User login

Critical care units and long-term care facilities are on alert for cases of Candida auris, a novel fungal infection that is both dangerous to vulnerable patients and difficult to eradicate. The increased profile of C. auris is not a welcome development but is no surprise to critical care physicians.

This pathogen was first identified in 2009 and has since been found in increasing numbers of patients all over the world. As expected, cases of C. auris are on the rise in the United States.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention stated “Candida auris is an emerging fungus that presents a serious global health threat.” This is an opportunistic pathogen that hits critically ill patients and those with compromised immunity.

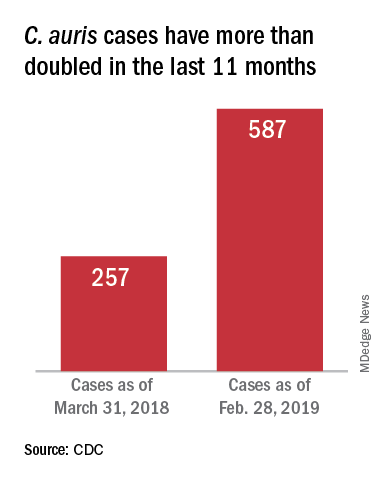

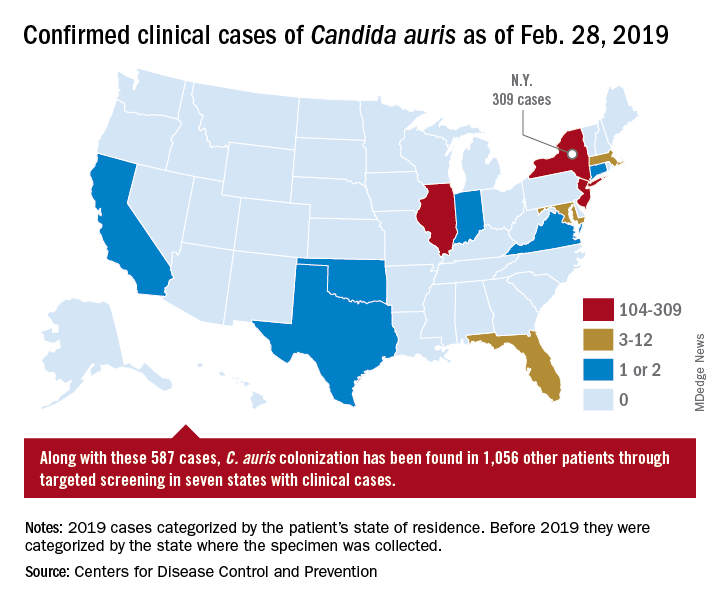

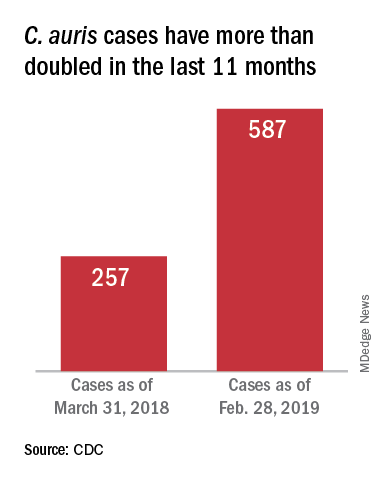

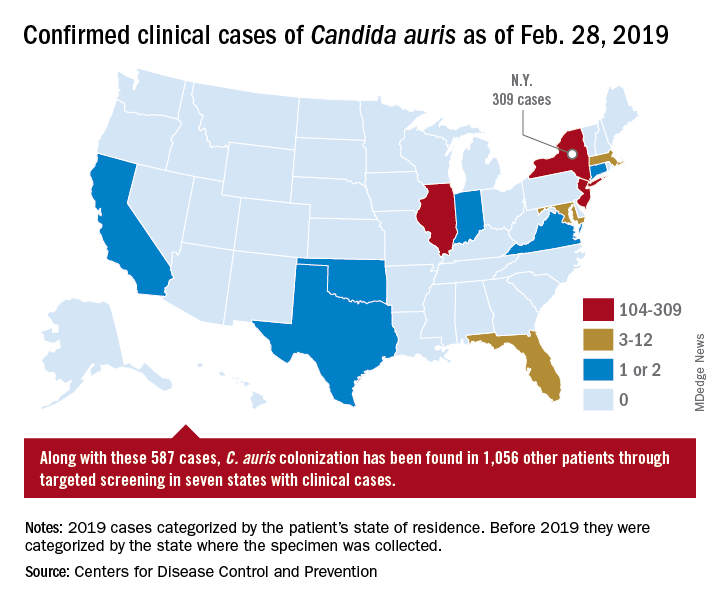

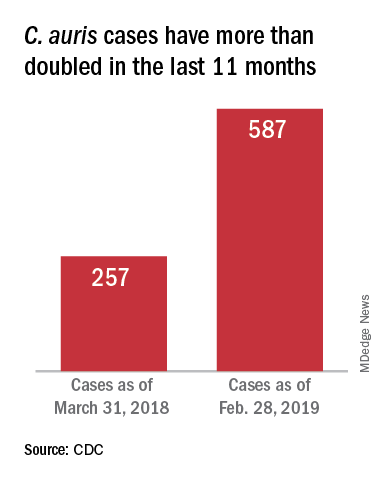

