User login

The Case

An 85-year-old woman with stroke, functional quadriplegia, and diabetes mellitus presents with altered mental status. She is febrile (38.5°C) with leukocytosis (14,400 cells/mm3) and has a 5 cm x 4 cm x 2 cm Stage III malodorous sacral ulcer without surrounding erythema, tunneling, or pain. The ulcer base is partially covered by green slough. How should this pressure ulcer be evaluated and treated?

Overview

Pressure ulcers in vulnerable populations, such as the elderly and those with limited mobility, are exceedingly common. In the acute-care setting, the incidence of pressure ulcers ranges from 0.4% to 38%, with 2.5 million cases treated annually at an estimated cost of $11 billion per year.1,2 Moreover, as of Oct. 1, 2008, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) guideline states that hospitals will no longer receive additional payment when a hospitalized patient develops Stage III or IV pressure ulcers that are not present on admission.

A pressure ulcer is a localized injury to skin and underlying soft tissue over a bony prominence due to sustained external pressure.3 Prolonged pressure on these weight-bearing areas leads to reduced blood flow, ischemia, cell death, and necrosis of local tissues.4 Risk factors for developing pressure ulcers include increased external pressure, shear, friction, moisture, poor perfusion, immobility, incontinence, malnutrition, and impaired mental status.4 Inadequately treated pressure ulcers can lead to pain, tunneling, fistula formation, disfigurement, infection, prolonged hospitalization, lower quality of life, and increased mortality.4

Because of the significant morbidities and high costs associated with the care of pressure ulcers in acute care, hospitalists must be familiar with the assessment and treatment of pressure ulcers in vulnerable patients.

Review of the Data

The management of pressure ulcers in the hospitalized patient starts with a comprehensive assessment of the patient’s medical comorbidities, risk factors, and wound-staging. Considerations must be given to differentiate an infected pressure ulcer from a noninfected ulcer. These evaluations then guide the appropriate treatments of pressure ulcers, including the prevention of progression or formation of new ulcers, debridement, application of wound dressing, and antibiotic use.

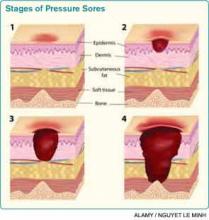

Assessing pressure ulcer stage. The National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (NPUAP) Classification System is the most commonly used staging tool. It describes four stages of pressure ulcers (see Table 1).3 A Stage 1 pressure ulcer is characterized by intact skin with nonblanchable erythema and may be discolored, painful, soft, firm, and warmer or cooler compared to adjacent area. A Stage II pressure ulcer presents with partial thickness skin loss with a shallow red-pink wound bed without slough, or as an intact or ruptured serum-filled blister. Stage II pressure ulcers do not include skin tears, tape burns, macerations, or excoriations. A Stage III pressure ulcer has full thickness skin loss with or without visible subcutaneous fat. Bone, tendon, or muscle are not exposed or directly palpable. Slough may be present but it does not obscure the depth of ulcer. Deep ulcers can develop in anatomical regions with high adiposity, such as the pelvic girdle. A Stage IV pressure ulcer has full thickness tissue loss with exposed and palpable bone, tendon, or muscle. Slough, eschar, undermining, and tunneling may be present. The depth of a Stage IV ulcer varies depending on anatomical location and adiposity. Stage IV ulcers also create a nidus for osteomyelitis.

NPUAP describes two additional categories of pressure ulcers: unstageable and deep tissue injury.3 An unstageable ulcer has full thickness skin or tissue loss of unknown depth because the wound base is completely obscured by slough or eschar. The ulcer can only be accurately categorized as Stage III or IV after sufficient slough or eschar is removed to identify wound depth. Lastly, suspected deep tissue injury describes a localized area of discolored intact skin (purple or maroon) or blood-filled blister due to damage of underlying tissue from pressure or shear.

Diagnosing infected pressure ulcers. Pressure ulcer infection delays wound healing and increases risks for sepsis, cellulitis, osteomyelitis, and death.5,6 Clinical evidence of soft tissue involvement, such as erythema, warmth, tenderness, foul odor, or purulent discharge, and systemic inflammatory response (fever, tachycardia, or leukocytosis) are suggestive of a wound infection.3,5 However, these clinical signs may be absent and thus make the distinction between chronic wound and infected pressure ulcer difficult.7 Delayed healing with friable granulation tissue and increased pain in a treated wound may be the only signs of a pressure ulcer infection.3,5,7

