User login

Case

An 83-year-old male with hypertension, coronary artery disease, and obstructive sleep apnea presents with progressive shortness of breath, a productive cough, wheezing, and tachypnea. His blood pressure is 158/70 mm/Hg; temperature is 101.8; respirations are 26 breaths per minute; and oxygen saturation is 87% on room air. He has coarse breath sounds bilaterally, and decreased breath sounds over the right lower lung fields. His chest X-ray reveals a right lower lobe infiltrate. He is admitted to the hospital with a diagnosis of community-acquired pneumonia (CAP), and medical therapy is started. How should his antibiotic treatment be managed?

Overview

Community-acquired pneumonia is the most common infection-related cause of death in the U.S., and the eighth-leading cause of mortality overall.1 According to a 2006 survey, CAP results in more than 1.2 million hospital admissions annually, with an average length of stay of 5.1 days.2 Though less than 20% of CAP patients require hospitalization, cases necessitating admission contribute to more than 90% of the overall cost of pneumonia care.3

During the past several years, the availability of new antibiotics and the evolution of microbial resistance patterns have changed CAP treatment strategies. Furthermore, the development of prognostic scoring systems and increasing pressure to streamline resource utilization while improving quality of care have led to new treatment considerations, such as managing low-risk cases as outpatients.

More recently, attention has been directed to the optimal duration of antibiotic treatment, with a focus on shortening the duration of therapy. Historically, CAP treatment duration has been variable and not evidence-based. Shortening the course of antibiotics might limit antibiotic resistance, decrease costs, and improve patient adherence and tolerability.4 However, before defining the appropriate antibiotic duration for a patient hospitalized with CAP, other factors must be considered, such as the choice of empiric antibiotics, the patient’s initial response to treatment, severity of the disease, and presence of co-morbidities.

Review of the Data

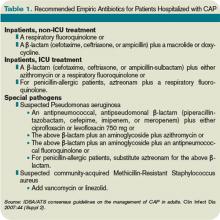

Antibiotic choice. The most widely referenced practice guidelines for the management of CAP patients were published in 2007 by representatives of the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the American Thoracic Society (ATS).5 Table 1 (above, right) summarizes the recommendations for empiric antibiotics for patients requiring inpatient treatment.

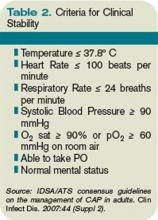

Time to clinical stability. A patient’s clinical response to empiric antibiotic therapy contributes heavily to the decision regarding treatment course and duration. The IDSA/ATS guidelines recommend patients be afebrile for 48 to 72 hours and have no more than one CAP-associated sign of clinical instability before discontinuation of therapy. Although studies have used different definitions of clinical stability, the consensus guidelines refer to six parameters, which are summarized in Table 2 (right).

With appropriate antibiotic therapy, most patients hospitalized with CAP achieve clinical stability in approximately three days.6,7 Providers should expect to see some improvement in vital signs within 48 to 72 hours of admission. Should a patient fail to demonstrate objective improvement during that time, providers should look for unusual pathogens, resistant organisms, nosocomial superinfections, or noninfectious conditions.5 Certain patients, such as those with multilobar pneumonia, associated pleural effusion, or higher pneumonia-severity index scores, also take longer to reach clinical stability.8

Switch to oral therapy. The ability to achieve clinical stability has important implications for hospital length of stay. Most patients hospitalized with CAP initially are treated with intravenous (IV) antibiotics and require transition to oral therapy in anticipation of discharge. Several studies have found there is no advantage to continuing IV medication once a patient is deemed clinically stable and is able to tolerate oral medication.9,10 There are no specific guidelines regarding choice of oral antibiotics, but it is common practice, supported by the IDSA/ATS recommendations, to use the same agent as the IV antibiotic or a medication in the same drug class. For patients started on β-lactam and macrolide combination therapy, it usually is appropriate to switch to a macrolide alone.5 In cases in which a pathogen has been identified, antibiotic selection should be based on the susceptibility profile.

Once patients are switched to oral antibiotics, it is not necessary for them to remain in the hospital for further observation, provided they have no other active medical problems or social needs. A retrospective analysis of 39,232 patients hospitalized with CAP compared those who were observed overnight after switching to oral antibiotics with those who were not and found no difference in 14-day readmission rate or 30-day mortality rate.11 These findings, in conjunction with the strategy of an early switch to oral therapy, suggest hospital length of stay may be safely reduced for many patients with uncomplicated CAP.

Duration of therapy. After a patient becomes clinically stable and a decision is made to switch to oral medication and a plan for hospital discharge, the question becomes how long to continue the course of antibiotics. Historically, clinical practice has extended treatment for up to two weeks, despite lack of evidence for this duration of therapy. The IDSA/ATS guidelines offer some general recommendations, noting patients should be treated for a minimum of five days, in addition to being afebrile for 48 to 72 hours and meet other criteria for clinical stability.5

Li and colleagues conducted a systematic review evaluating 15 randomized controlled trials comparing short-course (less than seven days) with extended (more than seven days) monotherapy for CAP in adults.4 Overall, the authors found no difference in the risk of treatment failure between short-course and extended-course antibiotic therapy, and they found no difference in bacteriologic eradication or mortality. It is important to note the studies included in this analysis enrolled patients with mild to moderate CAP, including those treated as outpatients, which limits the ability to extrapolate to exclusively inpatient populations and more severely ill patients.

