Pudendal neuralgia is an important but often unrecognized and undiagnosed cause of pelvic floor pain.

Its incidence is unknown, and there is relatively little data and scientific evidence in the literature on its diagnosis and treatment. However, I believe that a significant number of women who have burning pain in the vulva, clitoris, vagina, perineum, or rectum – including women who are diagnosed with interstitial cystitis, pelvic floor muscle spasms, vulvodynia, or other conditions – may in fact have pudendal neuralgia.

Indeed, pudendal neuralgia is largely a diagnosis of exclusion, and such conditions often must be ruled out. But the neuropathic condition should be suspected in women who have burning pain in any area along the distribution of the pudendal nerve. Awareness of the nerve’s anatomy and distribution, and of the hallmark characteristics and symptoms of pudendal neuralgia, is important, because earlier identification and treatment appears to provide better outcomes.

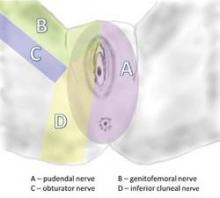

Pudendal neuralgia is but one type of pelvic neuralgia; neuropathic pain in the pelvic region also can stem from injury to the obturator, ilioinguinal, iliohypogastric, or genitofemoral nerves, for instance. Most of the patients in our practice, however, have pudendal neuralgia caused by mechanical compression – what is referred to as pudendal nerve entrapment – rather than disease of the nerve.

The condition is sometimes referred to as cyclist syndrome because, historically, the first documented group of patients with symptoms of pudendal neuralgia was competitive cyclists. There is a misconception, however, that the condition only occurs in cyclists. In fact, pudendal neuralgia and pudendal nerve entrapment specifically may be caused by various forms of pelvic trauma, from vaginal delivery (with or without instrumentation) and heavy lifting or falls on the back or pelvis, to previous gynecologic surgery, such as hysterectomy, cystocele repair, and mesh procedures for prolapse and incontinence.

Pudendal neuralgia is multifactorial, involving not only compression of the nerve, for instance, but also muscle spasm and peripheral and central sensitization of pain. Treatment involves a progression of conservative therapies followed by decompression surgery when these conservative treatments fail. We have made several modifications to the transgluteal approach as it was originally described, and believe this approach affords the best outcomes.

Anatomy and Symptoms

The pudendal nerve originates in the S2-S4 sacral foramina, and divides into three branches – the inferior rectal nerve, the perineal nerve, and the dorsal clitoral nerve. The nerve thus innervates the clitoris, vulva, labia, vagina, perineum, and rectum. Pain can be present along the entire nerve, or localized to the sites of nerve innervation. Symptoms can be unilateral or bilateral, although with bilateral pain there usually is a more affected side.

In most cases, patients will describe neuropathic pain – a burning, tingling, or numbing pain – that is worse with sitting, and less severe or absent when standing or lying down.

Initially, pain may be present only with sitting, but with time pain becomes more constant and severely aggravated by sitting. Many of my patients cannot tolerate sitting at all. Interestingly, patients usually report less pain when sitting on a toilet seat, a phenomenon that we believe is associated with pressure being applied to the ischial tuberosities rather than to the pelvic floor muscles. Pain usually gets progressively worse through the day.

Patients often will report the sensation of having a foreign body, frequently described as a golf ball or tennis ball, in the vagina, perineum, or rectum.

Pain with urination and/or bowel movements, and problems with frequency and urgency, also are often reported, as is pain with intercourse. Dyspareunia may be associated with penetration, sexual arousal, or orgasm, or any combination. Some patients report feeling persistent sexual arousal.

Occasionally, patients report having pain in regions outside the areas of innervation for the pudendal nerve, such as the lower back or posterior thigh. The presence of sciatica, or pain that radiates down the leg, for instance, should not rule out consideration of pudendal neuralgia.

Just as worsening pain with sitting is a defining characteristic, almost all patients also have an acute onset of discomfort or pain; their pain can be traced to some type of traumatic event.

One of my recent patients, for instance, was in a gym class doing a lunge with barbells on her shoulders when her legs gave out and she experienced the start of continuous pain in her vulvar area. Many of our patients trace the onset of their symptoms to immediately after gynecologic surgery, particularly vaginal procedures for prolapse or incontinence. (The pain in these cases is frequently attributed to normal postoperative pain.) Some patients report a more gradual onset of symptoms after surgery.