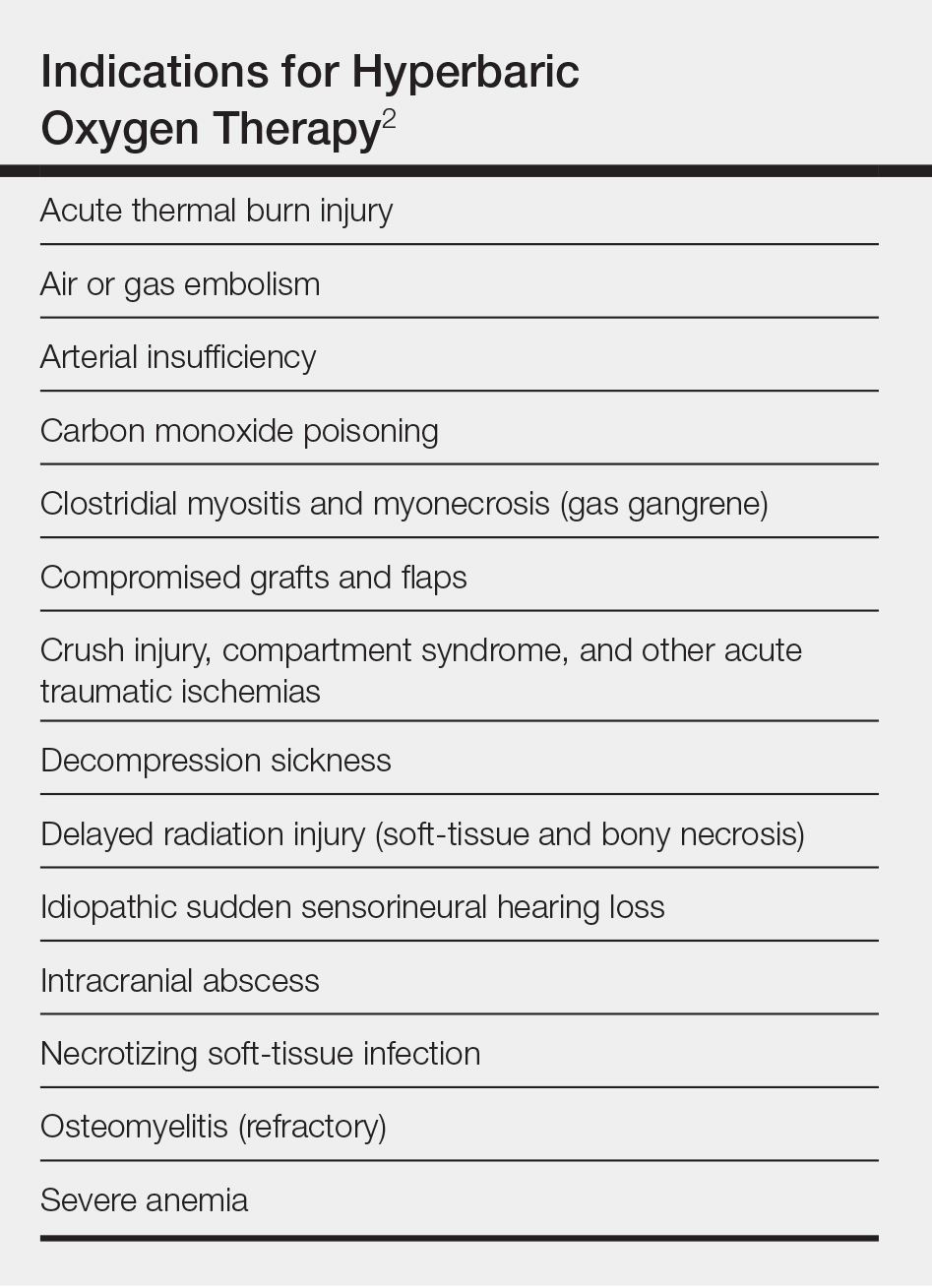

Hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HOT) is a treatment modality dating to 1861 in the United States.1 Today, there are 14 indications2 for HOT (Table), issued by the Undersea & Hyperbaric Medical Society, which also administers an accreditation program for facilities providing HOT.3 The 14 indications also are relevant because it is unlikely that HOT will be covered by insurance for unapproved indications.4

Although HOT is not commonly seen as a first-line intervention in dermatology, there are scenarios in which it can be used to good effect: compromised grafts and flaps; poorly healing ulceration related to vasculitis and autoimmune disorders; and possibly for vascular compromise, including cutaneous ischemia caused by fillers. We review its indications, dermatologic applications, and potential complications.

Overview of HOT

Hyperbaric oxygen therapy involves sitting or lying in a special chamber that allows for controlled levels of oxygen (O2) at increased atmospheric pressure, which specifically involves breathing near 100% O2 while inside a monoplace or multiplace chamber5 that is pressurized to greater than sea level pressure (≥1.4 atmosphere absolute).2

A monoplace chamber is designed to treat a single person (Figure 1); a multiplace chamber (Figure 2) accommodates as many as 5 to 25 patients.5,6 The chambers also accommodate hospital beds and medical attendants, if needed. Hyperbaric O2 is inhaled through a mask, a tight-fitting hood, or an endotracheal tube, depending on the patient’s status.7 Treatment ranges from only 1 or 2 iterations for acute conditions to 30 sessions or more for chronic conditions. Individual sessions last 45 minutes to 5 hours; 120 minutes is considered a safe maximum duration.7 A television often is provided to help the patient pass the time.8

Long-standing Use in Decompression Sickness

Hyperbaric oxygen therapy is best known for its effectiveness in treating decompression sickness (DCS) and carbon monoxide poisoning. Decompression sickness involves liberation of free gas from tissue, in the form of bubbles, when a person experiences a relative decrease in atmospheric pressure, which results in an imbalance in the sum of gas tensions in tissue compared to ambient pressure.