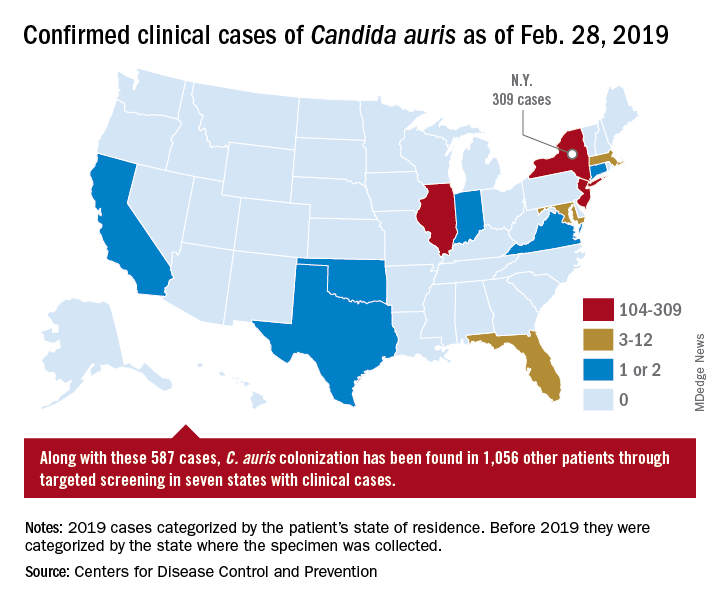

On March 29, 2019, CDC reported that confirmed clinical cases of C. auris in the United States have more than doubled over the past year, from 257 cases in 2018 to 587 cases with an additional 1,056 colonized patients identified as of February 2019. “Most C. auris cases in the United States have been detected in the New York City area, New Jersey, and the Chicago area. Strains of C. auris in the United States have been linked to other parts of the world. U.S. C. auris cases are a result of inadvertent introduction into the United States from a patient who recently received health care in a country where C. auris has been reported or a result of local spread after such an introduction.”

Case reports have found a mortality rate of up to 50% in patients with C. auris candidemia. The total number of cases is still small, but the trajectory is clear. The hunt is on in labs all over the world for optimal treatments and processes to handle outbreaks.