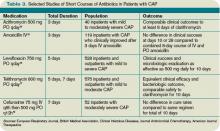

Another meta-analysis, published shortly thereafter, examined randomized controlled trials in outpatients and inpatients not requiring intensive care. It compared different durations of treatment with the same agent in the same dosage. The authors similarly found no difference in effectiveness or safety of short (less than seven days) versus longer (at least two additional days of therapy) courses.12 Table 3 (above) reviews selected trials of short courses of antibiotics, which have been studied in inpatient populations.

The trials summarized in these meta-analyses examined monotherapy with levofloxacin for five days; gemifloxacin for seven days, azithromycin for three to five days; ceftriaxone for five days; cefuroxime for seven days; amoxicillin for three days; or telithromycin for five to seven days. The variety of antibiotics in these studies contrasts the IDSA/ATS guidelines, which recommend only fluoroquinolones as monotherapy for inpatient CAP.

One important randomized, double-blind study of fluoroquinolones compared a five-day course of levofloxacin 750 mg daily, with a 10-day course of levofloxacin, 500 mg daily, in 528 patients with mild to severe CAP.13 The authors found no difference in clinical success or microbiologic eradication between the two groups, concluding high-dose levofloxacin for five days is an effective and well-tolerated alternative to a longer course of a lower dose, likely related to the drug’s concentration-dependent properties.

Azithromycin also offers potential for short courses of therapy, as pulmonary concentrations of azithromycin remain elevated for as many as five days following a single oral dose.14 Several small studies have demonstrated the safety, efficacy, and cost-effectiveness of three to five days of azithromycin, as summarized in a meta-analysis by Contopoulos-Ioannidis and colleagues.15 Most of these trials, however, were limited to outpatients or inpatients with mild disease or confirmed atypical pneumonia. One randomized trial of 40 inpatients with mild to moderately severe CAP found comparable clinical outcomes with a three-day course of oral azithromycin 500 mg daily versus clarithromycin for at least eight days.16 Larger studies in more severely ill patients must be completed before routinely recommending this approach in hospitalized patients. Furthermore, due to the rising prevalence of macrolide resistance, empiric therapy with a macrolide alone can only be used for the treatment of carefully selected hospitalized patients with nonsevere diseases and without risk factors for drug-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae.5

Telithromycin is a ketolide antibiotic, which has been studied in mild to moderate CAP, including multidrug-resistant strains of S. pneumoniae, in courses of five to seven days.17 However, severe adverse reactions, including hepatotoxicity, have been reported. At the time of the 2007 guidelines, the IDSA/ATS committee waited for additional safety data before making any recommendations on its use.

One additional study of note was a trial of amoxicillin in adult inpatients with mild to moderately severe CAP.18 One hundred twenty-one patients who clinically improved (based on a composite score of pulmonary symptoms and general improvement) following three days of IV amoxicillin were randomized to oral amoxicillin for an additional five days or given a placebo. At days 10 and 28, there was no difference in clinical success between the two groups. The authors concluded that a total of three days of treatment was not inferior to eight days in patients who substantially improved after the first 72 hours of empiric treatment. This trial was conducted in the Netherlands, where amoxicillin is the preferred empiric antibiotic for CAP and patterns of antimicrobial resistance differ greatly from those found in the U.S.

Other considerations. While some evidence supports shorter courses of antibiotics, many of the existing studies are limited by their inclusion of outpatients, adults with mild to moderate CAP, or small sample size. Hence, clinical judgment continues to play an important role in determining the appropriate duration of therapy. Factors such as pre-existing co-morbidities, severity of illness, and occurrence of complications should be considered. Data is limited on the appropriate duration of antibiotics in CAP patients requiring intensive care. It also is important to note the IDSA/ATS recommendations and most of the studies reviewed exclude patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and it is unknown whether these shorter courses of antibiotics are appropriate in the HIV population.

Lastly, the IDSA/ATS guidelines note longer durations of treatment may be required if the initial therapy was not active against the identified pathogen, or in cases complicated by extrapulmonary infections, such as endocarditis or meningitis.

Back to the Case

Our patient with moderately severe CAP was hospitalized based on his age and hypoxia. He was immediately treated with supplemental oxygen by nasal cannula, IV fluids, and a dose of IV levofloxacin 750 mg. Within 48 hours he met criteria for clinical stability, including defervescence, a decline in his respiratory rate to 19 breaths per minute, and improvement in oxygen saturation to 95% on room air. At this point, he was changed from IV to oral antibiotics. He continued on levofloxacin 750 mg daily and later that day was discharged home in good condition to complete a five-day course.

Bottom Line

For hospitalized adults with mild to moderately severe CAP, five to seven days of treatment, depending on the antibiotic selected, appears to be effective in most cases. Patients should be afebrile for 48 to 72 hours and demonstrate signs of clinical stability before therapy is discontinued. TH

Kelly Cunningham, MD, and Shelley Ellis, MD, MPH, are members of the Section of Hospital Medicine at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tenn. Sunil Kripalani, MD, MSc, serves as the section chief.