Routine laboratory tests (i.e. white blood cell count, C-reactive protein, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate) are neither sensitive nor specific in diagnosing wound infection. Moreover, because pressure ulcers are typically colonized with ≥105 organisms/mL of normal skin flora and bacteria from adjacent gastrointestinal or urogenital environments, swab cultures identify colonizing organisms and are not recommended as a diagnostic test for pressure ulcer microbiologic evaluation.5,6 If microbiological data are needed to guide antibiotic use, cultures of blood, bone, or deep tissue biopsied from a surgically debrided wound should be used.5 Importantly, a higher index of suspicion should be maintained for infection of Stage III or IV pressure ulcers because they are more commonly infected than Stage I or II ulcers.3

Prevention. The prevention of wound progression is essential in treating acute, chronic, or infected pressure ulcers. Although management guidelines are limited by few high-quality, randomized controlled trials, NPUAP recommends a number of prevention strategies targeting risk factors that contribute to pressure ulcer development.2,3,8

For all bed-bound and chair-bound persons with impaired ability to self-reposition, risk assessment for pressure ulcer should be done on admission and repeated every 24 hours. The presence of such risk factors as immobility, shear, friction, moisture, incontinence, and malnutrition should be used to guide preventive treatments. Pressure relief on an ulcer can be achieved by repositioning the immobile patient at one- to two-hour intervals. Pressure-redistributing support surfaces (static, overlays, or dynamic) reduce tissue pressure and decrease overall incidence of pressure ulcers. Due to a lack of relative efficacy data, the selection of a support surface should be determined by the patient’s individual needs in order to reduce pressure and shear.3 For instance, dynamic support is an appropriate surface for an immobile patient with multiple or nonhealing ulcers. Shearing force and friction can be reduced by limiting head-of-bed elevation to <30° and using such transfer aids as bed linens while repositioning patients. The use of pillows, foam wedges, or other devices should be used to eliminate direct contact of bony prominences or reduce pressure on heels.8

Skin care should be optimized to limit excessive dryness or moisture. This includes using moisturizers for dry skin, particularly for the sacrum, and implementing bowel and bladder programs and absorbent underpads in patients with bowel or bladder incontinence.2 Given that patients with pressure ulcers are in a catabolic state, those who are nutritionally compromised may benefit from nutritional supplementation.3 Lastly, appropriate use of local and systemic pain regimen for painful pressure ulcers can improve patient cooperation in repositioning, dressing change, and quality of life.

Debridement. Wound debridement removes necrotic tissue often present in infected or chronic pressure ulcers, reduces risk for further infection, and promotes granulation tissue formation and wound healing. Debridement, however, is not indicated for ulcers of an ischemic limb or dry eschar of the heel, due to propensity for complications.3,4 The five common debridement methods are sharp, mechanical, autolytic, enzymatic, and biosurgical. The debridement method of choice is determined by clinician preference and availability.4

Sharp debridement results in rapid removal of large amounts of nonviable necrotic tissues and eschar using sharp instruments and, therefore, is indicated if wound infection or sepsis is present. Mechanical debridement by wet-to-dry dressing or whirlpool nonselectively removes granulation tissue and, thus, should be used cautiously. Autolytic debridement uses occlusive dressings (i.e. hydrocolloid or hydrogel) to maintain a moist wound environment in order to optimize the body’s inherent ability to selectively self-digest necrotic tissues. Enzymatic debridement with concentrated topical proteolytic enzymes (i.e. collagenase) digests necrotic tissues and achieves faster debridement than autolysis while being less invasive than surgical intervention. Biosurgery utilizes maggots (i.e. Lucilia sericata) that produce enzymes to effectively debride necrotic tissues.

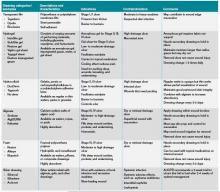

Wound care and dressing. Pressure ulcers should be cleansed with each dressing change using such physiologic solutions as normal saline. Cleansing with antimicrobial solutions for ulcers with large necrotic debris or infection needs to be thoughtfully administered due to the potential impairment on wound healing.4 Wound dressing should maintain a moist wound environment to allow epithelialization and limit excessive exudates in order to prevent maceration. Although there are many categories of moisture retentive dressings, their comparative effectiveness remain unclear.4 Table 2 summarizes characteristics of common wound dressings and their applications.

