Carpet beetle larvae of the family Dermestidae have been documented to cause both acute and delayed hypersensitivity reactions in susceptible individuals. These larvae have specialized horizontal rows of spear-shaped hairs called hastisetae, which detach easily into the surrounding environment and are small enough to travel by air. Exposure to hastisetae has been tied to adverse effects ranging from dermatitis to rhinoconjunctivitis and acute asthma, with treatment being mostly empiric and symptom based. Due to the pervasiveness of carpet beetles in homes, improved awareness of dermestid-induced manifestations is valuable for clinicians.

Beetles in the Dermestidae family do not bite humans but have been reported to cause skin reactions in addition to other symptoms typical of an allergic reaction. Skin contact with larval hairs (hastisetae) of these insects—known as carpet, larder, or hide beetles — may cause urticarial or edematous papules that are mistaken for papular urticaria or arthropod bites. 1 There are approximately 500 to 700 species of carpet beetles worldwide. Carpet beetles are a clinically underrecognized cause of allergic contact dermatitis given their frequent presence in homes across the world. 2 Carpet beetle larvae feed on shed skin, feathers, hair, wool, book bindings, felt, leather, wood, silk, and sometimes grains and thus can be found nearly anywhere. Most symptom-inducing exposures to Dermestidae beetles occur occupationally, such as in museum curators working hands-on with collection materials and workers handling infested materials such as wool. 3,4 In-home Dermestidae exposure may lead to symptoms, especially if regularly worn clothing and bedding materials are infested. The broad palate of dermestid members has resulted in substantial contamination of stored materials such as flour and fabric in addition to the destruction of museum collections. 5-7

