User login

INTRODUCTION

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most prevalent malignancies and is the fourth most common cancer in the United States, with an estimated 133,490 new cases diagnosed in 2016. Of these, approximately 95,520 are located in the colon and 39,970 are in the rectum.1 CRC is the third leading cause of cancer death in women and the second leading cause of cancer death in men, with an estimated 49,190 total deaths in 2016.2 The incidence appears to be increasing,3 especially in patients younger than 55 years of age;4 the reason for this increase remains uncertain.

A number of risk factors for the development of CRC have been identified. Numerous hered-itary CRC syndromes have been described, including familial adenomatous polyposis,5 hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC) or Lynch syndrome,6 and MUTYH-associated polyposis.7,8 A family history of CRC doubles the risk of developing CRC,9 and current guidelines support lowering the age of screening in individuals with a family history of CRC to 10 years younger than the age of diagnosis of the family member or 40 years of age, whichever is lower.10 Patients with a personal history of adenomatous polyps are at increased risk for developing CRC, as are patients with a personal history of CRC, with a relative risk ranging from 3 to 6.11 Ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease are associated with the development of CRC and also influence screening, though evidence suggests good control of these diseases may mitigate risk.12 Finally, modifiable risk factors for the development of CRC include high red meat consumption,13 diets low in fiber,14 obesity,13 smoking, alcohol use,15 and physical inactivity16; lifestyle modification targeting these factors has been shown to decrease rates of CRC.17 The majority of colon cancers present with clinical symptoms, often with rectal bleeding, abdominal pain, change in bowel habits, or obstructive symptoms. More rarely, these tumors are detected during screening colonoscopy, in which case they tend to be at an early stage.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

A critical goal in the resection of early-stage colon cancer is attaining R0 resection. Patients who achieve R0 resection as compared to R1 (microscopic residual tumor) and R2 (macroscopic residual tumor)18 have significantly improved long-term overall survival.19 Traditionally, open resection of the involved colonic segment was employed, with end-end anastomosis of the uninvolved free margins. Laparoscopic resection for early-stage disease has been utilized in attempts to decrease morbidity of open procedures, with similar outcomes and node sampling.20 Laparoscopic resection appears to provide similar outcomes even in locally advanced disease.21 Right-sided lesions are treated with right colectomy and primary ileocolic anastomosis.22 For patients presenting with obstructing masses, the Hartmann procedure is the most commonly performed operation. This involves creation of an ostomy with subtotal colectomy and subsequent ostomy reversal in a 2- or 3-stage protocol.23 Patients with locally advanced disease and invasion into surrounding structures require multivisceral resection, which involves resection en bloc with secondarily involved organs.24 Intestinal perforation presents a unique challenge and is associated with surgical complications, infection, and lower overall survival (OS) and 5-year disease-free survival (DFS). Complete mesocolic excision is a newer technique that has been performed with reports of better oncologic outcome at some centers; however, this approach is not currently considered standard of care.25