Antibiotic use. Topical antibiotics are appropriate for Stage III or IV ulcers with signs of local infection, including periwound erythema and friable granulation tissue.4 The Agency for Health Care Policy and Research recommends a two-week trial of a topical antibiotic, such as silver sulfadiazine, for pressure ulcers that fail to heal after two to four weeks of optimal care.6 Systemic antibiotics should be used for patients who demonstrate evidence of systemic infection including sepsis, osteomyelitis, or cellulitis with associated fever and leukocytosis. The choice of systemic antibiotics should be based on cultures from blood, bone, or deep tissue biopsied from a surgically debrided wound.4,6

Back to the Case

The patient was hospitalized for altered mental status. She was at high risk for the progression of her sacral ulcer and the development of new pressure ulcers due to immobility, incontinence, malnutrition, and impaired mental status. The sacral wound was a chronic, Stage III pressure ulcer without evidence of local tissue infection. However, the presence of leukocytosis and fever were suggestive of an underlying infection. Her urine analysis was consistent with a urinary tract infection.

Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole was administered with subsequent resolution of leukocytosis, fever, and delirium. The sacral ulcer was cleansed with normal saline and covered with hydrocolloid dressing every 72 hours in order to maintain a moist wound environment and facilitate autolysis. Preventive interventions guided by her risk factors for pressure ulcer were implemented. Interventions included:

- Daily skin and wound assessment;

- Pressure relief with repositioning every two hours;

- Use of a dynamic support surface;

- Head-of-bed elevation of no more than <30° to reduce shear and friction;

- Use of transfer aids;

- Use of devices to eliminate direct contact of bony prominences;

- Optimizing skin care with moisturizers for dry skin and frequent changing of absorbent under pads for incontinence; and

- Consulting nutrition service to optimize nutritional intake.

Bottom Line

Assessments of pressure ulcer stage, wound infection, and risk factors guide targeted therapeutic interventions that facilitate wound healing and prevent new pressure ulcer formation.

Dr. Prager is a fellow in the Brookdale Department of Geriatrics and Palliative Medicine at Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York City. Dr. Ko is a hospitalist and an assistant professor in the Brookdale Department of Geriatrics and Palliative Medicine at Mount Sinai.

References

- Pressure ulcers in America: prevalence, incidence, and implications for the future. An executive summary of the National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel monograph. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2001;14(4):208-215.

- Reddy M, Gill SS, Rochon PA. Preventing pressure ulcers: a systematic review. JAMA. 2006;296(8):974-984.

- European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel and National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel. Treatment of Pressure Ulcers: Quick Reference Guide. Washington, D.C.: National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel; 2009.

- Bates-Jensen BM. Chapter 58. Pressure Ulcers. In: Halter JB, Ouslander JG, Tinetti ME, Studenski S, High KP, Asthana S, eds. Hazzard’s Geriatric Medicine and Gerontology. 6th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2009.

- Livesley NJ, Chow AW. Infected pressure ulcers in elderly individuals. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;35(11):1390-1396.

- Agency for Health Care Policy and Research (AHCPR). Treatment of Pressure Ulcers. Clinical Practice Guideline Number 15. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 1994.

- Reddy M, Gill SS, Wu W, Kalkar SR, Rochon PA. Does this patient have an infection of a chronic wound? JAMA. 2012;307(6):605-611.

- National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel. Pressure Ulcer Prevention Points. National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel website. Available at: http://www.npuap.org/resources/educational-and-clinical-resources/pressure-ulcer-prevention-points/. Accessed Aug. 1, 2012.

- Reuben DB, Herr KA, Pacala JT, et al. Skin Ulcers. In: Geriatrics At Your Fingertips. 12th ed. New York: The American Geriatrics Society; 2010.

The Case

An 85-year-old woman with stroke, functional quadriplegia, and diabetes mellitus presents with altered mental status. She is febrile (38.5°C) with leukocytosis (14,400 cells/mm3) and has a 5 cm x 4 cm x 2 cm Stage III malodorous sacral ulcer without surrounding erythema, tunneling, or pain. The ulcer base is partially covered by green slough. How should this pressure ulcer be evaluated and treated?

Overview

Pressure ulcers in vulnerable populations, such as the elderly and those with limited mobility, are exceedingly common. In the acute-care setting, the incidence of pressure ulcers ranges from 0.4% to 38%, with 2.5 million cases treated annually at an estimated cost of $11 billion per year.1,2 Moreover, as of Oct. 1, 2008, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) guideline states that hospitals will no longer receive additional payment when a hospitalized patient develops Stage III or IV pressure ulcers that are not present on admission.

A pressure ulcer is a localized injury to skin and underlying soft tissue over a bony prominence due to sustained external pressure.3 Prolonged pressure on these weight-bearing areas leads to reduced blood flow, ischemia, cell death, and necrosis of local tissues.4 Risk factors for developing pressure ulcers include increased external pressure, shear, friction, moisture, poor perfusion, immobility, incontinence, malnutrition, and impaired mental status.4 Inadequately treated pressure ulcers can lead to pain, tunneling, fistula formation, disfigurement, infection, prolonged hospitalization, lower quality of life, and increased mortality.4

Because of the significant morbidities and high costs associated with the care of pressure ulcers in acute care, hospitalists must be familiar with the assessment and treatment of pressure ulcers in vulnerable patients.

