Statin therapy likely didn’t lead to dementia or even mild cognitive impairment (MCI) in older patients taking the drugs for cardiovascular (CV) primary prevention in a post hoc analysis of a trial that required normal cognitive ability for entry.

Nor did statins, whether lipophilic or hydrophilic, appear to influence changes in cognition or affect separate domains of mental performance, such as memory, language ability, or executive function, over the trial’s follow-up, which averaged almost 5 years.

Although such findings aren’t novel – they are consistent with observations from a number of earlier studies – the new analysis included a possible signal for a statin association with new-onset dementia in a subgroup of more than 18,000 patients. Researchers attribute the retrospective finding, from a trial not designed to explore the issue, to confounding or chance.

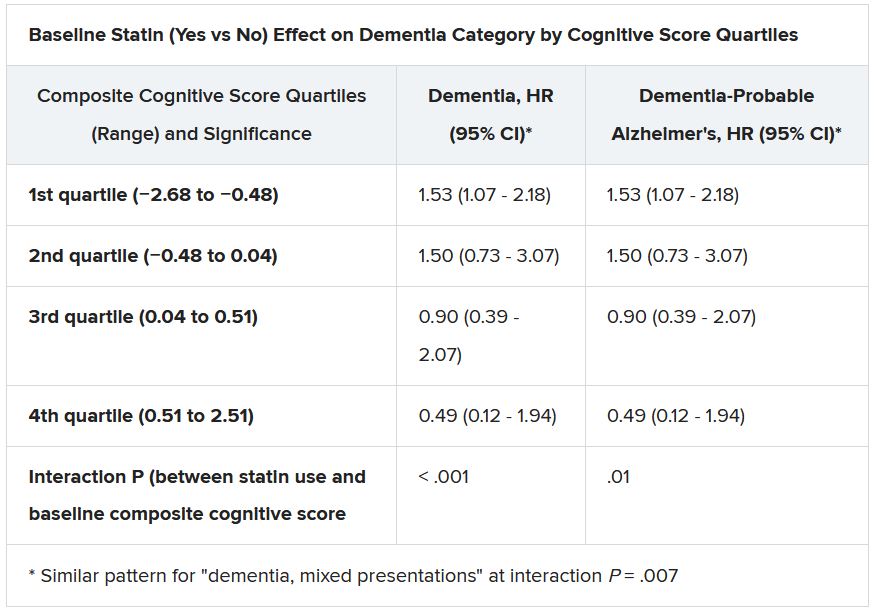

Still, the adjusted risk for dementia seemed to go up by a third among statin users who at baseline placed in the lowest quartile for cognitive function, based on a composite test score, in the ASPREE trial, a test of primary-prevention low-dose aspirin in patients 65 or older. The better the baseline cognitive score by quartile, the lower the risk for dementia ( interaction P < .001).

The bottom-quartile association of statins with dementia was driven by new diagnoses of Alzheimer’s disease, as opposed to the study’s other “mixed presentation” dementia subtype, wrote the authors of analysis, published June 21, 2021, in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology), led by Zhen Zhou, PhD, Menzies Institute for Medical Research, University of Tasmania, Hobart, Australia.

“I wouldn’t overinterpret that,” said senior author Mark R. Nelson, MBBS, PhD, of the same institution. Indeed, it should be “reassuring” for physicians prescribing statins to older patients that there was no overall statin effect on cognition or new-onset dementia, he said in an interview.

“This is a post hoc analysis within a dataset, although a very-high-quality dataset, it must be said.” The patients were prospectively followed for a range of cognition domains, and the results were adjudicated, Dr. Nelson observed. Although the question of statins and dementia risk is thought to be largely settled, the analysis “was just too tempting not to do.”

On the basis of the current analysis and the bulk of preceding evidence, “lipid lowering in the short term does not appear to result in improvement or deterioration of cognition irrespective of baseline LDL cholesterol levels and medication used,” Christie M. Ballantyne, MD, and Vijay Nambi, MD, PhD, both from Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

The current study “provides additional information that the lipo- or hydrophilicity of the statin does not affect changes in cognition. However, the potential increased risk for Alzheimer’s disease, especially among patients with baseline cognitive impairment, requires further investigation.”

The current analysis is reassuring that the likelihood of such statin effects on cognition “is vanishingly small,” Neil J. Stone MD, Northwestern University, Chicago, said in an interview. In fact, its primary finding of no such association “best summarizes what we know in 2021 about statin therapy” after exploration of the issue in a number of prospective trials and systematic reviews, said Dr. Stone, who was not a coauthor on the report.

The observed interaction between statin use and baseline neurocognitive ability “is hypothesis raising at best. It should be explored in randomized, controlled trials that can look at this question in an unbiased manner,” he agreed.

