To the Editor:

Prescriptions for isotretinoin may be influenced by patient demographics, medical comorbidities, and drug safety programs.1,2 In 1982, isotretinoin was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for treatment of severe recalcitrant nodulocystic acne that is nonresponsive to conventional therapies such as antibiotics; however, prescriber beliefs regarding the necessity of oral antibiotic failure before isotretinoin is prescribed may be influenced by the provider’s generational age.3 Currently, there is a knowledge gap regarding the impact of provider characteristics, including the year providers completed training, on isotretinoin utilization. The aim of our cross-sectional study was to characterize generational isotretinoin prescribing habits in a large-scale midwestern private practice dermatology group.

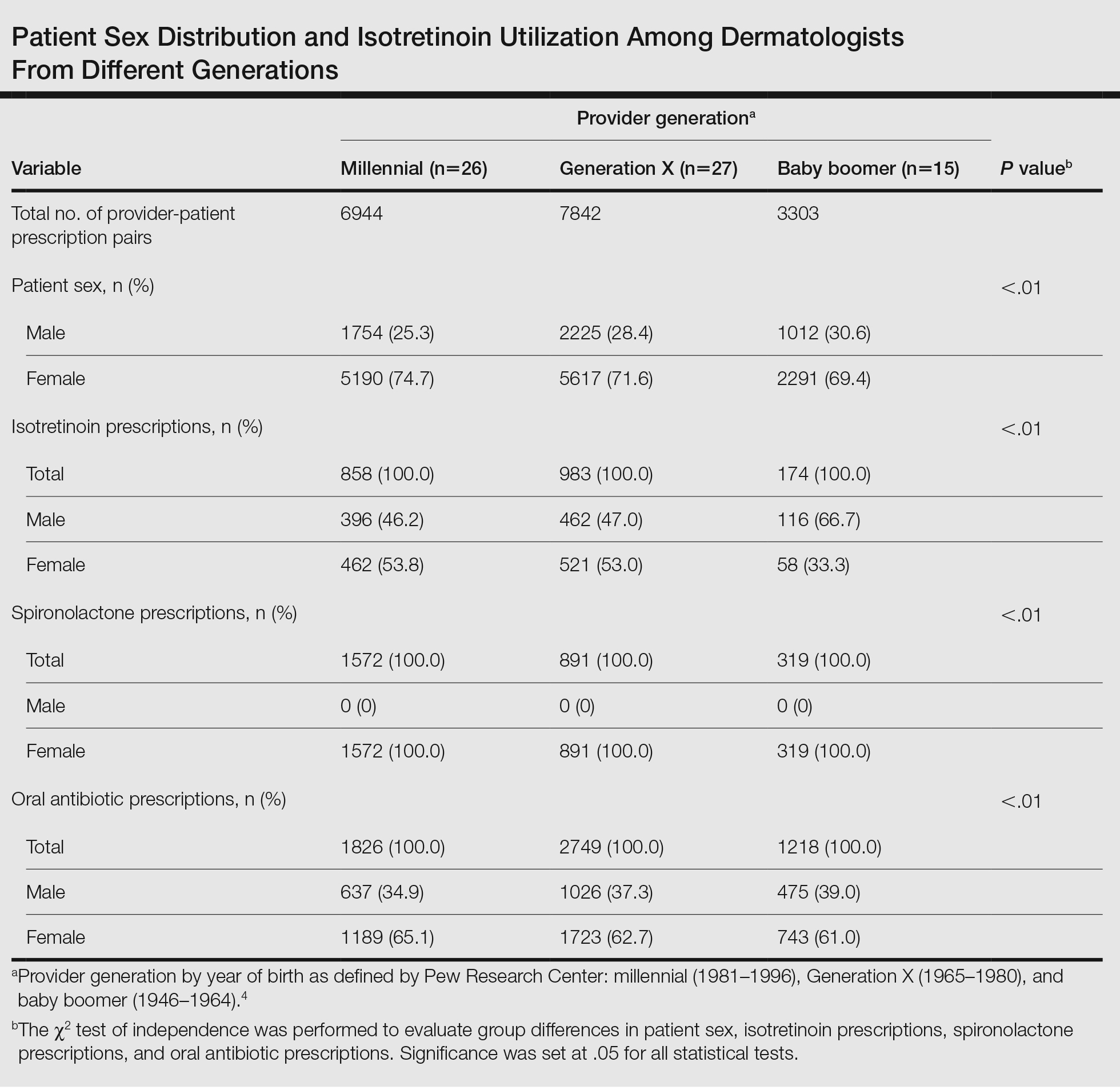

Modernizing Medicine (https://www.modmed.com), an electronic medical record software, was queried for all encounters that included both an International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification diagnosis code L70.0 (acne vulgaris) and a medication prescription from May 2021 to May 2022. Data were collected from a large private practice group with locations across the state of Ohio. Exclusion criteria included provider-patient prescription pairs that included non–acne medication prescriptions, patients seen by multiple providers, and providers who treated fewer than 5 patients with acne during the study period. A mixed-effect multiple logistic regression was performed to analyze whether a patient was ever prescribed isotretinoin, adjusting for individual prescriber, prescriber generation (millennial [1981–1996], Generation X [1965–1980], and baby boomer [1946–1964]),4 and patient sex; spironolactone and oral antibiotic prescriptions during the study period were included as additional covariates in a subsequent post hoc analysis. This study utilized data that was fully deidentified in accordance with the US Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) Privacy Rule. Approval from an institutional review board was not required.

A total of 18,089 provider-patient prescription pairs were included in our analysis (Table). In our most robust model, female patients were significantly less likely to receive isotretinoin compared with male patients (adjusted OR [aOR], 0.394; P<.01). Millennial providers were significantly more likely to utilize isotretinoin in patients who did not receive antibiotics compared with patients who did receive antibiotics (aOR, 1.693; P<.01). When compared with both Generation X and baby boomers, millennial providers were more likely to prescribe isotretinoin in patients who received antibiotics (aOR, 2.227 [P=.02] and 3.638 [P<.01], respectively).