STAGING

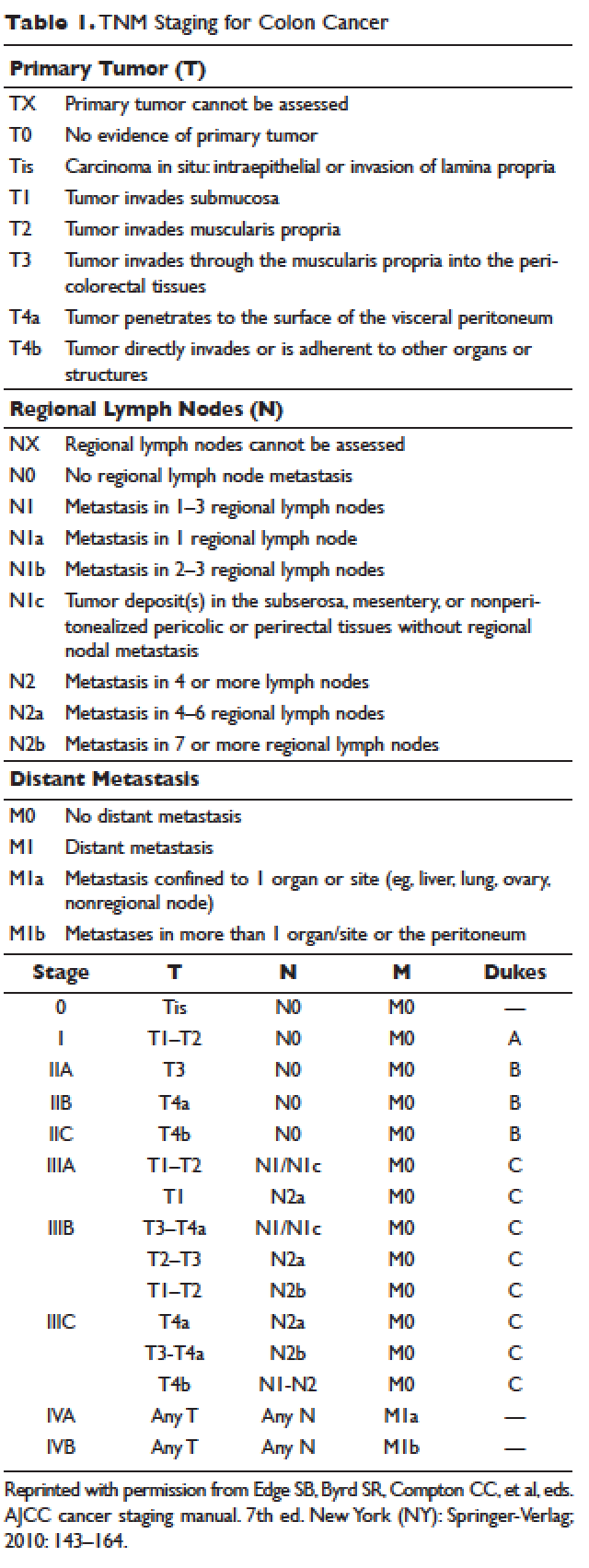

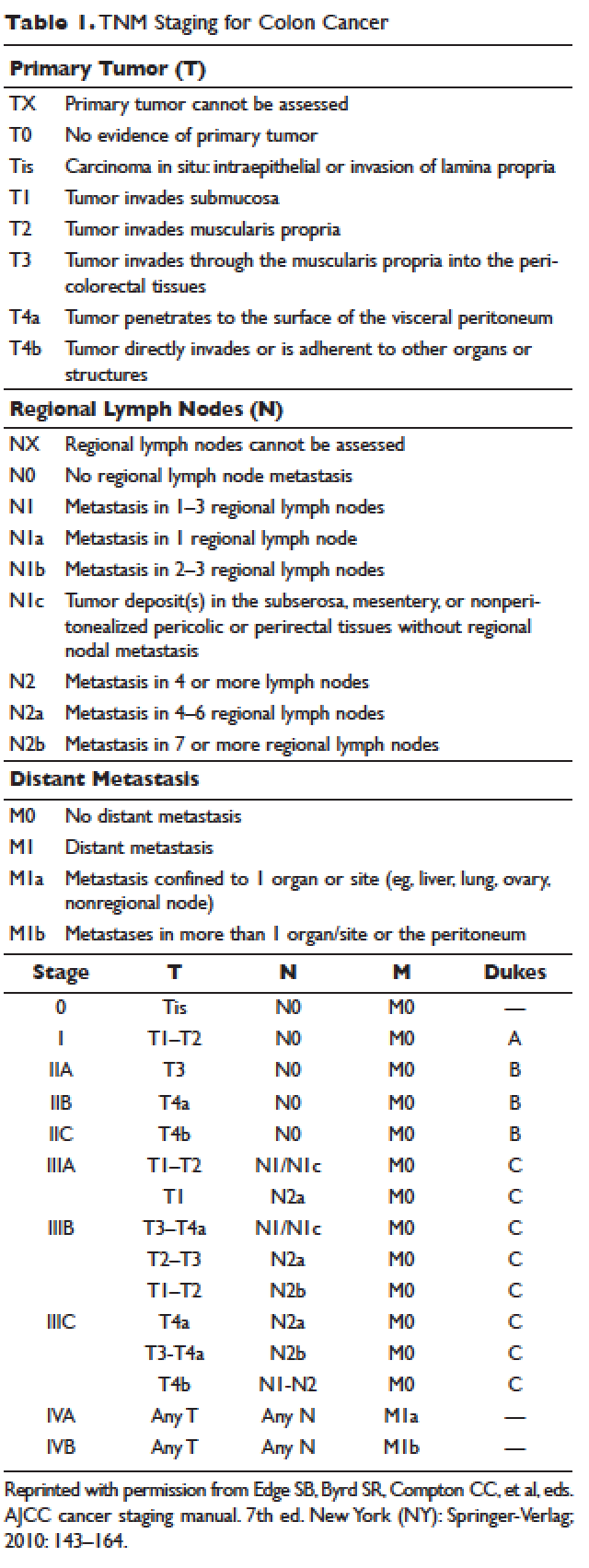

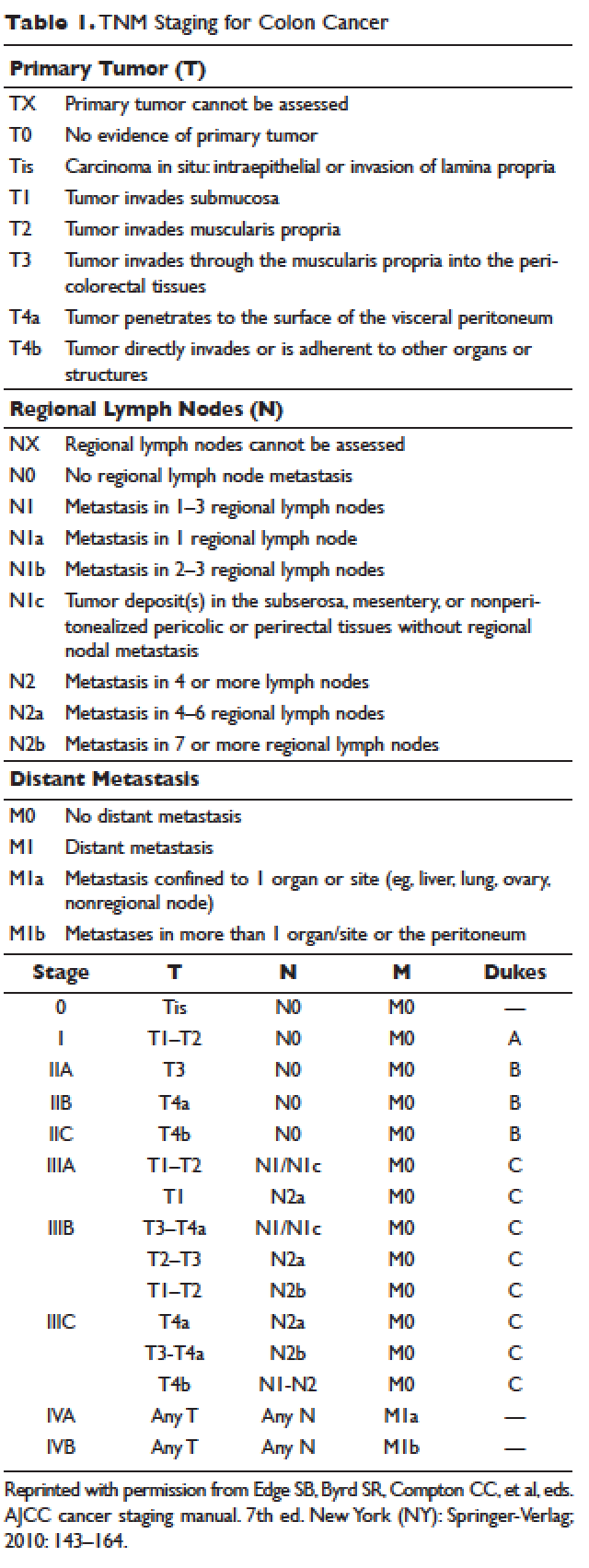

According to a report by the National Cancer Institute, the estimated 5-year relative survival rates for localized colon cancer (lymph node negative), regional (lymph node positive) disease, and distant (metastatic) disease are 89.9%, 71.3%, and 13.9%, respectively.1 However, efforts have been made to further classify patients into distinct categories to allow fine-tuning of prognostication. In the current system, staging of colon cancer utilizes the American Joint Committee on Cancer tumor/node/metastasis (TNM) system.20 Clinical and pathologic features include depth of invasion, local invasion of other organs, nodal involvement, and presence of distant metastasis (Table 1). Studies completed prior to the adoption of the TNM system used the Dukes criteria, which divided colon cancer into A, B, and C, corresponding to TNM stage I, stage IIA–IIC, and stage IIIA-IIIC. This classification is rarely used in more contemporary studies.

APPROACH TO ADJUVANT CHEMOTHERAPY

Adjuvant chemotherapy seeks to eliminate micrometastatic disease present following curative surgical resection. When stage 0 cancer is discovered incidentally during colonoscopy, endoscopic resection alone is the management of choice, as presence of micrometastatic disease is exceedingly unlikely.26 Stage I–III CRCs are treated with surgical resection withcurative intent. The 5-year survival rate for stage I and early-stage II CRC is estimated at 97% with surgery alone.27,28 The survival rate drops to about 60% for high-risk stage II tumors (T4aN0), and down to 50% or less for stage II-T4N0 or stage III cancers. Adjuvant chemotherapy is generally recommended to further decrease the rates of distant recurrence in certain cases of stage II and in all stage III tumors.

DETERMINATION OF BENEFIT FROM CHEMOTHERAPY: PROGNOSTIC MARKERS

Prior to administration of adjuvant chemotherapy, a clinical evaluation by the medical oncologist to determine appropriateness and safety of treatment is paramount. Poor performance status and comorbid conditions may indicate risk for excessive toxicity and minimal benefit from chemotherapy. CRC commonly presents in older individuals, with the median age at diagnosis of 69 years for men and 73 years for women.29 In this patient population, comorbidities such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and renal dysfunction are more prevalent.30 Decisions regarding adjuvant chemotherapy in this patient population have to take into consideration the fact that older patients may experience higher rates of toxicity with chemotherapy, including gastrointestinal toxicities and marrow suppression.31 Though some reports indicate patients older than 70 years derive similar benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy,32,33 a large pooled analysis of the ACCENT database, which included 7 adjuvant therapy trials and 14,528 patients, suggested limited benefit from the addition of oxaliplatin to fluorouracil in elderly patients.32 Other factors that weigh on the decision include stage, pathology, and presence of high-risk features. A common concern in the postoperative setting is delaying initiation of chemotherapy to allow adequate wound healing; however, evidence suggests that delays longer than 8 weeks leads to worse overall survival, with hazard ratios (HR) ranging from 1.4 to 1.7.34,35 Thus, the start of adjuvant therapy should ideally be within this time frame.

HIGH-RISK FEATURES

Multiple factors have been found to predict worse outcome and are classified as high-risk features (Table 2). Histologically, high-grade or poorly differentiated tumors are associated with higher recurrence rate and worse outcome.36 Certain histological subtypes, including mucinous and signet-ring, both appear to have more aggressive biology.37 Presence of microscopic invasion into surrounding blood vessels (vascular invasion) and nerves (perineural invasion) is associated with lower survival.38 Penetration of the cancer through the visceral peritoneum (T4a) or into surrounding structures (T4b) is associated with lower survival.36 During surgical resection, multiple lymph nodes are removed along with the primary tumor to evaluate for metastasis to the regional nodes. Multiple analyses have demonstrated that removal and pathologic assessment of fewer than 12 lymph nodes is associated with high risk of missing a positive node, and is thus equated with high risk.39–41 In addition, extension of tumor beyond the capsules of any single lymph node, termed extracapsular extension, is associated with an increased risk of all-cause mortality.42 Tumor deposits, or focal aggregates of adenocarcinoma in the pericolic fat that are not contiguous with the primary tumor and are not associated with lymph nodes, are currently classified as lymph nodes as N1c in the current TNM staging system. Presence of these deposits has been found to predict poor outcome stage for stage.43 Obstruction and/or perforation secondary to the tumor are also considered high-risk features that predict poor outcome.

SIDEDNESS

As reported at the 2016 American Society of Clinical Oncology annual meeting, tumor location predicts outcome in the metastatic setting. A report by Venook and colleagues based on a post-hoc analysis found that in the metastatic setting, location of the tumor primary in the left side is associated with longer OS (33.3 months) when compared to the right side of the colon (19.4 months).44 A retrospective analysis of multiple databases presented by Schrag and colleagues similarly reported inferior outcomes in patients with stage III and IV disease who had right-sided primary tumors.45 However, the prognostic implications for stage II disease remain uncertain.

BIOMARKERS

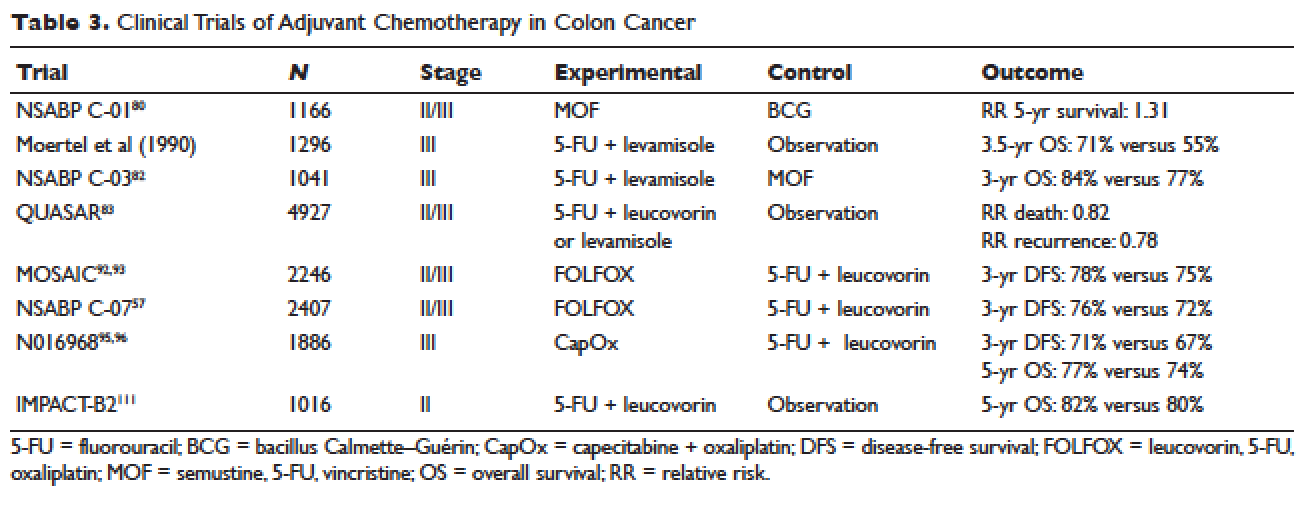

Given the controversy regarding adjuvant therapy of patients with stage II colon cancer, multiple biomarkers have been evaluated as possible predictive markers that can assist in this decision. The mismatch repair (MMR) system is a complex cellular enzymatic mechanism that identifies and corrects DNA errors during cell division and prevents mutagenesis.46 The familial cancer syndrome HNPCC is linked to alteration in a variety of MMR genes, leading to deficient mismatch repair (dMMR), also termed microsatellite instability-high (MSI-high).47,48 Epigenetic modification can also lead to silencing of the same implicated genes and accounts for 15% to 20% of sporadic colorectal cancer.49 These epigenetic modifications lead to hypermethylation of the promotor region of MLH1 in 70% of cases.50 The 4 MMR genes most commonly tested are MLH-1, MSH2, MSH6, and PMS2. Testing can be performed by immunohistochemistry or polymerase chain reaction.51 Across tumor histology and stage, MSI status is prognostic. Patients with MSI-high tumors have been shown to have improved prognosis and longer OS both in stage II and III disease52–54 and in the metastatic setting.55 However, despite this survival benefit, there is conflicting data as to whether patients with stage II, MSI-high colon cancer may benefit less from adjuvant chemotherapy. One early retrospective study compared outcomes of 70 patients with stage II and III disease and dMMR to those of 387 patients with stage II and III disease and proficient mismatch repair (pMMR). Adjuvant fluorouracil with leucovorin improved DFS for patients with pMMR (HR 0.67) but not for those with dMMR (HR 1.10). In addition, for patients with stage II disease and dMMR, the HR for OS was inferior at 2.95.56 Data collected from randomized clinical trials using fluorouracil-based adjuvant chemotherapy were analyzed in an attempt to predict benefit based on MSI status. Benefit was only seen in pMMR patients, with a HR of 0.72; this was not seen in the dMMR patients.57 Subsequent studies have had different findings and did not demonstrate a detrimental effect of fluorouracil in dMMR.58,59 For stage III patients, MSI status does not appear to affect benefit from chemotherapy, as analysis of data from the NSABP C-07 trial (Table 3) demonstrated benefit of FOLFOX (leucovorin, fluorouracil, oxaliplatin) in patients with dMMR status and stage III disease.59

Another genetic abnormality identified in colon cancers is chromosome 18q loss of heterozygosity (LOH). The presence of 18q LOH appears to be inversely associated with MSI-high status. Some reports have linked presence of 18q with worse outcome,60 but others question this, arguing the finding may simply be related to MSI status.61,62 This biomarker has not been established as a clear prognostic marker that can aid clinical decisions.