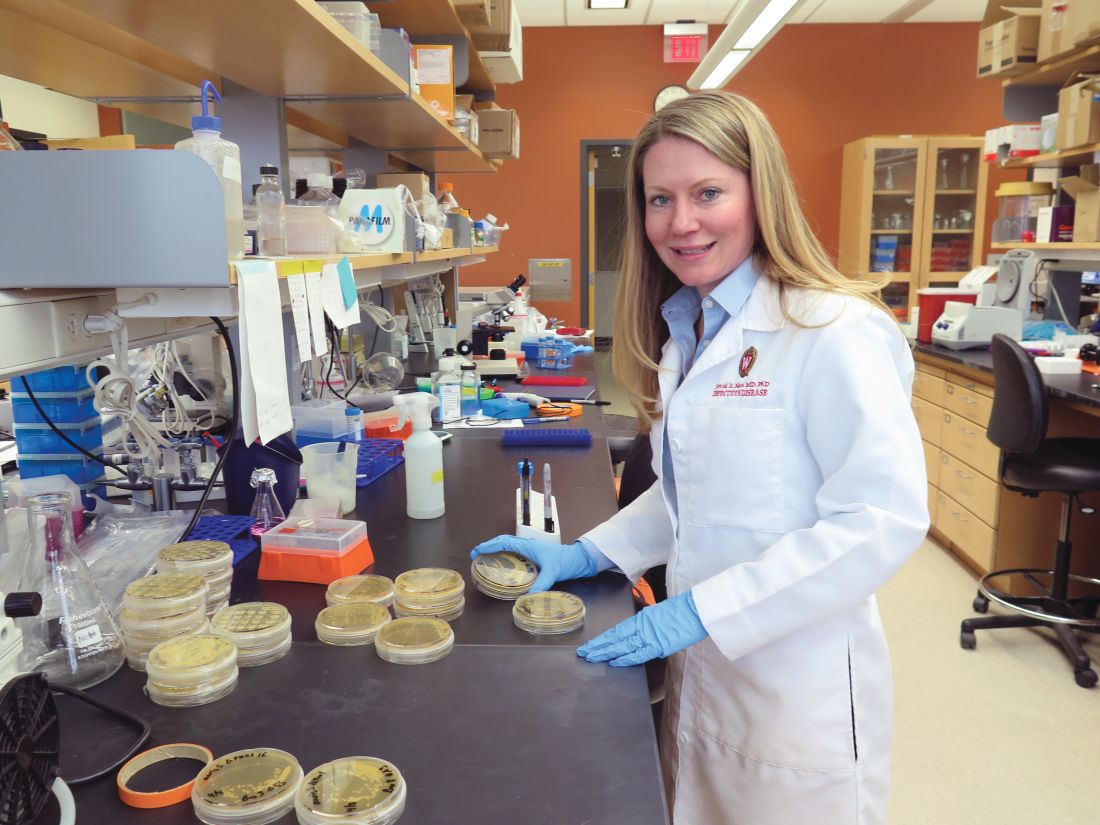

Jeniel Nett, MD, an infectious disease specialist, and a team of investigators at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, have focused their research on the characteristics of C. auris and its progression in patients and in medical facilities.

According to Dr. Nett, it’s not clear why this emerging threat has cropped up in multiple locations globally. “Candida auris was first recognized in 2009, in Japan, and relatively quickly we saw emergence of this species in relatively distant locations,” she said, adding that independent clades in these locations ruled out transmission as the source of the multiple outbreaks. Antifungal resistance is an epidemiologic area of concern and increased antifungal use may be a contributor, she said.

Once established, the organism is persistent: “It is found on mattresses, on bedsheets, IV poles, and a lot of reusable equipment,” said Dr. Nett in an interview. “It appears to persist in the environment for weeks – maybe longer.” In addition, “it seems to behave differently than a lot of the Candida species that we see; it readily colonizes the skin” to a much greater extent than does other Candida species, she said. “This allows it to be transmitted readily person to person, particularly in the hospitalized setting.” However, it can also colonize both the urinary and respiratory tracts, she said.

Which patients are susceptible to C. auris candidemia? “Many of these patients have undergone multiple procedures; they may have undergone mechanical ventilation as well as different surgical procedures,” said Dr. Nett. Affected patients often have received many rounds of antibiotic and antifungal treatment as well, she said, and may have an underlying illness like diabetes or malignancy.

Studies of C. auris outbreaks have begun to appear in the literature and give clinicians some perspective on the progression of an outbreak and potential strategies for containment. A prospective cohort study of a large outbreak of C. auris was conducted by Alba Ruiz-Gaitán, MD, and her colleagues at La Fe University and Polytechnic Hospital, Valencia, Spain (Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2019 Apr;17[4]:295-305). The researchers followed 114 patients who were colonized with C. auris or had C. auris candidemia. The patients were compared with 114 case-matched controls within the hospital’s adult surgical and medical intensive care units over an 11-month period during the hospital’s protracted outbreak.

