To the Editor:

The organisms of the genus Nocardia are gram-positive, ubiquitous, aerobic actinomycetes found worldwide in soil, decaying organic material, and water.1 The genus Nocardia includes more than 50 species; some species, such as Nocardia asteroides, Nocardia farcinica, Nocardia nova, and Nocardia brasiliensis, are the cause of nocardiosis in humans and animals.2,3 Nocardiosis is a rare and opportunistic infection that predominantly affects immunocompromised individuals; however, up to 30% of infections can occur in immunocompetent hosts.4 Nocardiosis can manifest in 3 disease forms: cutaneous, pulmonary, or disseminated. Cutaneous nocardiosis commonly develops in immunocompetent individuals who have experienced a predisposing traumatic injury to the skin,5 and it can exhibit a diverse variety of clinical manifestations, making diagnosis difficult. We describe a case of serious progressive primary cutaneous nocardiosis with an unusual presentation in an immunocompetent patient.

A 26-year-old immunocompetent man presented with pain, swelling, nodules, abscesses, ulcers, and sinus drainage of the left arm. The left elbow lesion initially developed at the site of a trauma 6 years prior that was painless but was contaminated with mossy soil. The condition slowly progressed over the next 2 years, and the patient experienced increased swelling and eventually developed multiple draining sinus tracts. Over the next 4 years, the lesions multiplied, spreading to the forearm and upper arm; associated severe pain and swelling at the elbow and wrist joint developed. The patient sought medical care at a local hospital and subsequently was diagnosed with suspected cutaneous tuberculosis. The patient was empirically treated with a 6-month course of isoniazid, rifampicin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol; however, the lesions continued to progress and worsen. The patient had to stop antibiotic treatment because of substantially elevated alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase levels.

He subsequently was evaluated at our hospital. He had no notable medical history and was afebrile. Physical examination revealed multiple erythematous nodules, abscesses, and ulcers on the left arm. There were several nodules with open sinus tracts and seropurulent crusts along with numerous atrophic, ovoid, stellate scars. Other nodules and ulcers with purulent drainage were located along the lymphatic nodes extending up the patient’s left forearm (Figure 1A). The yellowish-white pus discharge from several active sinuses contained no apparent granules. The lesions were densely distributed along the elbow, wrist, and shoulder, which resulted in associated skin swelling and restricted joint movement. The left axillary lymph nodes were enlarged.

Laboratory analyses revealed a hemoglobin level of 9.6 g/dL (reference range, 13–17.5 g/dL), platelet count of 621×109/L (reference range, 125–350×109/L), and leukocyte count of 14.3×109/L (reference range, 3.5–9.5 ×109/L). C-reactive protein level was 88.4 mg/L (reference range, 0–10 mg/L). Blood, renal, and liver tests, as well as tumor marker, peripheral blood lymphocyte subset, immunoglobulin, and complement results were within reference ranges. Results for Treponema pallidum and HIV antibody tests were negative. Hepatitis B virus markers were positive for hepatitis B surface antigen, hepatitis B e antigen, and hepatitis B core antibody, and the serum concentration of hepatitis B virus DNA was 3.12×107 IU/mL (reference range, <5×102 IU/mL). Computed tomography of the chest and cranium were unremarkable. Ultrasonography of the left arm revealed multiple vertical sinus tracts and several horizontal communicating branches that were accompanied by worm-eaten bone destruction (Figure 2).