Most recently, expression of caudal-type homeobox transcription factor 2 (CDX2) has been reported as a novel prognostic and predictive tool. A 2015 report linked lack of expression of CDX2 to worse outcome; in this study, 5-year DFS was 41% in patients with CDX2-negative tumors versus 74% in the CDX2-positive tumors, with a HR of disease recurrence of 2.73 for CDX2-negative tumors.63 Similar numbers were observed in patients with stage II disease, with 5-year OS of 40% in patients with CDX2-negative tumors versus 70% in those with CDX2-positive tumors. Treatment of CDX2-negative patients with adjuvant chemotherapy improved outcomes: 5-year DFS in the stage II subgroup was 91% with chemotherapy versus 56% without, and in the stage III subgroup, 74% with chemotherapy versus 37% without. The authors concluded that patients with stage II and III colon cancer that is CDX2-negative may benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy. Importantly, CDX2-negativity is a rare event, occurring in only 6.9% of evaluable tumors.

RISK ASSESSMENT TOOLS

Several risk assessment tools have been developed in an attempt to aid clinical decision making regarding adjuvant chemotherapy for patients with stage II colon cancer. The Oncotype DX Colon Assay analyses a 12-gene signature in the pathologic sample and was developed with the goal to improve prognostication and aid in treatment decision making. The test utilizes reverse transcription-PCR on RNA extracted from the tumor.64 After evaluating 12 genes, a recurrence score is generated that predicts the risk of disease recurrence. This score was validated using data from 3 large clinical trials.65–67 Unlike the Oncotype Dx score used in breast cancer, the test in colon cancer has not been found to predict the benefit from chemotherapy and has not been incorporated widely into clinical practice.

Adjuvant! Online (available at www.adjuvantonline.com) is a web-based tool that combines clinical and histological features to estimate outcome. Calculations are based on US SEER tumor registry-reported outcomes.68 A second web-based tool, Numeracy (available at www.mayoclinic.com/calcs), was developed by the Mayo Clinic using pooled data from 7 randomized clinical trials including 3341 patients.68 Both tools seek to predict absolute benefit for patients treated with fluorouracil, though data suggests Adjuvant! Online may be more reliable in its predictive ability.69 Adjuvant! Online has also been validated in an Asian population70 and patients older than 70 years.71

MUTATIONAL ANALYSIS

Multiple mutations in proto-oncogenes have been found in colon cancer cells. One such proto-oncogene is BRAF, which encodes a serine-threonine kinase in the rapidly accelerated fibrosarcoma (RAF). Mutations in BRAF have been found in 5% to 10% of colon cancers and are associated with right-sided tumors.72 As a prognostic marker, some studies have associated BRAF mutations with worse prognosis, including shorter time to relapse and shorter OS.73,74 Two other proto-oncogenes are Kristen rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog (KRAS) and neuroblastoma rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog (NRAS), both of which encode proteins downstream of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR). KRAS and NRAS mutations have been shown to be predictive in the metastatic setting where they predict resistance to the EGFR inhibitors cetuximab and panitumumab.75,76 The effect of KRAS and NRAS mutations on outcome in stage II and III colon cancer is uncertain. Some studies suggest worse outcome in KRAS-mutated cancers,77 while others failed to demonstrate this finding.73

CASE PRESENTATION 1

A 53-year-old man with no past medical history presents to the emergency department with early satiety and generalized abdominal pain. Laboratory evaluation shows a microcytic anemia with normal white blood cell count, platelet count, renal function, and liver function tests. Computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis show a 4-cm mass in the transverse colon without obstruction and without abnormality in the liver. CT scan of the chest does not demonstrate pathologic lymphadenopathy or other findings. He undergoes robotic laparoscopic transverse colon resection and appendectomy. Pathology confirms a 3.5-cm focus of adenocarcinoma of the colon with invasion through the muscularis propria and 5 of 27 regional lymph nodes positive for adenocarcinoma and uninvolved proximal, distal, and radial margins. He is given a stage of IIIB pT3 pN2a M0 and referred to medical oncology for further management, where 6 months of adjuvant FOLFOX chemotherapy is recommended.

ADJUVANT CHEMOTHERAPY IN STAGE III COLON CANCER

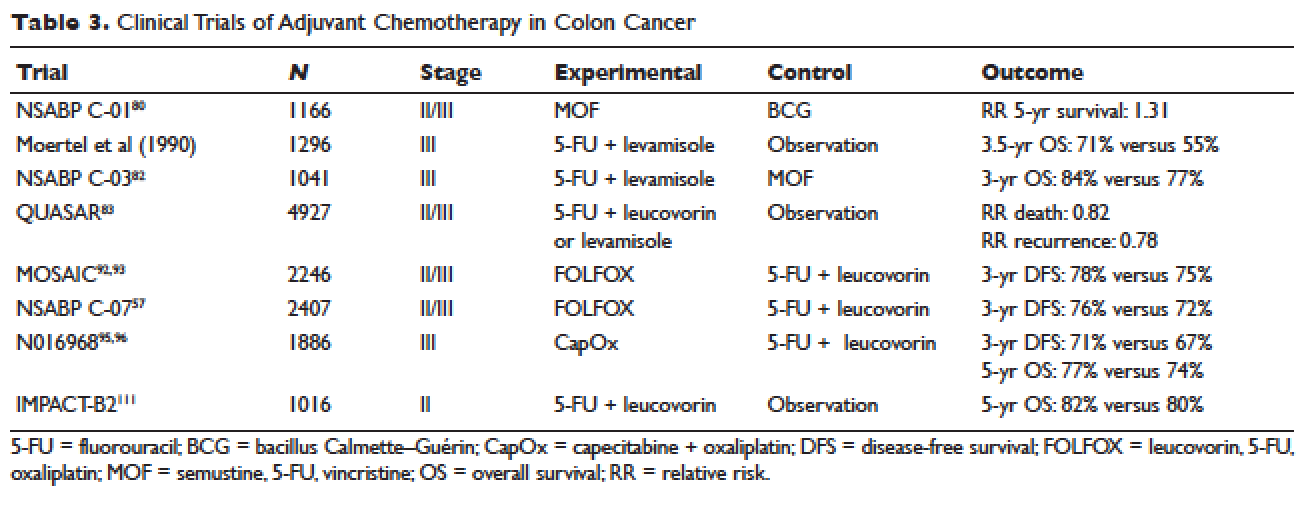

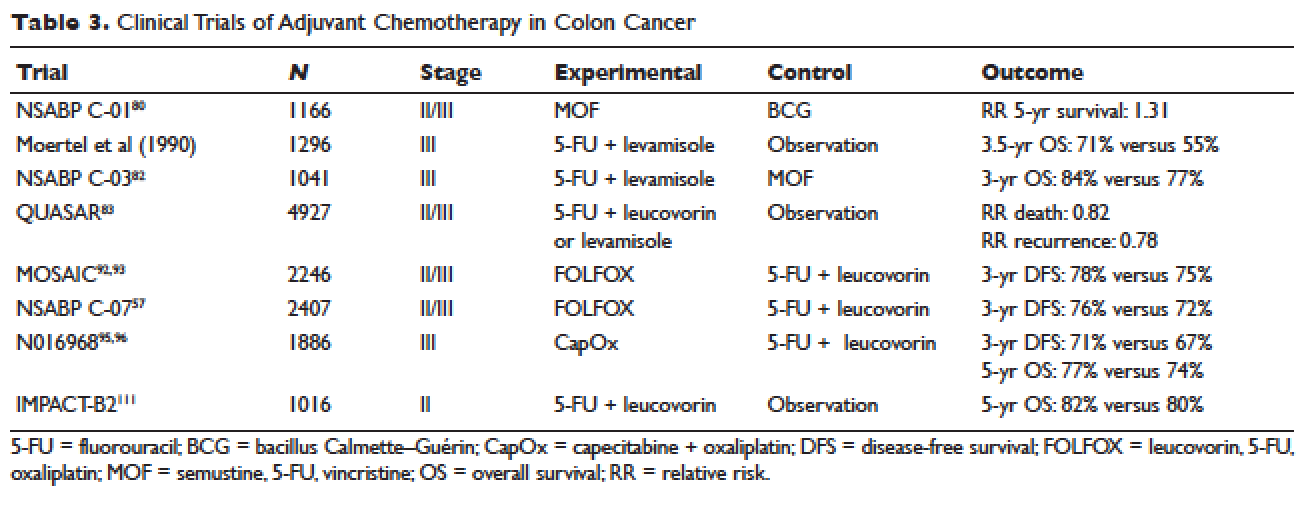

Postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy is the standard of care for patients with stage III disease. In the 1960s, infusional fluorouracil was first used to treat inoperable colon cancer.78,79 After encouraging results, the agent was used both intraluminally and intravenously as an adjuvant therapy for patients undergoing resection with curative intent; however, only modest benefits were described.80,81 The National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP) C-01 trial (Table 3) was the first study to demonstrate a benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy in colon cancer. This study randomly assigned patients with stage II and III colon cancer to surgery alone, postoperative chemotherapy with fluorouracil, semustine, and vincristine (MOF), or postoperative bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG). DFS and OS were significantly improved with MOF chemotherapy.82 In 1990, a landmark study reported on outcomes after treatment of 1296 patients with stage III colon cancer with adjuvant fluorouracil and levamisole for 12 months. The combination was associated with a 41% reduction in risk of cancer recurrence and a 33% reduction in risk of death.83 The NSABP C-03 trial (Table 3) compared MOF to the combination of fluorouracil and leucovorin and demonstrated improved 3-year DFS (69% versus 73%) and 3-year OS (77% versus 84%) in patients with stage III disease.84 Building on these outcomes, the QUASAR study (Table 3) compared fluorouracil in combination with one of levamisole, low-dose leucovorin, or high-dose leucovorin. The study enrolled 4927 patients and found worse outcomes with fluorouracil plus levamisole and no difference in low-doseversus high-dose leucovorin.85 Levamisole fell out of use after associations with development of multifocal leukoencephalopathy,86 and was later shown to have inferior outcomes versus leucovorin when combined with fluorouracil.87,88 Intravenous fluorouracil has shown similar benefit when administered by bolus or infusion,89 although continuous infusion has been associated with lower incidence of severe toxicity.90 The efficacy of the oral fluoropyrimidine capecitabine has been shown to be equivalent to that of fluorouracil.91

Fluorouracil-based treatment remained the standard of care until the introduction of oxaliplatin in the mid-1990s. After encouraging results in the metastatic setting,92,93 the agent was moved to the adjuvant setting. The MOSAIC trial (Table 3) randomly assigned patients with stage II and III colon cancer to fluorouracil with leucovorin (FULV) versus FOLFOX given once every 2 weeks for 12 cycles. Analysis with respect to stage III patients showed a clear survival benefit, with a 10-year OS of 67.1% with FOLFOX chemotherapy versus 59% with fluorouracil and leucovorin.94,95 The NSABP C-07 (Table 3) trial used a similar trial design but employed bolus fluorouracil. More than 2400 patients with stage II and III colon cancer were randomly assigned to bolus FULV or bolus fluorouracil, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin (FLOX). The addition of oxaliplatin significantly improved outcomes, with 4-year DFS of 67% versus 71.8% for FULV and FLOX, respectively, and a HR of death of 0.80 with FLOX.59,96 The multicenter N016968 trial (Table 3) randomly assigned 1886 patients with stage III colon cancer to adjuvant capecitabine plus oxaliplatin (XELOX) or bolus fluorouracil plus leucovorin (FU/FA). The 3-year DFS was 70.9% versus 66.5% with XELOX and FU/FA, respectively, and 5-year OS was 77.6% versus 74.2%, respectively.97,98

