Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), a functional gastrointestinal disorder usually manifesting with abdominal pain and altered bowel movements, is often seen in primary care. With the recent advances in evidence-based knowledge, you can now more readily make a diagnosis and offer your patients with IBS a variety of treatment options tailored to their needs.

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is the most common gastrointestinal complaint seen in both primary and gastroenterology clinics.1 Direct and indirect costs associated with IBS total more than $20 billion. Studies have shown that patients with IBS consume 50% more health care resources than matched controls. The prevalence of IBS ranges from less than 1% to more than 20%. Using strict criteria, the pooled prevalence rate of IBS in North America is 7%.1

IBS occurs more commonly in women and lower socioeconomic populations and is more likely to be diagnosed before age 50.1 Individuals with IBS report diminished health-related quality of life (HRQOL) scores compared to those without the disease. In some cases, decreased HRQOL can be severe, resulting in increased risk for suicidal behavior.1

The pathogenesis of IBS is not entirely understood. Contributing factors may include impaired gastrointestinal motility, visceral hypersensitivity, increased mucosal permeability, carbohydrate malabsorption, bacterial overgrowth, altered brain-gut axis, altered intestinal microbiota, psychosocial disturbances, and genetic predisposition.1,2

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

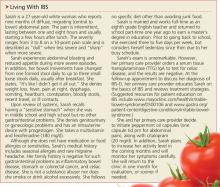

Hallmark symptoms of IBS are abdominal pain, dyspepsia, and altered bowel movements. The abdominal pain of IBS can be located anywhere and can range in severity from “annoying” to “debilitating” (see “Living with IBS,”). Eating and stress may aggravate pain, and a bowel movement may attenuate it. The pain is usually intermittent throughout the day; nocturnal pain is unusual and suggests an alternate cause.3

Dyspepsia (epigastric discomfort, postprandial fullness, early satiety) can occur in up to 87% of patients with IBS.4 Other features associated with IBS include gastroesophageal reflux disease nausea; noncardiac chest pain; bloating, belching and/or flatulence; sexual dysfunction; dyspareunia; urinary frequency and urgency; and fibromyalgia.

The patient with IBS will also experience a change in the type of bowel movement. Therefore, IBS is often categorized according to the predominant change: diarrhea (known as IBS-D), constipation (IBS-C), and alternating diarrhea and constipation (IBS-M). IBS-D is defined by diarrhea that is typically small to moderate in volume, occurs after meals or in the morning, and is associated with mucus 50% of the time.4 IBS-C is characterized by constipation with stools that are typically hard and pelletlike, accompanied by straining, with fewer than three bowel movements per week.

Patients with IBS may describe a sense of incomplete evacuation.4 Alarm signs and symptoms, which include progressive symptoms; nocturnal symptoms; weight loss, malnutrition, and anorexia; stools that are large in volume, bloody, or greasy; anemia, electrolyte disturbance, and elevated inflammatory markers; or a family history of inflammatory bowel disease, colorectal cancer, or celiac disease, should prompt evaluation for alternate etiologies.1,4

Continued on next page >>