The adult female patient presenting with severe acne vulgaris may raise special diagnostic concerns, including consideration of an underlying hormonal disorder. Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is the most common endocrine disorder in women of reproductive age with an estimated prevalence as high as 12%.1 Many women with undiagnosed PCOS may be referred to dermatologists for evaluation of its cutaneous manifestations of hyperandrogenism including acne, hirsutism, and androgenic alopecia.2 Given the prevalence of PCOS and its long-term health implications, dermatologists can play an important role in the initial evaluation of these patients. Acne and androgenic alopecia, however, are quite common, and in the absence of red flags such as menstrual irregularities, virilization, visual field deficits, or signs of Cushing syndrome,3 clinicians must decide when to pursue limited versus comprehensive evaluation.

Despite being common in patients with PCOS, a recent study suggests that acne is an unreliable marker of biochemical hyperandrogenism, and specific features of acne (ie, lesion counts, lesional types, distribution) cannot reliably discriminate women who meet PCOS diagnostic criteria from those who do not.4 Similarly, the study found that androgenic alopecia was not associated with biochemical hyperandrogenism and was no more common in women with PCOS than women of similar age in a high-risk population. Unlike acne and androgenic alopecia, however, the study identified hirsutism, especially truncal hirsutism, as a reliable indicator of hyperandrogenemia and PCOS. Hirsutism also is associated with metabolic sequelae of PCOS. These findings suggest that hirsutism, but not acne or androgenic alopecia, in a female of reproductive age warrants a workup for PCOS.4 This report is consistent with a recommendation from the Androgen Excess and Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Society (AE-PCOS) to pursue a diagnostic evaluation in any woman presenting with hirsutism.5 Acanthosis nigricans also was found to be a reliable indicator of hyperandrogenemia, PCOS, and associated metabolic derangement. Thus, although recent evidence indicates that acne as an isolated cutaneous finding does not warrant further diagnostic evaluation, acne in the setting of hirsutism, acanthosis nigricans, menstrual irregularities, or additional specific signs of endocrine dysregulation should prompt focused workup.4

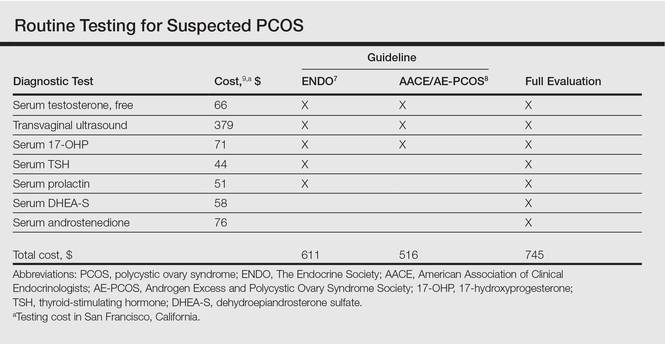

Multiple clinical practice guidelines for the evaluation of hirsutism and PCOS based on literature review and expert opinion have been proposed5-8; however, these guidelines vary in recommendations for routine diagnostic steps to exclude mimickers of PCOS such as prolactinoma/pituitary adenoma and congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH)(Table). In 2009, an AE-PCOS task force suggested that routine testing of thyroid function and serum prolactin in the absence of additional clinical signs may not be necessary based on the low prevalence of thyroid disorders and hyperprolactinemia in patients presenting with hyperandrogenism.6 In 2013, the Endocrine Society’s (ENDO) clinical guideline, however, recommended routine measurement of serum thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) to exclude thyroid disease and serum prolactin to exclude hyperprolactinemia in all women before making a diagnosis of PCOS.7 In 2015, the AE-PCOS collaborated with the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE) and American College of Endocrinology to publish an updated guideline for best practices, which was consistent with the prior AE-PCOS recommendation in 2009 for routine screening including to test 17-hydroxyprogesterone to exclude nonclassical CAH.8

Importantly, these recommendations for routine testing for mimickers of PCOS are based on the rare prevalence of these etiologies in multiple studies of women presenting for hyperandrogenism. One study included 873 women presenting to an academic reproductive endocrine clinic for evaluation of symptoms potentially related to androgen excess. In addition to cutaneous manifestations of hirsutism, acne, and alopecia, the study also included women presenting with oligomenorrhea/amenorrhea, ovulatory dysfunction, and even virilization.10 A second study included 950 women presenting to academic endocrine departments with hirsutism, acne, or androgenic alopecia.11 Both studies defined hirsutism as having a modified Ferriman-Gallwey score of 6 or greater. Both studies also only measured serum prolactin or TSH when clinically indicated (ie, patients with ovulatory dysfunction).10,11

The diagnostic yield of tests for mimickers of PCOS was exceedingly low in both studies. For example, of the patients evaluated, only 0.4% to 0.7% had thyroid dysfunction, 0% to 0.3% had hyperprolactinemia, 0.2% had androgen-secreting neoplasms, 2.1% to 4.3% had nonclassical CAH, 0.7% had CAH, and 3.8% had HAIR-AN (hyperandrogenism, insulin resistance, and acanthosis nigricans) syndrome.10,11 Because patients in both studies were only tested for hyperprolactinemia and thyroid dysfunction when clinically indicated, it is probable that routine screening without clinical indication would result in even lower yields.

Given the increasing importance of high-value, cost-conscious care,12 clinicians must consider the costs associated with testing in the face of low pretest probability. Although some studies have examined the cost-effectiveness of fertility treatments in PCOS,13,14 no studies have examined the cost-effectiveness of diagnostic strategies for PCOS. Cost-effectiveness studies are emerging to provide important guidance on high-value, cost-conscious diagnostic evaluation and monitoring15 and are much needed in dermatology.16,17