Video

Drs. Mott, Hunter, and Huerter are from Creighton University School of Medicine, Omaha, Nebraska. Drs. Mott and Huerter are from the Division of Dermatology, and Dr. Hunter is from the Department of Pathology. Dr. Silva is from the Department of Surgical Oncology, University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha.

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Correspondence: Christopher J. Huerter, MD, Creighton University School of Medicine, Department of Dermatology, 2500 California Plaza, Omaha, NE 68178-0408 (ChristopherHuerter@creighton.edu).

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is a common nonmelanoma skin cancer with increasing incidence in the United States and worldwide. It is strongly linked to UV radiation exposure and typically is slow growing. Malignancy in BCCs is due to local growth and invasion rather than metastasis, and the prognosis is generally favorable. We report the case of a 60-year-old man with a large, locally destructive giant BCC on the right side of the upper back that was successfully treated via complete surgical excision (SE) and did not recur in the subsequent 36 months. We review the indications, evidence, advantages, and disadvantages associated with multiple surgical and nonsurgical treatment modalities available for the management of giant BCCs.

Practice Points

Nonmelanoma skin cancer is the most common malignancy in the United States, with basal cell carcinoma (BCC) being the major histological subtype and accounting for approximately 80% of all skin cancers.1-3 The age-adjusted incidence of BCC in the United States between 2004 and 2006 was estimated at 1019 cases per 100,000 in women and 1488 cases per 100,000 in men, and an estimated 2.8 million new cases are diagnosed in the United States each year.3,4 Rates have been shown to increase with advancing age and are higher in males than females at all ages.3 Exposure to solar UVB radiation generally is considered to be the greatest risk factor for development of BCC.3,5,6 Severe or frequent sunburn and recreational exposure to sun in childhood (from birth to 19 years of age), particularly in individuals who tend to burn rather than tan, have been shown to substantially increase the risk for developing BCC as an adult.7 Additional risk factors include light skin color, red or blonde hair color, presence of a large number of moles on the extremities, and a family history of melanoma or painful/blistering sunburn reactions.3,7 Exposure to certain toxins, immunosuppression, and several genetic cancer syndromes also have been linked to BCC.5

Eighty percent of BCC cases involve the head and neck, with the trunk, arms, and legs being the next most common sites.5 Basal cell carcinoma can be classified by histologic subtype including nodular, superficial, nodulocystic, morpheic, metatypical, pigmented, and ulcerative, as well as other rarer forms.8 Elder9 recommended that it may be most clinically practical to divide BCC into subtypes that are known to have low (eg, nodular, nodulocystic) or relatively high risk for local recurrence (eg, infiltrating, morpheic, and metatypical).9,10 The most common histologic subtype is nodular BCC, with an incidence of 40% to 60%, which typically presents as a red to white pearly nodule or papule with a rolled border; overlying telangiectasia; and occasionally crusting, ulceration, or a cyst.5,11,12

Basal cell carcinoma generally is a slow-growing and highly curable form of skin cancer.5,13,14 Compared to either squamous cell carcinoma or melanoma, BCC is generally easier to treat and carries a more favorable prognosis with a lower incidence of recurrence and metastasis.15 Malignancy in BCC is due to local growth and destruction of the primary tumor rather than metastasis, which is quite rare (estimated to occur in 0.0028% to 0.55% of cases) but carries a poor prognosis.5,11,16 Basal cell carcinoma grows continuously along the path of least resistance, showing an affinity for the dermis, fascial planes, nerve sheaths, blood vessels, and lymphatic vessels. It is through these pathways that certain locally aggressive tumors can achieve great depths and distant spread. Tumors also are known to spread along embryonic fascial planes, which allows cells to extend in a direction perpendicular to the skin surface and achieve greater depths.13 Metastasis has been found to occur more frequently in white men, arising from large tumors larger than 7.5 cm on the head and neck with spread to local lymph nodes. The median survival rate in this group, even in patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy or radiation, is 10 months but is lower in patients with larger tumors and those who neglect to seek medical care.16 Although mortality is low, its high and increasing prevalence makes BCC an important and costly health problem in the United States.2,17

A 60-year-old white man with a history of diabetes mellitus presented to the dermatology clinic with concerns about a nonhealing sore on the right upper back that had been present for more than 10 years and had gradually increased in size. The patient reported he did not have health insurance and thus did not seek medical care. Despite the size and location of the lesion, he was able to maintain an active lifestyle and worked as a janitor without difficulty until shortly before presentation when the lesion began to ooze and bleed, requiring him to change the dressing multiple times each day. The patient had no systemic symptoms and described himself as an otherwise healthy man.

On evaluation, the patient was noted to have a 20×15-cm ulcerated tumor on the right side of the upper back and shoulder with no satellite lesions (Figure 1). There were no palpable lymph nodes or satellite lesions and the rest of the physical examination was unremarkable. An 8-mm shave biopsy was collected on the day of presentation and sent for pathology to evaluate for suspected malignancy. On histology, BCC was present with islands of tumor cells extending from the epidermis into the dermis (Figure 2). These nests of cells displayed classic peripheral palisading of hyperchromatic, ovoid-shaped, basaloid nuclei at the periphery. Clefting around islands of tumor cells in the dermis also was apparent. Several foci suggested squamous differentiation, but the bulk of the lesion suggested a conventional nodular BCC.

