Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most frequently diagnosed skin cancer in the United States. It develops most often on sun-exposed skin, including the face and neck. Although BCCs are slow-growing tumors that rarely metastasize, they can cause notable local destruction with disfigurement if neglected or inadequately treated. Basal cell carcinoma arising on the legs is relatively uncommon.1,2 We present an interesting case of delayed diagnosis of BCC on the left knee due to earlier misdiagnoses of a dermoid cyst and bursitis.

Case Report

A 67-year-old man with no history of skin cancer presented with a painful growing tumor on the left knee of approximately 2 years’ duration. The patient’s primary care physician as well as a general surgeon initially diagnosed it as a dermoid cyst and bursitis. The nodule failed to respond to conservative therapy with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and continued to grow until it began to ulcerate. Concerned about the possibility of septic arthritis, the patient’s primary care physician referred him to the emergency department. He was subsequently sent to the dermatology clinic.

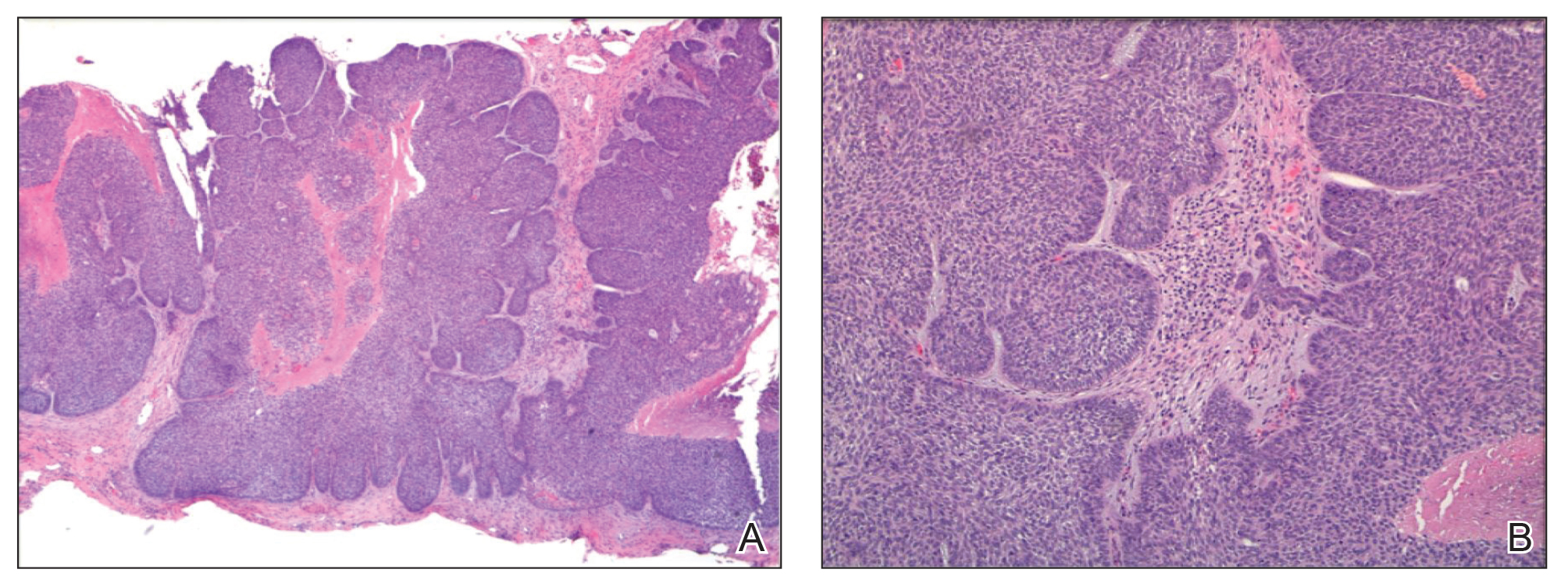

On examination by dermatology, a 6.3×4.4-cm, tender, mobile, ulcerated nodule was noted on the left knee (Figure 1A). No popliteal or inguinal lymph nodes were palpable. Basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, or atypical infection (eg, Leishmania, deep fungal, mycobacterial) was suspected clinically. The patient underwent a diagnostic skin biopsy; hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections revealed lobular proliferation of basaloid cells with peripheral palisading and central tumoral necrosis, consistent with primary BCC (Figure 2).

Figure 2. A, Lobular proliferation of basaloid cells with peripheral palisading and central tumoral necrosis. A, Dermal fibrosis and chronic inflammation were present (H&E, original magnification ×40). B, Proliferation of atypical basaloid cells with hyperchromatic nuclei, scant cytoplasm, scattered mitoses, tumoral necrosis, and peripheral palisading. Intratumoral and extratumoral mucin deposition was present (H&E, original magnification ×100).

Given the size of the tumor, the patient was referred for Mohs micrographic surgery and eventual reconstruction by a plastic surgeon. The tumor was cleared after 2 stages of Mohs surgery, with a final wound size of 7.7×5.4 cm (Figure 1B). Plastic surgery later performed a gastrocnemius muscle flap with a split-thickness skin graft (175 cm2) to repair the wound.

Comment

Exposure to UV radiation is the primary causative agent of most BCCs, accounting for the preferential distribution of these tumors on sun-exposed areas of the body. Approximately 80% of BCCs are located on the head and neck, 10% occur on the trunk, and only 8% are found on the lower extremities.1

Giant BCC, the finding in this case, is defined by the American Joint Committee on Cancer as a tumor larger than 5 cm in diameter. Fewer than 1% of all BCCs achieve this size; they appear more commonly on the back where they can go unnoticed.2 Neglect and inadequate treatment of the primary tumor are the most important contributing factors to the size of giant BCCs. Giant BCCs also have more aggressive biologic behavior, with an increased risk for local invasion and metastasis.3 In this case, the lesion was larger than 5 cm in diameter and occurred on the lower extremity rather than on the trunk.

This case is unusual because delayed diagnosis of BCC was the result of misdiagnoses of a dermoid cyst and bursitis, with a diagnostic skin biopsy demonstrating BCC almost 2 years later. It should be emphasized that early diagnosis and treatment could prevent tumor expansion. Physicians should have a high degree of suspicion for BCC, especially when a dermoid cyst and knee bursitis fail to respond to conservative management.