Mycosis fungoides (MF), the most common variant of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, is a non-Hodgkin lymphoma of T-cell origin that primarily develops in the skin and has a chronic relapsing course. Early-stage MF (stages IA–IIA) is defined as papules, patches, or plaques with limited (if any) lymph node and blood involvement and no visceral involvement.1 Early-stage MF has a favorable prognosis, and first-line treatments are skin-directed therapies including topical corticosteroids (CSs), topical chemotherapy (nitrogen mustard or carmustine), topical retinoids, topical imiquimod, local radiation, or phototherapy.2 Topical CSs are effective in treating early-stage MF and have been widely used for this indication for several decades; however, there are very little data in the literature on topical CS use in MF.3 Superpotent topical CSs have been shown to have a high overall response rate in early-stage MF3; however, cutaneous side effects associated with long-term topical use include cutaneous atrophy, striae formation, skin fragility, and irritation.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved bexarotene gel and mechlorethamine gel for topical treatment of cutaneous lesions in patients with stage IA and IB MF in 2000 and 2013, respectively. Although each may be effective in achieving complete or partial response in MF, both agents are associated with cutaneous side effects, mainly irritation and frequent contact hypersensitivity reactions, respectively.4,5 Additionally, their high prices and limited availability are other major drawbacks of treatment.

At our institution, high-potency topical CSs, specifically once or twice daily clobetasol propionate cream 0.05% prescribed as monotherapy for at least several months, remain the mainstay of treatment in patients with limited patches, papules, and plaques covering less than 10% of the skin surface (stage IA). In this study, we aimed to assess the risk of cutaneous side effects in patients with early-stage MF who were treated with long-term, high-potency topical CSs.

Methods

This prospective observational cohort study included patients with early-stage MF who were seen at the Cutaneous Lymphoma Clinic at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) in New York, New York, and were started on a superpotent (class I) topical CS (clobetasol propionate cream 0.05%) as monotherapy for MF from July 2016 to July 2017. The diagnosis of MF had to be supported by clinical findings and histopathologic features. All patients were Fitzpatrick skin types I, II, or III. Eligible patients were evaluated for development of CS-induced cutaneous AEs by physical examination and clinical photography of the treated lesions performed at baseline and as part of routine follow-up visits (usually scheduled every 2 to 6 months) at the MSKCC Cutaneous Lymphoma Clinic. Patients’ skin was evaluated clinically for MF activity, atrophy, telangiectasia, purpura, hypopigmentation, and stretch marks (striae). Use of the topical CS was self-reported and also was documented at follow-up visits. Treatment response was defined as follows: complete clinical response (CCR) if the treated lesions resolved completely compared to initial photography; minimal active disease (MAD) if resolution of the vast majority (≥75%) of lesions was seen; and partial response (PR) if some of the lesions resolved (<75%). We analyzed the treatment response rates and adverse effects (AEs). Results were summarized using descriptive statistics.

Results

We identified 13 patients who were started on topical clobetasol propionate as monotherapy for early-stage MF during the study period. Our cohort included 6 males and 7 females aged 36 to 76 years (median age, 61 years). All but 1 participant were diagnosed with stage IA MF (12/13 [92.3%]); of those, 9 (75.0%) had patch-stage disease and 3 (25.0%) presented with plaques. One (7.7%) participant presented with hyperpigmented patches and plaques that involved a little more than 10% of the skin surface (stage IB), and involvement of the hair follicles was noted on histology (folliculotropic MF). All prior treatments were stopped when participants started the superpotent topical CS: 6 (46.2%) participants had been treated with lower-potency topical agents and 1 (7.7%) participant was getting psoralen plus UVA therapy, while the other 6 (46.2%) participants were receiving no therapy for MF prior to starting the study. All participants were prescribed clobetasol propionate cream 0.05% once or twice daily as monotherapy and were instructed to apply it to the MF lesions only, avoiding skin folds and the face. One participant was lost to follow-up, and another stopped using the clobetasol propionate cream after 1.5 months due to local irritation associated with treatment. At their follow-up visits, the other 11 participants were advised to continue with once-daily treatment with clobetasol propionate or were tapered to once every other day, twice weekly, or once weekly depending on their response to treatment and AEs (Table). Participants were advised not to use more than 50 g of clobetasol propionate cream weekly.

All participants responded to the clobetasol propionate cream, and improvement was noted in the treated lesions; however, progression of disease (from stage IA to stage IB) occurred in 1 (8.3%) participant, and phototherapy was added with good response. The participants in our cohort were followed for 4 to 17 months (median, 11.5 months). At the last follow-up visit, all 12 participants showed treatment response: 4 (33.3%) had CCR, 5 (41.7%) had MAD; and 3 (25.0%) had PR. In one participant with a history of partial response to bexarotene gel 1%, daily clobetasol propionate cream 0.05% initially was used alone for 9 months and was later combined with bexarotene gel once weekly, resulting in MAD.