References

1. Kung HC, Hoyert DL, Xu J, Murphy SL. Deaths: final data for 2005. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2008;56.

2. DeFrances CJ, Lucas CA, Buie VC, Golosinskiy A. 2006 National Hospital Discharge Survey. Natl Health Stat Report. 2008;5.

3. Niederman MS. Recent advances in community-acquired pneumonia: inpatient and outpatient. Chest. 2007;131:1205-1215.

4. Li JZ, Winston LG, Moore DH, Bent S. Efficacy of short-course antibiotic regimens for community-acquired pneumonia: a meta-analysis. Am J Med. 2007;120:783-790.

5. Mandell LA, Wunderink RG, Anzueto A et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society consensus guidelines on the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(Suppl 2):S27-72.

6. Ramirez JA, Bordon J. Early switch from intravenous to oral antibiotics in hospitalized patients with bacteremic community-acquired Streptococcus pneumoniae pneumonia. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:848-850.

7. Halm EA, Fine MJ, Marrie TJ et al. Time to clinical stability in patients hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia: implications for practice guidelines. JAMA. 1998;279:1452-1457.

8. Menendez R, Torres A, Rodriguez de Castro F et al. Reaching stability in community-acquired pneumonia: the effects of the severity of disease, treatment, and the characteristics of patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:1783-1790.

9. Siegal RE, Halpern NA, Almenoff PL et al. A prospective randomised study of inpatient IV antibiotics for community-acquired pneumonia: the optimal duration of therapy. Chest. 1996;110:965-971.

10. Oosterheert JJ, Bonten MJ, Schneider MM et al. Effectiveness of early switch from intravenous to oral antibiotics in severe community acquired pneumonia: multicentre randomized trial. BMJ. 2006;333:1193-1197.

11. Nathan RV, Rhew DC, Murray C et al. In-hospital observation after antibiotic switch in pneumonia: a national evaluation. Am J Med. 2006;119:512-518.

12. Dimopoulos G, Matthaiou DK, Karageorgopoulos DE, et al. Short- versus long-course antibacterial therapy for community-acquired pneumonia: a meta-analysis. Drugs. 2008;68:1841-1854.

13. Dunbar LM, Wunderink RG, Habib MP et al. High-dose, short-course levofloxacin for community-acquired pneumonia: a new treatment paradigm. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:752-760.

14. Morris DL, De Souza A, Jones JA, Morgan WE. High and prolonged pulmonary tissue concentrations of azithromycin following a single oral dose. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1991;10:859-861.

15. Contopoulos-Ioannidis DG, Ioannidis JPA, Chew P, Lau J. Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials on the comparative efficacy and safety of azithromycin against other antibiotics for lower respiratory tract infections. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2001;48:691-703.

16. Rizzato G, Montemurro L, Fraioli P et al. Efficacy of a three-day course of azithromycin in moderately severe community-acquired pneumonia. Eur Respir J. 1995;8:398-402.

17. Tellier G, Niederman MS, Nusrat R et al. Clinical and bacteriological efficacy and safety of 5- and 7-day regimens of telithromycin once daily compared with a 10-day regimen of clarithromycin twice daily in patients with mild to moderate community-acquired pneumonia. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2004;54:515.

18. El Moussaoui R, de Borgie CA, van den Broek P et al. Effectiveness of discontinuing antibiotic treatment after three days versus eight days in mild to moderate-severe community acquired pneumonia: randomised, double blind study. BMJ. 2006;332:1355-1361.

19. Siegel RE, Alicea M, Lee A, Blaiklock R. Comparison of 7 versus 10 days of antibiotic therapy for hospitalized patients with uncomplicated community-acquired pneumonia: a prospective, randomized double-blind study. Am J Ther. 1999;6:217-222.

Case

An 83-year-old male with hypertension, coronary artery disease, and obstructive sleep apnea presents with progressive shortness of breath, a productive cough, wheezing, and tachypnea. His blood pressure is 158/70 mm/Hg; temperature is 101.8; respirations are 26 breaths per minute; and oxygen saturation is 87% on room air. He has coarse breath sounds bilaterally, and decreased breath sounds over the right lower lung fields. His chest X-ray reveals a right lower lobe infiltrate. He is admitted to the hospital with a diagnosis of community-acquired pneumonia (CAP), and medical therapy is started. How should his antibiotic treatment be managed?

Overview

Community-acquired pneumonia is the most common infection-related cause of death in the U.S., and the eighth-leading cause of mortality overall.1 According to a 2006 survey, CAP results in more than 1.2 million hospital admissions annually, with an average length of stay of 5.1 days.2 Though less than 20% of CAP patients require hospitalization, cases necessitating admission contribute to more than 90% of the overall cost of pneumonia care.3

During the past several years, the availability of new antibiotics and the evolution of microbial resistance patterns have changed CAP treatment strategies. Furthermore, the development of prognostic scoring systems and increasing pressure to streamline resource utilization while improving quality of care have led to new treatment considerations, such as managing low-risk cases as outpatients.

