Progressive macular hypomelanosis (PMH) is a noninflammatory skin disorder characterized by ill-defined, nummular, hypopigmented, and nonscaly macules. Historically, various names have been used to describe this entity. Several of these terms, including cutis trunci variata and nummular and confluent hypomelanosis of the trunk, reflected its predominantly truncal distribution.1,2 Less frequently, involvement on the neck, buttocks, and arms and legs has been noted.1,2 A lack of facial involvement previously has been highlighted as a key clinical feature of PMH.3

Progressive macular hypomelanosis is a diagnosis of exclusion. Hypopigmented diseases commonly considered in the differential include those caused by fungi and yeasts (eg, tinea versicolor, seborrheic dermatitis), inflammatory skin disorders (eg, pityriasis alba, postinflammatory dyschromia), and mycosis fungoides (MF) as well as leprosy.

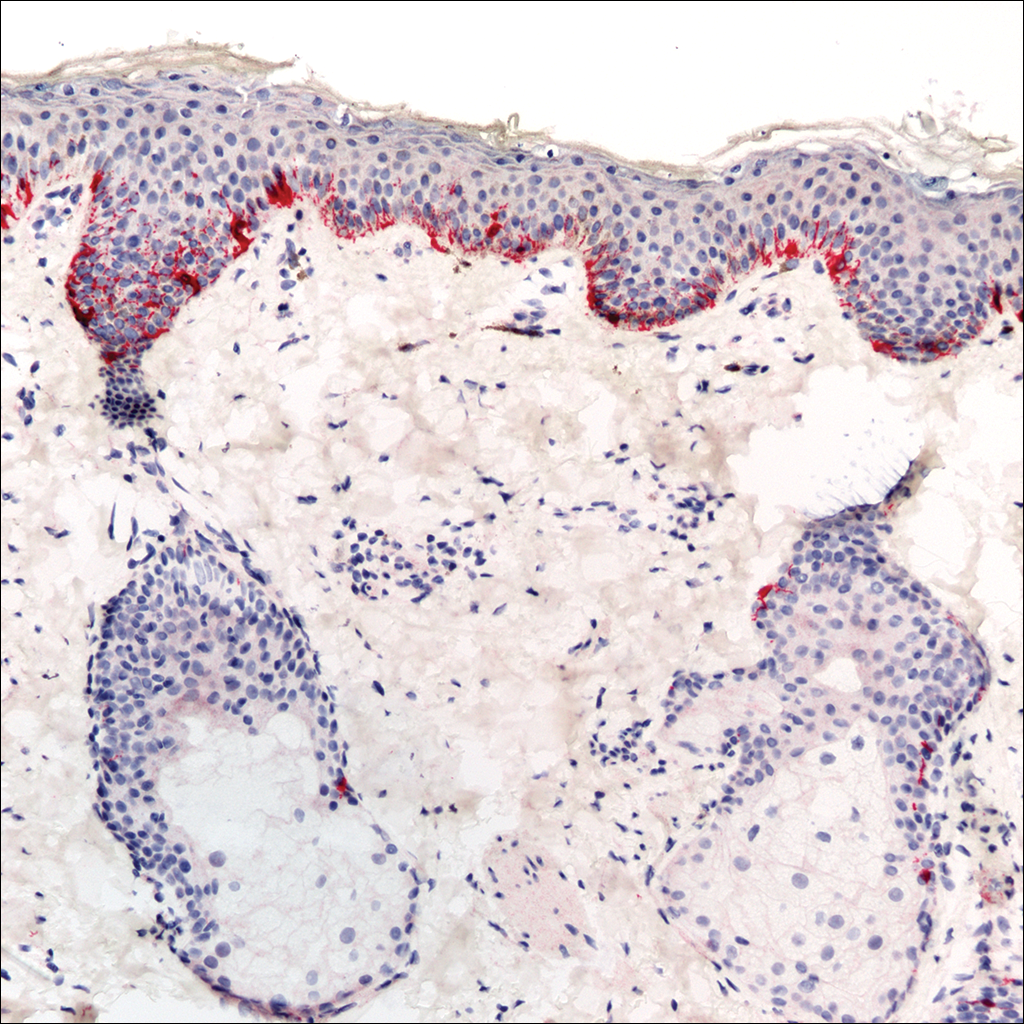

The hypopigmented macules of PMH have nonspecific histopathologic findings; lesional skin often shows minimal alterations as compared to normal skin. A sparse perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate often is observed,4,5 and at times, a decrease in epidermal melanin content can be detected.1-3,6,7

We report 4 cases with considerable facial involvement of hypopigmented macules that were determined to be consistent with PMH. We propose that characteristic macules that are not clinically or histopathologically consistent with other disease entities are compatible with a diagnosis of PMH, regardless of the distribution. A diagnosis of PMH should be considered in the differential when there are suggestive facial lesions in addition to truncal lesions.