Review of the Data

The management of pressure ulcers in the hospitalized patient starts with a comprehensive assessment of the patient’s medical comorbidities, risk factors, and wound-staging. Considerations must be given to differentiate an infected pressure ulcer from a noninfected ulcer. These evaluations then guide the appropriate treatments of pressure ulcers, including the prevention of progression or formation of new ulcers, debridement, application of wound dressing, and antibiotic use.

Assessing pressure ulcer stage. The National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (NPUAP) Classification System is the most commonly used staging tool. It describes four stages of pressure ulcers (see Table 1).3 A Stage 1 pressure ulcer is characterized by intact skin with nonblanchable erythema and may be discolored, painful, soft, firm, and warmer or cooler compared to adjacent area. A Stage II pressure ulcer presents with partial thickness skin loss with a shallow red-pink wound bed without slough, or as an intact or ruptured serum-filled blister. Stage II pressure ulcers do not include skin tears, tape burns, macerations, or excoriations. A Stage III pressure ulcer has full thickness skin loss with or without visible subcutaneous fat. Bone, tendon, or muscle are not exposed or directly palpable. Slough may be present but it does not obscure the depth of ulcer. Deep ulcers can develop in anatomical regions with high adiposity, such as the pelvic girdle. A Stage IV pressure ulcer has full thickness tissue loss with exposed and palpable bone, tendon, or muscle. Slough, eschar, undermining, and tunneling may be present. The depth of a Stage IV ulcer varies depending on anatomical location and adiposity. Stage IV ulcers also create a nidus for osteomyelitis.

NPUAP describes two additional categories of pressure ulcers: unstageable and deep tissue injury.3 An unstageable ulcer has full thickness skin or tissue loss of unknown depth because the wound base is completely obscured by slough or eschar. The ulcer can only be accurately categorized as Stage III or IV after sufficient slough or eschar is removed to identify wound depth. Lastly, suspected deep tissue injury describes a localized area of discolored intact skin (purple or maroon) or blood-filled blister due to damage of underlying tissue from pressure or shear.

Diagnosing infected pressure ulcers. Pressure ulcer infection delays wound healing and increases risks for sepsis, cellulitis, osteomyelitis, and death.5,6 Clinical evidence of soft tissue involvement, such as erythema, warmth, tenderness, foul odor, or purulent discharge, and systemic inflammatory response (fever, tachycardia, or leukocytosis) are suggestive of a wound infection.3,5 However, these clinical signs may be absent and thus make the distinction between chronic wound and infected pressure ulcer difficult.7 Delayed healing with friable granulation tissue and increased pain in a treated wound may be the only signs of a pressure ulcer infection.3,5,7

Routine laboratory tests (i.e. white blood cell count, C-reactive protein, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate) are neither sensitive nor specific in diagnosing wound infection. Moreover, because pressure ulcers are typically colonized with ≥105 organisms/mL of normal skin flora and bacteria from adjacent gastrointestinal or urogenital environments, swab cultures identify colonizing organisms and are not recommended as a diagnostic test for pressure ulcer microbiologic evaluation.5,6 If microbiological data are needed to guide antibiotic use, cultures of blood, bone, or deep tissue biopsied from a surgically debrided wound should be used.5 Importantly, a higher index of suspicion should be maintained for infection of Stage III or IV pressure ulcers because they are more commonly infected than Stage I or II ulcers.3

Prevention. The prevention of wound progression is essential in treating acute, chronic, or infected pressure ulcers. Although management guidelines are limited by few high-quality, randomized controlled trials, NPUAP recommends a number of prevention strategies targeting risk factors that contribute to pressure ulcer development.2,3,8

For all bed-bound and chair-bound persons with impaired ability to self-reposition, risk assessment for pressure ulcer should be done on admission and repeated every 24 hours. The presence of such risk factors as immobility, shear, friction, moisture, incontinence, and malnutrition should be used to guide preventive treatments. Pressure relief on an ulcer can be achieved by repositioning the immobile patient at one- to two-hour intervals. Pressure-redistributing support surfaces (static, overlays, or dynamic) reduce tissue pressure and decrease overall incidence of pressure ulcers. Due to a lack of relative efficacy data, the selection of a support surface should be determined by the patient’s individual needs in order to reduce pressure and shear.3 For instance, dynamic support is an appropriate surface for an immobile patient with multiple or nonhealing ulcers. Shearing force and friction can be reduced by limiting head-of-bed elevation to <30° and using such transfer aids as bed linens while repositioning patients. The use of pillows, foam wedges, or other devices should be used to eliminate direct contact of bony prominences or reduce pressure on heels.8

