User login

researchers say.

“It’s a safe and very useful tool,” Marco Barchiesi, MD, an internal medicine resident at Luigi Sacco Hospital in Milan, said in an interview. “We had a great reduction in chest x-rays because of the use of ultrasound.”

The finding addresses concerns that ultrasound used in primary care could consume more health care resources or put patients at risk.

Dr. Barchiesi and colleagues published their findings July 20 in the European Journal of Internal Medicine.

Point-of-care ultrasound has become increasingly common as miniaturization of devices has made them more portable. The approach has caught on particularly in emergency departments where quick decisions are of the essence.

Its use in internal medicine has been more controversial, with concerns raised that improperly trained practitioners may miss diagnoses or refer patients for unnecessary tests as a result of uncertainty about their findings.

To measure the effect of point-of-care ultrasound in an internal medicine hospital ward, Dr. Barchiesi and colleagues alternated months when point-of-care ultrasound was allowed with months when it was not allowed, for a total of 4 months each, on an internal medicine unit. They allowed the ultrasound to be used for invasive procedures and excluded patients whose critical condition made point-of-care ultrasound crucial.

The researchers analyzed data on 263 patients in the “on” months when point-of-care ultrasound was used, and 255 in the “off” months when it wasn’t used. The two groups were well balanced in age, sex, comorbidity, and clinical impairment.

During the on months, the internists ordered 113 diagnostic tests (0.43 per patient). During the off months they ordered 329 tests (1.29 per patient).

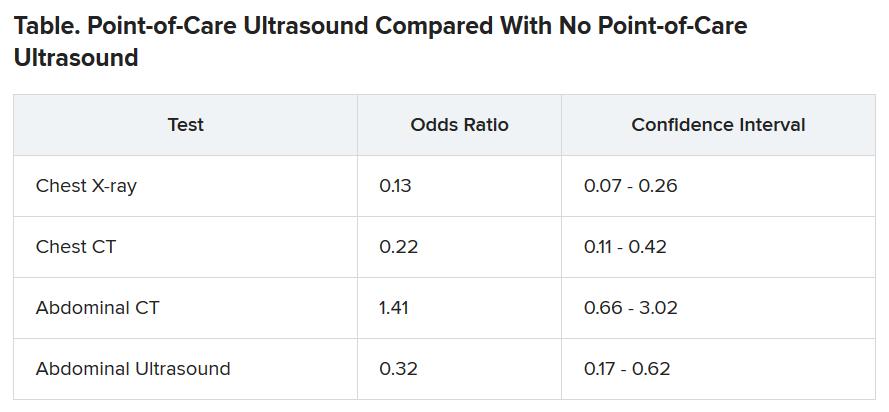

The odds of being referred for a chest x-ray were 87% less in the “on” months, compared with the off months, a statistically significant finding (P < .001). The risk for a chest CT scan and abdominal ultrasound were also reduced during the on months, but the risk for an abdominal CT was increased.

Nineteen patients died during the o” months and 10 during the off months, a difference that was not statistically significant (P = .15). The median length of stay in the hospital was almost the same for the two groups: 9 days for the on months and 9 days for the off months. The difference was also not statistically significant (P = .094).

Point-of-care ultrasound is particularly accurate in identifying cardiac abnormalities and pleural fluid and pneumonia, and it can be used effectively for monitoring heart conditions, the researchers wrote. This could explain the reduction in chest x-rays and CT scans.

On the other hand, ultrasound cannot address such questions as staging in an abdominal malignancy, and unexpected findings are more common with abdominal than chest ultrasound. This could explain why the point-of-care ultrasound did not reduce the use of abdominal CT, the researchers speculated.

They acknowledged that the patients in their sample had an average age of 81 years, raising questions about how well their data could be applied to a younger population. And they noted that they used point-of-care ultrasound frequently, so they were particularly adept with it. “We use it almost every day in our clinical practice,” said Dr. Barchiesi.

Those factors may have played a key role in the success of point-of-care ultrasound in this study, said Michael Wagner, MD, an assistant professor of medicine at the University of South Carolina, Greenville, who has helped colleagues incorporate ultrasound into their practices.

Elderly patients often present with multiple comorbidities and atypical signs and symptoms, he said. “Sometimes they can be very confusing as to the underlying clinical picture. Ultrasound is being used frequently to better assess these complicated patients.”

