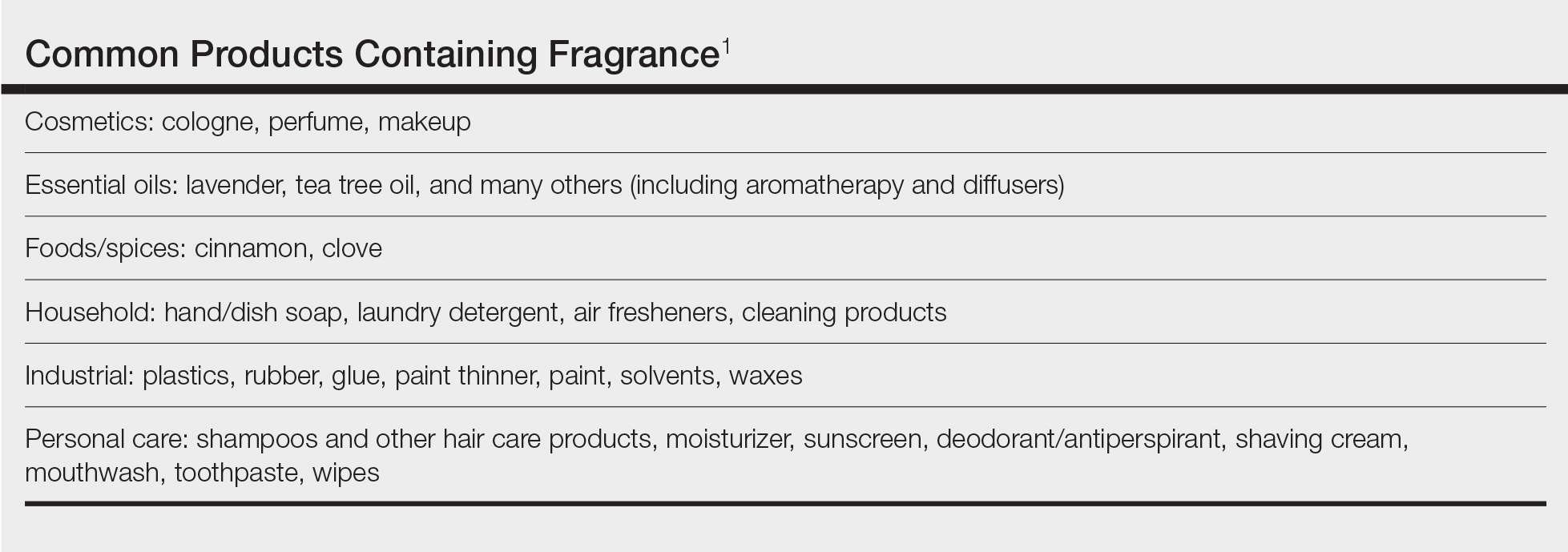

Fragrances are complex organic compounds that are sufficiently volatile to produce an odor—most often a pleasant one—or at times intended to neutralize unpleasant odors. They can be further divided into natural fragrances (eg, essential oils) and synthetic ones. Fragrances are found in abundance in our daily lives: in perfumes; colognes; lotions; shampoos; and an array of other personal, household, and even industrial products (Table). These exposures include products directly applied to the skin, rinsed off, or aerosolized. A single product often contains a multitude of different fragrances to create the scents we know and love. To many, fragrances can be an important part of everyday life or even a part of one’s identity. But that once-intoxicating aroma can transform into an itchy skin nightmare; fragrances are among the most common contact allergens.

Given the widespread prevalence of fragrances in so many products, understanding fragrance allergy and skillful avoidance is imperative. In this review, we explore important aspects of fragrance allergic contact dermatitis (ACD), including chemistry, epidemiology, patch test considerations, and management strategies for patients, with the goal of providing valuable clinical insights for treating physicians on how patients can embrace a fragrance-free lifestyle.

How Fragrances Act as Allergens

A plethora of chemicals emit odors, of which more than 2000 are used to create the fragranced products we see on our shelves today.1 For many of these fragrances, contact allergy develops because the fragrance acts as a hapten (ie, a small molecule that combines with a carrier protein to elicit an immune response).2 Some fragrance molecules require “activation” to be able to bind to proteins; these are known as prehaptens.3 For example, the natural fragrance linalool is generally considered nonallergenic in its initial form. However, once it is exposed to air, it may undergo oxidation to become linalool hydroperoxides, a well-established contact allergen. Some fragrances can become allergenic in the skin itself, often secondary to enzymatic reactions—these are known as prohaptens.3 However, most fragrances are directly reactive to skin proteins on the basis of chemical reactions such as Michael addition and Schiff base formation.4 In either case, the end result is that fragrance allergens, including essential oils, may cause skin sensitization and subsequent ACD.5,6

Epidemiology

Contact allergy to fragrances is not uncommon; in a multicenter cross-sectional study conducted in 5 European countries, the prevalence in the general population was estimated to be as high as 2.6% and 1.9% among 3119 patients patch tested to fragrance mix I (FMI) and fragrance mix II (FMII), respectively.7 Studies in patients referred for patch testing have shown a higher 5% to 25% prevalence of fragrance allergy, largely depending on what population was evaluated.1 Factors such as sociocultural differences in frequency and types of fragrances used could contribute to this variation.

During patch testing, the primary fragrance screening allergens are FMI, FMII, and balsam of Peru (BOP)(Myroxylon pereirae resin).7 In recent years, hydroperoxides of linalool and limonene also have emerged as potentially important fragrance allergens.8 The frequencies of patch-test positivity of these allergens can be quite high in referral-based populations. In a study performed by the North American Contact Dermatitis Group (NACDG) from 2019 to 2020, frequencies of fragrance allergen positivity were 12.8% for FMI, 5.2% for FMII, 7.4% for BOP, 11.1% for hydroperoxides of linalool, and 3.5% for hydroperoxides of limonene.8 Additionally, it was noted that FMI and hydroperoxides of linalool were among the top 10 most frequently positive allergens.9 It should be kept in mind that NACDG studies are drawn from a referral population and not representative of the general population.

Allergic contact dermatitis to fragrances can manifest anywhere on the body, but certain patterns are characteristic. A study by the NACDG analyzed fragrance and botanical patch test results in 24,246 patients and found that fragrance/botanical-sensitive patients more commonly had dermatitis involving the face (odds ratio [OR], 1.12; 95% CI, 1.03-1.21), legs (OR, 1.22; 95% CI, 1.06-1.41), and anal/genital areas (OR, 1.26; 95% CI, 1.04-1.52) and were less likely to have hand dermatitis (OR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.82-0.95) compared with non–fragrance/botanical-sensitive patients.10 However, other studies have found that hand dermatitis is common among fragrance-allergic individuals.11-13

Fragrance allergy tends to be more common in women than men, which likely is attributable to differences in product use and exposure.10 The prevalence of fragrance allergy increases with age in both men and women, peaking at approximately 50 years of age, likely due to repeat exposure or age-related changes to the skin barrier or immune system.14

Occupational fragrance exposures are important to consider, and fragrance ACD is associated with hairdressers, beauticians, office workers exposed to aromatherapy diffusers, and food handlers.15 Less-obvious professions that involve exposure to fragrances used to cover up unwanted odors—such as working with industrial and cleaning chemicals or even metalworking—also have been reported to be associated with ACD.16