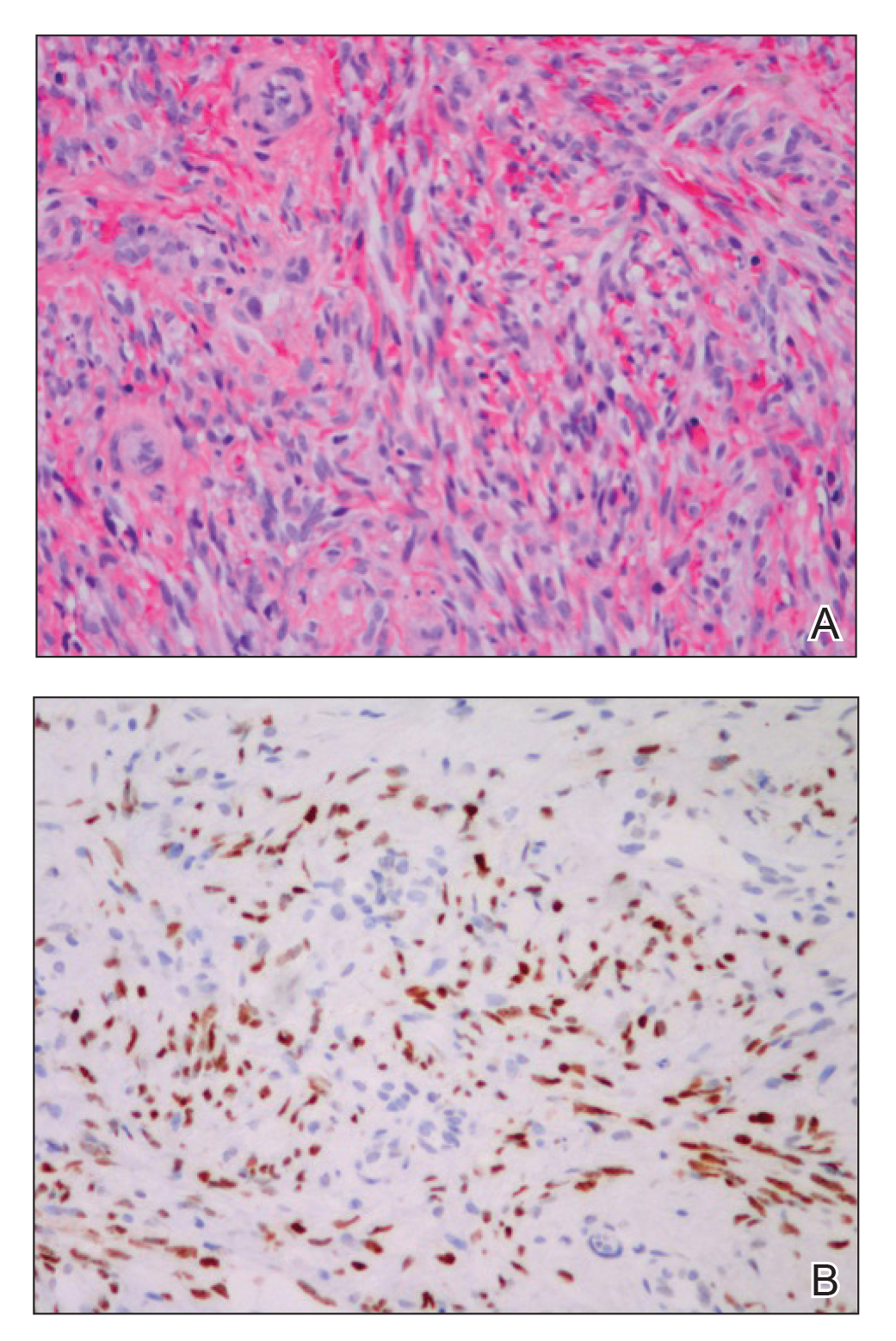

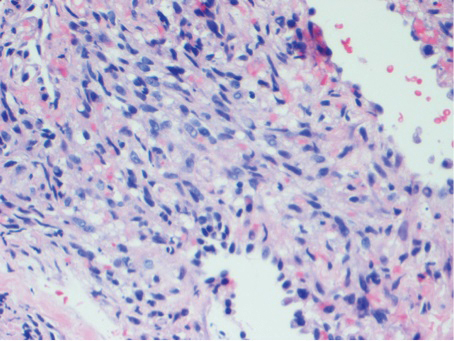

Histologic examination of biopsies of the penile lesions revealed spindle cell proliferation with hemorrhage (Figure 2A) that stained positively for HHV-8 (Figure 2B), consistent with KS. Biopsies taken during bronchoscopy similarly revealed spindle cells with hemorrhage (Figure 3). The patient was diagnosed with AIDS-related KS with visceral involvement of the lung parenchyma and tracheobronchial tree. The patient was then admitted to the medical intensive care unit and intubated. Therapy with HAART and paclitaxel was initiated. After 7 days of poor response to therapy, the family opted for terminal extubation and comfort care measures. The patient died hours later.

This case report describes the classic phenomenon of AIDS-related KS in a patient with a long-standing history of immunocompromise. Even in the era of HAART, this patient developed a severe form of visceral KS with involvement of the respiratory tract and lung parenchyma.

Since the advent of HAART for the treatment of HIV/AIDS, the incidence of KS, both visceral and cutaneous forms, has dramatically declined; the risk for visceral KS declined by more than 50% but less than 30% for cutaneous KS, supporting the observation that although visceral involvement has classically been noted as the more aggressive and life-threatening form of disease, HAART appears to have a stronger effect on visceral disease than cutaneous disease.3 Although the overall impact of AIDS-defining illnesses has substantially improved over the years, those with AIDS infection remain at risk for opportunistic illness.2

It has been shown that HAART therapy leads to response in more than 50% of cases of KS.5 The administration of HAART in KS patients is associated with improved survival and an 80% reduced risk of death, even when started after KS is diagnosed.6 In a comparison of the differences in clinical manifestations of KS between patients who were already receiving HAART at the time of KS diagnosis to those who were not on HAART, it was shown that patients already on therapy presented with less aggressive clinical features. A smaller percentage of patients who were already on HAART at KS diagnosis presented with visceral disease compared to those who were not on therapy.7

It is evident that treatment of AIDS patients with HAART is not only first-line therapy for the disease but also the best preventative measure against development of KS. Management of KS also centers around the initiation of HAART if the patient is not already maintained on the proper therapy.8 In addition to HAART, treatment options for visceral KS include a variety of chemotherapeutic agents, including but not limited to the use of single-agent adriamycin, vinblastine, paclitaxel, and thalidomide, or combination therapies.

Although notable advances have been made in the management of AIDS patients, this case highlights the need for clinicians to be aware of the risk for KS in the context of immunocompromise. Specifically, patients with advanced AIDS who are not adherent to HAART or who have a poor response to therapy have an amplified risk for developing KS in general as well as an increased risk for developing more severe visceral KS. Maintenance of patients with HAART is shown to greatly reduce the risk for both cutaneous and visceral KS; therefore, patient adherence with therapy is of utmost importance in preventing the occurrence of this deadly disease and its complications. Appropriate follow-up should be made, ensuring that these patients at high risk are adherent to therapy and have proper access to medical care to allow for prevention and early identification of potential complications.