Skin care should be optimized to limit excessive dryness or moisture. This includes using moisturizers for dry skin, particularly for the sacrum, and implementing bowel and bladder programs and absorbent underpads in patients with bowel or bladder incontinence.2 Given that patients with pressure ulcers are in a catabolic state, those who are nutritionally compromised may benefit from nutritional supplementation.3 Lastly, appropriate use of local and systemic pain regimen for painful pressure ulcers can improve patient cooperation in repositioning, dressing change, and quality of life.

Debridement. Wound debridement removes necrotic tissue often present in infected or chronic pressure ulcers, reduces risk for further infection, and promotes granulation tissue formation and wound healing. Debridement, however, is not indicated for ulcers of an ischemic limb or dry eschar of the heel, due to propensity for complications.3,4 The five common debridement methods are sharp, mechanical, autolytic, enzymatic, and biosurgical. The debridement method of choice is determined by clinician preference and availability.4

Sharp debridement results in rapid removal of large amounts of nonviable necrotic tissues and eschar using sharp instruments and, therefore, is indicated if wound infection or sepsis is present. Mechanical debridement by wet-to-dry dressing or whirlpool nonselectively removes granulation tissue and, thus, should be used cautiously. Autolytic debridement uses occlusive dressings (i.e. hydrocolloid or hydrogel) to maintain a moist wound environment in order to optimize the body’s inherent ability to selectively self-digest necrotic tissues. Enzymatic debridement with concentrated topical proteolytic enzymes (i.e. collagenase) digests necrotic tissues and achieves faster debridement than autolysis while being less invasive than surgical intervention. Biosurgery utilizes maggots (i.e. Lucilia sericata) that produce enzymes to effectively debride necrotic tissues.

Wound care and dressing. Pressure ulcers should be cleansed with each dressing change using such physiologic solutions as normal saline. Cleansing with antimicrobial solutions for ulcers with large necrotic debris or infection needs to be thoughtfully administered due to the potential impairment on wound healing.4 Wound dressing should maintain a moist wound environment to allow epithelialization and limit excessive exudates in order to prevent maceration. Although there are many categories of moisture retentive dressings, their comparative effectiveness remain unclear.4 Table 2 summarizes characteristics of common wound dressings and their applications.

Antibiotic use. Topical antibiotics are appropriate for Stage III or IV ulcers with signs of local infection, including periwound erythema and friable granulation tissue.4 The Agency for Health Care Policy and Research recommends a two-week trial of a topical antibiotic, such as silver sulfadiazine, for pressure ulcers that fail to heal after two to four weeks of optimal care.6 Systemic antibiotics should be used for patients who demonstrate evidence of systemic infection including sepsis, osteomyelitis, or cellulitis with associated fever and leukocytosis. The choice of systemic antibiotics should be based on cultures from blood, bone, or deep tissue biopsied from a surgically debrided wound.4,6

Back to the Case

The patient was hospitalized for altered mental status. She was at high risk for the progression of her sacral ulcer and the development of new pressure ulcers due to immobility, incontinence, malnutrition, and impaired mental status. The sacral wound was a chronic, Stage III pressure ulcer without evidence of local tissue infection. However, the presence of leukocytosis and fever were suggestive of an underlying infection. Her urine analysis was consistent with a urinary tract infection.

Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole was administered with subsequent resolution of leukocytosis, fever, and delirium. The sacral ulcer was cleansed with normal saline and covered with hydrocolloid dressing every 72 hours in order to maintain a moist wound environment and facilitate autolysis. Preventive interventions guided by her risk factors for pressure ulcer were implemented. Interventions included:

- Daily skin and wound assessment;

- Pressure relief with repositioning every two hours;

- Use of a dynamic support surface;

- Head-of-bed elevation of no more than <30° to reduce shear and friction;

- Use of transfer aids;

- Use of devices to eliminate direct contact of bony prominences;

- Optimizing skin care with moisturizers for dry skin and frequent changing of absorbent under pads for incontinence; and

- Consulting nutrition service to optimize nutritional intake.

Bottom Line

Assessments of pressure ulcer stage, wound infection, and risk factors guide targeted therapeutic interventions that facilitate wound healing and prevent new pressure ulcer formation.

