To the Editor:

Purpura fulminans (PF) is an acute, life-threatening condition characterized by intravascular thrombosis and hemorrhagic necrosis of the skin. It classically presents as retiform purpura with branched or angular purpuric lesions. Purpura fulminans often occurs in the setting of disseminated intravascular coagulation, secondary to sepsis, trauma, malignancy, autoimmune disease, and congenital or acquired protein C or S deficiency, among other abnormalities.1 Rapid identification and treatment of the underlying cause are mainstays of management. We report a case of PF secondary to Vibrio vulnificus infection and highlight the importance of timely consideration of this etiologic agent due to the high mortality rate and specific treatment required.

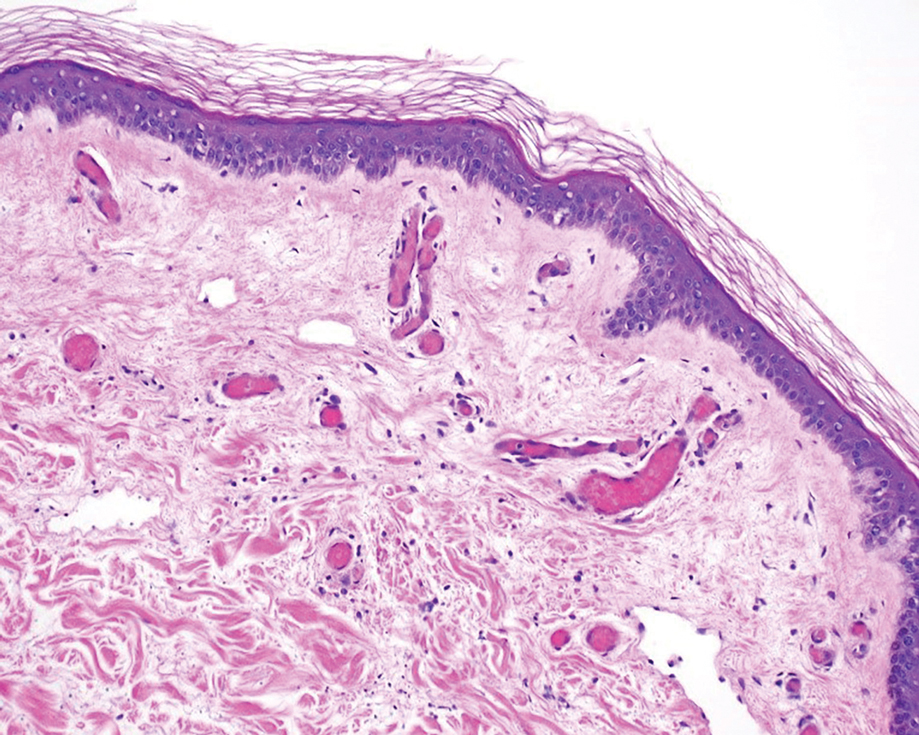

A 58-year-old man with liver cirrhosis and hepatitis B virus presented with pain, swelling, and localized erythema affecting both legs as well as a fever. He reported vomiting blood and an episode of bloody diarrhea over the preceding 24 hours. He denied exposure to sick contacts or a history of autoimmune disease. At initial presentation to the emergency department, physical examination revealed few scattered, sharply demarcated, erythematous to violaceous patches that rapidly progressed overnight to hemorrhagic bullae and widespread retiform purpuric patches on both legs (Figure 1). As the patient’s skin condition worsened, he had a blood pressure of 80/50 mm Hg and a pulse rate of 110/min. Serum analysis was notable for mild leukocytosis (10.74×109/L [reference range, 4.8–10.8×109/L), thrombocytopenia (39×109/L [reference range, 150–450×109/L]), and decreased C3 (25 mg/dL [reference range, 81–157 mg/dL]) and C4 (8 mg/dL [reference range, 13–39 mg/dL]). Laboratory findings also were remarkable for prothrombin time (23.3 seconds [reference range, 8.8–12.3 seconds]), partial thromboplastin time (52.5 seconds [reference range, 23.6–35.8 seconds]), and international normalized ratio (2.01 [reference range, 0.8–1.13]). Aspartate transaminase (237 U/L [reference range, 11–39 U/L]) and alanine transaminase (80 U/L [reference range, 11–35 U/L]) were elevated, while antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, serum immunoglobulin, and cryoglobulins were unremarkable. Punch biopsies of the left thigh were performed, and histopathology revealed small vessel thrombosis and ischemic changes consistent with PF (Figure 2). Vancomycin, clindamycin, cefepime injection, and piperacillin-tazobactam were administered intravenously for empiric broad-spectrum sepsis coverage. Within hours, the patient experienced refractory septic shock with disseminated intravascular coagulation and died from pulmonary embolism and subsequent cardiac arrest. Tissue and blood cultures grew V vulnificus.

Vibrio vulnificus is a gram-negative bacillus and a rare cause of primary septicemia following consumption of shellfish, especially oysters. Wounds exposed to saltwater or brackish water contaminated with the microorganism can produce soft-tissue infections. Individuals with chronic liver disease are at greater risk for V vulnificus infection.2 The clinical presentation of V vulnificus includes early cellulitislike patches, late purpura with hemorrhagic bullae, and rapidly progressing shock.3

Mortality rates from V vulnificus infection are high.4 Therefore, it is recommended to presumptively diagnose V vulnificus septicemia in any individual at risk for infection who presents with the characteristic history in the setting of hypotension, fever, or septic shock. It is crucial for providers to be aware that broad-spectrum antibiotics commonly used for sepsis are inadequate for the treatment of V vulnificus. Immediate treatment with tetracycline (minocycline or doxycycline) and a third-generation cephalosporin (cefotaxime or ceftriaxone injection) or in combination with ciprofloxacin has been proven effective.4,5

Vibrio vulnificus rarely is described in the literature as inducing PF. In one previously reported case, the patient was otherwise healthy and managed to recover following antibiotic therapy and wound debridement,6 whereas in another case the patient had undiagnosed liver cirrhosis and died from the infection.6,7 In the latter case, the patient presented to the emergency department in a coma. Our patient did not have the clinical signs of sepsis upon initial presentation to the emergency department. It is possible the infection rapidly progressed because of his underlying liver disease. Genotyping analysis of V vulnificus has shown that strains with low pathogenicity can cause primary septicemia in humans.7

Our case reinforces the need to quickly recognize V vulnificus as a rare underlying cause of PF and administer the appropriate treatment.