The investigators found a crude mortality rate of 58.5% at 30 days for patients with C. auris candidemia. All isolates in the study were completely resistant to fluconazole and had reduced susceptibility to voriconazole.

In critical care units at Hospital La Fe, investigators found C. auris on 25% of blood pressure cuffs, 10% of patient tables and keyboards, and 8% of infusion pumps.

Among the patients at Hospital La Fe, multivariable analysis revealed that those most likely to develop C. auris colonization or candidemia were individuals with polytrauma, cardiovascular disease, and cancer.

Patients receiving parenteral nutrition (odds ratio, 3.49), mechanical ventilation (OR, 2.43), and especially those having indwelling central venous catheters (OR, 13.48) were more likely to be colonized or have candidemia as well, according to Dr. Ruiz-Gaitán and her coauthors.

Once identified, how should C. auris be treated? “The majority of strains – upward of 90% – are resistant to fluconazole,” said Dr. Nett. “Moreover, 30%-50% of them are resistant to another antifungal, often amphotericin B. The isolates that we see in the United States are most often susceptible to an echinocandin, and echinocandins remain the choice for treatment of Candida auris pending susceptibility tests.”

However, in Valencia, “The susceptibility to echinocandins presented interesting features. These antifungals were not fungicidal against C. auris,” wrote Dr. Ruiz-Gaitán and her colleagues. They found that for caspofungin, “most isolates presented a clear paradoxical growth after 24 hours of incubation.” Additionally, fungal growth was inhibited at lower caspofungin concentrations, but rebounded at higher levels. Similar patterns were seen for anidulafungin and micafungin, they said.

These findings meant that Hospital La Fe patients received initial treatment with echinocandins, with the addition of liposomal amphotericin B or isavuconazole if candidemia persisted or clinical response was not seen, wrote the investigators.

Patient presentation is similar to other forms of candidiasis, said Dr. Nett. “Patients often have fever, chills, leukocytosis, and this persists despite antibacterial therapy… If Candida auris is suspected, the first course of action would be to place the patient in isolation, and laboratory staff should be alerted regarding the diagnosis.”

Most large clinical laboratories, she said, can now detect C. auris. Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization–time of flight is the identification technique of choice, provided that the databases are updated.

Smaller laboratories that use phenotypic tests may misidentify C. auris as another Candida species, or even as Saccharomyces cerevisiae – common beer yeast. Facilities without matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization can find guidance for interpretation of phenotypic testing on the CDC website as well, said Dr. Nett.

After experiencing what they believe to be the largest C. auris outbreak at a single European hospital, Dr. Ruiz-Gaitán and her colleagues offered best-practice tips for treatment of patients with C. auris candidemia. These include removing mechanical devices as early as is safely practical; performing ophthalmologic examinations for endophthalmitis, a known C. auris complication; obtaining blood cultures every other day to track antimicrobial therapy to the point of sterilization; and searching for metastatic foci if blood cultures remain positive.

All instances of C. auris laboratory identification should be reported to the CDC at candidaauris@cdc.gov, and to local and state health agencies. The CDC recommends strict isolation and cleaning protocols, similar to those used for the spore-forming Clostridium difficile.

Dr. Nett reported funding support from the National Institutes of Health, the Burroughs Wellcome Fund, and the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation. She reported no conflicts of interest. Dr. Ruiz-Gaitán and her collaborators reported funding from Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Spain, and the Spanish Ministry of Science and University. They reported no conflicts of interest.

Critical care units and long-term care facilities are on alert for cases of Candida auris, a novel fungal infection that is both dangerous to vulnerable patients and difficult to eradicate. The increased profile of C. auris is not a welcome development but is no surprise to critical care physicians.

This pathogen was first identified in 2009 and has since been found in increasing numbers of patients all over the world. As expected, cases of C. auris are on the rise in the United States.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention stated “Candida auris is an emerging fungus that presents a serious global health threat.” This is an opportunistic pathogen that hits critically ill patients and those with compromised immunity.