Dr. Prager is a fellow in the Brookdale Department of Geriatrics and Palliative Medicine at Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York City. Dr. Ko is a hospitalist and an assistant professor in the Brookdale Department of Geriatrics and Palliative Medicine at Mount Sinai.

References

- Pressure ulcers in America: prevalence, incidence, and implications for the future. An executive summary of the National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel monograph. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2001;14(4):208-215.

- Reddy M, Gill SS, Rochon PA. Preventing pressure ulcers: a systematic review. JAMA. 2006;296(8):974-984.

- European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel and National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel. Treatment of Pressure Ulcers: Quick Reference Guide. Washington, D.C.: National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel; 2009.

- Bates-Jensen BM. Chapter 58. Pressure Ulcers. In: Halter JB, Ouslander JG, Tinetti ME, Studenski S, High KP, Asthana S, eds. Hazzard’s Geriatric Medicine and Gerontology. 6th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2009.

- Livesley NJ, Chow AW. Infected pressure ulcers in elderly individuals. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;35(11):1390-1396.

- Agency for Health Care Policy and Research (AHCPR). Treatment of Pressure Ulcers. Clinical Practice Guideline Number 15. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 1994.

- Reddy M, Gill SS, Wu W, Kalkar SR, Rochon PA. Does this patient have an infection of a chronic wound? JAMA. 2012;307(6):605-611.

- National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel. Pressure Ulcer Prevention Points. National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel website. Available at: http://www.npuap.org/resources/educational-and-clinical-resources/pressure-ulcer-prevention-points/. Accessed Aug. 1, 2012.

- Reuben DB, Herr KA, Pacala JT, et al. Skin Ulcers. In: Geriatrics At Your Fingertips. 12th ed. New York: The American Geriatrics Society; 2010.

The Case

An 85-year-old woman with stroke, functional quadriplegia, and diabetes mellitus presents with altered mental status. She is febrile (38.5°C) with leukocytosis (14,400 cells/mm3) and has a 5 cm x 4 cm x 2 cm Stage III malodorous sacral ulcer without surrounding erythema, tunneling, or pain. The ulcer base is partially covered by green slough. How should this pressure ulcer be evaluated and treated?

Overview

Pressure ulcers in vulnerable populations, such as the elderly and those with limited mobility, are exceedingly common. In the acute-care setting, the incidence of pressure ulcers ranges from 0.4% to 38%, with 2.5 million cases treated annually at an estimated cost of $11 billion per year.1,2 Moreover, as of Oct. 1, 2008, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) guideline states that hospitals will no longer receive additional payment when a hospitalized patient develops Stage III or IV pressure ulcers that are not present on admission.

A pressure ulcer is a localized injury to skin and underlying soft tissue over a bony prominence due to sustained external pressure.3 Prolonged pressure on these weight-bearing areas leads to reduced blood flow, ischemia, cell death, and necrosis of local tissues.4 Risk factors for developing pressure ulcers include increased external pressure, shear, friction, moisture, poor perfusion, immobility, incontinence, malnutrition, and impaired mental status.4 Inadequately treated pressure ulcers can lead to pain, tunneling, fistula formation, disfigurement, infection, prolonged hospitalization, lower quality of life, and increased mortality.4

Because of the significant morbidities and high costs associated with the care of pressure ulcers in acute care, hospitalists must be familiar with the assessment and treatment of pressure ulcers in vulnerable patients.

Review of the Data

The management of pressure ulcers in the hospitalized patient starts with a comprehensive assessment of the patient’s medical comorbidities, risk factors, and wound-staging. Considerations must be given to differentiate an infected pressure ulcer from a noninfected ulcer. These evaluations then guide the appropriate treatments of pressure ulcers, including the prevention of progression or formation of new ulcers, debridement, application of wound dressing, and antibiotic use.

Assessing pressure ulcer stage. The National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (NPUAP) Classification System is the most commonly used staging tool. It describes four stages of pressure ulcers (see Table 1).3 A Stage 1 pressure ulcer is characterized by intact skin with nonblanchable erythema and may be discolored, painful, soft, firm, and warmer or cooler compared to adjacent area. A Stage II pressure ulcer presents with partial thickness skin loss with a shallow red-pink wound bed without slough, or as an intact or ruptured serum-filled blister. Stage II pressure ulcers do not include skin tears, tape burns, macerations, or excoriations. A Stage III pressure ulcer has full thickness skin loss with or without visible subcutaneous fat. Bone, tendon, or muscle are not exposed or directly palpable. Slough may be present but it does not obscure the depth of ulcer. Deep ulcers can develop in anatomical regions with high adiposity, such as the pelvic girdle. A Stage IV pressure ulcer has full thickness tissue loss with exposed and palpable bone, tendon, or muscle. Slough, eschar, undermining, and tunneling may be present. The depth of a Stage IV ulcer varies depending on anatomical location and adiposity. Stage IV ulcers also create a nidus for osteomyelitis.