Case Reports

Patient 1

A 40-year-old man presented with hypopigmented macules on the face (Figure 1), trunk, chest, arms, and legs of 2 years’ duration. The lesions were asymptomatic and had started on the forehead as hypopigmented macules, then progressed to the trunk, arms, and legs. The patient denied any prior rash, injury, or hyperpigmentation associated with the distribution of the lesions.

A rapid plasma reagin (RPR) test was conducted to rule out secondary syphilis and was nonreactive. During a series of clinical encounters over several months, a total of 5 biopsies of lesions on the face and back were performed. All specimens contained mild mononuclear perivascular inflammation (Figure 2). In some foci, staining for Melan-A revealed a decrease in epidermal melanocytes (Figure 3). Periodic acid–Schiff staining performed on one section revealed a few pityriasis spores but no hyphal elements, suggesting colonization rather than infection.

The patient initially was started on tacrolimus ointment 0.1% once daily and narrowband UVB phototherapy twice weekly for 3 months without benefit. A diagnosis of tinea versicolor was revisited and the patient was switched to ketoconazole shampoo 1% two to 3 times weekly on the face, trunk, arms, and legs for 10 to 15 minutes prior to rinsing, and ketoconazole cream 2% was applied twice daily to the affected areas for 2 months without notable improvement. Once-weekly 150-mg pulse doses of oral fluconazole for 8 weeks were started but proved equally ineffective. Antibiotic therapy aimed at eradicating Propionibacterium acnes was considered following a provisional diagnosis of PMH after the patient failed 5 months of therapy for tinea versicolor.

Patient 2

A 54-year-old man presented with hypopigmented to depigmented nonscaly macules on the face, trunk, chest, and arms of several months’ duration. The patient initially noted hypopigmentation on the face that gradually spread to the rest of the body. The patient denied any prior rash or hyperpigmentation in the affected areas. At the initial visit to our clinic, a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation of the face and back was positive for tinea versicolor. The patient was treated with ketoconazole shampoo 1% two to 3 times weekly for several weeks on the scalp, face, trunk, arms, and legs for 10 to 15 minutes prior to rinsing and 2 total doses of oral fluconazole 150 mg taken 1 week apart.

Three months later the patient returned with no improvement of the existing lesions and with progression of the disease to previously uninvolved areas of the trunk, arms, and legs. Biopsy of a facial lesion was performed, and laboratory studies including RPR, thyroid-stimulating hormone, and antinuclear antibody tests were conducted to screen for possible systemic disease. Microscopic analysis of the biopsied facial lesion revealed a sparse perivascular infiltrate of lymphocytes and plasma cells but no evidence of yeast or hyphal elements. Melan-A staining did not reveal a decreased number of epidermal melanocytes. All laboratory studies were negative or within normal limits. Desonide ointment 0.05% was prescribed to relieve the patient’s occasional pruritus. Although the patient’s symptoms resolved, the hypopigmented macules continued to progress, making a diagnosis of PMH more likely given the lack of improvement on treatment for tinea versicolor. Pimecrolimus cream 1% was started with discontinuation of desonide for steroid-sparing therapy.

Patient 3

A 63-year-old man presented with progressive nonscaly and asymptomatic hypopigmented macules on the face, trunk, abdomen, and back of 5 years’ duration. He first noted lesions on the abdomen and they subsequently spread to the rest of the body. The patient denied any prior rash, hyperpigmentation, or other lesions in the involved areas.

One year prior to the current presentation, KOH scrapings from the lesions performed by an outside physician were negative. During his initial visit to our clinic, an abdominal biopsy was performed, and histopathologic analysis showed postinflammatory pigmentary alteration; however, the patient denied any prior history of rash or injury in the distribution of the lesions that would correlate with the histopathologic findings of postinflammatory pigmentation. Because the histopathologic findings showed postinflammatory pigmentary alteration, additional stains including Melan-A were not performed.

The patient was provisionally treated with ketoconazole shampoo 1% two to 3 times weekly on the face, trunk, arms, and legs for 10 to 15 minutes prior to rinsing and ketoconazole cream 2% twice daily to the affected areas. After several months on this regimen, the patient did not report any improvement. An abdominal skin biopsy was again performed and revealed similar histopathology. Periodic acid–Schiff staining was negative for fungus. A diagnosis of PMH was made, and the patient was started on benzoyl peroxide wash 5% and clindamycin lotion.

Patient 4

A 45-year-old woman presented with hypopigmented, nonscaly macules on the face, neck, chest, trunk, and back. She first noted the lesions on the face and trunk more than 8 years prior, and they subsequently progressed. Potassium hydroxide scrapings performed on the lesions at the current presentation were negative, and a skin biopsy from the neck revealed postinflammatory pigmentary alteration, although the patient had no history of rash or injury in the areas in which the lesions were distributed.

Fontana-Masson and Melan-A staining of the skin biopsy of the neck revealed a normal distribution of melanocytes and pigment at the dermoepidermal junction. An RPR test was nonreactive. A diagnosis of PMH was made, and the patient was started on benzoyl peroxide wash 5% and clindamycin phosphate lotion 1%.