More recently, attention has been directed to the optimal duration of antibiotic treatment, with a focus on shortening the duration of therapy. Historically, CAP treatment duration has been variable and not evidence-based. Shortening the course of antibiotics might limit antibiotic resistance, decrease costs, and improve patient adherence and tolerability.4 However, before defining the appropriate antibiotic duration for a patient hospitalized with CAP, other factors must be considered, such as the choice of empiric antibiotics, the patient’s initial response to treatment, severity of the disease, and presence of co-morbidities.

Review of the Data

Antibiotic choice. The most widely referenced practice guidelines for the management of CAP patients were published in 2007 by representatives of the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the American Thoracic Society (ATS).5 Table 1 (above, right) summarizes the recommendations for empiric antibiotics for patients requiring inpatient treatment.

Time to clinical stability. A patient’s clinical response to empiric antibiotic therapy contributes heavily to the decision regarding treatment course and duration. The IDSA/ATS guidelines recommend patients be afebrile for 48 to 72 hours and have no more than one CAP-associated sign of clinical instability before discontinuation of therapy. Although studies have used different definitions of clinical stability, the consensus guidelines refer to six parameters, which are summarized in Table 2 (right).

With appropriate antibiotic therapy, most patients hospitalized with CAP achieve clinical stability in approximately three days.6,7 Providers should expect to see some improvement in vital signs within 48 to 72 hours of admission. Should a patient fail to demonstrate objective improvement during that time, providers should look for unusual pathogens, resistant organisms, nosocomial superinfections, or noninfectious conditions.5 Certain patients, such as those with multilobar pneumonia, associated pleural effusion, or higher pneumonia-severity index scores, also take longer to reach clinical stability.8

Switch to oral therapy. The ability to achieve clinical stability has important implications for hospital length of stay. Most patients hospitalized with CAP initially are treated with intravenous (IV) antibiotics and require transition to oral therapy in anticipation of discharge. Several studies have found there is no advantage to continuing IV medication once a patient is deemed clinically stable and is able to tolerate oral medication.9,10 There are no specific guidelines regarding choice of oral antibiotics, but it is common practice, supported by the IDSA/ATS recommendations, to use the same agent as the IV antibiotic or a medication in the same drug class. For patients started on β-lactam and macrolide combination therapy, it usually is appropriate to switch to a macrolide alone.5 In cases in which a pathogen has been identified, antibiotic selection should be based on the susceptibility profile.

Once patients are switched to oral antibiotics, it is not necessary for them to remain in the hospital for further observation, provided they have no other active medical problems or social needs. A retrospective analysis of 39,232 patients hospitalized with CAP compared those who were observed overnight after switching to oral antibiotics with those who were not and found no difference in 14-day readmission rate or 30-day mortality rate.11 These findings, in conjunction with the strategy of an early switch to oral therapy, suggest hospital length of stay may be safely reduced for many patients with uncomplicated CAP.

Duration of therapy. After a patient becomes clinically stable and a decision is made to switch to oral medication and a plan for hospital discharge, the question becomes how long to continue the course of antibiotics. Historically, clinical practice has extended treatment for up to two weeks, despite lack of evidence for this duration of therapy. The IDSA/ATS guidelines offer some general recommendations, noting patients should be treated for a minimum of five days, in addition to being afebrile for 48 to 72 hours and meet other criteria for clinical stability.5

Li and colleagues conducted a systematic review evaluating 15 randomized controlled trials comparing short-course (less than seven days) with extended (more than seven days) monotherapy for CAP in adults.4 Overall, the authors found no difference in the risk of treatment failure between short-course and extended-course antibiotic therapy, and they found no difference in bacteriologic eradication or mortality. It is important to note the studies included in this analysis enrolled patients with mild to moderate CAP, including those treated as outpatients, which limits the ability to extrapolate to exclusively inpatient populations and more severely ill patients.

Another meta-analysis, published shortly thereafter, examined randomized controlled trials in outpatients and inpatients not requiring intensive care. It compared different durations of treatment with the same agent in the same dosage. The authors similarly found no difference in effectiveness or safety of short (less than seven days) versus longer (at least two additional days of therapy) courses.12 Table 3 (above) reviews selected trials of short courses of antibiotics, which have been studied in inpatient populations.

The trials summarized in these meta-analyses examined monotherapy with levofloxacin for five days; gemifloxacin for seven days, azithromycin for three to five days; ceftriaxone for five days; cefuroxime for seven days; amoxicillin for three days; or telithromycin for five to seven days. The variety of antibiotics in these studies contrasts the IDSA/ATS guidelines, which recommend only fluoroquinolones as monotherapy for inpatient CAP.

One important randomized, double-blind study of fluoroquinolones compared a five-day course of levofloxacin 750 mg daily, with a 10-day course of levofloxacin, 500 mg daily, in 528 patients with mild to severe CAP.13 The authors found no difference in clinical success or microbiologic eradication between the two groups, concluding high-dose levofloxacin for five days is an effective and well-tolerated alternative to a longer course of a lower dose, likely related to the drug’s concentration-dependent properties.