On March 29, 2019, CDC reported that confirmed clinical cases of C. auris in the United States have more than doubled over the past year, from 257 cases in 2018 to 587 cases with an additional 1,056 colonized patients identified as of February 2019. “Most C. auris cases in the United States have been detected in the New York City area, New Jersey, and the Chicago area. Strains of C. auris in the United States have been linked to other parts of the world. U.S. C. auris cases are a result of inadvertent introduction into the United States from a patient who recently received health care in a country where C. auris has been reported or a result of local spread after such an introduction.”

Case reports have found a mortality rate of up to 50% in patients with C. auris candidemia. The total number of cases is still small, but the trajectory is clear. The hunt is on in labs all over the world for optimal treatments and processes to handle outbreaks.

Jeniel Nett, MD, an infectious disease specialist, and a team of investigators at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, have focused their research on the characteristics of C. auris and its progression in patients and in medical facilities.

According to Dr. Nett, it’s not clear why this emerging threat has cropped up in multiple locations globally. “Candida auris was first recognized in 2009, in Japan, and relatively quickly we saw emergence of this species in relatively distant locations,” she said, adding that independent clades in these locations ruled out transmission as the source of the multiple outbreaks. Antifungal resistance is an epidemiologic area of concern and increased antifungal use may be a contributor, she said.

Once established, the organism is persistent: “It is found on mattresses, on bedsheets, IV poles, and a lot of reusable equipment,” said Dr. Nett in an interview. “It appears to persist in the environment for weeks – maybe longer.” In addition, “it seems to behave differently than a lot of the Candida species that we see; it readily colonizes the skin” to a much greater extent than does other Candida species, she said. “This allows it to be transmitted readily person to person, particularly in the hospitalized setting.” However, it can also colonize both the urinary and respiratory tracts, she said.

Which patients are susceptible to C. auris candidemia? “Many of these patients have undergone multiple procedures; they may have undergone mechanical ventilation as well as different surgical procedures,” said Dr. Nett. Affected patients often have received many rounds of antibiotic and antifungal treatment as well, she said, and may have an underlying illness like diabetes or malignancy.

Studies of C. auris outbreaks have begun to appear in the literature and give clinicians some perspective on the progression of an outbreak and potential strategies for containment. A prospective cohort study of a large outbreak of C. auris was conducted by Alba Ruiz-Gaitán, MD, and her colleagues at La Fe University and Polytechnic Hospital, Valencia, Spain (Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2019 Apr;17[4]:295-305). The researchers followed 114 patients who were colonized with C. auris or had C. auris candidemia. The patients were compared with 114 case-matched controls within the hospital’s adult surgical and medical intensive care units over an 11-month period during the hospital’s protracted outbreak.

The investigators found a crude mortality rate of 58.5% at 30 days for patients with C. auris candidemia. All isolates in the study were completely resistant to fluconazole and had reduced susceptibility to voriconazole.

In critical care units at Hospital La Fe, investigators found C. auris on 25% of blood pressure cuffs, 10% of patient tables and keyboards, and 8% of infusion pumps.

Among the patients at Hospital La Fe, multivariable analysis revealed that those most likely to develop C. auris colonization or candidemia were individuals with polytrauma, cardiovascular disease, and cancer.

Patients receiving parenteral nutrition (odds ratio, 3.49), mechanical ventilation (OR, 2.43), and especially those having indwelling central venous catheters (OR, 13.48) were more likely to be colonized or have candidemia as well, according to Dr. Ruiz-Gaitán and her coauthors.

Once identified, how should C. auris be treated? “The majority of strains – upward of 90% – are resistant to fluconazole,” said Dr. Nett. “Moreover, 30%-50% of them are resistant to another antifungal, often amphotericin B. The isolates that we see in the United States are most often susceptible to an echinocandin, and echinocandins remain the choice for treatment of Candida auris pending susceptibility tests.”

However, in Valencia, “The susceptibility to echinocandins presented interesting features. These antifungals were not fungicidal against C. auris,” wrote Dr. Ruiz-Gaitán and her colleagues. They found that for caspofungin, “most isolates presented a clear paradoxical growth after 24 hours of incubation.” Additionally, fungal growth was inhibited at lower caspofungin concentrations, but rebounded at higher levels. Similar patterns were seen for anidulafungin and micafungin, they said.

These findings meant that Hospital La Fe patients received initial treatment with echinocandins, with the addition of liposomal amphotericin B or isavuconazole if candidemia persisted or clinical response was not seen, wrote the investigators.