NPUAP describes two additional categories of pressure ulcers: unstageable and deep tissue injury.3 An unstageable ulcer has full thickness skin or tissue loss of unknown depth because the wound base is completely obscured by slough or eschar. The ulcer can only be accurately categorized as Stage III or IV after sufficient slough or eschar is removed to identify wound depth. Lastly, suspected deep tissue injury describes a localized area of discolored intact skin (purple or maroon) or blood-filled blister due to damage of underlying tissue from pressure or shear.

Diagnosing infected pressure ulcers. Pressure ulcer infection delays wound healing and increases risks for sepsis, cellulitis, osteomyelitis, and death.5,6 Clinical evidence of soft tissue involvement, such as erythema, warmth, tenderness, foul odor, or purulent discharge, and systemic inflammatory response (fever, tachycardia, or leukocytosis) are suggestive of a wound infection.3,5 However, these clinical signs may be absent and thus make the distinction between chronic wound and infected pressure ulcer difficult.7 Delayed healing with friable granulation tissue and increased pain in a treated wound may be the only signs of a pressure ulcer infection.3,5,7

Routine laboratory tests (i.e. white blood cell count, C-reactive protein, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate) are neither sensitive nor specific in diagnosing wound infection. Moreover, because pressure ulcers are typically colonized with ≥105 organisms/mL of normal skin flora and bacteria from adjacent gastrointestinal or urogenital environments, swab cultures identify colonizing organisms and are not recommended as a diagnostic test for pressure ulcer microbiologic evaluation.5,6 If microbiological data are needed to guide antibiotic use, cultures of blood, bone, or deep tissue biopsied from a surgically debrided wound should be used.5 Importantly, a higher index of suspicion should be maintained for infection of Stage III or IV pressure ulcers because they are more commonly infected than Stage I or II ulcers.3

Prevention. The prevention of wound progression is essential in treating acute, chronic, or infected pressure ulcers. Although management guidelines are limited by few high-quality, randomized controlled trials, NPUAP recommends a number of prevention strategies targeting risk factors that contribute to pressure ulcer development.2,3,8

For all bed-bound and chair-bound persons with impaired ability to self-reposition, risk assessment for pressure ulcer should be done on admission and repeated every 24 hours. The presence of such risk factors as immobility, shear, friction, moisture, incontinence, and malnutrition should be used to guide preventive treatments. Pressure relief on an ulcer can be achieved by repositioning the immobile patient at one- to two-hour intervals. Pressure-redistributing support surfaces (static, overlays, or dynamic) reduce tissue pressure and decrease overall incidence of pressure ulcers. Due to a lack of relative efficacy data, the selection of a support surface should be determined by the patient’s individual needs in order to reduce pressure and shear.3 For instance, dynamic support is an appropriate surface for an immobile patient with multiple or nonhealing ulcers. Shearing force and friction can be reduced by limiting head-of-bed elevation to <30° and using such transfer aids as bed linens while repositioning patients. The use of pillows, foam wedges, or other devices should be used to eliminate direct contact of bony prominences or reduce pressure on heels.8

Skin care should be optimized to limit excessive dryness or moisture. This includes using moisturizers for dry skin, particularly for the sacrum, and implementing bowel and bladder programs and absorbent underpads in patients with bowel or bladder incontinence.2 Given that patients with pressure ulcers are in a catabolic state, those who are nutritionally compromised may benefit from nutritional supplementation.3 Lastly, appropriate use of local and systemic pain regimen for painful pressure ulcers can improve patient cooperation in repositioning, dressing change, and quality of life.

Debridement. Wound debridement removes necrotic tissue often present in infected or chronic pressure ulcers, reduces risk for further infection, and promotes granulation tissue formation and wound healing. Debridement, however, is not indicated for ulcers of an ischemic limb or dry eschar of the heel, due to propensity for complications.3,4 The five common debridement methods are sharp, mechanical, autolytic, enzymatic, and biosurgical. The debridement method of choice is determined by clinician preference and availability.4

Sharp debridement results in rapid removal of large amounts of nonviable necrotic tissues and eschar using sharp instruments and, therefore, is indicated if wound infection or sepsis is present. Mechanical debridement by wet-to-dry dressing or whirlpool nonselectively removes granulation tissue and, thus, should be used cautiously. Autolytic debridement uses occlusive dressings (i.e. hydrocolloid or hydrogel) to maintain a moist wound environment in order to optimize the body’s inherent ability to selectively self-digest necrotic tissues. Enzymatic debridement with concentrated topical proteolytic enzymes (i.e. collagenase) digests necrotic tissues and achieves faster debridement than autolysis while being less invasive than surgical intervention. Biosurgery utilizes maggots (i.e. Lucilia sericata) that produce enzymes to effectively debride necrotic tissues.