Azithromycin also offers potential for short courses of therapy, as pulmonary concentrations of azithromycin remain elevated for as many as five days following a single oral dose.14 Several small studies have demonstrated the safety, efficacy, and cost-effectiveness of three to five days of azithromycin, as summarized in a meta-analysis by Contopoulos-Ioannidis and colleagues.15 Most of these trials, however, were limited to outpatients or inpatients with mild disease or confirmed atypical pneumonia. One randomized trial of 40 inpatients with mild to moderately severe CAP found comparable clinical outcomes with a three-day course of oral azithromycin 500 mg daily versus clarithromycin for at least eight days.16 Larger studies in more severely ill patients must be completed before routinely recommending this approach in hospitalized patients. Furthermore, due to the rising prevalence of macrolide resistance, empiric therapy with a macrolide alone can only be used for the treatment of carefully selected hospitalized patients with nonsevere diseases and without risk factors for drug-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae.5

Telithromycin is a ketolide antibiotic, which has been studied in mild to moderate CAP, including multidrug-resistant strains of S. pneumoniae, in courses of five to seven days.17 However, severe adverse reactions, including hepatotoxicity, have been reported. At the time of the 2007 guidelines, the IDSA/ATS committee waited for additional safety data before making any recommendations on its use.

One additional study of note was a trial of amoxicillin in adult inpatients with mild to moderately severe CAP.18 One hundred twenty-one patients who clinically improved (based on a composite score of pulmonary symptoms and general improvement) following three days of IV amoxicillin were randomized to oral amoxicillin for an additional five days or given a placebo. At days 10 and 28, there was no difference in clinical success between the two groups. The authors concluded that a total of three days of treatment was not inferior to eight days in patients who substantially improved after the first 72 hours of empiric treatment. This trial was conducted in the Netherlands, where amoxicillin is the preferred empiric antibiotic for CAP and patterns of antimicrobial resistance differ greatly from those found in the U.S.

Other considerations. While some evidence supports shorter courses of antibiotics, many of the existing studies are limited by their inclusion of outpatients, adults with mild to moderate CAP, or small sample size. Hence, clinical judgment continues to play an important role in determining the appropriate duration of therapy. Factors such as pre-existing co-morbidities, severity of illness, and occurrence of complications should be considered. Data is limited on the appropriate duration of antibiotics in CAP patients requiring intensive care. It also is important to note the IDSA/ATS recommendations and most of the studies reviewed exclude patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and it is unknown whether these shorter courses of antibiotics are appropriate in the HIV population.

Lastly, the IDSA/ATS guidelines note longer durations of treatment may be required if the initial therapy was not active against the identified pathogen, or in cases complicated by extrapulmonary infections, such as endocarditis or meningitis.

Back to the Case

Our patient with moderately severe CAP was hospitalized based on his age and hypoxia. He was immediately treated with supplemental oxygen by nasal cannula, IV fluids, and a dose of IV levofloxacin 750 mg. Within 48 hours he met criteria for clinical stability, including defervescence, a decline in his respiratory rate to 19 breaths per minute, and improvement in oxygen saturation to 95% on room air. At this point, he was changed from IV to oral antibiotics. He continued on levofloxacin 750 mg daily and later that day was discharged home in good condition to complete a five-day course.

Bottom Line

For hospitalized adults with mild to moderately severe CAP, five to seven days of treatment, depending on the antibiotic selected, appears to be effective in most cases. Patients should be afebrile for 48 to 72 hours and demonstrate signs of clinical stability before therapy is discontinued. TH

Kelly Cunningham, MD, and Shelley Ellis, MD, MPH, are members of the Section of Hospital Medicine at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tenn. Sunil Kripalani, MD, MSc, serves as the section chief.

References

1. Kung HC, Hoyert DL, Xu J, Murphy SL. Deaths: final data for 2005. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2008;56.

2. DeFrances CJ, Lucas CA, Buie VC, Golosinskiy A. 2006 National Hospital Discharge Survey. Natl Health Stat Report. 2008;5.

3. Niederman MS. Recent advances in community-acquired pneumonia: inpatient and outpatient. Chest. 2007;131:1205-1215.

4. Li JZ, Winston LG, Moore DH, Bent S. Efficacy of short-course antibiotic regimens for community-acquired pneumonia: a meta-analysis. Am J Med. 2007;120:783-790.

5. Mandell LA, Wunderink RG, Anzueto A et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society consensus guidelines on the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(Suppl 2):S27-72.

6. Ramirez JA, Bordon J. Early switch from intravenous to oral antibiotics in hospitalized patients with bacteremic community-acquired Streptococcus pneumoniae pneumonia. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:848-850.

7. Halm EA, Fine MJ, Marrie TJ et al. Time to clinical stability in patients hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia: implications for practice guidelines. JAMA. 1998;279:1452-1457.

8. Menendez R, Torres A, Rodriguez de Castro F et al. Reaching stability in community-acquired pneumonia: the effects of the severity of disease, treatment, and the characteristics of patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:1783-1790.

9. Siegal RE, Halpern NA, Almenoff PL et al. A prospective randomised study of inpatient IV antibiotics for community-acquired pneumonia: the optimal duration of therapy. Chest. 1996;110:965-971.

10. Oosterheert JJ, Bonten MJ, Schneider MM et al. Effectiveness of early switch from intravenous to oral antibiotics in severe community acquired pneumonia: multicentre randomized trial. BMJ. 2006;333:1193-1197.

11. Nathan RV, Rhew DC, Murray C et al. In-hospital observation after antibiotic switch in pneumonia: a national evaluation. Am J Med. 2006;119:512-518.

