Article

Furuncular Myiasis in 2 American Travelers Returning From Senegal

Furuncular myiasis caused by Cordylobia anthropophaga larvae is commonly seen in Africa but rarely is diagnosed in travelers returning from the...

Elizabeth Noble Ergen, MD; Allison Hutsell King, NP-C; Malika Tuli, MD

Dr. Ergen is from the Division of Dermatology, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tennessee. Ms. King and Dr. Tuli are from Mid-South Dermatology and Skin Cancer Center, Bartlett, Tennessee.

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Correspondence: Elizabeth Noble Ergen, MD, Vanderbilt Division of Dermatology, 719 Thompson Ln, Ste 26300, Nashville, TN 37204 (elizabeth.n.case@vanderbilt.edu).

Although males are thought to be at higher risk for cutaneous leishmaniasis infection than females, other demographic and behavioral risk factors are not well defined. In a case series of US travelers diagnosed with cutaneous leishmaniasis between January 1985 and April 1990, Herwaldt et al9 found that 46% (27/59) were conducting field studies, while 39% (23/59) were tourists, visitors, or tour guides. At least 15 of the 58 travelers interviewed (26%) were in forested areas for 1 week or less, and of these 15 respondents, at least 6 had a maximum exposure of 2 days.9

Evidence suggests that cutaneous leishmaniasis is inefficiently diagnosed in the United States. One study showed that some patients may consult up to 7 physicians before a definitive diagnosis is made, and the median time from noticing eruption of the lesions to definitive treatment was 112 days.9 Several factors may contribute to delays and inefficiencies in diagnosis. First, the lesions of cutaneous leishmaniasis are varied in morphology, and although ulcers are thought to be the most commonly presenting lesions,11 there are no specific morphologic features that are pathognomonic for cutaneous leishmaniasis. Second, the temporal association with travel to endemic countries is not necessarily apparent, with lesions developing gradually or weeks after the patient returns home. In the one study, 17% (10/58) of patients were home for more than 1 month before they noticed skin lesions.9 Finally, definitive diagnosis requires biopsy or scraping of the lesion followed by PCR, special histopathological staining (Giemsa), or culture. Polymerase chain reaction is currently the best means of identifying the causative Leishmania species.12-14 However, since skin biopsies are not routine in primary care settings and few practitioners are familiar with PCR for identification of leishmaniasis, diagnosis is typically made only after referral to a specialist.

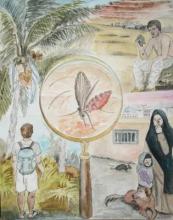

Leishmaniasis transmission occurs in diverse geographical settings though a variety of mechanisms (Figure 4). The morphology of cutaneous leishmaniasis varies and may include papules, nodules, psoriasiform plaques, or ulcers. The differential diagnosis may include staphylococcal skin infection, insect bite, cutaneous neoplasm, pyoderma gangrenosum, sporotrichosis, blastomycosis, chromomycosis, lobomycosis, cutaneous tuberculosis, atypical mycobacterial infection, syphilis, yaws, leprosy, Hansen disease, and sarcoidosis. A definitive diagnosis can be made only after identifying the causative parasite. A scraping or punch biopsy taken from a cleaned lesion provides an adequate sample. Identification can then be accomplished by histopathology, tissue culture, or PCR.5

Figure 4. Leishmania species can infect humans in diverse geographical scenarios. In Costa Rica (left), Leishmania panamensis and Leishmania braziliensis infection is common in locals and tourists. Forest rodents serve as the reservoir hosts and transmission is by the bite of the sand fly (center). In Iraq (top right), Leishmania major infection has been reported in soldiers. Reservoir hosts include desert rodents, and transmission occurs through the bite of the sand fly. Leishmania tropica infection is common in Kabul (bottom right) and occurs in humans, dogs, and rodents with transmission by the bite of the sand fly. Illustration by Elizabeth Noble Ergen, MD, Vanderbilt University Medical Center (Nashville, Tennessee).

We present a rhyme that can be used to promote greater awareness of cutaneous leishmaniasis among US health care practitioners:

Although clinical resolution of cutaneous leishmaniasis usually occurs over months to years, the unsightly appearance of the lesions as well as the potential for scarring and mucosal metastasis (associated with some species) drives medical treatment.15 Pentavalent antimonial drugs, which have been the mainstay of treatment for more than 50 years, remain the most popular treatment for cutaneous leishmaniasis. Two antimony compounds, sodium stibogluconate and meglumine antimoniate, often lead to clinical cure in less than 1 month7; however, these drugs are far from ideal because of the inconvenience of obtaining them, emerging parasite resistance, long treatment course, parenteral route of administration, and serious side effects including infusion reactions, arrhythmias, pancreatitis, and liver toxicity. Moreover, the subclinical persistence of cutaneous leishmaniasis years after treatment and clinical cure is common. There have been reports of spontaneous disease reactivation in immunocompromised individuals, and Leishmania has been detected in old cutaneous leishmaniasis scars on PCR testing.16-18 Other therapies that have been used to treat cutaneous leishmaniasis include allopurinol, aminosidine sulphate, amphotericin B, the Bacillus Calmette–Guérin vaccine, cotrimoxazole, cryotherapy, dapsone, fluconazole, itraconazole, ketoconazole, laser therapy, metronidazole, miltefosine, paromomycin, pentamidine, pentoxifylline, photodynamic therapy, rifampicin, and surgical excision of the entire lesion.8 A 2009 Cochrane review of the various treatments for cutaneous leishmaniasis concluded that “no general consensus on optimal treatment has been achieved” and suggested “the creation of an international platform to improve the quality and standardization of future trials in order to develop a better evidence-based approach.”8

Furuncular myiasis caused by Cordylobia anthropophaga larvae is commonly seen in Africa but rarely is diagnosed in travelers returning from the...

Global travel has become ubiquitous for recreational, occupational, educational, humanitarian, and other purposes. For this reason, those who...