Wound care and dressing. Pressure ulcers should be cleansed with each dressing change using such physiologic solutions as normal saline. Cleansing with antimicrobial solutions for ulcers with large necrotic debris or infection needs to be thoughtfully administered due to the potential impairment on wound healing.4 Wound dressing should maintain a moist wound environment to allow epithelialization and limit excessive exudates in order to prevent maceration. Although there are many categories of moisture retentive dressings, their comparative effectiveness remain unclear.4 Table 2 summarizes characteristics of common wound dressings and their applications.

Antibiotic use. Topical antibiotics are appropriate for Stage III or IV ulcers with signs of local infection, including periwound erythema and friable granulation tissue.4 The Agency for Health Care Policy and Research recommends a two-week trial of a topical antibiotic, such as silver sulfadiazine, for pressure ulcers that fail to heal after two to four weeks of optimal care.6 Systemic antibiotics should be used for patients who demonstrate evidence of systemic infection including sepsis, osteomyelitis, or cellulitis with associated fever and leukocytosis. The choice of systemic antibiotics should be based on cultures from blood, bone, or deep tissue biopsied from a surgically debrided wound.4,6

Back to the Case

The patient was hospitalized for altered mental status. She was at high risk for the progression of her sacral ulcer and the development of new pressure ulcers due to immobility, incontinence, malnutrition, and impaired mental status. The sacral wound was a chronic, Stage III pressure ulcer without evidence of local tissue infection. However, the presence of leukocytosis and fever were suggestive of an underlying infection. Her urine analysis was consistent with a urinary tract infection.

Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole was administered with subsequent resolution of leukocytosis, fever, and delirium. The sacral ulcer was cleansed with normal saline and covered with hydrocolloid dressing every 72 hours in order to maintain a moist wound environment and facilitate autolysis. Preventive interventions guided by her risk factors for pressure ulcer were implemented. Interventions included:

- Daily skin and wound assessment;

- Pressure relief with repositioning every two hours;

- Use of a dynamic support surface;

- Head-of-bed elevation of no more than <30° to reduce shear and friction;

- Use of transfer aids;

- Use of devices to eliminate direct contact of bony prominences;

- Optimizing skin care with moisturizers for dry skin and frequent changing of absorbent under pads for incontinence; and

- Consulting nutrition service to optimize nutritional intake.

Bottom Line

Assessments of pressure ulcer stage, wound infection, and risk factors guide targeted therapeutic interventions that facilitate wound healing and prevent new pressure ulcer formation.

Dr. Prager is a fellow in the Brookdale Department of Geriatrics and Palliative Medicine at Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York City. Dr. Ko is a hospitalist and an assistant professor in the Brookdale Department of Geriatrics and Palliative Medicine at Mount Sinai.

References

- Pressure ulcers in America: prevalence, incidence, and implications for the future. An executive summary of the National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel monograph. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2001;14(4):208-215.

- Reddy M, Gill SS, Rochon PA. Preventing pressure ulcers: a systematic review. JAMA. 2006;296(8):974-984.

- European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel and National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel. Treatment of Pressure Ulcers: Quick Reference Guide. Washington, D.C.: National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel; 2009.

- Bates-Jensen BM. Chapter 58. Pressure Ulcers. In: Halter JB, Ouslander JG, Tinetti ME, Studenski S, High KP, Asthana S, eds. Hazzard’s Geriatric Medicine and Gerontology. 6th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2009.

- Livesley NJ, Chow AW. Infected pressure ulcers in elderly individuals. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;35(11):1390-1396.

- Agency for Health Care Policy and Research (AHCPR). Treatment of Pressure Ulcers. Clinical Practice Guideline Number 15. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 1994.

- Reddy M, Gill SS, Wu W, Kalkar SR, Rochon PA. Does this patient have an infection of a chronic wound? JAMA. 2012;307(6):605-611.

- National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel. Pressure Ulcer Prevention Points. National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel website. Available at: http://www.npuap.org/resources/educational-and-clinical-resources/pressure-ulcer-prevention-points/. Accessed Aug. 1, 2012.

- Reuben DB, Herr KA, Pacala JT, et al. Skin Ulcers. In: Geriatrics At Your Fingertips. 12th ed. New York: The American Geriatrics Society; 2010.