12. Dimopoulos G, Matthaiou DK, Karageorgopoulos DE, et al. Short- versus long-course antibacterial therapy for community-acquired pneumonia: a meta-analysis. Drugs. 2008;68:1841-1854.

13. Dunbar LM, Wunderink RG, Habib MP et al. High-dose, short-course levofloxacin for community-acquired pneumonia: a new treatment paradigm. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:752-760.

14. Morris DL, De Souza A, Jones JA, Morgan WE. High and prolonged pulmonary tissue concentrations of azithromycin following a single oral dose. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1991;10:859-861.

15. Contopoulos-Ioannidis DG, Ioannidis JPA, Chew P, Lau J. Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials on the comparative efficacy and safety of azithromycin against other antibiotics for lower respiratory tract infections. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2001;48:691-703.

16. Rizzato G, Montemurro L, Fraioli P et al. Efficacy of a three-day course of azithromycin in moderately severe community-acquired pneumonia. Eur Respir J. 1995;8:398-402.

17. Tellier G, Niederman MS, Nusrat R et al. Clinical and bacteriological efficacy and safety of 5- and 7-day regimens of telithromycin once daily compared with a 10-day regimen of clarithromycin twice daily in patients with mild to moderate community-acquired pneumonia. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2004;54:515.

18. El Moussaoui R, de Borgie CA, van den Broek P et al. Effectiveness of discontinuing antibiotic treatment after three days versus eight days in mild to moderate-severe community acquired pneumonia: randomised, double blind study. BMJ. 2006;332:1355-1361.

19. Siegel RE, Alicea M, Lee A, Blaiklock R. Comparison of 7 versus 10 days of antibiotic therapy for hospitalized patients with uncomplicated community-acquired pneumonia: a prospective, randomized double-blind study. Am J Ther. 1999;6:217-222.

Case

An 83-year-old male with hypertension, coronary artery disease, and obstructive sleep apnea presents with progressive shortness of breath, a productive cough, wheezing, and tachypnea. His blood pressure is 158/70 mm/Hg; temperature is 101.8; respirations are 26 breaths per minute; and oxygen saturation is 87% on room air. He has coarse breath sounds bilaterally, and decreased breath sounds over the right lower lung fields. His chest X-ray reveals a right lower lobe infiltrate. He is admitted to the hospital with a diagnosis of community-acquired pneumonia (CAP), and medical therapy is started. How should his antibiotic treatment be managed?

Overview

Community-acquired pneumonia is the most common infection-related cause of death in the U.S., and the eighth-leading cause of mortality overall.1 According to a 2006 survey, CAP results in more than 1.2 million hospital admissions annually, with an average length of stay of 5.1 days.2 Though less than 20% of CAP patients require hospitalization, cases necessitating admission contribute to more than 90% of the overall cost of pneumonia care.3

During the past several years, the availability of new antibiotics and the evolution of microbial resistance patterns have changed CAP treatment strategies. Furthermore, the development of prognostic scoring systems and increasing pressure to streamline resource utilization while improving quality of care have led to new treatment considerations, such as managing low-risk cases as outpatients.

More recently, attention has been directed to the optimal duration of antibiotic treatment, with a focus on shortening the duration of therapy. Historically, CAP treatment duration has been variable and not evidence-based. Shortening the course of antibiotics might limit antibiotic resistance, decrease costs, and improve patient adherence and tolerability.4 However, before defining the appropriate antibiotic duration for a patient hospitalized with CAP, other factors must be considered, such as the choice of empiric antibiotics, the patient’s initial response to treatment, severity of the disease, and presence of co-morbidities.

Review of the Data

Antibiotic choice. The most widely referenced practice guidelines for the management of CAP patients were published in 2007 by representatives of the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the American Thoracic Society (ATS).5 Table 1 (above, right) summarizes the recommendations for empiric antibiotics for patients requiring inpatient treatment.

Time to clinical stability. A patient’s clinical response to empiric antibiotic therapy contributes heavily to the decision regarding treatment course and duration. The IDSA/ATS guidelines recommend patients be afebrile for 48 to 72 hours and have no more than one CAP-associated sign of clinical instability before discontinuation of therapy. Although studies have used different definitions of clinical stability, the consensus guidelines refer to six parameters, which are summarized in Table 2 (right).

With appropriate antibiotic therapy, most patients hospitalized with CAP achieve clinical stability in approximately three days.6,7 Providers should expect to see some improvement in vital signs within 48 to 72 hours of admission. Should a patient fail to demonstrate objective improvement during that time, providers should look for unusual pathogens, resistant organisms, nosocomial superinfections, or noninfectious conditions.5 Certain patients, such as those with multilobar pneumonia, associated pleural effusion, or higher pneumonia-severity index scores, also take longer to reach clinical stability.8

Switch to oral therapy. The ability to achieve clinical stability has important implications for hospital length of stay. Most patients hospitalized with CAP initially are treated with intravenous (IV) antibiotics and require transition to oral therapy in anticipation of discharge. Several studies have found there is no advantage to continuing IV medication once a patient is deemed clinically stable and is able to tolerate oral medication.9,10 There are no specific guidelines regarding choice of oral antibiotics, but it is common practice, supported by the IDSA/ATS recommendations, to use the same agent as the IV antibiotic or a medication in the same drug class. For patients started on β-lactam and macrolide combination therapy, it usually is appropriate to switch to a macrolide alone.5 In cases in which a pathogen has been identified, antibiotic selection should be based on the susceptibility profile.