Dr. Wagner said extensive training is required to use point-of-care ultrasound accurately.

Dr. Barchiesi also acknowledged that the devices used in this study were large portable machines, not the simpler and less expensive hand-held versions that are also available for similar purposes.

Point-of-care ultrasound is a promising innovation, said Thomas Melgar, MD, a professor of medicine at Western Michigan University, Kalamazoo. “The advantage is that the exam is being done by someone who knows the patient and specifically what they’re looking for. It’s done at the bedside so you don’t have to move the patient.”

The study could help address opposition to internal medicine residents being trained in the technique, he said, adding that “I think it’s very exciting.”

The study was partially supported by Philips, which provided the ultrasound devices. Dr. Barchiesi, Dr. Melgar, and Dr. Wagner disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

researchers say.

“It’s a safe and very useful tool,” Marco Barchiesi, MD, an internal medicine resident at Luigi Sacco Hospital in Milan, said in an interview. “We had a great reduction in chest x-rays because of the use of ultrasound.”

The finding addresses concerns that ultrasound used in primary care could consume more health care resources or put patients at risk.

Dr. Barchiesi and colleagues published their findings July 20 in the European Journal of Internal Medicine.

Point-of-care ultrasound has become increasingly common as miniaturization of devices has made them more portable. The approach has caught on particularly in emergency departments where quick decisions are of the essence.

Its use in internal medicine has been more controversial, with concerns raised that improperly trained practitioners may miss diagnoses or refer patients for unnecessary tests as a result of uncertainty about their findings.

To measure the effect of point-of-care ultrasound in an internal medicine hospital ward, Dr. Barchiesi and colleagues alternated months when point-of-care ultrasound was allowed with months when it was not allowed, for a total of 4 months each, on an internal medicine unit. They allowed the ultrasound to be used for invasive procedures and excluded patients whose critical condition made point-of-care ultrasound crucial.

The researchers analyzed data on 263 patients in the “on” months when point-of-care ultrasound was used, and 255 in the “off” months when it wasn’t used. The two groups were well balanced in age, sex, comorbidity, and clinical impairment.

During the on months, the internists ordered 113 diagnostic tests (0.43 per patient). During the off months they ordered 329 tests (1.29 per patient).

The odds of being referred for a chest x-ray were 87% less in the “on” months, compared with the off months, a statistically significant finding (P < .001). The risk for a chest CT scan and abdominal ultrasound were also reduced during the on months, but the risk for an abdominal CT was increased.

Nineteen patients died during the o” months and 10 during the off months, a difference that was not statistically significant (P = .15). The median length of stay in the hospital was almost the same for the two groups: 9 days for the on months and 9 days for the off months. The difference was also not statistically significant (P = .094).

Point-of-care ultrasound is particularly accurate in identifying cardiac abnormalities and pleural fluid and pneumonia, and it can be used effectively for monitoring heart conditions, the researchers wrote. This could explain the reduction in chest x-rays and CT scans.

On the other hand, ultrasound cannot address such questions as staging in an abdominal malignancy, and unexpected findings are more common with abdominal than chest ultrasound. This could explain why the point-of-care ultrasound did not reduce the use of abdominal CT, the researchers speculated.

They acknowledged that the patients in their sample had an average age of 81 years, raising questions about how well their data could be applied to a younger population. And they noted that they used point-of-care ultrasound frequently, so they were particularly adept with it. “We use it almost every day in our clinical practice,” said Dr. Barchiesi.

Those factors may have played a key role in the success of point-of-care ultrasound in this study, said Michael Wagner, MD, an assistant professor of medicine at the University of South Carolina, Greenville, who has helped colleagues incorporate ultrasound into their practices.

Elderly patients often present with multiple comorbidities and atypical signs and symptoms, he said. “Sometimes they can be very confusing as to the underlying clinical picture. Ultrasound is being used frequently to better assess these complicated patients.”

Dr. Wagner said extensive training is required to use point-of-care ultrasound accurately.

Dr. Barchiesi also acknowledged that the devices used in this study were large portable machines, not the simpler and less expensive hand-held versions that are also available for similar purposes.

