office visit. On the trip, the mother and toddler suffered diarrhea, which responded well to your recommended management. The older child was well during the trip, but she developed diarrhea, abdominal pain, and anorexia one week after returning to the United States. These symptoms have persisted despite a 3-day course of azithromycin and loperamide.

Post-travel evaluation

TD generally occurs within one to 2 weeks of arrival at the travel destination and usually lasts no longer than 4 to 5 days.19 This scenario is typical of a bacterial infection. When it occurs later or lasts longer, or both, consider several alternative possibilities.19,36 First, the likelihood of a protozoal parasitic infection is increased. Although giardiasis is most likely, other protozoa such as Entamoeba, Cyclospora, Isospora, and Cryptosporidium are also possibilities. Second, if diarrhea persists, it might be due, not to continued infection, but to a self-limited post-infectious enteropathy or to PI-IBS. Third, TD is known to precipitate the clinical manifestation of underlying gastrointestinal disorders such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), celiac disease, or even cancer.37

With an atypical disease course, it’s advisable to send 3 stool samples for laboratory evaluation for ova and parasites and for antigen assays for Giardia. If results of these tests are negative, given the difficulty inherent in diagnosing Giardia, consider empiric treatment with metronidazole in lieu of duodenal sampling.36 If the diarrhea persists, investigate serologic markers for celiac disease and IBD. If these are not revealing, referral for colonoscopy is prudent.

CASE The teenager’s 3 stool samples were negative for ova and parasites and for Giardia antigen. Following empirical treatment with oral metronidazole 250 mg, 3 times daily for 7 days, the diarrhea resolved.