In the metastatic setting, additional agents have shown efficacy, including irinotecan,99,100 bevacizumab,101,102 cetuximab,103,104 and regorafenib.105 This observation led to testing of these agents in earlier stage disease. The CALGB 89803 trial compared fluorouracil, leucovorin, and irinotecan to fluorouracil with leucovorin alone. No benefit in 5-year DFS or OS was seen.106 Similarly, infusional fluorouracil, leucovorin, and irinotecan (FOLFIRI) was not found to improve 5-year DFS as compared to fluorouracil with leucovorin alone in the PETACC-3 trial.107 The NSABP C-08 trial considered the addition of bevacizumab to FOLFOX. When compared to FOLFOX alone, the combination of bevacizumab to FOLFOX had similar 3-year DFS (77.9% versus 75.1%) and 5-year OS (82.5% versus 80.7%).108 This finding was confirmed in the Avant trial.109 The addition of cetuximab to FOLFOX was equally disappointing, as shown in the N0147 trial110 and PETACC-8 trial.111 Data on regorafenib in the adjuvant setting for stage III colon cancer is lacking; however, 2 ongoing clinical trials, NCT02425683 and NCT02664077, are each studying the use of regorafenib following completion of FOLFOX for patients with stage III disease.

Thus, after multiple trials comparing various regimens and despite attempts to improve outcomes by the addition of a third agent, the standard of care per National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines for management of stage III colon cancer remains 12 cycles of FOLFOX chemotherapy. Therapy should be initiated within 8 weeks of surgery. Data are emerging to support a short duration of therapy for patients with low-risk stage III tumors, as shown in an abstract presented at the 2017 American Society of Clinical Oncology annual meeting. The IDEA trial was a pooled analysis of 6 randomized clinical trials across multiple countries, all of which evaluated 3 versus 6 months of FOLFOX or capecitabine and oxaliplatin in the treatment of stage III colon cancer. The analysis was designed to test non-inferiority of 3 months of therapy as compared to 6 months. The analysis included 6088 patients across 244 centers in 6 countries. The overall analysis failed to establish noninferiority. The 3-year DFS rate was 74.6% for 3 months and 75.5% for 6 months, with a DFS HR of 1.07 and a confidence interval that did not meet the prespecified endpoint. Subgroup analysis suggested noninferiority for lower stage disease (T1–3 or N1) but not for higher stage disease (T4 or N2). Given the high rates of neuropathy with 6 months of oxaliplatin, these results suggest that 3 months of adjuvant therapy can be considered for patients with T1–3 or N1 disease in an attempt to limit toxicity.112

CASE PRESENTATION 2

A 57-year-old woman presents to the emergency department with fever and abdominal pain. CT of the abdomen and pelvis demonstrates a left-sided colonic mass with surrounding fat stranding and pelvic abscess. She is taken emergently for left hemicolectomy, cholecystectomy, and evacuation of pelvic abscess. Pathology reveals a 5-cm adenocarcinoma with invasion through the visceral peritoneum; 0/22 lymph nodes are involved. She is given a diagnosis of stage IIC and referred to medical oncology for further management. Due to her young age and presence of high-risk features, she is recommended adjuvant therapy with FOLFOX for 6 months.

ADJUVANT CHEMOTHERAPY IN STAGE II COLON CANCER

Because of excellent outcomes with surgical resection alone for stage II cancers, the use of adjuvant chemotherapy for patients with stage II disease is controversial. Limited prospective data is available to guide adjuvant treatment decisions for stage II patients. The QUASAR trial, which compared observation to adjuvant fluorouracil and leucovorin in patients with early-stage colon cancer, included 2963 patients with stage II disease and found a relative risk (RR) of death or recurrence of 0.82 and 0.78, respectively. Importantly, the absolute benefit of therapy was less than 5%.113 The IMPACT-B2 trial (Table 3) combined data from 5 separate trials and analyzed 1016 patients with stage II colon cancer who received fluorouracil with leucovorin or observation. Event-free survival was 0.86 versus 0.83 and 5-year OS was 82% versus 80%, suggesting no benefit.114 The benefit of addition of oxaliplatin to fluorouracil in stage II disease appears to be less than the benefit of adding this agent in the treatment of stage III CRC. As noted above, the MOSAIC trial randomly assigned patients with stage II and III colon cancer to receive adjuvant fluorouracil and leucovorin with or without oxaliplatin for 12 cycles. After a median follow-up of 9.5 years, 10-year OS rates for patients with stage II disease were 78.4% versus 79.5%. For patients with high-risk stage II disease (defined as T4, bowel perforation, or fewer than 10 lymph nodes examined), 10-year OS was 71.7% and 75.4% respectively, but these differences were not statistically significant.94

Because of conflicting data as to the benefit of adding oxaliplatin in stage II disease, oxaliplatin is not recommended for standard-risk stage II patients. The use of oxaliplatin in high-risk stage II tumors should be weighed carefully given the toxicity risk. Oxaliplatin is recognized to cause sensory neuropathy in many patients, which can become painful and debilitating.115 Two types of neuropathy are associated with oxaliplatin: acute and chronic. Acute neuropathy manifests most often as cold-induced paresthesias in the fingers and toes and is quite common, affecting up to 90% of patients. These symptoms are self-limited and resolve usually within 1 week of each treatment.116 Some patients, with reports ranging from 10% to 79%, develop chronic neuropathy that persists for 1 year or more and causes significant decrements in quality of life.117 Patients older than age 70 may be at greater risk for oxaliplatin-induced neuropathy, which would increase risk of falls in this population.118 In addition to neuropathy, oxaliplatin is associated with hypersensitivity reactions that can be severe and even fatal.119 In a single institution series, the incidence of severe reactions was 2%.120 Desensitization following hypersensitivity reactions is possible but requires a time-intensive protocol.121

Based on the inconclusive efficacy findings and due to concerns over toxicity, each decision must be individualized to fit patient characteristics and preferences. In general, for patients with stage II disease without high-risk features, an individualized discussion should be held as to the risks and benefits of single-agent fluorouracil, and this treatment should be offered in cases where the patient or provider would like to be aggressive. Patients with stage II cancer who have 1 or more high-risk features are often recommended adjuvant chemotherapy. Whether treatment with fluorouracil plus leucovorin or FOLFOX is preferred remains uncertain, and thus the risks and the potential gains of oxaliplatin must be discussed with the individual patient. MMR status can also influence the treatment recommendation for patients with stage II disease. In general, patients with standard-risk stage II tumors that are pMMR are offered MMR with leucovorin or oral capecitabine for 12 cycles. FOLFOX is considered for patients with MSI-high disease and those with multiple high-risk features.

MONITORING AFTER THERAPY

After completion of adjuvant chemotherapy, patients enter a period of survivorship. Patients are seen in clinic for symptom and laboratory monitoring of the complete blood count, liver function tests, and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA). NCCN guidelines support history and physical examination with CEA testing every 3 to 6 months for the first 2 years, then every 6 months for the next 3 years, after which many patients continue to be seen annually. CT imaging of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis for monitoring of disease recurrence is recommended every 6 to 12 months for a total of 5 years. New elevations in CEA or liver function tests should prompt early imaging. Colonoscopy should be performed 1 year after completion of therapy; however, if no preoperative colonoscopy was performed, this should be done 3 to 6 months after completion. Colonoscopy is then repeated in 3 years and then every 5 years unless advanced adenomas are present.122

SUMMARY

The addition of chemotherapy to surgical management of colon cancer has lowered the rate of disease recurrence and improved long-term survival. Adjuvant FOLFOX for 12 cycles is the standard of care for patients with stage III colon cancer and for patients with stage II disease with certain high-risk features. Use of adjuvant chemotherapy in stage II disease without high-risk features is controversial, and treatment decisions should be individualized. Biologic markers such as MSI and CDX2 status as well as patient-related factors including age, overall health, and personal preferences can inform treatment decisions. If chemotherapy is recommended in this setting, it would be with single-agent fluorouracil in an infusional or oral formulation, unless the tumor has the MSI-high feature. Following completion of adjuvant therapy, patients should be followed with clinical evaluation, laboratory testing, and imaging for a total of 5 years as per recommended guidelines.

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin 2017;67(1):7–30.

- United States Cancer Statistics. 1999–2013 incidence and mortality web-based report. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Cancer Institute, 2016. www.cdc.gov/uscs. Accessed June 12, 2017.

- Ahnen DJ, Wade SW, Jones WF, et al. The increasing incidence of young-onset colorectal cancer: a call to action. Mayo Clin Proc 2014;89:216–24.

- Jemal A, Fedewa SA, Anderson WF, et al. Colorectal cancer incidence patterns in the United States, 1974–2013. J Natl Cancer Inst 2017;109(8).

- Boursi B, Sella T, Liberman E, et al. The APC p.I1307K polymorphism is a significant risk factor for CRC in average risk Ashkenazi Jews. Eur J Cancer 2013;49:3680–5.

- Parry S, Win AK, Parry B, et al. Metachronous colorectal cancer risk for mismatch repair gene mutation carriers: the advantage of more extensive colon surgery. Gut 2011;60: 950–7.

- van Puijenbroek M, Nielsen M, Tops CM, et al. Identification of patients with (atypical) MUTYH-associated polyposis by KRAS2 c.34G > T prescreening followed by MUTYH hotspot analysis in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue. Clin Cancer Res 2008;14:139–42.

- Aretz S, Uhlhaas S, Goergens H, et al. MUTYH-associated polyposis: 70 of 71 patients with biallelic mutations present with an attenuated or atypical phenotype. Int J Cancer 2006;119:807–14.

- Tuohy TM, Rowe KG, Mineau GP, et al. Risk of colorectal cancer and adenomas in the families of patients with adenomas: a population-based study in Utah. Cancer 2014;120:35–42.

- Choi Y, Sateia HF, Peairs KS, Stewart RW. Screening for colorectal cancer. Semin Oncol 2017; 44:34–44.

- Atkin WS, Morson BC, Cuzick J. Long-term risk of colorectal cancer after excision of rectosigmoid adenomas. N Engl J Med 1992;326:658–62.

- Rutter MD. Surveillance programmes for neoplasia in colitis. J Gastroenterol 2011;46 Suppl 1:1–5.

- Giovannucci E. Modifiable risk factors for colon cancer. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2002;31:925–43.

- Michels KB, Fuchs GS, Giovannucci E, et al. Fiber intake and incidence of colorectal cancer among 76,947 women and 47,279 men. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2005;14:842–9.