The patient was referred to a surgical oncologist who recommended a wide surgical excision (SE) and delayed split-thickness skin graft (STSG) due to the size and location of the lesion. Eighteen days after receiving the diagnosis of BCC, the patient was taken to the operating room and underwent wide en bloc resection of the soft tissue tumor. Upon lifting the specimen off the underlying muscles, it was found to be penetrating into portions of the trapezius, deltoid, paraspinal, supraspinalis, and infraspinatus muscles. As such, the ulcerated tumor was removed as well as portions of the underlying musculature measuring 21×18 cm. The wound was left open until final pathology on margin clearance was available. It was covered with a wound vac to encourage granulation in anticipation of a planned delayed STSG. There were no complications, and the patient returned to the recovery unit in good condition where the dressing was replaced with a large wound vac system.

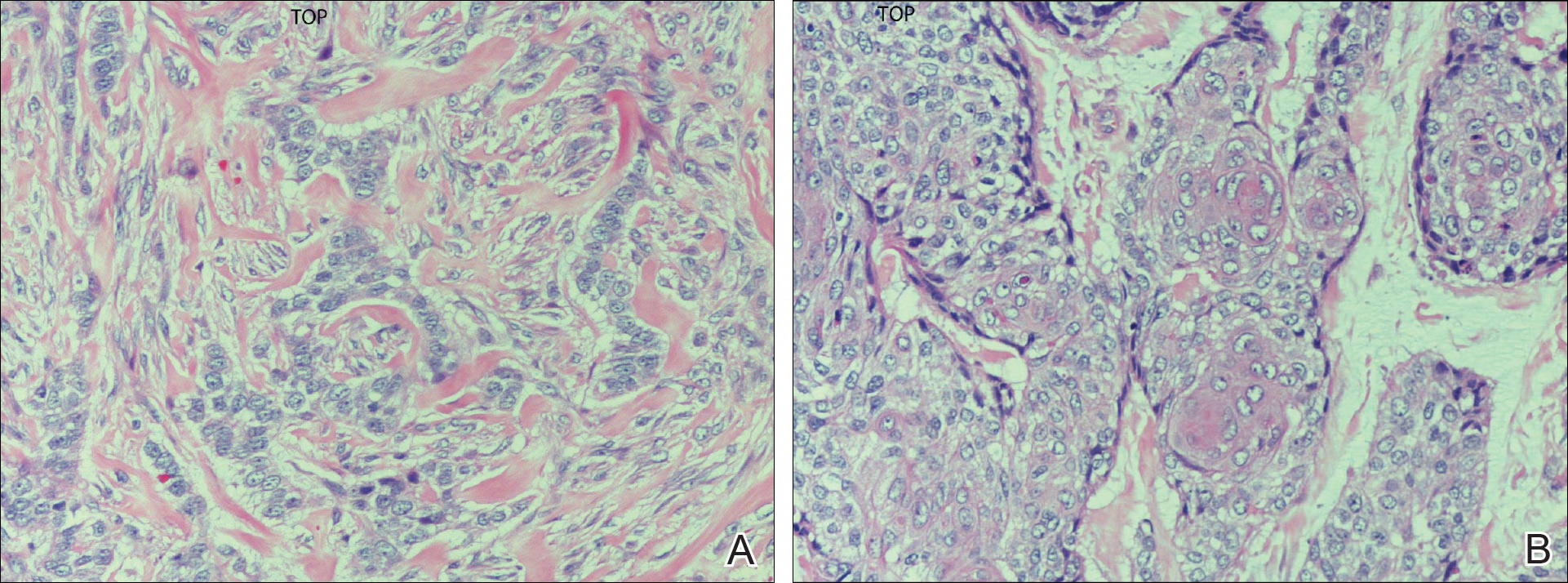

Final histologic examination showed negative deep and peripheral margins. More extensive examination of histology of the excised tumor was found to have characteristics consistent with metatypical and morpheic-type BCC. In addition to islands of tumor cells noted in the dermis on original biopsy, this sample also revealed basaloid cells arranged in thin elongated trabeculae invading deeper into the reticular dermis without peripheral palisading, suggestive of the morpheic variant (Figure 3A).8,9,10 Other areas were found to have focal squamous differentiation with keratin pearls and intercellular bridges (Figure 3B). These findings support the diagnosis of a completely excised BCC of the metatypical (referred to by some authorities as basosquamous)8,9 type.

Figure 3. Excisional biopsy of a giant basal cell carcinoma demonstrating invasion of the reticular dermis by trabeculae of basaloid cells, with the absence of islands and peripheral palisading (A) and a focal area of squamous differentiation. Note the formation of keratin pearls in the center (B)(both H&E, original magnification ×20).

The patient was seen for postoperative evaluations at 2 and 3 weeks. Each time granulation was noted to be proceeding well without signs of infection, and the wound vac was left in place. One month after the initial SE, the patient returned for the planned STSG. The skin graft was harvested from the right lateral thigh and was meshed and transferred to the recipient site on the right upper back, sewn circumferentially to the wound edges. Occlusive petrolatum gauze was placed over the graft followed by the wound vac for coverage until the graft matured.

The patient returned for follow-up approximately 7 months after his initial visit to the clinic. He reported feeling well, and his only concern was mild soreness of the scapular muscles while playing golf. The site of tumor excision showed 100% take of the STSG with no nodules in or around the site to suggest recurrence (Figure 4). The patient denied experiencing any constitutional symptoms and had no palpable lymph nodes or physical examination findings suggestive of metastatic disease or new tumor development at other sites. At 36 months after his initial clinic visit, he remained free of recurrence.

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most prevalent malignancy in white individuals and continues to be a serious health problem. Individuals who...

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common malignancy worldwide and is characterized by invasive growth and local tissue destruction. Cure...