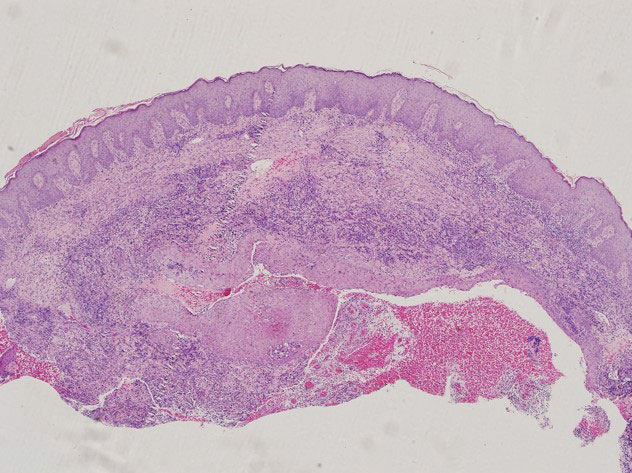

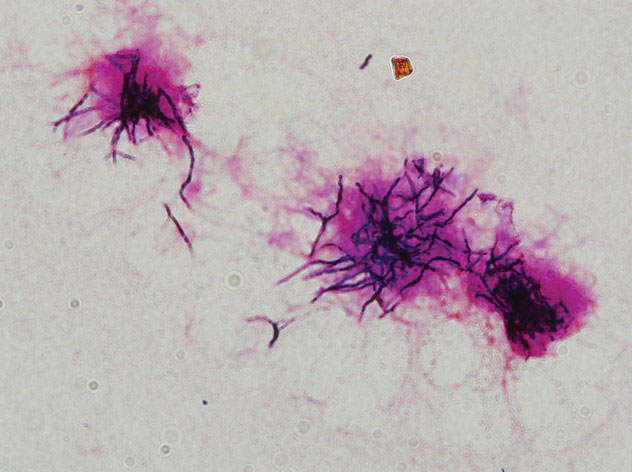

Additional testing included histopathologic staining of a skin tissue specimen—hematoxylin and eosin, periodic acid–Schiff, and acid-fast staining—showed nonspecific, diffuse, inflammatory cell infiltration suggestive of chronic suppurative granuloma (Figure 3) but failed to reveal any special strains or organisms. Gram stain examination of the purulent fluid collected from the subcutaneous tissue showed no apparent positive bacillus or filamentous granules. The specimen was then inoculated on Sabouraud dextrose agar and Lowenstein-Jensen medium for fungus and mycobacteria culture, respectively. After 5 days, chalky, yellow, adherent colonies were observed on the Löwenstein-Jensen medium, and after 26 days, yellow crinkled colonies were observed on Sabouraud dextrose agar. The colonies were then inoculated on Columbia blood agar and incubated for 1 week to aid in the identification of organisms. Growth of yellow colonies that were adherent to the agar, moist, and smooth with a velvety surface, as well as a characteristic moldy odor resulted. Gram staining revealed gram-positive, thin, and beaded branching filaments (Figure 4). Based on colony characteristics, physiological properties, and biochemical tests, the isolate was identified as Nocardia. Results of further investigations employing polymerase chain reaction analysis of the skin specimen and bacterial colonies using a Nocardia genus 596-bp fragment of 16S ribosomal RNA primer (forward primer NG1: 5’-ACCGACCACAAGGGG-3’, reverse primer NG2: 5’-GGTTGTAACCTCTTCGA-3’)6 were completely consistent with the reference for identification of N brasiliensis. Evaluation of these results led to a diagnosis of cutaneous nocardiosis after traumatic inoculation.

Because there was a high suspicion of actinophytosis or nocardiosis at admission, the patient received a combination antibiotic treatment with intravenous aqueous penicillin (4 million U every 4 hours) and oral trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (160/800 mg twice daily). Subsequently, treatment was changed to a combination of oral trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (160/800 mg twice daily) and moxifloxacin (400 mg once daily) based on pathogen identification and antibiotic sensitivity testing. After 1 month of treatment, the cutaneous lesions and left limb swelling dramatically improved and purulent drainage ceased, though some scarring occurred during the healing process. In addition, the mobility of the affected shoulder, elbow, and wrist joints slightly improved. Notable improvement in the mobility and swelling of the joints was observed at 6-month follow-up (Figure 1B). The patient continues to be monitored on an outpatient basis.

Cutaneous nocardiosis is a disfiguring granulomatous infection involving cutaneous and subcutaneous tissue that can progress to cause injury to viscera and bone.7 It has been called one of the great imitators because cutaneous nocardiosis can present in multiple forms,8,9 including mycetoma, sporotrichoid infection, superficial skin infection, and disseminated infection with cutaneous involvement. The differential diagnoses of cutaneous nocardiosis are broad and include tuberculosis; actinomycosis; deep fungal infections such as sporotrichosis, blastomycosis, phaeohyphomycosis, histoplasmosis, and coccidioidomycosis; other bacterial causes of cellulitis, abscess, or ecthyma; and malignancies.10 The principle method of diagnosis is the identification of Nocardia from the infection site.