- Omata F, Brown WR, Tokuda Y, et al. Modifiable risk factors for colorectal neoplasms and hyperplastic polyps. Intern Med 2009;48:123–8.

- Friedenreich CM, Neilson HK, Lynch BM. State of the epidemiological evidence on physical activity and cancer prevention. Eur J Cancer 2010;46:2593–604.

- Aleksandrova K, Pischon T, Jenab M, et al. Combined impact of healthy lifestyle factors on colorectal cancer: a large European cohort study. BMC Med 2014;12:168.

- Hermanek P, Wittekind C. The pathologist and the residual tumor (R) classification. Pathol Res Pract 1994;190:115–23.

- Lehnert T, Methner M, Pollok A, et al. Multivisceral resection for locally advanced primary colon and rectal cancer: an analysis of prognostic factors in 201 patients. Ann Surg 2002;235:217–25.

- Feinberg AE, et al. Oncologic outcomes following laparoscopic versus open resection of pT4 colon cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Dis Colon Rectum 2017;60:116–125.

- Vignali A, et al. Laparoscopic treatment of advanced colonic cancer: a case-matched control with open surgery. Colorectal Dis 2013;15:944–8.

- Gainant A. Emergency management of acute colonic cancer obstruction. J Visc Surg 2012;149: e3–e10.

- Rosenman LD. Hartmann’s operation. Am J Surg 1994;168:283–4.

- Lee-Kong S, Lisle D. Surgical management of complicated colon cancer. Clin Colon Rectal Surg 2015;28:228–33.

- Bertelsen CA. Complete mesocolic excision an assessment of feasibility and outcome. Dan Med J 2017;64(2).

- Wolff WI SH. Definitive treatment of “malignant” polyps of the colon. Ann Surg 1975;182:516–25.

- Clinical Outcomes of Surgical Therapy Study Group, Nelson H, Sargent DJ, Wieand HS, et al. A comparison of laparoscopically assisted and open colectomy for colon cancer. N Engl J Med 2004;350:2050–9.

- Gunderson LL, Jessup JM, Sarjent DJ, et al. Revised tumor and node categorization for rectal cancer based on surveillance, epidemiology, and end results and rectal pooled analysis outcomes. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:256–63.

- Noone AM, Cronin KA, Altekruse SF, et al. Cancer incidence and survival trends by subtype using data from the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results Program, 1992-2013. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2017;26:632–41.

- Alves A, Panis Y, Mathieu P, et al. Postoperative mortality and morbidity in French patients undergoing colorectal surgery: results of a prospective multicenter study. Arch Surg 2005;140:278–83.

- Popescu RA, Norman A, Ross PJ, et al, Adjuvant or palliative chemotherapy for colorectal cancer in patients 70 years or older. J Clin Oncol 1999;17:2412–8.

- McCleary NJ, Meyerhardt JA, Green E, et al. Impact of age on the efficacy of newer adjuvant therapies in patients with stage II/III colon cancer: findings from the ACCENT database. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:2600–6.

- Tominaga T, Nonaka T, Sumida Y, et al. Effectiveness of adjuvant chemotherapy for elderly patients with lymph node-positive colorectal cancer. World J Surg Oncol 2016;14:197.

- Bos AC, van Erning FN, van Gestel YR, et al. Timing of adjuvant chemotherapy and its relation to survival among patients with stage III colon cancer. Eur J Cancer 2015;51:2553–61.

- Peixoto RD, Kumar A, Speers C, et al. Effect of delay in adjuvant oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy for stage III colon cancer. Clin Colorectal Cancer 2015;14:25–30.

- Compton CC, Fielding LP, Burgart LJ, et al. Prognostic factors in colorectal cancer. College of American Pathologists Consensus Statement 1999. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2000;124:979–94.

- Lieu CH, Lambert LA, Wolff RA, et al. Systemic chemotherapy and surgical cytoreduction for poorly differentiated and signet ring cell adenocarcinomas of the appendix. Ann Oncol 2012;23:652–8.

- Krasna MJ, Flancbaum L, Cody RP, et al. Vascular and neural invasion in colorectal carcinoma. Incidence and prognostic significance. Cancer 1988;61:1018–23.

- Cianchi F, Palomba A, Boddi V, et al. Lymph node recovery from colorectal tumor specimens: recommendation for a minimum number of lymph nodes to be examined. World J Surg 2002;26:384–9.

- Yoshimatsu K, et al. How many lymph nodes should be examined in Dukes’ B colorectal cancer? Determination on the basis of cumulative survival rate. Hepatogastroenterology 2005;52:1703–6.

- Caplin S, Cerottini JP, Bosman FT, et al. For patients with Dukes’ B (TNM Stage II) colorectal carcinoma, examination of six or fewer lymph nodes is related to poor prognosis. Cancer 1998;83:666–72.

- Veronese N, Nottegar A, Pea A, et al. Prognostic impact and implications of extracapsular lymph node involvement in colorectal cancer: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Ann Oncol 2016;27:42–8.

- Li J, Yang S, Hu J, et al. Tumor deposits counted as positive lymph nodes in TNM staging for advanced colorectal cancer: a retrospective multicenter study. Oncotarget 2016;7:18269–79.

- Venook A, Niedzwiecki D, Innocenti Fet al. Impact of primary (1º) tumor location on overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) in patients (pts) with metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC): Analysis of CALGB/SWOG 80405 (Alliance). J Clin Oncol 2016;34 no. 15 suppl. Abstract 3504.

- Schrag D, Brooks G, Meyerhardt JA ,et al. The relationship between primary tumor sidedness and prognosis in colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2016;34 no. 15 suppl. Abstract 3505.

- Larrea AA, Lujan SA, Kunkel TA. SnapShot: DNA mismatch repair. Cell 2010;141:730 e1.

- Jass JR. Pathology of hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2000;910:62–73.

- Lynch HT, Smyrk T. Hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (Lynch syndrome). An updated review. Cancer 1996;78:1149–67.

- Aaltonen LA, Peltomäki P, Leach FS, et al. Clues to the pathogenesis of familial colorectal cancer. Science 1993;260:812–6.

- Chen W, Swanson BJ, Frankel WL. Molecular genetics of microsatellite-unstable colorectal cancer for pathologists. Diagn Pathol 2017;12:24.

- Bupathi M, Wu C. Biomarkers for immune therapy in colorectal cancer: mismatch-repair deficiency and others. J Gastrointest Oncol 2016;7:713–20.

- Popat S, Hubner R, Houlston RS. Systematic review of microsatellite instability and colorectal cancer prognosis. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:609–18.

- Gryfe R, Kim H, Hsieh ET, et al. Tumor microsatellite instability and clinical outcome in young patients with colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med 2000;342:69–77.

- Ogino S, Kuchiba A, Qian ZR, et al. Prognostic significance and molecular associations of 18q loss of heterozygosity: a cohort study of microsatellite stable colorectal cancers. J Clin Oncol 2009; 27:4591–8.

- Kim ST, Lee J, Park SH, et al. The effect of DNA mismatch repair (MMR) status on oxaliplatin-based first-line chemotherapy as in recurrent or metastatic colon cancer. Med Oncol 2010;27:1277–85.

- Sargent DJ, Monges G, Thibodeau SN, et al. Therapy in colon cancer. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:4664.

- Ribic CM, Sargent DJ, Moore MJ, et al. Tumor microsatellite-instability status as a predictor of benefit from fluorouracil-based adjuvant chemotherapy for colon cancer. N Engl J Med 2003;349:247–57.

- Hutchins G, Southward K, Handley K, et al. Value of mismatch repair, KRAS, and BRAF mutations in predicting recurrence and benefits from chemotherapy in colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:1261–270.

- Yothers G, O’Connell MJ, Allegra CJ, et al. Oxaliplatin as adjuvant therapy for colon cancer: updated results of NSABP C-07 trial, including survival and subset analyses J Clin Oncol 2011;29:3768–74.

- Chang SC, Lin JK, Lin TC, Liang WY. Loss of heterozygosity: an independent prognostic factor of colorectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2005;11:778–84.

- Bertagnolli MM, Niedzwiecki D, Compton CC, et al. Microsatellite instability predicts improved response to adjuvant therapy with irinotecan, fluorouracil, and leucovorin in stage III colon cancer: Cancer and Leukemia Group B Protocol 89803. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:1814–21.

- Bertagnolli MM, Redston M, Compton CC, et al. Microsatellite instability and loss of heterozygosity at chromosomal location 18q: prospective evaluation of biomarkers for stages II and III colon cancer--a study of CALGB 9581 and 89803. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:3153–62.

- Dalerba P, et al. CDX2 as a prognostic biomarker in stage II and stage III colon cancer. N Engl J Med 2016;374: 211–22.

- Clark-Langone KM, Wu JY, Sangli C, et al. Biomarker discovery for colon cancer using a 761 gene RT-PCR assay. BMC Genomics 2007;8:279.

- Gray RG, Quirke P, Handley K, et al. Validation study of a quantitative multigene reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction assay for assessment of recurrence risk in patients with stage II colon cancer. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:4611–9.

- Niedzwiecki D, Bertagnolli MM, Warren RS, et al. Documenting the natural history of patients with resected stage II adenocarcinoma of the colon after random assignment to adjuvant treatment with edrecolomab or observation: results from CALGB 9581. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:3146–52.

- Yothers G, O’Connell MJ, Lee M, et al. Validation of the 12-gene colon cancer recurrence score in NSABP C-07 as a predictor of recurrence in patients with stage II and III colon cancer treated with fluorouracil and leucovorin (FU/LV) and FU/LV plus oxaliplatin. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:4512–9.

- Gill S, Loprinzi CL, Sargent DJ, et al. Pooled analysis of fluorouracil-based adjuvant therapy for stage II and III colon cancer: who benefits and by how much? J Clin Oncol 2004;22:1797–806.

- Gill S, Loprinzi C, Kennecke H, et al. Prognostic web-based models for stage II and III colon cancer: A population and clinical trials-based validation of numeracy and adjuvant! online. Cancer 2011;117:4155–65.

- Jung M, Kim GW, Jung I, et al. Application of the Western-based adjuvant online model to Korean colon cancer patients; a single institution experience. BMC Cancer 2012;12:471.

- Papamichael D, Renfro LA, Matthaiou C, et al. Validity of Adjuvant! Online in older patients with stage III colon cancer based on 2967 patients from the ACCENT database. J Geriatr Oncol 2016;7:422–9.

- Tran B, Kopetz S, Tie J, et al. Impact of BRAF mutation and microsatellite instability on the pattern of metastatic spread and prognosis in metastatic colorectal cancer. Cancer 2011;117:4623–32.

- Roth AD, Tejpar S, Delorenzi M, et al. Prognostic role of KRAS and BRAF in stage II and III resected colon cancer: results of the translational study on the PETACC-3, EORTC 40993, SAKK 60-00 trial. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:466–74.