In 2018, the American Academy of Dermatology and the Global Alliance to Improve Outcomes in Acne updated thir guidelines to recommend isotretinoin as a first-line therapy for severe nodular acne, treatment-resistant moderate acne, or acne that produces scarring or psychosocial distress.5 Our study results suggest that millennial providers are adhering to these guidelines and readily prescribing isotretinoin in patients who did not receive antibiotics, which corroborates survey findings by Nagler and Orlow.3 Our results also revealed that prescriber generation may influence isotretinoin usage, with millennials utilizing isotretinoin more in patients who received oral antibiotic therapy than their older counterparts. In part, this may be due to beliefs among older generations that failure of oral antibiotics is necessary before pursuing isotretinoin.3 Additionally, this finding suggests that millennials, if utilizing antibiotics for acne, may have a lower threshold for starting isotretinoin in patients who received oral antibiotic therapy.

Generational prescribing variation appears not to be unique to isotretinoin and also may be present in the use of spironolactone. Over the past decade, utilization of spironolactone for acne treatment has increased, likely in response to new data demonstrating that routine use is safe and effective.6 Several large cohort and retrospective studies have debunked the historical concerns for tumorigenicity in those with breast cancer history as well as the need for routine laboratory monitoring for hyperkalemia.7,8 Although spironolactone use for the treatment of acne has increased, it still remains relatively underutilized,6 suggesting there may be a knowledge gap similar to that of isotretinoin, with younger generations utilizing spironolactone more readily than older generations.

Our study analyzed generational differences in isotretinoin utilization for acne over 1 calendar year. Limitations include sampling from a midwestern patient cohort and private practice–based providers. Due to limitations of our data set, we were unable to capture acne medication usage prior to May 2021, temporal sequencing of acne medication usage, and stratification of patients by acne severity. Furthermore, we were unable to capture female patients who were pregnant or planning pregnancy at the time of their encounter, which would exclude isotretinoin usage.

Overall, millennial providers may be utilizing isotretinoin more in line with the updated acne guidelines5 compared with providers from older generations. Further research is necessary to elucidate how these prescribing habits may change based on acne severity.