Once patients are switched to oral antibiotics, it is not necessary for them to remain in the hospital for further observation, provided they have no other active medical problems or social needs. A retrospective analysis of 39,232 patients hospitalized with CAP compared those who were observed overnight after switching to oral antibiotics with those who were not and found no difference in 14-day readmission rate or 30-day mortality rate.11 These findings, in conjunction with the strategy of an early switch to oral therapy, suggest hospital length of stay may be safely reduced for many patients with uncomplicated CAP.

Duration of therapy. After a patient becomes clinically stable and a decision is made to switch to oral medication and a plan for hospital discharge, the question becomes how long to continue the course of antibiotics. Historically, clinical practice has extended treatment for up to two weeks, despite lack of evidence for this duration of therapy. The IDSA/ATS guidelines offer some general recommendations, noting patients should be treated for a minimum of five days, in addition to being afebrile for 48 to 72 hours and meet other criteria for clinical stability.5

Li and colleagues conducted a systematic review evaluating 15 randomized controlled trials comparing short-course (less than seven days) with extended (more than seven days) monotherapy for CAP in adults.4 Overall, the authors found no difference in the risk of treatment failure between short-course and extended-course antibiotic therapy, and they found no difference in bacteriologic eradication or mortality. It is important to note the studies included in this analysis enrolled patients with mild to moderate CAP, including those treated as outpatients, which limits the ability to extrapolate to exclusively inpatient populations and more severely ill patients.

Another meta-analysis, published shortly thereafter, examined randomized controlled trials in outpatients and inpatients not requiring intensive care. It compared different durations of treatment with the same agent in the same dosage. The authors similarly found no difference in effectiveness or safety of short (less than seven days) versus longer (at least two additional days of therapy) courses.12 Table 3 (above) reviews selected trials of short courses of antibiotics, which have been studied in inpatient populations.

The trials summarized in these meta-analyses examined monotherapy with levofloxacin for five days; gemifloxacin for seven days, azithromycin for three to five days; ceftriaxone for five days; cefuroxime for seven days; amoxicillin for three days; or telithromycin for five to seven days. The variety of antibiotics in these studies contrasts the IDSA/ATS guidelines, which recommend only fluoroquinolones as monotherapy for inpatient CAP.

One important randomized, double-blind study of fluoroquinolones compared a five-day course of levofloxacin 750 mg daily, with a 10-day course of levofloxacin, 500 mg daily, in 528 patients with mild to severe CAP.13 The authors found no difference in clinical success or microbiologic eradication between the two groups, concluding high-dose levofloxacin for five days is an effective and well-tolerated alternative to a longer course of a lower dose, likely related to the drug’s concentration-dependent properties.

Azithromycin also offers potential for short courses of therapy, as pulmonary concentrations of azithromycin remain elevated for as many as five days following a single oral dose.14 Several small studies have demonstrated the safety, efficacy, and cost-effectiveness of three to five days of azithromycin, as summarized in a meta-analysis by Contopoulos-Ioannidis and colleagues.15 Most of these trials, however, were limited to outpatients or inpatients with mild disease or confirmed atypical pneumonia. One randomized trial of 40 inpatients with mild to moderately severe CAP found comparable clinical outcomes with a three-day course of oral azithromycin 500 mg daily versus clarithromycin for at least eight days.16 Larger studies in more severely ill patients must be completed before routinely recommending this approach in hospitalized patients. Furthermore, due to the rising prevalence of macrolide resistance, empiric therapy with a macrolide alone can only be used for the treatment of carefully selected hospitalized patients with nonsevere diseases and without risk factors for drug-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae.5

Telithromycin is a ketolide antibiotic, which has been studied in mild to moderate CAP, including multidrug-resistant strains of S. pneumoniae, in courses of five to seven days.17 However, severe adverse reactions, including hepatotoxicity, have been reported. At the time of the 2007 guidelines, the IDSA/ATS committee waited for additional safety data before making any recommendations on its use.

One additional study of note was a trial of amoxicillin in adult inpatients with mild to moderately severe CAP.18 One hundred twenty-one patients who clinically improved (based on a composite score of pulmonary symptoms and general improvement) following three days of IV amoxicillin were randomized to oral amoxicillin for an additional five days or given a placebo. At days 10 and 28, there was no difference in clinical success between the two groups. The authors concluded that a total of three days of treatment was not inferior to eight days in patients who substantially improved after the first 72 hours of empiric treatment. This trial was conducted in the Netherlands, where amoxicillin is the preferred empiric antibiotic for CAP and patterns of antimicrobial resistance differ greatly from those found in the U.S.

Other considerations. While some evidence supports shorter courses of antibiotics, many of the existing studies are limited by their inclusion of outpatients, adults with mild to moderate CAP, or small sample size. Hence, clinical judgment continues to play an important role in determining the appropriate duration of therapy. Factors such as pre-existing co-morbidities, severity of illness, and occurrence of complications should be considered. Data is limited on the appropriate duration of antibiotics in CAP patients requiring intensive care. It also is important to note the IDSA/ATS recommendations and most of the studies reviewed exclude patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and it is unknown whether these shorter courses of antibiotics are appropriate in the HIV population.