Patient presentation is similar to other forms of candidiasis, said Dr. Nett. “Patients often have fever, chills, leukocytosis, and this persists despite antibacterial therapy… If Candida auris is suspected, the first course of action would be to place the patient in isolation, and laboratory staff should be alerted regarding the diagnosis.”

Most large clinical laboratories, she said, can now detect C. auris. Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization–time of flight is the identification technique of choice, provided that the databases are updated.

Smaller laboratories that use phenotypic tests may misidentify C. auris as another Candida species, or even as Saccharomyces cerevisiae – common beer yeast. Facilities without matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization can find guidance for interpretation of phenotypic testing on the CDC website as well, said Dr. Nett.

After experiencing what they believe to be the largest C. auris outbreak at a single European hospital, Dr. Ruiz-Gaitán and her colleagues offered best-practice tips for treatment of patients with C. auris candidemia. These include removing mechanical devices as early as is safely practical; performing ophthalmologic examinations for endophthalmitis, a known C. auris complication; obtaining blood cultures every other day to track antimicrobial therapy to the point of sterilization; and searching for metastatic foci if blood cultures remain positive.

All instances of C. auris laboratory identification should be reported to the CDC at candidaauris@cdc.gov, and to local and state health agencies. The CDC recommends strict isolation and cleaning protocols, similar to those used for the spore-forming Clostridium difficile.

Dr. Nett reported funding support from the National Institutes of Health, the Burroughs Wellcome Fund, and the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation. She reported no conflicts of interest. Dr. Ruiz-Gaitán and her collaborators reported funding from Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Spain, and the Spanish Ministry of Science and University. They reported no conflicts of interest.

Critical care units and long-term care facilities are on alert for cases of Candida auris, a novel fungal infection that is both dangerous to vulnerable patients and difficult to eradicate. The increased profile of C. auris is not a welcome development but is no surprise to critical care physicians.

This pathogen was first identified in 2009 and has since been found in increasing numbers of patients all over the world. As expected, cases of C. auris are on the rise in the United States.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention stated “Candida auris is an emerging fungus that presents a serious global health threat.” This is an opportunistic pathogen that hits critically ill patients and those with compromised immunity.

On March 29, 2019, CDC reported that confirmed clinical cases of C. auris in the United States have more than doubled over the past year, from 257 cases in 2018 to 587 cases with an additional 1,056 colonized patients identified as of February 2019. “Most C. auris cases in the United States have been detected in the New York City area, New Jersey, and the Chicago area. Strains of C. auris in the United States have been linked to other parts of the world. U.S. C. auris cases are a result of inadvertent introduction into the United States from a patient who recently received health care in a country where C. auris has been reported or a result of local spread after such an introduction.”

Case reports have found a mortality rate of up to 50% in patients with C. auris candidemia. The total number of cases is still small, but the trajectory is clear. The hunt is on in labs all over the world for optimal treatments and processes to handle outbreaks.

Jeniel Nett, MD, an infectious disease specialist, and a team of investigators at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, have focused their research on the characteristics of C. auris and its progression in patients and in medical facilities.

According to Dr. Nett, it’s not clear why this emerging threat has cropped up in multiple locations globally. “Candida auris was first recognized in 2009, in Japan, and relatively quickly we saw emergence of this species in relatively distant locations,” she said, adding that independent clades in these locations ruled out transmission as the source of the multiple outbreaks. Antifungal resistance is an epidemiologic area of concern and increased antifungal use may be a contributor, she said.

Once established, the organism is persistent: “It is found on mattresses, on bedsheets, IV poles, and a lot of reusable equipment,” said Dr. Nett in an interview. “It appears to persist in the environment for weeks – maybe longer.” In addition, “it seems to behave differently than a lot of the Candida species that we see; it readily colonizes the skin” to a much greater extent than does other Candida species, she said. “This allows it to be transmitted readily person to person, particularly in the hospitalized setting.” However, it can also colonize both the urinary and respiratory tracts, she said.

Which patients are susceptible to C. auris candidemia? “Many of these patients have undergone multiple procedures; they may have undergone mechanical ventilation as well as different surgical procedures,” said Dr. Nett. Affected patients often have received many rounds of antibiotic and antifungal treatment as well, she said, and may have an underlying illness like diabetes or malignancy.