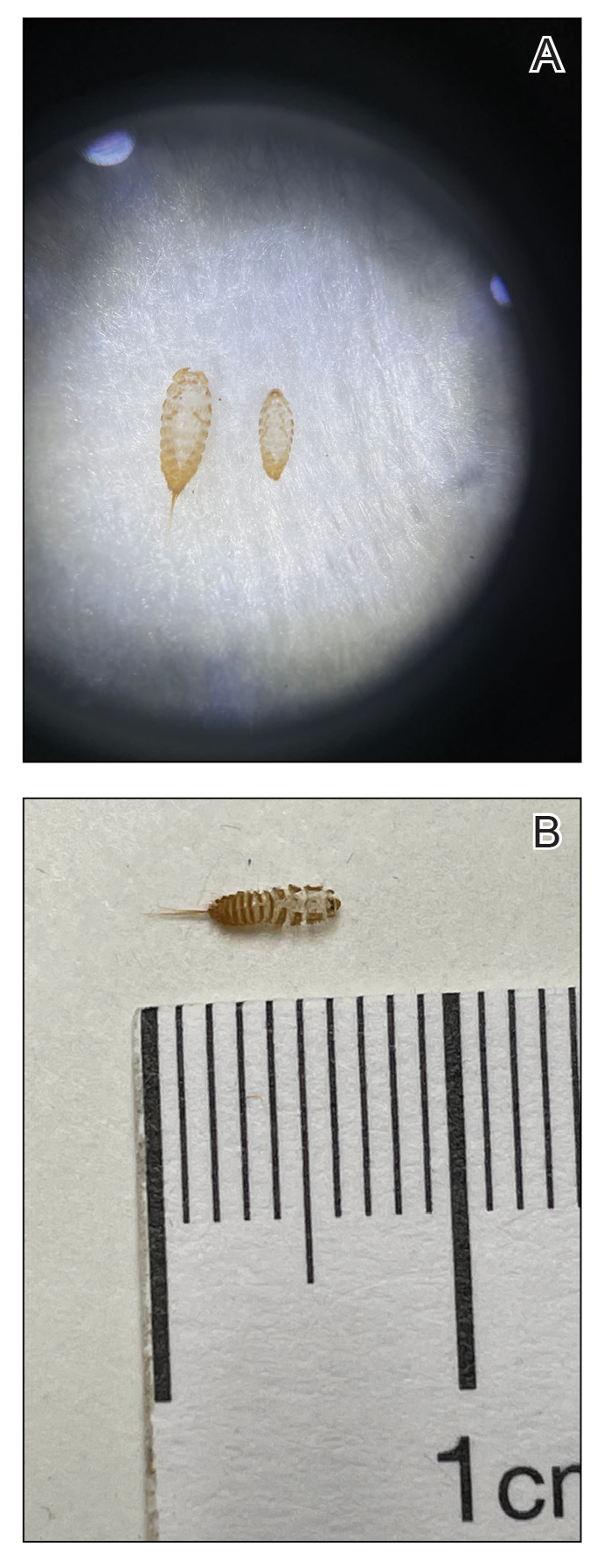

The larvae of some dermestid species, most commonly of the genera Anthrenus and Dermestes, are 2 to 3 mm in length and have detachable hairlike hastisetae that shed into the surrounding environment throughout larval development (Figure 1).8 The hastisetae, located on the thoracic and abdominal segments (tergites), serve as a larval defense mechanism. When prodded, the round, hairy, wormlike larvae tense up and can raise their abdominal tergites while splaying the hastisetae out in a fanlike manner.9 Similar to porcupine quills, the hastisetae easily detach and can entrap the appendages of invertebrate predators. Hastisetae are not known to be sharp enough to puncture human skin, but friction and irritation from skin contact and superficial sticking of the hastisetae into mucous membranes and noncornified epithelium, such as in the bronchial airways, are thought to induce hypersensitivity reactions in susceptible individuals.

Additionally, hastisetae and the exoskeletons of both adult and larval dermestid beetles are composed mostly of chitin, which is highly allergenic. Chitin has been found to play a proinflammatory role in ocular inflammation, asthma, and bronchial reactivity via T helper cell (TH2)–mediated cellular interactions.10-12 Larvae shed their exoskeletons, including hastisetae, multiple times over the course of their development, which contributes to their potential allergen burden (Figure 2). Reports of positive prick and/or patch testing to larval components indicate some cases of both acute type 1 and delayed type 4 hypersensitivity reactions.4,8,13

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

Multiple erythematous urticarial papules, papulopustules, and papulovesicles are the typical manifestations of dermestid dermatitis.3,4,13-16 Figure 3 demonstrates several characteristic edematous papules with background erythema. Unlike the clusters seen with flea and bed bug bites, dermestid-induced lesions typically are single and scattered, with a propensity for exposed limbs and the face. Exposure to hastisetae commonly results in classic allergic symptoms including rhinitis, conjunctivitis, coughing, wheezing, sneezing, and intranasal and periocular pruritus, even in those with no personal history of atopy.17-19 Lymphadenopathy, vasculitis, and allergic alveolitis also have been reported.20 A large infestation in which many individual beetles as well as larvae can be found in 1 or more areas of the inhabited structure has been reported to cause more severe symptoms, including acute eczema, otitis externa, lymphocytic vasculitis, and allergic alveolitis, all of which resolved within 3 months of thorough deinfestation cleaning.21

Skin-prick and/or patch testing is not necessary for this clinical diagnosis of dermestid-induced allergic contact dermatitis. This diagnosis is bolstered by (but does not require a history of) repeated symptom induction upon performing certain activities (eg, handling taxidermy specimens) and/or in certain environments (eg, only at home). Because of individual differences in hypersensitivity to dermestid parts, it is not typical for all members of a household to be affected.

When there are multiple potential suspected allergens or an unknown cause for symptoms despite a detailed history, allergy testing can be useful in confirming a diagnosis and directing management. Immediate-onset type 1 hypersensitivity reactions are evaluated using skin-prick testing or serum IgE levels, whereas delayed type 4 hypersensitivity reactions can be evaluated using patch testing. Type 1 reactions tend to present with classic allergy symptoms, especially where there are abundant mast cells to degranulate in the skin and mucosa of the gastrointestinal and respiratory tracts; these symptoms range from mild wheezing, urticaria, periorbital pruritus, and sneezing to outright asthma, diarrhea, rhinoconjunctivitis, and even anaphylaxis. With these reactions, initial exposure to an antigen such as chitin in the hastisetae leads to an asymptomatic sensitization against the antigen in which its introduction leads to a TH2-skewed cellular response, which promotes B-cell production of IgE antibodies. Upon subsequent exposure to this antigen, IgE antibodies bound to mast cells will lead them to degranulate with release of histamine and other proinflammatory molecules, resulting in clinical manifestations. The skin-prick test relies on introduction of potential antigens through the epidermis into the dermis with a sharp lancet to induce IgE antibody activation and then degranulation of the patient’s mast cells, resulting in a pruritic erythematous wheal. This IgE-mediated process has been shown to occur in response to dermestid larval parts among household dust, resulting in chronic coughing, sneezing, nasal pruritus, and asthma.15,17,22