Point-of-care ultrasound is a promising innovation, said Thomas Melgar, MD, a professor of medicine at Western Michigan University, Kalamazoo. “The advantage is that the exam is being done by someone who knows the patient and specifically what they’re looking for. It’s done at the bedside so you don’t have to move the patient.”

The study could help address opposition to internal medicine residents being trained in the technique, he said, adding that “I think it’s very exciting.”

The study was partially supported by Philips, which provided the ultrasound devices. Dr. Barchiesi, Dr. Melgar, and Dr. Wagner disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

researchers say.

“It’s a safe and very useful tool,” Marco Barchiesi, MD, an internal medicine resident at Luigi Sacco Hospital in Milan, said in an interview. “We had a great reduction in chest x-rays because of the use of ultrasound.”

The finding addresses concerns that ultrasound used in primary care could consume more health care resources or put patients at risk.

Dr. Barchiesi and colleagues published their findings July 20 in the European Journal of Internal Medicine.

Point-of-care ultrasound has become increasingly common as miniaturization of devices has made them more portable. The approach has caught on particularly in emergency departments where quick decisions are of the essence.

Its use in internal medicine has been more controversial, with concerns raised that improperly trained practitioners may miss diagnoses or refer patients for unnecessary tests as a result of uncertainty about their findings.

To measure the effect of point-of-care ultrasound in an internal medicine hospital ward, Dr. Barchiesi and colleagues alternated months when point-of-care ultrasound was allowed with months when it was not allowed, for a total of 4 months each, on an internal medicine unit. They allowed the ultrasound to be used for invasive procedures and excluded patients whose critical condition made point-of-care ultrasound crucial.

The researchers analyzed data on 263 patients in the “on” months when point-of-care ultrasound was used, and 255 in the “off” months when it wasn’t used. The two groups were well balanced in age, sex, comorbidity, and clinical impairment.

During the on months, the internists ordered 113 diagnostic tests (0.43 per patient). During the off months they ordered 329 tests (1.29 per patient).

The odds of being referred for a chest x-ray were 87% less in the “on” months, compared with the off months, a statistically significant finding (P < .001). The risk for a chest CT scan and abdominal ultrasound were also reduced during the on months, but the risk for an abdominal CT was increased.

Nineteen patients died during the o” months and 10 during the off months, a difference that was not statistically significant (P = .15). The median length of stay in the hospital was almost the same for the two groups: 9 days for the on months and 9 days for the off months. The difference was also not statistically significant (P = .094).

Point-of-care ultrasound is particularly accurate in identifying cardiac abnormalities and pleural fluid and pneumonia, and it can be used effectively for monitoring heart conditions, the researchers wrote. This could explain the reduction in chest x-rays and CT scans.

On the other hand, ultrasound cannot address such questions as staging in an abdominal malignancy, and unexpected findings are more common with abdominal than chest ultrasound. This could explain why the point-of-care ultrasound did not reduce the use of abdominal CT, the researchers speculated.

They acknowledged that the patients in their sample had an average age of 81 years, raising questions about how well their data could be applied to a younger population. And they noted that they used point-of-care ultrasound frequently, so they were particularly adept with it. “We use it almost every day in our clinical practice,” said Dr. Barchiesi.

Those factors may have played a key role in the success of point-of-care ultrasound in this study, said Michael Wagner, MD, an assistant professor of medicine at the University of South Carolina, Greenville, who has helped colleagues incorporate ultrasound into their practices.

Elderly patients often present with multiple comorbidities and atypical signs and symptoms, he said. “Sometimes they can be very confusing as to the underlying clinical picture. Ultrasound is being used frequently to better assess these complicated patients.”

Dr. Wagner said extensive training is required to use point-of-care ultrasound accurately.

Dr. Barchiesi also acknowledged that the devices used in this study were large portable machines, not the simpler and less expensive hand-held versions that are also available for similar purposes.

Point-of-care ultrasound is a promising innovation, said Thomas Melgar, MD, a professor of medicine at Western Michigan University, Kalamazoo. “The advantage is that the exam is being done by someone who knows the patient and specifically what they’re looking for. It’s done at the bedside so you don’t have to move the patient.”

The study could help address opposition to internal medicine residents being trained in the technique, he said, adding that “I think it’s very exciting.”

The study was partially supported by Philips, which provided the ultrasound devices. Dr. Barchiesi, Dr. Melgar, and Dr. Wagner disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.