Studies of C. auris outbreaks have begun to appear in the literature and give clinicians some perspective on the progression of an outbreak and potential strategies for containment. A prospective cohort study of a large outbreak of C. auris was conducted by Alba Ruiz-Gaitán, MD, and her colleagues at La Fe University and Polytechnic Hospital, Valencia, Spain (Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2019 Apr;17[4]:295-305). The researchers followed 114 patients who were colonized with C. auris or had C. auris candidemia. The patients were compared with 114 case-matched controls within the hospital’s adult surgical and medical intensive care units over an 11-month period during the hospital’s protracted outbreak.

The investigators found a crude mortality rate of 58.5% at 30 days for patients with C. auris candidemia. All isolates in the study were completely resistant to fluconazole and had reduced susceptibility to voriconazole.

In critical care units at Hospital La Fe, investigators found C. auris on 25% of blood pressure cuffs, 10% of patient tables and keyboards, and 8% of infusion pumps.

Among the patients at Hospital La Fe, multivariable analysis revealed that those most likely to develop C. auris colonization or candidemia were individuals with polytrauma, cardiovascular disease, and cancer.

Patients receiving parenteral nutrition (odds ratio, 3.49), mechanical ventilation (OR, 2.43), and especially those having indwelling central venous catheters (OR, 13.48) were more likely to be colonized or have candidemia as well, according to Dr. Ruiz-Gaitán and her coauthors.

Once identified, how should C. auris be treated? “The majority of strains – upward of 90% – are resistant to fluconazole,” said Dr. Nett. “Moreover, 30%-50% of them are resistant to another antifungal, often amphotericin B. The isolates that we see in the United States are most often susceptible to an echinocandin, and echinocandins remain the choice for treatment of Candida auris pending susceptibility tests.”

However, in Valencia, “The susceptibility to echinocandins presented interesting features. These antifungals were not fungicidal against C. auris,” wrote Dr. Ruiz-Gaitán and her colleagues. They found that for caspofungin, “most isolates presented a clear paradoxical growth after 24 hours of incubation.” Additionally, fungal growth was inhibited at lower caspofungin concentrations, but rebounded at higher levels. Similar patterns were seen for anidulafungin and micafungin, they said.

These findings meant that Hospital La Fe patients received initial treatment with echinocandins, with the addition of liposomal amphotericin B or isavuconazole if candidemia persisted or clinical response was not seen, wrote the investigators.

Patient presentation is similar to other forms of candidiasis, said Dr. Nett. “Patients often have fever, chills, leukocytosis, and this persists despite antibacterial therapy… If Candida auris is suspected, the first course of action would be to place the patient in isolation, and laboratory staff should be alerted regarding the diagnosis.”

Most large clinical laboratories, she said, can now detect C. auris. Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization–time of flight is the identification technique of choice, provided that the databases are updated.

Smaller laboratories that use phenotypic tests may misidentify C. auris as another Candida species, or even as Saccharomyces cerevisiae – common beer yeast. Facilities without matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization can find guidance for interpretation of phenotypic testing on the CDC website as well, said Dr. Nett.

After experiencing what they believe to be the largest C. auris outbreak at a single European hospital, Dr. Ruiz-Gaitán and her colleagues offered best-practice tips for treatment of patients with C. auris candidemia. These include removing mechanical devices as early as is safely practical; performing ophthalmologic examinations for endophthalmitis, a known C. auris complication; obtaining blood cultures every other day to track antimicrobial therapy to the point of sterilization; and searching for metastatic foci if blood cultures remain positive.

All instances of C. auris laboratory identification should be reported to the CDC at candidaauris@cdc.gov, and to local and state health agencies. The CDC recommends strict isolation and cleaning protocols, similar to those used for the spore-forming Clostridium difficile.

Dr. Nett reported funding support from the National Institutes of Health, the Burroughs Wellcome Fund, and the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation. She reported no conflicts of interest. Dr. Ruiz-Gaitán and her collaborators reported funding from Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Spain, and the Spanish Ministry of Science and University. They reported no conflicts of interest.