Lastly, the IDSA/ATS guidelines note longer durations of treatment may be required if the initial therapy was not active against the identified pathogen, or in cases complicated by extrapulmonary infections, such as endocarditis or meningitis.

Back to the Case

Our patient with moderately severe CAP was hospitalized based on his age and hypoxia. He was immediately treated with supplemental oxygen by nasal cannula, IV fluids, and a dose of IV levofloxacin 750 mg. Within 48 hours he met criteria for clinical stability, including defervescence, a decline in his respiratory rate to 19 breaths per minute, and improvement in oxygen saturation to 95% on room air. At this point, he was changed from IV to oral antibiotics. He continued on levofloxacin 750 mg daily and later that day was discharged home in good condition to complete a five-day course.

Bottom Line

For hospitalized adults with mild to moderately severe CAP, five to seven days of treatment, depending on the antibiotic selected, appears to be effective in most cases. Patients should be afebrile for 48 to 72 hours and demonstrate signs of clinical stability before therapy is discontinued. TH

Kelly Cunningham, MD, and Shelley Ellis, MD, MPH, are members of the Section of Hospital Medicine at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tenn. Sunil Kripalani, MD, MSc, serves as the section chief.

References

1. Kung HC, Hoyert DL, Xu J, Murphy SL. Deaths: final data for 2005. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2008;56.

2. DeFrances CJ, Lucas CA, Buie VC, Golosinskiy A. 2006 National Hospital Discharge Survey. Natl Health Stat Report. 2008;5.

3. Niederman MS. Recent advances in community-acquired pneumonia: inpatient and outpatient. Chest. 2007;131:1205-1215.

4. Li JZ, Winston LG, Moore DH, Bent S. Efficacy of short-course antibiotic regimens for community-acquired pneumonia: a meta-analysis. Am J Med. 2007;120:783-790.

5. Mandell LA, Wunderink RG, Anzueto A et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society consensus guidelines on the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(Suppl 2):S27-72.

6. Ramirez JA, Bordon J. Early switch from intravenous to oral antibiotics in hospitalized patients with bacteremic community-acquired Streptococcus pneumoniae pneumonia. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:848-850.

7. Halm EA, Fine MJ, Marrie TJ et al. Time to clinical stability in patients hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia: implications for practice guidelines. JAMA. 1998;279:1452-1457.

8. Menendez R, Torres A, Rodriguez de Castro F et al. Reaching stability in community-acquired pneumonia: the effects of the severity of disease, treatment, and the characteristics of patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:1783-1790.

9. Siegal RE, Halpern NA, Almenoff PL et al. A prospective randomised study of inpatient IV antibiotics for community-acquired pneumonia: the optimal duration of therapy. Chest. 1996;110:965-971.

10. Oosterheert JJ, Bonten MJ, Schneider MM et al. Effectiveness of early switch from intravenous to oral antibiotics in severe community acquired pneumonia: multicentre randomized trial. BMJ. 2006;333:1193-1197.

11. Nathan RV, Rhew DC, Murray C et al. In-hospital observation after antibiotic switch in pneumonia: a national evaluation. Am J Med. 2006;119:512-518.

12. Dimopoulos G, Matthaiou DK, Karageorgopoulos DE, et al. Short- versus long-course antibacterial therapy for community-acquired pneumonia: a meta-analysis. Drugs. 2008;68:1841-1854.

13. Dunbar LM, Wunderink RG, Habib MP et al. High-dose, short-course levofloxacin for community-acquired pneumonia: a new treatment paradigm. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:752-760.

14. Morris DL, De Souza A, Jones JA, Morgan WE. High and prolonged pulmonary tissue concentrations of azithromycin following a single oral dose. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1991;10:859-861.

15. Contopoulos-Ioannidis DG, Ioannidis JPA, Chew P, Lau J. Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials on the comparative efficacy and safety of azithromycin against other antibiotics for lower respiratory tract infections. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2001;48:691-703.

16. Rizzato G, Montemurro L, Fraioli P et al. Efficacy of a three-day course of azithromycin in moderately severe community-acquired pneumonia. Eur Respir J. 1995;8:398-402.

17. Tellier G, Niederman MS, Nusrat R et al. Clinical and bacteriological efficacy and safety of 5- and 7-day regimens of telithromycin once daily compared with a 10-day regimen of clarithromycin twice daily in patients with mild to moderate community-acquired pneumonia. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2004;54:515.

18. El Moussaoui R, de Borgie CA, van den Broek P et al. Effectiveness of discontinuing antibiotic treatment after three days versus eight days in mild to moderate-severe community acquired pneumonia: randomised, double blind study. BMJ. 2006;332:1355-1361.

19. Siegel RE, Alicea M, Lee A, Blaiklock R. Comparison of 7 versus 10 days of antibiotic therapy for hospitalized patients with uncomplicated community-acquired pneumonia: a prospective, randomized double-blind study. Am J Ther. 1999;6:217-222.