If patients believe or suspect that a statin is causing symptoms that suggest cognitive dysfunction, “what they really need to do is to stop it for 3 weeks and check out other causes. And in rechallenging, the guidelines say, if they think that it’s causing a memory problem that occurs anecdotally, then they can be given another statin, usually, which doesn’t cause it.”

ASPREE compared daily low-dose aspirin with placebo in a community-based older population numbering about 19,000 in Australia and the United States. Patients were initially without known CV disease, dementia, or physical disabilities. It did not randomize patients by statin therapy.

Of note, entry to the trial required a score of at least 78 on the Modified Mini-Mental State Examination (3MS), corresponding to normal cognition.

Aspirin showed no significant benefit for disability-free survival, an endpoint that included death and dementia, or CV events over a median of 4.7 years. It was associated with slightly more cases of major hemorrhage, as previously reported.

A subsequent ASPREE analysis suggested that the aspirin had no effect on risks of mild cognitive impairment, cognitive decline, or dementia.

Of the 18,846 patients in the current post hoc analysis, the average age of the patients was 74 years, and 56.4% were women; 31.3% were taking statins at baseline. The incidence of dementia per 1,000 person-years for those taking statins in comparison with those not taking statins was 6.91 and 6.48, respectively. Any cognitive changes were tracked by the 3MS and three other validated tests in different domains of cognition, with results contributing to the composite score.

The corresponding incidence of dementia considered probable Alzheimer’s disease was 2.97 and 2.65 for those receiving versus not receiving statins, respectively. The incidence of dementia with mixed presentation was 3.94 and 3.84, respectively.

There were no significant differences in risk for dementia overall or for either dementia subtype in multivariate analyses. Adjustments included demographics, CV lifestyle risk factors, family medical history, including dementia, ASPREE randomization group, and individual scores on the four tests of cognition.

Results for development of MCI mirrored those for dementia, as did results stratified for baseline lipids and for use of lipophilic statins, such as atorvastatin or simvastatin versus hydrophilic statins, including pravastatin and rosuvastatin.

Significant interactions were observed between composite cognitive scores and statin therapy at baseline; as scores increased, indicating better cognitive performance, the risks for dementia and its subtypes went down. Statins were associated with incident dementia at the lowest cognitive performance quartile.

That association is probably a function of the cohort’s advanced age, Dr. Nelson said. “If you get into old age, and you’ve got high cognitive scores, you’ve probably got protective factors. That’s how I would interpret that.”

Dr. Ballantyne and Dr. Nambi also emphasized the difficulties of controlling for potential biases even with extensive covariate adjustments. The statin dosages at which patients were treated were not part of the analysis, “and achieved LDL [cholesterol levels over the study period were not known,” they wrote.

“Furthermore, patients who were treated with statins were more likely to have diabetes, hypertension, chronic kidney disease, and obesity, all of which are known to increase risk for cognitive decline, and, as might have been predicted, statin users therefore had significantly lower scores for global cognition and episodic memory.”

Dr. Nelson pointed to an ongoing prospective atorvastatin trial that includes dementia in its primary endpoint and should be “the definitive study.” STAREE (Statin Therapy for Reducing Events in the Elderly) is running throughout Australia with a projected enrollment of 18,000 and primary completion by the end of 2022. “We’ve already enrolled 8,000 patients.”

Less far along is the PREVENTABLE (Pragmatic Evaluation of Events and Benefits of Lipid-Lowering in Older Adults) trial, based in the United States and also randomizing to atorvastatin or placebo, that will have an estimated 20,000 older patients and completion in 5 years. The primary endpoint is new dementia or persistent disability.

Both trials “are powered to enable firm conclusions concerning any statin effects,” said Dr. Ballantyne and Dr. Nambi. “In the meantime, practicing clinicians can have confidence and share with their patients that short-term lipid-lowering therapy in older patients, including with statins, is unlikely to have a major impact on cognition.”

ASPREE was supported by grants from the U.S. National Institute on Aging and the National Cancer Institute and the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, by Monash University, and by the Victorian Cancer Agency. Dr. Nelson reported receiving honoraria from Sanofi and Amgen; support from Bayer for ASPREE; and grant support for STAREE. Disclosures for the other authors are in the report. Dr. Ballantyne disclosed grant and research support from Abbott Diagnostic, Akcea, Amgen, Esperion, Ionis, Novartis, Regeneron, and Roche Diagnostics; and consulting for Abbott Diagnostics, Althera, Amarin, Amgen, Arrowhead, AstraZeneca, Corvidia, Denka Seiken, Esperion, Genentech, Gilead, Matinas BioPharma, New Amsterdam, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Regeneron, Roche Diagnostics, and Sanofi-Synthelabo. Dr. Nambi is a coinvestigator on a provisional patent along with Baylor College of Medicine and Roche on the use of biomarkers to predict heart failure, and a site principal investigator for studies sponsored by Amgen and Merck. Dr. Stone had no disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.