- Lochhead P, Kuchiba A, Imamura Y, et al. Microsatellite instability and BRAF mutation testing in colorectal cancer prognostication. J Natl Cancer Inst 2013;105:1151–6.

- Benvenuti S, Sartore-Bianchi A, Di Nicolantonio F, et al. Oncogenic activation of the RAS/RAF signaling pathway impairs the response of metastatic colorectal cancers to anti-epidermal growth factor receptor antibody therapies. Cancer Res 2007;67:2643–8.

- Therkildsen C, Bergmann TK, Henrichsen-Schnack T, et al. The predictive value of KRAS, NRAS, BRAF, PIK3CA and PTEN for anti-EGFR treatment in metastatic colorectal cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Oncol 2014;53:852–64.

- Taieb J, Le Malicot K, Shi Q, et al. Prognostic value of BRAF and KRAS mutations in MSI and MSS stage III colon cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 2017;109(5).

- Palumbo LT, Sharpe WS, Henry JS. Cancer of the colon and rectum; analysis of 300 cases. Am J Surg 1965;109:439–44.

- Sharp GS, Benefiel WW. 5-Fluorouracil in the treatment of inoperable carcinoma of the colon and rectum. Cancer Chemother Rep 1962;20:97–101.

- Lawrence W Jr, Terz JJ, Horsley JS 3rd, et al. Chemotherapy as an adjuvant to surgery for colorectal cancer. Ann Surg 1975;181:616–23.

- Grage TD, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy with 5-fluorouracil after surgical resection of colorectal carcinoma (COG protocol 7041). A preliminary report. Am J Surg 1977;133:59–66.

- Wolmark N, Fisher B, Rockette H, et al. Postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy or BCG for colon cancer: results from NSABP protocol C-01. J Natl Cancer Inst 1988;80:30–6.

- Moertel CG, Fleming TR, Macdonald JS, et al. Levamisole and fluorouracil for adjuvant therapy of resected colon carcinoma. N Engl J Med 1990;322:352–8.

- Wolmark N, Rockette H, Fisher B, et al. The benefit of leucovorin-modulated fluorouracil as postoperative adjuvant therapy for primary colon cancer: results from National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project protocol C-03. J Clin Oncol 1993;11:1879–87.

- Comparison of fluorouracil with additional levamisole, higher-dose folinic acid, or both, as adjuvant chemotherapy for colorectal cancer: a randomised trial. QUASAR Collaborative Group. Lancet 2000;355(9215):1588–96.

- Chen TC, Hinton DR, Leichman L, et al. Multifocal inflammatory leukoencephalopathy associated with levamisole and 5-fluorouracil: case report. Neurosurgery 1994;35:1138-42.

- Porschen R, Bermann A, Löffler T, et al. Fluorouracil plus leucovorin as effective adjuvant chemotherapy in curatively resected stage III colon cancer: results of the trial adjCCA-01. J Clin Oncol 2001;19:1787–94.

- Arkenau HT, Bermann A, Rettig K, et al. 5-Fluorouracil plus leucovorin is an effective adjuvant chemotherapy in curatively resected stage III colon cancer: long-term follow-up results of the adjCCA-01 trial. Ann Oncol 2003;14:395–9.

- Weinerman B, Shah A, Fields A, et al. Systemic infusion versus bolus chemotherapy with 5-fluorouracil in measurable metastatic colorectal cancer. Am J Clin Oncol 1992;15:518–23.

- Poplin EA, Benedetti JK, Estes NC, et al. Phase III Southwest Oncology Group 9415/Intergroup 0153 randomized trial of fluorouracil, leucovorin, and levamisole versus fluorouracil continuous infusion and levamisole for adjuvant treatment of stage III and high-risk stage II colon cancer. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:1819–25.

- Twelves C, Wong A, Nowacki MP, et al. Capecitabine as adjuvant treatment for stage III colon cancer. N Engl J Med 2005;352:2696–704.

- de Gramont A, Vignoud J, Tournigand C, et al. Oxaliplatin with high-dose leucovorin and 5-fluorouracil 48-hour continuous infusion in pretreated metastatic colorectal cancer. Eur J Cancer 1997;33:214–9.

- Diaz-Rubio E, Sastre J, Zaniboni A, et al. Oxaliplatin as single agent in previously untreated colorectal carcinoma patients: a phase II multicentric study. Ann Oncol 1998;9:105–8.

- André T, de Gramont A, Vernerey D, et al. Adjuvant fluorouracil, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin in Stage II to III Colon Cancer: Updated 10-Year Survival and Outcomes According to BRAF mutation and mismatch repair status of the MOSAIC Study. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:4176–87.

- Andre T, Boni C, Mounedji-Boudiaf L, et al. Oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin as adjuvant treatment for colon cancer. N Engl J Med 2004;350:2343–51.

- Kuebler JP, Wieand HS, O’Connell MJ, et al. Oxaliplatin combined with weekly bolus fluorouracil and leucovorin as surgical adjuvant chemotherapy for stage II and III colon cancer: results from NSABP C-07. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:2198–204.

- Haller DG, Tabernero J, Maroun J, et al. Capecitabine plus oxaliplatin compared with fluorouracil and folinic acid as adjuvant therapy for stage III colon cancer. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:1465–71.

- Schmoll HJ, et al. Capecitabine plus oxaliplatin compared with fluorouracil/folinic acid as adjuvant therapy for stage III colon cancer: final results of the NO16968 randomized controlled phase III trial. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:3733–40.

- Colucci G, Gebbia V, Paoletti G, et al. Phase III randomized trial of FOLFIRI versus FOLFOX4 in the treatment of advanced colorectal cancer: a multicenter study of the Gruppo Oncologico Dell’Italia Meridionale. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:4866–75.

- Tournigand C, André T, Achille E, et al. FOLFIRI followed by FOLFOX6 or the reverse sequence in advanced colorectal cancer: a randomized GERCOR study. J Clin Oncol 2004;22:229–37.

- Hurwitz H, Fehrenbacher L, Novotny W, et al. Bevacizumab plus irinotecan, fluorouracil, and leucovorin for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med 2004;350:2335–42.

- Saltz LB, et al. Bevacizumab in combination with oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy as first-line therapy in metastatic colorectal cancer: a randomized phase III study. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:2013–9.

- Cremolini C, Loupakis F, Ruzzo A, et al. Predictors of benefit in colorectal cancer treated with cetuximab: are we getting “Lost in TranslationAL”? J Clin Oncol 2010;28:e173–4.

- Sorich MJ, Wiese MD, Rowland D, et al. Extended RAS mutations and anti-EGFR monoclonal antibody survival benefit in metastatic colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials. Ann Oncol 2015;26:13–21.

- Grothey A, van Cutsem E, Sobrero A, et al. Regorafenib monotherapy for previously treated metastatic colorectal cancer (CORRECT): an international, multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2013;381(9863):303–12.

- Saltz LB, Niedzwiecki D, Hollis D, et al. Irinotecan fluorouracil plus leucovorin is not superior to fluorouracil plus leucovorin alone as adjuvant treatment for stage III colon cancer: results of CALGB 89803. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:3456–61.

- Van Cutsem E, et al. Randomized phase III trial comparing biweekly infusional fluorouracil/leucovorin alone or with irinotecan in the adjuvant treatment of stage III colon cancer: PETACC-3. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:3117–25.

- Allegra CJ, et al. Bevacizumab in stage II-III colon cancer: 5-year update of the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project C-08 trial. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:359–64.

- de Gramont A, et al. Bevacizumab plus oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy as adjuvant treatment for colon cancer (AVANT): a phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 2012;13:1225–33.

- Alberts SR, et al. Effect of oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin with or without cetuximab on survival among patients with resected stage III colon cancer: a randomized trial. JAMA 2012;307:1383–93.

- Taieb J, et al. Oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin with or without cetuximab in patients with resected stage III colon cancer (PETACC-8): an open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2014;15:862–73.

- Shi Q, Sobrero AF, Shields AF, et al. Prospective pooled analysis of six phase III trials investigating duration of adjuvant (adjuvant) oxaliplatin-based therapy (3 vs 6 months) for patients (pts) with stage III colon cancer (CC): The IDEA (International Duration Evaluation of Adjuvant chemotherapy) collaboration. In: Proceedings from the American Society of Clinical Oncology; June 1–5, 2017; Chicago. Abstract LBA1.

- Quasar Collaborative Group; Gray R, Barnwell J, McConkey C, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy versus observation in patients with colorectal cancer: a randomised study. Lancet 2007;370(9604):2020–9.

- Efficacy of adjuvant fluorouracil and folinic acid in B2 colon cancer. International Multicentre Pooled Analysis of B2 Colon Cancer Trials (IMPACT B2) Investigators. J Clin Oncol 1999;17:1356–63.

- Kidwell KM, et al. Long-term neurotoxicity effects of oxaliplatin added to fluorouracil and leucovorin as adjuvant therapy for colon cancer: results from National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project trials C-07 and LTS-01. Cancer 2012;118:5614–22.

- Beijers AJ, Mols F, Vreugdenhil G. A systematic review on chronic oxaliplatin-induced peripheral neuropathy and the relation with oxaliplatin administration. Support Care Cancer 2014;22:1999–2007.

- Mols F, Beijers T, Lemmens V, et al. Chemotherapy-induced neuropathy and its association with quality of life among 2- to 11-year colorectal cancer survivors: results from the population-based PROFILES registry. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:2699–707.

- Raphael MJ, Fischer HD, Fung K, et al. Neurotoxicity outcomes in a population-based cohort of elderly patients treated with adjuvant oxaliplatin for colorectal cancer. Clin Colorectal Cancer 2017 March 24.

- Toki MI, Saif MW, Syrigos KN. Hypersensitivity reactions associated with oxaliplatin and their clinical management. Expert Opin Drug Saf 2014;13:1545–54.

- Siu SW, Chan RT, Au GK. Hypersensitivity reactions to oxaliplatin: experience in a single institute. Ann Oncol 2006;17:259–61.

- Wong JT, Ling M, Patil S, et al. Oxaliplatin hypersensitivity: evaluation, implications of skin testing, and desensitization. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2014;2:40–5.

- Benson AB 3rd, Venook AP, Cederquist L, et al. NCCN Guidelines Colon Cancer Version 2.2017. www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/colon.pdf. Accessed May 8, 2017.

- Wolmark N, Rockette H, Mamounas E, et al. Clinical trial to assess the relative efficacy of fluorouracil and leucovorin, fluorouracil and levamisole, and fluorouracil, leucovorin, and levamisole in patients with Dukes’ B and C carcinoma of the colon: results from National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project C-04. J Clin Oncol 1999;17:3553–9.

INTRODUCTION

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most prevalent malignancies and is the fourth most common cancer in the United States, with an estimated 133,490 new cases diagnosed in 2016. Of these, approximately 95,520 are located in the colon and 39,970 are in the rectum.1 CRC is the third leading cause of cancer death in women and the second leading cause of cancer death in men, with an estimated 49,190 total deaths in 2016.2 The incidence appears to be increasing,3 especially in patients younger than 55 years of age;4 the reason for this increase remains uncertain.