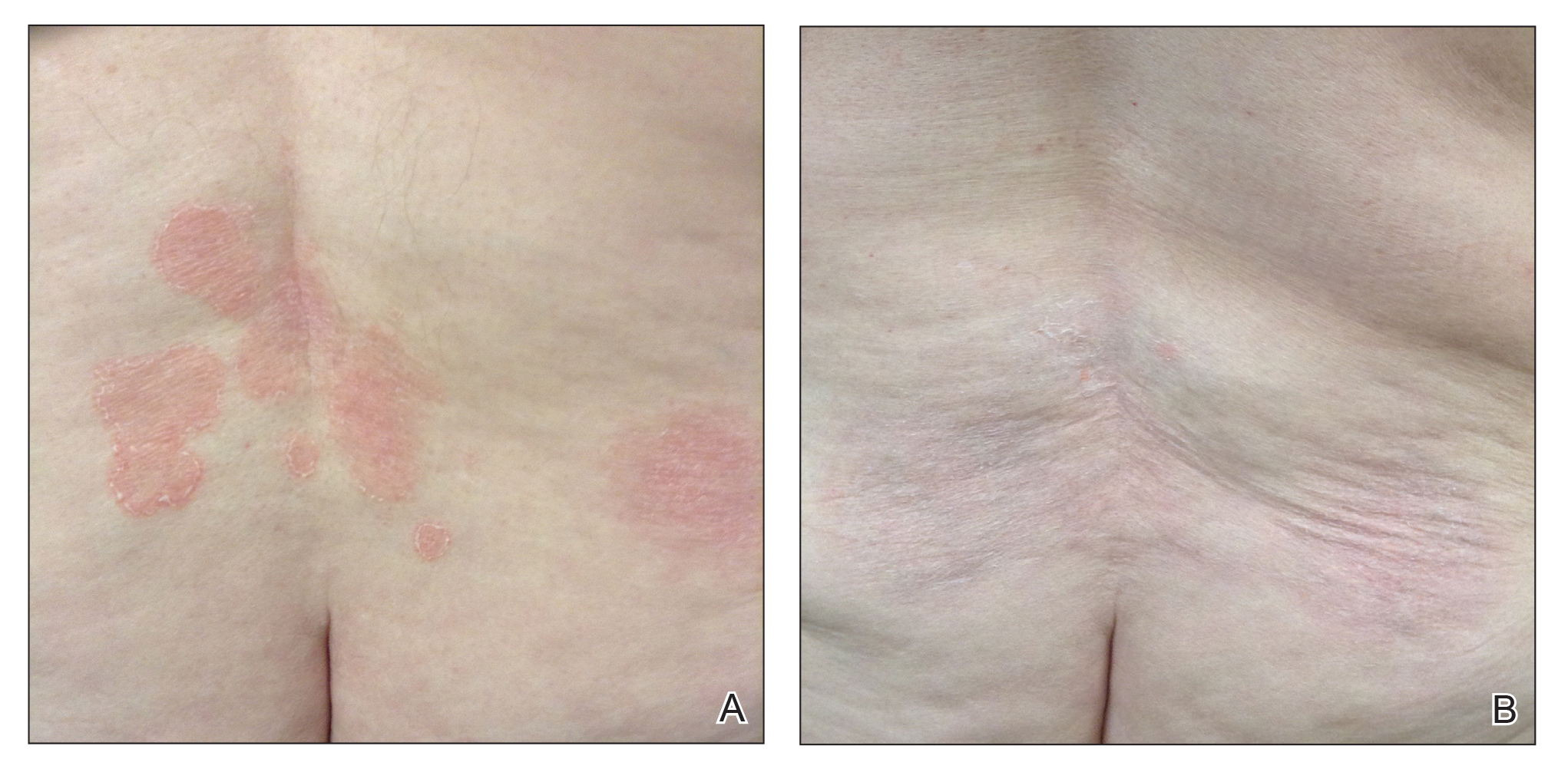

In 7 (58.3%) participants, no AEs to topical clobetasol propionate were recorded. Four (33.3%) participants developed local hypopigmentation at the application site, and 2 (16.7%) developed cutaneous atrophy with local fine wrinkling of the skin (Figure 1); none of the participants developed stretch marks (striae), telangiectases, or skin fragility. One (8.3%) participant developed a petechial rash at the clobetasol propionate application site that resolved once treatment was discontinued and did not recur after restarting clobetasol propionate twice weekly.