A number of risk factors for the development of CRC have been identified. Numerous hered-itary CRC syndromes have been described, including familial adenomatous polyposis,5 hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC) or Lynch syndrome,6 and MUTYH-associated polyposis.7,8 A family history of CRC doubles the risk of developing CRC,9 and current guidelines support lowering the age of screening in individuals with a family history of CRC to 10 years younger than the age of diagnosis of the family member or 40 years of age, whichever is lower.10 Patients with a personal history of adenomatous polyps are at increased risk for developing CRC, as are patients with a personal history of CRC, with a relative risk ranging from 3 to 6.11 Ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease are associated with the development of CRC and also influence screening, though evidence suggests good control of these diseases may mitigate risk.12 Finally, modifiable risk factors for the development of CRC include high red meat consumption,13 diets low in fiber,14 obesity,13 smoking, alcohol use,15 and physical inactivity16; lifestyle modification targeting these factors has been shown to decrease rates of CRC.17 The majority of colon cancers present with clinical symptoms, often with rectal bleeding, abdominal pain, change in bowel habits, or obstructive symptoms. More rarely, these tumors are detected during screening colonoscopy, in which case they tend to be at an early stage.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

A critical goal in the resection of early-stage colon cancer is attaining R0 resection. Patients who achieve R0 resection as compared to R1 (microscopic residual tumor) and R2 (macroscopic residual tumor)18 have significantly improved long-term overall survival.19 Traditionally, open resection of the involved colonic segment was employed, with end-end anastomosis of the uninvolved free margins. Laparoscopic resection for early-stage disease has been utilized in attempts to decrease morbidity of open procedures, with similar outcomes and node sampling.20 Laparoscopic resection appears to provide similar outcomes even in locally advanced disease.21 Right-sided lesions are treated with right colectomy and primary ileocolic anastomosis.22 For patients presenting with obstructing masses, the Hartmann procedure is the most commonly performed operation. This involves creation of an ostomy with subtotal colectomy and subsequent ostomy reversal in a 2- or 3-stage protocol.23 Patients with locally advanced disease and invasion into surrounding structures require multivisceral resection, which involves resection en bloc with secondarily involved organs.24 Intestinal perforation presents a unique challenge and is associated with surgical complications, infection, and lower overall survival (OS) and 5-year disease-free survival (DFS). Complete mesocolic excision is a newer technique that has been performed with reports of better oncologic outcome at some centers; however, this approach is not currently considered standard of care.25

STAGING

According to a report by the National Cancer Institute, the estimated 5-year relative survival rates for localized colon cancer (lymph node negative), regional (lymph node positive) disease, and distant (metastatic) disease are 89.9%, 71.3%, and 13.9%, respectively.1 However, efforts have been made to further classify patients into distinct categories to allow fine-tuning of prognostication. In the current system, staging of colon cancer utilizes the American Joint Committee on Cancer tumor/node/metastasis (TNM) system.20 Clinical and pathologic features include depth of invasion, local invasion of other organs, nodal involvement, and presence of distant metastasis (Table 1). Studies completed prior to the adoption of the TNM system used the Dukes criteria, which divided colon cancer into A, B, and C, corresponding to TNM stage I, stage IIA–IIC, and stage IIIA-IIIC. This classification is rarely used in more contemporary studies.

APPROACH TO ADJUVANT CHEMOTHERAPY

Adjuvant chemotherapy seeks to eliminate micrometastatic disease present following curative surgical resection. When stage 0 cancer is discovered incidentally during colonoscopy, endoscopic resection alone is the management of choice, as presence of micrometastatic disease is exceedingly unlikely.26 Stage I–III CRCs are treated with surgical resection withcurative intent. The 5-year survival rate for stage I and early-stage II CRC is estimated at 97% with surgery alone.27,28 The survival rate drops to about 60% for high-risk stage II tumors (T4aN0), and down to 50% or less for stage II-T4N0 or stage III cancers. Adjuvant chemotherapy is generally recommended to further decrease the rates of distant recurrence in certain cases of stage II and in all stage III tumors.

DETERMINATION OF BENEFIT FROM CHEMOTHERAPY: PROGNOSTIC MARKERS

Prior to administration of adjuvant chemotherapy, a clinical evaluation by the medical oncologist to determine appropriateness and safety of treatment is paramount. Poor performance status and comorbid conditions may indicate risk for excessive toxicity and minimal benefit from chemotherapy. CRC commonly presents in older individuals, with the median age at diagnosis of 69 years for men and 73 years for women.29 In this patient population, comorbidities such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and renal dysfunction are more prevalent.30 Decisions regarding adjuvant chemotherapy in this patient population have to take into consideration the fact that older patients may experience higher rates of toxicity with chemotherapy, including gastrointestinal toxicities and marrow suppression.31 Though some reports indicate patients older than 70 years derive similar benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy,32,33 a large pooled analysis of the ACCENT database, which included 7 adjuvant therapy trials and 14,528 patients, suggested limited benefit from the addition of oxaliplatin to fluorouracil in elderly patients.32 Other factors that weigh on the decision include stage, pathology, and presence of high-risk features. A common concern in the postoperative setting is delaying initiation of chemotherapy to allow adequate wound healing; however, evidence suggests that delays longer than 8 weeks leads to worse overall survival, with hazard ratios (HR) ranging from 1.4 to 1.7.34,35 Thus, the start of adjuvant therapy should ideally be within this time frame.

HIGH-RISK FEATURES

Multiple factors have been found to predict worse outcome and are classified as high-risk features (Table 2). Histologically, high-grade or poorly differentiated tumors are associated with higher recurrence rate and worse outcome.36 Certain histological subtypes, including mucinous and signet-ring, both appear to have more aggressive biology.37 Presence of microscopic invasion into surrounding blood vessels (vascular invasion) and nerves (perineural invasion) is associated with lower survival.38 Penetration of the cancer through the visceral peritoneum (T4a) or into surrounding structures (T4b) is associated with lower survival.36 During surgical resection, multiple lymph nodes are removed along with the primary tumor to evaluate for metastasis to the regional nodes. Multiple analyses have demonstrated that removal and pathologic assessment of fewer than 12 lymph nodes is associated with high risk of missing a positive node, and is thus equated with high risk.39–41 In addition, extension of tumor beyond the capsules of any single lymph node, termed extracapsular extension, is associated with an increased risk of all-cause mortality.42 Tumor deposits, or focal aggregates of adenocarcinoma in the pericolic fat that are not contiguous with the primary tumor and are not associated with lymph nodes, are currently classified as lymph nodes as N1c in the current TNM staging system. Presence of these deposits has been found to predict poor outcome stage for stage.43 Obstruction and/or perforation secondary to the tumor are also considered high-risk features that predict poor outcome.

SIDEDNESS

As reported at the 2016 American Society of Clinical Oncology annual meeting, tumor location predicts outcome in the metastatic setting. A report by Venook and colleagues based on a post-hoc analysis found that in the metastatic setting, location of the tumor primary in the left side is associated with longer OS (33.3 months) when compared to the right side of the colon (19.4 months).44 A retrospective analysis of multiple databases presented by Schrag and colleagues similarly reported inferior outcomes in patients with stage III and IV disease who had right-sided primary tumors.45 However, the prognostic implications for stage II disease remain uncertain.

BIOMARKERS

Given the controversy regarding adjuvant therapy of patients with stage II colon cancer, multiple biomarkers have been evaluated as possible predictive markers that can assist in this decision. The mismatch repair (MMR) system is a complex cellular enzymatic mechanism that identifies and corrects DNA errors during cell division and prevents mutagenesis.46 The familial cancer syndrome HNPCC is linked to alteration in a variety of MMR genes, leading to deficient mismatch repair (dMMR), also termed microsatellite instability-high (MSI-high).47,48 Epigenetic modification can also lead to silencing of the same implicated genes and accounts for 15% to 20% of sporadic colorectal cancer.49 These epigenetic modifications lead to hypermethylation of the promotor region of MLH1 in 70% of cases.50 The 4 MMR genes most commonly tested are MLH-1, MSH2, MSH6, and PMS2. Testing can be performed by immunohistochemistry or polymerase chain reaction.51 Across tumor histology and stage, MSI status is prognostic. Patients with MSI-high tumors have been shown to have improved prognosis and longer OS both in stage II and III disease52–54 and in the metastatic setting.55 However, despite this survival benefit, there is conflicting data as to whether patients with stage II, MSI-high colon cancer may benefit less from adjuvant chemotherapy. One early retrospective study compared outcomes of 70 patients with stage II and III disease and dMMR to those of 387 patients with stage II and III disease and proficient mismatch repair (pMMR). Adjuvant fluorouracil with leucovorin improved DFS for patients with pMMR (HR 0.67) but not for those with dMMR (HR 1.10). In addition, for patients with stage II disease and dMMR, the HR for OS was inferior at 2.95.56 Data collected from randomized clinical trials using fluorouracil-based adjuvant chemotherapy were analyzed in an attempt to predict benefit based on MSI status. Benefit was only seen in pMMR patients, with a HR of 0.72; this was not seen in the dMMR patients.57 Subsequent studies have had different findings and did not demonstrate a detrimental effect of fluorouracil in dMMR.58,59 For stage III patients, MSI status does not appear to affect benefit from chemotherapy, as analysis of data from the NSABP C-07 trial (Table 3) demonstrated benefit of FOLFOX (leucovorin, fluorouracil, oxaliplatin) in patients with dMMR status and stage III disease.59

Another genetic abnormality identified in colon cancers is chromosome 18q loss of heterozygosity (LOH). The presence of 18q LOH appears to be inversely associated with MSI-high status. Some reports have linked presence of 18q with worse outcome,60 but others question this, arguing the finding may simply be related to MSI status.61,62 This biomarker has not been established as a clear prognostic marker that can aid clinical decisions.

Most recently, expression of caudal-type homeobox transcription factor 2 (CDX2) has been reported as a novel prognostic and predictive tool. A 2015 report linked lack of expression of CDX2 to worse outcome; in this study, 5-year DFS was 41% in patients with CDX2-negative tumors versus 74% in the CDX2-positive tumors, with a HR of disease recurrence of 2.73 for CDX2-negative tumors.63 Similar numbers were observed in patients with stage II disease, with 5-year OS of 40% in patients with CDX2-negative tumors versus 70% in those with CDX2-positive tumors. Treatment of CDX2-negative patients with adjuvant chemotherapy improved outcomes: 5-year DFS in the stage II subgroup was 91% with chemotherapy versus 56% without, and in the stage III subgroup, 74% with chemotherapy versus 37% without. The authors concluded that patients with stage II and III colon cancer that is CDX2-negative may benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy. Importantly, CDX2-negativity is a rare event, occurring in only 6.9% of evaluable tumors.

RISK ASSESSMENT TOOLS

Several risk assessment tools have been developed in an attempt to aid clinical decision making regarding adjuvant chemotherapy for patients with stage II colon cancer. The Oncotype DX Colon Assay analyses a 12-gene signature in the pathologic sample and was developed with the goal to improve prognostication and aid in treatment decision making. The test utilizes reverse transcription-PCR on RNA extracted from the tumor.64 After evaluating 12 genes, a recurrence score is generated that predicts the risk of disease recurrence. This score was validated using data from 3 large clinical trials.65–67 Unlike the Oncotype Dx score used in breast cancer, the test in colon cancer has not been found to predict the benefit from chemotherapy and has not been incorporated widely into clinical practice.

Adjuvant! Online (available at www.adjuvantonline.com) is a web-based tool that combines clinical and histological features to estimate outcome. Calculations are based on US SEER tumor registry-reported outcomes.68 A second web-based tool, Numeracy (available at www.mayoclinic.com/calcs), was developed by the Mayo Clinic using pooled data from 7 randomized clinical trials including 3341 patients.68 Both tools seek to predict absolute benefit for patients treated with fluorouracil, though data suggests Adjuvant! Online may be more reliable in its predictive ability.69 Adjuvant! Online has also been validated in an Asian population70 and patients older than 70 years.71

MUTATIONAL ANALYSIS

Multiple mutations in proto-oncogenes have been found in colon cancer cells. One such proto-oncogene is BRAF, which encodes a serine-threonine kinase in the rapidly accelerated fibrosarcoma (RAF). Mutations in BRAF have been found in 5% to 10% of colon cancers and are associated with right-sided tumors.72 As a prognostic marker, some studies have associated BRAF mutations with worse prognosis, including shorter time to relapse and shorter OS.73,74 Two other proto-oncogenes are Kristen rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog (KRAS) and neuroblastoma rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog (NRAS), both of which encode proteins downstream of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR). KRAS and NRAS mutations have been shown to be predictive in the metastatic setting where they predict resistance to the EGFR inhibitors cetuximab and panitumumab.75,76 The effect of KRAS and NRAS mutations on outcome in stage II and III colon cancer is uncertain. Some studies suggest worse outcome in KRAS-mutated cancers,77 while others failed to demonstrate this finding.73

CASE PRESENTATION 1

A 53-year-old man with no past medical history presents to the emergency department with early satiety and generalized abdominal pain. Laboratory evaluation shows a microcytic anemia with normal white blood cell count, platelet count, renal function, and liver function tests. Computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis show a 4-cm mass in the transverse colon without obstruction and without abnormality in the liver. CT scan of the chest does not demonstrate pathologic lymphadenopathy or other findings. He undergoes robotic laparoscopic transverse colon resection and appendectomy. Pathology confirms a 3.5-cm focus of adenocarcinoma of the colon with invasion through the muscularis propria and 5 of 27 regional lymph nodes positive for adenocarcinoma and uninvolved proximal, distal, and radial margins. He is given a stage of IIIB pT3 pN2a M0 and referred to medical oncology for further management, where 6 months of adjuvant FOLFOX chemotherapy is recommended.

ADJUVANT CHEMOTHERAPY IN STAGE III COLON CANCER

Postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy is the standard of care for patients with stage III disease. In the 1960s, infusional fluorouracil was first used to treat inoperable colon cancer.78,79 After encouraging results, the agent was used both intraluminally and intravenously as an adjuvant therapy for patients undergoing resection with curative intent; however, only modest benefits were described.80,81 The National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP) C-01 trial (Table 3) was the first study to demonstrate a benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy in colon cancer. This study randomly assigned patients with stage II and III colon cancer to surgery alone, postoperative chemotherapy with fluorouracil, semustine, and vincristine (MOF), or postoperative bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG). DFS and OS were significantly improved with MOF chemotherapy.82 In 1990, a landmark study reported on outcomes after treatment of 1296 patients with stage III colon cancer with adjuvant fluorouracil and levamisole for 12 months. The combination was associated with a 41% reduction in risk of cancer recurrence and a 33% reduction in risk of death.83 The NSABP C-03 trial (Table 3) compared MOF to the combination of fluorouracil and leucovorin and demonstrated improved 3-year DFS (69% versus 73%) and 3-year OS (77% versus 84%) in patients with stage III disease.84 Building on these outcomes, the QUASAR study (Table 3) compared fluorouracil in combination with one of levamisole, low-dose leucovorin, or high-dose leucovorin. The study enrolled 4927 patients and found worse outcomes with fluorouracil plus levamisole and no difference in low-doseversus high-dose leucovorin.85 Levamisole fell out of use after associations with development of multifocal leukoencephalopathy,86 and was later shown to have inferior outcomes versus leucovorin when combined with fluorouracil.87,88 Intravenous fluorouracil has shown similar benefit when administered by bolus or infusion,89 although continuous infusion has been associated with lower incidence of severe toxicity.90 The efficacy of the oral fluoropyrimidine capecitabine has been shown to be equivalent to that of fluorouracil.91

Fluorouracil-based treatment remained the standard of care until the introduction of oxaliplatin in the mid-1990s. After encouraging results in the metastatic setting,92,93 the agent was moved to the adjuvant setting. The MOSAIC trial (Table 3) randomly assigned patients with stage II and III colon cancer to fluorouracil with leucovorin (FULV) versus FOLFOX given once every 2 weeks for 12 cycles. Analysis with respect to stage III patients showed a clear survival benefit, with a 10-year OS of 67.1% with FOLFOX chemotherapy versus 59% with fluorouracil and leucovorin.94,95 The NSABP C-07 (Table 3) trial used a similar trial design but employed bolus fluorouracil. More than 2400 patients with stage II and III colon cancer were randomly assigned to bolus FULV or bolus fluorouracil, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin (FLOX). The addition of oxaliplatin significantly improved outcomes, with 4-year DFS of 67% versus 71.8% for FULV and FLOX, respectively, and a HR of death of 0.80 with FLOX.59,96 The multicenter N016968 trial (Table 3) randomly assigned 1886 patients with stage III colon cancer to adjuvant capecitabine plus oxaliplatin (XELOX) or bolus fluorouracil plus leucovorin (FU/FA). The 3-year DFS was 70.9% versus 66.5% with XELOX and FU/FA, respectively, and 5-year OS was 77.6% versus 74.2%, respectively.97,98

In the metastatic setting, additional agents have shown efficacy, including irinotecan,99,100 bevacizumab,101,102 cetuximab,103,104 and regorafenib.105 This observation led to testing of these agents in earlier stage disease. The CALGB 89803 trial compared fluorouracil, leucovorin, and irinotecan to fluorouracil with leucovorin alone. No benefit in 5-year DFS or OS was seen.106 Similarly, infusional fluorouracil, leucovorin, and irinotecan (FOLFIRI) was not found to improve 5-year DFS as compared to fluorouracil with leucovorin alone in the PETACC-3 trial.107 The NSABP C-08 trial considered the addition of bevacizumab to FOLFOX. When compared to FOLFOX alone, the combination of bevacizumab to FOLFOX had similar 3-year DFS (77.9% versus 75.1%) and 5-year OS (82.5% versus 80.7%).108 This finding was confirmed in the Avant trial.109 The addition of cetuximab to FOLFOX was equally disappointing, as shown in the N0147 trial110 and PETACC-8 trial.111 Data on regorafenib in the adjuvant setting for stage III colon cancer is lacking; however, 2 ongoing clinical trials, NCT02425683 and NCT02664077, are each studying the use of regorafenib following completion of FOLFOX for patients with stage III disease.

Thus, after multiple trials comparing various regimens and despite attempts to improve outcomes by the addition of a third agent, the standard of care per National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines for management of stage III colon cancer remains 12 cycles of FOLFOX chemotherapy. Therapy should be initiated within 8 weeks of surgery. Data are emerging to support a short duration of therapy for patients with low-risk stage III tumors, as shown in an abstract presented at the 2017 American Society of Clinical Oncology annual meeting. The IDEA trial was a pooled analysis of 6 randomized clinical trials across multiple countries, all of which evaluated 3 versus 6 months of FOLFOX or capecitabine and oxaliplatin in the treatment of stage III colon cancer. The analysis was designed to test non-inferiority of 3 months of therapy as compared to 6 months. The analysis included 6088 patients across 244 centers in 6 countries. The overall analysis failed to establish noninferiority. The 3-year DFS rate was 74.6% for 3 months and 75.5% for 6 months, with a DFS HR of 1.07 and a confidence interval that did not meet the prespecified endpoint. Subgroup analysis suggested noninferiority for lower stage disease (T1–3 or N1) but not for higher stage disease (T4 or N2). Given the high rates of neuropathy with 6 months of oxaliplatin, these results suggest that 3 months of adjuvant therapy can be considered for patients with T1–3 or N1 disease in an attempt to limit toxicity.112

CASE PRESENTATION 2

A 57-year-old woman presents to the emergency department with fever and abdominal pain. CT of the abdomen and pelvis demonstrates a left-sided colonic mass with surrounding fat stranding and pelvic abscess. She is taken emergently for left hemicolectomy, cholecystectomy, and evacuation of pelvic abscess. Pathology reveals a 5-cm adenocarcinoma with invasion through the visceral peritoneum; 0/22 lymph nodes are involved. She is given a diagnosis of stage IIC and referred to medical oncology for further management. Due to her young age and presence of high-risk features, she is recommended adjuvant therapy with FOLFOX for 6 months.

ADJUVANT CHEMOTHERAPY IN STAGE II COLON CANCER

Because of excellent outcomes with surgical resection alone for stage II cancers, the use of adjuvant chemotherapy for patients with stage II disease is controversial. Limited prospective data is available to guide adjuvant treatment decisions for stage II patients. The QUASAR trial, which compared observation to adjuvant fluorouracil and leucovorin in patients with early-stage colon cancer, included 2963 patients with stage II disease and found a relative risk (RR) of death or recurrence of 0.82 and 0.78, respectively. Importantly, the absolute benefit of therapy was less than 5%.113 The IMPACT-B2 trial (Table 3) combined data from 5 separate trials and analyzed 1016 patients with stage II colon cancer who received fluorouracil with leucovorin or observation. Event-free survival was 0.86 versus 0.83 and 5-year OS was 82% versus 80%, suggesting no benefit.114 The benefit of addition of oxaliplatin to fluorouracil in stage II disease appears to be less than the benefit of adding this agent in the treatment of stage III CRC. As noted above, the MOSAIC trial randomly assigned patients with stage II and III colon cancer to receive adjuvant fluorouracil and leucovorin with or without oxaliplatin for 12 cycles. After a median follow-up of 9.5 years, 10-year OS rates for patients with stage II disease were 78.4% versus 79.5%. For patients with high-risk stage II disease (defined as T4, bowel perforation, or fewer than 10 lymph nodes examined), 10-year OS was 71.7% and 75.4% respectively, but these differences were not statistically significant.94